Submitted:

02 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

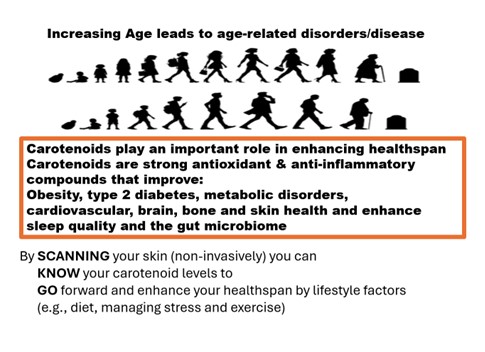

1. Introduction

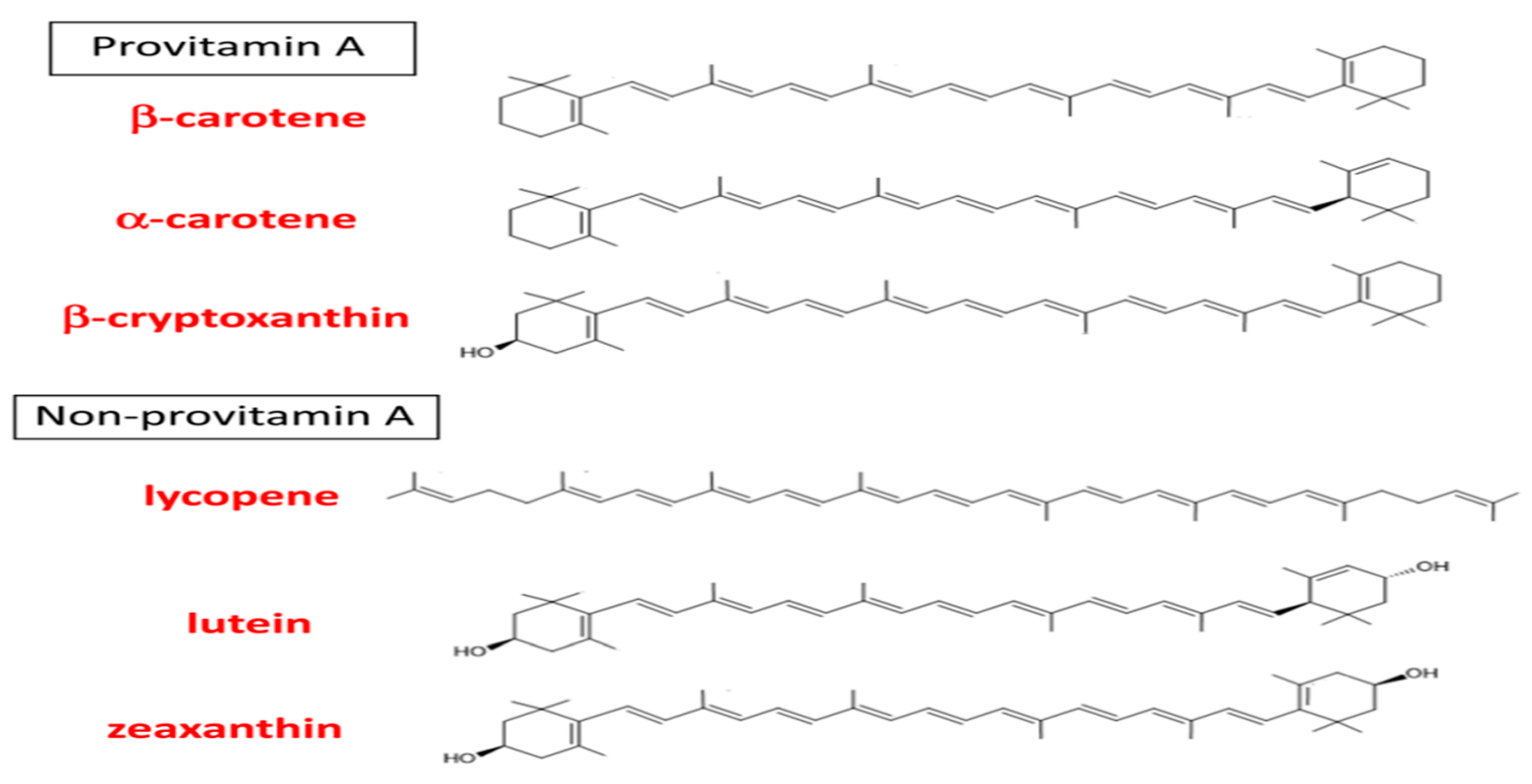

2. Carotenoids: Chemical Nature, Distribution in Foods & Supplements and Comparison of Antioxidant Activities

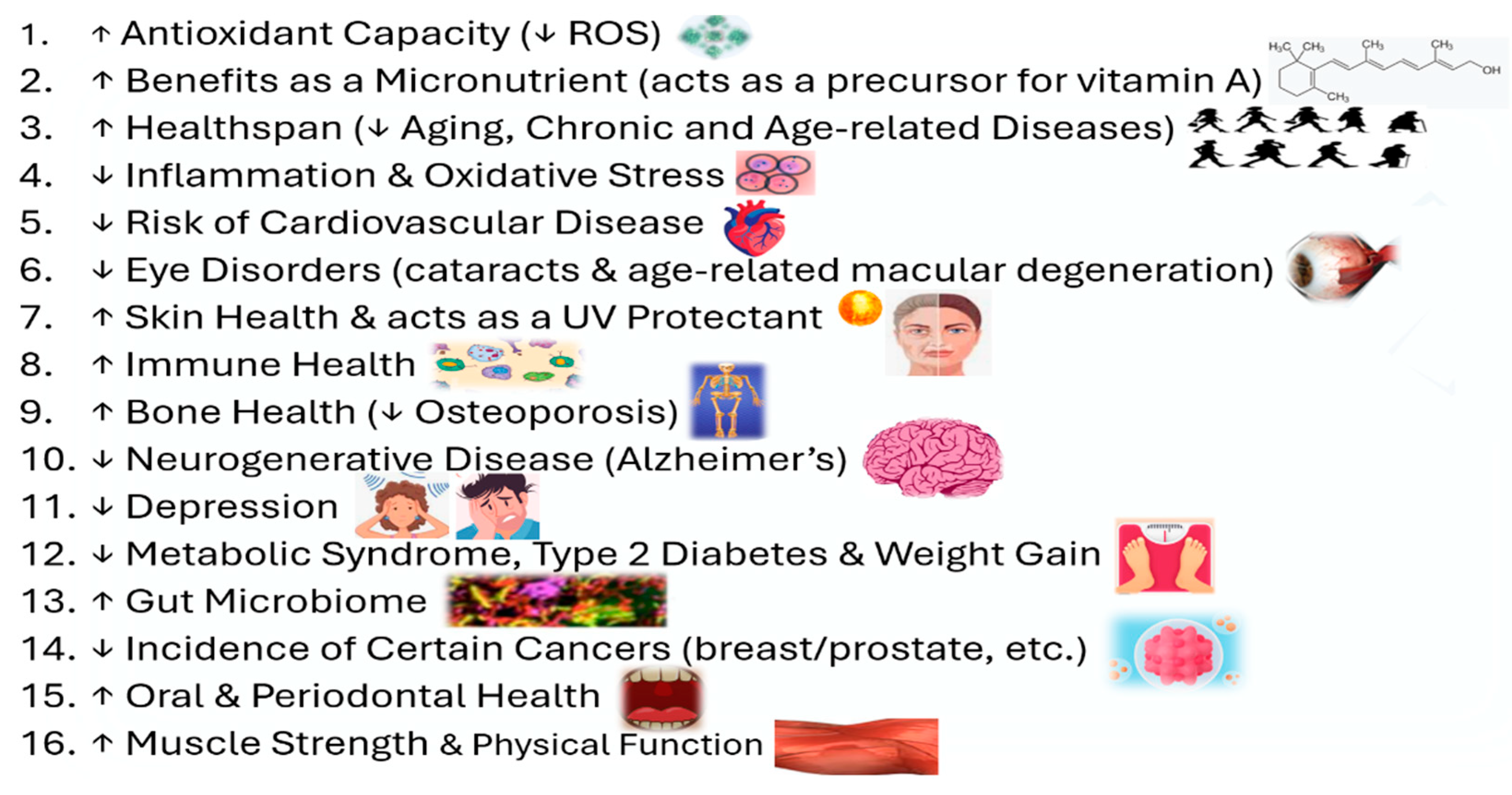

3. Benefits of Carotenoids in Health/Disease and How They Enhance Antioxidant Activity

3.1. Carotenoids ↑ Antioxidant Capacity and ↓ Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS)

3.2. Benefits of Carotenoids as a Micronutrient (acts as a precursor for vitamin A)

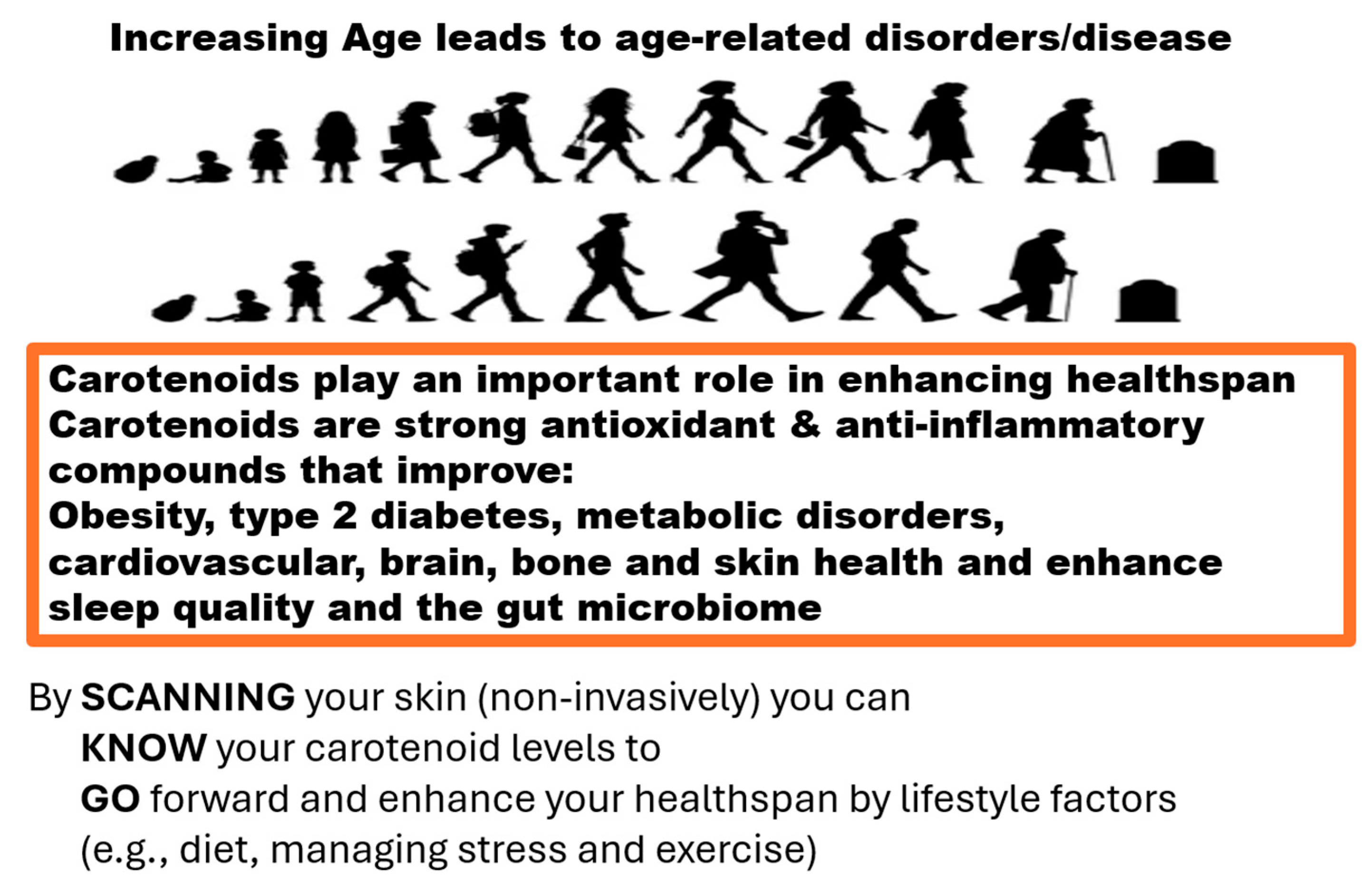

3.3. ↑ Healthspan (↓ Aging, Chronic and Age-related Diseases) with Carotenoids

3.4. ↓ Inflammation & Oxidative Stress (OS) with Carotenoids

3.5. ↓ Risk of Cardiovascular Disease with Carotenoids

3.6. ↓ Eye Disorders (cataracts & age-related macular degeneration) with Carotenoids

