Submitted:

06 August 2025

Posted:

07 August 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations of Large Foundation Models in Medical Analysis

3. Applications of Large Foundation Models in Medical Domains

| Domain | Example LFM Models | Application Task | Performance |

|---|---|---|---|

| Radiology | CLIP, BioViL, GLoRIA, MedCLIP | Zero-shot or few-shot classification of pathologies in chest X-rays and CT scans [35] | Outperforms supervised baselines in low-label regimes; aligns image and report semantics effectively |

| Clinical NLP | BioBERT, ClinicalBERT, PubMedGPT, GatorTron | Named entity recognition (NER), relation extraction, clinical note summarization | Achieves state-of-the-art results on multiple clinical NLP benchmarks such as i2b2 and MIMIC-III |

| Health Records | RETAIN, Med-PaLM, BEHRT, TransformerEHR | Disease progression modeling, risk prediction, medication recommendation | Improves AUC/ROC and calibration in longitudinal patient modeling; captures temporal dependencies |

| Pathology | PaLM-E, HEAL, Vision Transformers | Whole slide image (WSI) classification, cancer subtype prediction | Enables WSI analysis without patch-level supervision |

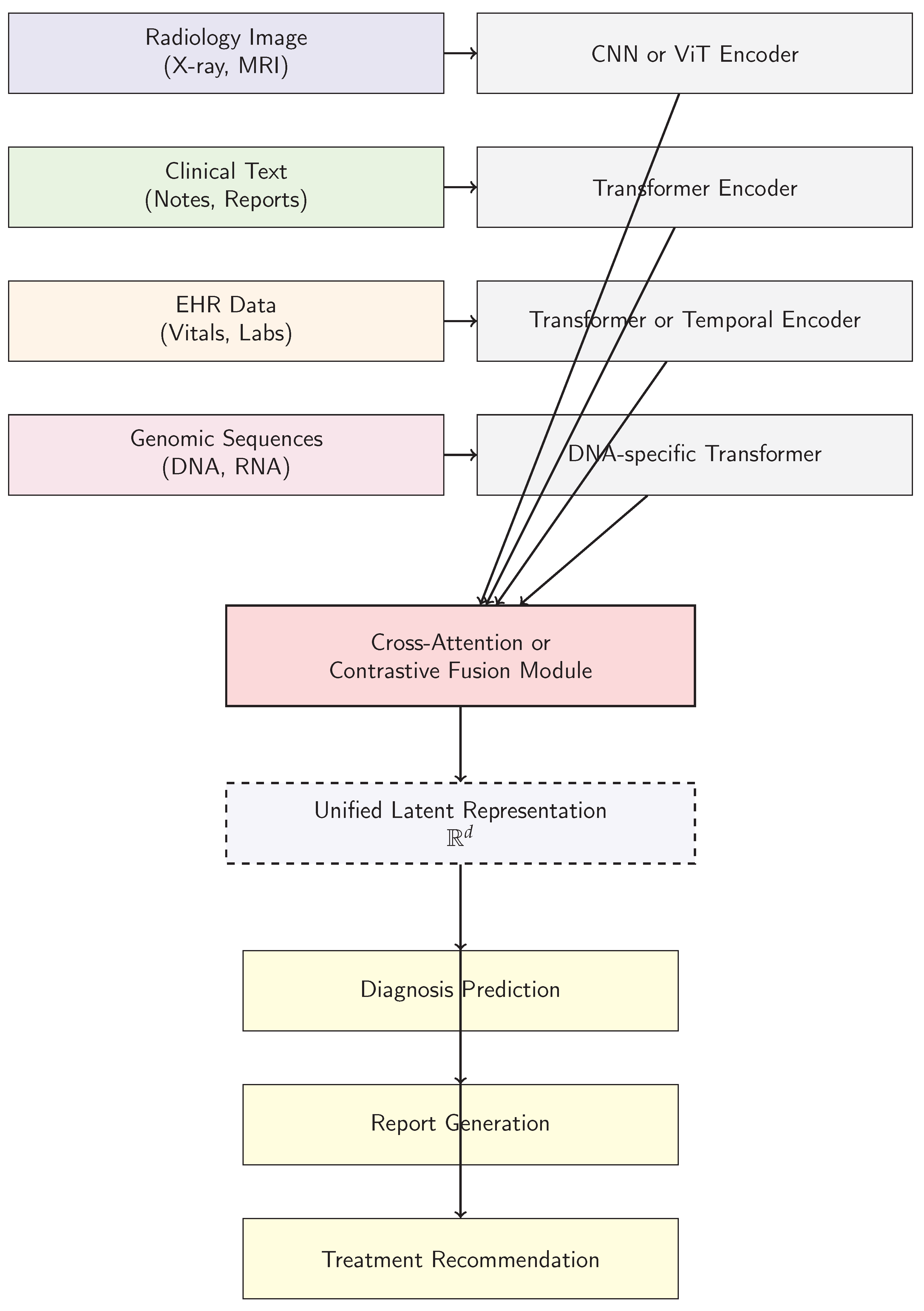

4. Architectural Paradigms of Large Foundation Models in Medical Analysis

5. Challenges and Ethical Considerations in Deploying Large Foundation Models in Medical Analysis

6. Future Directions and Research Opportunities in Large Foundation Models for Medical Analysis

7. Conclusion

References

- Touvron, H.; Lavril, T.; Izacard, G.; Martinet, X.; Lachaux, M.; Lacroix, T.; Rozière, B.; Goyal, N.; Hambro, E.; Azhar, F.; et al. LLaMA: Open and Efficient Foundation Language Models. CoRR 2023, abs/2302.13971, [2302.13971].

