1. Introduction

HER2 stands for human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, which is a transmembrane receptor protein and a member of the tyrosine kinase receptor family. Its localization is broad in multiple tissue cells. Under normal physiologic circumstances, HER2 is an important regulator of cell proliferation, differentiation, and survival. Nevertheless, in the case of some cancer types, HER2 gene amplification and protein overexpression is significantly high, particularly in breast cancer [1]. In the case of cancer, HER2 overexpression is observed in around 20–30% of breast cancer patients, with a clinically significant group also seen in other cancer types, including gastric and ovarian cancer. HER2 expression is known to promote tumorigenesis and tumor progression, also correlated with more aggressive tumor features, increased cell migration and anti-apoptosis. Numerous studies have verified the relationship between HER2 expression and tumor aggressiveness, fast growth rate, and bad prognosis. HER2-positive tumor cells typically exhibit increased proliferation and drug resistance, leading to rapid disease progression and increased recurrence.

In particular, a study performed on breast cancer patients concluded that HER2-positive patients had significantly lower five-year survival rates than their HER2-negative counterparts, as well as an approximate 50% increase in risk of disease progression without targeted therapy [2]. Additionally, HER2 overexpression has recently been recognized as a contributing factor to a wide number of endocrine therapies and chemotherapeutic agents including palbociclib, abemaciclib, and anastrozole, further limiting the effectiveness of standard therapies. Therefore, HER2 targeted therapy has become one of the most important research focuses of cancer therapy, aiming to control the growth and spread of tumors by specifically blocking the activation of HER2 signaling pathway. Trastuzumab and other anti-HER2 drugs have been shown in extensive clinical studies to improve outc... Trastuzumab is a murine monoclonal antibody which, by specifically binding to HER2 receptors, inhibits the proliferation of tumor cells and induces apoptosis by blocking downstream signaling pathways. Since its approval from the Food and Drug Administration in 1998, trastuzumab has resulted in meaningful declines in the rates of recurrence and mortality among patients diagnosed with HER2-positive breast cancer.

In addition, early-phase studies previously reported the clinical efficacy of other anti-HER2 agents, such as pertuzumab (Perjeta) and lapatinib (Tykerb) [3]. Nevertheless, recent advances in anti-HER2 therapy, and the need to optimize its clinical trial strategy present many challenges. These challenges include patient heterogeneity, drug tolerability, and the complexity of trial design, all of which impact the efficiency of anti-HER2 drug development and the speed of market introduction. The traditional clinical trial design for anti-HER2 drugs is rooted in traditional statistical methods and empirical principles that usually depend on pre-defined dose escalations and fixed-patient- recruitment models [4]. This perspective is usually inadequate when it comes to adapting to real-time data and ultimately does not utilize the complete spectrum information from complex clinical and genomic data [5]. This makes the trials inefficient, expensive and lengthy. A good example of this is the clinical trials can take years, thus delaying the release of new drugs to the market [6].

Additionally, fixed trial designs are inherently rigid, limiting the ability to accommodate individual patient differences and changing disease characteristics, and compromising the ability to make timely mid-course adjustments to the trial design to reflect recent discoveries and needs. This rigid design not only increases the chances of trial failure but also leads to inefficient Resource Utilization. Therefore, there is an immediate demand for modern data analysis and optimization technologies to increase the accuracy of clinical trial design and execution, decrease time to conduct trials, reduce expenses, and increase the success rate of clinical trials.

Over the last few years, Bayesian optimization has established itself as a leading method for global optimization with proven effectiveness in a variety of fields, especially in high-dimensional and complex search spaces. At the core of the power of Bayesian optimization is the use of a probabilistic model of the objective function, allowing the search strategy to adapt in every iteration. Built upon previously gained knowledge/reinforcement as well as observed data, they enable to speed of convergence to the approximately most effective parameters in surprisingly less number of experiments. Entry-level techniques are based on surrogate models that approximate the conditional distribution of the objective function, and point selection then occurs based on the acquisition function, e.g., Bayesian optimization applies a probabilistic model (GP) to model the objective function and the next point is selected based on the acquisition function. This allows for a healthy balance between exploration and extraction. It has demonstrated state-of-the-art performance on multi-objective optimization problems with uncertainty [7]. Using this approach is a particularly good fit for the complex requirements of clinical trial design, including trade-offs among many trial parameters to maximize trial efficiency and effectiveness.

