Introduction

It is a universal phenomenon in modern society that people feel negative emotions such as anxiety and fear toward mathematics. According to the results of the 2022 PISA (Programme for International Student Assessment) survey conducted by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), 59.8% of 15-year-olds in OECD member countries and 68.8% in Japan responded “completely agree” or “agree” to the statement “I often worry that it will be difficult for me in mathematics classes” (OECD, 2024a). Additionally, 64.9% of 15-year-olds in OECD member countries and 68.6% in Japan responded “completely agree” or “agree” to the statement “I worry that I will get poor marks in mathematics” (OECD, 2024a). These findings suggest that anxiety and fear toward mathematics are widespread and culturally pervasive. Such negative emotions have long been a central focus of affective research in mathematics, beginning with Gough’s (1954) study on “mathemaphobia” and Dreger & Aiken’s (1957) work on “number anxiety” (Batchelor et al., 2019). These constructs have since evolved into what is now widely recognized as math anxiety, a psychological phenomenon extensively studied in educational psychology.

Math anxiety is defined as feelings of tension and apprehension that interfere with the manipulation of numbers and the solving of mathematical problems in a wide variety of contexts, including daily life and academic settings (Ramirez et al., 2018). While math anxiety shares similarities with general anxiety and test anxiety, it is considered a distinct construct. This distinction is supported by research showing a relatively low contribution from shared genetic factors (approximately 9%) and non-shared environmental factors (approximately 4%) in comparison to other types of anxiety (Wang et al., 2014), as well as unique correlation patterns with external criterion variables (Hembree, 1990).

The negative association between math anxiety and math learning and performance is one of the most robust and well-replicated findings in the field. Meta-analyses have consistently shown that math anxiety is significantly negatively correlated with learning motivation (Li et al., 2021), the extent of high school math learning (Hembree, 1990), and math performance (Barroso et al., 2021). Furthermore, longitudinal and panel data studies have demonstrated that math anxiety negatively predicts math learning and performance over time (Ahmed et al., 2012; Gunderson et al., 2018). These findings underscore the importance of identifying instructional practices that can alleviate math anxiety, thereby promoting more positive learning outcomes.

One such instructional practice is cognitive activation by mathematics teachers, which has emerged as a significant factor in reducing math anxiety. Cognitive activation refers to instructional strategies that promote constructive, reflective, and higher-order thinking in learners (Baumert et al., 2010). In mathematics lessons, this often involves encouraging students to reflect on problem-solving processes and providing them with tasks that require extended reasoning (Burge et al., 2015). The core components of cognitive activation include: (1) activating prior knowledge and fostering conceptual understanding, (2) posing problems that engage learners in higher-order thinking, and (3) facilitating meaningful participation in classroom discourse (Lipowsky et al., 2009). These practices align with constructivist learning theories, such as Piaget’s and Vygotsky’s, and emphasize the active, constructive, and interactive modes of learning in the ICAP framework (Chi, 2009).

Empirical research has indicated that cognitive activation can reduce math anxiety. For example, Zuo et al. (2024) used structural equation modeling on data from 17,112 eighth-grade students in China and found that cognitive activation was negatively associated with math anxiety, both directly and indirectly via math self-efficacy. Similarly, Liu et al. (2022) conducted a multilevel analysis on 3,088 fourth-grade students and 57 teachers in China and found a direct negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety. Burge et al. (2015), using PISA 2012 data from England, also reported that cognitive activation was negatively associated with math anxiety. However, given that instructional effectiveness often varies by cultural and national context (e.g., Liu et al., 2022), the extent to which these findings generalize to Japanese students remains unclear.

Notably, most previous studies have focused on linear associations between cognitive activation and math anxiety. However, some evidence suggests a curvilinear (inverted U-shaped) relationship in related outcomes such as mathematics performance, where moderate cognitive activation optimises performance while very low or very high levels impair it (Caro et al., 2016; Nachbauer, 2024). Given the strong link between mathematics performance and math anxiety, it is plausible that a similar non-linear mechanism may operate for anxiety. According to the control-value theory of achievement emotions (Pekrun, 2006; Pekrun & Stephens, 2010), anxiety arises when students perceive high value in academic tasks but low control over outcomes. Thus, cognitive activation may reduce anxiety when tasks are appropriately challenging, but may increase anxiety when demands exceed students’ competence. Complementarily, cognitive load theory (Sweller, 1988) suggests that when task demands overload students’ working memory, cognitive resources become depleted, leading to stress and heightened anxiety. Together, these perspectives indicate that the link between cognitive activation and math anxiety may follow a curvilinear pattern.

Empirical findings are consistent with this theoretical reasoning. For example, Frenzel et al. (2009) demonstrated that perceived teaching quality, including cognitive activation, was systematically related to students’ enjoyment and anxiety. Similarly, Fauth et al. (2014) and Goetz et al. (2013) found that challenging tasks foster interest and reduce boredom only when students can master them. These results suggest that moderate levels of cognitive activation can buffer negative emotions, whereas excessive activation may undermine perceived control and increase anxiety.

