3.1. Statistical assessment

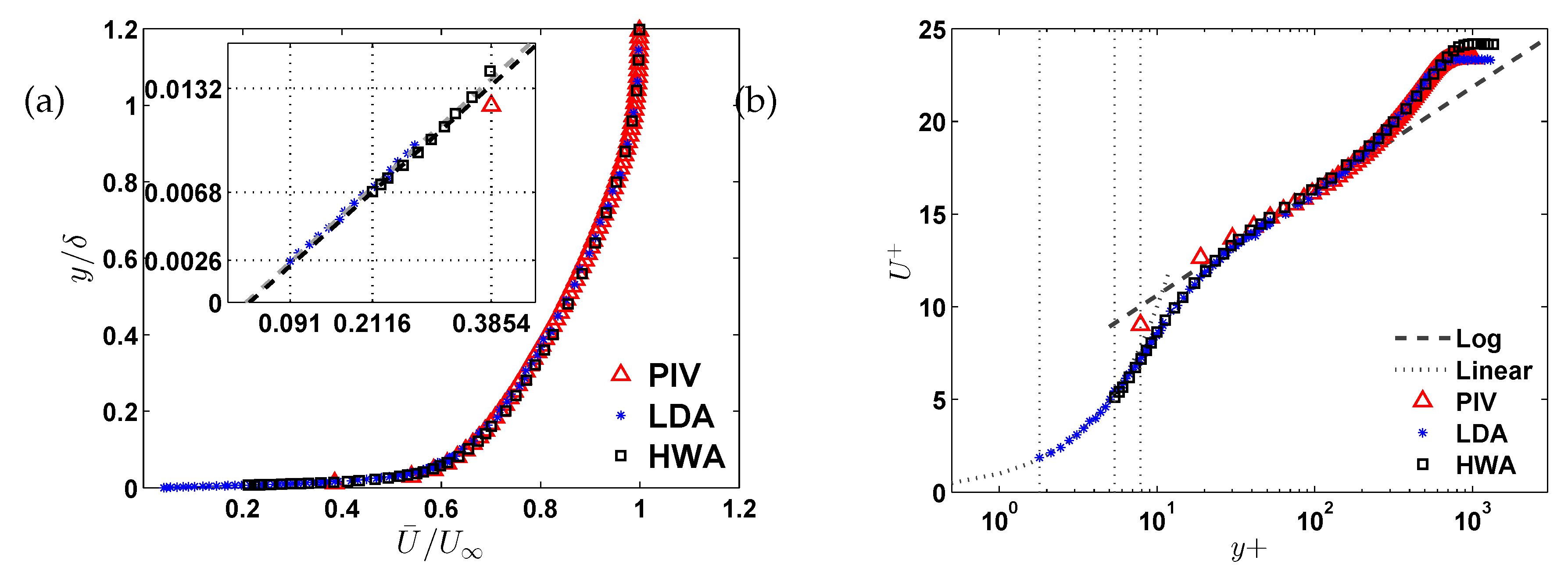

Figure 6(a) and (b) present the mean velocity profiles under SBL conditions using three different measurement techniques: PIV, LDA, and HWA. These methods correspond to wall-normal sampling densities of approximately

,

, and

points per meter, respectively. The averaging was done using Equation-

6 and . In

Figure 6(a), the velocity profiles are plotted using outer scaling parameters. PIV measurements are compared with reference LDA and HWA data from [

11] and [

23] respectively. The reference HWA profile corresponds to a turbulent boundary layer at

, which is slightly higher than that of the current LDA and PIV datasets, leading to small deviations in the outer region.

The inset in

Figure 6(a) highlights the near-wall region, illustrating the relative proximity of the first valid measurement points from each technique. LDA captures data closest to the wall, followed by HWA, whose first valid point is approximately 2.5 times further from the wall than that of LDA. The PIV technique captures its first point at approximately twice the distance of HWA’s, indicating its relatively coarser resolution in the near-wall region.

Figure 6(b) displays the same velocity profiles plotted using inner (viscous) scaling, i.e., normalized by the wall-shear velocity (

) and viscous length scale (

). The LDA and HWA datasets are scaled using their respective wall-shear stress measurements, while the PIV profile is scaled using the wall-shear stress estimated from LDA data at the same Reynolds number. Due to wall reflections, the first two data points obtained from the PIV measurements exhibit deviations in the overlap region.

Each viscous wall unit corresponds approximately to one micrometer, i.e.,

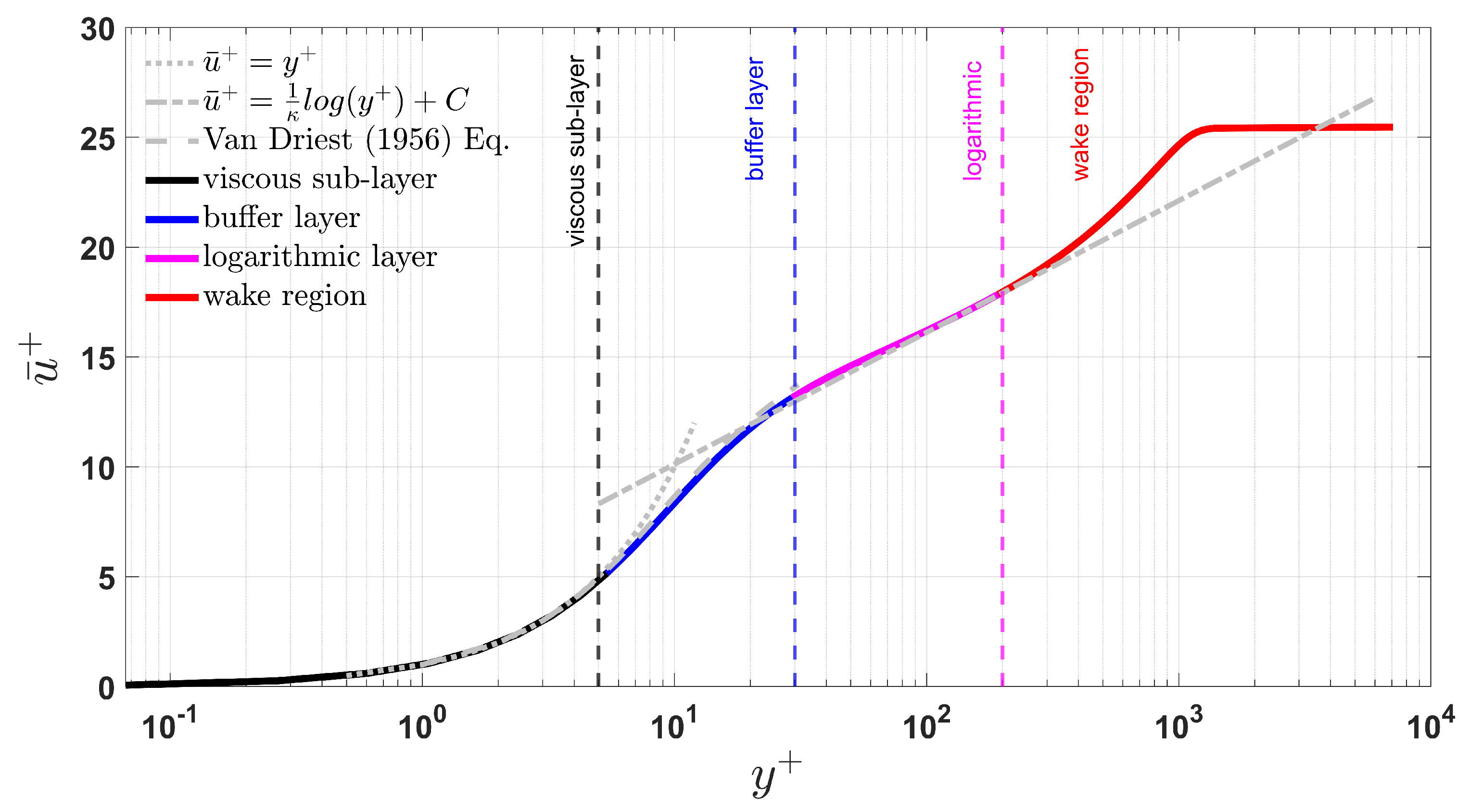

m. In both outer and inner scaling representations, the data from all three measurement techniques show excellent agreement throughout the boundary layer. Additionally, empirical relationships such as linear (Equation-

1) and logarithmic (Equation-

2) profile representations are included in both figures for comparison.

