1. Introduction

Achondroplasia is the most prevalent form of skeletal dysplasia, occurring in approximately 1 in 15,000 to 1 in 25,000 live births worldwide [

1,

2]. This autosomal dominant disorder is primarily caused by mutations in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (

FGFR3) gene, with the G380R mutation accounting for >95% of cases [

3,

4]. The condition is characterized by a disproportionate short stature, with the affected individuals typically achieving an adult height of 120-145 cm, along with distinctive features including macrocephaly, frontal bossing, and limb shortening predominantly affecting the proximal segments [

5,

6].

While extensive research has focused on the medical complications associated with achondroplasia, including spinal stenosis, sleep apnea, and orthopedic concerns [

7,

8], there remains a significant gap in understanding the functional independence capabilities of individuals with this condition across the lifespan. Previous studies have predominantly examined growth patterns, surgical interventions, and medical management strategies [

9,

10], but comprehensive assessments of daily living skills using standardized functional outcome measures have been limited.

The importance of functional assessment in populations with physical disabilities cannot be overstated because it provides crucial insights for rehabilitation planning, educational accommodations, and family support services [

11,

12]. The Functional Independence Measure for Children (WeeFIM) has emerged as a gold standard tool for evaluating functional independence in pediatric rehabilitation settings [

13,

14]. This instrument assesses 18 items across 3 critical domains: self-care activities (i.e., eating, grooming, bathing, dressing, toileting, and continence); mobility functions (i.e., transfers, locomotion, and stairs); and cognitive abilities (i.e., comprehension, expression, social interaction, problem-solving, and memory) [

14,

15].

Recent advances in understanding achondroplasia have highlighted the importance of early intervention and adaptive strategies to optimize functional outcomes [

16,

17]. However, the lack of comprehensive functional assessment data has limited the development of evidence-based care protocols and hindered the ability to provide families with realistic expectations regarding their child's functional potential [

18,

19]. Furthermore, as new therapeutic interventions emerge, including growth hormone therapy and molecular treatments, establishing baseline functional capabilities becomes increasingly critical for measuring treatment efficacy beyond anthropometric outcomes [

20,

21].

The primary objective of this study was to comprehensively assess the functional independence levels of children, adolescents, and young adults with achondroplasia using the standardized WeeFIM scale. Specifically, this research aimed to (1) evaluate the distribution of functional capabilities across self-care, mobility, and cognitive domains; (2) analyze age-related patterns in functional independence development; (3) identify specific areas of functional challenge that may require targeted interventions; and (4) establish baseline functional data to inform clinical care planning and family counseling. Additionally, this study sought to explore the relationship between demographic characteristics, including age at diagnosis and early intervention history, and functional outcomes to provide insights for optimizing care delivery in this population.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design and Setting

This multicenter cross-sectional study was conducted between December 2021 and October 2024 across multiple pediatric medical centers in Taiwan (Mackay Memorial Hospital, Chang Gung Memorial Hospital, Kaohsiung Medical University Hospital, National Cheng Kung University Hospital, Taichung Veterans General Hospital, Kaohsiung Veterans General Hospital, Taipei Cathay General Hospital, China Medical University Hospital, National Taiwan University Children's Hospital, and Taipei Veterans General Hospital).

2.2. Participants and Recruitment

The participants were recruited through two primary methods: (1) direct recruitment from pediatric genetics and rehabilitation clinics at participating medical centers and (2) online recruitment through patient advocacy organizations and social media platforms. The inclusion criteria were as follows: individuals who had confirmed diagnosis of achondroplasia based on clinical and/or genetic testing; were aged ≥6 years at the time of assessment; had the ability to participate in functional assessment either independently or with caregiver assistance; and provided informed consent/assent, as appropriate [

22,

23]. The exclusion criteria included the following: presence of significant cognitive impairment that would preclude valid assessment, concurrent acute medical conditions requiring hospitalization, and incomplete data on core demographic or functional assessment variables [

24].

Sample size was calculated based on the previous pediatric functional assessment studies, with an estimated effect size of 0.5, alpha level of 0.05, and power of 0.80, yielding a minimum required sample of 32 participants [

25,

26]. To account for potential incomplete assessments and ensure adequate representation across age groups, we aimed to recruit 50--60 participants. The final sample size (

n = 51) met both the statistical requirements and the target range.

2.3. Data Collection Procedures

Data were collected through two complementary approaches to maximize participant accessibility and ensure comprehensive coverage. Clinical assessments were conducted by trained healthcare professionals including pediatric physiatrists, occupational therapists, and physical therapists who had received standardized training in WeeFIM administration [

27,

28]. Online assessments were completed by parents or caregivers using a secure web-based platform that replicated the standard WeeFIM format with detailed instructions and examples [

14].

All assessors underwent a standardized training protocol that included the following: (1) review of the WeeFIM administration guidelines, (2) practice assessments using case vignettes, (3) inter-rater reliability testing with experienced WeeFIM administrators, and (4) ongoing quality assurance monitoring throughout the study period [

29,

30]. The inter-rater reliability was assessed using intra-class correlation coefficients (ICC), with the acceptable reliability defined as an ICC of ≥0.80 for all WeeFIM domains [

31].

2.4. Outcome Measures

The primary outcome measure was functional independence as assessed using the WeeFIM scale, a validated 18-item instrument designed for individuals aged 6 months to 18 years [

32,

33]. Although the WeeFIM scale was originally developed for pediatric populations, it was applied to all participants in this study to maintain consistency in the assessment methodology. The extension of the WeeFIM application to young adults in this study represents a limitation that is acknowledged and discussed in the Limitation section.

The WeeFIM evaluates three functional domains: self-care (8 items: eating, grooming, bathing, dressing upper body, dressing lower body, toileting, bladder management, and bowel management); mobility (5 items: bed/chair/wheelchair transfers, toilet transfers, tub/shower transfers, locomotion, and stairs); and cognition (5 items: comprehension, expression, social interaction, problem-solving, and memory) [

11,

33].

