Submitted:

04 March 2025

Posted:

05 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Related Work - Jamming Attacks on LoRaWAN

2.1. LoRaWAN Vulnerability to Jamming

2.2. Effectiveness of Different Jamming Methodologies

2.3. Real-Time Reactive Jamming on All LoRaWAN Channels

2.4. Feasibility of Real-Time Multichannel Reactive Jamming

| Study | Method Used | Multi-channel | All Spreading Factors | Low cost (< 1000 €) | Effective in all SF-Freq combinations | Hardware |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dossa et al. [37] | SDR-based minimal exposure jamming | x | x | x | x | USRP-2920 |

| Perković et al. [31,35] | Low-cost Arduino jammer | x | x | √ | x | LoRa module (SX1276) |

| Šabić et al. [38] | SDR-based reactive jamming | √ | √ | √ | x | HackRF ONE |

| This paper Scenario I | SDR-based reactive jamming | √ | √ | √ | x/ √ | HackRF ONE |

| This paper Scenario II | SDR-based reactive jamming | √ | √ | √ | √ | BladeRF |

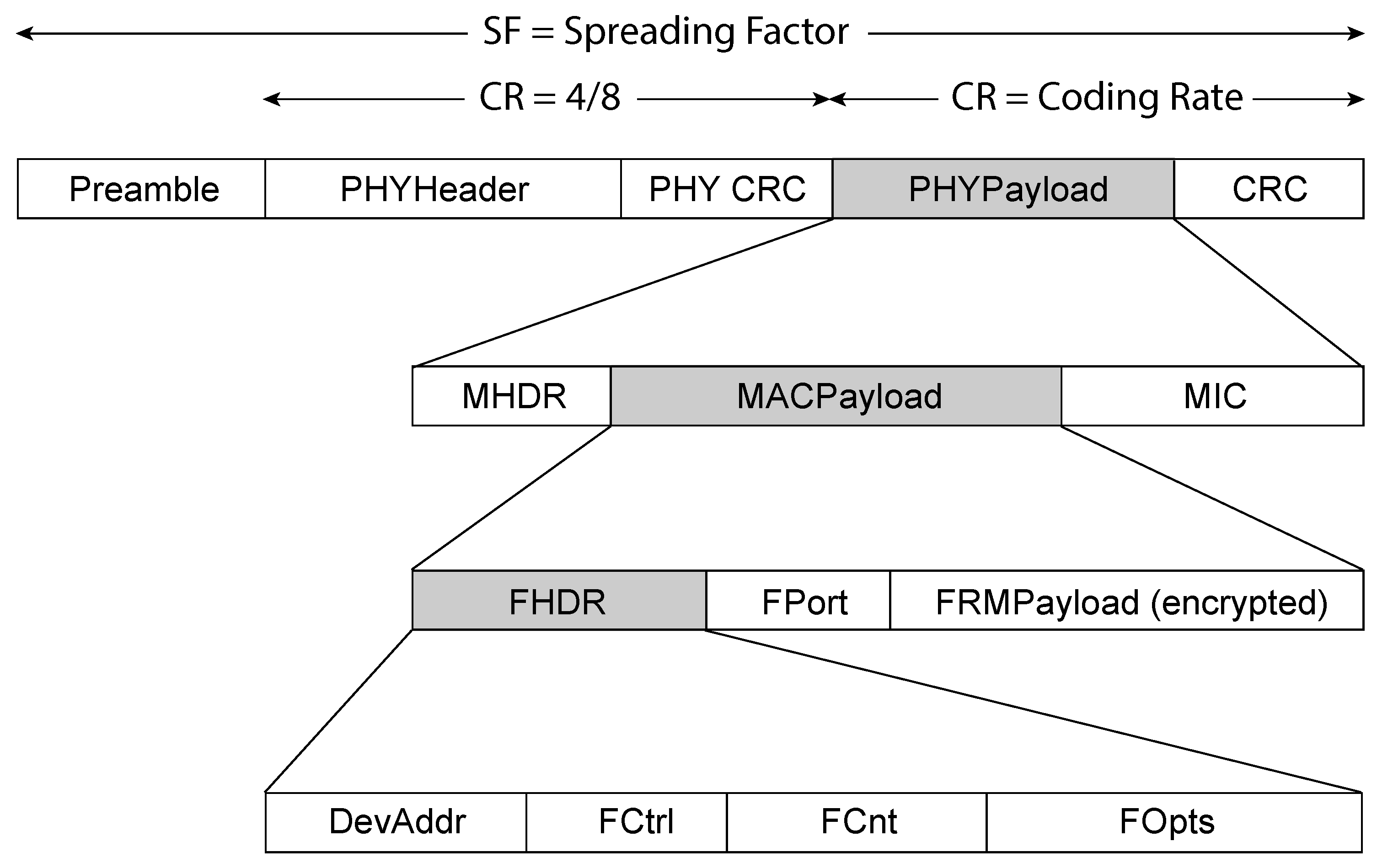

3. LoRa/LoRaWAN Message Transmission

3.1. Chirp Spread Spectrum (CSS) Modulation

3.2. Carrier Frequency (CF)

3.3. Coding Rate (CR)

3.4. Spreading Factor (SF)

3.5. Bandwidth (BW)

4. LoRaWAN

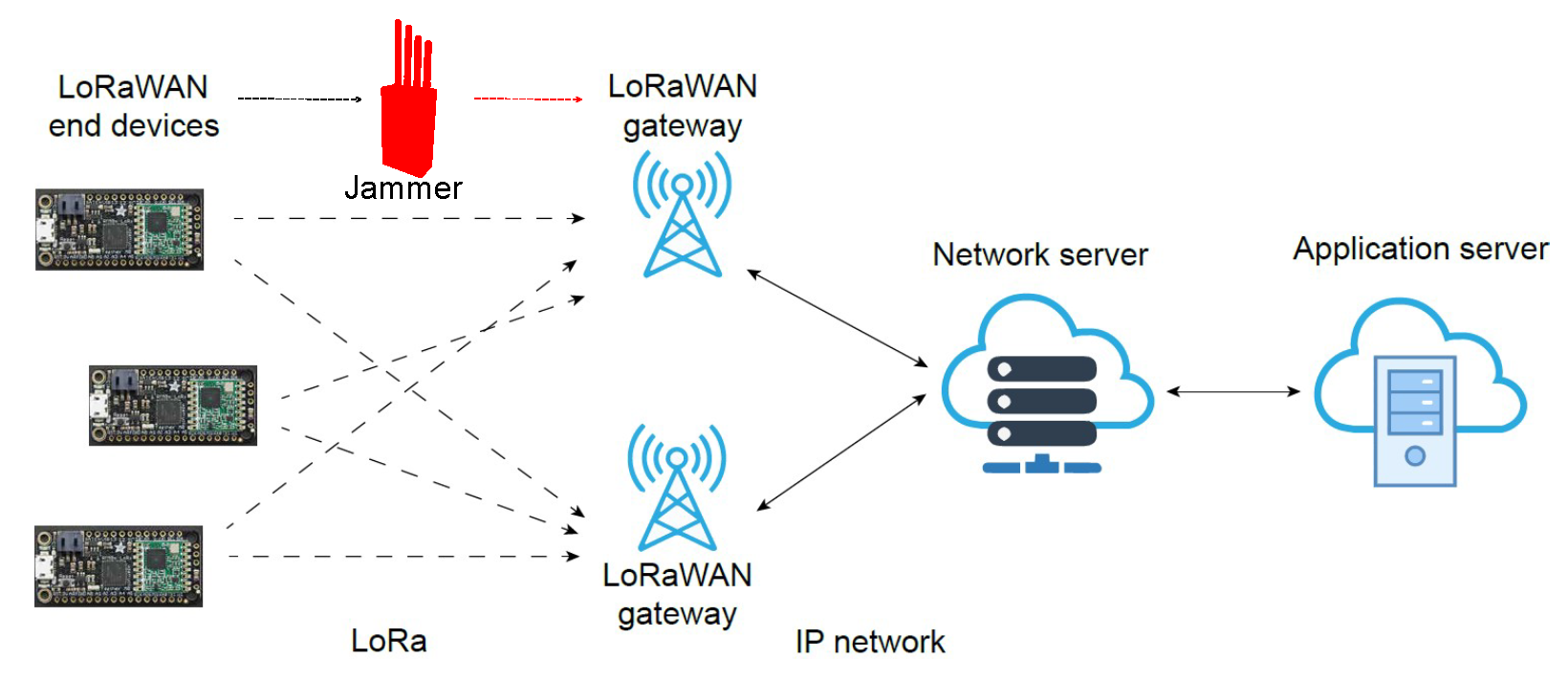

4.1. LoRaWAN Network Architecture

4.2. End Devices

4.3. LoRaWAN Packet Structure

4.4. Threat Model

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Hardware and Software Tools Used

-

HardwareOur host computer featured a 12th Gen Intel® Core™ i7-1255U processor (10 cores, 12 threads, 1.7 GHz base, up to 4.7 GHz) and 8 GB of RAM, providing sufficient resources for processing and analyzing incoming radio signals.To support the experimental objectives, we employed SDRs, which are versatile communication systems where traditional hardware components, such as mixers, filters, and modulators, are implemented through software, allowing for greater flexibility and adaptability across various communication protocols and frequencies. The setup utilized two notable SDRs: the BladeRF and the HackRF One. Although not as expensive as high-end SDRs, these devices provided sufficient performance for experimental jamming studies.The BladeRF operates over a frequency range of 300 MHz to 3.8 GHz, offering up to 28 MHz of instantaneous bandwidth with software-selectable filter options ranging from 1.5 MHz