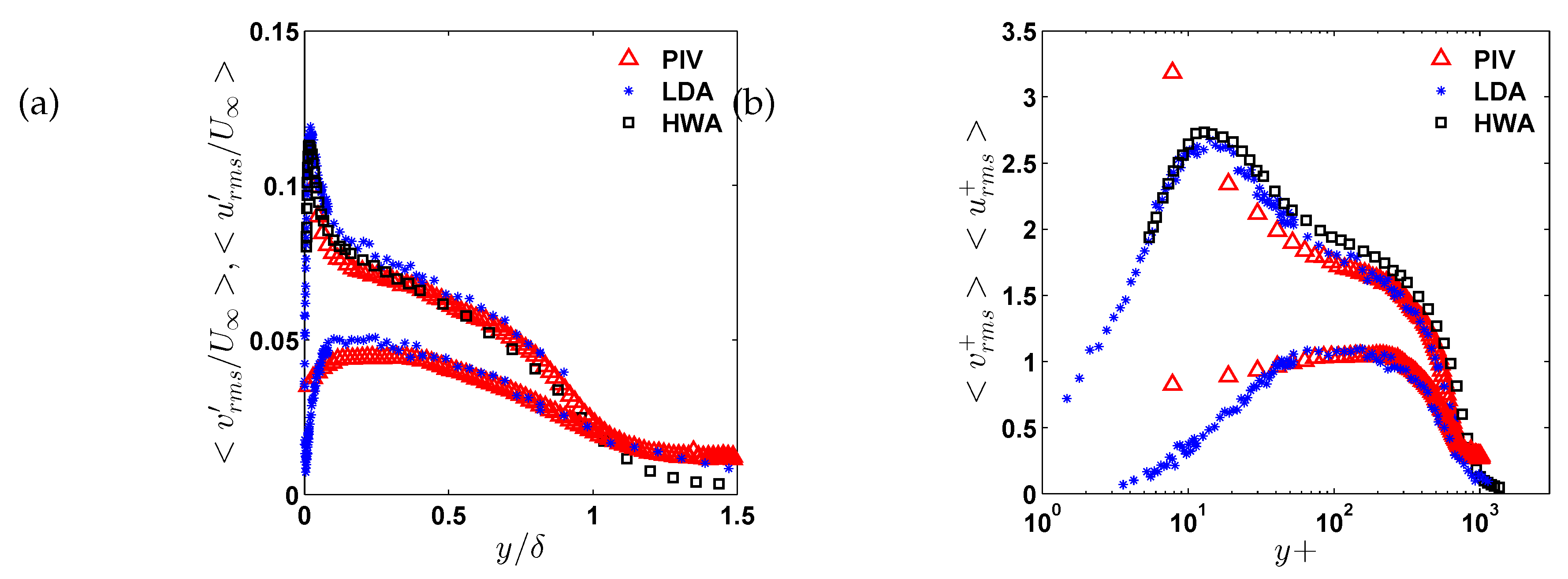

Higher-order moments of turbulent velocity fluctuations are presented in

Figure 7(a) and (b), plotted using outer and inner (viscous) scaling, respectively. The RMS of the velocity fluctuations was calculated using Equation for both the streamwise (

) and wall-normal (

) components. It is observed that

exhibits better accuracy and consistency compared to

. In particular, the agreement among all three measurement techniques is good within the outer region of the boundary layer.

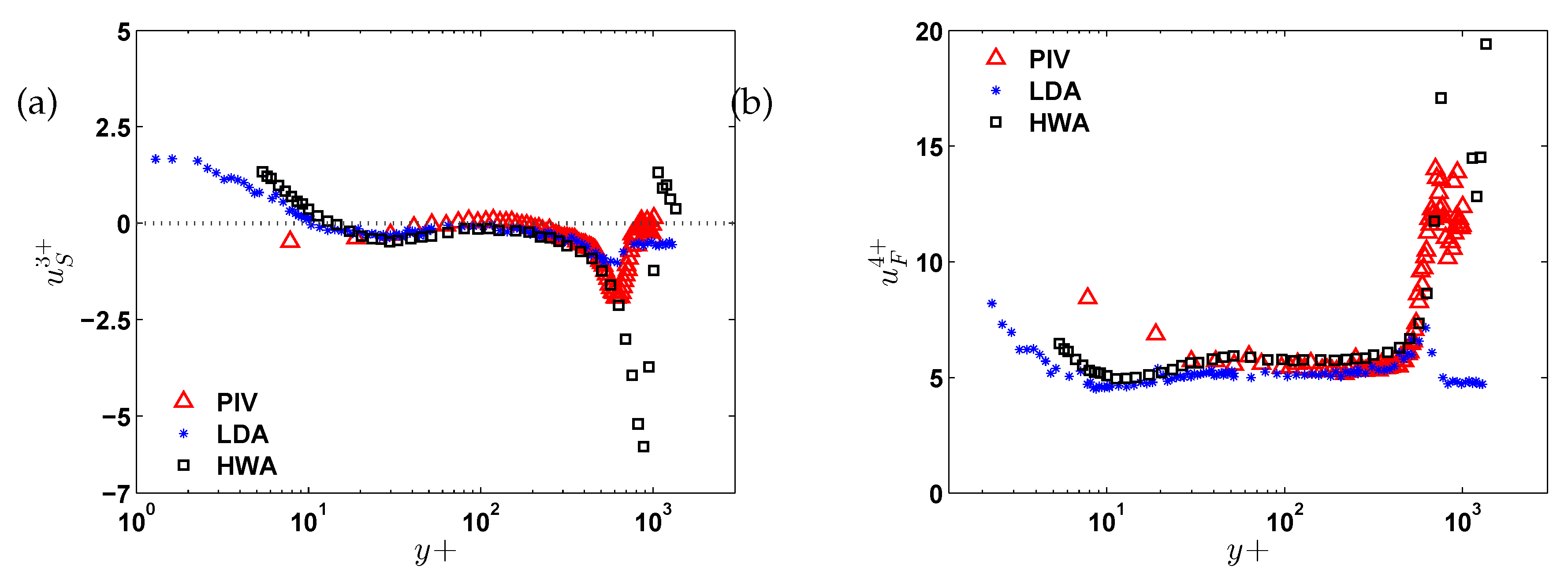

Furthermore, third- and fourth-order moments—skewness and flatness—of the streamwise velocity fluctuations are shown in

Figure 8(a) and (b), both plotted using viscous length scaling. Skewness (

) and flatness (

) were computed using Equations and , respectively. The skewness profiles generally show good agreement among the datasets, except in the near-wall region. However, flatness values from HWA deviate from those of LDA and PIV, likely due to the influence of higher Reynolds number effects in the HWA reference data.