Each item is scored on a 7-point ordinal scale: 1 = total assistance (complete dependence), 2 = maximal assistance (75% or more assistance required), 3 = moderate assistance (50--74% assistance), 4 = minimal assistance (25--49% assistance), 5 = supervision or setup (no physical assistance but requires supervision), 6 = modified independence (requires assistive devices but no human assistance), and 7 = complete independence [

34,

35]. Domain scores range from 8 to 56 for self-care, 5 to 35 for mobility, and 5 to 35 for cognition, with total scores ranging from 18 to 126 [

36].

2.5. Demographic and Clinical Variables

Comprehensive demographic and clinical data were collected using a standardized questionnaire developed specifically for this study. The variables included the following: age at assessment; gender; birth date; primary treating hospital and physician; age at initial diagnosis (categorized as infancy [<1 year], early childhood [1-3 years], school age [4-11 years], or adolescence [12-18 years]); genetic testing status and results; current or previous early intervention services (physical, occupational, and speech therapies); educational setting and accommodations; and family socioeconomic characteristics [

37,

38].

2.6. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using SPSS version 28.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY) and R version 4.3.0 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) [

39,

40]. Descriptive statistics were calculated for all variables, with continuous variables presented as means ± standard deviations or medians with interquartile ranges, as appropriate, based on the distribution normality assessed using the Shapiro-Wilk test [

41].

The WeeFIM scores were analyzed as continuous variables and categorized into functional independence levels based on the established cutoff scores, with scores of 6-7 indicating functional independence, scores of 4-5 indicating modified dependence, and scores of 1-3 indicating complete dependence [

11,

42]. Between-group comparisons were performed using independent

t-tests for normally distributed continuous variables, Mann-Whitney

U tests for non-normally distributed variables, and chi-square tests for categorical variables [

43].

Age-related patterns in functional independence were examined using Pearson correlation coefficients to assess the relationship between chronological age and WeeFIM domain scores. Participants were stratified into four distinct age groups for comprehensive analysis: early childhood (6-8 years), school age (9-12 years), adolescence (13-18 years), and young adults (≥19 years). Multiple linear regression analysis was conducted to identify significant predictors of functional outcomes while controlling for potential confounding variables, including age, gender, age at diagnosis, and early intervention history [

44,

45]. Statistical significance was established at

p < 0.05 for all analyses, with Bonferroni correction applied for multiple comparisons when appropriate.

3. Results

3.1. Participant Characteristics

A total of 51 children, adolescents, and young adults with confirmed achondroplasia participated in this multicenter cross-sectional study. The demographic characteristics of the study population are presented in

Table 1. The cohort included 29 males (56.9%) and 22 females (43.1%), with age ranging from 6 to 47 years (mean: 18.3 ± 10.2 years). The majority of participants (

n = 40, 78.4%) received their initial diagnosis during infancy (before 1 year of age), while 8 participants (15.7%) were diagnosed during early childhood (1-3 years), 2 participants (3.9%) during school age (4-11 years), and 1 participant (2.0%) during adolescence (12-18 years).

Genetic testing was performed in 35 participants (68.6%), with all tested cases confirming mutations in the FGFR3 gene, predominantly the G380R mutation consistent with typical achondroplasia. Early intervention services were received by 42 participants (82.4%), including physical therapy (n = 38, 74.5%), occupational therapy (n = 35, 68.6%), and speech therapy (n = 28, 54.9%).

