Submitted:

07 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Cell Culture

2.2. Cell Viability

2.3. Synergism Assessment

2.4. Apoptosis/Necrosis Analysis

2.5. Lysosomal Staining

2.6. Caspase Activation, Mitochondrial Membrane Potential and Superoxide Measurement

2.7. Measurements of Oxygen Consumption and Extracellular Acidification Rates

2.8. Intracellular ATP Quantification

2.9. RNA Interference

2.10. Immunoblotting

2.11. In Silico Analysis of Gene Expression

2.12. Statistical Analysis

3. Results

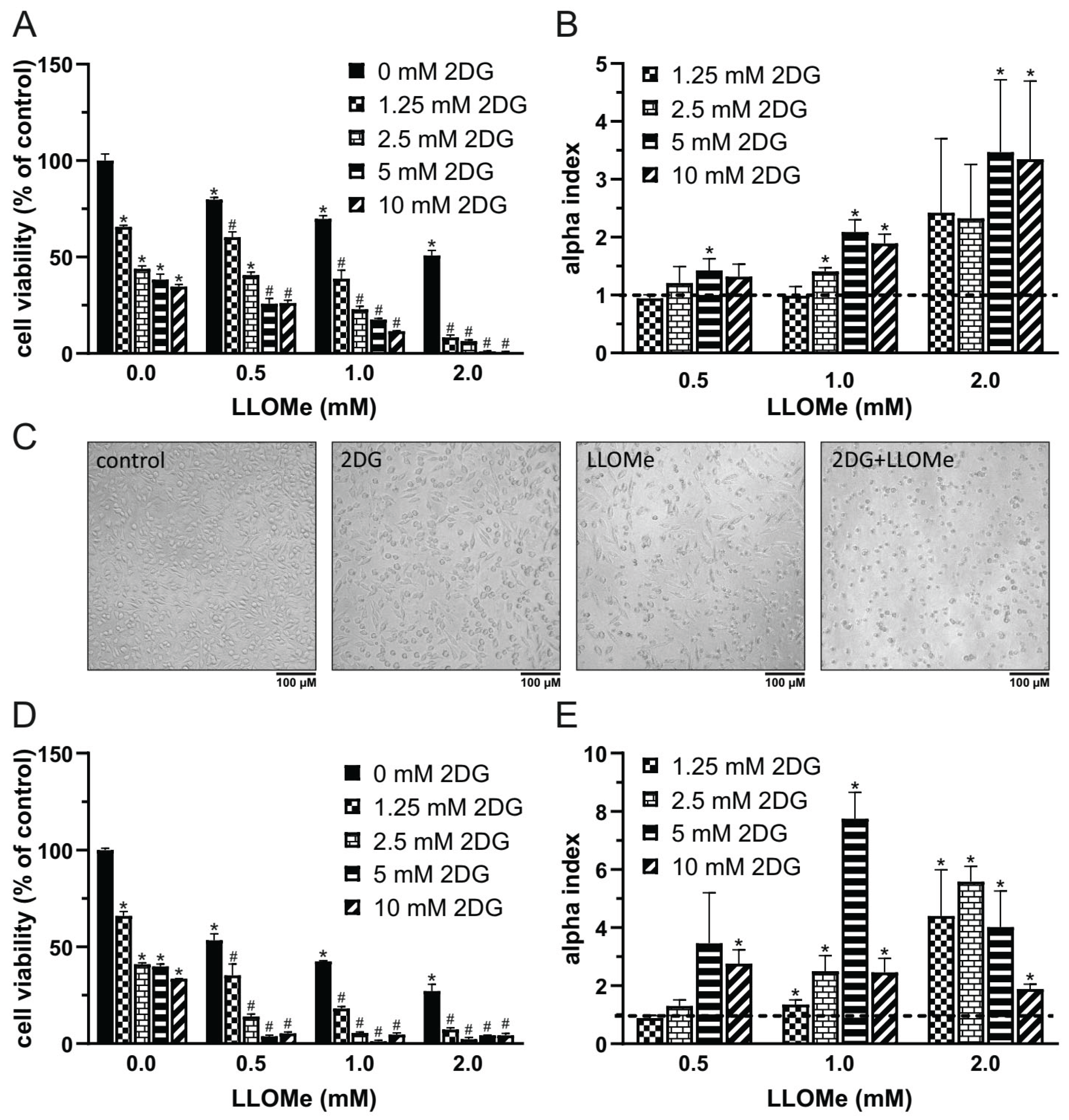

3.1. 2DG and LLOMe Synergistically Reduce Viability of A375 Melanoma Cells

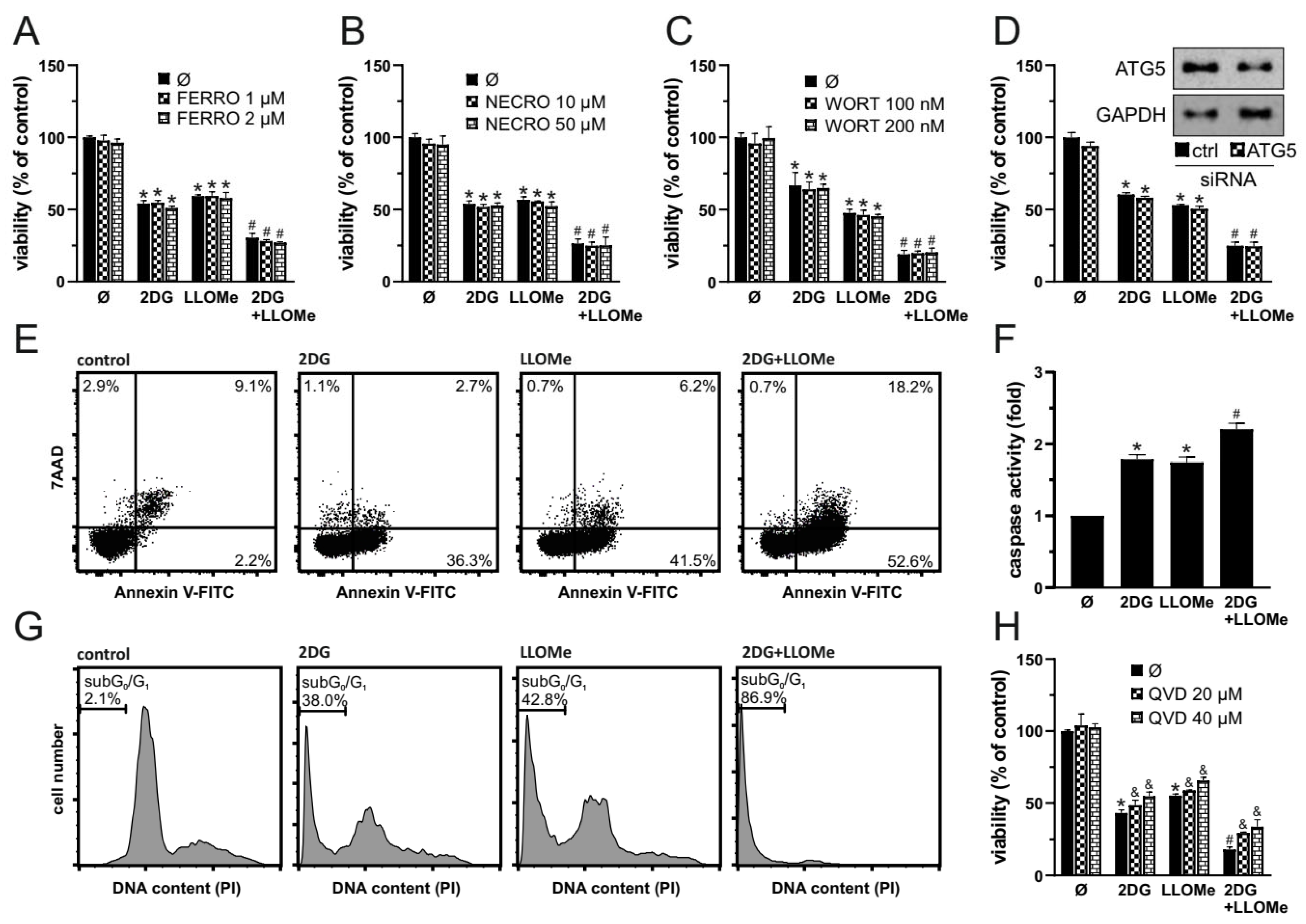

3.2. 2DG+LLOMe Induces Mixed Apoptotic and Necrotic Death in Melanoma Cells

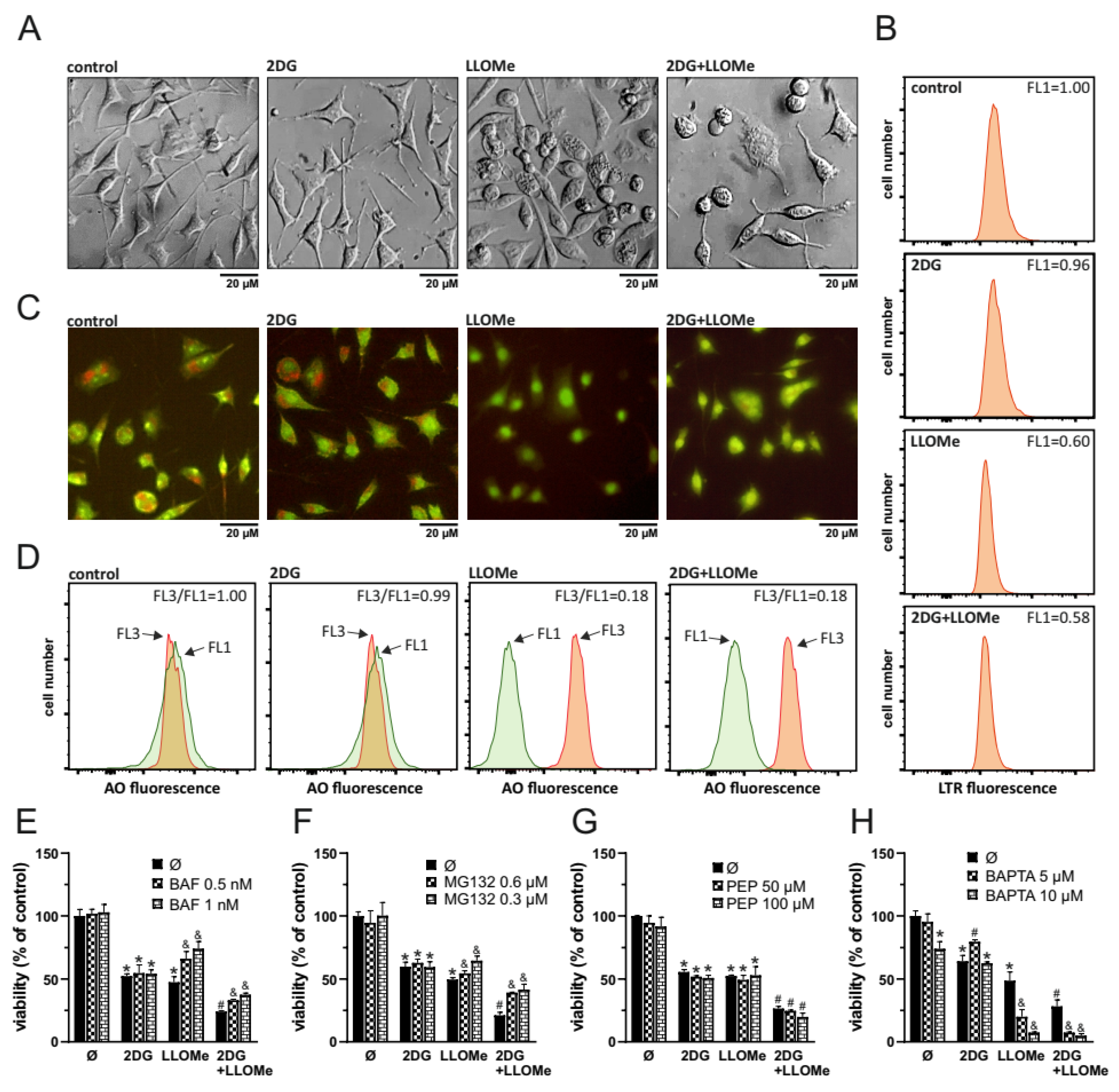

3.3. Antimelanoma Effect of 2DG+LLOMe Is Mediated by Lysosomal Destabilization

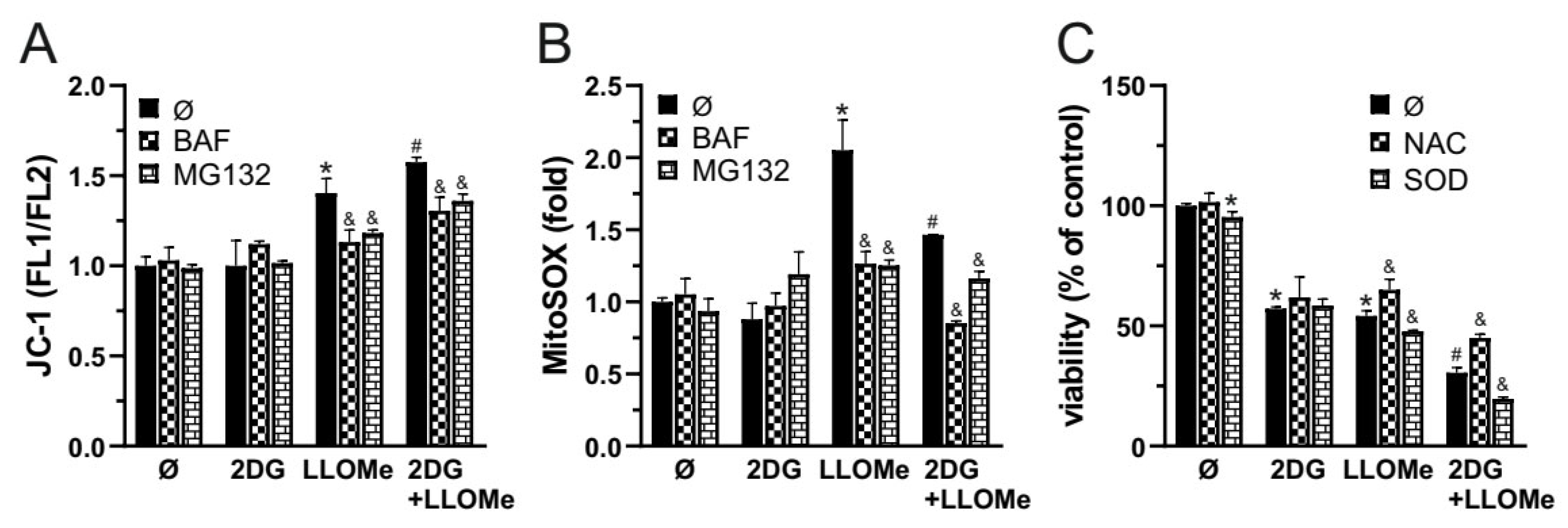

3.4. 2DG+LLOMe-induced Cell Death is Mediated by LMP-dependent Mitochondrial Depolarization and Superoxide