3.7. Carotenoids ↑ Skin Health & Acts as a UV Protectant

3.8. ↑ Immune Health via Carotenoids

3.9. ↑ Bone Health (↓ in Osteoporosis) with Carotenoids

3.10. ↓ Neurodegenerative Disease (Alzheimer’s) with Carotenoids

3.11. ↓ Depression with Carotenoidss

3.12. ↓ Metabolic Syndrome, Type 2 Diabetes (T2D) & Weight Gain with Carotenoids

3.13. ↑ Gut Microbiome with Carotenoids

3.14. ↓ Incidence of Certain Cancers with Carotenoids

3.15. ↑ Oral and Periodontal Health with Carotenoids

3.16. ↑ Muscle Strength and Physical Function with Carotenoids

3.17. Summary Linking Carotenoid Intake to Enhancing Healthspan

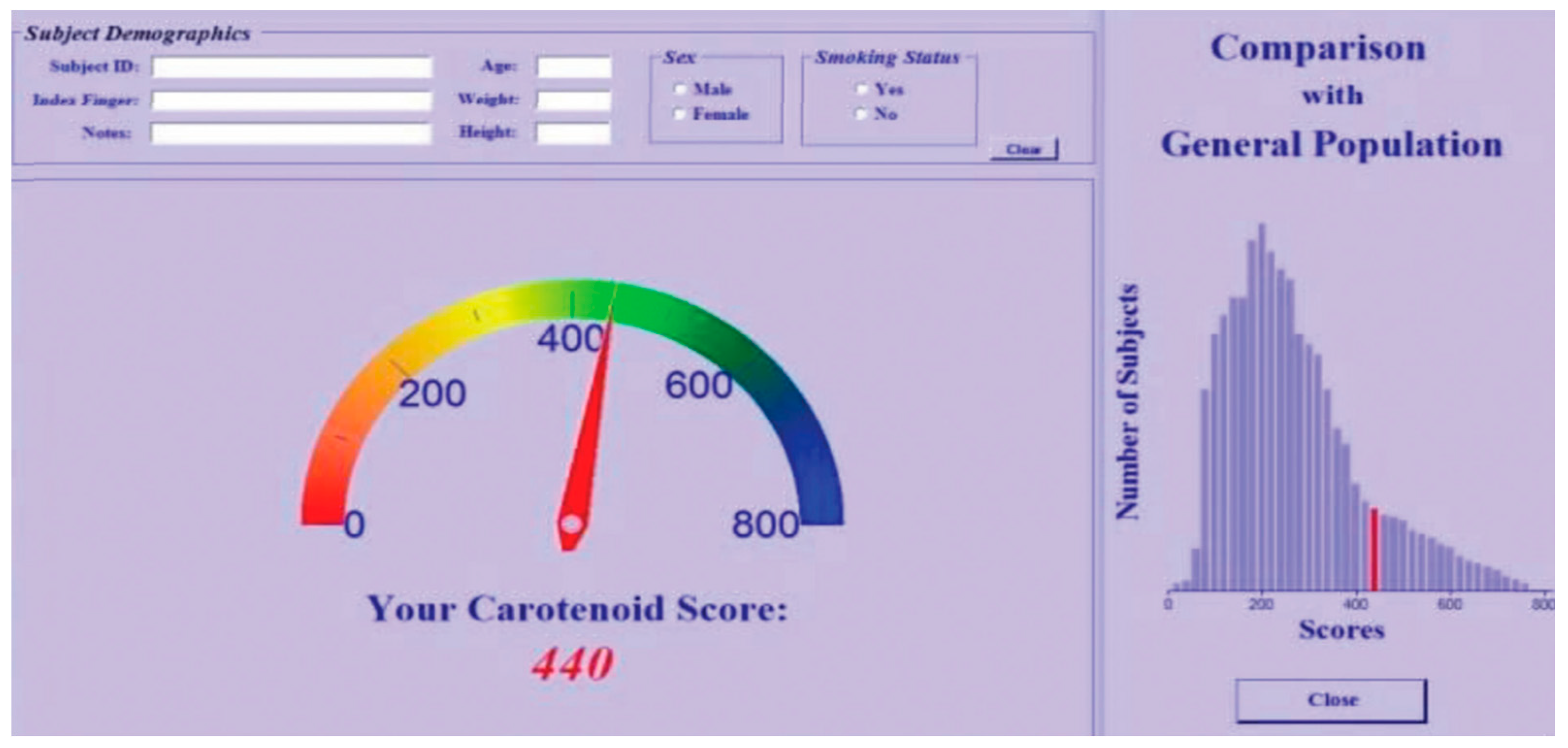

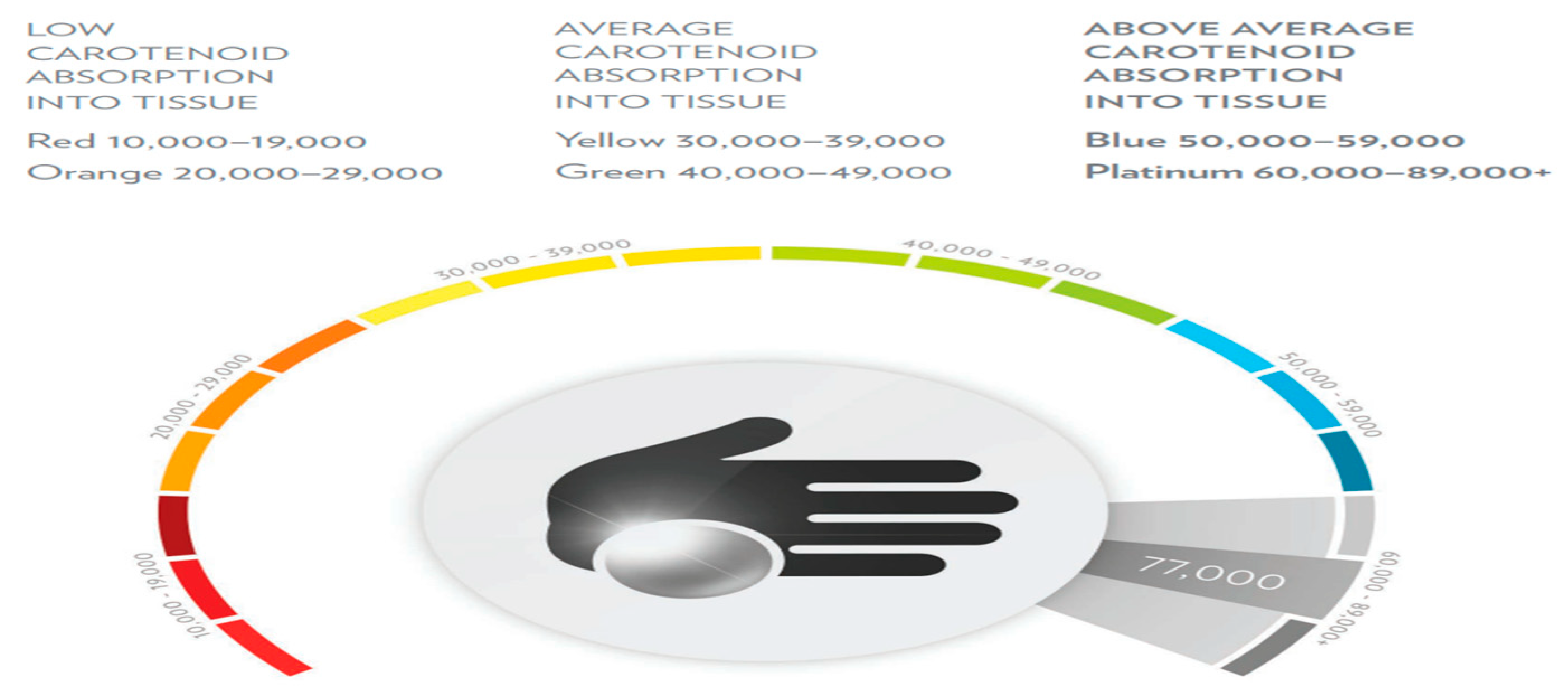

4. Spectroscopy Methods for Quantification of Skin Carotenoids

5. Non-invasive RS & RRS Spectroscopy-based Skin Carotenoid Levels, Implications to Healthspan

5.1. Can Daily Habits Influence Healthspan?

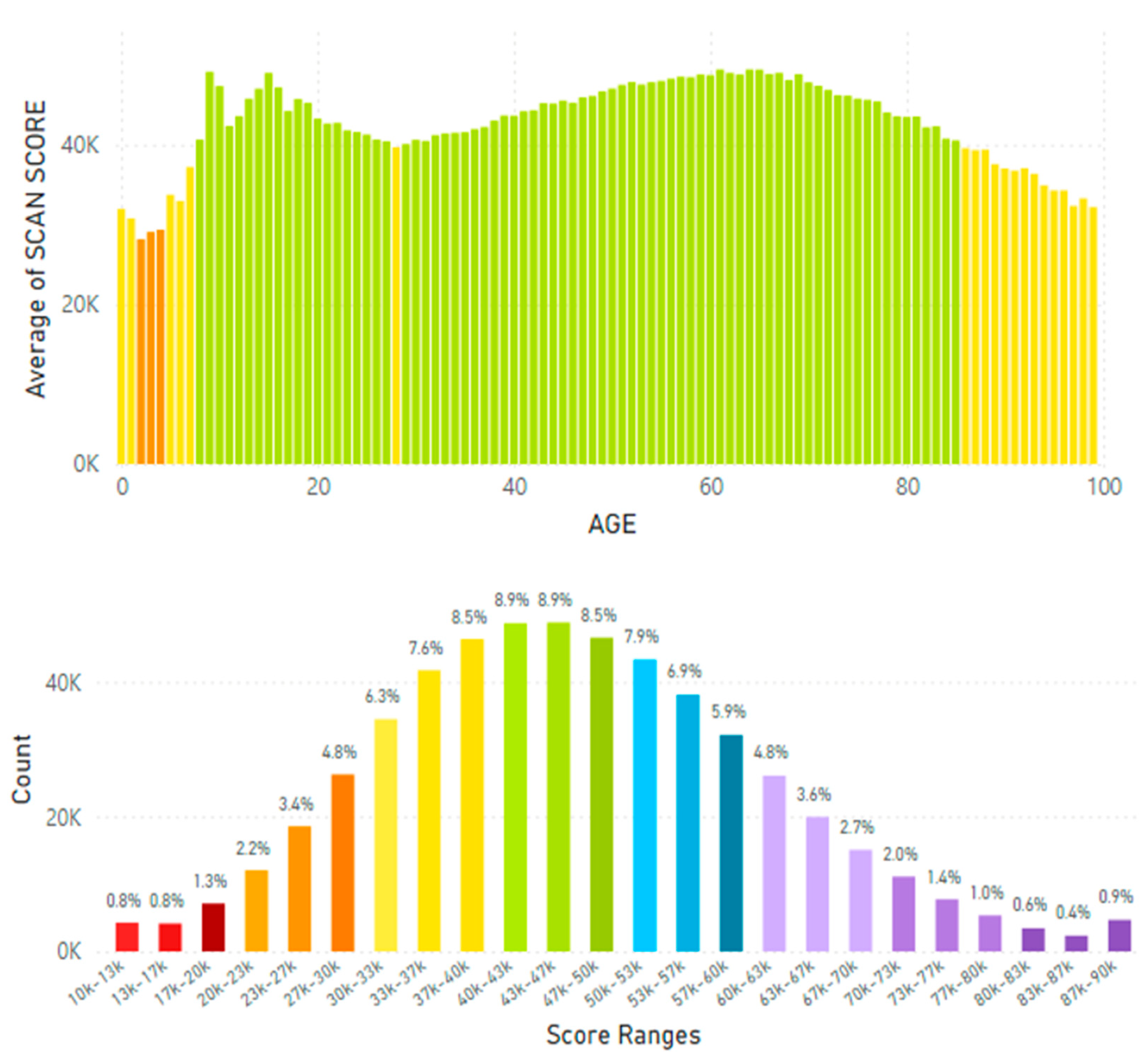

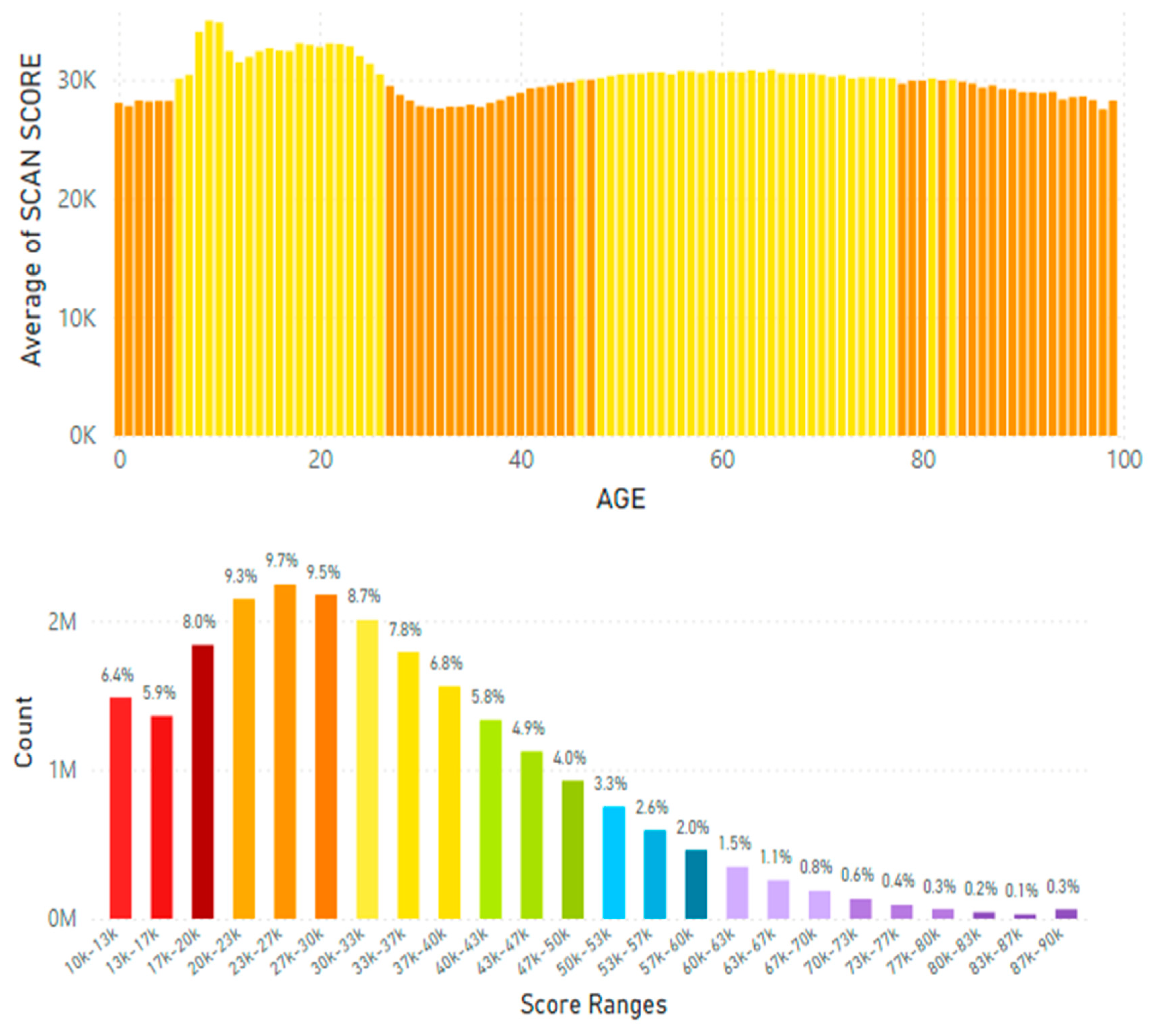

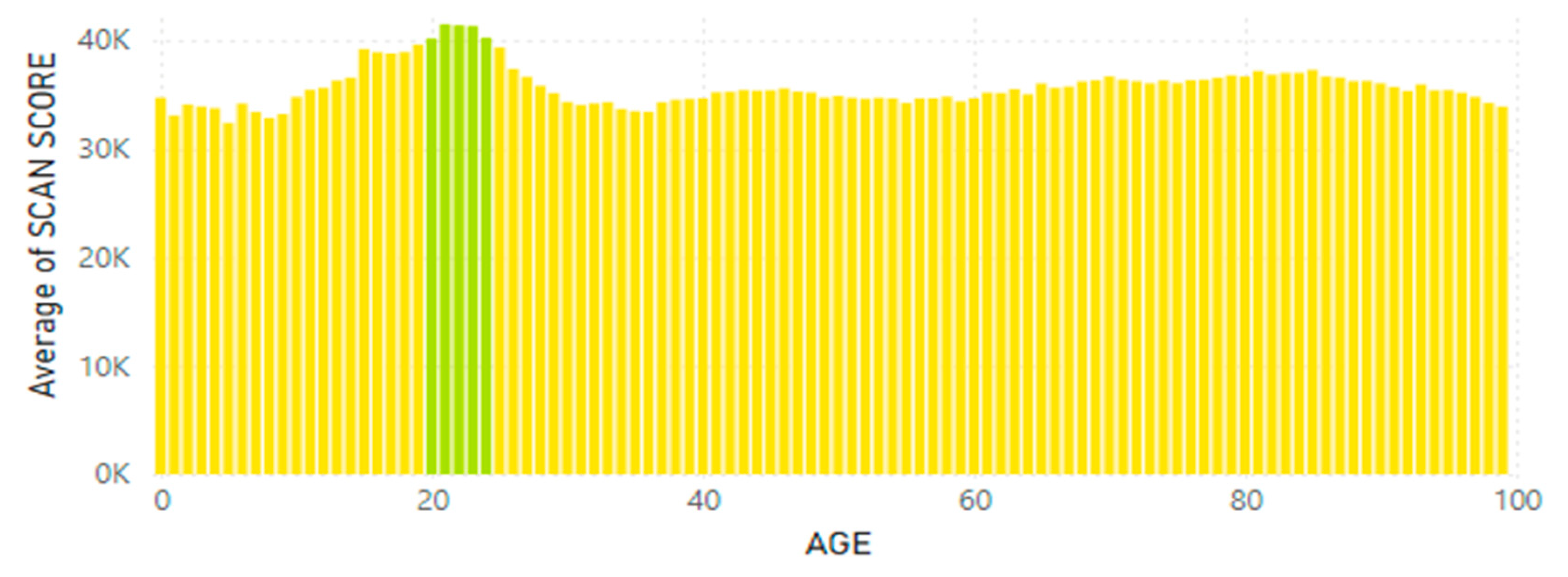

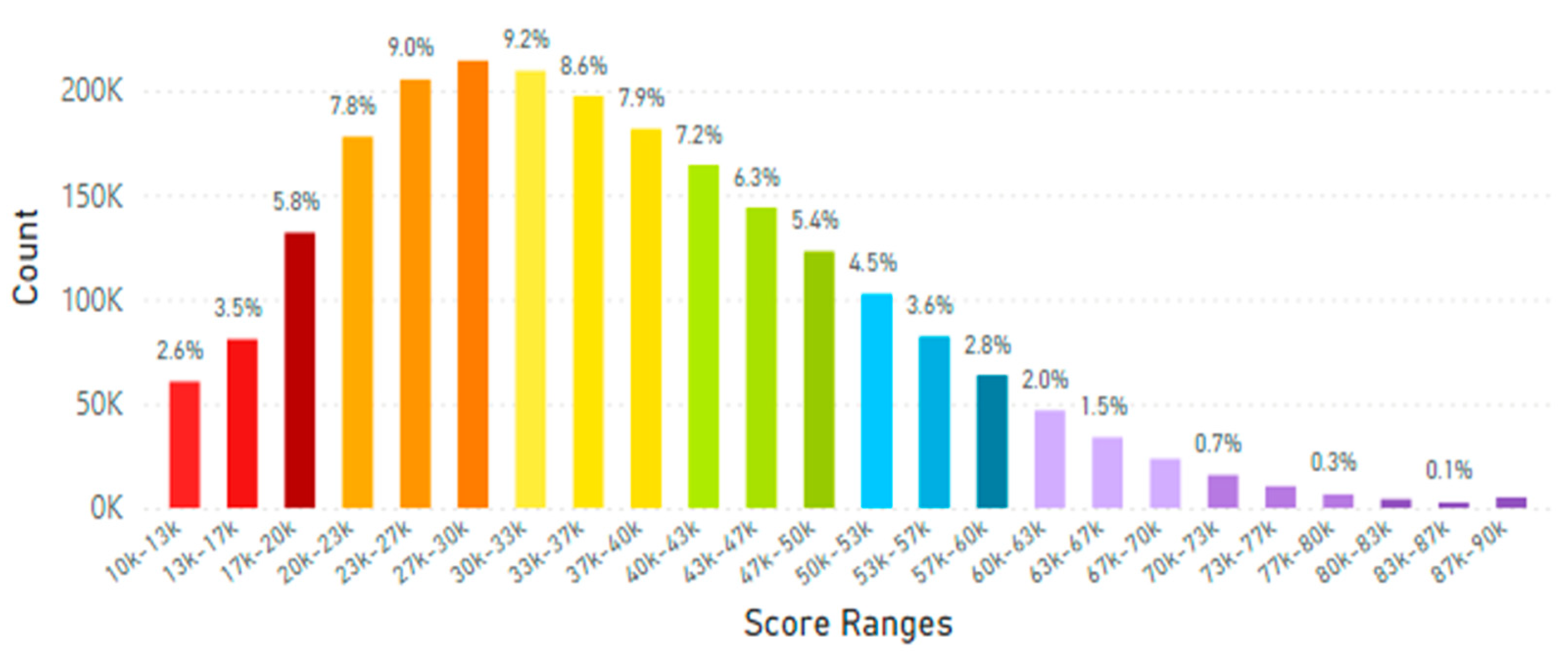

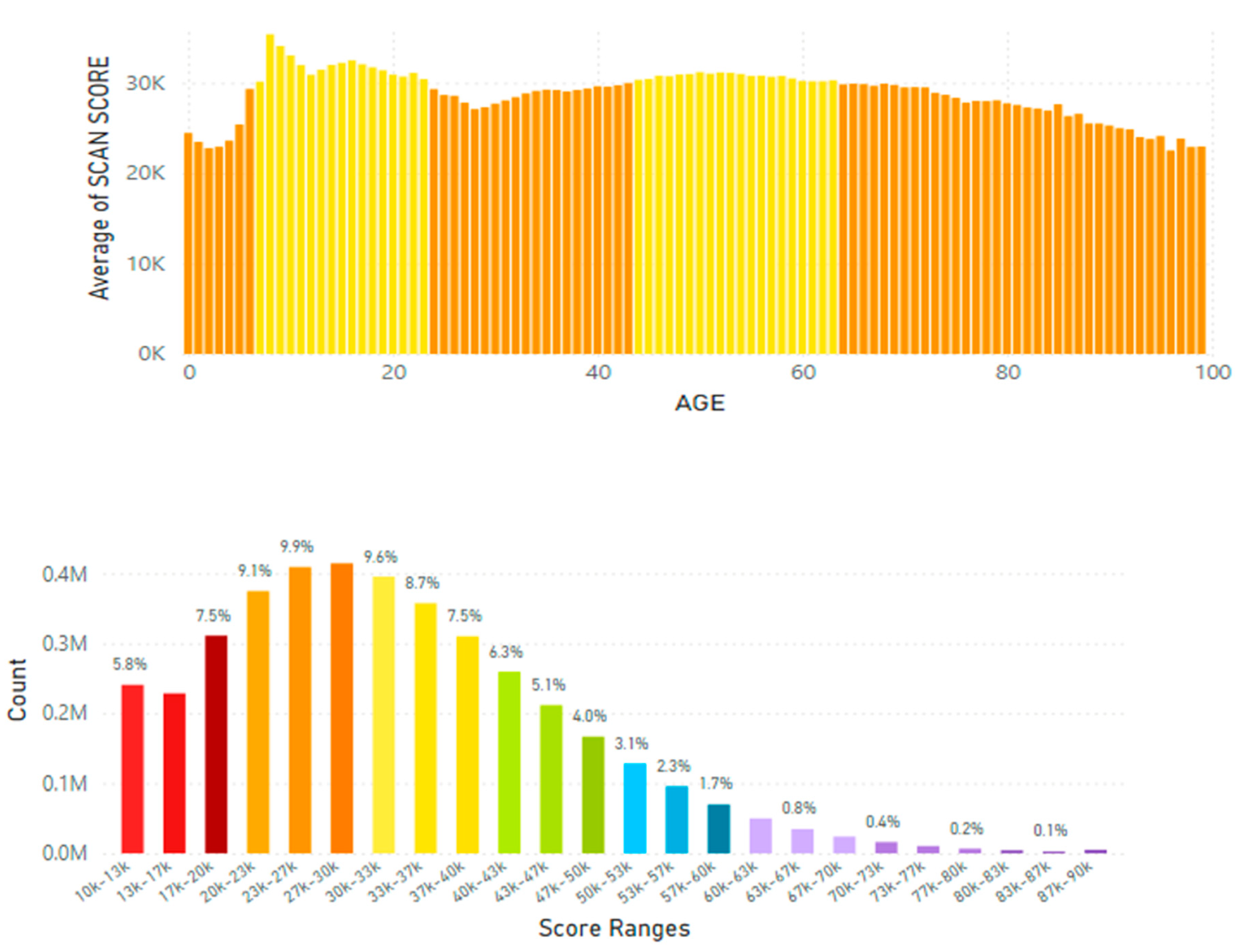

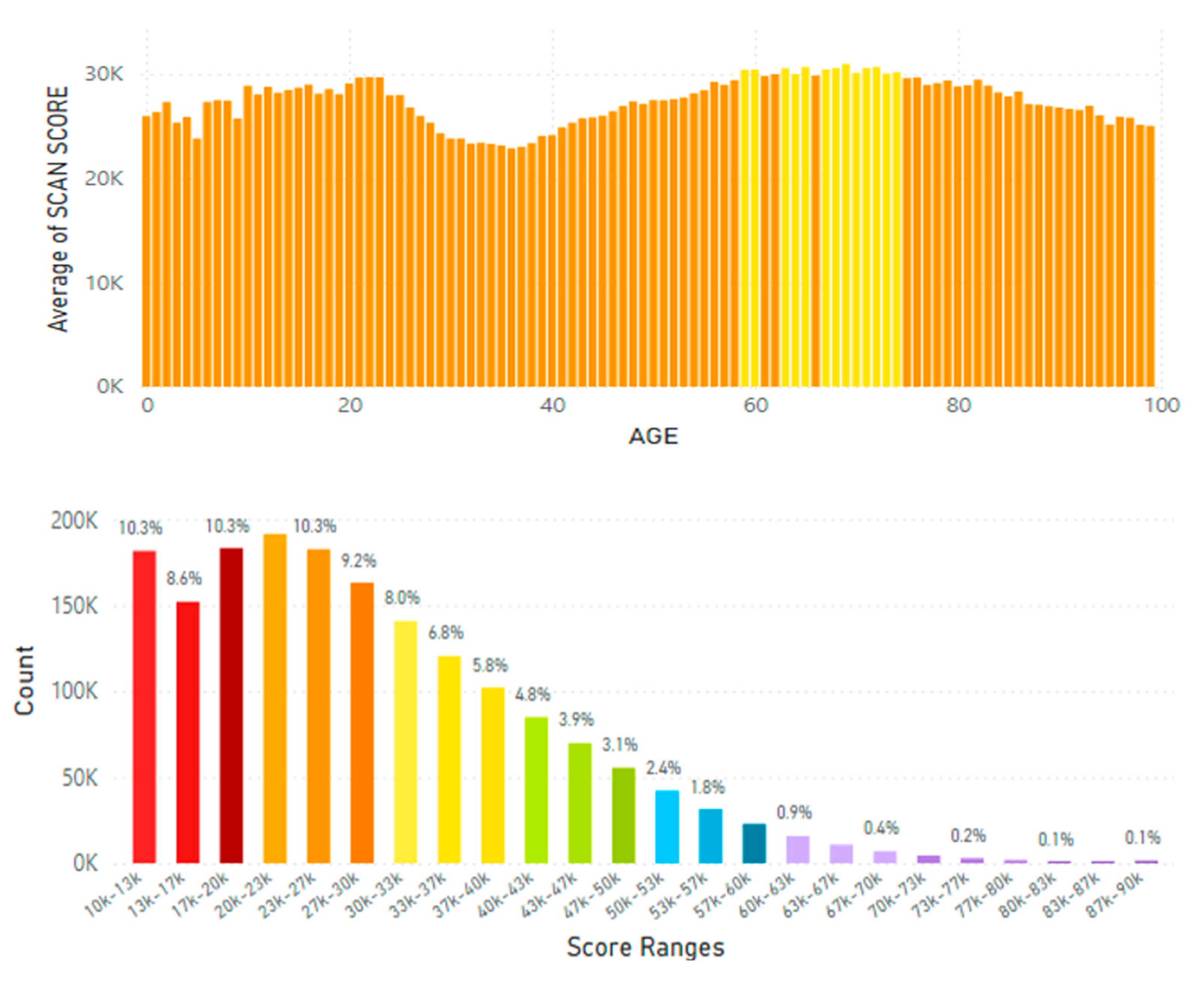

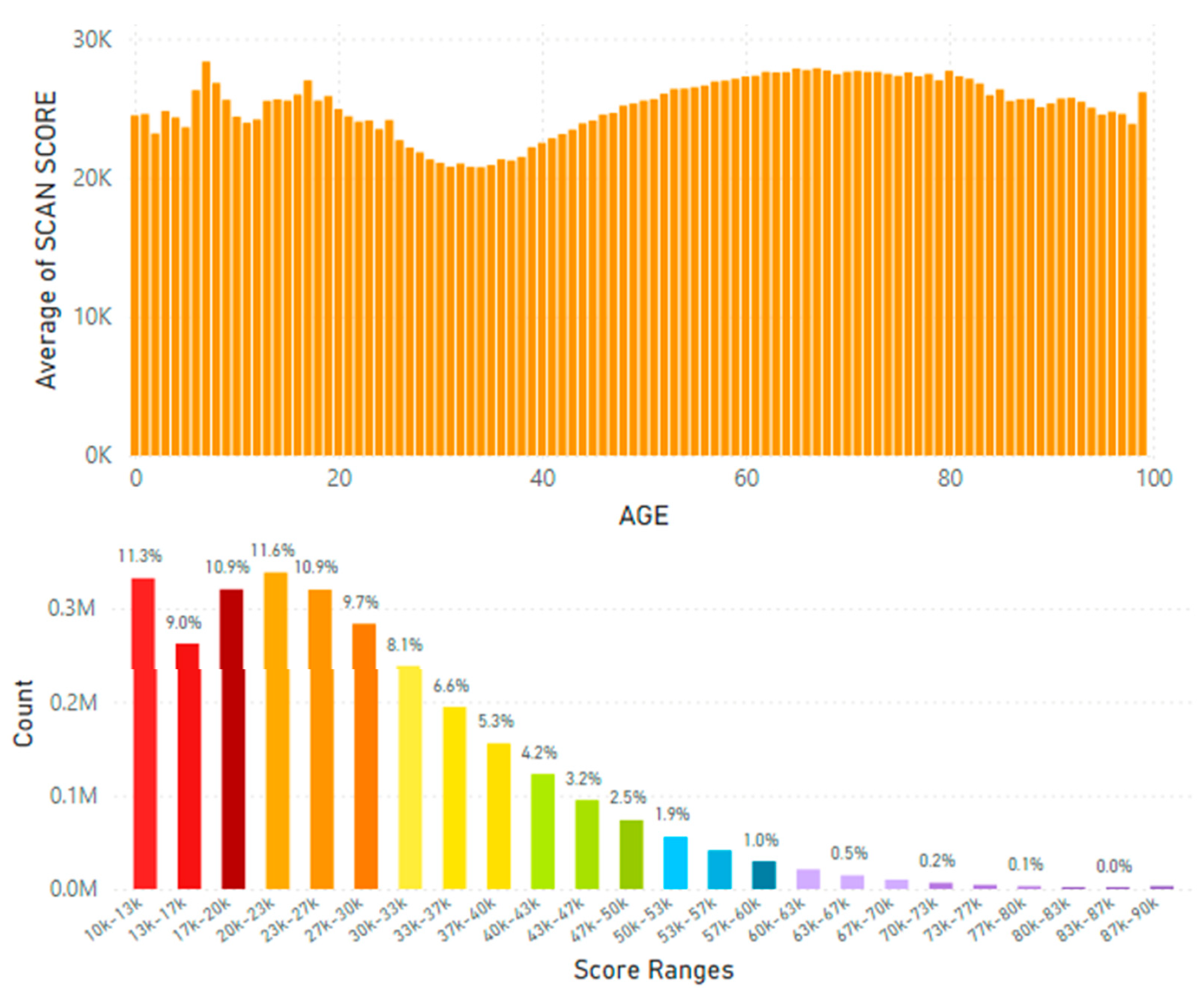

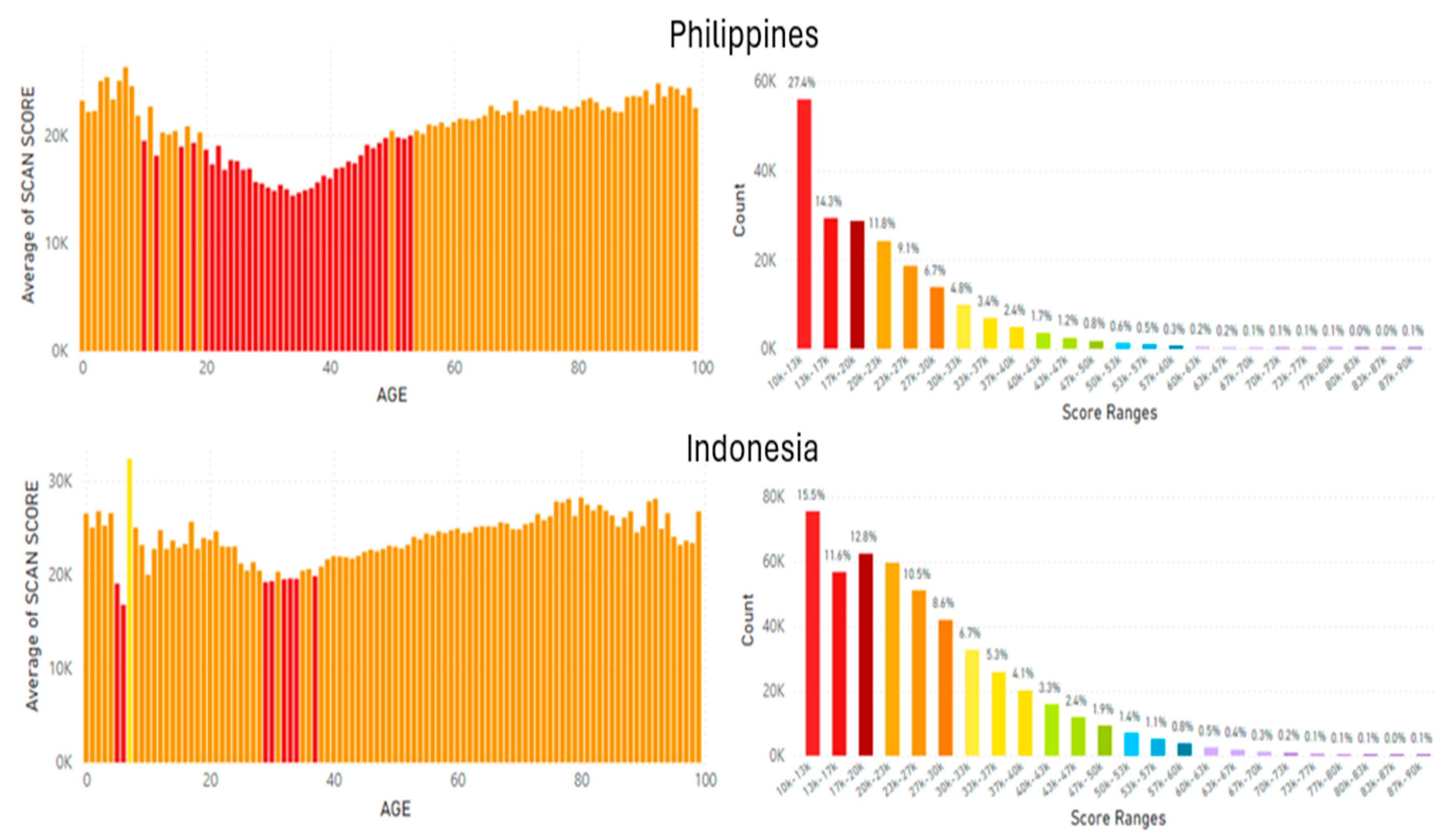

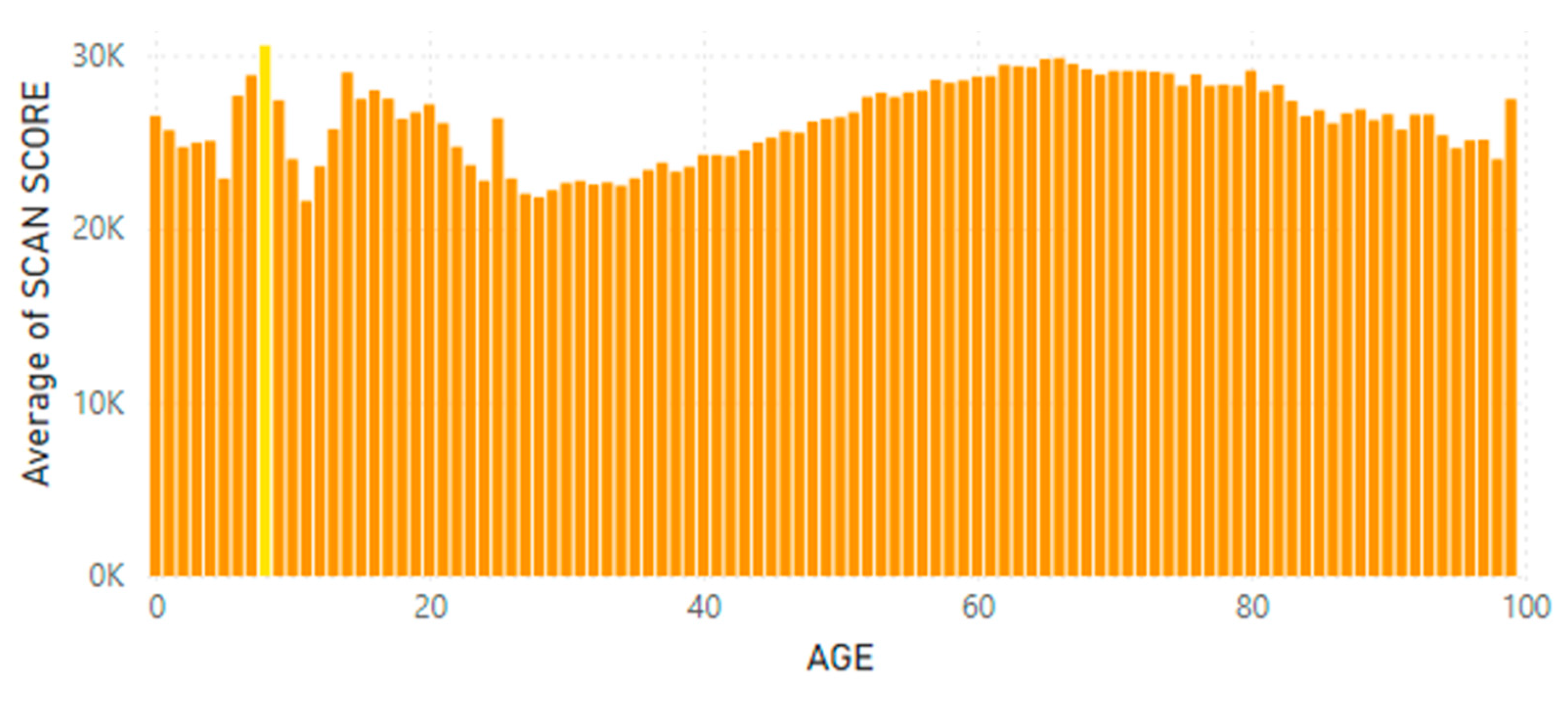

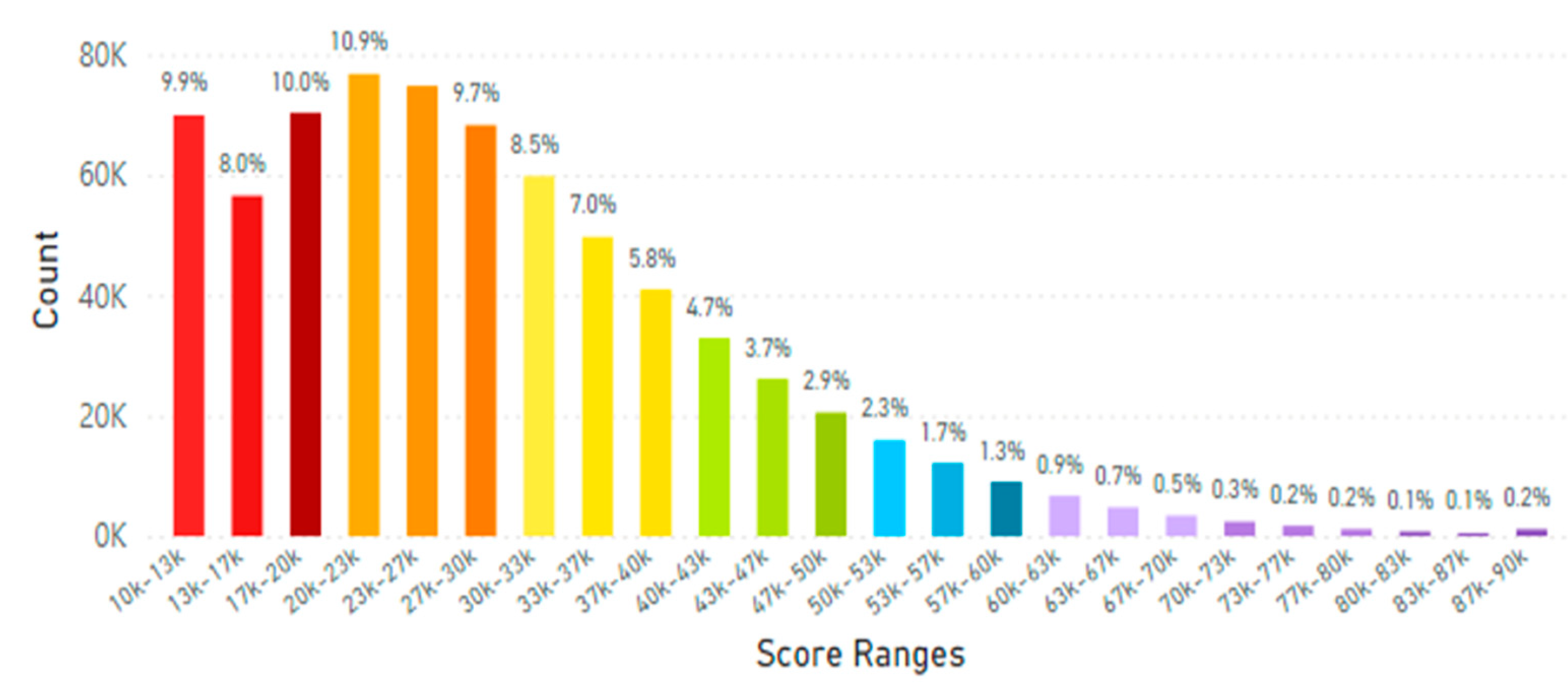

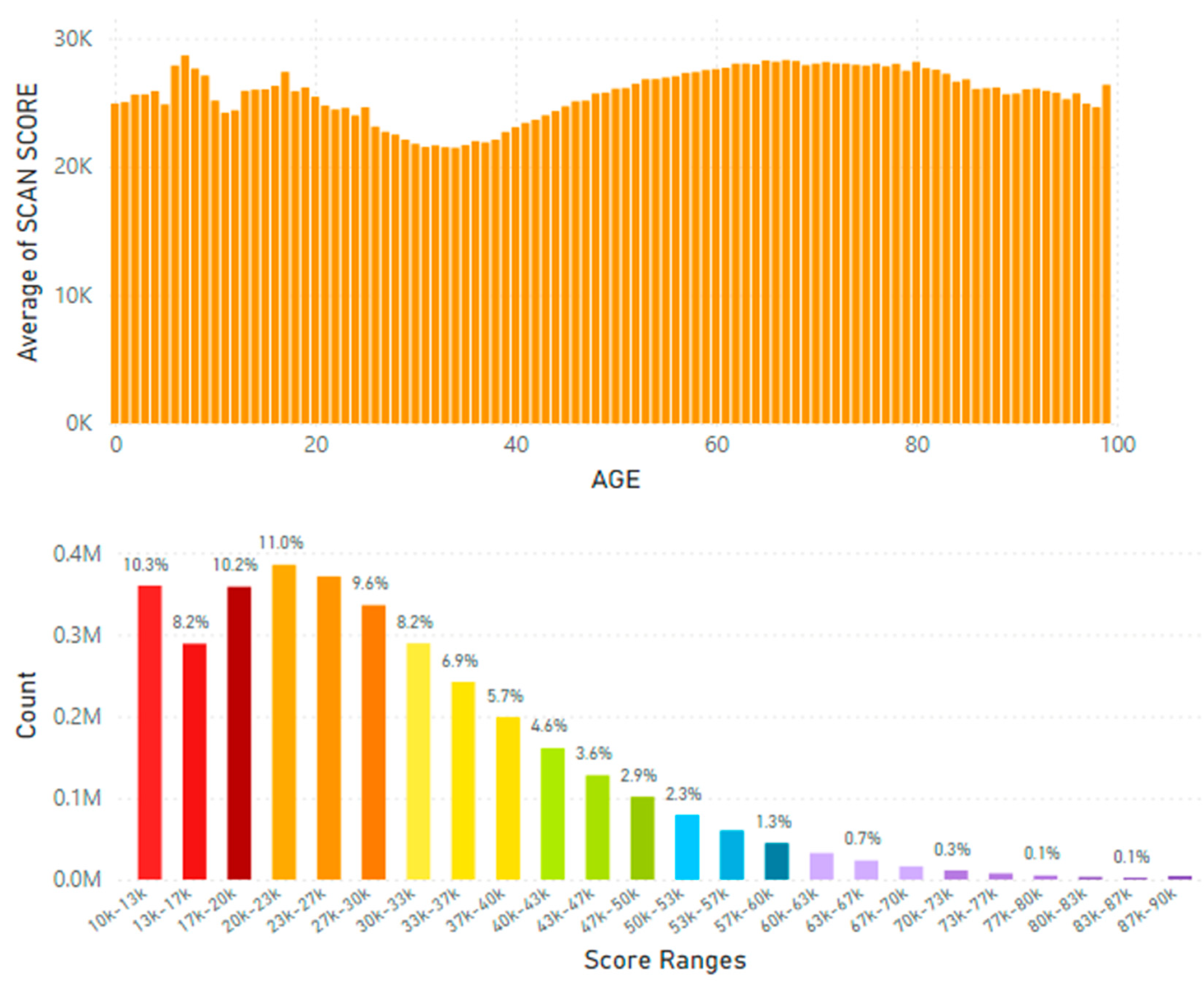

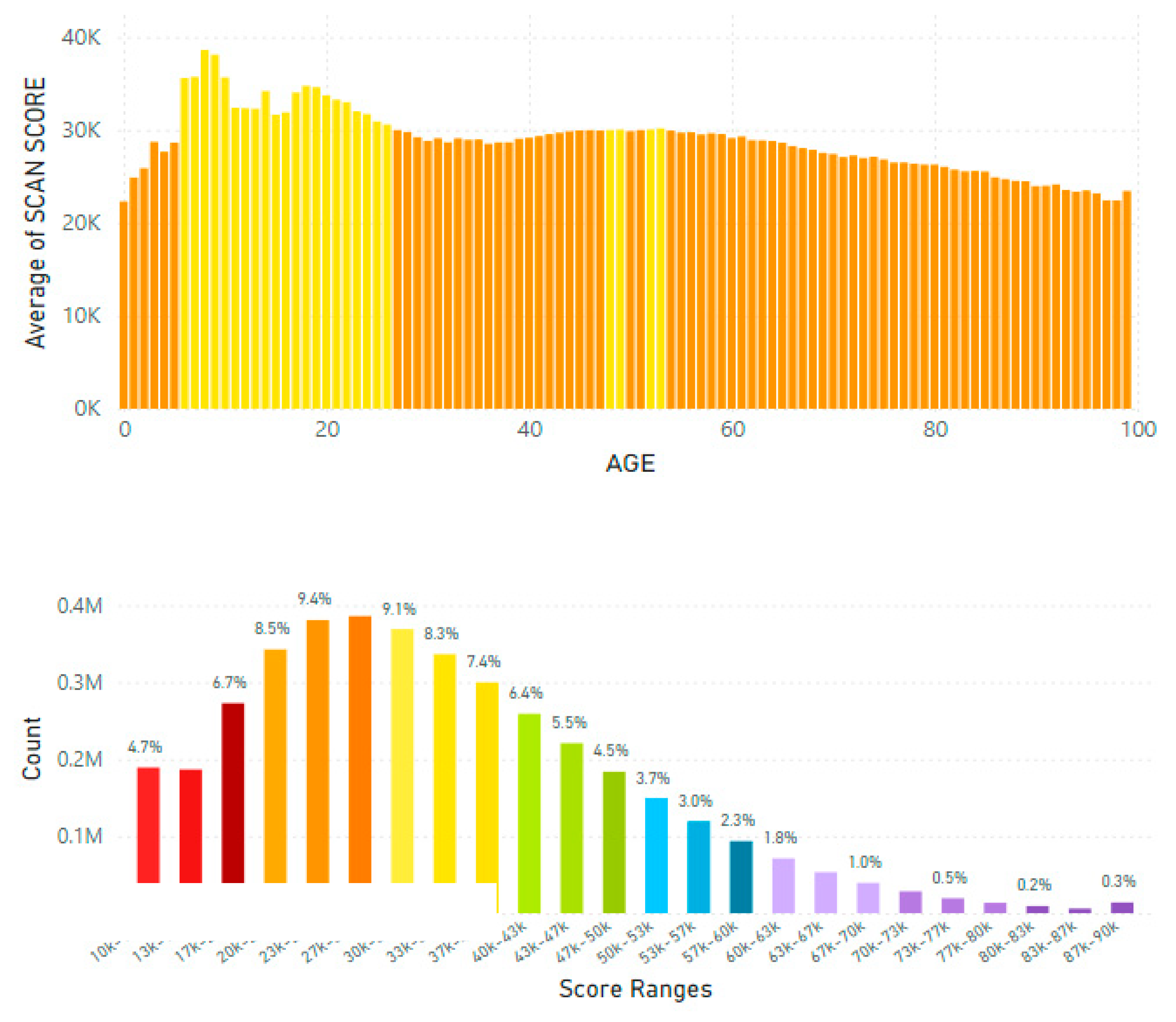

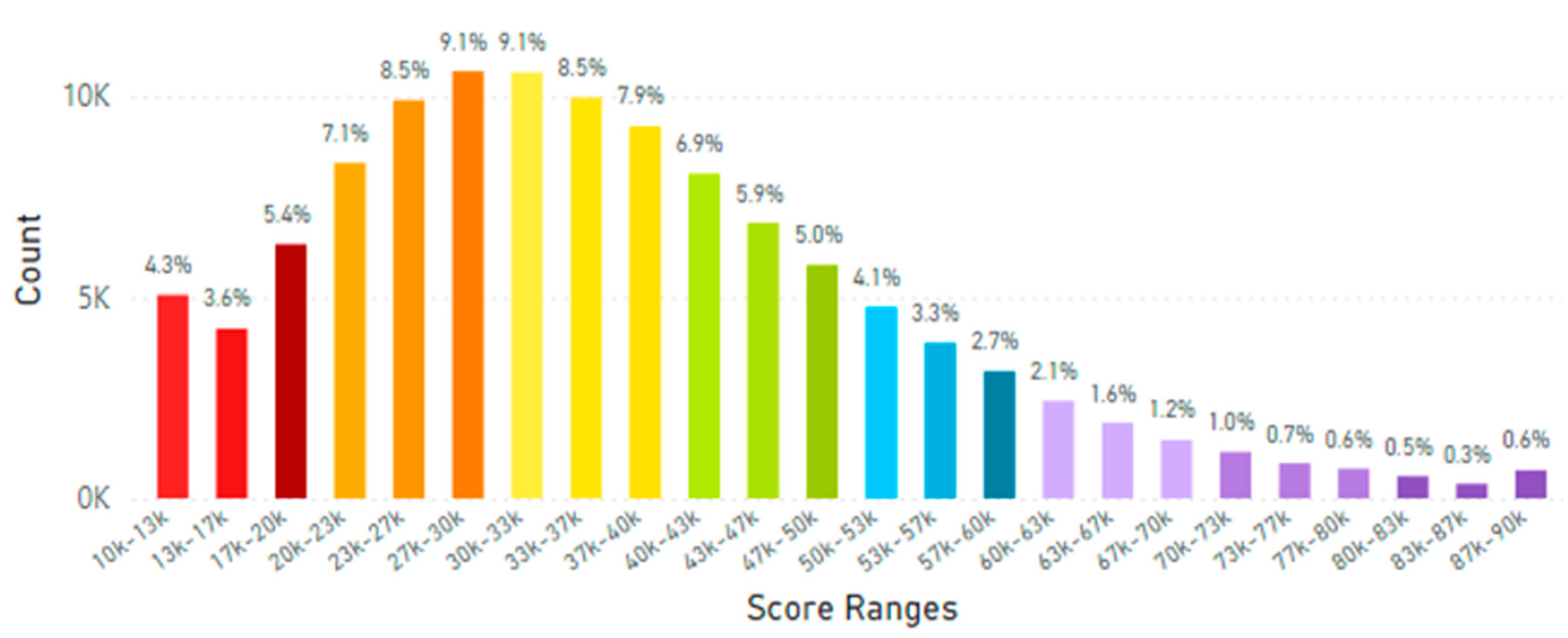

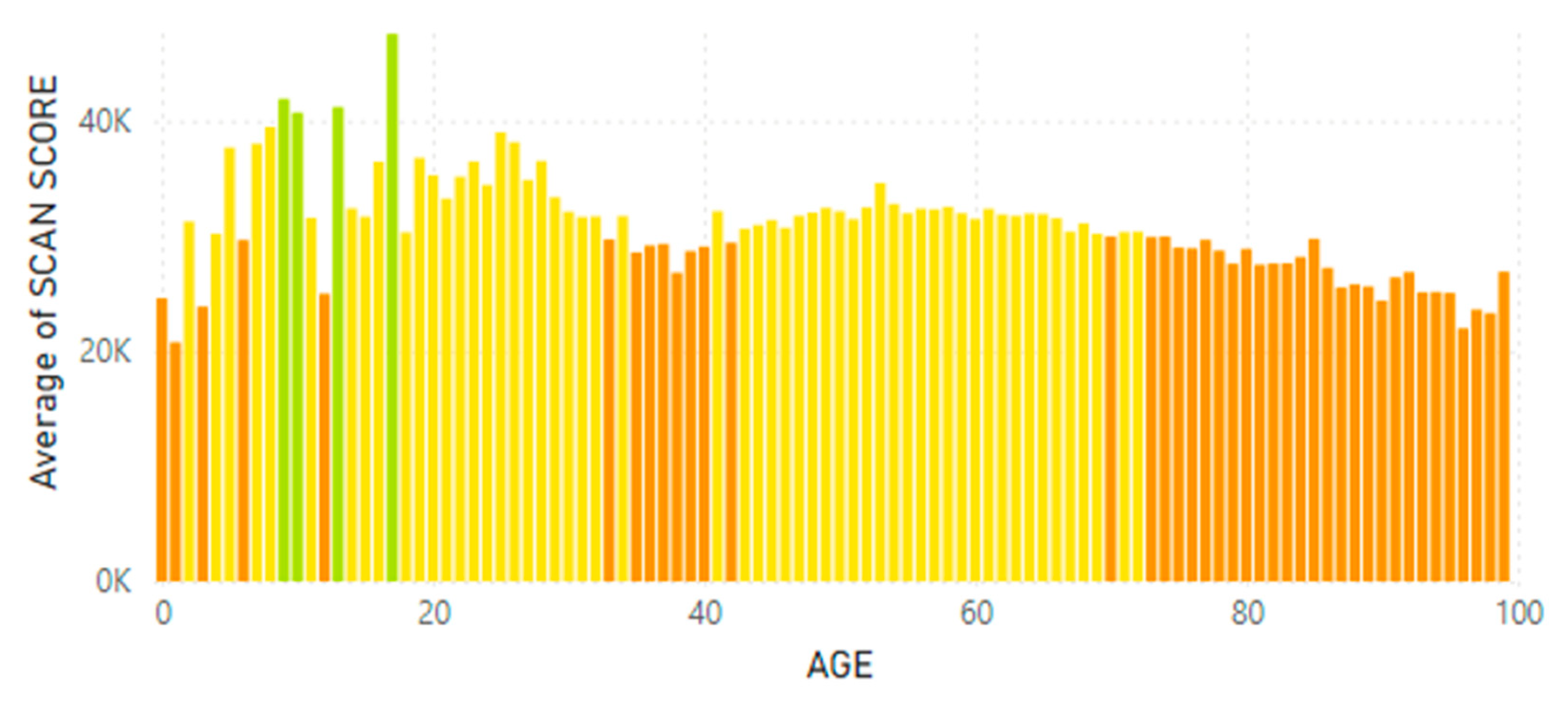

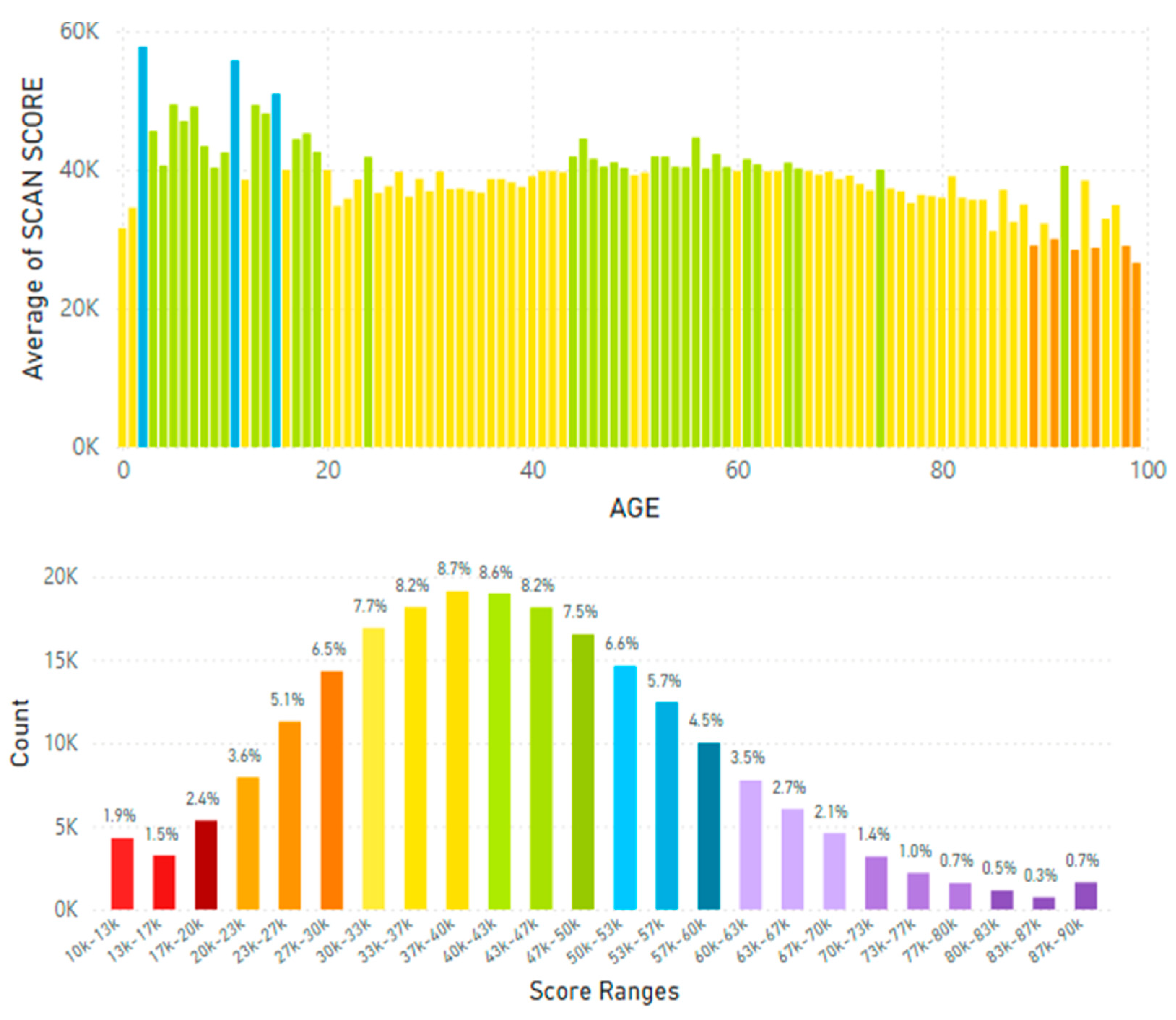

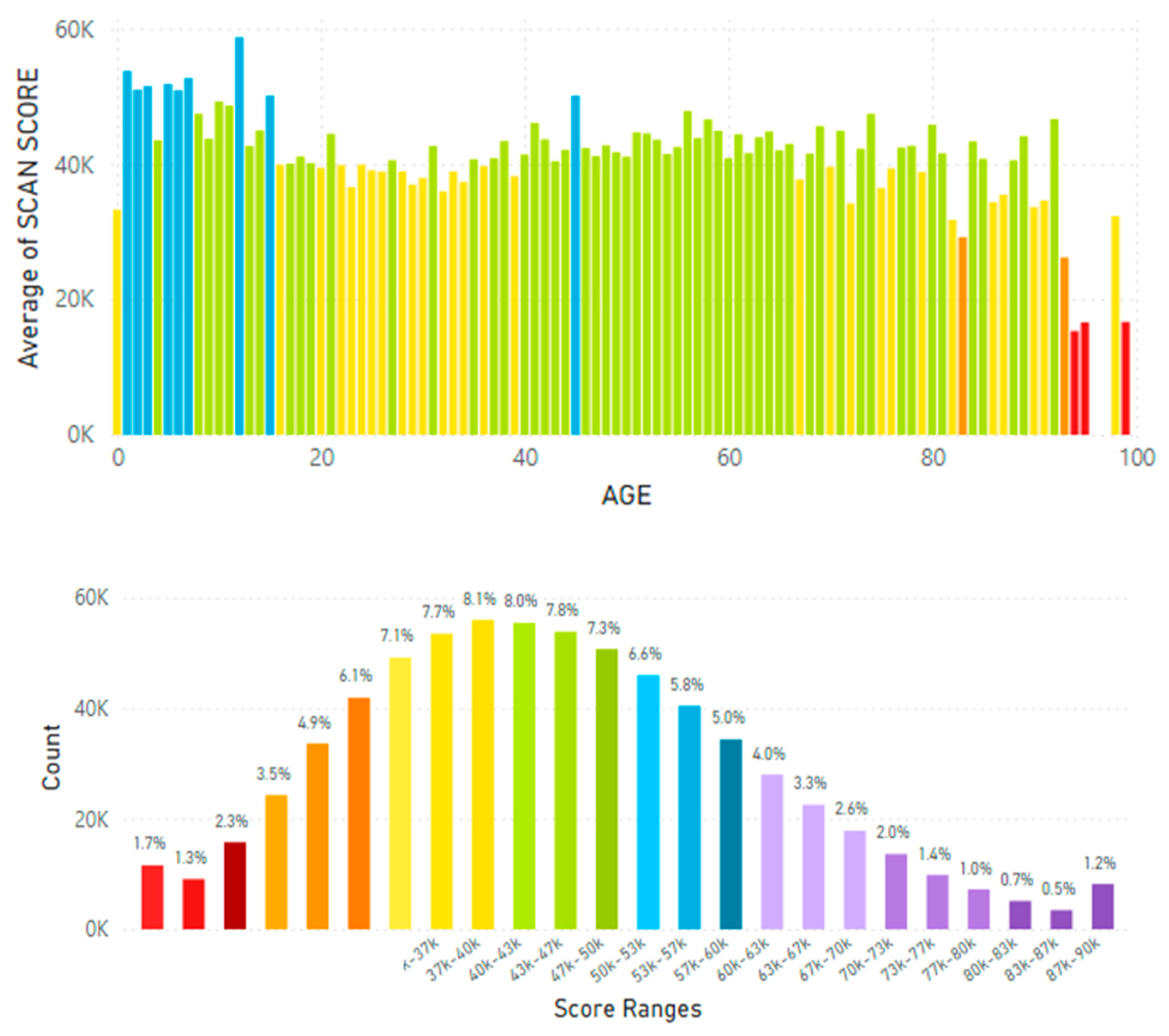

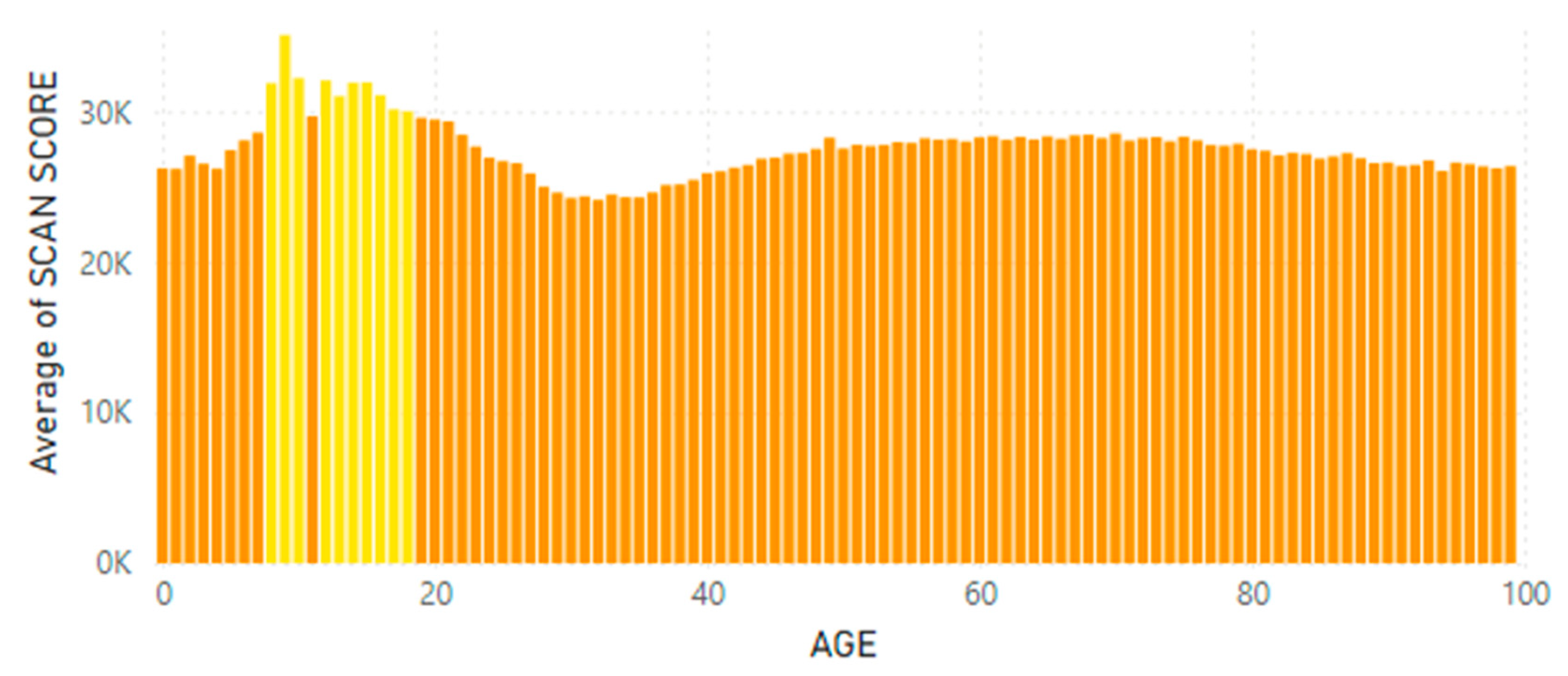

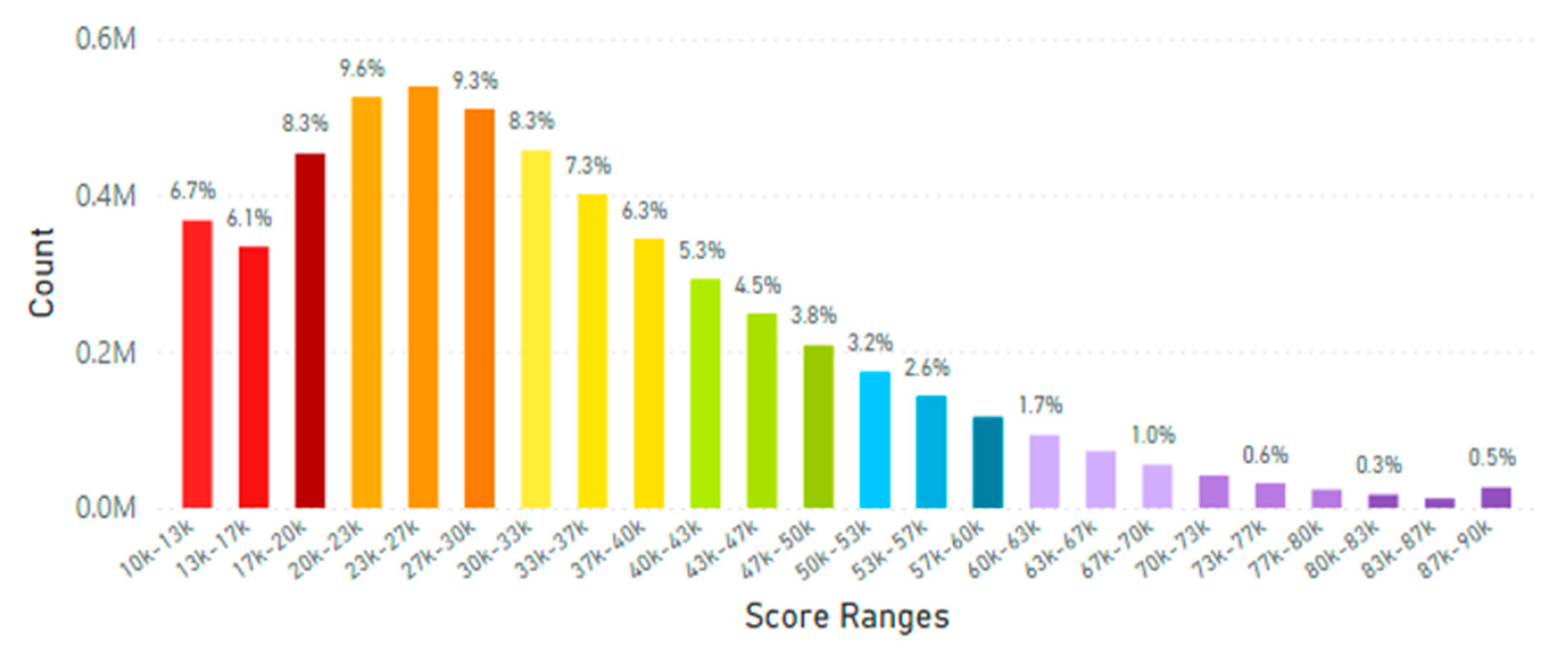

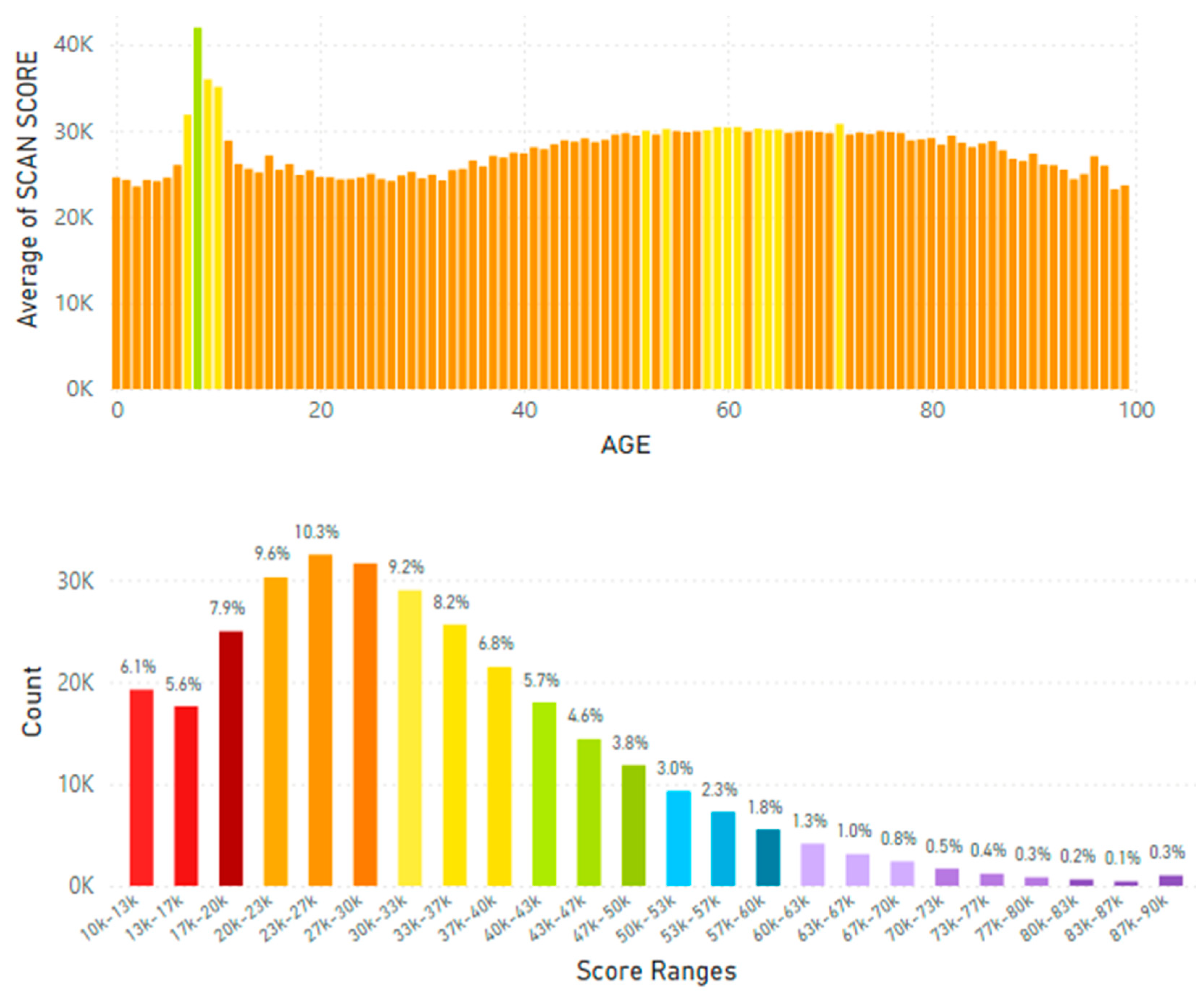

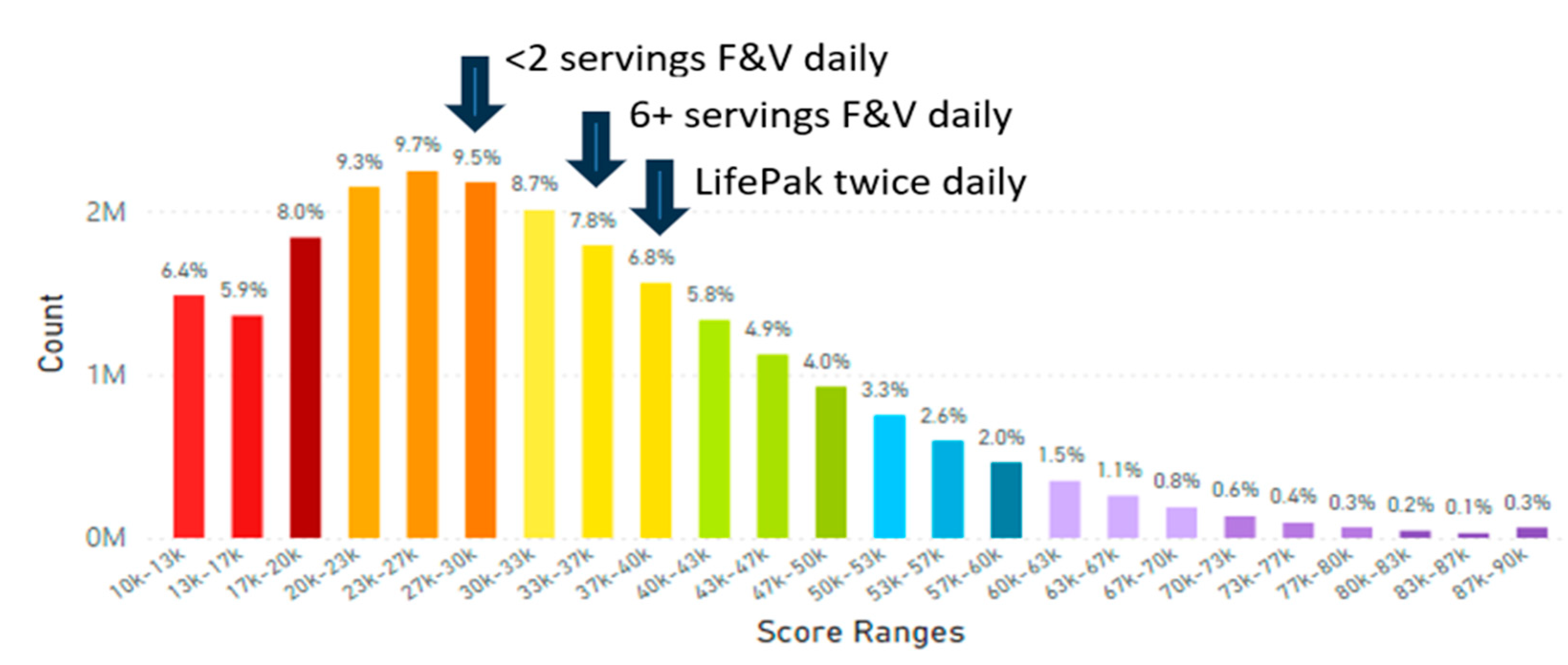

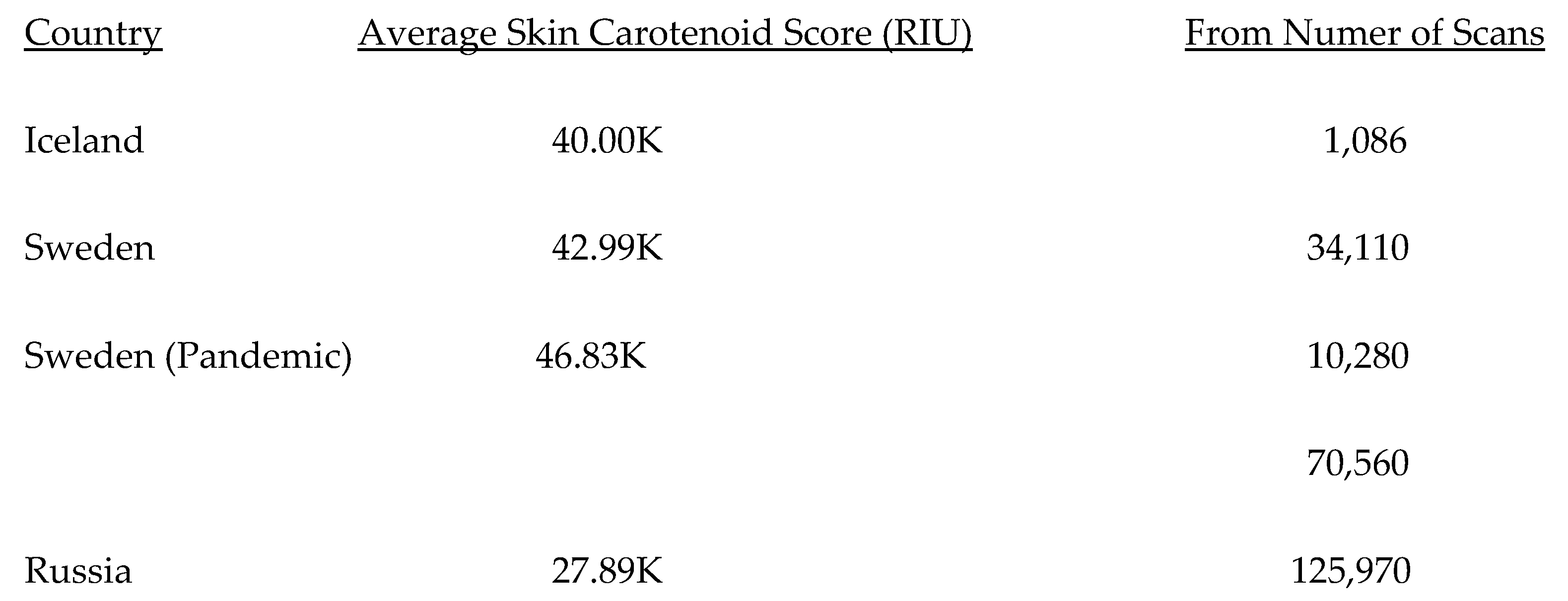

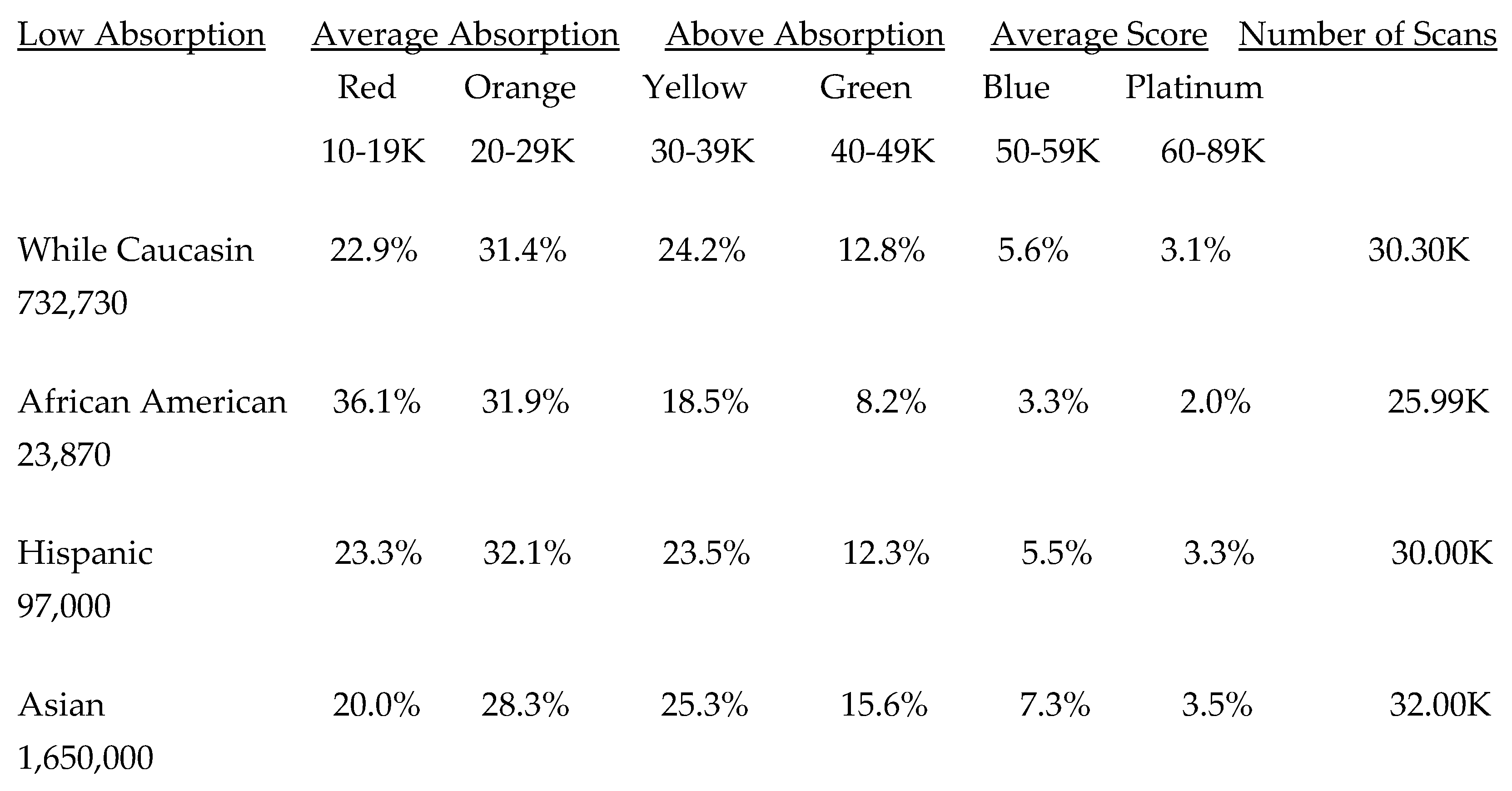

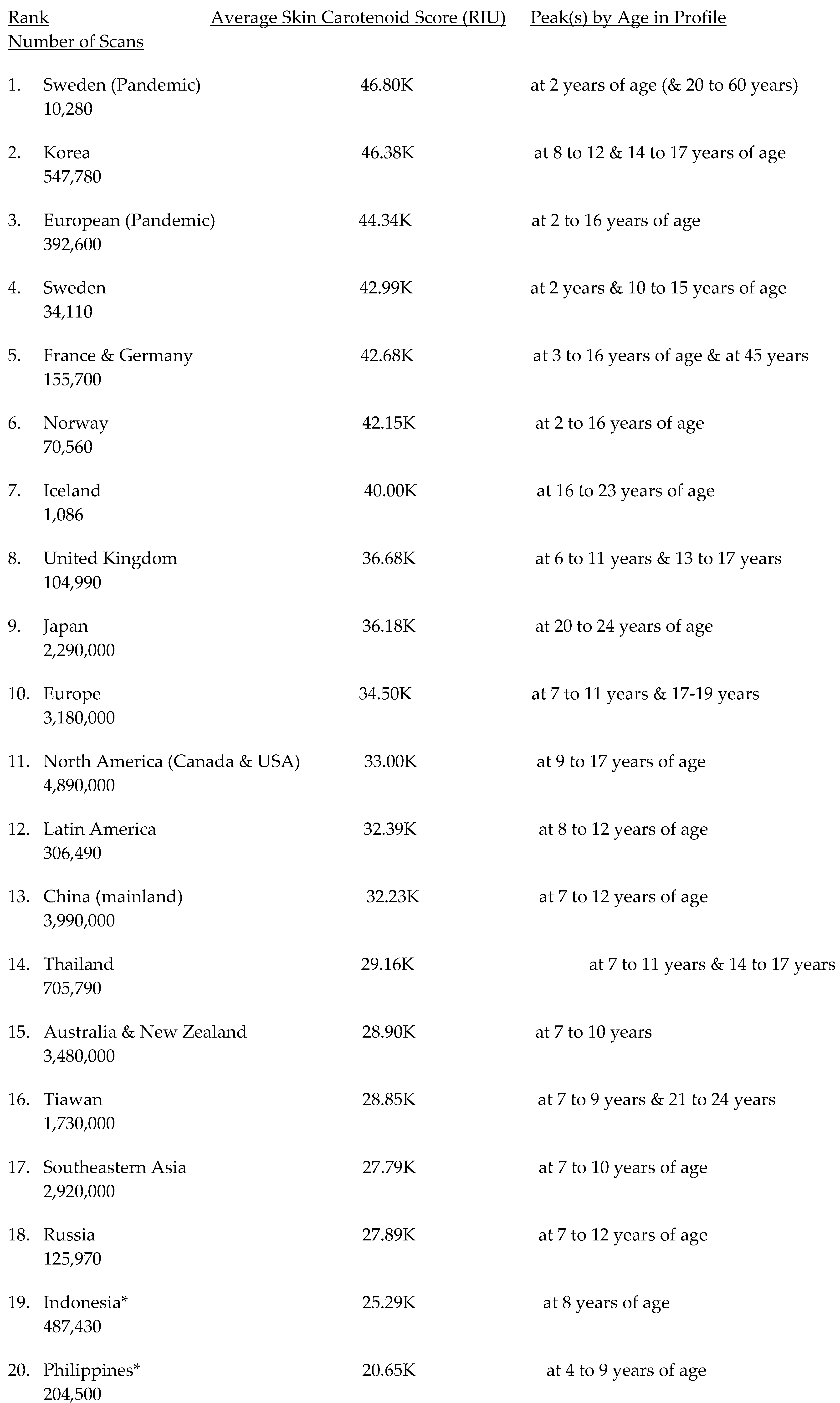

5.2. Lifetime and Worldwide Skin Carotenoid Scanning RRS Data Scores

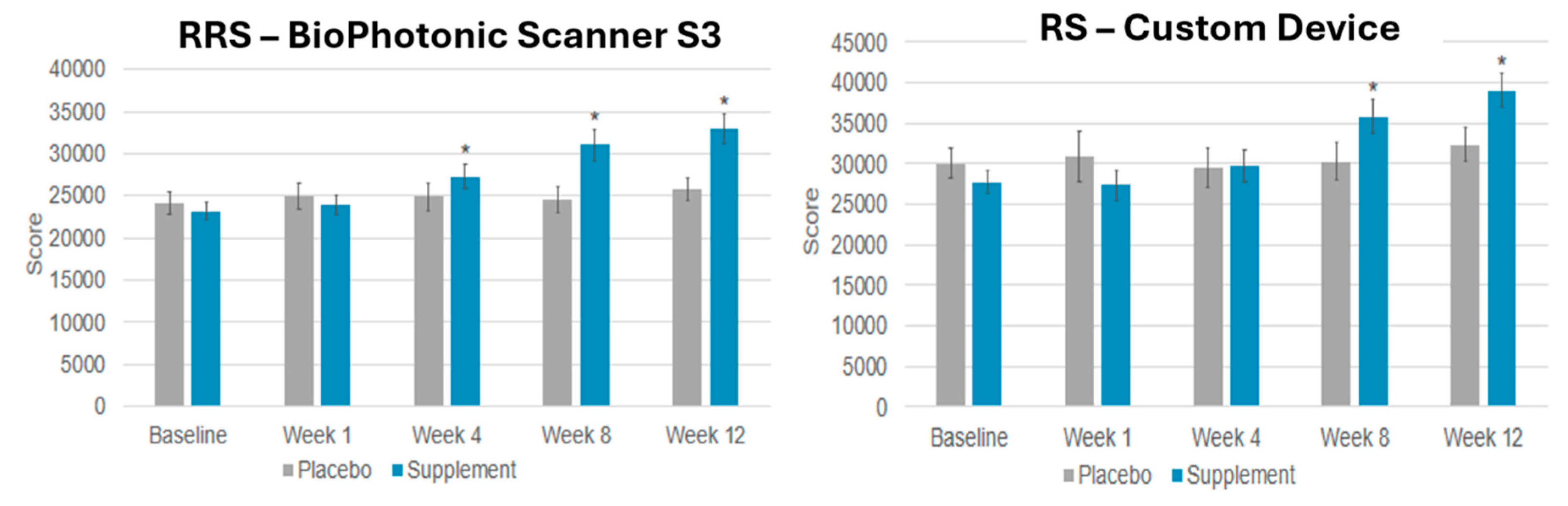

6. Can Nutraceutical Supplementation Increase Skin Carotenoids Levels?

7. Conclusions

8. Future Directions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| α | alpha |

| β | beta |

| AMD | age-related macular degeneration |

| BMD | bone mineral density |

