Submitted:

07 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Laboratory Analysis

2.2. P Sorption Capacity

2.3. Machine Learning

2.4. Causal Discovery

2.5. Comparison of the Langmuir Isotherms and the Multi-Output XGBoost Regressor on a Large Soil Dataset

3. Results

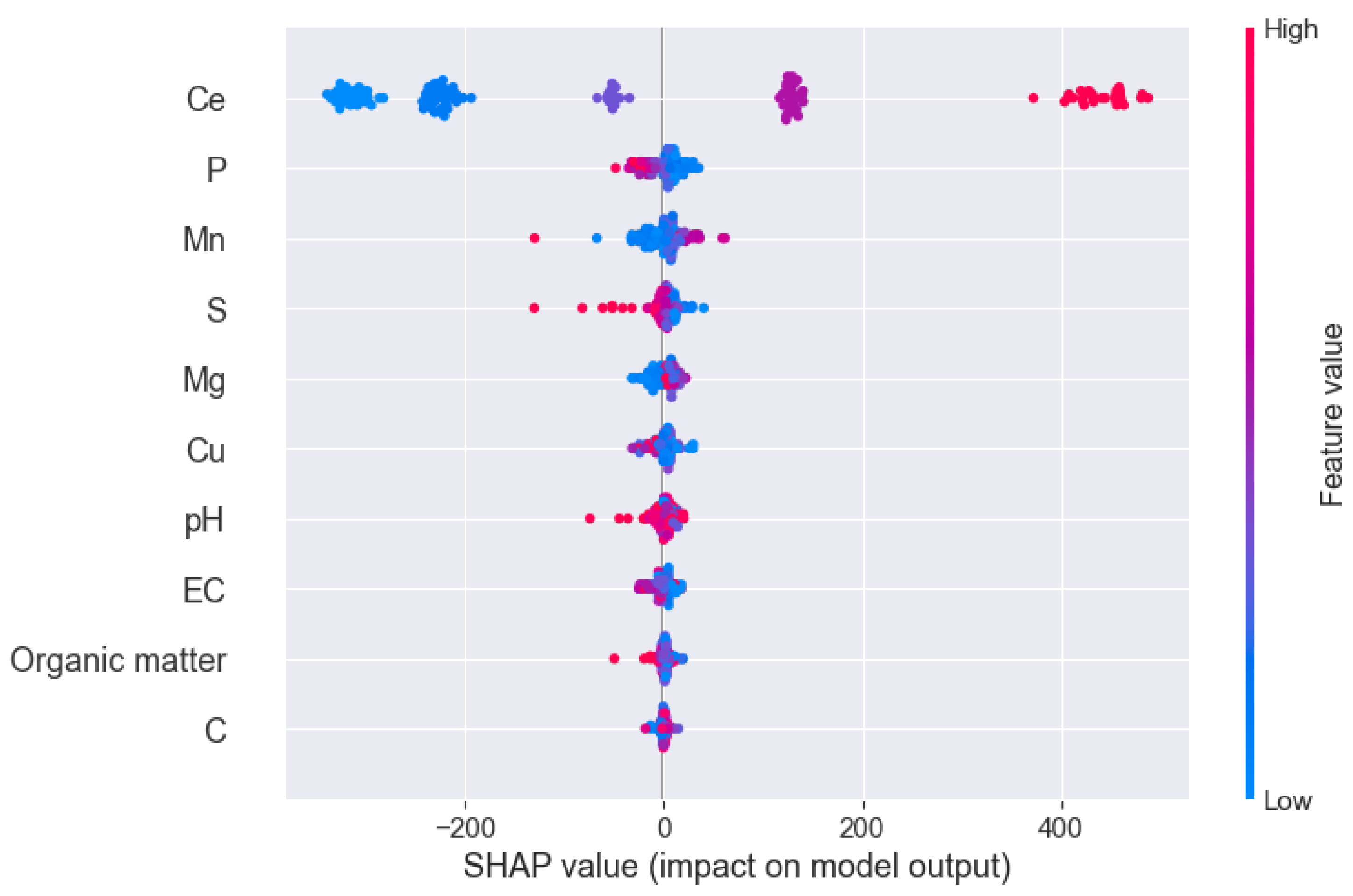

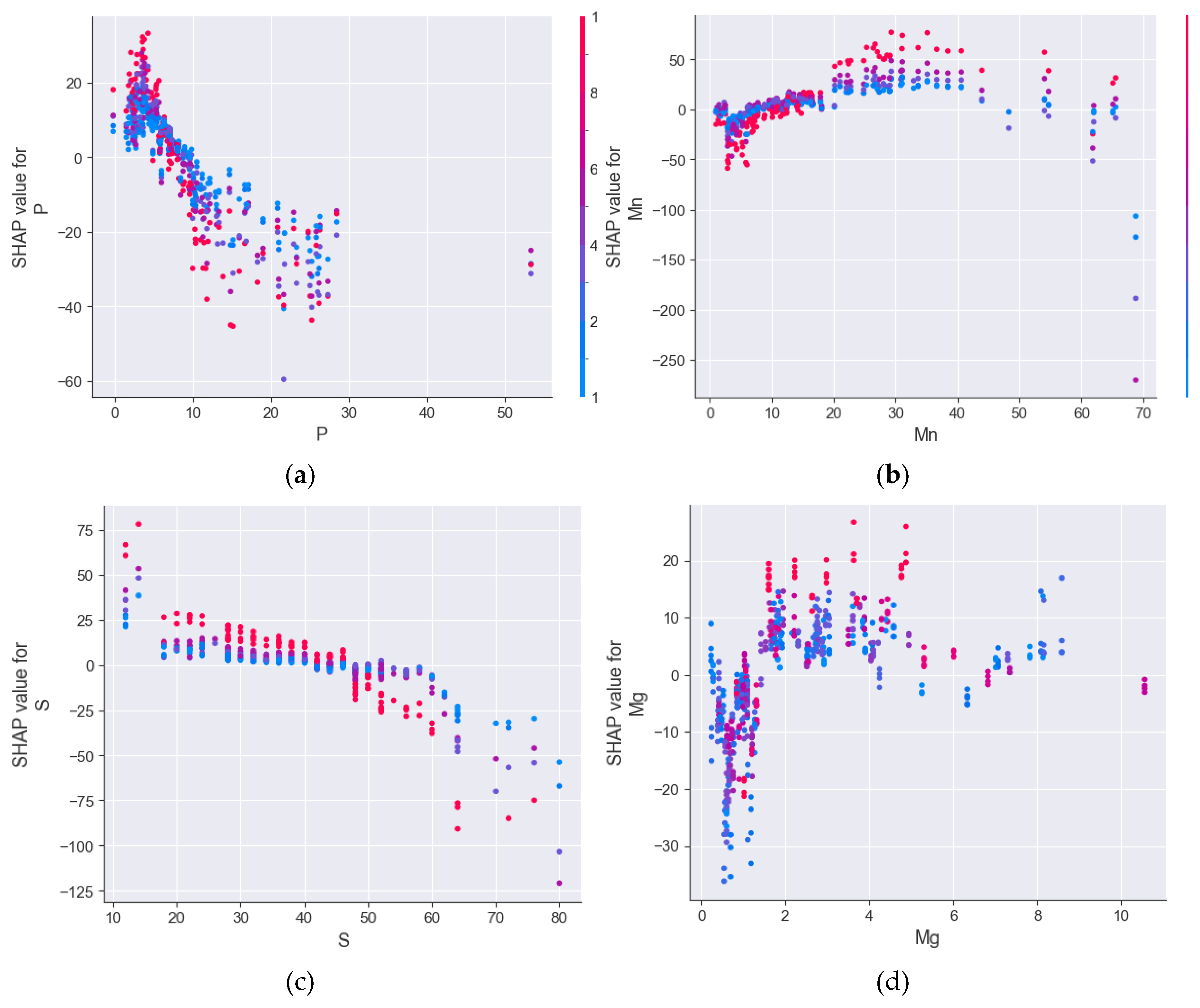

3.1. Feature Engineering

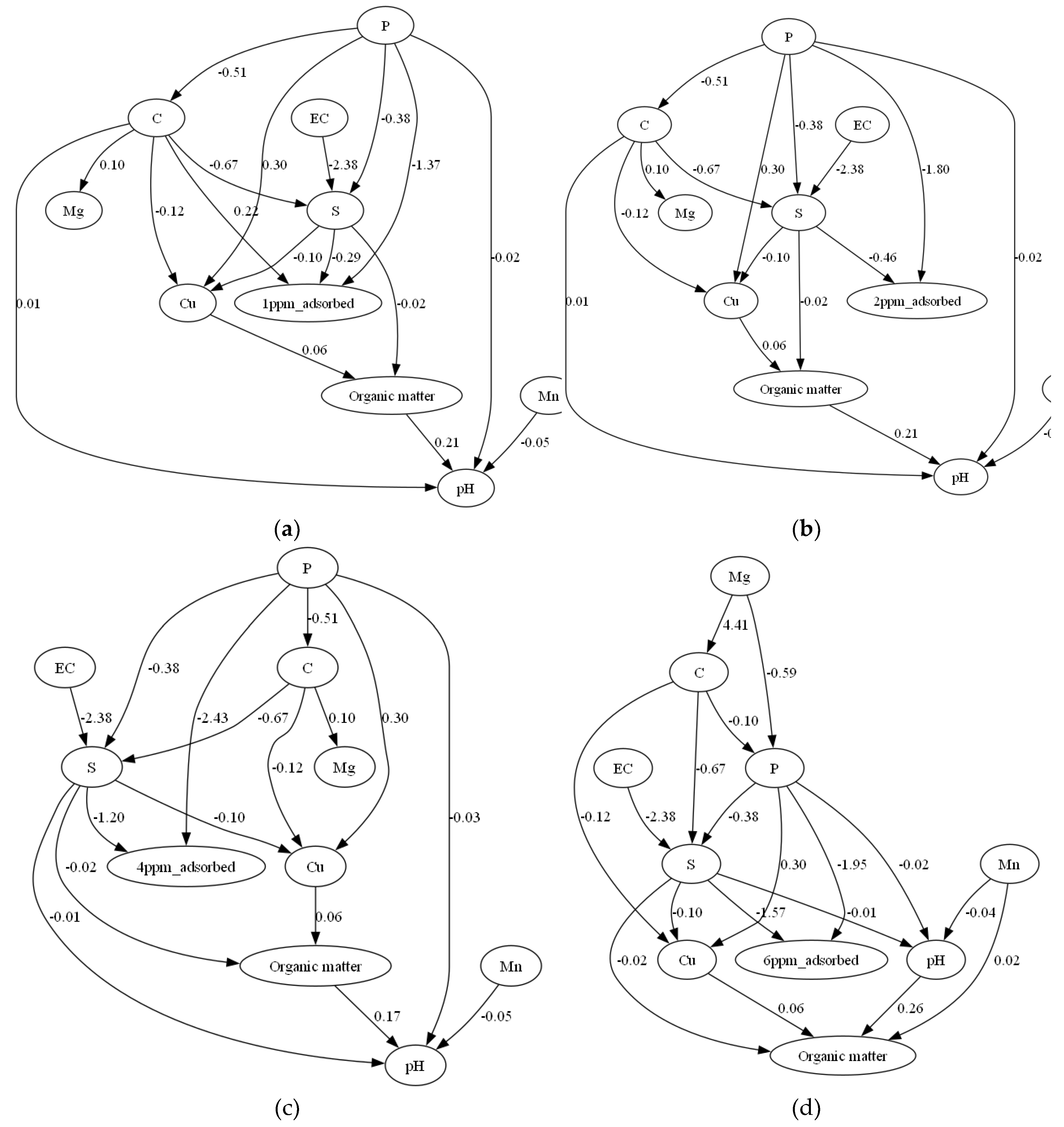

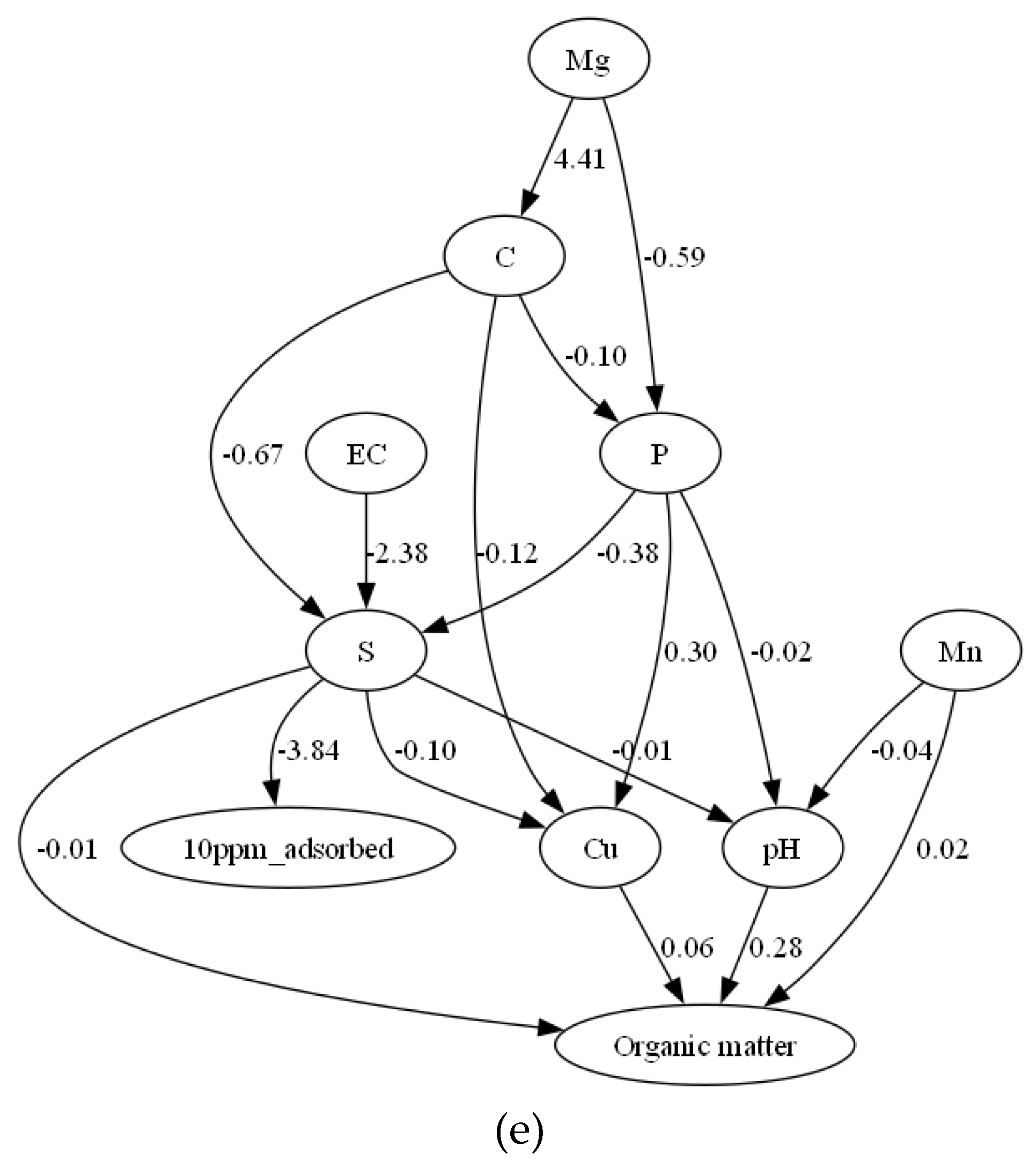

3.2. Causal Inference

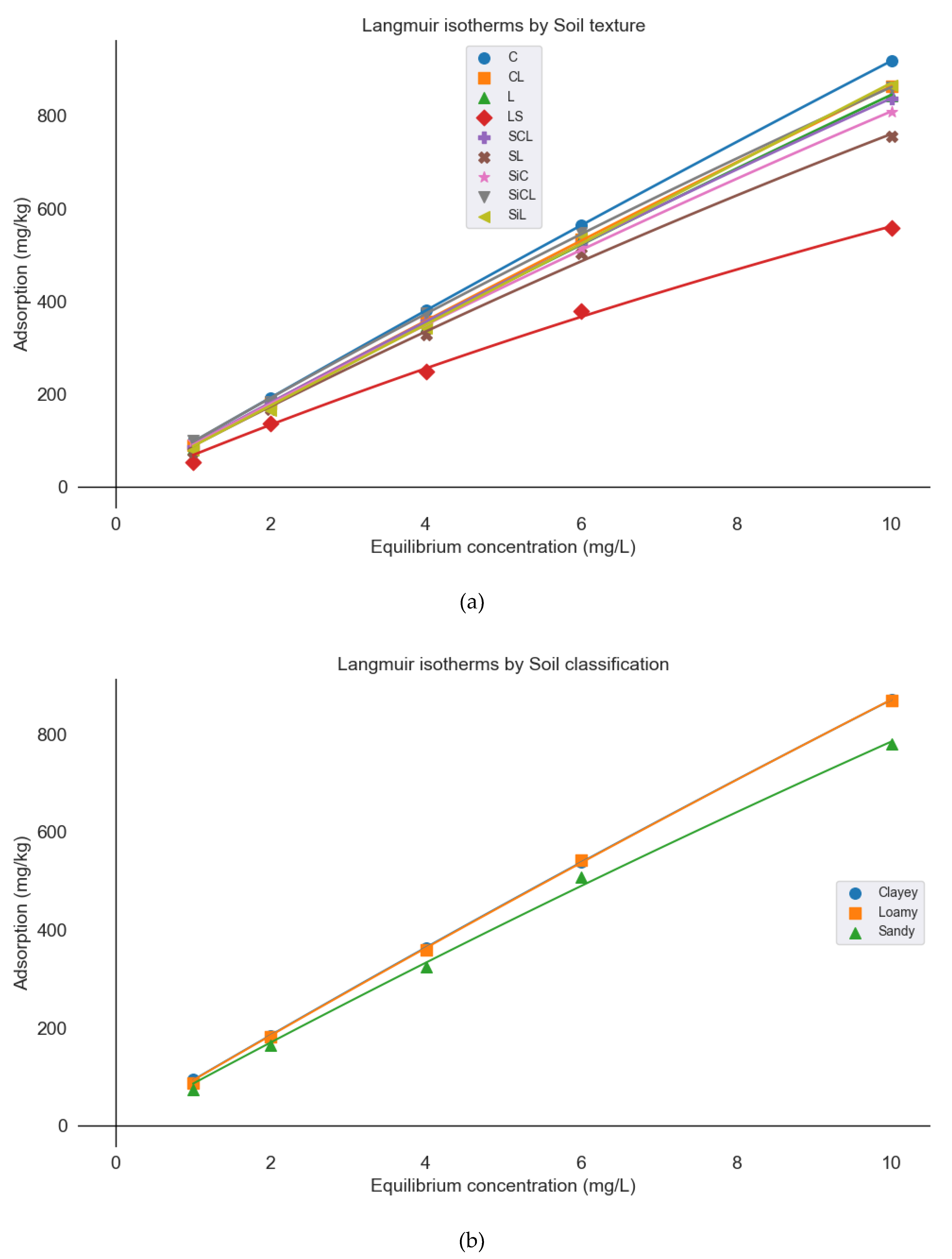

3.3. Langmuir Equations

3.4. Multiple Linear Regression Equations

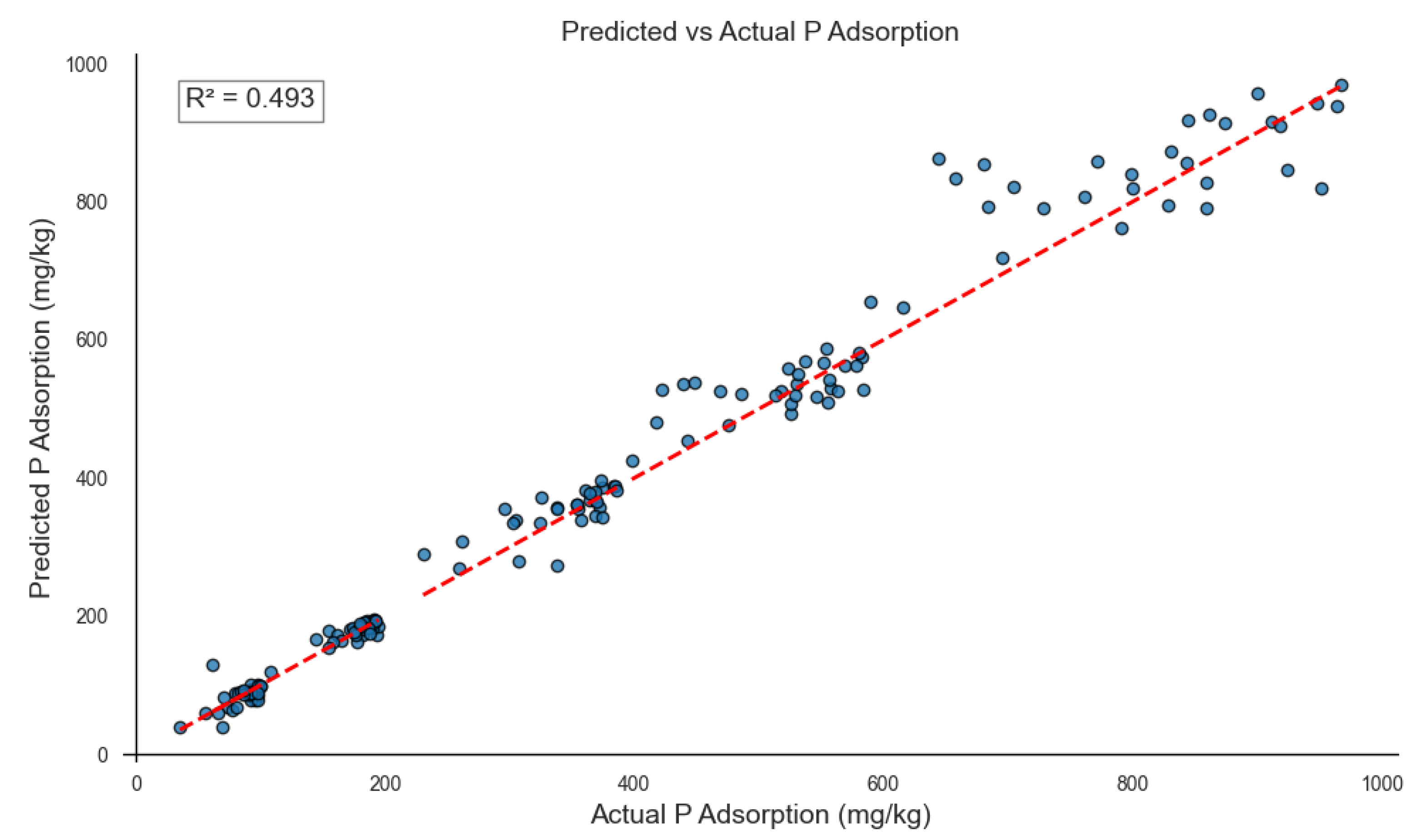

3.5. Multi-output XGBoost model performance

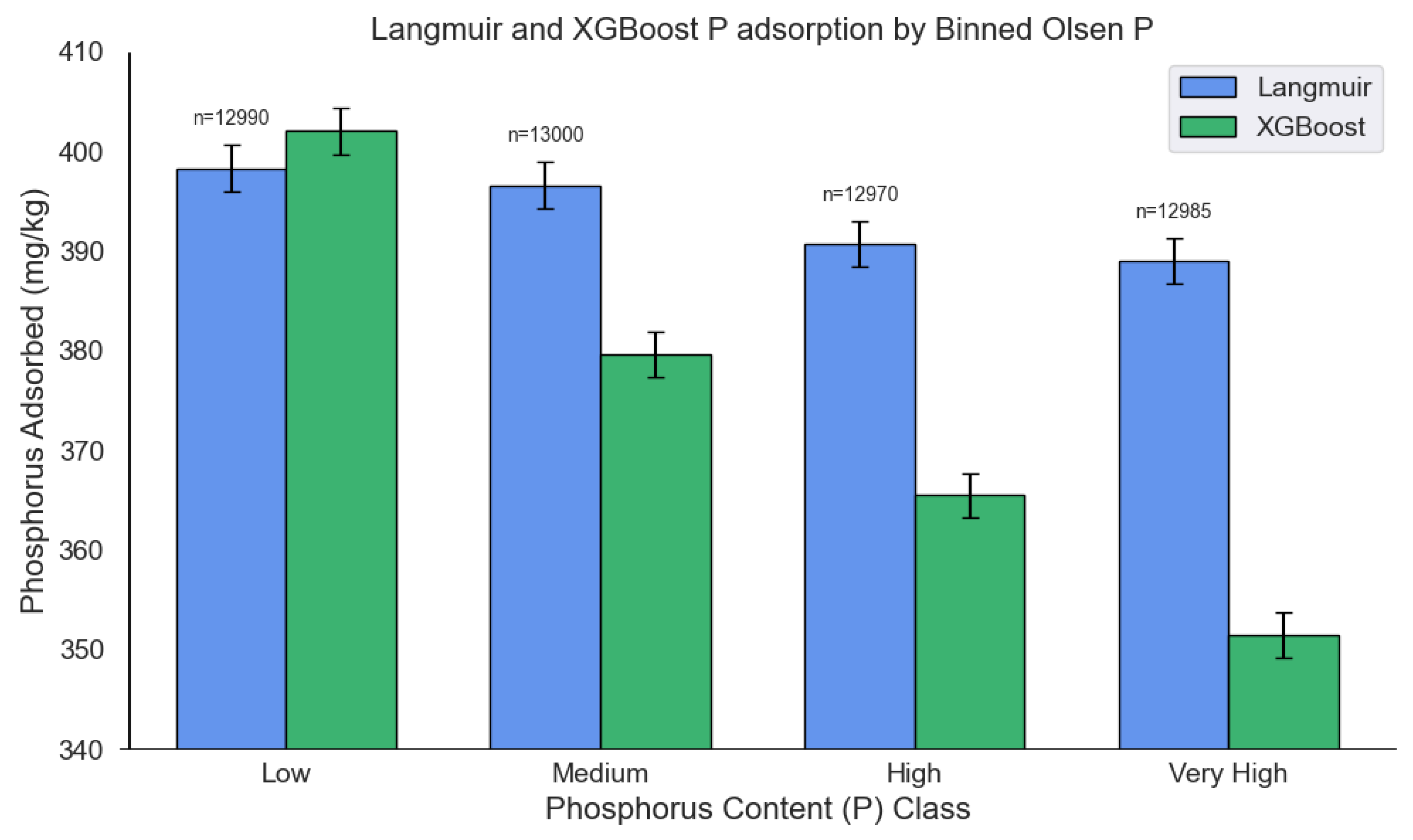

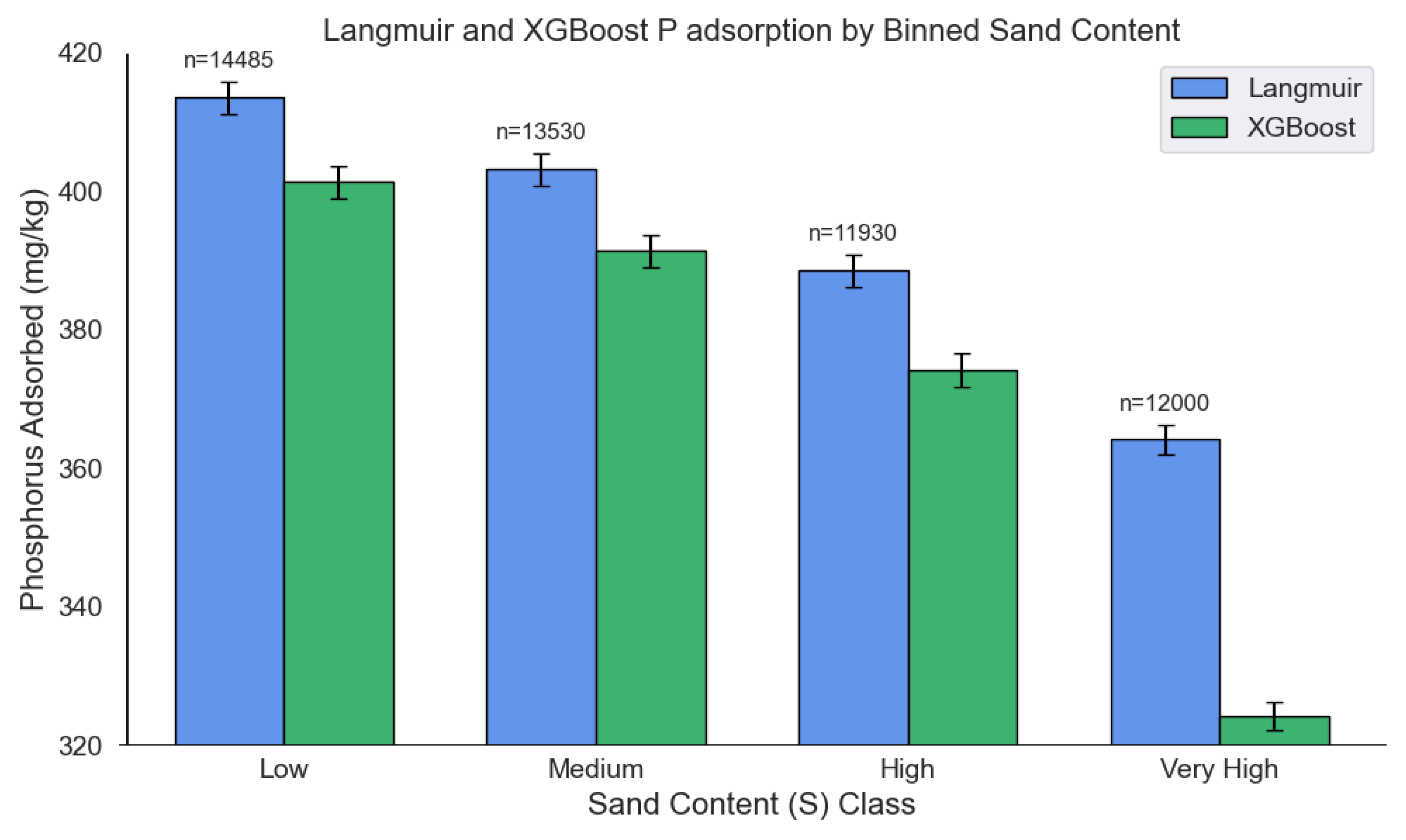

3.6. Performance of the multi-output XGBoost model and Langmuir isotherms on an extended soil dataset

