1. Introduction

The International Association for the Study of Pain defines pain as a "painful experience that is both physical and mental, associated with or resembling tissue damage" [

1]. Inadequately controlled acute pain following trauma may lead to prolonged hospitalization, high rates of readmission into healthcare facilities, increased cost of care and a poor quality of life. Most patients experience moderate to severe pain despite treatment while admitted to hospital, and on treatment [

2]. Factors that influence pain perception and the effectiveness of analgesic drugs with or without other modalities of treatment include sex, age and the mental state of a patient, and smoking [

3,

4]. Co-morbid conditions such as human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and other viral infections, hypertension, diabetes mellitus and may also influence the perception of pain and response to analgesia [

5,

6,

7,

8]. Patients with HIV infection, particularly when CD4+ T-lymphocytes count is low may have a reduced threshold and heighten perception of pain [

5]. On the other hand, hypertension may blunt nociception, a phenomenon called as "hypertension-related hypoalgesia [

5,

6,

7].

Most guidelines on management of pain, including acute pain following trauma recommend a multidisciplinary team approach, which should preferably include a combination of pharmacological treatment and non-pharmacological strategies [

9,

10]. The World Health Organization (WHO) analgesic ladder (pain ladder) was originally developed to guide management of pain in patients with cancer but is also useful for treatment of acute pain following trauma [

11]. A stepwise approach to the management of acute pain based on the severity of pain, drug availability and patient condition is recommended [

12]. Adjuvant treatment including anti-depressants may be added in patients with severe acute pain [

11,

12].

Management of pain in low- and middle-income including South Africa remains suboptimal despite the existence of treatment guidelines with sometimes up to 70% of patients experience moderate-to-severe pain following surgical intervention while receiving analgesia [

13,

14,

15]. Reasons for inadequate pain control include among others under-estimation of the severity of pain, knowledge gaps among attending healthcare workers, misconceptions by patients and/or attending health care practitioners, shortage of resources and fear of side-effects, especially of opioids [

16]. Implementation of pain assessment protocols, ongoing evaluation of the adequacy of pain control, interdisciplinary and multimodal analgesia improves the quality of management of pain. Multi-modal analgesia strategies for management of acute pain following trauma include the use of nerve blocks and patient-controlled analgesia, and non-pharmacological strategies [

15,

16].

Inadequately controlled pain predisposes to complications among them venous thrombo-embolism and hypostatic pneumonia, which at may lead to a delayed recovery and prolonged hospital stay [

17]. Furthermore, persistent pain may necessitate prolonged use of opioid analgesics, with their associated risk of depression and addiction; further delaying or hindering a patient’s recovery [

3]. Chronic opioids use, or abuse alters neural pathways in the brain and may result in tolerance, hyperalgesia or allodynia [

18]. Substance abuse or addiction can be quantified by using the Drugs Abuse Screening Test-10 (DAST-10). However, the multifactorial nature of pain makes accurate quantification of pain experience in individuals abusing or addicted to substances difficult.

Although several unidimensional and multidimensional pain scales have been developed for use to evaluate pain intensity and response to treatment, but multidimensional pain assessment scales are preferred as they offer a more comprehensive analysis of pain and its consequences. The two most commonly used multidimensional models are the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ9) and Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7 (GAD-7) scales [

19,

20]. The above-mentioned pain assessment scales provide an overall evaluation of a patient’s experience after physical trauma, including his or her mental status, prevailing mood and sleep patterns [

20]. The PHQ-9 scale measures the severity of depression in response to treatment whereas the GAD-7 is a screening tool for existence of anxiety disorders [

19,

20].

Simpler unidimensional scales like the Numerical Rating Scale (NRS) are useful, especially in resource-limited settings [

21]. The NRS is linear scale and ranks pain from 0 to 10. An NRS score of 0 indicates no pain, 1-3 mild, 4-6 moderate, 7-9 severe and 10 the worst pain a patient has ever experienced [

21]. As per widely accepted principles of analgesia, an NRS score below or equal to 4 following administration of analgesics is considered adequate pain management [

22]. Although the pain rating scales are subjective, they provide valuable insight into the intensity of pain [

23]. Combining trauma severity scores, like the Trauma and Injury Severity Score (TRISS), with any of the pain scales can augment the evaluation of severity of injury and prediction of outcomes [

24,

25].

Pain is considered the 5

th vital sign which requires regular monitoring for appropriate control [

26]

. Ideally, no patient must experience pain while in hospital [

27]. Regular review of a patient following initiation of management strategies may lead to escalation or de-escalation of treatment [

28]. The pain management index (PMI) is commonly used for assessment of the efficacy and efficiency of pain management strategies [

29]. The PMI is calculated by subtracting the score of the severity of pain from the highest category of analgesic drugs used as per the WHO analgesic ladder [

29,

30]

. The scores for the severity of pain range from 0 for no pain, 1 for mild pain, 2 for moderate pain and 3 for severe or worst pain ever imagined. The weighting for no analgesic used is 0, acetaminophen or non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDS) 1, weak opioids 2 and strong opioids 3 [

30].

Addressing barriers to pain management and complications to pain management could result in better patient outcomes. A study conducted at a hospital in Taiwan showed a significant reduction of pain experienced by patients through involvement of a multidisciplinary team, a real-time response cycle, an evidence-based education program and teamwork [

1]. Adopting similar strategies at hospitals in South Africa may lead to more efficient management of acute pain and improve the overall quality of care of trauma patients [

31]. This study investigated how effectively pain is managed in patients admitted to a Level 1 Trauma Unit at a tertiary academic hospital in the Gauteng Province of South Africa. This cross-sectional study has been reported in line with the STROCSS guidelines [

32].