| CARS | coherent anti-strokes Raman spectroscopy |

| CGM | continuous glucose monitoring |

| COPD | chronic obstructive pulmonary disease |

| CSF | cerebral spinal fluid |

| CVD | cardiovascular disease |

| FVC | fruit and vegetable consumption |

| FVI | fruit and vegetable intake |

| HPLC | high performance liquid chromatography |

| mg | milligram |

| MS | mass spectrometry |

| NFkB | nuclear factor kappa B |

| Nrf2 | nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 |

| OS | oxidative stress |

| RAE | retinol activity equivalent |

| ROS | reactive oxygen species |

| RS | reflective spectroscopy |

| RRS | resonance Raman spectroscopy |

| SCS | skin carotenoid score |

| SORS | spatially offset Raman spectroscopy |

| SR-B1 | scavenger receptor class B member 1 |

| SRS | stimulated Raman scattering spectroscopy |

| T2D | type 2 diabetes |

| TNF | tumor necrosis factor |

| USDA | United States Department of Agriculture |

| UV | ultraviolet |

References

- United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs. World population prospect 2022: release note about major differences in total population estimates for mid-2021 between 2019 and 2022 revisions; Population Division: New York, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Garmany, A.; Terzic, A. Global health span-lifespan gaps among 183 world health organization member states. JAMA Network Open 2024, 7, e2450241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Attia, P. The Long Game. In Outlive, the science & art of longevity; Harmony: New York, NY, 2023; p. 10. [Google Scholar]

- Rippe, J.M. Lifestyle Medicine: The health promoting power of daily habits and practices. Am J Lifestyle Med. 2018, 12, 499–512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Knaggs, H.; Lephart, E.D. Enhancing skin anti-aging through healthy lifestyle factors. Cosmetics 2023, 10, 142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harman, D. Free radical theory of aging. Mutat Res. 1992, 275, 257–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alegria-Torres, J.A.; Baccarelli, A.; Bollati, V. Epigenetics and lifestyle. Epigenetics 2011, 3, 267–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Franceschi, C.; Garagnani, P.; Parini, P.; Giuliani, C.; Santoro, A. Inflammaging: a new immune-metabolic viewpoint for age-related diseases. Nature Rev Endocrinol. 