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| MDPI | Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute |

| P | Phosphorus |

| RFE | Recursive Feature Elimination |

| MAE | Mean Absolute Error |

| DirectLiNGAM | Direct Linear Non-Gaussian Acyclic Model |

| DAG | Directed Acyclic Graph |

References

- Kirkby, E.A.; Johnston, A.E. (Johnny) Soil and Fertilizer Phosphorus in Relation to Crop Nutrition. In The Ecophysiology of Plant-Phosphorus Interactions; White, P.J., Hammond, J.P., Eds.; Springer Netherlands: Dordrecht, 2008; pp. 177–223 ISBN 978-1-4020-8435-5.

- Marschner, P. Marschner’s Mineral Nutrition of Higher Plants; 2012.

- Mihoub, A.; Daddi Bouhoun, M.; Saker, M. Phosphorus Adsorption Isotherm: A Key Aspect for Effective Use and Environmentally Friendly Management of Phosphorus Fertilizers in Calcareous Soils. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal 2016, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Xiao, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Qiao, Y.; Chen, Y.; Wu, H.; Hu, C. The Crop Phosphorus Uptake, Use Efficiency, and Budget under Long-Term Manure and Fertilizer Application in a Rice–Wheat Planting System. Agriculture 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amarh, F.; Voegborlo, R.B.; Essuman, E.K.; Agorku, E.S.; Tettey, C.O.; Kortei, N.K. Effects of Soil Depth and Characteristics on Phosphorus Adsorption Isotherms of Different Land Utilization Types: Phosphorus Adsorption Isotherms of Soil. Soil Tillage Res 2021, 213, 105139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iatrou, M.; Papadopoulos, a.; Papadopoulos, F.; Dichala, O.; Psoma, P.; Bountla, a. Determination