Submitted:

05 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Motivation

1.2. Background Concepts

1.3. Relation to VC Dimension

1.4. Relation to Other Relevant Concepts

2. Methodology

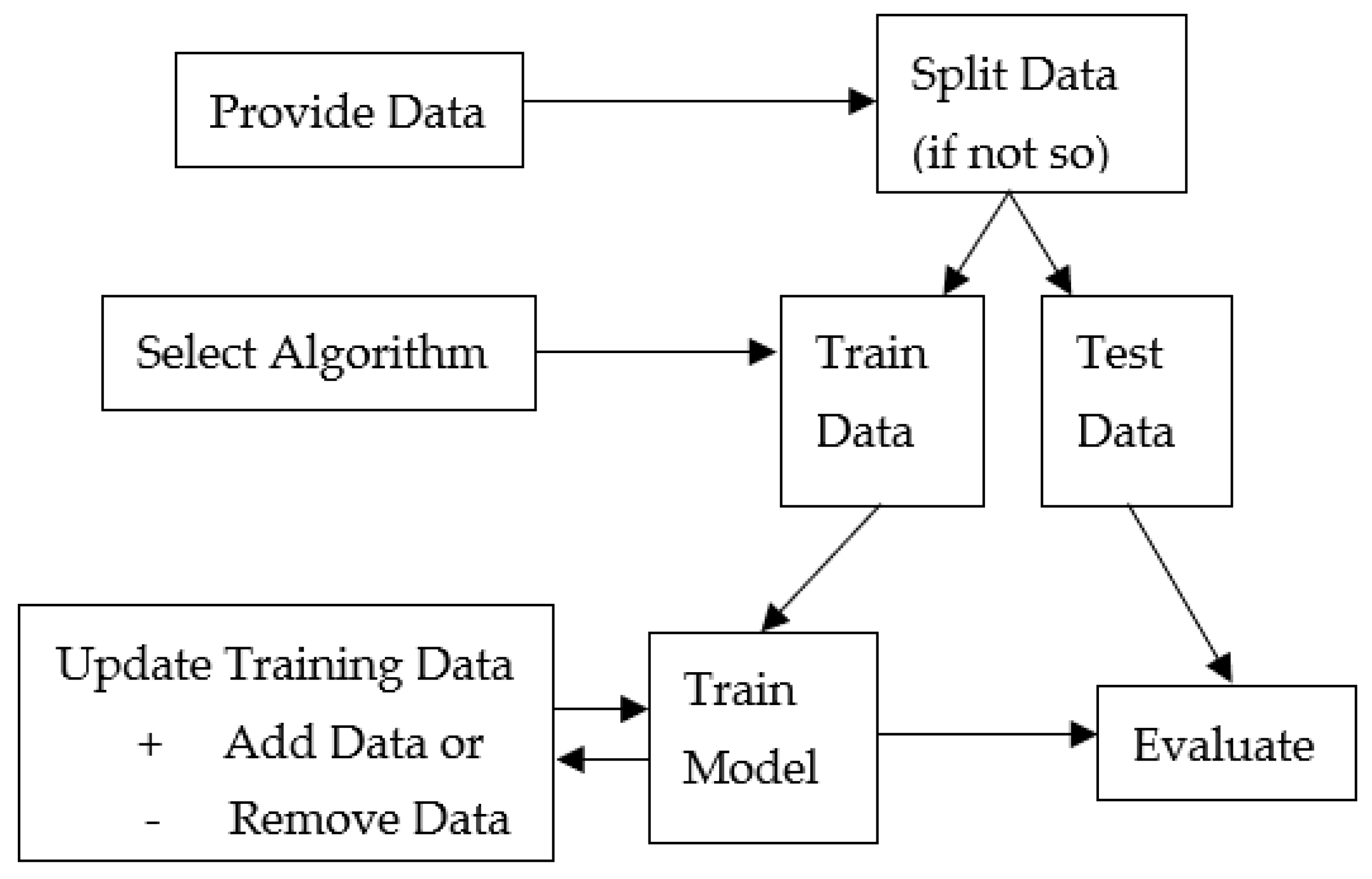

2.1. General Framework

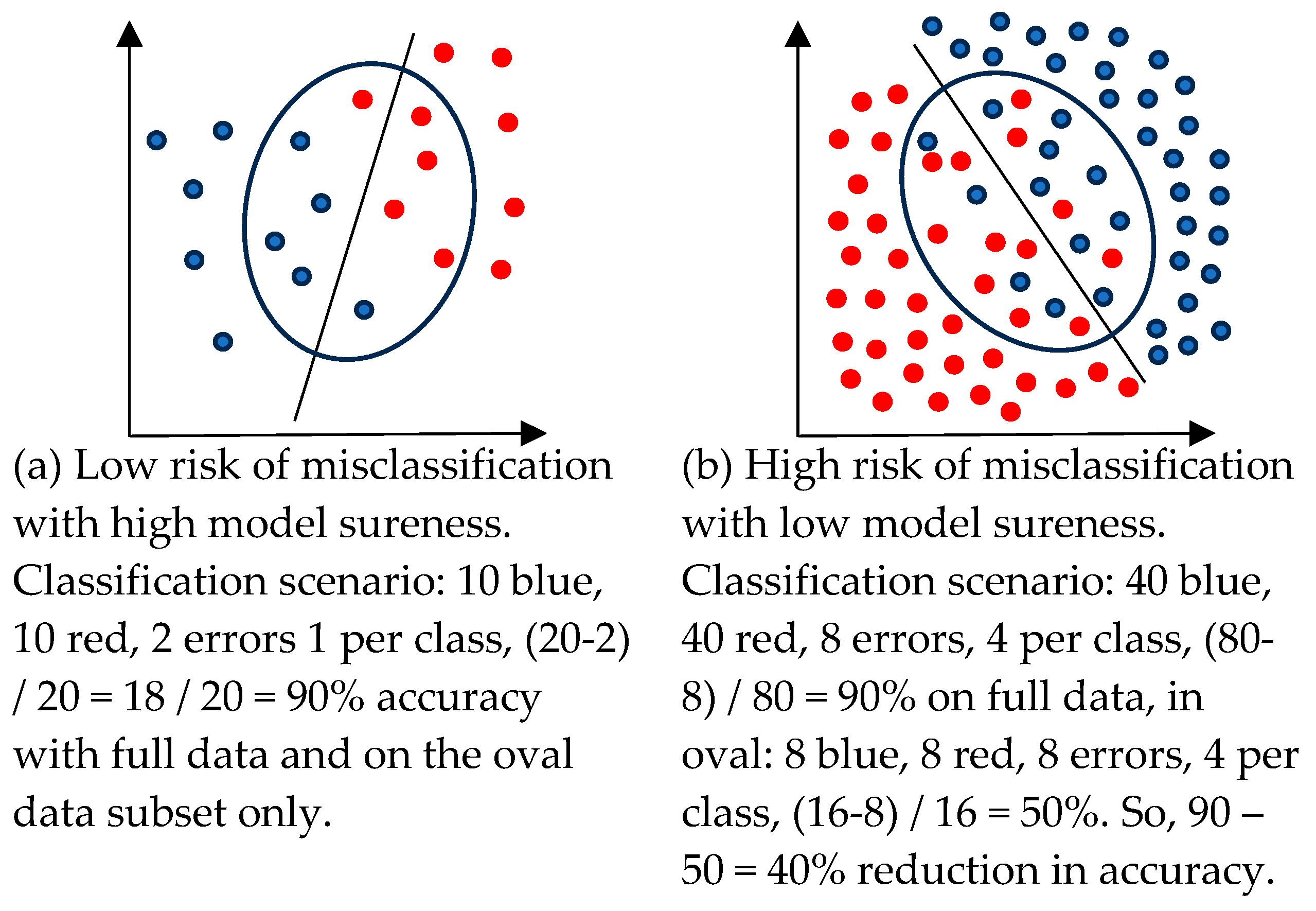

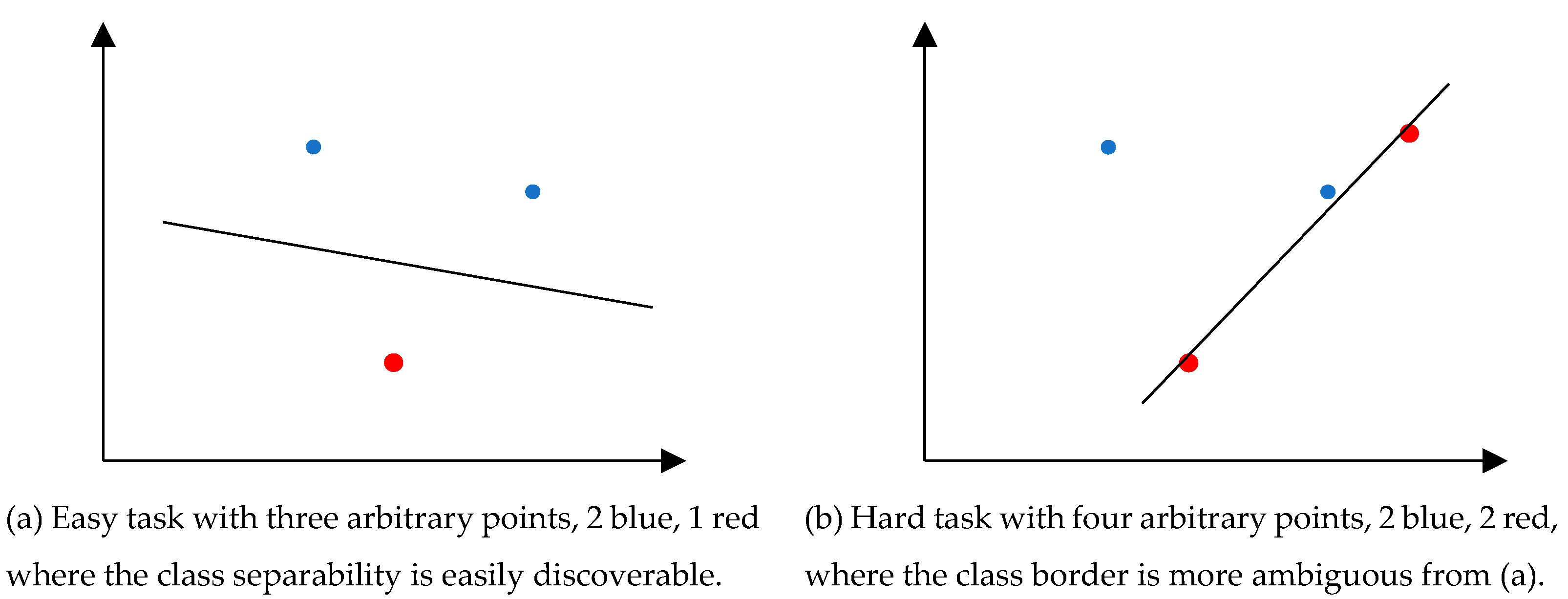

2.2. Definitions

2.3. Algorithms

-

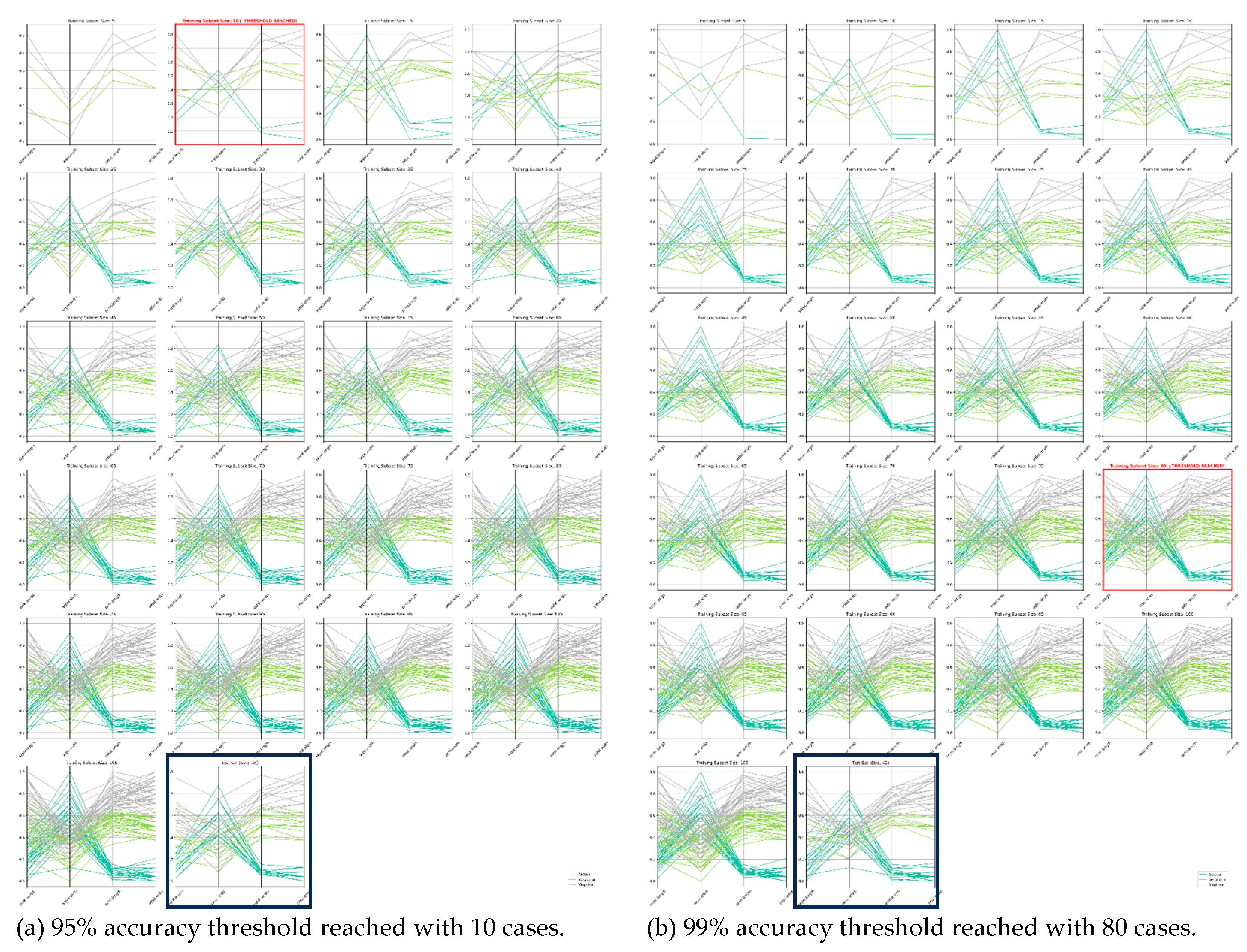

Minimal Dataset Search (MDS) Algorithm: It is characterized by as a triplet of:<BDIR, T, IMAX>Here BDIR