Submitted:

07 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

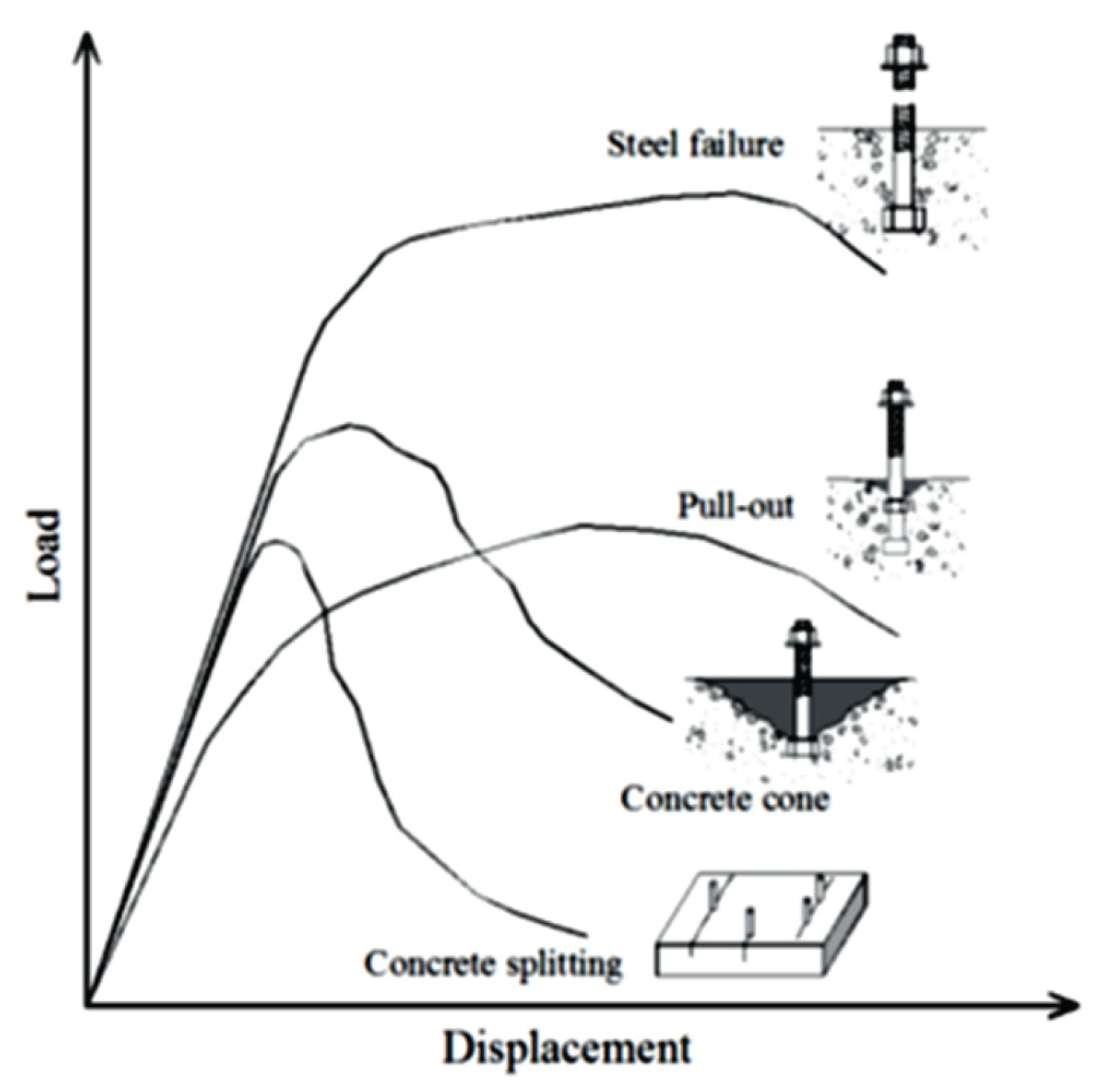

2. Factors Affecting the Anchorage Performance of Headed Anchors

2.1. Anchor Head Geometry and Bearing Capacity Ratio

2.2. Compressive Strength of Concrete

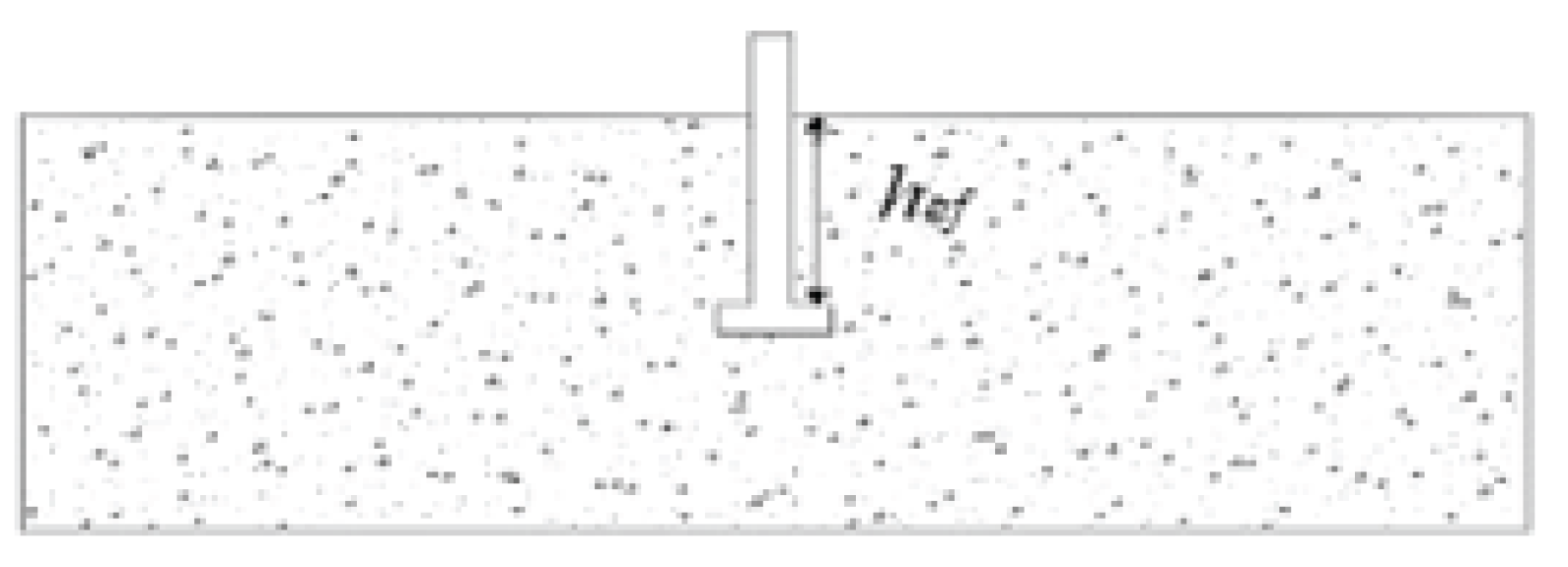

2.3. Embedment Depth

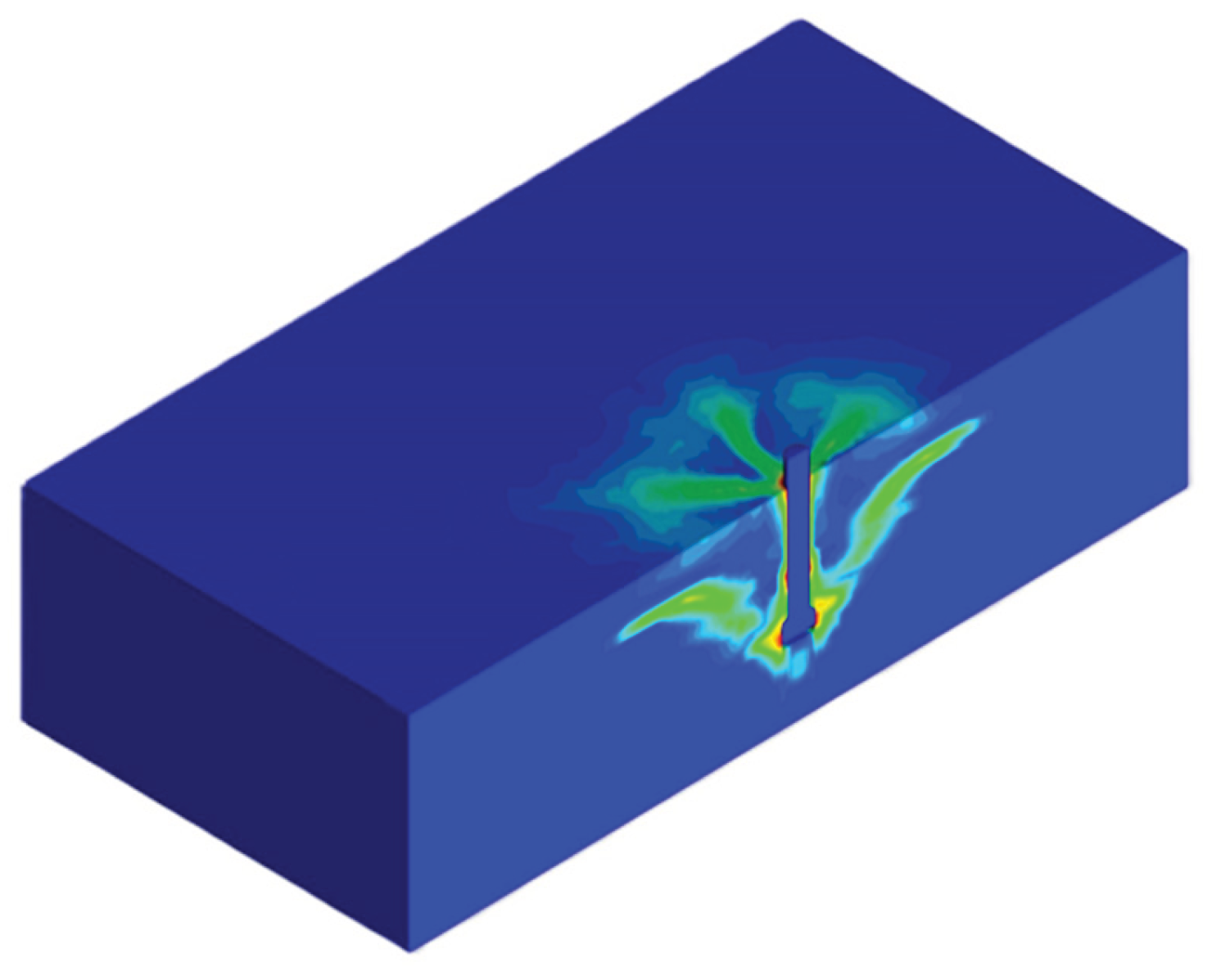

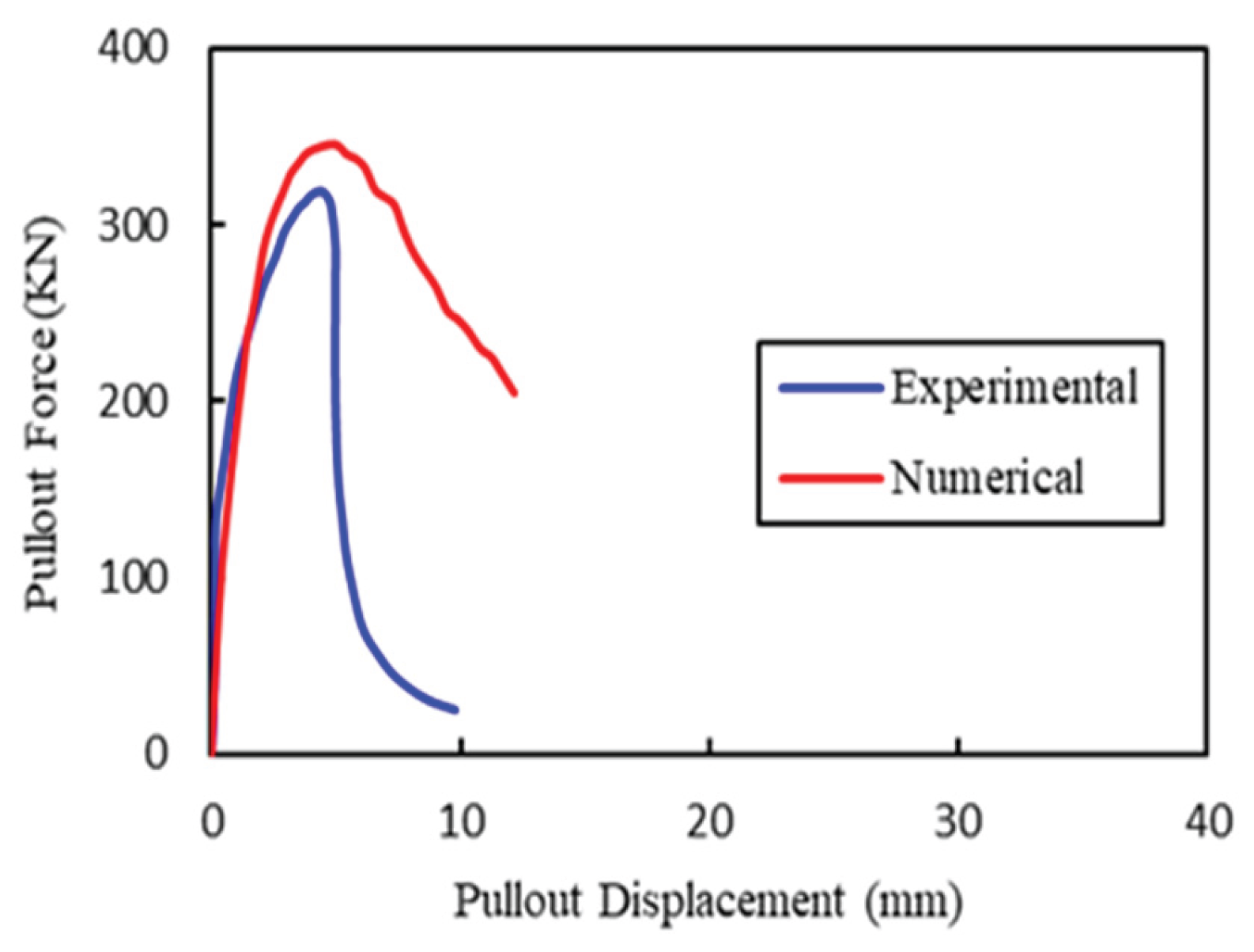

3. Validation of Pullout Test

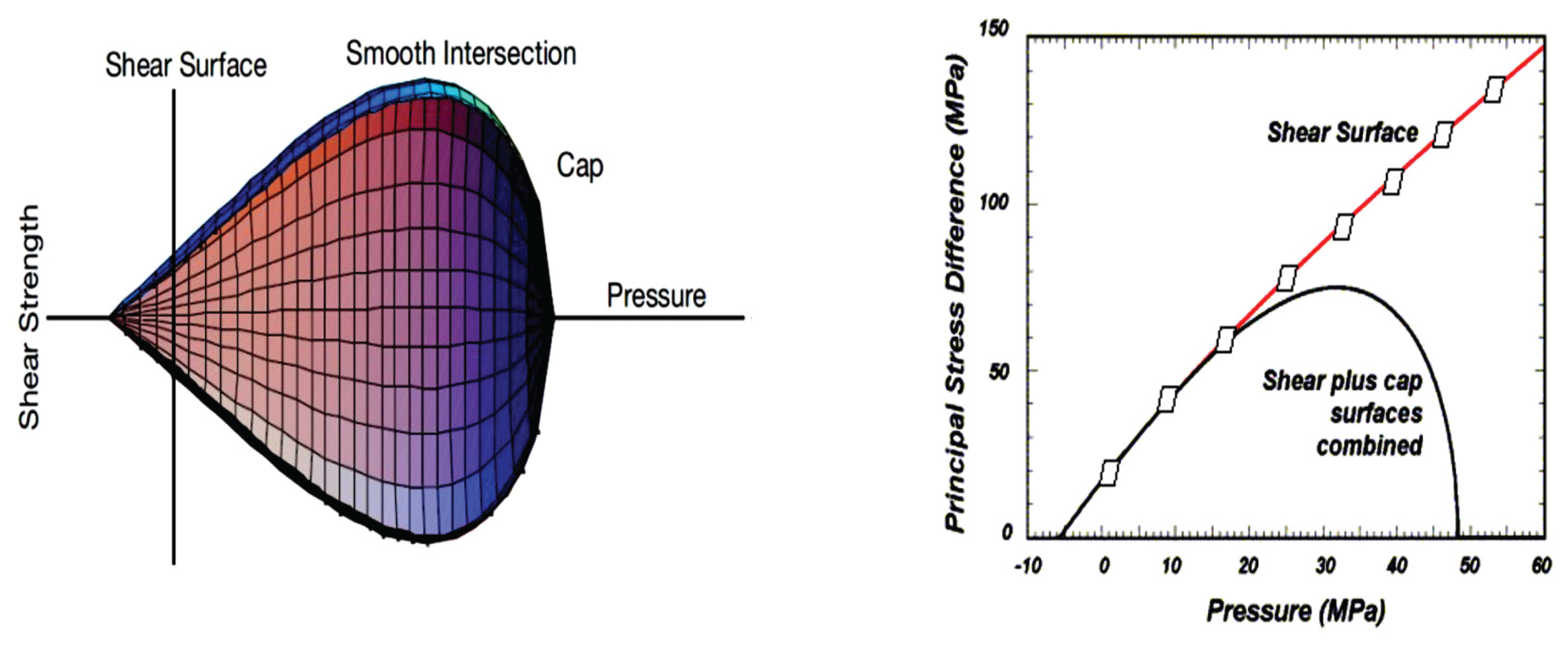

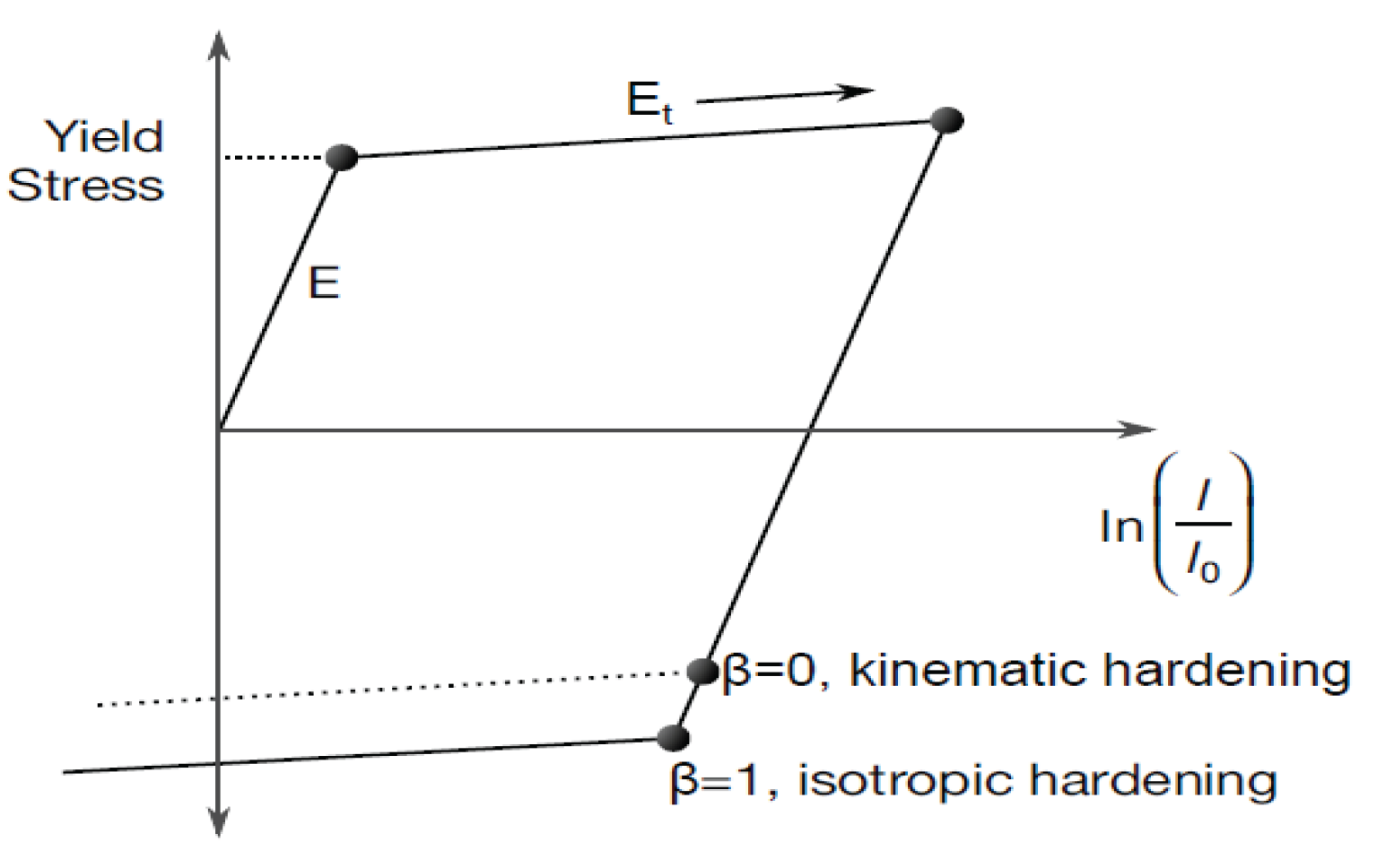

3.1. MAT-159 (Mat-CSCM-Concrete)

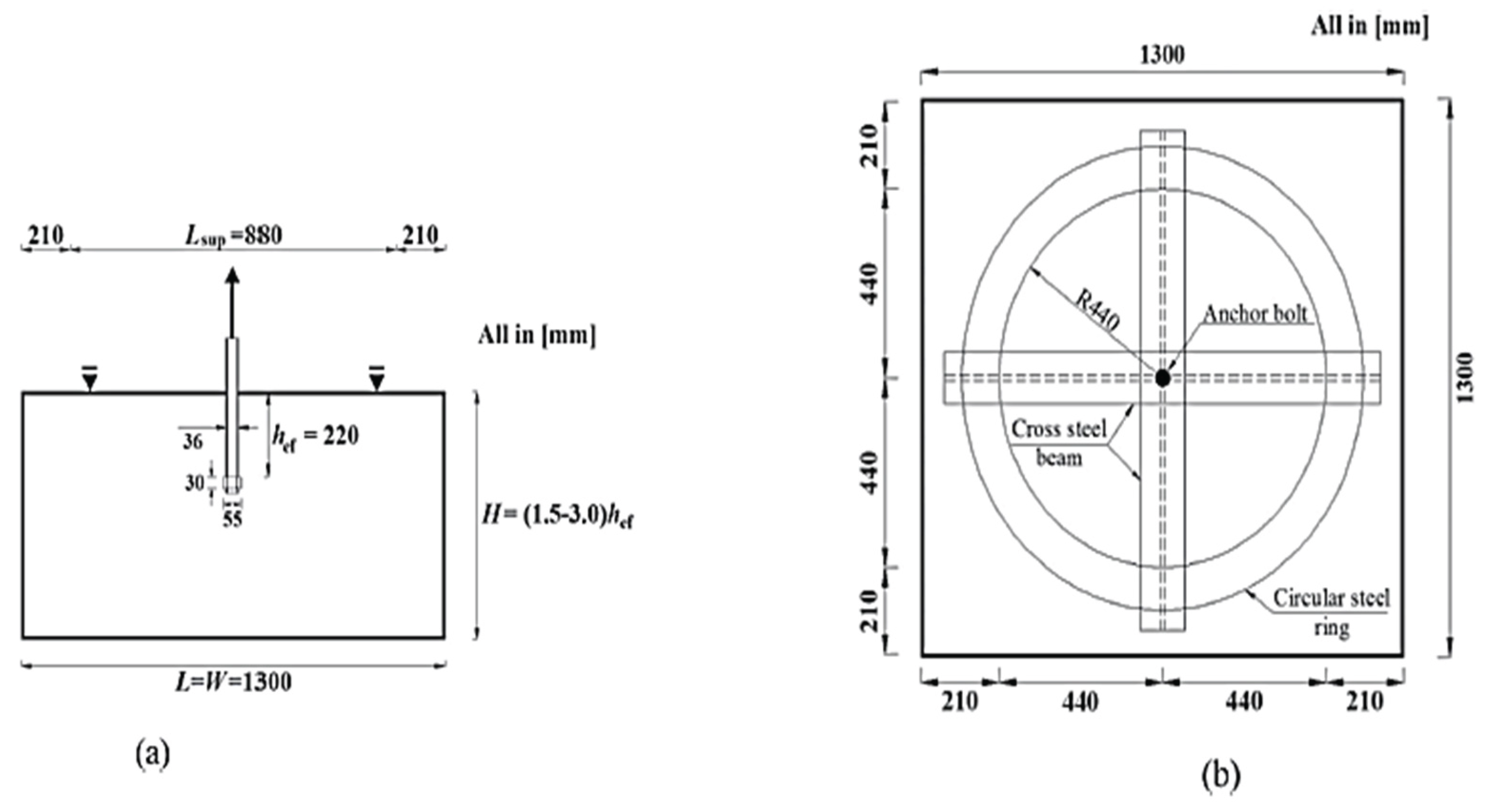

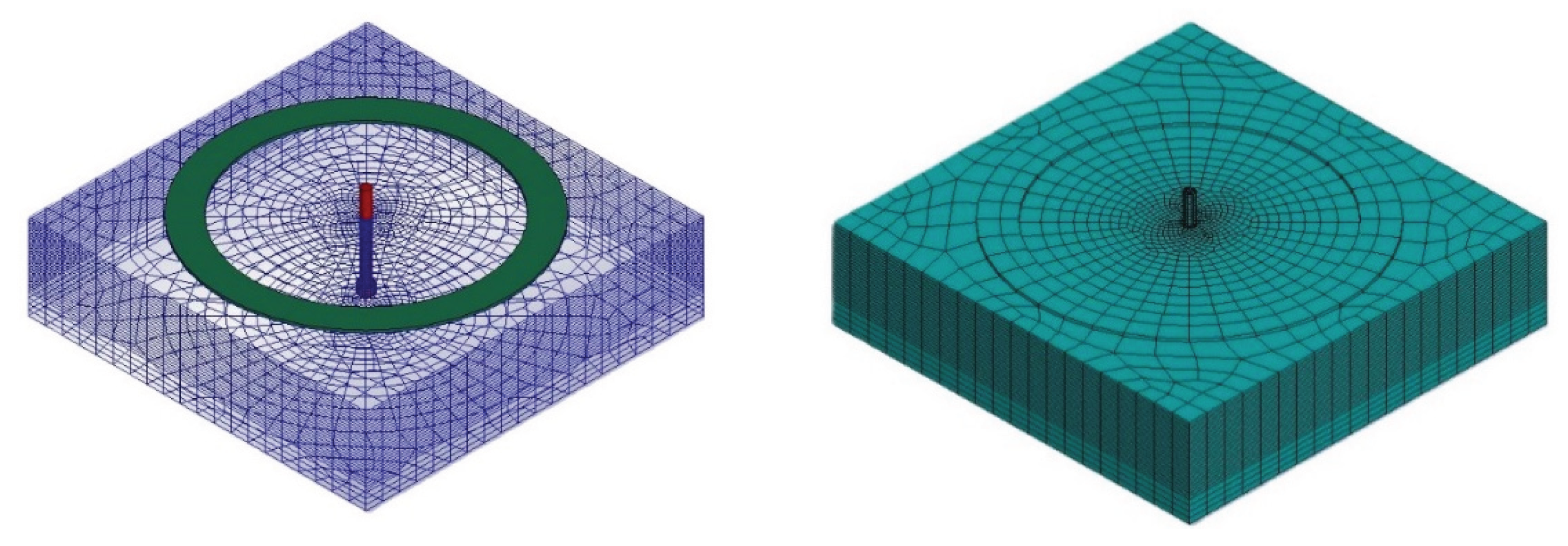

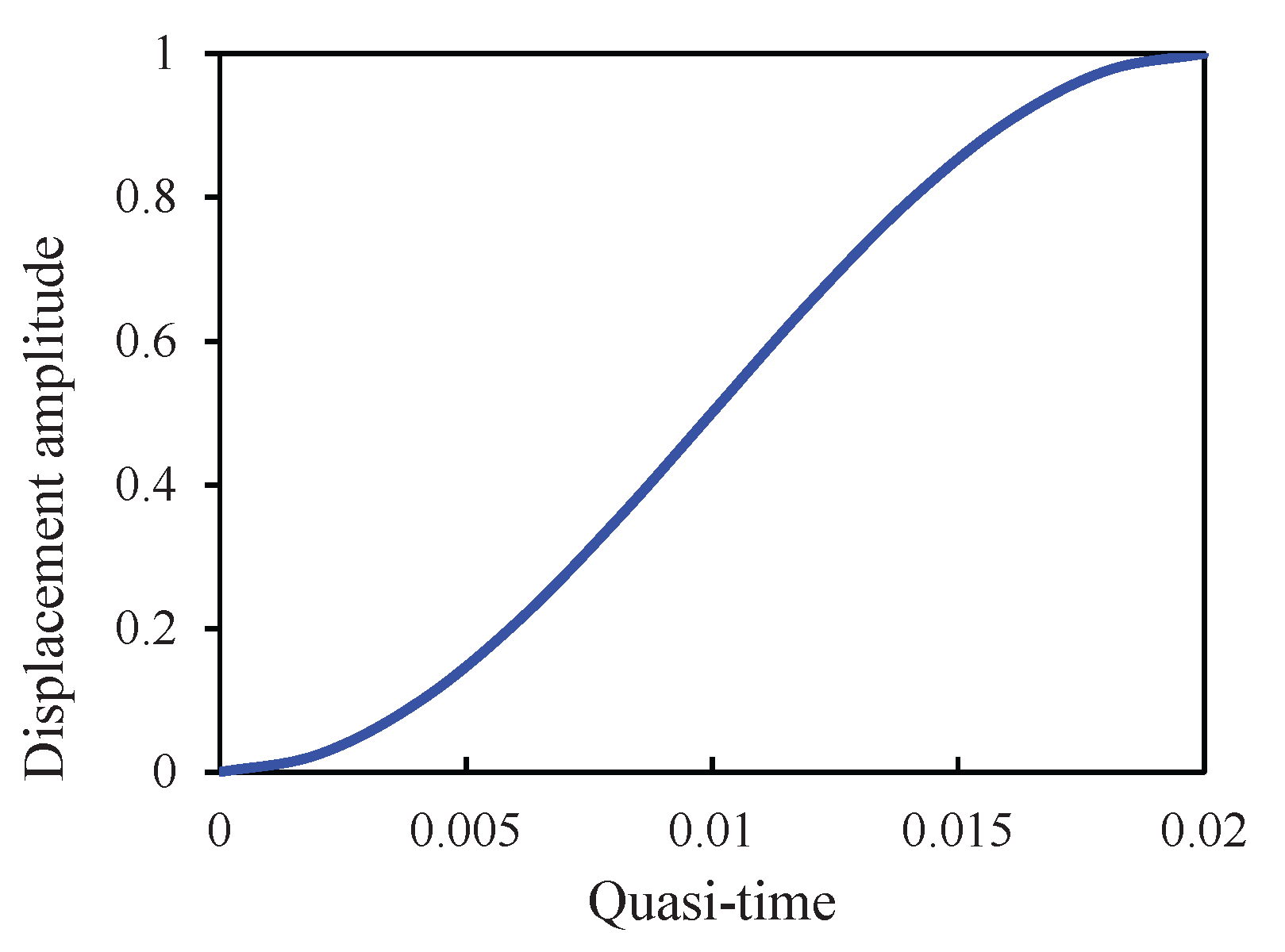

3.2. Pullout Model

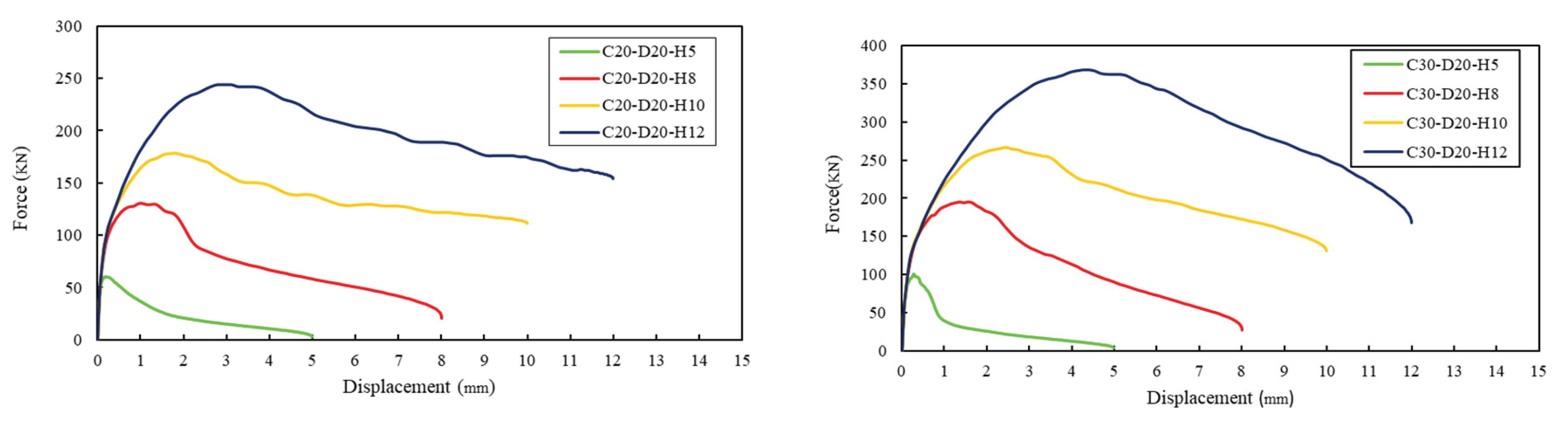

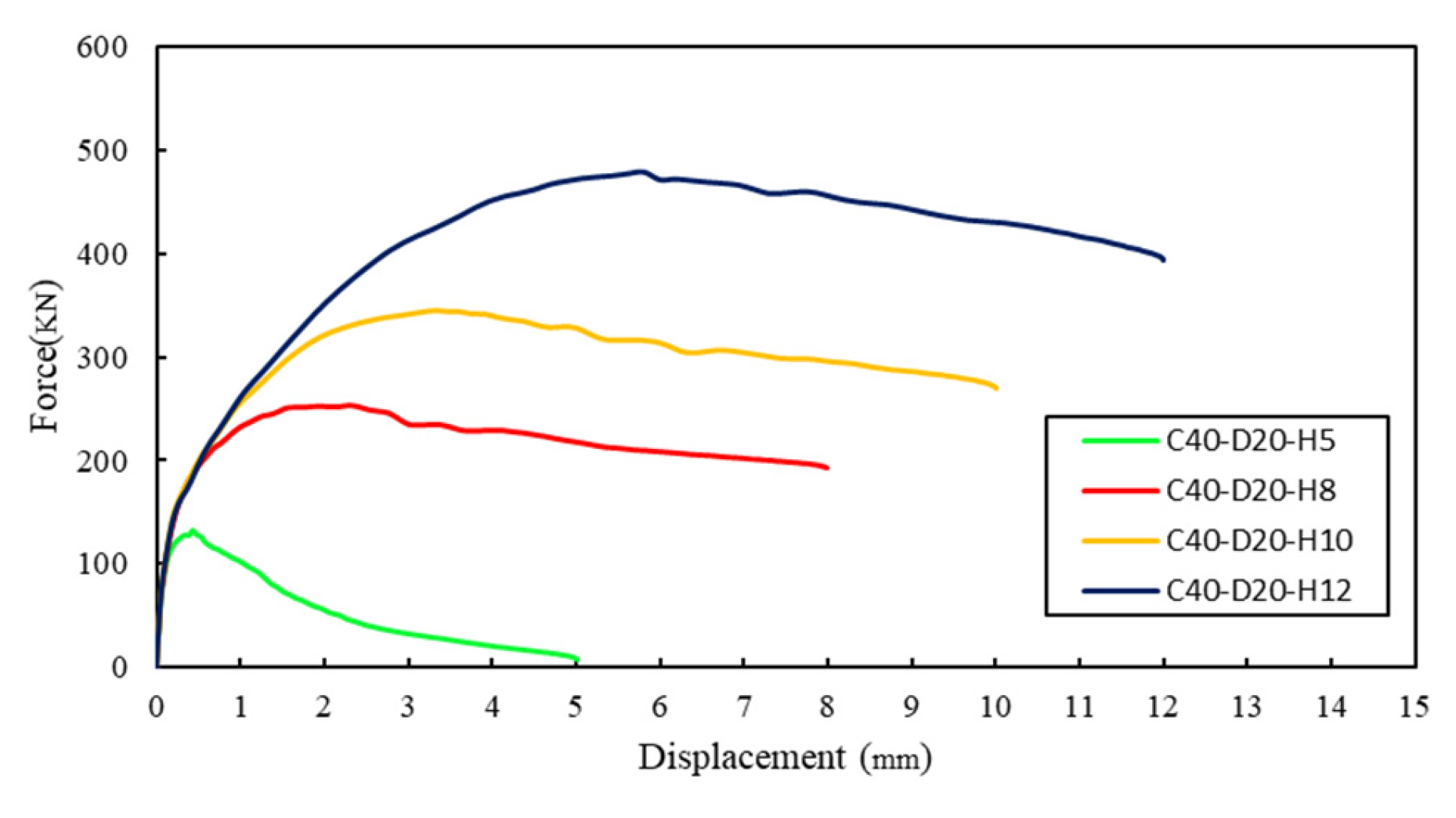

4. Parametric Study

4.1. Strength Measure

|

(mm) |

Case |

