Introduction

1.1. Background and Motivation

Concrete remains the most widely used construction material in the world, forming the backbone of modern infrastructure and playing a vital role in supporting economic development. Its versatility, durability, and relatively low cost make it the material of choice for a wide range of applications, from buildings and bridges to roads, dams, and industrial facilities. However, the production of Ordinary Portland Cement (OPC), the principal binder in concrete, is a major source of carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions, responsible for approximately 8% of global anthropogenic emissions [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5]. This high environmental burden has intensified the search for sustainable alternatives to traditional cementitious materials. Supplementary cementitious materials (SCMs), such as fly ash, ground granulated blast furnace slag (GGBFS), and silica fume, have historically been utilized to partially replace OPC, improving concrete performance while reducing its carbon footprint [

1,

6,

7,

8]. A comprehensive inventory of both conventional and emerging low-carbon raw materials has been compiled [

9]. Recently, lithium slag (LS), an industrial byproduct generated during lithium extraction from spodumene and lepidolite ores, has attracted significant attention as a promising SCM. The rapid growth of the lithium industry, particularly in Australia and China, has resulted in a substantial increase in LS generation, presenting both an environmental challenge and an opportunity for valorization in cementitious systems [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5,

10]. This aligns with the broad review on mining-waste valorization by [

11,

12]. The application of mining waste materials in potential geotechnical applications—such as soil stabilization, backfill reinforcement, and earth-structure construction—have also been investigated by [

13]. Further, the valorisation of sludges from aggregate production into construction materials—including filler, supplementary cementitious materials, and lightweight aggregates—has been comprehensively examined by [

14]. Similarly, the incorporation of stabilized waste soil from landfill mining as a partial replacement for fine aggregate in concrete—up to 30 % by volume—has been shown to improve compressive, tensile, and flexural strengths as well as durability [

15].

1.1. Scope and Significance of Lithium Slag (LS) as an SCM

Lithium slag is primarily composed of silica (SiO₂) and alumina (Al₂O₃), with varying contents of calcium oxide (CaO), lithium oxide (Li₂O), and minor phases, typically exhibiting a partially amorphous structure that imparts pozzolanic activity [

1,

2,

4,

10,

16,

17]. Similar applications of metallurgical wastes in concrete have been systematically reviewed by [

18] and gold-tailings sludge has also demonstrated cement-replacement potential [

19].

Several studies have demonstrated that incorporating LS enhances the mechanical performance of concrete, notably increasing compressive strength, tensile strength, and flexural strength [

4,

6,

7,

17,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

27,

28,

29,

30]. These improvements are attributed to enhanced hydration reactions, secondary C-S-H and C-A-S-H gel formation, and the densification of the interfacial transition zone (ITZ). Durability improvements associated with LS use have also been widely reported, including reductions in chloride ion penetration, sulfate attack, drying shrinkage, and freeze-thaw damage [

4,

6,

7,

16,

20,

21,

22,

24,

28,

30,

31,

32,

33]. The finer particle size and pozzolanic reaction contribute to a refined pore structure and improved impermeability [

34] .

Several investigations have focused on the use of LS in alkali-activated and geopolymer systems, either alone or in combination with other SCMs such as fly ash, metakaolin, and slag [

4,

5,

8,

10,

16,

22,

35]. Applications in alkali-activated and 3D-printed systems have been preliminarily assessed [

36]. These studies have shown that LS enhances the polymerization reaction, improves setting times, and increases mechanical strength and chemical stability. A broader review on 3D-printed concrete with industrial by-products is provided by [

37]. Synergistic effects of combining LS with traditional SCMs in blended systems have also been reported, contributing to enhanced workability, durability, and cost-efficiency [

4,

6,

10,

16,

35,

38,

39]. Moreover, some studies have specifically explored LS’s role in improving the performance of recycled aggregate concrete [

10,

22,

40].

Microstructural analyses have also been extensively conducted to understand LS’s role at the microscopic level. Several researchers have studied hydration product formation, pore structure refinement, ITZ densification, and crystalline/amorphous phase development in LS-modified systems [

1,

2,

16,

17,

23,

24,

30,

41]. These studies confirm that LS incorporation leads to a denser matrix, higher volumes of C-S-H and C-A-S-H gels, and a refined pore size distribution, all contributing to improved mechanical and durability performance. Microstructural analyses via SEM and XRD confirm the formation of secondary C–S–H phases, paralleling findings in other tailings-based materials [

42].

Environmental and sustainability aspects associated with LS utilization have been qualitatively discussed across many studies. Valorizing LS as a cement replacement material reduces landfill burdens, conserves natural raw materials, and potentially lowers the embodied energy of concrete production [

1,

2,

4,

5,

6,

10,

16,

35,

38,

43]. However, most studies emphasize that comprehensive quantitative assessments, such as Life Cycle Assessments (LCA), remain lacking and should be a focus of future research [

4,

38].

Despite substantial progress in demonstrating the benefits of lithium slag (LS) in concrete, its reliable, large-scale implementation remains hindered by several critical challenges. Our comprehensive review reveals pronounced source-dependent variability in LS chemistry that translates into unpredictable pozzolanic reactivity, fresh-state workability, and strength development. Moreover, our analysis of various replacement levels highlights the importance of balanced mix design: insufficient LS yields marginal gains, while excessive substitution can compromise performance. Compounding these technical hurdles are significant research gaps, including the lack of rigorous life-cycle assessments, limited evaluation of LS in specialized contexts (such as fatigue resistance or high-temperature applications), and the absence of standardized processing and quality-control protocols. By systematically correlating compositional parameters with key performance indicators and outlining evidence-based mix-design frameworks, this review establishes clear guidelines to condition, characterize, and deploy LS in sustainable concrete systems—paving the way for its confident, industry-scale adoption.

2. Analysis of the Literature Review

2.1. Research Trends and Publication Growth

A significant challenge arises from the fact that all the reviewed studies are based on LS obtained from various industrial sources, with each originating from different mines located in different parts of the world. As a result, the chemical composition of LS is not unique or consistent, leading to variability in its behaviour when used in concrete. This inconsistency in chemical composition means that LS obtained from one region may behave differently from LS sourced from another, making it difficult to generalize research findings across all LS-based concrete applications. Consequently, the results of these studies may not reliably translate to industrial use of LS-based concrete made from local lithium mines. The variability in LS composition can pose challenges for industry professionals, as they may struggle to predict how locally sourced LS will interact with concrete, leading to uncertainty in performance outcomes. Therefore, while LS holds potential, careful consideration of its source and composition is necessary for practical applications, and additional localized testing may be required to ensure reliable performance.

Another critical aspect that has received limited attention in the literature is the applicability of LS-based concrete in specialized concrete applications, such as its uses in the pavement industry. However, the effect of LS on the specific mechanical and durability properties such as fatigue resistance, freeze-thaw resistance and thermal expansion coefficient required for rigid pavement concrete has not been extensively studied.

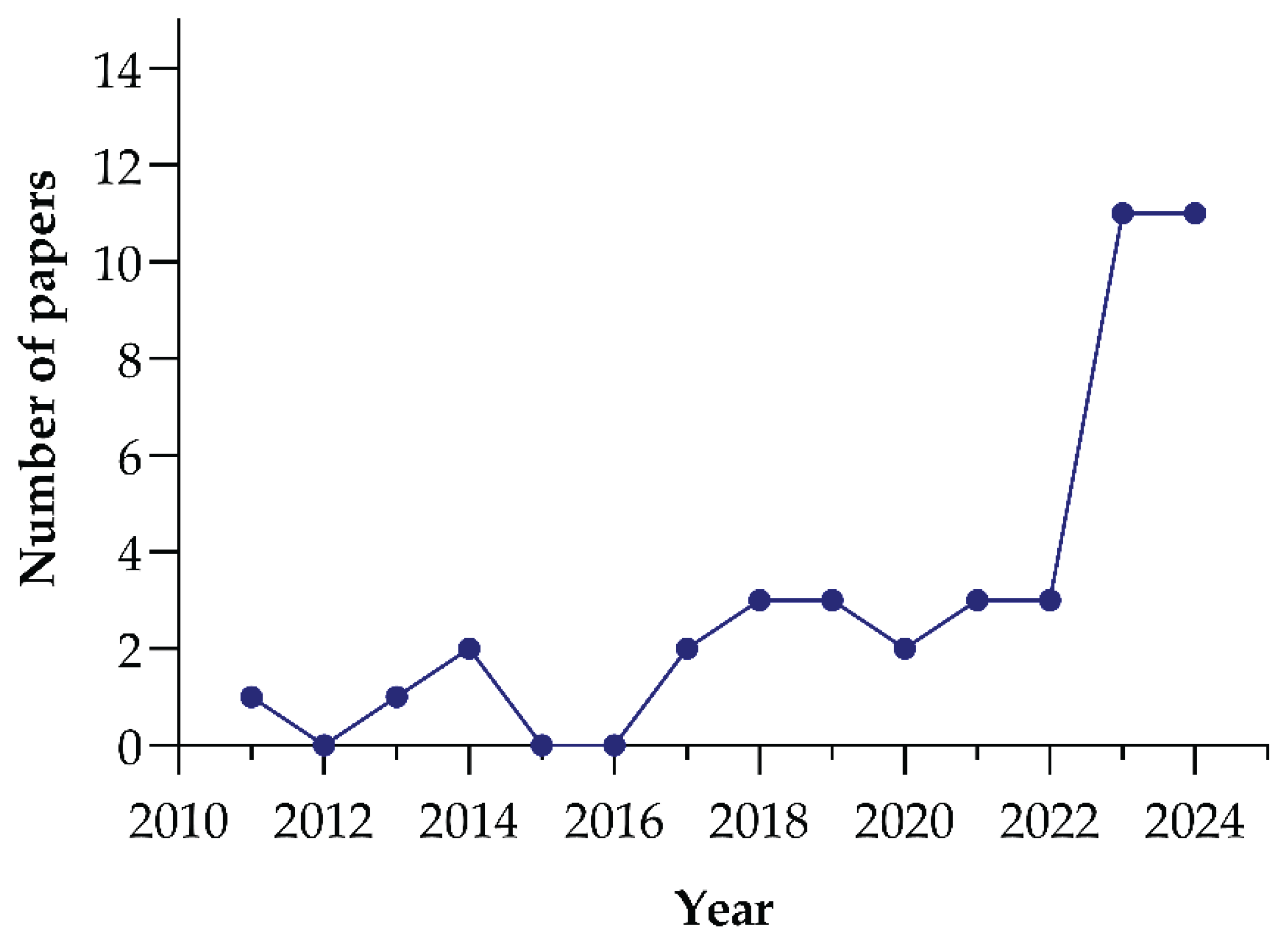

According to

Figure 1, starting from 2011, where only one study was published, the research gradually gained momentum, with slight increases in 2014 and 2017. For instance, in 2011, there was only one study, and in the following years, we notice some gaps, such as in 2012, 2015, and 2016, where the authors could not find any published studies specifically related to LS in concrete application. However, this does not necessarily mean there were no studies at all; as far as authors know, no significant research focusing on lithium slag in concrete applications was conducted or published during those years. However, from 2018 onwards, there has been a steady rise in the number of publications, reflecting the growing interest and potential in using lithium slag as a supplementary cementitious material.

In particular, the years 2023 and 2024 show a remarkable surge, with 11 and 10 studies, respectively. This sharp increase demonstrates that lithium slag is gaining recognition as an important area of investigation in sustainable construction and material innovation. This trend aligns with the increasing focus on environmental sustainability and the search for eco-friendly alternatives in the construction industry.