2018, 14, 576–590. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Zhang, Z.; Ren, Y.; Wang, Y.; Fang, J.; Yue, H.; Ma, S.; Guan, F. Aging and age-related diseases: from mechanisms to therapeutic strategies. Biogerontology 2021, 22, 165–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, K. Studies on free radicals, antioxidants, and co-factors. Clin Interventions Aging 2007, 2, 219–236. [Google Scholar]

- Liguori, I.; Russo, G.; Curcio, F.; Bulli, G.; Aran, L.; Della-Morte, D.; Gargiulo, G.; Testa, G.; Cacciatore, F.; Bonaduce, D.; Abete, P. Oxidative stress, aging and disease. Clin Interventions Aging 2018, 13, 757–772. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandimali, N.; Bak, S.G.; Park, E.H.; Lim, H.-J.; Won, Y.-S.; Kim, E.-K.; Park, S.-I.; Lee, S.J. Free radicals and their impact on health and antioxidant defenses: a review. Cell Death Discovery 2025, 11, 19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kassis, A.; Fochot, M.-C.; Horcajada, M.-N.; Horstman, A.M.H.; Duncan, P.; Bergonzelli, G.; Preitner, N.; Zimmermann, D.; Bosco, N.; Vidal, K.; et al. Nutritional and lifestyle management of the aging journey: A narrative review. Front Nutr. 2023, 9, 1087505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tessier, A.-J.; Wang, F.; Korat, A.A.; Eliassen, A.H.; Chavarro, J.; Grodstein, F.; Li, J.; Liang, L.; Willett, W.C.; Sun, Q.; Stampher, M.J.; Hu FBGuasch-Ferre, M. Optimal dietary patterns for healthy aging. Nat Med. 2025, 31, 1644–1652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roa, A.V.; Rao, L.G. Carotenoids and human health. Pharmacol Res. 2007, 55, 207–216. [Google Scholar]

- Crupi, P.; Faienza, M.F.; Naeem, M.Y.; Corbo, F.; Clodoveo, M.L.; Muraglia, M. Overview of the potential beneficial effects of carotenoids on consumer health and well-being. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bakac, E.R.; Percin, E.; Gunes-Bayir, A.; Dadak, A. A narrative review: The effects and importance of carotenoids on aging and aging-related diseases. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 15199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qi, X.; Wang, X.; Cheng, L.; Li, Y.; Dang, K.; Yang, S.; Wang, Y.; Zhou, R.; Zhang, C.; Li, Y. Dietary carotenoids intakes and biological aging among US adults, NHANES 1999-2018. Nutr J. 2025, 24, 9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madore, M.; Hwang, J.-E.; Park, J.-Y.; Ahn, S.; Joung, H.; Chun, O.K. A narrative review of factors associated with skin carotenoid levels. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Terao, J. Revisiting carotenoids as dietary antioxidants for human health and disease prevention. Food Function. 2023, 14, 7799–7824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toti, E.; Chen, C.-Y.O.; Palmery, M.; Valencia, D.V.; Peluso, I. Non-provitamin A and provitamin A carotenoids as immunomodulators: Recommended dietary allowance, therapeutic index, or personalized nutrition? Oxidative Med Cell Longevity 2018, 4637861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- USDA. National Agriculture Library, Food Composition, nal.usda.gov/human-nutrition-and-food-safety/food-composition Accessed 3 JUN 2025.

- National Institutes of Health (USA) Office of Dietary Supplements, Vitamin A and Carotenoids https://ods.od.nih.gov/factsheets/VitaminA-Consumer/#:~:text=Vitamin%20A%20is%20a%20fat,Teen%20females%2014%E2%80%9318%20years Accessed 3 JUN 2025.

- Mrowicka, M.; Mrowicki, J.; Kucharska, E.; Majsterek, I. Lutein and zeaxanthin and their roles in age-related macular degeneration- Neurodegenerative disease. Nutrients 2022, 14, 827. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Munteanu, I.G.; Apetrei, C. Analytical methods used in determining antioxidant activity: A review. Int J Mol Sci. 2021, 22, 3380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silvertrini, A.; Meucci, E.; Ricerca, B.M.; Mancini, A. Total antioxidant capacity: Biochemical aspects and clinical significance. Int J Mol Sci. 2023, 24, 10978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tufail, T.; Ain, H.B.U.; Noreen, S.; Ikram, A.; Arshad, M.T.; Abdullahi, M.A. Nutritional benefits of lycopene and beta-carotene: A comprehensive review. Food Sci Nutr. 2024, 12, 8715–8741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopez-Valverde, N.; Lopez-Valverde, A.; de Sousa, B.M.; Blanco Rueda, J.A. Systematic review and meta-analysis of the antioxidant capacity of lycopene in the treatment of periodontal disease. Front Bioeng Biotechnol. 2024, 11, 1309851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E-Reay, M.A.; Ibrahim, G.E.; Eldahshan, O.A. Lycopene and lutein: A review for their chemistry and medicinal uses. J Pharmacognosy Phytochem. 2013, 2, 245–254. [Google Scholar]