to 28 MHz. It supports arbitrary sample rates of up to 40 MSPS with 12-bit IQ samples. The device is fully bus-powered over USB 3.0, ensuring high-speed data transfer, and includes an external power option via a 5V DC barrel jack.The HackRF One covers frequencies from 1 MHz to 6 GHz and supports a maximum sample rate of 20 million samples per second with 8-bit quadrature sampling, enabling versatile transmission and reception capabilities. Together, the host computer and these SDRs provided a robust platform to analyze and manipulate radio signals across a broad spectrum, facilitating advanced wireless communication research and development. A limitation of the HackRF One is that it does not support full-duplex operation, which increases reaction time in certain setups.For the LoRaWAN network components, we used the LILYGO TTGO T-Beam V1.0 as the end node device. This ESP32-based board features integrated LoRa (868/915MHz) and GPS capabilities, along with Wi-Fi and Bluetooth connectivity. As the gateway, we employed the Laird Sentrius RG1xx, an 8-channel LoRaWAN gateway supporting dual-band Wi-Fi and Ethernet connectivity, compatible with various LoRaWAN network servers.

-

SoftwareThe software implementation of the system was developed using GNU Radio, a powerful open-source software toolkit for building software-defined radios. GNU Radio enabled the modular design of the signal processing flowgraph, allowing seamless integration of various blocks for real-time detection and analysis of LoRaWAN signals. GNU Radio was chosen for its open source flexibility, allowing real-time signal processing without requiring expensive proprietary tools. Additionally, it offers extensive libraries and preexisting modulation/demodulation blocks for LoRa, simplifying implementation. It also provides seamless SDR integration with direct support for BladeRF and HackRF One devices.A critical component of the setup was the ChirpDetector block, sourced from the gr-LibreLoRa library 1. This block was instrumental in identifying LoRa chirps using their unique modulation characteristics, facilitating the extraction of parameters such as spread factor, bandwidth, and normalized frequency. The combination of GNU Radio’s flexibility and the specialized capabilities of the ChirpDetector block ensured efficient and accurate signal processing.