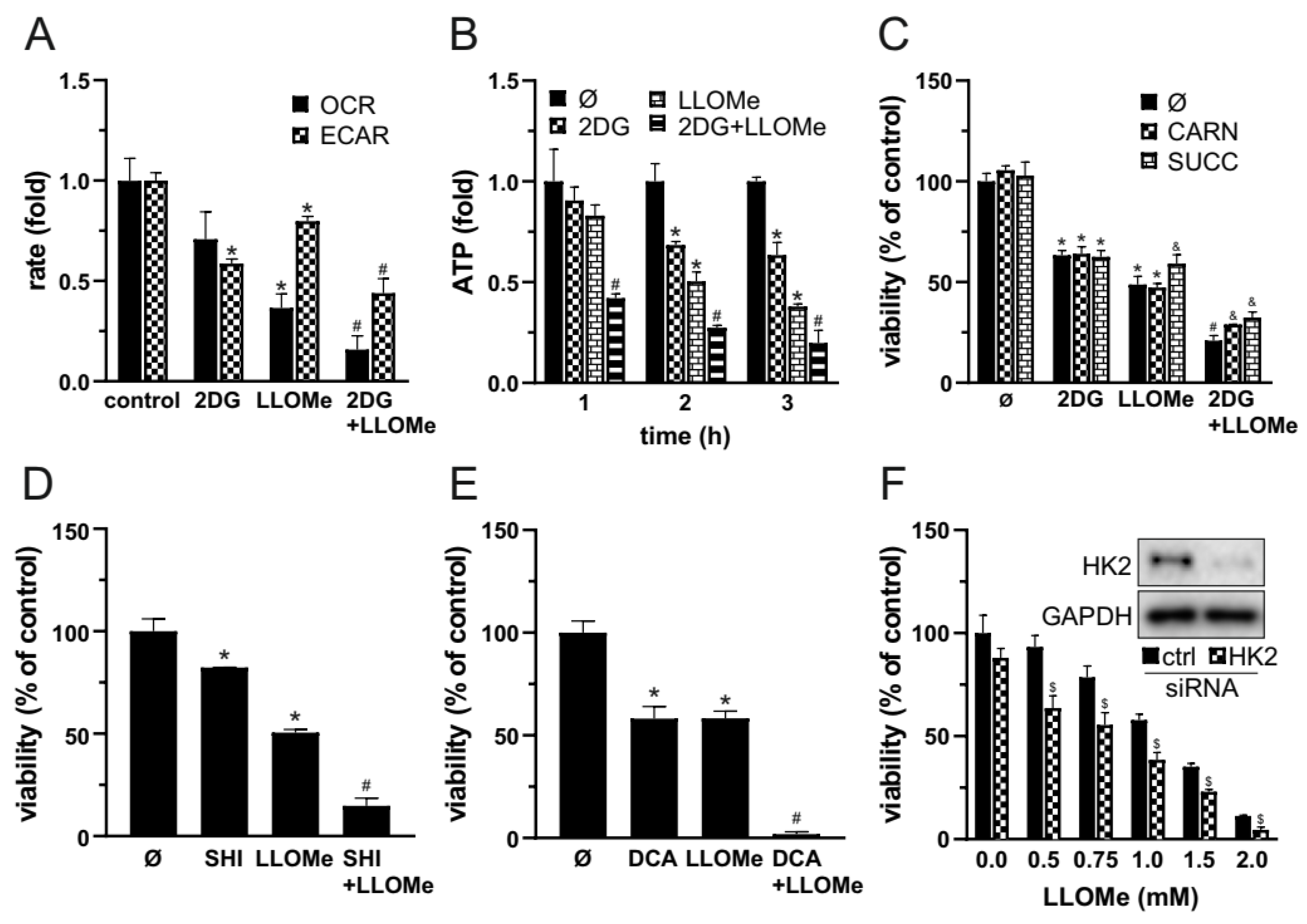

3.5. Combined Glycolytic and Mitochondrial Inhibition by 2DG and LLOMe Triggers Energetic Collapse and Loss of Viability

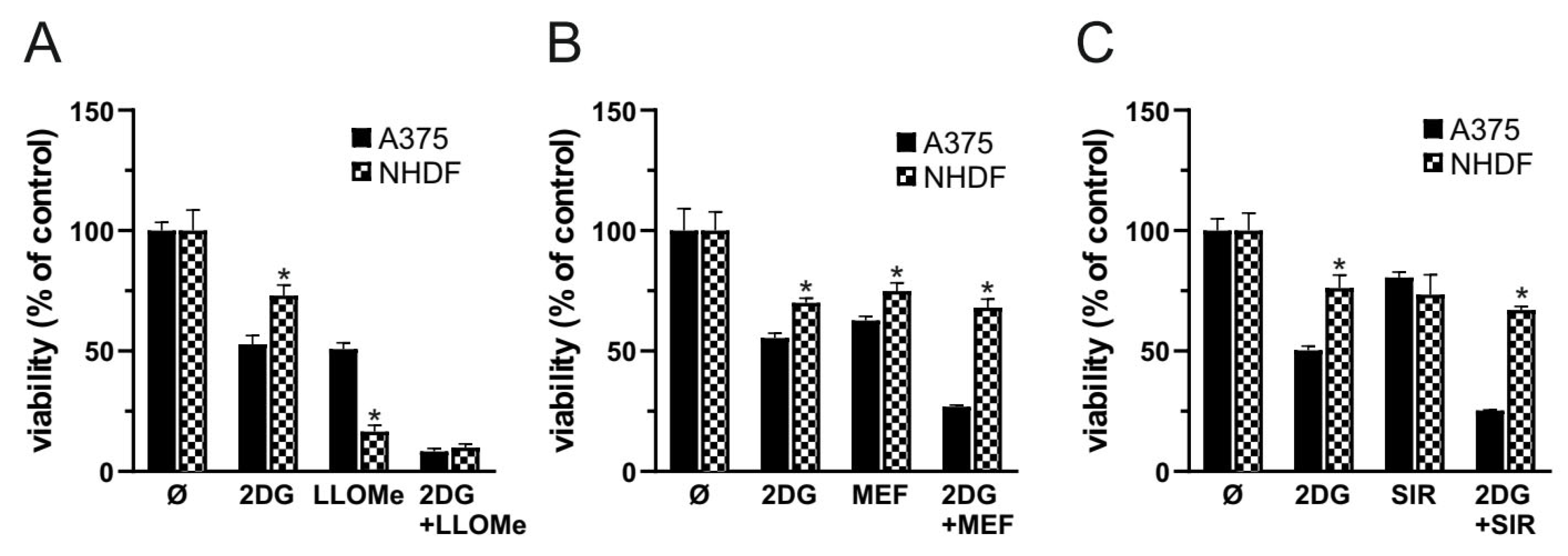

3.6. In Contrast to Mefloquine and Siramesine, LLOMe Exhibits Non-Selective Toxicity

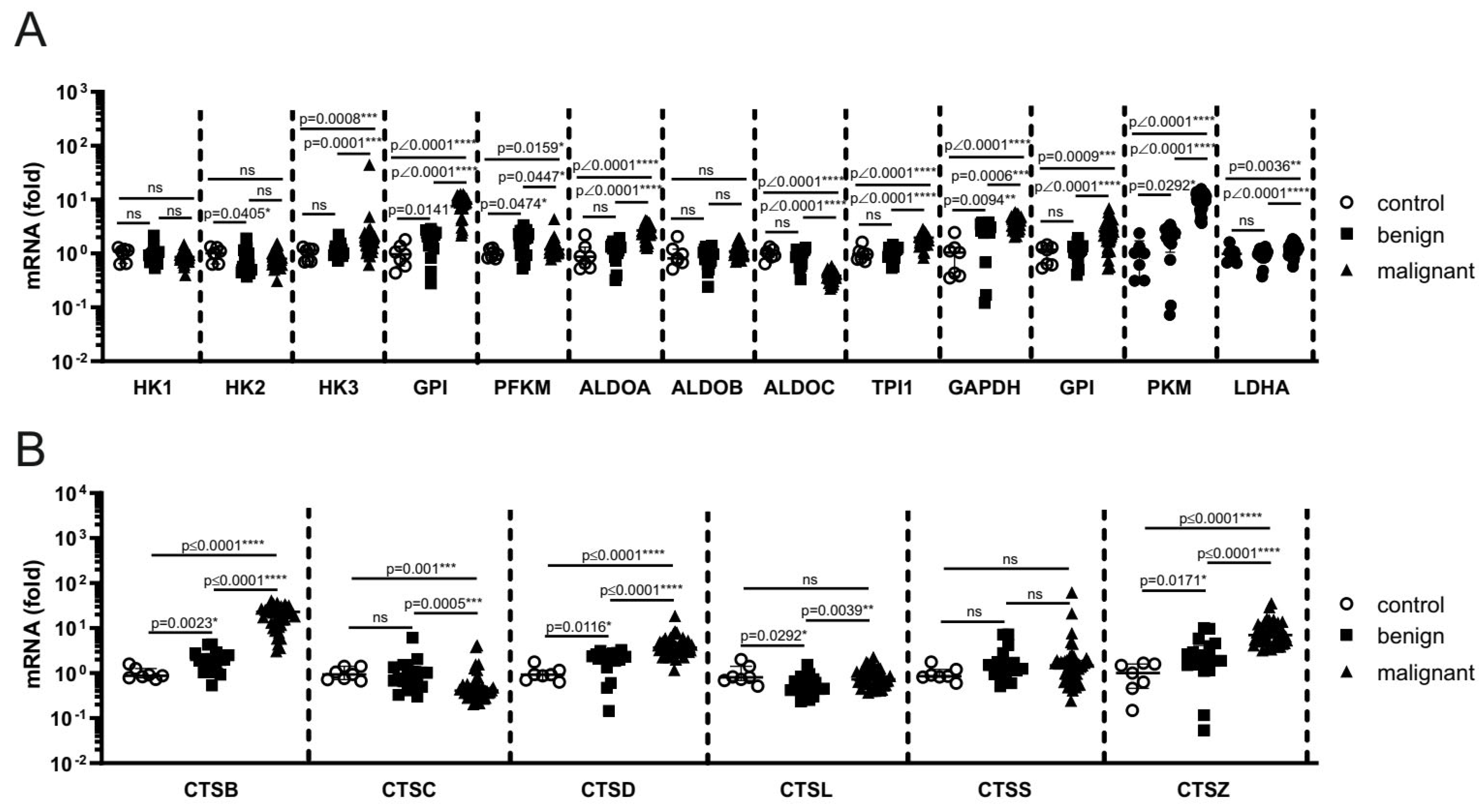

3.7. Melanoma Progression in Patient Samples Is Associated with Enhanced Expression of Glycolytic Enzymes and Cathepsins

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| 2DG | 2-deoxy-D-glucose |

| 7-AAD | 7-Aminoactinomycin D |

| ALDOA | aldolase A |

| ALDOB | aldolase B |

| ALDOC | aldolase C |

| AO | acridine orange |

| ATP | adenosine triphosphate |

| BAF | bafilomycin A1 |

| BAPTA | 1,2-bis(o-aminophenoxy)ethane-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid |

| Bcl-2 | B-cell lymphoma 2 |

| Bcl-xL | B-cell lymphoma-extra large |

| BRAF | v-Raf murine sarcoma viral oncogene homolog B |

| BSA | bovine serum albumin |

| CARN | L-carnitine |

| CTSB | cathepsin B |

| CTSC | cathepsin C |

| CTSD | cathepsin D |

| CTSL | cathepsin L |

| CTSS | cathepsin S |

| CTSZ | cathepsin Z |

| DAPI | 4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole |

| DCA | dichloroacetate |

| DHR123 | dihydrorhodamine 123 |

| DMEM | Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle Medium |

| DMSO | dimethyl sulfoxide |

| ECAR | extracellular acidification rate |

| FACS | fluorescence-activated cell sorting |

| FBS | fetal bovine serum |

| FERRO | Ferrostatin-1 |

| FITC | fluorescein isothiocyanate |

| GAPDH | glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase |

| GEO | Gene Expression Omnibus |

| GPI | glucose-6-phosphate isomerase |

| HK1 | hexokinase 1 |

| HK2 | hexokinase 2 |

| HK3 | hexokinase 3 |

| JC-1 | 5,5′,6,6′-tetrachloro-1,1′,3,3′-tetraethylbenzimidazolylcarbocyanine iodide |

| LDHA | lactate dehydrogenase A |

| LLOMe | L-leucyl-L-leucine methyl ester |

| Mcl-1 | Myeloid cell leukemia 1 |

| MEF | Mefloquine |

| MEK/ERK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase Kinase / Extracellular Signal-Regulated Kinase |

| MG132 | carbobenzoxy-Leu-Leu-leucinal |

| MMP | mitochondrial membrane potential |

| MMP+ | 1-methyl-4-phenylpyridinium ion |

| MitoSOX | mitochondrial superoxide indicator |

| NAC | N-Acetylcysteine |

| NECRO | Necrostatin-1 |

| NHDF | Normal Human Dermal Fibroblasts |

| OCR | oxygen consumption rate |

| PEP | Pepstatin A |

| PFKM | phosphofructokinase, muscle |

| PFKP | phosphofructokinase, Platelet isoform |

| PI | Propidium Iodide |

| PKM | pyruvate kinase M1/2 |

| QVD | Q-VD-OPh |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| SHI | Shikonin |

| SIR | Siramesine |

| SOD | superoxide dismutase |

| TCA | tricarboxylic acid |

| TPI1 | triosephosphate isomerase 1 |

| siRNA | small interfering RNA |

| WORT | Wortmannin |

References

- Erdei, E.; Torres, S.M. A new understanding in the epidemiology of melanoma. Expert review of anticancer therapy 2010, 10, 1811-1823. [CrossRef]

- Bray, F.; Laversanne, M.; Sung, H.; Ferlay, J.; Siegel, R.L.; Soerjomataram, I.; Jemal, A. Global cancer statistics 2022: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA: a cancer journal for clinicians 2024, 74, 229-263. [CrossRef]

- Rebecca, V.W.; Somasundaram, R.; Herlyn, M. Pre-clinical modeling of cutaneous melanoma. Nature communications 2020, 11, 2858. [CrossRef]

- Kakadia, S.; Yarlagadda, N.; Awad, R.; Kundranda, M.; Niu, J.; Naraev, B.; Mina, L.; Dragovich, T.; Gimbel, M.; Mahmoud, F. Mechanisms of resistance to BRAF and MEK inhibitors and clinical update of US Food and Drug Administration-approved targeted therapy in advanced melanoma. OncoTargets and therapy 2018, 11, 7095-7107. [CrossRef]

- Ferretta, A.; Maida, I.; Guida, S.; Azzariti, A.; Porcelli, L.; Tommasi, S.; Zanna, P.; Cocco, T.; Guida, M.; Guida, G. New insight into the role of metabolic reprogramming in melanoma cells harboring BRAF mutations. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2016, 1863, 2710-2718. [CrossRef]

- Scott, D.A.; Richardson, A.D.; Filipp, F.V.; Knutzen, C.A.; Chiang, G.G.; Ronai, Z.A.; Osterman, A.L.; Smith, J.W. Comparative metabolic flux profiling of melanoma cell lines: beyond the Warburg effect. The Journal of biological chemistry 2011, 286, 42626-42634. [CrossRef]

- Pajak, B.; Siwiak, E.; Sołtyka, M.; Priebe, A.; Zieliński, R.; Fokt, I.; Ziemniak, M.; Jaśkiewicz, A.; Borowski, R.; Domoradzki, T.; et al. 2-Deoxy-d-Glucose and Its Analogs: From Diagnostic to Therapeutic Agents. International journal of molecular sciences 2019, 21. [CrossRef]

- Giammarioli, A.M.; Gambardella, L.; Barbati, C.; Pietraforte, D.; Tinari, A.; Alberton, M.; Gnessi, L.; Griffin, R.J.; Minetti, M.; Malorni, W. Differential effects of the glycolysis inhibitor 2-deoxy-D-glucose on the activity of pro-apoptotic agents in metastatic melanoma cells, and induction of a cytoprotective autophagic response. International journal of cancer 2012, 131, E337-347. [CrossRef]

- Pattni, B.S.; Jhaveri, A.; Dutta, I.; Baleja, J.D.; Degterev, A.; Torchilin, V. Targeting energy metabolism of cancer cells: Combined administration of NCL-240 and 2-DG. International journal of pharmaceutics 2017, 532, 149-156. [CrossRef]

- Hill-Mündel, K.; Nohr, D. Cytotoxic activity of high dose ascorbic acid is enhanced by 2-deoxy-d-glucose in glycolytic melanoma cells. Biochemical and biophysical research communications 2021, 546, 90-96. [CrossRef]

- Malyarenko, O.S.; Usoltseva, R.V.; Silchenko, A.S.; Zueva, A.O.; Ermakova, S.P. The Combined Metabolically Oriented Effect of Fucoidan from the Brown Alga Saccharina cichorioides and Its Carboxymethylated Derivative with 2-Deoxy-D-Glucose on Human Melanoma Cells. International journal of molecular sciences 2023, 24. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Jiang, C.C.; Lavis, C.J.; Croft, A.; Dong, L.; Tseng, H.Y.; Yang, F.; Tay, K.H.; Hersey, P.; Zhang, X.D. 2-Deoxy-D-glucose enhances TRAIL-induced apoptosis in human melanoma cells through XBP-1-mediated up-regulation of TRAIL-R2. Molecular cancer 2009, 8, 122. [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.; Kurtoglu, M.; León-Annicchiarico, C.L.; Munoz-Pinedo, C.; Barredo, J.; Leclerc, G.; Merchan, J.; Liu, X.; Lampidis, T.J. Combining 2-deoxy-D-glucose with fenofibrate leads to tumor cell death mediated by simultaneous induction of energy and ER stress. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 36461-36473. [CrossRef]

- Raez, L.E.; Papadopoulos, K.; Ricart, A.D.; Chiorean, E.G.; Dipaola, R.S.; Stein, M.N.; Rocha Lima, C.M.; Schlesselman, J.J.; Tolba, K.; Langmuir, V.K.; et al. A phase I dose-escalation trial of 2-deoxy-D-glucose alone or combined with docetaxel in patients with advanced solid tumors. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology 2013, 71, 523-530. [CrossRef]

- Singh, D.; Banerji, A.K.; Dwarakanath, B.S.; Tripathi, R.P.; Gupta, J.P.; Mathew, T.L.; Ravindranath, T.; Jain, V. Optimizing cancer radiotherapy with 2-deoxy-d-glucose dose escalation studies in patients with glioblastoma multiforme. Strahlentherapie und Onkologie : Organ der Deutschen Rontgengesellschaft ... [et al] 2005, 181, 507-514. [CrossRef]

- Stein, M.; Lin, H.; Jeyamohan, C.; Dvorzhinski, D.; Gounder, M.; Bray, K.; Eddy, S.; Goodin, S.; White, E.; Dipaola, R.S. Targeting tumor metabolism with 2-deoxyglucose in patients with castrate-resistant prostate cancer and advanced malignancies. The Prostate 2010, 70, 1388-1394. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, C.H.; Lee, K.J.; Chiu, Y.H.; Huang, K.C.; Wang, G.S.; Chen, L.P.; Liao, K.W.; Lin, C.S. The Lysosome in Malignant Melanoma: Biology, Function and Therapeutic Applications. Cells 2022, 11. [CrossRef]

- Berg, A.L.; Rowson-Hodel, A.; Wheeler, M.R.; Hu, M.; Free, S.R.; Carraway, K.L., III. III. Engaging the Lysosome and Lysosome-Dependent Cell Death in Cancer. In Breast Cancer; Mayrovitz, H.N., Ed.; Exon Publications: Brisbane (AU), 2022; pp. 123–135.