2. Materials and Methods

Ethical clearance was obtained from the Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) of University of the Witwatersrand (M231036 MED23-10-26) before commencement of the study. Participants were patients admitted following trauma and were more than 36 hours following admission. A standardized information sheets was provided to all participants explicitly highlighting the aim, objectives, methodology and procedures involved in the research. A comprehensive consent form was signed by all participants, which emphasized their right to discontinue their participation in the study at any time. Additionally, confidentiality of patient information was emphasized and transparency on the part of the researchers was maintained throughout the study. A Distress Protocol was followed in the events of emotional distress and discomfort of participants during interviews, and psychologists from the local Department of Psychology were available for consultation if needed.

This was a cross-sectional observational quantitative study and participants were patients admitted following traumatic injury to the Trauma Division of Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital (CMJAH). The CMJAH is a 1088-bed central academic hospital in Johannesburg, South Africa. The hospital is part of the public healthcare service in Gauteng Province, and is an accredited Level 1 Trauma that receives patients directly from the scene of accident or referred from lower level hospitals. Using a conservative proportion, the sample size for this study was estimated at 387 participants, with a 95% confidence interval (CI), alpha of 5% and margin of error of 5%. The study was conducted as part of mandatory promotional requirement for Medical Students of University of the Witwatersrand during their 4th and 5th Year of study. Because of a delay in obtaining ethics clearance the number could not be reached. Data collection could not continue after presentation of interim results for fear of the “Hawthorne effect”.

Participants were aged 18 years or older with a Glasgow Coma Scale (GCS) of 15/15. Patients who reported no pain were excluded during further analysis. Patients admitted as transfers from other hospitals were excluded. We also excluded patients with a history of analgesics use unrelated to the trauma event within the past seven days. Patients who participated in the pilot study were also excluded. The patients were recruited via convenience sampling and provided written consent. Data were obtained following a standardized interview of participants and review of the patient files. Data were captured using Research Electronic Data Capture (REDCap), which is a secure web-based interface for creating and handling electronic databases and surveys. Data captured included race, sex, age and history of hypertension, diabetes mellitus and human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Information on mechanism of injury and the trauma severity (TRISS) score was also collected. The severity of pain experienced on admission and pain level at the time of the interview (NRS score), time since admission, and analgesia used and dosages, frequency and the route of administration. The PHQ9, GAD7 and DAST-10 assessment tools were used for screening for risk of depression, anxiety and, substance abuse and addiction, respectively.

The REDCap was used during calculation of the data, using its automated export procedures to Excel and Stata. The NRS scores were as indicated previously categorized into Category A (pain free: 0), Category B (mild pain: 1-3), Category C (moderate pain: 4-6), Category D (severe pain: 7-9) and Category E (worst pain imaginable: 10). Additionally, pain scores during admission were compared to pain scores at the time of the interviews. Categorical data were summarized by using proportions, frequencies and/or percentages. The chi-squared test and the Fisher exact test were used to test for associations between independent and dependent categorical variables. The independent variables were the participant’s demographic characteristics and comorbidities and the dependent variable was the participant’s perception of pain. A p-value of <0.05 was considered statistically significant. We utilized the Cronbach's Alpha test to determine the internal consistency and reliability of the Likert scales. For assessing validity, we explored both construct and criterion validity. We used a Likert scale to allow for a range of responses rather than a yes/no response to complex lived experiences.