5.2. Description of Experimental Setup

-

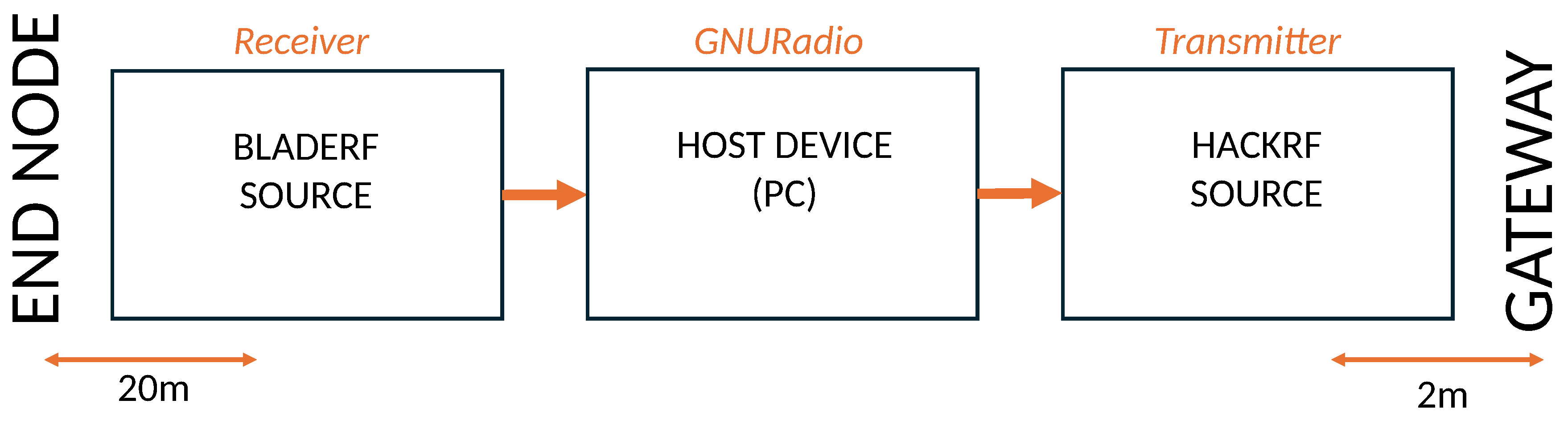

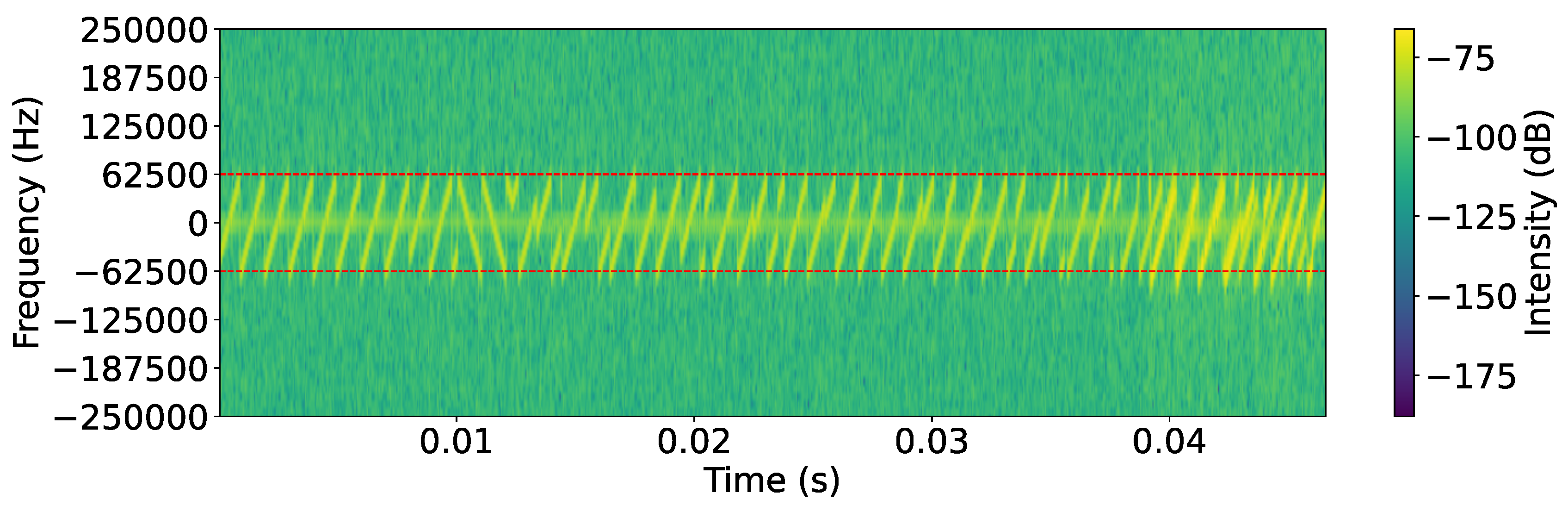

Scenario 1: BladeRF as receiver, HackRF One as transmitter:Scenario I employs three devices—a BladeRF receiver, a HackRF One transmitter, and a host PC as illustrated in Figure 3 and shown in Figure 4. The BladeRF monitors the full EU LoRaWAN spectrum and forwards captured signals to the PC for processing to extract key parameters such as the SF, frequency, and BW. Based on the analysis, the HackRF One is used to transmit pre-recorded jamming packets on the detected frequency and SF, effectively interfering with legitimate LoRaWAN communication. This scenario mimics practical attack scenarios with affordable SDRs. We anticipated that this would be a cost-effective setup, offer flexible deployment, allow better control over hardware placement and synchronization testing, and allow decoupling of function for more precise monitoring of the jamming reaction time. However, we anticipated potential disadvantages, including increased latency due to communication between separate SDRs and synchronization challenges with hardware-dependent timing variations.

-

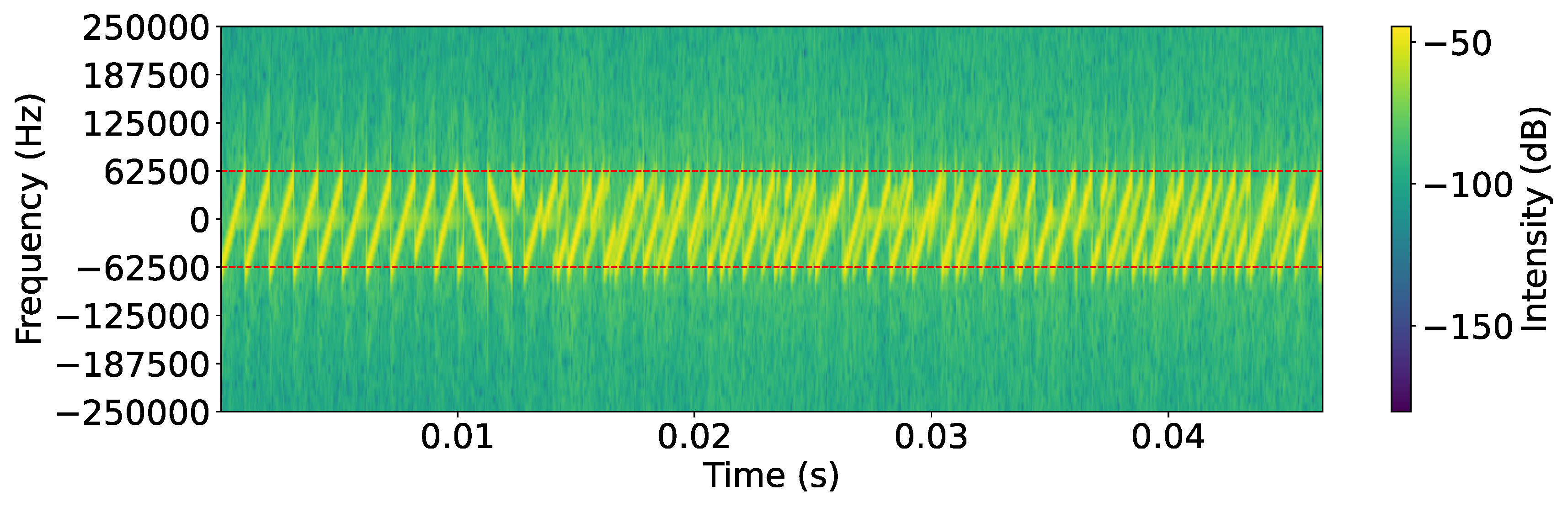

Scenario 2: BladeRF as both receiver and transmitter:In this scenario, only two devices are used: BladeRF and a host device (PC), as illustrated in Figure 5 and shown in Figure 6. The BladeRF SDR operates as both a receiver and a transmitter, monitoring all channels in the EU LoReWAN spectrum. The captured signals are processed on the host device, where relevant parameters are extracted. Once a target signal is detected, the BladeRF itself transmits the corresponding jamming packets on the detected frequency and SF, eliminating the need for a separate transmitter. This setup ensures a streamlined approach to signal acquisition and jamming within a single device. This scenario was designed to test the hypothesis that a single-device setup could lead to a faster jamming response. We anticipated that the advantages would include lower reaction time by eliminating the need for inter-device communication, improved synchronization by having both reception and transmission within the same SDR, and more efficient jamming due to reduced hardware switching time. However, we also anticipated disadvantages, including a higher processing load on the BladeRF, potentially introducing processing bottlenecks, limited flexibility for experimental variations requiring separate spatial positioning of the receiver and transmitter, and potential RF performance issues due to full-duplex operation in a single SDR.