(mm) |

(Mpa) |

NACI (KN) | NCCD (KN) | NFEM (KN) | NFEM/NCCD | β | |

| 20 | C20-D20-H5 | 5 | 100 | 20 | 44.72 | 75.1 | 60.3 | 0.80 | 13.48 |

| C30-D20-H5 | 30 | 54.8 | 92.0 | 100.2 | 1.09 | 18.30 | |||

| C40-D20-H5 | 40 | 63.2 | 106.3 | 132.2 | 1.24 | 20.90 | |||

| C20-D20-H8 | 8 | 160 | 20 | 90.5 | 152.1 | 130.8 | 0.86 | 14.45 | |

| C30-D20-H8 | 30 | 110.9 | 186.2 | 195.4 | 1.05 | 17.62 | |||

| C40-D20-H8 | 40 | 128 | 215.04 | 253.2 | 1.18 | 19.78 | |||

| C20-D20-H10 | 10 | 200 | 20 | 126.5 | 212.5 | 179.0 | 0.84 | 14.15 | |

| C30-D20-H10 | 30 | 154.9 | 260.3 | 267.2 | 1.03 | 17.25 | |||

| C40-D20-H10 | 40 | 178.9 | 300.53 | 344.8 | 1.15 | 19.27 | |||

| C20-D20-H12 | 12 | 240 | 20 | 166.3 | 279.3 | 244.0 | 0.87 | 14.67 | |

| C30-D20-H12 | 30 | 203.6 | 342.1 | 369.2 | 1.08 | 18.13 | |||

| C40-D20-H12 | 40 | 235.15 | 395.05 | 480.0 | 1.22 | 20.41 | |||

