1. Introduction

Parkinson's disease (PD) is the second-most common neurodegenerative disorder that affects 2–3% of the population aged ≥65 years [

1]. PD is mainly characterized by dopaminergic neurons degeneration in the substantia nigra pars compacta (

SNpc), significantly decreasing the dopamine content in the caudate nucleus and putamen [

2]. Neurodegeneration is associated with the cardinal symptoms of PD, characterized by resting tremor, rigidity, bradykinesia, and a subsequent loss of postural reflexes that impair gait [

3]. Likewise, non-motor symptoms characterized by neuropsychiatric symptoms include emotional disturbances, cognitive impairment, sleep disorders, and autonomic dysfunction, among others; these are some of the symptoms that appear many years before movement disorders [

4]. Among the main neurochemical alterations present in the nigrostriatal pathway of PD patients are the aggregation of α-synuclein, increased intraneuronal iron content in the

SNpc, a 30-40% decrease in the activity of Complex I of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, decreased antioxidant response, increased formation of free radicals, and oxidative stress [

5,

6]. Likewise, microglia activation participates in dopaminergic neuronal damage through the production of interleukin-1β (IL-1β) and tumor necrosis factor alpha (TNF-α) [

7].

1-Methyl-4-phenylpyridinium (MPP+) is one of the foremost neurotoxins used to induce the main neurochemical characteristics of PD. Its neurotoxic potential is based on its selective damage to dopaminergic neurons through the inhibition of complex I of the mitochondrial electron transport chain, alterations in signaling pathways, overproduction of free radicals, oxidative stress, and reduction of dopamine (DA) content [

8]. MPP+-induced murine model of PD exacerbates neuroinflammation by activating microglia, producing interleukin (IL)-17A, and partial release of TNF-α [

9]. Moreover, COX-2 and IL-1β transcripts are significantly elevated in BV-2 microglial cells exposed to conditioned medium of MPP+-treated neuron-restrictive silencer factor/repressor element 1 (RE1)-silencing transcription factor (NRSF/REST) deficient astrocytes compared to WT astrocytes [

10]. MPP+ induces the generation of IL-6, IL-1β, and TNF-α in BV-2 microglial cells. Likewise, MPP+ increases the phosphorylation of the PI3K/AKT/GSK-3β pathway, generates reactive oxygen species (ROS), as well as the activation of p65, and induces the activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome and caspase-1 [

11].

Simvastatin (Sim) is a statin that has been indicated as an inhibitor of HMG-CoA reductase, the main enzyme in the synthesis of cholesterol, lipid-lowering agents [

12], and protects against atherosclerosis disease [

13]. Statins have also been considered as neuroprotective agents [

14,

15]. Sim was found to induce the differential expression of antioxidant enzymes in ventral midbrain [

14]. Moreover, Sim could prevent the neurotoxic damage produced by lipopolysaccharide (LPS)-induced inflammatory processes [

16]. Similarly, it has been indicated that Sim exerts a neuroprotective effect by regulating energy metabolism [

17]. However, despite the aforementioned background is still unknown the proteomic changes induced by Sim in specific brain nuclei, such as the ventral midbrain and striatum, which are key elements in the pathophysiology of PD.

The midbrain, also called the mesencephalon, is a part of the central nervous system that first develops on E9 and gives rise to the dorsal and ventral midbrain [

18]. The embryonic development of the midbrain is of considerable interest to scientists hoping to find better forms of treatment for PD. The midbrain functions as a relay system, transmitting information necessary for vision and hearing. It also plays an important role in motor control, pain, and the sleep/wake cycle.

This study is oriented at analyzing the effect of Sim on the proteomic profile of the ventral midbrain in a murine model of PD induced by intra-striatal administration of MPP+, to identify key proteins involved in neuroprotection, thus contributing to the understanding of the possible mechanisms underlying the neuroprotective effects of Sim in PD and exploring its potential as a promising therapeutic alternative in patients with this condition.

2. Results

2.1. Circling Behavior, Fluorescent Lipidic Products, and Dopamine Content in Striatal Tissue

In order to support our results, all these parameters were measured to ensure Parkinson’s-like disease in animals. Approximately 6 days after intrastriatal MPP+ infusion, we observed a marked effect on circling behavior induced by apomorphine administration (151.1 ± 18.3 turns/60 min;

p < 0.001) compared to control groups (vehicle and saline; Sim and saline), as shown in

Table 1. Sim pretreatment statistically reduced the number of turns induced by MPP+ (45.5 ± 21.3 turns/60 min;

P < 0.001) (

Table 1). MPP+-infusion increased the formation of lipid fluorescent products versus to the control group (40.1 ± 4.18 vs.17.2 ± 2.88 FU/mg protein, respectively;

P < 0.0001).

Table 1 also shows the neuroprotective effect of Sim pre-administration (40 mg/kg/day) on fluorescent lipidic products as compared to the MPP+- treated group (23.4 ± 3.25 vs. 40.1 ± 4.18 FU/mg protein, respectively;

P < 0.001). No statistical difference was observed between the MPP+/Sim and control groups (23.4 ± 3.25 vs.17.2 ± 2.88 FU/mg protein, respectively). Basal levels of striatal DA were 61.6 ± 3.91 μmol/g wet tissue. Sim pre-administration did not affect striatal DA levels (65.8 ± 6.5 μmol/g). In contrast, after MPP+ microinjection, a significant decrease (

P < 0.001) in DA concentrations were found (20.6 ± 3.1 μmol/g), whereas Sim pre-administration in MPP+-treated rats produced a significant (

P < 0.03) preservation of DA content (47.3 ± 8.4 μmol/g) (

Table 1).

2.2. Neurodegenerative Damage

Finally, MPP+-induced damage significantly reduced the positive signal for tyrosine hydroxylase (TH) compared to the control group (

P = 0.001). This damage was significantly reduced by the sub-chronic Sim administration (

P = 0.005). Finally, similar levels of positive signal for striatal TH in the Sim and control groups were found (

Table 1).

