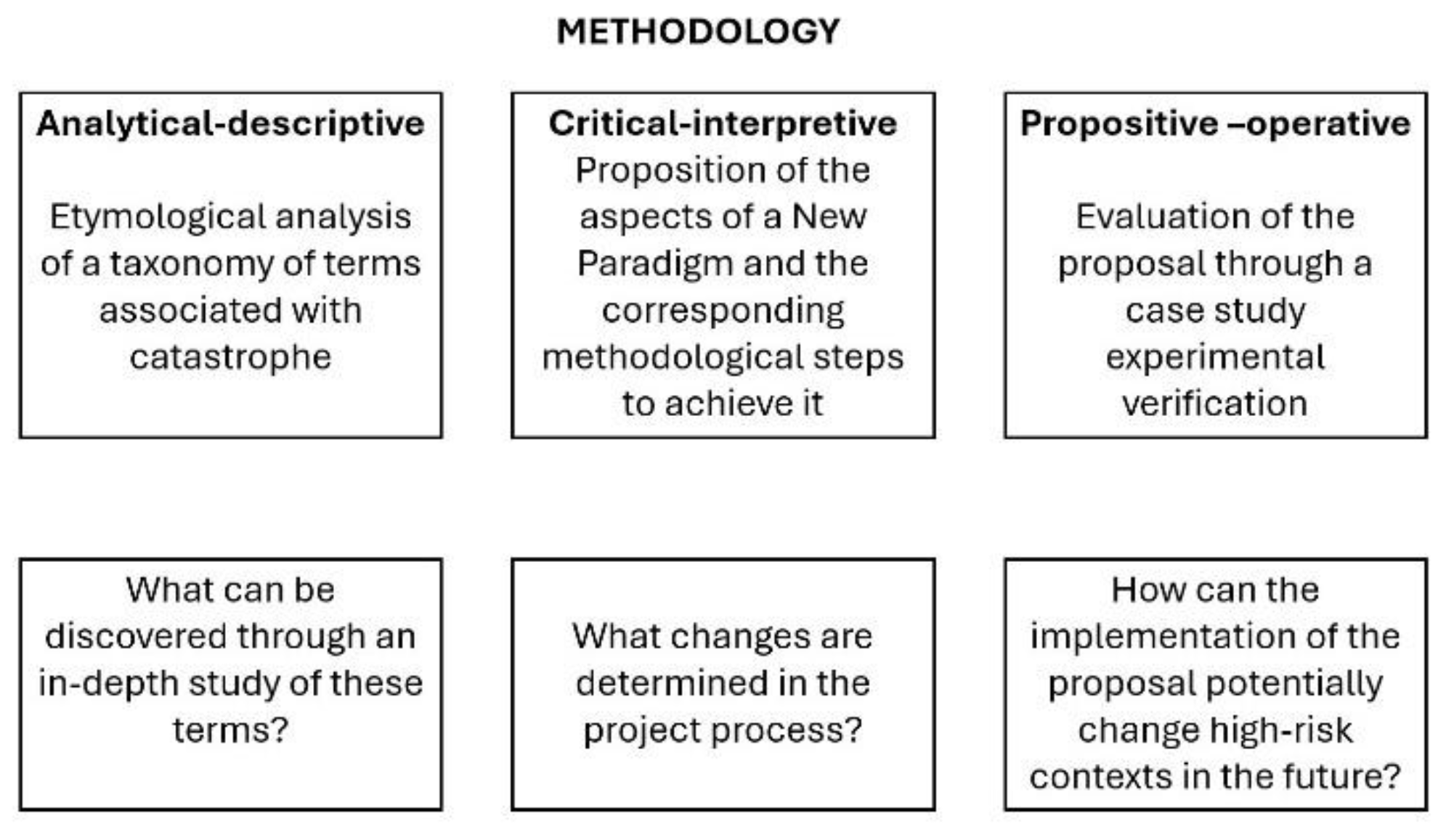

3. Results

The terms selected for this taxonomy will enable an understanding that the words commonly used in the context of catastrophes carry profound meanings that encompass necessary indications for defining the guidelines of a new paradigm as an open, resilient, and morphogenetic process.

The selected terms are Catastrophe, Emergency, Crisis, Resilience, Project/Process, Reconstruction/Regeneration.

Catastrophe, a term of Greek origin Katastrophé (καταστροφή), literally means disorder, upheaval, inversion. In ancient Greece, it was used to identify the negative resolution of tragedy [

6] (p.4).

The term negatively identifies an unexpected and rapid change in present conditions that leads an apparently stable system into a condition of instability. A catastrophe is typically identified as the negative outcome of a series of human-social events (such as terrorist attacks, wars, pandemics, etc.), an unexpected and sudden disaster such as a technological calamity (fires, explosions, release of toxic substances, etc.), or a natural one (earthquakes, floods, landslides, volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, etc.). The characteristics of a catastrophic event relate to its exceptional nature, the degree of destruction to the natural and human environment, the disruption of normal life, the loss of human lives, and the emotional void it generates.

History is replete with catastrophes of various genres and origins. However, nowadays, there is a noticeable increase in disastrous events due to population growth, urban population concentration, environmental exploitation, and the effects of climate change resulting from human activity.

A catastrophe, in general, profoundly affects the physical-spatial, socio-cultural, and technological-environmental aspects of affected areas. When a catastrophe occurs, two fundamental realms are involved: the spatial realm and the population inhabiting the affected space.

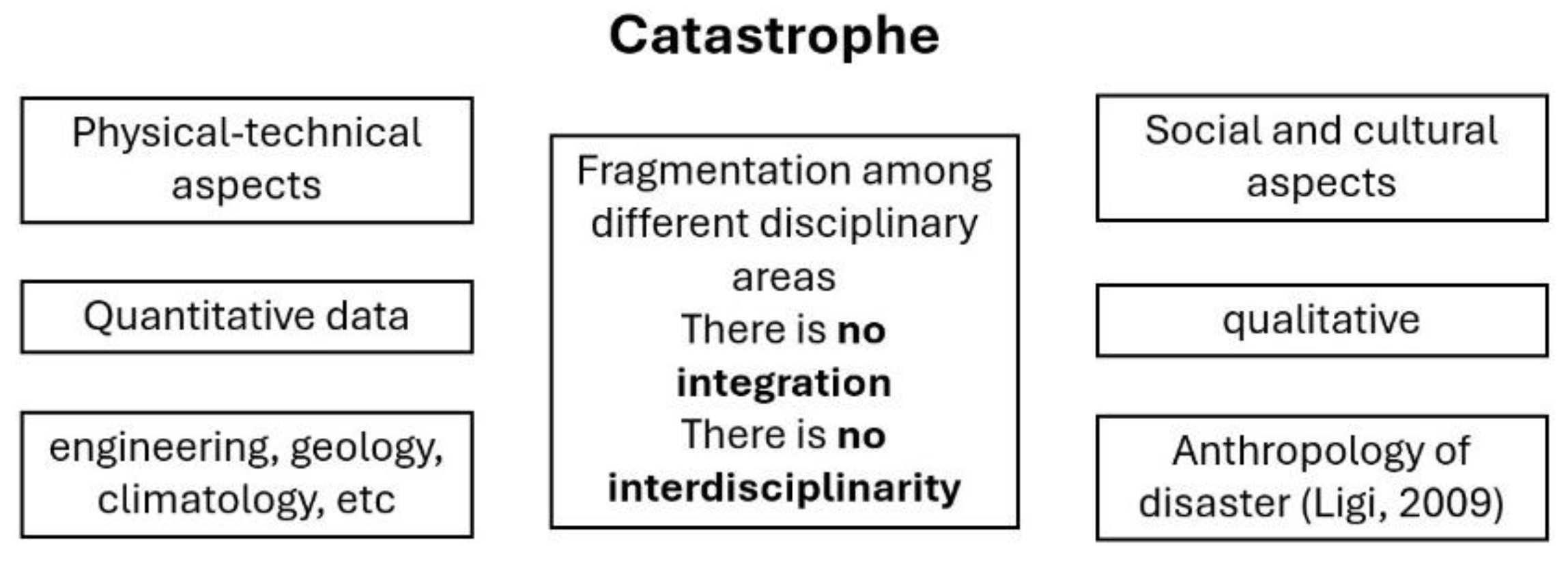

Most studies on catastrophes develop arguments derived from scientific disciplines that observe and evaluate post-disaster quantitative data. Disciplines such as engineering, geology, climatology, and physics collect objective information that enables the drafting of cause-effect relationships from a physical-technical perspective. However, these disciplines rarely address social and cultural aspects related to catastrophic events, resulting in a historical disciplinary void. While social and psychological aids have always existed, it was only in recent years that a specific research field capable of determining a distinct discipline emerged. This new discipline, known as disaster anthropology [

7], defines a catastrophe as:

“a critically extreme situation that arises when a potentially destructive agent affects a certain population, which subsequently finds itself embraced in the new conditions generated by physical and social vulnerability” [

7] (p. 48).