of Soil Available Phosphorus Using the Olsen and Mehlich 3 Methods for Greek Soils Having Variable Amounts of Calcium Carbonate. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal 2014, 45, 2207–2214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heredia, O.S.; Fernández Cirelli, A. Environmental Risks of Increasing Phosphorus Addition in Relation to Soil Sorption Capacity. Geoderma 2007, 137, 426–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holman, I.P.; Howden, N.J.K.; Bellamy, P.; Willby, N.; Whelan, M.J.; Rivas-Casado, M. An Assessment of the Risk to Surface Water Ecosystems of Groundwater P in the UK and Ireland. Science of The Total Environment 2010, 408, 1847–1857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olsen, S.R.; Watanabe, F.S. A Method to Determine a Phosphorus Adsorption Maximum of Soils as Measured by the Langmuir Isotherm. Soil Science Society of America Journal 1957, 21, 144–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HELYAR, K.R.; MUNNS, D.N.; BURAU, R.G. ADSORPTION OF PHOSPHATE BY GIBBSITE. Journal of Soil Science 1976, 27, 307–314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bolster, C.; Sistani, K. Sorption of Phosphorus from Swine, Dairy, and Poultry Manures. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal 2009, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gjettermann, B. Modelling P Dynamics in Soil - Decomposition and Sorption: Technical Report; Concepts and User Manual. ; 2004.

- Zawadzka, B.; Siwiec, T.; Reczek, L.; Marzec, M.; Jóźwiakowski, K. Modeling of Phosphate Sorption Process on the Surface of Rockfos® Material Using Langmuir Isotherms. Applied Sciences 2024, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dari, B.; Nair, V.D.; Colee, J.; Harris, W.G.; Mylavarapu, R. Estimation of Phosphorus Isotherm Parameters: A Simple and Cost-Effective Procedure. Front Environ Sci 2015, Volume 3-2015.

- Del Bubba, M.; Arias, C.A.; Brix, H. Phosphorus Adsorption Maximum of Sands for Use as Media in Subsurface Flow Constructed Reed Beds as Measured by the Langmuir Isotherm. Water Res 2003, 37, 3390–3400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dossa, E.; Baham, J.; Khouma, M.; Sene, M.; Kizito, F.; Dick, R. Phosphorus Sorption and Desorption in Semiarid Soils of Senegal Amended With Native Shrub Residues. Soil Sci 2008, 173, 669–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, J.B. Laboratory Guide for Conducting Soil Tests and Plant Analysis; Taylor & Francis, 2001; ISBN 9780849302060.