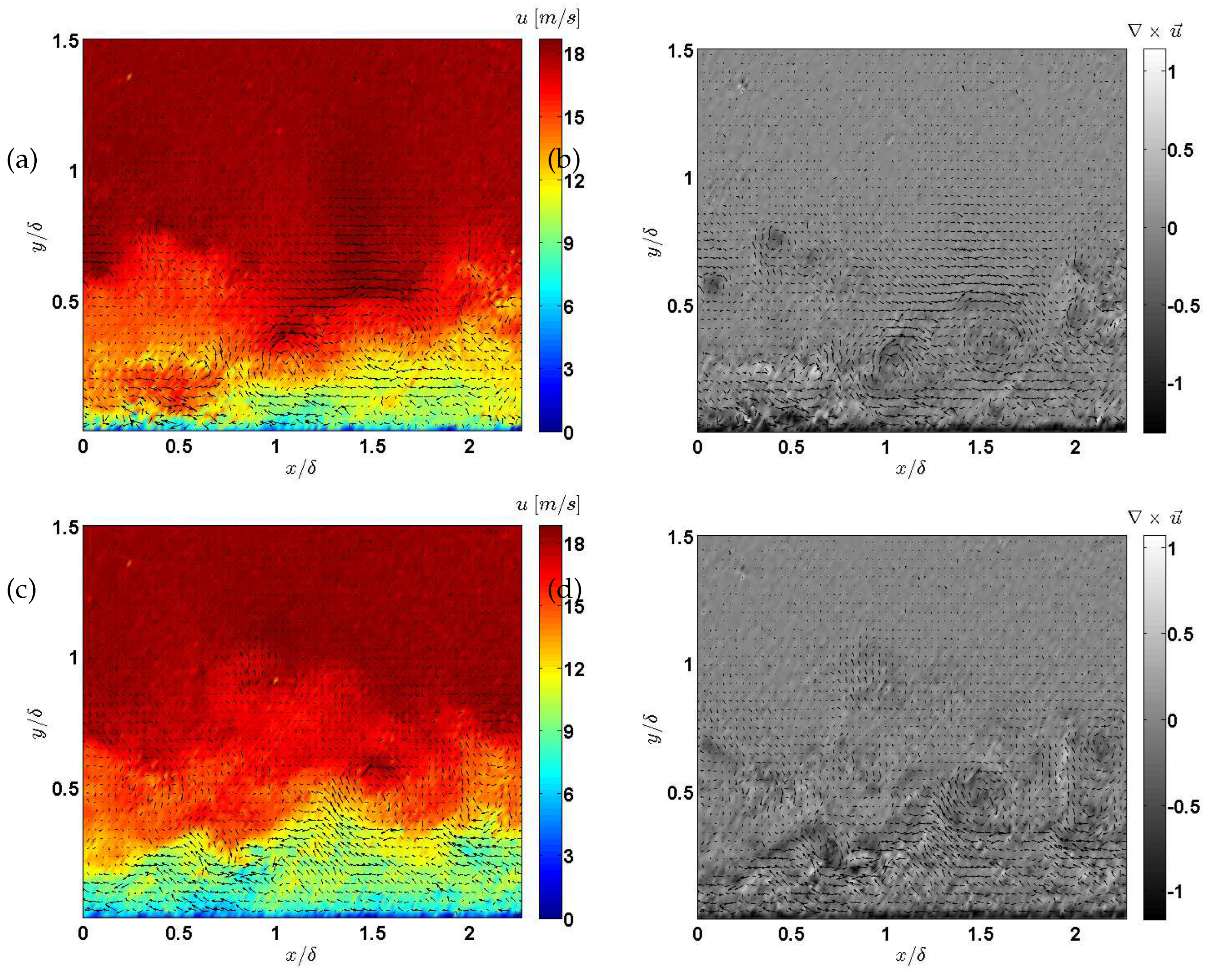

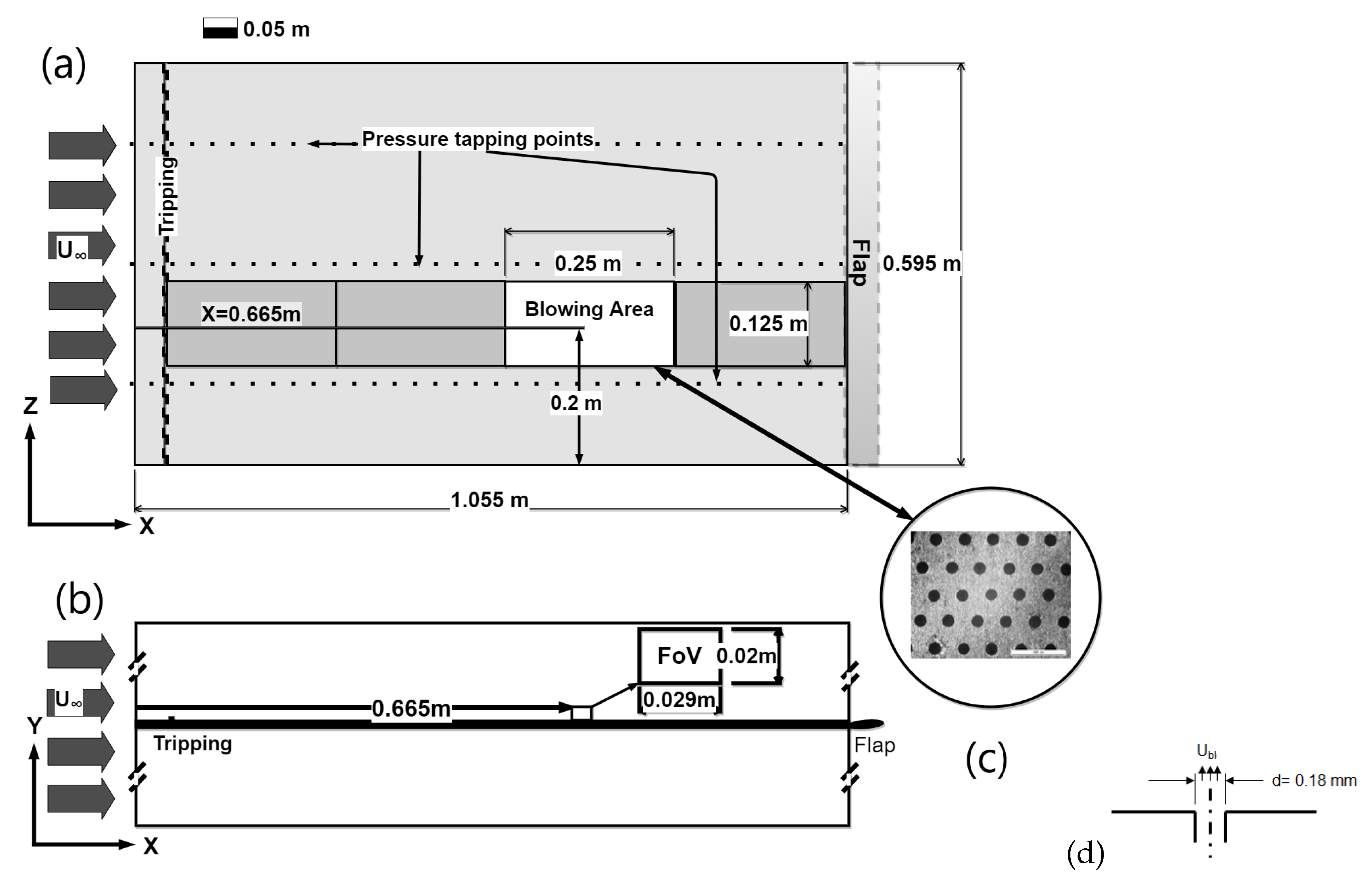

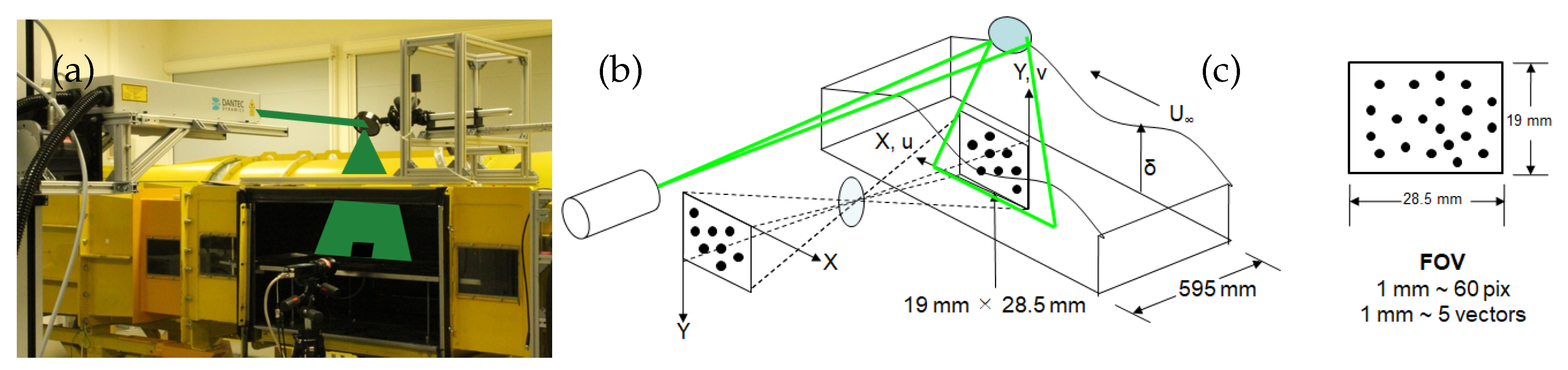

Figure 10(a) and (c) show the instantaneous velocity vector fields for the SBL and UB cases at

and

, respectively. The original velocity field consists of

vectors. For clarity, only every third vector in both the horizontal and vertical directions is plotted in

Figure 10(a) and (c). Arrows represent the local velocity vectors, computed from the horizontal and vertical components of the fluctuating velocity field. The background color contours display the instantaneous streamwise velocity component

u.

Figure 10(b) and (d) present the corresponding vorticity fields, computed as

, for the same SBL and UB cases shown in (a) and (c), respectively. While instantaneous velocity fields may not fully capture the statistical behavior of turbulence, they qualitatively illustrate the physical dimensions and structures of the resolved turbulent scales.