3. Results

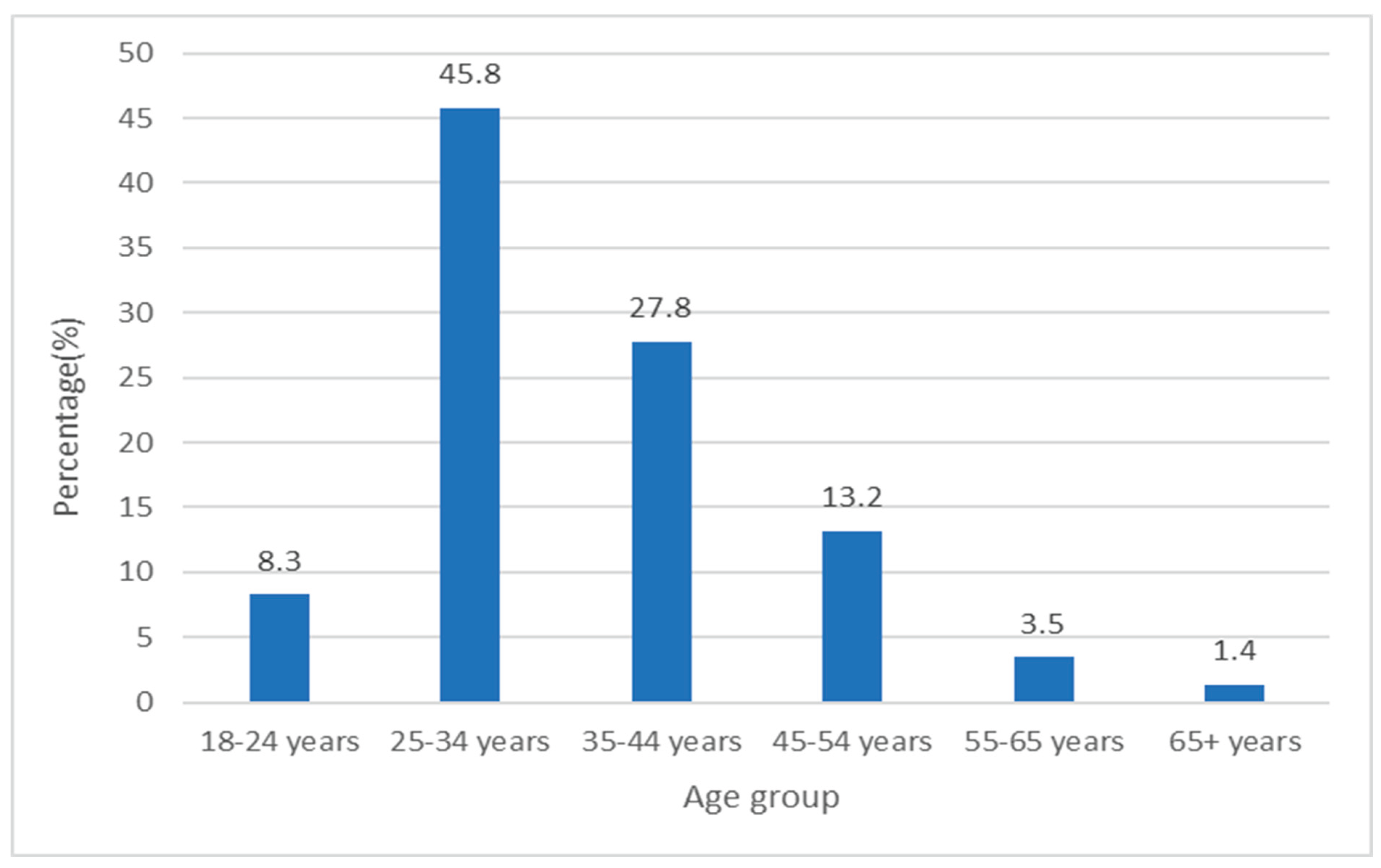

Hundred and forty-three patients participated, 81.1% (116) of whom were male and 18.9% (27) female. The age distribution of participants was stratified into six categories with majority of the participants in the 25 to 34- and 35 to 44-year age groups at 45.8% and 27.8%, respectively (

Figure 1).

