Submitted:

07 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

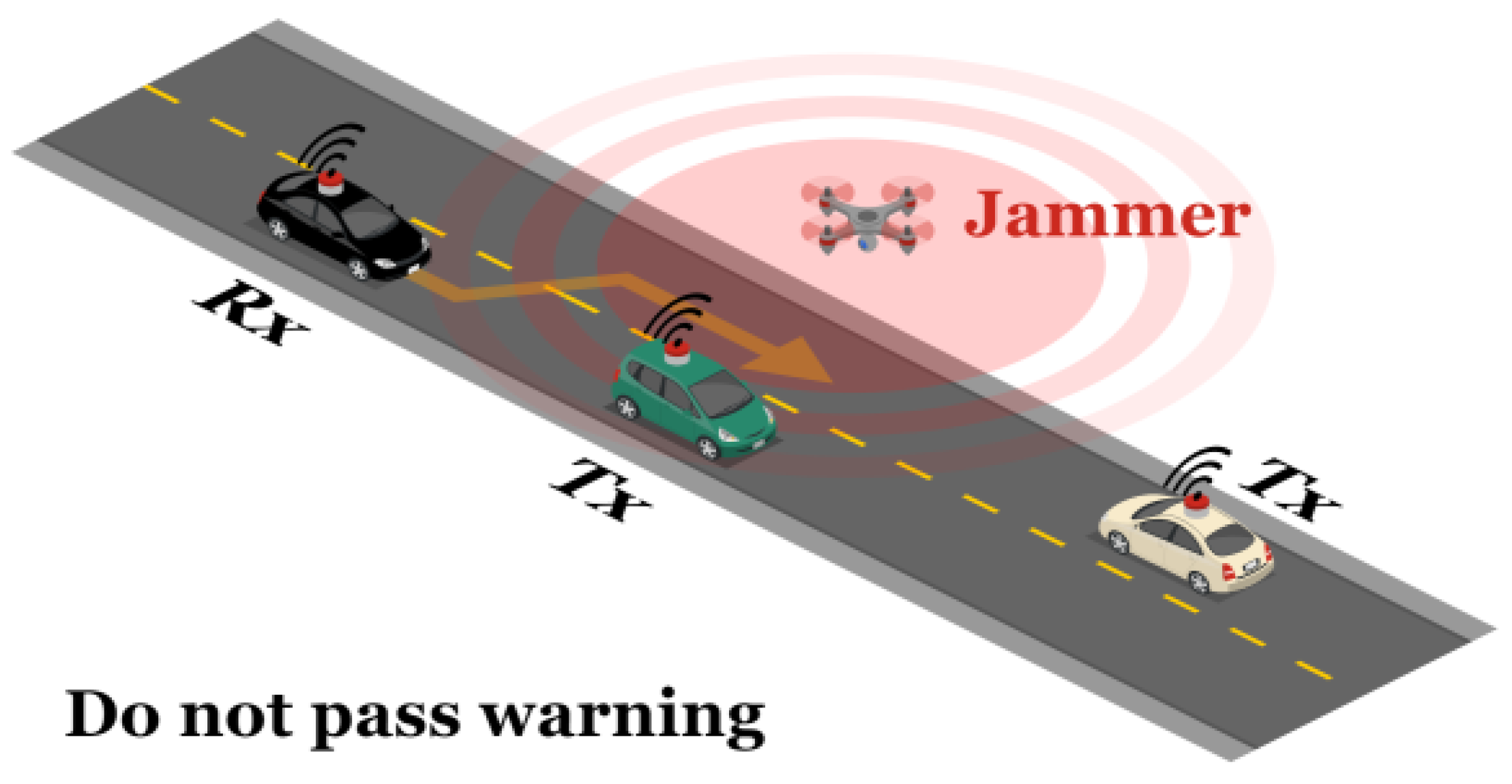

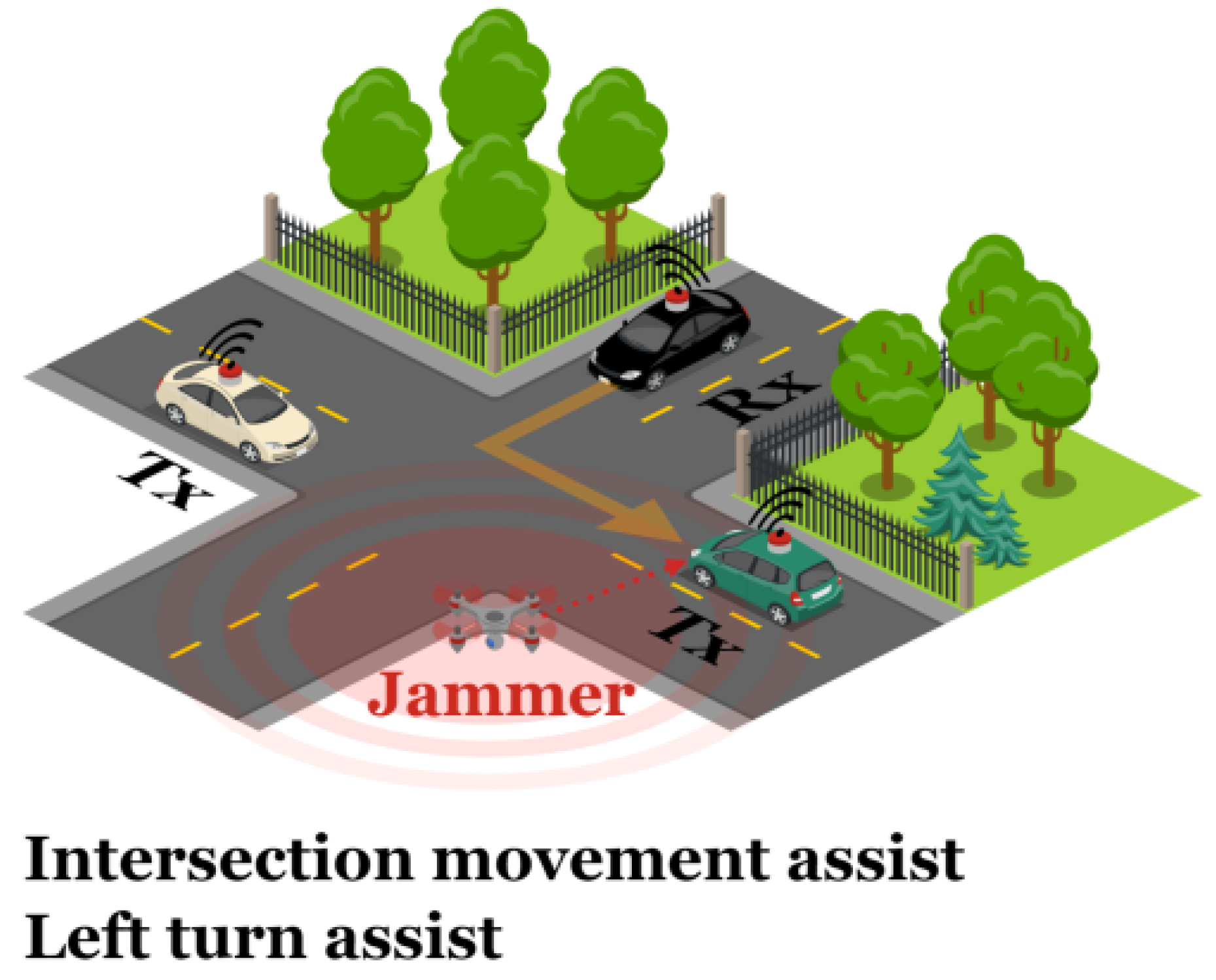

- Attack-aware V2X scenarios. Two safety-critical Cooperative-ITS use cases—Do Not Pass Warning (DNPW) and Intersection Movement Assist (IMA)—are modeled in detail. Each scenario is extended to include an adversary that injects intentional Radio Frequency (RF) interference while vehicles perform standard maneuvers.

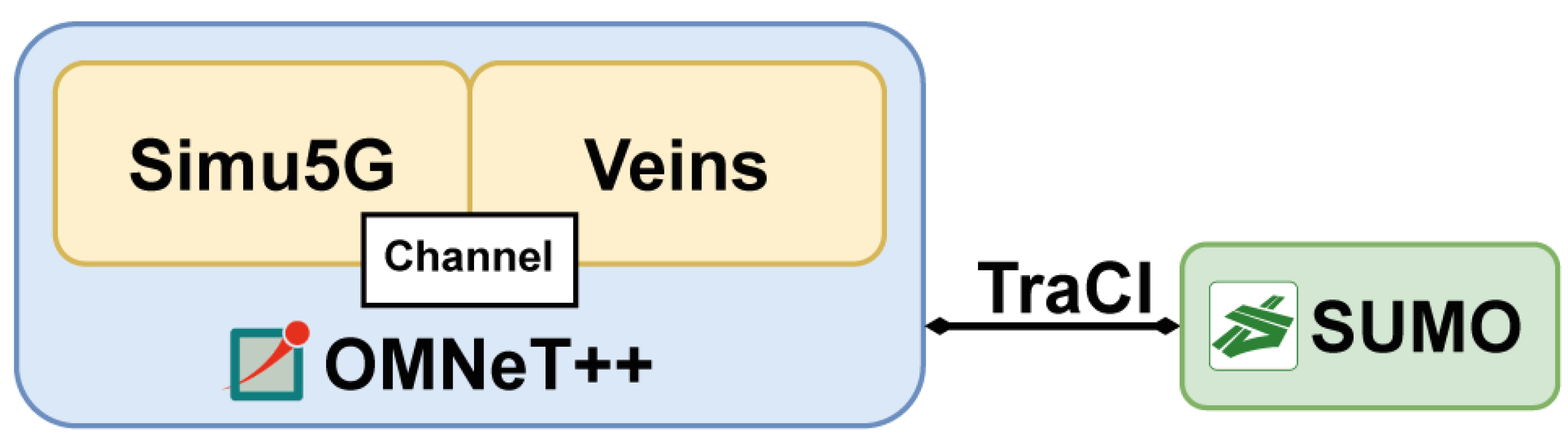

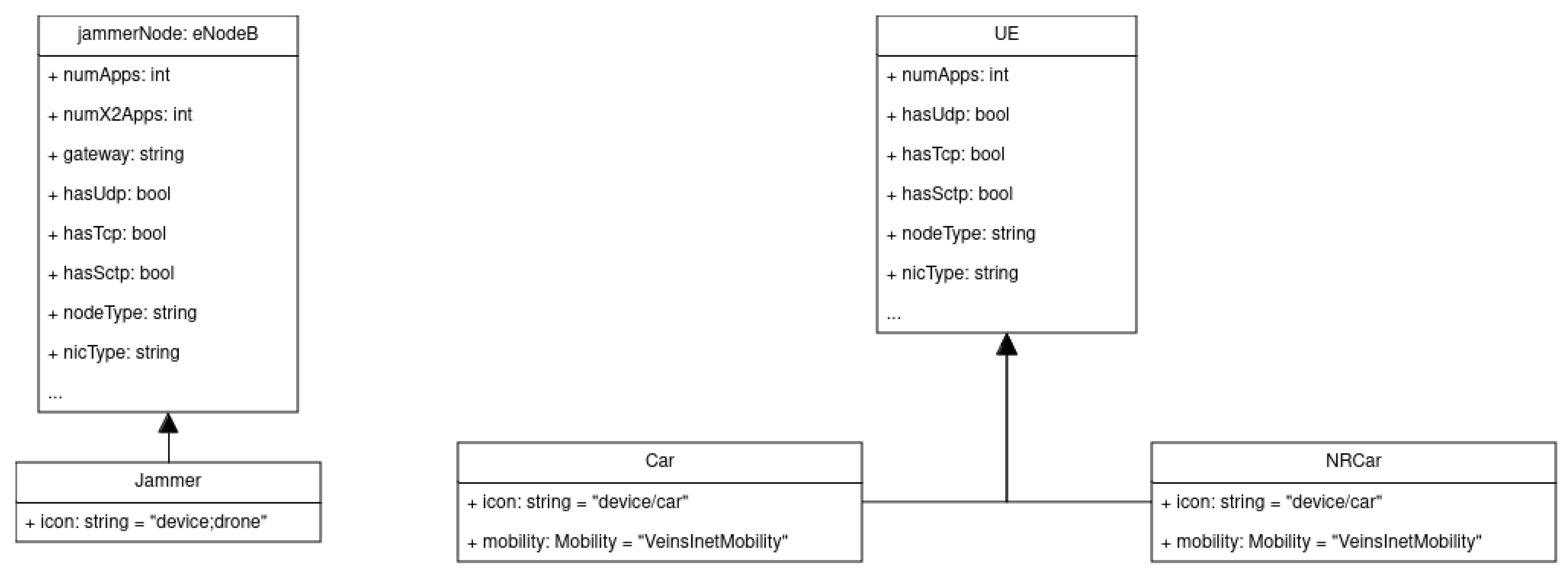

- Modular jamming framework for OMNeT++/Simu5G. We introduce reusable classes implementing NR-V2X PHY/MAC operation and four representative jamming strategies (constant, reactive, deceptive, and random). The code is fully integrated with Veins and SUMO, enabling repeatable network and mobility co-simulation.

- Comprehensive simulation assessment. The impact of the above jamming types on latency, packet-error probability, inter-vehicle spacing, and collision risk is quantified for both DNPW and IMA, revealing the most disruptive attack patterns and their dependence on traffic dynamics.