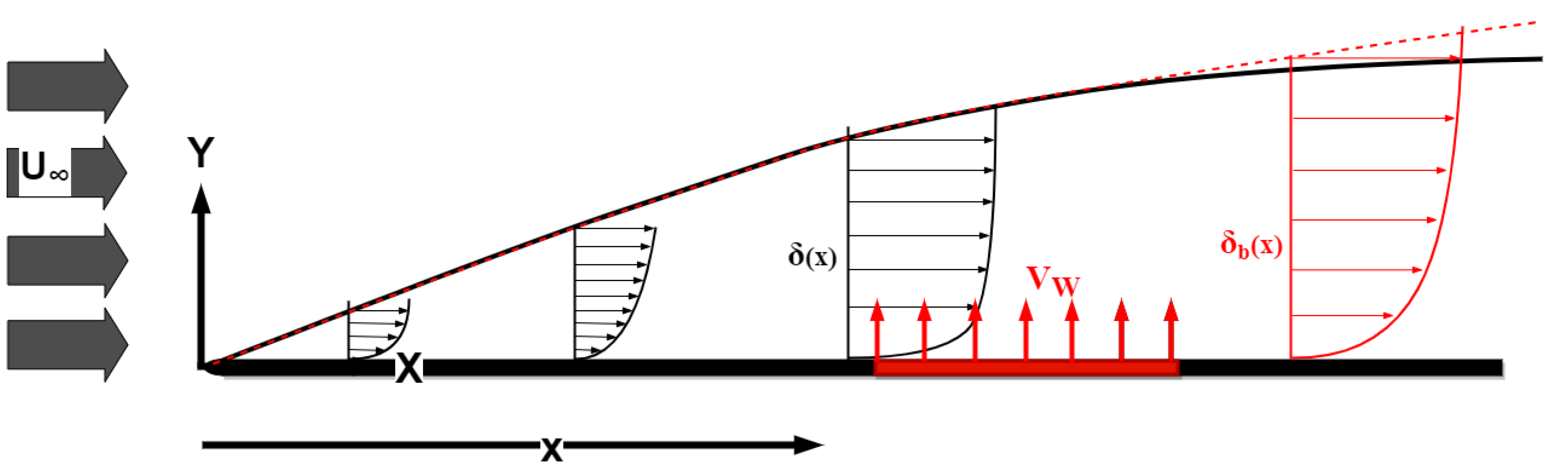

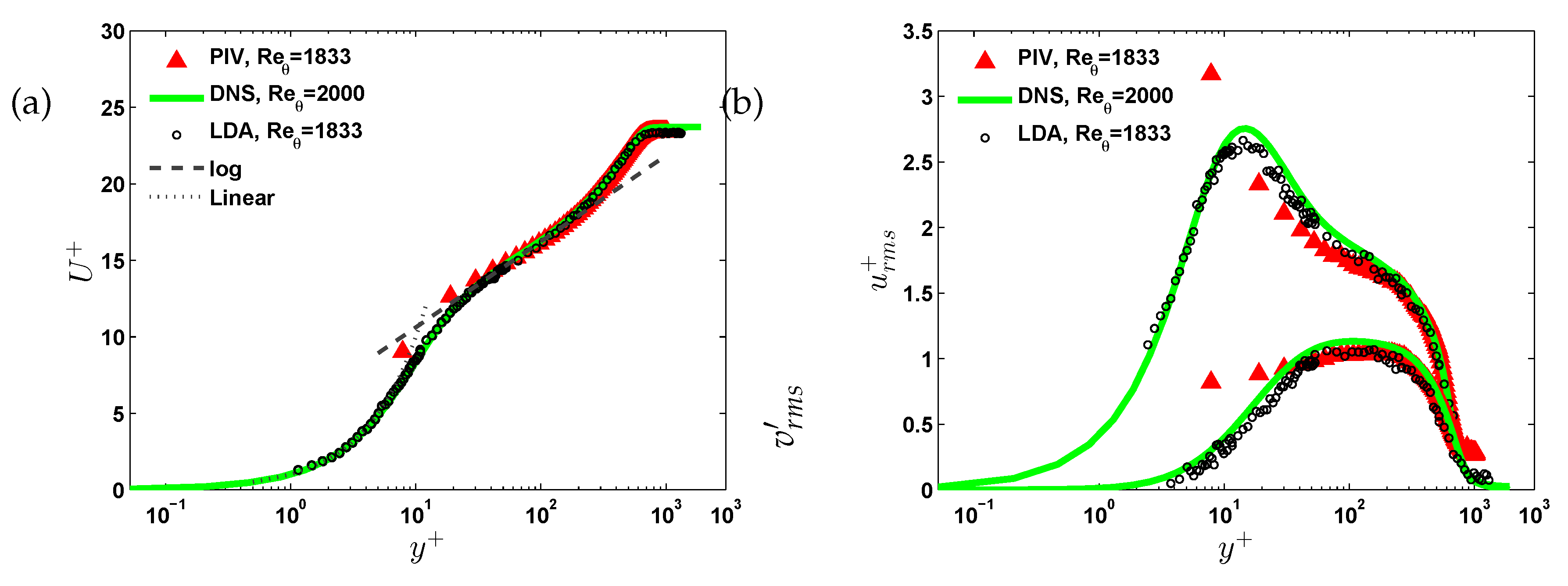

Experimental methods such as LDA and PIV are widely used for investigating TBLs, but both face inherent limitations in resolving the near-wall region, particularly for . This zone is characterized by steep velocity gradients and small-scale turbulence, which demand high spatial and temporal resolution. Such conditions pose challenges due to optical access constraints and measurement fidelity. Nonetheless, the near-wall region remains critically important for flow control strategies, drag-reduction techniques, and the development of wall-resolved turbulence models.

To evaluate the accuracy of experimental techniques in capturing this region,

Figure 9(a) and (b) compare the first- and second-order statistical moments of the streamwise velocity component. These measurements were obtained from PIV and LDA at

and are compared against Direct Numerical Simulation (DNS) data at

by Schlatter and Örlü [

25]. The LDA dataset used is from Hasanuzzaman et al. [

11] and serves as an experimental reference.

Figure 9(a) presents the mean velocity profiles (

versus

). The agreement between PIV, LDA, and DNS is excellent across the buffer and logarithmic regions. Notable deviations occur within the viscous sub-layer (

), where PIV fails to capture the sharp near-wall gradient. This is likely due to wall reflections and insufficient wall-normal resolution. LDA performs better in this region but still under-predicts velocity relative to DNS in the first few wall units, as it cannot fully resolve the smallest scales.

Figure 9(b) shows the rms of streamwise velocity fluctuations,

. The peak associated with buffer-layer turbulence is reasonably captured by LDA and DNS, while PIV underestimates this due to its lower spatial resolution. All three datasets show excellent agreement at the second peak (around

), corresponding to large-scale turbulent structures.

These observations suggest that for high-speed TBL flows with limited boundary layer thickness, LDA is more suitable for capturing near-wall small-scale dynamics, whereas PIV is better for resolving outer-layer structures over a larger field of view. The selection of measurement technique ultimately depends on a trade-off between spatial resolution, optical access, post-processing effort, and the specific flow features of interest.

3.2. Uniform Blowing

Figure 10 presents a comparative analysis of the instantaneous velocity and vorticity fields for SBL and UB conditions. While instantaneous velocity fields may not fully capture the statistical behavior of turbulence, they qualitatively illustrate the physical dimensions and structures of the resolved turbulent scales. The instantaneous velocity vector fields for the SBL and UB cases at

and

, respectively. The original velocity field consists of

vectors. For clarity, only every third vector in both the horizontal and vertical directions is plotted in

Figure 10(a) and (c).