2.3. Protein Expression Patterns from the Rat’s Mesencephalon

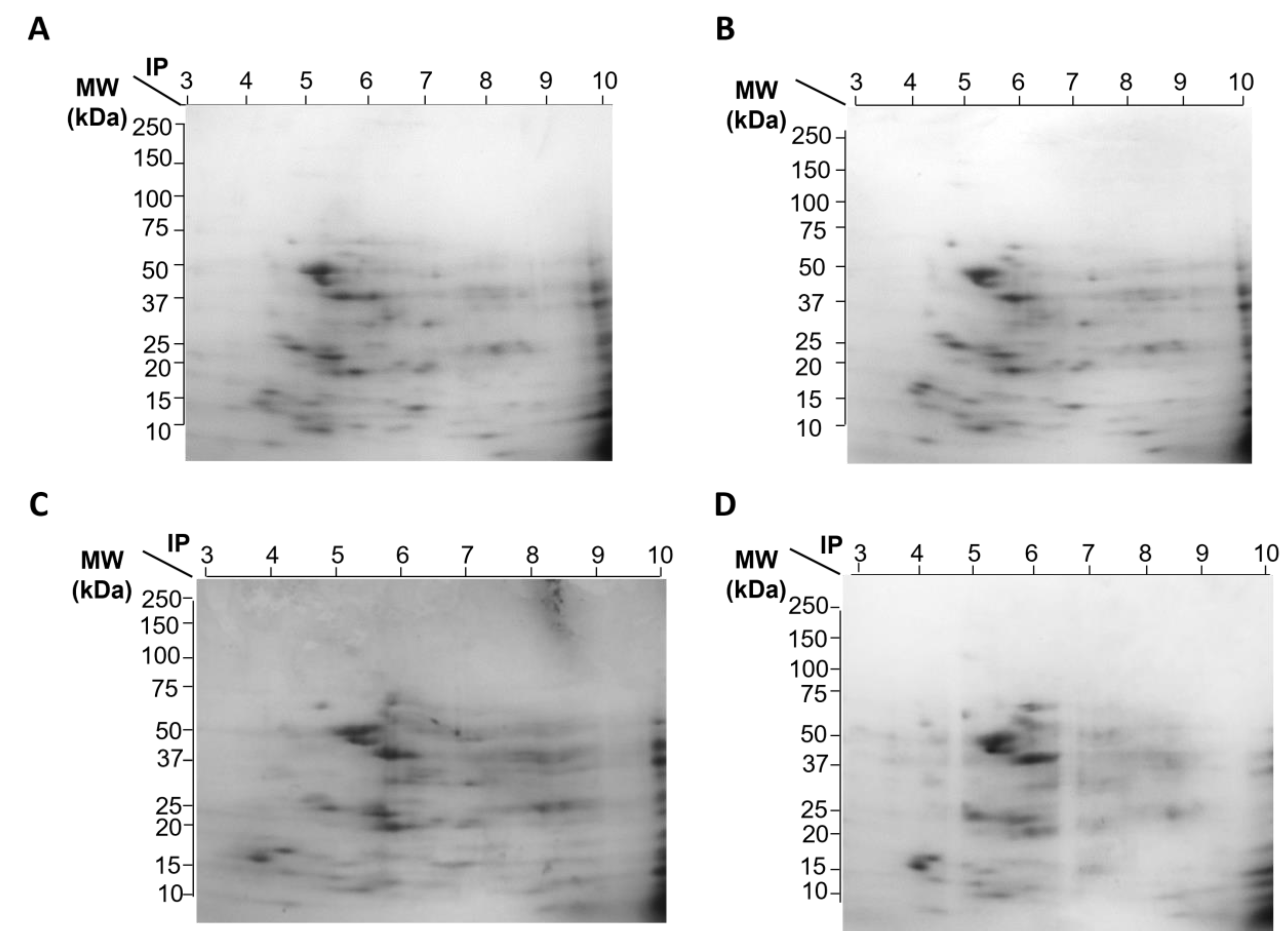

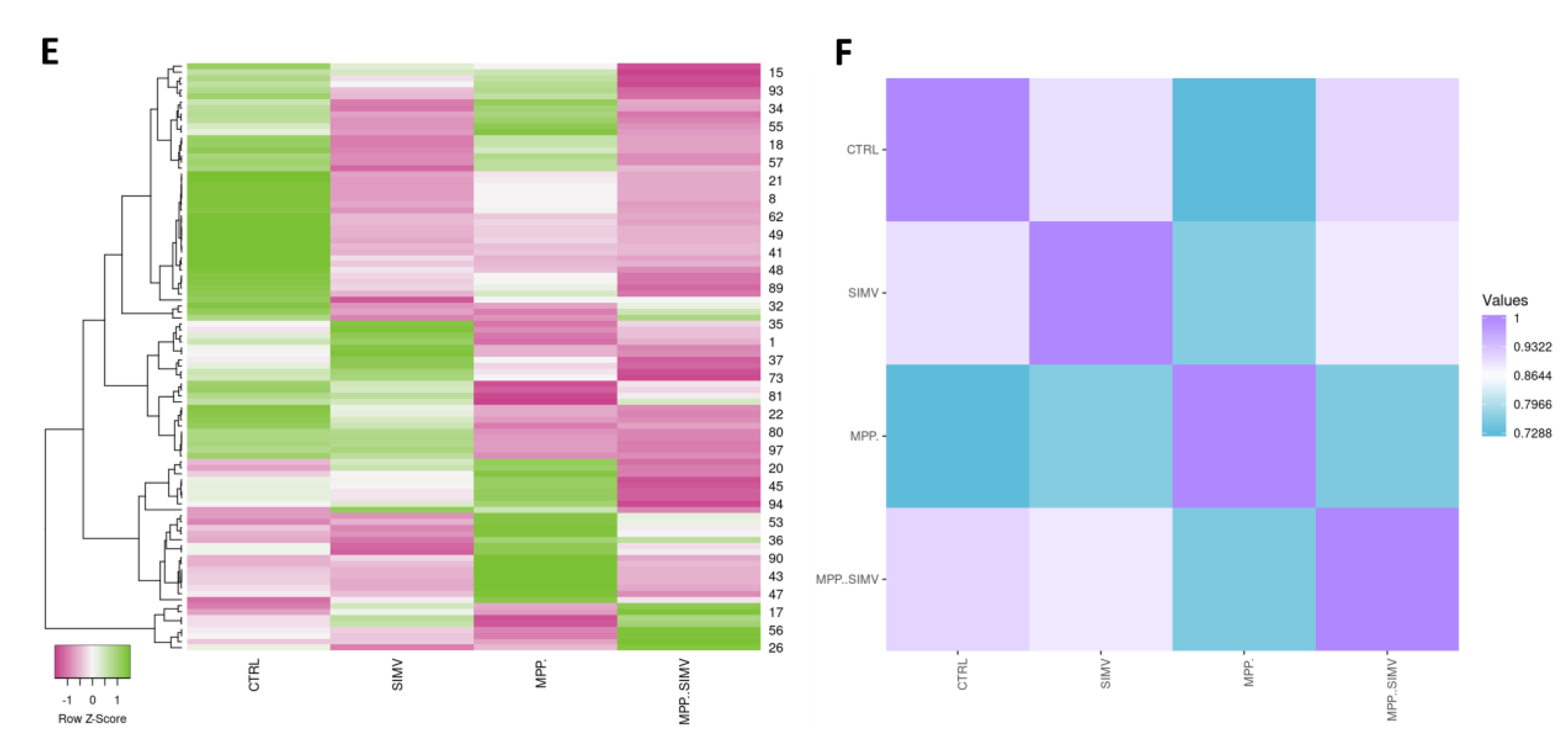

Representative gel images of the 4 experimental groups are shown in

Figure 1, which depicts A) Control group without treatment, B) Group treated with Sim, C) Group treated with MPP

