Submitted:

28 June 2025

Posted:

30 June 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Foundations

2.1. Explainability as a Function Decomposition Problem

2.2. Scalability and Statistical Generalization

2.3. Robustness under Distributional Shifts

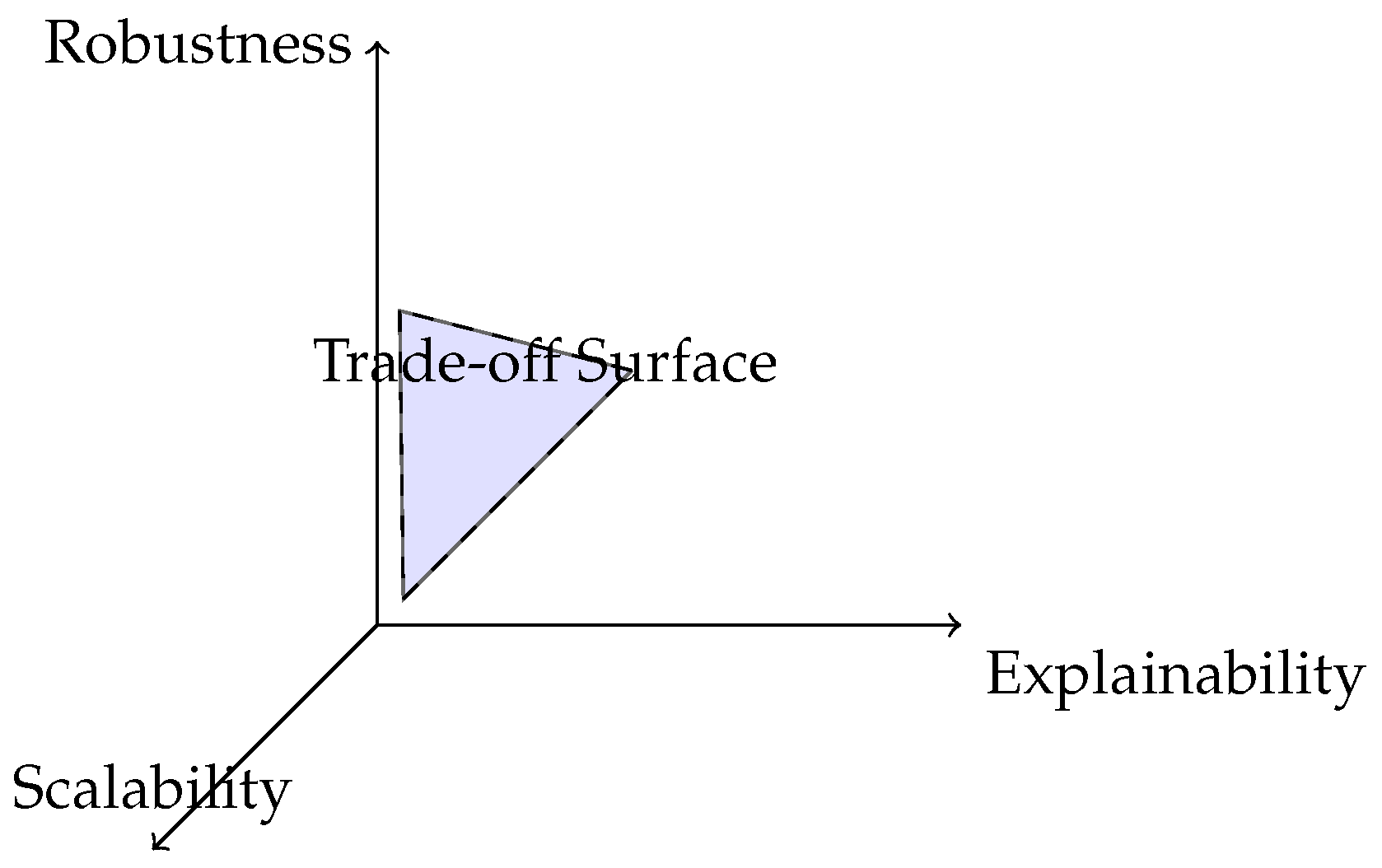

2.4. Illustration: Trade-off Surface

3. Unified Design Principles

3.1. Regularization as a Conduit for Robust and Explainable Learning

3.2. Modular and Hierarchical Architectures

3.3. Optimization Strategies and Duality

3.4. From Design to Deployment: A Systems Perspective

4. Methodological Taxonomy

4.1. Feature Attribution and Surrogate Modeling

4.2. Scalable Architectures and Efficient Optimization

4.3. Adversarial Defenses and Distributionally Robust Learning

4.4. Multi-Objective and Hybrid Approaches

5. Empirical Evaluation

5.1. Experimental Setup

- CIFAR-10 and CIFAR-100: Image classification datasets comprising natural scenes with increasing label granularity [63].