- Yin, M.; Soikkeli, J.; Jahkola, T.; Virolainen, S.; Saksela, O.; Hölttä, E. TGF-β signaling, activated stromal fibroblasts, and cysteine cathepsins B and L drive the invasive growth of human melanoma cells. The American journal of pathology 2012, 181, 2202-2216. [CrossRef]

- Paunovic, V.; Kosic, M.; Misirkic-Marjanovic, M.; Trajkovic, V.; Harhaji-Trajkovic, L. Dual targeting of tumor cell energy metabolism and lysosomes as an anticancer strategy. Biochimica et biophysica acta. Molecular cell research 2021, 1868, 118944. [CrossRef]

- Kosic, M.; Arsikin-Csordas, K.; Paunovic, V.; Firestone, R.A.; Ristic, B.; Mircic, A.; Petricevic, S.; Bosnjak, M.; Zogovic, N.; Mandic, M.; et al. Synergistic Anticancer Action of Lysosomal Membrane Permeabilization and Glycolysis Inhibition. The Journal of biological chemistry 2016, 291, 22936-22948. [CrossRef]

- Harhaji-Trajkovic, L.; Arsikin, K.; Kravic-Stevovic, T.; Petricevic, S.; Tovilovic, G.; Pantovic, A.; Zogovic, N.; Ristic, B.; Janjetovic, K.; Bumbasirevic, V.; et al. Chloroquine-mediated lysosomal dysfunction enhances the anticancer effect of nutrient deprivation. Pharmaceutical research 2012, 29, 2249-2263. [CrossRef]

- Jo, M.H.; Kim, Y.T.; Park, S.J. Dieckol Inhibits Autophagic Flux and Induces Apoptotic Cell Death in A375 Human Melanoma Cells via Lysosomal Dysfunction and Mitochondrial Membrane Impairment. International journal of molecular sciences 2022, 23. [CrossRef]

- Chang, S.H.; Lin, P.Y.; Wu, T.K.; Hsu, C.S.; Huang, S.W.; Li, Z.Y.; Liu, K.T.; Kao, J.K.; Chen, Y.J.; Wong, T.W.; et al. Imiquimod-induced ROS production causes lysosomal membrane permeabilization and activates caspase-8-mediated apoptosis in skin cancer cells. Journal of dermatological science 2022, 107, 142-150. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Ding, K.; Ji, J.; Parajuli, H.; Aasen, S.N.; Espedal, H.; Huang, B.; Chen, A.; Wang, J.; Li, X.; et al. Trifluoperazine prolongs the survival of experimental brain metastases by STAT3-dependent lysosomal membrane permeabilization. American journal of cancer research 2020, 10, 545-563.

- Noguchi, S.; Shibutani, S.; Fukushima, K.; Mori, T.; Igase, M.; Mizuno, T. Bosutinib, an SRC inhibitor, induces caspase-independent cell death associated with permeabilization of lysosomal membranes in melanoma cells. Veterinary and comparative oncology 2018, 16, 69-76. [CrossRef]

- Al Sinani, S.S.; Eltayeb, E.A.; Coomber, B.L.; Adham, S.A. Solamargine triggers cellular necrosis selectively in different types of human melanoma cancer cells through extrinsic lysosomal mitochondrial death pathway. Cancer cell international 2016, 16, 11. [CrossRef]

- Thiele, D.L.; Lipsky, P.E. Mechanism of L-leucyl-L-leucine methyl ester-mediated killing of cytotoxic lymphocytes: dependence on a lysosomal thiol protease, dipeptidyl peptidase I, that is enriched in these cells. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 1990, 87, 83-87. [CrossRef]

- Bussi, C.; Heunis, T.; Pellegrino, E.; Bernard, E.M.; Bah, N.; Dos Santos, M.S.; Santucci, P.; Aylan, B.; Rodgers, A.; Fearns, A.; et al. Lysosomal damage drives mitochondrial proteome remodelling and reprograms macrophage immunometabolism. Nature communications 2022, 13, 7338. [CrossRef]

- Droga-Mazovec, G.; Bojic, L.; Petelin, A.; Ivanova, S.; Romih, R.; Repnik, U.; Salvesen, G.S.; Stoka, V.; Turk, V.; Turk, B. Cysteine cathepsins trigger caspase-dependent cell death through cleavage of bid and antiapoptotic Bcl-2 homologues. The Journal of biological chemistry 2008, 283, 19140-19150. [CrossRef]

- Cirman, T.; Oresić, K.; Mazovec, G.D.; Turk, V.; Reed, J.C.; Myers, R.M.; Salvesen, G.S.; Turk, B. Selective disruption of lysosomes in HeLa cells triggers apoptosis mediated by cleavage of Bid by multiple papain-like lysosomal cathepsins. The Journal of biological chemistry 2004, 279, 3578-3587. [CrossRef]

- Kavčič, N.; Butinar, M.; Sobotič, B.; Hafner Česen, M.; Petelin, A.; Bojić, L.; Zavašnik Bergant, T.; Bratovš, A.; Reinheckel, T.; Turk, B. Intracellular cathepsin C levels determine sensitivity of cells to leucyl-leucine methyl ester-triggered apoptosis. The FEBS journal 2020, 287, 5148-5166. [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, I.; Vainikka, L.; Wäster, P.; Öllinger, K. Lysosomal Function and Intracellular Position Determine the Malignant Phenotype in Malignant Melanoma. The Journal of investigative dermatology 2023, 143, 1769-1778.e1712. [CrossRef]

- Plana, D.; Palmer, A.C.; Sorger, P.K. Independent Drug Action in Combination Therapy: Implications for Precision Oncology. Cancer discovery 2022, 12, 606-624. [CrossRef]

- Kaludjerović, G.N.; Miljković, D.; Momcilović, M.; Djinović, V.M.; Mostarica Stojković, M.; Sabo, T.J.; Trajković, V. Novel platinum(IV) complexes induce rapid tumor cell death in vitro. International journal of cancer 2005, 116, 479-486. [CrossRef]

- Kosic, M.; Paunovic, V.; Ristic, B.; Mircic, A.; Bosnjak, M.; Stevanovic, D.; Kravic-Stevovic, T.; Trajkovic, V.; Harhaji-Trajkovic, L. 3-Methyladenine prevents energy stress-induced necrotic death of melanoma cells through autophagy-independent mechanisms. Journal of pharmacological sciences 2021, 147, 156-167. [CrossRef]

- Talantov, D.; Mazumder, A.; Yu, J.X.; Briggs, T.; Jiang, Y.; Backus, J.; Atkins, D.; Wang, Y. Novel genes associated with malignant melanoma but not benign melanocytic lesions. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 2005, 11, 7234-7242. [CrossRef]

- Feise, R.J. Do multiple outcome measures require p-value adjustment? BMC medical research methodology 2002, 2, 8. [CrossRef]

- Eriksson, I.; Wäster, P.; Öllinger, K. Restoration of lysosomal function after damage is accompanied by recycling of lysosomal membrane proteins. Cell death & disease 2020, 11, 370. [CrossRef]

- Yoshimori, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Moriyama, Y.; Futai, M.; Tashiro, Y. Bafilomycin A1, a specific inhibitor of vacuolar-type H(+)-ATPase, inhibits acidification and protein degradation in lysosomes of cultured cells. The Journal of biological chemistry 1991, 266, 17707-17712.