is a computation direction indicator bit. BDIR = 0 if the Minimal Dataset Search algorithm starts from the full set of n-D points S and excludes some n-D points from S. Bit BDIR = 0 if the Minimal Dataset Search algorithm starts from some subset of set S and includes more n-D points from set S. The accuracy threshold T is some numerical percentage value 0 to 1, e.g., 0.95 for 95%. A predefined max number of iterations to produce subsets is denoted as IMAX. This algorithm: (1) reads the triple <BDIR, T, IMAX>, (2) updates and tests the selected training dataset using the respective IMDS, EMDS, and AHSG algorithms, described below.

- Inclusion Minimal Dataset Search (IMDS) Algorithm: It iteratively includes a fixed percentage of n-D points of the initial dataset S to the learnt subset Si, trains a selected ML classifier A thereon, and evaluates accuracy on all known separate test data Sev. It iterates until all data are added and assessed when reaching threshold T, e.g., 95% accuracy of model.

- Exclusion Minimal Dataset Search (EMDS) Algorithm: In contrast with the above Inclusion Minimal Dataset Search, this algorithm instead starts on the entire training dataset S and excludes data iteratively to retrain a selected ML algorithm on. It also assesses reaching the threshold T.

- Additive Hyperblock Grower (AHG) Algorithm: It iteratively adds data subsets to the training data, builds hyperblocks (hyperrectangles) thereon using the existing IMHyper algorithm [27], then tests class purity of each hyperblock iteration on the next data subset to be added.