Disaster anthropology applies theories and methods of socio-cultural anthropology to the study of disasters, emphasizing the fundamental role of socio-cultural aspects in catastrophic events (before, during, and after impact), as explained by Gianluca Ligi in the book Antropologia dei disastri [

7] (Disaster Anthropology).

Ligi’s research underscores that socio-cultural aspects, rather than mere consequences, should be considered complementary in the study of catastrophic events.

The emergence of this new discipline highlights an important aspect: current intervention tools, both preliminary and subsequent to impactful events, tend to focus solely on their specific disciplinary realms without incorporating aspects from other disciplines.

(Figure 3)

- 2.

Emergency

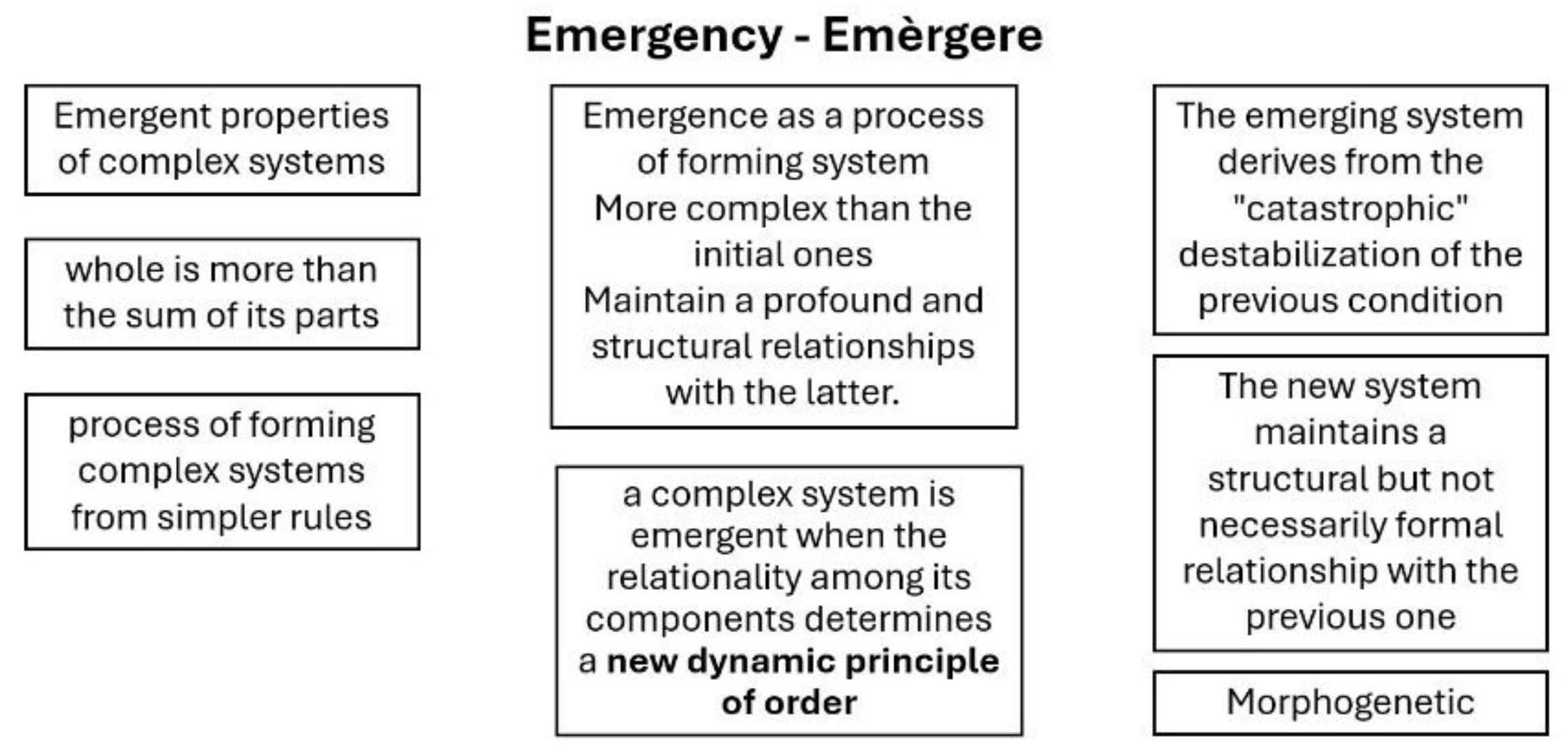

It is possible to identify two main meanings attributable to the term Emergency: On one hand, there are the meanings stemming from the Latin etymology of the word Emergere (what emerges); on the other hand, there are those that refer to the Anglo-Saxon term Emergency, which defines a crisis condition that requires rapid intervention.

The first meaning, in addition to botanical studies, pertains to research on the emergent properties of complex systems involving numerous disciplines: physics, mathematics, biology, philosophy, sociology, architecture, etc. These studies, connected to a structuralist view of complex systems, are based on the prerequisite that a whole is more than the sum of its parts, as it presents emergent properties not detectable in the individual components . In this context, an emergence is defined as the process of forming complex systems from simpler rules; this occurs when interactions between components increase, allowing for the potential emergence of new physical, social, cultural, economic, and spatial relationships. Emergent properties are unpredictable and unexpected, meaning they cannot be anticipated through the study of each constitutive element of a system. It is the modes of relationship and interaction between the parts that allow for the emergence of these properties. The pursuit of spatial, social, physical, and virtual rationality allows for the emergence of a complex system in which different pieces, fragments, and loose elements transform according to a process where the various components interact with each other according to a newly presupposed order through the design process. Within this framework, it seems possible to assert that, from an architectural and urban perspective, the mere analysis of individual components does not allow for the prediction of a possible future scenario. Instead, a qualitative evaluation capable of relating all components of a human settlement (physical, social, economic, etc.) must be added to the quantitative component, along with the memory of the places to which they belong and the future needs that the modification operation requires.

This meaning of the term allows us to consider emergence as a process of forming systems that are more complex than the initial ones, which maintain profound and structural relationships with the latter. From this consideration, it can be said that a complex system is emergent when the rationality among its components determines a new dynamic principle of order. A principle that underpins a dialectic between stability and instability and leads us to look beyond formal-figurative conformation to understand latent morphogenetic processes.

These processes assume a precise morphogenetic connotation, whereby each component derives from the “catastrophic” and sudden destabilization of a previous form. This destabilization generates the condition of emergency, which refers to an unforeseen circumstance, a critical moment that induces an unexpected change in consolidated orders. This leads to the introduction of the term “crisis” as a relationship between stability and instability.

(Figure 4)

- 3.