- UCI Adult and COMPAS: Tabular datasets used for fairness and interpretability evaluations in socio-economic and legal domains [64].

- MNIST-C and TinyImageNet: Benchmarks augmented with synthetic corruptions to test robustness to distribution shifts.

- HIGGS and SUSY: Large-scale physics datasets employed to assess scalability on high-dimensional numeric data [65].

5.2. Evaluation Metrics

Explainability:

Scalability:

Robustness:

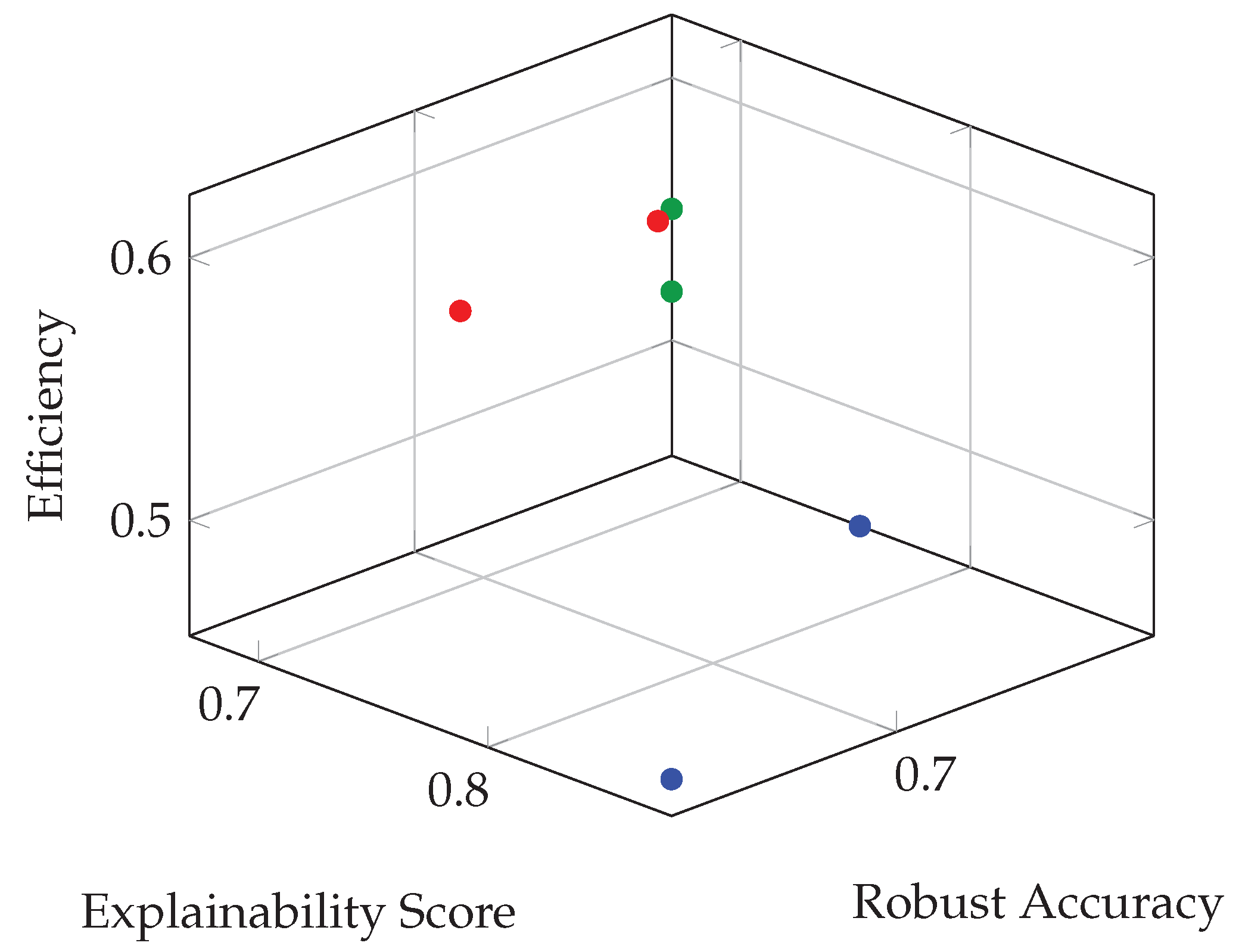

5.3. Results and Analysis

Explainability vs [74]. Robustness:

Scalability vs [75]. Robustness:

Unified Approaches:

5.4. Ablation Studies

5.5. Summary

6. Discussion

6.1. Revisiting the Triad: Complementarity and Conflict

6.2. Beyond the Model: Contextual Constraints and Operational Realities

6.3. Ethical Implications and Human Oversight

6.4. Design Recommendations and Strategic Trade-offs

- Align model constraints with domain-specific risks: In safety-critical applications, prioritize robustness and interpretability over marginal accuracy improvements.

- Use hierarchical modeling to compartmentalize complexity: Modular architectures can offer scalable computation and interpretable intermediate layers without sacrificing expressiveness.

- Evaluate explanation quality empirically and formally: Avoid relying solely on visual or anecdotal evidence; instead, benchmark explanations using perturbation-based metrics and human-grounded evaluation [92].

- Anticipate operational shifts and non-stationarity: Employ robust or adaptive learning techniques that proactively account for test-time distributional drift.

- Integrate feedback loops: Human-in-the-loop systems should enable dynamic model refinement and explanation correction based on user interaction.

6.5. From Principles to Practice: A Research Agenda

- Multi-objective optimization algorithms that can adaptively balance the three desiderata during training without exhaustive hyperparameter tuning.

- Causal explanations that provide counterfactual insight and resist adversarial manipulation, especially in the presence of confounders [93].

- Meta-learning frameworks that can generalize explainability strategies across tasks, domains, and model classes [94].

- Interactive visualization tools that integrate runtime introspection, uncertainty quantification, and real-time human feedback [95].

- Benchmark datasets and competitions explicitly designed to measure the joint performance across all three axes.

7. Conclusion

References

- Lertvittayakumjorn, P.; Toni, F. Human-grounded evaluations of explanation methods for text classification. arXiv preprint arXiv:1908.11355, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Hanawa, K.; Yokoi, S.; Hara, S.; Inui, K. Evaluation of Similarity-based Explanations, 2021. arXiv:2006.04528 [cs, stat].

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. “Why should I trust you?” Explaining the predictions of any classifier. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2016, pp. 1135–1144.

- Shankar, S.; Zamfirescu-Pereira, J.D.; Hartmann, B.; Parameswaran, A.G.; Arawjo, I. Who Validates the Validators? Aligning LLM-Assisted Evaluation of LLM Outputs with Human Preferences, 2024. arXiv:2404.12272 [cs].

- Puiutta, E.; Veith, E.M. Explainable reinforcement learning: A survey. In Proceedings of the International Cross-domain Conference for Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction. Springer; 2020; pp. 77–95. [Google Scholar]

- Lim, B.; Zohren, S. Time-series forecasting with deep learning: a survey. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A 2021, 379, 20200209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wu, S.; Fei, H.; Qu, L.; Ji, W.; Chua, T.S. NExt-GPT: Any-to-any multimodal LLM. arXiv preprint arXiv:2309.05519, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Datta, T.; Dickerson, J.P. Who’s Thinking? A Push for Human-Centered Evaluation of LLMs using the XAI Playbook, 2023. arXiv:2303.06223 [cs].

- Gilpin, L.H.; Bau, D.; Yuan, B.Z.; Bajwa, A.; Specter, M.; Kagal, L. Explaining explanations: An overview of interpretability of machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE 5th International Conference on Data Science and Advanced Analytics (DSAA). IEEE; 2018; pp. 80–89. [Google Scholar]

- Madaan, A.; Yazdanbakhsh, A. Text and patterns: For effective chain of thought, it takes two to tango. arXiv preprint arXiv:2209.07686.

- Awotunde, J.B.; Adeniyi, E.A.; Ajamu, G.J.; Balogun, G.B.; Taofeek-Ibrahim, F.A. Explainable Artificial Intelligence in Genomic Sequence for Healthcare Systems Prediction. In Connected e-Health: Integrated IoT and Cloud Computing; Springer, 2022; pp. 417–437.