- Li, M.D.; Arun, N.T.; Gidwani, M.; Chang, K.; Deng, F.; Little, B.P.; Mendoza, D.P.; Lang, M.; Lee, S.I.; O’Shea, A.; et al. Automated assessment of COVID-19 pulmonary disease severity on chest radiographs using convolutional Siamese neural networks. medRxiv 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajaraman, S.; Antani, S.K. Modality-Specific Deep Learning Model Ensembles Toward Improving TB Detection in Chest Radiographs. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 27318–27326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Faghri, F.; Fleet, D.J.; Kiros, J.R.; Fidler, S. VSE++: Improving Visual-Semantic Embeddings with Hard Negatives. In Proceedings of the BMVC 2018, 2018, p. [Google Scholar]

- RSNA. RSNA Pneumonia Detection Challenge, 2018. Library Catalog: www.kaggle.com.

- Arbabshirani, M.R.; Dallal, A.H.; Agarwal, C.; Patel, A.; Moore, G. Accurate segmentation of lung fields on chest radiographs using deep convolutional networks. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2017: Image Processing. SPIE, 2017, p. 1013305. [CrossRef]

- Omkar Thawkar, Abdelrahman Shaker, S.S.M.H.C.R.M.A.S.K.J.L.; Khan, F.S. XrayGPT: Chest Radiographs Summarization using Large Medical Vision-language Models. arXiv: 2306.07971, arXiv:2306.07971 2023.

- Varela-Santos, S.; Melin, P. A new approach for classifying coronavirus COVID-19 based on its manifestation on chest X-rays using texture features and neural networks. Information Sciences 2021, 545, 403–414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dalla Serra, F.; Clackett, W.; MacKinnon, H.; Wang, C.; Deligianni, F.; Dalton, J.; O’Neil, A.Q. Multimodal Generation of Radiology Reports using Knowledge-Grounded Extraction of Entities and Relations. In Proceedings of the AACL 2022, Online only; 2022; pp. 615–624. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, Z.; Antani, S.; Long, R.; Thoma, G.R. Using deep learning for detecting gender in adult chest radiographs. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2018: Imaging Informatics for Healthcare, Research, and Applications. SPIE, 2018, p. 10. [CrossRef]

