1. Introduction

The population aging, increased life expectancy, and the rising prevalence of non-communicable diseases have significantly contributed to the growing burden of disability worldwide, and more so in lower middle-income countries and emergent economies [1-2]. Worldwide analyses of data from the Global Burden of Disease study have estimated that about 2.4 billion people worldwide have a health condition that would benefit from rehabilitation [

1]. Those worldwide rehabilitation needs have been growing between 66 to 69% since 1990 in absolute values (i.e. accounting for population growth) but also per capita: by 17% since 1990 [2-3]. More importantly, upper middle-income countries have been the income-level group with the greatest increase in rehabilitation needs per capita (29.9%), about twice as much of the growth observed in either lower middle-income or high-income nations: 17.7 and 15.6%, respectively [

2].

A growing burden of disability requires the strengthening of rehabilitation services in health systems, especially where the supply is lower and the growths in needs are more pronounced [4-7]. Aligned with International Classification of Functioning, Disability and Health, rehabilitation entails interventions aimed at optimizing the functionality of individuals with health conditions that originate functional impairments, reducing their disability in interaction with the environment [

4,

5]. Hence, rehabilitation services enable people with disabilities to live, work, and learn, and be full and participants members of their society [4-5,8-9]. Rehabilitation services can target a range of disabilities, from transitional to long-term, and across the lifespan [1,10-11], being increasingly considered an essential health service to be part of an universal health coverage [

12].

Brazil is a large upper-middle income, home to 203 million people, and according to the World Bank, with GDP per capita of US

$9,032 in 2023, yet with this GDP having a yearly percent growth that ranged from -4% to 12% from 1990 to 2023. Brazil also has a large landmass of 8.5 million km

2. Brazil is comprised of the union (federal government), 27 states – part of 5 larger regions, and over 5,500 municipalities. While Brazil is highly diverse, systemic inequalities persist – including territorial - that limit the opportunities of many individuals who live in poverty and with poor health and disability [

13]. Subsequently, regional disparities exist in health indicators [

14]. These disparities also exist in the distribution of rehabilitation resources such as the rehabilitation workforce. For instance, the Southwestern region (e.g. encompassing Sao Paulo, Rio de Janeiro, and Minas Gerais as large metropolitan areas) had the highest densities in all rehabilitation professions in 2020, contrasting with the North, Northeast and Central West which have lower population density and income level [

15].

Geographic inequities in access to rehabilitation resources are not exclusive of Brazil or developing nations. Even in high-income nations, individuals with disabilities living in the least developed regions or more rural or remote areas have poorer access to rehabilitation resources[16-17] among other geographic-based disability disparities [17-18]. Lower access to rehabilitation services put people with disabilities at risk of not attaining the same level of health and functioning compared those who can better access to rehabilitation resources [17,19-21]. In Brazil, persistent inequalities have been identified in health-service resources, access, and utilization, experienced by the population with lower socio-economic status and those that live in regions with lower population density, especially in the North [22-25].

Overall, in low and middle-income countries, a key factor undermining the integration of rehabilitation in the policy development agendas is the lack of a documented problem definition [26-27]. While in Brazil there is now up-to-date documentation of regional inequalities in the rehabilitation human resources[

15], we have no cross-regional data on rehabilitation needs and their evolution over time to more fully access a supply-need disparity.

The data from Global Burden of Disease (GBD) study have been used to determine rehabilitation needs worldwide and across countries[1-2]. However, these data were not used before to map the population rehabilitation needs within Brazil, nor aligned with the Brazilian’s public-based Care Network for People with Disabilities (CNPD)[

28]. Specifically, the CNPD frames the services for people with disabilities according to five impairment types: physical, auditory, visual, intellectual, and multiple impairments [

28]. In this context, here we aim to use data from the GBD study to:

Determine the Brazil’s global burden of disability amenable to rehabilitation, per capita and adjusted for population ageing, their evolution since 1990, and the distribution by the five pre-established impairment categories.

Identify how these values vary by a) key age groups, and b) the five major Brazilian regions.

2. Materials and Methods

Design: This study refers to a country-specific and within-country secondary analysis of the GBD 2019, the largest meta-study of global epidemiological data previously used to determine rehabilitation needs worldwide [1-2].

Setting: Our analysis is focused on Brazil as a nation first, and then across five main regions.

