1. Introduction

The Landscape ecology, first conceptualized by Carl Troll in 1939, has evolved into a transdisciplinary science at the intersection of ecology, geography, conservation biology, and spatial planning [

1]. By analysing the interactions between spatial pat-terns and ecological processes, it provides a robust framework for understanding ecosys-tem dynamics under anthropogenic pressures [

2]. Since the 1980s, the field has expanded rapidly through innovations in remote sensing, geospatial analy-sis, and multiscale modelling approaches [

3,

4,

5].

Yet, the foundational assumptions and paradigms underpinning landscape ecology have largely emerged from relatively stable socio-ecological contexts in the Global North [

6]. In contrast, the DRC presents a fundamentally different set of land-scape dynamics—both biophysical and institutional—that challenge these frameworks [

7]. The DRC hosts the second-largest tropical forest massif on Earth, characterized by exceptional biodiversity, vast ecological heterogeneity, and complex hu-man-environment interactions [

8]. However, this landscape is pro-foundly shaped by structural instability: recurrent armed conflicts, governance vacuums, weak institutional oversight, and intense reliance on natural resource extraction [

9,

10].

Such conditions have produced hyper-fragmented ecosystems, where industrial and artisanal mining, illegal logging, conflict-affected forests, and unplanned urban sprawl intersect chaotically [

11]. For instance, in mining-rich regions like Katanga and Tshopo, overlapping concessions and protected areas cause abrupt forest loss [

12,

13,

14,

15,

16], habitat isolation [

17], and soil contamination [

18,

19]. The lack of effective spatial planning fosters anarchic urban expansion, further fragmenting peri-urban ecosystems [

20]. These spatial configurations serve as natural laboratories for studying ecological tipping points and landscape col-lapse—phenomena inadequately captured by traditional, linear models of disturbance and recovery.

Moreover, post-conflict dynamics generate non-linear ecological feedbacks, as evi-denced by spontaneous reforestation during periods of armed insecurity when agricultur-al pressures temporarily decline [

7,

10]. These trajec-tories contradict classical degradation narratives and demand more adaptive and con-text-sensitive modelling frameworks.

A further defining feature is the complex interaction between global extractive pres-sures and local land-use practices. The expansion of industrial and artisanal mining of cobalt, copper, and timber often undermines traditional agroforestry systems, historically pivotal for maintaining biodiversity and soil fertility [

21]. Nonetheless, local ecological knowledge continues to mediate land-use decisions [

22], indicating that resilience in the DRC is simultaneously ecological, cultural, and institu-tional.

These unique empirical realities raise a disruptive theoretical question: How do Congolese landscapes—marked by extreme fragmentation, resource extraction, and gov-ernance vacuums—challenge dominant resilience paradigms such as the Press-Pulse Disturbance framework, which presumes linearity, institutional coherence, and predicta-ble recovery thresholds?

Since the mid-2000s, a growing body of research led notably by Professor Jan Bogaert and collaborators has begun to address these gaps. Through high-resolution spatial anal-ysis, biodiversity assessments, and participatory methods, this work lays the foundation for a critically reflexive, context-sensitive landscape ecology in the DRC. This article pre-sents a diachronic and critical review of landscape ecology research in the DRC from 2005 to 2025 (June, 30th). We trace its institutional emergence, thematic evolution, and concep-tual tensions, arguing that the Congolese case compels a fundamental rethinking of land-scape ecological theory in light of plural, uncertain, and politically charged ecological re-alities.

2. Landscape Ecology in the DRC (2005–2025): The Trajectory of an Emerging Discipline

Between 2005 and 2025, landscape ecology in the DRC has progressively established itself as a structured scientific field at the intersection of spatial analysis, functional ecology, and land management. This disciplinary consolidation was initiated by Professor Jan Bogaert, whose arrival in 2005 in DRC marked a foundational turning point. His pioneering contributions introduced a level of methodological rigor previously absent, while simultaneously fostering a collaborative research dynamic with local institutions.

The first wave of studies (2005–2012) laid the conceptual groundwork, focusing on forest fragmentation and the spatial structure of ecosystems in the Congo Basin [

12,

13,

23]. These investigations primarily employed GIS, landscape metrics, and highly quantitative analytical approaches. This exploratory phase was strengthened by targeted ecological assessments, notably examining the impacts of logging or mining activities and ecological connectivity loss [

24,

25,

26].

Between 2013 and 2019, the discipline entered a phase of maturation. Research priorities shifted towards the analysis of interactions between natural dynamics and anthropogenic pressures, with growing attention to ecosystem services [

27], (peri)urban dynamics [

28,

29,

30], and deforestation process modelling [

31]. This period also witnessed a gradual integration of social sciences, indicating a shift toward more cross-cutting, transdisciplinary approaches.

Since 2020, research has demonstrated methodological diversification and expanded analytical scales. The integration of climate change issues, prospective modelling, evaluation of protected areas' effectiveness, and ecological restoration strategies characterize this phase of scientific consolidation [

7,

14,

15,

16,

32,

33]. Studies now adopt holistic perspectives, articulating local and regional scales while developing decision-support tools for territorial planning [

11,

34,

35].

Professor Jan Bogaert’s most decisive contribution lies in the structuring of a scientific school in the DRC, grounded in analytical rigor and the training of a new generation of researchers. His approach, initially focused on the spatialization of ecosystems, has evolved into a systemic vision incorporating socio-environmental dimensions. Today, landscape ecology in the DRC stands at a critical juncture: it must both consolidate its scientific achievements and reinforce its societal relevance in order to become a strategic lever for conservation, environmental governance, and sustainable territorial development.

3. Scientific Dynamics of Landscape Ecology in the DRC (2005–2025)

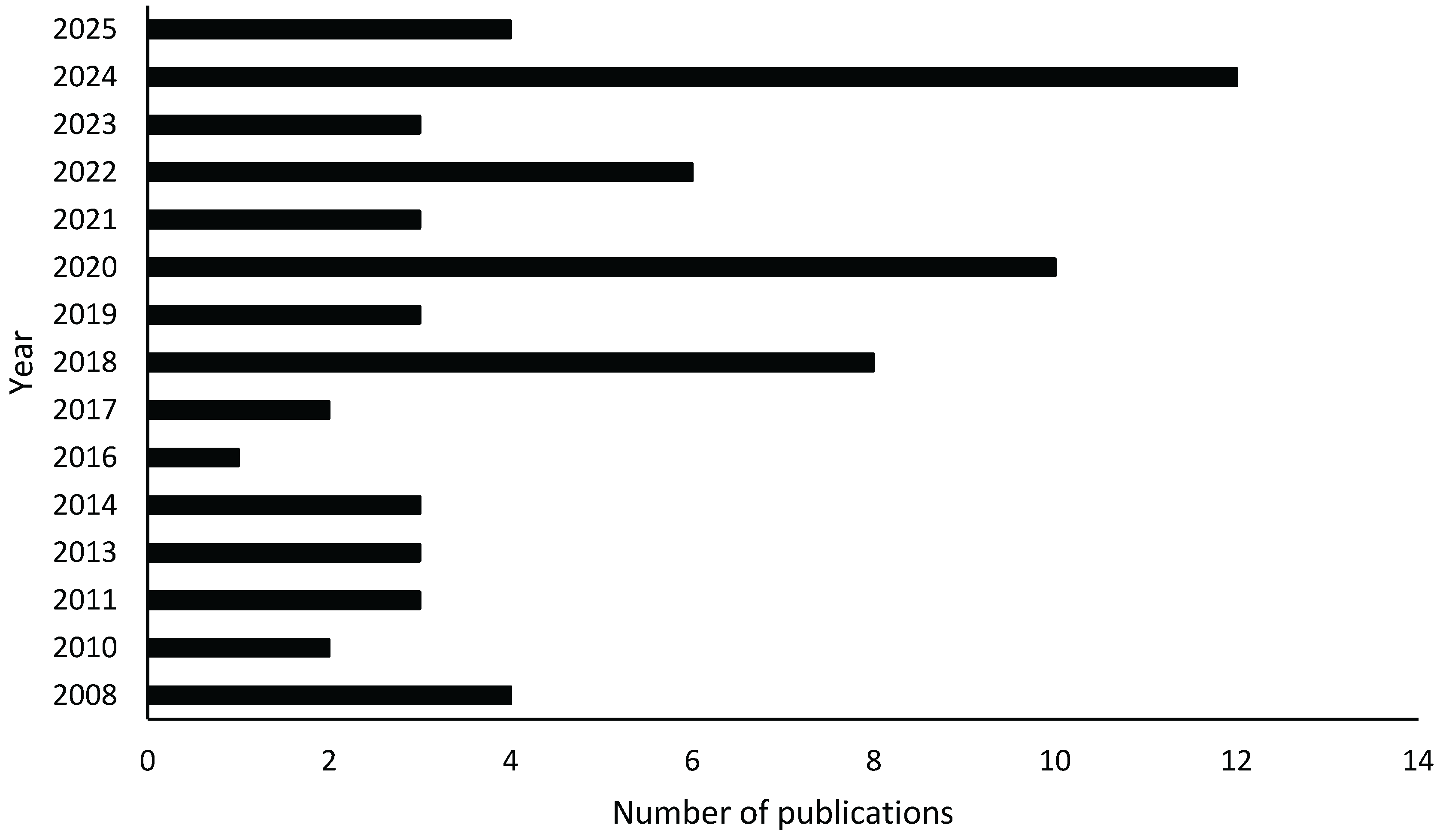

The trajectory of landscape ecology in the DRC since 2005 has been accompanied by a notable intensification of scientific output. Initially modest, this trend experienced a significant inflection from 2015 onward, driven by the growth of international collaborations and the structuring of multidisciplinary research programs. The years 2018 and 2020 represent peaks in publication activity, linked respectively to the release of major synthesis articles and the completion of high-impact integrative projects (

Figure 1). The year 2024, marked by a record number of publications, confirms this upward trend, reflecting both the increasing expertise of local teams and the alignment of scientific priorities with global environmental concerns.