Crisis, or the Relationship Between Stability and Instability

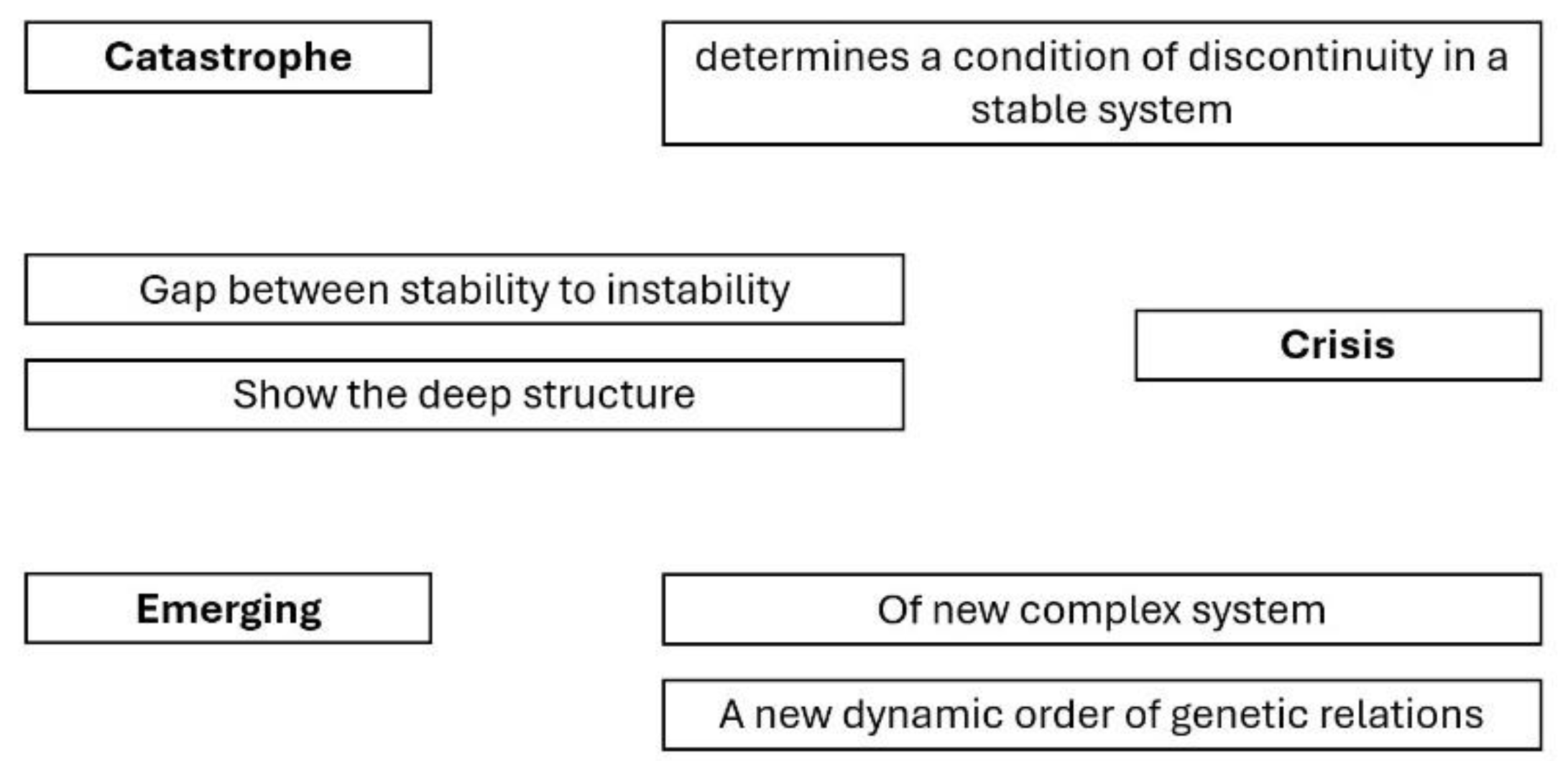

The term crisis, derived from the Greek Krisis, derived from Krino (κρίσις, from the Greek κρίνω: to separate, distinguish, judge), literally means a moment that separates one way of being or a series of phenomena from another.

Therefore, the condition of Crisis determines a discontinuity, a rupture, a change from previously organized orders, and signals the transition from a condition of stability to one of instability, in which recognizable forms of reality (physical, social, economic) deform and become available to processes that allow for the development of new, or rather transformed, orders, tied to the precedents in a generative manner.

From a mathematical-scientific standpoint, morphogenetic studies deal with the mutation of substances from their origins. This dynamic phenomenon begins when a rupture is determined in a stable conformation, such rupture opens the possibility of new conformations being formed, different from the initial one, yet maintaining a structural relationship (DNA of the form). These studies related to the genetics of forms have been developed by Ilya Prigogine in 1955, in his research on the irreversibility of thermodynamic systems, and by René Thom in morphogenetic studies [

8].

Such mathematical-scientific investigations challenge the theories of continuity and stability in studies on origins, as through morphogenetic models they argue that discontinuity and continuity can coexist within the same transformation process.

Based on the analysis conducted up to this point, it can be summarized that: a catastrophe determines a condition of discontinuity (emergency, crisis) within a dynamic system in a condition of stability, and at the same time allows for the emergence of a new order of relationships that is not directly continuous (figure of the form) with the precedent, but maintains points of contact referring to its original genetic-structural aspects (structure of the form). There is therefore a deep structure of the form to which morphological variations refer each time a condition of discontinuity occurs.

Carlos Martí Aris, in his well-known text “Variations of Identity” [

9], asserts the presence of an original matter capable of building a structural and non-figurative connection between a preceding and a subsequent condition. Martí Aris understands original matter as a dynamic structure of the form that presupposes a rationality among its components and involves the variables of time and movement.

In conclusion it can be said that no form constituting reality is immutable. There are moments of crisis that reveal the transition from a condition of stability to one of instability, but these moments, even if violent and destructive, allow for the identification of the deep structure that enables the unstable system to undergo transformation without losing its original characteristics. According to this perspective, the crisis of a system, if properly addressed, can be configured as an opportunity for evolution.

(Figure 5)

A catastrophe disrupts stable systems and opens a gap toward instability. The crisis phase reveals the deep structure of the system and enables the emergence of a new dynamic order through morphogenetic transformation.

- 4.

Resilience.

The latter half of the 20th century has been characterized as one of the most stable periods in history; however, these first twenty years of the 21st century have led to an understanding that conditions are undergoing profound changes: floods, earthquakes, and collapses are becoming increasingly frequent, and the widespread political-economic crisis seems to have become a condition of normalcy. The relentless pursuit of wealth and continuous development, at any cost, has generated evident instability. The time and space of emergency are expanding each day, and the frequency, ever more rapid, with which they occur, requires a different attention, a new way of thinking about the critical moment through space-time categories that consider the possibility of intervening during the development of the critical event, which consists of a before, a during, and an after. It is about facing and reacting to critical situations differently.