2. Related Work

Most importantly, Wynn and Tang [8] provided an in-depth review of the therapeutic modalities and future directions of anti-HER2 therapy in MBC. This study is limited to the drugs currently available on the market that specifically target HER2, including trastuzumab (Herceptin), pertuzumab (Perjeta), T-DM1 (Kadcyla), and others. It also considers their impacts in distinct clinical settings and the evolution of clinical trials. Therapeutic anti-HER2 drugs to date have expanded to a diverse range of treatment approaches involving both novel drug development and improved treatment combinations. In their study, Liao et al. We discussed dose optimization strategies for antibody-drug conjugates (ADCs) in oncology, and how to learn from the experience of antibody-drug conjugates that have been approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) [9]. As this study details, this dose optimization is too crucial, as well as dose adjustment methodologies for various ADCs relevant to their clinical trials. These findings from the study underscore the progress in Utilization of ADCs to help treat cancer especially targeted therapies like HER2-positive breast cancer.

This study is a bibliometric analysis by Xing et al. This review/article describes the current status of ADCs in breast cancer and their clinical development [10]. By using a systematic review of a large body of literature and analysis of clinical trial data, this study endeavours to elucidate the therapeutic effect, developmental trend and research priorities associated with ADC in the treatment of breast cancer. The application and recent advances of HER2-targeted therapy in non-breast (and non-colorectal) cancers were highlighted in a separate study [11] by Yoon et al. Although HER2-targeted therapies were originally designed for breast cancer, the use of HER2-targeted treatment has also spread to multiple solid tumors as we learn more about the contribution of HER2 to the etiology of other cancers, including gastric cancer, ovarian cancer and lung cancer.

In the 2022 version of CSCO guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of breast cancer, the authors Bian et al. [12], which addressed the treatment strategy of anti-HER2-targeted tyrosine kinase inhibitors (TKIs). The aim of this study is to improve the follow-up therapy of HER2-positive breast cancer patients after anti-HER2 TKIs (i.e., lapatinib, afatinib, etc.) treatment. Tarantino et al. These insights are critical for the safety optimization of the antibody-drug conjugate (ADCs) development in solid tumors. The study systematically reviews the safety issues related to ADC drugs and suggests a number of approaches for optimizing the dosage and treatment schemes in clinical studies. ADC is a potent targeted therapy with proven effectiveness against HER2-positive breast cancer, gastric cancer and other neoplasms.

Chen et al. This [14] and other deep learning methods have also been used in the selection of personalized teaching strategies, subverting traditional teaching methods, and providing an adjustable learning path can be adjusted dynamically with big data and AI as the driving force. Through utilizing students' historical learning data and real-time feedback, personalized instructional strategies can enhance learning efficiency and the individual needs of students without compromising quality of education. Wang et al. According to [15], the traditional text discrimination methods could no longer keep up with the challenge brought by new text generation technologies, due to the rapid development of AI-generated text technology. Hence, deep learning algorithms, particularly the BERT model, can effectively enhance the detection accuracy of text generation source, and also provides a new solution for curbing false information and news counterfeiting.

