Submitted:

10 September 2025

Posted:

11 September 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

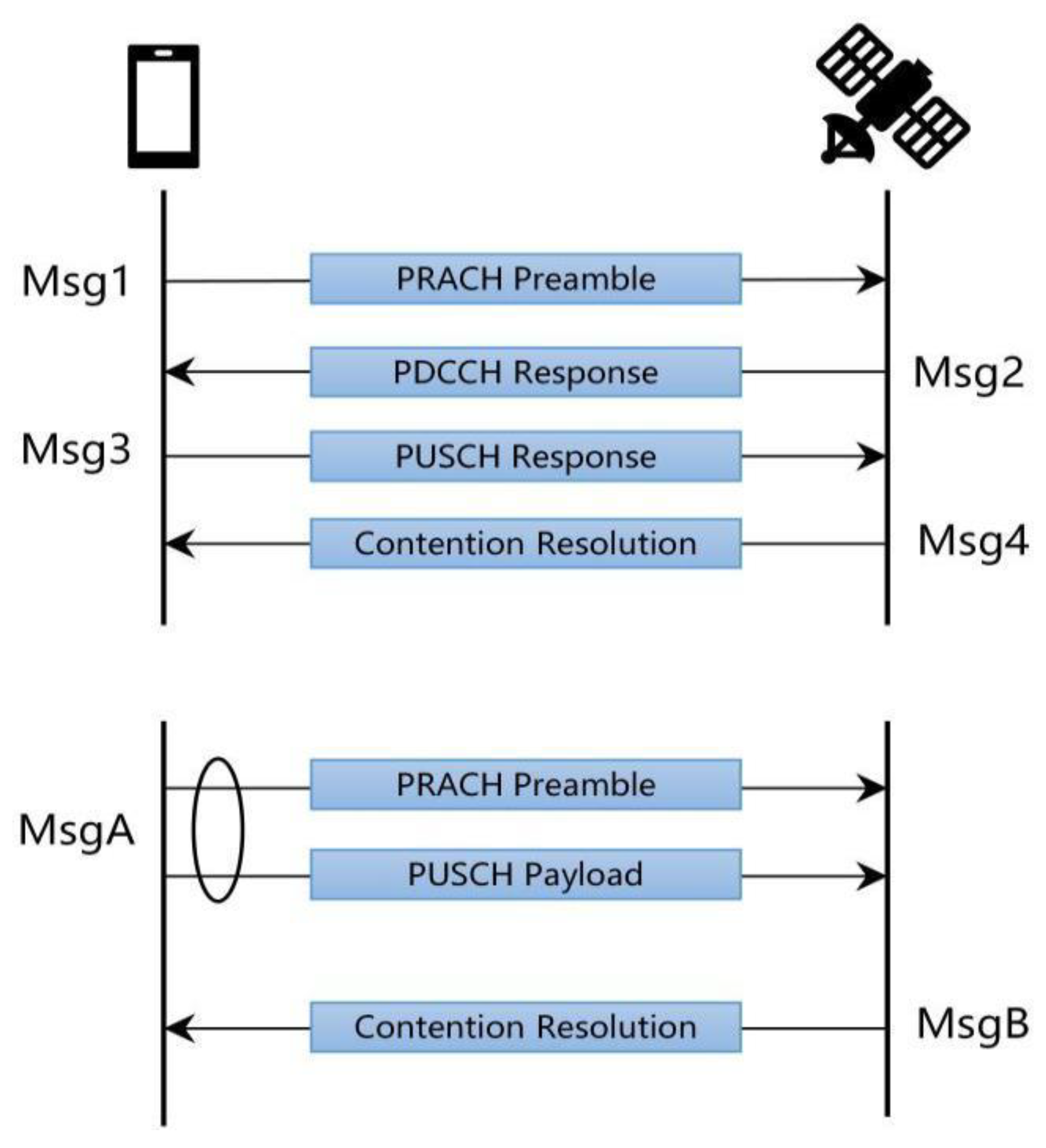

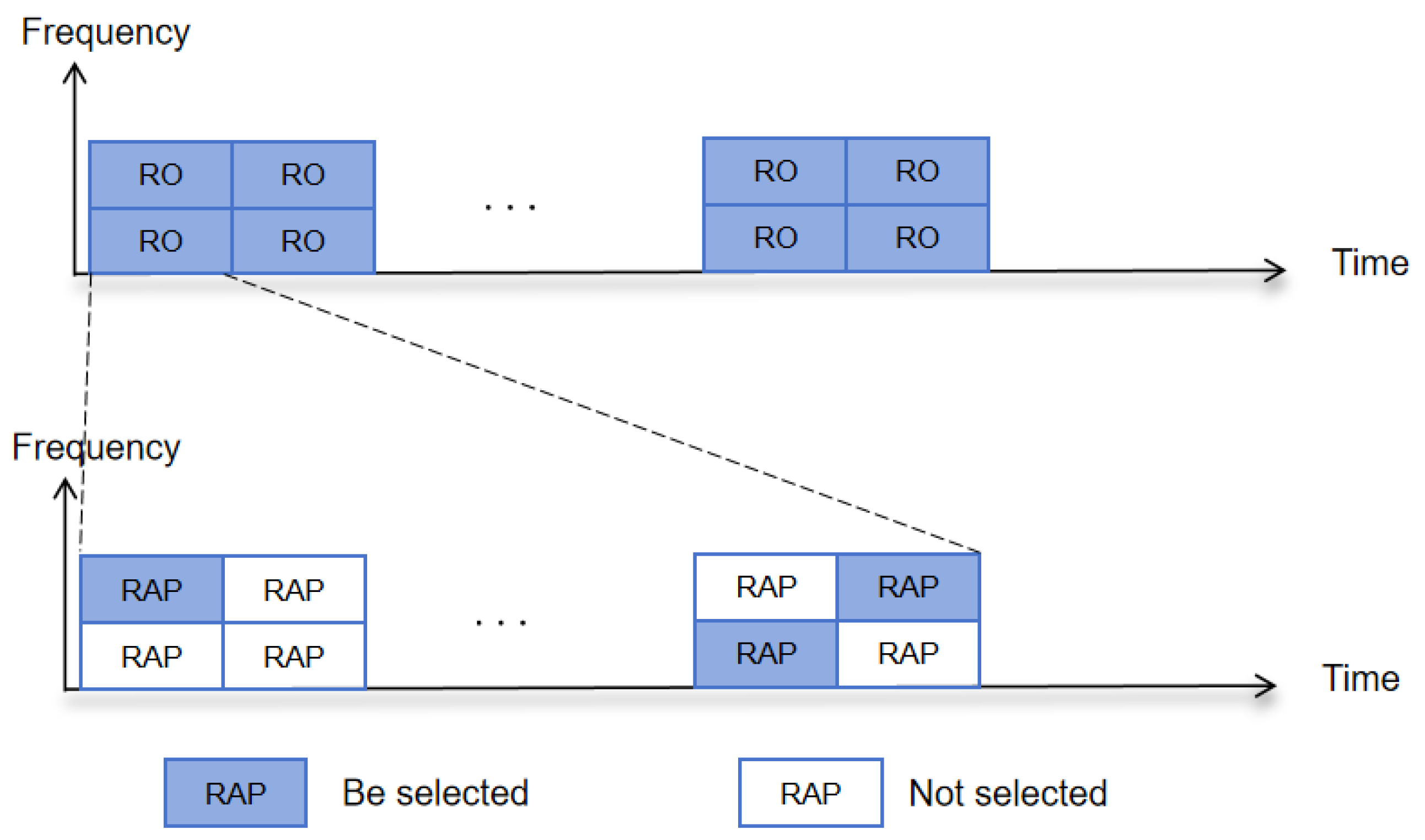

2.1. Random Access Procedure

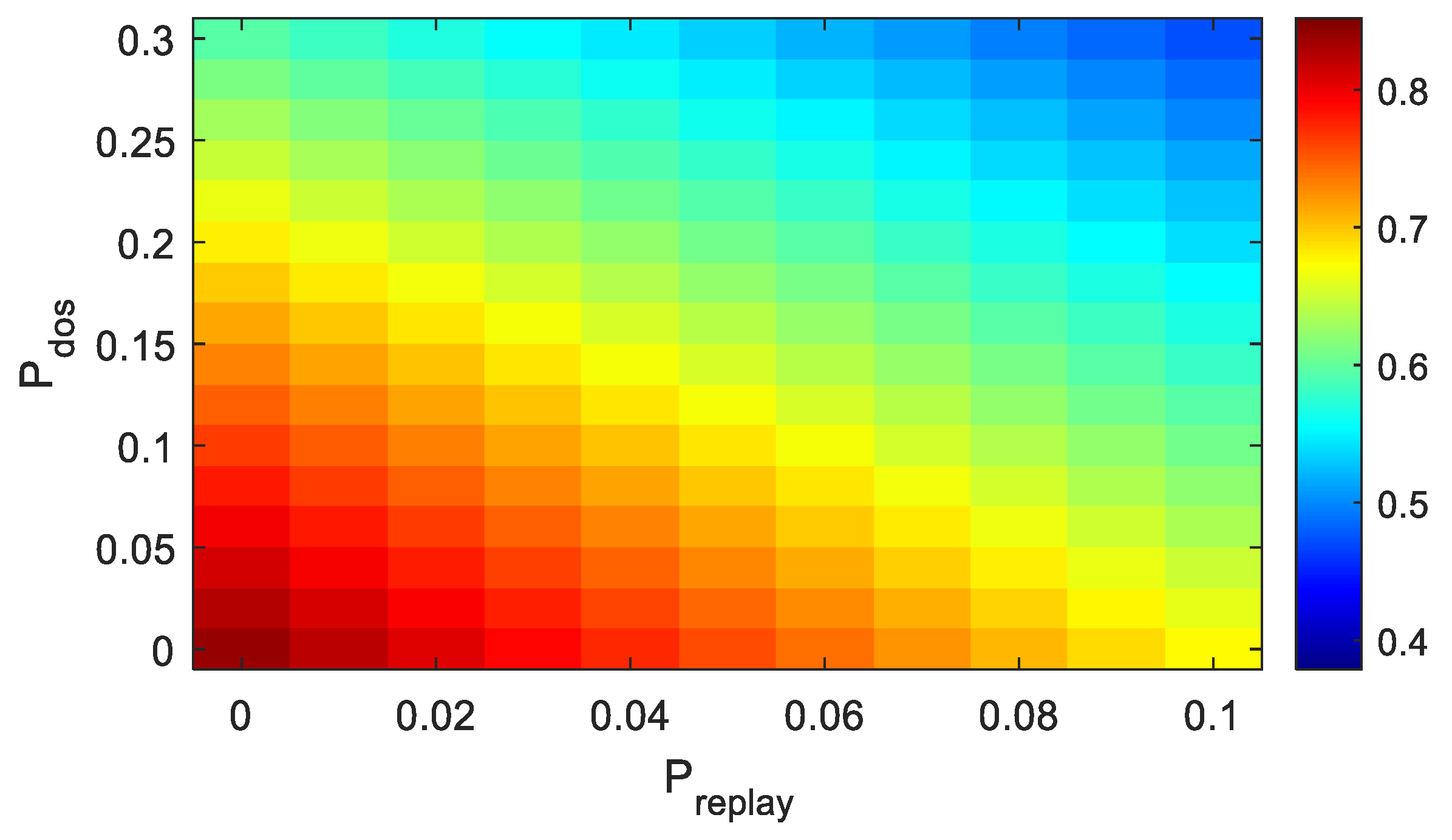

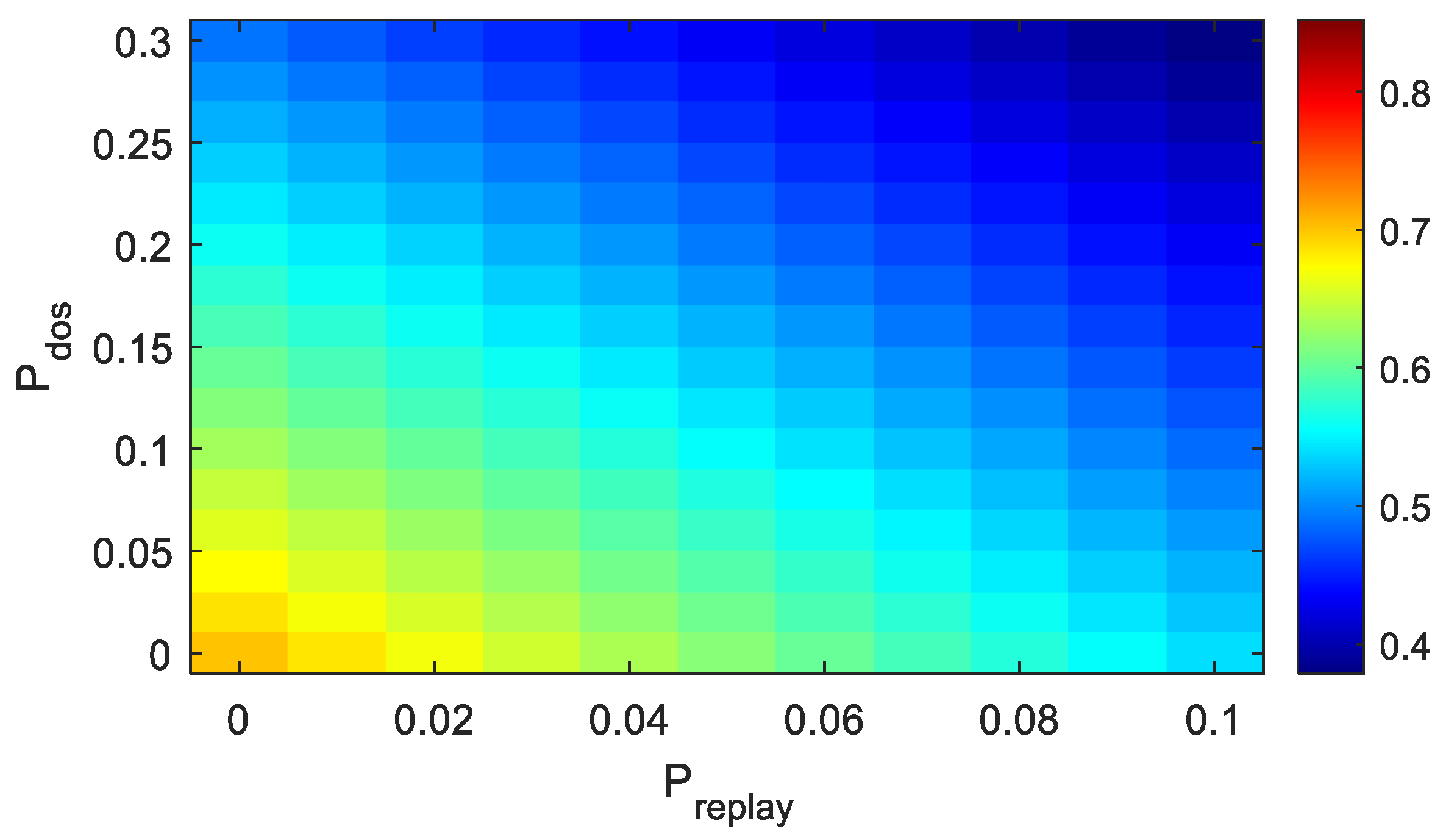

2.2. DoS and Replay Attacks

3. Attack-Aware Adaptive Backoff Indicator (AA-BI)

4. Performance Evaluation and Simulation Analysis

4.1. Simulation Environment and Parameter Design

4.2. Evaluation Metrics

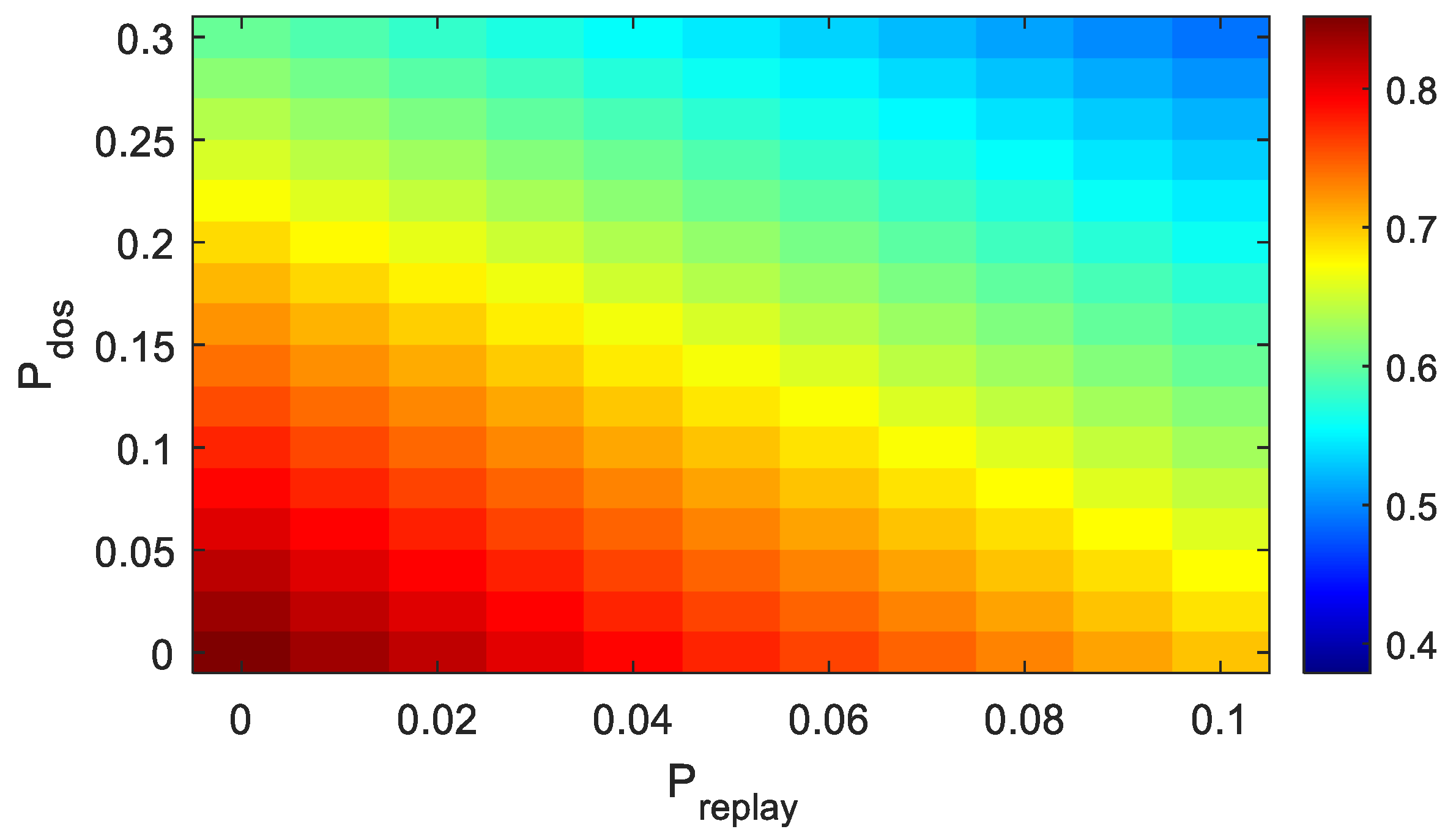

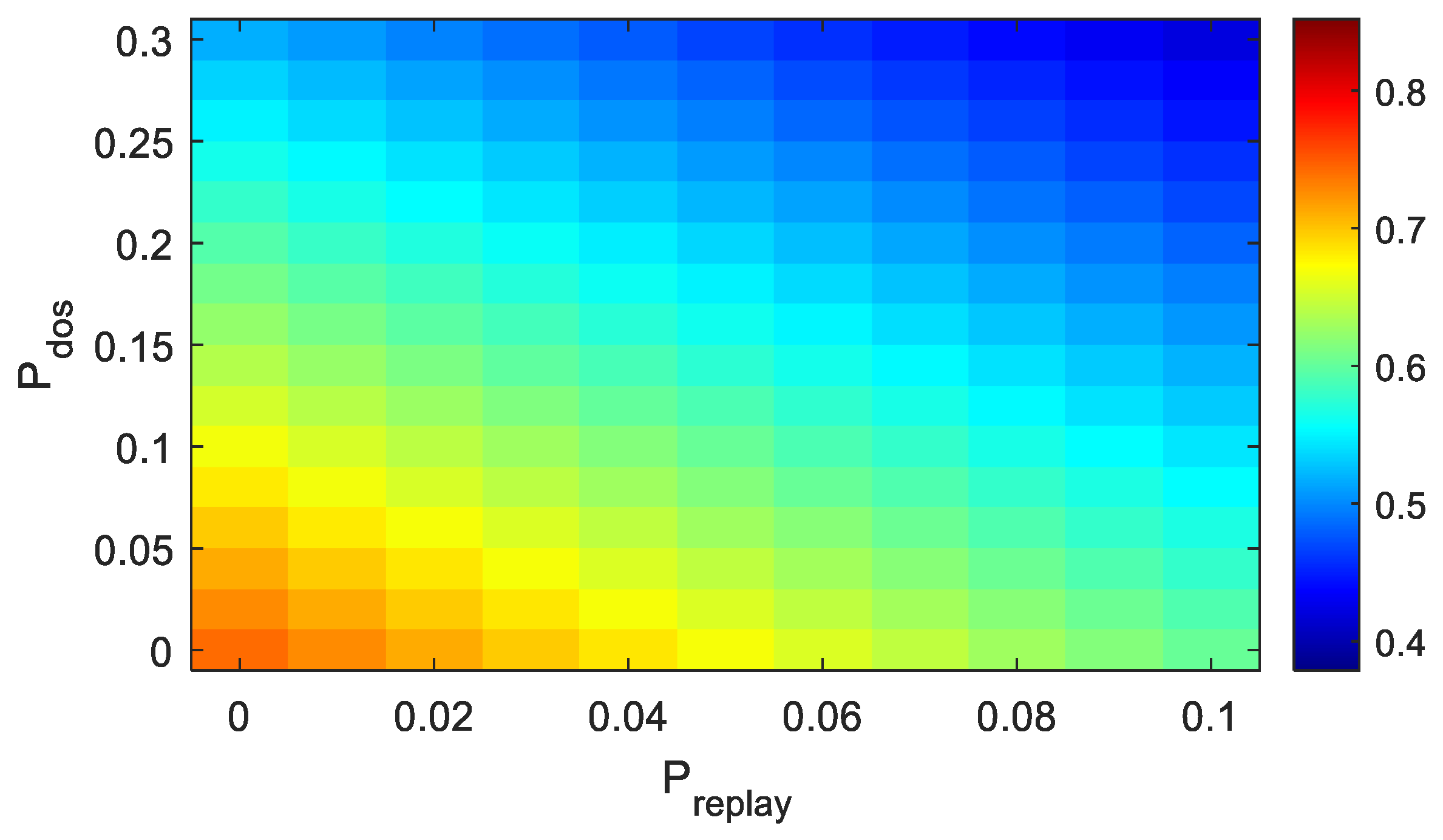