Figure 1 provide a map of the five Brazilian regions and the respective states within. About 40% of the Brazilian population lives in Sao Paulo, Minas Gerais and Rio de Janeiro, all part of the Southeast region which, in total, has 91.8 inhabitants per km

2. As opposites, the Center West contains the lowest percentage (8%) of the population and the North has the lowest density (4.5 inhabitants per km

2 and over 45% of the landmass) [

13,

29].

In turn, in both the North and Northeast, 30-40% of the population live below the poverty line, nearly twice as much as in other regions and with average income levels of about half of the three other regions [

13,

29].

Health Conditions: While informed by previous usages of the GBD data for rehabilitation-needs assessments [1-2], the health conditions from which to extract data were adapted to reflect the five impairment categories of the Brazilian CNPD. The largest category of impairments (i.e., “physical”) was subdivided into four subcategories: musculoskeletal, neurological, cardiothoracic and other physical health conditions. In turn, “multiple impairments”, here referring to early-onset conditions which can result in various impairment types, were also subdivided into congenital (i.e., present at birth) and neonatal (i.e., occurring during the first days of life) subcategories.

Table 1 provides a detailed structure of the health conditions in the GBD from which we extracted data for Brazil and its regions.

(i.e

Among the GBD measures, we extracted data only for Years Lived with Disability (

YLDs), for each health condition in table 1. The YLDs provides the overall, non-fatal impact of a health condition and consists of the number of years lived with any short-term or long-term sequelae of a health condition. Importantly, YLDs are also weighted for severity and disability weights; using stroke as an example, their disability weights range from 0.019 for mild consequences to 0.588 for severe consequences that include cognition impairments [

30]. Because rehabilitation conditions with greater severity and disability may require more intensive rehabilitation services, YLDs can be a better indicator of rehabilitation need than for example its underlying prevalence values. For the YLDs measure, we extracted data for the “

rate” (per 100,000 people) metric. For the “age” we extracted YLDs for “

all ages” and “

age-standardized” rates, in addition to three stratified age groups: 0-9 years; 10-54, and 55+. All that data extraction was done for Brazil overall and for each of its five main regions, for both 1990 and 2019. Finally, we extracted data for the “total percentage change” of the YLD values for the year range 1990-2021.