| 25 | C20-D25-H5 | 5 | 125 | 20 | 62.50 | 105.00 | 103.49 | 0.99 | 16.56 |

| C30-D25-H5 | 30 | 76.55 | 128.60 | 164.82 | 1.28 | 21.53 | |||

| C40-D25-H5 | 40 | 88.39 | 148.49 | 216.30 | 1.46 | 24.47 | |||

| C20-D25-H8 | 8 | 200 | 20 | 126.49 | 212.51 | 190.00 | 0.89 | 15.02 | |

| C30-D25-H8 | 30 | 154.92 | 260.26 | 284.88 | 1.09 | 18.39 | |||

| C40-D25-H8 | 40 | 178.89 | 300.53 | 375.30 | 1.25 | 20.98 | |||

| C20-D25-H10 | 10 | 250 | 20 | 176.78 | 296.98 | 247.00 | 0.83 | 13.97 | |

| C30-D25-H10 | 30 | 216.51 | 363.73 | 385.30 | 1.06 | 17.80 | |||

| C40-D25-H10 | 40 | 250.00 | 412.88 | 502.20 | 1.22 | 20.09 | |||

| C20-D25-H12 | 12 | 300 | 20 | 232.38 | 390.40 | 336.70 | 0.86 | 14.49 | |

| C30-D25-H12 | 30 | 284.60 | 478.14 | 498.90 | 1.04 | 17.53 | |||

| C40-D25-H12 | 40 | 328.63 | 559.49 | 662.80 | 1.18 | 20.17 | |||