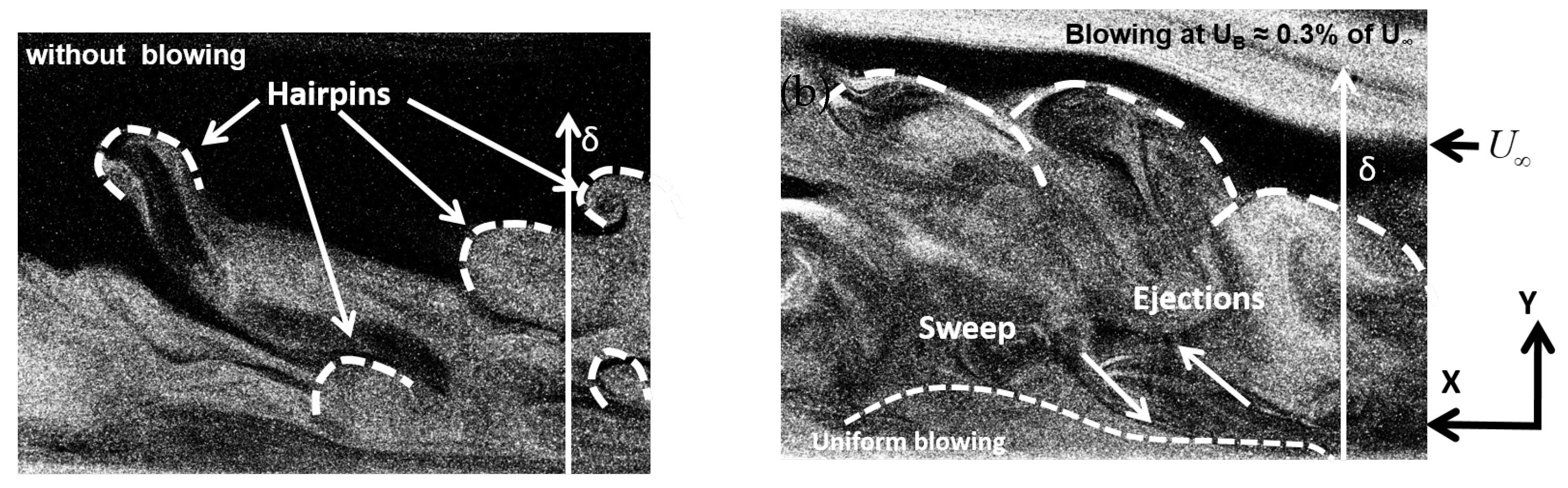

Figure 10 (a) and (c) show the instantaneous velocity vectors overlaid on contours of streamwise velocity for the SBL and UB cases, respectively. In the SBL case (a), the near-wall region (

) exhibits low-speed streaks and inclined vectors that are characteristic of coherent structures in turbulent boundary layers. The velocity magnitude increases with wall-normal distance, transitioning into a more uniform and aligned streamwise flow. In contrast, the UB case in sub-figure (c) shows a visibly thickened boundary layer and a broader near-wall mixing region. The streamwise velocity contours are displaced upward, and the vector field reveals disrupted coherence, indicating that wall-normal momentum injection alters the turbulence structure and interferes with the regeneration cycle of near-wall streaks and vortices.

The corresponding vorticity fields in sub-figures (b) and (d) further highlight the effects of uniform blowing. The vorticity fields were computed as . In the SBL case (b), vorticity is concentrated near the wall, revealing compact and localized vortical structures that dominate the near-wall turbulence production. Conversely, the UB case (d) displays a more diffuse and vertically distributed vorticity field, signifying a weakening and redistribution of vortical structures due to the imposed blowing. This broader distribution is consistent with theoretical predictions of drag reduction mechanisms via uniform blowing, where the near-wall cycle is disrupted, and the peak turbulence production is pushed away from the wall.

Figure 10.

(a) Instantaneous vector plots of velocity components with contours of streamwise velocity at SBL condition, (b) Vorticity of the velocity vectors at SBL conditions, (c) Vector plots of velocity components with contours of streamwise velocity at UB, (d) orticity of the velocity vectors at UB conditions.

Figure 10.

(a) Instantaneous vector plots of velocity components with contours of streamwise velocity at SBL condition, (b) Vorticity of the velocity vectors at SBL conditions, (c) Vector plots of velocity components with contours of streamwise velocity at UB, (d) orticity of the velocity vectors at UB conditions.

These qualitative observations align well with the statistical moment analysis conducted using transit-time-weighted LDA data. The altered velocity and vorticity structures observed in the UB case suggest modified profiles of root-mean-square fluctuations, reduced skewness, and lower flatness, particularly near the wall. Overall, the figures illustrate how uniform blowing modulates turbulence by thickening the boundary layer, reducing the coherence of near-wall structures, and redistributing vorticity—key mechanisms that contribute to friction drag reduction.

Shear flows are reflection of the wall condition. The quantitative friction co-efficient at SBL and different UB rates were measured from the direct measurements using reference LDA.

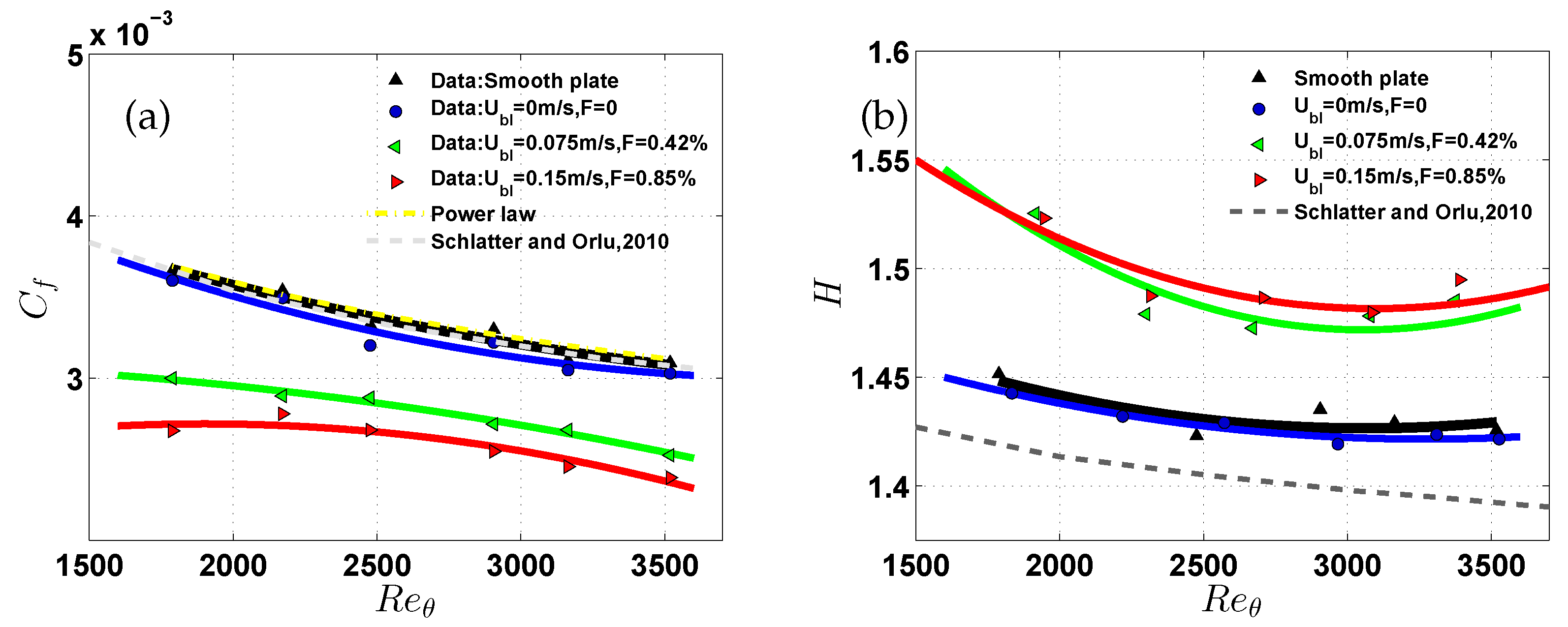

Figure 11.

(a) Friction co-efficient

, (b) Shape factor (

) against reference

. In both the figures gray dashed line indicate DNS data from [

25].

Figure 11.

(a) Friction co-efficient

, (b) Shape factor (

) against reference

. In both the figures gray dashed line indicate DNS data from [

25].

Figure 11(a) presents the streamwise evolution of the friction coefficient (

) plotted against the momentum-thickness Reynolds number (

) for different wall-normal blowing velocities. The baseline case, denoted by black triangles, represents SBL conditions and serves as the reference for comparison. Overlaid are experimental data corresponding to UB applied through a perforated wall at different fixed wall-normal velocities:

m/s (no blowing, blue circles),

m/s (green left-pointing triangles), and

m/s (red right-pointing triangles), corresponding to blowing ratios of 0%, 0.42%, and 0.85%, respectively.

To isolate the effect of uniform blowing on skin-friction drag,

values are plotted against the

from the reference SBL configuration. This ensures that any reduction in

due to blowing is not masked by the inherent increase in

caused by boundary layer thickening. The reference smooth wall data is compared with two benchmarks: the power-law model proposed by Smits et al. (1983) [

20] with a constant

, and experimental data from Schlatter and Örlü (2013) [

25], which slightly underpredict the

trend, likely due to measurement limitations in the near-wall region.