3. Methodologies

3.1. Model Construction and Bayesian Optimization

Above all, it is important to consider that the data from clinical trials contain multi-dimensional clinical indicators and genomic data, which can be expressed as high-dimensional feature vectors

. In order to effectively process these high-dimensional data, normalize the processing, as shown in Equation 1:

where

and

are the mean and standard deviation of the

features, respectively. Subsequently, principal component analysis (PCA) is

employed for dimensionality reduction, and the principal component

, where

, is retained to reduce the computational complexity,

as demonstrated in Equation 2:

It is evident that

is the projection matrix of PCA. Following the

implementation of feature preprocessing, the deep neural network is represented

by the function

, in which

denotes a network parameter. The network consists

of

-layers, fully connected layers, and the output of

each layer is processed by a nonlinear activation function

. Batch normalization and discard layers are introduced to enhance the generalization ability of the model, as shown in Equation 3:

The weight matrix and bias vector of layer l are denoted by

and

, respectively. The bias vector of layer l is set

to z, i.e.

. In order to capture the complex dynamics of

patient responses more effectively, time series modelling is introduced. This

is based on the assumption that the change in patient responses with time

can be expressed as shown in Equation 4:

where

denotes the treatment response at time

and

is the Gaussian noise. In the Bayesian

optimization component, the objective is to enhance the clinical trial

parameters

, including drug dosage and patient recruitment

rate, with the aim of optimising the objective function

. The establishment of a prior distribution for the

objective function

is facilitated by the Bayesian optimization

process, as depicted in Equation 5:

In such models, the mean function

) is typically set to zero, and the covariance

function

is often selected as either a radial basis

function (RBF) kernel or a Matern kernel, as illustrated in Equation 6:

The posterior distribution of the Gaussian process is to be updated by the observed test data

, as demonstrated in Equation 7:

It is evident that within the given set of equations, Equations 8 and 9 are of particular significance:

In this context,

denotes the covariance vector between the new point

and the observed point

,

signifies the covariance matrix between the observed points, and

designates the vector of observations. The selection of the subsequent test point

is contingent upon the formulation of a hybrid acquisition function,

, which amalgamates the anticipated enhancement with the characteristics extracted by means of deep learning, as delineated in Equation 10:

In this study, the weight coefficient is denoted by

and

defined as Equation 11:

The current best observation is denoted by

, whilst

is the feature representation extracted by the deep neural network with a parameter of

. The selection of

is to maximize

, as outlined in Equation 12:

This step involves the implementation of an adaptive adjustment to the experimental design, integrating the uncertainty quantification capabilities of Bayesian optimization with the feature extraction capacity of deep learning. The objective of this integration is to facilitate the selection of the optimal experimental parameters in real time. The proposed gradient Bayesian optimization drastically decreases the evaluation cost for positive log-likelihood optimization without increasing computational cost. The second is at multithreading, in which a multithreading level can shorten the model's training time by making parallelization in a multicores processor or distributed computing environment.

3.2. Multi-Task Learning

The focus of clinical trials is twofold: efficacy and safety, as well as cost-effectiveness. In order to optimize these objectives simultaneously, a Multi-Task Learning (MTL) framework is adopted. The framework incorporates

objective functions, denoted by

, with each function corresponding to a specific task. The loss function for multi-task learning is defined as the weighted sum of the losses of each task, as shown in Equation 13:

In the context of machine learning, the term 'weight' is used to denote the importance or relative significance of each task in the training process. The term 'loss function' refers to the measure of deviation between the predicted and actual values, which is typically minimized through the process of training. The term 'mean square error' (MSE) or 'cross-entropy loss' is a metric used to quantify the deviation between the predicted and actual values, and is often employed in machine learning algorithms. The term 'true value' refers to the correct value or output that is sought to be achieved by the model. The model's capacity to share information between different tasks is enabled by the sharing of the hidden layer parameters of the neural network, thereby enhancing the overall optimization effect.