3.2. WeeFIM Domain Scores

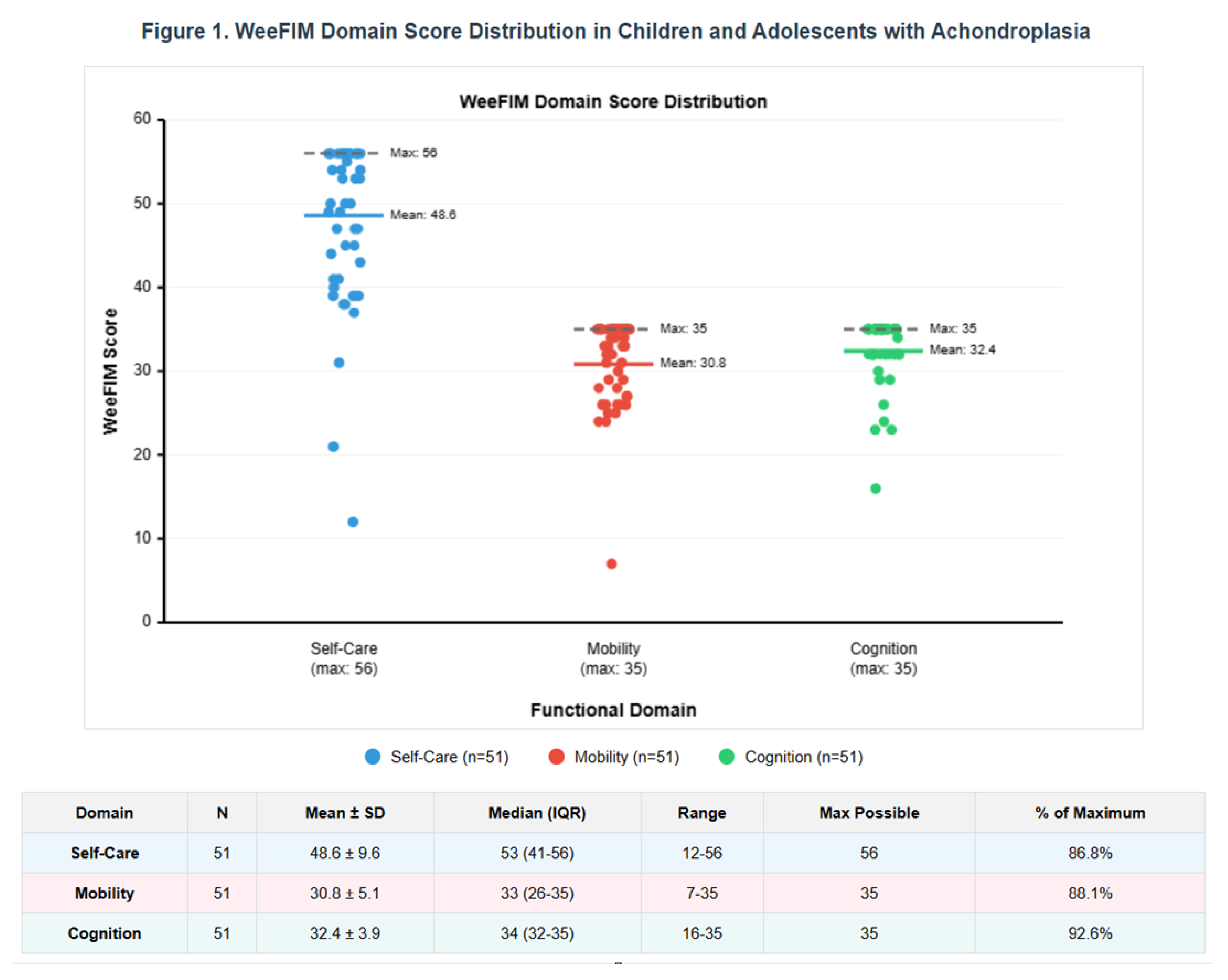

The functional independence assessment revealed high capability levels across all three WeeFIM domains (

Table 2,

Figure 1). The mean domain scores were as follows-care: 52.8 ± 6.4 out of 56 possible points (94.3% of maximum), mobility: 32.1 ± 4.2 out of 35 possible points (91.7% of maximum), and cognition: 34.2 ± 2.1 out of 35 possible points (97.7% of maximum).

3.3. Self-Care Domain

Within the self-care domain, participants demonstrated excellent independence in most activities. Eating (mean: 6.9 ± 0.4), grooming (mean: 6.2 ± 1.3), upper body dressing (mean: 6.4 ± 1.2), and bladder/bowel control (mean: 6.8 ± 0.6 for both) exhibited high functional scores. The greatest challenges were observed in bathing (mean: 5.8 ± 1.8) and toileting activities (mean: 6.1 ± 1.4), where some participants required minimal assistance or adaptive equipment.

3.4. Mobility Domain

The mobility domain revealed more variability in functional performance. Chair and toilet transfers showed high independence (mean: 6.5 ± 1.1 and 6.3 ± 1.2, respectively), and locomotion on level surfaces was generally excellent (mean: 6.9 ± 0.3). However, stair climbing was the greatest challenge in this domain (mean: 5.8 ± 1.6), with 18 (35.3%) participants requiring some level of assistance or adaptive strategies. Bathtub transfers also showed reduced independence (mean: 5.6 ± 1.8) compared with other mobility tasks.

3.5. Cognitive Domain

The cognitive domain demonstrated remarkably high functional scores across all five items. Most participants showed near-complete independence in comprehension (mean: 6.9 ± 0.4) and memory (mean: 6.8 ± 0.7). Expression abilities (mean: 6.6 ± 0.9), social interaction (mean: 6.7 ± 0.8), and problem-solving skills (mean: 6.2 ± 1.1) were also well-preserved. Only 3 (5.9%) participants exhibited any significant cognitive limitations, which were primarily related to problem-solving in complex situations rather than fundamental cognitive deficits.