+, and D) Group treated with Sim and MPP

+. We have previously reported that MPP+/simvastatin-treated rats exhibited differential expression of antioxidant enzymes, where most proteins related to inflammation decreased, suggesting that Sim could prevent striatal damage induced by MPP+. In order to dissect particular differences in protein expression from VMB, a 2DE proteomic analysis was performed. As depicted in

Figure 1 and

Table 2, a different protein profile was found in each experimental group. The initial analysis showed that the total number of spots was decreased in the Sim-treated samples, as deduced by the number of total spots of 2D gels, while the group exposed to MPP+, without Sim, exhibited the greatest number of spots (

Figure 1A-D and

Table 2). Despite MPP+/Sim and control groups exhibiting a high similarity with a 0.911 correlation (

Figure 1F), proteins that are highly expressed in the control group exhibited a reduced expression in MPP+/Sim group (

Figure 1E).

In general, all groups showed a greater number of downregulated proteins compared to control (

Table 2).

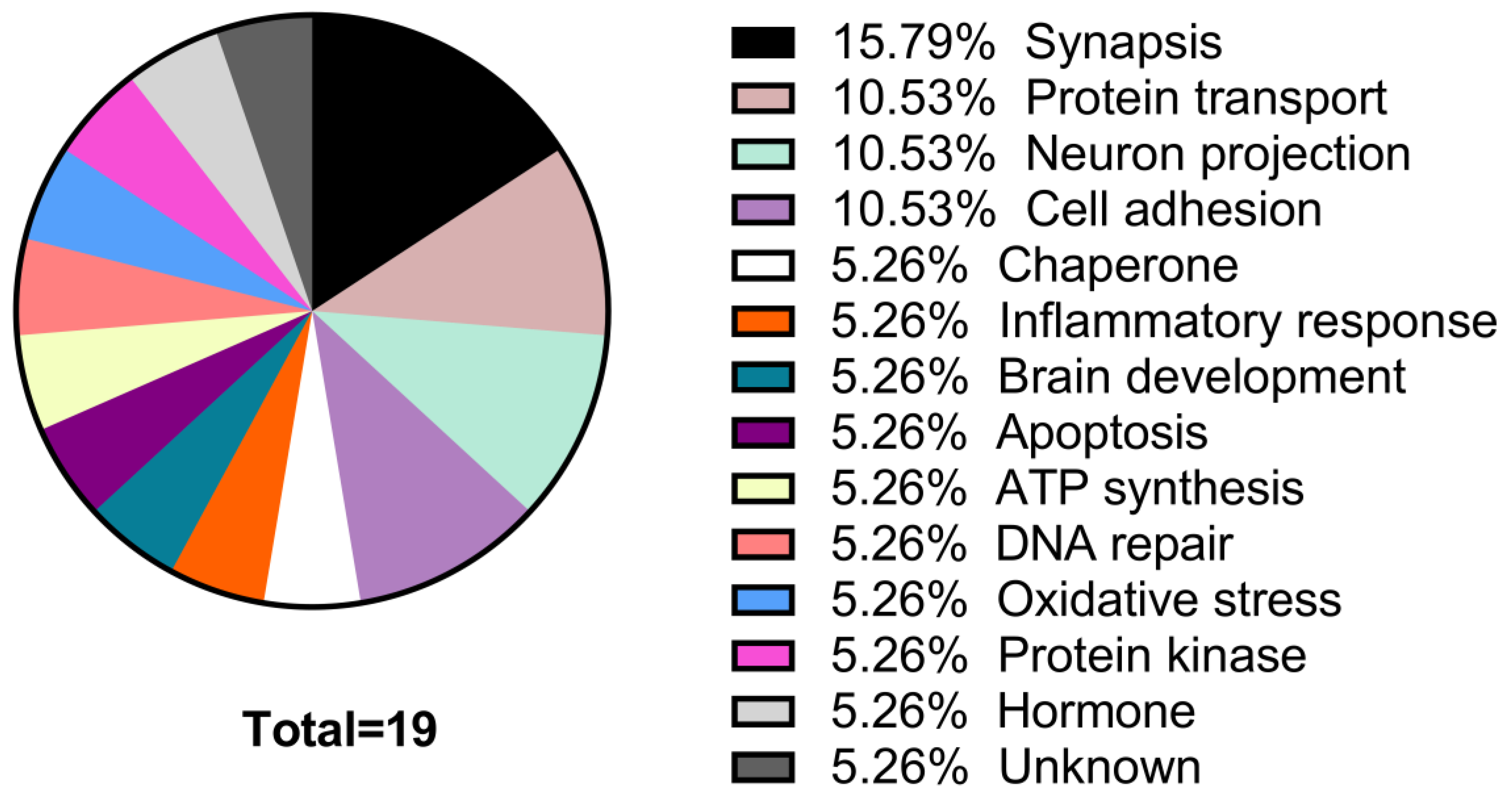

2.4. In Silico Protein Identification

We aimed to propose a probable identification of proteins based on comparative spot analysis, as described in the Methods section. Proteins whose expression diminished or increased by at least 1.5 fold, for all groups compared to control, and we could find a probable identification, are listed in

Table 3 and

Table 4. The proteins whose expression decreases in MPP+/Sim group are mainly involved in functions of synapses, neuron projection, protein transport, and cell adhesion, while those whose expression increased are mainly proteins involved in endocytosis, axogenesis, and ATP synthesis (

Table 3 and

Figure 2).

In

Table 4, there is a list of Sim-induced increases in protein expression. The neurotoxin MPP+ reproduces most of the biochemical and pathological hallmarks of Parkinson’s disease, such as inflammation by oxidative stress and the production of ROS by activation of the NADPH-oxidase complex.