In addition, this relationship may be moderated by socioeconomic status (SES). SES reflects access to various resources—economic, social, cultural, and human—that affect educational outcomes (National Centre for Education Statistics, 2012). Burge et al. (2015) found that the negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety was significant only among students with medium to high levels of economic, social, and cultural capital. Although their study focused on England, similar patterns have been observed in other outcomes. For example, Caro et al. (2016) found that cognitive activation had a greater positive impact on academic achievement for students with higher SES. These findings suggest that the effectiveness of cognitive activation may depend on students’ SES, with diminished effects among students with lower SES.

Moreover, it is important to consider both individual-level (Student SES) and contextual-level (School SES) factors. School SES reflects the average SES of the school’s student body and shapes the educational environment through access to material and human resources (Chiu & Khoo, 2005), teacher quality, peer effects (Van Ewijk & Sleegers, 2010), and classroom discipline (Willms, 2010). High-SES schools are generally better equipped to support academic achievement (Perry et al., 2022). In Japan, the school system further stratifies students into academically ranked high schools, often in line with socioeconomic background (Takashiro, 2024; Matsuoka, 2015). Thus, School SES may also moderate the link between cognitive activation and math anxiety, beyond the effects of Student SES alone.

Math self-efficacy—students’ belief in their ability to perform specific tasks—may be another moderating factor. According to Bandura’s (1986) social cognitive theory, math self-efficacy influences motivation, learning engagement, and emotional responses. Students with low math self-efficacy may be less responsive to cognitively demanding instruction, potentially limiting the anxiety-reducing benefits of cognitive activation (Shimizu, 2025). In contrast, students with high math self-efficacy are more likely to engage with cognitively activating tasks, which may reduce their math anxiety. Although prior studies have not directly tested this interaction, research on disciplinary climate in mathematics classrooms has shown that the positive effect of a structured environment on achievement is contingent on students’ level of math self-efficacy (Cheema & Kitsantas, 2014).

Based on this theoretical and empirical background, the present study aims to investigate: (1) the curvilinear effect of cognitive activation on math anxiety and (2) the moderating effects of Student SES, School SES, and Math Self-Efficacy on this relationship.

Hypothesis 1. Cognitive activation has a negative relationship with math anxiety.

Hypothesis 2. Cognitive activation has a negative curvilinear relationship with math anxiety.

-

Hypothesis 3. Student SES moderates the negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety.

3-a. When Student SES is high, the negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety becomes stronger.

3-b. When Student SES is low, the negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety becomes weaker.

-

Hypothesis 4. School SES moderates the negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety.

4-a. When School SES is high, the negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety becomes stronger.

4-b. When School SES is low, the negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety becomes weaker.

-

Hypothesis 5. Math self-efficacy moderates the negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety.

5-a. When math self-efficacy is high, the negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety becomes stronger.

5-b. When math self-efficacy is low, the negative relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety becomes weaker.