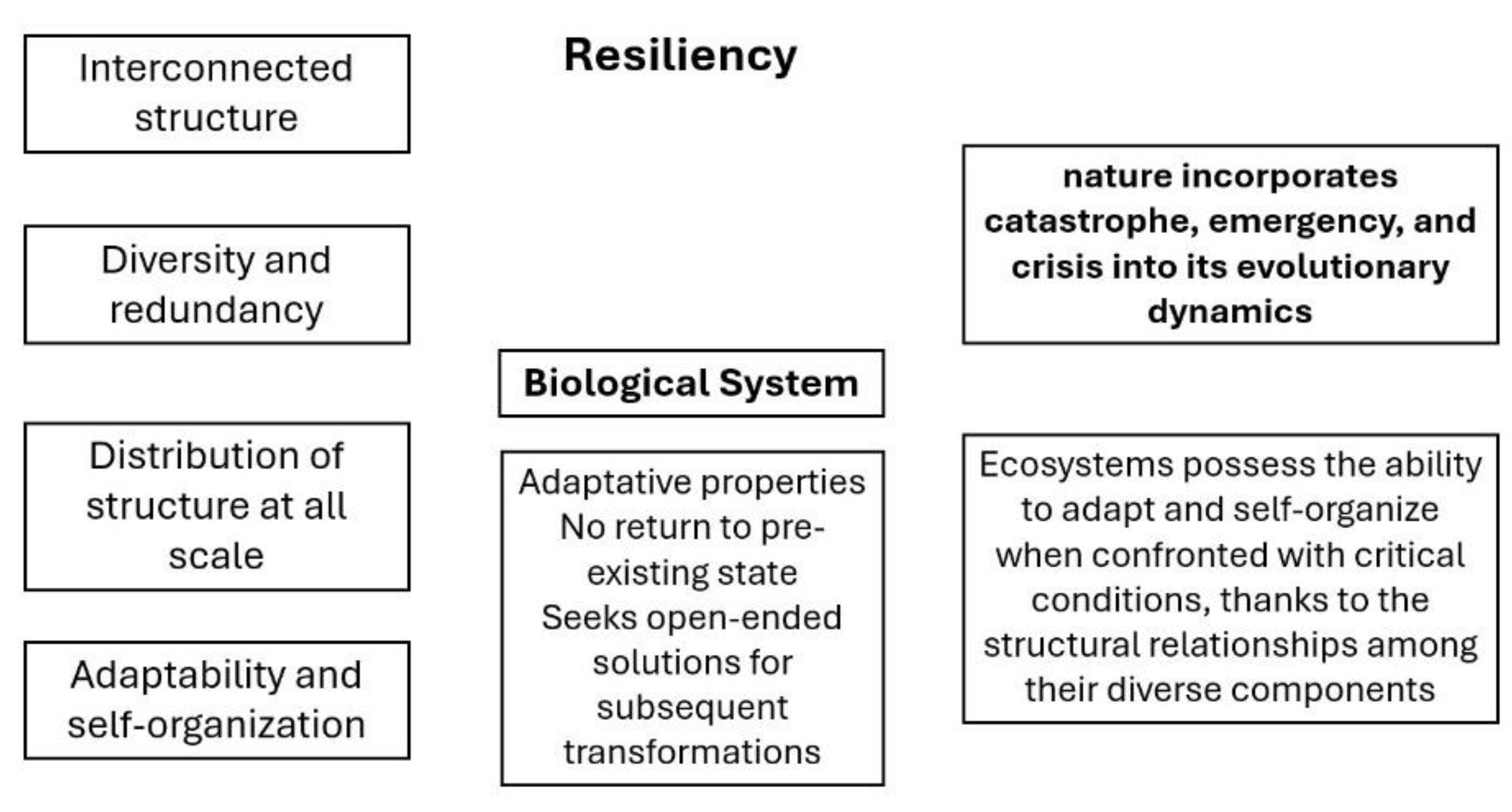

This leads to a discussion of the concept of resilience, a term that is currently misused and mistakenly equated with sustainability, which originally emerges in engineering and biology. In engineering, it denotes the property of certain materials to restore their original shape after undergoing deformation, while in biology, it signifies the capacity of a system to respond and adjust to an unforeseen and sudden critical condition. The biological interpretation of resilience appears particularly pertinent concerning architectural and urban aspects.

In an interesting essay titled “Toward Resilient Architecture” [

10] (pp. 1-5), Michael Mehaffy & Nikos A. Salìngaros explain the concept of resilience in architecture based on biological studies. They ask: What can we learn from biological systems? Through the example of a tropical forest, they respond to the question by highlighting the complexity, diversity, and multiple relationships among its components. They also affirm that many tropical forests remain stable despite the critical events that frequently threaten these realities. How is this achieved, and what relation does it have to the built environment? There are four indicators of biological systems that seem possible to relate to urban realities:

(1) they have a network structure;

(2) they exhibit diversity and redundancy;

(3) they show a wide distribution of structures at all scales;

(4) they have adaptability and self-organization capabilities.

Aspects that the modernist functionalism of the 20th century, related to industrial innovations, the myth of the automobile, and the use of fossil fuels, has strongly damaged. Modernist ideas, subsequently, have been instrumentalized by the global consumer society.

When examining the cited article, it becomes evident that four key points regarding our cities need further exploration:

Network Structure. Biological systems present interconnected structures, where the relationships between parts guarantee the survival of the whole: if one tissue is damaged, the system continues to function and, thanks to mutual support within the network, it can regenerate. Modern urban planning promoted an idea of a rational city subdivided into well-defined zones according to activities. The persistence of this system over time has weakened the urban structures.

Diversity and Redundancy: These features describe interconnected and adaptable elements of the network, akin to redundant organs in the human body. They ensure resilience and adaptability, contrasting with modern urban planning’s emphasis on uniformity. Spontaneously developed environments retain these qualities, fostering adaptability for survival.

Distribution of Structures at All Scales: In nature, smaller-scale structures compose and support larger-scale ones, such as fractals. If the system is damaged, it is easier to initiate its regeneration from the smallest cells. The same occurs in urban realities, where different scales of intervention should be interconnected and related to each other. Modern and contemporary architecture has increasingly encouraged a separation between different scales: architecture has become an isolated object.

Adaptation and Self-Organization. This aspect is referred to the capability to conserve and rebuild pre-existing models to compose more complex ones. This refers to what in biology is called genetic memory. This relationship between the original structure and the new emergent systems is crucial and is nowadays sidelined in favour of replacing the existing by the tabula rasa practice.

What emerges from this comparison with the biological realm is that nature incorporates catastrophe, emergency, and crisis into its evolutionary dynamics. Ecosystems possess the ability to adapt and self-organize when confronted with critical conditions, leveraging the structural relationships among their diverse components. These relationships, as emphasized, remain cognizant of their origins while driving the emergence of novel conditions.

Considering the research conducted thus far, it is evident that the disciplines of architectural, urban, and landscape design must integrate emergency, catastrophe, and crisis as variables within the project process for the transformation of spaces. This sets the stage for a potential paradigm shift in architectural and urban design, transcending the reliance on ad-hoc relief measures by embracing the concept of resilience. Resilience, characterized by its adaptive properties, does not envision a return to the pre-existing state following sudden changes but rather seeks open-ended solutions for subsequent transformations.

A pivotal advancement in this regard involves conceptualizing the project as an ongoing process, responsive not only to modification requirements but also to the specific conditions of risk and vulnerability recognition. Thus, it becomes apparent that the disciplines of design need to cultivate a direct association with the concept of resilience.

(Figure 6)

These final considerations introduce the next term in the catastrophe taxonomy:

The term project, derived from the Latin Projèctus, a compound word consisting of Pro, meaning forward, and Jàcere, meaning to throw, signifies the action of moving forward or, more precisely, advancing something to be carried out in the future.

The term process, from the Latin Procèssus and Procèdere, implies advancing or progressing concerning a preceding condition. It also denotes a series of actions or events that explain a situation.

In relation to the ongoing research, this brief etymological excursion helps understand the importance of conceiving the project as a process in space and time. Fundamentally, a project involves planning something to be carried out in the future. Traditionally, in architectural disciplines, the project has been conceived as static: it is envisaged and constructed according to a predetermined form. However, contemporary complexity necessitates departing from this static approach, particularly in disciplines related to urban modifications at various scales.

It is easy to comprehend why: a project considers a specific moment in the future when the work will be carried out but does not account for what might happen between the present and that future moment. For instance, all post-disaster reconstruction projects promise to return places to populations within 5/10/15 years. However, where will these people be in the meantime? What will happen in these places? Will the interventions consider the possibility of the catastrophic event recurring? Strategies applied in recent catastrophic events, both in emergency and post-emergency conditions, often lack a comprehensive view. They tend to focus on the event itself without considering the broader aspects involving transformations of the landscape whether anthropic, natural, cultural, or social.

It is evident that critical phenomena can no longer be considered solely at the moment of their manifestation but must be integrated into the project process. This underscores the importance of the temporal factor. As mentioned earlier, the frequency of emergencies is increasing, necessitating the consideration of space as a constantly changing entity and observing phenomena as they evolve, without waiting for them to manifest violently and destructively. From this shifted perspective, the project must be viewed as a resilient process capable of adapting to changing circumstances over time.

Rather than a project defined in all its aspects, there is a preference for what French landscape architect Michel Desvigne calls “intermediate natures.” These are deliberately incomplete interventions, an evolutionary and flexible first layer [

11] (pp. 11-13), providing greater freedom to adapt to future transformations. According to Desvigne, these “intermediate natures” are not isolated elements dictated by momentary needs, but parts of a complex system deeply connected to the site’s underlying structure, capable of adapting and assuming transitional forms based on contextual needs.

Within this procedural approach, the speed associated with an emergency does not primarily refer to immediate action but to the system’s capacity to adapt to the unexpected new condition.

“Today, the project (as a process) leverages this possibility, controlling time and becoming an indispensable tool for shaping, or reshaping, a reality in constant evolution and often subject to violent and sudden transformations” [

12] (pp. 10-13).

Instead of a project defined in all its aspects, there is a gradual adoption of a different conception that does not anticipate a future condition but prepares the system so that a wide range of possibilities can be configured as responses to contingent needs. Mehaffy & Salìngaros [

13] (pp. 1-4) explain this paradigm shift by referring to a software programming system called “Agile.” This system does not specify expected behaviour but determines the conditions under which such behaviour is likely to emerge. It is a genetic-generative vision where the future condition is not chosen in advance but emerges from the interaction and self-organization among components activated when the system transitions from stability to instability.

(Figure 7)

- 6.

Reconstruction vs Regeneration.

In the face of catastrophic events that cause significant destruction and criticalities across physical-spatial, socio-cultural, and techno-environmental levels, the discourse often revolves around reconstruction. In most cases, this presupposes the restoration of the system to its pre-disaster condition. The notions of “how it was” and “where it was” have been prevalent attitudes that carrying with them all the problematic implications of such an approach. It appears that the predominant intent is to erase from both individual and collective memory the tragedy wrought by the catastrophe. There is a desire to rewind the tape of time and pretend that nothing occurred. Unfortunately, this is not possible because time does not turn back, and events cannot be undone; it is necessary to accept the loss and process the absence, carrying out what the Swiss philosopher Nicola Emery calls “ grieving process”.