- Gilanie, G.; Bajwa, U.I.; Waraich, M.M.; Asghar, M.; Kousar, R.; Kashif, A.; Aslam, R.S.; Qasim, M.M.; Rafique, H. Coronavirus (COVID-19) detection from chest radiology images using convolutional neural networks. Biomed. Signal Process. Control 2021, 66, 102490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Miao, S.; Mansi, T.; Liao, R. Task Driven Generative Modeling for Unsupervised Domain Adaptation: Application to X-ray Image Segmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2018; Springer, 2018; Vol. 11071, pp. 599–607. [CrossRef]

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the CVPR; 2022; pp. 10684–10695. [Google Scholar]

- Ausawalaithong, W.; Marukatat, S.; Thirach, A.; Wilaiprasitporn, T. Automatic Lung Cancer Prediction from Chest X-ray Images Using Deep Learning Approach 2018. [arxiv:cs,eess/1808.10858].

- Crosby, J.; Chen, S.; Li, F.; MacMahon, H.; Giger, M. Network output visualization to uncover limitations of deep learning detection of pneumothorax. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2020: Image Perception, Observer Performance, and Technology Assessment. SPIE; 2020; p. 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Fu, H.; Zhao, Y.; Cheng, J.; Guo, M.; Gu, Z.; Yang, B.; Xiao, Y.; Gao, S.; Liu, J. SkrGAN: Sketching-Rendering Unconditional Generative Adversarial Networks for Medical Image Synthesis. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2019; Springer, 2019; Vol. 11767, pp. 777–785. [CrossRef]

- Isensee, F.; Jaeger, P.F.; Kohl, S.A.A.; Petersen, J.; Maier-Hein, K.H. nnU-Net: a self-configuring method for deep learning-based biomedical image segmentation. Nature Methods 2021, 18, 203–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Jia, C.; Wu, R.; Lv, B.; Li, B.; Li, F.; Du, G.; Sun, Z.; Li, X. Improving rib fracture detection accuracy and reading efficiency with deep learning-based detection software: a clinical evaluation. The British Journal of Radiology 2021, 94, 20200870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira, H.N.; Ferreira, E.; Santos, J.A.D. Truly Generalizable Radiograph Segmentation With Conditional Domain Adaptation. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 84037–84062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Rong, R.; Li, Q.; Yang, D.M.; Yao, B.; Luo, D.; Zhang, X.; Zhu, X.; Luo, J.; Liu, Y.; et al. A deep learning-based model for screening and staging pneumoconiosis. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 2201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, J.T.; Agu, N.; Lourentzou, I.; Sharma, A.; Paguio, J.A.; Yao, J.S.; Dee, E.C.; Mitchell, W.; Kashyap, S.; Giovannini, A.; et al. Chest ImaGenome Dataset for Clinical Reasoning. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS Datasets and Benchmarks 2021, 2021, 1–14. [Google Scholar]

- Oh, Y.; Park, S.; Ye, J.C. Deep Learning COVID-19 Features on CXR Using Limited Training Data Sets. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2020, 39, 2688–2700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramesh, A.; Dhariwal, P.; Nichol, A.; Chu, C.; Chen, M. Hierarchical Text-conditional Image Generation with CLIP Latents. arXiv preprint arXiv:2204.06125, arXiv:2204.06125 2022.

- Heusel, M.; Ramsauer, H.; Unterthiner, T.; Nessler, B.; Hochreiter, S. GANs Trained by a Two Time-Scale Update Rule Converge to a Local Nash Equilibrium. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 31st International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, 2017, NIPS’17, p. 6629–6640.

- Nicolson, A.; Dowling, J.; Koopman, B. Improving Chest X-ray Report Generation by Leveraging Warm Starting. Artificial Intelligence in Medicine 2023, 144, 102633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Liu, W.; Jia, Y.; Sermanet, P.; Reed, S.; Anguelov, D.; Erhan, D.; Vanhoucke, V.; Rabinovich, A. Going deeper with convolutions. In Proceedings of the IEEE conference on computer vision and pattern recognition; 2015; pp. 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Ouyang, X.; Karanam, S.; Wu, Z.; Chen, T.; Huo, J.; Zhou, X.S.; Wang, Q.; Cheng, J.Z. Learning Hierarchical Attention for Weakly-supervised Chest X-Ray Abnormality Localization and Diagnosis. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2020, 1–1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ezzat, D.; Hassanien, A.E.; Ella, H.A. An optimized deep learning architecture for the diagnosis of COVID-19 disease based on gravitational search optimization. Appl. Soft Comput. 2021, 98, 106742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Z.; Shen, Y.; Song, Y.; Wan, X. Cross-modal Memory Networks for Radiology Report Generation. In Proceedings of the ACL-IJCNLP 2021, Online; 2021; pp. 5904–5914. [Google Scholar]

