1. Introduction

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is a rare immune-mediated connective tissue disease with a prevalence of 17.6 per 100,000 around the world.[

1] Explained by its pathophysiology, vasculopathy and diffuse fibrosis, the disease affects multiple systems of the body leading to high rates of morbidity and mortality.[

2,

3,

4] Cardiovascular and pulmonary complications were considered the primary cause of death in systemic sclerosis patients. However, a large number of evidence-based treatments has been developed, leading to a notable reduction in mortality associated with such complications.[

4,

5] While many serious complications are now treatable[

4], non-lethal manifestation steps up as the new challenge in improving the patient’s quality of life. One of the most common clinical features in systemic sclerosis is the gastrointestinal involvement, often caused by dysmotility and fibrosis, affects approximately 90% of the patients with systemic sclerosis.[

6,

7,

8] These symptoms, including dysphagia, malabsorption, constipation, diarrhea etc., not only reduced the patients’ quality of life[

9], but also put the them at risk of malnutrition.[

4,

6,

9,

10] Since malnutrition was proved to be associated with morbidity and mortality, it has become essential that all systemic sclerosis patients must be screened for malnutrition.[

8,

9,

11,

12]

In the past, malnutrition was assessed based on history taking, physical examination and objective parameters including anthropometric measurements, such as midarm circumference, and laboratory results, such as albumin level and total lymphocyte count, etc. The parameters could be interfered by various insults leading to a large number of misdiagnosis of malnutrition.[

13] However, in 1987, after the construct of Subjective Global Assessment (SGA), nutritional assessment has been easier and more convenient for all medical staffs.[

14] Malnutrition has been assessed and diagnosed more accurately since then. While SGA has long been considered the gold standard, its subjective nature and time-consuming process have led to the exploration of alternative tools for more convenient clinical use. Over the past decades, many other new nutritional assessment tools have been announced both in Thailand and internationally. The commonly used nutritional assessment tools in Thailand include Nutritional Alert Form (NAF), Nutritional Triage 2013 (NT-2013). Both are clinical scoring systems developed by Thai experts.[

13,

15]

NAF is designed to be easy, concise, and does not require specialized nutrition expertise. Additionally, it can be utilized in settings where body weight measurement may not be feasible, as it incorporates the effects of serum albumin and total lymphocyte count [

13]. NT-2013 consists of 9 questions including dietary history, changes in body weight, fluid retention, loss of subcutaneous fat, loss of muscle mass, muscle function, chronic illness severity, acute illness severity, and a summarized score for each category [

15].

As far as our concern, the nutritional assessment tools mentioned were based-on experience of other diseases and there were no specific tools for assessing malnutrition in systemic sclerosis.[

2,

6] The aim of the study is to compare, in systemic sclerosis patients, the performances of nutritional assessment tools including NAF and NT-2013 to SGA, which is now a gold standard in diagnosing malnutrition but inconvenient in clinical practice.

2. Materials and Methods

A cross-sectional study enrolled systemic sclerosis patients from the scleroderma clinic, Srinagarind hospital, Thailand, between 1

st May 2022 and 31

st January 2024. The inclusion criteria were patients diagnosed with systemic sclerosis according to ACR/EULAR criteria, aged 18 years or older and able to provide informed consent. Patients with critically ill conditions or patients who could not undergo nutritional assessment were excluded. In each patient, baseline characteristic data including age, gender, signs and symptoms of SSc as well as organ involvement, and medication were collected. Three nutritional assessment tools, including NAF, NT-2013, and SGA (

Appendix A1, A2, and A3), through questionnaires and physical examination, were performed in each patient by single assessor to minimize interpersonal variability. SGA included items related to dietary intake, weight changes, gastrointestinal symptoms, functional status, medical history of illness, and physical examination for loss of subcutaneous fat, muscle wasting, ankle edema, sacral edema, and ascites. To diagnose malnutrition, SGA relied on a combined subjective assessment of data from history and physical examination. NAF included information about current body weight, history of weight change, height, arm span, body mass index (BMI), serum albumin or total lymphocyte count if body weight was not available, dietary intake, capacity to assess food, underlying diseases, and physical examinations emphasized on general appearance. A total NAF score of 6 or more indicated malnutrition. NT-2013 incorporated details about current body weight, usual body weight, ideal body weight, change in body weight, height, patient performance status, dietary intake, underlying diseases, severity of stress affecting nutrition and metabolism, physical signs of body fat and fat loss, signs of fluid accumulation, as well as motor power assessed handgrip strength. NT-2013 diagnosed malnutrition when the score reached 5 or higher. The primary outcome was to compare performance in diagnosing malnutrition between NAF and NT-2013 with SGA. The secondary outcome was to determine appropriate cut-off points of NAF and NT-2013 in SSc patients.