It is necessary to feel the loss, to suffer its pain, to recognize it. By drinking until the bitter end the cup of absence of the person, the object, the place, (...) our capacity to love, over time (...) can be compared to the world, replacing what has been lost by adopting new forms (...). The basis of this elaboration is then also a separation, a maturation that allows for a reinvestment. Grieving process does not have to hide the temporal distance, but rather embrace it, calculate it in detail, and learn from it the action and the debris [

14] (p. 230).

Desiring to restore the situation to its pre-calamity state is a universal aspiration deeply ingrained within individuals. It serves as a natural response to confront the fear and uncertainty brought about by loss. However, amidst this desire, it becomes imperative to pose pertinent questions. Would reconstructing the place exactly as it was before preserve its original stories, frameworks, and nuances of everyday life? Does the restoration of a historic building retain its intrinsic cultural value? Or the risk is to replicate a mere exterior image, neglecting the passage of time, the narratives, and the indelible imprints that places accumulate over their lifetimes?

Traces, scars, symbols, and frameworks constitute integral components of a place’s DNA, offering the knowledge into its origins constitute the “little that remain”, as Walter Benjamin [

15] say, upon which one can anchor themselves to initiate a new cycle. This transformation does not entail a literal reconstruction of the former state, but rather the establishment of a novel network of relation that assimilates past elements within the new condition.

The problem of reconstructing without memory implies cutting part of the DNA of a place and causing an irreconcilable space-time fracture. A regenerative attitude capable of interacting with what remains and operating in a generative and resilient manner, should be preferred.

A necessary condition for a regeneration process to occur is its ability to consciously or by contrast, insert itself into the history of the city that hosts it, somehow picking up the threads of its life. Regenerating itself, for a city, does not simply mean expanding or renewing itself, but rather reconnecting, even if only punctually, with its destiny, which, although rooted in the past, is always subject to modification based on the conditions determined in the present [

16] (p. 40).

In this citation, it is important to highlight two fundamental issues. The first is the regeneration’s capacity to integrate into reality and to resume the threads of the city’s life. This refers to the need for interventions that are grounded in the depth of the context, where it is possible to find the “original material” referred to by Carlos Martí Aris [

9].

The second issue coincides with the juxtaposition of the term’s “reconnection” and “destiny.” The former is related to a past condition, while the latter pertains to the realization of a future that seems already predetermined. It is as if the destiny of a place were predetermined at the moment of its inception. However, it is at this point that the author introduces a clarification stating that destiny is not immutable but rather susceptible to multiple transformations arising from conditions of discontinuity.

From an etymological standpoint, Regenerate derives from Latin and means to generate again. It is composed of two words: Re, which denotes repetition, and Genesis, referred to origins, to how and where things have begun. Thus, Regeneration should be interpreted as a new genesis. A new start that is not absolute, but rather relative, as the regenerative process delves into the layers that have accumulated over time in a discontinuous manner, aiming to unearth resilient elements with which to establish new relationships.

A New Paradigm

The taxonomy conducted highlights that the etymology of the terms reveals alternative possibilities to the practices currently being applied in the face of a catastrophic event. On one hand, the etymological journey emphasizes the search for the genetic and generative aspects of places, as well as the need to move from project as a static forecast of the future to processes that are temporally and spatially open, capable of adapting to unexpected emergent conditions. On the other hand, everyday reality, given the intensification and implementation of new catastrophic events, requires alternatives that can operate adaptively and genetically in contexts, as current protocols function in a fragmented manner, with each discipline acting independently and perceiving a lack of integration among the different spheres called upon to intervene.

Disciplines such as architectural, urban, and landscape design typically intervene in the phase following the emergency, known as the reconstruction phase. This temporal and disciplinary segmentation has resulted in outcomes that are less related to the place itself than to the population, leading to further destruction through new constructions. The practice of emergency management, which demands swift and necessary interventions in the face of disaster, leaves little time for conducting in-depth evaluations of the characteristics of places and the culture of the population inhabiting them.

It seems then necessary to make a paradigm shift capable of supplanting an obsolete, untimely, and partial practice, with a holistic and genetic approach. It is about inserting into the places a resilient regeneration processes that is related to their deep structure, that establish an interactive network with other disciplines, that is adapted to new conditions, and that open to new configuration principles.

This implies initiating a profound modification of architectural, urban, and landscape projects, transitioning from being static to dynamic, both spatially and temporally, and internalizing the aspects of emergency, crisis, and catastrophe. Contemplating the unforeseeable in general, and catastrophes in particular, requires conceiving a project as an open process to multiple possibilities that cannot be determined a priori but will emerge as “becoming” configurations from the interactions of system components.

According to this view, the environmental system - natural and artificial - should be predisposed to activate and adapt to various types of catastrophic events, not responding to calamities solely after the fact and through predetermined models typical of emergency management, but with increasingly different configurations to the specific needs of the case.

The first paradigmatic innovation consists of recognizing that the disciplines of architecture, urbanism, and landscape architecture should not only intervene during the reconstruction phase but are already operating under normal conditions and are always active. In this new vision, there are no cycles composed of rigid and perfectly differentiated phases that always repeat themselves in the same way in space and time; instead, there is a process composed of cycles that do not close in on themselves but rather open up to new transformations. Rather than closed circles, one could speak of concatenated and interactive circles, following the logic promoted by the American architect William McDonough [

17] called “cradle to cradle”, which not only envisions the transition from one condition to another with minimal energy waste but also employs actions of reuse, reversibility, and multifunctionality as part of the modification process.

To summarize, the fundamental points of the new paradigm of urban architectural and landscape design in relation to catastrophic conditions are:

1. To shift from a sectoral conception of post-catastrophe intervention to a holistic, genetic, and integrated design practice across disciplines.

2. To move from a protocol of rigid phases to an open process that integrates catastrophe and emergency into design variables.

3. To predispose places for evolving adaptations through the implementation of necessary tools. The response to a critical condition will emerge from the interactions among the elements composing the system and will activate in reaction to the criticality presented.

4. To emerge of a new system. On the one hand, it is related to the deep structure of the place, the genetic elements; on the other hand, it opens up to the future needs that the modification requires, acting through new dynamic principles.

4. Discussion

At this point in the research, it becomes clear to inquire how to achieve the occurrence of the new paradigm. What strategies and methods to implement to confer upon places the capacity to activate and react to a condition of criticality? To answer these questions, the research defines three open and subsequent methodological steps that can be defined as pre-catastrophe, but which actually refer to an idea of urban, architectural, and landscape design that internalizes the possible appearance of catastrophic phenomena. Subsequently to these methodological steps, some principles of predisposition of places are drawn up, derived from studies conducted by M. Mehaffy and N.A. Salìngaros [

18] (pp. 1-4) on the geometric properties defined by Christopher Alexander in the text “The Nature of Order” [

19].

The step-by-step methodological include:

Contexts reading.