- Magdoff, F.R.; Jokela, W.E.; Fox, R.H.; Griffin, G.F. A Soil Test for Nitrogen Availability in the Northeastern United States. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal 1990, 21, 1103–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walkley, A.; Black, I.A. AN EXAMINATION OF THE DEGTJAREFF METHOD FOR DETERMINING SOIL ORGANIC MATTER, AND A PROPOSED MODIFICATION OF THE CHROMIC ACID TITRATION METHOD. Soil Sci 1934, 37, 29–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Reeuwijk, L.P. Procedures for Soil Analysis. 2002.

- Bouyoucos, G.J. Hydrometer Method Improved for Making Particle Size Analyses of Soils1. Agron J 1962, 54, 464–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knudsen, D.; Peterson, G.A.; Pratt, P.F. Lithium, Sodium, and Potassium. In Methods of Soil Analysis; Agronomy Monographs; 1983; pp. 225–246 ISBN 9780891189770.

- Iatrou, M.; Papadopoulos, A.; Papadopoulos, F.; Dichala, O.; Psoma, P.; Bountla, A. Determination of Soil-Available Micronutrients Using the DTPA and Mehlich 3 Methods for Greek Soils Having Variable Amounts of Calcium Carbonate. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal 2015, 46, 1905–1912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey, A.J.; McCallum, L.E. Investigation of a Hot 0.01m CaCl2 Soil Boron Extraction Procedure Followed by ICP-AES Analysis. Commun Soil Sci Plant Anal 1988, 19, 663–673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Hou, L.; Liu, Z.; Cao, N.; Wang, X. Using a Modified Langmuir Equation to Estimate the Influence of Organic Materials on Phosphorus Adsorption in a Mollisol From Northeast, China. Front Environ Sci 2022, Volume 10-2022.

- Nair, P.S.; Logan, T.J.; Sharpley, A.N.; Sommers, L.; Tabatabai, M.; Yuan, T.L. Interlaboratory Comparison of a Standardized Phosphorus Adsorption Procedure. J Environ Qual 1984, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lundberg, S.M.; Lee, S.-I. A Unified Approach to Interpreting Model Predictions. CoRR 2017, abs/1705.0.

- Guyon, I.; Weston, J.; Barnhill, S.; Vapnik, V. Gene Selection for Cancer Classification Using Support Vector Machines. Mach Learn 2002, 46, 389–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Breiman, L. Random Forests. Mach Learn 2001, 45, 5–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Guestrin, C. XGBoost: A Scalable Tree Boosting System. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22Nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2016; pp. 785–794. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, D.; Shi, Y.; Tsang, I.W.; Ong, Y.-S.; Gong, C.; Shen, X. Survey on Multi-Output Learning. IEEE Trans Neural Netw Learn Syst 2020, 31, 2409–2429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Akiba, T.; Sano, S.; Yanase, T.; Ohta, T.; Koyama, M. Optuna: {A} Next-Generation Hyperparameter Optimization Framework. CoRR 2019, abs/1907.1.

- Shimizu, S.; Inazumi, T.; Kawahara, Y.; Washio, T.; Hoyer PATRIKHOYER, P.O.; Bollen, K.; Sogawa, Y.; Hyvärinen, A.; Hoyer, P.O.; Bollen SHIMIZU, K. DirectLiNGAM: A Direct Method for Learning a Linear Non-Gaussian Structural Equation Model Yasuhiro Sogawa Aapo Hyvärinen; 2011; Vol. 12.

- Niyogi, D.; Kishtawal, C.; Tripathi, S.; Govindaraju, R. Observational Evidence That Agricultural Intensification and Land Use Change May Be Reducing the Indian Summer Monsoon Rainfall. Water Resources Research - WATER RESOUR RES 2010, 46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hyvärinen, A.; Smith, S.M.; Spirtes, P. Pairwise Likelihood Ratios for Estimation of Non-Gaussian Structural Equation Models.

- Tukey, J.W. Comparing Individual Means in the Analysis of Variance. Biometrics 1949, 5 2, 99–114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossum, G. Van; Drake, F.L. Python Tutorial. History 2010, 42, 1–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunter, J.D. Matplotlib: A 2D Graphics Environment. Computing in Science Engineering 2007, 9, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iatrou, M.; Karydas, C.; Tseni, X.; Mourelatos, S. Representation Learning with a Variational Autoencoder for Predicting Nitrogen Requirement in Rice. Remote Sens (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iatrou, M.; Karydas, C.; Iatrou, G.; Pitsiorlas, I.; Aschonitis, V.; Raptis, I.; Mpetas, S.; Kravvas, K.; Mourelatos, S. Topdressing Nitrogen Demand Prediction in Rice Crop Using Machine Learning Systems. Agriculture 2021, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- HUSSAIN, A.; Ghafoor, A.; Anwar-ul-Haq, M.; NAWAZ, M. Application of the Langmuir and Freundlich Equations for P Adsorption Phenomenon in Saline-Sodic Soils. 2002, 5.

- Lair, G.J.; Zehetner, F.; Khan, Z.H.; Gerzabek, M.H. Phosphorus Sorption–Desorption in Alluvial Soils of a Young Weathering Sequence at the Danube River. Geoderma 2009, 149, 39–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rossi, C.G.; Heil, D.M.; Bonumà, N.B.; Williams, J.R. Evaluation of the Langmuir Model in the Soil and Water Assessment Tool for a High Soil Phosphorus Condition. Environmental Modelling & Software 2012, 38, 40–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Chen, X.; Yang, X. Effect of Organic Matter on Phosphorus Adsorption and Desorption in a Black Soil from Northeast China. Soil Tillage Res 2019, 187, 85–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iatrou, M.; Tziachris, P.; Bilias, F.; Kekelis, P.; Pavlakis, C.; Theofilidou, A.; Papadopoulos, I.; Strouthopoulos, G.; Giannopoulos, G.; Arampatzis, D.; et al. Data-Driven and Mechanistic Soil Modeling for Precision Fertilization Management in Cotton. Nitrogen 2025, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Halliday, D.J.; Association, I.F.I. IFA World Fertilizer Use Manual; International Fertilizer Industry Association, 1992; ISBN 9782950629906.