The weight of each task,

is hereby indicated,

is the loss function of the

-th task, and the mean square error (MSE) or cross-entropy loss is generally employed.

is the true value corresponding to L. The model's capacity to share information between different tasks, thereby enhancing the overall optimization effect, is enabled by the sharing of the hidden layer parameters of the neural network. In order to enhance the robustness of the model and prevent overfitting, an ensemble approach and regularization techniques are employed. The ensemble approach involves the training of multiple independent deep neural network models and the subsequent averaging or weighting of their predictions, as illustrated in Equation 14:

where the number of ensemble models is denoted by

, and the prediction result of the

-th submodel is indicated by

. This approach enhances the reliability and precision of predictions by mitigating the bias inherent in a single model. In the context of regularization techniques, L2 regularization terms are incorporated into the loss function with the objective of constraining the magnitude of model parameters and averting overfitting, as illustrated in Equation 15:

Furthermore, the regularization coefficient , the total number of model parameters , and the -th parameter are considered. In addition, the Early Stopping strategy is employed to halt the training process when the performance on the validation set no longer improves, thereby further preventing the model from overfitting. To improve the stability and reliability of the model, the use of cross-validation techniques can help evaluate the performance of different combinations of hyperparameters and ensure that the model performs consistently across different datasets and tasks. There are uncertainties in the process of hyperparameter optimization, and an automated hyperparameter tuning tool is introduced to further reduce the influence of human factors.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

The Molecular Taxonomy of Breast Cancer International Consortium (METABRIC) dataset was selected for its comprehensive collection of clinical information and genomic data from over 2000 breast cancer patients. This dataset offers a wealth of detailed molecular characteristics, treatment responses, and survival data for HER2-positive patients, making it a valuable resource for research in this field. The dataset's comprehensive nature and extensive follow-up duration render it an optimal research foundation, as it reflects the intricate clinical circumstances of patients with breast cancer.