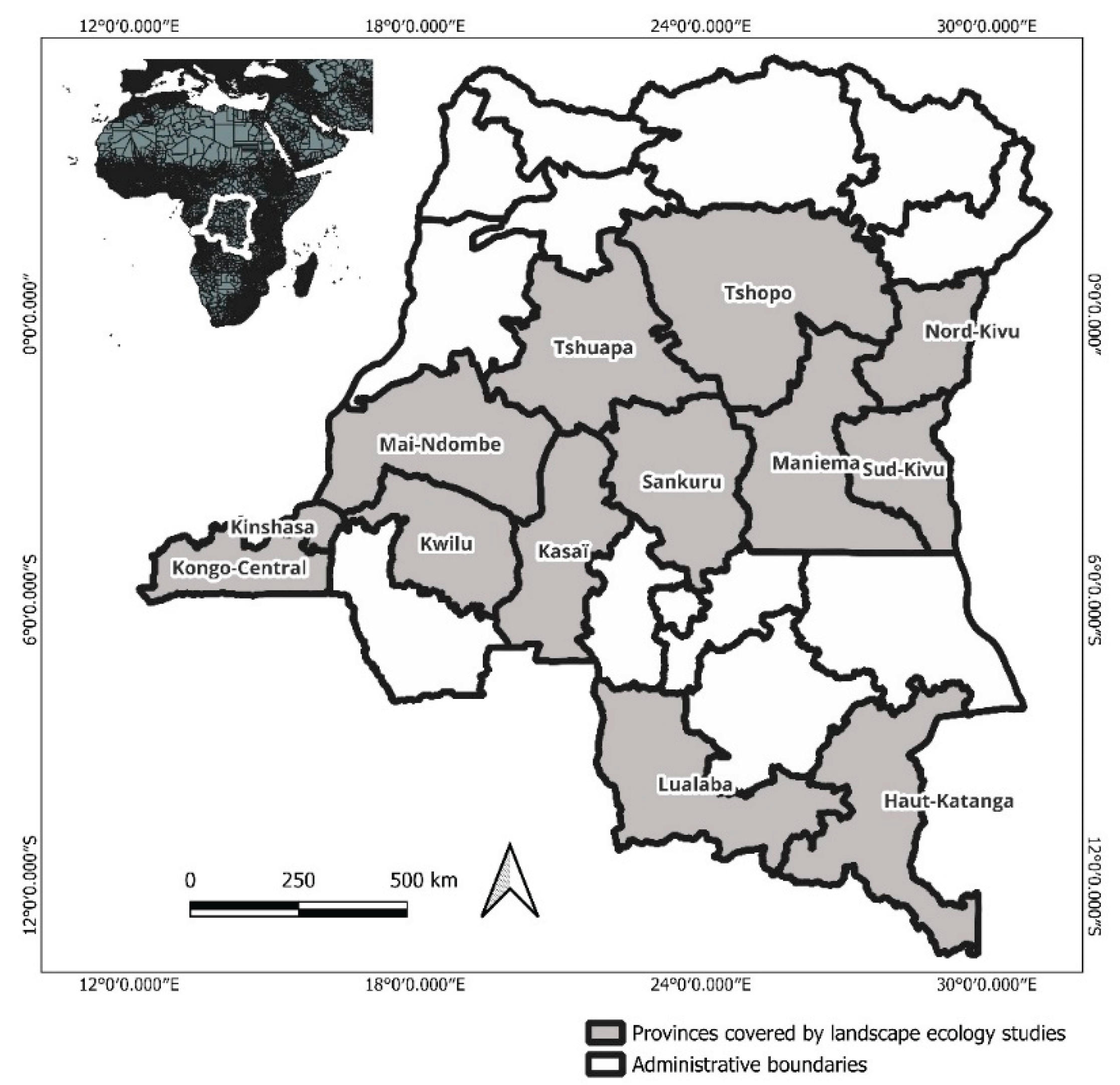

Spatially, early studies concentrated on emblematic regions such as the mining zones of Katanga and the peri-urban forests of Kisangani. Over time, the geographical scope has broadened to include agricultural landscapes, rural–urban interfaces, and buffer zones of protected areas, covering 50% of Congolese provinces (

Figure 2). This spatial expansion was accompanied by a methodological refinement, combining macro-regional analyses [

11] with fine-scale local assessments [

28]. However, some provinces—particularly in the western and northeastern regions—remain underrepresented, revealing persistent territorial coverage imbalances (

Figure 2).

Thematic diversification is also a defining feature of this evolution. While forest fragmentation dominated early research [

23,

36], current investigations address a wider range of topics: ecological regeneration, functional connectivity, urban landscape dynamics, agroforestry systems, and the functioning of ecosystems [

37,

38,

39,

40]. This evolution signals a transition toward a systemic reading of socio-ecological interactions.

In parallel, the editorial landscape has undergone a significant transformation. From an initial focus on local publication outlets [

23,

26], Congolese landscape research has gained visibility in international indexed journals (

Table 1). This internationalization has been accompanied by increasing thematic and methodological specialization across publication venues. Among the most frequently cited sources, the journal Land leads with 15.1% of the studies, followed by Tropicultura (12.1%) and collective volumes published by the Presses Universitaires de Liège, particularly those focusing on forest anthropization. A clear trend is also emerging in recent publications (2020–2025), with journals such as Land, Diversity, and Remote Sensing—all published by MDPI—being increasingly favored by researchers in the field. Changes in language practices also reflect this disciplinary evolution. While French historically predominated, English has become the dominant language in recent publications, particularly those appearing in international journals (total 35 publications out of 67). This linguistic shift—uneven across institutions and disciplines—demonstrates a growing intent to integrate into global academic circuits while maintaining functional bilingualism.

Finally, methodological innovations have decisively contributed to the increasing complexity of analyses. Traditional techniques have been complemented—and in some cases supplanted—by advanced digital tools such as remote sensing, spatial modelling, and sophisticated statistical analysis. These approaches have enabled a shift from descriptive studies to a more nuanced understanding of landscape processes. The integration of field surveys, geospatial datasets, and participatory methods illustrates the emergence of a hybrid and operational analytical paradigm, capable of capturing the multi-dimensionality of Congolese landscapes. In parallel, classical validation methods have evolved significantly. Increasingly, researchers are turning to platforms like Google Earth Engine combined with machine learning algorithms such as Random Forest to enhance classification accuracy [

22,

41]. Moreover, validation approaches based solely on stable land cover classes [28—30] are now being refined through the adoption of best practices [

42], which emphasize the importance of considering both stable and changing land cover classes in accuracy assessment.

4. Evolving Paradigms in Landscape Ecology in the DRC

Landscape ecology has undergone significant theoretical refinement over the past four decades, evolving through three major paradigms [

43]. The foundational patch–corridor–matrix (PCM) model [

3] offered a structuralist lens to describe landscape composition and configuration. Subsequently, the pattern–process–scale (PPS) paradigm introduced a functional dimension, emphasizing spatial heterogeneity, cross-scale interactions, and process-oriented modelling [

4,

5]. Most recently, the pattern–process–service–sustainability (PPSS) framework has emerged, embedding landscape ecology within the broader epistemological project of sustainability science by linking ecological patterns to ecosystem service provision and long-term socio-environmental resilience [

44].

In the DRC, the empirical application of these paradigms reveals both convergence with and divergence from global trajectories. Between 2008 and 2015, research predominantly aligned with the PCM paradigm, focusing on quantifying landscape structure and deforestation dynamics, particularly in mining regions [

23] and peri-urban areas [

12,

13]. While these studies advanced spatial characterization, they were limited in capturing the functional ecological implications of such transformations.

From 2015 to 2020, methodological innovation—particularly in remote sensing and spatial statistics—enabled a gradual shift toward PPS-aligned approaches. However, this evolution remained incomplete, constrained by uneven territorial coverage, limited integration of socio-cultural drivers, and a lack of longitudinal datasets. Emerging studies (2020–2025) show tentative engagement with the PPSS paradigm, particularly in analyses of green infrastructure, urban ecology, and restoration planning [

20,

28,

33,

45]. Yet, conceptual integration remains fragile, revealing a critical gap between theoretical models and the socio-ecological realities of Central Africa [

8].

The application of landscape ecology paradigms in the DRC reveals foundational mismatches between global models and local empirical realities. First, the PPSS framework presupposes the existence of functional governance structures capable of translating ecological knowledge into sustainable land management [

44]. In the Congolese context, characterized by chronic institutional fragility and the prevalence of informal land-use systems—particularly in mining zones, logging frontiers, and post-conflict territories—this assumption often collapses [

22]. An alternative conceptual pathway is required, one that centers "resilience through local self-organization", accounting for customary land tenure, informal resource governance, and community-led adaptive strategies [

46].

Second, standard fragmentation metrics (e.g., those derived from FRAGSTATS) tend to underestimate the ecological significance of sub-hectare disturbances resulting from shifting cultivation, artisanal mining, and small-scale selective logging [

47]. These high-frequency, low-intensity processes are temporally dynamic and spatially heterogeneous, escaping detection by conventional spatial algorithms [

48]. We propose the development of "dynamic fragmentation indices", capable of integrating temporal variability and fine-grained disturbances into landscape-level analyses.

Third, the DRC offers a unique comparative vantage point. Unlike post-deforestation zones in the Amazon [

49] or conflict-affected landscapes in Colombia [

50] or Angola [

51], Congolese ecosystems exhibit hyper-fragmentation driven by the intersection of extractive pressures, anarchic urban expansion, and intermittent conflict [

9,

21,

26]. These configurations constitute a natural laboratory for examining ecological tipping points, spontaneous reforestation processes during conflict-induced land abandonment, and complex feedback loops between socio-political instability and landscape dynamics [

9,

10,

52,

53].