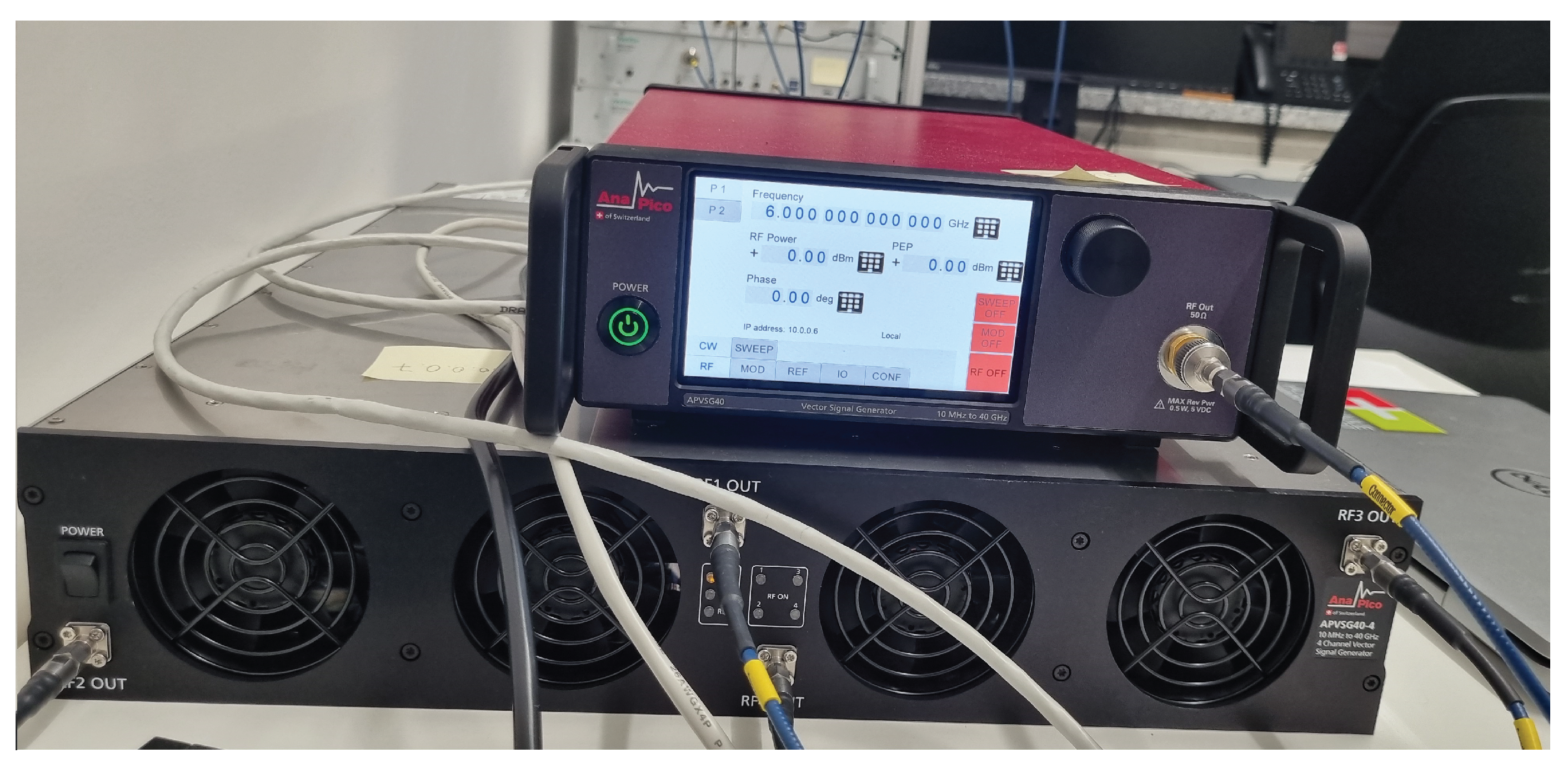

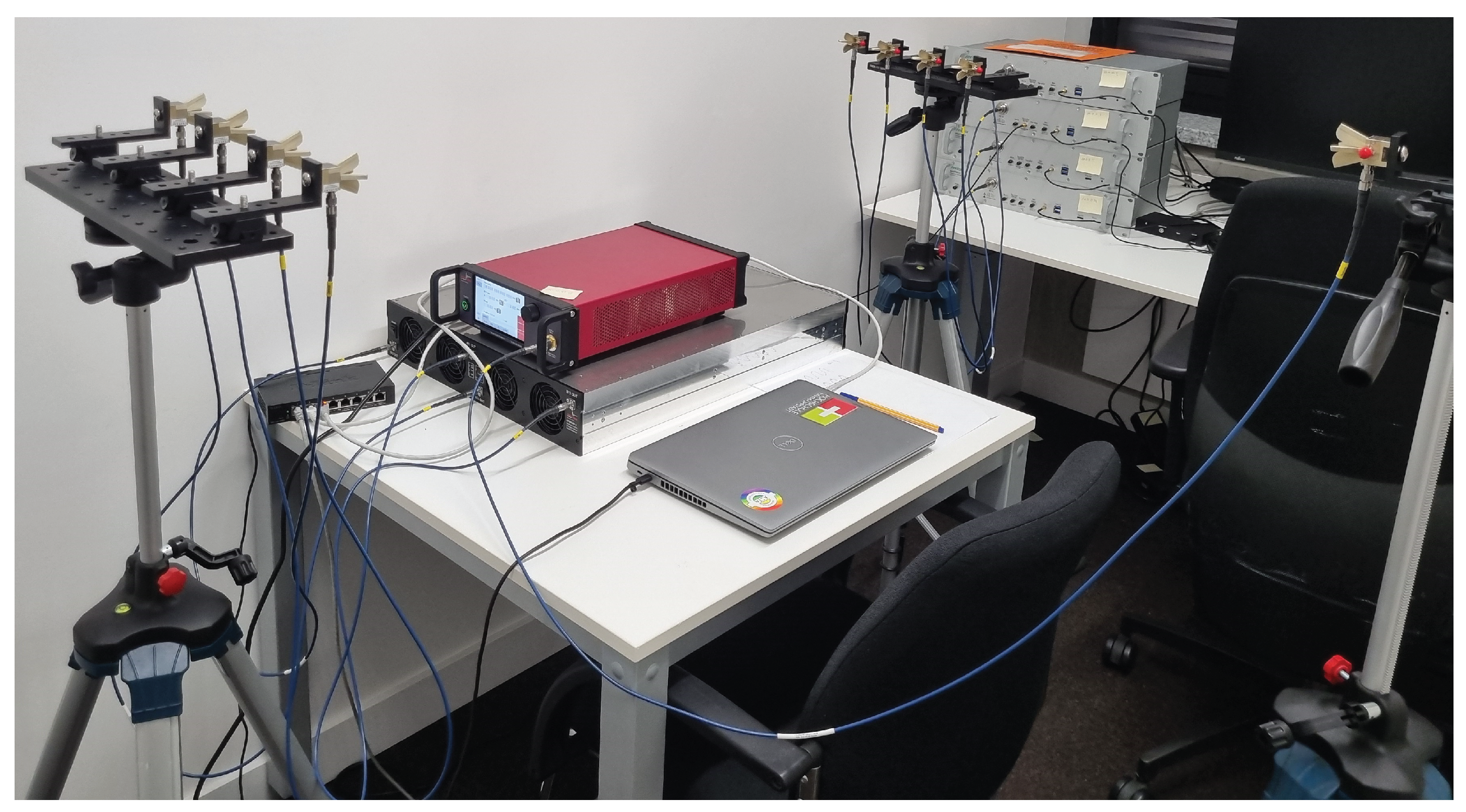

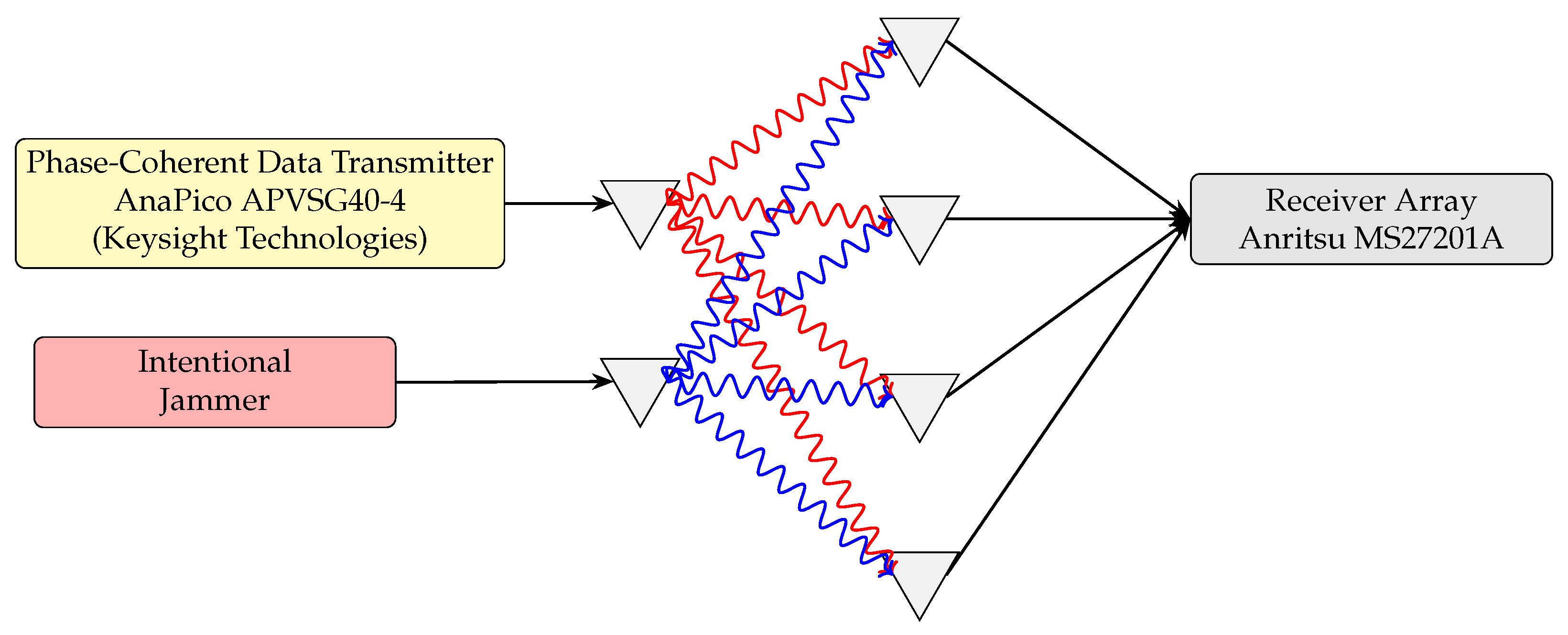

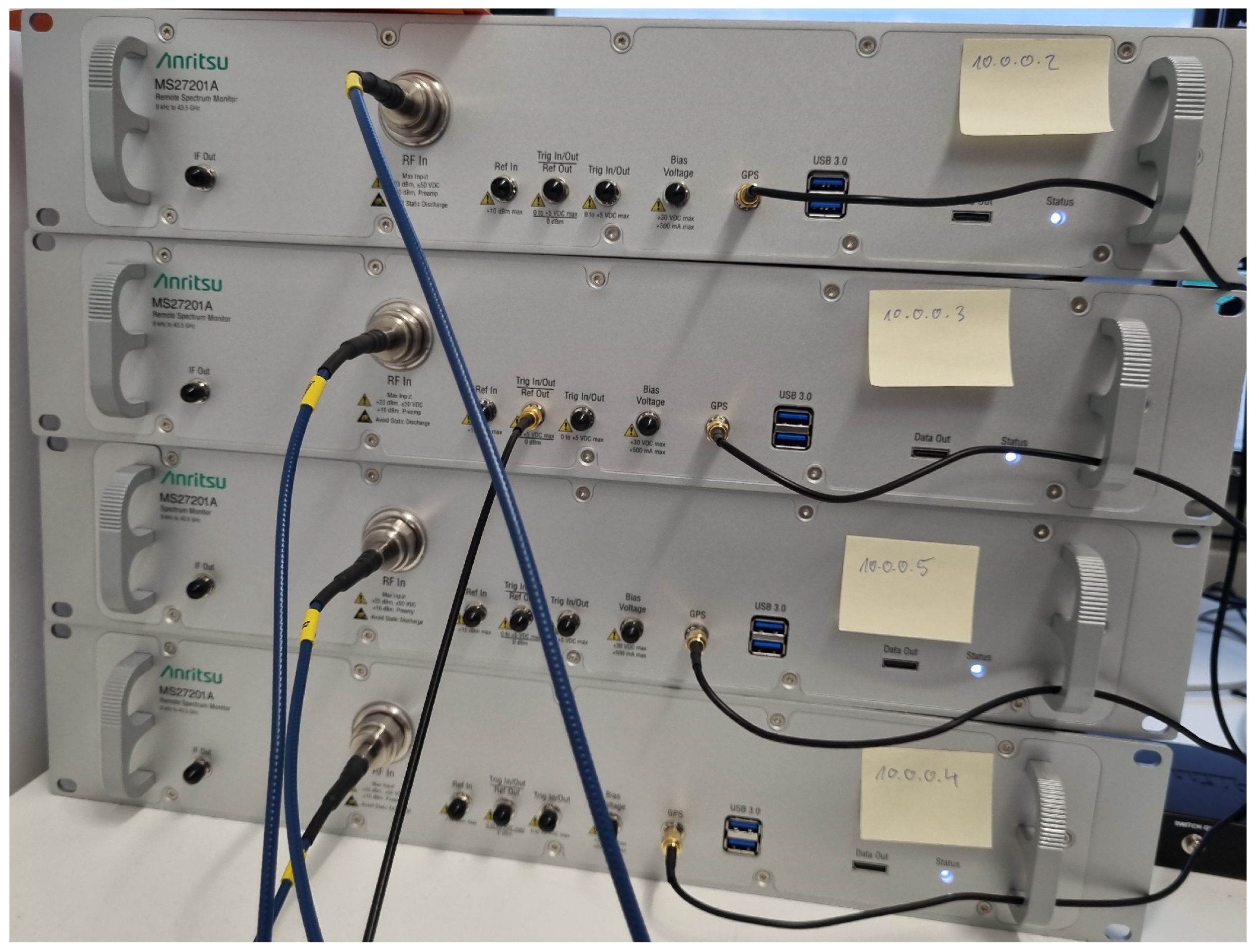

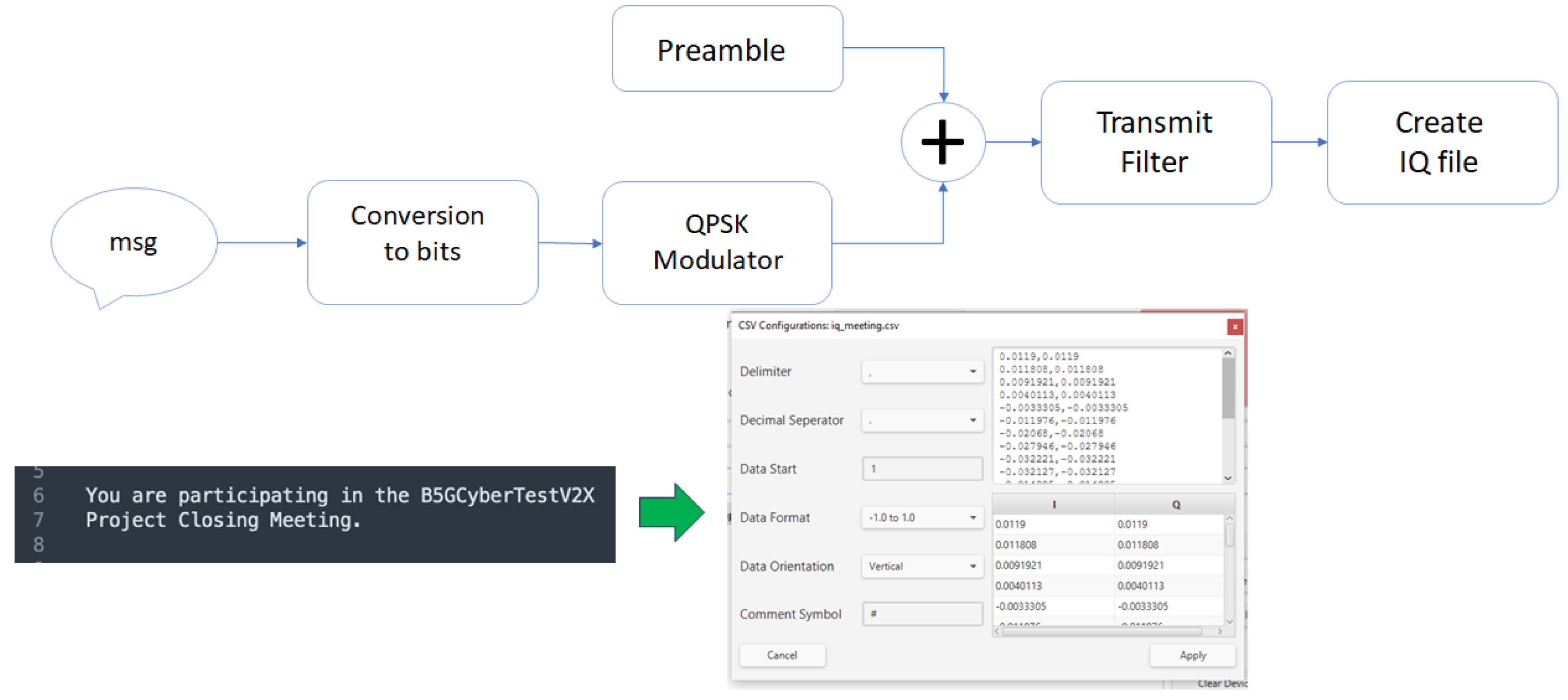

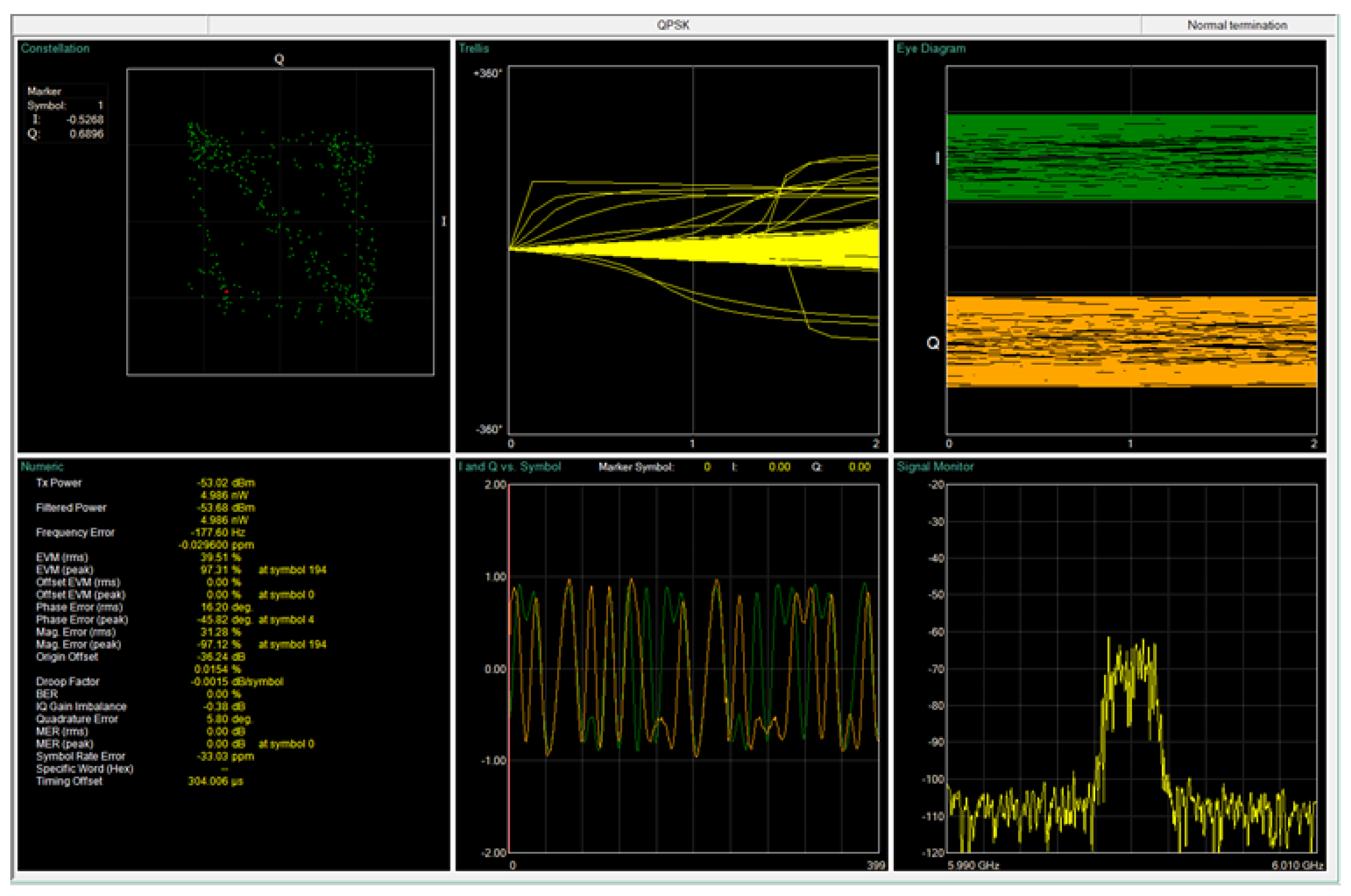

- Hardware-in-the-loop validation. A laboratory testbed—comprising one AnaPico APVSG40-4 signal generator (featuring four independent RF outputs), one dedicated jamming generator, and a four-channel Anritsu MS27201A receiver array—was built to replicate the wireless conditions used in the simulation. Measured degradation in constellation quality, Error Vector Magnitude (EVM), and message intelligibility corroborates the simulation findings.

- Design insights for resilient NR-V2X. By cross-analyzing simulation and experimental results, we identify parameter ranges (e.g., jammer bandwidth and power) that critically affect system performance and outline countermeasures that can be incorporated into future V2X protocol and detector designs.