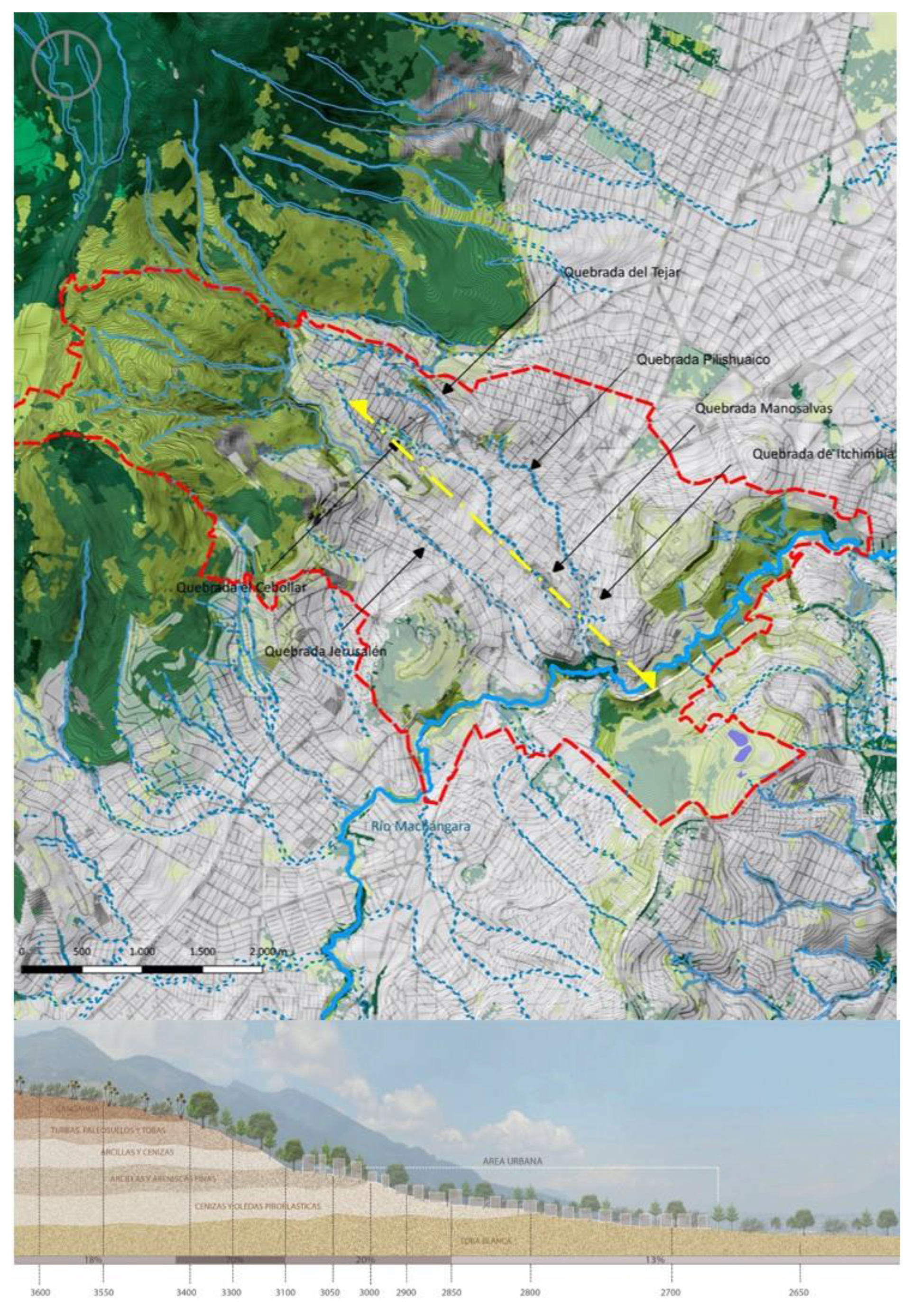

Figure 8.

Interpretative reading of Quito’s geomorphological and hydrographic structure. The map highlights the network of main quebradas (in blue) and the relationship between geomorphological units and urban growth. The red line marks the urban boundary, while the section below illustrates the steep slope gradients and volcanic soil layers of the Andean plateau, revealing the city’s structural fragility and exposure to hydrogeological risk.

Figure 8.

Interpretative reading of Quito’s geomorphological and hydrographic structure. The map highlights the network of main quebradas (in blue) and the relationship between geomorphological units and urban growth. The red line marks the urban boundary, while the section below illustrates the steep slope gradients and volcanic soil layers of the Andean plateau, revealing the city’s structural fragility and exposure to hydrogeological risk.

This involves collecting quantitative and qualitative data from the sites to be intervened and organizing them into measurable and comparable categories.

(Figure 8) The information can be organized through traditional tools such as maps, sections, and three-dimensional models, but also through dynamic infographic systems that allow not only to understand the current situation but also the temporal variation of the collected information. The temporal variable is crucial for understanding the future trend of the site.

It is essential to gather information related to different types of risks in their three variables: types of threats and their relative degree of vulnerability and exposure. Along with information about risks, it is essential to collect physical-spatial, socio-cultural, and techno-environmental information broadly, not only from the specific intervention area but also on a scale that allows understanding the reference system of the context to be intervened. In this case, the information must be multiscale to cover both the broad and the most specific scope.

Regarding the three mentioned categories, the intention is not to define what data to collect, but rather to highlight that the information encompasses from recognizing basic space categories to different scales to the degree of land artificialization, energy resource use, and pollution levels in urban and natural environments, among others.

The information to be collected requires the collaboration of multidisciplinary teams of professionals, such as architects, urban planners, landscape architects, engineers, geologists, geographers, anthropologists, psychologists, etc. These professionals are called upon to collaborate to develop as comprehensive and interdisciplinary a database as possible.

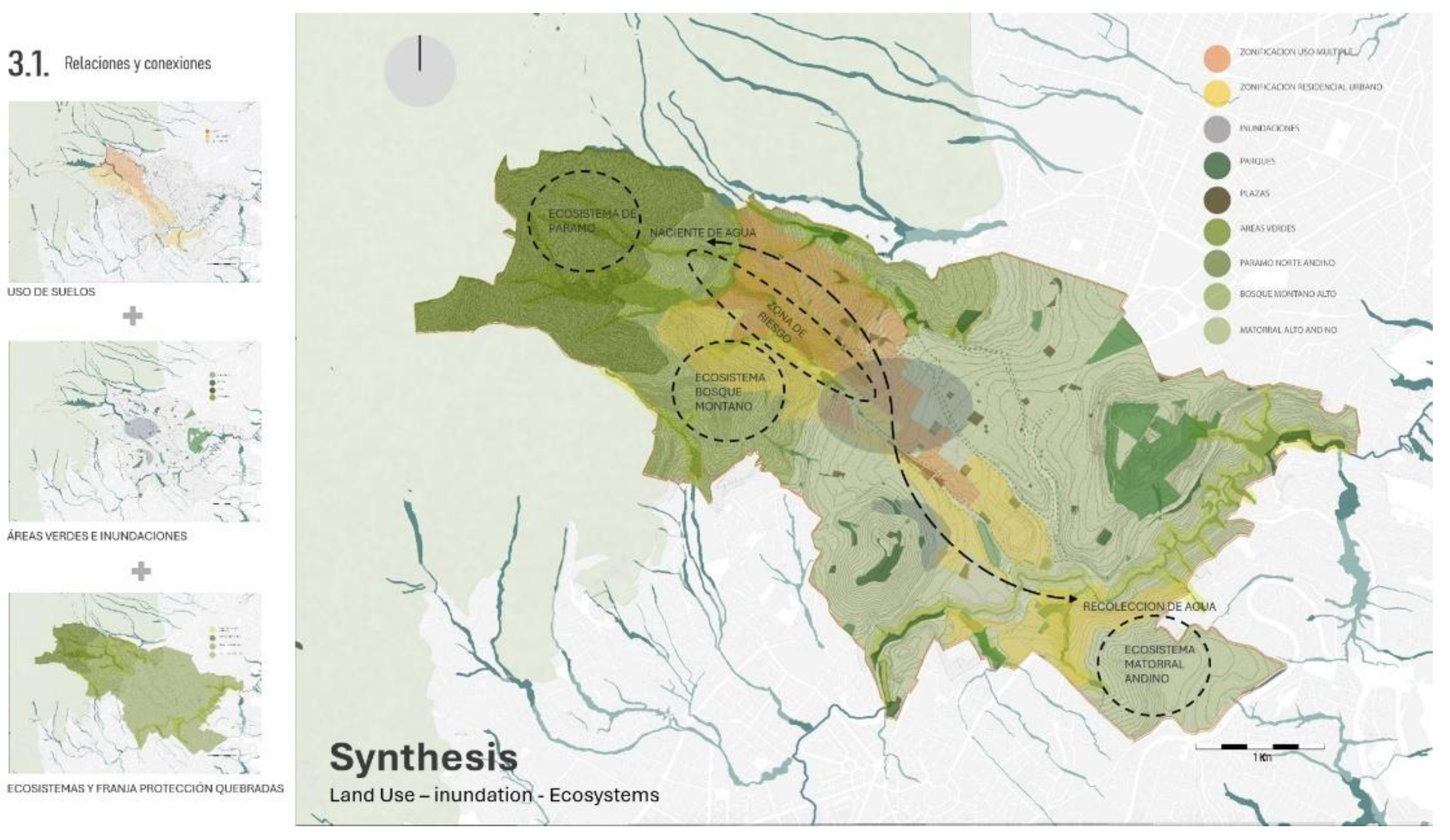

Interpretation of Data and Identification of Areas Sensitive to Modification.