Some proteins that are involved in MPP+ inflammation response identified in the MPP+ group were Platelet-derived growth factor D (Pdgfd), Insulin-like growth factor 1 (Ilgf), IL-1, GPX1, and Interferon alpha-1 (IFN-1) (

Table 4). As apoptosis promotes neuroinflammation and neuronal degeneration in neurodegenerative pathologies such as Parkinson’s disease, we focused the search on proteins that are related to the establishment of inflammation responses (

Table 4). Platelet-derived growth factor D (Pdgfd) is a protein involved in leukocyte migration and, more interestingly, is involved in cell survival via ERK pathway and indirectly by the brain-derived neurotrophic factor pathway. The expression of this protein was reduced in rats treated with Sim. Insulin-like growth factor I (Igf1), a protein involved in the positive regulation of T cell proliferation, positively regulates IL-4, Jun, and Bcl-2 pathways while negatively regulating TNF, IL-1, Casp3, Bax, and NFb1. The expression of Igf1 was reduced in rats exposed to the MPP+ toxin. TGF-3 and TGF-1 exhibited a similar expression profile. TGF-1 is involved in the positive regulation of glial cell differentiation, and both proteins regulate inflammatory responses (

Table 4). Additionally, TGF-1 has shown protective activity against MPP+ injury in the rat model. We found that MPP+ administration resulted in a reduction in TGF- 1 production in the substantia nigra and primary VMB neurons and microglia.