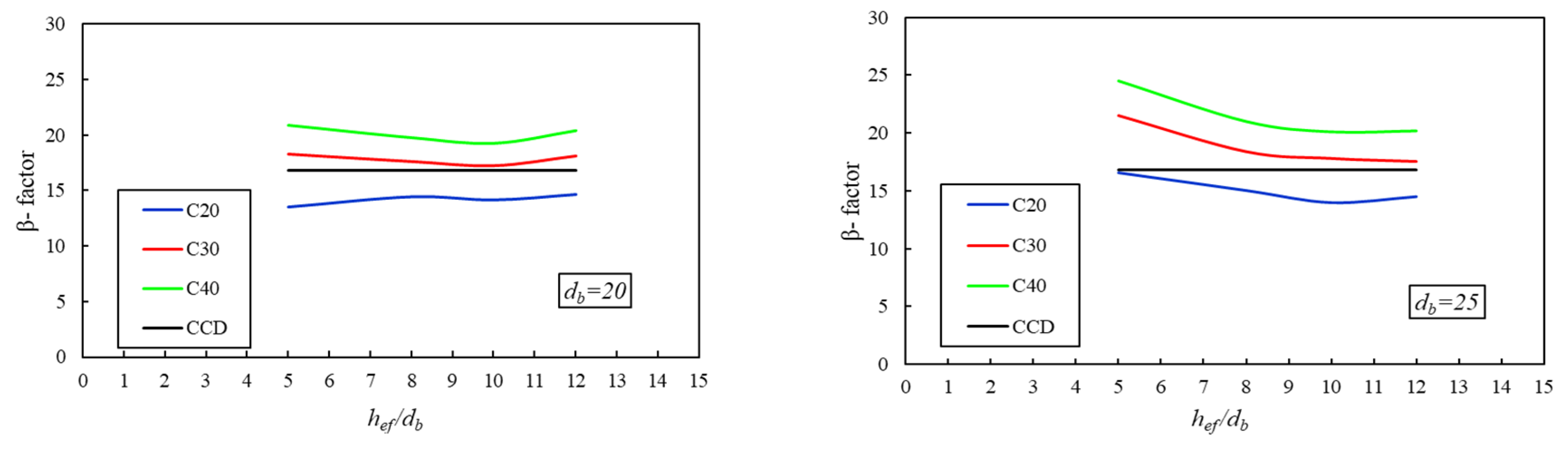

| 30 | C20-D30-H5 | 5 | 150 | 20 | 82.16 | 138.03 | 133.79 | 0.97 | 16.28 |

| C30-D30-H5 | 30 | 100.62 | 169.05 | 210.66 | 1.25 | 20.94 | |||

| C40-D30-H5 | 40 | 116.19 | 195.20 | 291.80 | 1.49 | 25.11 | |||

| C20-D30-H8 | 8 | 240 | 20 | 166.28 | 279.35 | 294.40 | 1.05 | 17.71 | |

| C30-D30-H8 | 30 | 203.65 | 342.13 | 428.29 | 1.25 | 21.03 | |||

| C40-D30-H8 | 40 | 235.15 | 395.05 | 583.30 | 1.48 | 24.81 | |||

| C20-D30-H10 | 10 | 300 | 20 | 377.12 | 390.00 | 372.00 | 0.95 | 16.02 | |

| C30-D30-H10 | 30 | 232.38 | 478.20 | 545.40 | 1.14 | 19.16 | |||

| C40-D30-H10 | 40 | 284.60 | 552.10 | 715.00 | 1.30 | 21.75 | |||

| C20-D30-H12 | 12 | 360 | 20 | 305.47 | 513.19 | 493.61 | 0.96 | 16.16 | |

| C30-D30-H12 | 30 | 374.12 | 628.53 | 720.73 | 1.15 | 19.26 | |||

| C40-D30-H12 | 40 | 432.00 | 725.76 | 928.70 | 1.28 | 21.50 |