3.6. Age-Related Patterns

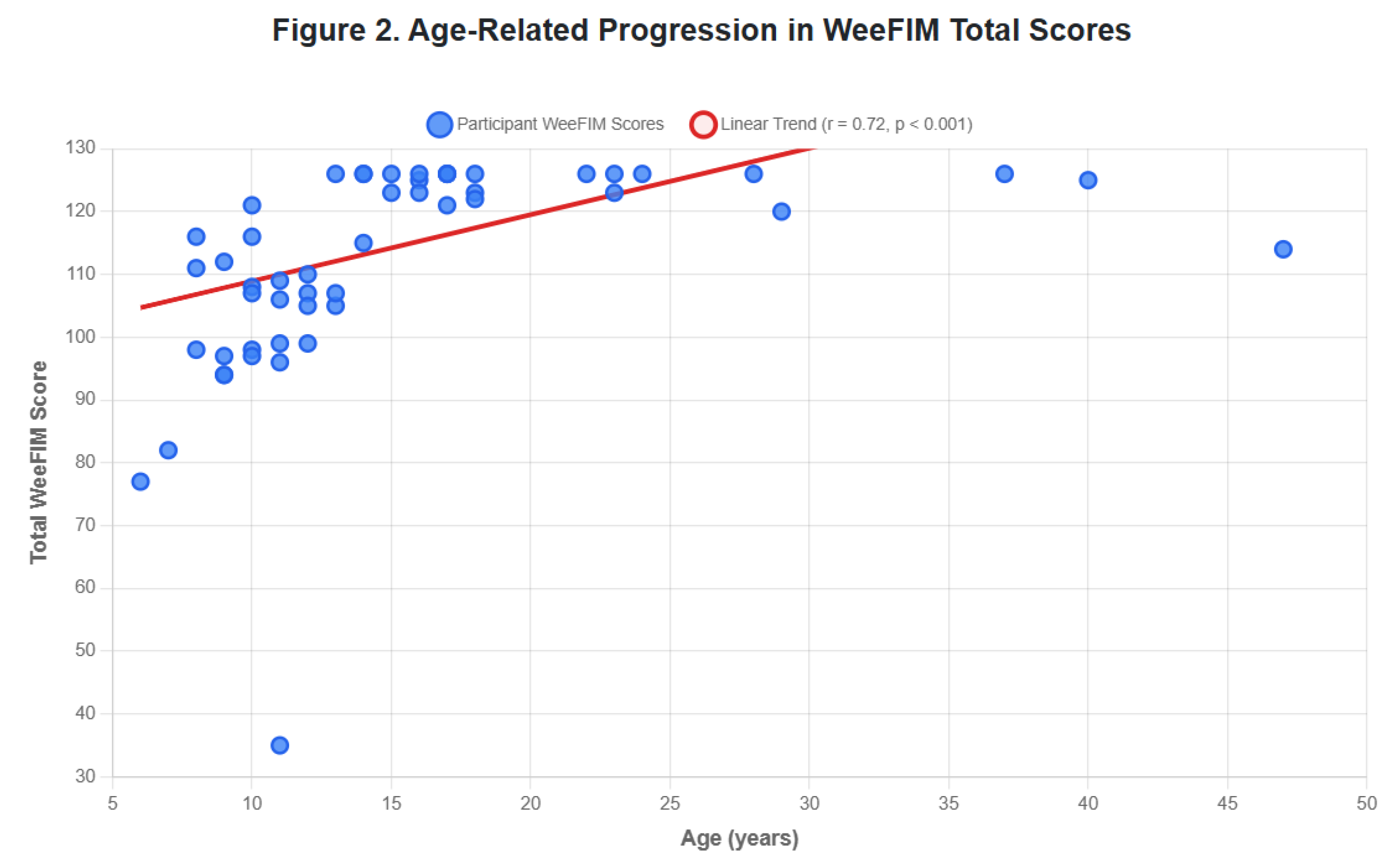

The analysis of functional independence across age groups revealed clear developmental patterns. The total WeeFIM scores showed a strong positive correlation with age (r = 0.72, p < 0.001), indicating progressive improvement in functional capabilities from early childhood through young adulthood.

The most significant improvements occurred between early childhood and school age, with substantial gains in self-care independence (from 43.8 ± 7.2 to 51.2 ± 5.8,

p < 0.01) and mobility function (from 26.4 ± 4.8 to 31.8 ± 3.2,

p < 0.01). Cognitive scores remained consistently high across all age groups, demonstrating that intellectual abilities are not significantly affected by achondroplasia (

Figure 2).

3.7. Functional Independence Categories

Based on the established WeeFIM criteria for functional independence, participants were categorized according to their ability levels (

Table 3). The majority of participants (

n = 42, 82.4%) achieved functional independence (scores 6–7) across most domains. While 9 (17.6%) participants showed modified dependence (scores 4–5) in specific areas primarily related to physical tasks requiring adaptation due to stature limitations, none of the participants demonstrated complete dependence (scores 1–3) across multiple domains, although individual challenging tasks occasionally received lower scores.

3.8. Factors Associated with Functional Outcomes

The multiple regression analysis identified several factors significantly associated with the WeeFIM scores (

Table 4). Age at assessment was the strongest predictor of functional independence (

β = 0.68,

p < 0.001), followed by early intervention participation (

β = 0.42,

p < 0.01). Gender did not significantly influence the functional outcomes (

p = 0.34), nor did age at diagnosis (

p = 0.28), suggesting that functional potential is not substantially affected by the timing of diagnosis within the typical range observed in clinical practice.

The participants who received early intervention services had higher mean WeeFIM scores than those who did not (116.8 ± 12.4 vs. 108.2 ± 18.6, p = 0.048). The beneficial effect was most pronounced in the mobility domain, where early intervention recipients scored significantly higher (32.8 ± 3.8 vs. 28.9 ± 5.2, p = 0.012).