2. State of the Art

3. Simulation Study

3.1. Simulation Scenarios

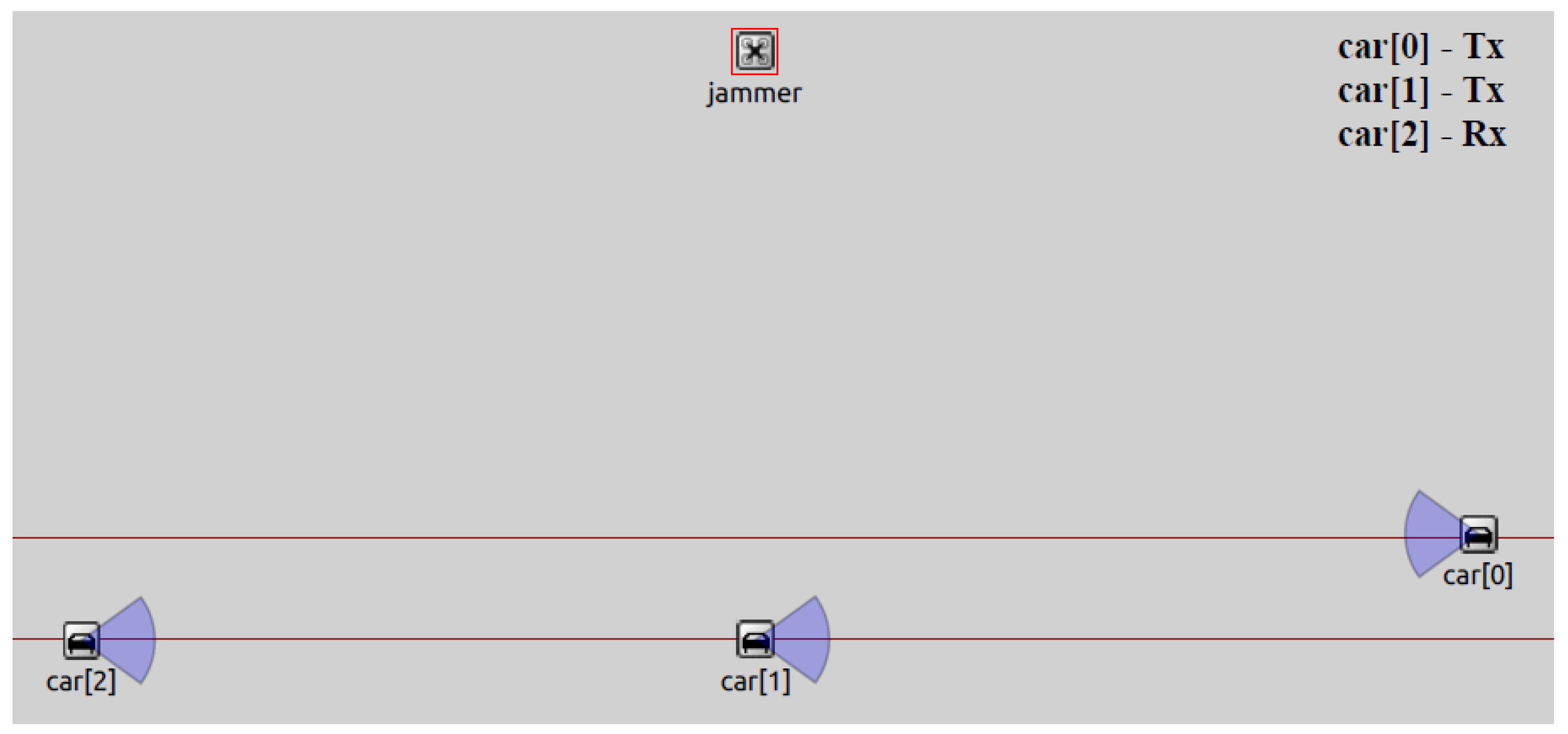

3.1.1. Scenario 1: DNPW

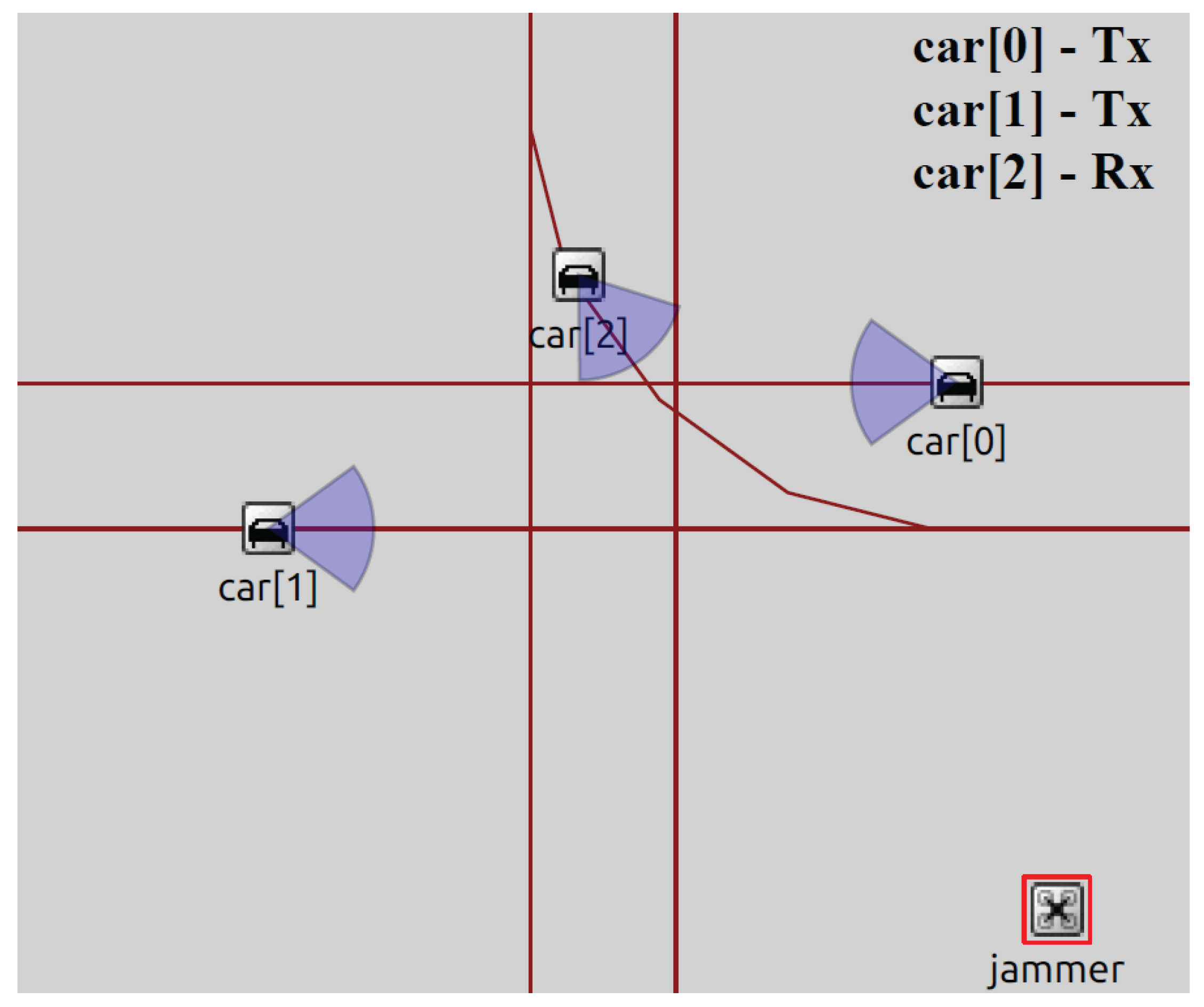

3.1.2. Scenario 2: IMA

3.2. Simulation Framework

3.2.1. Proposed Solution

3.2.2. OMNeT++ Class Implementation

3.3. Simulation Results

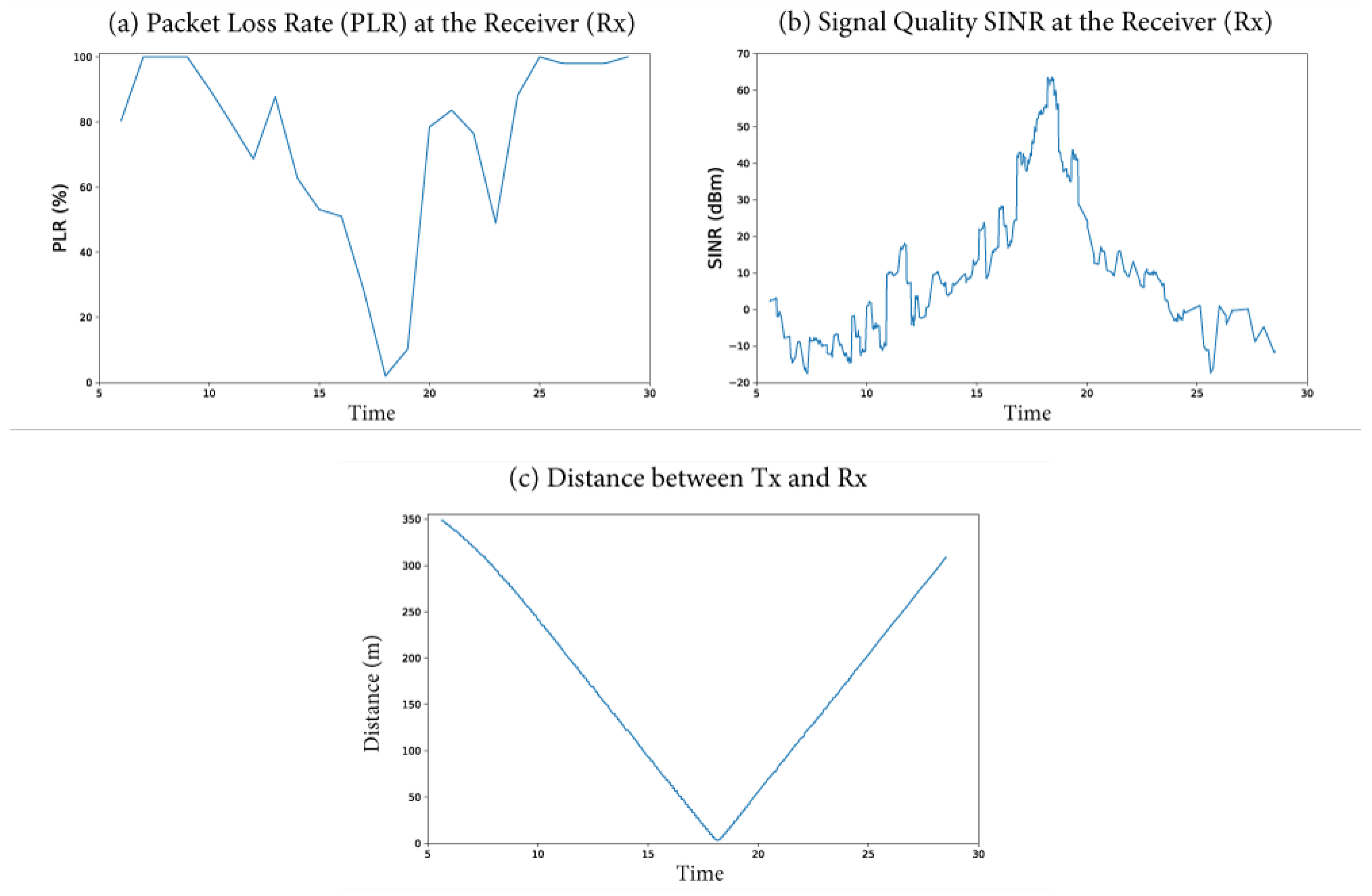

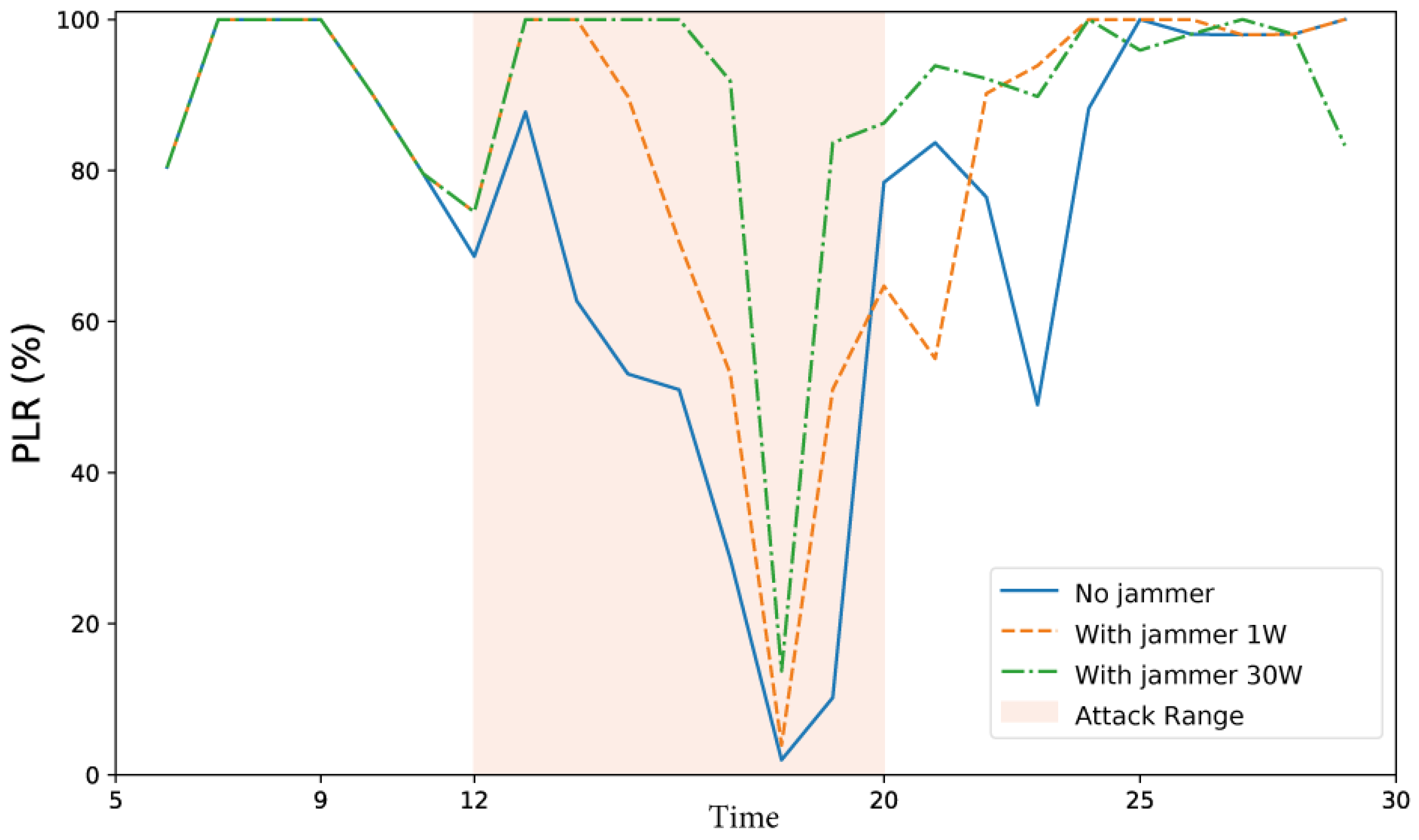

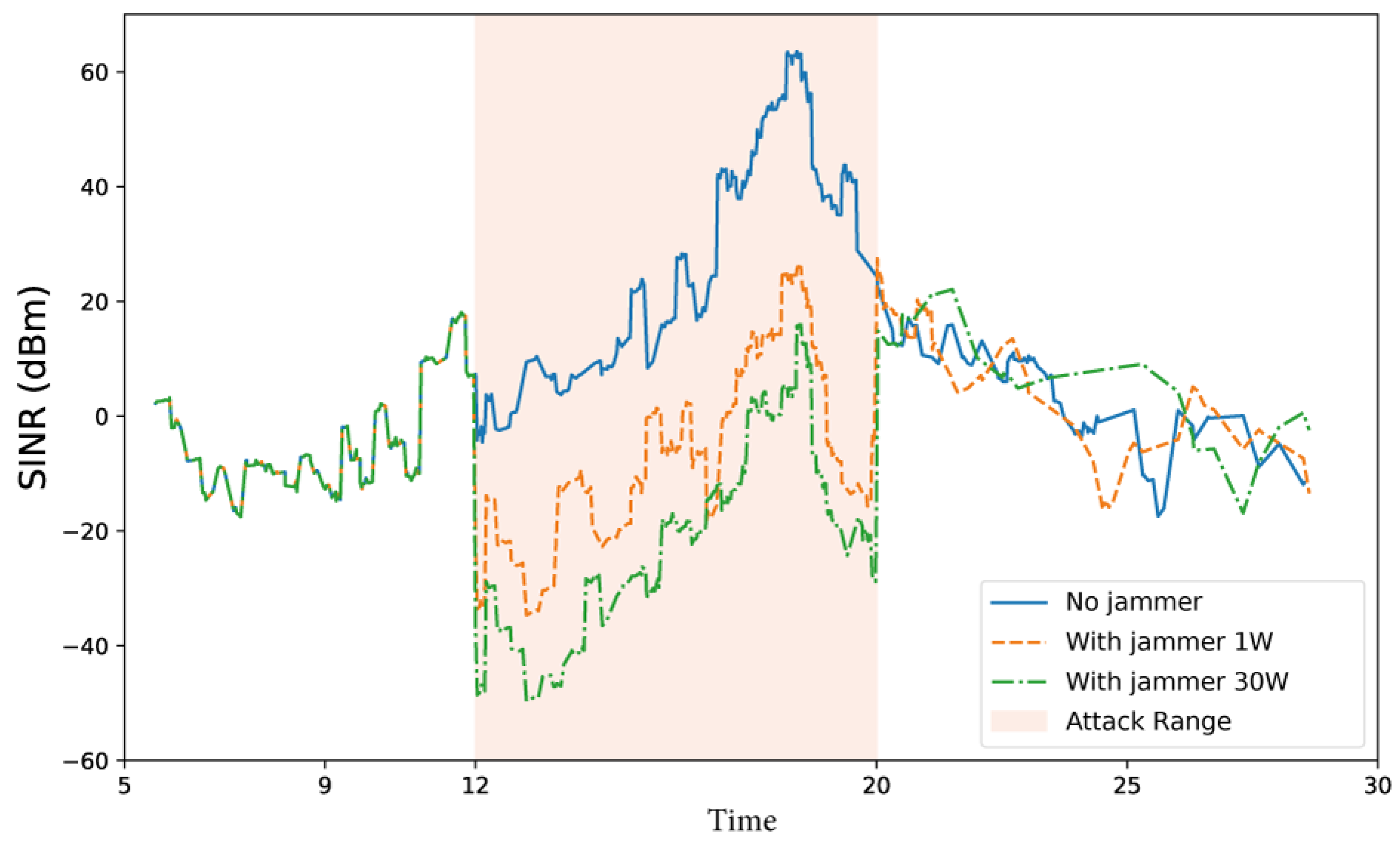

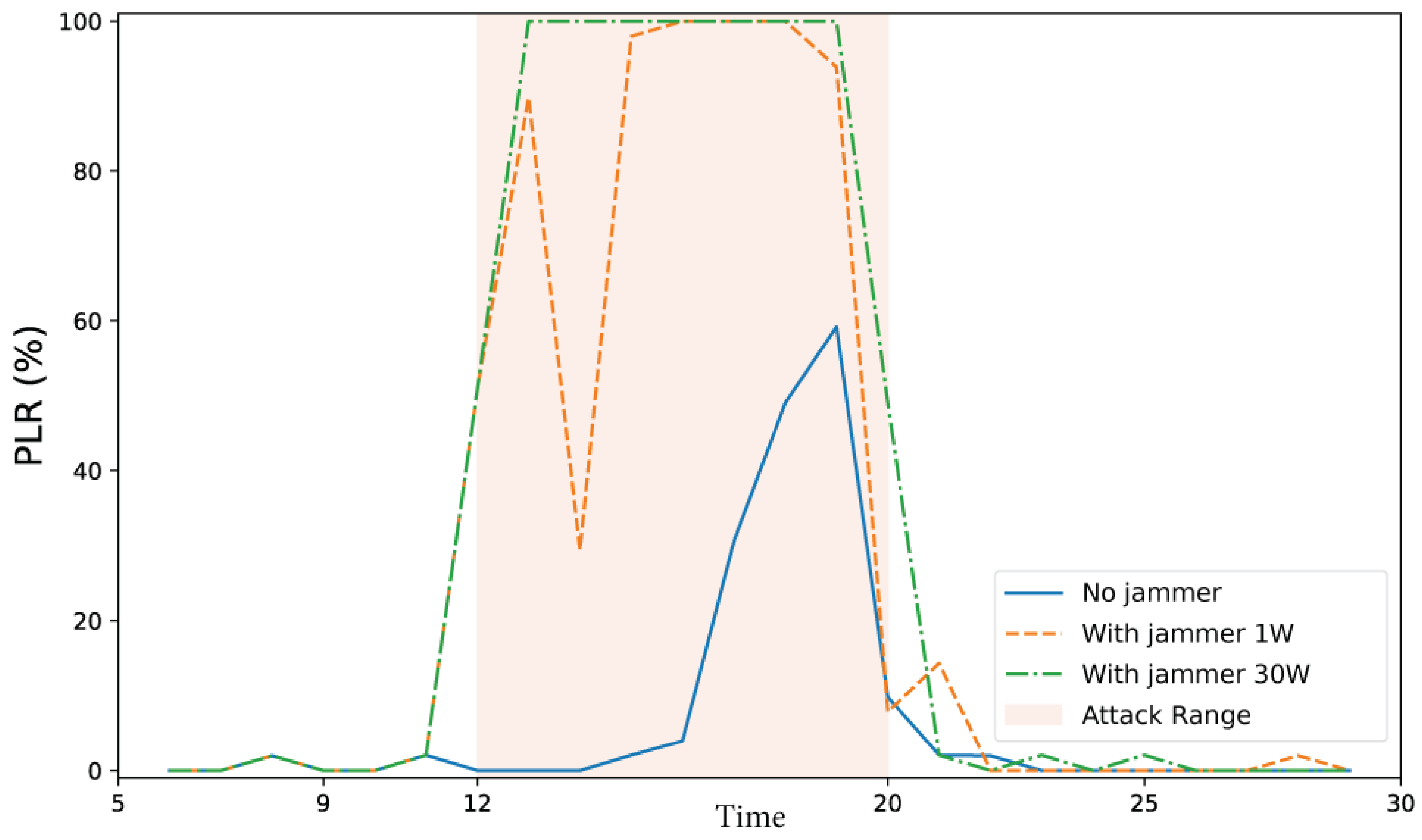

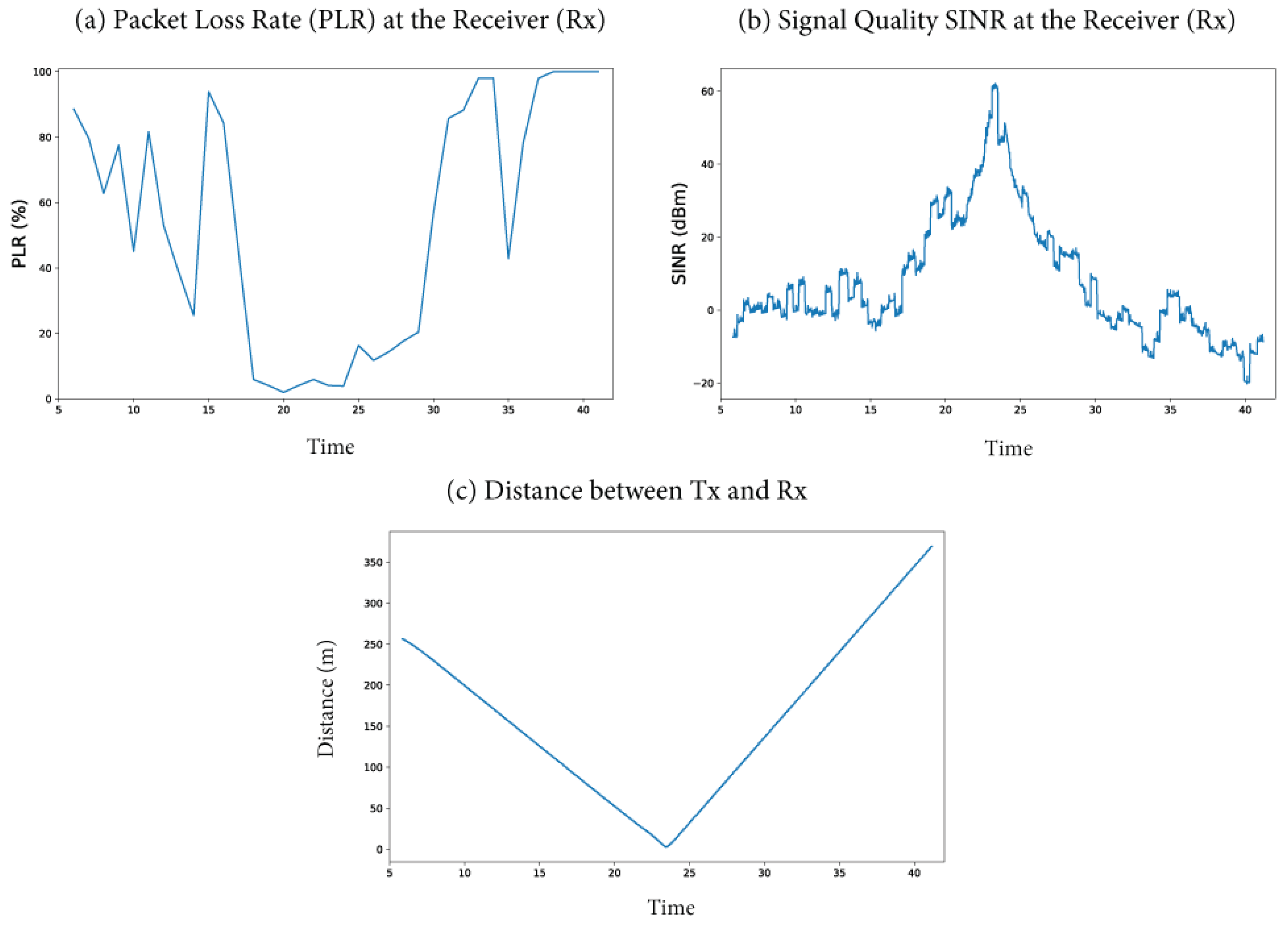

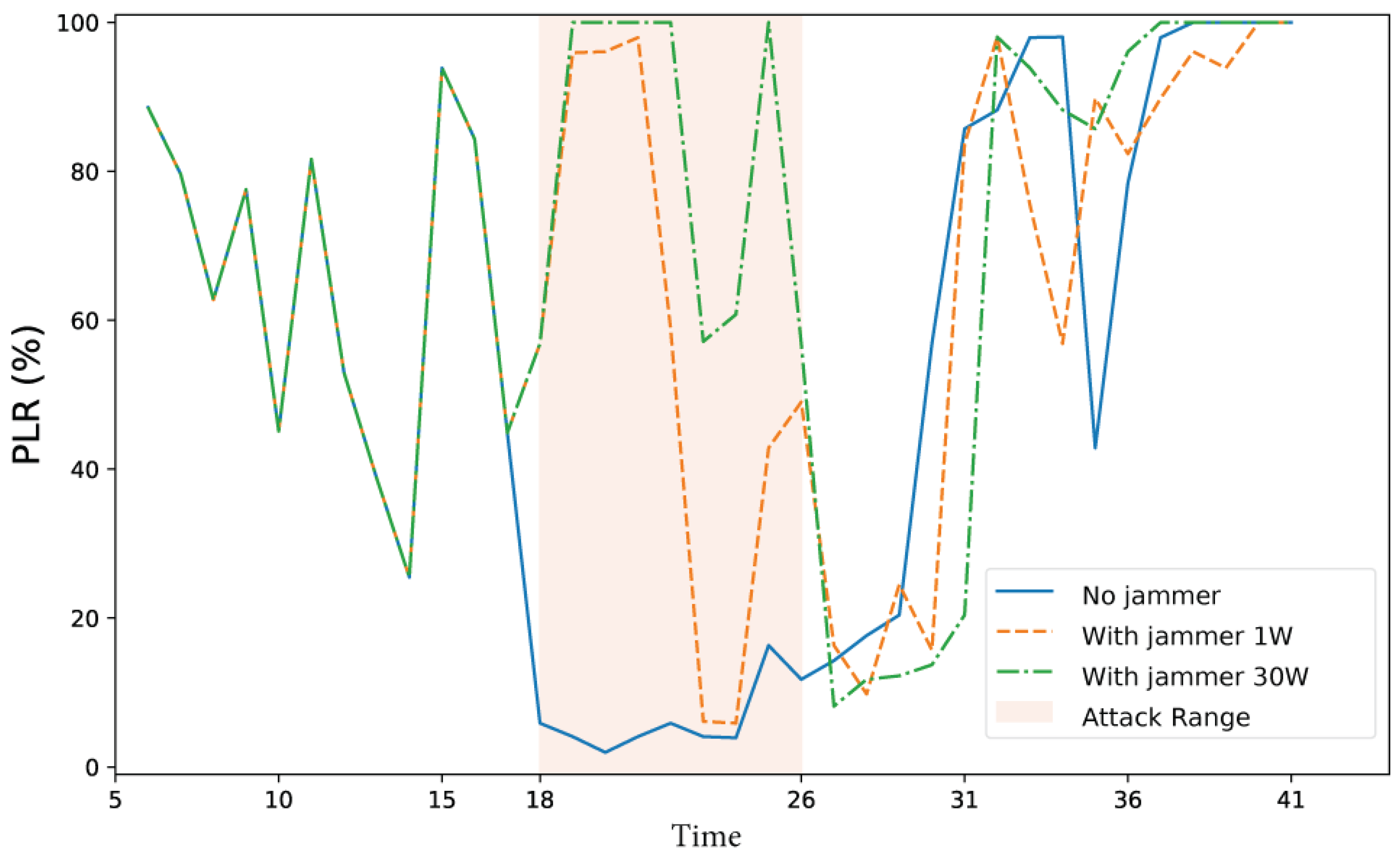

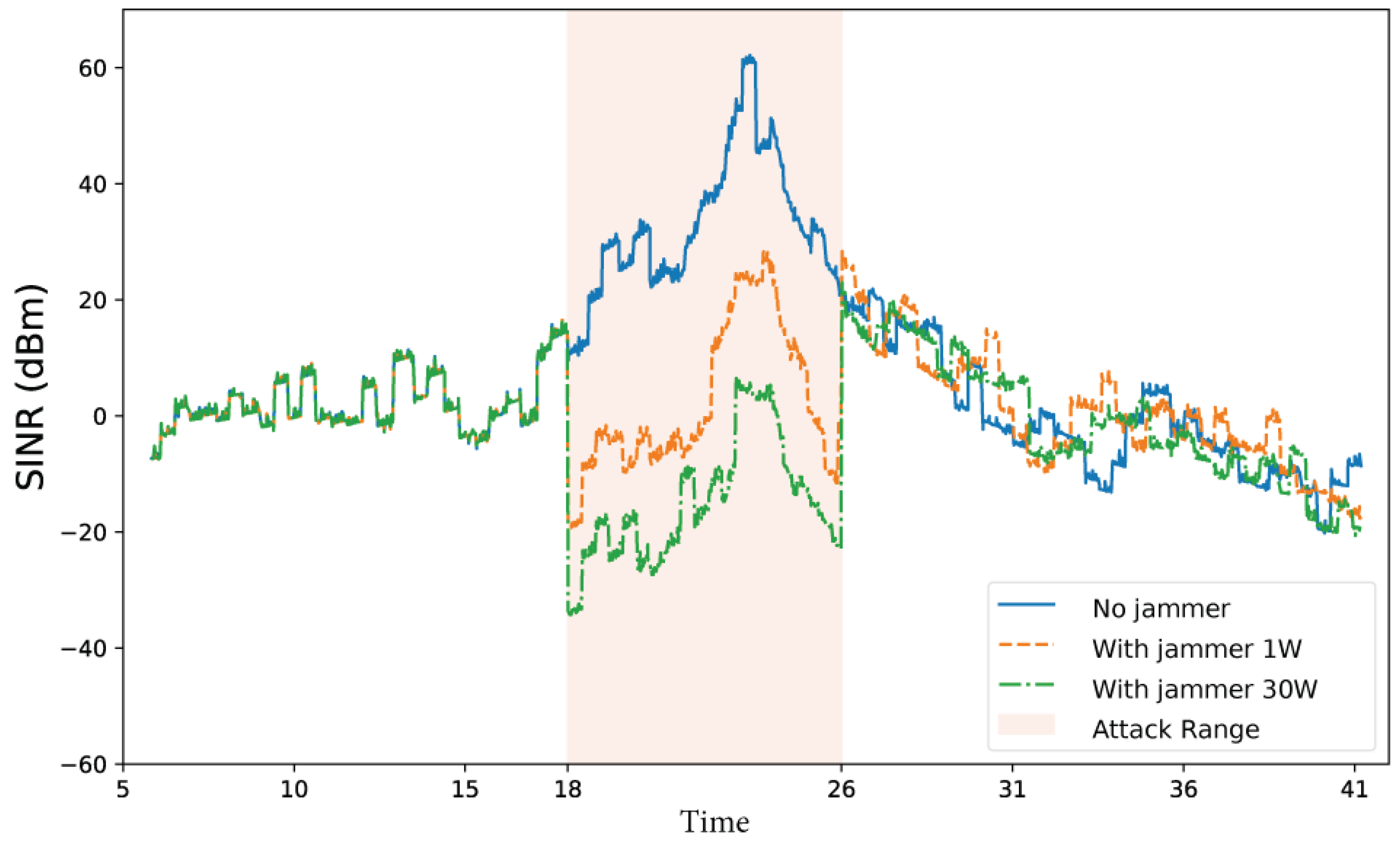