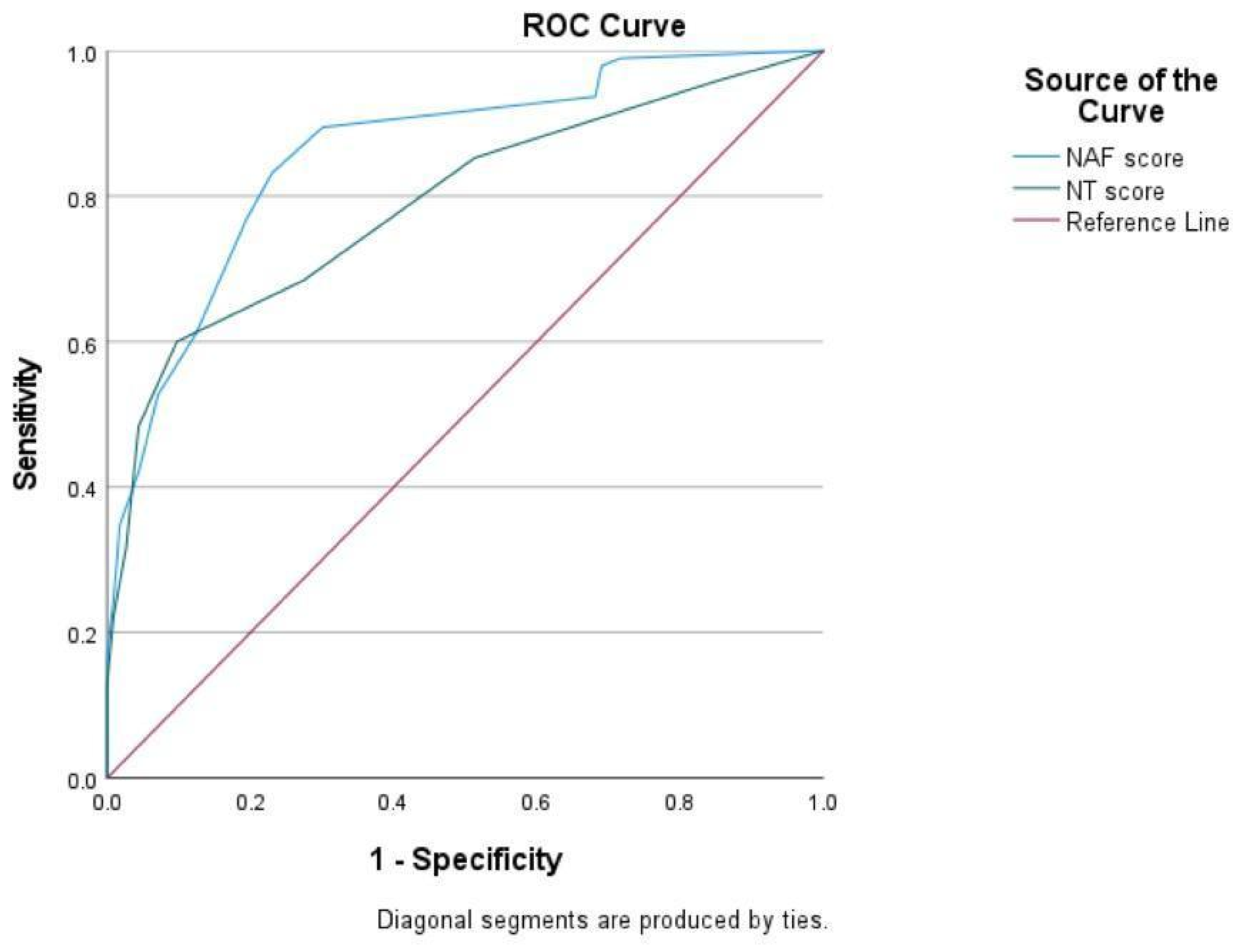

To elucidate the efficacy and correlations of these tools, descriptive statistics, Pearson correlation analyses, and Kappa coefficient of agreement were employed. Categorical variables were expressed as percentages and absolute values, while continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Pearson’s correlation coefficient (r) was used to determine the correlation between NAF and NT-2013 score [

16]. Kappa (κ) statistic was calculated to measure the agreement between all assessment tools. The results were interpreted as follows: ≤0.20, poor agreement; 0.21-0.40, fair agreement; 0.41-0.60, moderate agreement; 0.61-0.80, substantial agreement; and 0.81-1.00, almost perfect agreement [

17]. To analyze the sensitivity and specificity of NAF and NT-2013 for detection malnutrition, receiver operating characteristics curves (ROC curves) were generated, including area under the curve (AUC) and their 95% confidence intervals (CI). Statistical significance was set at

P < 0.05 for all tests. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 28.0 (IBM, Armonk, NY). A sample size of at least 97 participants was required to provide the level of significance of 0.05.