Collectively, these divergences call for a re-examination of foundational assumptions in landscape ecological theory. Congolese landscapes—marked by extreme fragmentation, institutional voids, and the simultaneous presence of global extractive economies and traditional agroforestry systems—present complex configurations that challenge dominant models of socio-ecological resilience. Addressing these challenges necessitates both theoretical flexibility and methodological innovation, in order to articulate a landscape science that is firmly rooted in the empirical pluralism and contextual realities of the Global South. Applying Kevin Lynch’s theoretical framework [

18] or the evolutionary model of landscape anthropization [

41] to southern Katanga provides a meaningful illustration and constitutes a promising entry point for advancing landscape ecological research.

5. Classification of Studies According to the Ten Principal Topics in Landscape Ecology

The ten priority research topics identified in landscape ecology encapsulate the core challenges and emerging opportunities within this interdisciplinary field [

54]. These topics not only reflect the evolving scientific questions but also the practical needs for sustainable landscape management. Among these key subjects, we distinguish the following:

a. Ecological Flows in Landscape Mosaics

Ecological flows—movements of organisms, genes, and resources—are strongly influenced by spatial heterogeneity and connectivity in landscape mosaics. Studies in the Masako and Yoko forest reserves in the DRC reveal how fragmentation and edge effects shape these dynamics.

Ref. [

55] found that rodent communities in Masako showed high similarity (83%) between fallows and secondary forests, with subadult-dominated demographics, indicating structural homogenization but ecological instability. Yet, overall habitat connectivity remains low. Ref. [

56] report only 3.9% inter-habitat mobility among rodents, with species like Deomys ferrugineus and Praomys cf. jacksoni displaying strong habitat specialization. In Yoko Reserve, Ref. [

57] observed amphibian richness highest in primary forests, with transitional zones supporting edge specialists—demonstrating how edges modulate biodiversity flows. Iyongo et al. [

58] linked edge proximity to skewed rodent sex ratios, indicating demographic sensitivity to landscape structure. These findings highlight edge effects and habitat isolation as key regulators of ecological flows in fragmented tropical systems. Maintaining functional connectivity and mitigating edge-driven pressures are essential for sustaining biodiversity and ecosystem resilience [

59].

b. Causes, Processes, and Consequences of Land Use and Land Cover Change

Land use and land cover change (LULCC) is a dominant force shaping landscape patterns and ecological processes in the DRC, generally supported by the application of the decision tree algorithm of Ref. [

60]. Studies across diverse ecosystems reveal that anthropogenic pressures—especially agricultural expansion, urbanization, and mining—drive profound transformations in land cover, often with cascading ecological consequences. In Miombo woodlands near Lubumbashi, deforestation from charcoal production and farming led to a 50% loss of cover between 1990–2022, at an annual rate of 1.51% [

41]. Similar patterns emerge in the Ituri-Epulu-Aru landscape, where deforestation accelerated from 0.05% to 0.14% (2003–2016) [

61], and in the Katangese Copperbelt Area, where post-2002 mining catalyzed widespread forest attrition [

62,

63,

64]. Consequences include declines in soil organic carbon (e.g., −26% following termite mound levelling) and biodiversity [

65], along with increased fragmentation and habitat isolation [

22], as well as fire sensibility [

66].

Urban sprawl compounds these effects. Lubumbashi’s urban growth (8.7% annually, 1989–2014) significantly reduced per capita green space [

29], while Kisangani lost 47% of mature forests between 1986–2021 due to peri-urban agriculture [

20,

67]. Diffusion-coalescence patterns typify these spatial changes, with dense urban cores and fragmented fringes [

67]. Methodologies combining Landsat imagery, landscape metrics (e.g., FRAGSTATS), and transition matrices reveal the scale and structure of LULCC. Yet, coarse resolution data and weak socio-economic integration limit causal inference. Emerging approaches—high-resolution imagery, predictive modelling (e.g., DINAMICA EGO), and stakeholder-inclusive frameworks—offer more robust insights. Projected scenarios suggest that with sustainable governance, 81.4% of forests in Ituri-Epulu-Aru could be conserved by 2061 [

60].

c. Nonlinear Dynamics and Landscape Complexity

Tropical landscapes in the DRC exhibit complex, nonlinear behaviors influenced by ecological thresholds, feedback loops, and spatial heterogeneity. These dynamics are key to understanding resilience, degradation, and the responses of ecosystems to anthropogenic pressures. In Yoko Forest Reserve, spatial aggregation of tree species (Gilbertiodendron dewevrei, Uapaca guineensis) reveals small-scale dispersal limitations that generate broader biodiversity patterns [

68]. This points to the presence of scale-dependent processes, though further integration of abiotic data is needed to identify critical thresholds in forest composition shifts. The Virunga landscape illustrates nonlinear land-cover trajectories, where protected zones remain stable while surrounding areas fluctuate due to socio-political factors. Periods of deforestation followed by unexpected regrowth during conflict highlight feedbacks linking human activity and ecosystem transitions [

10].

In the Lubumbashi charcoal basin, fire regimes are closely tied to human land use. Fires follow nonlinear spatial patterns, influenced by proximity to infrastructure and land cover type, with savannas more prone to burning. These dynamics underscore fire-vegetation feedbacks critical for anticipating future landscape change [

65]. Lomami National Park’s core forests show resilience, despite peripheral fragmentation driven by edge effects. High forest cover (92.75%) masks gradual connectivity loss, illustrating the need for multi-scale conservation metrics and high-resolution monitoring [

7]. Urban Lubumbashi demonstrates ecological tipping points, where green space fragmentation and exotic species invasion (e.g., Tithonia diversifolia) transform peri-urban biodiversity [

69]. Collectively, these cases emphasize the value of nonlinear frameworks for predicting abrupt ecological shifts. Moving from descriptive to predictive science is vital for managing tropical landscapes amid escalating human and climatic pressures [

70].

d. Scaling

Scaling is central to understanding how localized ecological processes and disturbances propagate across broader spatial and temporal dimensions. In the DRC, forest edge degradation—often confined to 100–300 m zones—accounts for 25% of regional carbon emissions, a footprint triple that of deforestation [

71]. This illustrates how fine-scale changes cascade into large-scale impacts, necessitating integration of high-resolution data (e.g., LiDAR) with landscape-scale models to capture degradation’s true scope.

Transboundary protected areas in Central Africa reveal spatial scaling mismatches in conservation. While some regions resist deforestation, others succumb to localized agricultural pressures, reflecting a disconnect between top-down governance and nested ecological threats [

72]. This mismatch highlights the need for multilevel governance structures that adapt protection strategies to both micro-scale land use and macro-scale connectivity dynamics. In Lualaba Province, 34 years of Miombo woodland degradation show how temporal scaling compounds minor fragmentation into biome-level collapse. Deforestation driven by agriculture and mining reflects a temporal lag in policy response and enforcement. Metrics like edge density and patch isolation reveal how local anthropogenic pressures scale into irreversible transformations [

73].

Ecological processes such as biodiversity dynamics also defy linear extrapolation. In Katanga, tree density and understory diversity vary across patches, corridors, and watersheds, exposing the scale-dependence of hypotheses like intermediate disturbance [

38]. This underscores the danger of applying local findings universally without scale-sensitive validation. Ultimately, scaling is both an analytical framework and a governance imperative [

74]. Bridging spatial and temporal scales using remote sensing, hierarchical models, and socio-economic integration is essential to pre-empt ecosystem tipping points and foster resilient, context-responsive landscape management [

75].

E. Methodological Development

Landscape ecology in the DRC has benefited from significant methodological advancements, enabling a more refined understanding of the complex interactions between landscape patterns and ecological processes. The advanced integration of remote sensing techniques, combining satellite imagery (Landsat, MODIS) with rigorous field validation, has improved the accuracy of monitoring forest and urban dynamics [

76]. For instance, the study by Khoji et al. [

15] in Salonga National Park quantified a 10.8% deforestation rate between 2002 and 2020, highlighting the importance of radiometric corrections and the potential of LiDAR technology to enhance spatial resolution. Concurrently, analyses of urban heat islands in Kisangani by Ref. [

33] underscored the critical role of spatial resolution in detecting thermal gradients.

Participatory approaches, such as the "Distance to Nature" method adapted by André et al. [

77] in Lubumbashi, have revitalized the mapping of anthropization levels by combining field data with proximity-based rules. Bioindicator studies have been advanced through standardized protocols; Musubaho et al. [

78] developed a rigorous nocturnal amphibian trapping method in the Yoko Reserve, enabling fine-scale quantification of diversity and endemism. Some studies stand out for their analysis of anthropogenic pressures, integrating landscape metrics with urban perception surveys. For example, Vranken et al. [

18] identified a mining-related “pollution cone” in Lubumbashi. Despite these advances, limitations in spatial resolution (e.g., Landsat at 30 m, MODIS at 1 km) and sampling biases remain significant challenges. Furthermore, the sometimes rigid dichotomy between qualitative and quantitative methods highlights the ongoing need for integrative approaches to achieve a more comprehensive landscape ecology [

79].

f. Relating Landscape Metrics to Ecological Processes

The relationship between landscape patterns and ecological processes is profoundly shaped by anthropogenic activities such as agriculture, mining, and urbanization [

60]. Land-use changes and fragmentation significantly impact biodiversity, soil quality, and carbon cycling. For instance, in the Luki Biosphere Reserve, fire disturbances account for 34% of land-cover changes, with primary forests exhibiting low stability (23–34%) compared to more resilient savannas (>73%) [

80]. Similarly, studies in the Masako Forest Reserve reveal that primary and secondary forests share 53% species similarity, while young fallows differ markedly, illustrating an “inverse J” pattern of disturbed stands [

81]. These findings underscore the importance of landscape configuration, including patch size and connectivity, for ecological resilience [

82,

83,

84].