3.3.1. Simulation of the DNPW Scenario

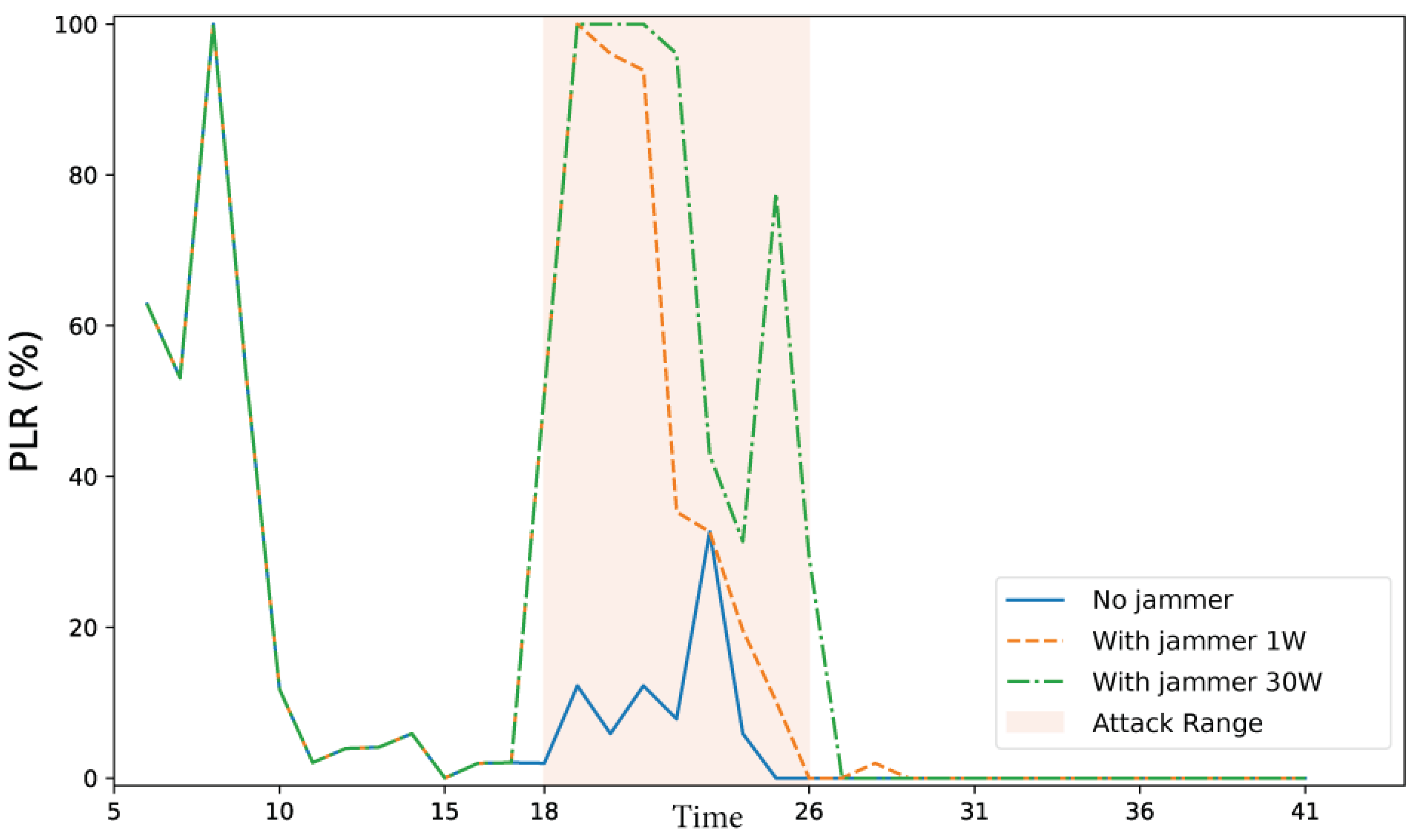

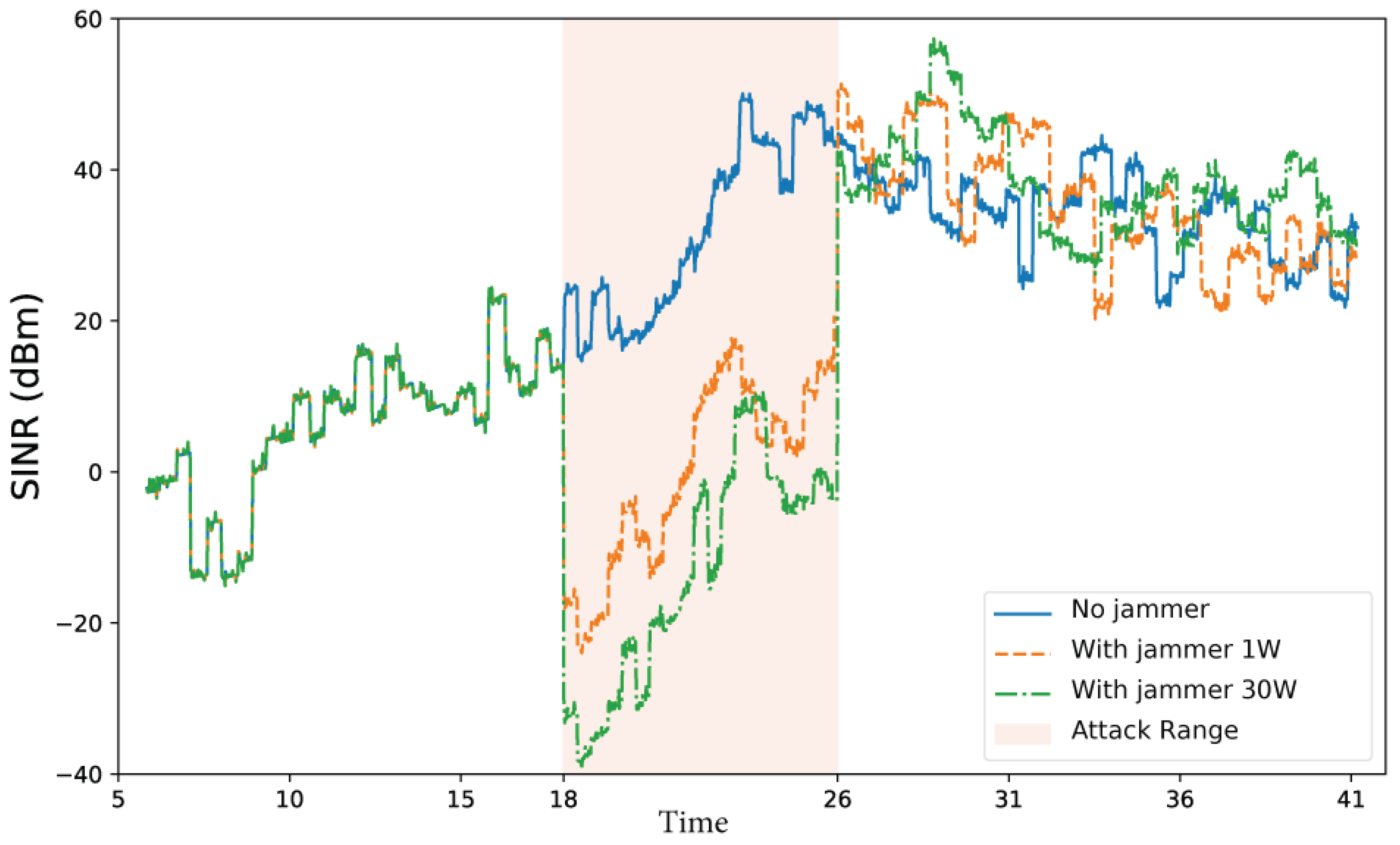

3.3.2. Parameters Analyzed in the DNPW Scenario

3.3.3. Parameters Affected by the Attack in the DNPW Scenario

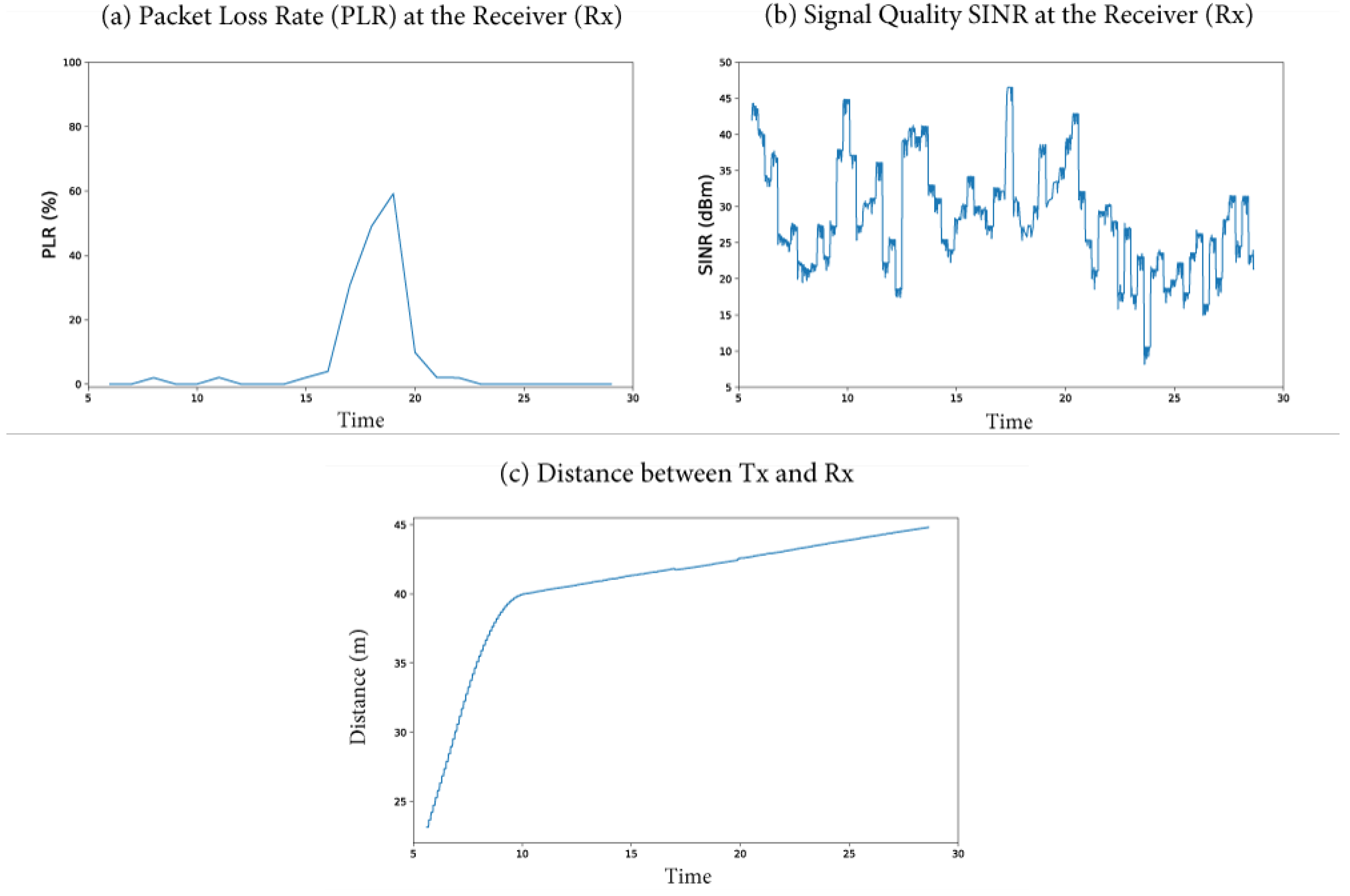

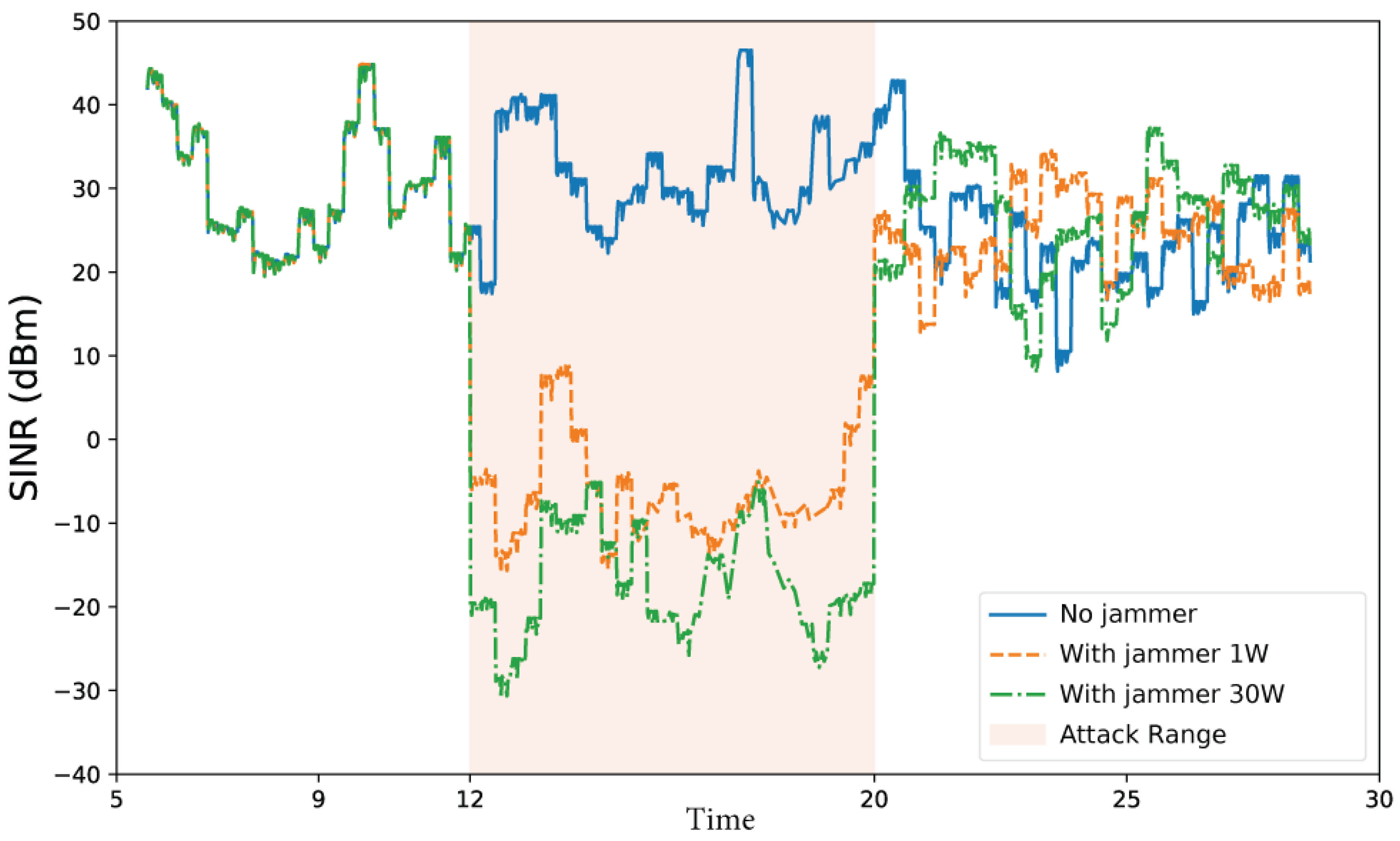

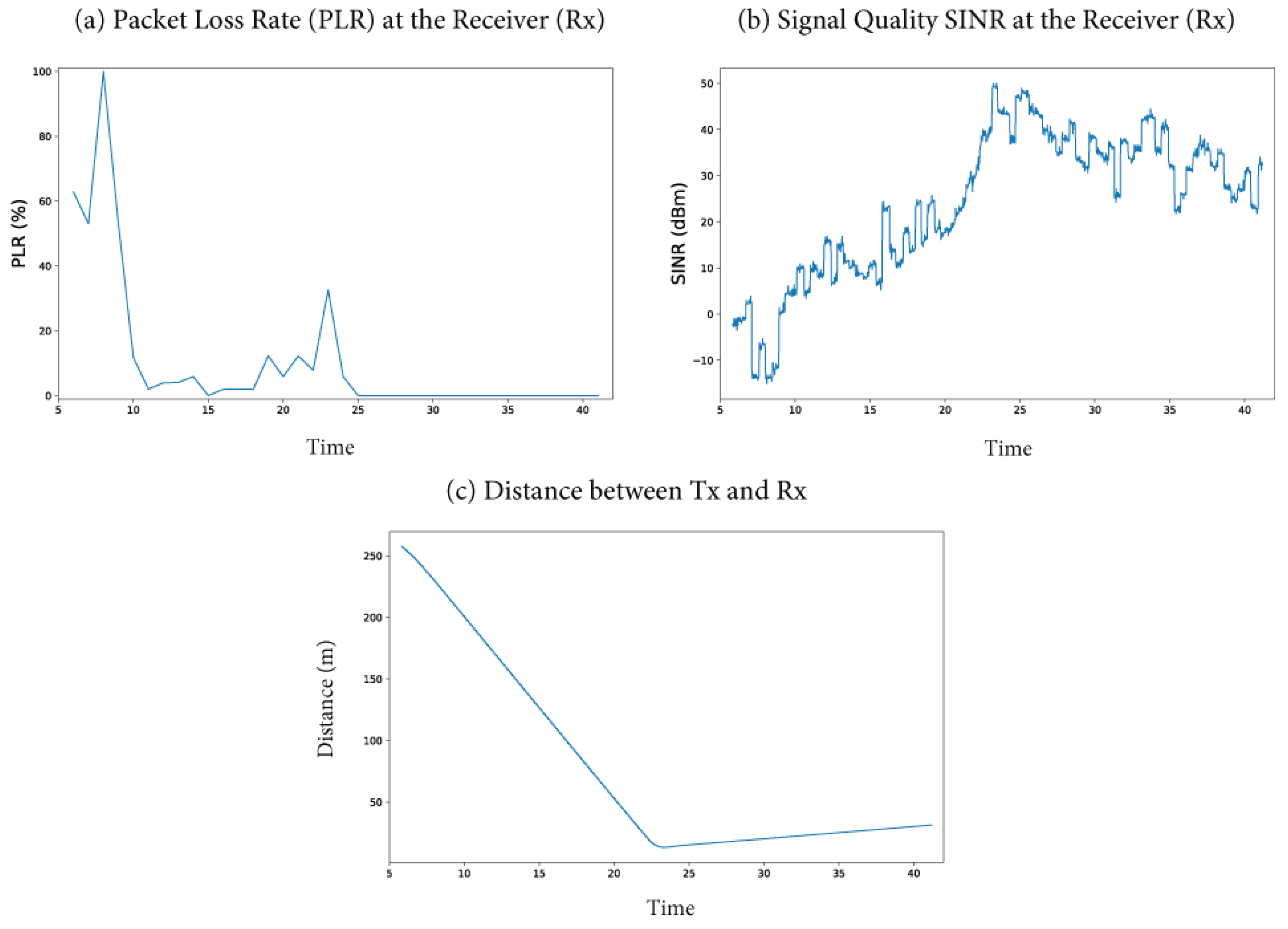

3.3.4. Simulation of the IMA Scenario

3.3.5. Parameters Analyzed in the IMA Scenario

3.3.6. Parameters Affected by the Attack in the IMA Scenario

4. Laboratory Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