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of Khon Kaen University. All participants were provided written informed consent prior to enrollment in the study. Confidentiality of participant information was strictly maintained throughout the study period, and data were anonymized for analysis.

3. Results

The study incorporated a total of 208 patients diagnosed with systemic sclerosis. Among these participants, 149 were identified as female, representing approximately 71.6% of the total sample, while 59 were male, accounting for approximately 28.3%. Basic characteristics were shown in

Table 1.

From history taking, it was noted that a subset of patients experienced challenges in accessing food, with 6 patients (2.9%) reporting limitations in their ability to independently access food. Among these, 2 patients exhibited slight limitations, 3 were partially dependent, and 1 was entirely reliant on others for food intake. Additionally, 20 individuals (9.6%), reported significant weight loss within the past 6 months.

Gastrointestinal symptoms were prevalent among the study population, with 50 patients (24.0%) reporting symptoms upon intake. Specifically, 12 patients experienced aspiration, 42 reported dysphagia, 5 reported diarrhea, 4 reported anorexia, and 8 reported symptoms of nausea or vomiting. Importantly, it was observed that some patients experienced multiple gastrointestinal symptoms simultaneously, underscoring the complexity and multifaceted nature of gastrointestinal involvement in systemic sclerosis.

Physical examination further elucidated aspects of nutritional status and overall health. Hyposthenic build was observed in a considerable proportion of patients, with 63 individuals (30.3%) exhibiting thin or cachexic physique. Edema, indicative of fluid retention, was noted in 12 patients (5.8%), with varying degrees of severity ranging from mild to severe. Additionally, assessments of fat and muscle mass revealed significant proportions of patients with low fat mass (42 patients, 20.2%) and low muscle mass (42 patients, 20.2%) emphasizing potential sarcopenia among SSc patients.

Table 2 indicated findings that a significant proportion of the patients, specifically 95 cases (45.7%), were reportedly categorized as malnourished based on SGA. The mean and standard deviation of NAF and NT score was 8.4

+ 4.19 and, 4.0

+ 2.46 respecitively. Malnutrition diagnoses using NAF and NT-2013 criteria were identified in 167 patients (80.3%) and 72 patients (34.6%), respectively.