Discussion

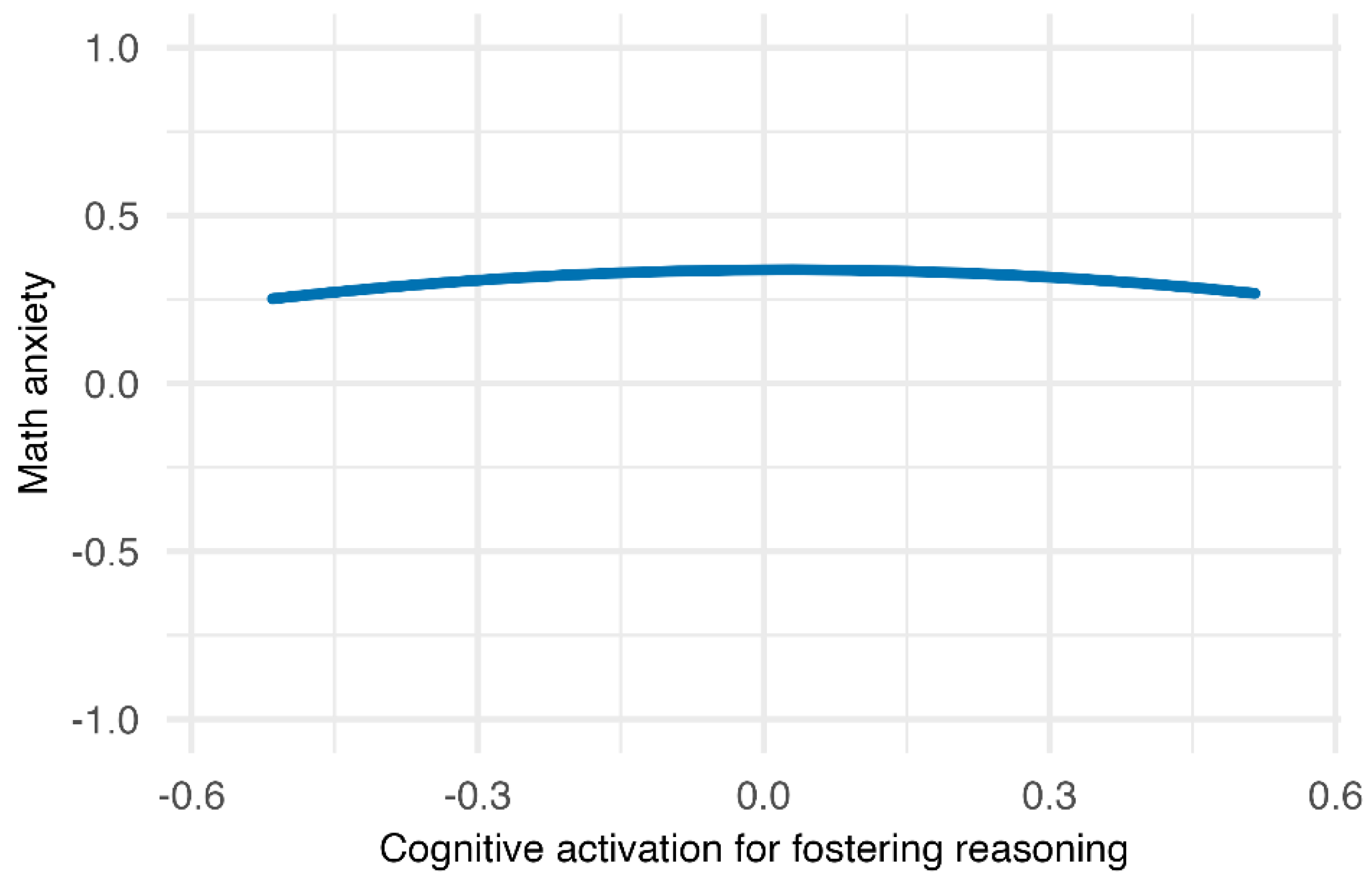

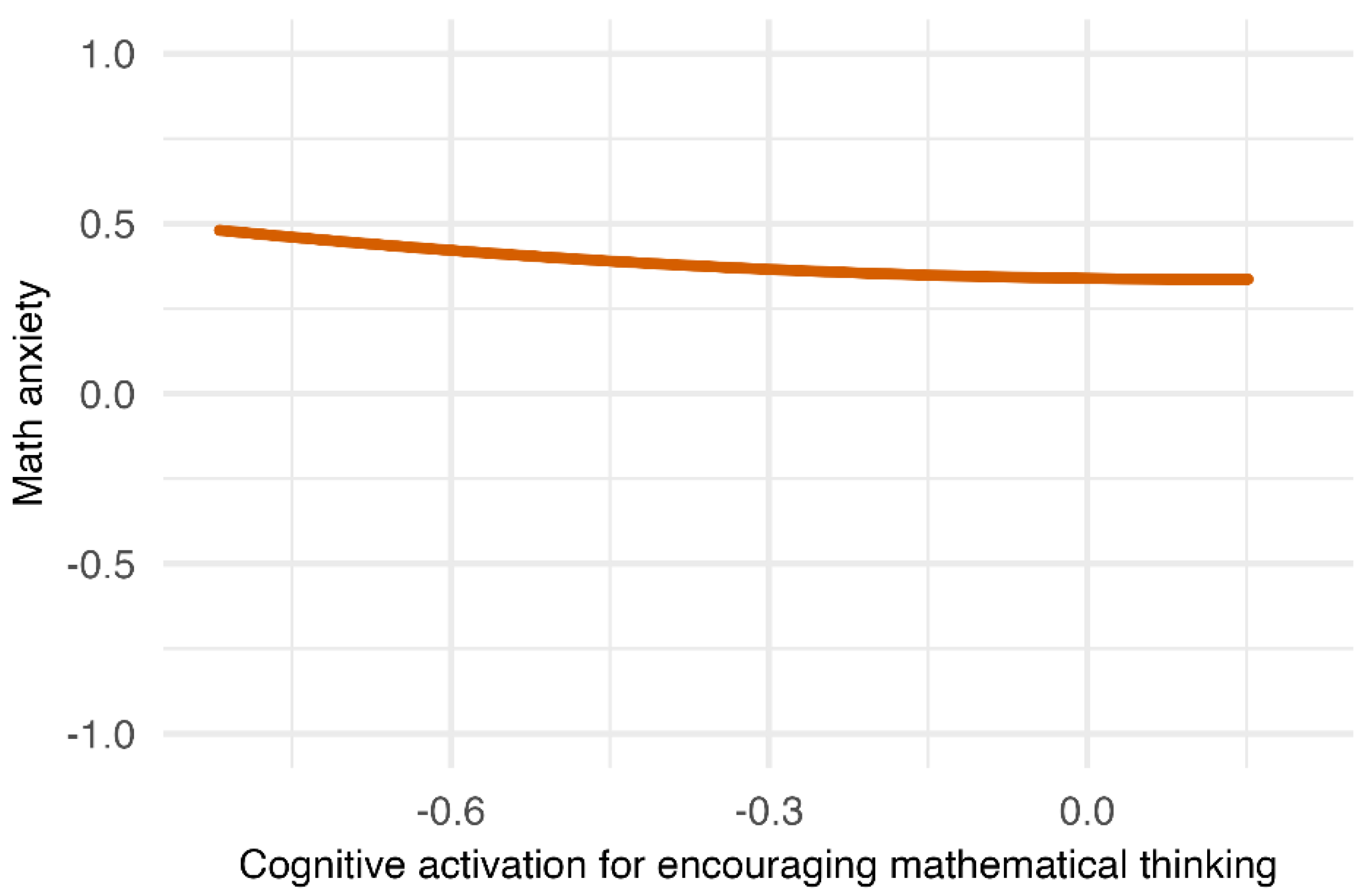

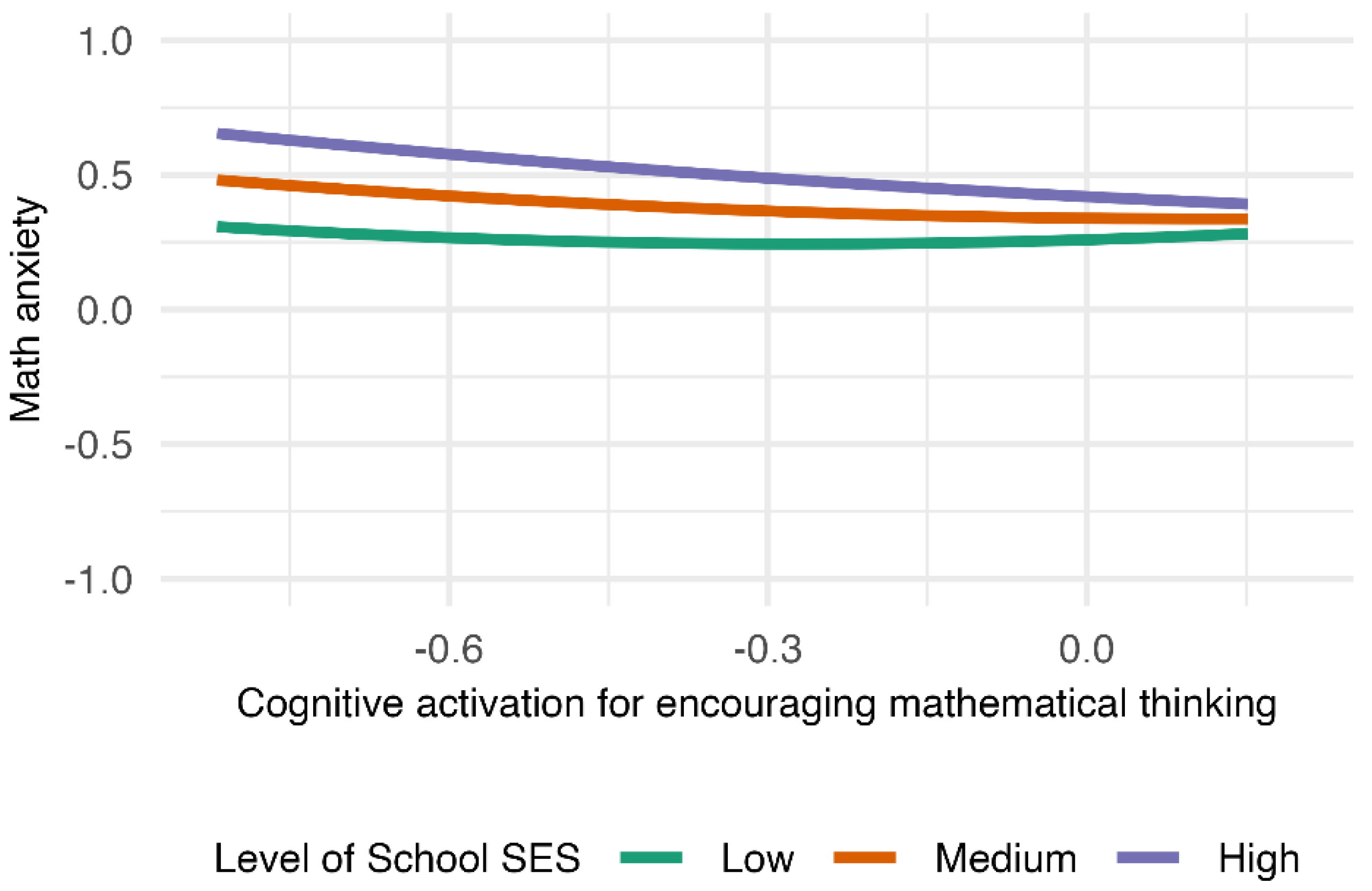

This study investigated the curvilinear effect of cognitive activation on math anxiety and the moderating effects of SES and math self-efficacy, using the Japanese dataset from PISA 2022 and multilevel regression analysis (