- Shafe, M.O.; Gunede, N.M.; Nyakudya, T.T.; Chivandi, E. Lycopene: A potent antioxidant with multiple health benefits. J Nutr Metab. 2024, 6252426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Joshi, B.; Kar, S.K.; Yadav, P.K.; Yadav, S.; Shrestha, L.; Bera, T.K. Therapeutic and medicinal uses of lycopene: a systematic review. Int J Res Med Sci. 2020, 8, 1195–1201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leh, H.E.; Lee, L.K. Lycopene: a potent antioxidant for the amelioration of type II diabetes mellitus. Molecules 2022, 27, 2335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bruno, R.R.; Rosa, F.C.; Nahas, P.C.; de Branco, F.M.S.; de Oliveira, E.P. Serum α-carotene, but not other antioxidants, is positively associated with muscle strength in older adults: NHANES 2001-2002. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omedilla-Alonso, B.; Rodriguez-Rodriguez, E.; Beltran-de-Miguel, B.; Estevez-Santiago, R. Dietary β-cryptoxanthin and α-carotene have greater apparent bioavailability than β-carotene in subjects from countries with different dietary patterns. Nutrients 2020, 12, 2639. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Obana, A.; Gohto, Y.; Nakazawa, R.; Moriyama, T.; Gellermann, W.; Berstein, P.S. Effect of an antioxidant supplement containing high dose lutein and zeaxanthin on macular pigment and skin carotenoid levels. Sci Reports 2020, 10, 10262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rodriguez-Amaya, D.B. Carotenes and xanthophylls as antioxidants. In Handbook of Antioxidants for Food Preservation; Woodhead Publishing: Cambridge, UK, 2015; pp. 17–52. [Google Scholar]

- Rivera-Madrid, R.; Caballo-Uicab, V.M.; Cardenas-Conejo, Y.; Aguliar-Espinosa, M.; Siva, R. Chapter 1, Overview of carotenoids and beneficial effects on human health. In Carotenoids: Properties, Processing and Applications; Elsevier: London, UK, 2025; pp. 1–40. [Google Scholar]