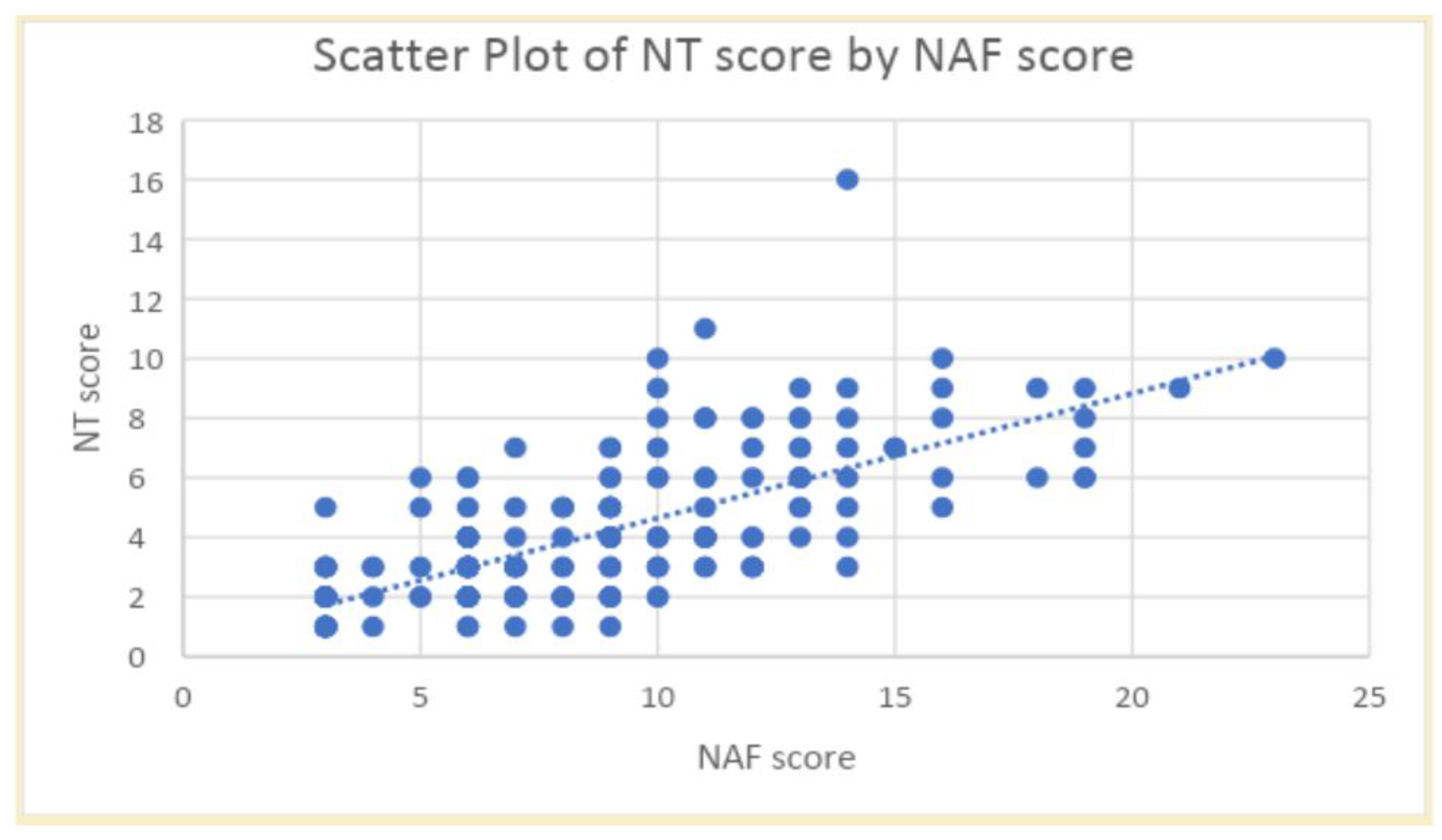

Figure 1 showed a strong correlation between the NAF and NT-2013 total scores (r= 0.71, p<0.001). However, both NAF and NT-2013 exhibited slight agreement with SGA, displaying kappa values of 0.149 for NAF and 0.131 for NT-2013. Moreover, the sensitivity and specificity of NAF for diagnosing malnutrition were determined to be 93.7% and 31.9%, respectively, while the sensitivity and specificity of NT-2013 were found to be 60.0% and 90.3%. ROC curves of NAF and NT-2013 were shown in

Figure 2.

Adjusting the cut-off points of NAF and NT-2013 could enhance sensitivity, specificity, and improve agreement for diagnosis with SGA. From our study, increasing the cut-off points of NAF from 6 to 7 leaded to improved specificity of 69.9% (from 31.9%) while sensitivity of 89.5% remained. On the other hand, decreasing the cut-off point of NT-2013 from 5 to 4 resulted in improvement of sensitivity (60.0% from 48.4%) in exchange of less specificity (72.6% from 90.3).

4. Discussion

Malnutrition is common in SSc patients. In this study, the findings revealed a high prevalence of malnutrition among SSc patients, with almost half of the participants (45.7%) diagnosed as malnourished based on SGA criteria. Previous study with 56 SSc patients showed that prevalence of malnutrition, assessed by the same method, was approximately 23.2%.[

10] The difference in prevalence may be due to the number of enrolled patients. Our study included 208 SSc patients which was one of the largest sample sizes in this area of research.

This cohort also found that prevalence of malnutrition was also varied when assessed by different nutritional assessment methods. With NAF, 80.6% of SSc patients were malnourished, while only 34.6% were reported by NT-2013. Although difference in prevalence, a strong correlation between NAF and NT-2013 total scores indicated that these tools assess similar aspects of nutritional status among SSc patients. Both tools included data of weight loss, abnormal GI symptoms, food intake, functional capacity, illness, physical exam, as well as illness; however, both methods emphasized different factors in calculation.

Despite the correlation of score, both NAF and NT-2013 showed only slight agreement with SGA in diagnosing malnutrition which could be explained by several factors.

Firstly, NAF and NT-2013 emphasized different criteria compared to SGA. SGA relied heavily on subjective evaluation by healthcare providers, including physical examination and extensive patient history involving a comprehensive assessment that considered various factors beyond objective measurements, while NAF and NT-2013 focused more on objective measures categorizing nutritional status.[

13,

14,

15] As a result, SGA provides a more holistic understanding of the patient's nutritional status and may be more sensitive to subtle changes in nutritional status or may capture aspects of malnutrition that were not adequately addressed by NAF and NT-2013.[

14]

Secondly, SGA, NAF and NT-2013 have been developed based on populations with diverse illnesses, but not SSc. SSc patients exhibited variability in their nutritional status. Factors such as disease severity, comorbidities, and individual dietary habits may contribute to discrepancies in the diagnosis of malnutrition and could impact the agreement between different assessment tools.[

6,

7,

8,

9] As a result, they may not capture certain nuances or characteristics of malnutrition that were relevant to SSc patients, leading to difference in diagnostic agreement.[

13,

14,

15]

Thirdly, SGA, NAF, and NT-2013 differed in details and the weighting of scores. Nonetheless, they shared the same underlying principle as SGA, as evidenced by the improvement in sensitivity when adjusting the cut-off points. This was due to the fact that these tools operate based on the same principle.[

13,

14,

15]

Adjusting the cut-off values of NAF and NT-2013 may improve performance of both tools in diagnosing malnutrition in SSc patients. The current cut-off point of NAF may resulted in overly sensitive diagnosis, increasing the threshold could improve specificity without losing sensitivity. Nonetheless, adjusting the cut-off values of NT-2013 was more challenged since improved in sensitivity accompanied by decreased specificity.