4.2. Experimental Analysis

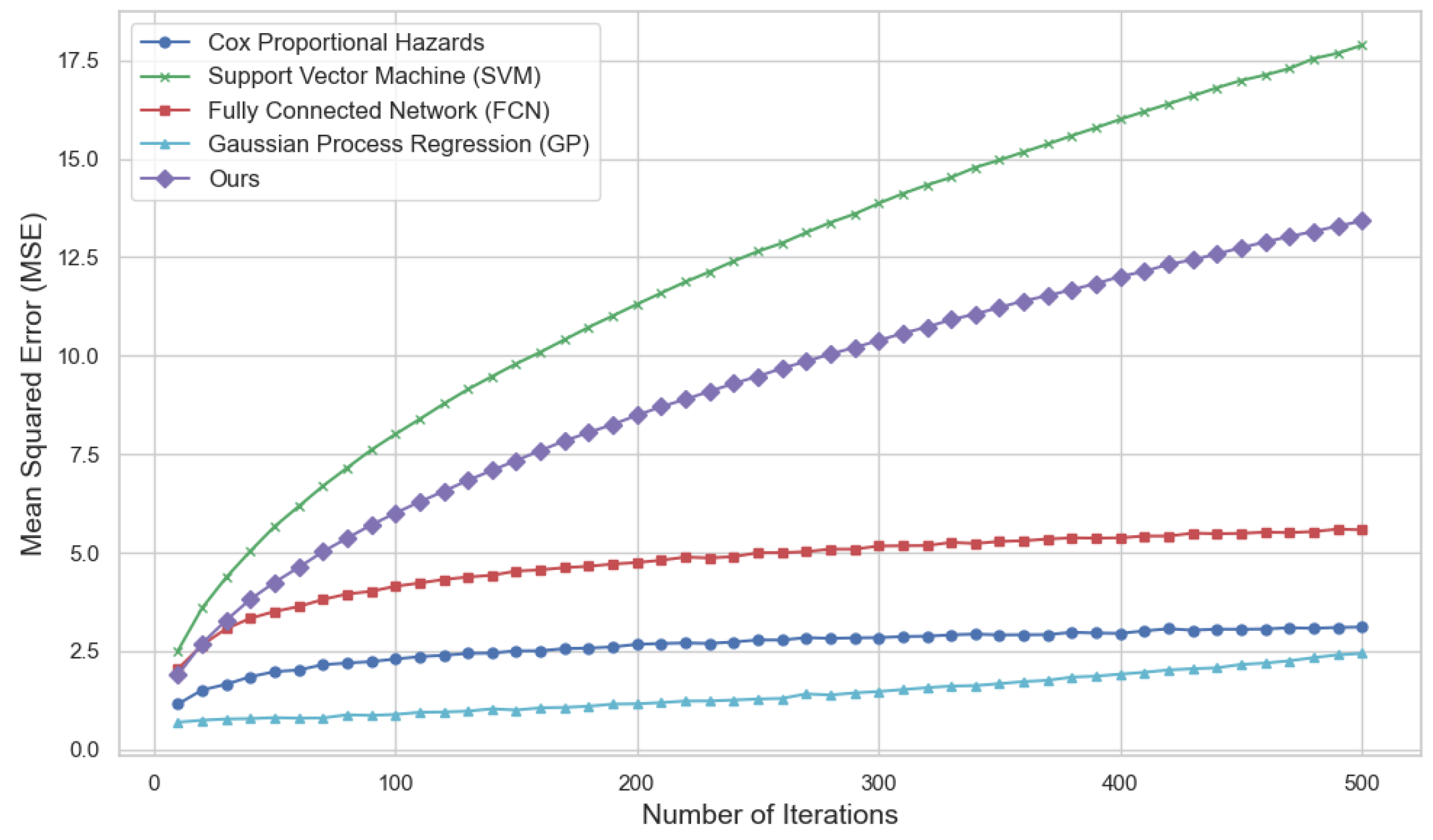

To assess the proposed Bayesian optimization and deep learning-based anti-HER2 drug clinical trial strategy optimization model, we compared it with four mainstream methods including the Cox proportional hazards model, support vector machine (SVM), fully connected neural network (FCN) and Gaussian process regression (GP). Mean square error was utilized as the major evaluation metric to determine the prediction accuracy of various methods. The hypothesis was that the lower the MSE, a higher accuracy in predictions by the model. A comparative analysis was carried out on the Cox proportional hazards model, support vector machine, fully connected neural network, Gaussian process regression, and the proposed method (Ours).

As observed from

Figure 1, MSE of Ours was always the lowest among the different methods through subsequent iterations. In contrast, the MSE of other methods, including Cox model, SVM, FCN and GP, showed a significant upward trend with the increase of iterations. This finding demonstrates how unpredictable these methods are when faced with complex clinical data, especially when analyzing large-scale datasets, and highlights a severe loss of predictive performance. Differently, the proposed model guarantees low error through the optimization of the process of algorithm and training, and testifies its efficient ability in high-dimensional and complicated data conditions.