Data Computation and Synthesis

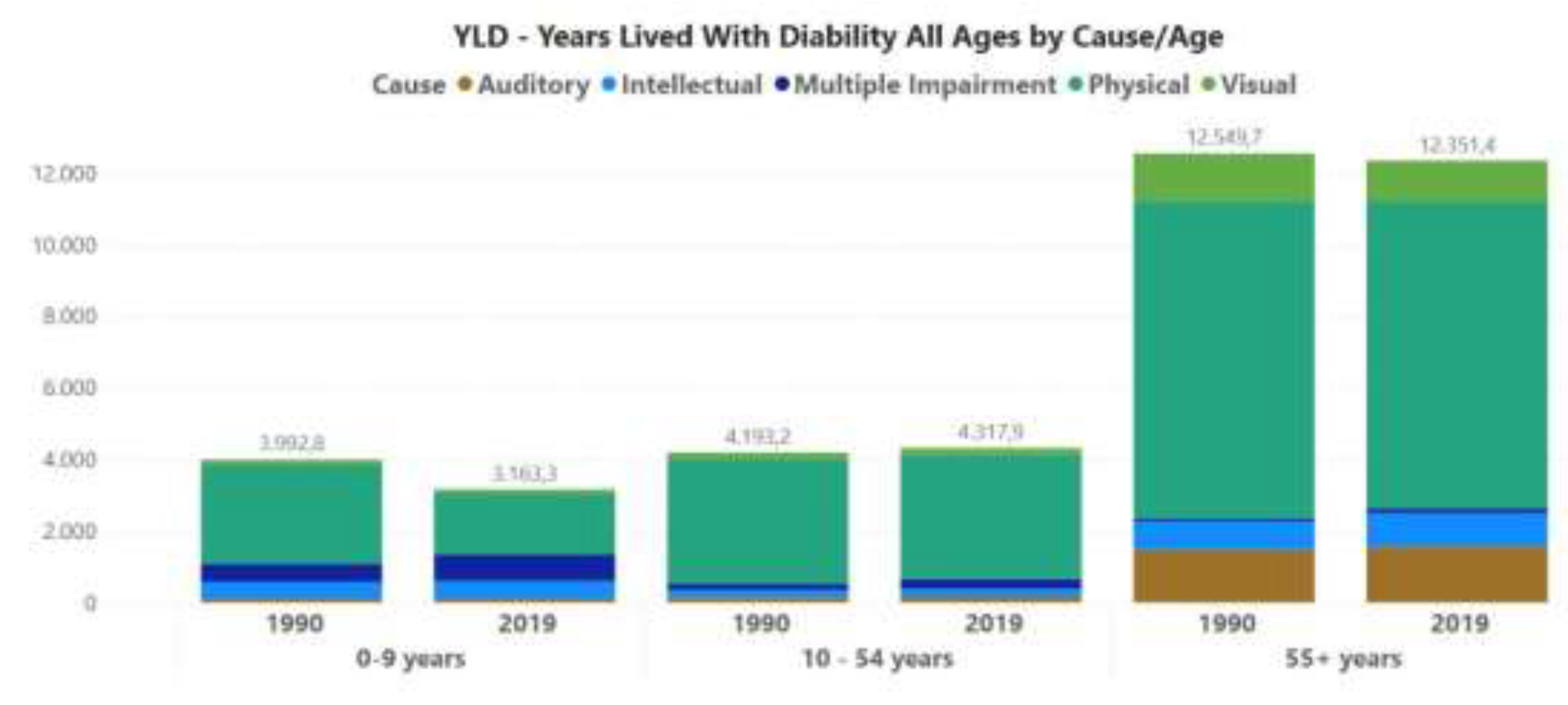

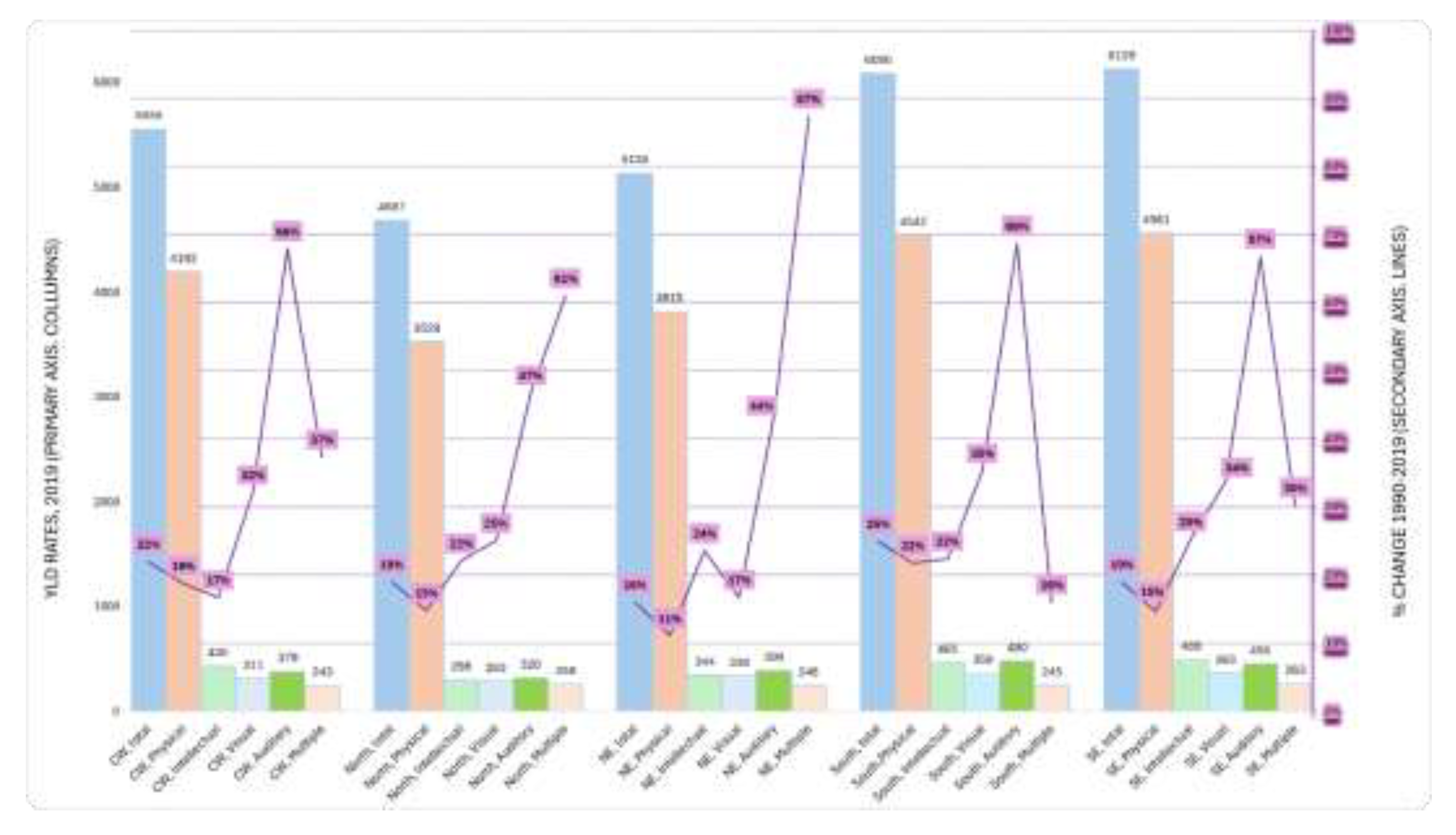

With the data above extracted to Excel spreadsheets, for each health condition in table 1, we computed the summed estimates for each subcategory and main category in table 1. That applied to both 1990 and 2019, and for each of the six geographies addressed. Also, with the extracted measures and metrics, we were able to create two variables: YLD Rates and Age-standardized YLD Rates; the former being the primary indicator of rehabilitation need, the latter being used to interpret any growth over time as being the result of (i.e. adjusted for) the population ageing. Percentage changes for (sub)categories of health conditions were computed using the summed estimates for both 2019 and 1990. The Brazil-wide results were tabulated using the structure of the table 1. Finally, we developed bar charts for displaying the distribution of the a) YLD Rates in Brazil per three main age groups, and b) YLD Rates per the five main regions of Brazil, for total values as well as stratified per each of the five main health conditions.

3. Results

In our results, we respond to each questions of our study.

- 1)

Brazil-wide rehabilitation needs, including stratified per main condition groups

Table 2 shows that the primary indicator of rehabilitation need (YLD Rates, All Ages) have increased by 24% from 1990 to 2019, with over 77% of these YLD rates in 2019 (i.e., 3847 out of 4986) coming from “physical” impairments alone. In turn, 69% of the “physical” impairments in 2019 (i.e., 2657 out of 3847 YLD rates) come from musculoskeletal conditions. In turn, the groups of conditions that had important percentage improvements since 1990 were the: neonatal, the general musculoskeletal and pain conditions, and the cardiac ones.

Among individual conditions (see supplementary table 1), some conditions associated with ageing such as Alzheimer's disease and other dementias, Parkison’s disease, and Hypertensive heart disease were among those that more than doubled their YLD rates from 1990 to 2019 in Brazil. Not surprisingly, supplementary table 1 shows a negative growth in the YLD rates for communicable neurological conditions and for pulmonary conditions- many of them (e.g., tuberculosis) are communicable too.