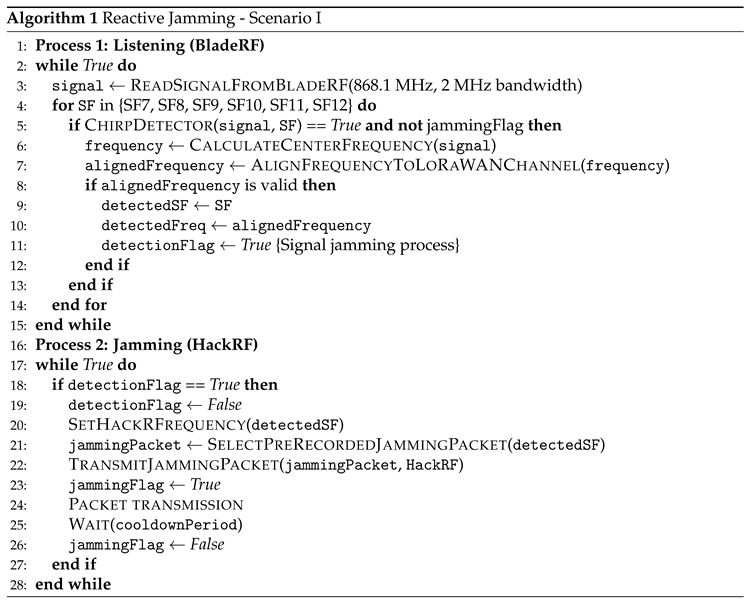

5.3. Step-by-Step Process: SCENARIO I

-

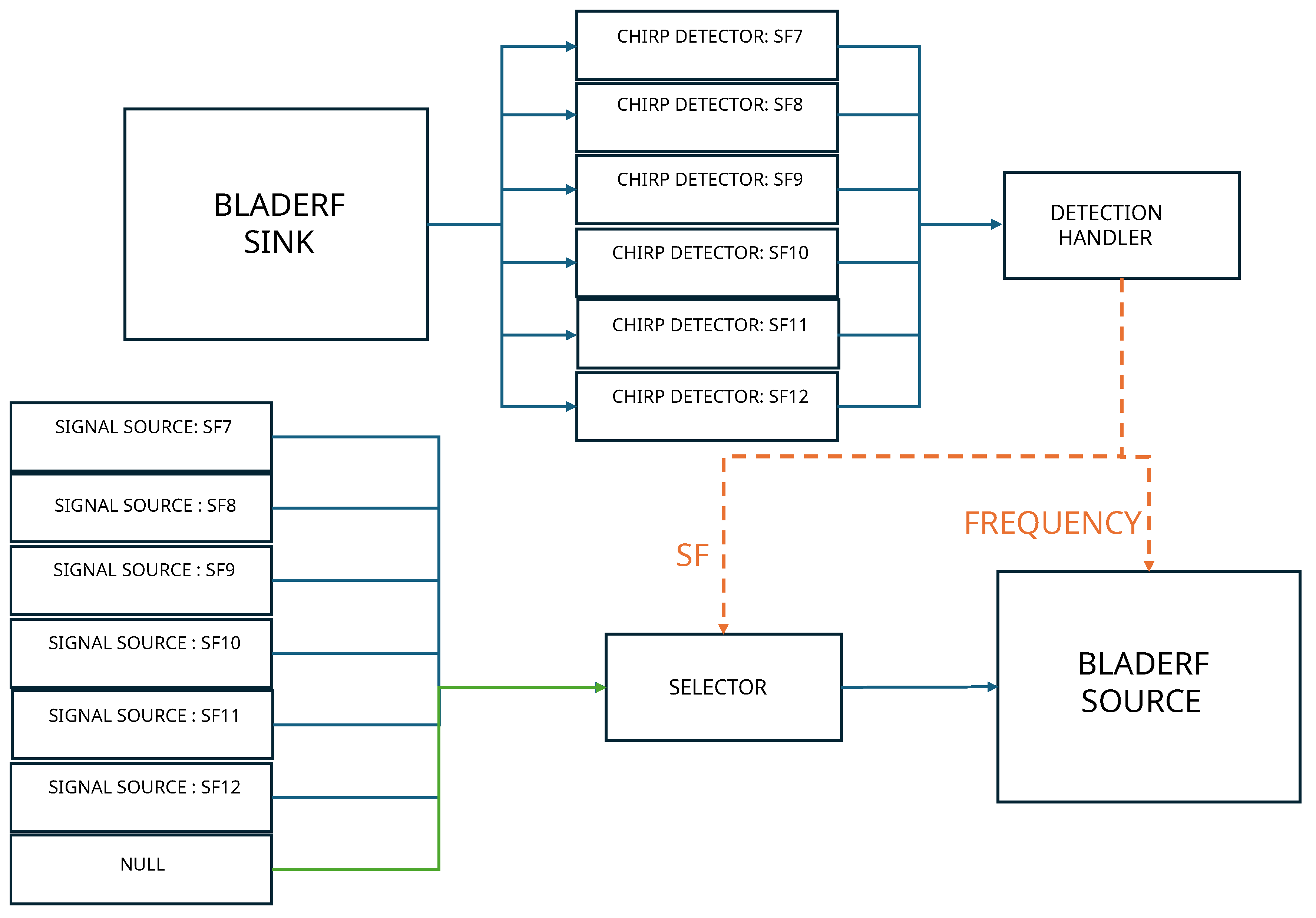

Listening signal (process 1)The system employs a structured listening process using a SDR and custom processing blocks to detect LoRaWAN packets with precision. The listening signal operates as a single process, which, through the Python multiprocessing library, shares events and data with a second process responsible for signal jamming. The SDR source, a bladeRF device, is configured to monitor signals within the 868.1 MHz band with a listening bandwidth of 2 MHz. This setup captures incoming radio signals, which are then analyzed through a series of ChirpDetector blocks, each calibrated for SF ranging from 7 to 12. These detectors identify LoRa chirps and provide key parameters such as the spreading factor, bandwidth, and normalized frequency.A custom DetectionHandler block processes events triggered by the ChirpDetector blocks. It calculates the central frequency of the detected signal by using the normalized frequency output from the ChirpDetectors, along with the SDR’s sampling rate and center frequency. Detected frequencies are then aligned to the nearest predefined LoRaWAN channel frequencies, such as 867.1 MHz or 868.3 MHz. When a valid chirp is detected, its parameters, including SF and frequency, are recorded, and a detection flag is raised to initiate subsequent processes, such as signal jamming.The SDR source is connected in parallel to all ChirpDetector blocks, with detection events relayed to the DetectionHandler through message ports for real-time processing. This efficient architecture enables accurate detection and characterization of LoRaWAN packets, forming the foundation for advanced signal analysis and interference mechanisms.

-

Jamming signal (process 2) The jamming process is implemented using a dedicated SDR and pre-recorded legitimate LoRaWAN packets for each SF. These precomputed signals are stored in memory and serve as inputs for the SDR sink, which is responsible for their transmission.When a valid detection is signaled by the detection flag, the system retrieves the detected SF and frequency from the first process. It then dynamically sets the frequency of the SDR sink to match the detected LoRaWAN signal. The system selects the appropriate pre-recorded and pre-loaded signal source corresponding to the detected SF and connects it to the SDR sink. Once the selection is complete, the flowgraph is started, initiating the jamming transmission.

-

Synchronization Between ProcessesThe sensing and jamming processes in the system are designed to run concurrently, leveraging Python’s multiprocessing module to enable parallel execution and efficient synchronization. Multiprocessing provides a way to create separate processes that can execute tasks simultaneously, each with its own memory space. In the context of this system, multiprocessing is used to handle the independent operations of signal detection and jamming while ensuring they remain coordinated.Shared variables are a core feature of the multiprocessing framework, allowing real-time communication between processes. In this implementation, shared variables store key parameters such as the detected frequency and SF, ensuring both the sensing and jamming processes have consistent and accurate data. For instance, the detected frequency is updated by the sensing process and then accessed by the jamming process to adjust the transmitter’s center frequency dynamically.In addition to shared variables, the system uses event flags to coordinate actions between processes. The detection flag signals the jamming process to start when a valid detection occurs. The jamming flag indicates when the transmitter is actively jamming, ensuring the sensing process pauses to avoid interference. The cooldown flag enforces a mandatory waiting period after jamming, preventing immediate consecutive detections and allowing the system to stabilize.By combining multiprocessing’s ability to run parallel tasks with shared variables and event-driven synchronization, the system achieves real-time responsiveness and operational efficiency. This architecture ensures that the detection and jamming processes remain tightly integrated while operating independently, a critical requirement for time-sensitive signal processing tasks.