4.2. Prediction of Embedment Depth

5. Conclusions

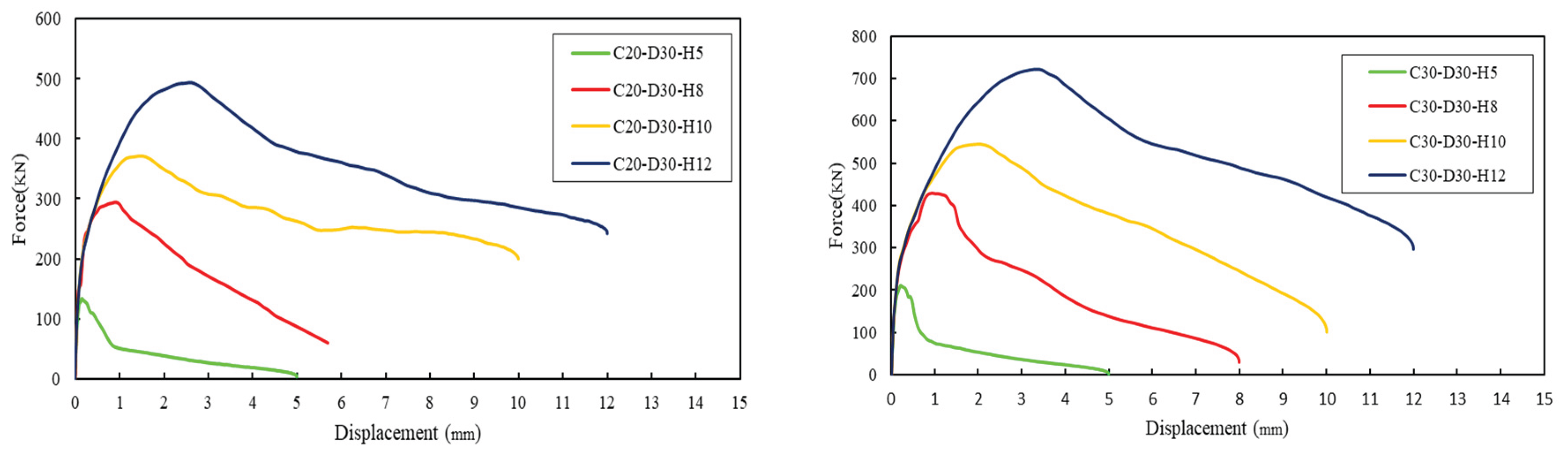

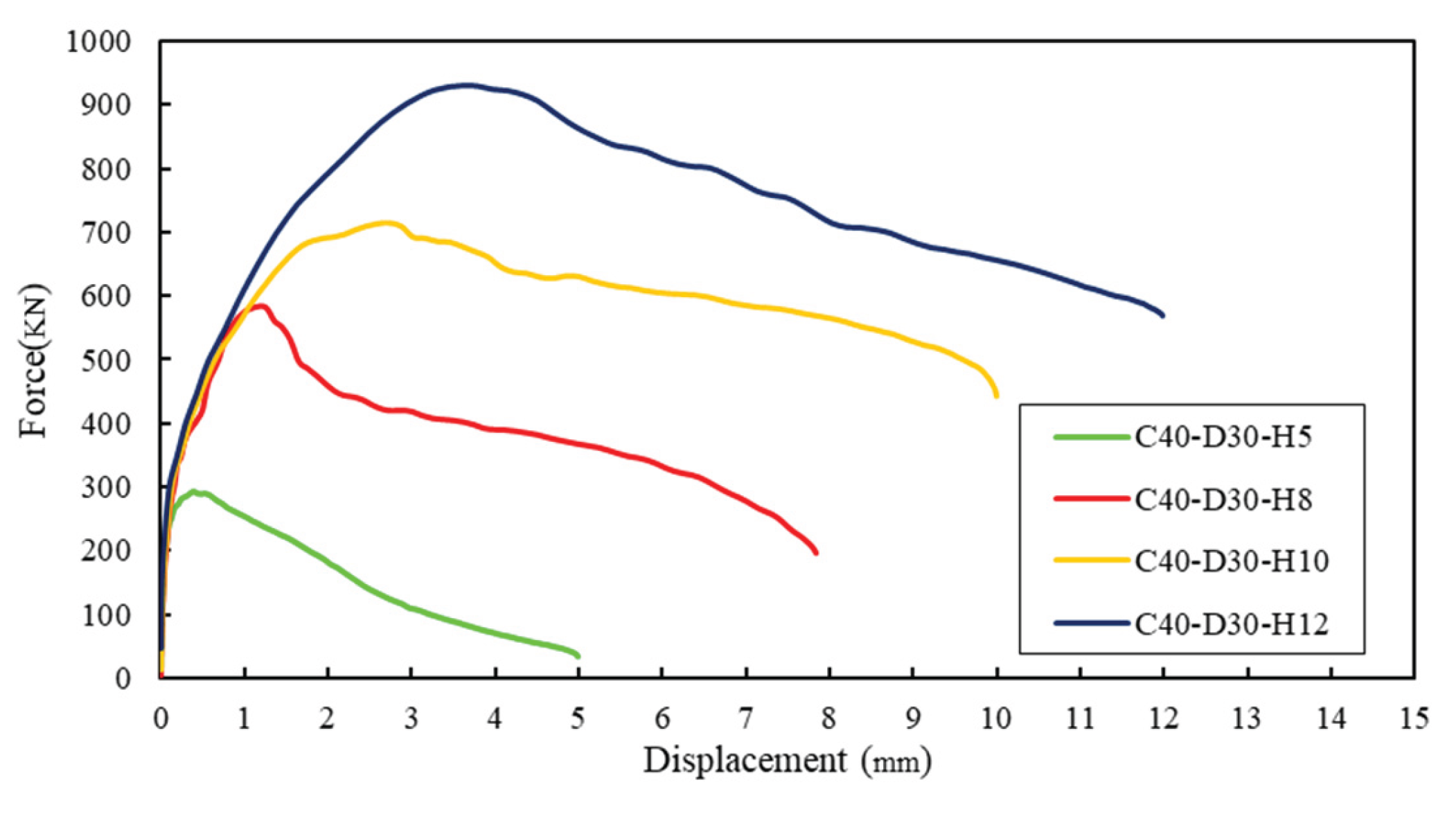

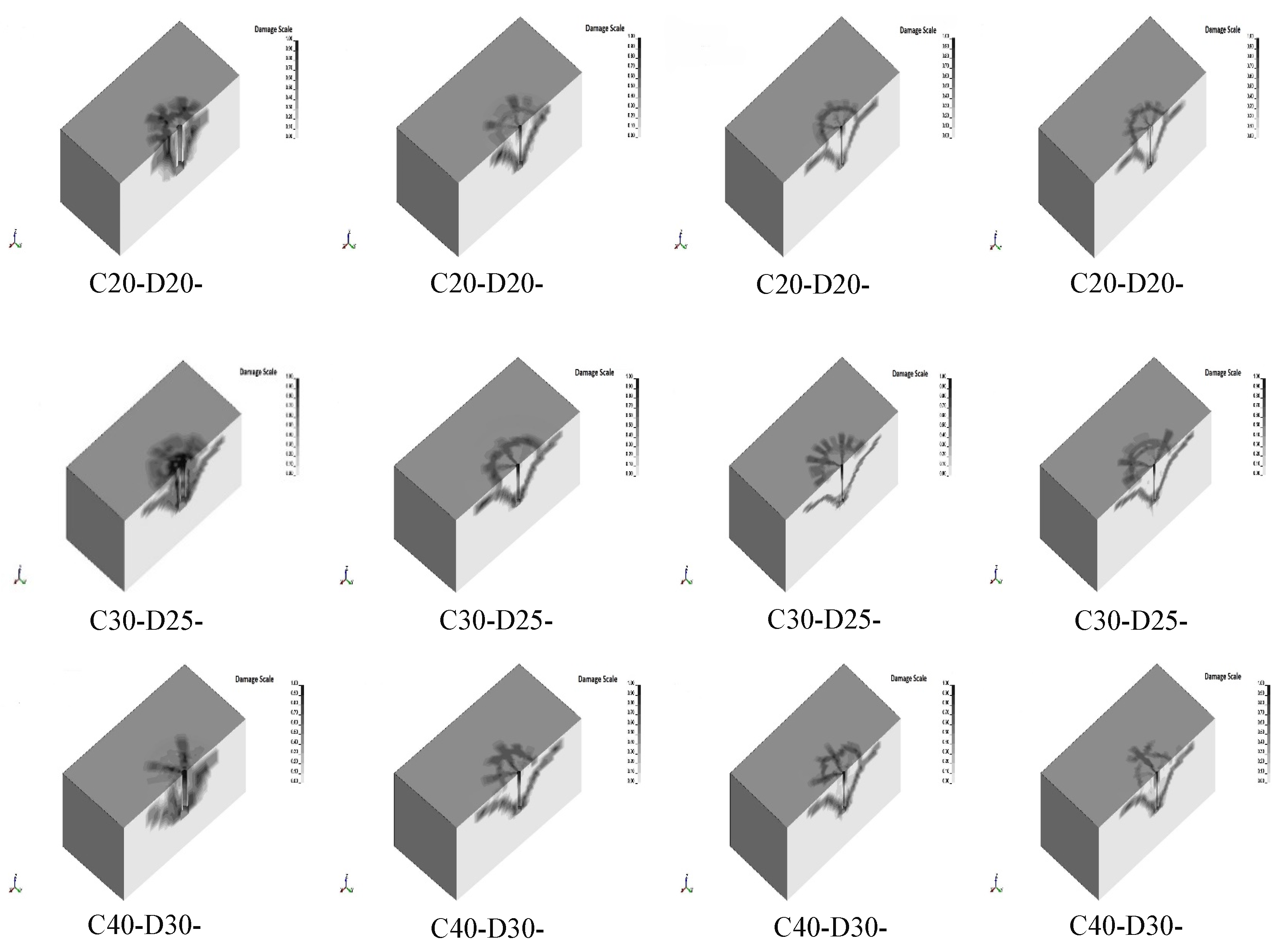

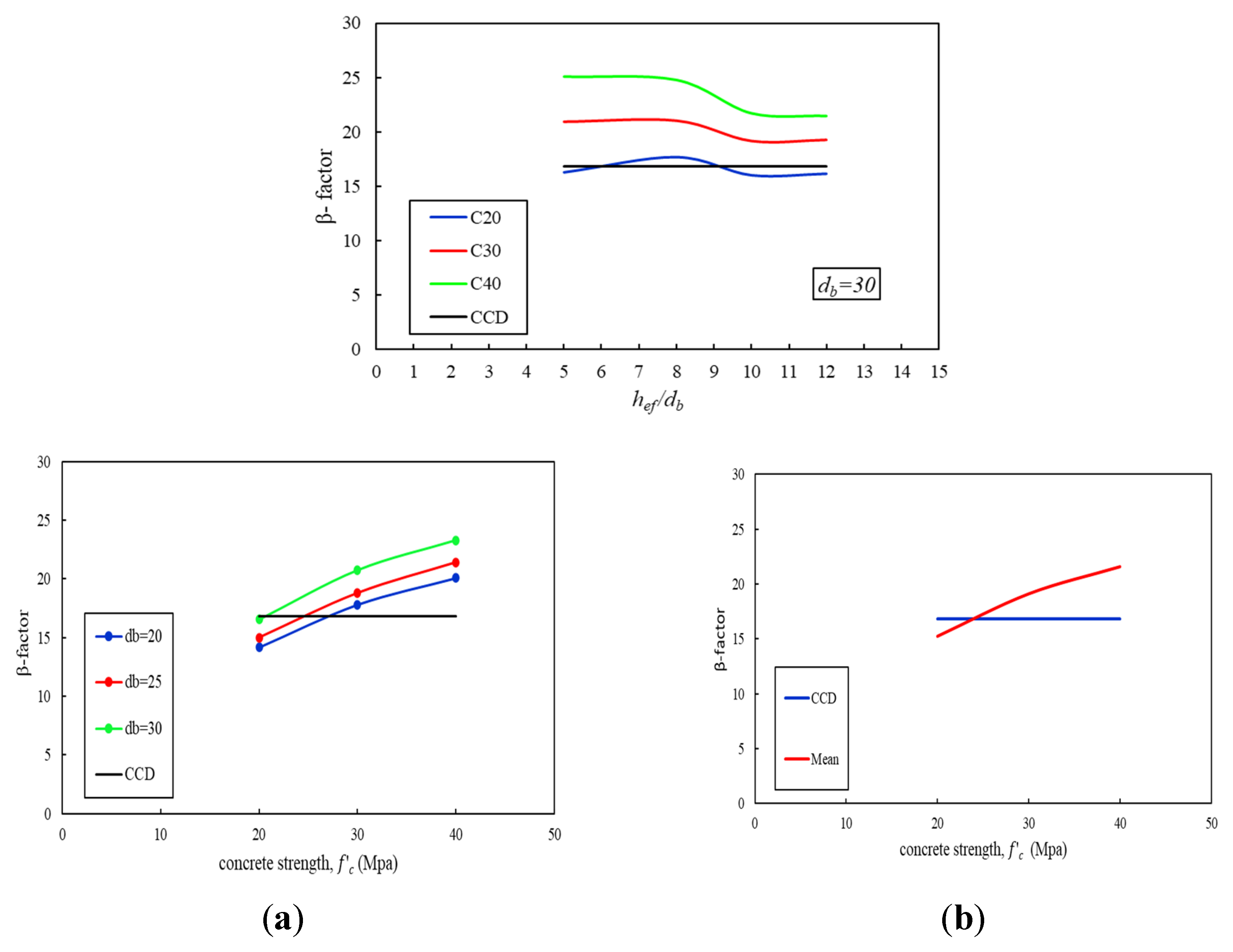

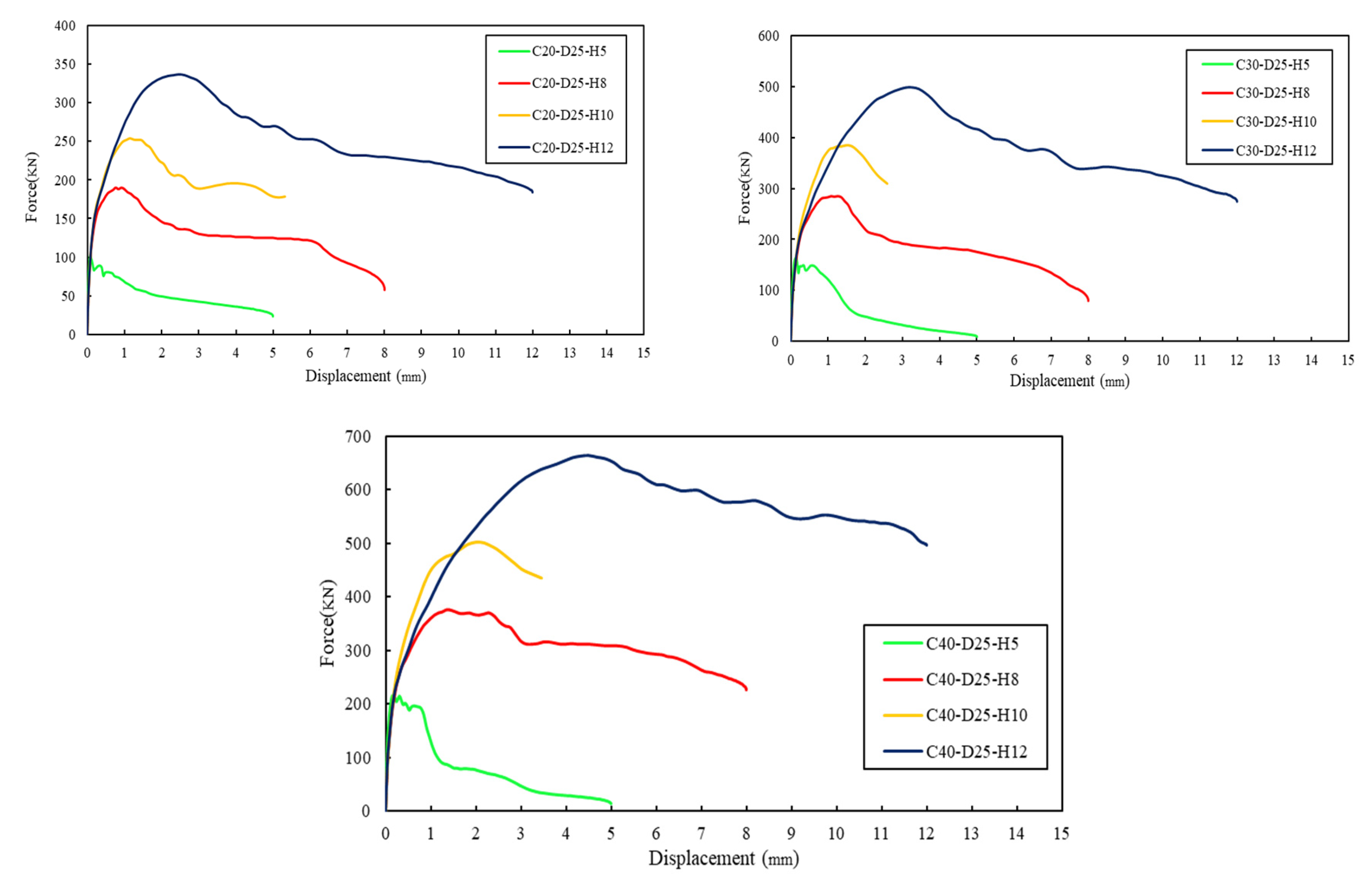

- A notable discrepancy in pullout strength emerges at the final stage of monotonic loading when compared to predictions made by the CCD method. As the ratio of embedment depth to anchor diameter decreases and concrete compressive strength increases, the divergence between the observed results and CCD estimates becomes increasingly evident. Specifically, the CCD method tends to underestimate the breakout capacity of anchor bolts embedded in unreinforced concrete members with compressive strengths of 30 MPa and 40 MPa, while it overestimates the capacity for members with a compressive strength of 20 MPa. These inconsistencies highlight the need for a revision of the current design assumptions.