Anthropogenic pressures also degrade soil properties. In Yangambi, Ferralsols under shifting cultivation show reduced clay content, increased bulk density, and decreased hydraulic conductivity, with edge effects extending up to 70 m into forests [

85]. Mining in Lubumbashi produces spatial pollution patterns identifiable as “pollution cones” through high-resolution imagery [

26], influenced by metrics like edge density and patch isolation.

Urban expansion alters habitat heterogeneity and species composition. Acacia auriculiformis plantations in Lubumbashi grew 30% from 2006 to 2021, with exotics comprising 51% of urban flora [

39]. Domestic gardens in planned areas show higher floristic richness, with anthropochory accounting for over 85% of seed dispersal, highlighting the link between landscape diversity and urban ecosystem services [

40].

Despite advances in remote sensing (Landsat, MODIS), spatial resolution and data gaps limit detection of fine-scale changes [

76,

86]. Future work must integrate higher-resolution tools, socio-economic data, and cross-scale models to clarify the mechanisms linking landscape patterns and ecological processes. These studies emphasize the tight coupling of human-driven landscape change and ecological outcomes in the DRC, guiding sustainable land management [

87].

g. Integrating Humans and Their Activities into Landscape Ecology

The relationship between landscape patterns and ecological processes represents a major concern in landscape ecology, particularly regarding the impact of land use on ecological dynamics. Studies conducted in the Katanga region of the DRC clearly illustrate how human activities alter landscapes and influence vegetation [

35,

88], biodiversity [

69], and ecosystem resilience [

34,

73].

Rapid urbanization in Lubumbashi and its surroundings has profoundly transformed landscape structures. Useni et al. [

30] report a 32% increase in built-up areas between 2000 and 2008, accompanied by a concomitant 33% loss of forests and wetlands, exacerbating habitat fragmentation and disturbance. The expansion of the invasive species Tithonia diversifolia exemplifies the effects of anthropogenic disturbances on ecosystems. Useni et al. [

34] also document forest loss of up to 80% in mining towns, where urban and agricultural activities predominate.

The links between land use history and ecological processes are evident. For example, Mujinya et al. [

88] demonstrate that the distribution of termite mounds in degraded Miombo woodlands is more strongly correlated with anthropogenic pressures than with pedological characteristics. During the COVID-19 pandemic, deforestation in the Lubumbashi charcoal production basin temporarily slowed during lockdowns but accelerated thereafter [

89], revealing the direct dependency of forest dynamics on human activity.

Finally, the resilience of Miombo forests is challenged by the proliferation of exotic species and floristic degradation, complicating restoration efforts [

39]. These findings underscore the urgent need for sustainable management approaches that integrate the interactions between human land use and ecological processes [

90].

h. Optimization of Landscape Pattern

The relationship between landscape pattern and ecological processes, particularly regarding deforestation dynamics, has garnered significant attention in landscape ecology. Recent studies demonstrate that the spatial configuration of protected areas critically influences deforestation risk. Strict protection zones, such as national parks, with large contiguous patches, significantly reduce deforestation [

7,

16], while less regulated areas, including hunting reserves, exhibit increased fragmentation [

14,

15,

52]. Using Random Forest models, edge density and patch connectivity emerged as key predictors of deforestation, with agricultural encroachment generating irregular patch shapes and diminishing core forest areas. These findings underscore the necessity of optimized landscape planning that prioritizes contiguous protected area networks to maintain ecosystem functionality and resilience.

In Lomami National Park, high forest aggregation (92.75% cover) within core zones contrasts with fragmentation at the periphery caused by edge effects and human activities. Landscape metrics such as patch density and edge contrast reveal destabilizing influences on forest connectivity, supporting the hypothesis that intact forest patches enhance ecosystem resilience, whereas fragmentation escalates degradation risks [

7]. Buffer zone management and corridor restoration are recommended strategies to mitigate peripheral fragmentation, with future research encouraged to incorporate high-resolution spatial monitoring for improved planning [

91].

Urbanization-driven landscape fragmentation is pronounced in Lubumbashi, where green spaces are increasingly fragmented into smaller, isolated patches [

28], and invasive species dominate peri-urban areas [

92,

93]. Patch size distribution and edge density metrics indicate declining connectivity of native vegetation due to unplanned expansion [

29]. These results advocate for restoring green infrastructure using native species and strategic patch aggregation, with landscape metrics guiding urban planning to balance development and ecological preservation. Multi-scale interventions are vital for optimizing urban landscape patterns and sustaining ecosystem services [

94].

i. Landscape Sustainability

Landscape sustainability science explores how spatial patterns interact with ecological processes to sustain ecosystem functions amid anthropogenic pressures [

4]. In Lubumbashi, recent research sheds light on land-use change, vegetation dynamics, and biodiversity responses, offering insights for sustainable landscape management [

38,

39]. The expansion of Acacia auriculiformis plantations across the urban–periurban gradient exemplifies a restoration-invasion trade-off. From 2006 to 2021, urban plantation coverage increased by 30%, accompanied by higher floristic diversity in urban zones. However, exotic species constitute 51% of the flora, half of which are invasive, posing long-term risks to native ecosystems. These findings highlight the need for afforestation practices favouring native species to prevent biodiversity loss [

39].

Miombo woodland regeneration is strongly affected by land-use history. Undisturbed and degraded miombo forests retain greater ecological resilience compared to post-cultural fallows, suggesting that degraded landscapes retain restoration potential and should be prioritized rather than abandoned [

38]. Although floristic and dendrometric indicators partially predict vegetation responses, the underlying mechanisms driving species invasion and native community reassembly remain unclear. Addressing these knowledge gaps through cross-scale, integrative research is critical to understanding how landscape configuration shapes restoration trajectories and informs adaptive management for sustainable urban landscapes.

j. Data Acquisition and Accuracy Assessment

Understanding the complex interactions between landscape patterns and ecological processes in Central African ecosystems demands robust data acquisition and rigorous accuracy assessment. Recent studies emphasize the critical role of spatial data quality and methodological rigor in evaluating land-use change impacts on soil and vegetation [

95,

96].

A major challenge lies in accurately detecting ecologically significant features such as termite mounds in Miombo woodlands. These mounds strongly influence soil nutrient distribution and hydrological functioning but exhibit complex spatial arrangements—clustered in savannas and dispersed in woodlands [

64]. Vranken et al. [

95] highlight that high-resolution remote sensing is essential for reliable mapping, as standard satellite imagery, especially in dry seasons, risks false positives due to low spectral contrast. Ground-truth validation remains indispensable for refining classification accuracy.

In urban landscapes like Lubumbashi, long-term land-use monitoring relies on time-series satellite data. Seasonal NDVI analyses reveal combined climatic and anthropogenic effects, yet their accuracy hinges on temporal resolution and correction of urban spectral noise [

96,

97]. Integrating field surveys and socio-economic data enhances the robustness of vegetation and green infrastructure assessments, addressing spatial uncertainties linked to fragmentation.

At Salonga National Park, deforestation analyses couple accessibility modelling with remote sensing to delineate forest degradation gradients linked to proximity to infrastructure. Fine-scale fragmentation detection and edge effect assessment require high spatial-temporal resolution data and rigorous validation through ecological field sampling to confirm remote sensing interpretations [

16].

6. Challenges Limiting Landscape Ecology Research

Landscape ecology research in the DRC currently faces several significant challenges that constrain its scientific scope and operational impact. These technical, methodological, and conceptual limitations affect the quality of analyses and the ability to produce relevant results for sustainable territorial management.

From a technical perspective, spatial resolution of data remains a recurrent obstacle. While satellite imagery such as Landsat or MODIS provides broad coverage, its resolution is insufficient to capture fine-scale dynamics of Congolese ecosystems, particularly in highly fragmented areas such as the urban peripheries of Lubumbashi or mining sites in Katanga [

41]. Moreover, persistent cloud cover in tropical regions restricts access to usable images and hampers the temporal continuity of observational series [

16]. This limitation directly impacts the accuracy of mapping and monitoring of landscape changes [

98].

A major limitation in vegetation mapping remains the lack of systematic field validation. Numerous studies rely predominantly on satellite-derived data, often without sufficient ground-truthing, which contributes to classification inaccuracies and hampers the precise differentiation of vegetation types and levels of ecological degradation [

99]. Additionally, floristic and faunistic inventories are frequently conducted in a sporadic and heterogeneous manner, limiting their utility for robust spatial and temporal analyses. Recent findings by Ramalason et al. [

100] further demonstrate that global vegetation maps inadequately represent dryland ecosystems; however, integrating tree and shrub cover into a unified woody cover metric significantly enhances mapping accuracy, underscoring the need for improved remote sensing strategies tailored to specific landscapes.

Methodologically, the absence of standardized protocols hinders the coherence of results across different studies. Land-use classifications vary, as do the landscape metrics employed, limiting the synthesis of knowledge at the national scale (i.e. [

36,

61]). Furthermore, most research focuses on relatively short timeframes (ten to twenty years), which are insufficient to capture long-term dynamics typical of tropical ecosystems that require robust and often unavailable historical datasets [

11].

Conceptually, landscape ecology research in the DRC tends to emphasize biophysical factors while underrepresenting socio-economic and cultural dimensions that are crucial for understanding territorial dynamics [

101]. Human drivers such as agricultural practices, land tenure issues, and local governance systems are often inadequately integrated, reducing the explanatory power of ecological models [

41]. Additionally, the challenge of linking spatial and temporal scales—from local to global—prevents a systemic understanding of complex interactions between human activities and ecological processes [

52].

Finally, practical applications of research findings remain limited. The weak dialogue between scientists, policymakers, and local communities hinders the translation of knowledge into effective conservation policies and sustainable land-use planning. Consequently, research struggles to become a strategic lever for managing Congolese landscapes [

102].