Figure 8.

Synthesis of threats, ecosystems, and mobility in Quito.The map overlays geological hazards, vulnerable populations, and ecosystem protection zones, highlighting the intersections between environmental risk, social fragility, and infrastructure. It identifies critical corridors for public transport and green infrastructure, suggesting integrated strategies to enhance resilience through mobility and ecological connectivity.

Figure 8.

Synthesis of threats, ecosystems, and mobility in Quito.The map overlays geological hazards, vulnerable populations, and ecosystem protection zones, highlighting the intersections between environmental risk, social fragility, and infrastructure. It identifies critical corridors for public transport and green infrastructure, suggesting integrated strategies to enhance resilience through mobility and ecological connectivity.

The interaction between risk data and the various layers of data collected in the initial step allows for an interpretation that provides fundamentally important information in the event of catastrophes. Interpolating physical, social, economic, and environmental data leads to valuable conclusions that must be considered in disaster scenarios.

(Figure 9) For instance, identifying safe areas solely based on their distance from risk zones is insufficient. Such decisions overlook crucial aspects of sustainability, encompassing both environmental and social considerations, such as access to basic services, connectivity to key facilities and infrastructure, as well as the psychological impact on the population.

An analysis through data layer superimposition may reveal that in the past, emergency and catastrophe were not considered as design variables. Indeed, it becomes evident that areas deemed safe often fail to meet the needs of the population or are not easily accessible. Conversely, they may be situated in desirable locations but require significant interventions to function optimally, or they may be vulnerable due to disregarded trend factors. On the other hand, it is important to understand the characteristics of areas at risk in order to intervene effectively, transforming them from areas considered dangerous for the population into regions that contribute to reducing both vulnerability and exposure to catastrophic events.

Another aspect that could be identified is the necessity to locate areas capable of disaster response in strategically important regions across different scales: from towns and cities to rural or natural territories. This aims to establish networks of spaces capable of optimizing infrastructure and resources in the face of calamities. It entails identifying central nodes and networks that design a multipolar and multiscale system. Such a system should foster the emergence of a new geography of resilience, connecting resistant and resilient polarities.

These considerations underscore the importance of understanding information systemically and across multiple scales, as well as fostering interaction between the scientific community and the social community (including the population, municipalities, and public entities) to initiate an integrated planning process for territories.

Predisposition of places: Principles of adaptability and resilience geometries.

Once the most optimal areas have been identified, through the interpolation of spatial, social, economic, and environmental indicators, it is crucial to transform them into resilient locations, endowing them with the capacity to adapt and evolve over time and space to assume other potential roles. The aim is to provide these places with greater adaptability to respond to the specific demands of each situation of need. In this perspective, sites showing suitable characteristics according to the previous study should be predisposed as landscape-infrastructural backbones (continuous or discontinuous), capable of redefining urban, natural, and productive landscapes according to integrated principles related to the specificities they will face.

This constitutes a first evolutionary and flexible stratum [

11] (pp. 11-13), meaning a system for constructing contexts that accommodate useful social functions but can also, in emergencies, adapt to new conditions and generate a new structure that integrates with the old, causing transformation. Once the areas have been identified, urban and landscape planning, under normal conditions, should not only intervene in these emerging centralities but also address the space between nodes, applying organizational principles that facilitate the configuration of a multipolar system.

How to predispose the places? In the paragraph dedicated to the concept of resilience, the four characteristics of a resilient system have been highlighted: diversity, network structure, distribution of structures at all scales, adaptation, and self-organization.

(Figure 9) These characteristics, common to resilient systems, are indicators of an adaptation process that determine an evolutionary diversity [

18] (pp. 2), which Christopher Alexander [

19] (p. 229) defines as adaptive morphogenesis, i.e., the generation of forms obtained through a step-by-step process of successive transformations. From the study of the fifteen geometric properties defined by Christopher Alexander in the text “The Nature of Order” [

19] (p. 143-242), Mehaffy and Salìngaros develop some geometric categories that relate to the characteristics of resilient systems and that in this research are considered as a starting point for the development of four design principles for predisposing places.

1. Weaving of matrix.

(Figure 10) Diversity is established through small modifications through successive adaptations. Christopher Alexander critically refers to systems that exhibit perfect symmetries; in fact, no living organism displays absolute symmetry in nature. Small differences provide diversity and greater strength to a system. Therefore, from this consideration, it can be thought that each transformation nucleus should be implanted on a geometry that moves away from a static idea of perfection, breaking the symmetry of an absolute geometry inserted a priori in the place (such as a camp of containers) to seek relationships with the context (deep interlock and ambiguity) and work with the boundaries through the weaving of a variable intervention matrix. This matrix is composed of elements of repetition and variety (patterns) that define the rules (alternating repetition) and exceptions of the fabric (contrast). According to this perspective, each transformation nucleus is not a centre but a multiscale open system with a dynamic rule for constructing architectural, urban, and landscape space.

2. Networks’ Multiplication. The components of the transformation cores, from the smallest to the largest (level of scale), will be interconnected to generate a balanced and hierarchical system of relationships. Within this hierarchy, elements of greater (strong centre) and lesser strength will do not crush each other but rather support each other. Additionally, the system does not only relate to its internal aspects but also extends outward (positive spaces), seeking connections with both the context and other centralities, to construct networks between centralities. This network system needs to have more connections than necessary; in the event of a crisis, if some infrastructures fail, others can compensate for the shortfall. Both in the cores and in the system of connection between them and the context, it will be necessary to establish reserve networks that provide the system with the ability to produce and store energy, collect water, eliminate waste, and physically and virtually connect places and people.

(Figure 11)

3. Relationship between structures. In nature, similar forms distributed across different dimensional levels are found, known as fractals. For instance, the trunk of a tree resembles that of its branches, which in turn is akin to that of smaller branches. The structure of the “tree system” repeats at various levels, with each level structurally related to both the larger and smaller scales. This bestows upon biological organisms’ greater durability and adaptability to the unexpected. Structural repetition at each level allows for increased resilience: the falling of one or more branches may occur, but not the overall collapse of the organism. The presence of a complex and multiscale structural system enables the whole to continue functioning and regenerate. Through this example, the intention is to underscore the need to endow the contexts with a structural system capable of operating at different scales, from the territorial to the architectural. This does not entail replicating identical forms in different sizes, but rather generating multiscale and multitemporal structural relationships. This is related to what has previously been termed as structure of form: it involves identifying within transformational sites those genetic-structural aspects that allow the new to anchor to the existing, enabling that in the face of catastrophic events the necessary modifications will be hold on to the deep structure of the place facilitating site regeneration based on its constitutive aspects. Analogous to what occurs in the biological realm, this relationship with the DNA of places allows for dynamic transformation, not extemporaneous, isolated, or punctual, but rather a variation linked to the deep aspects of places and the genetic sequence of modification over time. Even if the system is compromised, genes of potential variations, previously embedded in the DNA of the place, will know to activate and promote transformation in accordance with the physical-spatial, sociocultural, and techno-environmental context.

