Submitted:

08 July 2025

Posted:

09 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Material and Methods

2.1. Plant Material

2.2. Experimental Work

2.2.1. Extraction Method (Cold Method)

2.2.2. Preliminary Phytochemical Examination of Crude Extracts

2.3. Amino Acids Determination

2.4. Cytotoxicity Assay

2.4.1. Cell Lines Used

2.4.2. MTT Cytotoxicity Assay

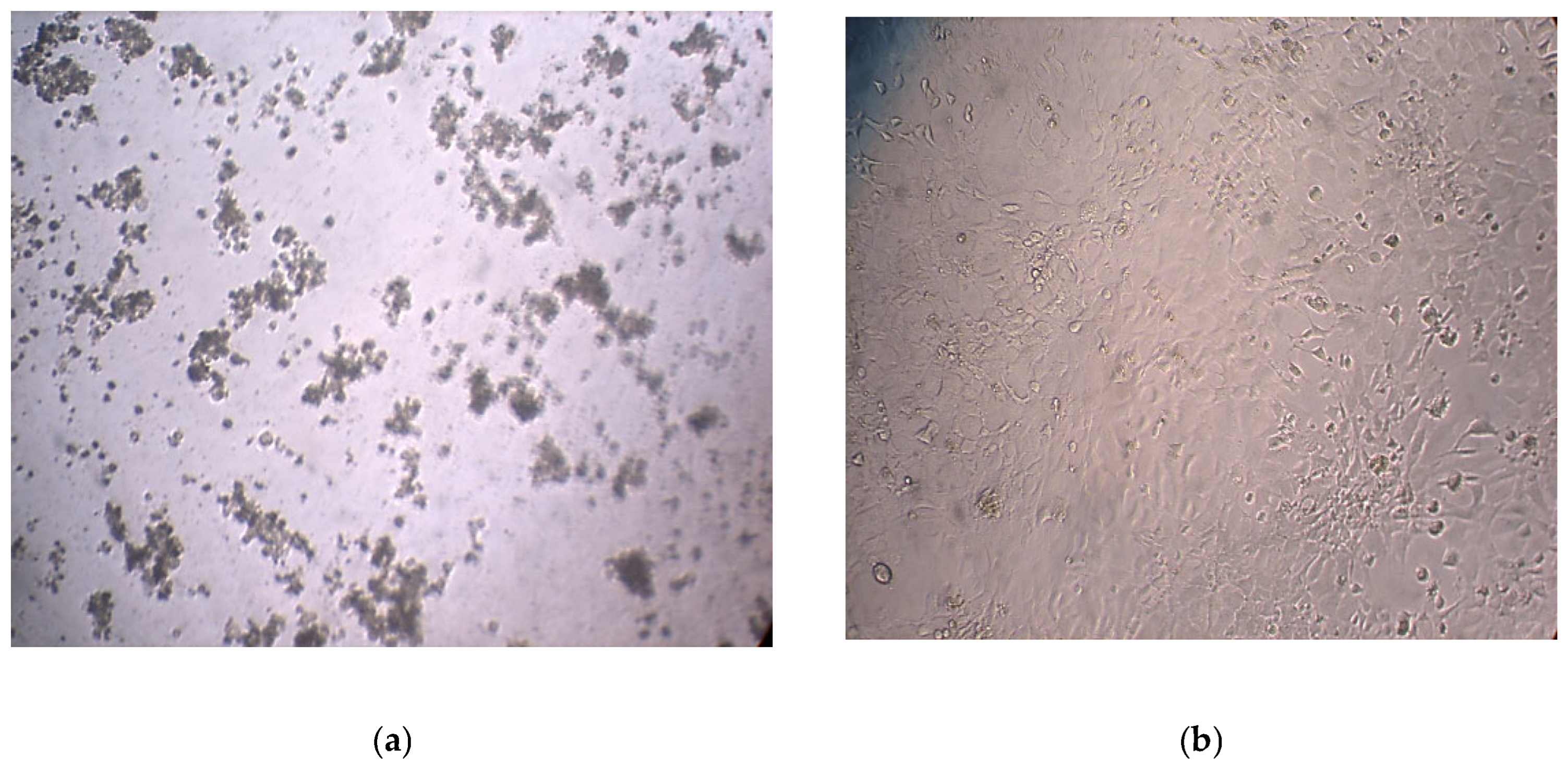

Cell Culture Conditions

MTT Procedure

2.5. DNA Damage

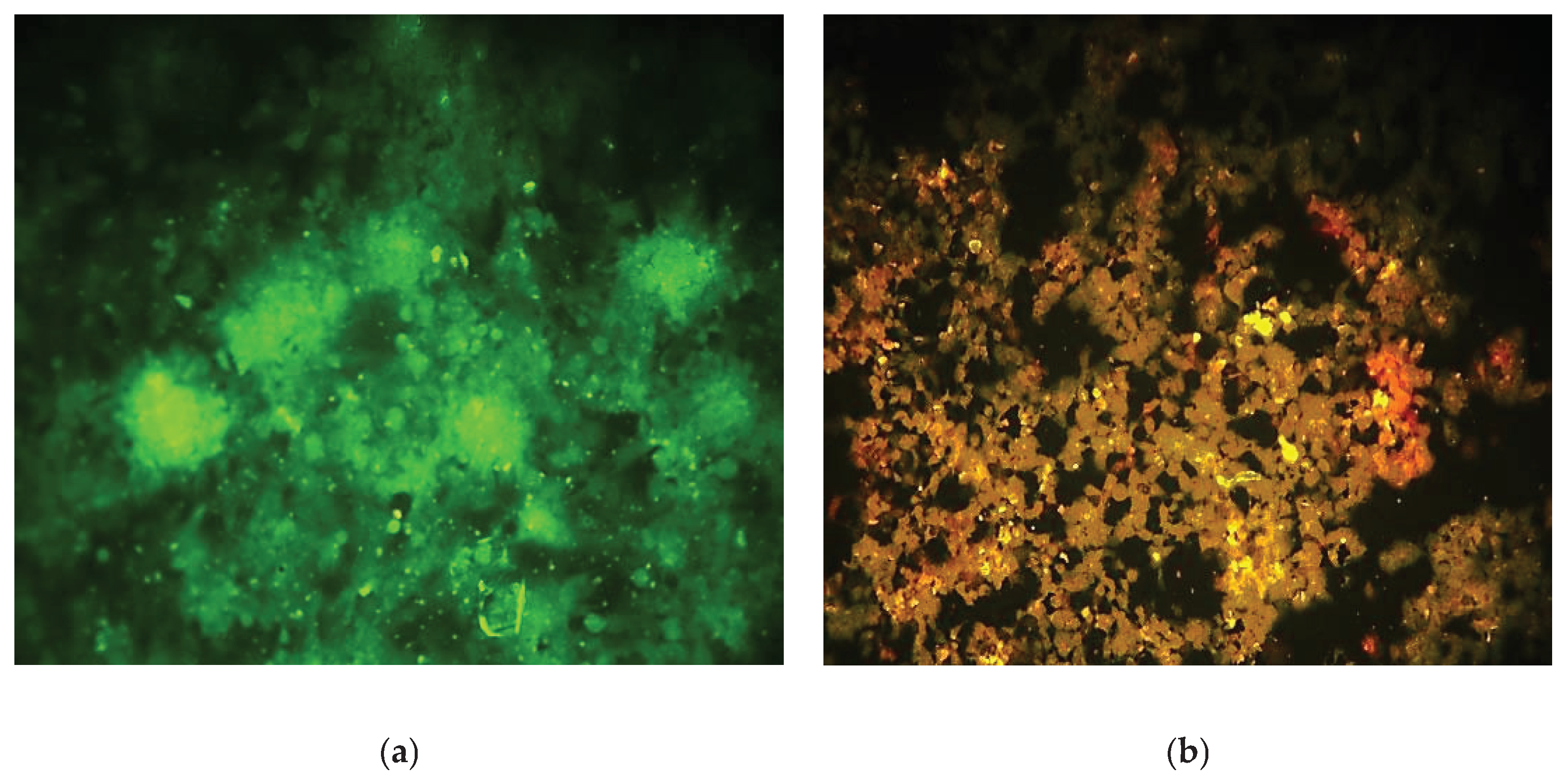

Apoptosis Estimation (Propidium Iodide/Acridine Orange Assay)