- Repnik, U.; Borg Distefano, M.; Speth, M.T.; Ng, M.Y.W.; Progida, C.; Hoflack, B.; Gruenberg, J.; Griffiths, G. L-leucyl-L-leucine methyl ester does not release cysteine cathepsins to the cytosol but inactivates them in transiently permeabilized lysosomes. Journal of cell science 2017, 130, 3124-3140. [CrossRef]

- Costanzi, E.; Kuzikov, M.; Esposito, F.; Albani, S.; Demitri, N.; Giabbai, B.; Camasta, M.; Tramontano, E.; Rossetti, G.; Zaliani, A.; et al. Structural and Biochemical Analysis of the Dual Inhibition of MG-132 against SARS-CoV-2 Main Protease (Mpro/3CLpro) and Human Cathepsin-L. International journal of molecular sciences 2021, 22. [CrossRef]

- Falke, S.; Lieske, J.; Herrmann, A.; Loboda, J.; Karničar, K.; Günther, S.; Reinke, P.Y.A.; Ewert, W.; Usenik, A.; Lindič, N.; et al. Structural Elucidation and Antiviral Activity of Covalent Cathepsin L Inhibitors. Journal of medicinal chemistry 2024, 67, 7048-7067. [CrossRef]

- Brojatsch, J.; Lima, H.; Kar, A.K.; Jacobson, L.S.; Muehlbauer, S.M.; Chandran, K.; Diaz-Griffero, F. A proteolytic cascade controls lysosome rupture and necrotic cell death mediated by lysosome-destabilizing adjuvants. PloS one 2014, 9, e95032. [CrossRef]

- Knight, C.G.; Barrett, A.J. Interaction of human cathepsin D with the inhibitor pepstatin. The Biochemical journal 1976, 155, 117-125. [CrossRef]

- Pontious, C.; Kaul, S.; Hong, M.; Hart, P.A.; Krishna, S.G.; Lara, L.F.; Conwell, D.L.; Cruz-Monserrate, Z. Cathepsin E expression and activity: Role in the detection and treatment of pancreatic cancer. Pancreatology : official journal of the International Association of Pancreatology (IAP) ... [et al.] 2019, 19, 951-956. [CrossRef]

- Kannan, K.; Jain, S.K. Oxidative stress and apoptosis. Pathophysiology : the official journal of the International Society for Pathophysiology 2000, 7, 153-163. [CrossRef]

- Choi, K.; Kim, J.; Kim, G.W.; Choi, C. Oxidative stress-induced necrotic cell death via mitochondira-dependent burst of reactive oxygen species. Current neurovascular research 2009, 6, 213-222. [CrossRef]

- Bernardi, P.; Gerle, C.; Halestrap, A.P.; Jonas, E.A.; Karch, J.; Mnatsakanyan, N.; Pavlov, E.; Sheu, S.S.; Soukas, A.A. Identity, structure, and function of the mitochondrial permeability transition pore: controversies, consensus, recent advances, and future directions. Cell death and differentiation 2023, 30, 1869-1885. [CrossRef]

- Tsujimoto, Y.; Shimizu, S. Role of the mitochondrial membrane permeability transition in cell death. Apoptosis : an international journal on programmed cell death 2007, 12, 835-840. [CrossRef]

- Roussel, D.; Janillon, S.; Teulier, L.; Pichaud, N. Succinate oxidation rescues mitochondrial ATP synthesis at high temperature in Drosophila melanogaster. FEBS letters 2023, 597, 2221-2229. [CrossRef]

- Iossa, S.; Mollica, M.P.; Lionetti, L.; Crescenzo, R.; Botta, M.; Barletta, A.; Liverini, G. Acetyl-L-carnitine supplementation differently influences nutrient partitioning, serum leptin concentration and skeletal muscle mitochondrial respiration in young and old rats. The Journal of nutrition 2002, 132, 636-642. [CrossRef]

- Sanchez, W.Y.; McGee, S.L.; Connor, T.; Mottram, B.; Wilkinson, A.; Whitehead, J.P.; Vuckovic, S.; Catley, L. Dichloroacetate inhibits aerobic glycolysis in multiple myeloma cells and increases sensitivity to bortezomib. British journal of cancer 2013, 108, 1624-1633. [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Xie, J.; Jiang, Z.; Wang, B.; Wang, Y.; Hu, X. Shikonin and its analogs inhibit cancer cell glycolysis by targeting tumor pyruvate kinase-M2. Oncogene 2011, 30, 4297-4306. [CrossRef]

- Xi, H.; Kurtoglu, M.; Lampidis, T.J. The wonders of 2-deoxy-D-glucose. IUBMB life 2014, 66, 110-121. [CrossRef]

- Xi, H.; Kurtoglu, M.; Liu, H.; Wangpaichitr, M.; You, M.; Liu, X.; Savaraj, N.; Lampidis, T.J. 2-Deoxy-D-glucose activates autophagy via endoplasmic reticulum stress rather than ATP depletion. Cancer chemotherapy and pharmacology 2011, 67, 899-910. [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.M.; Huang, J.J.; Du, J.J.; Zhang, N.; Long, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhong, F.F.; Zheng, B.W.; Shen, Y.F.; Huang, Z.; et al. Autophagy inhibitors increase the susceptibility of KRAS-mutant human colorectal cancer cells to a combined treatment of 2-deoxy-D-glucose and lovastatin. Acta pharmacologica Sinica 2021, 42, 1875-1887. [CrossRef]

- Jeon, J.Y.; Kim, S.W.; Park, K.C.; Yun, M. The bifunctional autophagic flux by 2-deoxyglucose to control survival or growth of prostate cancer cells. BMC cancer 2015, 15, 623. [CrossRef]

- Qi, Z.; Yang, W.; Xue, B.; Chen, T.; Lu, X.; Zhang, R.; Li, Z.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, Y.; Han, F.; et al. ROS-mediated lysosomal membrane permeabilization and autophagy inhibition regulate bleomycin-induced cellular senescence. Autophagy 2024, 20, 2000-2016. [CrossRef]

- Otomo, T.; Yoshimori, T. Lysophagy: A Method for Monitoring Lysosomal Rupture Followed by Autophagy-Dependent Recovery. Methods in molecular biology (Clifton, N.J.) 2017, 1594, 141-149. [CrossRef]

- Maejima, I.; Takahashi, A.; Omori, H.; Kimura, T.; Takabatake, Y.; Saitoh, T.; Yamamoto, A.; Hamasaki, M.; Noda, T.; Isaka, Y.; et al. Autophagy sequesters damaged lysosomes to control lysosomal biogenesis and kidney injury. The EMBO journal 2013, 32, 2336-2347. [CrossRef]

- Zein, L.; Dietrich, M.; Balta, D.; Bader, V.; Scheuer, C.; Zellner, S.; Weinelt, N.; Vandrey, J.; Mari, M.C.; Behrends, C.; et al. Linear ubiquitination at damaged lysosomes induces local NFKB activation and controls cell survival. Autophagy 2025, 21, 1075-1095. [CrossRef]

- Jia, J.; Claude-Taupin, A.; Gu, Y.; Choi, S.W.; Peters, R.; Bissa, B.; Mudd, M.H.; Allers, L.; Pallikkuth, S.; Lidke, K.A.; et al. Galectin-3 Coordinates a Cellular System for Lysosomal Repair and Removal. Developmental cell 2020, 52, 69-87.e68. [CrossRef]

- Park, N.Y.; Jo, D.S.; Kim, Y.H.; Bae, J.E.; Kim, J.B.; Park, H.J.; Choi, J.Y.; Lee, H.J.; Chang, J.H.; Bunch, H.; et al. Triamterene induces autophagic degradation of lysosome by exacerbating lysosomal integrity. Archives of pharmacal research 2021, 44, 621-631. [CrossRef]

- Aft, R.L.; Zhang, F.W.; Gius, D. Evaluation of 2-deoxy-D-glucose as a chemotherapeutic agent: mechanism of cell death. British journal of cancer 2002, 87, 805-812. [CrossRef]

- Kano, A.; Fujiki, M.; Fukami, K.; Shindo, M.; Kang, J.-H. Bongkrekic acid inhibits 2-deoxygulcose-induced apoptosis, leading to enhanced cytotoxicity and necrotic cell death. Pharmacological Research - Reports 2024, 2, 100017. [CrossRef]

- Uchimoto, T.; Nohara, H.; Kamehara, R.; Iwamura, M.; Watanabe, N.; Kobayashi, Y. Mechanism of apoptosis induced by a lysosomotropic agent, L-Leucyl-L-Leucine methyl ester. Apoptosis : an international journal on programmed cell death 1999, 4, 357-362. [CrossRef]

- Thiele, D.L.; Lipsky, P.E. Apoptosis is induced in cells with cytolytic potential by L-leucyl-L-leucine methyl ester. Journal of immunology (Baltimore, Md. : 1950) 1992, 148, 3950-3957.