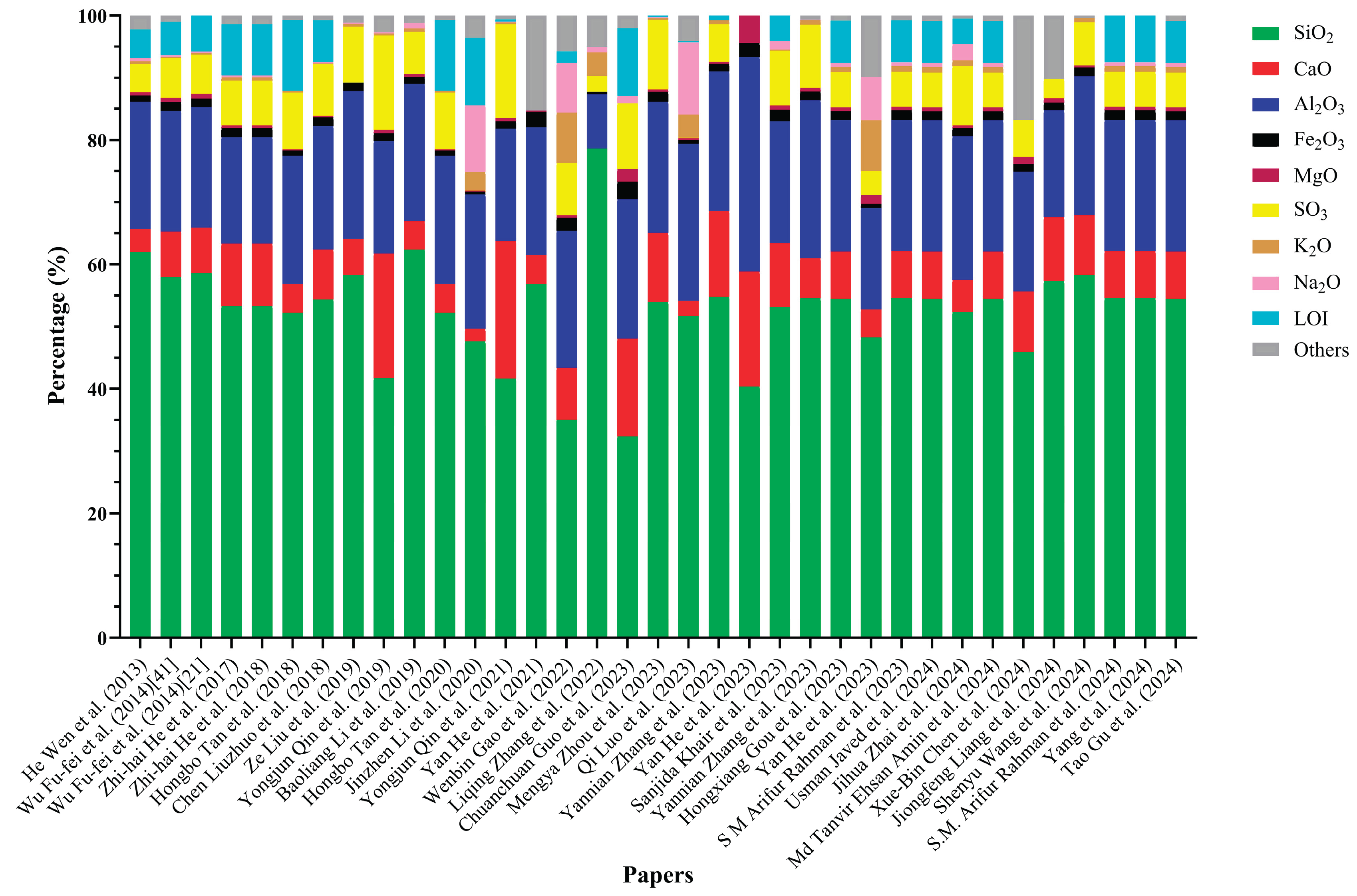

2.2. Chemical Composition of Lithium Slag in Previous Studies

As evidenced in the Error! Reference source not found., the chemical composition of lithium slag exhibits significant variability across different studies. This variation in key components, such as SiO₂, CaO, and Al₂O₃, underscores the inconsistencies inherent in lithium slag derived from diverse sources or production processes. For instance, SiO₂ concentrations range from as low as 32% to as high as 78%, while CaO content fluctuates between 2% and 22%. The impact of variations in the chemical composition of LS on concrete properties remains unclear due to the absence of a systematic investigation.

These discrepancies pose a challenge when evaluating lithium slag as a sustainable material for incorporation into concrete mixes. The variation in chemical composition has direct implications for the mechanical properties and durability of the resultant concrete, necessitating further investigation into the material’s consistency and performance in concrete applications.

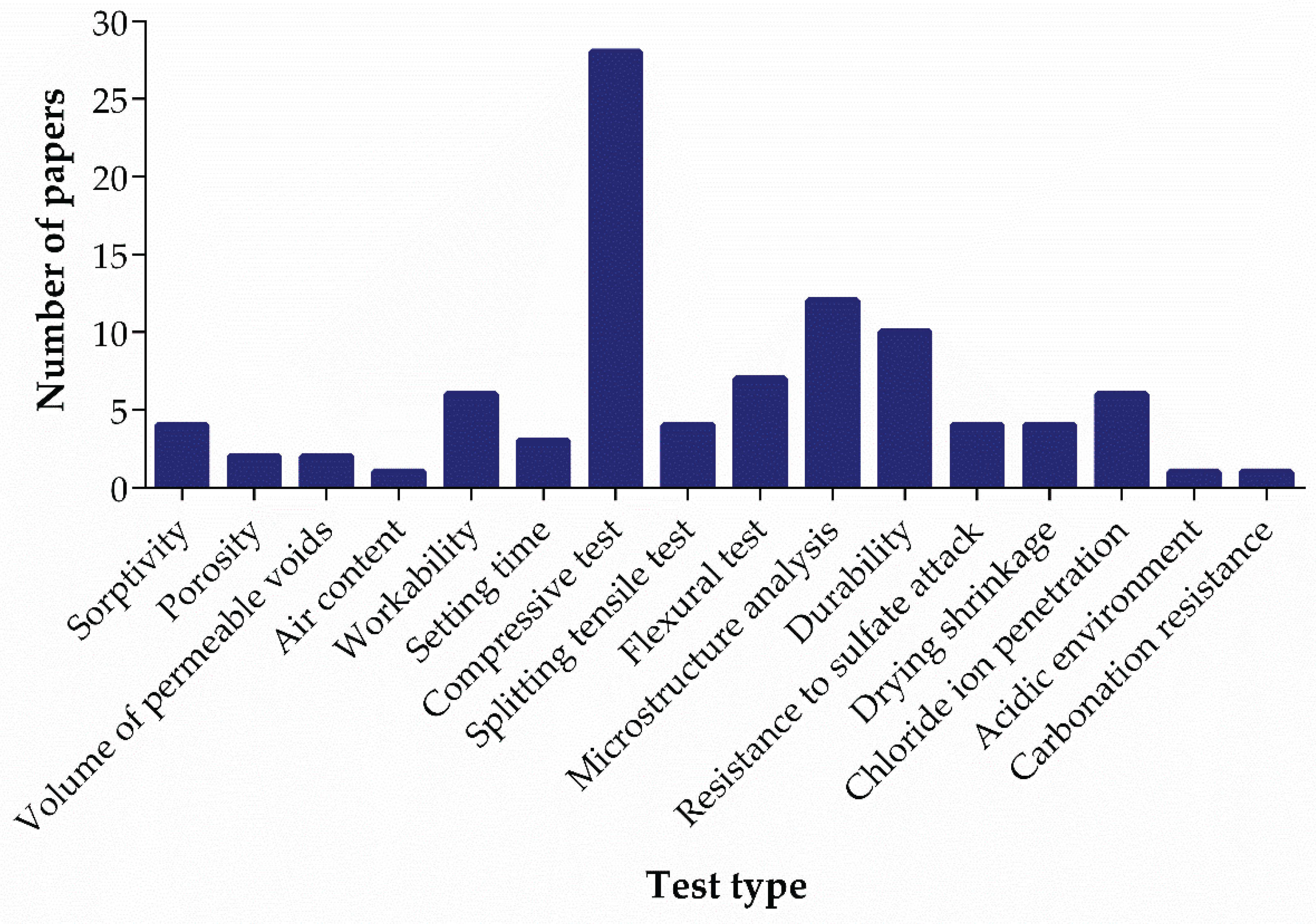

Error! Reference source not found. represents key data from various studies on lithium slag (LS) concrete, highlighting critical tests conducted by other researchers. The data includes results from four sorptivity tests, which measure the water absorption capacity of LS concrete, as well as two porosity tests and two tests on the volume of permeable voids, providing insight into the movement of fluids within the concrete. Air content was assessed in one test, while six tests examined workability, and three tests focused on the setting time of the concrete.

Regarding the mechanical properties, 28 compressive strength tests were conducted, alongside four splitting tensile tests and seven flexural tests. Furthermore, 12 microstructural tests provided valuable information on the internal structure of the concrete. Durability was evaluated through 10 tests, with four tests specifically addressing sulfate attack resistance. Additionally, four drying shrinkage tests and six tests on chloride ion penetration were analyzed. Finally, one test each was conducted to assess performance in acidic environments and carbonation resistance.

Figure 2.

Chemical composition of the lithium slag based on various papers [

2,

6,

8,

10,

16,

17,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

28,

29,

31,

35,

38,

41,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62] .

Figure 2.

Chemical composition of the lithium slag based on various papers [

2,

6,

8,

10,

16,

17,

20,

21,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

28,

29,

31,

35,

38,

41,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62] .

Figure 3.

Number of conducted tests on the LS-concrete.

Figure 3.

Number of conducted tests on the LS-concrete.

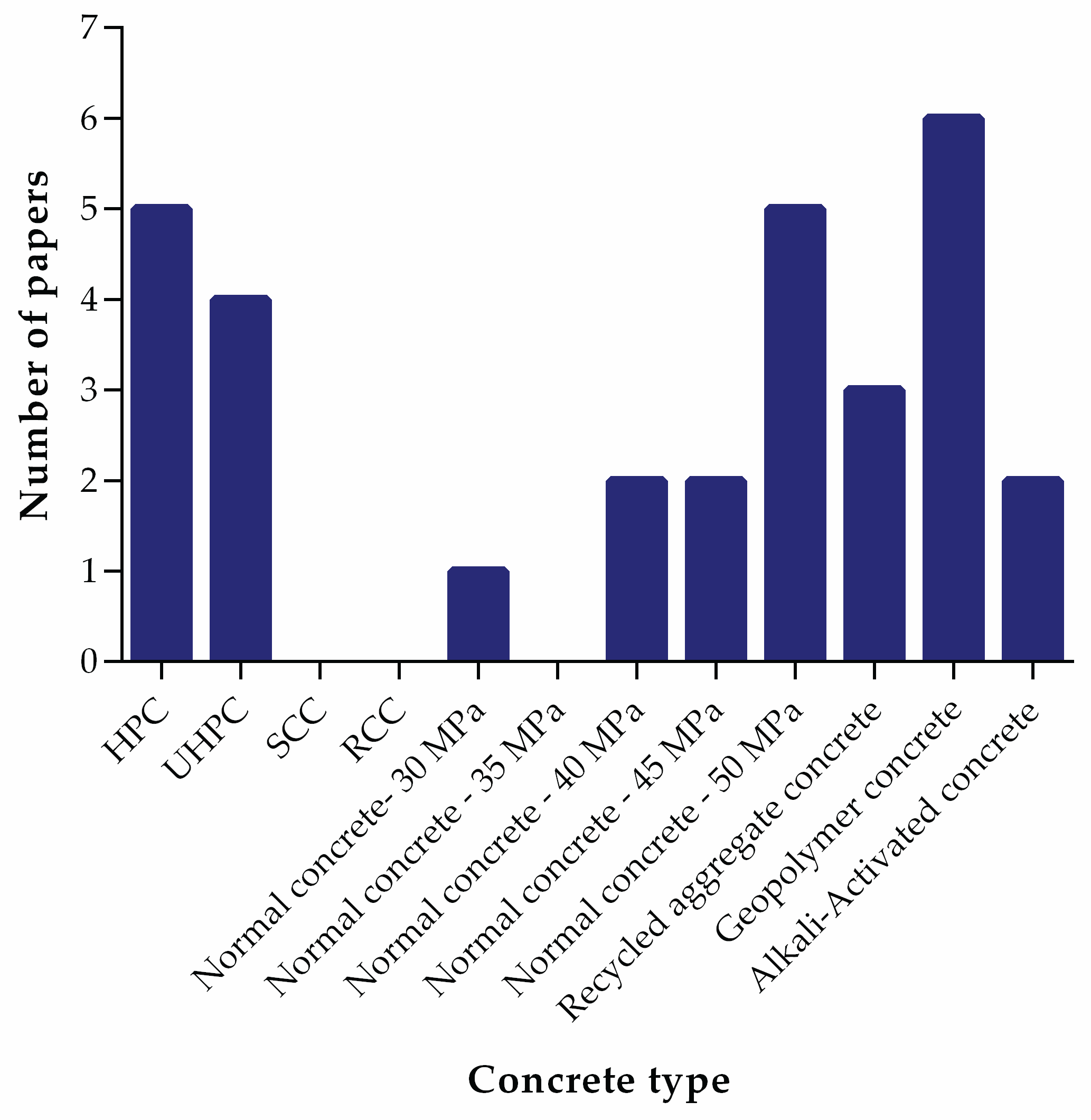

2.3. Experimental Investigations on LS-Concrete in Previous Studies

Error! Reference source not found. clearly demonstrates that most investigations to date have centered on conventional (normal) concrete, reflecting both the ubiquity of this material in construction practice and the availability of standardized testing methods (e.g., ASTM and EN protocols) that facilitate direct comparison of workability, strength development, and durability improvements imparted by lithium slag. By establishing a robust baseline in normal concrete, researchers have been able to quantify key performance metrics—such as compressive strength gain, pore structure refinement, and resistance to chloride ingress—under well-controlled conditions, thus laying the groundwork for broader application of LS as a supplementary cementitious material.

Following normal concrete, the next most extensively studied systems are Ultra-High-Performance Concrete (UHPC) and geopolymer concrete. In UHPC formulations, the incorporation of LS’s fine particles and reactive silica–alumina phases have been shown to contribute to the material’s hallmark ultra-dense microstructure, leading to exceptional mechanical properties and early-age strength gains [

2]. Geopolymer concrete research, on the other hand, leverages LS’s aluminosilicate-rich composition to participate in alkali-activation processes, offering a low-carbon alternative to both Portland cement and conventional SCMs like fly ash and slag [

35]. These studies have elucidated how LS affects setting times, polymerization kinetics, and long-term chemical stability in alkali-activated binders, thus expanding the potential palette of low-carbon binders available to the construction industry.

Figure 4.

Number of studies on different concrete types (from 2011-2024).

Figure 4.

Number of studies on different concrete types (from 2011-2024).