Table 2,

Figure 1,

Figure 2,

Figure 3,

Figure 4 and

Figure 5). The results indicated that cognitive activation for fostering reasoning exhibited a negative curvilinear relationship with math anxiety; however, the magnitude of the effect was small, and the overall pattern was essentially flat. In contrast, cognitive activation for encouraging mathematical thinking was initially associated with a reduction in math anxiety, but this effect gradually plateaued. Therefore, Hypotheses 1 and 2 were partially supported.

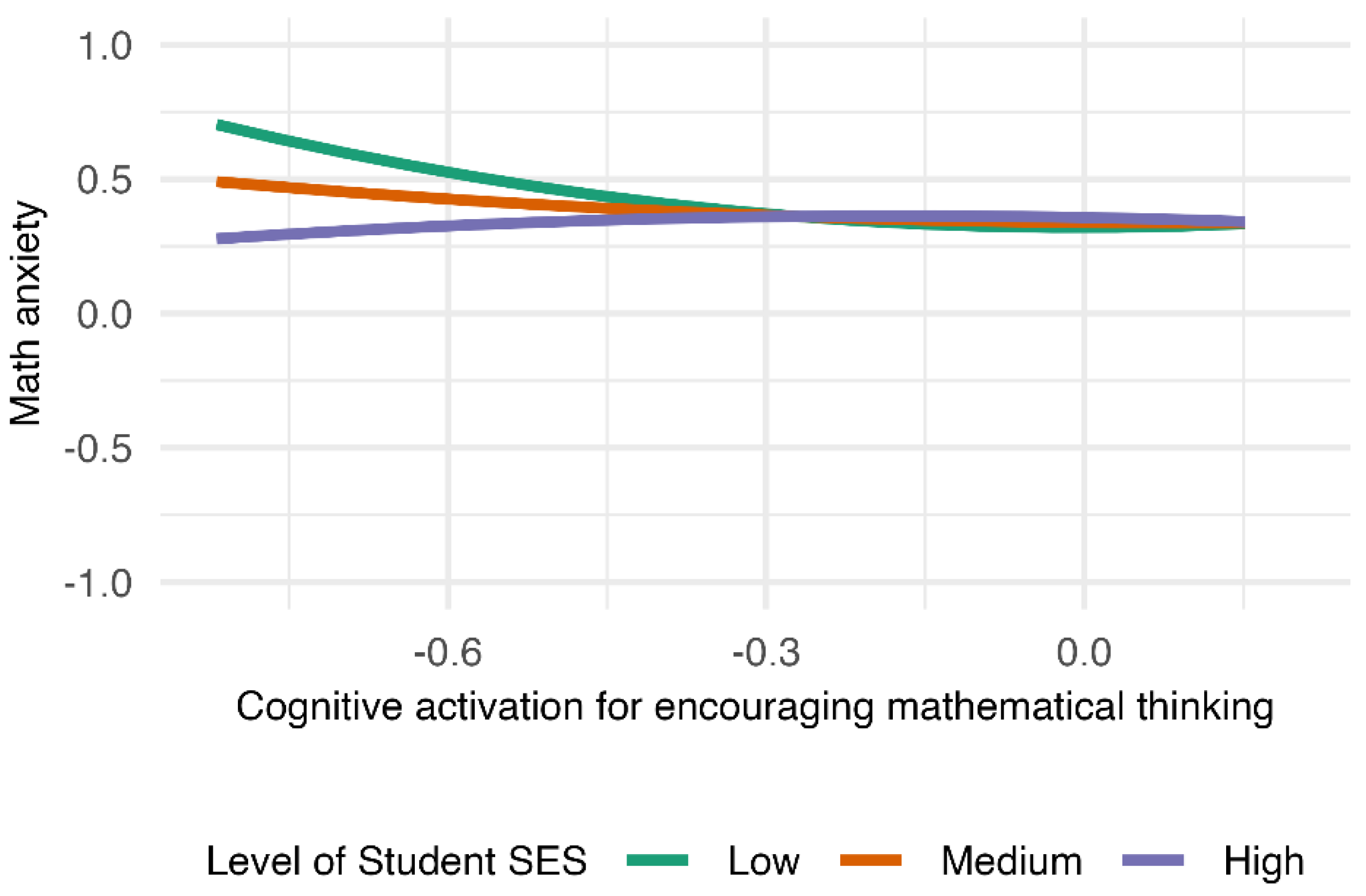

Student SES negatively moderated the relationship between cognitive activation for encouraging mathematical thinking and math anxiety. Specifically, when student SES was low, increased cognitive activation was initially associated with lower math anxiety, but the effect diminished over time. Consequently, Hypotheses 3-a and 3-b were not supported. However, this trend contributed to a narrowing of the math anxiety gap between high- and low-SES school groups.