7. Perspectives for Integrated and Sustainable Landscape Ecology

Landscape ecology in the DRC must evolve from broad perspectives to innovative, operational frameworks that directly address the region’s unique socio-environmental complexities. We propose three strategic priorities to accelerate this transition:

a. Development of a Human-Ecological Fragmentation Index (HFEI)

Traditional fragmentation metrics primarily quantify structural changes in land cover but fail to fully capture the intricate socio-political drivers of landscape transformation in the DRC, such as artisanal mining, informal settlements [

41], and fluctuating governance [

9]. The HFEI would integrate multi-source remote sensing data—combining high-resolution satellite imagery, Lidar, and drone-derived data—with socio-political indicators (e.g., mining concessions, population migration patterns). This index would enable quantification of fragmentation across both ecological and human dimensions, incorporating temporal dynamics to reflect episodic disturbances and gradual changes [

103]. Such a tool would fill a critical gap in current methodologies and improve landscape monitoring and management precision.

b. Experimentation with Hybrid Governance Models

In contexts marked by governance fragility and informal socio-political structures, like the DRC, conventional top-down conservation and land management approaches often fail. Innovative governance frameworks co-designed with local communities, scientists, and policy actors can facilitate adaptive management of landscapes [

101] and protected areas [

7]. These hybrid models would recognize and formalize the role of informal actors (e.g., artisanal miners, traditional agroforestry practitioners) as legitimate stakeholders, fostering resilience through local self-organization, knowledge exchange, and shared stewardship [

104]. Pilot projects testing these governance hybrids could provide replicable models for other fragile states.

8. Toward a Contextualized Conceptual Framework for Landscape Ecology in the DRC

Despite two decades of empirical research in the DRC, most landscape ecological studies continue to mobilize imported theoretical models without proposing frameworks that fully account for the country’s unique socio-ecological configurations. However, the DRC presents a rare convergence of interacting drivers—armed conflict, extractive expansion, institutional vacuums, and traditional ecological knowledge—that collectively reshape landscape structure, function, and governance. This calls for the development of a situated conceptual model, capable of capturing these multiscalar dynamics and informing both research and policy.

We propose a framework tentatively titled “Socio-political fragmentation model: when informal governance redefines ecological connectivity.” This model integrates three core dimensions:

- -

Feedback loops between extractive pressures and demographic shifts, e.g., industrial and artisanal mining triggering rural exodus and peri-urban settlement, which in turn increases pressure on secondary forests and agroforestry mosaics [

34].

- -

Non-linear temporal regimes, driven by the recurrence of political crises, economic shocks, and post-conflict reconfigurations. These cycles create pulsed disturbances (e.g., spontaneous reforestation during conflict, abrupt deforestation during reconstruction) that challenge linear degradation models and classical successional assumptions [

9,

52].

- -

The centrality of informal actors and governance regimes—including artisanal miners (creuseurs), customary chiefs, local conservation networks, and informal markets—which mediate land-use decisions and ecological outcomes outside formal institutions [

22,

101].

This conceptualization diverges from dominant landscape ecology paradigms by rejecting assumptions of institutional stability, data continuity, and static land-use drivers. Instead, it emphasizes adaptive socio-ecological assemblages, territorial fluidity, and fragmentation as both spatial and political. By formalizing this framework, we aim to stimulate comparative research across crisis-affected geographies (e.g., post-conflict Colombia, resource frontiers in the Amazon) and contribute to a globally relevant but locally grounded theory of landscape dynamics under institutional fragility.

9. Broader Implications for Global Landscape Ecology and Sustainability Science

The Congolese case, while context-specific, offers broader theoretical and operational insights with significant implications for global landscape ecology and conservation science. Most notably, the extreme socio-political volatility and institutional fragility observed in the DRC challenge the implicit assumption of governance stability underlying many resilience frameworks. The ecological behavior of Congolese landscapes suggests that resilience theories must systematically integrate political instability and institutional discontinuity as key structuring variables—a perspective highly relevant to other fragile states such as Madagascar, South Sudan, or Haiti.

Furthermore, the failure of top-down conservation models in the DRC, particularly in regions where protected areas coexist with active mining concessions or artisanal extraction zones [

14,

16], raises critical concerns regarding the applicability of global conservation targets such as the “30x30” agenda. Our findings emphasize the need to re-express spatial targets in terms of functional ecological connectivity, social legitimacy, and multi-actor governance, rather than relying solely on cartographic coverage and legal designation.

From a policy perspective, this study calls for a more nuanced articulation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). While SDG 15 (“Life on Land”) remains central to biodiversity protection, our results demonstrate the need to couple it systematically with SDG 16 (“Peace, Justice, and Strong Institutions”). Environmental sustainability cannot be decoupled from conflict dynamics, informal governance, and socio-political fragmentation in contexts like the DRC.

Finally, we argue for the development of new sustainability indicators that reflect not only ecological metrics but also conflict intensity, governance quality, and the resilience of local knowledge systems. These composite indicators could better guide international funding, conservation planning, and post-crisis reconstruction in ecologically critical but politically unstable regions.

10. Conclusion

The retrospective assessment of landscape ecology research in the DRC over the past two decades highlights a discipline undergoing significant maturation, marked by a paradigmatic shift from descriptive studies to disruptive theoretical innovation. Initially delayed compared to other contexts, research in the DRC has progressively integrated spatial analysis, ecological theory, and social science, evolving towards a transdisciplinary framework tailored to its unique socio-ecological challenges.

The DRC’s landscapes, characterized by extreme fragmentation driven by mining, armed conflict, and unregulated urban expansion, serve as a natural laboratory for re-examining established global paradigms such as the Press-Pulse Disturbance and conventional fragmentation metrics. These frameworks, which assume functional governance and linear degradation trajectories, fail to capture the complex realities of the Congo Basin, where non-linear feedbacks like spontaneous post-conflict reforestation and informal governance structures redefine ecological connectivity and resilience.

This context has necessitated the development of novel conceptual tools, including the HFEI and models that explicitly incorporate socio-political fragmentation and informal actors. Such advances challenge the universality of global landscape ecology theories and underscore the need for models that integrate governance fragility and socio-political instability as central variables.

Comparative insights drawn from other crisis-affected regions (e.g., post-deforestation Amazonia, conflict zones in Colombia) suggest these lessons have broad relevance for rethinking sustainability and resilience in fragile states worldwide. Consequently, future research must prioritize integrating conflict dynamics (aligning with SDG 16) alongside biodiversity goals (SDG 15), and foster hybrid governance approaches that engage local communities alongside scientific institutions.

Landscape ecology in the DRC is not merely adapting global concepts but actively reconfiguring theoretical foundations, offering a critical vantage point for global sustainability science. Recognizing and amplifying this disruptive potential will enhance both the discipline’s scientific rigor and its practical impact in managing landscapes under crisis conditions.

Author Contributions

Y.U.S.: conceptualisation, methodology, writing—original draft preparation, data curation; J.B : supervision, writing—review and funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

The study was supported by the development research project “Capacity building for the sustainable management of the miombo woodland through the assessment of the environmental impact of charcoal production and the improvement of forest resource management practices (CHARLU, ARES-CCD COOP-CONV-21-519, Belgium).

Data Availability Statement

The authors confirm that all data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the development research project "Capacity building for the sustainable management of the miombo clear forest through the assessment of the environmental impact of charcoal production and the improvement of forest resource management practices (CHARLU)".

Conflicts of Interest

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. All co-authors have reviewed and approved the contents of the manuscript, and there are no financial interests to report. We confirm that the submission represents original work and is not currently under review by any other publication.

References

- Fu, B. J.; Lu, Y. H. The progress and perspectives of landscape ecology in China. Progress in Physical Geography 2006, 30, 2–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, J., André, M., Eds.; Ecologie du paysage en Afrique subsaharienne. Tropicultura 2013, 31, 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Forman, RTT; Godron M. Landscape ecology. Wiley, New York, 1986.

- Wu, J. Key concepts and research topics in landscape ecology revisited: 30 years after the Allerton Park workshop. Landscape ecology 2013, 28, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, M. G. Landscape ecology: what is the state of the science? Annu. Rev. Ecol. Evol. Syst. 2005, 36, 319–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, J.; Vranken, I.; André, M. Anthropogenic effects in landscapes: Historical context and spatial pattern. In Biocultural landscapes. Diversity, Functions and Values; Hong, S.K., Bogaert, J., Min, Q., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2014; pp. 89–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mukaku, G.K.; Mpanda Mukenza, M.; Kikuni Tchowa, J.; Malaisse, F.; Kabongo Kabeya, C.; Pitchou Meniko To Hulu, J.-P.; Bogaert, J.; Useni Sikuzani, Y. Assessment of Spatial Dynamics of Forest Cover in Lomami National Park (DR Congo), 2008–2024: Implications for Conservation and Sustainable Ecosystem Management. Ecologies 2025, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, J.; Bamba, I.; Koffi, K.J.; Sibomana, S.; Djibu, K.J.P.; Champluvier, D.; Robbreght, E.; De Cannière, C.; Visser, M.N. Fragmentation of forest landscapes in Central Africa: Causes, consequences and managment. In Patterns and Process in Landscape; Lafortezza, R., Chen, J., Sanesi, G., Crow, T.R., Eds.; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 2008; pp. 67–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumbere, C.M.; Sambieni, K.R.; Mweru, J.-P.M.; Bastin, J.-F.; Ndukura, C.S.; Nguba, T.B.; Balandi, J.B.; Bogaert, J. Land Cover Dynamics in the Northwestern Virunga Landscape: An Analysis of the Past Two Decades in a Dynamic Economic and Security Context. Land 2024, 13, 566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mumbere, C.M.; Essouman, P.F.E.; Ndjadi, S.S.; Balandi, J.B.; Nguba, T.B.; Sodalo, C.; Mweru, J.-P.M.; Sambieni, K.R.; Bogaert, J. Anthropogenic Disturbances in Northwestern Virunga Forest Amid Armed Conflict. Land 2025, 14, 732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoji, H.M.; N’tambwe Nghonda, D. D.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J.; Useni Sikuzani, Y. Mapping and quantifying deforestation in the Zambezi ecoregion of Central-Southern Africa: extent and spatial structure. Frontiers in Remote Sensing 2025, 6, 1590591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamba, I.; Barima, Y. S. S.; Bogaert, J. Influence de la densité de la population sur la structure spatiale d’un paysage forestier dans le Bassin du Congo en R. D. Congo. Tropical Conservation Science 2010, 3, 43–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamba, I.; Yedmel, M. S.; Bogaert, J. Effets des routes et des villes sur la forêt dense dans la province orientale de la République Démocratique du Congo. European Journal of Scientific Research 2010, 43, 417–429. [Google Scholar]