Table 2 also shows the findings for Age-standardized YLD Rates (i.e., discounting the population aging), which show frequent negative growth, which emphasizes that the growth in YLD Rates (i.e. per 100,000 population) have been essentially driven by the population ageing.

- 2a)

Distribution by age groups

Figure 2 provides the YLD Rates (all ages) for the whole Brazil distributed by three age groups, including as stratified per impairment type, and for both 1990 and 2019. In 2019, most YLDs 62% come from the population over 55 years, with close to the same amount for 1990 and 2019 in the population 55+ years as well as 10-54 years. On the other hand, there is a decrease of YLD Rates (3992.78 to 3163.32; -21%) in the 0-9 age group.

- 2b)

Distribution by regions

Figure 3 provides the distribution of the Brazilian YLD Rates per its five main regions and impairment types, including the 2019 values (primary axis) the percent change 1990-2019 (secondary axis). Most strikingly, percent growth in the YLD rates occurred in all five regions for all the condition types, ranging from 11% for “physical” impairments to 87 percent for “multiple impairments” both in the Northeast. Overall, the “multiple impairments” were growing much higher in both the Northeast and North than in other more developed regions (e.g. 30% and 16% respectively for the South and Southeast).

The North, one underdeveloped as well as low population density, experienced an overall 19% growth in YLD rates between 1990 and 2019, the same growth of the most developed and densely populated Southeast region, but out of lower values in 1990 (3923 vs 5114 YLD Rates). Per impairment type, the more developed South and Southeast vs the North and Northeast region had a patter of having higher YLD Rates in 2019 especially for “physical”, “intellectual”, and “auditory” impairments.