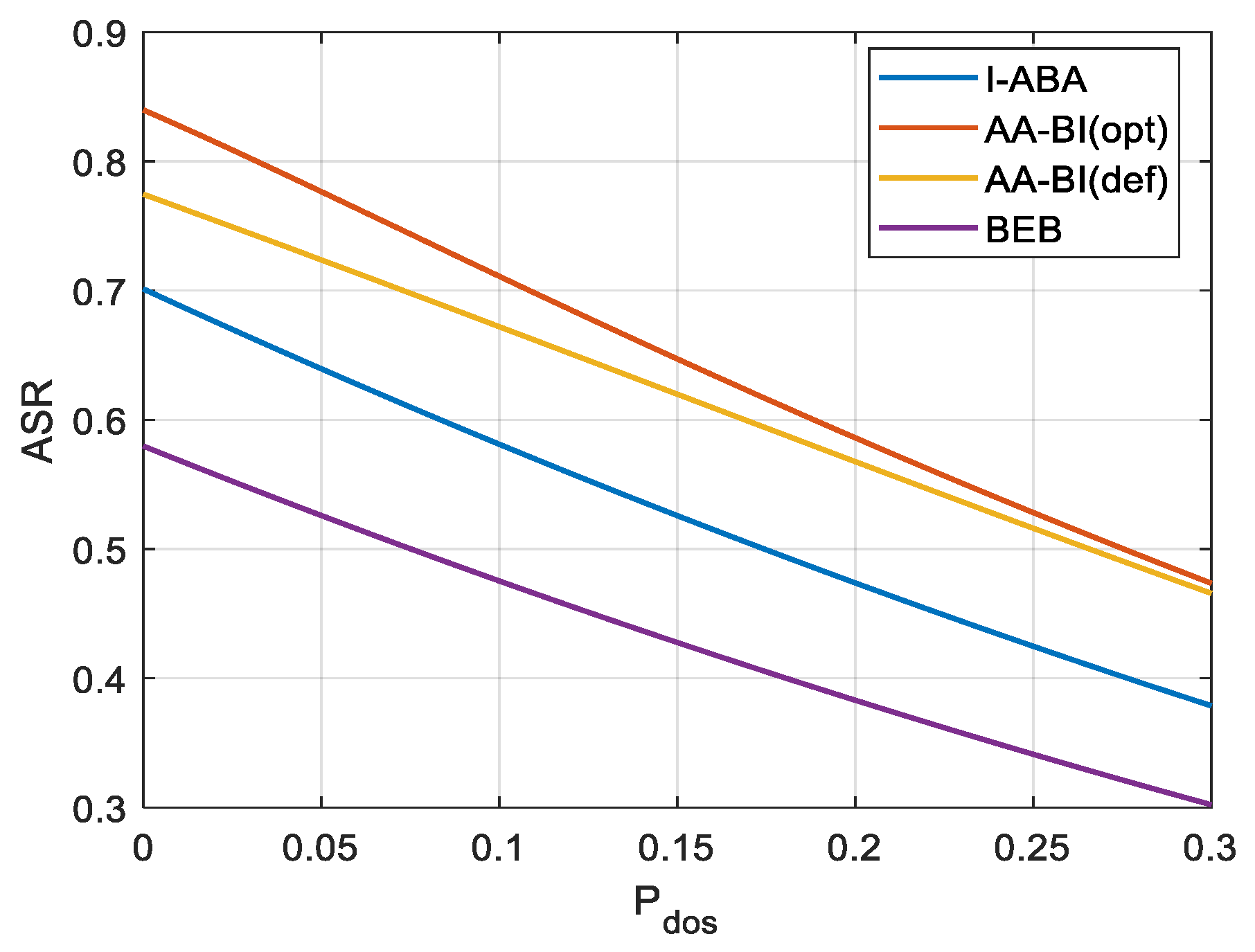

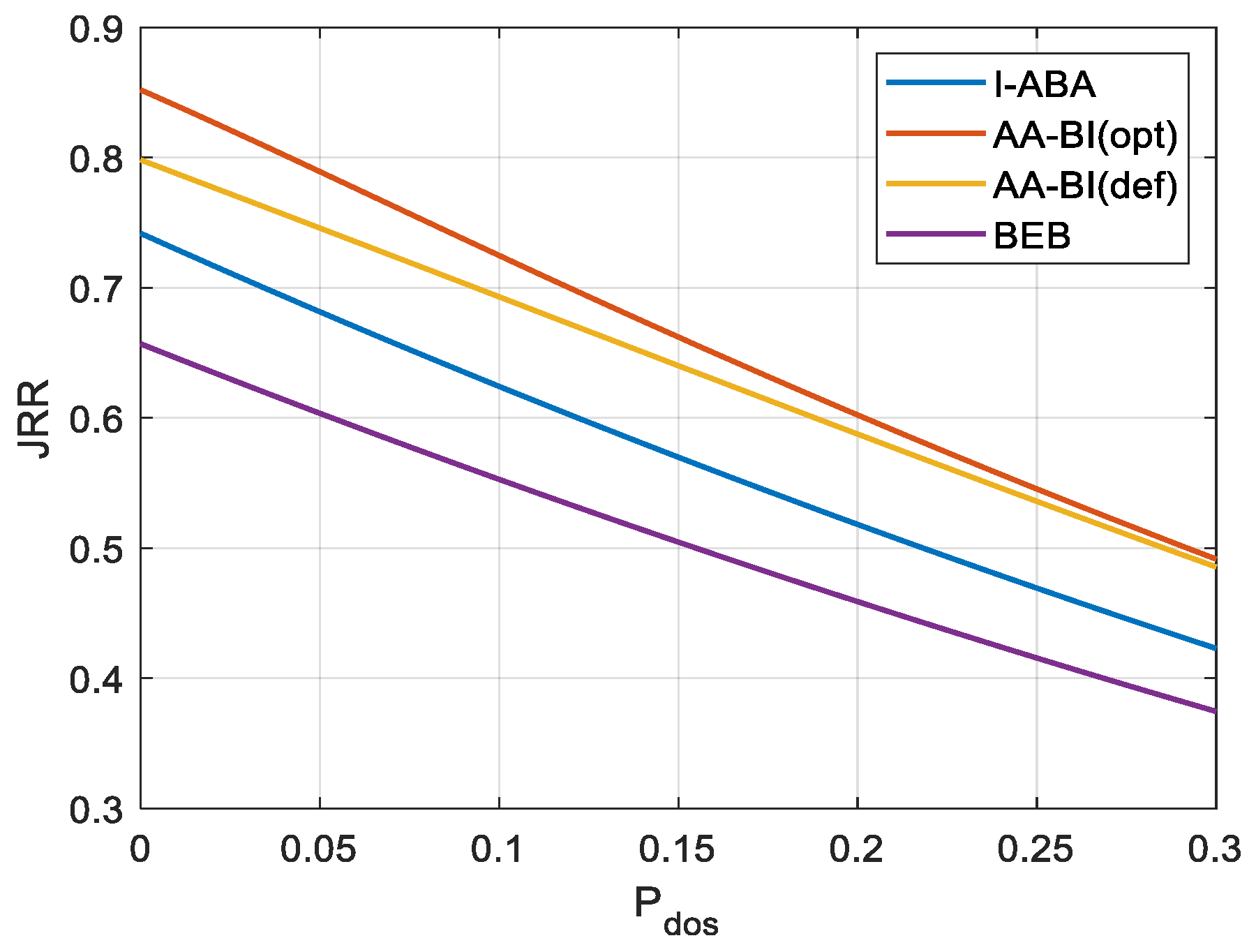

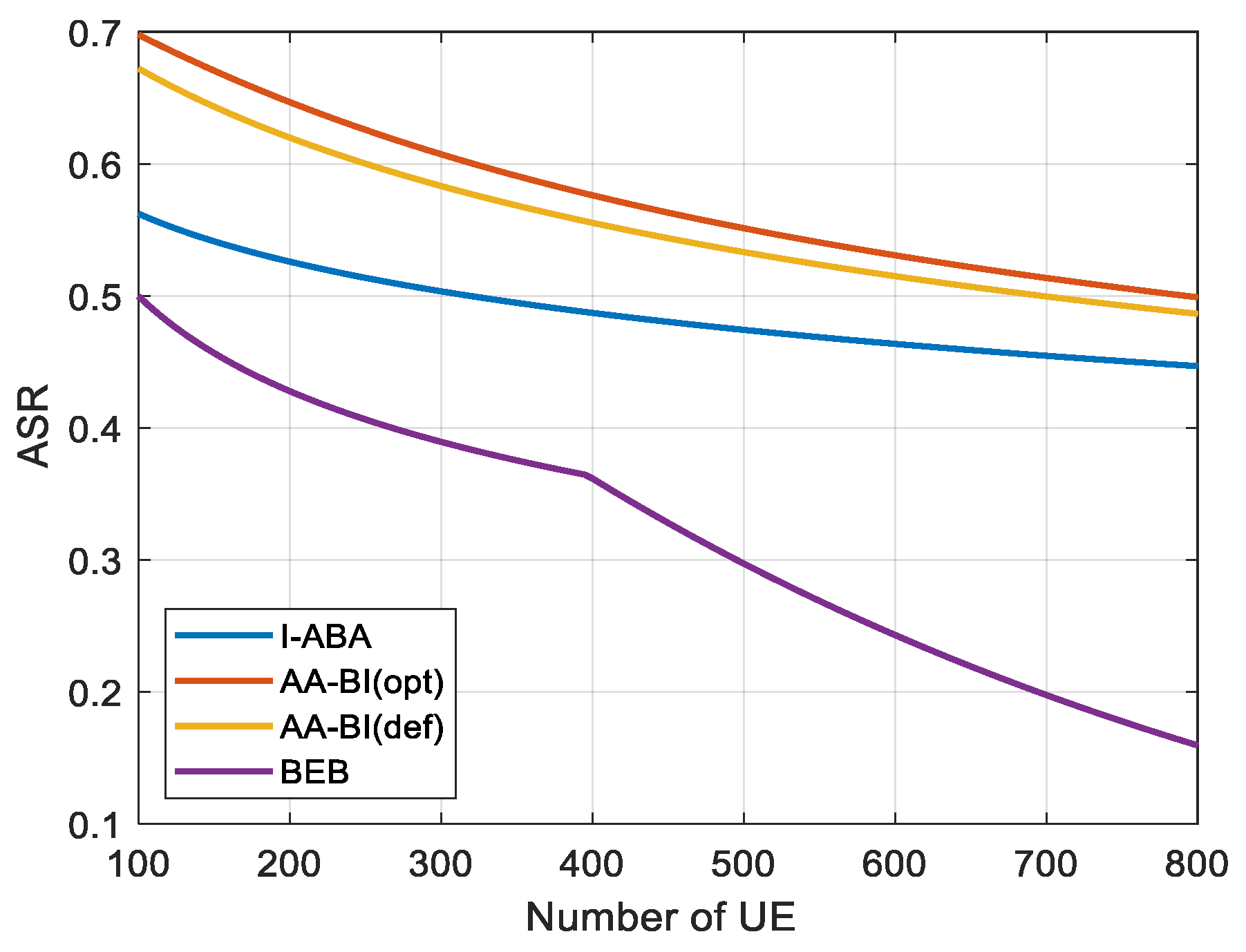

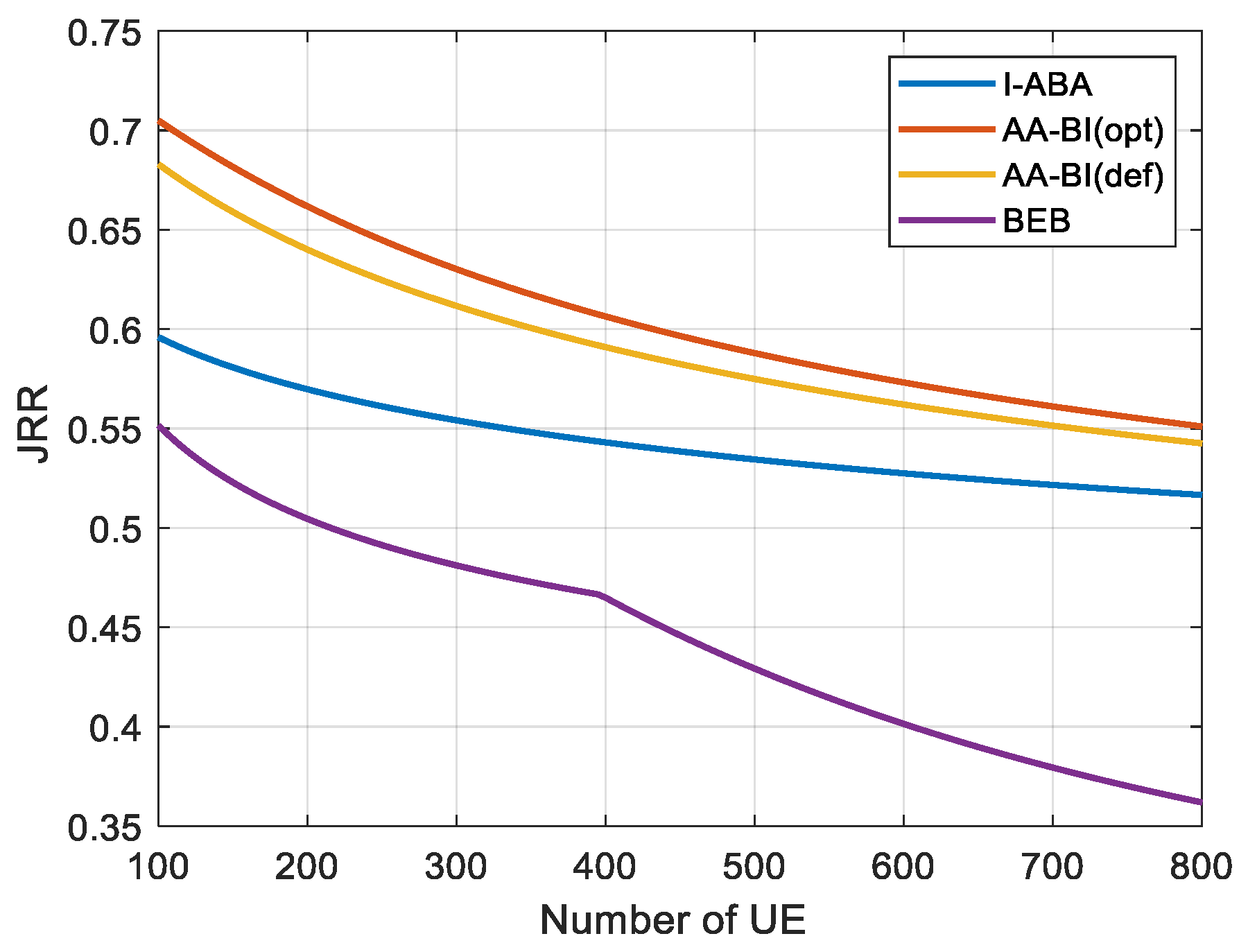

4.3. Analysis of Simulation Results

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Zhou, Y.; Chen, H.; Dou, Z. MOLM: Alleviating Congestion through Multi-Objective Simulated Annealing-Based Load Balancing Routing in LEO Satellite Networks. Future Internet 2024, 16, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Niu, H.; An, K.; et al. Refracting RIS-Aided Hybrid Satellite-Terrestrial Relay Networks: Joint Beamforming Design and Optimization. IEEE