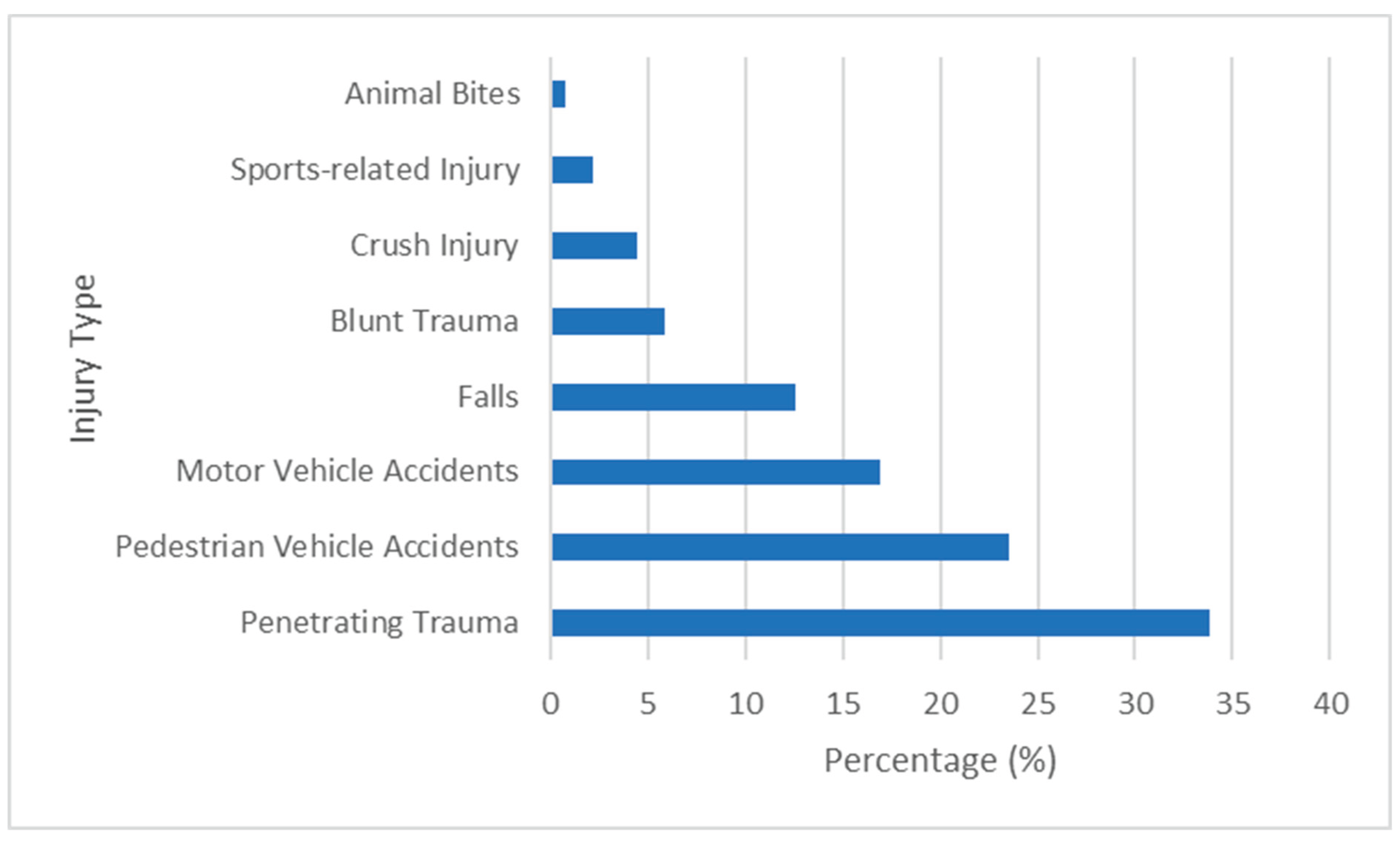

Majority, 92.3% of participants were black African whereas 3.5% were white, 2.1% mixed race and 2.1% Indian. Mechanisms of injury included penetrating trauma in 33.9% and pedestrian-vehicle accidents in 23.6% (

Figure 2).

Comorbidities included 3.5% each for DM and hypertension, and 21.1% were HIV positive. Close to 44.1% of the participants experienced moderate pain while 31.5% had mild pain (NRS 1–3) (

Table 1).

Level of anxiety was moderate or severe in 11.9% of the participants and, 3.6% showed evidence of moderate to severe depression and 21.8% disclosed history that was moderate to severely concerning of addiction to substances (

Table 2).

Five (3.5%) participants each had hypertension and DM. Thirty (21%) of participants tested positive for HIV. Eleven (36.7%) HIV-positive participants reported mild, 43.3% (n=13) moderate, 13.3% (n=4) severe and 6.7% (n=2) worst imaginable pain on admission. However, HIV status had no statistically significant influence on pain perception and the effectiveness of analgesic drugs. Among 17 participants with moderate or severe anxiety, 11.8% (n=2) experienced severe pain compared to 6.7% (n=1) of 15 with depression and 3.2% (n=1) of 31 with history of drug abuse (

Table 3).

Tramadol plus pethidine and paracetamol plus tramadol were two most commonly used analgesic options in participants who reported mild pain during the interview, whereas paracetamol plus tramadol was prescribed for majority who had moderate pain. The remaining participants received pethidine plus one of the NSAIDs, paracetamol plus pethidine, paracetamol pus tramadol and morphine. A combination of paracetamol and tramadol was prescribed to 78.6% of participants with severe pain. Other drug combinations included pethidine plus NSAIDs, tramadol and codeine phosphate, paracetamol with NSAIDs and, paracetamol together with paracetamol and pethidine. The PMI was lower in participants with severe or worst imaginable pain (

Table 4).

Participants with mild or no pain (NRS: 0–3) were considered adequately managed, representing 37.1% (n=53). Participants reporting moderate, severe, or the worst imaginable pain (NRS: 4–10) were considered inadequately managed, comprising 62.9% (n=70) of the participants. Among participants reporting moderate to severe anxiety (GAD-7 score ≥ 10), 64.7% experienced moderate pain, 17.6% mild pain and 11.8% severe pain. One participant reported no pain (5.9%). In contrast, 59.8% of patients with no or low anxiety risk (GAD-7 score from 0-4 reported moderate pain. Overall, among patients with low anxiety risk score of 5-9), 58.3% had inadequate pain relief; this further increased to 81.8% for those with moderate risk (score 10-14) and 100% for those with severe anxiety cases (score 15-21). The difference in the rates of inadequate pain control at different levels of anxiety was however not statistically significant (p=0.119).

Participants with moderate to severe depression (PHQ-9 score ≥ 10) reported moderate pain (53.3%), followed by mild pain (33.3%) and severe pain (6.7%). One participant reported no pain (6.7%). In comparison, 59.4% of patients with no or minimal depression (PHQ-9 score 0-4) received inadequate pain management, and this percentage increased to 75% for those with mild depression (score 5-9), 90% for moderate depression (score 10-14), and 75% for patients with moderate to severe depression (score 15-19). All patients with severe depression (score 20-27) experienced inadequate pain relief. The influence of levels of depression on adequacy of pain control was however not statistically significant (p= 0.168).

Among the 103 participants with no history of substance abuse, 66% experienced inadequate pain management. In the low-level drug abuse group (DAST-10 score 1-2), 62.5% of patients had inadequate pain management. For participants with moderate level of drug abuse (score 3-5), 59.1% reported inadequate pain relief, while in the substantial drug abuse group (score 6-8), only 37.5% were inadequately managed. Interestingly, in one participant with severe drug abuse (score 9-10) pain management was adequate. The difference in the relationship between levels of drug abuse and adequacy of pain management was also not statistically significant (p=0.408).

4. Discussion

Patient must never experience pain while in hospital and receiving analgesic treatment [

27]. This study investigated effectiveness of pharmacotherapy in the management of acute pain in patients admitted following trauma. The main findings include that majority of patients admitted were men and had sustained penetrating trauma or pedestrian vehicle accident, and 21% were HIV positive and 76% had either mild or moderate pain on admission. Paracetamol with or without tramadol was the most preferred analgesic option regardless of the severity of pain and majority of patients still experience moderate to severe pain despite treatment.

Most participants were Black African males, predominantly aged between 25 and 44 years. This reflects the racial distribution of the South African population, in which black Africans make up 81.4% of the population (Department of Statistics South Africa, 2023). The racial distribution of the participants at CMJAH also aligns with that of the racial differences in South African public healthcare acquisition, which has been found to be: 81% black Africans, 10% Caucasian, 7% mixed race, and 2% Indians [

33]. The predominance of young (25 to 34 years old) participants is in keeping with other South African studies in which young adults (<40 years of age) are the most commonly involved in trauma [

31]. Similarly, the predominance of male participants is in line with literature in which trauma commonly involves men [

34].