- Philipsen, R.H.H.M.; Sánchez, C.I.; Melendez, J.; Lew, W.J.; van Ginneken, B. Automated chest X-ray reading for tuberculosis in the Philippines to improve case detection: a cohort study. The International Journal of Tuberculosis and Lung Disease: The Official Journal of the International Union Against Tuberculosis and Lung Disease 2019, 23, 805–810. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anis, S.; Lai, K.W.; Chuah, J.H.; Shoaib, M.A.; Mohafez, H.; Hadizadeh, M.; Ding, Y.; Ong, Z.C. An Overview of Deep Learning Approaches in Chest Radiograph. IEEE Access 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xing, Y.; Ge, Z.; Zeng, R.; Mahapatra, D.; Seah, J.; Law, M.; Drummond, T. Adversarial Pulmonary Pathology Translation for Pairwise Chest X-Ray Data Augmentation. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2019; Springer, 2019; Vol. 11769, pp. 757–765. [CrossRef]

- El Asnaoui, K. Design ensemble deep learning model for pneumonia disease classification. International Journal of Multimedia Information Retrieval 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Szegedy, C.; Ioffe, S.; Vanhoucke, V.; Alemi, A.A. Inception-v4, Inception-ResNet and the Impact of Residual Connections on Learning. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Thirty-First AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence. AAAI Press, 2017, AAAI’17, p. 4278–4284.

- Pham, V.T.; Tran, C.M.; Zheng, S.; Vu, T.M.; Nath, S. Chest x-ray abnormalities localization via ensemble of deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Advanced Technologies for Communications (ATC). IEEE, 2021, pp. 125–130.

- Matsubara, N.; Teramoto, A.; Saito, K.; Fujita, H. Bone suppression for chest X-ray image using a convolutional neural filter. Physical and Engineering Sciences in Medicine 2020, 43, 97–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, L.; Rao, A.; Agrawala, M. Adding Conditional Control to Text-to-Image Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the ICCV, October 2023; pp. 3836–3847. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, L.; Lin, Z.Q.; Wong, A. COVID-Net: a tailored deep convolutional neural network design for detection of COVID-19 cases from chest X-ray images. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 19549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bustos, A.; Pertusa, A.; Salinas, J.M.; de la Iglesia-Vayá, M. PadChest: A Large Chest X-Ray Image Dataset with Multi-Label Annotated Reports. Medical Image Analysis 2020, 66, 101797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jang, S.B.; Lee, S.H.; Lee, D.E.; Park, S.Y.; Kim, J.K.; Cho, J.W.; Cho, J.; Kim, K.B.; Park, B.; Park, J.; et al. Deep-learning algorithms for the interpretation of chest radiographs to aid in the triage of COVID-19 patients: A multicenter retrospective study. PLoS One 2020, 15, e0242759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Carlile, M.; Hurt, B.; Hsiao, A.; Hogarth, M.; Longhurst, C.A.; Dameff, C. Deployment of artificial intelligence for radiographic diagnosis of COVID-19 pneumonia in the emergency department. Journal of the American College of Emergency Physicians Open 2020, 1, 1459–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- You, D.; Liu, F.; Ge, S.; Xie, X.; Zhang, J.; Wu, X. AlignTransformer: Hierarchical Alignment of Visual Regions and Disease Tags for Medical Report Generation. In Proceedings of the MICCAI 2021, 2021, Vol. [Google Scholar]

- Haghighi, F.; Hosseinzadeh Taher, M.R.; Zhou, Z.; Gotway, M.B.; Liang, J. Learning Semantics-Enriched Representation via Self-discovery, Self-classification, and Self-restoration. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2020; Springer, 2020; Vol. 12261, pp. 137–147. [CrossRef]