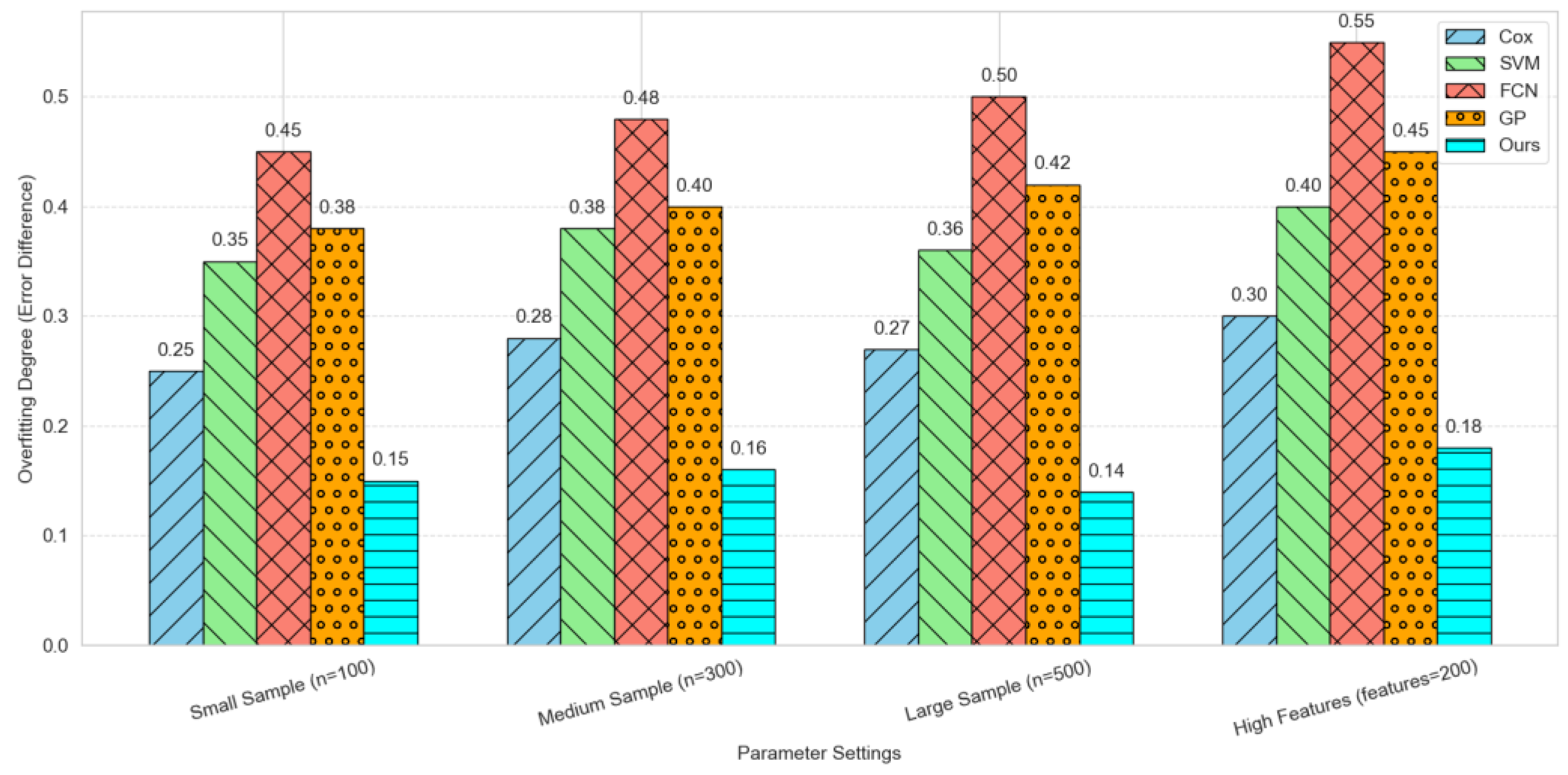

The discrepancy between the training error and the validation error was Utilized as the primary metric for evaluating the degree of overfitting, with the objective of ascertaining the presence of overfitting in the model training process.

Specifically, a comparison was made between four traditional and advanced machine learning methods (Cox proportional hazards model, support vector machine, fully connected neural network, and Gaussian process regression) and our proposed method for the degree of overfitting under four specific parameter settings: small sample size (n=100), medium sample size (n=300), large sample size (n=500), and high feature dimension (features=200). As illustrated in

Figure 2, the results are presented in the form of a histogram, with each column distinguished not only by a distinct color, but also by a unique pattern. Under all parameter settings, the degree of overfitting of the Ours method was significantly lower than that of other methods, showing superior generalization ability and stability.

5. Conclusion

In conclusion, the integration of Bayesian optimization and deep learning has demonstrated notable advantages in the optimization of clinical trial strategies for anti-HER2 drugs. The efficacy of this approach is evidenced by its ability to enhance the accuracy and efficiency of experimental design, whilst concurrently ensuring the reliability and validity of the model in practical applications through multi-objective optimization and overfitting control. The experimental results obtained verify the strong ability of the framework in processing complex high-dimensional clinical data, and it is evident that there is a wide range of application prospects and potential clinical value. Future research will further refine this approach and explore its application in clinical trials of other targeted therapy drugs, with the ultimate aim of promoting the development of precision medicine and providing cancer patients with more efficient and personalized treatment options.