- Jacobson, L.S.; Lima, H., Jr.; Goldberg, M.F.; Gocheva, V.; Tsiperson, V.; Sutterwala, F.S.; Joyce, J.A.; Gapp, B.V.; Blomen, V.A.; Chandran, K.; et al. Cathepsin-mediated necrosis controls the adaptive immune response by Th2 (T helper type 2)-associated adjuvants. The Journal of biological chemistry 2013, 288, 7481-7491. [CrossRef]

- Brojatsch, J.; Lima, H., Jr.; Palliser, D.; Jacobson, L.S.; Muehlbauer, S.M.; Furtado, R.; Goldman, D.L.; Lisanti, M.P.; Chandran, K. Distinct cathepsins control necrotic cell death mediated by pyroptosis inducers and lysosome-destabilizing agents. Cell cycle (Georgetown, Tex.) 2015, 14, 964-972. [CrossRef]

- Champa, D.; Orlacchio, A.; Patel, B.; Ranieri, M.; Shemetov, A.A.; Verkhusha, V.V.; Cuervo, A.M.; Di Cristofano, A. Obatoclax kills anaplastic thyroid cancer cells by inducing lysosome neutralization and necrosis. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 34453-34471. [CrossRef]

- Tsujimoto, Y. Apoptosis and necrosis: intracellular ATP level as a determinant for cell death modes. Cell death and differentiation 1997, 4, 429-434. [CrossRef]

- Zorova, L.D.; Popkov, V.A.; Plotnikov, E.Y.; Silachev, D.N.; Pevzner, I.B.; Jankauskas, S.S.; Babenko, V.A.; Zorov, S.D.; Balakireva, A.V.; Juhaszova, M.; et al. Mitochondrial membrane potential. Analytical biochemistry 2018, 552, 50-59. [CrossRef]

- Murphy, M.P. How mitochondria produce reactive oxygen species. The Biochemical journal 2009, 417, 1-13. [CrossRef]

- Zorov, D.B.; Filburn, C.R.; Klotz, L.O.; Zweier, J.L.; Sollott, S.J. Reactive oxygen species (ROS)-induced ROS release: a new phenomenon accompanying induction of the mitochondrial permeability transition in cardiac myocytes. The Journal of experimental medicine 2000, 192, 1001-1014. [CrossRef]

- Ni, J.; Wu, Z.; Stoka, V.; Meng, J.; Hayashi, Y.; Peters, C.; Qing, H.; Turk, V.; Nakanishi, H. Increased expression and altered subcellular distribution of cathepsin B in microglia induce cognitive impairment through oxidative stress and inflammatory response in mice. Aging cell 2019, 18, e12856. [CrossRef]

- Perry, J.J.; Shin, D.S.; Getzoff, E.D.; Tainer, J.A. The structural biochemistry of the superoxide dismutases. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2010, 1804, 245-262. [CrossRef]

- Kurz, T.; Terman, A.; Gustafsson, B.; Brunk, U.T. Lysosomes in iron metabolism, ageing and apoptosis. Histochemistry and cell biology 2008, 129, 389-406. [CrossRef]

- Scarpellini, C.; Klejborowska, G.; Lanthier, C.; Hassannia, B.; Vanden Berghe, T.; Augustyns, K. Beyond ferrostatin-1: a comprehensive review of ferroptosis inhibitors. Trends in pharmacological sciences 2023, 44, 902-916. [CrossRef]

- Cai, W.; Cheng, J.; Zong, S.; Yu, Y.; Wang, Y.; Song, Y.; He, R.; Yuan, S.; Chen, T.; Hu, M.; et al. The glycolysis inhibitor 2-deoxyglucose ameliorates adjuvant-induced arthritis by regulating macrophage polarization in an AMPK-dependent manner. Molecular immunology 2021, 140, 186-195. [CrossRef]

- Sinthupibulyakit, C.; Ittarat, W.; St Clair, W.H.; St Clair, D.K. p53 Protects lung cancer cells against metabolic stress. International journal of oncology 2010, 37, 1575-1581. [CrossRef]

- Maximchik, P.; Abdrakhmanov, A.; Inozemtseva, E.; Tyurin-Kuzmin, P.A.; Zhivotovsky, B.; Gogvadze, V. 2-Deoxy-D-glucose has distinct and cell line-specific effects on the survival of different cancer cells upon antitumor drug treatment. The FEBS journal 2018, 285, 4590-4601. [CrossRef]

- Dodson, M.; Benavides, G.A.; Darley-Usmar, V.; Zhang, J. Differential Effects of 2-Deoxyglucose and Glucose Deprivation on 4-Hydroxynonenal Dependent Mitochondrial Dysfunction in Primary Neurons. Frontiers in aging 2022, 3, 812810. [CrossRef]

- Weiss-Sadan, T.; Itzhak, G.; Kaschani, F.; Yu, Z.; Mahameed, M.; Anaki, A.; Ben-Nun, Y.; Merquiol, E.; Tirosh, B.; Kessler, B.; et al. Cathepsin L Regulates Metabolic Networks Controlling Rapid Cell Growth and Proliferation. Molecular & cellular proteomics : MCP 2019, 18, 1330-1344. [CrossRef]

- Pradelli, L.A.; Villa, E.; Zunino, B.; Marchetti, S.; Ricci, J.E. Glucose metabolism is inhibited by caspases upon the induction of apoptosis. Cell death & disease 2014, 5, e1406. [CrossRef]

- Owen, L.; Sunram-Lea, S.I. Metabolic agents that enhance ATP can improve cognitive functioning: a review of the evidence for glucose, oxygen, pyruvate, creatine, and L-carnitine. Nutrients 2011, 3, 735-755. [CrossRef]

- Nowak, G.; Clifton, G.L.; Bakajsova, D. Succinate ameliorates energy deficits and prevents dysfunction of complex I in injured renal proximal tubular cells. The Journal of pharmacology and experimental therapeutics 2008, 324, 1155-1162. [CrossRef]

- Tretter, L.; Patocs, A.; Chinopoulos, C. Succinate, an intermediate in metabolism, signal transduction, ROS, hypoxia, and tumorigenesis. Biochimica et biophysica acta 2016, 1857, 1086-1101. [CrossRef]

- Lu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, Y.; Shi, S.; Hu, H.; Li, X.; Niu, Y.; Qi, H.; Ji, S.; Duan, X.; et al. Long non-coding RNA CYTOR promotes the progression of melanoma via the miR-485-5p/GPI axis. PeerJ 2025, 13, e19284. [CrossRef]

- Suzuki, A.; Iizuka, A.; Komiyama, M.; Takikawa, M.; Kume, A.; Tai, S.; Ohshita, C.; Kurusu, A.; Nakamura, Y.; Yamamoto, A.; et al. Identification of melanoma antigens using a Serological Proteome Approach (SERPA). Cancer genomics & proteomics 2010, 7, 17-23.

- Giricz, O.; Lauer-Fields, J.L.; Fields, G.B. The normalization of gene expression data in melanoma: investigating the use of glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase and 18S ribosomal RNA as internal reference genes for quantitative real-time PCR. Analytical biochemistry 2008, 380, 137-139. [CrossRef]

- Nájera, L.; Alonso-Juarranz, M.; Garrido, M.; Ballestín, C.; Moya, L.; Martínez-Díaz, M.; Carrillo, R.; Juarranz, A.; Rojo, F.; Cuezva, J.M.; et al. Prognostic implications of markers of the metabolic phenotype in human cutaneous melanoma. The British journal of dermatology 2019, 181, 114-127. [CrossRef]

- Zerhouni, M.; Martin, A.R.; Furstoss, N.; Gutierrez, V.S.; Jaune, E.; Tekaya, N.; Beranger, G.E.; Abbe, P.; Regazzetti, C.; Amdouni, H.; et al. Dual Covalent Inhibition of PKM and IMPDH Targets Metabolism in Cutaneous Metastatic Melanoma. Cancer research 2021, 81, 3806-3821. [CrossRef]

- Feichtinger, R.G.; Lang, R.; Geilberger, R.; Rathje, F.; Mayr, J.A.; Sperl, W.; Bauer, J.W.; Hauser-Kronberger, C.; Kofler, B.; Emberger, M. Melanoma tumors exhibit a variable but distinct metabolic signature. Experimental dermatology 2018, 27, 204-207. [CrossRef]

- Zhuang, L.; Scolyer, R.A.; Murali, R.; McCarthy, S.W.; Zhang, X.D.; Thompson, J.F.; Hersey, P. Lactate dehydrogenase 5 expression in melanoma increases with disease progression and is associated with expression of Bcl-XL and Mcl-1, but not Bcl-2 proteins. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc 2010, 23, 45-53. [CrossRef]

- Pamidimukkala, N.V.; Leonard, M.K.; Snyder, D.; McCorkle, J.R.; Kaetzel, D.M. Metastasis Suppressor NME1 Directly Activates Transcription of the ALDOC Gene in Melanoma Cells. Anticancer research 2018, 38, 6059-6068. [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Zhang, X. Glycolysis regulator PFKP induces human melanoma cell proliferation and tumor growth. Clinical & translational oncology : official publication of the Federation of Spanish Oncology Societies and of the National Cancer Institute of Mexico 2023, 25, 2183-2191. [CrossRef]