4. Discussion

This study is the first to analyze the rehabilitation needs for Brazil, including across age groups, its five main regions, from 1990 to 2019, and as stratified by impairment types. The latter reflected the organization of the Brazilian’s CNPD toward informing health-service planning for people with disabilities within the public health system. The results, derived from the GBD (i.e., the largest global epidemiological study) showed a Brazil-wide 24% growth (1990-2019) in overall rehabilitation needs per capita (i.e., YLD rates), aligned with the global trend for upper middle-income countries [1-2]. Importantly, the study also highlighted the population ageing as a key driver of increased rehabilitation needs, since growth rates for age-standardized YLD rates were often negative despite the large increases per capita. As the Brazilian population 65 or older is expected to more than double until 2050 [

31], rehabilitation needs (i.e. YLD rates) might growth even further in the future.

Historically, in Brazil, premature death resulting in lower life expectancy has been a greater issue in the north and northeast regions than in the south and southeast [

14]. That may be part of the reason why YLD rates here were lower in both 1990 and 2019 for the North and Northeast. Yet, the growing trend has been similar across regions. Although with a partial time lag across regions, our data corroborates the notion that the Brazil, as a whole, has undergone a so-called epidemiological transition; that comes from an increasing life expectancy largely attributable to declines in communicable diseases occurring alongside an increased burden of non-communicable and chronic diseases [

14]. As non-communicable diseases have been associated with YLDs [

2,

32], it was not surprising to find here that rehabilitation needs per capita were growing all across Brazil’s regions.

The category of physical impairments was by far the one contributing more for the overall rehabilitation needs, Brazil-wide or stratified by either regions or age groups. Analyses of rehabilitation needs stratified by condition or impairment type are important for health systems and service planners who need to allocate resources to different service types [

5]. Although some rehabilitation services can be more “horizontal”, i.e., serving a range of rehabilitation needs across impairments especially in the home, community-based or primary care, there are also care levels (e.g., inpatient rehabilitation) that target more specific populations and impairments [

33]. Our data can be especially relevant for that level of planning, especially as the data is stratified per impairment types - which reflect the Brazilian’s CNPD [

28]. Regarding the human resources, for example physical therapists are more likely to be necessary for addressing physical versus intellectual impairments; hence, our results are informative for that level of planning too, especially when combined with workforce supply data for Brazil-wide or across its regions.

With the latter regards, a recent study from Sixel et al found that density of rehabilitation professionals working for the public-based Unified Health System has been either declining or stabilizing in the more recent years, likely because of some recent changes in policy and funding [

15]. Those policies may impede the rehabilitation services and workforce to keep up with the growing population needs for rehabilitation, as shown in our study. Moreover, Sixel et al found that the regions with lower density of those rehabilitation professionals were typically in the North or Northeast; and those findings do not account for those professionals working in private practice or with private and insurance-based reimbursement likely more prevalence in the South and Southeast [

15] As the North and Northeast regions have lower income and rates of private insurance [

22], one can hypothesize that the regional disparity in the total rehabilitation workforce supply is much larger than that for the Unified Health System alone. That can be a matter of equity concern as the rehabilitation in the North and Northeast areas are also growing, often at similar levels to other Brazilian regions, as here shown. Furthermore, rehabilitation needs in the North and Northeast regions are expected to grow further as part of an epidemiological transition that has been occurring Brazil wide [

14]. For instance, as the life expectancy increases in both the North and Northeast, including as a result of life-saving healthcare advances, the rates of physical, intellectual/cognitive, and auditory impairments, all of them highly associated with a population ageing [

32], are likely to approach those of the more developed Brazilian regions.

The case of the Brazil’s North region can be especially complex to handle for the equitable population access to needed rehabilitation resources. In addition to having low-income indicators, the region’s landmass is substantive includes the Amazon rainforest), while the population density the lowest among Brazil’s main regions [

13,

29]. That occurs at the backdrop of underdeveloped infrastructures for both transportation and internet connectivity. All these characteristics are ecological risks that are known to negatively affect the access to rehabilitation services for the populations in need [34-36]. Known solutions to provide rehabilitation care to rural and remote populations especially in high-income nations (e.g. telerehabilitation, outreach programs or mobile units) [37-40] may be more complex to implement in the less developed and less densely populated areas of the North of Brazil, with its unique socio-demographic, socio-economic, and infrastructure profile (e.g., suboptimal roads or transportation facilities). Rehabilitation services integrated into local primary care services can be one solution [

41], but requires workforce availability, recruitment and retention in those remote areas; that is also are known to also be complex [35-36].

All accounted, there is a need for an integrated, purposeful approach, and explicit public policies to facilitate that the growing rehabilitation needs Brazil-wide, but especially those in underserviced and remote locations, which need equity-oriented responses. Failure to do so can exacerbate the known and vicious cycle among poverty and disability especially in lower-income contexts [

42].