- Li, Z.; Hou, Z.; Chen, C.; Hao, Z.; An, Y.; Liang, S.; Lu, B. Automatic Cardiothoracic Ratio Calculation With Deep Learning. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 37749–37756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kikkisetti, S.; Zhu, J.; Shen, B.; Li, H.; Duong, T.Q. Deep-learning convolutional neural networks with transfer learning accurately classify COVID-19 lung infection on portable chest radiographs. PeerJ 2020, 8, e10309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, J.Y.; Seo, H.; Kim, Y.G.; Lee, K.E.; Kim, S.; Kong, H.J. Codeless Deep Learning of COVID-19 Chest X-Ray Image Dataset with KNIME Analytics Platform. Healthcare Informatics Research 2021, 27, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conjeti, S.; Roy, A.G.; Katouzian, A.; Navab, N. Hashing with Residual Networks for Image Retrieval. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention—MICCAI 2017; Springer, 2017; Vol. 10435, pp. 541–549. [CrossRef]

- Thammarach, P.; Khaengthanyakan, S.; Vongsurakrai, S.; Phienphanich, P.; Pooprasert, P.; Yaemsuk, A.; Vanichvarodom, P.; Munpolsri, N.; Khwayotha, S.; Lertkowit, M.; et al. AI Chest 4 All. In Proceedings of the 2020 42nd Annual International Conference of the IEEE Engineering in Medicine Biology Society (EMBC); 2020; pp. 1229–0604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gooßen, A.; Deshpande, H.; Harder, T.; Schwab, E.; Baltruschat, I.; Mabotuwana, T.; Cross, N.; Saalbach, A. Deep Learning for Pneumothorax Detection and Localization in Chest Radiographs, 2019, [arXiv:eess.IV/1907.07324].

- Clevert, D.; Unterthiner, T.; Hochreiter, S. Fast and Accurate Deep Network Learning by Exponential Linear Units (ELUs) 2015. [1511.07289].

- Cornia, M.; Stefanini, M.; Baraldi, L.; Cucchiara, R. Meshed-memory Transformer for Image Captioning. In Proceedings of the CVPR; 2020; pp. 10578–10587. [Google Scholar]

- Rueckel, J.; Kunz, W.G.; Hoppe, B.F.; Patzig, M.; Notohamiprodjo, M.; Meinel, F.G.; Cyran, C.C.; Ingrisch, M.; Ricke, J.; Sabel, B.O. Artificial Intelligence Algorithm Detecting Lung Infection in Supine Chest Radiographs of Critically Ill Patients With a Diagnostic Accuracy Similar to Board-Certified Radiologists. Critical Care Medicine. [CrossRef]

- Bougias, H.; Georgiadou, E.; Malamateniou, C.; Stogiannos, N. Identifying cardiomegaly in chest X-rays: a cross-sectional study of evaluation and comparison between different transfer learning methods. Acta Radiol. 2020, 028418512097363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, C.; Yang, Y.; Liang, H.; Wu, B. Transfer learning for establishment of recognition of COVID-19 on CT imaging using small-sized training datasets. Knowledge-Based Systems 2021, 218, 106849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Walsh, S.L.F.; Humphries, S.M.; Wells, A.U.; Brown, K.K. Imaging research in fibrotic lung disease; applying deep learning to unsolved problems. The Lancet Respiratory Medicine 2020, 8, 1144–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Image-to-Image Translation with Conditional Adversarial Networks. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR). IEEE, jul 2017, pp. 1125–1134. [CrossRef]

- Cai, Q.; Du, S.Y.; Gao, S.; Huang, G.L.; Zhang, Z.; Li, S.; Wang, X.; Li, P.L.; Lv, P.; Hou, G.; et al. A model based on CT radiomic features for predicting RT-PCR becoming negative in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) patients. BMC Med. Imaging 2020, 20, 118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shiri, I.; Akhavanallaf, A.; Sanaat, A.; Salimi, Y.; Askari, D.; Mansouri, Z.; Shayesteh, S.P.; Hasanian, M.; Rezaei-Kalantari, K.; Salahshour, A.; et al. Ultra-low-dose chest CT imaging of COVID-19 patients using a deep residual neural network. Eur. Radiol. 2021, 31, 1420–1431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kipf, T.N.; Welling, M. Semi-Supervised Classification with Graph Convolutional Networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Learning Representations, 2017, pp. 1–14.