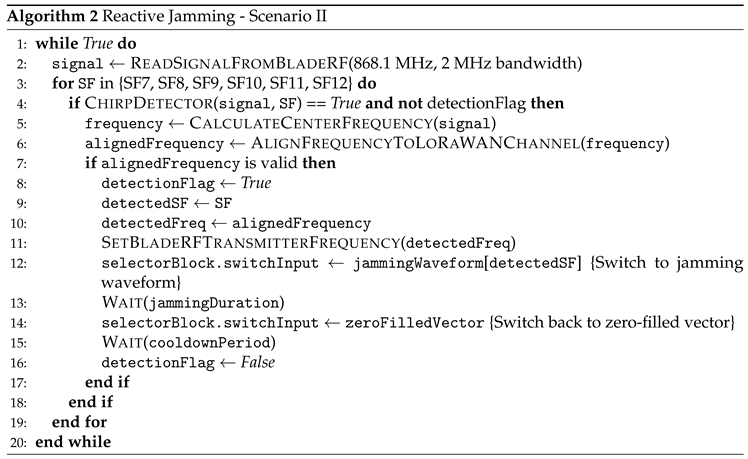

5.4. Step-by-Step Process: SCENARIO II

-

Listening SignalThe listening process follows the same logic as described in Scenario I, utilizing the bladeRF SDR to capture and analyze LoRaWAN signals with high precision.

-

Jamming SignalThe jamming process is integrated within the same flowgraph used for signal detection, ensuring uninterrupted SDR operation. Since the parts of flowgraph cannot be dynamically turned on or off, a selector block is used to control the jamming mechanism. The selector dynamically switches between a pre-loaded jamming waveform and a zero-filled vector, allowing the bladeRF to transmit interference only when necessary while remaining active at all times.Upon detecting a LoRaWAN signal, the detection flag triggers the switching input of selector block. Initially, the selector block is set to the zero-filled vector (indicating no transmission). Once jamming is required, it dynamically switches to the appropriate jamming waveform for the detected SF. The bladeRF’s transmitter aligns its center frequency to match the detected signal, ensuring accurate interference. After a predefined duration, the selector block is reset to the zero vector, halting jamming while keeping the flowgraph operational.

-

Signal Processing and Synchronization Unlike Scenario I, this implementation operates within a single process, managing sensing and jamming sequentially. This reduces overhead and simplifies synchronization, while maintaining real-time responsiveness.Event flags coordinate the system’s state transitions. The detection flag initiates jamming, temporarily pausing chirp detection to prevent interference with the transmitted signal. A cooldown period follows each jamming event, allowing the system to stabilize before resuming normal sensing operations.

6. Results

6.1. Metrics Used to Measure Attack Effectiveness

- PLR: Definition as the percentage of packets transmitted that were successfully jammed and did not reach their intended destination.

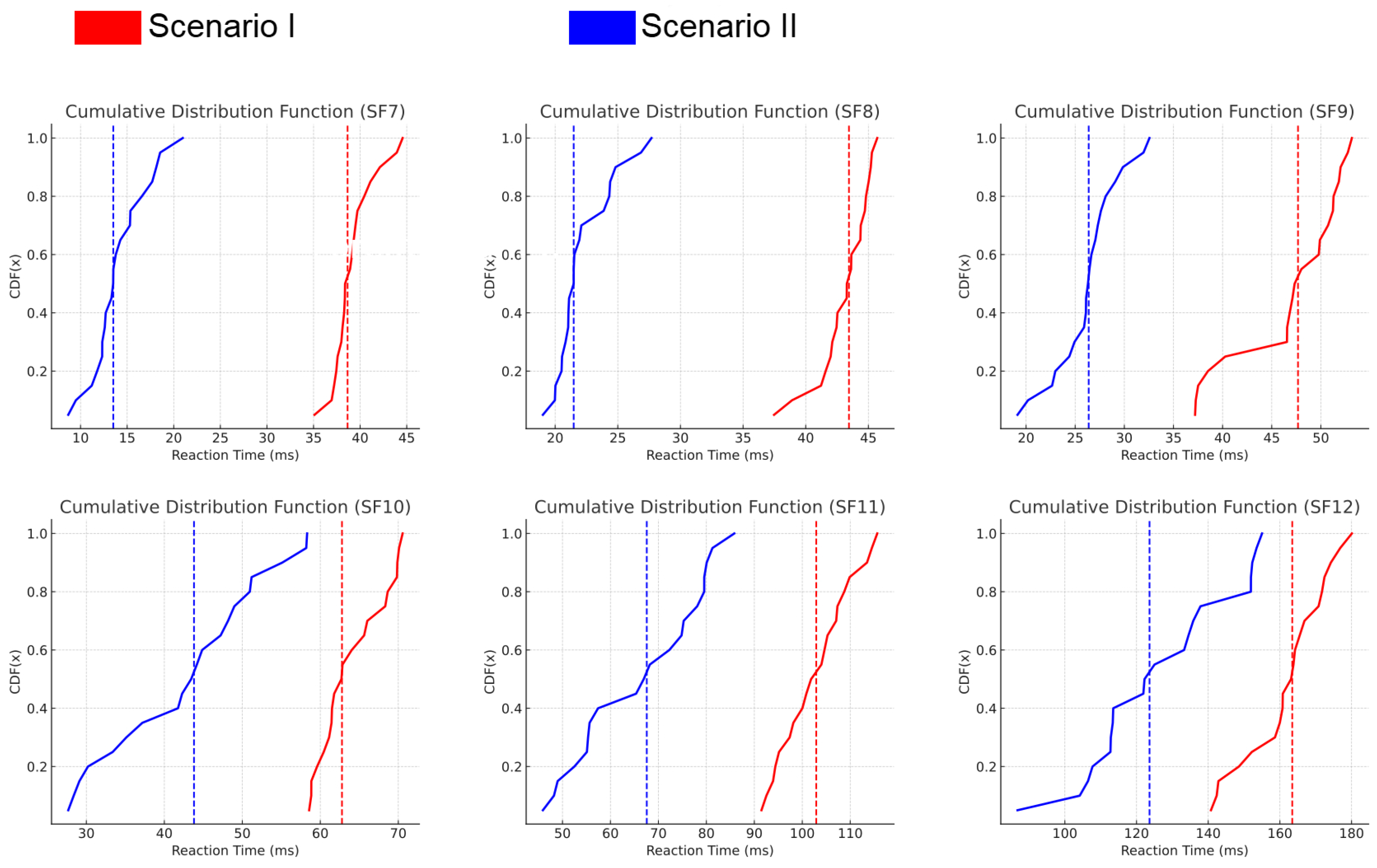

- Reaction Time Distribution: Analyzed using the Cumulative Distribution Function (CDF), which illustrates the probability that the jammer reacts within a certain time threshold.

6.2. Experimental Setup and Methodology

- Ensuring Reproducibility: Given that SDR-based systems experience slight timing fluctuations due to processing delays, multiple trials helped confirm the consistency of attack effectiveness.

- Comparing Different Scenarios: Conducting multiple trials for Scenario I (HackRF One + BladeRF) and Scenario II (BladeRF only) ensured a fair comparison of the two setups.