3. Case Studies

3.1. Fisher Iris Data Cases Study

3.2. Wisconsin Breast Cancer Data Cases Study

| Characteristics | Number of iterations of SVM run | |

| 10 | 100 | |

| Mean Cases Needed | 20 | 21 ± 5.2 |

| Min Cases Needed | 20 | 20 |

| Max Cases Needed | 20 | 60 |

| Mean Model Accuracy | 0.975 ± 0.01 | 0.969 ± 0.011 |

| Convergence Rate | 10/10 = 100% | 99/100 = 99% |

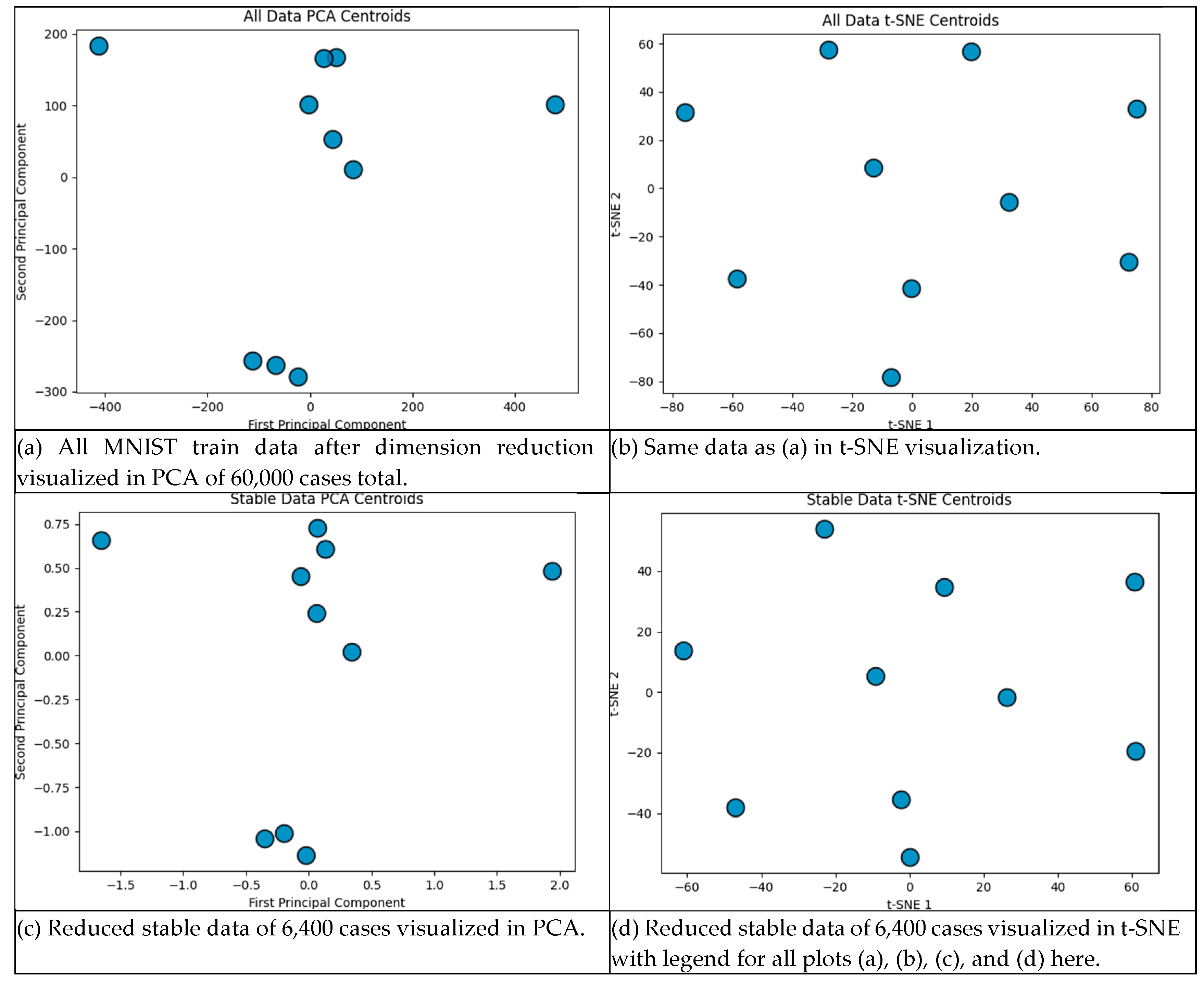

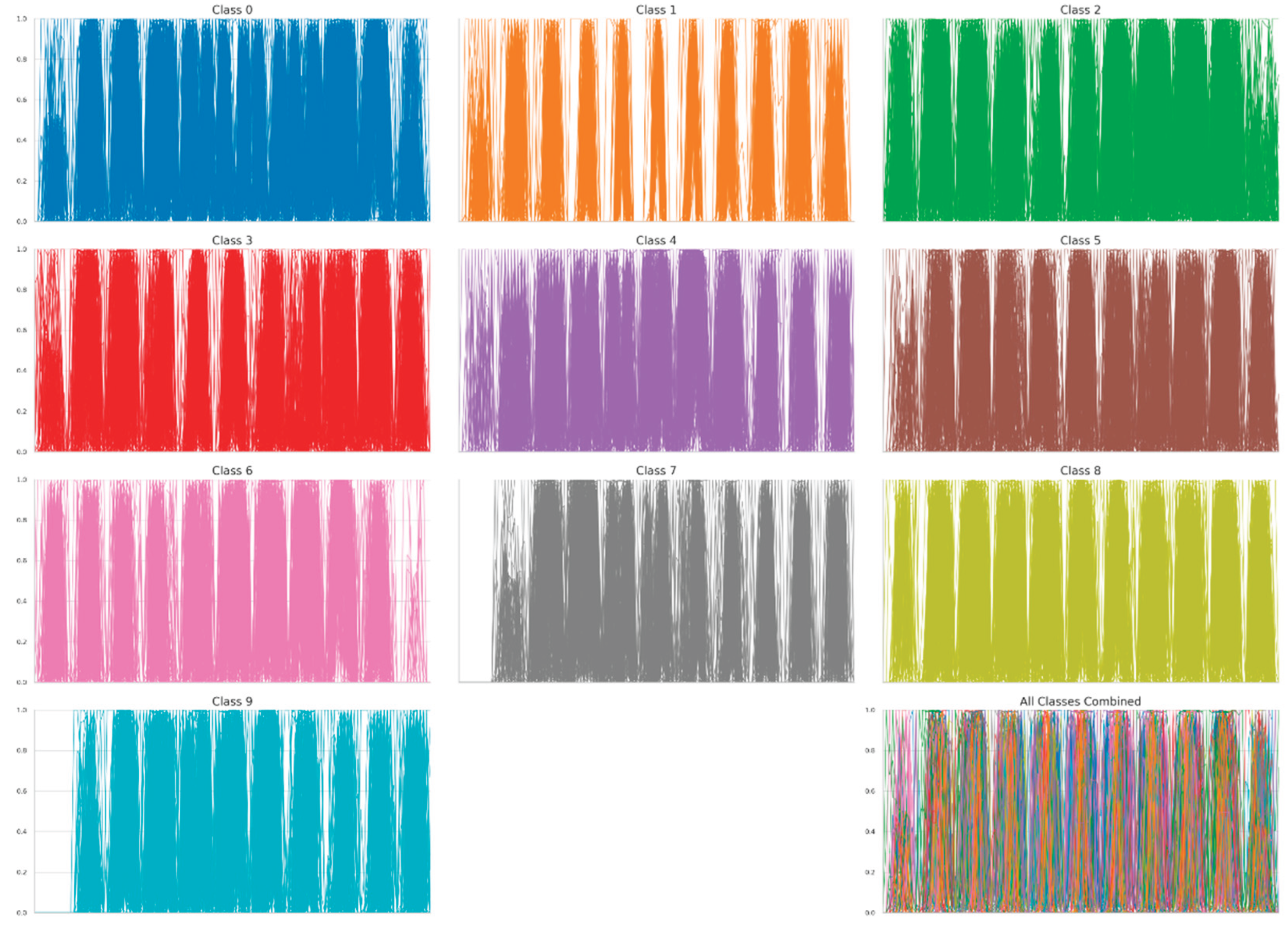

3.3. MNIST Digits

4. Conclusion

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

References

- Lin H., Han J., Wu P., Wang J., Tu J., Tang H., Zhu L., Machine learning and human-machine trust in healthcare: A systematic survey. CAAI Transactions on Intelligence Technology, 2024. 9(2):286-302. [CrossRef]

- Lipton Z., The mythos of model interpretability: machine learning, interpretability is both important and slippery, Association for Computing Machinery Queue, vol. 16, 2018. pp. 31–57. [CrossRef]

- Rong Y., Leemann T., Nguyen TT, Fiedler L., Qian P., Unhelkar V., Seidel T., Kasneci G., Kasneci E., Towards human-centered explainable ai: A survey of user studies for model explanations. IEEE transactions on pattern analysis and machine intelligence, 2023. 46(4):2104-22. [CrossRef]

- Yin M., Wortman Vaughan J., Wallach H., Understanding the effect of accuracy on trust in machine learning models. Proceedings of the CHI conference on human factors in computing systems, 2019. pp. 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Recaido C., Kovalerchuk B., Visual Explainable Machine Learning for High-Stakes Decision-Making with Worst Case Estimates. In: Data Analysis and Optimization. Springer, 2023. pp. 291-329.