- Linge, A.; Kennedy, S.; O’Flynn, D.; Beatty, S.; Moriarty, P.; Henry, M.; Clynes, M.; Larkin, A.; Meleady, P. Differential expression of fourteen proteins between uveal melanoma from patients who subsequently developed distant metastases versus those who did Not. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2012, 53, 4634-4643. [CrossRef]

- Ramasamy, P.; Murphy, C.C.; Clynes, M.; Horgan, N.; Moriarty, P.; Tiernan, D.; Beatty, S.; Kennedy, S.; Meleady, P. Proteomics in uveal melanoma. Experimental eye research 2014, 118, 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Guo, X.; Yu, X.; Li, F.; Xia, Q.; Ren, H.; Chen, Z.; Xing, Y. Identification of Survival-Related Metabolic Genes and a Novel Gene Signature Predicting the Overall Survival for Patients with Uveal Melanoma. Ophthalmic research 2022, 65, 516-528. [CrossRef]

- Bradshaw, G.; Haupt, L.M.; Aquino, E.M.; Lea, R.A.; Sutherland, H.G.; Griffiths, L.R. Single Nucleotide Polymorphisms in MIR143 Contribute to Protection Against Non-Hodgkin Lymphoma (NHL) in Caucasian Populations. Genes 2019, 10. [CrossRef]

- Pudova, E.A.; Kudryavtseva, A.V.; Fedorova, M.S.; Zaretsky, A.R.; Shcherbo, D.S.; Lukyanova, E.N.; Popov, A.Y.; Sadritdinova, A.F.; Abramov, I.S.; Kharitonov, S.L.; et al. HK3 overexpression associated with epithelial-mesenchymal transition in colorectal cancer. BMC genomics 2018, 19, 113. [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Liu, W.R.; Xu, Y.; Tian, X.; Anwaier, A.; Su, J.Q.; Zhu, W.K.; Shi, G.H.; Wei, G.M.; Huang, Y.P.; et al. Hexokinase 3 dysfunction promotes tumorigenesis and immune escape by upregulating monocyte/macrophage infiltration into the clear cell renal cell carcinoma microenvironment. International journal of biological sciences 2021, 17, 2205-2222. [CrossRef]

- Harami-Papp, H.; Pongor, L.S.; Munkácsy, G.; Horváth, G.; Nagy Á, M.; Ambrus, A.; Hauser, P.; Szabó, A.; Tretter, L.; Győrffy, B. TP53 mutation hits energy metabolism and increases glycolysis in breast cancer. Oncotarget 2016, 7, 67183-67195. [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Fu, X.; Liu, R.; Yan, L.; Yang, Y. Exploring the prognostic value of HK3 and its association with immune infiltration in glioblastoma multiforme. Frontiers in genetics 2022, 13, 1033572. [CrossRef]

- Wu, X.; Mi, T.; Jin, L.; Ren, C.; Wang, J.; Zhang, Z.; Liu, J.; Wang, Z.; Guo, P.; He, D. Dual roles of HK3 in regulating the network between tumor cells and tumor-associated macrophages in neuroblastoma. Cancer immunology, immunotherapy : CII 2024, 73, 122. [CrossRef]

- Podhajcer, O.L.; Bover, L.; Bravo, A.I.; Ledda, M.F.; Kairiyama, C.; Calb, I.; Guerra, L.; Capony, F.; Mordoh, J. Expression of cathepsin D in primary and metastatic human melanoma and dysplastic nevi. The Journal of investigative dermatology 1995, 104, 340-344. [CrossRef]

- Bassalyk, L.S.; Tsanev, P.E.; Parshikova, S.M.; Demidov, L.V. [Lysosomal proteolytic enzymes in the processes of melanoma invasion and metastasis]. Voprosy onkologii 1992, 38, 418-425.

- Kos, J.; Stabuc, B.; Schweiger, A.; Krasovec, M.; Cimerman, N.; Kopitar-Jerala, N.; Vrhovec, I. Cathepsins B, H, and L and their inhibitors stefin A and cystatin C in sera of melanoma patients. Clinical cancer research : an official journal of the American Association for Cancer Research 1997, 3, 1815-1822.

- Kageshita, T.; Yoshii, A.; Kimura, T.; Maruo, K.; Ono, T.; Himeno, M.; Nishimura, Y. Biochemical and immunohistochemical analysis of cathepsins B, H, L and D in human melanocytic tumours. Archives of dermatological research.. 1995, 287, 266-272. [CrossRef]

- Bartenjev, I.; Rudolf, Z.; Stabuc, B.; Vrhovec, I.; Perkovic, T.; Kansky, A. Cathepsin D expression in early cutaneous malignant melanoma. International journal of dermatology 2000, 39, 599-602. [CrossRef]

- Fröhlich, E.; Schlagenhauff, B.; Möhrle, M.; Weber, E.; Klessen, C.; Rassner, G. Activity, expression, and transcription rate of the cathepsins B, D, H, and L in cutaneous malignant melanoma. Cancer 2001, 91, 972-982.

- Crabb, J.W.; Hu, B.; Crabb, J.S.; Triozzi, P.; Saunthararajah, Y.; Tubbs, R.; Singh, A.D. iTRAQ Quantitative Proteomic Comparison of Metastatic and Non-Metastatic Uveal Melanoma Tumors. PloS one 2015, 10, e0135543. [CrossRef]

- Zuidervaart, W.; Hensbergen, P.J.; Wong, M.C.; Deelder, A.M.; Tensen, C.P.; Jager, M.J.; Gruis, N.A. Proteomic analysis of uveal melanoma reveals novel potential markers involved in tumor progression. Investigative ophthalmology & visual science 2006, 47, 786-793. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, G.P.; Yue, X.; Li, S.Q. Cathepsin C Interacts with TNF-α/p38 MAPK Signaling Pathway to Promote Proliferation and Metastasis in Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Cancer research and treatment 2020, 52, 10-23. [CrossRef]

- Cheng, X.; Ren, Z.; Liu, Z.; Sun, X.; Qian, R.; Cao, C.; Liu, B.; Wang, J.; Wang, H.; Guo, Y.; et al. Cysteine cathepsin C: a novel potential biomarker for the diagnosis and prognosis of glioma. Cancer cell international 2022, 22, 53. [CrossRef]

- Grilc, S.; Kreft, M.; Luzar, B.; Gabrijel, M.; Bartenjev, M.S.; Zorec, R.; Bartenjev, I. Histological Skin Remodeling Following Autologous Fibroblast Application. Acta dermatovenerologica Croatica : ADC 2022, 30, 1-7.

- Zorina, A.; Zorin, V.; Isaev, A.; Kudlay, D.; Vasileva, M.; Kopnin, P. Dermal Fibroblasts as the Main Target for Skin Anti-Age Correction Using a Combination of Regenerative Medicine Methods. Current issues in molecular biology 2023, 45, 3829-3847. [CrossRef]

- Lam Yi, H.; Than, H.; Sng, C.; Cheong, M.A.; Chuah, C.; Xiang, W. Lysosome Inhibition by Mefloquine Preferentially Enhances the Cytotoxic Effects of Tyrosine Kinase Inhibitors in Blast Phase Chronic Myeloid Leukemia. Translational oncology 2019, 12, 1221-1228. [CrossRef]

- Sukhai, M.A.; Prabha, S.; Hurren, R.; Rutledge, A.C.; Lee, A.Y.; Sriskanthadevan, S.; Sun, H.; Wang, X.; Skrtic, M.; Seneviratne, A.; et al. Lysosomal disruption preferentially targets acute myeloid leukemia cells and progenitors. The Journal of clinical investigation 2013, 123, 315-328. [CrossRef]

- Ostenfeld, M.S.; Fehrenbacher, N.; Høyer-Hansen, M.; Thomsen, C.; Farkas, T.; Jäättelä, M. Effective tumor cell death by sigma-2 receptor ligand siramesine involves lysosomal leakage and oxidative stress. Cancer research 2005, 65, 8975-8983. [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Guéron, M. The inhibition of bovine heart hexokinase by 2-deoxy-D-glucose-6-phosphate: characterization by 31P NMR and metabolic implications. Biochimie 1992, 74, 867-873. [CrossRef]

- Wick, A.N.; Drury, D.R.; Nakada, H.I.; Wolfe, J.B. Localization of the primary metabolic block produced by 2-deoxyglucose. The Journal of biological chemistry 1957, 224, 963-969.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).