4.1.1. Multi-Channel Transmitter and RF-Jamming Setup

- Data transmitters — One APVSG40-4 unit (10 MHz–40 GHz, four independent RF outputs each) was configured to transmit distinct, pre-encoded V2X-like data streams. All units were synchronized using a shared reference clock and trigger signal, ensuring channel phase coherence.

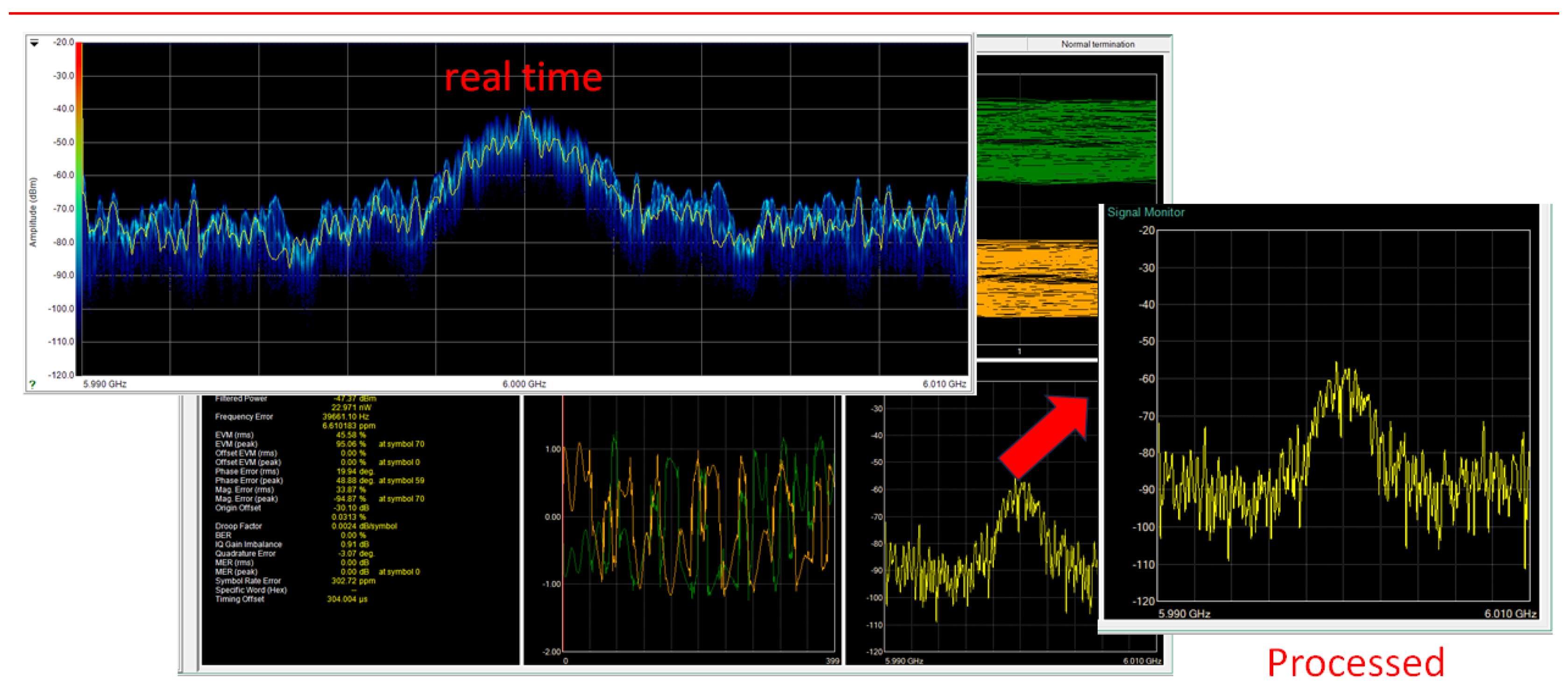

- Intentional jammer — A second generator (single-channel APVSG40, with red chassis) was used exclusively to emit controlled RF interference. During jamming trials, this unit injected wideband swept-frequency noise centered near the transmission