Finally, lack of equitable access to rehabilitation may also contribute to increase the burden of disability in Brazil, especially their underserviced regions. For example, a preventable or transitional disability arising from an acute or chronic condition can be transformed into long-term, chronic, and more severe health condition or disability by lack of access to quality rehabilitation treatment, either timely or at all [

43]. In that sense, future research might investigate whether greater or lower access to rehabilitation resources across Brazilian regions affect their comparitive burden of disability.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, it uses YLD rates as a proxy estimator of rehabilitation needs; while this is likely the best proximal indicator from the GBD study and often used to estimate large-scale rehabilitation needs [1-2], it is not the theoretical ideal, functional-based indicator of rehabilitation need. Second, this study uses data from the GBD 2019 (extraction occurred in late 2023), while the subsequent iteration (GBD 2021) was launched in 2024; hence, we only provide data until 2019. However, previous analyses have shown that overall rehabilitation needs have growth linearly over time and have not significantly changed in the growth pattern with the use of an updated cycle [2-3]. Third, we did not analyze the multiple datapoints between 1990 and 2019, including with linear regressions, partly because of the previously identified linear growth trends worldwide and in upper middle-income countries [

1]. Finally, we analyze the rehabilitation needs across five Brazilian regions, not at the more state level, for a more parsimonious initial approach. Subsequent studies, including for matching rehabilitation need with supply, may be more granular (e.g., at the state level).

5. Conclusions

Rehabilitation needs are growing Brazil-wide and across its regions, especially as a result of the increased life expectancy, population ageing, and epidemiological transition that is expected to have a continued or accelerated growth in the upcoming decades. An explicit, databased, needs-focused, equity-oriented health-systems and human-resources policy and planning might be developed for addressing the growing burden of disability across Brazil. The data here identified, especially when combined with workforce data, can be instrumental for that. Finally, Brazil’s regions whose (remote) populations can experience greater risks of not accessing needed rehabilitation care, such as in the North region, may require regional-specific planning and both workforce strengthening and service-delivery alternatives - toward assuring their growing rehabilitation needs are equitably met.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Rogério Olmedija de Araújo; Methodology, Rogério Olmedija de Araújo, Tiótrefis Gomes Fernandes and Tiago Silva Jesus; Writing – original draft, Rogério Olmedija de Araújo; Writing – review & editing, Tiótrefis Gomes Fernandes and Tiago Silva Jesus; Supervision, Tiago Silva Jesus.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data is in the public domain.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to express their gratitude to “Coordenação de Aperfeiçoamento de Pessoal (CAPES)” and the support given for the “Universiade Federal do Amazonas”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Cieza, K. Causey, K. Kamenov, S. W. Hanson, S. Chatterji, and T. Vos, “Global estimates of the need for rehabilitation based on the Global Burden of Disease study 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019,” Lancet, vol. 396, no. 10267, pp. 2006–2017, 2020. [CrossRef]

- T. S. Jesus, M. D. Landry, and H. Hoenig, “Global need for physical rehabilitation: Systematic analysis from the global burden of disease study 2017,” Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health, vol. 16, no. 6, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. S. Jesus and M. D. Landry, “Global need: including rehabilitation in health system strengthening,” Lancet, vol. 397, no. 10275, pp. 665–666, 2021. [CrossRef]

- K. Kamenov, J. A. Mills, S. Chatterji, and A. Cieza, “Needs and unmet needs for rehabilitation services: a scoping review,” Disabil. Rehabil., vol. 41, no. 10, pp. 1227–1237, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. S. Jesus, M. D. Landry, D. Brooks, and H. Hoenig, “Physical Rehabilitation Needs Per Condition Type: Results From the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017,” Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil., vol. 101, no. 6, pp. 960–968, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Abbafati et al., “Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019,” Lancet, vol. 396, no. 10258, pp. 1204–1222, 2020. [CrossRef]

- Q. Louw, K. Grimmer, K. Berner, T. Conradie, D. T. Bedada, and T. S. Jesus, “Towards a needs-based design of the physical rehabilitation workforce in South Africa: trend analysis [1990–2017] and a 5-year forecasting for the most impactful health conditions based on global burden of disease estimates,” BMC Public Health, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 1–12, 2021. [CrossRef]

- H. Bouziri, Y. Roquelaure, A. Descatha, W. Dab, and K. Jean, “Temporal and spatial distribution of musculoskeletal disorders from 1990 to 2019: a systematic analysis of the global burden of disease,” BMJ Public Heal., vol. 1, no. 1, p. e000353, 2023. [CrossRef]