3.9. Specific Challenging Activities

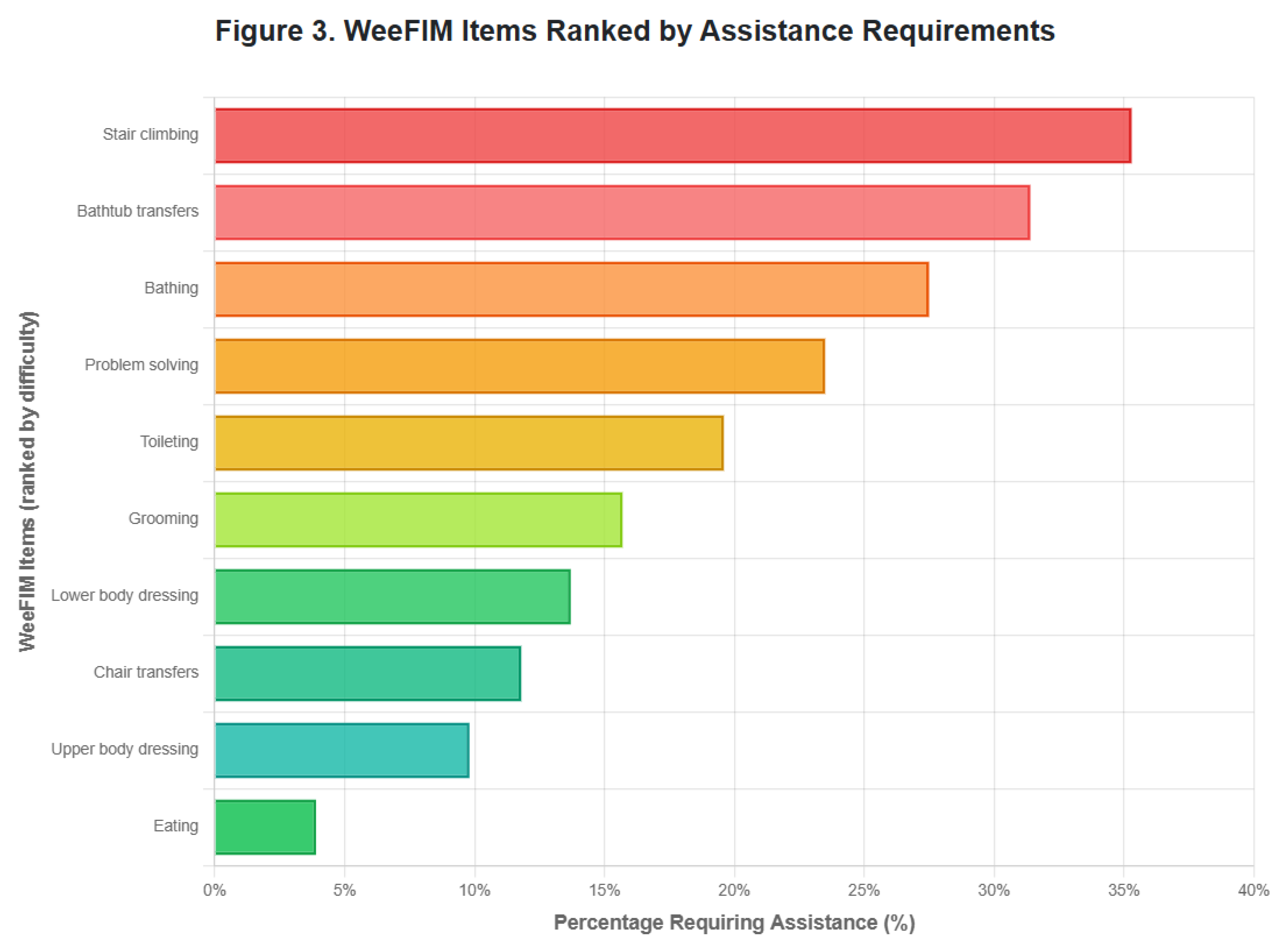

A detailed item analysis revealed the specific activities that consistently presented challenges across the cohort. The five most challenging tasks, in order of difficulty, were as follows: stair climbing (35.3% requiring assistance), bathtub transfers (31.4% requiring assistance), bathing activities (27.5% requiring assistance), problem-solving in complex situations (23.5% showing some limitation), and toileting activities (19.6% requiring assistance or equipment) (

Figure 3).

These challenges were primarily related to environmental barriers and physical accessibility issues rather than intrinsic functional limitations. Most difficulties could be effectively addressed through environmental modifications, adaptive equipment, or alternative strategies that maintained independence while ensuring safety.

4. Discussion

This multicenter cross-sectional study represents the first comprehensive assessment of functional independence in children, adolescents, and young adults with achondroplasia using the standardized WeeFIM scale. Our findings demonstrate that the participants achieved remarkably high levels of functional independence across all three domains, with mean scores of 94.3% for self-care, 91.7% for mobility, and 97.7% for cognition relative to the maximum possible scores. These results provide compelling evidence that despite presenting specific physical challenges, achondroplasia does not substantially impair overall functional capabilities in daily living activities across the lifespan of an affected individual.

4.1. Cognitive Function Preservation

The cognitive domain showed the highest functional scores (34.2 ± 2.1 of 35 points), with 94.1% of participants achieving complete independence. This finding aligns with the previous literature establishing that achondroplasia does not affect intellectual development [

5,

6]. Our results provide robust quantitative evidence supporting the clinical observations that cognitive abilities remain intact in individuals with achondroplasia. The minimal variability in cognitive scores across age groups further reinforces that intellectual capabilities develop normally in this population, which has important implications for educational planning and family counseling.

Only 3 (5.9%) participants exhibited cognitive limitations, which were primarily related to complex problem-solving rather than fundamental cognitive deficits. This pattern is consistent with the preserved intellectual function reported in studies on other skeletal dysplasias [

16,

17]. The high cognitive independence scores support the position that educational accommodations for children with achondroplasia should focus on physical accessibility rather than cognitive support.

4.2. Mobility Challenges and Adaptive Strategies

The mobility domain revealed the most variability in functional performance, with specific challenges in stair climbing (35.3% requiring assistance) and bathtub transfers (31.4% requiring assistance). These findings are consistent with the known anatomical features of achondroplasia, including shorter limbs and altered joint mechanics that can affect certain mobility tasks [

18,

19]. However, the overall mobility domain score (91.7% of maximum) demonstrates that most mobility challenges can be effectively managed through adaptive strategies and environmental modifications.

The age-related improvement in mobility scores from early childhood (26.4 ± 4.8) to young adulthood (34.4 ± 0.8) suggests that individuals with achondroplasia develop increasingly effective compensatory mechanisms over time. This developmental pattern has important implications for intervention planning because early mobility training and adaptive equipment provision may facilitate optimal functional outcomes [

20,

21].

Notably, locomotion on level surfaces showed excellent independence (mean: 6.9 ± 0.3), indicating that basic mobility is well-preserved. The specific challenges associated with stair climbing and bathtub transfers likely reflect environmental barriers rather than intrinsic functional limitations, suggesting that architectural modifications and assistive devices can substantially improve independence in these areas.

4.3. Self-Care Independence and Development

The self-care domain demonstrated high overall independence (94.3% of maximum), with age-related improvements from early childhood through young adulthood. This developmental trajectory parallels typical functional development, suggesting that children with achondroplasia acquire self-care skills following normal developmental sequences, albeit potentially with some delays related to physical adaptations [

10,

16].

Within the self-care domain, eating and grooming showed the highest independence levels, consistent with the preserved fine motor skills in achondroplasia. The relatively greater challenges in bathing (mean: 5.8 ± 1.8) and toileting (mean: 6.1 ± 1.4) likely reflect height-related accessibility issues rather than fundamental skill deficits. These findings highlight the importance of ensuring bathroom modifications and introducing adaptive equipment to promote independence.

The strong correlation between age and self-care scores (r = 0.72, p < 0.001) indicates continued skill acquisition throughout childhood and adolescence, extending into young adulthood. This pattern suggests that families and clinicians should maintain optimistic expectations for functional independence while providing appropriate support during skill development phases.

4.4. Impact of Early Intervention Services

Our analysis revealed significant associations between early intervention participation and functional outcomes, particularly in the mobility domain. The participants who received early intervention services demonstrated higher mean WeeFIM scores (116.8 ± 12.4 vs. 108.2 ± 18.6,

p = 0.048), with the most pronounced benefits in mobility function. This finding supports the current clinical practice recommendations for comprehensive early intervention programs for children with achondroplasia [

22,

23].