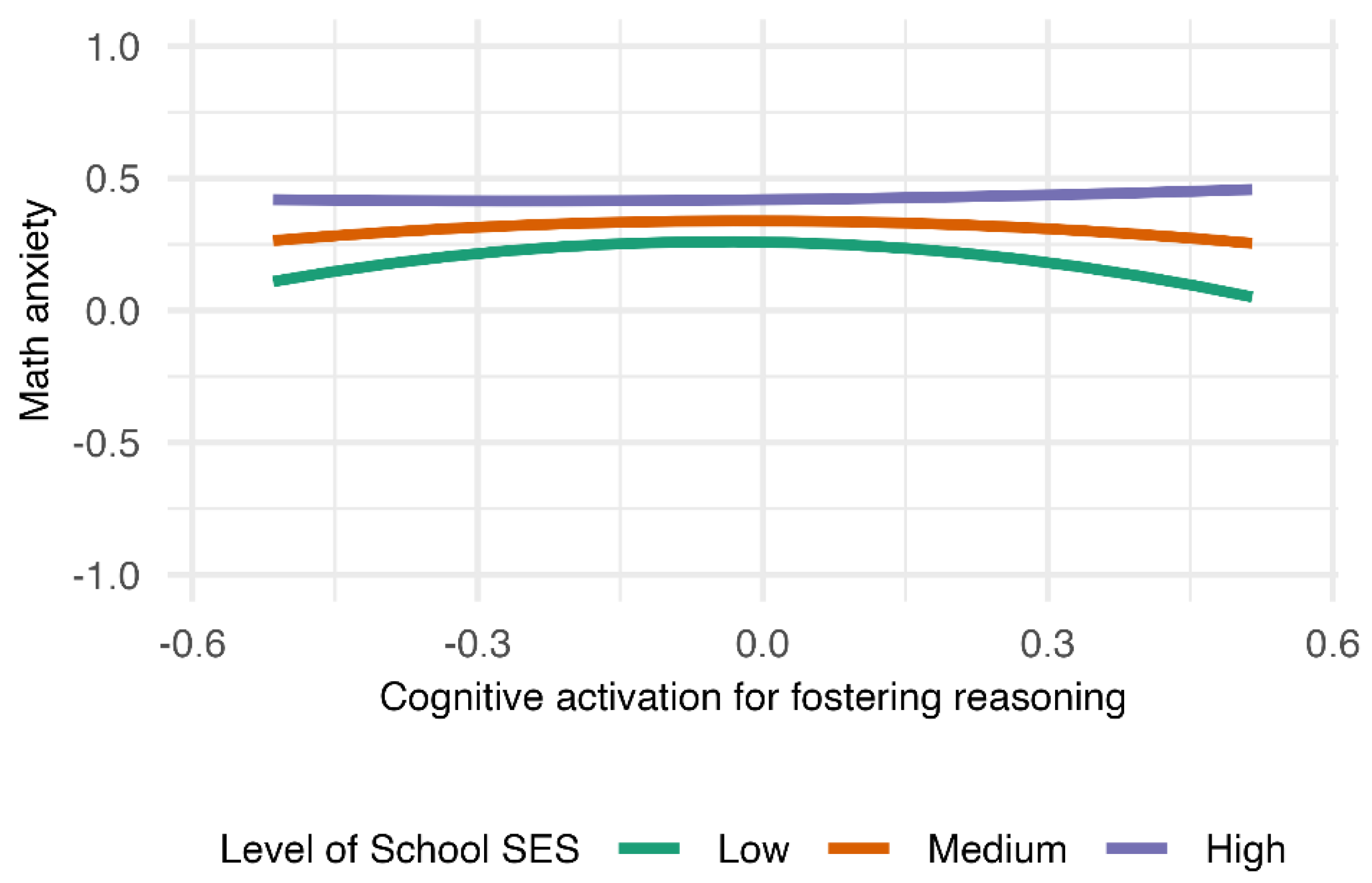

School SES moderated the relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety. When school SES was low, both low and high frequencies of cognitive activation for fostering reasoning were associated with reduced math anxiety, whereas moderate levels were associated with higher anxiety. Conversely, in high-SES schools, increased cognitive activation for encouraging mathematical thinking was linked to reduced math anxiety, and the difference between high- and low-SES groups converged. Thus, Hypothesis 4-a was partially supported, while Hypothesis 4-b was not. Math self-efficacy did not significantly moderate the relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety, and Hypothesis 5 was not supported.