- Hammad, M.; Raftari, M.; Cesario, R.; Salma, R.; Godoy, P.; Emami, S.N.; Haghdoost, S. Roles of oxidative stress and Nrf2 signaling in pathogenic and non-pathogenic cells. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 1371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bufka, J.; Vankova, L.; Sykora, J.; Krizkova, V. Exploring carotenoids: Metabolism, antioxidants, and impacts on human health. J Funct Foods 2024, 118, 106284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arslansoy, N.; Fidan, O. Carotenoids and their antioxidant power. In The Power of Antioxidants – Unleashing Nature’s Defense Against Oxidative Stress; Barros, A.N., Abraao, A.C., Eds.; Intech, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Betteridge, D.J. What is oxidative stress? Metabolism 2000, 49, 3–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aune, D.; Keum, N.; Giovannucci, E.; Fadnes, L.T.; Boffetta, P. Greenwood DC. Dietary intake and blood concentrations of antioxidants and the risk of cardiovascular disease, total cancer, and all-cause mortality: a systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Am J Clin Nutr. 2018, 108, 1069–1091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, T. Carotenoids and markers of oxidative stress in human observational studies and intervention trials: implications for chronic diseases. Antioxidants 2019, 8, 179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, T.; Bonet, M.L.; Borel, P.; Keijer, J.; Landrier, J.F.; Milisav, I. Mechanistic aspects of carotenoid health benefits – where are we now? Nutr Res Rev. 2021, 34, 267–302. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahashi, Y.; Goto, A.; Takachi, R.; Ishihara, J.; Kito, K.; Kanehara, R.; Yamaji, T.; Iwasaki, M.; Inoue, M.; Tsugane, S.; Sawada, N. Inverse association between fruit and vegetable intake and all-cause mortality: Japan public health center-based prospective study. J Nutr. 2022, 152, 2245–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohm, V.; Lietz, G.; Olmedilla-Alonso, B.; Phelan, D.; Reboul, E.; Banati, D.; Borel, P.; Corte-Real, J.; de Lera, J.-F.; Desmarchelier, C. From carotenoid intake to carotenoid blood and tissue concentrations-implications for dietary intake recommendations. Nutr Rev. 2021, 79, 544–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fekete M, Csipo T, Fazekas-Pongor V, Fehar A, Szarvas Z, Kaposvari C, Horvath K, Lehoczki A, Tarantini S, Varga JT, The effectiveness of supplementation with key vitamins, minerals, antioxidants and specific nutritional supplements in COPD- A review. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2741. [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; He, C.; Yu, W.; Ma, L.; Gou, S.; Fu, P. Association between dietary carotenoid and biological age acceleration: insights from NHANES 2009-2018. Biogerontology 2024, 26, 24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahn, Y.J.; Kim, H. Lutein as a modulator of oxidative stress-mediated inflammatory diseases. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ademowo, O.S.; Oyedode, O.; Edward, R.; Conway, M.E.; Griffiths, H.R.; Dias, I.H.K. Effects of carotenoids on mitochondrial dysfunction. Biochem Soc Transactions 2024, 52, 65–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciccone, M.M.; Cortese, F.; Gesualdo, M.; Carbonara, S.; Zito, A.; Ricci, G.; De Pascalis, F.; Scicchitano, P.; Riccioni, G. Dietary intake of carotenoids and their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects in cardiovascular care. Mediators of Inflammation 2013, 782137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, M.; Tang, R.; Zhou, R.; Qian, Y.; Di, D. The protective effect of serum carotenoids on cardiovascular disease: a cross-sectional study form the general US adult population. Front Nutr. 2023, 10, 1154239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sumalla-Cano, S.; Eguren-Garcia, I.; Lasarte-Garcia, A.; Prola, T.A.; Martinez-Diaz, R.; Elio, I. Carotenoids intake and cardiovascular prevention: A systematic review. Nutrients 2024, 16, 3859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Obana, A.; Nakamura, M.; Miura, A.; Nozue, M.; Muto, S.; Asaoka, R. Association between atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease score and skin carotenoids levels estimated via refraction spectroscopy in the Japanese population: a cross-sectional study. Sci Reports 2024, 14, 12173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gammone, M.A.; Riccioni, G.; D’Orazio, N. Carotenoids: potential allies of cardiovascular health? Food Nutr Res. 2015, 59, 26762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bungau, S.; Abdel-Daim, M.M.; Tit, D.M.; Ghanem, E.; Sato, S.; Maruyama-Inoue, M.; Yamane, S.; Kadonosono, K. Health benefits of polyphenols and carotenoids in age-related eye diseases. Oxidative Med Cell Longevity 2019, 9783429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, D.; Thrimawithana, T.; Piva, T.J.; Grando, D.; Huynh, T. Benefits of plant carotenoids against age-related macular degeneration. J Funct Foods 2023, 106, 105597. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lem, D.W.; Davey, P.G.; Gierhart, D.L.; Rosen, R.B. A systematic review of carotenoids in the management of age-related macular degeneration. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Arunkmar, R.; Gorusupudi, A.; Berstein, P.S. The macular carotenoids: A biochemical overview. Biochim Biophys Acata Mol Cell Lipids 2020, 1865, 158617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, E.Y.; Clemons, T.E.; Agron, E.; Dormalpally, A.; Keenan, E.D.L.; Vitale, S.; Weber, C.; Smith, D.C.; Christen, W. Long-term outcomes of adding lutein/zeaxanthin and omega-3 fatty acids to the AREDS supplements on age-related macular degeneration progression: AREDS2 report 28. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022, 140, 692–698. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fathalipour, M.; Fathalipour, H.; Safa, O.; Nowrouzisoharbi, P.; Mikhani, H.; Hassanipour, S. The therapeutic role of carotenoids in diabetic retinopathy: A systematic review. Diabetes Metab Snydr Obes Targets Ther. 2020, 13, 2347–2358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darvin, M.E.; Sterry, W.; Lademan, J.; Vergou, T. The role of carotenoids in human skin. Molecules 2011, 16, 10491–10506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zerres, S.; Stahl, W. Carotenoids in human skin. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) – Molecular and Cellular Biology 2020, 1865, 158588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michalak, M. Plant-derived antioxidants: Significance in skin health and the ageing process. Int J Mol Sci. 2022, 23, 585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Darvin, M.E.; Lademan, J.; von Hagen Jorg Lohan, S.B.; Kolmar, H.; Meinke, M.C.; Jung, S. Carotenoids in human skin in vivo: Antioxidant and photo-protectant role against external and internal stressors. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metibemu, D.S.; Ogungbe, I.V. Carotenoids in drug discovery and medicine: Pathways and molecular targets implicated in human disease. Molecules 2022, 27, 6005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madore, M.P.; Hwang, J.-E.; Park, J.-Y.; Ahn, S.; Joung, H. A narrative review of factors associated with skin carotenoid levels. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baswan, S.M.; Klosner, A.E.; Weir, C.; Salter-Venzon, D.; Gellenbeck, K.W.; Leverett, J.; Krutmann, J. Role of ingestible carotenoids in skin protection: A review of clinical evidence. Photodermatol Photoimmunol Photomed. 2012, 37, 490–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bavarsad, N.; Mapar, M.A.; Safaezadeh, M.; Latiff, S.M. A double-blind, placebo-controlled randomized trial of skin-lightening cream containing lycopene and wheat bran extract on melasma. J Cosmet Dermatol. 2020, 20, 1795–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhou, Q.; Qi, Y.; Chen, X.; Deng, J.; Zhang, Y. The effect of tomato and lycopene on clinical characteristics and molecular markers of UV-induced skin deterioration: A systematic review and meta-analysis of intervention trials. Critical Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2024, 64, 6198–6217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Varghee, R.; Emerson, A.; Vannier, B.; Doss, C.G.P.; Priyadharshini, R.; Efferth, T.; Ramamoorthy, S. Substantial effects of carotenoids on skin health: A mechanistic perspective. Phytother Res. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stevens, G.A.; Bennett, J.; Hennocq, Q.; Lu, Y.; De-Regil, L.M.; Rogers, L.; Danaei, G.; Li, G.; White, R.A.; Flaxman, S.R.; Oehrle, S.-P.; Finucane, M.M.; Guerrero, R.; Bhutta, Z.A.; Then-Paulino, A.; Fawzi, W.; Black, R.E.; Ezzati, M. Trends and mortality effects of vitamin A deficiency in children in 138 low-income and middle-income countries between 1991-2013: a pooled analysis of population-based surveys. Lance Glob Health 2015, 3, e528–e536. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hughes, D.A. Effects of carotenoids on human immune function. Pro Nutr Soc. 1999, 58, 713–718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bas, T.G. Bioactivity and bioavailability of carotenoids applied in human health: Technological advances and innovation. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 7603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anjani, G.; Ayustaningwarno, F.; Eviana, R. Critical review on the immunomodulatory activities of carrot’s β-carotene and other bioactive compounds. J Funct Foods. 2022, 99, 105303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chew, B.P.; Park, J.S. Cartenoids action in the immune response. J Nutr. 2004, 134, 257S–261S. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bohn, T.; Balbuena, E.; Ulus, H.; Iddir MWang, G.; Crook, N.; Eroglu, A. Carotenoids in health as studies by omics-related endpoints. Adv Nutr. 2023, 14, 1538–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.S.; Meydani, S.N.; Leka, L.; Wu, D. Fotouhi N, Meydani M, Hennekens CH, Gaziano JM. Natural killer cell activity in elderly men is enhance by beta-carotene supplementation. Am J Clin Nutr. 1996, 64, 772–777. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Santos, M.S.; Gaziano, J.M.; Leka, L.S.; Beharka, A.A.; Hennekens, C.H.; Meydani, S.N. Beta-carotene-induced enhancement of natural killer cell activity in elderly men: an investigation of the role of cytokines. Am J Clin Nutr. 1998, 68, 164–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kramer, T.R.; Burri, B.j. Modulated mitogenic proliferative responsiveness of lymphocytes in whole-blood cultures after low-carotene diet and mixed-carotenoid supplementation in women. Am J Clin Nutr. 1997, 65, 871–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kulczynski, B.; Sidor ABrzozowska, A.; Gramza-Michlowska, A. The role of carotenoids in bone health – A narrative review. Nutrition 2024, 119, 112306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regu, G.M.; Kim, H.; Kim, Y.J.; Paek, J.E.; Lee, G.; Chang, N.; Kwon, O. Association between dietary carotenoid intake and bone mineral density in Korean adults aged 30-75 years using data from the fourth and fifth Korean national health and nutrition examination surveys (2008-2011). Nutrients 2017, 16, 1025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kan, B.; Guo, D.; Yuan, B.; Vuong, A.M.; Jiang, D.; Zhang, M.; Cheng, H.; Zhao, Q.; Li, B.; Feng, L.; Huang, F.; Wang, N.; Shen, X.; Yang, S. Dietary carotenoids intake and osteoporosis: the national health and nutrition examination survey, 2005-2018. Arch Osteoporos. 2021, 17, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhen, Y.; Zhou, W.; Zhang, J.; Lan, T.; Zhang, R. Association between dietary carotenoid intake and vertebral fracture in people aged 50 years and older: a study based on the national health and nutrition examination survey. Arch Osteoporos. 2025, 20, 39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahni, S.; Hannan, M.T.; Blumberg, J.; Cupples, L.A.; Kiel, D.P.; Tucker, K.L. Protective effect of total carotenoid and lycopene intake on risk of hip fracture: A 17-year follow-up from the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. J Bone Mineral Res. 2009, 24, 1086–1095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahni, S.; Hannan, M.T.; Blumberg, J. Cupples L, Kiel DP, Tucker K. Inverse association of carotenoid intakes with 4-year change in bone mineral density in elderly men and women: the Framingham Osteoporosis Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2009, 89, 416–424. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhatt, T.; Patel, K. Carotenoids: Potent to Prevent Diseases Review. Nat Prod Bioprospecting 2020, 10, 109–117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davinelli, S.; Ali, S.; Solfrizzi, V.; Scapagnini, G.; Corbi, G. Carotenoids and cognitive outcomes: A meta-analysis of randomized intervention trials. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Dhana, K.; Furtado, J.D.; Agarwal, P.; Aggarwal, N.T.; Tangney, C.; Laranjo, V.; Barnes, L.I.; Sacks, F.M. Higher circulating α-carotene was associated with better cognitive function: an evaluation among the MIND trial participants. J Nutr Sci. 2021, 10, e64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, L.; Zhao, T.; Zhy, X.; Jiang, Q. Low blood carotenoid status in dementia and mild cognitive impairment: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Geriatrics. 2023, 23, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Flieger, J.; Forma, A.; Flieger, W.; Flieger, M.; Gawlik, P.J.; Dzierzynski, E.; Maciejewski, R.; Terensinski, G.; Baj, J. Carotenoid supplementation for alleviating the symptoms of Alzheimer’s disease. Int J Mol Sci. 2024, 25, 8982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christimann, G.; Rocha, G.; Sattler, J.A.G. Bioactive compounds and dietary patterns in Alzheimer's disease. J Alzheimer's Dis. 2025, 104, 597–610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Govindaswamy, B.; Stephen, K.N.; Keerthana, S.; Perumal, S.; Thirumurugan, M. Recent advances on therapeutic mechanism and potential of flavonoids and carotenoids: A focus on Alzheimer's and Parkinson’s disease. In Bioactive Ingredients for Healthcare Industry; Lahiri, D., Nag, M., Bhattacharya, D., Pati, S., Sarkar, T., Eds.; Springer: Singapore, 2025; Volume 2, pp. 75–107. [Google Scholar]

- Wilson, D.M.I.I.I.; Cookson, M.R.; Den Bosch, L.V.; Zetterberg, H.; Holtzman, D.M.; Dewachter, I. Hallmarks of neurodegenerative diseases. Cell 2022, 186, 693–714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kabir, M.T.; Rahman, M.H.; Shah, M.; Jamiruddin, M.R.; Basak, D.; Al-Harrasi, A.; Bhatia, S.; Ashraf, G.M.; Najda, A.; El-Kott, A.F.; Mohamed, H.R.H.; Al-Malky, H.; Germoush, M.O.; Altyar, A.E.; Alwafai, E.B.; Ghaboura, N.; Abdel-Daim, M.M. Therapeutic promise of carotenoids as antioxidants and anti-inflammatory agents in neurodegenerative disorders. Biomed Pharmacother. 2022, 146, 112610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manochkumar, J.; Doss, C.G.P.; El-Seedi, H.R.; Efferth, T.; Ramaoorthy, S. The neuroprotective potential of carotenoids in vitro and in vivo. Phytomedicine 2021, 91, 153676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gandla, K.; Babu, A.K.; Unnisa, A.; Sharma, I.; Singh, L.P.; Haque, M.A.; Dashputre, N.L.; Baig, S.; Siddiqui, F.A.; Khandaker, M.U.; Almujally, A.; Tamam, N.; Sulieman, A.; Khan, S.L.; Emran, T.B. Carotenoids: Role in neurodegenerative diseases remediation. Brain Sci 2023, 13, 457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, C.; Chen, H.; Wang, Y.; Schneider, J.A.; Willett, W.C.; Morris, M.C. Dietary carotenoids related to risk of incident Alzhemier’s dementia (AD) and brain AD neuropathy: a community-based cohort of older adults. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021, 113, 200–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bej, E.; Cesare, P.; d’Angelo, M.; Volpe, A.R.; Castelli, V. Neuronal cell rearrangement during aging: Antioxidant compounds as a potential therapeutic approach. Cells. 2024, 13, 1945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kudo, J.; Watanabe, K.; Sasaki, M.; Ushida, Y.; Matsuzaka, M.; Kakeda, S. Serum carotenoids concentrations are associated with enlarged choroid plexus, lateral ventricular volume, and perivascular spaces on magnetic resonance imaging: A large cohort study. Academic Radiology in press. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gao, Y.; Liu, K.; Zhu, J. Glymphatic system: an emerging therapeutic approach for neurological disorders. Front Mol Neurosci. 2023, 16, 1138769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Crowe-White, K.M.; Phillips, T.A.; Ellis, A.C. Lycopene and cognitive function. J Nutr Sci. 2019, 8, e20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, N.-W.; Yin, Z.-L.; Lin, R.; Fan, Z.-L.; Chen, S.-J.; Zhu, Y.-M.; Zhao, X.-Z. Possible mechanisms of lycopene amelioration of learning and memory impairment in rats with vascular dementia. Neural Regen Res. 2020, 15, 332–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, J.; Shen, Y.; Li, M.; Li, T.; Shi, D.; Shi, D.; Lu, S.; Qiu, F.; Wu, Z. Lycopene treatment attenuates D-galactose-induced cognitive decline by enhancing mitochondrial function and improving insulin signaling in the brains of female CD-1 mice. J Nutr Biochem. 2023, 118, 109361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iyer, S.; Bhat, I.; Sheshappa, M.B. Luetin and the underlying neuroprotective promise against neurodegenerative diseases. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2024, 68, e2300409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayakanthan, M.; Manochkumar, J.; Efferth, T.; Ramamoorthy, S. Lutein, a versatile carotenoid: Insight on neuroprotective potential and recent advances. Phytomedicine 2024, 135, 156185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wingo, T.S.; Liu, Y.; Gerasimov, E.S.; Vattathil, S.M.; Wynne, M.E.; Liu, J.; Lori, A.; Faundez, V.; Bennett, D.A.; Seyfried, N.T.; Levey, A.I.; Wingo, A.P. Shared mechanisms across the major psychiatric and neurodegenerative diseases. Nature Communications. 2022, 13, 4314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anderson, E. Crawford CM, Fava M, Ingelfinger J, Nikayin S. Sanacora G. Depression – understanding, identifying, and diagnosing. N Engl Med. 2024, 390, e41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kulkarni, J. Why depression in women is so misunderstood. Nature 2022, 608, S54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McCarron, R.M.; Shapiro, B. Rawles J, Luo J. Depression. Ann Intern Med. 2021, 174, ITC65-80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, H.; Yang, T.; Sun, J.; Zhang, D. Associations between dietary carotenoid intakes and the risk of depressive symptoms. Food Nutr Res. 2020, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardinet, J.; Pouchieu, C.; Chuy, V.; Helmer, C.; Etheve, S.; Gaudout, D.; Samieri, C.; Berr, C.; Delcourt, C.; Cougnard-Gregoire, A.; Feart, C. Plasma carotenoids and risk of depressive symptomatology in a population-based cohort of older adults. J Affective Disorders 2023, 339, 615–623. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, Q.; Xue, F.; Li, Z.; Li, X.; Ai, L.; Jin, M.; Xie, M.; Yu, Y. Dietary intake of carotenoids and risk of depressive symptoms: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Antioxidants 2022, 11, 2205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rasmus, P.; Kozlowska, E. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects of carotenoids in mood disorders: An overview. Antioxidants 2023, 12, 676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, C.; Fang, M.-S. Association of dietary antioxidant intake with depressive risk and all-cause mortality in people with prediabetes. Sci Reports 2024, 14, 20009. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W.; Cheng, Z.; Lin, H.; Fu, F.; Zhan, Z. Serum carotenoid levels inversely correlate with depression symptoms among adults: Insights from NHANES data. J Affective Disorders 2024, 362, 869–876. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, J.-H.; Zhong, W.-W.; Tan, Y.-L.; Zhuo, L.; Luo, G.-Z. Association of dietary and plasma lutein + zeaxanthin with depression in US adults: findings from NHANES. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2025, 34, 153–164. [Google Scholar]