The strengths of the study included minimizing selection bias, as all eligible patients were included. Moreover, there was absence of interpersonal variability since all patients were evaluated by a single examiner. Additionally, the robust sample size, considered one of the highest in this area of research, underscored the reliability of the findings. Although this study proposed a new cut-off point, the diagnostic value would be greater if there were long-term follow-ups to assess clinical outcomes.

Overall, while NAF and NT-2013 may correlate well with each other in assessing nutritional status among SSc patients, their agreement with SGA in diagnosing malnutrition may be influenced by various factors related to assessment approach, tool specificity, and patient variability. Adjusting the cut-off points of NAF and NT-2013 could enhance sensitivity, specificity, and improve agreement for diagnosis with SGA. Further research is still needed to understand the underlying reasons for these discrepancies and to refine nutritional assessment tools for SSc patients. Future studies could explore additional factors that may influence the diagnosis of malnutrition in SSc patients and evaluate the effectiveness of interventions aimed at improving nutritional status in this population.

5. Conclusions

Malnutrition is common in SSc patients. Early detection of such condition may lead to proper management, resulting in improved clinical outcomes. Prevalence of malnutrition in SSc patients may be varied among different nutritional assessment tools. NAF and NT-2013 exhibited a strong correlation of diagnosis of malnutrition between the two tools, but only displayed slight agreement of diagnosis of malnutrition with SGA. Adjusting the cut-off points of NAF and NT-2013 could enhance sensitivity, specificity, and improve agreement for diagnosis with SGA. Further research is needed to understand the underlying reasons for these discrepancies and to refine nutritional assessment tools for systemic sclerosis patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, K.B. and V.P.; methodology, K.B. and V.P.; software, V.P.; validation, K.B., C.F. and V.P.; formal analysis, K.B. and V.P.; investigation, K.B. and O.W.; resources, C.F. and V.P.; data curation, K.B. and V.P.; writing—original draft preparation, K.B. and V.P.; writing—review and editing, K.B. and V.P.; visualization, K.B.; supervision, C.F. and V.P.; project administration, O.W.; funding acquisition, V.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Faculty of Medicine, Khon Kaen University.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by the Institutional Review Board (or Ethics Committee) of KHON KAEN UNIVERSITY (protocol code HE651010).

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in the study.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing is not applicable to this article.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledged the systemic sclerosis research group for administrative and logistic support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| NAF |