- M. Hassan et al., “Situation analysis of rehabilitation services for persons with disabilities in Bangladesh : identifying service gaps and scopes for improvement,” Disabil. Rehabil., vol. 0, no. 0, pp. 1–14, 2021. [CrossRef]

- O’Young, J. Gosney, and C. Ahn, “The Concept and Epidemiology of Disability,” Phys. Med. Rehabil. Clin. N. Am., vol. 30, no. 4, pp. 697–707, 2019. [CrossRef]

- J. Bickenbach, C. Sabariego, and G. Stucki, “Beneficiaries of Rehabilitation,” Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil., vol. 102, no. 3, pp. 543–548, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Cieza, B. Mikkelsen, and A. Ghaffar, “Advancing rehabilitation through health policy and systems research,” Bull. World Health Organ., vol. 100, no. 11, pp. 655-655A, 2022. [CrossRef]

- “Brazil Overview: Development news, research, data.” https://www.worldbank.org/en/country/brazil/overview (accessed Nov. 21, 2024).

- F. Marinho et al., “Burden of disease in Brazil, 1990–2016: a systematic subnational analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016,” Lancet, vol. 392, no. 10149, pp. 760–775, 2018. [CrossRef]

- T. R. dos Santos Sixel, D. Bernardo, A. de Almeida Medeiros, A. Bousquat, P. H. dos Santos Mota, and A. C. B. Schmitt, “The rehabilitation workforce in Brazil,” Arch. Public Heal., vol. 82, no. 1, pp. 1–10, 2024. [CrossRef]

- J. R. Falvey, T. E. Murphy, T. M. Gill, J. E. Stevens-Lapsley, and L. E. Ferrante, “Home Health Rehabilitation Utilization Among Medicare Beneficiaries Following Critical Illness,” J. Am. Geriatr. Soc., vol. 68, no. 7, pp. 1512–1519, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. Kosar, L. Loomer, N. B. Ferdows, A. N. Trivedi, O. A. Panagiotou, and M. Rahman, “Assessment of Rural-Urban Differences in Postacute Care Utilization and Outcomes among Older US Adults,” JAMA Netw. Open, vol. 3, no. 1, pp. 1–12, 2020. [CrossRef]

- G. Zhao, C. A. Okoro, J. Hsia, W. S. Garvin, and M. Town, “Prevalence of Disability and Disability Types by Urban–Rural County Classification—U.S., 2016,” Am. J. Prev. Med., vol. 57, no. 6, pp. 749–756, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. M. Mroz, A. Meadow, E. Colantuoni, B. Leff, and J. L. Wolff, “Home Health Agency Characteristics and Quality Outcomes for Medicare Beneficiaries With Rehabilitation-Sensitive Conditions,” Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil., vol. 99, no. 6, pp. 1090-1098.e4, 2018. [CrossRef]

- D. Quigley et al., “Systematic Review of Rural and Urban Differences in Care Provided by Home Health Agencies in the United States,” J. Am. Med. Dir. Assoc., vol. 23, no. 10, pp. 1653.e1-1653.e13, 2022. [CrossRef]

- Hong et al., “Comparison of Functional Status Improvements among Patients with Stroke Receiving Postacute Care in Inpatient Rehabilitation vs Skilled Nursing Facilities,” JAMA Netw. Open, vol. 2, no. 12, 2019. [CrossRef]

- M. Coube, Z. Nikoloski, M. Mrejen, and E. Mossialos, “Persistent inequalities in health care services utilisation in Brazil (1998–2019),” Int. J. Equity Health, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 1–15, 2023. [CrossRef]

- V. I. A. Miranda, A. A. Schäfer, C. D. Tomasi, J. Soratto, F. de Oliveira Meller, and M. P. T. Silveira, “‘Inequalities in access to medicines for diabetes and hypertension across the capitals in different regions of Brazil: a population-based study,’” BMC Public Health, vol. 21, no. 1, pp. 1–8, 2021. [CrossRef]

- L. Garnelo, R. C. P. Parente, M. L. R. Puchiarelli, P. C. Correia, M. V. Torres, and F. J. Herkrath, “Barriers to access and organization of primary health care services for rural riverside populations in the Amazon,” Int. J. Equity Health, vol. 19, no. 1, pp. 1–14, 2020. [CrossRef]

- M. A. Dos Santos, L. M. Triaca, and C. A. O. Tejaba, “Evolution of inequalities in health care use among older people in Brazil: Evidence for the period 1998–2019,” J. Econ. Ageing, vol. 20, 2021.