References

- Xu, C.; Chen, Z.; Xia, Y.; Shi, Y.; Fu, P.; Chen, Y.; Wang, X.; Zhang, L.; Li, H.; Chen, W.; et al. Clinical best practices in interdisciplinary management of human epidermal growth factor receptor 2 antibody-drug conjugates–induced interstitial lung disease/pneumonitis: An expert consensus in China. Cancer 2024, 130, 3054–3066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pous, A.; Notario, L.; Hierro, C.; Layos, L.; Bugés, C. HER2-Positive Gastric Cancer: The Role of Immunotherapy and Novel Therapeutic Strategies. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 11403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrando-Díez, A.; Felip, E.; Pous, A.; Sirven, M.B.; Margelí, M. Targeted Therapeutic Options and Future Perspectives for HER2-Positive Breast Cancer. Cancers 2022, 14, 3305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhide, G.P.; Colley, K.J. Sialylation of N-glycans: mechanism, cellular compartmentalization and function. Histochem. 2016, 147, 149–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ghoshal, U.C.; Ghoshal, U.; Mathur, A.; Singh, R.K.; Nath, A.; Garg, A.; Singh, D.; Singh, S.; Singh, J.; Pandey, A.; et al. The Spectrum of Gastrointestinal Symptoms in Patients With Coronavirus Disease-19: Predictors, Relationship With Disease Severity, and Outcome. Clin. Transl. Gastroenterol. 2020, 11, e00259. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Passaro, A.; Jänne, P.A.; Peters, S. Antibody-Drug Conjugates in Lung Cancer: Recent Advances and Implementing Strategies. J. Clin. Oncol. 2023, 41, 3747–3761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fucà, G.; Fucà, G.; Sabatucci, I.; Sabatucci, I.; Paderno, M.; Paderno, M.; Lorusso, D.; Lorusso, D. The clinical landscape of antibody-drug conjugates in endometrial cancer. Int. J. Gynecol. Cancer 2024, 34, 1795–1804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wynn, C.S.; Tang, S.-C. Anti-HER2 therapy in metastatic breast cancer: many choices and future directions. Cancer Metastasis Rev. 2022, 41, 193–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liao, Michael Z., et al. "Model-Informed Therapeutic Dose Optimization Strategies for Antibody–Drug Conjugates in Oncology: What Can We Learn From US Food and Drug Administration–Approved Antibody–Drug Conjugates?." Clinical Pharmacology & Therapeutics 110.5 (2021): 1216-1230.

- Xing, M.; Li, Z.; Cui, Y.; He, M.; Xing, Y.; Yang, L.; Liu, Z.; Luo, L.; Wang, H.; Guo, R. Antibody–drug conjugates for breast cancer: a bibliometric study and clinical trial analysis. Discov. Oncol. 2024, 15, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yoon, Jeesun, and Do-Youn Oh. "HER2-targeted therapies beyond breast cancer—An update." Nature Reviews Clinical Oncology 21.9 (2024): 675-700.

- Bian, Li, Feng Li, and Zefei Jiang. "Thoughts on therapy strategy in the era of “after anti-HER2 TKI” in CSCO BC Guidelines 2022." Translational Breast Cancer Research 3 (2022).

- Tarantino, Paolo, et al. "Optimizing the safety of antibody–drug conjugates for patients with solid tumors." Nature reviews Clinical oncology 20.8 (2023): 558-576.

- Chen, Jiexiao, Ziyang Xie, and Jianke Zou. "Research on Personalized Teaching Strategies Selection based on Deep Learning." Proceedings of the 2024 4th International Conference on Internet Technology and Educational Informatization (ITEI 2024).. Springer Nature, 2024.

- Wang, H.; Li, J.; Li, Z. AI-generated text detection and classification based on BERT deep learning algorithm. Theor. Nat. Sci. 2024, 39, 187–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).