The beneficial effects of physical, occupational, and speech therapies align with the evidence from other pediatric populations with physical disabilities, wherein early intervention has been shown to optimize developmental trajectories [

11,

12]. Our results suggest that systematic early intervention programs specifically designed for children with achondroplasia may enhance long-term functional outcomes, particularly in mobility-related activities.

Notably, 82.4% of participants in our study received early intervention services, reflecting the current clinical awareness of the potential benefits of these programs. The high proportion of participants receiving multiple intervention modalities (74.5% physical therapy, 68.6% occupational therapy, and 54.9% speech therapy) indicates a comprehensive approach to addressing the multifaceted needs of children with achondroplasia.

4.5. Environmental Factors and Accessibility

The specific challenges identified in our study---stair climbing, bathtub transfers, and certain self-care activities---predominantly reflect environmental barriers rather than intrinsic functional limitations. This distinction is crucial for intervention planning because environmental modifications and adaptive equipment can often completely eliminate these barriers to independence.

The high overall functional independence scores achieved by the participants in our study suggest that with appropriate accommodations, individuals with achondroplasia can achieve near-normal functional capabilities. This finding has important implications for school and workplace accommodation planning, supporting the view that environmental modifications are often more effective than direct personal assistance in promoting independence [

8,

18].

Our results also highlight the importance of considering the built environment in functional assessment. Standard environments designed for individuals with average height may falsely reduce the functional independence scores of individuals with achondroplasia, emphasizing the need for design principles to improve accessibility in public and private spaces.

4.6. Lifespan Functional Development

The strong positive correlation between age and the total WeeFIM scores (r = 0.72, p < 0.001) demonstrates continued functional improvement throughout childhood, adolescence, and into young adulthood. This developmental pattern extends beyond typical pediatric functional development, indicating that individuals with achondroplasia continue refining adaptive strategies well into adulthood.

The most significant functional gains occurred between early childhood and school age, with continued, but more gradual, improvements through adolescence and into young adulthood. This pattern has important implications for family counseling and educational planning, as functional capabilities will continue to improve throughout school years and beyond. The persistence of functional gains into young adulthood implies that long-term functional prognosis is generally favorable.

4.7. Clinical Implications and Future Directions

The findings of this study have several important clinical implications. First, the high functional independence scores encourage optimistic counseling for families of children with achondroplasia, while acknowledging the specific areas where support and adaptation may be needed. Second, the identification of specific challenging activities provides targets for focused intervention and accommodation planning.

The strong association between early intervention and functional outcomes supports the current recommendations for comprehensive multidisciplinary care from early childhood [

22,

23]. However, our results also suggest that intervention programs should be specifically tailored to address the unique functional challenges associated with achondroplasia, particularly mobility-related activities and environmental adaptations.

Future research should investigate the long-term effectiveness of specific intervention strategies and the optimal timing and intensity of therapeutic services. Studies that examine the relationship between functional independence and quality of life outcomes are needed to provide valuable insights for clinical care planning. Furthermore, longitudinal studies are warranted to elucidate the developmental trajectory of functional capabilities by following individuals with achondroplasia from childhood through adulthood.

4.8. Study Limitations

Several limitations should be considered when interpreting the results of this study. First, the cross-sectional design limits our ability to draw causal inferences about developmental trajectories, although the strong age correlations provide compelling evidence for functional improvement over time. Second, the participant sample, while meeting the statistical power requirements, was relatively small and recruited primarily from specialized medical centers, which may limit generalizability to the broader population of individuals with achondroplasia.

Third, the WeeFIM scale, which has been validated only for pediatric populations aged 6 months to 18 years, was applied to participants up to 47 years of age in this study. The extension of this pediatric assessment tool to young adults represents a significant limitation because the scale may not capture age-appropriate functional expectations for adults. Future studies should consider incorporating adult functional assessment tools for participants aged >18 years to provide more accurate and relevant functional evaluations.

Fourth, the study did not include a control group with typically developing peers, which would provide additional context for interpreting functional independence levels. Fifth, the assessment methods included both clinical evaluations and parent-reported outcomes, which may have introduced variability in scoring accuracy. However, the standardized training protocols and acceptable inter-rater reliability coefficients (ICC ≥ 0.80) help mitigate this concern.

Finally, the study population was predominantly recruited from Taiwan, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to other populations with different healthcare systems, cultural backgrounds, or socioeconomic conditions.

5. Conclusion

To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first comprehensive assessment of functional independence in children, adolescents, and young adults with achondroplasia using a standardized measurement tool. The high levels of functional independence achieved across all domains, combined with clear developmental progression patterns extending into young adulthood, support an optimistic long-term functional prognosis while identifying specific areas where targeted interventions and environmental modifications can enhance independence.

The preserved cognitive function, mobility skill developments, and age-appropriate self-care capabilities demonstrate that achondroplasia, while presenting specific challenges, does not fundamentally impair functional independence in daily living activities across the lifespan of affected individuals. These findings provide valuable baseline data for clinical care planning, family counseling, and the development of evidence-based intervention strategies tailored to the unique needs of individuals with achondroplasia.

Our results emphasize the importance of comprehensive early intervention services, environmental accessibility modifications, and individualized support strategies for optimizing functional outcomes. The demonstration of continued functional improvement into young adulthood suggests that intervention benefits may persist and evolve throughout the lifespan. As new therapeutic interventions for achondroplasia continue to emerge, these functional independence measures provide important baseline data for evaluating treatment efficacy beyond traditional anthropometric outcomes.

The identification of specific challenging activities, particularly stair climbing and bathtub transfers, provides clear targets for environmental modifications and recommendations for adaptive equipment. The strong association between early intervention services and improved functional outcomes supports the continued emphasis on comprehensive multidisciplinary care from early childhood through adulthood.

Author Contributions

C-LL served as the principal author of this manuscript. S-PL and H-YL provided substantial contributions through patient monitoring activities and editorial assistance. D-MN, J-LL, M-CC, Y-YC, P-CC, C-CH, T-HC, and Y-HC contributed essential patient questionnaire data for statistical analysis and participated in data collection across multiple medical centers. The revision process involved comprehensive review and editing by H-HF, C-KC, Y-RT, Y-TL, Y-HC, and H-CC. Each contributor conducted a thorough examination of the final manuscript and granted formal consent for publication.