- Useni, Y. S.; Muteya, H. K.; Bogaert, J. . Miombo woodland, an ecosystem at risk of disappearance in the Lufira Biosphere Reserve (Upper Katanga, DR Congo)? A 39-years analysis based on Landsat images. Global Ecology and Conservation 2020, 24, e01333. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoji, H. M.; Mokuba, H. K.; Sambieni, K. R.; Sikuzani, Y. U.; Moyene, A. B.; Bogaert, J. Évaluation de la dynamique spatiale des forêts primaires au sein du Parc national de la Salonga sud (RD Congo) à partir des images satellites Landsat et des données relevées in situ. VertigO 2024, 24, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoji, H. M.; Mukenza, M. M.; Mwenya, I. K.; Malaisse, F.; Nghonda, D. D. N.; Mukendi, N. K.; Bastin, J.-F.; Bogaert, J.; Sikuzani, Y. U. Protected area creation and its limited effect on deforestation: Insights from the Kiziba-Baluba hunting domain (DR Congo). Trees, Forests and People 2024, 18, 100654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, Y. S.; Kipili, I. M.; Mukenza, M. M.; N’Tambwe, D. N.; Cizungu, N. C.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. Thirty-three years of land cover change analysis on Idjwi Island (DRC) using remote sensing and landscape metrics. Landscape Research 2025, 50, 4, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranken, I.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F.; Amisi Mwana, Y.; Bamba, I.; Veroustraete, F.; Visser, M.; Bogaert, J. The spatial footprint of the non-ferrous metal industry in Lubumbashi. Tropicultura 2013, 31, 20–27. [Google Scholar]

- Useni, Y. S.; Boisson, S.; Cabala, S. K.; Nkuku, C. K.; Malaisse, F.; Halleux, J-M.; Bogaert, J.; Munyemba, F. K. Dynamique de l’occupation du sol autour des sites miniers le long du gradient urbain-rural de la ville de Lubumbashi, RD Congo. Biotechnologies, Agronomie, Société et Environnement. 2020, 24, 14–27. Available online: https://popups.uliege.be/1780-4507/index.php?id=18306.

- Bwazani, J.B.; To Hulu, J.-P.P.M.; Sambieni, K.R.; Sikuzani, Y.U.; Bastin, J.-F.; Musavandalo, C.M.; Nguba, T.B.; Jesuka, R.; Sodalo, C.; Pika, L.M.; et al. Anthropogenic Effects on Green Infrastructure Spatial Patterns in Kisangani City and Its Urban–Rural Gradient. Land 2024, 13, 1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mwitwa, J.; German, L.; Muimba-Kankolongo, A.; Puntodewo, A. Governance and sustainability challenges in landscapes shaped by mining: Mining-forestry linkages and impacts in the Copper Belt of Zambia and the DR Congo. Forest policy and economics 2012, 25, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mpanda, M.M.; Muteya, H.K.; Nghonda, D.-D.N.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Malaisse, F.; Kaleba, S.C.; Bogaert, J.; Sikuzani, Y.U. Uncontrolled Exploitation of Pterocarpus tinctorius Welw. and Associated Landscape Dynamics in the Kasenga Territory: Case of the Rural Area of Kasomeno (DR Congo). Land 2022, 11, 1541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kabulu, J.P.D.; Bamba, I.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F.; Defourny, P.; Vancutsem, C.; Nyembwe, N. S.; Ngongo, M. L.; Bogaert, J. Analyse de la structure spatiale des forêts au Katanga. Annales de la Faculté des Sciences Agronomiques de l'Université de Lubumbashi 2008, 1, 12–18. [Google Scholar]

- Bastin, J.-F.; Djibu, J. P.; Havyarimana, F.; Alongo, S.; Kumba, S.; Shalukoma, C.; Motondo, A.; Joiris, V.; Stévigny, C.; Duez, P.; De Cannière, C.; Bogaert, J. Multiscalar analysis of the spatial pattern of forest ecosystems in Central Africa justified by the pattern/process paradigm: two case studies. In Forestry: research, ecology and policies; Boehm, D.A., Ed.; Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, USA, 2011; pp. 79–98. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2268/107891.

- Vranken, I.; Djibu Kabulu, J.P.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F.; Mama, A.; Iyongo Waya Mongo, L.; Bamba, B.; Laghmouch, M.; Bogaert, J. Ecological impact of habitat loss on African landscapes and diversity. Advances in environmental research 2011, 14, 365–388. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2268/107896.

- Munyemba, F.; Bamba, I.; Kabulu, J.P.; Amisi, M. Y.; Veroustraete, F.; Ngongo, M.; Bogaert, J. Occupation des sols dans le cône de pollution à Lubumbashi. Annales de la Faculté des Sciences Agronomiques de l’Université de Lubumbashi 2008, 1, 19–25. [Google Scholar]

- Maréchal, J.; Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Bogaert, J.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F.; Mahy, G. La perception par des experts locaux des espaces verts et de leurs services écosystémiques dans une ville tropicale en expansion : le cas de Lubumbashi. In Anthropisation des paysages katangais; J. Bogaert, G. Colinet, G. Mahy, Ed.; Presses Universitaires de Liège, 2008; pp. 59–69. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2268/227503.

- Useni, Y. S.; Kaleba, S. C.; Khonde, C. N.; Mwana, Y. A.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J.; Kankumbi, F. M. Vingt-cinq ans de monitoring de la dynamique spatiale des espaces verts en réponse á ('urbanisation dans les communes de la ville de Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, R.D. Congo). Tropicultura 2017, 35, 300–311. Available online: https://hdl.handle.net/2268/227664.

- Useni, Y.S.; Cabala Kaleba, S.; Halleux, J.-M.; Bogaert, J.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F. Caractérisation de la croissance spatiale urbaine de la ville de Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, R.D. Congo) entre 1989 et 2014. Tropicultura 2018, 36, 99–108. [Google Scholar]

- Useni, Y.S.; André, M.; Mahy, G.; Cabala Kaleba, S.; Malaisse, F.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F.; Bogaert, J. Interprétation paysagère du processus d’urbanisation à Lubumbashi (RD Congo): dynamique de la structure spatiale et suivi des indicateurs écologiques entre 2002 et 2008. In G. Mahy, G. Colinet, ... J. Bogaert, Anthropisation des paysages katangais 2018 (pp. 281-296). Gembloux, Belgium: Presses agronomiques de Gembloux. https://hdl.handle.net/2268/194483.

- Useni, Y. S.; Malaisse, F.; Kaleba, S. C.; Kankumbi, F. M.; Bogaert, J. Le rayon de déforestation autour de la ville de Lubumbashi (Haut-Katanga, R.D. Congo): Synthèse. Tropicultura 2017, 35, 215–221. [Google Scholar]

- Useni, Y.S.; Mukenza, M.M.; Malaisse, F.; Kaseya, P.K.; Bogaert, J. The Spatiotemporal Changing Dynamics of Miombo Deforestation and Illegal Human Activities for Forest Fire in Kundelungu National Park, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Fire 2023, 6, 174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bwazani, J.B.; Selemani, T.M.; To Hulu, J.-P.P.M.; Sambieni, K.R.; Sikuzani, Y.U.; Bastin, J.-F.; Wola, P.T.; Molo, J.E.; Tiko, J.M.; Agassounon, B.M.; Bogaert, J. Spatiotemporal Analysis of Urban Heat Islands in Kisangani City Using MODIS Imagery: Exploring Interactions with Urban–Rural Gradient, Building Volume Density, and Vegetation Effects. Climate 2025, 13, 89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, Y.S.; Mpanda Mukenza, M.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. Investigating of Spatial Urban Growth Pattern and Associated Landscape Dynamics in Congolese Mining Cities Bordering Zambia from 1990 to 2023. Resources 2024, 13, 107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, Y.S.; Mpanda Mukenza, M.; Kikuni Tchowa, J.; Kabamb Kanyimb, D.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. Hierarchical Analysis of Miombo Woodland Spatial Dynamics in Lualaba Province (Democratic Republic of the Congo), 1990–2024: Integrating Remote Sensing and Landscape Ecology Techniques. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bamba, I.; Mama, A.; Neuba, D. F. R.; Koffi, K. J.; Traore, D.; Visser, M.; Sinsin, B.; Lejoly, J.; Bogaert, J. Influence des actions anthropiques sur la dynamique spatio-temporelle de l’occupation du sol dans la province du Bas-Congo (R.D. Congo). Sciences et Nature 2008, 49–60. [Google Scholar]