6.3. Detailed Experimental Results

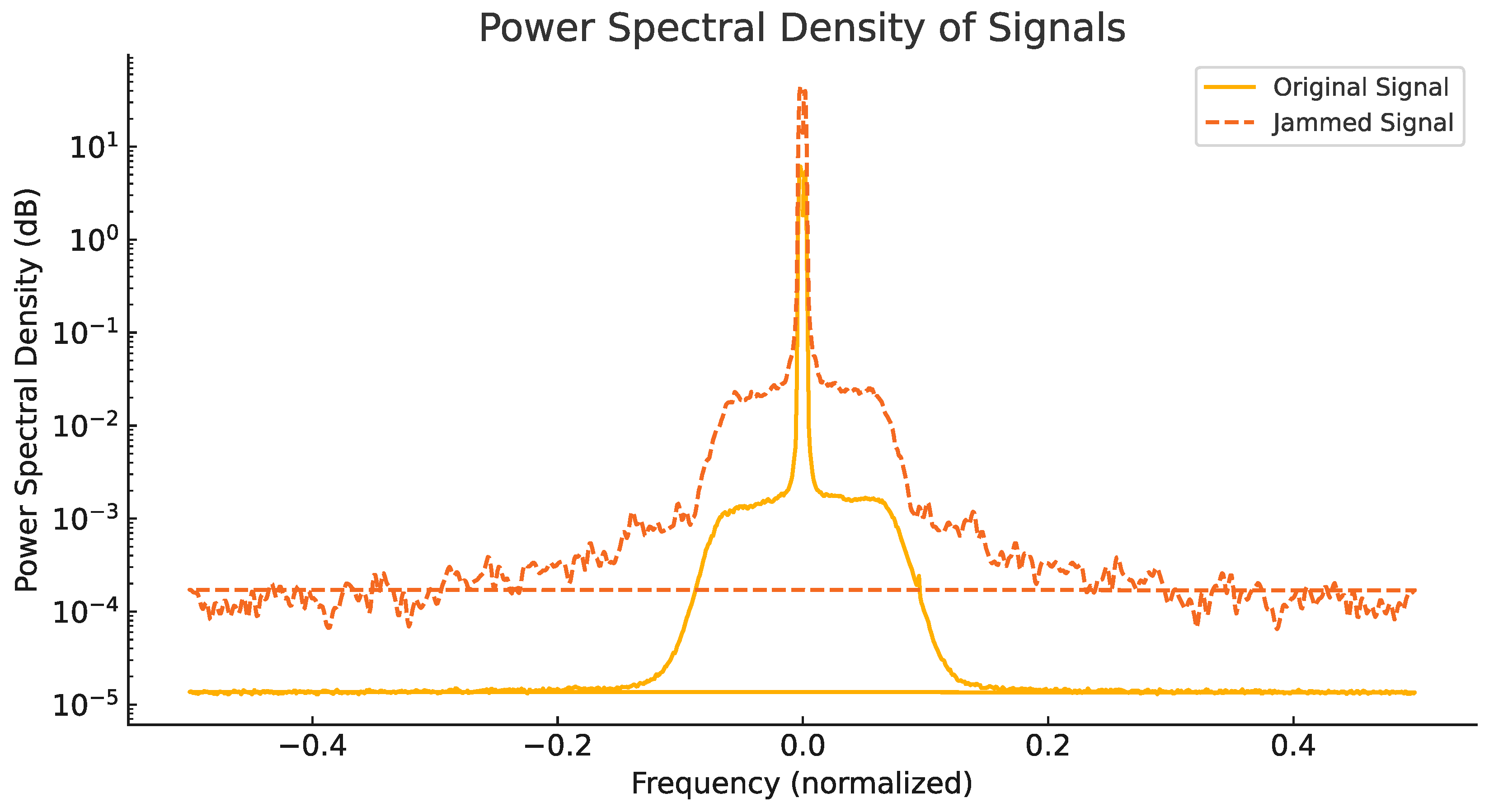

6.3.1. Power Spectral Density Analysis (PSD)

- The jamming signal aligns closely with the center frequency of the legitimate LoRaWAN signal (normalized to 0), ensuring effective interference.

- The power level of the jamming signal is consistently higher than that of the legitimate signal on overlapping frequencies, effectively overpowering it.