Trans. Aerosp. Electron. Syst. 2022, 58, 3717–3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iglesias-Sanuy, P.; López-Ardao, J.C.; Rodríguez-Pérez, M.; et al. An Efficient Location-Based Forwarding Strategy for Named Data Networking and LEO Satellite Communications. Future Internet 2022, 14, 285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Althumali, H.D.; Othman, M.; Noordin, N.K.; et al. Dynamic Backoff Collision Resolution for Massive M2M Random Access in Cellular IoT Networks. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 201345–201359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Non-Terrestrial Networks (NTN). Available online: https:// www.3gpp.org/technologies/ntn-overview (accessed on 24 August 2025).

- 3GPP. Solutions for NR to Support Non-Terrestrial Networks (NTN); TR 38.821, Version 19.0.0; 3GPP: Sophia Antipolis, France, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Guidotti, A.; Cioni, S.; et al. Architectures, Standardisation, and Procedures for 5G Satellite Communications: A Survey. Comput. Netw. 2020, 183, 107588. [Google Scholar]

- IEEE 802.15.4-2020; IEEE Standard for Low-Rate Wireless Networks. IEEE: Manhattan, NY, USA, 2020.

- Khanafer, M.; Guennoun, M.; El-Abd, M. Improved Adaptive Backoff Algorithm for Optimal Channel Utilization in Large-Scale IEEE 802.15.4-Based Wireless Body Area Networks. Future Internet 2024, 16, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halloush, R.D. Transmission Early-Stopping Scheme for Anti-Jamming Over Delay-Sensitive IoT Applications. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 7891–7906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, P.; Chu, F.; Jia, L.; et al. A Cross-Layer Anti-Jamming Method in Satellite Internet. IET Commun. 2023, 17, 121–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Liu, H.