- Useni, Y.S.; Sambieni, K. R.; Maréchal, J.; Ilunga wa Ilunga, E.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J.; Munyemba KanKumbi, F. Changes in the Spatial Pattern and Ecological Functionalities of Green Spaces in Lubumbashi (the Democratic Republic of Congo) in Relation With the Degree of Urbanization. Tropical Conservation Science 2018, 11, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’Tambwe, D.-D.N.; Muteya, H.K.; Salomon, W.; Mushagalusa, F.C.; Malaisse, F.; Ponette, Q.; Sikuzani, Y.U.; Kalenga, W.M.; Bogaert, J. Floristic Diversity and Natural Regeneration of Miombo Woodlands in the Rural Area of Lubumbashi, D.R. Congo. Diversity 2024, 16, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, Y.S.; Khoji Muteya, H.; Yona Mleci, J.; Mpanda Mukenza, M.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. The Restoration of Degraded Landscapes along the Urban–Rural Gradient of Lubumbashi City (Democratic Republic of the Congo) by Acacia auriculiformis Plantations: Their Spatial Dynamics and Impact on Plant Diversity. Ecologies 2024, 5, 25–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, Y.S.; Kisangani Kalonda, B.; Mpanda Mukenza, M.; Yona Mleci, J.; Mpibwe Kalenga, A.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. Exploring Floristic Diversity, Propagation Patterns, and Plant Functions in Domestic Gardens across Urban Planning Gradient in Lubumbashi, DR Congo. Ecologies 2024, 5, 512–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khoji, H.M.; Nghonda, D.-D.N.; Malaisse, F.; Waselin, S.; Sambiéni, K.R.; Kaleba, S.C.; Kankumbi, F.M.; Bastin, J.-F.; Bogaert, J.; Sikuzani, Y.U. Quantification and Simulation of Landscape Anthropization around the Mining Agglomerations of Southeastern Katanga (DR Congo) between 1979 and 2090. Land 2022, 11, 850. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olofsson, P.; Foody, G. M.; Herold, M.; Stehman, S. V.; Woodcock, C. E.; Wulder, M. A. Good practices for estimating area and assessing accuracy of land change. Remote sensing of Environment 2014, 148, 42–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Zhao, W.; Ding, J.; Liu, Y. Shifting research paradigms in landscape ecology: insights from bibliometric analysis. Landscape Ecology 2025, 40, 3–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, B.; Liu, Y.; Zhao, W.; Wu, J. The emerging “pattern-process-service-sustainability” paradigm in landscape ecology. Landscape Ecology 2025, 40, 3–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sambieni, K. R.; Useni, S. Y.; Cabala, K. S.; Biloso, M. A.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F.; Lelo Nzuzi, F.; Occhiuto, R.; Bogaert, J. Les espaces verts en zone urbaine et periurbaine de Kinshasa en République Démocratique du Congo. Tropicultura 2018, 36, 478–491. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Paoli, H.; Van Der Heide, T.; Van Den Berg, A.; Silliman, B. R.; Herman, P. M.; Van De Koppel, J. Behavioral self-organization underlies the resilience of a coastal ecosystem. Proceedings of the national academy of sciences 2017, 114, 8035–8040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Blanchet, F. G.; Koper, N. Measuring habitat fragmentation: An evaluation of landscape pattern metrics. Methods in ecology and evolution 2014, 5, 634–646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gebhardt, S.; van Dijk, J.; Wassen, M. J.; Bakker, M. Agricultural intensity interacts with landscape arrangement in driving ecosystem services. Agriculture, Ecosystems & Environment 2023, 357, 108692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ometto, J. P.; Aguiar, A. P. D.; Martinelli, L. A. Amazon deforestation in Brazil: effects, drivers and challenges. Carbon Management 2011, 5, 575–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del Río Duque, M. L.; Rodríguez, T.; Pérez Lora, Á. P.; Löhr, K.; Romero, M.; Castro-Nunez, A.; Sieber, S.; Bonatti, M. Understanding systemic land use dynamics in conflict-affected territories: The cases of Cesar and Caquetá, Colombia. Plos one 2022, 17, 5–e0269088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Temudo, M. P.; Cabral, A. I.; Talhinhas, P. Petro-Landscapes: Urban expansion and energy consumption in mbanza kongo city, northern Angola. Human Ecology 2019, 47, 565–575. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirezi, N.C.; Bastin, J.-F.; Mugumaarhahama, Y.; Useni, Y.S.; Karume, K.; Lumbuenamo, R.S.; Bogaert, J. Analyzing Drivers of Tropical Moist Forest Dynamics in the Kahuzi-Biega National Park Landscape, Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo from 1990 to 2022. Land 2025, 14, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Citwara, C.B.; Selemani, T.M.; Balandi, J.B.; Cirezi, N.C.; Nduwimana, A.; Kakira, L.M.; Sambieni, K.R.; Mweru, J.-P.M.; Bastin, J.-F.; Tchekote, H.; et al. The Spatiotemporal Dynamics of the Landscape of the Itombwe Nature Reserve and Its Periphery in South Kivu, the Democratic Republic of Congo. Land 2025, 14, 907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.; Hobbs, R. Key issues and research priorities in landscape ecology: an idiosyncratic synthesis. Landscape ecology 2002, 17, 355–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyongo Waya Mongo, L.; Boketshu Ilonga, M.; Bola Ntikala, J.C.; Bogaert, J. Structure de population de sept espèces de Rongeurs forestiers à Masako : influence saisonnière et effets de lisière. In Bogaert, J., Beeckman, H., De Cannière, C., Defourny, P.; Ponette, Q. (Eds.). (2020). Les forêts de la Tshopo: écologie, histoire et composition. Gembloux, Belgium: Presses Universitaires de Liège - Agronomie – Gembloux, pp 267-280.

- Meniko To Hulu, J.P.P.; Amundala Drazo, N.; Iyongo Waya Mongo, L.; Mate Mweru, J.P.; Verheyen, E.; De Gelas, K.; Dudu Akaibe, B.; Bogaert, J. Affiliation aux habitats et mobilité spécifique de Rongeurs dans un paysage fragmenté à Masako. In Bogaert, J., Beeckman, H., De Cannière, C., Defourny, P.; Ponette, Q. (Eds.). (2020). Les forêts de la Tshopo: écologie, histoire et composition. Gembloux, Belgium: Presses Universitaires de Liège - Agronomie – Gembloux, pp 31-48.

- Musubaho, L.; Iyongo, L.; Mukinzi, J.-C.; Mukiranya, A.; Mutahinga, J.; Dufrêne, M.; Bogaert, J. Anthropogenic Effects on Amphibian Diversity and Habitat Similarity in the Yoko Forest Reserve, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Diversity 2024, 16, 756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyongo Waya Mongo, L.; De Cannière, C.; Ulyel, J.; Dudu, B.; Bukasa, K.; Verheyen, E.; Bogaert, J. Effets de lisière et sex-ratio de rongeurs forestiers dans un écosystème fragmenté en République Démocratique du Congo (Réserve de Masako, Kisangani). Tropicultura 2013, 31, 3–9. [Google Scholar]

- Armenteras-Pascual, D.; Garcia-Suabita, W.; Garcia-Samaca, A. S.; Reyes-Palacios, A. Tree Functional Traits’ Responses to Forest Edges and Fire in the Savanna Landscapes of Northern South America. Forests 2025, 16, 2–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogaert, J.; Ceulemans, R.; Salvador-Van Eysenrode, D. Decision tree algorithm for detection of spatial processes in landscape transformation. Environmental Management 2004, 1, 62–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabuanga, J.M.; Kankonda, O.M.; Saqalli, M.; Maestripieri, N.; Bilintoh, T.M.; Mweru, J.-P.M.; Liama, A.B.; Nishuli, R.; Mané, L. Historical Changes and Future Trajectories of Deforestation in the Ituri-Epulu-Aru Landscape (Democratic Republic of the Congo). Land 2021, 10, 1042. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabala, S.K.; Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Sambieni, K. R.; Bogaert, J.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F. Dynamique des écosystèmes forestiers de l'Arc Cuprifère Katangais en République Démocratique du Congo. I. Causes, transformations spatiales et ampleur. Tropicultura 2017, 35, 192–202. [Google Scholar]

- Cabala, S.K.; Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Amisi Mwana, Y.; Bogaert, J.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F. Analyse structurale de la dynamique forestière dans la région de l'Arc Cuprifère Katangais en République Démocratique du Congo : II. Analyse complémentaire de la fragmentation forestière. Tropicultura 2018, 36, 621–630. [Google Scholar]

- Cabala, S.K.; Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F.; Bogaert, J. Activités anthropiques et dynamique spatiotemporelle de la forêt claire dans la Plaine de Lubumbashi. In J. Bogaert, G. Colinet, G. Mahy, Anthropisation des paysages katangais (pp. 253-266). Presses Universitaires de Liège, Belgium, 2018. https://hdl.handle.net/2268/227502.

- Ou, X.; Sebagenzi, G.D.; Mujinya, B.B.; Boeckx, P.; Döetterl, S.; Six, J.; Shi, P.; Van Oost, K. From smallholder to commercial farming: the impact of termite mound levelling and spatial heterogeneity in mound morphology on soil organic carbon in Miombo woodlands, Central Africa. Landsc Ecol 2025, 40, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, Y.S.; Mpanda Mukenza, M.; Khoji Muteya, H.; Cirezi Cizungu, N.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. Vegetation Fires in the Lubumbashi Charcoal Production Basin (The Democratic Republic of the Congo): Drivers, Extent and Spatiotemporal Dynamics. Land 2023, 12, 2171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bwazani, J.B.; To Hulu, J.P.P.M.; Sambieni, K.R.; Sikuzani, Y.U.; Bastin, J.-F.; Musavandalo, C.M.; Nguba, T.B.; Molo, J.E.L.; Selemani, T.M.; Mweru, J.-P.M.; Bogaert, J. Urban Sprawl and Changes in Landscape Patterns: The Case of Kisangani City and Its Periphery (DR Congo). Land 2023, 12, 2066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumba, S.; Nshimba, H.; Ndjele, L.; De Cannière, C.; Visser, M.; Bogaert, J. Structure spatiale des trois espèces les plus abondantes dans la Réserve Forestière de la Yoko, Ubundu, République Démocratique du Congo. Tropicultura 2013, 31, 53–61. [Google Scholar]

- Useni, Y.S.; André, M.; Mahy, G.; Cabala Kaleba, S.; Malaisse, F.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F.; Bogaert, J. Interprétation paysagère du processus d’urbanisation à Lubumbashi (RD Congo): dynamique de la structure spatiale et suivi des indicateurs écologiques entre 2002 et 2008. In G. Mahy, G. Colinet, J. Bogaert, Anthropisation des paysages katangais (pp. 281-296). Gembloux, Belgium: Presses agronomiques de Gembloux, Belgium, 2018. https://hdl.handle.net/2268/194483.