band. Its output was routed to a spatially separated antenna positioned to interfere with line-of-sight reception.

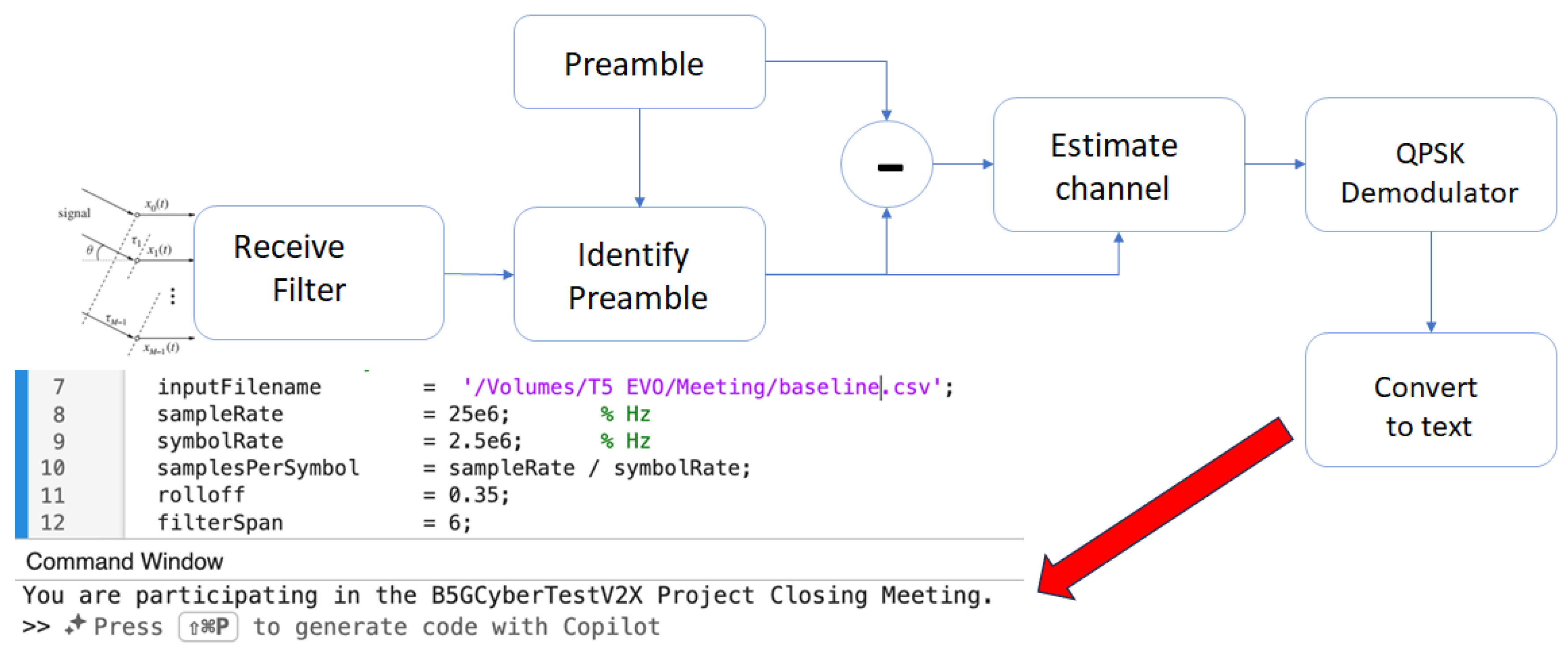

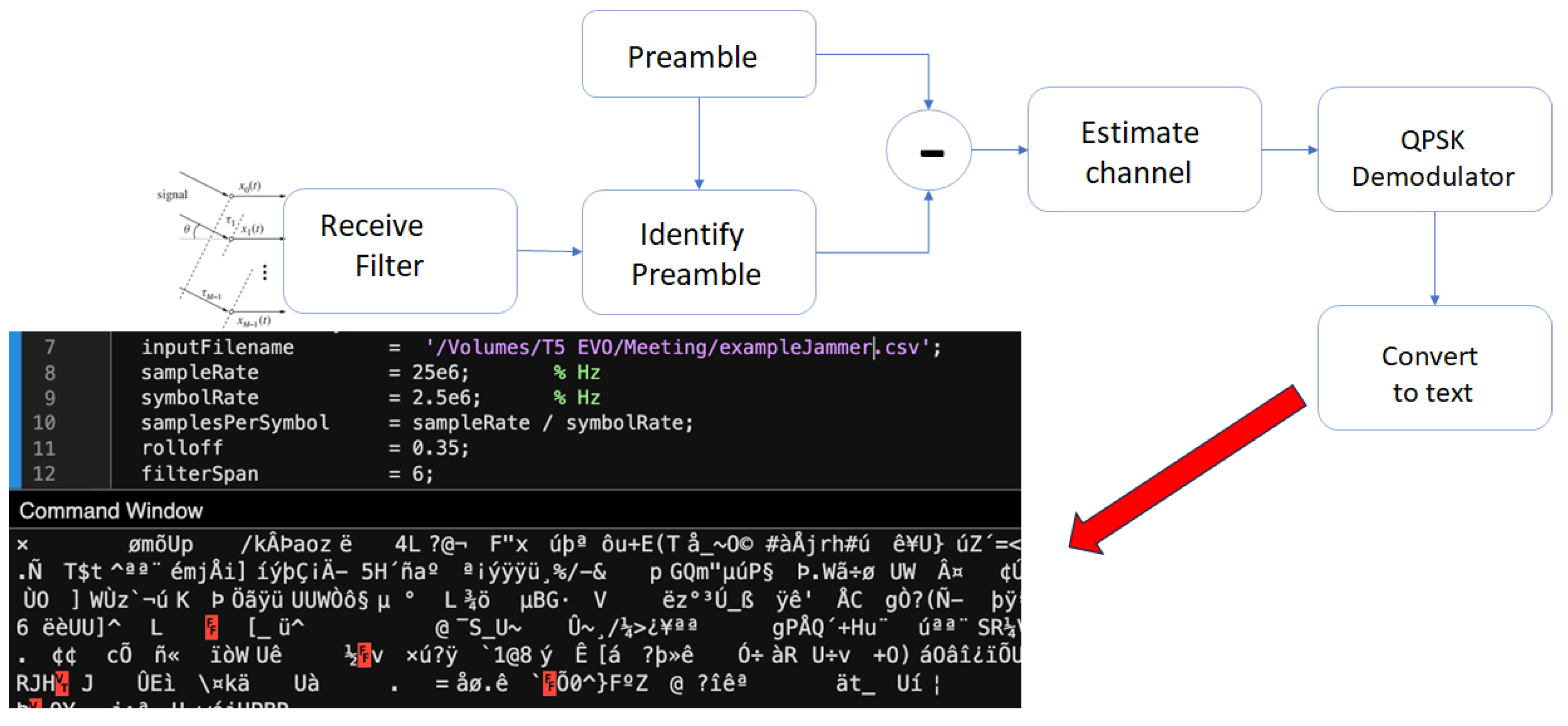

4.1.2. Receiver Array and Signal Decoding System

4.2. Experiment Scenarios

- Scenario 1 — Clean Transmission: Only the four data-bearing transmitters were active in this baseline configuration. Each signal was modulated and transmitted via its corresponding ERAVANT horn antenna without any intentional external disturbance. This scenario serves as a reference for ideal reception conditions.