- Given the observed overestimation and underestimation of pullout strength by the CCD method across varying concrete strengths, a revision of the k-factor within the CCD design model is recommended to improve predictive accuracy. The analysis results suggest average k-factor values of 15.24 for 20 MPa concrete, 18.9 for 30 MPa concrete, and 21.6 for 40 MPa concrete. Due to the embedded depth-to-diameter ratio, the CCD k-factor needs some modifications to consider the effect concrete strength parameter.

- The ratio of embedment depth to anchor diameter significantly influences the degree of convergence between the numerical results and the CCD method across different concrete strengths. Anchors with deeper embedment depths demonstrate greater alignment with CCD predictions compared to those with shallow embedment. The highest level of convergence was observed for an embedment depth of =10db in 30 MPa concrete, particularly for cast-in-place headed anchors measuring 20 mm in size.

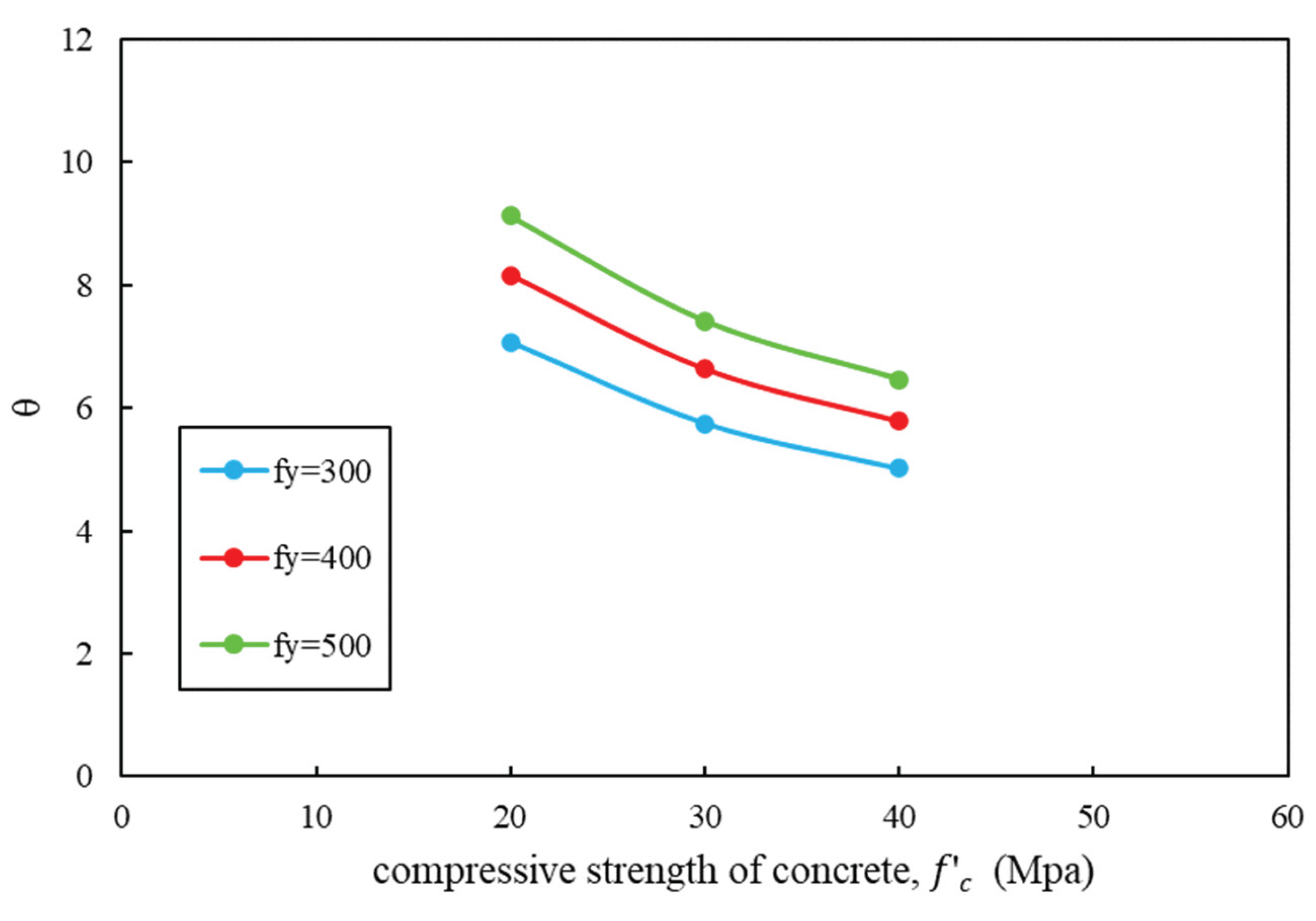

- Findings from the numerical analysis, which incorporated variations in concrete strength, steel yield strength, and embedment depth of cast-in-place headed anchors in unreinforced concrete slabs, led to the recommendation of a coefficient for predicting embedment depth based on anchor dimensions. The force–displacement response indicated that the revised embedment depth resulted in the highest displacement at peak load. Therefore, a revision to the design criteria is necessary to establish appropriate limits based on the yield strength of the steel.