By contrast, applications of LS in more specialized formats, namely Roller Compacted Concrete (RCC) and Self Compacting Concrete (SCC)remain under explored, as evidenced by the relatively small number of studies in these categories. Given RCC’s growing prominence in pavement construction and the critical role of compaction characteristics and fatigue resistance under cyclic loading, systematic evaluation of LS’s influence on mixture cohesiveness, stiffness development, and long-term performance under traffic loading represents a promising research direction. Similarly, SCC’s reliance on precise rheological control to achieve high flowability without segregation underscores the need to investigate how varying LS content alters viscosity, yield stress, and stability in self-leveling applications. Beyond these areas, emerging niches such as 3D-printed concrete and fiber-reinforced systems have also received scant attention; extending LS research into these domains could uncover new opportunities for tailoring printability, build-up robustness, and interfacial bonding in advanced construction technologies.

Figure 5.

Variation in LS level used by other researchers with the type of concrete they studied [

1,

2,

6,

7,

8,

10,

16,

17,

20,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

28,

29,

31,

35,

38,

41,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62].

Figure 5.

Variation in LS level used by other researchers with the type of concrete they studied [

1,

2,

6,

7,

8,

10,

16,

17,

20,

22,

23,

24,

25,

26,

28,

29,

31,

35,

38,

41,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57,

58,

59,

60,

61,

62].

3. Reviewing the Outcomes and Findings

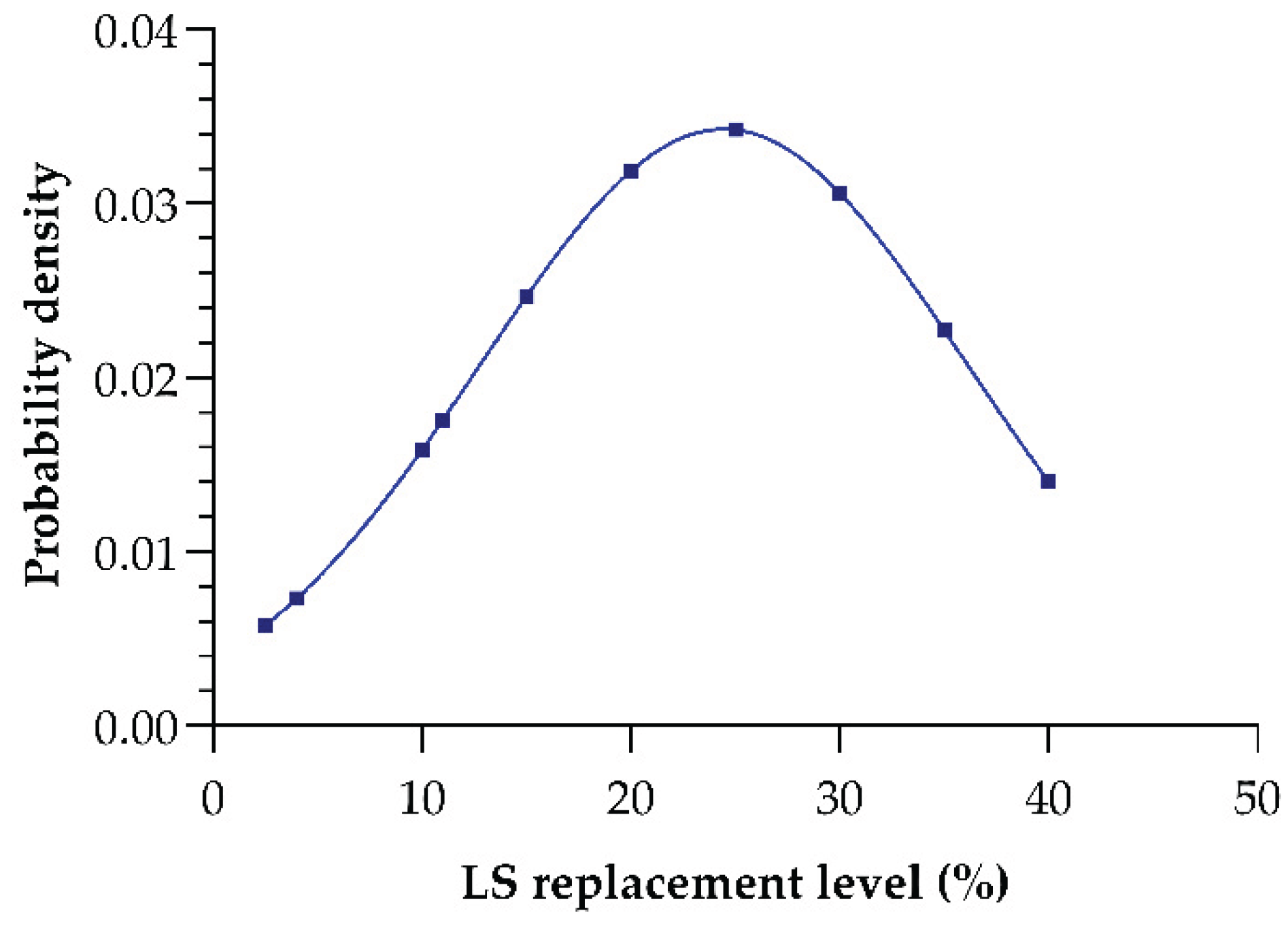

3.1. LS Replacement Levels in Various Concrete Types

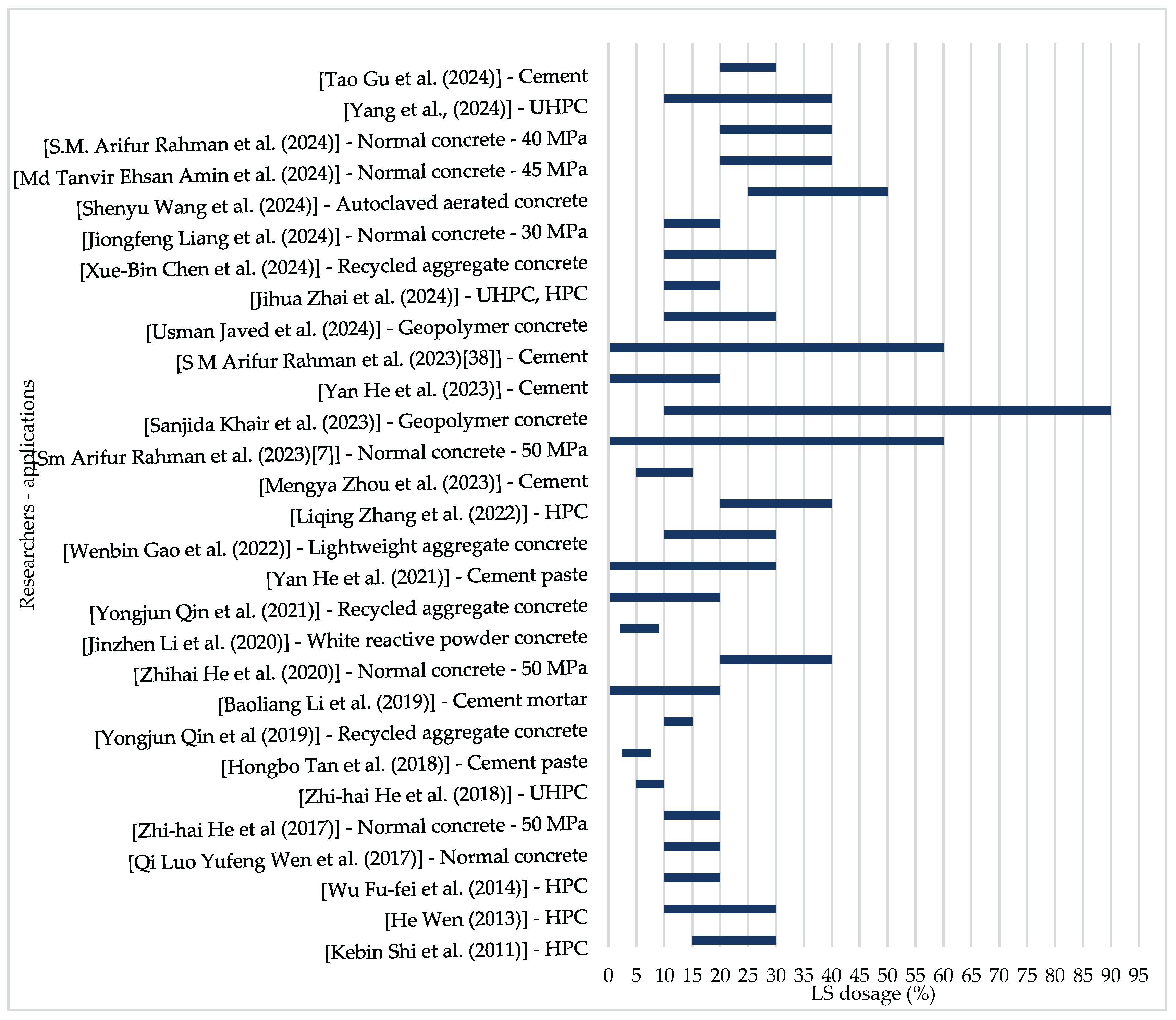

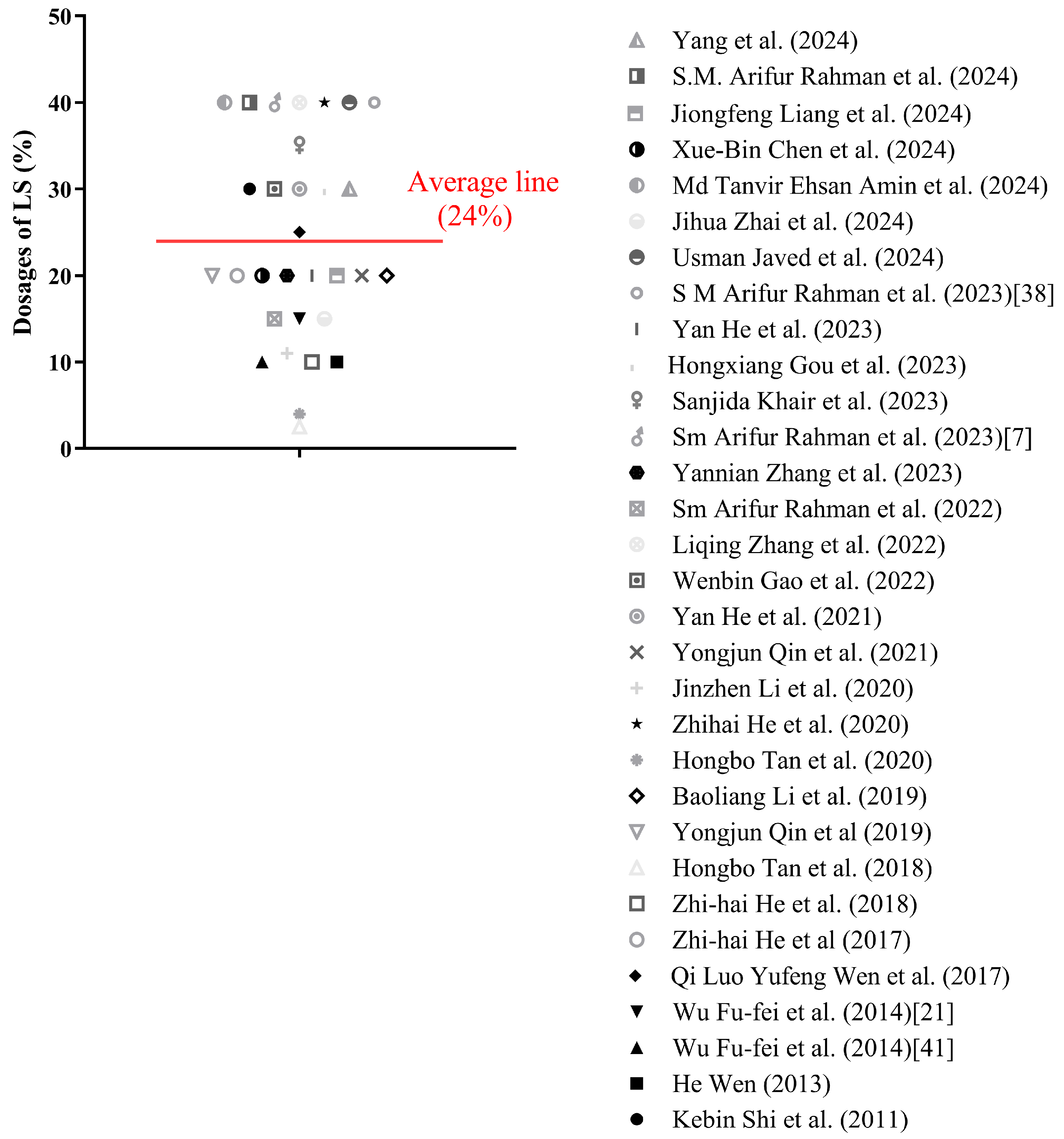

Figure illustrates the variation in lithium slag (LS) dosage levels adopted by different researchers, highlighting a broad range from minimal replacements to values exceeding 90%. This variation underscores the diverse experimental approaches used to evaluate LS as a supplementary cementitious material, reflecting differences in research objectives, material properties, and performance criteria. Understanding these variations is crucial for selecting an optimal LS dosage in this study, ensuring a balance between mechanical performance, durability, and sustainability. The findings from this review will help establish a practical LS replacement range for concrete and rigid pavement applications.

As shown in

Error! Reference source not found., the reported LS dosages vary significantly, with an average value of 24%. This suggests that while higher dosages have been explored, a balanced approach should consider performance optimization in terms of mechanical properties, durability, and sustainability. The findings from this review will guide the selection of appropriate LS replacement levels in this research, ensuring a practical and efficient utilization of LS in cementitious materials.

Figure 6.

Optimum dosage of LS reported by various papers [

1,

2,

6,

7,

10,

17,

20,

21,

23,

24,

25,

28,

29,

31,

35,

38,

41,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57] .