Nutrition Alert Form |

| NT-2013 |

Nutrition Triage 2013 |

| SGA |

Subjective Global Assessement |

| SSc |

Systemic sclerosis |

Appendix A

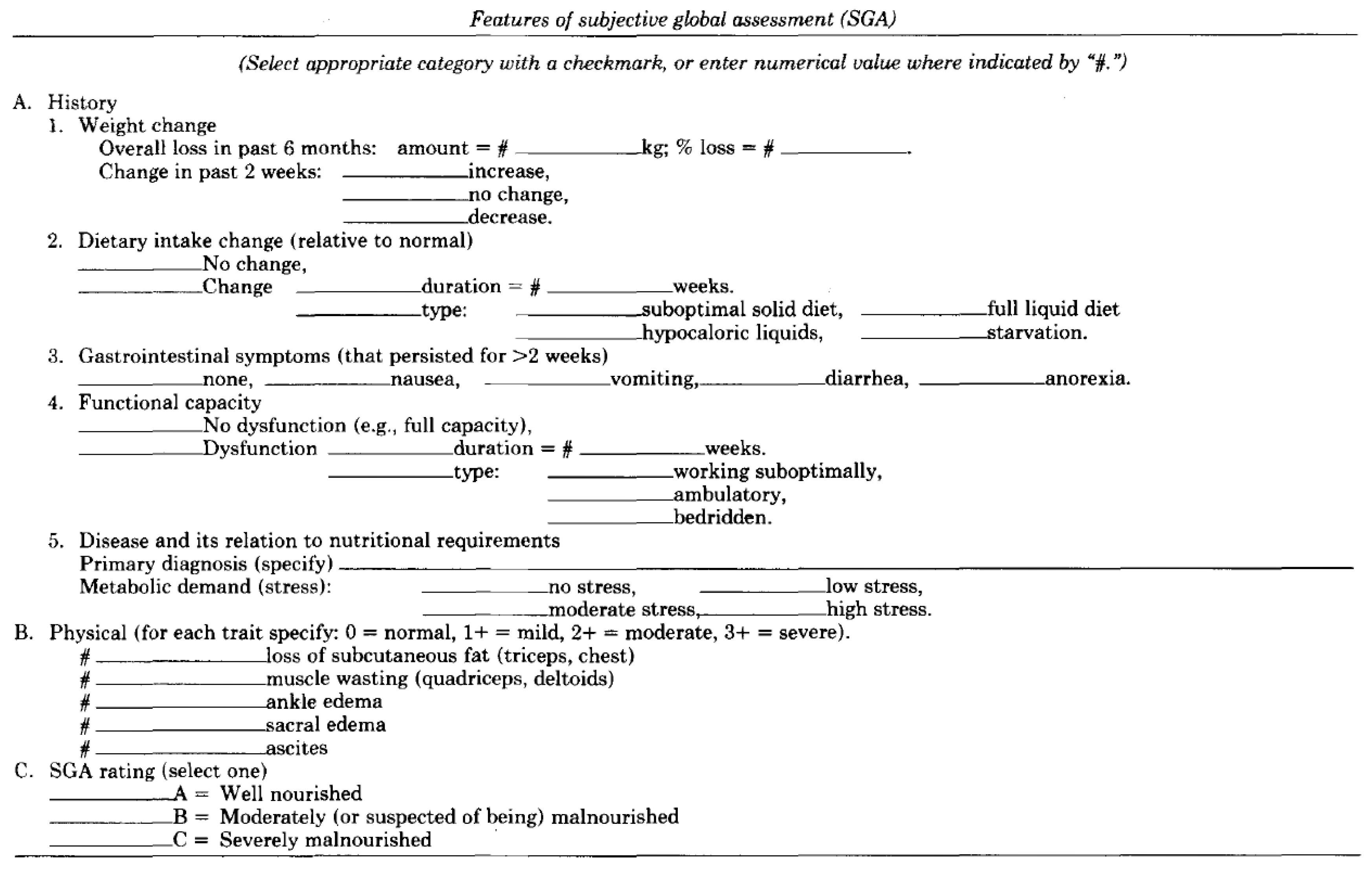

Appendix A.1. Subjective Global Assessment Form

Figure A1.

Subjective Global Assessment Form.

Figure A1.

Subjective Global Assessment Form.

