Submitted:

06 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

I. Introduction

II. Related Work

III. Methodologies

A. Combined Concentration–Toxicity Modeling Module

B. Exposure Threshold Derivation and Decision-making

IV. Experiments

A. Experimental Setup

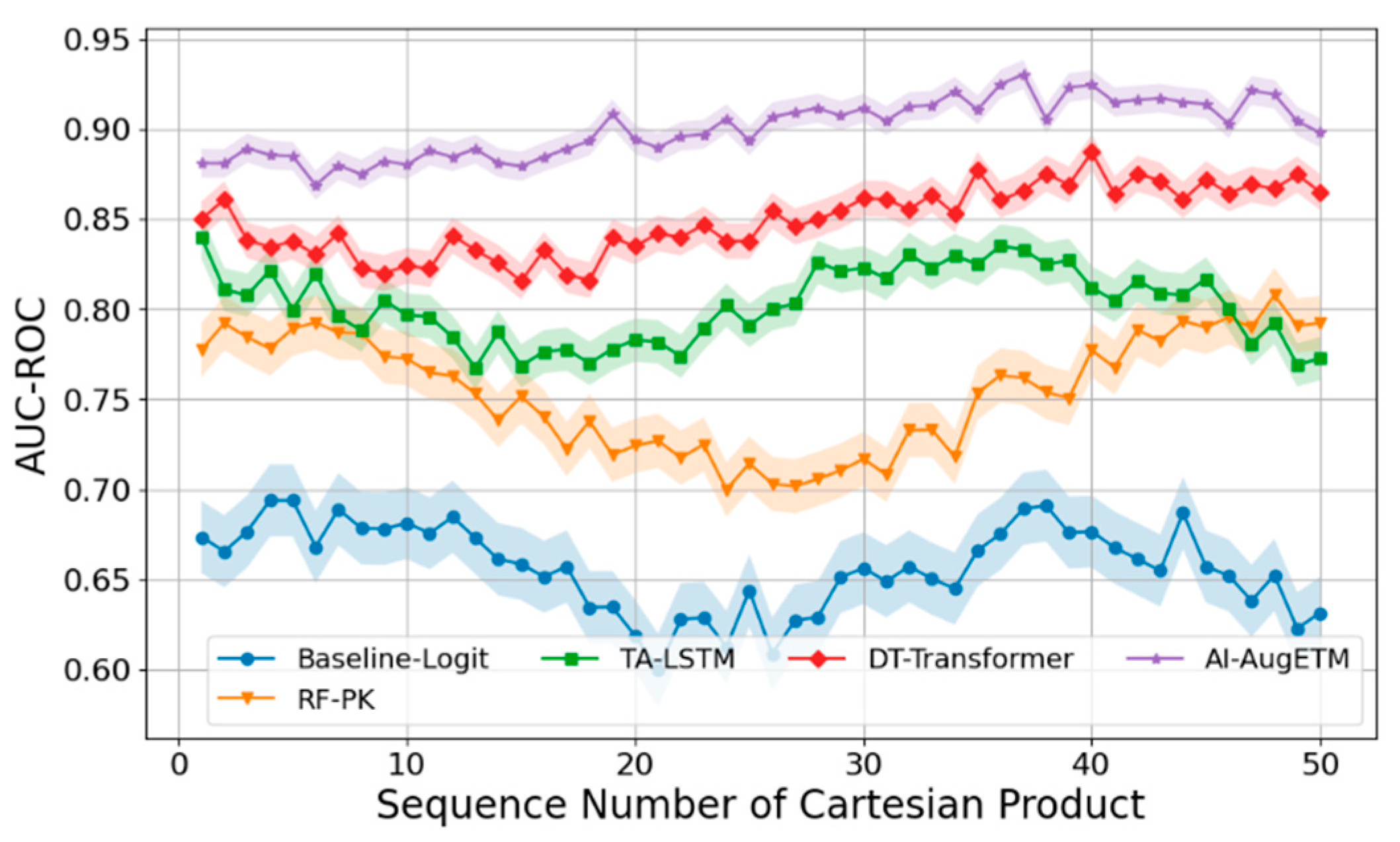

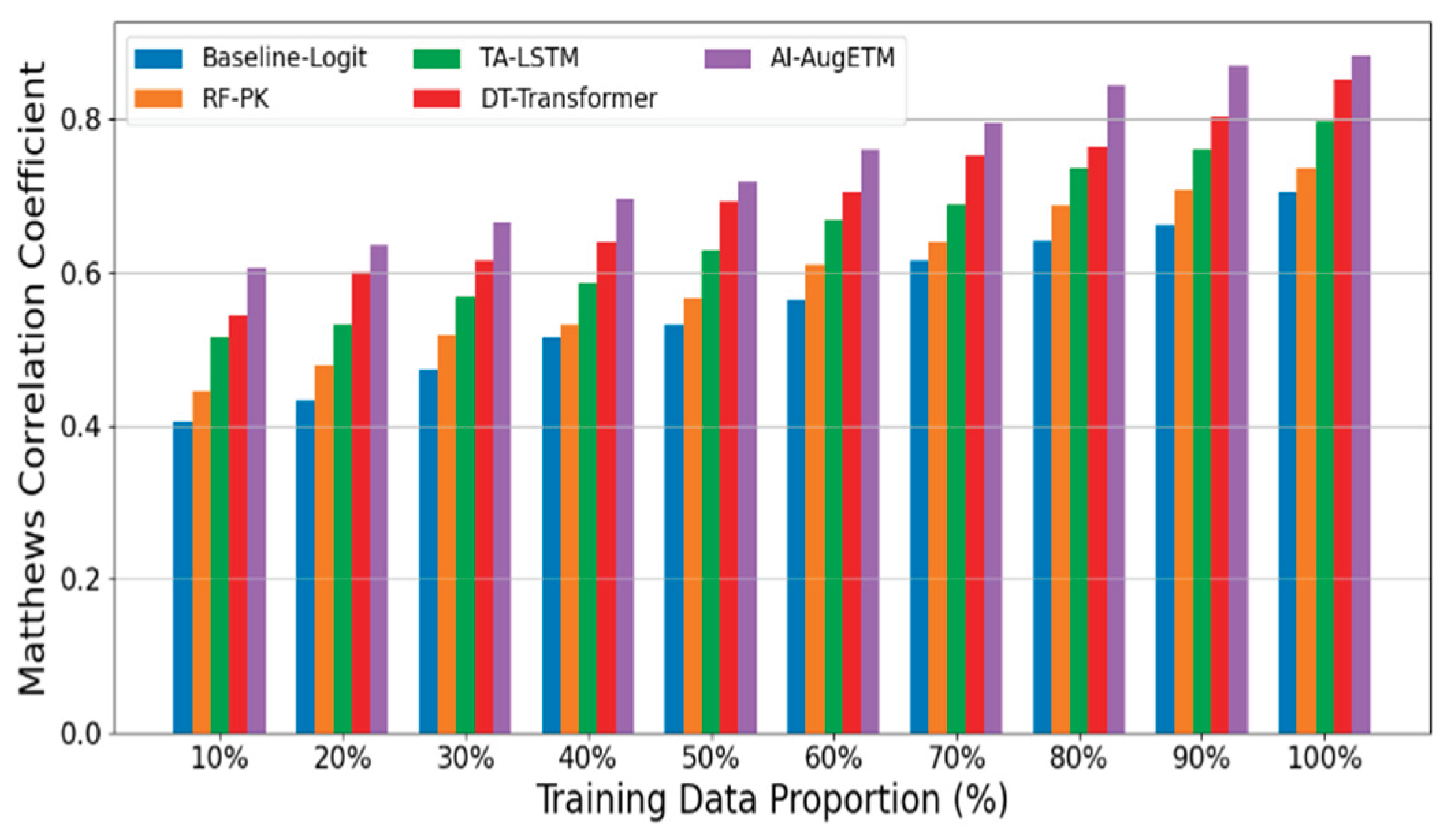

- Logistic Regression + AUC Feature (Baseline-Logit) fed the AUC of each patient into the logistic regression model as the main exposure variable to fit the probability of occurrence of toxic events.