Figure 6.

Optimum dosage of LS reported by various papers [

1,

2,

6,

7,

10,

17,

20,

21,

23,

24,

25,

28,

29,

31,

35,

38,

41,

44,

45,

46,

47,

48,

49,

50,

51,

52,

53,

54,

55,

56,

57] .

Error! Reference source not found. presents the normal distribution of lithium slag (LS) replacement percentage, illustrating the probability density of different dosage levels in the studied mix designs. The distribution exhibits a peak of around 25-30% LS replacement, suggesting that this range is the most frequently used or optimal level within the dataset. The average LS replacement percentage is 24%, with a standard deviation of 11%, indicating a moderate spread of data around the mean. According to the properties of a normal distribution, approximately 68% of the data falls within one standard deviation of the mean (13% to 35% LS replacement) and approximately 95% of the data falls within two standard deviations of the mean (2% to 46% LS replacement). The probability density is lower at both lower and higher replacement levels, suggesting that extreme values (below 10% and above 35%) are less common or less effective in the context of the study. The smooth curve reflects the overall trend, highlighting the central tendency and variability of LS dosage percentages used in the research.

Figure 7.

Normal distribution of LS replacement percentage.

Figure 7.

Normal distribution of LS replacement percentage.

3.2. Fresh Properties of LS-Based Concrete

The study conducted by [

23] provides a detailed evaluation of the fresh properties of concretes incorporating lithium slag (LS) as a partial cement replacement at 20%, 40%, and 60% levels. The key parameters assessed included air content, compaction factor, water penetration capacity (water retention capacity), fresh density, and setting time, which are essential indicators of workability, placement performance, and early-age hydration behavior. Air Content: The air content of the mixes decreased with increasing LS content. At 20% LS replacement, a slight reduction in air content (by ~0.4%) was observed due to the presence of cenospheres. However, at higher LS dosages (40–60%), the use of superplasticizers (SPs) to maintain slump led to a minor increase in air content. Overall, all mixes remained within the design range of 2 ± 0.5%, confirming that LS can be incorporated without compromising entrained air specifications.

The compaction factor improved with LS inclusion, particularly at higher replacement levels. For example, 40% and 60% LS mixes showed an increase in compaction factors by 2.5% and 3.2%, respectively, compared to the control. This improvement was attributed to the leaner mix design and the use of SPs, which reduced internal friction during flow and placement. In contrast, fly ash mixes showed declining compactibility beyond 20% replacement, indicating LS’s superior compatibility in high-volume SCM systems.

Water Penetration Capacity (measured as Water Retention Capacity - WRC) initially increased at 20% LS due to the water-absorbing cenospheres in LS. However, at higher replacements (40–60%), WRC declined, indicating reduced water-holding ability, likely due to increased flaky and irregular LS particles that introduced internal pores and reduced particle packing. This effect, while reducing surface water retention, did not negatively impact workability thanks to optimized SP dosage.

The fresh density of the concrete decreased proportionally with LS content. Compared to the control mix (~2436 kg/m³), mixes with 20–60% LS showed density reductions of 1.2–3.3%, due to the lower specific gravity of LS (2.46) compared to Portland cement (3.10). Nonetheless, all mixes remained within the typical fresh concrete density range (2200–2600 kg/m³), confirming LS’s suitability for producing standard-density concrete.

Although setting time was not directly measured for LS-concrete in the same scope as other fresh properties, the paper notes that LS has a moderate pH (11.28) and high electrical conductivity, which implies early ion dissolution and faster initial hydration reactions compared to fly ash. These physicochemical properties suggest that LS may slightly accelerate early setting, especially when combined with superplasticizers and controlled mix temperatures.

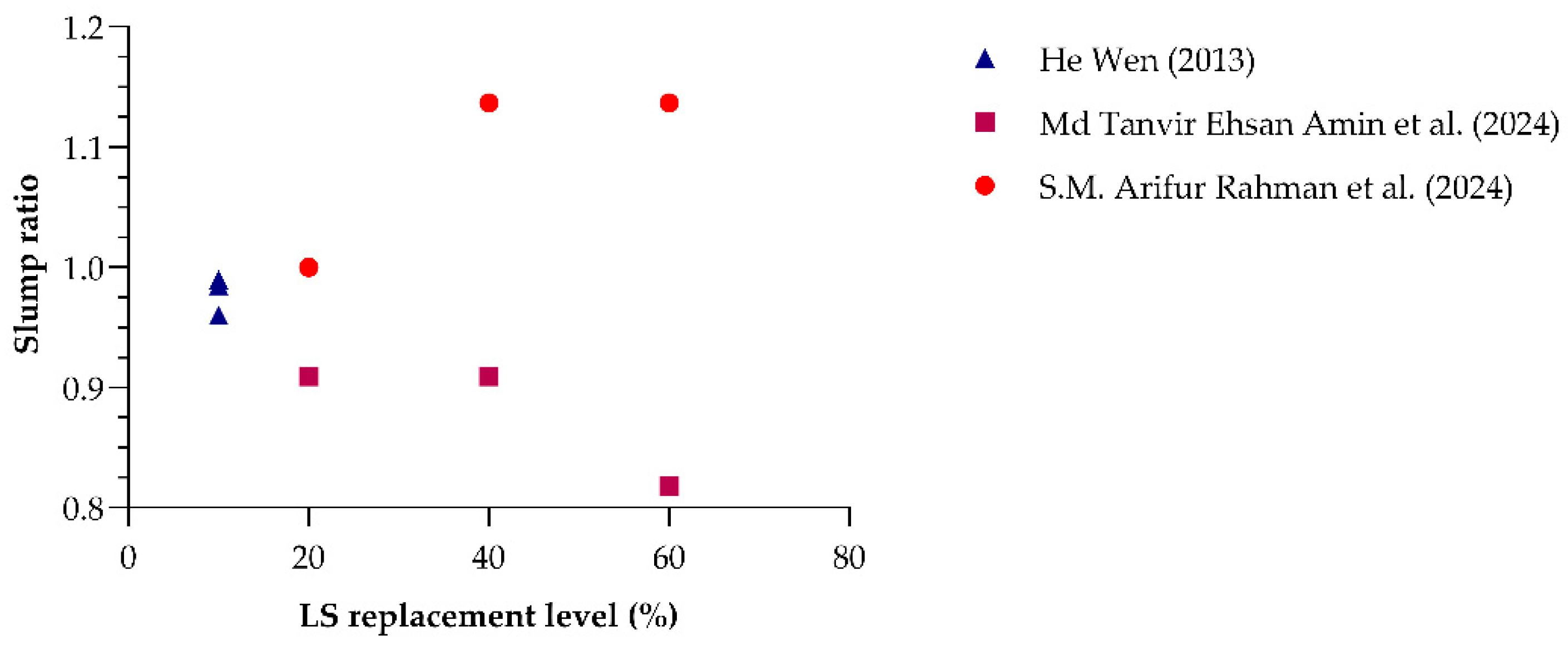

Figure 8 compares the slump ratio (defined as the ratio of the slump of LS concrete to that of control concrete) at varying LS replacement levels across three independent studies: [

20,

24], and [

23]. The trends reveal notable differences among the studies, demonstrating that the effect of LS on fresh concrete workability is highly dependent on the mixed design, particularly the use of chemical admixtures and the physical nature of LS.

A study by [

20] reported relatively stable slump ratios (about 0.97–0.99) at low LS contents (5–10%), indicating negligible impact on workability at these levels without significant mix adjustments. In the study [

24], a progressive decline in slump ratio was observed with an increase in LS dosage, reaching 0.81 at 60% LS. This clearly shows that higher LS content led to reduced workability, likely due to LS’s finer particles and irregular shapes increasing water demand. Importantly, the researchers noted that the amount of superplasticizer had to be increased in proportion to LS content, confirming that LS itself had a slump-reducing effect. A similar trend was reported by [

23], where the slump ratio increased with LS dosage (up to 1.14 at 60%). However, this apparent improvement in workability was achieved through a corresponding increase in superplasticizer dosage, alongside the use of LS with cenosphere characteristics (hollow, spherical particles), which can naturally improve flow. Despite the increase in slump, the underlying data suggest that without the elevated SP dosage, workability would have declined, aligning with the physical behavior of high-volume LS inclusion.

Taken together, these studies suggest that while LS incorporation often reduces slump, this effect can be mitigated or even reversed through careful adjustment of admixture dosage and mix design parameters. However, the consistent need for increased superplasticizer confirms LS’s inherent tendency to lower workability due to its high surface area, angularity, and water absorption capacity.

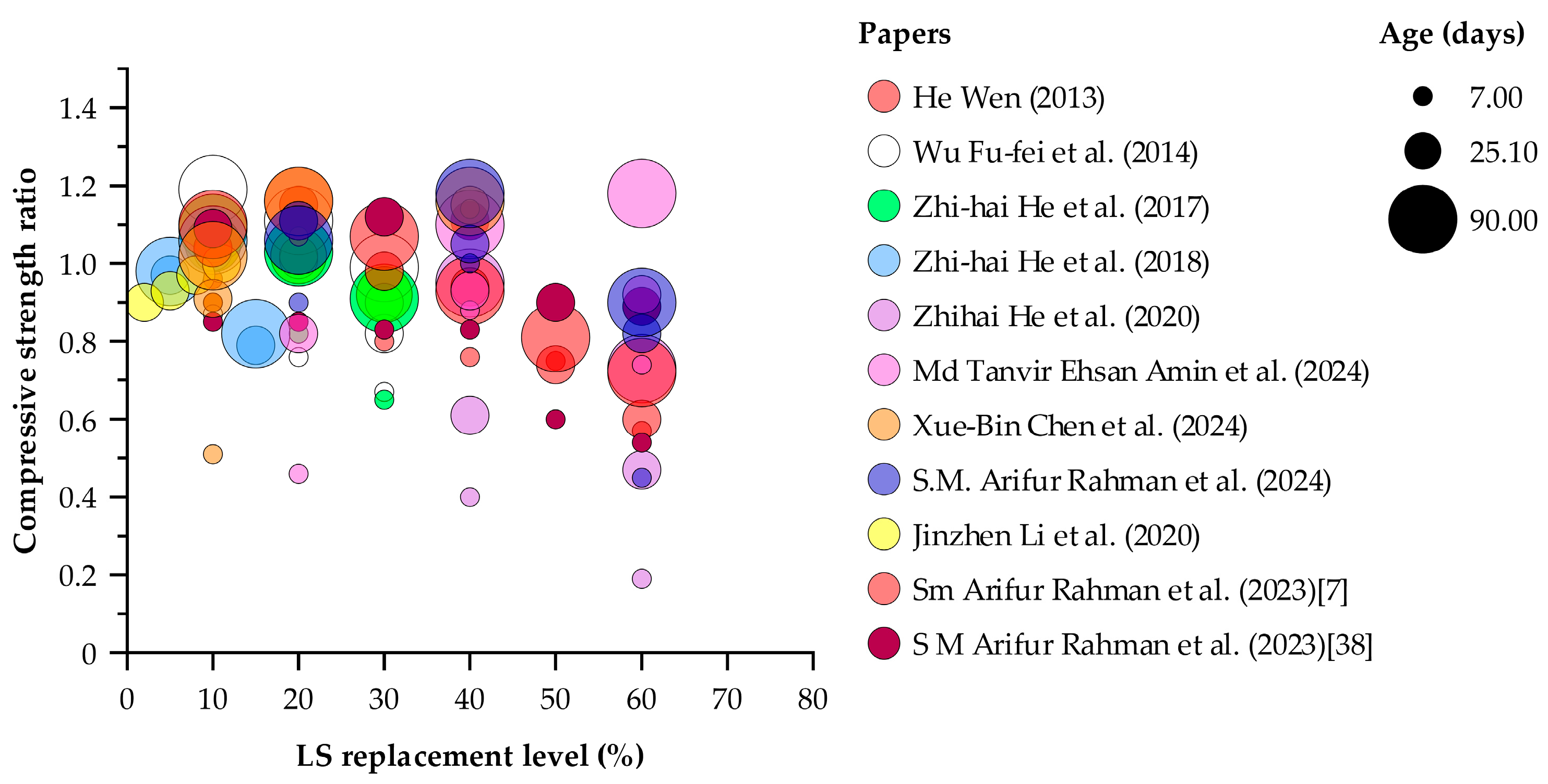

3.3. Effect of LS Replacement Level and Curing Age on Compressive Strength Ratio

Figure 9 plots the compressive strength ratio (measured compressive strength divided by control strength) against LS replacement level for curing ages of 7, 28, 60, and 90 days. At seven days the compressive strength ratio spans from 0.19 to 1.14, showing that early-age LS substitution can both markedly weaken and modestly strengthen concrete. By twenty-eight days, ratios range from 0.47 to 1.15, with most tests achieving a value of at least 1.00, indicating that four weeks of curing generally restores or enhances compressive performance. At sixty days the minimum observed ratio is 1.02 and the maximum is 1.18, demonstrating that ongoing pozzolanic reactions lead to consistent strength beyond the control mix. After ninety days ratios lie between 0.73 and 1.19, with the bulk value falling from 0.90 to 1.10; this confirms that moderate LS replacement can match or exceed reference strength over time, whereas substitution levels above forty percent remain below unity even after extended curing. These results identify forty percent as a practical upper limit for LS dosage under the tested conditions.