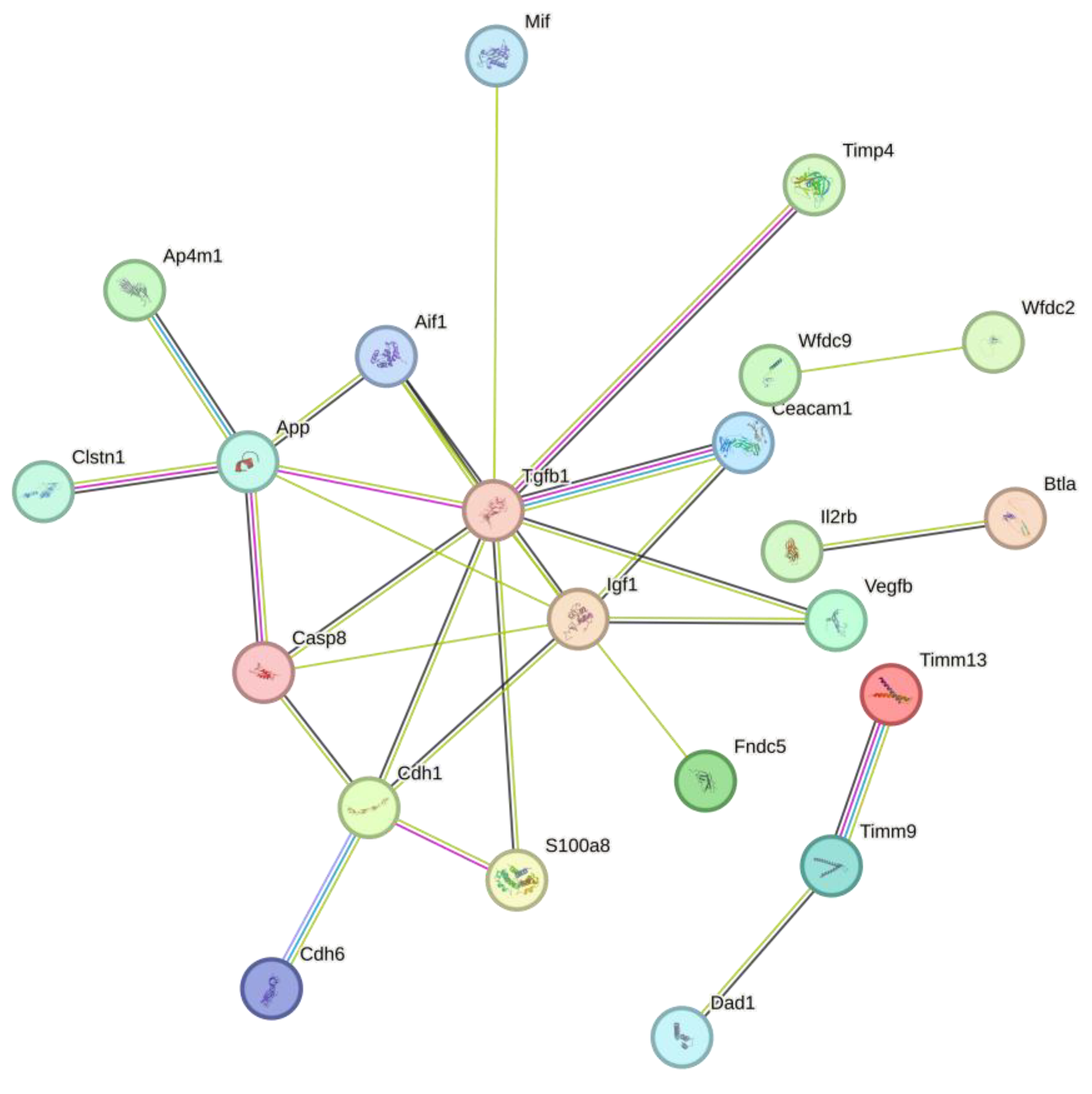

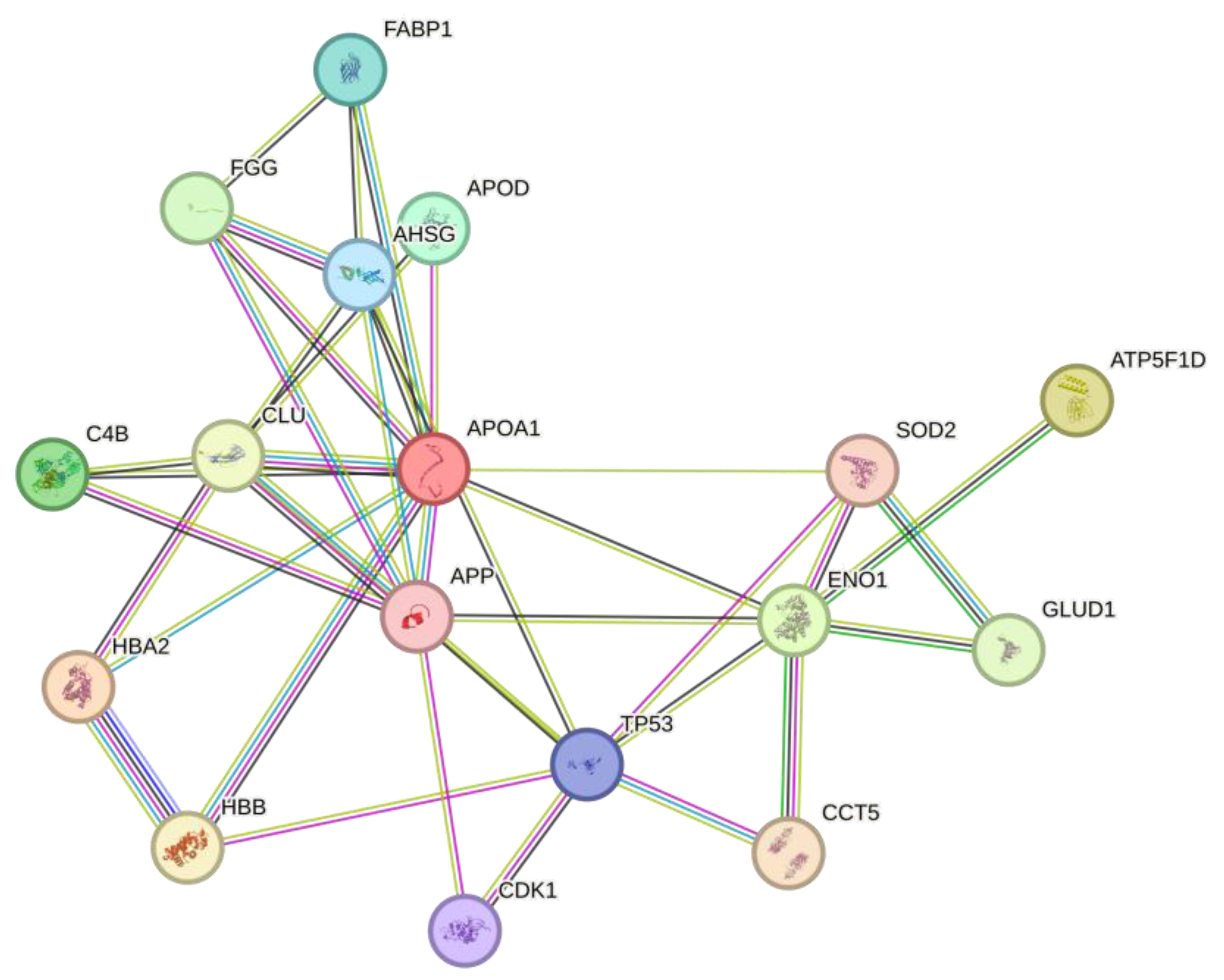

2.5. In Silico Protein Interaction

Protein interaction analysis in string of all proteins that were downregulated from Sim, MPP+, and MPP+/Sim groups with respect to control, exhibited 47 nodes, 28 edges, an average node degree of 1.19, an average local clustering coefficient of 0.385, and a PPI enrichment p-value of 4.23e-07 (

Figure 3).

Interestingly molecular function of most of these proteins is involved in the regulation of the ATP metabolic process. While expression of increased proteins is mainly involved in response to oxidative stress (

Figure 4). Protein interaction analysis in string exhibited 17 nodes, 38 edges, an average node degree of 4.47, an average local clustering coefficient of 0.681, and a PPI enrichment p-value of 1.73e-07.

3. Discussion

In the present study, we report the neuroprotective effect of Sim against MPP+-induced damage, through specific changes in protein expression, identified by the proteomic profile analysis of the ventral midbrain. There is substantial accumulated evidence consistent with works from our group indicating the effect of statins in neuroprotection [

14,

15], which consistently indicates the possible therapeutic potential of Sim for the treatment of neurodegenerative diseases such as PD.

Among the main findings of the present study, the differential regulation of proteins involved in the antioxidant response was evidenced. It can be observed that the group treated with Sim presents an increase in the expression of Cu and Zn-dependent superoxide dismutase (SOD2) and glutathione S-transferase (GSTP1), showing an increase in the antioxidant response. This response may be decisive because oxidative stress is one of the main markers of dopaminergic neuronal damage in the present model of PD [

19,

20]; however, we cannot assert that this is a marker of early damage in the neurodegeneration process, although the inhibition of the formation of ROS protects dopaminergic neurons from lipid peroxidation, protein nitration, and mitochondrial DNA damage [

20,

21,

22]. In the same way, Sim inhibited the apoptosis of PC12 cells induced by MPP+ via inhibiting ROS production (Xu et al., 2013) and regulates the endogenous antioxidant system through ERK [

23]. Likewise, the increase in proteins related to ATP synthesis, such as the ATP synthase delta subunit, shows that Sim counteracts the decrease in mitochondrial electron transport chain functioning, as shown in the present study and patients with PD. This coincides with recent studies that highlight the beneficial effect of statins in mitochondrial homeostasis [

24].

On the other hand, our findings demonstrate an upregulation in cytokines related to inflammatory processes, such as macrophage migration inhibitory factor (MIF) and transforming growth factor-β1 (TGF-β1) in MPP+-treated rats. MIF, participate in both innate and adaptive immune responses [

25]; TGF-β1, is a multifunctional cytokine that plays a pivotal role in synaptic formation, plasticity, and neurovascular unit regulation, among others [

26], which suggests that Sim may be decreasing microglia activation through reducing the synthesis of proinflammatory proteins and the production of isoprenoids [

17], as well as by promoting dopaminergic neurotransmission, respectively. Similarly, in this study, a decrease in the expression of cell adhesion proteins was observed in the group administered with MPP+ and Sim, such as cadherin-1 and the cell adhesion protein neurocan. Although it is unlikely that increased expression of these types of proteins may be a primary cause for neuronal loss, its downregulation has been suggested as a compensatory mechanism to prevent the formation of aberrant synaptic connections during proinflammatory events in PD patients [

7].

The increase in the expression of proteins related to angiogenesis, such as the amyloid-beta precursor protein [

27], suggests that Sim promotes neuronal regeneration and synaptic stability after MPP+ lesion. This effect is consistent with our findings and could be mediated by a reduction in oxidative damage and neuroinflammation, preserving neuronal plasticity processes, among others [

27]. Interactome analysis showed that most proteins associated with inflammation decrease, while there is an increased expression of antioxidant enzymes, thus evidencing the neuroprotective effect of Sim in the nigrostriatal pathway of MPP+ injured rats [

14].

In terms of the above, the therapeutic potential of Sim in PD patients is promising, since this stanine counteracts oxidative stress, energy metabolism dysfunction, and reduces inflammatory damage. However, to transfer these findings to the clinical setting, it is essential to carry out additional studies to confirm its efficacy in humans in early stages of the disease, where a new pharmacological alternative could have a greater impact [

28] (Feng et al., 2020) by reducing neurodegenerative processes and increasing the lifespan of remaining dopaminergic neurons.