- R. Neill et al., “Prioritizing rehabilitation in low- and middle-income country national health systems: a qualitative thematic synthesis and development of a policy framework,” Int. J. Equity Health, vol. 22, no. 1, pp. 1–17, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Neill et al., “Generating Political Priority for the Health Needs of the 21st Century: A Qualitative Policy Analysis on the Prioritization of Rehabilitation Services in Uganda,” Int. J. Heal. policy Manag., vol. 13, p. 8347, 2024. [CrossRef]

- S. Q. S. Ribeiro, A. de A. Medeiros, and S. L. A. da Silva, Redecin Brasil: o cuidado na Rede de Atenção à Pessoa com Deficiência nos diferentes Brasis, 1a edição. Porto Alegre: Rede Unida, 2022.

- “Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística - IBGE - Projeções da população.” https://www.ibge.gov.br/estatisticas/sociais/populacao/9109-projecao-da-populacao.html?edicao=41053 (accessed Nov. 25, 2024).

- A. Salomon et al., “Disability weights for the Global Burden of Disease 2013 study,” Lancet Glob. Heal., vol. 3, no. 11, pp. e712–e723, 2015. [CrossRef]

- “Health data overview for the Federative Republic of Brazil.” https://data.who.int/countries/076 (accessed Nov. 26, 2024).

- S. Chatterji, J. Byles, D. Cutler, T. Seeman, and E. Verdes, “Health, functioning, and disability in older adults - Present status and future implications,” Lancet, vol. 385, no. 9967, pp. 563–575, 2015. [CrossRef]

- C. Kiekens and K. H. E. Peers, “5.1 Physical and Rehabilitation Medicine in Health-Care Systems: Basic Concepts, Definitions, and Models,” J. Int. Soc. Phys. Rehabil. Med., vol. 2, no. suppl 1, pp. s70–s75, 2019. [CrossRef]

- T. S. Jesus, M. D. Landry, H. Hoenig, G. Dussault, G. C. Koh, and I. Fronteira, “Is Physical Rehabilitation Need Associated With the Rehabilitation Workforce Supply? An Ecological Study Across 35 High-Income Countries,” Int. J. Heal. Policy Manag., vol. 11, no. 4, pp. 434–442, 2022. [CrossRef]

- T. S. Jesus, M. D. Landry, G. Dussault, and I. Fronteira, “Human resources for health (and rehabilitation): Six Rehab-Workforce Challenges for the century,” Hum. Resour. Health, vol. 15, no. 1, pp. 1–12, 2017. [CrossRef]

- Hayes, V. Dos Santos, M. Costigan, and D. Morante, “Profile of occupational therapy services in non-urban settings: A global scoping review,” Aust. Occup. Ther. J., vol. 70, no. 1, pp. 119–141, 2023. [CrossRef]

- R. Speyer et al., “Effects of telehealth by allied health professionals and nurses in rural and remote areas: A systematic review and meta-Analysis,” J. Rehabil. Med., vol. 50, no. 3, pp. 225–235, 2018. [CrossRef]

- NICE, Stroke rehabilitation in adults, no. October. 2023.

- S. E. Washington, R. M. Bollinger, E. Edwards, L. McGowan, and S. Stephens, “Telehealth Delivery of Evidence-Based Intervention Within Older Adult Populations: A Scoping Review,” OTJR Occup. Ther. J. Res., vol. 43, no. 3, pp. 467–477, 2023. [CrossRef]

- C. Ho et al., “Models of Care Delivery from Rehabilitation to Community for Spinal Cord Injury: A Scoping Review,” J. Neurotrauma, vol. 38, no. 6, pp. 677–697, 2021. [CrossRef]

- Ghaffar et al., “Role and promise of health policy and systems research in integrating rehabilitation into the health systems,” Heal. Res. policy Syst., vol. 22, no. 1, p. 143, 2024. [CrossRef]

- M. Banks, H. Kuper, and S. Polack, “Poverty and disability in low-And middleincome countries: A systematic review,” PLoS One, vol. 12, no. 12, pp. 1–19, 2017. [CrossRef]

- T. S. Jesus and H. Hoenig, “Crossing the Global Quality Chasm in Health Care: Where Does Rehabilitation Stand?,” Arch. Phys. Med. Rehabil., vol. 100, no. 11, pp. 2215–2217, 2019. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).