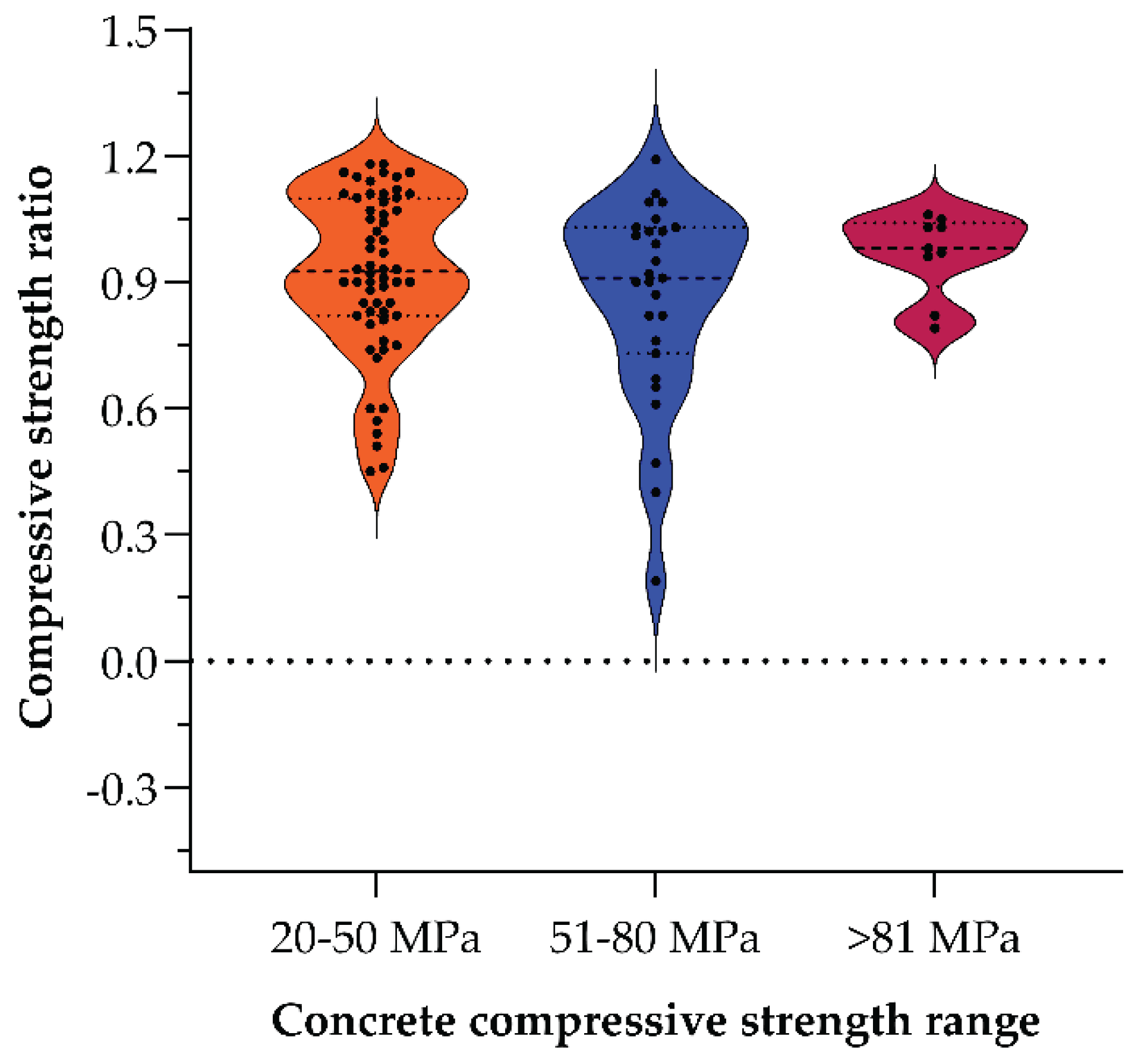

3.4. Effect of Concrete Strength Class on the Performance of Lithium Slag (LS) Blends

Figure 10 presents violin-and-dot plots of the compressive strength ratio—measured strength divided by reference strength—for three concrete classes: 20–50 MPa (orange), 51–80 MPa (blue) and > 81 MPa (purple). The width of each violin reflects the relative frequency of observations, points show individual tests, and dashed lines mark the median and interquartile range. In the 20–50 MPa group, ratios cluster tightly around a median of almost 0.93 (most between 0.6 and 1.2), indicating acceptable consistent behavior under the tested condition. The 51–80 MPa mixes display the greatest spread—from near 0.2 up to approximately 1.25, with a median just above one—suggesting mid-range strengths are most sensitive to the exposure. The > 81 MPa category appears narrowest (roughly 0.8–1.1) with a median close to unity, implying high-strength concretes retain capacity most uniformly; however, this group is based on substantially fewer data points than the others. The limited sample size for the > 81 MPa mixes may understate true variability and reduce confidence in the observed distribution, so these results should be interpreted with caution. Future work should expand the number of high-strength specimens to verify that their apparent stability is representative and not an artefact of low sample count.

3.5. Effect of LS Replacement Level and Curing Age on Tensile Strength Ratio

Figure 11 shows tensile strength ratio as a function of LS replacement level (10, 20, 30, 40 and 60 %) after curing for 7, 28 and 90 days. At 28 days, mixes with 10 % LS exhibit the highest ratio (1.24), followed by 20 % (1.20) and 30 % (1.09), indicating that modest substitutions not only restore but can exceed the control tensile capacity by four weeks. For the 20 % replacement series, the ratio increases from 0.90 at 7 days to exactly 1.00 at 28 days and then to 1.25 at 90 days, demonstrating a sustained gain due to ongoing pozzolanic reactions. A similar trend is observed at 40 % LS: the ratio rises from 0.89 at 7 days to 1.10 at 28 days and reaches 1.23 at 90 days, confirming that moderate dosages benefit progressively from prolonged curing.

In contrast, the 60 % replacement mix starts with a low early-age ratio of 0.74, recovers to 0.96 by 28 days, but then slightly declines to 0.95 at 90 days. This behavior highlights a dilution effect at high LS contents, where the initial loss in tensile capacity cannot be fully compensated even after extended hydration. Taken together, these data identify a practical upper limit of approximately 40 % LS for achieving both early and long-term tensile performance; beyond this threshold, further substitution yields diminishing returns despite prolonged curing.

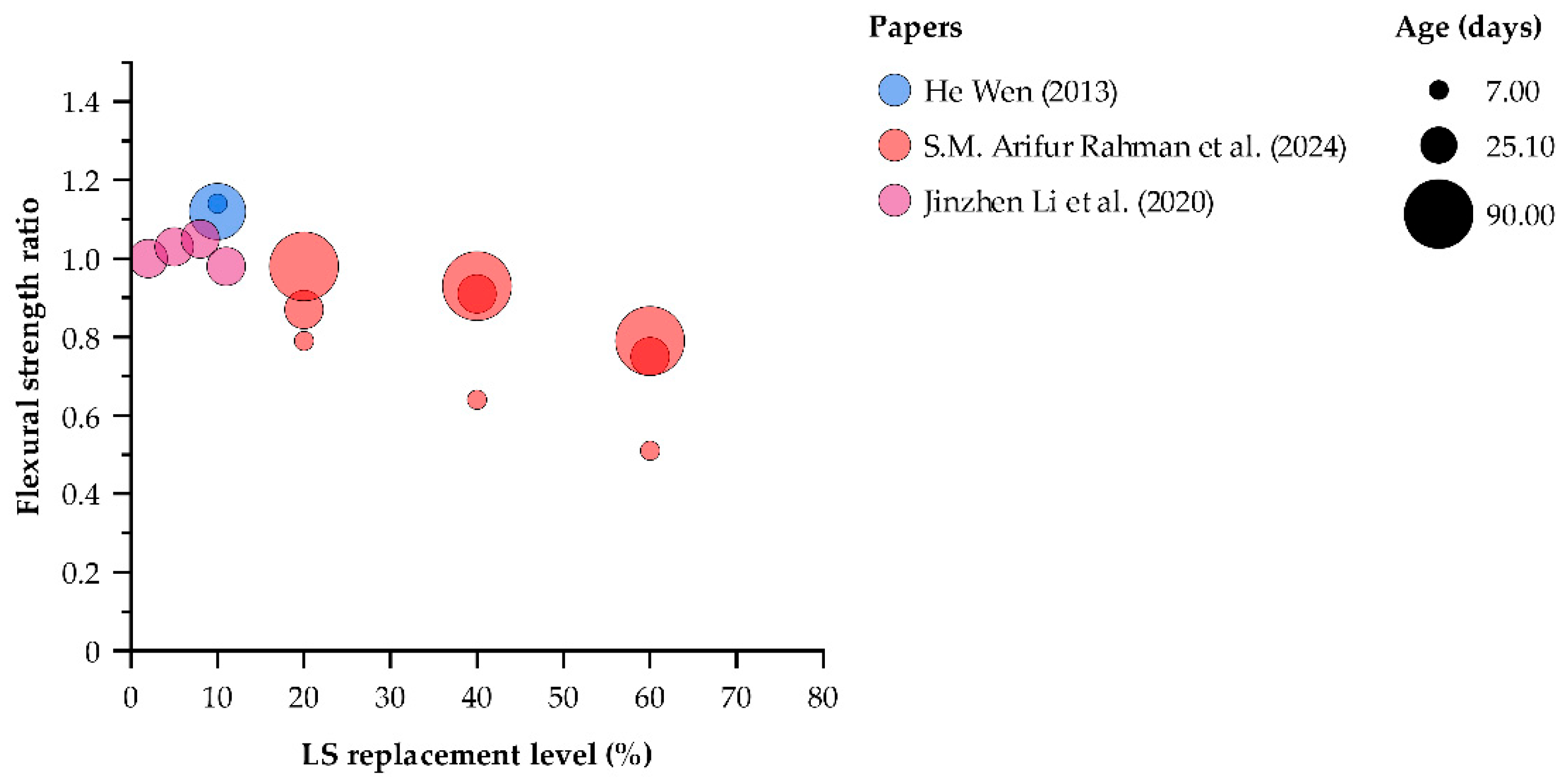

3.6. Effect of LS Replacement Level and Curing Age on Flexural Strength Ratio

Figure 12 shows that at very low LS contents (2–11 %), the 28-day flexural strength ratios remain essentially unchanged or slightly improved (0.98–1.05), indicating that minor LS substitutions do not compromise flexural capacity. At 10 % replacement, early-age performance is excellent, with a 7-day ratio of 1.14 and a 60-day ratio of 1.12, confirming both early and sustained enhancements. When LS content increases to 20 %, the ratio rises steadily from 0.79 at 7 days to 0.87 at 28 days and ultimately approaches unity (0.98) at 90 days, reflecting progressive pozzolanic development. A 40 % substitution follows a similar trajectory—0.64 at 7 days, 0.91 at 28 days and 0.93 at 90 days—demonstrating that moderate dosages can recover most of the lost strength by three months. In contrast, the 60 % mix suffers a severe dilution effect (0.51 at 7 days), partially recovers to 0.75 at 28 days, but remains below control strength (0.79) even after 90 days. These results indicate that while LS replacements up to about 40 % can ultimately achieve near-control flexural performance with sufficient curing, higher substitution levels produce permanent strength deficits under the tested conditions.

3.7. Impact and Wear Resistance of LS-Based Concrete

The influence of lithium slag (LS) on the impact and abrasion performance of white reactive powder concrete (WRPC) has been examined in a recent study by [

29]. Their experimental program incorporated LS at varying replacement levels (0–11% by cement weight) to assess its effect on mechanical durability. Impact resistance, tested in 28 days using a standardized drop-weight method, showed a notable enhancement at 5% LS content. Beyond this level, performance declined, likely due to changes in matrix toughness and microcrack propagation behavior. The improved resistance at lower LS levels was associated with enhanced interfacial bonding and densification, which allowed the material to better absorb impact energy. However, the decline at higher LS content (e.g., 11%) was attributed to increased brittleness, evidenced by a higher compressive-to-flexural strength ratio.

Wear resistance was evaluated by subjecting cube specimens to controlled surface abrasion under a fixed load. Results revealed that LS effectively enhanced abrasion resistance, with the mix containing 11% LS showing approximately half the wear loss compared to the control. This was largely credited to the filler and pozzolanic effects of LS, which refined the pore structure and improved the bond between aggregate and paste. Collectively, these findings suggest that incorporating LS in the range of 5–8% can simultaneously improve both impact and wear resistance in WRPC, making it a viable option for structural and architectural applications requiring high durability under mechanical stress.

3.8. Chemical Activation and Harsh Environment Performance of LS Concrete

Recent advances in lithium slag (LS)-based binders have highlighted the material’s potential not only as a sustainable cement substitute but also as a contributor to durability performance and enhanced reactivity in aggressive environments. Several studies have explored various strategies to optimize these properties through material design, chemical activation, and environmental exposure conditioning.

A study by [

54] investigated the freeze–thaw and sulfate resistance of recycled aggregate concrete incorporating LS. Their results revealed that a combination of 30% recycled coarse aggregate and 20% LS yielded the best resistance against cyclic deterioration. Indicators such as mass-change rate, relative dynamic modulus of elasticity (RDME), and residual compressive strength showed that moderate LS dosage significantly enhanced durability. Furthermore, they developed a damage prediction model based on RDME and compressive strength, validated through SEM analysis. However, mixes with excessive LS content displayed increased susceptibility to sulfate-induced degradation.