While studies such as those by Makovac et al. and Diaz et al. highlight the significant influence of pre-existing comorbidities on pain sensitivity and perception [

6,

8], our study found no statistically significant associations between pain perception and comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, or HIV. This lack of significant association between the level pain perception or control and HPT or DM may be attributable to the predominance of young patients with fewer comorbidities in the current study. The above could have limited our ability to detect meaningful differences in pain reduction associated with these conditions. The prevalence of comorbidities except for HIV increases with increasing age [

35].

As noted in other research, patients with anxiety have more severe pain experiences [

3,

4]. Further, evidence reflects that 48% of people living on the African continent experience some level of anxiety in a post-pandemic world [

36]. When evaluating this research against the current study, anxiety levels were far less in our population (28.7%) as compared to the continental norm of 71.3% of participants experiencing no to low levels of anxiety. This data may be because of the nature of the GAD-7 survey used. This questionnaire poses questions over a 14-day period, whilst many of our patients had prolonged hospital stays. During their prolonged stays, anxiety symptoms may have subsided. Regarding anxiety levels and pain experience, there appeared to be a trend in which an elevated anxiety level corresponded with a higher NRS score. Among participants with moderate to severe anxiety (GAD-7 score ≥ 10), majority experienced moderate pain (64.7%) In contrast, patients with no or low anxiety risk (GAD-7 score 0-4) had 59.8% receiving inadequate pain relief. However, there was no statistically significant association between anxiety severity and pain relief. This indicates that anxiety levels did not significantly impact pain management outcomes, likely due to the small number of patients with higher anxiety levels.

Depression worsens the experience of pain [

3,

4]. Our study revealed that 59.4% of patients with no to minimal depression (PHQ-9 score 0-4) had inadequate pain control. In mild depression (score 5-9), 75% of patients had inadequate pain relief, increasing to 90% in those with moderate depression (score 10-14). For those with moderate to severe depression (score 15-19), 75% were inadequately managed, and for severe depression (score 20-27), 100% of patients experienced inadequate pain relief. Like with anxiety, the lack of statistical significance could be due to the small number of patients with higher depression severity. Patients struggling with addiction may be inadequately treated for acute pain [

18]. Interestingly, our results revealed that with increasing levels of issues relating to substance abuse there was a reduction in the number of patients who were inadequately managed suggesting that patients with higher degrees of substance abuse had no to mild pain upon assessment of their pain levels. These results however were deemed statistically insignificant, suggesting that substance abuse levels did not significantly influence the adequacy of pain management. This could have been due to the small number of patients with higher levels of substance abuse.

Mild pain is managed with non-opioid agents, such as NSAIDS [

11]. In our study tramadol with paracetamol was the most preferred analgesic combination regardless of the severity of pain. Majority of patients with mild pain on admission were prescribed tramadol and pethidine. For moderate pain, the WHO pain ladder recommends the use of weak opioids like tramadol with or without non-opioid analgesics and with or without adjuvants [

11]. Although half of the patients with moderate pain were appropriately managed with paracetamol and tramadol, the remainder received inappropriate analgesic combinations including strong opioids like pethidine and morphine. Although severe pain should be managed with strong opioids with or without non-opioids, and with or without adjuvants, majority of our patients had a weak opioid (tramadol) and a non-opioid analgesic drug like paracetamol [

11]. Furthermore, some of the patients with severe pain were not according to guidelines only prescribed non-opioid agents like paracetamol and NSAIDs) [

11]. The study showed that the WHO pain ladder was not always appropriately utilized. This highlights the lack of individualized analgesia, with poor consideration for pain experienced. The preferred analgesic management at this hospital, regardless of pain severity, is the combination of paracetamol and tramadol. Furthermore, the WHO pain ladder recommends against the use of multiple opioids [

11]. Despite this, many participants received two opioids simultaneously.

Misunderstanding, limited availability of drugs and alternative treatment options guidelines and fear of side-effects may explain why in majority of the patients, pain was not effectively managed [

16]. Our results however mirror findings from studies in other regions of the world, that pain is not effectively managed [

37,

38,

39]. Patients experiencing severe pain are frequently prescribed non-opioids or weak opioids for fear of side effects or induction of addiction [

16]). Unfortunately, the side-effects and addictive potential of weak opioids are not markedly different from those of strong opioids [

40]. Furthermore, analgesic prescription is often started with lower level drugs and only escalated in some patients following complaints instead of initiating treatment with stronger opioids and deescalating when the inflammatory process has abated, which require regular review of patients the effectiveness of treatment [

27,

41,

42,

43]. Regular review with escalation or de-escalation of treatment or addition of adjunctive treatment is a pre-requisite for effective management of acute pain, especially in patients admitted following trauma or following surgery [

28,

38].

The study had several limitations. The calculated sample size was 387 patients but only 143 were interviewed, this was in part from the extended wait times for surgical interventions that resulted in patients occupying beds for prolonged periods. The patient population was interviewed at one tertiary academic hospital in Gauteng, this also likely contributed to an inability to meet the sample size. A single center study also likely contributes to a similar patient demographic and the applicability of the study in other settings may be limited. Whilst interviewing patients, the diverse cultural backgrounds of patients at CMJAH meant that at times, language was a barrier to communication during interviews, particularly with foreign nationals. A language barrier coupled with the subjective nature of pain, meant that an objective comparison of pain reduction, despite the existence of the NRS scale, was difficult to adequately quantify. Furthermore, a generic use of the term “pain” in this study, accounts only for the physical sensation of pain and not psychological dimensions of pain.