The Relationship Between Cognitive Activation and Math Anxiety

The present findings extend prior research on the link between cognitively demanding instruction and students’ emotional responses in mathematics. While previous studies (e.g., Zuo et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2022) found a linear negative association between cognitive activation and math anxiety, the present study revealed a nonlinear (curvilinear) relationship.

Specifically, the results suggest that greater use of cognitive activation strategies that encourage mathematical thinking initially reduces math anxiety but eventually plateaus. This pattern is consistent with earlier studies that identified beneficial effects of cognitive activation (Zuo et al., 2024; Liu et al., 2022), while also highlighting that the benefits may not increase indefinitely.

One possible explanation is that increased mathematical-thinking–oriented activation promotes student engagement, thereby enhancing motivation and reducing anxiety. From a theoretical perspective, control-value theory (Pekrun, 2006) suggests that anxiety arises when students perceive low control over valued tasks, while cognitive load theory (Sweller, 1988) indicates that excessive task demands can overload working memory and increase stress. Together, these frameworks provide a rationale for why cognitive activation may reduce anxiety up to a point but yield diminishing returns at higher levels.

However, though statistically significant, the quadratic effect for reasoning-focused activation was practically negligible, and the curve was nearly flat. One plausible explanation is that, in the present dataset, the average level of reasoning-focused activation was relatively low, suggesting that Japanese mathematics teachers make limited use of such practices compared to international standards (see

Table 1). As a result, the restricted range of this instructional practice may have reduced its potential to explain meaningful variation in students’ anxiety. In this context, even though the large sample size allowed the detection of a statistically significant quadratic effect, its educational significance appears limited.

The Moderating Effect of SES on the Relationship Between Cognitive Activation and Math Anxiety

Contrary to the original hypothesis, the results revealed that when student SES was low, increased cognitive activation for encouraging mathematical thinking initially reduced math anxiety, though the effect faded at higher activation levels. Interestingly, this pattern contributed to closing the gap in math anxiety between high- and low-SES students. This suggests cognitive activation may be a compensatory strategy for students with fewer educational resources outside school.

Theoretically, this pattern contrasts prior findings on achievement outcomes, where cognitively demanding instruction has been shown to benefit higher-SES students more strongly (Caro et al., 2016). Our results, by focusing on math anxiety rather than achievement, indicate a different distribution of benefits: mathematical-thinking–oriented activation appears to reduce math anxiety more for low-SES students at lower–to–moderate levels, with diminishing returns beyond that range. One interpretation is that such activation may initially raise perceived control among students with fewer out-of-school supports, thereby lowering anxiety, but once task demands exceed available scaffolding, additional activation no longer yields incremental reductions.

At the school level, in high-SES schools, frequent use of cognitive activation for encouraging mathematical thinking was consistently associated with reduced math anxiety. This is consistent with prior research (Perry et al., 2022) suggesting that high-SES schools often provide supportive environments and instructional resources that facilitate effective teaching. In Japan, teachers in high-SES schools also report higher instructional efficacy and job satisfaction (Matsuoka, 2015b), which may enable them to implement cognitively demanding practices more effectively.

In low-SES schools, an intriguing pattern emerged: math anxiety was lower when cognitive activation for fostering reasoning was infrequently or frequently used, but higher when used moderately. This non-monotonic pattern may reflect variability in implementation quality under resource constraints. At moderate levels, reasoning-oriented practices might be introduced without sufficient scaffolding, increasing cognitive load and anxiety; very low use may limit exposure to challenging demands; and very high use may occur mainly in classrooms where teachers can support such practices effectively. Additionally, as shown in

Table 1, the average level of reasoning-focused activation in this sample was relatively low, suggesting range restriction that can attenuate its association with emotional outcomes. Together, these points underscore that the quality and support accompanying cognitively demanding instruction—not merely its frequency—are crucial for shaping students’ math anxiety.

The Moderating Effect of Math Self-Efficacy on the Relationship Between Cognitive Activation and Math Anxiety

Contrary to expectations, math self-efficacy did not significantly moderate the relationship between cognitive activation and math anxiety. This finding diverges from the moderating role predicted by social cognitive theory (Bandura, 1986) and the control-value theory of achievement emotions (Pekrun, 2006), which suggest that competence beliefs should buffer emotional reactions to cognitively demanding instruction.

However, the absence of a moderation effect does not necessarily contradict the control-value theory of achievement emotions. Instead, it may indicate that math self-efficacy functions primarily as a mediator rather than a moderator. According to the control-value theory of achievement emotions, students’ perceived control is a proximal determinant of achievement emotions, including anxiety. Cognitive activation may therefore reduce math anxiety indirectly by enhancing students’ perceived control (i.e., self-efficacy), which subsequently lowers their anxiety levels. This mediational pathway has been supported by previous studies (e.g., Zuo et al., 2024), showing that cognitively demanding instruction increases math self-efficacy, decreasing math anxiety.