- Girshick, R. Fast R-CNN. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV). IEEE, dec 2015, pp. 1440–1448. https://doi.org/10.1109/iccv.2015.169. [CrossRef]

- Ranem, A.; Babendererde, N.; Fuchs, M.; Mukhopadhyay, A. Exploring SAM Ablations for Enhancing Medical Segmentation in Radiology and Pathology, 2023, [arXiv:cs.CV/2310.00504].

- Huang, Z.; Zhou, Q.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, X. Batch Similarity Based Triplet Loss Assembled into Light-Weighted Convolutional Neural Networks for Medical Image Classification. Sensors 2021, 21, 764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Yu, J.; Zhu, Q.; Li, S.; Zhao, Z.; Yang, B.; Pu, J. Potential of deep learning in assessing pneumoconiosis depicted on digital chest radiography. Occupational and Environmental Medicine 2020, 77, 597–602. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Klambauer, G.; Unterthiner, T.; Mayr, A.; Hochreiter, S. Self-Normalizing Neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems; 2017; pp. 972–981. [Google Scholar]

- Patel, B.N.; Langlotz, C.P. Beyond the AJR : “Deep Learning Using Chest Radiographs to Identify High-Risk Smokers for Lung Cancer Screening Computed Tomography: Development and Validation of a Prediction Model”. Am. J. Roentgenol. 2020, AJR.20.25334. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kim, M.; Lee, B.D. Automatic Lung Segmentation on Chest X-rays Using Self-Attention Deep Neural Network. Sensors 2021, 21, 369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lodwick, G.S.; Keats, T.E.; Dorst, J.P. The Coding of Roentgen Images for Computer Analysis as Applied to Lung Cancer. Radiology 1963, 81, 185–200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yi, X.; Adams, S.; Babyn, P.; Elnajmi, A. Automatic Catheter and Tube Detection in Pediatric X-ray Images Using a Scale-Recurrent Network and Synthetic Data. Journal of Digital Imaging 2019, 33, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- object-CXR - Automatic detection of foreign objects on chest X-rays.

- Oliveira, H.; Mota, V.; Machado, A.M.; dos Santos, J.A. From 3D to 2D: Transferring knowledge for rib segmentation in chest X-rays. Pattern Recognition Letters 2020, 140, 10–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Liu, R.; Wang, F.; Chang, X.; Liang, X. Auxiliary Signal-guided Knowledge Encoder-decoder for Medical Report Generation. World Wide Web 2022, pp. 1–18.

- Woźniak, M.; Połap, D.; Capizzi, G.; Sciuto, G.L.; Kośmider, L.; Frankiewicz, K. Small lung nodules detection based on local variance analysis and probabilistic neural network. Computer Methods and Programs in Biomedicine 2018, 161, 173–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fricks, R.B.; Abadi, E.; Ria, F.; Samei, E. Classification of COVID-19 in chest radiographs: assessing the impact of imaging parameters using clinical and simulated images. In Proceedings of the Medical Imaging 2021: Computer-Aided Diagnosis. International Society for Optics and Photonics, 2021, Vol. 11597, p. 115970A. [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Sun, L.L.; Jin, Q. Enhanced Diagnosis of Pneumothorax with an Improved Real-time Augmentation for Imbalanced Chest X-rays Data Based on DCNN. IEEE/ACM Transactions on Computational Biology and Bioinformatics 2019, pp. 1–1. [CrossRef]