| Group | pH Range | CaCO3 Range | Description | Soil Texture |

| 1 | 4.30 – 6.20 | 0 | Acidic | Clayey, Loamy, Sandy |

| 2 | 6.25 – 7.96 | 0 – 0.9% | Neutral, low carbonate | Clayey, Loamy, Sandy |

| 3 | 6.83 – 8.18 | 1 – 10% | Alkaline, moderately calcareous | Clayey, Loamy, Sandy |

| 4 | 7.20 – 8.28 | 10.3 – 48.3% | Strongly alkaline, calcareous | Clayey, Loamy, Sandy |

| pH → | 4-6 | 6-7 | >7 | >7 | >7 | >7 | >7 |

| Clayey | 5 | 5 | 5 | 8 | 10 | 2 | 5 |

| Loamy | 9 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 9 | 6 |

| Sandy | 9 | 12 | 12 | 5 | 6 | 0 | 1 |

| CaCO3 → | 0% | 0-1% | 1-5% | 5-10% | 10-20% | 20-30% | >30% |

| Soil classification | Qm | K |

| Clayey | 11,822.86 | 0.0080 |

| Loamy | 12,899.80 | 0.0072 |

| Sandy | 8,231.61 | 0.0106 1 |

| Soil type | Qm | K |

| Clay (C) | 16,366.06 | 0.0059 |

| Clay loam (CL) | 14,959.94 | 0.0061 |

| Loamy (L) | 12,055.41 | 0.0075 |

| Silty loam (SiL) | 10,4509.79 | 0.0008 |

| Loamy Sand (LS) | 2,803.55 | 0.0251 |

| Sandy Clay Loam (SCL) | 8,517.25 | 0.0109 |

| Sandy Loam (SL) | 4,998.74 | 0.0180 |

| Silty Clay (SiC) | 6,686.86 | 0.0138 |

| Silty Clay Loam (SiCL) | 6,840.72 | 0.01441 |

| Equilibrium concentrations (mg/L) | |||||

| Soil type | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 10 |

| Clay (C) | 98.2 ± 3.5a | 93.6 ± 11.1a | 93.3 ± 10.1a | 92.4 ± 9.5a | 91.2 ± 7.6a |

| Clay loam (CL) | 92.3 ± 8.2b | 91.8 ± 8.0b | 90.7 ± 8.2b | 90.6 ± 7.6b | 87.5 ± 9.7b |

| Loamy (L) | 81.8 ± 17.2a | 88.5 ± 9.3c | 86.6 ± 15.5c | 88.5 ± 7.9c | 83.6 ± 9.8c |

| Loamy Sand (LS) | 52.6 ± 9.9b | 68.3 ± 31.7d | 62.2 ± 23.2a | 63.4 ± 27.9a | 55.8 ± 27.9a |

| Sandy Clay Loam (SCL) | 86.7 ± 11.1c | 90.1 ± 6.9e | 89.4 ± 6.7d | 87.7 ± 8.7d | 83.8 ± 11.0d |

| Sandy Loam (SL) | 75.7 ± 23.3d | 83.2 ± 17.3f | 81.7 ± 17.2e | 83.4 ± 12.0e | 75.1 ± 12.9b |

| Silty Clay (SiC) | 98.5 ± 0.7e | 87.3 ± 14.0g | 86.4 ± 17.7f | 85.9 ± 17.9f | 81.0 ± 23.3e |

| Silty Clay Loam (SiCL) | 99.8 ± 0.3f | 91.8 ± 8.1h | 93.8 ± 4.2g | 91.5 ± 4.4g | 86.2 ± 6.3f |

| Silty loam (SiL) | 80.0 ± 24.9g | 83.1 ± 21.1i | 85.6 ± 12.5h | 90.4 ± 7.7h | 86.7 ± 7.4g |

| Equilibrium concentrations (mg/L) | |||||

| Soil type | 1 | 2 | 4 | 6 | 10 |

| Clay (C) | 91.1 ± 12.9a | 89.7 ± 8.5a | 88.8 ± 8.2a | 88.5 ± 7.6a | 85.1 ± 7.4a |

| Clay loam (CL) | 83.6 ± 14.6a | 87.0 ± 8.9a | 86.8 ± 7.9a | 87.7 ± 6.5b | 84.7 ± 6.3b |

| Loamy (L) | 76.9 ± 14.4a | 84.3 ± 8.8a | 83.1 ± 8.6a | 85.6 ± 6.9a | 82.2 ± 7.0a |

| Loamy Sand (LS) | 76.3 ± 10.9b | 76.9 ± 9.5a | 65.8 ± 7.4a | 69.8 ± 7.6a | 61.6 ± 7.3a |

| Sandy (S) | 76.6 ± 11.1c | 76.9 ± 10.2b | 65.4 ± 5.1b | 69.8 ± 7.6b | 61.1 ± 6.6b |

| Sandy Clay (SC) | 81.5 ± 10.1d | 85.4 ± 6.4b | 84.3 ± 6.3b | 85.8 ± 3.3c | 82.3 ± 3.3c |

| Sandy Clay Loam (SCL) | 77.7 ± 12.7e | 84.0 ± 8.0c | 82.6 ± 8.2c | 83.6 ± 6.5a | 79.4 ± 6.8a |

| Sandy Loam (SL) | 74.4 ± 12.8a | 78.7 ± 9.8c | 73.8 ± 10.4a | 76.4 ± 9.8a | 70.2 ± 10.7a |

| Silty Clay (SiC) | 93.6 ± 10.0b | 89.7 ± 7.0c | 89.2 ± 7.7c | 88.6 ± 7.3d | 84.7 ± 7.2d |

| Silty Clay Loam (SiCL) | 93.1 ± 9.5c | 90.7 ± 5.7d | 90.4 ± 5.8a | 90.1 ± 5.4a | 86.4 ± 5.5b |

| Silty loam (SiL) | 84.6 ± 13.9b | 87.9 ± 7.2d | 87.2 ± 6.7d | 89.0 ± 5.0b | 85.4 ± 5.3e |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).