3. Results

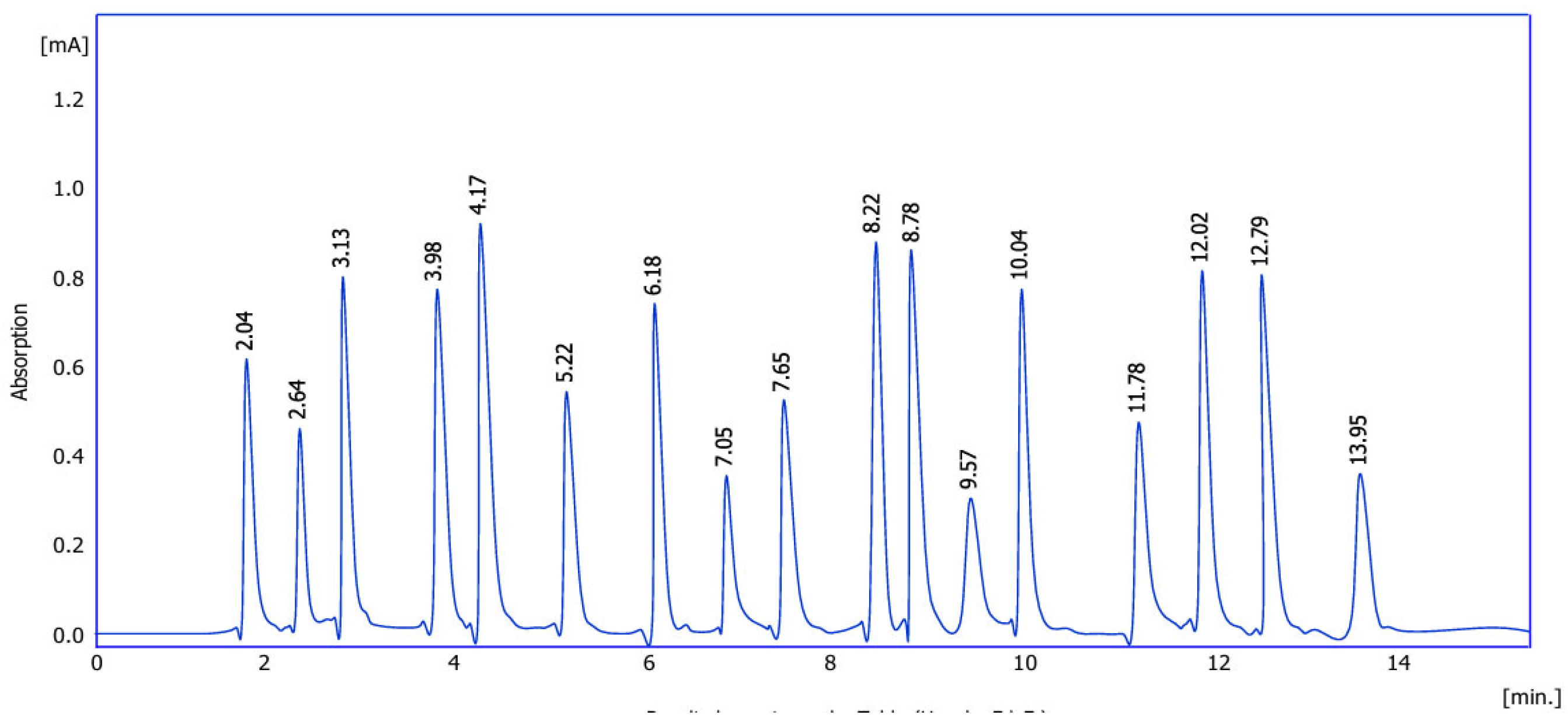

3.1. Amino Acid Detection

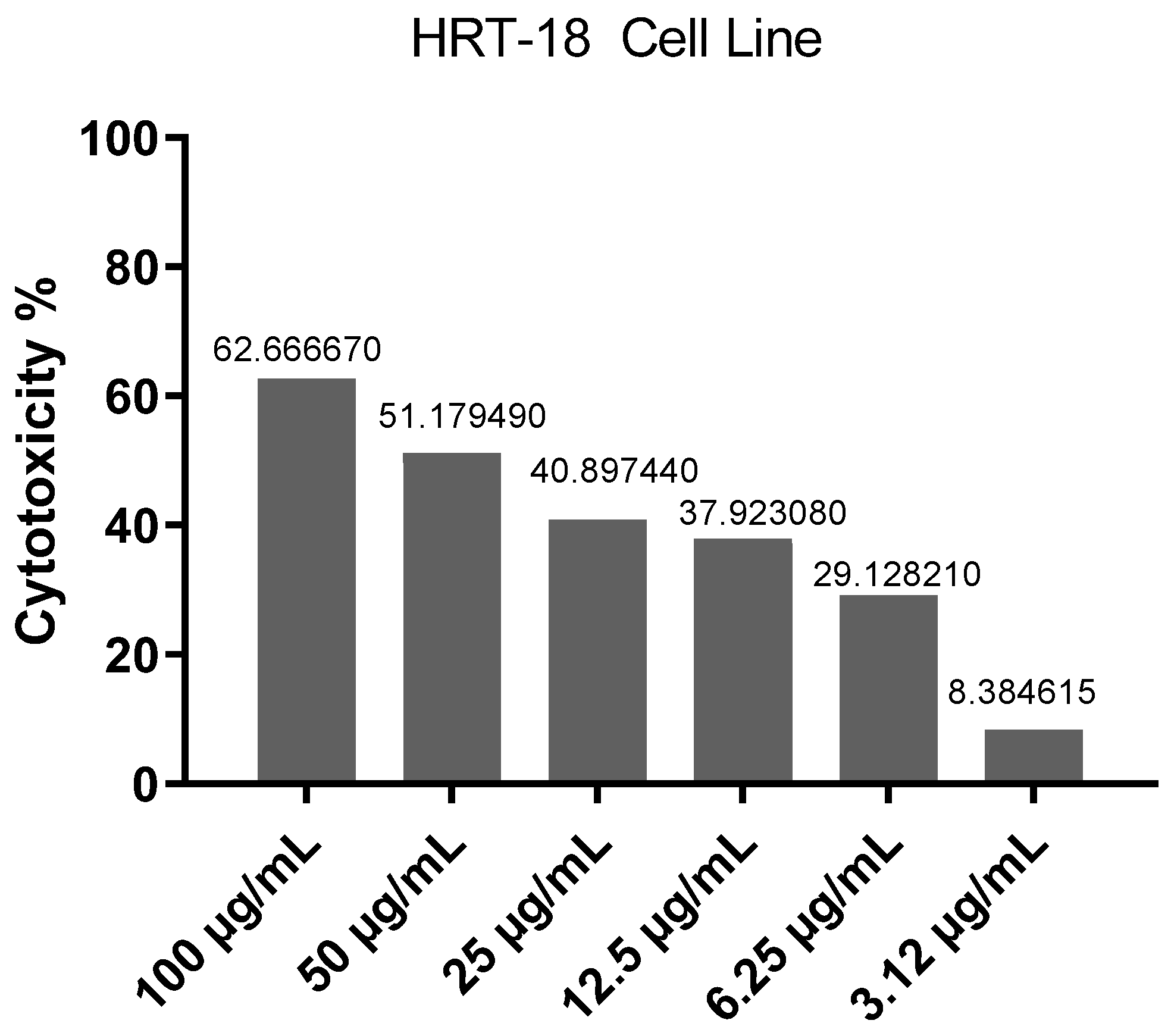

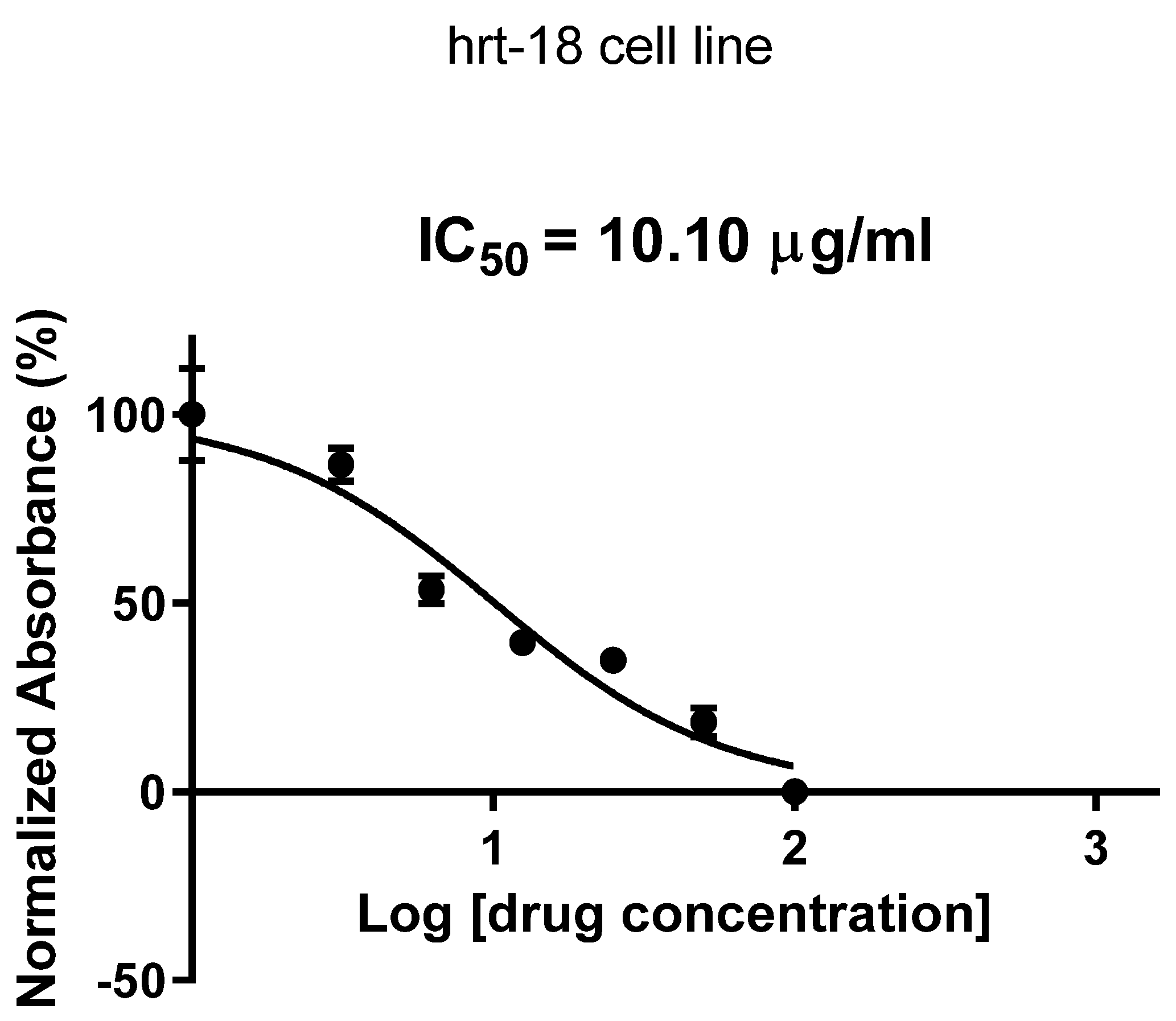

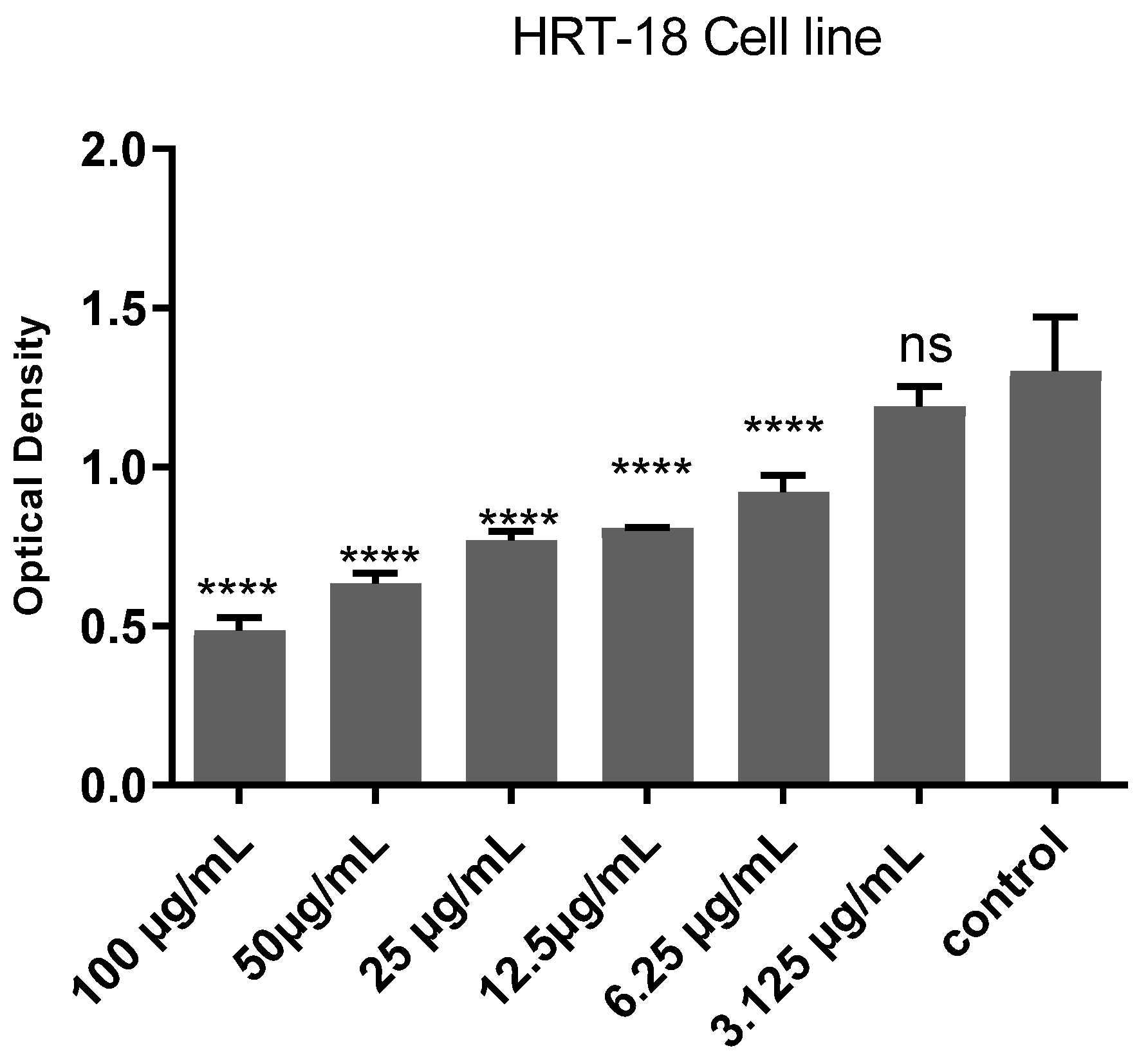

3.2. Cytotoxic Effects Evaluation

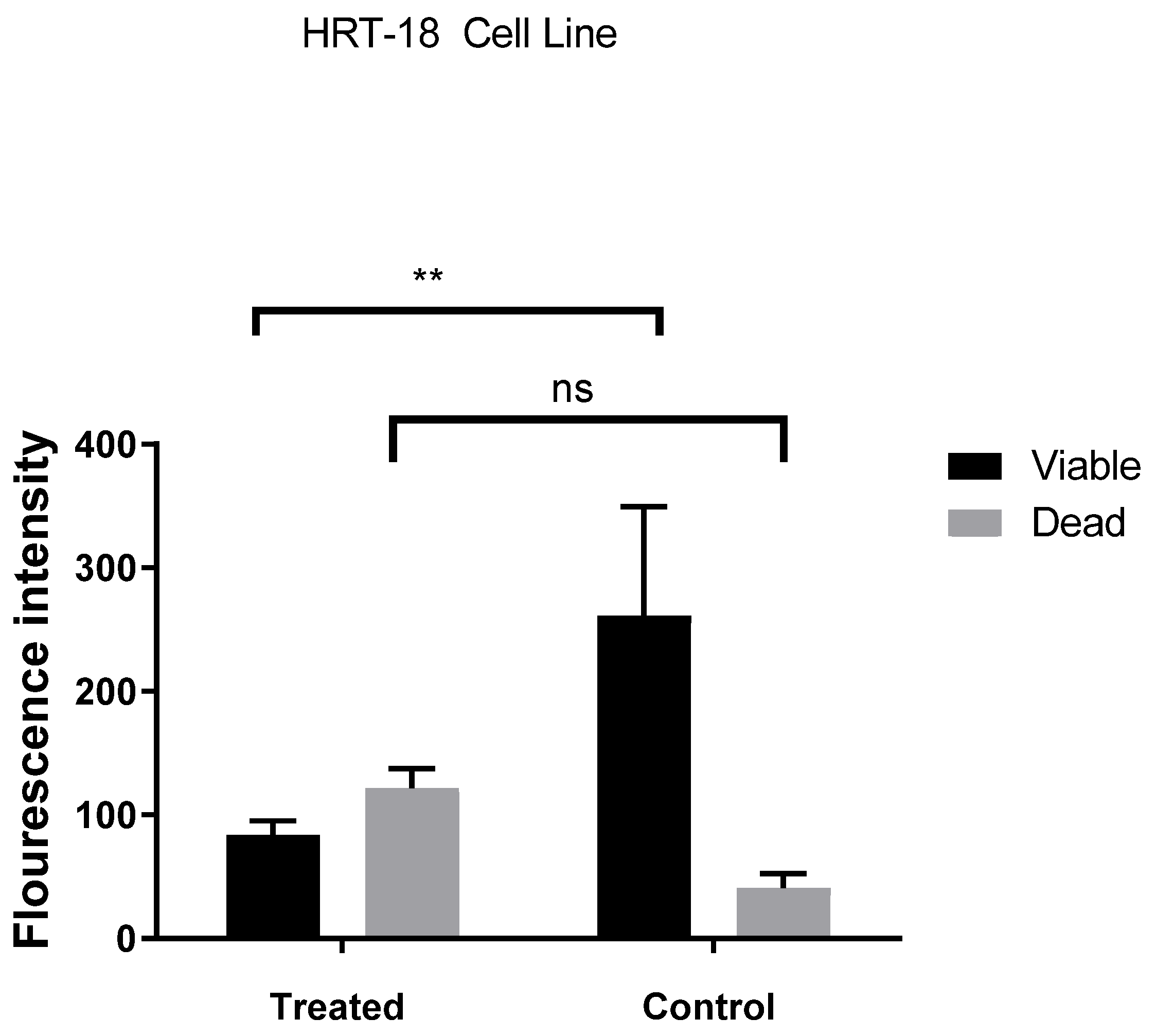

3.3. DNA Damage Analysis

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

References

- Javanmardi, J.; Khalighi, A.; Kashi, A.; Bais, H.P.; Vivanco, J.M. Chemical Characterization of Basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) Found in Local Accessions and Used in Traditional Medicines in Iran. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2002, 50, 5878–5883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan A, Dhananjayan R. Cardiac stimulant activity of Ocimum basilicum Linn. extracts. Indian J Pharmacol 2004, 36, 163–166. [Google Scholar]

- Hussain, A.I.; Anwar, F.; Sherazi, S.T.H.; Przybylski, R. Chemical composition, antioxidant and antimicrobial activities of basil (Ocimum basilicum) essential oils depends on seasonal variations. Food Chem. 2008, 108, 986–995. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; Alderson, P.G.; Wright, C.J. Variation in the Essential Oils in Different Leaves of Basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) at Day Time. Open Hortic. J. 2009, 2, 13–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayaweera DMA. Medicinal Plants, (Indigenous and Exotic) Used in Ceylon. Part III. Colombo: The National Science Foundation of Sri Lanka; 1981. 101-3.