Whilst an element of the psychological status of patients was evaluated, further in-depth research needs to be conducted to investigate the contribution of psychological status to adult trauma patients' pain experiences. In relation to the other comorbidities included within the study, many were included because of their prevalence within a South African context. A more comprehensive list would have aided in making this study being replicable in other settings but also include a broader understanding of contributors to pain within the current study itself. Participants were only interviewed once, the time since the last dose of analgesics was not studied. However, a patient must not experience pain anytime while in hospital regardless and on treatment. Finally, only pharmacological treatment was evaluated and other management strategies such as physiotherapy and psychotherapy were not evaluated, and effectiveness of pain treatment was therefore only attributed to pharmacological agents. Future studies should incorporate the effects of non-pharmacological methods in the management of pain.

5. Conclusions

This cross-sectional study of 143 participants at Charlotte Maxeke Academic Hospital in Gauteng mostly consisted of young (45.8% at 25-34 years of age) black (92.3%) males (81.1%) with no comorbidities (74.8%), with the most common mechanism of injury being penetrating trauma (33.9%). It was found that, overall, pain was inadequately managed, with 62.9% of all patients experiencing moderate to severe pain after receiving analgesia. In all levels of pain severity on admission, there was inappropriate analgesic escalation in accordance with the WHO pain ladder, highlighting the lack of individualistic analgesic tailoring. The preferred analgesic option was a combination of Tramadol and Paracetamol, regardless of the severity of pain. Furthermore, no statistically significant relationship was identified between inadequate pain management and comorbidities such as hypertension, diabetes, HIV as well as psychological factors such as anxiety, depression, nor substance abuse. This lack of significant findings may be attributable to the predominance of participants without these factors in our sample, which could have limited our ability to detect meaningful differences in pain reduction associated with these conditions.

Adhering to the WHO Pain Ladder is crucial for ensuring appropriate analgesic use tailored to individual pain severity, with a focus on appropriate escalation of treatment. To enhance this adherence, it is essential to improve pain assessment protocols by implementing standardized assessments and conducting regular pain re-assessments. The individualization of pain management is strongly recommended. Additionally, training healthcare providers on best practices in pain management, grounded in the WHO guidelines, is vital for fostering effective care. Additionally, further research into the potential barriers that are hindering effective adherence to the WHO pain ladder, which may include financial or availability constraints, is needed to identify and address these reasons for non-adherence. Special attention should be given to the influence of comorbidities, psychological factors, and substance abuse on pain perception, as these may require more individualized management strategies to optimize patient outcomes.

Author Contributions

“Conceptualization, S.V.D.S, P.D, S.L, Z.M, T.M, M.N, A.P and T.E.L; methodology, S.V.D.S, P.D, S.L, Z.M, T.M, M.N, A.P and T.E.L; .V.D.S, P.D, S.L, Z.M, T.M, M.N and A.P; investigation, S.V.D.S, P.D, S.L, Z.M, T.M, M.N and A.P; resources, S.V.D.S, P.D, S.L, Z.M, T.M, M.N, A.P and T.E.L; data curation, S.V.D.S, P.D, S.L, Z.M, T.M, M.N, A.P and T.E.L; writing—original draft preparation, .V.D.S and T.E.L; writing—review and editing, S.V.D.S, P.D, S.L, Z.M, T.M, M.N, A.P and T.E.L; supervision, T.E.L; project administration, S.V.D.S and T.EL. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Human Research Ethics Committee (Medical) of University of the Witwatersrand (M231036 MED23-10-26 and 27/03/2024).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

Data supporting reported results will be made available on request with prior authorization from the ethics committee.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the inputs of the team of assessors in the Unit of Undergraduate Medical Education in the Faculty of Health Sciences for the valuable inputs during the development of the protocol. We would also like to acknowledge the support from the staff in the Trauma Division and Department of Psychology at CMJAH for providing guidance and support during data collection.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| HIV |

Human immunodeficiency virus. |

| NRS |

Numeric Rating Scale. |

| WHO |

World Health Organization. |

| DAST-10 |

Drugs Abuse Screening Test-10. |

| PHQ9 |

Patient Health Questionnaire 9. |

| GAD-7 |

Generalized Anxiety Disorder-7. |

| TRISS |

Trauma Injury Severity Score. |

| PMI |

Pain Management Index. |

| STROCSS |

Strengthening the reporting of cohort, cross-sectional, and case control studies. |

| CMJAH |

Charlotte Maxeke Johannesburg Academic Hospital. |

| CI |

Confidence interval. |

| GCS |

Glasgow Coma Scale. |

| REDCap |

Research Electronic Data Capture. |

References

- Chen, M.C., Yeh, T.F., Wu, C.C., Wang, Y.R., Wu, C.L., Chen, R.L., Shen, C.H. Three-year hospital-wide pain management system implementation at a tertiary medical center: Pain prevalence analysis. PLOS ONE 2023, 18(4), e0283520. [CrossRef]