This study provides evidence of the effect of Sim in the VMB of rats; however, there are certain limitations. The PD model induced by intrastriatal microinjection of MPP+ is not able to reproduce all the markers of dopaminergic neuronal damage observed in PD patients, and it is not known whether the protective mechanism of Sim is influencing early markers of neuronal damage. Furthermore, it is important to perform a thorough analysis of the Sim effects time course and to evaluate its potential as an adjuvant together with other therapeutic strategies. It is possible that in future research, the proteome and metabolome correlation analysis may offer a comprehensive view of Sim effects on different preclinical models of PD, and its potential as an alternative treatment for patients with this disorder.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethics Statement

The protocol used in this study was approved by The Committee on Ethics and Use in Animal Experimentation of the Biomedical Research Institute and the standards of the National Institutes of Health of Mexico (Permit number IIB-UNAM-2017-2023). The study was done following the guidelines of Mexican regulations (NOM-062-ZOO-1999) and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institute of Health, 8th Edition, to ensure compliance with the established international regulations and guidelines.

4.2. Animals and Treatments

Adult male Wistar rats weighing 250-280 g were housed in a 12 h light-dark cycle room with constant temperature (23 °C); they had access to food and water ad libitum. To observe the effect of Sim, the rats were randomly assigned to four experimental groups (n≈8 per group): control, Sim treatment, MPP

+ injury, and experimental group (treated with Sim and MPP

+ injured). Experimental rats were submitted to a sub-chronic administration schedule of a single oral dose of Sim (40 mg/kg/day) diluted in Tween 80 1% of (Kendrick Pharmaceutical, Reg. No. 470M2002 SSA-IV). In Supplementary

Figure 1, it is a scheme of the whole protocol used in this study.

4.3. MPP + Intraestriatal Lesion.

MPP

+ was administered on the seventh Sim-treatment day, two hours after the last administration. Rats were anesthetized with Ketamine/Xylazine (70/10 mg/kg) and fixed to a stereotaxic apparatus (MARCA Y MODELO). Animals were infused with MPP

+ (10 μg / 8 μl) or saline solution (8 μl) according to the group they belonged to, into the right striatum (coordinates: 0.5 mm posterior, 3.0 mm lateral, and −4.5 mm ventral to bregma), according to Paxinos and Watson [

29]. In Supplementary

Figure 1, it is a timeline scheme of the whole protocol used in this study.

4.4. Circling Behavior

Apomorphine-induced circling behavior was assessed in rats as previously described (Rubio-Osornio et al., 2013) and considered the endpoint of brain toxicity. Six days after intrastriatal MPP+ injection, animals were subcutaneously treated with apomorphine and ascorbic acid (1 mg/kg and 1 mg/kg, respectively), then placed in individual cages. Five minutes later, the number of ipsilateral rotations to the lesioned striatum was recorded for 60 min. Rotations were considered as 360 turns, and the results were expressed as the total number of ipsilateral turns in a 1 h period (turns/h).

4.5. Striatal Dopamine Levels Measurement

Twenty-four hours after the Sim administration schedule and MPP+ infusion, HPLC with electrochemical detection was used to measure striatal levels of dopamine (DA), as described previously [

22]. Samples obtained 24 h after MPP+ injection were sonicated into 10 volumes of perchloric acid-sodium metabisulfite solution (1 M 0.1% w/v) and centrifuged at 10,000g for 10 min before the supernatant was analyzed. Data were collected and processed via interpolation in a standard curve. Results are expressed as nmol of DA per gram of wet tissue.

4.6. Fluorescent Lipidic Products Assay

Fluorescent lipidic products are formed during the uncontrolled oxidation of polyunsaturated membrane lipids. They are composed of Schiff bases formed by the cross-linking of aldehydes from the oxidized lipids with surrounding amino acids [

21]. Therefore, the increase in fluorescence signals in the extracted lipids is considered an estimation of oxidative damage. The effect of Simvastatin on the formation of striatal lipid fluorescent products (LPF) was evaluated 24 h after administration of MPP+, as described previously [

30]. The striatal tissue was homogenized in 2.2 ml of sterile saline, and 1 ml of the homogenate was then added to 4 mL of a chloroform-methanol mixture (2:1, v/v). The tubes were capped and vortexed for 10 s, and the mixture was then ice-cooled for 30 min to allow phase separation. The aqueous phase was discarded, 1 mL of the chloroform layer was transferred into a quartz cuvette, and 150 ml of methanol was added. Fluorescence was measured in a PerkinElmer LS50B luminescence spectrometer at 370 nm of excitation and 430 nm of emission. The protein content was measured according to the method of Lowry et al. [

31]. Results are expressed as arbitrary fluorescence units/mg protein.

4.7. Immunofluorescence for Tyrosine Hydroxylase in the Striatum of the Rat

The effect of Sim on neurodegeneration induced-MPP+ in the rat striatum was measured by the presence of tyrosine hydroxylase (TH)—antibody dilution (1:100). Approximately 24 h after the behavioral evaluation, the animals (n = 3–4) were anesthetized with an overdose of sodium pentobarbital (80 mg/kg) and intracardially perfused with 200 μL of saline solution. The perfusion was followed by 200 mL of paraformaldehyde at 4%. The brains were removed, stored in 30% sucrose solution, and kept refrigerated until processing. Subsequently, 22 μm coronal cuts were made from the injured area (AP +1.6 mm to -0.48 mm related to Bregma) using a Leica brand cryostat, model CM 1520. The cuts were made in the injured area to carry out an optical percentage evaluation for the positive signal to TH. Tissues were washed with PBS 3% (10 min), and antigen recovery was performed in citrate solution for 1 h. Three more washes were performed with PBS, and blocking was carried out with BSA (6 mg), and horse serum (4 ml) dissolved in 200 ml of PBS 3% for 1 h. Subsequently, the samples were incubated overnight with a mouse anti-TH antibody (1:100; sc-25269, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Paso Robles, CA, USA.). Subsequently, three more washes were carried out with PBS-tween 3% and the samples were immediately incubated for 2 h with a secondary antibody (AffiniPure Goat Anti-Mouse IgG 1:100 Fluorescein (FITC)- AB_2338589 Jackson ImmunoResearch, West Baltimore Pike, PA, USA). Finally, the tissues were mounted on previously silanized slides with 3 ml of antioxidant solution. Nine slices of each brain were taken, in accordance with the coordinates already mentioned, from which photographs of six fields of the striatum of the injured hemisphere were taken for the determination of the TH signal. The photographs were processed as binary figures using Image J software to evaluate the percentage areas of both signals in each slide. Results were reported as the average area percent signal for TH.