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, X.; Gan, J.; Li, D. A Resource Optimization for Two-Step Random Access in 5G New Radio. J. Phys. Conf. Ser. 2023, 2625, 012063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krummacker, D.; Veith, B.; Lindenschmitt, D.; Schotten, H.D. Radio Resource Sharing in 6G Private Networks: Trustworthy Spectrum Allocation for Coexistence through DLT as Core Function. In Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on 6G Networking (6GNet 2022), Paris, France, 6–8 July 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Mozaffari, M.; Saad, W.; Bennis, M.; Nam, Y.H.; Debbah, M. A Tutorial on UAVs for Wireless Networks: Applications, Challenges, and Open Problems. IEEE Commun. Surv. Tutor. 2019, 21, 2334–2360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, T.; Chae, S.H.; Bang, I. Two-Step Random Access With Message Replication for Low-Earth Orbit Satellite Networks. IEEE Wireless Commun. Lett. 2025, 14, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dawy, Z.; Saad, W.; Ghosh, A.; et al. Toward Massive Machine Type Cellular Communications. IEEE Wireless Commun. 2017, 24, 120–128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, W.; Xu, J.; et al. A Distributed Collaborative Entrance Defense Framework Against DDoS Attacks on Satellite Internet. IEEE Internet Things J. 2022, 9, 15497–15510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| N | Total number of UEs in the network | 200-800 |

| BE | Backoff Exponent | 3-11 |

| Wmin | Minimum backoff window | 8 |

| Wmax | Maximum backoff window | 2048 |

| k | Sensitivity coefficient | 0-20 |

| x0 | Activation threshold | 0-0.05 |

| Pdos | DoS attack intensity | 0-0.3 |

| Prep | replay attack intensity | 0-0.1 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).