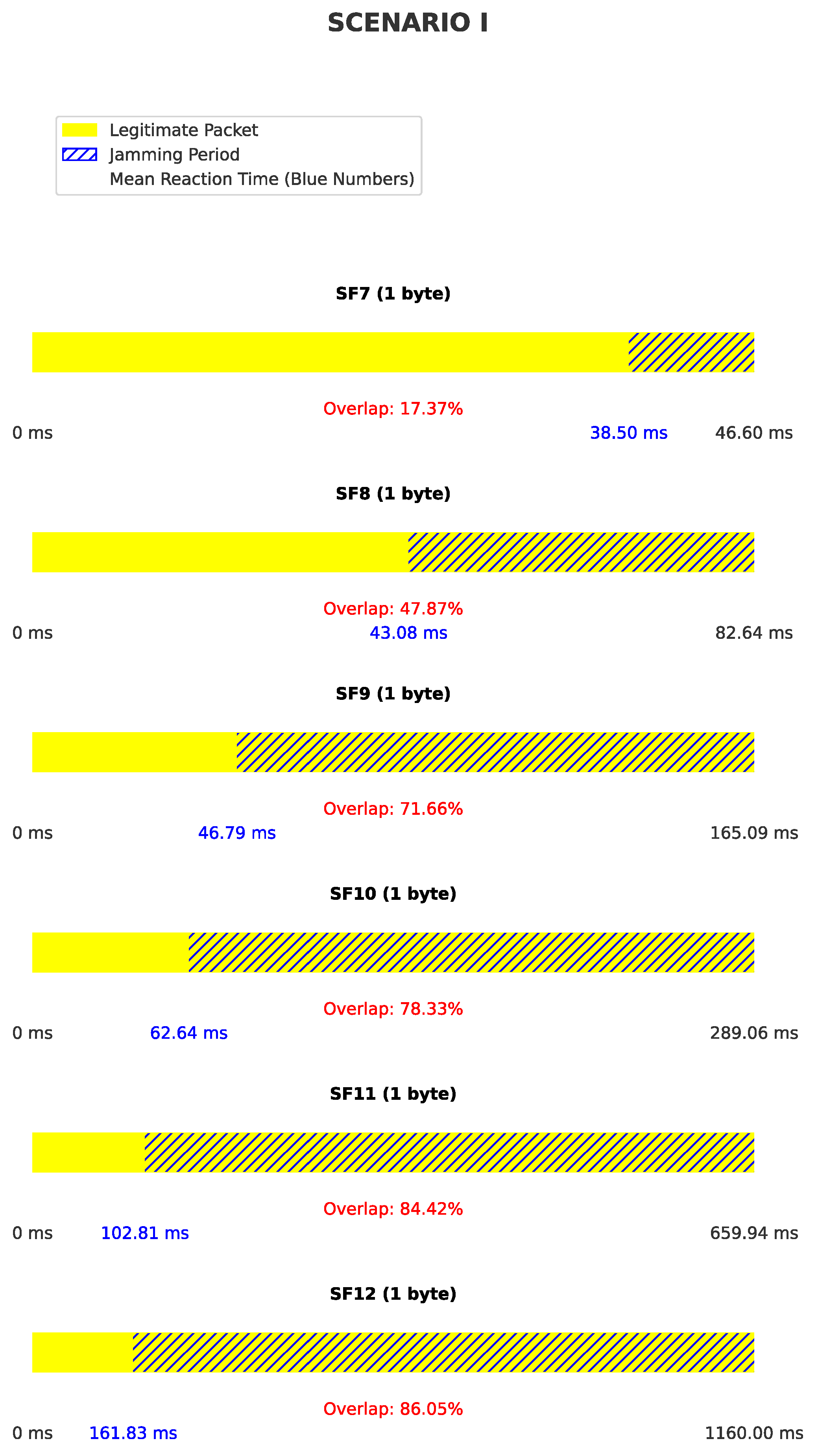

6.3.2. Scenario I: BladeRF as Receiver, HackRF One as Transmitter

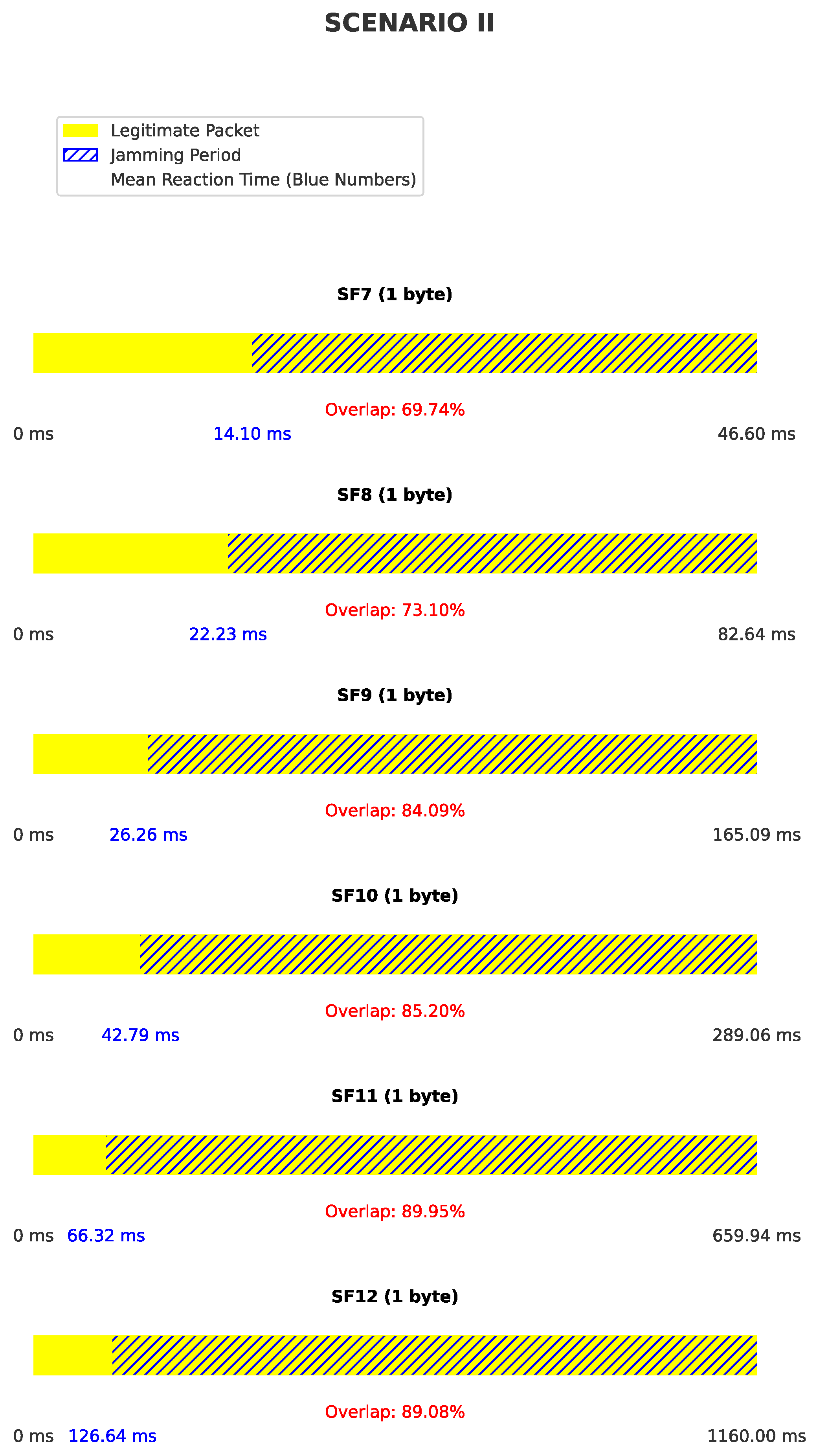

6.3.3. Scenario II: BladeRF as Both Receiver and Transmitter

6.4. Limitations

7. Discussion

7.1. Comparison of Scenarios

7.2. Jamming Effectiveness and Packet Overlap

7.3. Reaction Time and Spreading Factors

- Lower SFs (e.g., SF7) exhibit faster reaction times due to shorter symbol durations.

- Higher SFs allow for longer reaction times while still achieving successful jamming because of larger duration of the packet.

7.4. Future Research Directions

- Minimal Jamming Packet Size: Investigate the minimum size of jamming packets (e.g., few chirps) required for successful disruption.

- Targeted Jamming: Analyze which specific parts of LoRaWAN packets are most vulnerable to jamming.

- Real-world Deployment Impact: Assess the effectiveness of the attack in various environmental conditions and network topologies.

- Advanced Countermeasures: Develop and test sophisticated defense mechanisms against reactive jamming.

8. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Mahdavinejad, M.S.; Rezvan, M.; Barekatain, M.; Adibi, P.; Barnaghi, P.M.; Sheth, A.P. Machine learning for Internet of Things data analysis: A survey. CoRR, 1802; abs/1802.06305. [Google Scholar]

- Sain, M.; Kang, Y.J.; Lee, H.J. Survey on security in Internet of Things: State of the art and challenges. In Proceedings of the 2017 19th International Conference on Advanced Communication Technology (ICACT); 2017; pp. 699–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sanchez-Iborra, R.; Cano, M.D. State of the Art in LP-WAN Solutions for Industrial IoT Services. Sensors 2016, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Centenaro, M.; Vangelista, L.; Zanella, A.; Zorzi, M. Long-range communications in unlicensed bands: the rising stars in the IoT and smart city scenarios. IEEE Wireless Communications 2016, 23, 60–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mangalvedhe, N.; Ratasuk, R.; Ghosh, A. NB-IoT deployment study for low power wide area cellular IoT. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE 27th Annual International Symposium on Personal, Indoor, and Mobile Radio Communications (PIMRC); 2016; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petäjäjärvi, J.; Mikhaylov, K.; Pettissalo, M.; Janhunen, J.; Iinatti, J. Performance of a low-power wide-area network based on LoRa technology: Doppler robustness, scalability, and coverage. International Journal of Distributed Sensor Networks 2017, 13, 1550147717699412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adelantado, F.; Vilajosana, X.; Tuset-Peiro, P.; Martinez, B.; Melia-Segui, J.; Watteyne, T. Understanding the Limits of LoRaWAN. IEEE Communications Magazine 2017, 55, 34–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vangelista, L.; Zanella, A.; Zorzi, M. Long-Range IoT Technologies: The Dawn of LoRa™. In Proceedings of the Future Access Enablers for Ubiquitous and Intelligent Infrastructures; Atanasovski, V.; Leon-Garcia, A., Eds., Cham; 2015; pp. 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Haxhibeqiri, J.; De Poorter, E.; Moerman, I.; Hoebeke, J. A Survey of LoRaWAN for IoT: From Technology to Application. Sensors 2018, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lora Alliance. LoRaWAN 1.1 Specification, Oct. 2017. http://lora-alliance.org/lorawan-for-developers. [Online; accessed 28-February-2021].