- von Berg, J.; Young, S.; Carolus, H.; Wolz, R.; Saalbach, A.; Hidalgo, A.; Giménez, A.; Franquet, T. A novel bone suppression method that improves lung nodule detection. International Journal of Computer Assisted Radiology and Surgery 2015, 11, 641–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murphy, K.; Habib, S.S.; Zaidi, S.M.A.; Khowaja, S.; Khan, A.; Melendez, J.; Scholten, E.T.; Amad, F.; Schalekamp, S.; Verhagen, M.; et al. Computer aided detection of tuberculosis on chest radiographs: An evaluation of the CAD4TB v6 system. Scientific Reports 2020, 10, 5492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Blain, M.; T Kassin, M.; Varble, N.; Wang, X.; Xu, Z.; Xu, D.; Carrafiello, G.; Vespro, V.; Stellato, E.; Ierardi, A.M.; et al. Determination of disease severity in COVID-19 patients using deep learning in chest X-ray images. Diagnostic and Interventional Radiology (Ankara, Turkey) 2020. [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wu, X.; Ge, S.; Fan, W.; Zou, Y. Exploring and Distilling Posterior and Prior Knowledge for Radiology Report Generation. In Proceedings of the CVPR 2021, 2021, pp. 13753–13762.

- Wu, M.; Zhang, X.; Sun, X.; Zhou, Y.; Chen, C.; Gu, J.; Sun, X.; Ji, R. DIFNet: Boosting Visual Information Flow for Image Captioning. In Proceedings of the CVPR 2022, 2022, pp. 17999–18008.

- Williams, R.J. Simple Statistical Gradient-Following Algorithms for Connectionist Reinforcement Learning. Mach. Learn. 1992, 8, 229–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzunova, H.; Ehrhardt, J.; Jacob, F.; Frydrychowicz, A.; Handels, H. Multi-scale GANs for Memory-efficient Generation of High Resolution Medical Images. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2019; Springer, 2019; Vol. 11769, pp. 112–120. [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the NAACL 2019), Minneapolis, Minnesota, 2019; pp. 4171–4186.

- Ginneken, B.V.; Romeny, B.T.H.; Viergever, M. Computer-aided diagnosis in chest radiography: a survey. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2001, 20, 1228–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Wu, Z.; Agarwal, D.; Sun, J. MedCLIP: Contrastive Learning from Unpaired Medical Images and Text. In Proceedings of the EMNLP 2022, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates, 2022; pp. 3876–3887.

- Kim, D.W.; Jang, H.Y.; Kim, K.W.; Shin, Y.; Park, S.H. Design Characteristics of Studies Reporting the Performance of Artificial Intelligence Algorithms for Diagnostic Analysis of Medical Images: Results from Recently Published Papers. Korean Journal of Radiology 2019, 20, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Frid-Adar, M.; Amer, R.; Greenspan, H. Endotracheal Tube Detection and Segmentation in Chest Radiographs Using Synthetic Data. In Medical Image Computing and Computer Assisted Intervention – MICCAI 2019; Springer, 2019; Vol. 11769, pp. 784–792. [CrossRef]

- Shah, U.; Abd-Alrazeq, A.; Alam, T.; Househ, M.; Shah, Z. An Efficient Method to Predict Pneumonia from Chest X-Rays Using Deep Learning Approach. Studies in Health Technology and Informatics 2020, 272, 457–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zarshenas, A.; Liu, J.; Forti, P.; Suzuki, K. Separation of bones from soft tissue in chest radiographs: Anatomy-specific orientation-frequency-specific deep neural network convolution. Medical Physics 2019, 46, 2232–2242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murugan, R.; Goel, T. E-DiCoNet: Extreme learning machine based classifier for diagnosis of COVID-19 using deep convolutional network. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; Han, H.; Wang, L.; Li, X.; Zhou, L. Automated Radiographic Report Generation Purely on Transformer: A Multicriteria Supervised Approach. IEEE Transactions on Medical Imaging 2022, 41, 2803–2813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.Y.; et al. Segment Anything. In Proceedings of the ICCV, October 2023; pp. 4015–4026. [Google Scholar]

- ACR. SIIM-ACR Pneumothorax Segmentation, 2019.