- Li, X.; Lan, Y. Association between higher dietary lycopene intake and reduced depression risk among American adults: evidence from NHANES 2007-2016. Front Nutr. 2025, 12, 1538396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yen, C.-H.; Chang, P.-S.; Ghiu, C.-J.; Huang, Y.-Y.; Lin, P.-T. β-Carotene status is associated with inflammation and two components of metabolic syndrome in patients with and without osteoarthritis. Nutrients 2021, 12, 2280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takayanagi, Y.; Obana, A.; Muto, S.; Asaoka, R.; Tanito, M.; Ermakov, I.V.; Bernstein, P.S.; Gellermann, W. Relationships between skin carotenoid levels and metabolic syndrome. Antioxidants 2021, 11, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kimura, Y.; Hata, J.; Shibata, M.; Honda, T.; Sakata, S.; Furuta, Y.; Oishi, E.; Kitazono, T.; Ninomiya, T. Skin carotenoid score and metabolic syndrome in general Japanese population: the Hisayama study. Internat J Obesity 2024, 48, 1465–1471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Q.; Fan, Z.; Yao, F.; Zhao, X.; Jiang MYang, M.; Mao, M.; Yang, C. Association of dietary and circulating antioxidant vitamins with metabolic syndrome: an observational and Mendelian randomization study. Front Endocrinol. 2024, 15, 1446719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortega-Regules, A.E.; Martinez-Thomas, J.A.; Schurenkamper-Carrillo, K.; de Parrodi, C.A.; Lopez-Mena, E.R.; Mejia-Mendez, J.L.; Lozada-Ramirez, J.D. Recent advances in the therapeutic potential of carotenoids in preventing and managing metabolic disorders. Plants 2024, 13, 1584. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bouayed, J.; Vahid, F. Carotenoid pattern intake and relation to metabolic status, risk and syndrome, and its components-divergent findings from the ORISCAV-LUX-2 survey. British J Nutr. 2024, 132, 50–66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marceline, G.; Machate, D.J.; de Cassia Freitas, K.; Hiane, P.A.; Rodrigues Maldonade, I.; Pott, A.; Asato, M.A.; Candido, C.J.; de Cassia Avellaneda Guimaraes, R. β-Carotene: Preventive role for type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity: A review. Molecules 2020, 25, 5803. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.-W.; Sun, Z.-H.; Tong, W.-W.; Yang, K.; Guo Kpq Liu, G.; Pan, A. Dietary intake and circulating concentrations of carotenoids and risk of type 2 diabetes: A dose-response meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Adv Nutr. 2021, 12, 1723–1733. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leh, H.E.; Sopian, M.M.; Abu Bakar, M.H.; Lee, L.K. The role of lycopene for the amelioration of glycaemic status and peripheral antioxidant capacity among the type 2 diabetes patients: a case-control study. Ann Med. 2021, 53, 1060–1066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coronel, J.; Pinos, I.; Amengual, J. β-Carotene in obesity research: Technical considerations and current status of the field. Nutrients 2019, 11, 842. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anzar, C.A.; Joseph, M.V.; Vadiraj, S.R.; Prasad, C.P.; Eranimose, B.; Jagadeesh, S. Safety assessment of lutein and zeaxanthin supplementation and its effects on blood glucose levels, kidney functions, liver functions, and bone health – randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled clinical study. MedRxiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mounien, L.; Tourniaire, F.; Landrier, J.F. Anti-obesity effect of carotenoids: Direct impact on adipose tissue and adipose tissue-driven indirect effects. Nutrients 2019, 11, 1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, N.; Yan, S.; Guo, Y.; Wang, H.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Hi, W.; Li, B.; Cui, W. The association between carotenoids and subjects with overweight or obesity: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Food Funct. 2021, 12, 4768–4782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hahemi, D.; Fard, M.V.; Mohammadhasani, K.; Barati MNattagh-Eshtivani, E. Carotenoids improve obesity and fatty liver disease via gut microbiome: A narrative review. Food Sci Nutr. 2025, 13, e70092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eroglu, A.; Al’ Abr, A.L.; Kopec, R.E.; Crook, N.; Bohn, T. Carotenoids and their health benefits as derived via interactions with gut microbiota. Adv. Nutr. 2023, 14, 238–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, K.; Haddad, E.N.; Sugino, K.Y.; Vevang, K.R.; Peterson, L.A.; Korathar, R.; Gross, M.D.; Kerver, J.M.; Comstock, S.S. Dietary and plasma carotenoids are positively associated with alpha diversity in the fetal microbiota of pregnant women. J Food Sci. 2021, 86, 602–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rocha, H.R.; Coelho, M.C.; Gomes, A.M.; Pintado, M.E. Carotenoids diet: Digestion, gut microbiota modulation, and inflammatory diseases. Nutrients 2023, 15, 2265. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meneguelli, T.S.; Mishima, M.D.V.; Hermsdorff, H.H.M.; Martino, H.S.D.; Bressan, J.; Tako, E. Effect of carotenoids on gut health and inflammatory status: A systematic review of in vivo animal studies. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2024, 64, 11206–11221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bernabeu, M.; Gharibzahedi, S.M.T.; Ganaie, A.A.; Mach, M.A.; Dar, B.N.; CAstagnini, J.M.; Garcia-Bonillo, C.; Melendez-Martinez, A.J.; Altintas, Z.; Barba, F.J. The potential modulation of gut microbiota and oxidative stress by dietary carotenoid pigments. Crit Rev Food Sci Nutr. 2024, 64, 12555–12573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, S.; Mukherjee, R.; Gaur, P.; Leal, E.; Lyu, X.; Ahmad, S.; Puri, P.; Chang, C.-M.; Raj, V.S.; Pandey, R.P. Unveiling roles of beneficial gut bacteria and optimal diets for health. Front Microbiol. 2025, 16, 1527755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tanaka, T.; Shnimizu, M.; Moriwaki, H. Cancer chemoprevention by carotenoids. Molecules 2012, 17, 3202–3242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rowles, J.L.; Erdman, J.W., Jr. Carotenoids and their role in cancer prevention. Biochim Biophys Acata Mol Cell Biol Lipids 2020, 1865, 158613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dulinska-Litewka, J.; Sharoni, Y.; Halubiec, P.; Lazarczyk, A.; Szafranski, O.; McCubrey Gasiorkiewicz, B.; Laidler, P.; Bohn, T. Recent progress in discovering the role of carotenoids and their metabolites in prostatic physiology and pathology with a focus on prostate cancer- A review- Part 1: Molecular mechanisms of carotenoid action. Antioxidants 2021, 10, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shafiq, M.A.; Gull, R.; Nazik, G. Dietary Carotenoids and their multifaceted roles in cancer prevention. J Health Rehab Res. 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baeza-Morales, A.; Medina-Garcia, M.; Martinez-Peinado, P.; Pascual-Garica, S.; Pujalte-Satorre, C.; Lopez-Jaen, A.B.; Martinez-Espinosa, R.M.; Sempere-Ortells, J.M. The antitumour mechanisms of carotenoids: A comprehensive review. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 1060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dehnavi, M.K.; Ebrahimpour-Koujan, S.; Lotfi, K.; Azadbakht, L. The association between circulating carotenoids and risk of breast cancer: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective studies. Adv Nutr. 2024, 15, 100135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shin, J. Song M-H, Oh J-W, Keum Y-S, Saini RK. Pro-oxidant actions of carotenoids in trigging apoptosis of cancer cells: A review of emerging evidence. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 532. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Belludi, A.S.; Verma, S.; Banthia, R.; Bhusari, P.; Parwani, S.; Kedia, S.; Saiprasad, S.V. Effect of lycopene in the treatment of periodontal disease: A clinical study. J Comp Dental Prac. 2013, 14, 1054–1059. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varela-Lopez, A.; Battino, M.; Bullon PQuiles, J.L. Dietary antioxidants for chronic periodontitis prevention and its treatment: a review on current evidences from animal and human studies. Ars Pharmaceutica 2015, 56, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najeeb, S.; Zafar, M.S.; Khurshid, Z.; Zohaib, S.; Almas, K. The role of nutrition in periodontal health: An update. Nutrients 2016, 8, 530. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Kathariya, R.; Bansal, S.; Singh, A.; Shahakar, D. Dietary antioxidants and their indispensable role in periodontal health. J Food Drug Analysis 2016, 24, 239–246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ebersole, J.L.; Lambert, J.; Bush, H.; Huja, P.E.; Basu, A. Serum nutrient levels and aging effects on periodontitis. Nutrients 2018, 10, 1986. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naruishi, K. Carotenoids and periodontal infection. Nutrients 2020, 12, 269. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, F.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Y. Association between carotenoid intake and periodontitis in diabetic patients. J Nutr Sci. 2024, 13, e11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaur, G.; Dhillon, S.; Aulakh, N. Lycopene and oral health: A comprehensive review. Med Res Pub. 2025. Available online: https://www.medicalandresearch.com/current_issue/2485#:~:text=Recent%20studies%20suggest%20that%20lycopene,dental%20hygiene%20and%20preventive%20dentistry (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Semba, R.D.; Varadhan, R.; Bartali, B.; Ferrucci, L.; Ricks, M.O.; Blaum, C.; Fried, L.P. Low serum carotenoids and development of severe walking disability among older women living in the community: the Women’s Health and Aging Study I. Age Ageing 2007, 36, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Semba, R.D.; Lauretani, F.; Ferrucci, L. Carotenoids as protection against sarcopenia in older adults. Arch Biochm Biophys. 2007, 458, 141–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lauretani, F.; Semba, R.D.; Bandinelli, S.; Dayhoff-Brannigan, M.; Giacomini, V.; Corsi, A.M.; Guralnik, J.M.; Ferrucci, L. Low plasma carotenoids and skeletal muscle strength decline over six years. J Gerontol A Biol Sci Med Sci. 2008, 63, 376–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeong, D.; Park, S.; Kim, H.; Kwon, O. Association of carotenoids concentrations in blood with physical performance in Korean adolescents: The 2018 national fitness award project. Nutrients 2020, 12, 1821. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Welch, A.A.; Jennings, A.; Kelaiditi, E.; Skinner, J.; Steves, C.J. Cross-sectional associations between dietary antioxidant vitamin C, E and carotenoids intakes and sarcopenia indices in women aged 18-79 years. Calcif Tissue Int. 2020, 206, 331–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sahni, S.; Dufour, A.B.; Fielding, R.A.; Newman, A.B.; Kiel, D.P.; Hannan, M.T.; Jacques, P.F. Total carotenoid intake is associated with reduced loss of grip strength and gait speed over time in adults: The Framingham Offspring Study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021, 113, 437–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartali, B.; Semba, R.D. Carotenoids and healthy aging: the fascination continues. Am J Clin Nutr. 2021, 113, 259–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Murphy, C.H.; Duggan, E.; Davis, J.; O’Halloran, A.M.; Knight, S.P.; Kenny, R.A.; McCarthy, S.N.; Romero-Ortuno, R. Plasma lutein and zeaxanthin concentrations associated with musculoskeletal health and incident frailty in The Irish Longitudinal Study on Aging (TILDA). Exp Geronotol. 2023, 171, 112013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tarshish, E.; Hermoni, K.; Muizzudin, N. Effect of Lumenato a tomato derived oral supplement on improving skin barrier strength. Skin Res Tech. 2023, 29, e13504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhuang, C.; Yuan, J.; Du, Y.; Zeng, J.; Sun, Y.; Wu, Y.; Gao, X.-H.; Chen, H.-D. Effects of oral carotenoids on oxidative stress: A systematic review and meta-analysis of studies in the recent 20 years. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 754707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ermakov, I.V.; Ermakova, M.; Sharifzadeh, M.; Gorusupudi, A.; Farnsworth, K.; Bernstein, P.S.; Stookey, J.; Evans, J.; Arana, T.; Tao-Lew, L.; Isman, C.; Clayton, A.; Obana, A.; Whigham, L.; Redelfs, A.H.; Jahns, L.; Gellerman, W. Optical assessment of skin carotenoid status as a biomarker of vegetable and fruit intake. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2018, 646, 46–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radtke, M.D.; Pitts, S.J.; Jahns, L.; Firnhaber, G.; Loofbourrow, B.M.; Zeng, A.; Scherr, R.E. Criterion-related validity of spectroscopy-based skin carotenoid measurements as a proxy for fruit and vegetable intake: A systematic review. Adv Nutr. 2020, 11, 1282–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radtke, M.D.; Poe, M.; Stookey, J.; Pitts, S.J.; Moran, N.E.; Landry, M.J.; Rubin, L.P.; Stage, V.C.; Scherr, R.E. Recommendations for the use of the Veggie Meter® for spectroscopy-based skin carotenoid measurements in the research setting. Res Method Study Design. 2021, 5, nzab104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radtke, M.; Pitts, S.J.; Jahns, L.; Firnhaber, G.; Loofbourrow, B.; Zeng, A.; Scherr, R. Examining the validity of spectroscopy-based skin carotenoid measurements as a proxy for fruit and vegetable consumption. Curr Dev Nutr. 2020, 4, nzaa041_029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, J.-E.; Park, J.-Y.; Jung, M.H.; Eom, K.; Moon, H.S.; Joung, H.; Kim, Y.J. Evaluation of a commercial device based on reflection spectroscopy as an alternative to resonance Ramman spectroscopy in measuring skin carotenoid levels: Randomized control trials. Sensors 2023, 23, 7654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasin, S.; Dev, D.A.; Swindle, T.; Sisson, S.B.; Pitts, S.J.; Purkait, T.; Clifton, S.C.; Dixon, J.; Stage, V.C. Systemic review of reflection spectroscopy-based skin carotenoid assessment in children. Nutrients 2023, 15, 1315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veggie Meter – Longevity Link Corporation, website. Available online: http://www.longevitylinkcorporation.com/ (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Obana A, Measurement of skin carotenoids and their association with diseases: A narrative review. BBA Mole Cell Biol Lipids 2025, 1870, 159612. [CrossRef]

- Ahn, S.; Hwang, J.-E.; Kim, Y.J.; Eom, K.; Jung, M.H.; Moon, H.S.; Han, D.; Park, J.M.; Oh, S.U.; Park, J.-H.; Joung, H. Examination of the utility of skin carotenoid status in estimating intakes of carotenoids and fruits and vegetables: A randomized, parallel-group, controlled feeding trial. Nutrition 2024, 119, 112304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Udensi, J.; Loughman, J.; Loskutova, E.; Byrne, H.J. Raman spectroscopy of carotenoid compounds for clinical applications- A review. Molecules 2022, 27, 9017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nu Skin RRS technology BioPhontic S3 Scanner website. Available online: https://www.nuskin.com/content/nuskin/en_US/products/pharmanex/scanner/s3_score.html (accessed on 21 June 2025).

- Sharifzadeh, M. Accurate quantification of carotenoids in human skin: Correcting for melanin and hemoglobin interference. Wor Jour Clin Der. 2025, 2, 01–12. [Google Scholar]

- Soulat, J.; Andueza, D.; Graulet, B.; Girard, C.L.; Labonne, C.; Ait-Kaddour, A.; Martin, B.; Ferlay, A. Foods. 2020, 9, 592. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Lassale, C.; Gaye, B. Addressing global micronutrient inadequacies: enhancing global data representation. Lancet 2024, 12, e1561–e1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y.-I.; Choi, Y.; Park, J. The role of continuous glucose monitoring in physical activity and nutrition management: perspectives on present and possible uses. Physical Activity Nutr. 2023, 27, 44–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klonoff, D.C.; Nguyen, K.T.; Xu, N.Y.; Gutierrez, A.; Espinoza, J.C.; Vidmar, A.P. Use of continuous glucose monitors by people without diabetes: An idea whose time has come? J. Diabetes Sci. Technol. 2023, 17, 1686–1697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ehrhardt, N.; Al Zaghal, E. Continuous glucose monitoring as a behavior modification tool. Clin Diabetes 2020, 38, 126–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kruas, W.E.; Janz, K.F.; Powell KECampbell, W.W.; Jakicic, J.M.; Troiano, R.P.; Sprow, K.; Torres, A.; Piercy, K.L. Daily step counts for measuring physical activity exposure and its relation to health. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019, 51, 1206–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluch, A.E.; Gabriel, K.P.; Fulton, J.E.; Lewis, C.E.; Schreiner, P.J.; Sternfeld, B.; Sidney, S.; Siddique, J.; Whitaker, K.M.; Carnethon, M.R. Steps per day and all-cause mortality in middle-aged adults in the coronary artier risk development in young adults study. JAMA Network Open 2021, 4, e21224516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- del Pozo Cruz, B.; Ahmadi, M.N.; Lee, I.-M.; Stamatakis, E. Prospective associations of daily step counts and intensity with cancer and cardiovascular disease incidence and mortality and all-cause mortality. JAMA Intern Med. 2022, 182, 1139–1148. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, R.; Sexis, A.; Masters, L.M.; Chanko, N.; Diaby, F.; Vieira, D.; Jean-Louis, G. Sleep tracking: A systematic review of the research using commercially available technology. Curr Sleep Med Res. 2019, 5, 156–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seid, A.; Fufa, D.D.; Biew, Z.W. The use of internet-based smartphone apps consistently improved consumer’s healthy eating behaviors: a systematic review of randomized controlled trials. Front Digital Health. 2024, 6, 1282570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Knaggs, H.; Hester, S.N.; Gibb, T.; Riggs, M.; Ferguson, S.; Major, R.; Fisk, N. Global, gender, and age variation in skin carotenoid scores (SCS) quantified by spectroscopy reflects a measure of health and wellness. 2025 10th International Conference on Health & Nutrition, Chicago, IL, USA, Integrative Nutrition. in press.

- Major, R.; Hester, S.; Gibb, T.; Riggs, M.; Ferguson, S.; Knaggs, H.; Fisk, N. The correlation between skin carotenoid scores and specific diet and lifestyle choices. 2025 10th International Conference on Health and Nutrition, Chicago, IL, USA, Integrative Nutrition. in press.

- Faffetti, E.; Mondino, E.; Di Baldassarre, G. COVID-19 vaccine hesitancy in Sweden and Italy: The role of trust in authorities. Scandinavian J Pub Health 2022, 50, 803–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stahl, W.; Heinrich, U.; Jungman, H.; von Laar, J.; Schietzel, M.; Sies, H.; Tronnier, H. Increased dermal carotenoids levels assessed by noninvasive reflection spectrophotometry correlate with serum levels in women ingesting betatene. Nutr Metab. 1998, 128, 903–907. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streker, M.; Proksch, E.; Kattenstroth, J.-C.; Poeggeler, B.; Lemmnitz, G. Comparative assessment of nutraceuticals for supporting skin health. Nutraceuticals 2025, 5, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shanaida, M.; Mykailenko, O.; Lysiuk, R.; Hudz Balwierz, R.; Shulhai, A.; Shapovalova, N.; Shanaida, V.; Bjorklund, G. Carotenoids for antiaging: Nutraceutical, pharmaceutical, and cosmeceutical applications. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babar, M.; Buzdar, J.A.; Zaheer, Z.; Nizam-ud-din, N.; Mustafa, G.; Khan, B.A.; Hanif, M.; Asghar, T.; Qadeer, A. Carotenoids as a nutraceutical and health-promoting dietary supplement for human and animals: an update review. Trad Med Res. 2025, 10, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ibrahim, M.; Singh, H.; Fahim, M.; Khan, S.; Khan, J.; Arun, J.K.; Mishra, A.K.; Virmani, T.; Sharma, A.; Kumar, G.; Gugulothu, D.; Chopra, S.; Chopra, H. Nutraceutical interventions for mitigating skin ageing: Analysis of mechanism and efficacy. Curr Pharm Design. 2025, 31, 2385–2401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hester, S.N.; Major, R.A.; Gibb, T.; Riggs, M.; Ferguson, S.; Fisk, N.; Knaggs, H. Use of spectroscopy to validate effects of a multivitamin on nutrient status. Am. Soc. Nutr. 2025, Orlando, Florida, USA, Curr Dev Nutr. 2025, in press.

- Black, H.S.; Boehm, F.; Edge, R.; Truscott, T.G. The benefits and risks of certain dietary carotenoids that exhibit both anti- and pro-oxidative mechanisms- A comprehensive review. Antioxidants 2020, 9, 264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Grand View Research. Carotenoids Market Size, Share & Trends Analysis Report By Product, By Application (Food, Supplements, Feed, Pharmaceuticals, Cosmetics), By Source, By Region, And Segment Forecasts, 2024 – 2030. https://www.grandviewresearch.com/industry-analysis/carotenoids-market. Accessed 20 JUN 2025.

- Harlem World, 3 March 2025. The future of wearable tech: From fitness trackers to smart clothing. https://www.harlemworldmagazine.com/the-future-of-wearable-tech-from-fitness-trackers-to-smart-clothing/#:~:text=The%20future%20of%20wearable%20tech%20is%20filled%20with%20exciting%20possibilities,we%20have%20yet%20to%20imagine. Accessed 20 JUN 2025.

- Kolasinac, S.M.; Pecinar, I.; Gajic, R.; Mutavizic, D.; Stevanovic, Z.P.D. Raman spectroscopy in the characterization of food carotenoids: Challenges and prospects. Foods 2025, 14, 953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ashokkumar, V.; Flora, G.; Sevannan, M.; Sripriya, R.; Chen, W.H.; Park, J.-H.; Banu, J.R.; Kumar, G. Technological advances in the production of carotenoids and their applications – A critical review. Bioscource Tech. 2023, 367, 128215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Budzianowska, A.; Banas, K.; Budzianowski, J.; Kikowsaka, M. Antioxidants to defend healthy and youthful skin – current trends and future directions in cosmetology. Applied Sci. 2025, 15, 2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzaal, M.; Imran, A.; Iqbal, S.S.; Nawaz, S.; Batool, A.; Abbasie, N.A.; Iftikhar, T.; Nawaz, R.; Ali, A.A.; Sharif, N.T.; Zahra, M. Potential microalgae-derived antioxidants as human health supplements nutritional evaluation and benefits. Alge BioTech Biomed Nutr Appl. 2025, 200, 131–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, S.; Dedha, A.; Gupta, M.M.; Singh, N.; Gautan, A.; Kumari, A. Green and sustainable technologies for extraction of carotenoids from natural sources: a comprehensive review. Preparative Biochem Biotech. 2025, 55, 245–277. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, J. Zhu Y, Liu J. Construction of nutrient delivery system for carotenoids and their antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities. Front. Nutr. 2025, 11, 1539429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valacchi, G.; Percorelli, A. Role of scavenger receptor B1 (SR-B1) in improving food benefits for human health. Annu Rev Food Sci Technol. 2025, 16, 403–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).