- Bhatti, H.A.; Tehseen, Y.; Maryam, K.; Uroos, M.; Siddiqui, B.S.; Hameed, A.; Iqbal, J. Identification of new potent inhibitor of aldose reductase from Ocimum basilicum. Bioorganic Chem. 2017, 75, 62–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Dakar, A.Y.; Shalaby, S.M.; Nemetallah, B.R.; Saleh, N.E.; Sakr, E.M.; Toutou, M.M. Possibility of using basil (Ocimum basilicum) supplementation in Gilthead sea bream (Sparus aurata) diet. Egypt. J. Aquat. Res. 2015, 41, 203–210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, L.; He, J.; Luo, L.; Wang, K. Targeting the Interplay of Autophagy and ROS for Cancer Therapy: An Updated Overview on Phytochemicals. Pharmaceuticals 2023, 16, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devika, T.; Shashi, V. Pharmacognostical and phytochemical investigation of Tulsi plants available in Western Bareilly region. Global Journal of Pharmacology 2016, 9, 60–63. [Google Scholar]

- Lopez MJ, Mohiuddin SS. Biochemistry, Essential Amino Acids. [Updated 2024 Apr 30]. In: StatPearls [Internet]. S: Treasure Island (FL), 2025.

- Calderón Bravo, H.; Vera Céspedes, N.; Zura-Bravo, L.; Muñoz, L.A. Basil Seeds as a Novel Food, Source of Nutrients and Functional Ingredients with Beneficial Properties: A Review. Foods 2021, 10, 1467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cragg, G.M.; Pezzuto, J.M. Natural Products as a Vital Source for the Discovery of Cancer Chemotherapeutic and Chemopreventive Agents. Med Princ. Pr. 2015, 25, 41–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Laversanne, M.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A.; Bray, F. Global Cancer Statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN Estimates of Incidence and Mortality Worldwide for 36 Cancers in 185 Countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2021, 71, 209–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murakami, T.; Otsubo, S.; Namitome, R.; Shiota, M.; Inokuchi, J.; Takeuchi, A.; Kashiwagi, E.; Tatsugami, K.; Eto, M. Clinical factors affecting perioperative outcomes in robot-assisted radical prostatectomy. Mol. Clin. Oncol. 2018, 9, 575–581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parekh, J.; Chanda, S. In vitro antimicrobial activity and phytochemical analysis of some Indian medicinal plants. Turkish Journal of Biology 2007, 31, 53–58. [Google Scholar]

- Tiwari, P.; Kumar, B.; Kaur, M.; Kaur, G.; Kaur, H. Phytochemical screening and extraction: A review. Internationale Pharmaceutica Sciencia 2011, 1, 98–106. [Google Scholar]

- Dahl-Lassen, R.; van Hecke, J.; Jørgensen, H.; Bukh, C.; Andersen, B.; Schjoerring, J.K. High-throughput analysis of amino acids in plant materials by single quadrupole mass spectrometry. Plant Methods 2018, 14, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scriver CR, Beaudet AL, Valle D, Sly WS, Childs B, Kinzler KW, Vogelstein B, eds. The Metabolic and Molecular Bases of Inherited Disease. 8th ed. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill, Inc; 2001. 1665–2105.

- Salman MI, Emran MA, Al-Shammari AM. Spheroid-formation 3D engineering model assay for in vitro assessment and expansion of cancer cells. In AIP Conference Proceedings 2021 Nov 11 (Vol. 2372, No. 1). AIP Publishing. [CrossRef]

- Al-Shammari, A.M.; Salman, M.I. Antimetastatic and antitumor activities of oncolytic NDV AMHA1 in a 3D culture model of breast cancer. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2024, 11, 1331369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salman, M.I.; Al-Shammari, A.M.; Emran, M.A. 3-Dimensional coculture of breast cancer cell lines with adipose tissue–Derived stem cells reveals the efficiency of oncolytic Newcastle disease virus infection via labeling technology. Front. Mol. Biosci. 2022, 9, 754100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, G. Functional amino acids in nutrition and health. Amino Acids 2013, 45, 407–411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holeček, M. Origin and Roles of Alanine and Glutamine in Gluconeogenesis in the Liver, Kidneys, and Small Intestine under Physiological and Pathological Conditions. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 7037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dingledine R, McBain CJ. Glutamate and Aspartate Are the Major Excitatory Transmitters in the Brain. In: Siegel GJ, Agranoff BW, Albers RW, et al., editors. Basic Neurochemistry: Molecular, Cellular and Medical Aspects. 6th edition. Philadelphia: Lippincott-Raven; 1999.