4.8. Protein Extraction of Samples

Ventral midbrain (VMB) samples were washed with 1 mL of PBS, three times, then were homogenized for 1 min in ice bath and the proteins were precipitated with acetone for 48 h; samples were centrifuged 6000 rpm/ 5 min/ 4° (3X); pellets were solubilized with 500 mL of 2D sample buffer (4% urea, 2% thiourea, 2% CHAPS, 160 mM DTT); then were precipitated with methanol-chloroform; pellets were solubilized with 200 mL of 2D sample buffer, were centrifuged at maximum speed in microfuge 5 min, 4° and supernatants were used for two dimensional analysis

4.9. Two-Dimensional Analysis

300 μg of VMB of all groups was individually loaded in IPG-strips pH 3-10 of 7 cm. After 16 h of passive rehydration, IEF was performed as described below: step 1, 50 V/20 min /rapid; step 2, 70 V/30 min/rapid; step 3, 250 V/20 min/linear; step 4, 4000 V/2 h/lineal; step 5, 4000 V/20000 Vh/rapid. Strips were treated with equilibration buffer with 2% (w/v) DTT (6 M urea, 2 % SDS, 0.375 M TRIS-HCl pH 8.8, 20% glycerol, and 1 % bromophenol blue) for 15 min, and then with equilibration buffer with 2.5% (w/v) IAA for 20 min. Strips were loaded in precast 4-20% polyacrylamide gels, and electrophoresis was run for approximately 35 minutes at 200 V. Gels were stained with Coomassie blue.

4.10. Bioinformatic Analysis

A pull from three independent experiments was performed with different treatments. A master gel of each experimental condition was generated in order to identify the differential protein spots among them. Once the spots were identified, they were compared both by IP and by molecular weight with the PDQuest software. Then, the deduction of the possible identity of each protein was carried out using the Expert Protein Analysis System (ExPASy) bioinformatics platform (

https://web.expasy.org/tagident/) [

32] , considering a range of ±0.1 value of each IP. Likewise, the deduction of the probable protein function was identified by the UniProtKB platform (

https://www.uniprot.org/statistics/Swiss-Prot).

4.11. Protein-Protein Network Analysis

4.12. Statistical Analysis

Results from lipid fluorescent products, dopamine content, and TH levels were analyzed by one-way ANOVA followed by the Tukey test. Data obtained from evaluating the circling behavior were analyzed using the Kruskal–Wallis test followed by the Mann–Whitney test. In all results, statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

Sim showed a significant antioxidant and, more importantly, neuroprotective effect against MPP+-induced neurotoxicity, since it was able to counteract the oxidative damage exerted by this neurotoxin, lessen three damage markers: lipid peroxidation, dopamine content decrease, and circling behavior. The first two were evaluated as short-term, and the last one was considered a long-term endpoint damage marker. We also identified proteins responsible for the inflammation response, which should be further studied.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, J.M.-M., G.R. and M.R.-O.; methodology, C.T.G.-D.L., S.M., C.Ru, Y.A.V., K.E.N.C., M.S.M. .; software, C.T.G.-D.L.; M.S.M., K.E.N.C. validation, J.M.-M., M.R.-O. and GR.; formal analysis, J.M.-M., M.R.-O. and C.T.G.-D.L.; investigation, M.R.-O., J.M.-M., C.T.G.-, and C.R.; resources, J.M.-M. and M.R.-O.; data curation, M.R.-O. and C.T.G.-D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.R.-O. GR and J.M.M.;writing—review and editing, M.R.-O. and J.M.-M.; supervision, M.R.-O., C.T.G.-D.L. and J.M.-M.; project administration, J.M.-M., M.R.-O. and C.T.G.-D.L.; funding acquisition, J.M.-M. and M.R.-O. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This project has been supported partially by both Grant SEP/CONACYT 287959 and 257092 to MRO. Additionally, by Grant IN-202723 from Programa de Apoyo a Proyectos de Innovación Tecnológica (PAPIIT), Dirección General de Asuntos del Personal Académico (DGAPA), Universidad Nacional Autónoma de México (UNAM) to JMM.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The animal study protocol was approved by The Committee on Ethics and Use in Animal Experimentation of the Institute of Neurology and Neurosurgery and the standards of the National Institutes of Health of Mexico (Permit number INN-2017-2023). The study was performed following Mexican regulations (NOM-062-ZOO-1999) and the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals of the National Institute of Health, 8th Edition to ensure compliance with the established international regulations and guidelines.

Data Availability Statement

The raw data supporting the conclusions of this manuscript will be made available by the authors, without undue reservation, to any qualified researcher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Biologist Gilberto Hevyn Chávez Cortés and PhD Daniela Silva-Adaya for the technical support they provided to aid in the realization of the present study. Claudia A. Garay-Canales provided help with formatting and proofreading.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