- Random Forest Classifier + PK Summary Features (RF-PK) has strong nonlinear fitting ability, and the toxicity probability prediction is carried out through tree model ensemble. Although the model can capture the complex relationships between variables to a certain extent, it cannot make use of the complete time series concentration information.

- The Time-Aware LSTM Toxicity Predictor (TA-LSTM) uses a long short-term memory network (LSTM) to directly model a patient's PK concentration time series to predict the risk of toxicity.

- As a sequence modeling method based on self-attention mechanism, DeepTox-Transformer (DT-Transformer) has shown excellent performance in multiple toxicity prediction tasks.

B. Experimental Analysis

V. Conclusions

References

- Shaer, O., Cooper, A., Mokryn, O., Kun, A. L., & Ben Shoshan, H. (2024). AI-Augmented Brainwriting: Investigating the use of LLMs in group ideation. In Proceedings of the 2024 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (pp. 1-17).

- Jia, C.; Lam, M.S.; Mai, M.C.; Hancock, J.T.; Bernstein, M.S. Embedding Democratic Values into Social Media AIs via Societal Objective Functions. Proc. ACM Human-Computer Interact. 2024, 8, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Currie, G.; Rohren, E.; Hawk, K.E. (2024). The role of artificial intelligence in supporting person-centred care. In Person-Centred Care in Radiology (pp. 343-362).

- Donvir, A. , & Sharma, G. (2025). Ethical Challenges and Frameworks in AI-Driven Software Development and Testing. In 2025 IEEE 15th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC) (pp. 00569-00576). IEEE.

- Zheng, Y.; Chen, Z.; Huang, S.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Hong, S.; Chan, J.S.K.; Chen, K.-Y.; Xia, Y.; Zhang, Y.; et al. Machine Learning in Cardio-Oncology: New Insights from an Emerging Discipline. Rev. Cardiovasc. Med. 2023, 24, 296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, G. , Chen, H., & Yue, J. (2024). Deep learning to optimize radiotherapy decisions for elderly patients with early-stage breast cancer: a novel approach for personalized treatment. American Journal of Cancer Research, 14(12), 5885.

- Chen, L.; Xiao, S.; Chen, Y.; Song, Y.; Wu, R.; Sun, L. ChatScratch: An AI-Augmented System Toward Autonomous Visual Programming Learning for Children Aged 6-12. CHI '24: CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–19.

- Manalad, J.; Montgomery, L.; Kildea, J. Estimating the impact of indirect action in neutron-induced DNA damage clusters and neutron RBE. Ann. ICRP 2023, 52, 87–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Rocco, J. , Di Ruscio, D., Di Sipio, C., Nguyen, P. T., & Rubei, R. (2025). On the use of large language models in model-driven engineering. Software and Systems Modeling, 1-26.

- Johnson, J. ‘Catalytic nuclear war’ in the age of artificial intelligence & autonomy: Emerging military technology and escalation risk between nuclear-armed states. J. Strat. Stud. 2021, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Gao, J.; Dhaliwal, R.S.; Li, T.J.-J. VISAR: A Human-AI Argumentative Writing Assistant with Visual Programming and Rapid Draft Prototyping. UIST '23: The 36th Annual ACM Symposium on User Interface Software and Technology. LOCATION OF CONFERENCE, United StatesDATE OF CONFERENCE; pp. 1–30.

| Risk Tolerance Threshold (%) | Baseline-Logit | RF-PK | TA-LSTM | DT-Transformer | AI-AugETM |

| 5 | 0.504967 | 0.545366 | 0.614656 | 0.643983 | 0.707385 |

| 10 | 0.526395 | 0.57312 | 0.62552 | 0.696301 | 0.729491 |

| 15 | 0.562032 | 0.607975 | 0.656231 | 0.705421 | 0.754399 |

| 20 | 0.598564 | 0.614201 | 0.669086 | 0.722756 | 0.780322 |

| 25 | 0.60877 | 0.643862 | 0.705667 | 0.769337 | 0.796326 |

| 30 | 0.636548 | 0.683266 | 0.739998 | 0.77668 | 0.83169 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).