The role of chemical activation in improving LS reactivity was examined by [

31], who used NaOH to activate LS in a blended cementitious system. They found that increasing the NaOH content (up to 6 wt%) led to enhanced pozzolanic reaction, as evidenced by the increase in unconfined compressive strength (UCS) from early to late curing ages. At 28 and 56 days, the compressive strengths of the optimally activated system (CPL6.0) reached 32.3 MPa and 39.7 MPa, respectively approaching values obtained with traditional Portland pozzolana cement. These improvements were corroborated by TGA and SEM analysis, which revealed higher formation of C–S–H gel and a reduction in calcium hydroxide, indicating more complete hydration and improved microstructural density.

A study by [

17] focused on the corrosion behavior of LS-concrete under simulated acid rain exposure. Their study demonstrated that LS improves resistance to acid-induced degradation, leading to lower compressive strength loss and reduced mass loss during wet–dry corrosion cycles. LS-enhanced concrete exhibited superior surface integrity and microstructural compactness. The hydration products analysis revealed that LS reduces CH crystal formation and increases C–S–H gel formation, lowering the Ca/Si ratio. However, a slight increase in neutralization depth was observed, likely due to the acid sensitivity of the matrix at high LS content.

In a more advanced application, [

58] synthesized LS-based one-part geopolymers using hybrid solid activators (e.g., NaOH + Ca(OH)₂, NaOH + CaCO₃, NaOH + Na₂SiO₃). These activators not only improved mechanical strength—reaching up to 35.6 MPa at 28 days—but also refined pore structure and promoted the formation of C–A–S–H gels. Among them, CaCO₃-based activators provided the best balance between activation efficiency and environmental compatibility, offering a low-alkalinity, cost-effective route for geopolymer production.

Together, these studies demonstrate that LS’s durability and reactivity can be significantly enhanced through targeted strategies such as moderate dosage optimization, alkali activation, blending with recycled aggregates, and utilization in hybrid-activated systems. Such interventions not only unlock LS’s latent pozzolanic potential but also contribute to sustainable construction solutions in chemically and climatically aggressive environments.

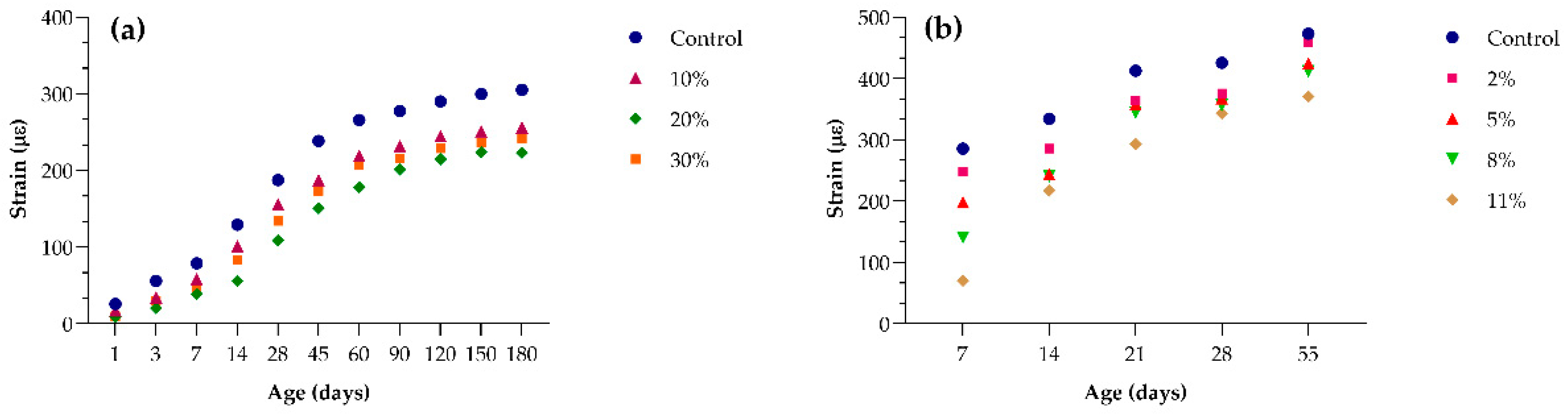

Figure 13a shows that the control mixture undergoes progressive shrinkage from about 30 µε at one day to roughly 310 µε at 180 days. Incorporating 10 % LS reduces long-term strain by approximately 10 % (to almost 280 µε), while 20 % and 30 % substitutions lower it further to ~230 µε and ~240 µε, respectively. The greatest mitigation occurs between 7 and 90 days, where the 20 % blend diverges most sharply from the control.

Figure 13b, the control reaches nearly 480 µε by 55 days. Even a 2 % LS addition cuts shrinkage to about 450 µε; higher dosages of 5 %, 8 % and 11 % progressively reduce it to approximately 425 µε, 400 µε and 375 µε, respectively. All LS-containing mixes exhibit a similar curvature of strain versus age, but the absolute magnitude of shrinkage decreases with increasing LS content. These data demonstrate that moderate LS replacement (around 20–30 %) offers the most effective long-term shrinkage control, while even small dosages (2–5 %) deliver measurable benefits.

3.9. High-Volume Lithium Slag Composite Concrete

The study by [

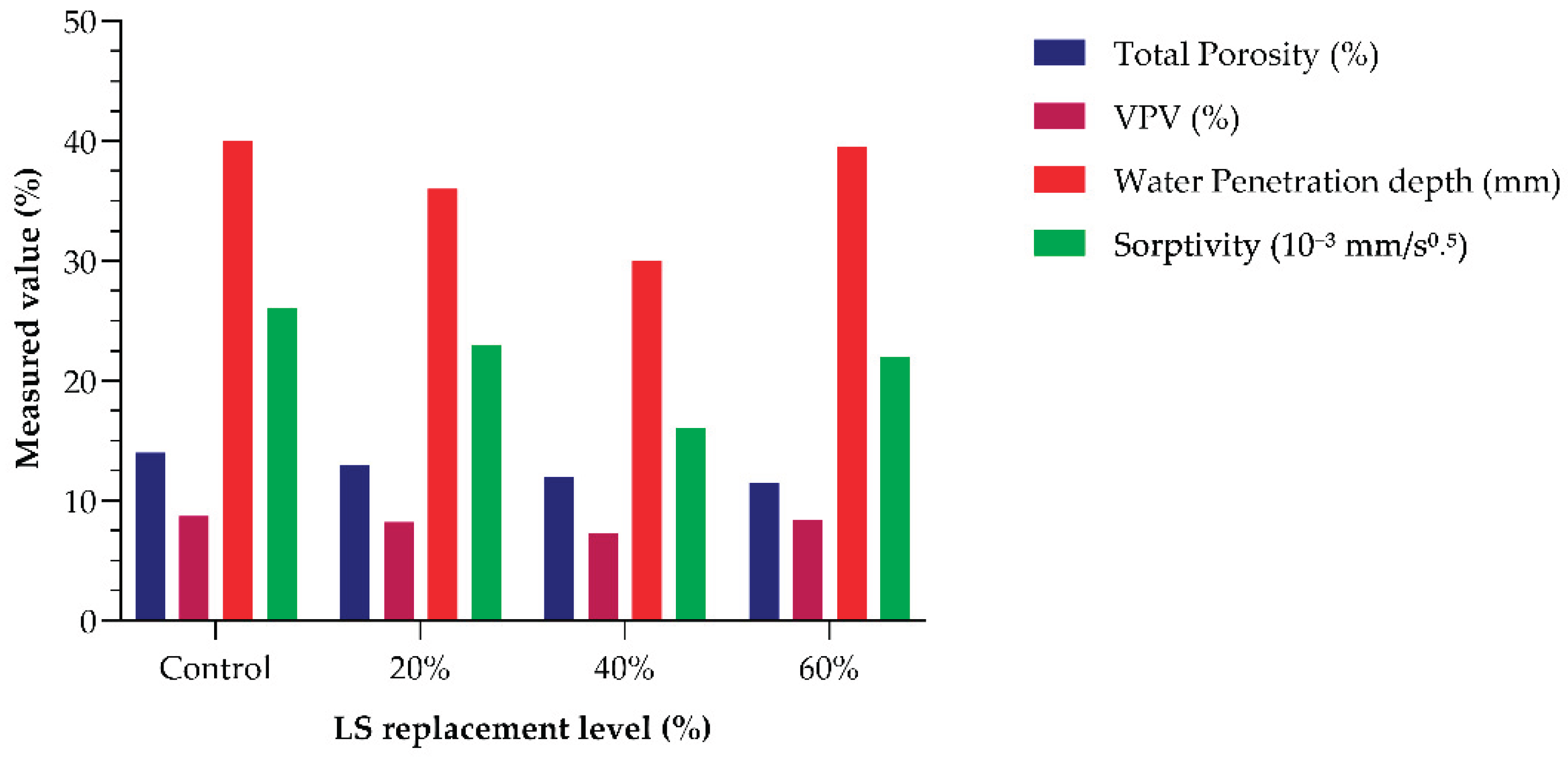

24] provides a comprehensive evaluation of concrete incorporating high volumes of lithium slag (LS) as a supplementary cementitious material (SCM), with replacement levels of 20%, 40%, and 60% by weight of cement. The investigation focused on the effects of LS on compressive strength development, transport properties, porosity, and microstructural characteristics over extended curing durations of 28, 90, and 180 days. The findings revealed that incorporating LS up to a 40% replacement level led to marked improvements in long-term mechanical and durability performance. While early-age compressive strength decreased attributed to LS’s slower pozzolanic activity and limited calcium hydroxide availability the long-term strength gain was significant. At 180 days, the 40% LS mix achieved an 18.3% higher compressive strength than the control, a result of continued hydration and the formation of additional calcium silicate hydrate (C–S–H) gel promoted by the reactive silica and alumina present in LS.

In addition to mechanical performance, the 40% LS mix exhibited the most favorable transport-related properties. At 180 days, it showed a 31.3% reduction in the volume of permeable voids (VPV), a 36% reduction in water penetration depth, and a 75.7% decrease in sorptivity relative to the control mix. These enhancements are attributed to a denser pore structure, as confirmed through porosity testing and SEM analysis. Notably, the macro-porosity of the 40% LS mix was reduced to just 1.7%, the lowest among all the tested compositions. SEM and EDS analyses also indicated the formation of secondary products such as CaCO₃ and ettringite, which contributed to additional pore refinement and matrix densification. These quantitative results are visually illustrated in

Error! Reference source not found., which compares key durability-related parameters total porosity, VPV, water penetration depth, and sorptivity across different LS replacement levels. As shown, all indicators of permeability and porosity improved substantially with 40% LS incorporation, supporting the claim of enhanced durability. In contrast, the 60% LS mix displayed a reversal in performance trends, with increased porosity, more unreacted particles, and reduced strength, likely due to insufficient calcium hydroxide for full LS activation. This study highlights the potential for using high-volume LS as a viable SCM. A replacement level of around 40% offers an optimal balance between strength development, permeability reduction, and pore structure refinement, making LS a promising material for durable and environmentally resilient concrete applications.

Figure 14.

Durability-Related Properties of LS Concrete at 180 Days data used from [

24].

Figure 14.

Durability-Related Properties of LS Concrete at 180 Days data used from [

24].

3.10. High-Temperature Performance of LS-Based Concrete

The thermal behavior of lithium slag concrete (LSC) has been studied by [

44], who investigated the residual mechanical properties of LSC exposed to elevated temperatures ranging from 100°C to 700°C. Their experimental program examined three key mechanical indicators—cube compressive strength, prism compressive strength, and flexural strength—under two cooling regimes: natural cooling (NC) and water spray cooling (WSC), across four LS replacement levels (0%, 10%, 20%, and 30%). The results revealed that moderate temperatures (up to 100°C) caused minimal strength reduction and even slight improvements in specific cases. For example, specimens with 20% LS exhibited increased prism compressive strength by approximately 8%, attributed to continued hydration and densification facilitated by water vapor entrapment. In contrast, temperatures above 300°C led to severe degradation, with concrete losing up to 80% of its compressive strength at 700°C, due to decomposition of C–S–H, dehydration of CH, and decarbonation of CaCO₃.

Among the tested mixtures, 20% LS replacement consistently exhibited the best performance across all mechanical parameters at elevated temperatures. It not only minimized mass loss but also retained higher residual strengths compared to mixes with 0%, 10%, or 30% LS. At 700°C, the flexural strength of LSC with 20% LS was approximately 50% higher than that of ordinary concrete, indicating LS’s beneficial role in delaying structural degradation under thermal stress. Interestingly, the cooling method (NC vs. WSC) had a limited impact on mechanical properties when the WSC duration was short (3–5 minutes). Although literature often highlights WSC as detrimental due to thermal shock, this study found that short-duration WSC resulted in only slightly lower strengths than NC, suggesting that LS-modified concrete may tolerate rapid post-fire cooling better than conventional mixes. Mass loss trends supported these findings. LSC with 20% LS showed the lowest weight reduction after thermal exposure, due to its dense internal microstructure formed by efficient pozzolanic reactions between SiO₂ (from LS) and Ca(OH)₂ (from cement). This densification limited both water evaporation and structural damage.