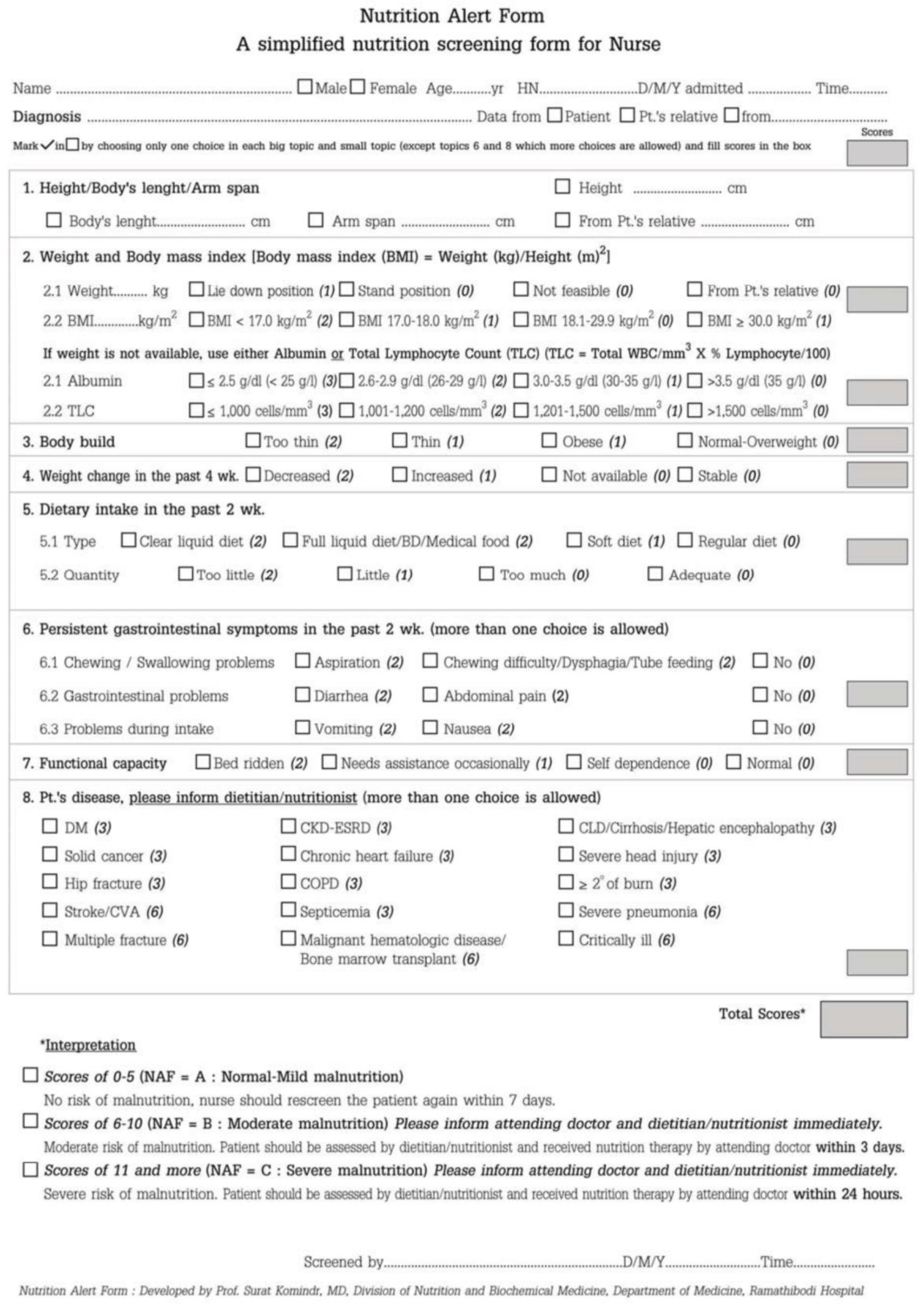

Appendix A.2. Nutrition Alert Form

Figure A2.

Nutrition Alert Form.

Figure A2.

Nutrition Alert Form.