The present SBL data (black triangles and blue circles) show good agreement with the Smits power-law trend [

20]. The case with perforated wall but no blowing (blue circles) shows only a minor deviation, suggesting that surface perforation alone has a negligible impact on wall-shear stress. However, once uniform blowing is introduced (green and red curves), a clear reduction in

is observed. At

m/s, the

curve shifts downward, and at

m/s, the reduction becomes more pronounced, reaching values close to

below the baseline.

Interestingly, although blowing thickens the boundary layer (increasing ), the reduction in does not grow proportionally. This is because the blowing velocity is fixed, while the boundary layer momentum increases with streamwise distance, effectively reducing the blowing ratio (F). This decline in F with increasing explains why the drag-reducing effect plateaus beyond , and then gradually decreases at higher .

Moreover, the

measurement uncertainty increases at higher

, primarily due to fewer valid data points within the viscous sublayer (as shown in

Figure 8(c), not displayed here), where accurate slope detection for wall-shear estimation becomes more difficult. This limitation impacts the reliability of

values above

.

Although not explicitly shown in this figure, uniform blowing also induces significant changes to integral boundary layer properties such as boundary layer thickness (

), displacement thickness (

or

), momentum thickness (

), and shape factor (

H), as documented in Hasanuzzaman (2021) [

5].

Figure 11(b) shows the evolution of the boundary layer shape factor, defined as

, with respect to

for various UB conditions. In this figure, legend indication is the same as

Figure 11(a) The shape factor is a critical indicator of boundary layer structure, reflecting the relative fullness of the velocity profile—higher values generally correspond to thicker boundary layers with stronger velocity deficits near the wall.

The SBL reference case shows a monotonic decrease in

H with increasing

, consistent with the expected development of a turbulent boundary layer. This trend is well aligned with the no-blowing perforated surface (blue circles), which exhibits negligible deviation, confirming that surface perforation alone does not alter the boundary layer structure significantly. Both these cases also align closely with the empirical data of [

25], shown by the dashed-gray line.

In contrast, when uniform blowing is applied through the perforated wall—at BR, % and % a marked increase in the shape factor is observed across the full range of . This trend reflects the fact that wall-normal momentum injection opposes the normal boundary layer development, resulting in a fuller velocity profile with increased displacement thickness () relative to momentum thickness ().

Interestingly, the H values under blowing conditions show a non-monotonic trend: they decrease slightly with up to around 2500, then level off or slightly increase. This is attributed to the fixed blowing velocity (), which leads to a decreasing blowing ratio () as the free-stream velocity and boundary layer momentum increase with . As a result, the influence of blowing becomes less dominant at higher Reynolds numbers, leading to a plateauing of the shape factor.

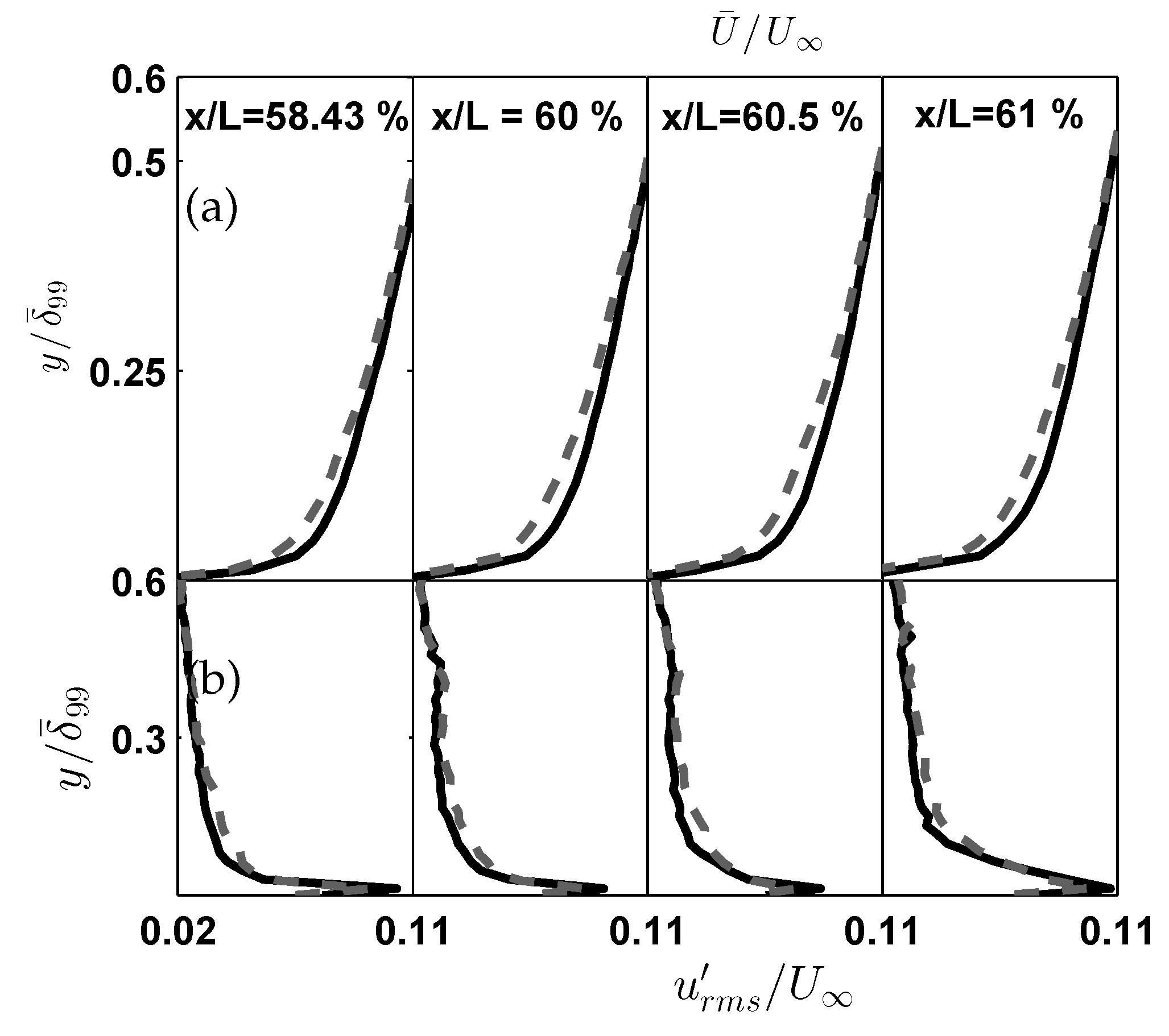

Figure 12.

Spatial development of the TBL thickness () at different downstream stations, comparing SBL and UB, where, SBL is indicated with ’’ and UB at blowing ratio, F = 0.85% is indicated with ’– –’ (a) outer-scaled mean velocity profiles, (b) outer-scaled mean rms profiles of streamwise fluctuations.

Figure 12.

Spatial development of the TBL thickness () at different downstream stations, comparing SBL and UB, where, SBL is indicated with ’’ and UB at blowing ratio, F = 0.85% is indicated with ’– –’ (a) outer-scaled mean velocity profiles, (b) outer-scaled mean rms profiles of streamwise fluctuations.

Additionally, the observed shape factor values in the UB cases (

–

) remain higher than the SBL values (

–

), consistent with the presence of an external momentum source (e.g UB). These results support earlier findings by Hasanuzzaman (2021) [

5], which reported that uniform blowing leads to substantial modification of integral boundary layer properties, not just local skin-friction reduction.

Figure 13 presents (a) outer-scaled mean streamwise velocity (

) and (b) streamwise turbulence intensity (

) profiles along wall distance at different downstream stations e.g

. The canonical SBL profile is shown as solid black line, while the UB case at

is represented by gray dashed line. Wall-normal distance is normalized by

.

The analysis of velocity profiles reveals characteristic modifications induced by uniform blowing. As shown in

Figure 13(a), the UB case exhibits three distinct influences, (1) boundary layer thickening, with discernible deviations from the canonical profile for

, (2) Enhanced turbulence intensity (

) in the outer region (

) and (3) potential viscous sub-layer stabilization (

).

UB at F=0.85% modifies the TBL structure without flow separation, aligning with the outcomes suggested by Hasanuzzaman et al (2020)[

10] and Hasanuzzaman et al (2016)[

8]. Quantify the displacement thickness change (

) to highlight control efficiency. These observations suggest increased vertical momentum transfer while maintaining attached flow conditions at this blowing ratio. The spatial consistency across multiple streamwise locations (

) confirms the stochastic equilibrium of the flow. This behavior aligns with previous studies of low-momentum injection, though quantitative assessment of

would further clarify the control effectiveness.