- Williams A., Kovalerchuk B., Boosting of Classification Models with Human-in-the-Loop Computational Visual Knowledge Discovery. In: International Human Computer Interaction Conf, LNAI, vol. 15822, 2025.Springer, pp. 391-412.

- Kovalerchuk B., Visual knowledge discovery and machine learning. Springer, 2018.

- Kovalerchuk B., Nazemi K., Andonie R., Datia N., Bannissi E., editors, Artificial Intelligence and Visualization: Advancing Visual Knowledge Discovery. Springer, 2024.

- Williams A., Kovalerchuk B., High-Dimensional Data Classification in Concentric Coordinates, Internation Visualization, 2025.

- Settles B., From theories to queries: Active learning in practice. Active learning and experimental design workshop, 2011. pp. 1-18. http://proceedings.mlr.press/v16/settles11a/settles11a.pdf.

- Rubens N., Elahi M., Sugiyama M., Kaplan D., editors, Active Learning in Recommender Systems. Recommender Systems Handbook (2 ed.). Springer, 2016.

- Das S., Wong, W., Dietterich T., Fern A., Emmott A., editors, Incorporating Expert Feedback into Active Anomaly Discovery. 16th International Conference on Data Mining. IEEE, 2016. pp. 853–858.

- Whitney HM, Drukker K., Vieceli M., Van Dusen A., de Oliveira M., Abe H., Giger ML, Role of sureness in evaluating AI/CADx: Lesion-based repeatability of machine learning classification performance on breast MRI. Medical Physics, 2024. 51(3):1812-21. [CrossRef]

- Gupta MK, Rybotycki T., Gawron P., On the status of current quantum machine learning software. preprint arXiv:2503.08962, 2025.

- Woodward D., Hobbs M., Gilbertson JA, Cohen N., Uncertainty quantification for trusted machine learning in space system cyber security. IEEE 8th International Conference on Space Mission Challenges for Information Technology, 2021. pp. 38-43.

- Heskes T., Practical confidence and prediction intervals. Advances in neural information processing systems. 1996.

- Williams A., Kovalerchuk B., Synthetic Data Generation and Automated Multidimensional Data Labeling for AI/ML in General and Circular Coordinates, 28th International Conference Information Visualisation. IEEE, 2024. pp. 272-279.

- Nguyen PA, Tran T., Dao T., Dinh M., Doan MH, Nguyen V., Le N., editor, Efficient data annotation by leveraging AI for automated labeling solutions. Innovations and Challenges in Computing, Games, and Data Science. Hershey: IGI Global, 2025. pp. 101–116.

- Mohri, M., Rostamizadeh, A., & Talwalkar, A., Foundations of Machine Learning (2nd ed.). MIT Press, 2018.

- Vapnik, V., Statistical Learning Theory. Wiley, 1998.

- Vapnik V., Izmailov, R., Rethinking statistical learning theory: Learning using statistical invariants. Machine Learning, 2019. 108, pp. 381–423. [CrossRef]

- Wencour, R. S., Dudley, R. M., Some special Vapnik–Chervonenkis classes, Discrete Mathematics, 1981. 33 (3): pp. 313–318. [CrossRef]

- Vapnik V., Chervonenkis A., On the uniform convergence of relative frequencies of events to their probabilities. 2015.

- Blumer A., Ehrenfeucht A., Haussler D., Warmuth M. K., Learnability and the Vapnik–Chervonenkis dimension. Journal of the ACM, 1989. 36 (4): pp. 929–865. [CrossRef]

- Hayes D., Kovalerchuk B., Parallel Coordinates for Discovery of Interpretable Machine Learning Models. Artificial Intelligence and Visualization: Advancing Visual Knowledge Discovery. Springer, 2024. pp. 125-158.

- Hadamard J., Sur les problèmes aux dérivées partielles et leur signification physique. Princeton University Bulletin, 1902.

- Huber L., Kovalerchuk B., Recaido C., Visual knowledge discovery with general line coordinates. Artificial Intelligence and Visualization: Advancing Visual Knowledge Discovery. Springer, 2024. pp. 159-202.

- Neuhaus N., Kovalerchuk B., Interpretable Machine Learning with Boosting by Boolean Algorithm, 8th Intern. Conf. on Informatics, Electronics & Vision & 3rd Intern. Conf. on Imaging, Vision & Pattern Recognition, 2019. 307-311.