References

- Abhijit kawale 1, Yogesh D. Patil., 2016 ,”Pullout Capacity and Bond Behaviour of Headed Reinforcement in concrete” International Journal of Innovative Research in Science, Engineering and Technology. Vol. 5, Issue 7, July 2016. [CrossRef]

- ACI Committee 349, “Code Requirements for Nuclear Safety Related Structures (ACI 349-01),” American Concrete Institute, Farmington Hills, MI, 2001, 134 pp.

- ACI Committee 318, 2019. “Building Code Requirements for Structural Concrete (ACI 318-14) and Commentary,” (ACI 318R-14), American Concrete Institute, Farmington Hills, Michigan,620 pp.

- ACI Committee 349 (2006). Code Requirements for Nuclear Safety Related Concrete Structures (ACI 349- 06), American Concrete Institute, Farmington Hills, MI, 134 pp.

- Ali Nazzal, L., Darwin, D. and O’Reilly, M. 2023. Anchorage of high-strength reinforcing bars in concrete. Structural Engineering and Engineering Materials SM Report No. 150.

- Bashandy, T.R, 1996, “ Application of Headed Bars in Concrete Members,” Ph.D. dissertation, The University of Texas at Austin, Austin, TX, Dec, 303 pp.

- Bujnak J, Robriquet B. On the behavior of headed fastenings between steel and concrete. Procedia Eng 2012;40:62–7.

- Bakir PG, Boduroglu MH. The ultimate load carrying capacity of concrete members with headed bars. 27th Conference on Our World in Concrete & Structures. 2002. p.163–7.

- Choi, D.-U., Hong, S.-G., and Lee, C.-Y., 2002, “Test of Headed Reinforcement in Pullout,” KCI Concrete Journal, Vol. 14, No. 3, Sep., pp. 102-110.

- DeVries, R. A., Jirsa, J. O., and Bashandy, T., 1999, “Anchorage Capacity in Concrete of Headed Reinforcement with Shallow Embedments,” ACI Structural Journal, Vol. 96, No. 5, Sep.-Oct., pp.728-736.

- Delhomme F, Roure T, Arrieta B, Limam A. Pullout behavior of cast-in-place headed and bonded anchors with different embedment depths. Mater Struct 2016;49(5):1843–59.

- Eligehausen, R., Mallée, R., & Silva, J. F. (2006a). Anchorage in Concrete Construction, Ernst & Sohn, Berlin, Germany, 378 pp.

- Fuchs, W., Eligehausen, R., & Breen, J. E. (1995). “Concrete Capacity Design (CCD) Approach for Fastening to Concrete,” ACI Structural Journal, 92(1), pp. 73–94.

- Ghimire, K.P., Darwin, D. and O’Reilly, M. 2018. Anchorage of Headed Reinforcing Bars in 385 Concrete. University of Kansas Center for Research, Lawrence, Report No. 127, p. 278. 386.

- Ghimire, K.P., Shao, Y., Darwin, D. and O’Reilly, M. 2019a. Conventional and High-Strength 387 Headed Bars-Part 1: Anchorage Test. ACI Structural Journal, 116: 257-266. 388.

- Ghimire, K.P., Shao, Y., Darwin, D. and O’Reilly, M. 2019b. Conventional and High-Strength 389 Headed Bars – Part 2: Data Analysis. ACI Structural Journal, 116: 265-272.

- Lee NH, Kim KS, Chang JB, Park KR. Tensile headed anchors with large diameter and deep embedment in concrete. ACI Struct J 2007;104(4):479–86.

- LSTC, Livermore Software Technology Corporation. (2014a). LS-DYNA Keyword User’s Manual Volume II Material Models. Livermore California (Vol. II).

- Murray YD. Users manual for LS-DYNA concrete material model 159, United States. Federal Highway Administration. Office of Research 2007.

- Nilforoush R, Nilsson M, Elfgren L, Oˇzbolt J, Hofmann J, Eligehausen R. “Tensile capacity of anchor bolts in uncracked concrete: Influence of member thickness and anchor’s head size”. ACI Struct J 2017;114(6):1519–30.

- Rao GA, Sundeep B. Strength of bonded anchors in concrete in direct tension. Chennai: Indian Institute of Technology Madras; 2013.

- Shafei, E,. Tarverdilo, S., 2021, “Seismic pullout behavior of cast-in-place anchor bolts embedded in plain concrete: Damage plasticity based analysis” Structures 34 (2021) 479–486 . [CrossRef]

- Shao, Y., Darwin, D., O’Reilly, M., Lequesne, R. D., Ghimire, K., and Hano, M., 2016, “Anchorage of Conventional and High-Strength Headed Reinforcing Bars,” SM Report No. 117, University of Kansas Center for Research, Inc., Lawrence, KS, Aug., 234 pp.

- Wallace, J. W., McConnell, S. W., Gupta, P., and Cote, P. A., 1998, “Use of Headed Reinforcement in Beam- Column Joints Subjected to Earthquake Loads,” ACI Structural Journal, Vol. 95, No. 5, Sep.-Oct., pp. 590.

- Vella JP, Vollum RL, Kotecha R. Headed Bar Connections Between Precast Concrete Elements: Design Recommendations and Practical Applications. Structures 2018;15:162–73.

| Model Name | Anchor | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Mpa) | (mm) | (mm) | (mm) | |

| NPC-330 | 41.03 | 220 | 330 | 36-(55×30) |

| Model Name | Ultimate Load | ||||

| EXP | FEM. | ||||

| (Mpa) | (mm) | (mm) | (KN) | (KN) | |

| NPC-330 | 41.03 | 220 | 330 | 319.4 | 345.2 |

|

(mm) |

Case |

(mm) |

(MPa) |

(mm) |

ring (mm) |

|

| C20-D20-H5 |

5 |

100 | 20 | 200 | 600 | |

| C30-D20-H5 | 100 | 30 | 200 | 600 | ||

| C40-D20-H5 | 100 | 40 | 200 | 600 | ||

| C20-D20-H8 |

8 |

160 | 20 | 320 | 960 | |

| C30-D20-H8 | 160 | 30 | 320 | 960 | ||

| 20 | C40-D20-H8 | 160 | 40 | 320 | 960 | |

| C20-D20-H10 |

10 |

200 | 20 | 400 | 1200 | |

| C30-D20-H10 | 200 | 30 | 400 | 1200 | ||

| C40-D20-H10 | 200 | 40 | 400 | 1200 | ||

| C20-D20-H12 |

12 |

240 | 20 | 480 | 1440 | |

| C30-D20-H12 | 240 | 30 | 480 | 1440 | ||

| C40-D20-H12 | 240 | 40 | 480 | 1440 | ||

| C20-D25-H5 |

5 |

125 | 20 | 250 | 750 | |

| C30-D25-H5 | 125 | 30 | 250 | 750 | ||

| C40-D25-H5 | 125 | 40 | 250 | 750 | ||

| C20-D25-H8 |

8 |

200 | 20 | 400 | 1200 | |

| C30-D25-H8 | 200 | 30 | 400 | 1200 | ||

| 25 | C40-D25-H8 | 200 | 40 | 400 | 1200 | |

| C20-D25-H10 |

10 |

250 | 20 | 500 | 1500 | |

| C30-D25-H10 | 250 | 30 | 500 | 1500 | ||

| C40-D25-H10 | 250 | 40 | 500 | 1500 | ||

| C20-D25-H12 |

12 |

300 | 20 | 600 | 1800 | |

| C30-D25-H12 | 300 | 30 | 600 | 1800 | ||

| C40-D25-H12 | 300 | 40 | 600 | 1800 | ||

| C20-D30-H5 |

5 |

150 | 20 | 300 | 900 | |

| C30-D30-H5 | 150 | 30 | 300 | 900 | ||

| C40-D30-H5 | 150 | 40 | 300 | 900 | ||

| C20-D30-H8 |

8 |

240 | 20 | 480 | 1440 | |

| C30-D30-H8 | 240 | 30 | 480 | 1440 | ||

| 30 | C40-D30-H8 | 240 | 40 | 480 | 1440 | |

| C20-D30-H10 |

10 |

300 | 20 | 600 | 1800 | |

| C30-D30-H10 | 300 | 30 | 600 | 1800 | ||

| C40-D30-H10 | 300 | 40 | 600 | 1800 | ||

| C20-D30-H12 |

12 |

360 | 20 | 720 | 2160 | |

| C30-D30-H12 | 360 | 30 | 720 | 2160 | ||

| C40-D30-H12 | 360 | 40 | 720 | 2160 |

| fy | ||||

| 300 | 400 | 500 | ||

| (mm) | (Mpa) | (Mpa) | (Mpa) | (Mpa) |

| θ | ||||

| 20 | 20 | 6.94 | 8.01 | 8.96 |

| 30 | 5.60 | 6.47 | 7.23 | |

| 40 | 4.91 | 5.67 | 6.34 | |

| 25 | 20 | 7.14 | 8.24 | 9.22 |

| 30 | 5.79 | 6.69 | 7.48 | |

| 40 | 5.05 | 5.83 | 6.52 | |

| 30 | 20 | 7.12 | 8.23 | 9.20 |

| 30 | 5.85 | 6.75 | 7.55 | |

| 40 | 5.07 | 5.85 | 6.54 | |

| (Mpa) | Concrete Strength, (Mpa) | ||

| 20 | 30 | 40 | |

| θ | |||

| 300 | 7.0 | 5.7 | 5.0 |

| 400 | 8.2 | 6.6 | 5.8 |

| 500 | 9.1 | 7.4 | 6.5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).