References

- Poewe, W.; Seppi, K.; Tanner, C.M.; Halliday, G.M.; Brundin, P.; Volkmann, J.; Schrag, A.-E.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson Disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers 2017, 3, 17013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blandini, F.; Nappi, G.; Tassorelli, C.; Martignoni, E. Functional Changes of the Basal Ganglia Circuitry in Parkinson’s Disease. Progress in Neurobiology 2000, 62, 63–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeMaagd, G.; Philip, A. Parkinson’s Disease and Its Management: Part 1: Disease Entity, Risk Factors, Pathophysiology, Clinical Presentation, and Diagnosis. P T 2015, 40, 504–532. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Szatmari, S.; Min-Woo Illigens, B.; Siepmann, T.; Pinter, A.; Takats, A.; Bereczki, D. Neuropsychiatric Symptoms in Untreated Parkinson’s Disease. NDT 2017, Volume 13, 815–826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ozansoy, M.; Başak, A.N. The Central Theme of Parkinson’s Disease: α-Synuclein. Mol Neurobiol 2013, 47, 460–465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chinta, S.J.; Andersen, J.K. Redox Imbalance in Parkinson’s Disease. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta (BBA) - General Subjects 2008, 1780, 1362–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hirsch, E.C.; Vyas, S.; Hunot, S. Neuroinflammation in Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinsonism & Related Disorders 2012, 18, S210–S212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blum, D.; Torch, S.; Lambeng, N.; Nissou, M.-F.; Benabid, A.-L.; Sadoul, R.; Verna, J.-M. Molecular Pathways Involved in the Neurotoxicity of 6-OHDA, Dopamine and MPTP: Contribution to the Apoptotic Theory in Parkinson’s Disease. Progress in Neurobiology 2001, 65, 135–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Z.; Qiu, A.-W.; Huang, Y.; Yang, Y.; Chen, J.-N.; Gu, T.-T.; Cao, B.-B.; Qiu, Y.-H.; Peng, Y.-P. IL-17A Exacerbates Neuroinflammation and Neurodegeneration by Activating Microglia in Rodent Models of Parkinson’s Disease. Brain, Behavior, and Immunity 2019, 81, 630–645. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.F. A Hypothesis of Monoamine (5-HT) - Glutamate/GABA Long Neural Circuit: Aiming for Fast-Onset Antidepressant Discovery. Pharmacol Ther 2020, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, S.; Li, L.; Sun, X.; Hua, J.; Zhang, K.; Hao, L.; Liu, L.; Shi, D.; Zhou, H. FTY720 Inhibits MPP+-Induced Microglial Activation by Affecting NLRP3 Inflammasome Activation. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol 2019, 14, 478–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gratl, V.; Cheung, R.C.; Chen, B.; Taghibiglou, C.; Van Iderstine, S.C.; Adeli, K. Simvastatin, an HMG-CoA Reductase Inhibitor, Induces the Synthesis and Secretion of Apolipoprotein AI in HepG2 Cells and Primary Hamster Hepatocytes. Atherosclerosis 2002, 163, 59–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Michos, E.D.; Sibley, C.T.; Baer, J.T.; Blaha, M.J.; Blumenthal, R.S. Niacin and Statin Combination Therapy for Atherosclerosis Regression and Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease Events. Journal of the American College of Cardiology 2012, 59, 2058–2064. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Osornio, M.; León, C.T.G.-D.; Montes, S.; Rubio, C.; Ríos, C.; Monroy, A.; Morales-Montor, J. Repurposing Simvastatin in Parkinson’s Disease Model: Protection Is throughout Modulation of the Neuro-Inflammatory Response in the Substantia Nigra. IJMS 2023, 24, 10414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aguirre-Vidal, Y.; Montes, S.; Tristan-López, L.; Anaya-Ramos, L.; Teiber, J.; Ríos, C.; Baron-Flores, V.; Monroy-Noyola, A. The Neuroprotective Effect of Lovastatin on MPP + -Induced Neurotoxicity Is Not Mediated by PON2. NeuroToxicology 2015, 48, 166–170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santiago, M.; Hernández-Romero, M.C.; Machado, A.; Cano, J. Zocor Forte® (Simvastatin) Has a Neuroprotective Effect against LPS Striatal Dopaminergic Terminals Injury, Whereas against MPP+ Does Not. European Journal of Pharmacology 2009, 609, 58–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wood, W.G.; Eckert, G.P.; Igbavboa, U.; Müller, W.E. Statins and Neuroprotection: A Prescription to Move the Field Forward. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences 2010, 1199, 69–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barkovich, A.J.; Millen, K.J.; Dobyns, W.B. A Developmental and Genetic Classification for Midbrain-Hindbrain Malformations. Brain 2009, 132, 3199–3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Zhao, X.; Li, Y.; Li, G.; Liu, X. Damage to Dopaminergic Neurons by Oxidative Stress in Parkinson’s Disease (Review). Int J Mol Med 2018. [CrossRef]

- Weng, M.; Xie, X.; Liu, C.; Lim, K.-L.; Zhang, C.; Li, L. The Sources of Reactive Oxygen Species and Its Possible Role in the Pathogenesis of Parkinson’s Disease. Parkinson’s Disease 2018, 2018, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rubio-Osornio, M.; Montes, S.; Heras-Romero, Y.; Guevara, J.; Rubio, C.; Aguilera, P.; Rivera-Mancia, S.; Floriano-Sánchez, E.; Monroy-Noyola, A.; Ríos, C. Induction of Ferroxidase Enzymatic Activity by Copper Reduces MPP+-Evoked Neurotoxicity in Rats. Neuroscience Research 2013, 75, 250–255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rubio-Osornio, M.; Montes, S.; Pérez-Severiano, F.; Aguilera, P.; Floriano-Sánchez, E.; Monroy-Noyola, A.; Rubio, C.; Ríos, C. Copper Reduces Striatal Protein Nitration and Tyrosine Hydroxylase Inactivation Induced by MPP+ in Rats. Neurochemistry International 2009, 54, 447–451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, J.; Qiao, L.; Wu, J.; Fan, H.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y. Simvastatin Protects Dopaminergic Neurons Against MPP+-Induced Oxidative Stress and Regulates the Endogenous Anti-Oxidant System Through ERK. Cell Physiol Biochem 2018, 51, 1957–1968. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mollazadeh, H.; Tavana, E.; Fanni, G.; Bo, S.; Banach, M.; Pirro, M.; Von Haehling, S.; Jamialahmadi, T.; Sahebkar, A. Effects of Statins on Mitochondrial Pathways. J cachexia sarcopenia muscle 2021, 12, 237–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zeng, L.; Hu, P.; Zhang, Y.; Li, M.; Zhao, Y.; Li, S.; Luo, A. Macrophage Migration Inhibitor Factor (MIF): Potential Role in Cognitive Impairment Disorders. Cytokine & Growth Factor Reviews 2024, 77, 67–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, C.; Miao, J.; Guo, J. The Relationship between TGF-Β1 and Cognitive Function in the Brain. Brain Research Bulletin 2023, 205, 110820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.-C.; Lei, S.-Y.; Zhang, D.-H.; He, Q.-Y.; Sun, Y.-Y.; Zhu, H.-J.; Qu, Y.; Zhou, S.-Y.; Yang, Y.; Li, C.; et al. The Pleiotropic Effects of Statins: A Comprehensive Exploration of Neurovascular Unit Modulation and Blood–Brain Barrier Protection. Mol Med 2024, 30, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, L.; Lai, Q.-M.; Zhou, G.-M.; Yang, L.; Shi, T.-Y.; Jiang, L.; Wang, H.-F. Simvastatin Relieves Myocardial Ischemia/Reperfusion Injury in Rats through Hedgehog Signaling Pathway. European Review for Medical and Pharmacological Sciences 2020, 24, 6400–6408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paxinos, G.; Watson, C. The Rat Brain; 1998; ISBN 9780123741219.

- Triggs, W.J.; Willmore, L.J. In Vivo Lipid Peroxidation in Rat Brain Following Intracortical Fe2+ Injection. Journal of Neurochemistry 1984, 42, 976–980. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, C.-H. Quantification and Analysis of Proteins. In Diagnostic Molecular Biology; Elsevier, 2019; pp. 187–214 ISBN 978-0-12-802823-0.

- Gasteiger, E. ExPASy: The Proteomics Server for in-Depth Protein Knowledge and Analysis. Nucleic Acids Research 2003, 31, 3784–3788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).