- Kovalerchuk B., Neuhaus N., Toward Efficient Automation of Interpretable Machine Learning. International Conference on Big Data, pp. 4933-4940, 978-1-5386-5035-6/18, IEEE, 2018.

- Artley B., MNIST: Keras Simple CNN (99.6%), 2022, https://medium.com/@BrendanArtley/mnist-keras-simple-cnn-99-6-731b624aee7f.

| Characteristics | Number of iterations of SVM run | ||

| 10 | 100 | 1,000 | |

| Mean Cases Needed | 37.8 ± 22 | 31.6 ± 16.5 | 31.8 ± 18.5 |

| Min Cases Needed | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Max Cases Needed | 90 | 90 | 100 |

| Mean Model Accuracy | 0.953 ± 0.035 | 0.959 ± 0.026 | 0.961 ± 0.026 |

| Convergence Rate* | 9 / 10 = 90% | 93 / 100 = 93% | 919 / 1000 = 91.9% |

| Characteristics | Number of iterations of LDA run | ||

| 10 | 100 | 1,000 | |

| Mean Cases Needed | 19 ± 5.4 | 21.3 ± 14.3 | 21.1 ± 14.5 |

| Min Cases Needed | 10 | 10 | 10 |

| Max Cases Needed | 30 | 100 | 100 |

| Mean Model Accuracy | 0.980 ± 0.018 | 0.977 ± 0.021 | 0.977 ± 0.02 |

| Convergence Rate | 10/10 = 100% | 99/100 = 99% | 981/1,000 = 98.1% |

| Iteration | Cases in Training data | Hyperblock Count |

Average Hyperblock Size |

Next Misclassified |

| 1 | 5 | 2 | 2.5 | N/A |

| 2 | 5 | 2 | 2.5 | 0/5 |

| 3 | 10 | 2 | 5 | 0/5 |

| 4 | 15 | 2 | 7.5 | 0/5 |

| 5 | 20 | 2 | 10 | 0/5 |

| 6 | 25 | 2 | 12.5 | 0/5 |

| 7 | 30 | 2 | 15 | 0/5 |

| 8 | 35 | 2 | 17.5 | 0/5 |

| 9 | 40 | 2 | 20 | 0/5 |

| 10 | 45 | 2 | 22.5 | 0/5 |

| 11 | 50 | 2 | 25 | 0/5 |

| 12 | 55 | 2 | 27.5 | 0/5 |

| 13 | 60 | 2 | 30 | 0/5 |

| 14 | 65 | 2 | 32.5 | 0/5 |

| 15 | 70 | 2 | 35 | 0/5 |

| 16 | 75 | 2 | 37.5 | 0/5 |

| 17 | 80 | 2 | 40 | 0/5 |

| 18 | 85 | 2 | 42.5 | 0/5 |

| 19 | 90 | 2 | 45 | 0/5 |

| 20 | 95 | 2 | 47.5 | 0/5 |

| 21 | 100 | 2 | 50 | 0/5 |

| Number of iterations of SVM run | ||

| Characteristics | 10 | 100 |

| Mean Cases Needed | 9,600 | 9,600 |

| Min Cases Needed | 9,600 | 9,600 |

| Max Cases Needed | 9,600 | 9,600 |

| Mean Model Accuracy | 0.972 | 0.972 |

| Convergence Rate | 10/10 = 10% | 100/100 = 100% |

| Cases Per Class Label | Case Count | Percentage |

| 0 | 954 | 9.94% |

| 1 | 1,088 | 11.33% |

| 2 | 946 | 9.85% |

| 3 | 985 | 10.26% |

| 4 | 953 | 9.93% |

| 5 | 834 | 8.69% |

| 6 | 976 | 10.17% |

| 7 | 1,029 | 10.72% |

| 8 | 899 | 9.36% |

| 9 | 936 | 9.75% |

| Training Data (all 60,000 training MNIST cases) | Accuracy on all Test Data (10,000 cases) |

| Data 28x28 ( full resolution) | 99.57% |

| Data 11x11 (121-D data by 3 pixels crop edges and average pooling of 2x2 kernel, 2 stride) | 99.34% |

| Accuracy on all test data | Sample Count |

| 95.36% | 2,800 |

| 96.25% | 3,200 |

| 95.20% | 2,500 |

| 95.93% | 2,700 |

| 96.79% | 2,800 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).