- Mao, J.; Xu, W.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Yuille, A.L. Deep Captioning with Multimodal Recurrent Neural Networks (m-RNN). In Proceedings of the ICLR 2015, 2015, pp. 1–17.

- Umer, M.; Ashraf, I.; Ullah, S.; Mehmood, A.; Choi, G.S. COVINet: a convolutional neural network approach for predicting COVID-19 from chest X-ray images. Journal of Ambient Intelligence and Humanized Computing 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Waisy, A.S.; Al-Fahdawi, S.; Mohammed, M.A.; Abdulkareem, K.H.; Mostafa, S.A.; Maashi, M.S.; Arif, M.; Garcia-Zapirain, B. COVID-CheXNet: hybrid deep learning framework for identifying COVID-19 virus in chest X-rays images. Soft Computing 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lassau, N.; Ammari, S.; Chouzenoux, E.; Gortais, H.; Herent, P.; Devilder, M.; Soliman, S.; Meyrignac, O.; Talabard, M.P.; Lamarque, J.P.; et al. Integrating deep learning CT-scan model, biological and clinical variables to predict severity of COVID-19 patients. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rezaei, M.; Shahidi, M. Zero-shot learning and its applications from autonomous vehicles to COVID-19 diagnosis: A review. Intelligence-Based Medicine 2020, 3-4, 100005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nazarov, O.; Yaqub, M.; Nandakumar, K. On the Importance of Image Encoding in Automated Chest X-Ray Report Generation. In Proceedings of the 33rd British Machine Vision Conference 2022, BMVC 2022, London, UK, November 21-24, 2022, 2022, p. 475.

- Li, M.; Cai, W.; Liu, R.; Weng, Y.; Zhao, X.; Wang, C.; Chen, X.; Liu, Z.; Pan, C.; Li, M.; et al. FFA-IR: Towards an Explainable and Reliable Medical Report Generation Benchmark. In Proceedings of the NeurIPS Datasets and Benchmarks 2021, 2021.

- Michalopoulos, G.; Williams, K.; Singh, G.; Lin, T. MedicalSum: A Guided Clinical Abstractive Summarization Model for Generating Medical Reports from Patient-Doctor Conversations. In Proceedings of the Findings of EMNLP 2022, Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates; 2022; pp. 4741–4749. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Y.; Chen, Q.; Chen, T.; Wang, H.; Zhu, X.; Fang, Z.; Lu, Y. Evaluation of a computer-aided method for measuring the Cobb angle on chest X-rays. European Spine Journal 2019, 28, 3035–3043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banerjee, S.; Lavie, A. METEOR: An Automatic Metric for MT Evaluation with Improved Correlation with Human Judgments. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the ACL Workshop on Intrinsic and Extrinsic Evaluation Measures for Machine Translation and/or Summarization, Ann Arbor, Michigan, 2005; pp. 65–72.

- Sogancioglu, E.; Murphy, K.; Calli, E.; Scholten, E.T.; Schalekamp, S.; Ginneken, B.V. Cardiomegaly Detection on Chest Radiographs: Segmentation Versus Classification. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 94631–94642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schalekamp, S.; van Ginneken, B.; Koedam, E.; Snoeren, M.M.; Tiehuis, A.M.; Wittenberg, R.; Karssemeijer, N.; Schaefer-Prokop, C.M. Computer-aided detection improves detection of pulmonary nodules in chest radiographs beyond the support by bone-suppressed images. Radiology 2014, 272, 252–261. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- E, L.; Zhao, B.; Guo, Y.; Zheng, C.; Zhang, M.; Lin, J.; Luo, Y.; Cai, Y.; Song, X.; Liang, H. Using deep-learning techniques for pulmonary-thoracic segmentations and improvement of pneumonia diagnosis in pediatric chest radiographs. Pediatric Pulmonology 2019, 54, 1617–1626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Browne, R.F.J.; O’Reilly, G.; McInerney, D. Extraction of the Two-Dimensional Cardiothoracic Ratio from Digital PA Chest Radiographs: Correlation with Cardiac Function and the Traditional Cardiothoracic Ratio. Journal of Digital Imaging 2004, 17, 120–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).