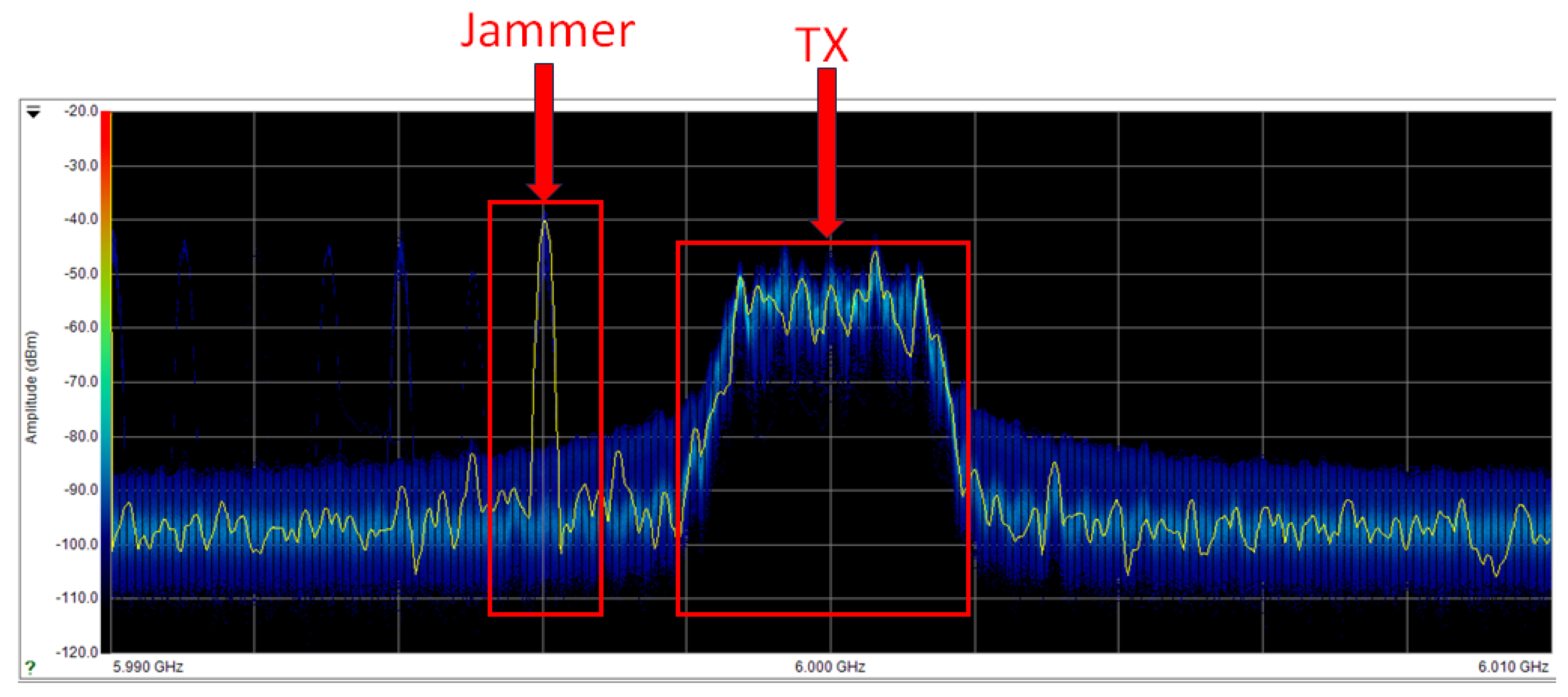

- Scenario 2 — Jamming Condition: In addition to the four transmitters, the jamming unit (described in Section 4.1.1) was activated. The interfering signal, emitted from a separate antenna with lateral offset, introduced controlled RF noise into the system. The jammer was active throughout the signal transmission and reception period.