- Raja, S.N., Carr, D.B., Cohen, M., Finnerup, N.B., Flor, H., Gibson, S., Keefe, F., Mogil, J.S., Ringkamp, M., Sluka, K.A., Song, X.J. The revised IASP definition of pain: Concepts, challenges, and compromises. Pain 2020, 161(9), 1976-1982. [CrossRef]

- Michaelides, A and Zis, P. Depression, anxiety, and acute pain: links and management challenges. Postgraduate Medicine 2019, 131(7), 438-444. [CrossRef]

- Parker, R., Stein, D.J., Jelsma, J. Pain in people living with HIV/AIDS: a systematic review. Journal of the International AIDS Society 2014, 17(1), 18719. [CrossRef]

- Makovac, E., Porciello, G., Palomba, D., Basile, B., Ottaviani, C. Blood pressure-related hypoalgesia: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Hypertension 2020, 38(8), 1420-1435. [CrossRef]

- Sacco, M., Meschi, M., Regolisti, G., Detrenis, S., Bianchi, L., Bertorelli, M., Pioli, S., Magnano, A., Spagnoli, F., Giuri, P.G. and Fiaccadori, E. The relationship between blood pressure and pain. The Journal of Clinical Hypertension (Greenwich) 2013, 15(8), 600-605. [CrossRef]

- Diaz, M.M., Caylor, J., Strigo, I., Lerman, I., Henry, B., Lopez, E., Wallace, M.S., Ellis, R.J., Simmons, A.N., Keltner, J.R. Toward composite pain biomarkers of neuropathic pain—focus on peripheral neuropathic pain. Frontiers in Pain Research 2022, 3, 869215. [CrossRef]

- Ras, T., 2020. Chronic non-cancer pain management in primary care. South African Family Practice, 62(3).

- Raff, M., Crosier, J., Eppel, S., Sarembock, B., Meyer, H., Webb, D. South African guideline for the use of chronic opioid therapy for chronic non-cancer pain: guideline. South African Medical Journal 2013, 104(1), 79-89. [CrossRef]

- Yang, J., Bauer, B.A., Wahner-Roedler, D.L., Chon, T.Y., Xiao, L. The Modified WHO Analgesic Ladder: Is It Appropriate for Chronic Non-Cancer Pain? Journal of Pain Research 2020, 13, 411-417. [CrossRef]

- Cuomo, A., Bimonte, S., Forte CA., Botti G., Cascella M. Multimodal approaches and tailored therapies for pain management: the trolley analgesic model. Journal of Pain Research 2019; 12: 711-714. [CrossRef]

- Hsu, JR., Mir, H., Wall, M.K., Seymour, R.B. Clinical Practice Guidelines for Pain Management in Acute Musculoskeletal Injury. Journal of Orthopedics Trauma 2019; 33(5): e158-e182. [CrossRef]

- Awolola, A.M., Campbell, L., Ross, A. Pain management in patients with long-bone fractures in a district hospital in Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa. African Journal of Primary Health and Family Medicine 2015; 7(1): 818. [CrossRef]

- Gao, L., Mu, H., Lin, Y., Wen, Q., Gao, P. Review of the Current Situation of Postoperative Pain and Causes of Inadequate Pain Management in Africa. Journal of Pain Research 2023; 16: 1767-1778. [CrossRef]

- Mushosho, T., Mpe, M., Masehla, B., Mkhwanazi, S., Mokhothu, R., Molehe, R., Masilo, K., Mshayisa, N., Mukoma, M., Nokwe, Y., Ntjana, K., Ntshamgase, N., Tambudze, K., Luvhengo, T.E. Post-Operative Analgesia: Are Patients Receiving Adequate Cover? Journal of Anesthesia & Intensive Care Medicine 2021, 11(4), 1-8. [CrossRef]

- Gao, L., Mu, H., Lin, Y., Wen, Q., Gao P. Review of the Current Situation of Postoperative Pain and Causes of Inadequate Pain Management in Africa. Journal of Pain Research 2023, 16, 1767-1778. [CrossRef]

- Vadivelu, N., Lumermann , L., Zhu , R., Kodumudi, G. Pain control in the presence of drug addiction. Curr Pain Headache Rep. 2016, 20(5), 35. [CrossRef]

- Kroenke, K., Spitzer, R.L., Williams, J.B.W. The PHQ-9. Validity of a Brief Depression Severity Measure. Journal of General Internal Medicine 2001; 16: 606-613. [CrossRef]

- Ford, J., Thomas, F., Byng, R., McCabe, R. Use of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9) in Practice: Interactions between patients and physicians. Qualitative Health Research 2020, 30(13), 2146-2159. [CrossRef]

- Villareal-Zegarra, D., Barrera-Begazo, J., Otyazu-Alfaro, S., Mayo-Puchoc, N., Bazo-Alvarez, J.C., Huarcaya-Victoria, J. Sensitivity and specificity of Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-9, PQH-8, PHQ-2) and General Anxiety Disorder scale (GAD-7, GD-2) for depression and anxiety diagnosis: a cross-sectional study in a Peruvian hospital population. BMJ Open. 2023; 13(9): e076193. [CrossRef]

- Dijkers, M. Comparing Quantification of Pain Severity by Verbal Rating and Numeric Rating Scales. Journal of Spinal Cord Medicine 2010; 33(3): 232-242. [CrossRef]

- Farrar, J.T., Pritchett, Y.L., Robinson, M., Prakash, A, Chappell, A. The Clinical Importance of Changes in the 0 to 10 Numeric Rating Scale for Worst, Least, and Average Pain Intensity: Analyses of Data from Clinical Trials of Duloxetine in Pain Disorders. The Journal of Pain 2010; 109-118. [CrossRef]

- Gabbe, B.J., Cameron, P.A., Wolfe, R. TRISS: does it get better than this? Academic Emergency Medicine 2004, 11(2), 181-186.