3.11. Creep Behavior of LS-Modified Concretes

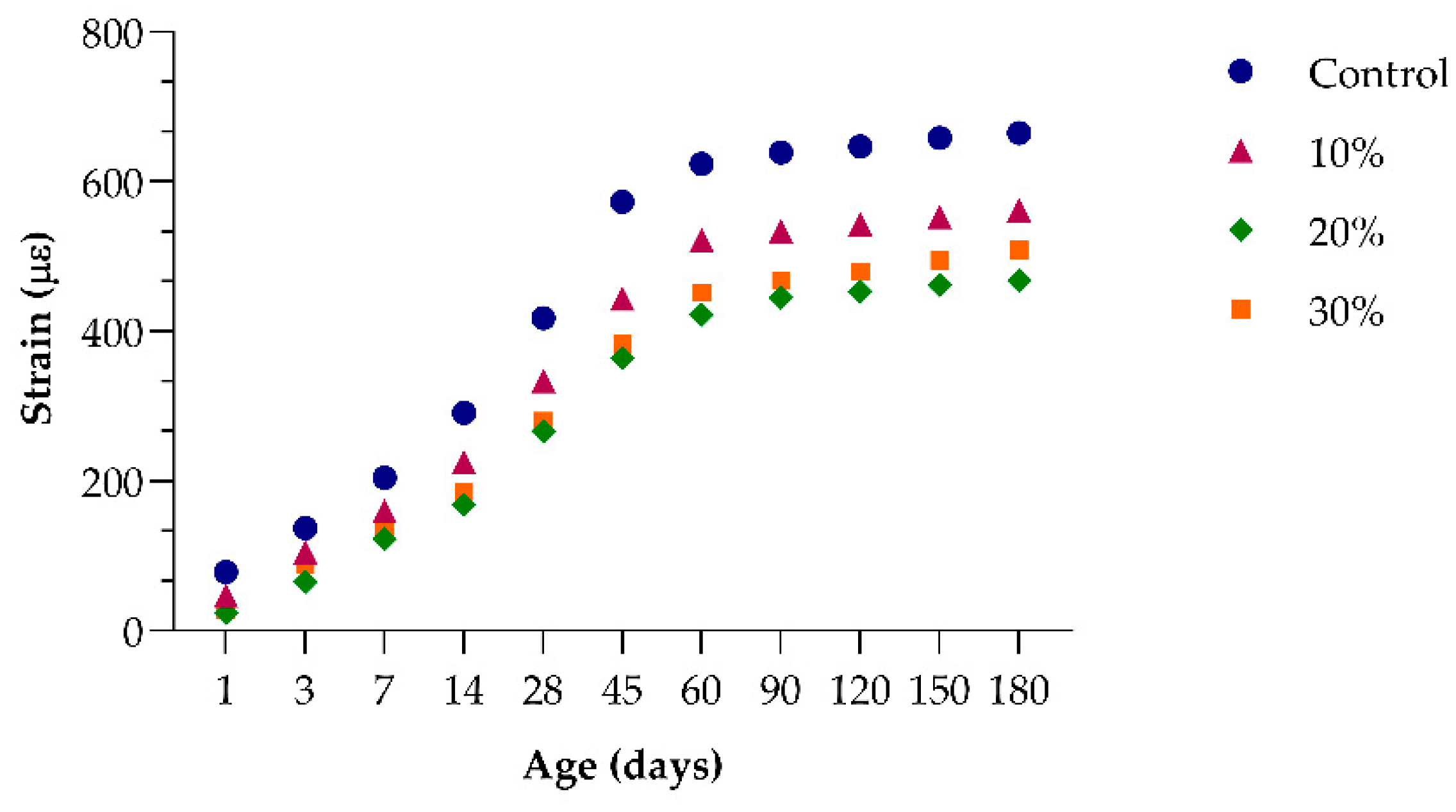

Figure 15 shows that incorporating lithium slag (LS) significantly reduces long-term creep strain in concrete in a clear, dose-dependent manner over a period of 180 days. At an early age, the control mix exhibits the highest initial creep strain, while concretes containing LS demonstrate an immediate reduction of approximately 40% to 70%, depending on the replacement level.

As curing continues, this trend remains consistent. Within the first week, the control mix develops nearly twice as much creep strain as the concrete with a 20% LS replacement, while the 10% and 30% mixes show intermediate performance with noticeable reductions compared to the control.

During the primary creep phase, which extends up to about two months, the control concrete shows the steepest increase in deformation, whereas the mixes containing LS maintain significantly lower creep values — generally around 20% to 30% less than the control.

After about three months, the creep strains tend to stabilise. By 180 days, the control mix reaches its maximum strain, while concretes with LS maintain lower final values. Notably, the mix with 20% LS consistently shows the greatest reduction, achieving almost one-third lower long-term creep than the plain concrete. The 10% and 30% substitutions also provide meaningful mitigation of time-dependent deformation, though the effect is slightly less pronounced than with the 20% replacement.

These results confirm that partial replacement of cement with moderate amounts of LS can effectively reduce creep in concrete under sustained loading, thereby enhancing long-term dimensional stability.

3.12. Application of Lithium Slag in Autoclaved Aerated Concrete (AAC)

Autoclaved aerated concrete (AAC) incorporating lithium slag (LS) was produced by replacing quartz sand (QS) using two distinct strategies: (1) “effective element control,” in which the Ca/Si ratio of the mix was held constant, and (2) “material quality control,” which maintained a fixed siliceous mass. In both methods, LS was blended with OPC, lime, gypsum, aluminum powder (0.1 % by mass) and calcium stearate (1 %), cast into 70.7 mm cubes, pre-cured at 60 °C and 50 % RH for 6 h to promote aeration, then autoclaved at 190 °C under 12 bars for 10 h before oven-drying to constant weight [

26].

Under material quality control, moderate LS substitution yielded clear gains in compressive strength and simultaneous reductions in bulk density, attributable to LS’s enhanced pozzolanic reactivity under hydrothermal conditions. The fine, reactive silica–alumina phases in LS accelerate secondary C–S–H and C–A–S–H gel formation and densify the interfacial transition zone. In contrast, excessive LS content increased slurry viscosity, impeded pore expansion during pre-curing, and disrupted the autoclave hydration process—ultimately diminishing mechanical performance [

26].

Thermal conductivity measures demonstrated that optimally dosed LS mixes exhibited lower conductivity, owing to a higher proportion of uniform, closed pores that inhibit heat transfer. However, over-replacement reversed this trend, with conductivity rising in parallel with bulk density. Water absorption tests further confirmed that balanced LS incorporation reduced capillary uptake by refining macropore connectivity; by contrast, overly high LS levels led to increased permeability [

26].

Microstructural analyses via XRD revealed that LS-AAC specimens contain unreacted crystalline residues (quartz, muscovite, spodumene), hydrothermal products (tobermorite, xonotlite, katoite), and carbonation phases (calcite). The attenuation of the 11.3 Å tobermorite peak and enhancement of the 3.5 Å reflection indicate Al

3+ substitution for Si

4+ in silicate chains, altering unit-cell dimensions. FTIR spectra corroborated these findings, showing intensified Si–O bending and stretching bands with moderate LS, while excessive Al substitution disrupted polymerization. SEM–EDS imaging confirmed a morphology shift from plate-like tobermorite in the control to needle-like, Al-substituted tobermorite and katoite in LS mixes, with atomic Al content in hydration products rising in proportion to LS dosage [

26].

Together, these results underscore that, when carefully conditioned and dosed, LS can serve as an effective supplementary siliceous material in AAC—enhancing strength, reducing density and thermal conductivity, and refining pore structure. They also highlight the necessity of establishing standardized processing protocols and mix-design guidelines to ensure reproducible, large-scale application.

4. Conclusions

This review comprehensively explored the potential of lithium slag (LS) as a supplementary cementitious material (SCM) in concrete applications. Based on the analysis of experimental findings across various studies, the following key conclusions are drawn:

1) Optimal Replacement LevelAn LS dosage of 20–30 % by mass of cement consistently delivers the best balance between mechanical strength, durability, and dimensional stability. While compressive, tensile and flexural strengths continue to benefit up to 30 % replacement, 40 % represents a practical upper limit for tensile and flexural recovery before dilution effects become prohibitive.

2) Mechanical PropertiesModerate LS incorporations (10–30 %) enhance long-term compressive strength by up to 25 % compared to control mixes, with peak gains observed at 60–90 days due to pozzolanic activity. Tensile and flexural capacities likewise exceed control values at 28 and 90 days when LS is kept below 40 %.

3) Dimensional Stability (Shrinkage and Creep)Drying shrinkage is reduced by up to 30 %, and sustained-load creep strains decrease by 30–40 % at 20–30 % LS, demonstrating dose-dependent mitigation of time-dependent deformations. These improvements contribute to crack resistance and long-term serviceability.

4) Fresh-State BehaviorThe fine, angular particles of LS increase water demand and reduce workability, but careful adjustment of superplasticizer dosage fully restores slump and flow without compromising strength or durability.

5) Durability in Aggressive EnvironmentsLS-modified concretes exhibit enhanced resistance to sulfate attack, acid exposure, abrasion, freeze–thaw cycles and chloride ingress. These gains are attributed to pore-structure refinement, increased C–S–H formation and reduced permeability.

6) High-Volume and High-Temperature PerformanceAt 40 % replacement, 180-day compressive strength can improve by up to 18 %, with sorptivity reductions exceeding 30 %. Under elevated temperatures (up to 700 °C), 20 % LS mixes retain up to 50 % more residual strength than controls.

7) Advanced Systems and Circular-Economy ApplicationsIn autoclaved aerated concrete, one-part geopolymers and recycled-aggregate concretes, LS promotes denser microstructures (e.g., tobermorite formation) and enhances durability, underscoring its versatility in low-carbon and circular construction technologies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, S.R., N.M., and T.P.; methodology, S.R.; software, S.R.; validation, S.R., N.M., and T.P.; formal analysis, S.R.; investigation, S.R.; resources, S.R.; data curation, S.R.; writing—original draft preparation, S.R.; writing—review and editing, S.R., N.M., and T.P.; visualization, S.R.; supervision, N.M., and T.P..; project administration, S.R., N.M., and T.P.; funding acquisition, N.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All novel findings and data reported in this study are fully contained within the manuscript; for any additional questions or clarifications, please contact the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LS |

Lithium slag |

| OPC |

Ordinary Portland Cement |

| SCM(s) |

Supplementary cementitious material(s) |

| GGBFS |

Ground granulated blast-furnace slag |

| AAC |

Autoclaved aerated concrete |

| UHPC |

Ultra-high-performance concrete |

| HPC |

High performance concrete |

| RCC |

Roller compacted concrete |

| SCC |

Self-compacting concrete |

| WRPC |

White reactive powder concrete |

| C–S–H |

Calcium silicate hydrate |

| C–A–S–H |

Calcium aluminosilicate hydrate |

| VPV |

Volume of permeable voids |

| WRC |

Water-retention capacity |

| SP(s) |

Superplasticizer(s) |

| UCS |

Unconfined compressive strength |

| RDME |

Relative dynamic modulus of elasticity |

| TGA |

Thermogravimetric analysis |

| SEM |

Scanning electron microscopy |

| EDS |

Energy-dispersive X-ray spectroscopy |

| LCA |

Life-cycle assessment |

References

- Luo, Q.; Wen, Y.F.; Huang, S.W.; Peng, W.L.; Li, J.Y.; Zhou, Y.X. Effects of Lithium Slag from Lepidolite on Portland Cement Concrete: Qi Luo Yufeng Wen, Shaowen Huang, Weiliang Peng, Jinyang Li & Yuxuan Zhou. In Civil, Architecture and Environmental Engineering; CRC Press, 2017; pp. 620–623.

- He, Z.; Du, S.; Chen, D. Microstructure of Ultra High Performance Concrete Containing Lithium Slag. J Hazard Mater 2018, 353, 35–43. [CrossRef]

- Griffin, J. Lithium-Ion Batteries. Electrical Contractor. 2019, 84, 110–111.

- Zhai, M.; Zhao, J.; Wang, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, Q. Hydration Properties and Kinetic Characteristics of Blended Cement Containing Lithium Slag Powder. Journal of Building Engineering 2021, 39, 102287. [CrossRef]

- Tabelin, C.B.; Dallas, J.; Casanova, S.; Pelech, T.; Bournival, G.; Saydam, S.; Canbulat, I. Towards a Low-Carbon Society: A Review of Lithium Resource Availability, Challenges and Innovations in Mining, Extraction and Recycling, and Future Perspectives. Miner Eng 2021, 163, 106743. [CrossRef]

- Yang, B.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Sun, H.; Wang, Q.; Han, D. Recycling Lithium Slag into Eco-Friendly Ultra-High Performance Concrete: Hydration Process, Microstructure Development, and Environmental Benefits. Journal of Building Engineering 2024, 91, 109563. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.M.A.; Dodd, A.; Khair, S.; Shaikh, F.U.A.; Sarker, P.K.; Hosan, A. Assessment of Lithium Slag as a Supplementary Cementitious Material: Pozzolanic Activity and Microstructure Development. Cem Concr Compos 2023, 143, 105262. [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Wang, J.; Li, L.; Wang, D. Characteristics of Alkali-Activated Lithium Slag at Early Reaction Age. Journal of materials in civil engineering 2019, 31, 4019312. [CrossRef]

- Adediran, A.; Rajczakowska, M.; Steelandt, A.; Novakova, I.; Cwirzen, A.; Perumal, P. Conventional and Potential Alternative Non-Conventional Raw Materials Available in Nordic Countries for Low-Carbon Concrete: A Review. Journal of Building Engineering 2025, 112384. [CrossRef]

- Gao, W.; Jian, S.; Li, X.; Tan, H.; Li, B.; Lv, Y.; Huang, J. The Use of Contaminated Soil and Lithium Slag for the Production of Sustainable Lightweight Aggregate. J Clean Prod 2022, 348, 131361. [CrossRef]

- Zetola, V.; Keith, B.F.; Lam, E.J.; Montofré, Í.L.; Rojas, R.J.; Marín, J.; Becerra, M. From Mine Waste to Construction Materials: A Bibliometric Analysis of Mining Waste Recovery and Tailing Utilization in Construction. Sustainability (2071-1050) 2024, 16. [CrossRef]

- El Machi, A.; El Berdai, Y.; Mabroum, S.; Safhi, A. el M.; Taha, Y.; Benzaazoua, M.; Hakkou, R. Recycling of Mine Wastes in the Concrete Industry: A Review. Buildings 2024, 14, 1508. [CrossRef]

- Zabielska-Adamska, K. Industrial By-Products and Waste Materials in Geotechnical Engineering Applications. In Emerging Trends in Sustainable Geotechnics: Keynote Volume of EGRWSE 2024; Springer, 2025; pp. 47–76.