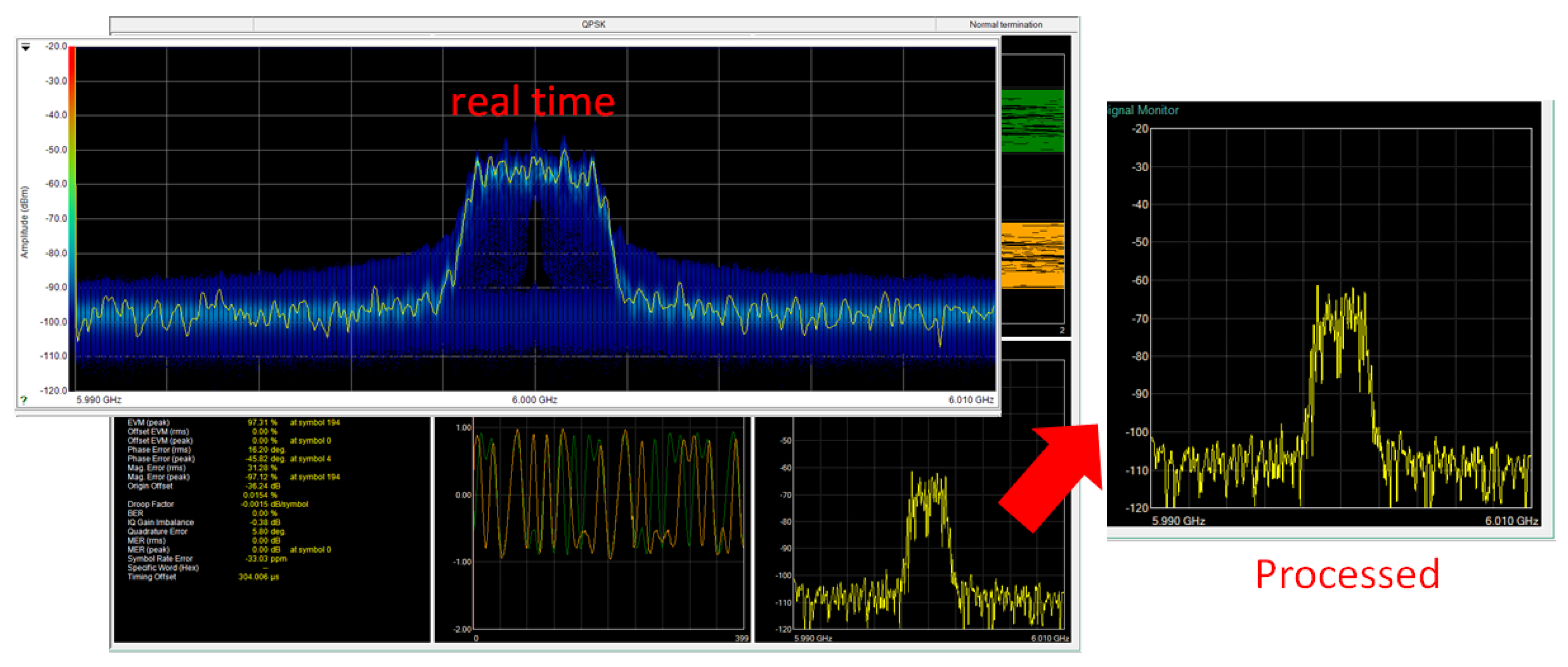

4.3. Experimental Results

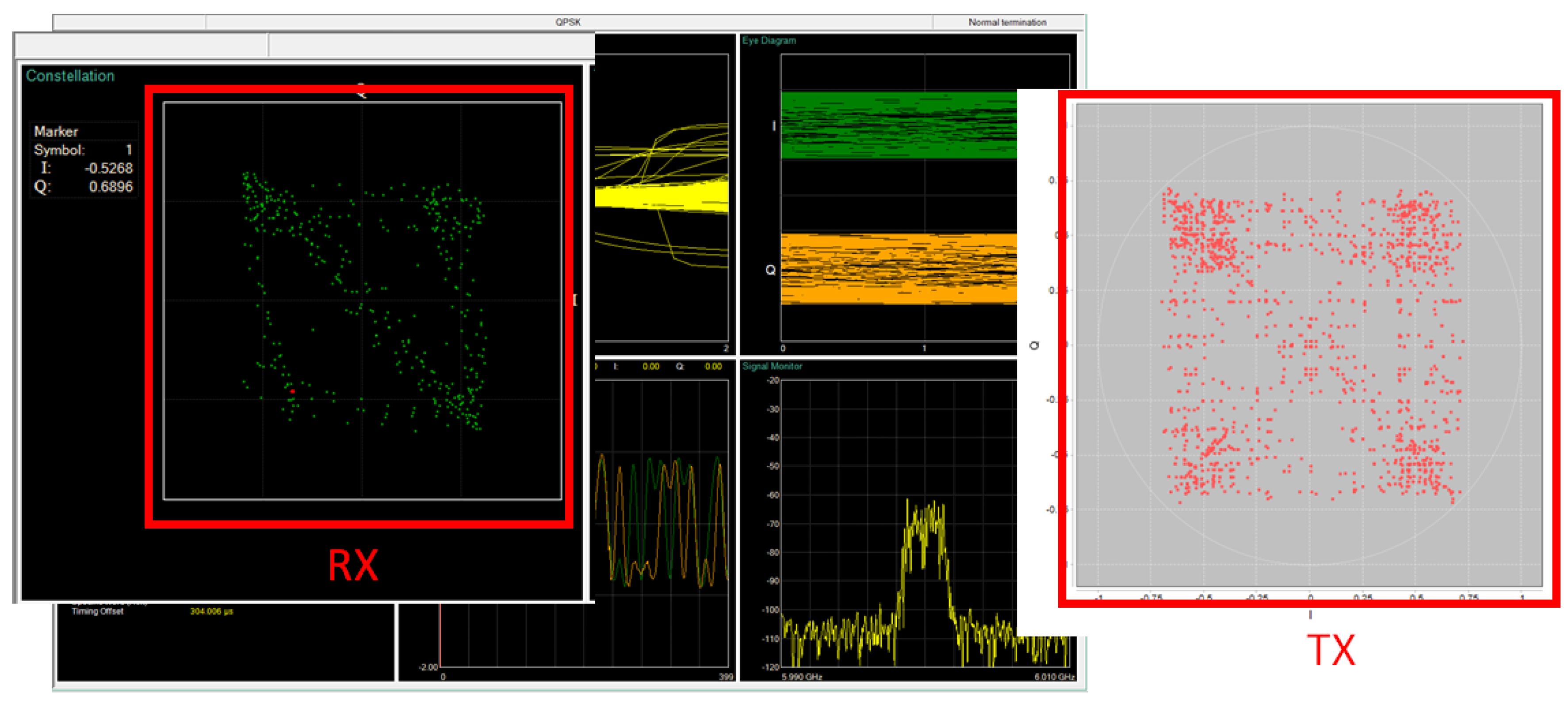

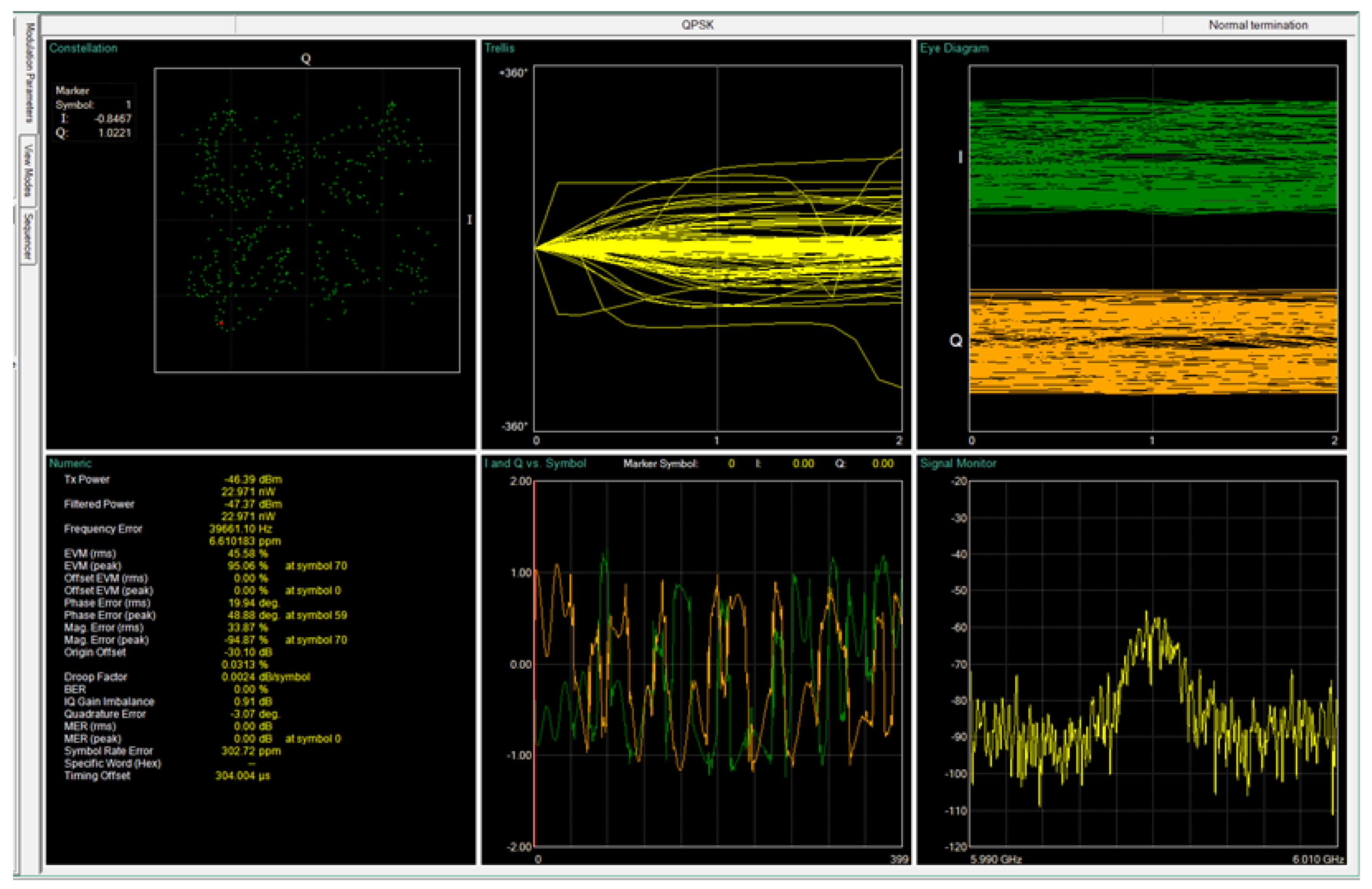

4.3.1. Baseline Case: Transmission Without Jamming

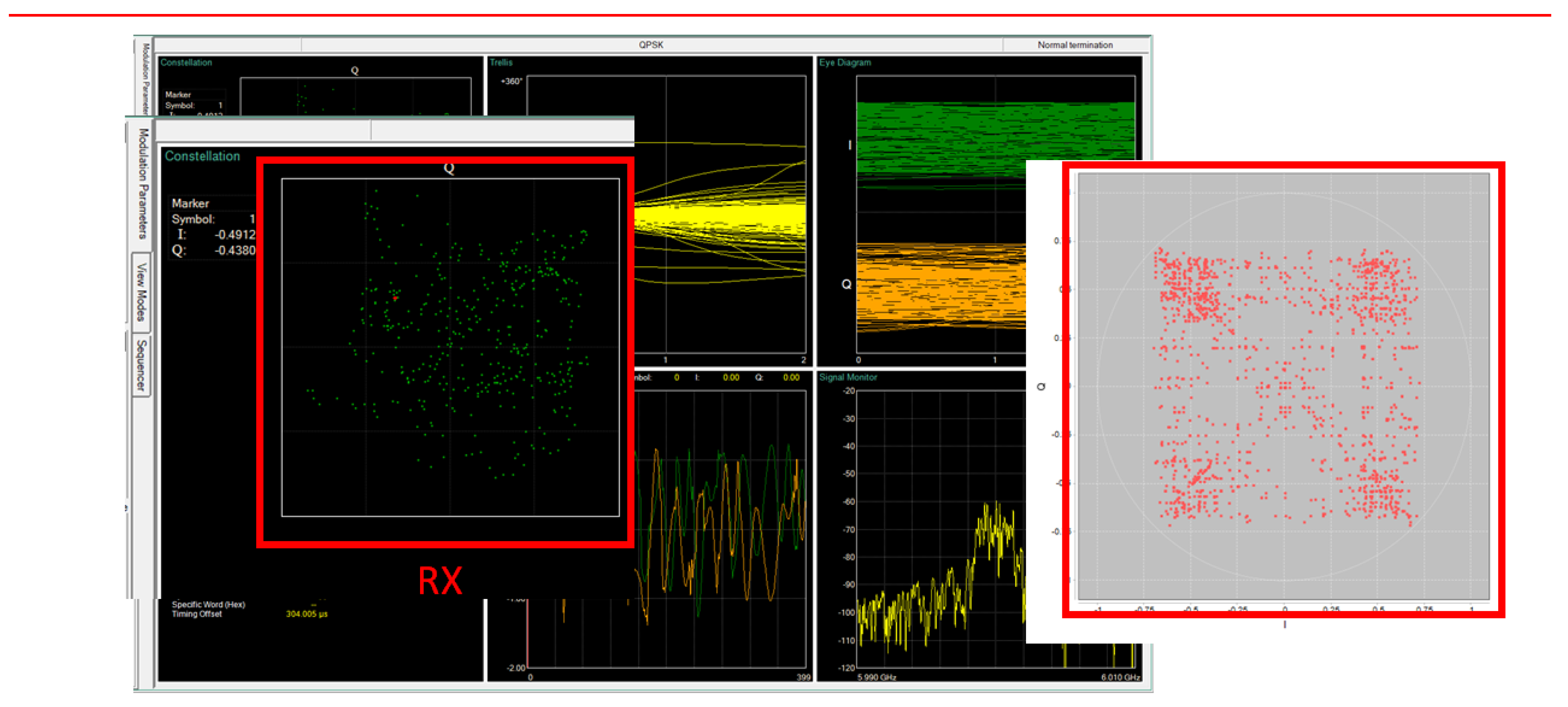

4.3.2. Jamming Case: Transmission with Intentional Interference

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 3GPP | 3rd Generation Partnership Project |

| ARES | Anti-jamming Reinforcement System |

| AVs | Autonomous vehicles |

| C-ITS | Cooperative Intelligent Transport System |

| C-V2X | Cellular Vehicle-to-Everything |

| CV | Connected Vehicle |

| DNPW | Do Not Pass Warning |

| DSRC | Dedicated Short-Range Communication |

| DQN | Deep Q-Networks |

| ETA | Estimated Time of Arrival |

| EVM | Error Vector Magnitude |

| FCC | Federal Communications Commission |

| FDD | Frequency Division Duplex |

| GDBNs | Generalized Dynamic Bayesian Networks |

| GNSS | Global Navigation Satellite System |

| GSHA | Graham Scan Hull Algorithm |

| I-SIG | Intelligent Signal |

| IMA | Intersection Movement Assist |

| IMU | Inertial Measurement Unit |

| ITS | Intelligent Transport Systems |

| MAC | Media Access Control |

| M-MJPF | Modified Markov Jump Particle Filter |

| MSF | Multi-Sensor Fusion |

| NR-V2X | New Radio V2X |

| RF | Radio Frequency |

| RSSI | Received Signal Strength Indicator |

| Rx | Receiver |

| SINR | Signal-to-Interference-plus-Noise Ratio |

| SPS | Semi-Persistent Scheduling |

| TDD | Time Division Duplex |

| TDOA | Time Difference of Arrival |

| TraCI | Traffic Control Interface |

| TSC | Traffic Signal Control |

| Tx | Transmitter |

| UE | User Equipment |

| UMa | Urban Macrocellular |

| UMiSC | Urban Microcellular Street Canyon |

| UMiOS | Urban Microcellular Open Square |

| V2I | Vehicle-to-Infrastructure |

| V2N | Vehicle-to-Network |

| V2P | Vehicle-to-Pedestrian |

| V2V | Vehicle-to-Vehicle |

| V2X | Vehicle-to-Everything |

| VSG | Vector Signal Generator |

Appendix A

Appendix A.1

- Constant jamming: These are attacks in which jamming devices emit powerful signals continuously, disrupting legitimate transmissions and occupying the channel.

- Reactive jamming: Known as channel-aware attacks, they are triggered by the detection of legitimate transmissions. They are efficient but require strict timing controls to operate.

- Deceptive jamming: Involves sending multiple radio signals to waste network resources, preventing legitimate access to the channel through saturation.

- Random jamming: The jamming device emits interference signals for random periods, saving energy compared to constant jamming attacks.

- Periodic jamming: The jamming device emits interference pulses in a predictable and regular manner. It can be more energy-efficient than random attacks if the duty cycle is efficiently controlled.

- Frequency sweeping jamming: Allows a jammer to quickly switch between multiple channels, targeting networks even with hardware limitations.

| Mechanism | Strengths | Weaknesses |

|---|---|---|

| Constant jamming | Highly effective | Energy inefficient |

| Reactive jamming | Highly effective | Hardware limitations |

| Deceptive jamming | Energy efficient | Less effective |

| Random jamming | Energy efficient | Less effective |

| Periodic jamming | Energy efficient | Less effective |

| Frequency sweeping jamming | Highly effective | Energy inefficient |

References

- Kato, S.; Takeuchi, E.; Ishiguro, Y.; Ninomiya, Y.; Takeda, K.; Hamada, T. An Open Approach to Autonomous Vehicles. IEEE Micro 2015, 35, 60–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, K. Public acceptance and perception of autonomous vehicles: a comprehensive review. AI and Ethics 2021, 1, 355–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alzalam, I.; Lipps, C.; Schotten, H.D. Time-Series Forecasting Models for 5G Mobile Networks: A Comparative Study in a Cloud Implementation. In Proceedings of the 2024 15th International Conference on Network of the Future (NoF), Castelldefels, Spain, October 2024; pp. 54–62. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seredynski, P. Autonomous vehicles and their cloud computing networks, 2021. Accessed on 2025-06-25.

- Tong, W.; Hussain, A.; Bo, W.X.; Maharjan, S. Artificial Intelligence for Vehicle-to-Everything: A Survey. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 10823–10843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munoz, Y.; Dai, W.; Mallikarjun, S.B.; Zentarra, M.; Lipps, C.; Schotten, H.D. Towards Smart Resource Distribution in V2X Dynamic Networks: A Modular RIS Approach. In Proceedings of the Mobilkommunikation; Osnabrück, Germany, May 2024, 28. ITG-Fachtagung; pp. 41–46.

- Hbaieb, A.; Rhaiem, O.B.; Chaari, L. In-car Gateway Architecture for Intra and Inter-vehicular Networks. In Proceedings of the 2018 14th International Wireless Communications &, Limassol, Cyprus, June 2018, Mobile Computing Conference (IWCMC); pp. 1489–1494. [CrossRef]

- Rüb, M.; Grüber, J.; Lipps, C.; Schotten, H.D. Update Rate and Dimension Requirements for Reconfigurable Mirror Arrays in Vehicular Visible Light Communication. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 99th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2024-Spring), Singapore, June 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guan, T.; Han, Y.; Kang, N.; Tang, N.; Chen, X.; Wang, S. An overview of vehicular cybersecurity for intelligent connected vehicles. Sustainability 2022, 14, 5211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nardini, G.; Sabella, D.; Stea, G.; Thakkar, P.; Virdis, A. Simu5G–An OMNeT++ Library for End-to-End Performance Evaluation of 5G Networks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 181176–181191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lima, D.V.; Da Silva, A.S.; Da Costa, J.P.J.; Santos, G.A.; Kastell, K.; De Alexandria, A.R.; Da Conceição, M.B. Framework for time-varying DoA estimation and beamforming against radio jamming in V2X applications. In Proceedings of the 2024 24th International Conference on Transparent Optical Networks (ICTON), Bari, Italy, July 2024; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Lima, D.V.; Da Costa, J.P.J.; Miranda, R.K.; Da Silva, A.A.S.; Santos, G.A.; Vargas, J.A.R.; De Alexandria, A.R. Low Complexity Broadband Array Processing in Dynamic Scenarios with Jamming. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 99th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2024-Spring), Singapore, June 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Lima, D.V.; da Costa, J.P.J.; da Silva, A.A.S.; Santos, G.A.; Vargas, J.A.R.; de Alexandria, A.R. Broadband Beamforming via Frequency Invariance Transformation and PARAFAC Decomposition for Jamming Mitigation in V2X Scenarios. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 99th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2024-Spring), Singapore, June 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, C.; Da Costa, J.P.J.; Dos Santos, G.A.; Munoz, Y.; Nozarian, F.; Vozniak, I.; Da Silva, A.S.; Heßler, A. Technical Report on Driving Use Cases for Highly Automated Driving and Key Performance Indicators. Technical report, Heßler,"Technical Report on Driving Use Cases for Highly Automated Driving and Key Performance Indicators", 2023.

- Yang, X.; Shi, Y.; Xing, J.; Liu, Z. Autonomous driving under V2X environment: state-of-the-art survey and challenges. Intelligent Transportation Infrastructure 2022, 1, liac020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harounabadi, M.; Soleymani, D.M.; Bhadauria, S.; Leyh, M.; Roth-Mandutz, E. V2X in 3GPP Standardization: NR Sidelink in Release-16 and Beyond. IEEE Communications Standards Magazine 2021, 5, 12–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, D.; Delgrossi, L. IEEE 802. In 11p: Towards an International Standard for Wireless Access in Vehicular Environments. In Proceedings of the VTC Spring 2008 - IEEE Vehicular Technology Conference, Marina Bay, Singapore, May 2008; pp. 2036–2040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Hu, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhao, L.; Li, W. A Vision of C-V2X: Technologies, Field Testing, and Challenges With Chinese Development. IEEE Internet of Things Journal 2020, 7, 3872–3881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Hu, J.; Shi, Y.; Peng, Y.; Fang, J.; Zhao, R.; Zhao, L. Vehicle-to-Everything (v2x) Services Supported by LTE-Based Systems and 5G. IEEE Communications Standards Magazine 2017, 1, 70–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Da Silva, A.S.; Da Costa, J.P.J.; Santos, G.A.; Miri, Z.; Fauzi, M.I.B.M.; Vinel, A.; de Freitas, E.P.; Kastell, K. Radio Jamming in Vehicle-to-Everything Communication Systems: Threats and Countermeasures. In Proceedings of the 2023 23rd International Conference on Transparent Optical Networks (ICTON), Bucharest, Romania, July 2023; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman Muraro Gularte, K.; Alfredo Ruiz Vargas, J.; Paulo Javidi da Costa, J.; Santos da Silva, A.; Almeida Santos, G.; Wang, Y.; Alfons Müller, C.; Lipps, C.; Timóteo de Sousa Júnior, R.; de Britto Vidal Filho, W.; et al. Safeguarding the V2X Pathways: Exploring the Cybersecurity Landscape Through Systematic Review. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 72871–72895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, G.A.; da Costa, J.P.J.; da Silva, A.A.S. Towards to Beyond 5G Virtual Environment for Cybersecurity Testing in V2X Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 Workshop on Communication Networks and Power Systems (WCNPS), Brasília, Brazil, November-December 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herman Muraro Gularte, K.; Paulo Javidi da Costa, J.; Vargas, J.A.R.; Santos da Silva, A.; Almeida Santos, G.; Wang, Y.; Alfons Müller, C.; Lipps, C.; Timóteo de Sousa, R.; de Britto Vidal Filho, W.; et al. Integrating Cybersecurity in V2X: A Review of Simulation Environments. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 177946–177985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhao, J.; Li, Z.; Cheng, X.; Wu, L. Jamming and Eavesdropping Defense Scheme Based on Deep Reinforcement Learning in Autonomous Vehicle Networks. IEEE Transactions on Information Forensics and Security 2023, 18, 1211–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pelechrinis, K.; Broustis, I.; Krishnamurthy, S.V.; Gkantsidis, C. A Measurement-Driven Anti-Jamming System for 802.11 Networks. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Networking 2011, 19, 1208–1222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krayani, A.; William, N.J.; Marcenaro, L.; Regazzoni, C. Jammer Detection in Vehicular V2X Networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 Microwave Mediterranean Symposium (MMS), Pizzo Calabro, Italy, May 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alam, M.S.; Oluoch, J.; Kim, J. A Mechanism to Localize, Detect, and Prevent Jamming in Connected and Autonomous Vehicles (CAVs). IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2023, 25, 1215–1224. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Twardokus, G.; Rahbari, H. Toward Protecting 5G Sidelink Scheduling in C-V2X Against Intelligent DoS Attacks. IEEE Transactions on Wireless Communications 2023, 22, 7273–7286. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.; Ju, Y.; Liu, L.; Pei, Q.; Yu, K.; Rodrigues, J.J.P.C. Secure mmWave C-V2X Communications Using Cooperative Jamming. In Proceedings of the GLOBECOM 2022 - 2022 IEEE Global Communications Conference, Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, December 2022; pp. 2686–2691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wyglinski, A.M.; Wickramarathne, T.; Chen, D.; Kirsch, N.J.; Gill, K.S.; Jain, T.; Garg, V.; Li, T.; Paul, S.; Xi, Z. Phantom Car Attack Detection via Passive Opportunistic RF Localization. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 27676–27692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Huang, S.E.; Wong, W.; Chen, Q.A.; Mao, Z.M.; Liu, H.X. On the Cybersecurity of Traffic Signal Control System With Connected Vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2022, 23, 16267–16279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, J.; Wan, Z.; Luo, Y.; Feng, Y.; Mao, Z.M.; Chen, Q.A. Detecting Data Spoofing in Connected Vehicle based Intelligent Traffic Signal Control using Infrastructure-Side Sensors and Traffic Invariants. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Anchorage, AK, USA, June 2023; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Ying, J.; Shen, J.; Feng, Y.; Chen, Q.A.; Mao, Z.M.; Liu, H.X. Anomaly Detection Against GPS Spoofing Attacks on Connected and Autonomous Vehicles Using Learning From Demonstration. IEEE Transactions on Intelligent Transportation Systems 2023, 24, 9462–9475. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pusapati, S.; Selim, B.; Nie, Y.; Lin, H.; Peng, W. Simulation of NR-V2X in a 5G Environment using OMNeT++. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE Future Networks World Forum (FNWF), Montreal, QC, Canada, October 2022; pp. 634–638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pirayesh, H.; Zeng, H. Jamming Attacks and Anti-Jamming Strategies in Wireless Networks: A Comprehensive Survey. IEEE Communications Surveys & Tutorials 2022, 24, 767–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).