- Höke, M.H., Usul, E., and Özkan, S. Comparison of trauma severity scores (ISS, NISS, RTS, BIG score, and TRISS) in multiple trauma patients. Journal of Trauma Nursing| 2021, 28(2), 100-106. [CrossRef]

- Nicol, A., Knowlton, L.M., Schuurman, N., Matzopoulos, R., Zargaran, E., Cinnamon, J., Fawcett, V., Taulu, T., Hameed, S.M. Trauma Surveillance in Cape Town, South Africa. JAMA Surgery 2014, 149(6), 549. [CrossRef]

- Xiao H, Liu H, Liu J, Zuo Y, Liu L, Zhu H, Yin Y, Song L, Yang B, Li J, Ye L. Pain Prevalence and Pain Management in a, Chinese Hospital. Medical Science Monitor 2018; 24: 7809-7819.

- Bayisa G, Limenu K, Dugasa N, Regassa B, Tafese M, Abebe M, Shifera I, Fayisa D, Deressa H, Negari A, Takele A, Tilahun T. Pain-free hospital implementation: a multidimensional intervention to improve pain management at Wallaga University Referral Hospital, Nekemte, Ethiopia. BMC Research Notes 2024; 17: 28. [CrossRef]

- Vargas-Schaffer G. Is the WHO analgesic ladder still valid? Twenty-four years of experience. Can Fam Physician. 2010; 56(6): 514-517.

- Sakakibara N, Higashi T, Yamashita I, Yoshimoto T, Matoba M. Negative pain management index scores do not necessarily indicate inadequate pain management: a cross-sectional study. cBMC Palliative Care 2018; 17(1): 102. [CrossRef]

- Kejela S and Seyoum N. Acute pain management in the trauma patient population: are we doing enough? A prospective observational study. Journal of Trauma and Injury 2022; 35(3): 151-158. [CrossRef]

- Mhlanga, D., Garidzirai, R. The Influence of Racial Differences in the Demand for Healthcare in South Africa: A Case of Public Healthcare. Int J Environ Res Public Health. 2020 Jul 14;17(14):5043. [CrossRef]

- Mitchell, R., Curtis, K., Fisher, M. Understanding Trauma as a Menʼs Health Issue. Journal of Trauma Nursing, 2012 19(2), 80–88. [CrossRef]

- Rashid R, Sohrabi C, Kerwan A, Franchi T, Mathew G, Nicola M, Agha RA. The STROCSS 2024 guideline: strengthening the reporting of cohort, cross-sectional, and case control studies in surgery. International Journal of Surgery 2024; 110(6): 3151-3165. [CrossRef]

- Iglay, K., Hannachi, H., Joseph, H.P., Xu, J., Li, X., Engel, S.S., Moore, L.M., Rajpathak, S. Prevalence and co-prevalence of comorbidities among patients with type 2 diabetes mellitus. Current medical research and opinion 2016, 32(7), 1243-1252. [CrossRef]

- Yang, M.M., Hartley, R.L., Leung, A.A., Ronksley, P.E., Jetté, N., Casha, S., Riva-Cambrin, J. Preoperative predictors of poor acute postoperative pain control: a systematic review and meta-analysis. BMJ Open 2019, 9(4), e025091. [CrossRef]

- Bello, U.M., Kannan, P., Chutiyami, M., Salihu, D., Cheong, A.M.Y., Miller, T., Pun, J.W., Muhammad, A.S., Mahmud, F.A., Jalo, H.A., Ali, M.U., Kolo, M.A., Sulaiman, S.K., Lawan, A., Bello, I.M., Gambo, A.A. Winser, S.J. Prevalence of Anxiety and Depression Among the General Population in Africa During the COVID-19 Pandemic: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Front Public Health. 2022, 17;10:814981. [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi A, Bazargan-Hejazi S, Zadie ZH, et al. Pain management in trauma: A review study. Journal of Injury and Violence Research 2016; 8(2): 89-98. [CrossRef]

- Ayano WA, Fentie AM, Tileku M, Jiru T, Hussen SU. Assessment of adequacy and appropriateness of pain management practice among trauma patients at the Ethiopian Aabet Hospital: A prospective observational study. BMC Emergency Medicine 2023; 23: 92.

- Ayano WA, Fentie AM, Tileku M, Jiru T, Hussen SU. Assessment of adequacy and appropriateness of pain management practice among trauma patients at the Ethiopian Aabet Hospital: A prospective observational study. BMC Emergency Medicine 2023; 23: 92.

- Crush, J., Levy, N., Knaggs, R.D., Lobo, D.N. Misappropriation of the 1986 WHO analgesic ladder: the pitfalls of labelling opioids as weak or strong. British Journal of Anaesthesia 2022, 129(2), 137-142. [CrossRef]

- Miller E. The World Health Organization analgesic ladder. Journal of Midwifery & Women’s Health 2004; 49(6): 542-545.

- Vargas-Schaffer G and Cogan J. Patient therapeutic education: Placing the patient at the centre of the WHO analgesic ladder. Canadian Family Physician 2014; 60: 235- 241.

- Morone NE; Weiner DK. Pain as the fifth vital sign: exposing the vital need for pain education. Clinical Therapeutics 2013; 35(11): 1728-1732. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).