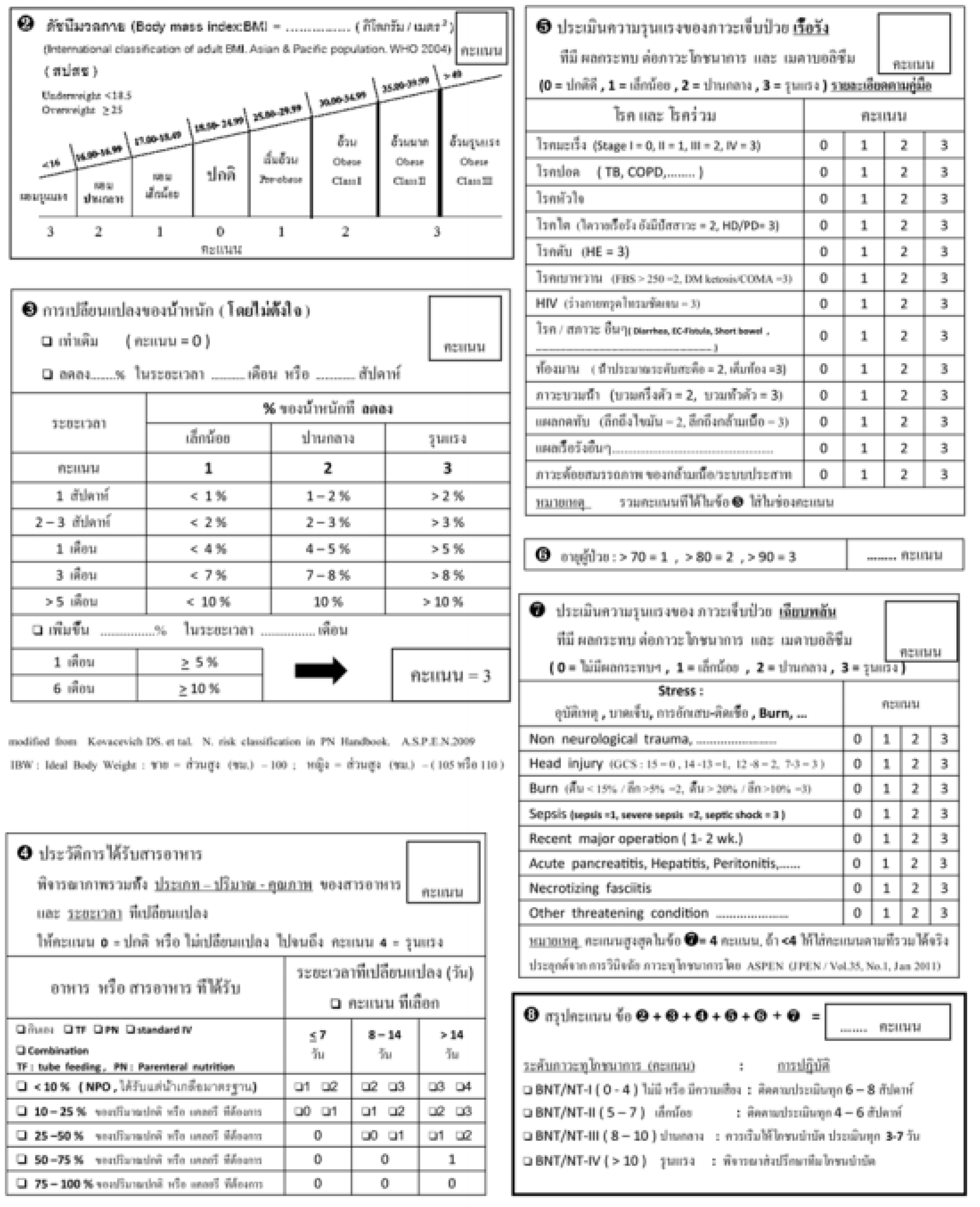

Appendix A.3. Nutrition Triage 2013

Figure A3.

Nutrition Triage 2013.

Figure A3.

Nutrition Triage 2013.

References

- Bairkdar M., Rossides M., Westerlind H., Hesselstrand R., Arkema E. V., Holmqvist M. Incidence and prevalence of systemic sclerosis globally: a comprehensive systematic review and meta-analysis. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2021;60(7):3121–33. [CrossRef]

- Bagnato G., Pigatto E., Bitto A., Pizzino G., Irrera N., Abignano G., et al. The PREdictor of MAlnutrition in Systemic Sclerosis (PREMASS) Score: A Combined Index to Predict 12 Months Onset of Malnutrition in Systemic Sclerosis. Front Med. 2021;8:651748. [CrossRef]

- Baron M., Hudson M., Steele R., Canadian Scleroderma Research Group. Malnutrition is common in systemic sclerosis: results from the Canadian scleroderma research group database. J Rheumatol. 2009;36(12):2737–43. [CrossRef]

- Denton C. P., Khanna D.. Systemic sclerosis. Lancet Lond Engl. 2017;390(10103):1685–99.

- Rubio-Rivas M., Royo C., Simeón C. P., Corbella X., Fonollosa V.. Mortality and survival in systemic sclerosis: systematic review and meta-analysis. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2014;44(2):208–19. [CrossRef]

- Harrison E., Herrick A. L., McLaughlin J. T., Lal S. Malnutrition in systemic sclerosis. Rheumatol Oxf Engl. 2012;51(10):1747–56.

- Murtaugh M. A., Frech T. M. Nutritional status and gastrointestinal symptoms in systemic sclerosis patients. Clin Nutr. 2013;32(1):130–5. [CrossRef]

- Preis E., Franz K., Siegert E., Makowka A., March C., Riemekasten G., et al. The impact of malnutrition on quality of life in patients with systemic sclerosis. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2018;72(4):504–10. [CrossRef]

- Baron M., Bernier P., Côté L. F., Delegge M. H., Falovitch G., Friedman G., et al. Screening and therapy for malnutrition and related gastro-intestinal disorders in systemic sclerosis: recommendations of a North American expert panel. Clin Exp Rheumatol. 2010;28(2 Suppl 58):S42-6.

- Wojteczek A., Dardzińska J. A., Małgorzewicz S., Gruszecka A., Zdrojewski Z. Prevalence of malnutrition in systemic sclerosis patients assessed by different diagnostic tools. Clin Rheumatol. 2020;39(1):227–32. [CrossRef]

- Cereda E., Codullo V., Klersy C., Breda S., Crippa A., Rava M. L., et al. Disease-related nutritional risk and mortality in systemic sclerosis. Clin Nutr. 2014;33(3):558–61. [CrossRef]

- Rosato E., Gigante A., Gasperini M. L., Proietti L., Muscaritoli M. Assessing Malnutrition in Systemic Sclerosis With Global Leadership Initiative on Malnutrition and European Society of Clinical Nutrition and Metabolism Criteria. J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 2021;45(3):618–24. [CrossRef]

- Komindrg S., Tangsermwong T., Janepanish P. Simplified malnutrition tool for Thai patients. Asia Pac J Clin Nutr. 2013;22(4):516–21. [CrossRef]

- Detsky A. S., McLaughlin J. R., Baker J. P., Johnston N., Whittaker S., Mendelson R. A., et al. What is subjective global assessment of nutritional status? J Parenter Enteral Nutr. 1987;11(1):8–13.

- Chittawatanarat K., Chaiwat O., Morakul S., Kongsayreepong S. Outcomes of Nutrition Status Assessment by Bhumibol Nutrition Triage/Nutrition Triage (BNT/NT) in Multicenter THAI-ICU Study. J Med Assoc Thai. 2016;99(Suppl. 6):S184-92.

- Schober P., Boer C., Schwarte L.A. Correlation coefficients: appropriate use and interpretation. Anesth Analg. 2018; 126: 1763–1768. [CrossRef]

- Landis J.R., Koch G.G. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics 1977; 33: 159–174.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).