- Chiang, F.-F.; Chao, T.-H.; Huang, S.-C.; Cheng, C.-H.; Tseng, Y.-Y.; Huang, Y.-C. Cysteine Regulates Oxidative Stress and Glutathione-Related Antioxidative Capacity before and after Colorectal Tumor Resection. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 9581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kurhaluk, N.; Tkaczenko, H. L-Arginine and Nitric Oxide in Vascular Regulation—Experimental Findings in the Context of Blood Donation. Nutrients 2025, 17, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bakhtiar, Z.; Mirjalili, M.H.; Hassandokht, M. Nutritional composition of sweet basil (Ocimum basilicum L.) agro-ecotypic populations: Prospecting and selecting for use in food products. Food Humanit. 2024, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Enegide, C.; C, O.C. Ocimum Species: Ethnomedicinal Uses, Phytochemistry and Pharmacological Importance. Int. J. Curr. Res. Physiol. Pharmacol. (IJCRPP) 2021, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kooti, W.; Farokhipour, M.; Asadzadeh, Z.; Ashtary-Larky, D.; Asadi-Samani, M. The role of medicinal plants in the treatment of diabetes: a systematic review. Electron. Physician 2016, 8, 1832–1842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sivak, K.V.; Stosman, K.I.; Lesiovskaya, E.E. Bioactive compounds of medicinal plants with anti-herpes effect (part 1). Rastitelnye resursy 2024, 60, 3–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattanayak, P.; Behera, P.; Das, D.; Panda, S.K. Ocimum sanctum Linn. A reservoir plant for therapeutic applications: An overview. Pharmacogn. Rev. 2010, 4, 95–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’archivio, M.; Santangelo, C.; Scazzocchio, B.; Varì, R.; Filesi, C.; Masella, R.; Giovannini, C. Modulatory Effects of Polyphenols on Apoptosis Induction: Relevance for Cancer Prevention. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2008, 9, 213–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitsiou, E.; Pappa, A. Anticancer Activity of Essential Oils and Other Extracts from Aromatic Plants Grown in Greece. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Almutairi, B.O.; Alsayadi, A.I.; Abutaha, N.; Al-Mekhlafi, F.A.; Wadaan, M.A.; Ali, A. [Retracted] Evaluation of the Anticancer Potential of Morus nigra and Ocimum basilicum Mixture against Different Cancer Cell Lines: An In Vitro Evaluation. BioMed Res. Int. 2023, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, M.A.; Zachary, J.F. Mechanisms and Morphology of Cellular Injury, Adaptation, and Death 11 For a glossary of abbreviations and terms used in this chapter see E-Glossary 1-1. Pathol. Basis Vet. Dis. 2017, 2–43.e19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| No | Reten. Time [min] | Area [mAU.s] | Height [mAU] | Amount (g/100 g) | Calculation | Peak type | Compound Name |

| 1 | 2.04 | 4562.9 | 604.7 | 17.45 | Calibration carve | Order | Aspartic acid |

| 2 | 2.64 | 4152.6 | 643.6 | 26.09 | Calibration carve | Order | Glycine |

| 3 | 3.13 | 6325.9 | 794.9 | 24.12 | Calibration carve | Order | Lysine |

| 4 | 3.98 | 5854.0 | 789.8 | 27.88 | Calibration carve | Order | Serine |

| 5 | 4.17 | 6214.5 | 835.7 | 23.65 | Calibration carve | Order | Threonine |

| 6 | 5.22 | 5062.6 | 594.4 | 23.54 | Calibration carve | Order | Isoleucine |

| 7 | 6.18 | 6541.8 | 781.1 | 29.08 | Calibration carve | Order | Alanine |

| 8 | 7.05 | 4562.6 | 386.5 | 35.65 | Calibration carve | Order | Valine |

| 9 | 7.65 | 4369.0 | 549.6 | 18.99 | Calibration carve | Order | Tyrosine |

| 10 | 8.22 | 7125.8 | 827.4 | 26.14 | Calibration carve | Order | Arginine |

| 11 | 8.78 | 10325.6 | 812.7 | 24.15 | Calibration carve | Order | Cysteine |

| 12 | 9.57 | 6521.4 | 284.8 | 19.08 | Calibration carve | Order | Methionine |

| 13 | 10.04 | 10568.9 | 741.9 | 21.65 | Calibration carve | Order | Proline |

| 14 | 11.78 | 8542.6 | 418.5 | 28.9 | Calibration carve | Order | Histidine |

| 15 | 12.02 | 6985.8 | 719.4 | 30.65 | Calibration carve | Order | Lucien |

| 16 | 12.79 | 11256.6 | 712.1 | 27.44 | Calibration carve | Order | Glutamic acid |

| 17 | 13.95 | 3565.0 | 362.3 | 38.0 | Calibration carve | Order | Phenylalanine |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).