- Mikhaylov, K.; Fujdiak, R.; Pouttu, A.; Miroslav, V.; Malina, L.; Mlynek, P. Energy Attack in LoRaWAN: Experimental Validation. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 14th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security; ARES ’19. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Butun, I.; Pereira, N.; Gidlund, M. Security Risk Analysis of LoRaWAN and Future Directions. Future Internet 2019, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Karampatzakis, E.; Doerr, C.; Kuipers, F. Security Vulnerabilities in LoRaWAN. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE/ACM Third International Conference on Internet-of-Things Design and Implementation (IoTDI); 2018; pp. 129–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dönmez, T.C.; Nigussie, E. Security of LoRaWAN v1. 1 in backward compatibility scenarios. Procedia computer science 2018, 134, 51–58. [Google Scholar]

- Butun, I.; Pereira, N.; Gidlund, M. Analysis of LoRaWAN v1.1 Security: Research Paper. 2018, SMARTOBJECTS ’18.

- Aras, E.; Small, N.; Ramachandran, G.S.; Delbruel, S.; Joosen, W.; Hughes, D. Selective Jamming of LoRaWAN Using Commodity Hardware. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 14th EAI International Conference on Mobile and Ubiquitous Systems: Computing, Networking and Services, 2017, MobiQuitous 2017, p. [CrossRef]

- Aras, E.; Ramachandran, G.S.; Lawrence, P.; Hughes, D. Exploring the Security Vulnerabilities of LoRa. In Proceedings of the 2017 3rd IEEE International Conference on Cybernetics (CYBCONF); 2017; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Noura, H.; Hatoum, T.; Salman, O.; Yaacoub, J.P.; Chehab, A. LoRaWAN security survey: Issues, threats and possible mitigation techniques. Internet of Things 2020, 12, 100303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- JungWoon Lee.; DongYeop Hwang.; JiHong Park.; Ki-Hyung Kim. Risk analysis and countermeasure for bit-flipping attack in LoRaWAN. In Proceedings of the 2017 International Conference on Information Networking (ICOIN), 2017, pp. 549–551. [CrossRef]

- Yang, X. LoRaWAN: Vulnerability Analysis and Practical Exploitation. Master’s thesis, Delft University of Technology, Delft, The Netherlands, 2017. M.Sc. Thesis.

- Ingham, M.; Marchang, J.; Bhowmik, D. IoT security vulnerabilities and predictive signal jamming attack analysis in LoRaWAN. IET information security 2020, 14, 368–379. [Google Scholar]

- Martinez, I.; Tanguy, P.; Nouvel, F. On the performance evaluation of LoRaWAN under Jamming. In Proceedings of the 2019 12th IFIP Wireless and Mobile Networking Conference (WMNC). IEEE; 9 2019; pp. 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmar, A.U.H.; Aras, E.; Nguyen, T.D.; Michiels, S.; Joosen, W.; Hughes, D. Design of a Robust MAC Protocol for LoRa. ACM Transactions on Internet of Things 2023, 4, 1–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, N.; Xia, X.; Zheng, Y. Jamming of LoRa PHY and Countermeasure. ACM Transactions on Sensor Networks 2023, 19, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.Y.; Lin, C.W.; Cheng, R.G.; Yang, S.J.; Sheu, S.T. Experimental Evaluation of Jamming Threat in LoRaWAN. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE 89th Vehicular Technology Conference (VTC2019-Spring). IEEE; 4 2019; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- José, A.N.D.S.; Deniau, V.; Gransart, C.; Vantroys, T.; Boé, A.; Simon, E.P. Susceptibility of LoRa Communications to Intentional Electromagnetic Interference with Different Sweep Periods. Sensors 2022, 22, 5015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sun, Z.; Yang, H.; Liu, K.; Yin, Z.; Li, Z.; Xu, W. Recent Advances in LoRa: A Comprehensive Survey. ACM Transactions on Sensor Networks 2022, 18, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martinez, I.; Nouvel, F.; Lahoud, S.; Tanguy, P.; Helou, M.E. On the Performance Evaluation of LoRaWAN with Re-transmissions under Jamming. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE Symposium on Computers and Communications (ISCC). IEEE; 7 2020; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Torres, N.; Pinto, P.; Lopes, S.I. Exploiting Physical Layer Vulnerabilities in LoRaWAN-based IoT Networks. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 8th World Forum on Internet of Things (WF-IoT). IEEE; 10 2022; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmar, A.U.H.; Aras, E.; Joosen, W.; Hughes, D. Towards More Scalable and Secure LPWAN Networks Using Cryptographic Frequency Hopping. In Proceedings of the 2019 Wireless Days (WD). IEEE; 4 2019; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perković, T.; Rudeš, H.; Damjanović, S.; Nakić, A. Low-Cost Implementation of Reactive Jammer on LoRaWAN Network. Electronics 2021, 10, 864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ruotsalainen, H. Reactive Jamming Detection for LoRaWAN Based on Meta-Data Differencing. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 17th International Conference on Availability, Reliability and Security. [CrossRef]

- Kalokidou, V.; Nair, M.; Beach, M.A. LoRaWAN Performance Evaluation and Resilience under Jamming Attacks. In Proceedings of the 2022 Sensor Signal Processing for Defence Conference (SSPD). IEEE; 9 2022; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadatkar, P.V.; Chaudhari, B.S.; Zennaro, M. Impact of Interference on LoRaWAN Link Performance. In Proceedings of the 2019 5th International Conference On Computing, Communication, 9 2019, Control And Automation (ICCUBEA). IEEE; pp. 1–5. [CrossRef]

- Perkovic, T.; Siriscevic, D. Low-Cost LoRaWAN Jammer. In Proceedings of the 2020 5th International Conference on Smart and Sustainable Technologies (SpliTech). IEEE; 9 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Danish, S.M.; Nasir, A.; Qureshi, H.K.; Ashfaq, A.B.; Mumtaz, S.; Rodriguez, J. Network Intrusion Detection System for Jamming Attack in LoRaWAN Join Procedure. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Communications (ICC). IEEE; 5 2018; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dossa, A.; Amhoud, E.M. Impact of Reactive Jamming Attacks on LoRaWAN: a Theoretical and Experimental Study 2025.

- Šabić, J.; Perković, T.; Šolić, P. Chirp Detection and Signal Transmission: a HackRF Reactive Attack. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Smart Systems and Technologies (SST). IEEE; 10 2024; pp. 35–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beltramelli, L.; Mahmood, A.; Österberg, P.; Gidlund, M. LoRa beyond ALOHA: An investigation of alternative random access protocols. IEEE Transactions on Industrial Informatics 2020, 17, 3544–3554. [Google Scholar]

- Iglesias-Rivera, A.; Van Glabbeek, R.; Guerra, E.O.; Braeken, A.; Steenhaut, K.; Cruz-Enriquez, H. Time-slotted spreading factor hopping for mitigating blind spots in LoRa-Based networks. Sensors 2022, 22, 2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gaitan, N.C. A long-distance communication architecture for medical devices based on LoRaWAN protocol. Electronics 2021, 10, 940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LoRa Alliance Technical Committee. https://lora-alliance.org/resource_hub/lorawan-specification-v1-0-3/. [Online; accessed 28-February-2021].

| 1 |

| SF / Payload (Bytes) | 1 | 5 | 15 | 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF7 | 50% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| SF8 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| SF9 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| SF10 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| SF11 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| SF12 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| SF / Payload (Bytes) | 1 | 5 | 15 | 20 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| SF7 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| SF8 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| SF9 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| SF10 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| SF11 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

| SF12 | 100% | 100% | 100% | 100% |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).