- Mouquet, N.; Lagadeuc, Y.; Devictor, V.; Doyen, L.; Duputié, A.; Eveillard, D.; Faure, D.; Garnier, E.; Gimenez, O.; Huneman, P.; Jabot, F.; Jarne, P.; Joly, D.; Julliard, R.; Kéfi, S.; Kergoat, G.J.; Lavorel, S.; Le Gall, L.; Meslin, L.; Morand, S.; Morin, X.; Morlon, H.; Pinay, G.; Pradel, R.; Schurr, F.M.; Thuiller, W.; Loreau, M. Predictive ecology in a changing world. Journal of applied ecology 2015, 5, 1293–1310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shapiro, A. C.; Aguilar-Amuchastegui, N.; Hostert, P.; Bastin, J. F. Using fragmentation to assess degradation of forest edges in Democratic Republic of Congo. Carbon balance and management 2016, 11, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bernhard, K.P.; Shapiro, A.C.; d’Annunzio, R.; Kabuanga, J.M. Transboundary Central African Protected Area Complexes Demonstrate Varied Effectiveness in Reducing Predicted Risk of Deforestation Attributed to Small-Scale Agriculture. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Mpanda Mukenza, M.; Kikuni Tchowa, J.; Kabamb Kanyimb, D.; Malaisse, F.; Bogaert, J. Hierarchical Analysis of Miombo Woodland Spatial Dynamics in Lualaba Province (Democratic Republic of the Congo), 1990–2024: Integrating Remote Sensing and Landscape Ecology Techniques. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 3903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kok, K.; Veldkamp, T. Scale and governance: conceptual considerations and practical implications. Ecology and Society 2011, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weber, A.; Fohrer, N.; Möller, D. Long-term land use changes in a mesoscale watershed due to socio-economic factors—effects on landscape structures and functions. Ecological modelling 2011, 140, 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirezi, N. C.; Tshibasu, E.; Lutete, E.; Mushagalusa, C. A.; Mugumaarhahama, Y.; Ganza, D.; Karume, K.; Michel, B.; Lumbuenamo, R. , Bogaert, J. Fire risk assessment, spatiotemporal clustering and hotspot analysis in the Luki biosphere reserve region, western DR Congo. Trees, Forests and People 2021, 5, 100104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andre, M.; Vranken, I.; Boisson, S.; Mahy, G.; Rüdisser, J.; Visser, M.; Lejeune, P.; Bogaert, J. Quantification of anthropogenic effects in the landscape of Lubumbashi. In G. Mahy, G. Colinet, J. Bogaert, Anthropisation des paysages katangais (pp. 231-251). Gembloux, Belgium: Presses Universitaires de Gembloux, 2018. https://hdl.handle.net/2268/186226.

- Musubaho, L.; Iyongo, L.; Mukinzi, J.-C.; Mukiranya, A.; Mutahinga, J.; Badjedjea, G.; Lango, L.; Bogaert, J. Diversity and Endemism of Amphibian Fauna in the Yoko Forest Reserve, Democratic Republic of the Congo. Diversity 2024, 16, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terkenli, T.S.; Gkoltsiou, A.; Kavroudakis, D. The Interplay of Objectivity and Subjectivity in Landscape Character Assessment: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches and Challenges. Land 2021, 10, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cirezi, N. C.; Bastin, J. F.; Tshibasu, E.; Lonpi, E. T.; Chuma, G. B.; Mugumaarhahama, Y. , Sambieni, K.R.; Karume, K.; Lumbuenamo, R.; Bogaert, J. Contribution of ‘human induced fires’ to forest and savanna land conversion dynamics in the Luki Biosphere Reserve landscape, western Democratic Republic of Congo. International Journal of Remote Sensing 2022, 43, 17–6406. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meniko To Hulu, J.P.P.; Tshibamba Mukendi, J.; Amundala Drazo, N., Iyongo Waya Mongo; Mate Mweru, J.P.; Ewango, C.; Verheyen, E.; Dudu Akaibe, B.; Bogaert, J. Diversité et structure démographique des populations de Rongeurs suivant un gradient d’anthropisation à Masako. In Bogaert, J., Beeckman, H., De Cannière, C., Defourny, P.; Ponette, Q. (Eds.). 2020. Les forêts de la Tshopo: écologie, histoire et composition. Gembloux, Belgium: Presses Universitaires de Liège - Agronomie – Gembloux, pp 59-73.

- Barima, Y. S. S.; Djibu, J. P.; Alongo, S.; Ndayishimiye, J.; Bomolo, O.; Kumba, S.; Iyongo, L.; Bamba, I.; Mama, A.; Toyi, M.; Kasongo, E.; Masharabu, T.; Visser, M.; Bogaert, J. Deforestation in Central and West Africa: landscape dynamics, anthropogenic effects and ecological consequences. In Daniels, J A (Ed.), Advances in Environmental Research 2011 Volume 7 (pp. 95-120). Nova Science Publishers: Hauppauge, NY, 11788 USA. https://hdl.handle.net/2268/95622.

- Cumming, G.S. Spatial resilience: integrating landscape ecology, resilience, and sustainability. Landscape ecology 2011, 26, 899–909. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- N’Tambwe, D.-D.N.; Muteya, H.K.; Moyene, A.B.; Malaisse, F.; Sikuzani, Y.U.; Kalenga, W.M.; Bogaert, J. Socio-Economic Value and Availability of Plant-Based Non-Timber Forest Products (NTFPs) within the Charcoal Production Basin of the City of Lubumbashi (DR Congo). Sustainability 2023, 15, 14943. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alongo, S.; Visser, M.; Drouet, T.; Kombele, F.; Colinet, G.; Bogaert, J. Effets de la fragmentation des forêts par l'agriculture itinérante sur la dégradation de quelques propriétés physiques d'un ferralso échantillonné à Yangambi, R.D. Congo. Tropicultura 2013, 31, 36–43. [Google Scholar]

- Besisa Nguba, T.; Bogaert, J.; Makana, J.-R.; Mate Mweru, J.-P.; Sambieni, K.R.; Bwazani Balandi, J.; Mumbere Musavandalo, C.; Bastin, J.-F. Assessing Forest Degradation in the Congo Basin: The Need to Broaden the Focus from Logging to Small-Scale Agriculture (A Systematic Review). Forests 2025, 16, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Turner, B. L.; Lambin, E. F.; Reenberg, A. The emergence of land change science for global environmental change and sustainability. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2007, 104, 52–20666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mujinya, B. B.; Adam, M.; Mees, F.; Bogaert, J.; Vranken, I.; Erens, H.; Baert, G.; Ngongo, M. L.; Van Ranst, E. Spatial patterns and morphology of termite (Macrotermes falciger) mounds in the Upper Katanga, D.R. Congo. Catena 2014, 114, 97–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Mpanda Mukenza, M.; Mwenya, I.K.; Muteya, H.K.; Nghonda, D.-D.N.; Mukendi, N.K.; Malaisse, F.; Kaj, F.M.; Mwembu, D.D.D.; Bogaert, J. Quantifying Forest Cover Loss during the COVID-19 Pandemic in the Lubumbashi Charcoal Production Basin (DR Congo) through Remote Sensing and Landscape Analysis. Resources 2024, 13, 95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Izakovičová, Z.; Špulerová, J.; Petrovič, F. Integrated Approach to Sustainable Land Use Management. Environments 2018, 5, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gatti, R. C. Ecological Peace Corridors: A new conservation strategy to protect human and biological diversity. Biological Conservation 2025, 302, 110947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, Y. S.; Malaisse, F.; Yona, J. M.; Mwamba, T. M.; Bogaert, J. Diversity, use and management of household-located fruit trees in two rapidly developing towns in Southeastern DR Congo. Urban Forestry & Urban Greening 2021, 63, 127220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Useni, Y.S.; Malaisse, F.; Cabala Kaleba, S.; Kalumba Mwanke, A.; Mwana Yamba, A.; Nkuku Khonde, C.; Bogaert, J.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F. Tree diversity and structure on green space of urban and peri-urban zones : The case of Lubumbashi City in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Urban Forestry and Urban Greening 2019, 41, 67–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, Y.; Wu, G.; Zhang, Z. Multi-Scale Remote Sensing Assessment of Ecological Environment Quality and Its Driving Factors in Watersheds: A Case Study of Huashan Creek Watershed in China. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 5633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vranken, I.; Adam, M.; Mujinya Bazirake, B.; Munyemba Kankumbi, F.; Baert, G.; Van Ranst, E.; Visser, M.; Bogaert, J. Termite mound identification through aerial photographic interpretation in Lubumbashi, Democratic Republic of the Congo : methodology evaluation. Tropical Conservation Science 2014, 7(4), 733–746. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Estenne, G. Cartographie des infrastructures vertes de Lubumbashi, l'importance de la prise en compte des variations saisonnières de la signature spectrale. Master Thesis, Gembloux Agro-Bio Tech, Université de Liège, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kabanyegeye, H.; Cirezi, N.C.; Muteya, H.K.; Mbarushimana, D.; Mukubu Pika, L.; Salomon, W.; Useni Sikuzani, Y.; Sambieni, K.R.; Masharabu, T.; Bogaert, J. Spatio-Temporal Analysis of Green Infrastructure along the Urban-Rural Gradient of the Cities of Bujumbura, Kinshasa and Lubumbashi. Land 2024, 13, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]