Another possible explanation is that the measure of math self-efficacy (MATHEFF) used in this study may not fully capture the context-specific aspects of competence beliefs most relevant to classroom practices. There may be a misalignment between students’ general confidence in solving mathematical problems and their emotional responses to cognitively activating instruction, especially when such practices are inconsistently or poorly implemented. Future research should therefore test both moderation and mediation models, ideally with more context-specific measures of math self-efficacy, to clarify the precise role of competence beliefs in shaping students’ math anxiety.

Theoretical Contributions

This study makes several contributions to theory. First, by identifying a curvilinear association between mathematical-thinking activation and math anxiety, the findings extend previous research that assumed a strictly linear relationship. Integrating control-value theory (Pekrun, 2006) with cognitive load theory (Sweller, 1988), the results suggest that moderate levels of cognitive activation may enhance perceived control and reduce anxiety, whereas excessive levels may impose cognitive overload and diminish these benefits. This refinement highlights the value of considering nonlinear dynamics in research on instructional quality and students’ emotions.

Second, the moderation results regarding socioeconomic status contrast with prior findings on achievement outcomes. While Caro et al. (2016) reported that cognitively demanding instruction benefited high-SES students more strongly in terms of achievement, the present study shows that, for math anxiety, low-SES students appeared to gain more benefit at lower to moderate levels of activation. This indicates that the distribution of benefits depends on whether the outcome is cognitive (achievement) or affective (anxiety). The finding thus broadens theoretical perspectives by emphasising that instructional effects on learning and emotions may not align.

Third, the differentiation between reasoning-focused activation and mathematical-thinking activation revealed distinct associations with math anxiety. While reasoning-focused activation showed negligible emotional effects, mathematical-thinking activation exhibited a curvilinear pattern with practical significance. This underscores that not all sub-dimensions of cognitive activation are equally relevant to students’ affective experiences, suggesting that theoretical models of teaching quality (e.g., Klieme et al., 2009) may benefit from further differentiation among activation types.

Fourth, despite its strong main effect, the absence of a moderating effect of math self-efficacy suggests that self-efficacy may function primarily as a mediator rather than a moderator. This aligns with control-value theory, which posits that perceived control is a proximal determinant of achievement emotions. The findings, therefore, refine theoretical understanding of competence beliefs in the context of cognitively demanding instruction, highlighting the need for future research to test mediation models more explicitly.

Practical implications

The findings of this study offer important implications for mathematics education. First, the results suggest that prioritising mathematical-thinking activation may be more effective in reducing math anxiety than relying solely on reasoning-focused practices. This implies that practices that stimulate conceptual reflection and extended reasoning can play a central role in shaping students’ emotional outcomes, although their effectiveness appears to plateau at higher levels.

Second, the findings indicate that cognitive activation may serve as a compensatory resource for students from low-SES backgrounds. At lower to moderate levels, mathematical-thinking activation was associated with more substantial reductions in anxiety for disadvantaged students, suggesting its potential to help narrow socioeconomic disparities in emotional outcomes.

Third, results at the school level emphasise the importance of instructional quality. In low-SES schools, reasoning-focused activation was sometimes linked to higher anxiety when implemented inconsistently, underscoring the need for sufficient scaffolding and teacher capacity. This highlights that the frequency and quality of cognitively demanding practices matter for students’ emotional well-being.

Finally, Japanese mathematics teachers reported lower average use of cognitive activation compared to international peers. This finding points to the potential value of strengthening teacher training curricula to incorporate cognitive activation—particularly mathematical-thinking activation—to address Japan’s comparatively high levels of math anxiety.

Limitations

This study has several limitations that also point to promising directions for future research. First, the PISA 2022 dataset is cross-sectional, which precludes strong causal inference. Longitudinal or experimental designs would be valuable to establish the directionality of effects between cognitive activation, self-efficacy, and math anxiety.

Second, cognitive activation was analysed at the school-mean level rather than at the classroom level, due to data constraints. This aggregation may have masked within-school heterogeneity in teaching quality. Future studies could incorporate classroom-specific identifiers to better capture teacher–student interactions.

Third, the measures of cognitive activation relied on student self-reports, which may reflect perceptions rather than actual teaching practices. Future research could integrate self-reports with classroom observations and teacher reports to strengthen construct validity.

Finally, this study focused exclusively on 15-year-old students in Japan. The extent to which these findings generalise to other age groups or cultural contexts remains uncertain. Cross-national and developmental comparisons could provide valuable evidence on whether the observed plateauing effects and SES patterns are universal or culture specific.