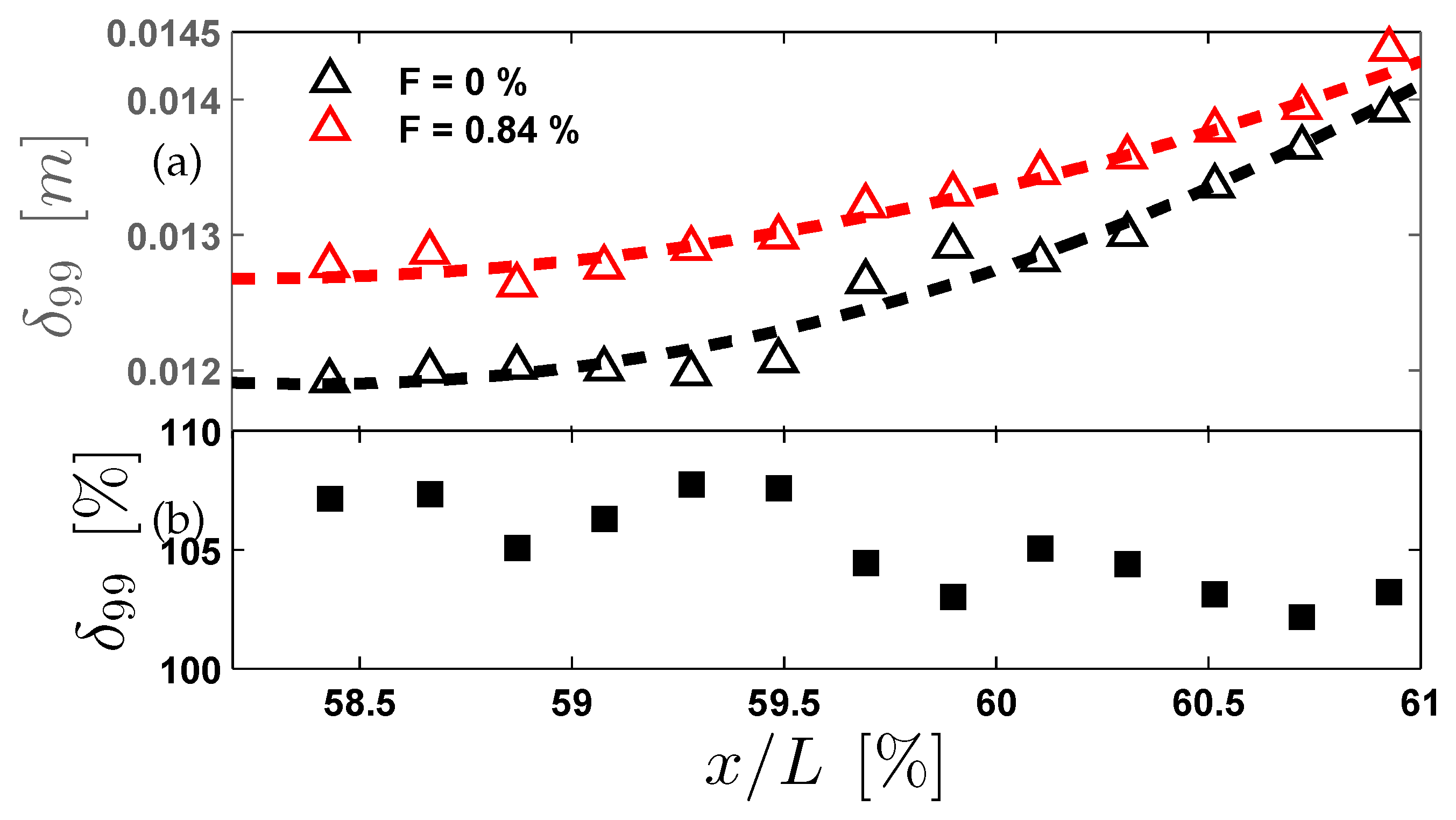

Figure 13 quantifies the streamwise development of boundary layer thickness under upstream blowing conditions. Figure-

Figure 13(a) plots the dimensional streamwise evolution of

and (b) exhibits the percentile increase in

relative to SBL. This figure proposes the observations that include, Evolution of

e.g. the UB at

shows progressive

growth, reaching

thicker than SBL at

, decaying to

by

. This confirms the downstream persistence of blowing effects while demonstrating spatial decay (

).

The stochastic decay rate of the

where the percentage increase in

follows a near-linear reduction from 0.0145 to 0.012 over the measured domain (

), suggesting an empirical relationship different from the classic power-law formula (see footnote for

in Section-

Section 1). In order to define the stochastic decay, the following empirical relationship is suggested,

. When comparing to the SBL

, the reference case (black) maintains constant

within measurement uncertainty. These results demonstrate that even modest blowing (

) produces measurable BLT modifications that persist for

downstream. The observed decay rate provides empirical data for future scaling laws of blowing effectiveness in ZPGTBL flows.

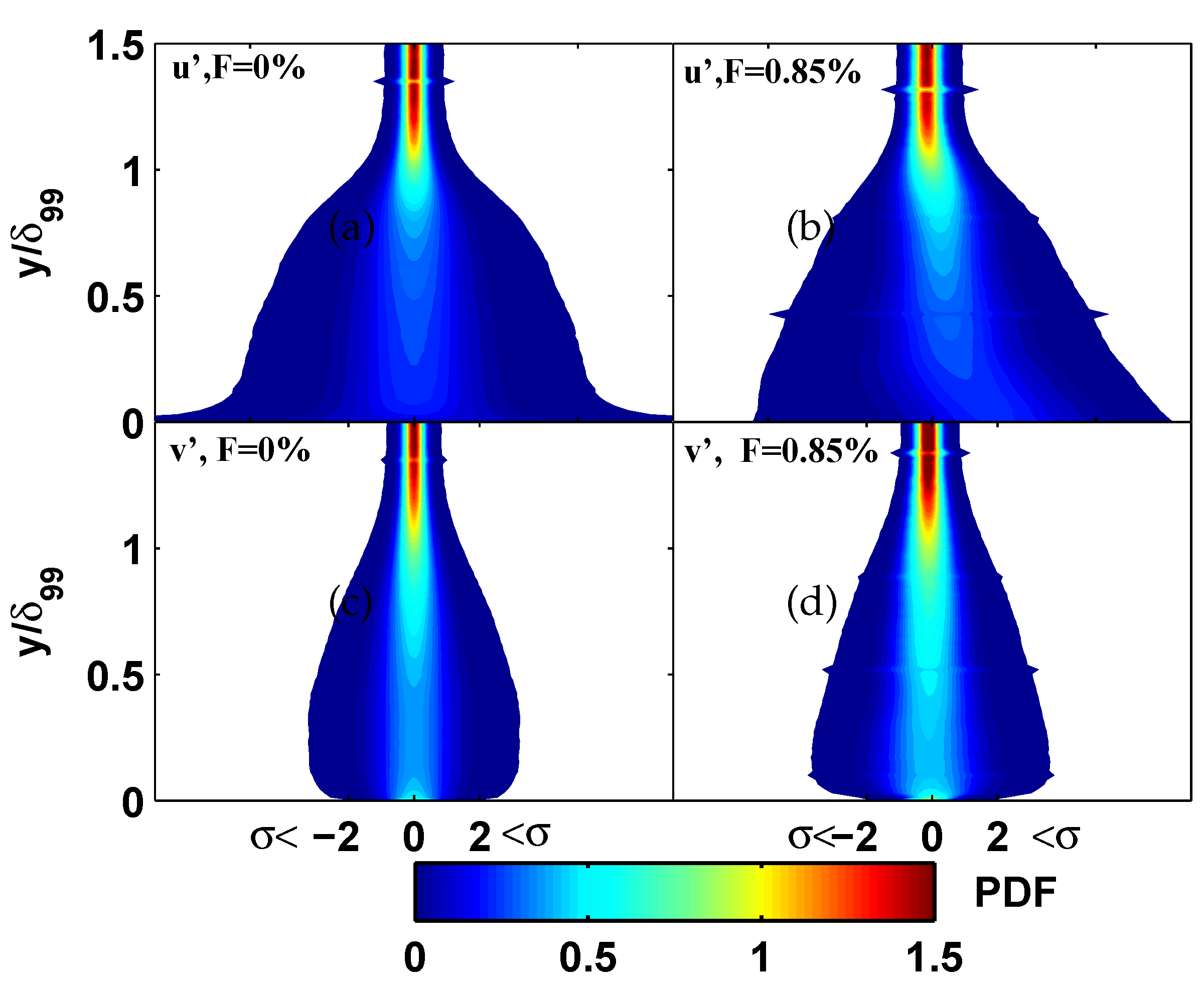

Figure 14 presents the probability density functions (PDFs) of the streamwise (

) and wall-normal (

) velocity fluctuations. The top row of

Figure 14 shows the PDFs of streamwise velocity fluctuations (

), while the bottom row shows the PDFs of wall-normal fluctuations (

). In both cases, the left column represents the SBL condition, and the right column corresponds to the UB case. The PDFs are normalized by their respective standard deviations and are color-coded based on PDF magnitude, with red indicating the most probable fluctuations and blue denoting lower probability.