Figure 12

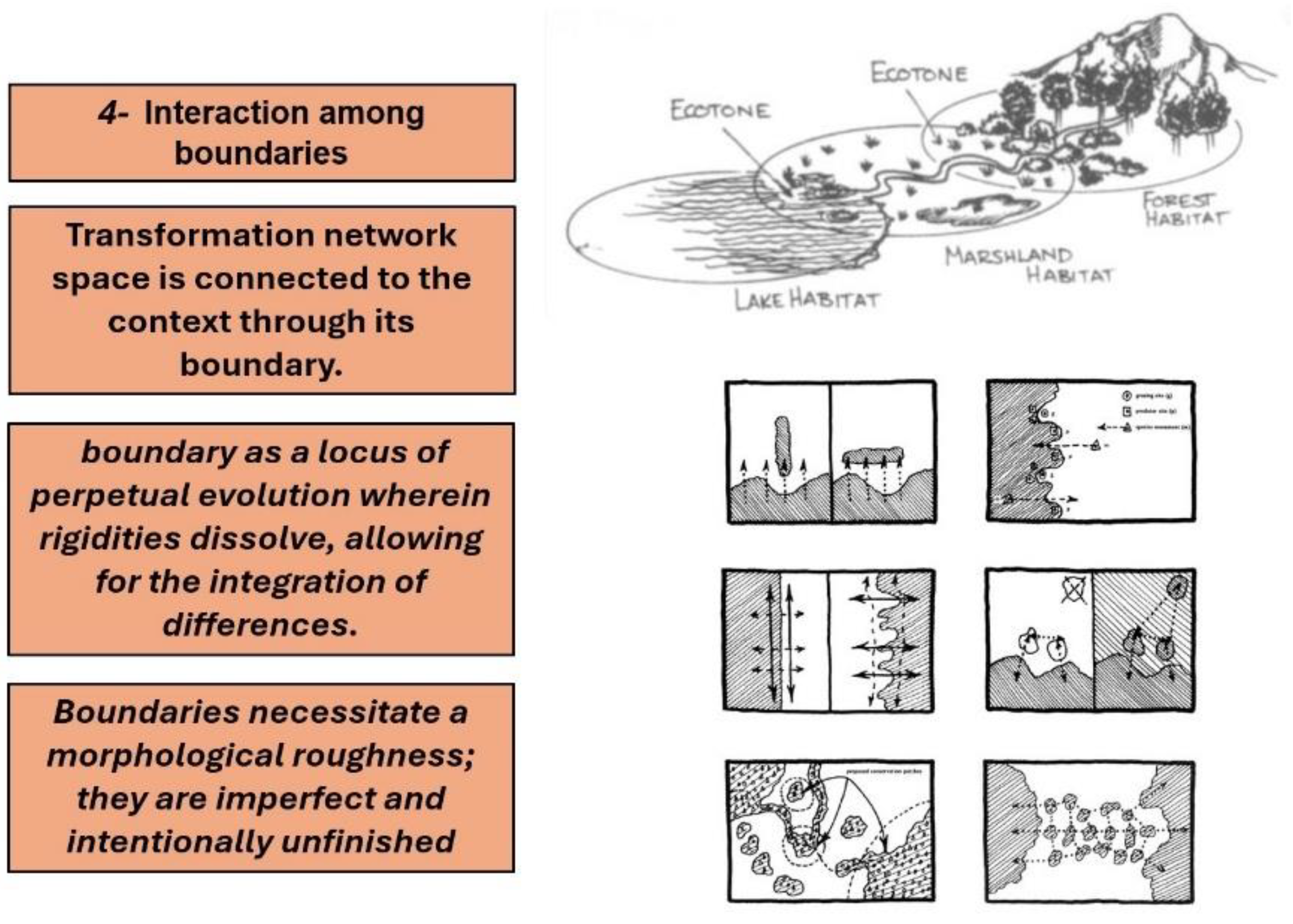

4. Interaction among boundaries. Transformational cores, as previously asserted, do not exist in isolation; their efficacy resides precisely in their capacity to reconnect with the context, thus highlighting the pivotal role of boundaries. The concept of a boundary is wide and has often been interpreted with a negative connotation: it is within the boundaries of divergent realities that differences, oppositions, and contrasts converge. While a boundary may initially appear as a site of conflict and hazard, it is the very process of encountering and resolving these conflicts that imparts a unique character to the boundary, rendering it a transitional space between opposing forces. Consequently, the boundary can be construed as a locus of perpetual evolution wherein rigidities dissolve, allowing for the integration of differences. The term “boundary” originates from a fabric woven with intersecting stripes. Boundaries necessitate a certain degree of morphological roughness; they are imperfect and intentionally unfinished, as they must accommodate the diverse influences emanating from beyond the boundary or transiently passing through it.Authors should discuss the results and how they can be interpreted from the perspective of previous studies and of the working hypotheses. The findings and their implications should be discussed in the broadest context possible. Future research directions may also be highlighted.

Figure 13

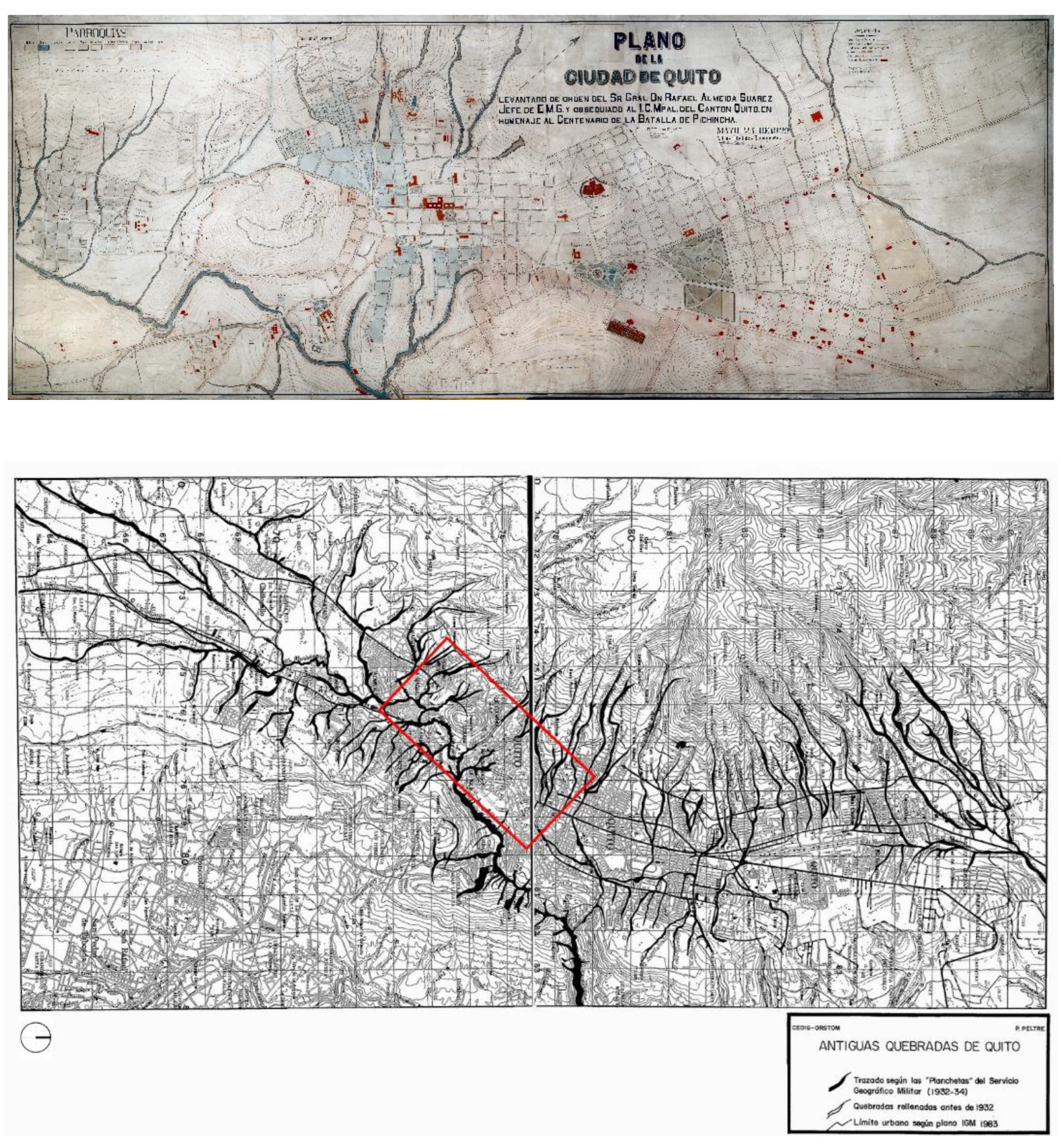

Quito as Case Study

This step-by-step methodologically approach, in order to be verified and improved can be applied on the city of Quito. The methodology would allow a simultaneous vision of the relationship between the original geo-morphological condition, the urban development over time and the conditions of morpho-climatic risk that make up a general framework of exceptional fragility [

20] (pp. 132-139). Given the significant number of ravines present within Quito’s urban fabric, the objective is to codify the physical-environmental, sociocultural, and technological-environmental characteristics of each ravine to define a dynamic Urban Code of behavior for ravines and the surrounding territory in the face of catastrophic events, assessing their criticalities and potentialities.

Starting from the current status Code, is it possible begin to define a multipolar network of intervention sites upon which multiscalar transformations can be implemented to address various types of threats. These transformative actions alter the current status Code, yet do not impose a singular configuration; rather, the transformation of the Code remains Open in space and time, as each transformation is contingent upon surrounding conditions and aims not to revert to a previous state but to adapt to emerging conditions and pave the way for possible subsequent changes.

This phase of experimental verification is in its initial stages of information gathering.