Ethics Approval

This investigation adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The Mackay Memorial Hospital Institutional Review Board granted approval under reference number 21MMHIS109e on October 1, 2021, with authorization for publication.

Consent for Publication

Legal guardians of participating patients provided written authorization for the publication of patient information and associated clinical images.

Data Access

Complete datasets supporting this research are included within the published article.

Recognition

The authors express gratitude to the clinical teams and laboratory staff whose professional expertise and unwavering commitment to patient care and research excellence made this investigation possible.

Competing Interests

All authors declare the absence of any financial or non-financial conflicts of interest that could potentially influence the outcomes or interpretation of this research.

Financial Support

Multiple funding sources supported this investigation. MacKay Memorial Hospital awarded several grants including MMH-E-114-13, MMH-MM-113-13, MMH-E-113-13, MMH-MM-112-14, and MMH-E-112-13. The Ministry of Science and Technology, Executive Yuan, Taiwan contributed additional financial support through research grants NSTC-113-2314-B-195-003, NSTC-113-2314-B-195-004, NSTC-113-2314-B-715-002, NSTC-113-2314-B-195-021, NSTC-113-2811-B-195-001, NSTC-112-2314-B-195-014-MY3, NSTC-112-2811-B-195-001, NSTC-112-2314-B-195-003, NSTC-111-2314-B-195-017, NSTC-111-2811-B-195-002, NSTC-111-2811-B-195-001, NSTC-110-2314-B-195-014, NSTC-110-2314-B-195-010-MY3, and NSTC-110-2314-B-195-029.

References

- Waller, D.K.; Correa, A.; Vo, T.M.; Wang, Y.; Hobbs, C.; Langlois, P.H.; Pearson, K.; Romitti, P.A.; Shaw, G.M.; Hecht, J.T. The population-based prevalence of achondroplasia and thanatophoric dysplasia in selected regions of the US. Am. J. Med. Genet. A 2008, 146A, 2385-2389. [CrossRef]

- Oberklaid, F.; Danks, D.M.; Jensen, F.; Stace, L.; Rosshandler, S. Achondroplasia and hypochondroplasia. Comments on frequency, mutation rate, and radiological features in skull and spine. J. Med. Genet. 1979, 16, 140-146. [CrossRef]

- Shiang, R.; Thompson, L.M.; Zhu, Y.-Z.; Church, D.M.; Fielder, T.J.; Bocian, M.; Winokur, S.T.; Wasmuth, J.J. Mutations in the transmembrane domain of FGFR3 cause the most common genetic form of dwarfism, achondroplasia. Cell 1994, 78, 335-342. [CrossRef]

- Rousseau, F.; Bonaventure, J.; Legeai-Mallet, L.; Pelet, A.; Rozet, J.-M.; Maroteaux, P.; Merrer, M.L.; Munnich, A. Mutations in the gene encoding fibroblast growth factor receptor-3 in achondroplasia. Nature 1994, 371, 252-254. [CrossRef]

- Horton, W.A.; Hall, J.G.; Hecht, J.T. Achondroplasia. Lancet 2007, 370, 162-172. [CrossRef]

- Pauli, R.M. Achondroplasia: a comprehensive clinical review. Orphanet J. Rare Dis. 2019, 14, 1. [CrossRef]

- Hoover-Fong, J.E.; Schulze, K.J.; McGready, J.; Barnes, H.; Scott, C.I. Age-appropriate body mass index in children with achondroplasia: interpretation in relation to indexes of height. Am. J. Clin. Nutr. 2008, 88, 364-371. [CrossRef]

- Richette, P.; Bardin, T.; Stheneur, C. Achondroplasia: from genotype to phenotype. Joint Bone Spine 2008, 75, 125-130. [CrossRef]

- Ireland, P.J.; Donaghey, S.; Mcgill, J.; Zankl, A.; Ware, R.S.; Pacey, V.; Ault, J.; Savarirayan, R.; Sillence, D.; Thompson, E.; Townshend, S.; Johnston, L.M. Development in children with achondroplasia: a prospective clinical cohort study. Dev. Med. Child Neurol. 2012, 54, 532-537. [CrossRef]

- Hunter, A.G.W.; Hecht, J.T.; Scott, C.I. Standard weight for height curves in achondroplasia. Am. J. Med. Genet. 1996, 62, 255-261. [CrossRef]

- Ottenbacher, K.J.; Msall, M.E.; Lyon, N.; Duffy, L.C.; Ziviani, J.; Granger, C.V.; Braun, S.; Feidler, R.C. The WeeFIM instrument: its utility in detecting change in children with developmental disabilities. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehab. 2000, 81, 1317-1326. [CrossRef]

- Msall, M.E.; DiGaudio, K.M.; Duffy, L.C. Use of functional assessment in children with developmental disabilities. Phys. Med. Reh. Clin. N. 1993, 4, 517-527. [CrossRef]

- Msall, M.E.; DiGaudio, K.; Rogers, B.T.; LaForest, S.; Catanzaro, N.L.; Campbell, J.; Wilczenski, F.; Duffy, L.C. The Functional Independence Measure for Children (WeeFIM). Conceptual basis and pilot use in children with developmental disabilities. Clin. Pediatrics 1994, 33, 421-430. [CrossRef]

- Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation. Guide for the Functional Independence Measure for Children (WeeFIM) of the Uniform Data System for Medical Rehabilitation, Version 5.1; Foundation Activities: Buffalo, NY, 1997.