The PDFs of velocity fluctuations reveal distinct modifications induced by UB at compared to the SBL. For streamwise fluctuations (), UB broadens the PDF peak (variance increase ) and introduces negative skewness (), indicating enhanced turbulent mixing and preferential acceleration events.

Wall-normal fluctuations () exhibit more pronounced changes, developing bimodal tendencies wher shoulders at and increased kurtosis (), suggesting UB promotes intermittent ejection/sweep events. These modifications reflect fundamental changes in the Reynolds stress gradient , where UB enhances vertical momentum transport while maintaining the overall ZPGTBL structure. The results, obtained from 240 PIV snapshots () at , demonstrate that even modest blowing () significantly alters the turbulence statistics, particularly in the wall-normal component. Measurement uncertainty was constrained to e.g 95% confidence level.

In the SBL case (top-left), exhibits a narrow, symmetric core centered around zero across the boundary layer thickness (), with the highest probability density occurring in the logarithmic and buffer regions. The spread of fluctuations increases toward the outer layer, indicative of the presence of large-scale structures. Under UB conditions (top-right), the overall profile becomes slightly broader and more asymmetric, especially in the outer region. This suggests enhanced mixing and increased intermittency, likely due to the disruption of coherent near-wall structures by the injected wall-normal momentum.

For (bottom row), the PDFs in both cases are more sharply peaked near the wall (), indicating relatively low wall-normal fluctuation amplitudes in the near-wall region. The SBL case (bottom-left) maintains a compact and symmetric structure, while the UB case (bottom-right) shows a modest broadening of the PDF distribution across the boundary layer height. This broadening reflects the impact of uniform blowing, which enhances vertical momentum transport and modifies turbulence anisotropy.

Overall, the figure illustrates that uniform blowing at introduces measurable changes in the statistical structure of both and fluctuations, consistent with the anticipated drag-reducing and turbulence-modifying effects of wall-normal momentum injection.

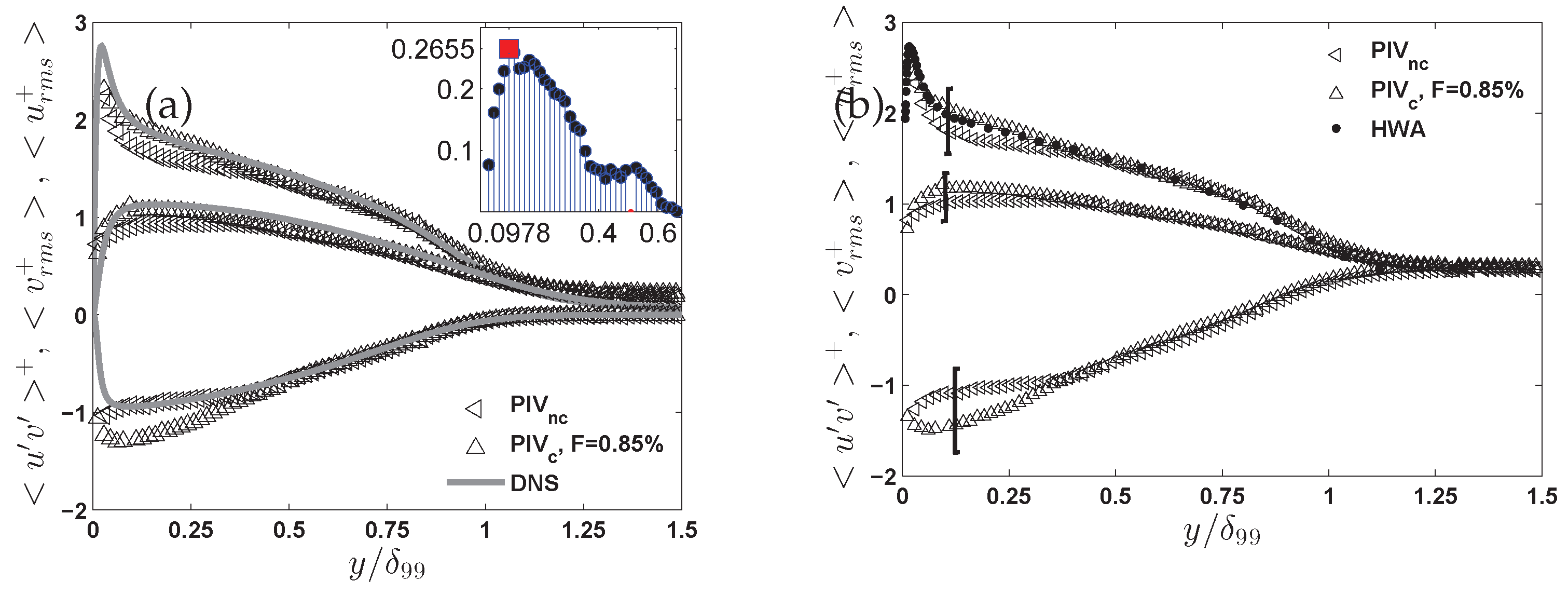

The Reynolds stress profiles demonstrate significant modifications under UB when benchmarked against SBL datasets. As shown in

Figure 15(a), the uncontrolled PIV data (

) exhibits excellent agreement with DNS predictions from Schlatter and Örlü (2013)[

25] in the logarithmic region (

), with deviations limited to

at

. The UB case (

) shows approx. 22% peak stress enhancement (at

), indicating increased turbulent momentum transport. In order to explain this figure, one has to consider the fact that Reynolds number for the measured data (

) is much lower than the reference DNS data. This indicates that the stochastic influence of UB can modify the BL profile similar to the velocity statistics at a higher Reynolds number.

The same data is plotted in

Figure 15(b), where, comparison with HWA data from [

23] reveals consistent trends despite the higher

reference condition e.g the UB profile maintains the characteristic SBL shape but shifts upward systematically, with maximum stress amplification (

) occurring in the buffer layer (

). This confirms that even modest blowing (

) sustains enhanced turbulence production across the boundary layer while preserving the outer-layer similarity. The dual validation against DNS and HWA establishes that these effects are physical rather than artifacts of the PIV measurement technique or Reynolds number differences.

Figure 15 presents the Reynolds stress components normalized in wall units

,

, and the Reynolds shear stress

—as a function of wall-normal position

for both SBL and UB cases. Open triangles represent PIV data, where

corresponds to the no-control SBL case and

corresponds to the controlled case with uniform blowing at

of the free-stream velocity.

In the left subfigure, the PIV data are compared with DNS results from Schlatter and Örlü (2013) [

25] at

. The DNS data (gray lines) exhibit canonical turbulent boundary layer behavior, serving as a high-fidelity reference. The agreement between DNS and

is quite good, especially in the outer region (

), for all three stress components. In the near-wall region, slight discrepancies are observed, particularly in the peak of

, which is under-predicted by PIV due to limited spatial resolution and near-wall optical distortions. The UB case (

) shows a clear suppression of all three Reynolds stress components across the boundary layer, with the effect being strongest in the near-wall and buffer regions. This reflects a weakening of turbulent activity and momentum transport as a result of wall-normal momentum injection.

The right subfigure compares the same PIV data with HWA measurements from Österlund [

23] at

. Despite the Reynolds number mismatch, the trends remain consistent. The HWA data show a slightly higher near-wall peak in

, capturing finer-scale fluctuations that are typically under-resolved by PIV. However, the overlap between HWA and SBL is still reasonable across much of the boundary layer. The suppression effect of uniform blowing on turbulence intensity and Reynolds shear stress is again evident in UB, confirming that UB significantly alters the turbulence structure by reducing wall-shear stress and turbulence production mechanisms near the wall.