- Villagran-Zaccardi, Y.; Carreño, F.; Granheim, L.; Espín de Gea, A.; Smith Minke, U.; Butera, S.; López-Martínez, E.; Peys, A. Valorisation of Aggregate-Washing Sludges in Innovative Applications in Construction. Materials 2024, 17, 4892. [CrossRef]

- Saluja, S.; Gaur, A.; Somani, P.; Abbas, S. Use of Stabilized Waste Soil in the Construction of Sustainable Concrete. In Recent Developments and Innovations in the Sustainable Production of Concrete; Elsevier, 2025; pp. 391–413.

- Guo, C.; Wang, R. Utilizing Lithium Slag to Improve the Physical-Chemical Properties of Alkali-Activated Metakaolin-Slag Pastes: Cost and Energy Analysis. Constr Build Mater 2023, 403, 133164. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Pan, Y.; Xu, K.; Bi, L.; Chen, M.; Han, B. Corrosion Behavior of Concrete Fabricated with Lithium Slag as Corrosion Inhibitor under Simulated Acid Rain Corrosion Action. J Clean Prod 2022, 377, 134300. [CrossRef]

- BEGENTAYEV, M.M.; NURPEISOVA, M.B.; FEDOTENKO, V.S. THE USE OF MINING AND METALLURGY WASTE IN MANUFACTURE OF BUILDING MATERIALS. Technical Sciences 2020, 6, 194–202. [CrossRef]

- Bueno-Gómez, T.; López-Bernier, Y.; Caycedo-García, M.S.; Ardila-Rey, J.D.; Rodríguez-Caicedo, J.P.; Joya-Cárdenas, D.R. Valorization of Gold Mining Tailings Sludge from Vetas, Colombia as Partial Cement Replacement in Concrete Mixes. Buildings 2025, 15, 1419. [CrossRef]

- Wen, H. Property Research of Green Concrete Mixed with Lithium Slag and Limestone Flour. Adv Mat Res 2013, 765, 3120–3124. [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.F.; Shi, K. Bin; Dong, S.K. Influence of Concrete with Lithium-Slag and Steel Slag by Early Curing Conditions. Key Eng Mater 2014, 599, 52–55. [CrossRef]

- Gu, T.; Zhang, G.; Wang, Z.; Liu, L.; Zhang, L.; Wang, W.; Huang, Y.; Dan, Y.; Zhao, P.; He, Y. The Formation, Characteristics, and Resource Utilization of Lithium Slag. Constr Build Mater 2024, 432, 136648. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.M.A.; Shaikh, F.U.A.; Sarker, P.K. Fresh, Mechanical, and Microstructural Properties of Lithium Slag Concretes. Cem Concr Compos 2024, 148, 105469. [CrossRef]

- Amin, M.T.E.; Sarker, P.K.; Shaikh, F.U.A. Transport Properties of Concrete Containing Lithium Slag. Constr Build Mater 2024, 416, 135073. [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-B.; Liang, J.-F.; Li, W. Compression Stress-Strain Curve of Lithium Slag Recycled Fine Aggregate Concrete. PLoS One 2024, 19, e0302176. [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Gu, X.; Liu, J.; Zhu, Z.; Wang, H.; Ge, X.; Hu, Z.; Xu, X.; Nehdi, M.L. Assessment of Lithium Slag as a Supplementary Siliceous Material in Autoclaved Aerated Concrete: Physical Properties and Hydration Characteristics. Constr Build Mater 2024, 442, 137621. [CrossRef]

- Gou, H.; Rupasinghe, M.; Sofi, M.; Sharma, R.; Ranzi, G.; Mendis, P.; Zhang, Z. A Review on Cementitious and Geopolymer Composites with Lithium Slag Incorporation. Materials 2023, 17, 142. [CrossRef]

- Li, B.; Cao, R.; You, N.; Chen, C.; Zhang, Y. Products and Properties of Steam Cured Cement Mortar Containing Lithium Slag under Partial Immersion in Sulfate Solution. Constr Build Mater 2019, 220, 596–606. [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Huang, S. Recycling of Lithium Slag as a Green Admixture for White Reactive Powder Concrete. J Mater Cycles Waste Manag 2020, 22, 1818–1827. [CrossRef]

- Qi, L.; Shaowen, H.; Yuxuan, Z.; Jinyang, L.; Weiliang, P.; Yufeng, W. Influence of Lithium Slag from Lepidolite on the Durability of Concrete. In Proceedings of the IOP conference series: earth and environmental science; IOP Publishing, 2017; Vol. 61, p. 12151.

- He, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Chen, Q.; Bian, J.; Qi, C.; Kang, Q.; Feng, Y. Mechanical and Environmental Characteristics of Cemented Paste Backfill Containing Lithium Slag-Blended Binder. Constr Build Mater 2021, 271, 121567. [CrossRef]

- Foghi, E.J.; Vo, T.; Rezania, M.; Nezhad, M.M.; Ferrara, L. Early Age Hydration Behaviour of Foam Concrete Containing a Coal Mining Waste: Novel Experimental Procedures and Effects of Capillary Pressure. Constr Build Mater 2024, 414, 134811. [CrossRef]

- Silva, Y.F.; Burbano-Garcia, C.; Araya-Letelier, G.; Izquierdo, S. Sulfate Attack Performance of Concrete Mixtures with Use of Copper Slag as Supplementary Cementitious Material. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2025, e04846. [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Tang, X.; Xia, J. Functional Characteristics of Sustainable Pervious Cement Concrete Pavement Modified by Silica Fume and Travertine Waste. Ceramics–Silikáty 2024, 68, 582–597.

- Gou, H.; Rupasinghe, M.; Sofi, M.; Sharma, R.; Ranzi, G.; Mendis, P.; Zhang, Z. A Review on Cementitious and Geopolymer Composites with Lithium Slag Incorporation. Materials 2023, 17, 142.

- de Souza, E.A.; de Kássia Rodrigues e Silva, R.; Borges, P.H.R. Overburden Materials from the Iron Mining as Raw Materials for AAM: Preliminary Assessment of Mixes for 3D Concrete Printing. In Proceedings of the FIB International Conference on Concrete Sustainability; Springer, 2024; pp. 414–421.

- Mim, N.J.; Shaikh, F.U.A.; Sarker, P.K. Sustainable 3D Printed Concrete Incorporating Alternative Fine Aggregates: A Review. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2025, e04570. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.M.A.; Mahmood, A.H.; Shaikh, F.U.A.; Sarker, P.K. Fresh State and Hydration Properties of High-Volume Lithium Slag Cement Composites. Mater Struct 2023, 56, 91. [CrossRef]

- Sousa, J.T.F. de; Anjos, M.A.S. dos; Neto, J.A. da S.; Farias, E.C. de; Branco, F.G.; Maia Pederneiras, C. Self-Compacting Concrete with Artificial Lightweight Aggregates from Sugarcane Ash and Calcined Scheelite Mining Waste. Applied Sciences 2025, 15, 452. [CrossRef]

- Cuenca, E.; Del Galdo, M.; Aboutaybi, O.; Ramos, V.; Nash, W.; Rollinson, G.K.; Andersen, J.; Crane, R.; Ghorbel, E.; Ferrara, L. Mechanical Characterization of Cement Mortars and Concrete with Recycled Aggregates from Coal Mining Wastes Geomaterials (CMWGs). Constr Build Mater 2024, 432, 136640. [CrossRef]

- Wu, F.F.; Shi, K. Bin; Dong, S.K. Properties and Microstructure of HPC with Lithium-Slag and Fly Ash. Key Eng Mater 2014, 599, 70–73. [CrossRef]

- Vigneshwari, A.; Jayaprakash, J. A Review on 3D Printable Cementitious Material Containing Copper and Iron Ore Tailings: Material Characterization, Activation Methods, Engineering Properties, Durability, and Microstructure Behavior. Innovative Infrastructure Solutions 2024, 9, 74. [CrossRef]

- Yu, H.; Zahidi, I.; Chow, M.F.; Liang, D.; Madsen, D.Ø. Reimagining Resources Policy: Synergizing Mining Waste Utilization for Sustainable Construction Practices. J Clean Prod 2024, 464, 142795. [CrossRef]

- Liang, J.; Zou, W.; Tian, Y.; Wang, C.; Li, W. Effect of High Temperature on Mechanical Properties of Lithium Slag Concrete. Sci Rep 2024, 14, 11872. [CrossRef]

- Zhai, J.; Chen, P.; Long, J.; Fan, C.; Chen, Z.; Sun, W. Recent Advances on Beneficial Management of Lithium Refinery Residue in China. Miner Eng 2024, 208, 108586. [CrossRef]

- Javed, U.; Shaikh, F.U.A.; Sarker, P.K. Corrosive Effect of HCl and H2SO4 Exposure on the Strength and Microstructure of Lithium Slag Geopolymer Mortars. Constr Build Mater 2024, 411, 134588. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; Kang, Q.; Lan, M.; Peng, H. Mechanism and Assessment of the Pozzolanic Activity of Melting-Quenching Lithium Slag Modified with MgO. Constr Build Mater 2023, 363, 129692. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Yang, B.; Gu, X.; Han, D.; Wang, Q. Improving the Performance of Ultra-High Performance Concrete Containing Lithium Slag by Incorporating Limestone Powder. Journal of Building Engineering 2023, 72, 106610. [CrossRef]

- Khair, S.; Rahman, S.M.A.; Shaikh, F.U.A.; Sarker, P.K. Evaluating Lithium Slag for Geopolymer Concrete: A Review of Its Properties and Sustainable Construction Applications. Case Studies in Construction Materials 2024, 20, e02822. [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Li, M.; He, X.; Su, Y.; Zhang, J.; Pan, H.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y. Preparation for Micro-Lithium Slag via Wet Grinding and Its Application as Accelerator in Portland Cement. J Clean Prod 2020, 250, 119528. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Chen, J.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Y. The Mechanical Properties of Recycled Coarse Aggregate Concrete with Lithium Slag. Advances in Materials Science and Engineering 2019, 2019, 8974625. [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Zhang, X.; He, X.; Guo, Y.; Deng, X.; Su, Y.; Yang, J.; Wang, Y. Utilization of Lithium Slag by Wet-Grinding Process to Improve the Early Strength of Sulphoaluminate Cement Paste. J Clean Prod 2018, 205, 536–551. [CrossRef]

- He, Z.; Li, L.; Du, S. Mechanical Properties, Drying Shrinkage, and Creep of Concrete Containing Lithium Slag. Constr Build Mater 2017, 147, 296–304. [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Chen, J.; Liu, K.; Lu, Y. Durability Properties of Recycled Concrete with Lithium Slag under Freeze-Thaw Cycles. Materials and technology 2021, 55, 171–181. [CrossRef]

- Shi, K. Bin; Zhang, S. De Ring Method Test on the Early-Age Anti-Cracking Capability of High-Performance Lithium Slag Concrete. Applied Mechanics and Materials 2011, 94, 782–785.

- He, Z.; Chang, J.; Du, S.; Liang, C.; Liu, B. Hydration and Microstructure of Concrete Containing High Volume Lithium Slag. Materials Express 2020, 10, 430–436. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, S.A.; Shaikh, F.U.A.; Sarker, P.K. A Comprehensive Review of Properties of Concrete Containing Lithium Refinery Residue as Partial Replacement of Cement. Constr Build Mater 2022, 328, 127053. [CrossRef]

- Luo, Q.; Liu, Y.; Dong, B.; Ren, J.; He, Y.; Wu, K.; Wang, Y. Lithium Slag-Based Geopolymer Synthesized with Hybrid Solid Activators. Constr Build Mater 2023, 365, 130070. [CrossRef]

- He, Y.; You, C.; Jiang, M.; Liu, S.; Shen, J.; Hooton, R.D. Rheological Performance and Hydration Kinetics of Lithium Slag-Cement Binder in the Function of Sodium Sulfate. J Therm Anal Calorim 2023, 148, 11653–11668. [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wang, Q.; Han, D.; Li, Z. Iron Ore Tailings, Phosphate Slags, and Lithium Slags as Ternary Supplementary Cementitious Materials for Concrete: Study on Compression Strength and Microstructure. Mater Today Commun 2023, 36, 106644. [CrossRef]

- Zhou, M.; Yan, J.; Fan, J.; Xu, Y.; Lu, Y.; Duan, P.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, Z. Insight to Workability, Compressive Strength and Microstructure of Lithium Slag-Steel Slag Based Cement under Standard Condition. Journal of Building Engineering 2023, 75, 107076.

- Liuzhuo, C.; Jitao, Y.; Guangtai, Z. Flexural Properties of Lithium Slag Concrete Beams Subjected to Loading and Thermal-Cold Cycles. 2018. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).