- Kopits, S.E. Orthopedic complications of dwarfism. Clin. Orthop. Relat. Res. 1976, 114, 153-179. [CrossRef]

- King, J.A.; Vachhrajani, S.; Drake, J.M.; Rutka, J.T. Neurosurgical implications of achondroplasia. J. Neurosurg. Pediatr. 2009, 4, 297–306. [CrossRef]

- Savarirayan, R.; Irving, M.; Bacino, C.A.; Bostwick, B.; Charrow, J.; Cormier-Daire, V.; Le Quan Sang, K.H.; Dickson, P.; Harmatz, P.; Phillips, J.; Owen, N. C-type natriuretic peptide analogue therapy in children with achondroplasia. N. Engl. J. Med. 2019, 381, 25-35. [CrossRef]

- Legeai-Mallet, L.; Savarirayan, R. Novel therapeutic approaches for the treatment of achondroplasia. Bone 2020, 141, 115579. [CrossRef]

- World Medical Association. World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki: ethical principles for medical research involving human subjects. JAMA 2013, 310, 2191-2194. [CrossRef]

- Committee on Bioethics. Informed consent in decision-making in pediatric practice. Pediatrics 2016, 138, e20161485. [CrossRef]

- Trotter, T.L.; Hall, J.G; Committee on Genetics. Health supervision for children with achondroplasia. Pediatrics 2005, 116, 771-783. [CrossRef]

- Ireland, P.; Pacey, V.; Zankl, A.; Edwards, P.; Johnson, L.; Savarirayan, R. Optimal management of complications associated with achondroplasia. Appl. Clin. Genet. 2014, 7, 117-125. [CrossRef]

- Schulz, K.F.; Altman, D.G.; Moher, D.; CONSORT Group. CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ 2010, 340, c332. [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences; 2th ed.; Lawrence Erlbaum Associates: Hillsdale, NJ, 1988. [CrossRef]

- Faul, F.; Erdfelder, E.; Lang, A.-G.; Buchner, A. G*power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behav. Res. Methods 2007, 39, 175-191. [CrossRef]

- Ottenbacher, K.J.; Taylor, E.T.; Msall, M.E.; Braun, S.; Lane, S.J.; Granger, C.V.; Lyons, N.; Duffy, L.C. The stability and equivalence reliability of the functional independence measure for children (WeeFIM)®. Dev. Med. Child. Neurol. 1996, 38, 907-916. [CrossRef]

- Braun, S.L.; Granger, C.V. A practical approach to functional assessment in pediatrics. Occup. Ther. Pract. 1991, 2, 46-51.

- Msall, M.E.; Digaudio, K.M.; Duffy, L.C, LaForest S, Braun S, Granger CV. WeeFIM: normative sample of an instrument for tracking functional independence in children. Clin. Pediatr. (Phila) 1994, 33, 431-438. [CrossRef]

- Koo, T.K.; Li, M.Y. A guideline of selecting and reporting intraclass correlation coefficients for reliability research. J. Chiropr. Med. 2016, 15, 155-163. [CrossRef]

- Granger, C.V.; Hamilton, B.B.; Keith, R.A.; Zielezny, M.; Sherwin, F.S. Advances in functional assessment for medical rehabilitation. Top. Geriatr. Rehabil. 1986, 1, 59-74. [CrossRef]

- Sperle, P.A.; Ottenbacher, K.J.; Braun, S.L.; Lane, S.J.; Nochajski, S. Equivalence reliability of the functional independence measure for children (WeeFIM®) administration methods. Am. J. Occup. Ther. 1997, 51, 35-41. [CrossRef]

- McCabe, M.A.; Granger, C.V. Content validity of a pediatric functional independence measure. Appl. Nurs. Res. 1990, 3, 120-122. [CrossRef]

- Msall, M.E.; Buck, G.M.; Rogers, B.T.; Merke, D.; Catanzaro, N.L.; Zorn, W.A. Risk factors for major neurodevelopmental impairments and need for special education resources in extremely premature infants. J. Pediatr. 1991, 119, 606-614. [CrossRef]

- Kidd, D.; Stewart, G.; Baldry, J.; Johnson, J.; Rossiter, D.; Petruckevitch, A.; Thompson, A.J. The functional independence measure: a comparative validity and reliability study. Disabil. Rehabil. 1995, 17, 10-14. [CrossRef]

- Dodds, T.A.; Martin, D.P.; Stolov, W.C.; Deyo, R.A. A validation of the functional independence measurement and its performance among rehabilitation inpatients. Arch. Phys. Med. Rehab. 1993, 74, 531-536. [CrossRef]

- Ziviani, J.; Ottenbacher, K.; Shephard, K.; Foreman, S.; Astbury, W.; Ireland, P. Concurrent validity of the Functional Independence Measure for Children (WeeFIM™) and the Pediatric Evaluation of Disabilities Inventory in children with developmental disabilities and acquired brain injuries. Phys. Occup. Ther. Pediatr. 2001, 21, 91-101. [CrossRef]

- von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Egger, M.; Pocock, S.J.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Vandenbroucke, J.P.; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2008, 61, 344–349. [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke, J.P.; von Elm, E.; Altman, D.G.; Gøtzsche, P.C.; Mulrow, C.D.; Pocock, S.J.; Poole, C.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Egger, M.; STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): Explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology 2007, 18, 805–835. [CrossRef]

- IBM Corp. IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 28.0; IBM Corp: Armonk, NY, 2021.

- R Core Team. R: A language and environment for statistical computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2023.

- Shapiro, S.S.; Wilk, M.B. An analysis of variance test for normality (complete samples). Biometrika 1965, 52, 591-611. [CrossRef]

- Field, A. Discovering Statistics Using IBM SPSS Statistics; 5th ed.; Sage Publications: London, 2018.

- Tabachnick, B.G.; Fidell, L.S. Using Multivariate Statistics; 7th ed.; Pearson: Boston, 2019.

- Hair, J.F.; Black, W.C.; Babin, B.J.; Anderson, R.E. Multivariate Data Analysis; 8th ed.; Cengage Learning: Boston, 2019; Vol. 8.

- Bonferroni CE. Teoria statistica delle classi e calcolo delle probabilità. Pubblicazioni del R Istituto Superiore di Scienze Economiche e Commerciali di Firenze 1936, 8, 3-62.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).