- Shrivastava, A.; Kumar, P.; Anubhav.; Vondrick, C.; Scheirer, W.; Prijatelj, D.; Jafarzadeh, M.; Ahmad, T.; Cruz, S.; Rabinowitz, R.; et al. Novelty in Image Classification. In A Unifying Framework for Formal Theories of Novelty: Discussions, Guidelines, and Examples for Artificial Intelligence; Springer, 2023; pp. 37–48.

- Chefer, H.; Gur, S.; Wolf, L. Generic attention-model explainability for interpreting bi-modal and encoder-decoder transformers. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, 2021, pp. 397–406.

- Zniyed, Y.; Nguyen, T.P.; et al. Efficient tensor decomposition-based filter pruning. Neural Networks 2024, 178, 106393. [Google Scholar]

- Job, S.; Tao, X.; Li, L.; Xie, H.; Cai, T.; Yong, J.; Li, Q. Optimal treatment strategies for critical patients with deep reinforcement learning. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology 2024, 15, 1–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Willard, J.; Jia, X.; Xu, S.; Steinbach, M.; Kumar, V. Integrating scientific knowledge with machine learning for engineering and environmental systems. ACM Computing Surveys 2022, 55, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saranya, A.; Subhashini, R. A systematic review of Explainable Artificial Intelligence models and applications: Recent developments and future trends. Decision Analytics Journal, 2023; 100230. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Z.; Lin, Y.; Cao, Y.; Hu, H.; Wei, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lin, S.; Guo, B. Swin transformer: Hierarchical vision transformer using shifted windows. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF international conference on computer vision, 2021, pp. 10012–10022.

- Abnar, S.; Zuidema, W. Quantifying attention flow in transformers. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.00928, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Chaddad, A.; Peng, J.; Xu, J.; Bouridane, A. Survey of explainable AI techniques in healthcare. Sensors 2023, 23, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Sappagh, S.; Alonso, J.M.; Islam, S.R.; Sultan, A.M.; Kwak, K.S. A multilayer multimodal detection and prediction model based on explainable artificial intelligence for Alzheimer’s disease. Scientific Reports 2021, 11, 2660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arrieta, A.B.; Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Del Ser, J.; Bennetot, A.; Tabik, S.; Barbado, A.; García, S.; Gil-López, S.; Molina, D.; Benjamins, R.; et al. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Concepts, Taxonomies, Opportunities and Challenges toward Responsible AI, 2019. arXiv:1910.10045 [cs].

- Voita, E.; Talbot, D.; Moiseev, F.; Sennrich, R.; Titov, I. Analyzing multi-head self-attention: Specialized heads do the heavy lifting, the rest can be pruned. arXiv preprint arXiv:1905.09418, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, C.; Liu, J.; Nemati, S.; Yin, G. Reinforcement learning in healthcare: A survey. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2021, 55, 1–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doshi-Velez, F.; Kim, B. Towards a rigorous science of interpretable machine learning. arXiv preprint arXiv:1702.08608, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, S.; Chen, Q.; Wang, X.; Zheng, C.; Peng, Z.; Yin, M.; Ma, X. Towards Human-AI Deliberation: Design and Evaluation of LLM-Empowered Deliberative AI for AI-Assisted Decision-Making, 2024. arXiv:2403.16812 [cs].

- Roy, A.; Maaten, L.v.d.; Witten, D. UMAP reveals cryptic population structure and phenotype heterogeneity in large genomic cohorts. PLoS genetics 2020, 16, e1009043. [Google Scholar]

- Tjoa, E.; Guan, C. A survey on Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): Toward medical XAI. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2020, 32, 4793–4813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, W. Stability of machine learning algorithms. PhD thesis, Purdue University, 2015.

- Acheampong, F.A.; Nunoo-Mensah, H.; Chen, W. Transformer models for text-based emotion detection: a review of BERT-based approaches. Artificial Intelligence Review 2021, 54, 5789–5829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atakishiyev, S.; Salameh, M.; Yao, H.; Goebel, R. Explainable artificial intelligence for autonomous driving: A comprehensive overview and field guide for future research directions. arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.11561, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Lakkaraju, H.; Bach, S.H.; Leskovec, J. Interpretable decision sets: A joint framework for description and prediction. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, 2016, pp. 1675–1684.

- Chefer, H.; Gur, S.; Wolf, L. Transformer interpretability beyond attention visualization. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2021, pp. 782–791.

- Nguyen, T.T.; Le Nguyen, T.; Ifrim, G. A model-agnostic approach to quantifying the informativeness of explanation methods for time series classification. In Proceedings of the International Workshop on Advanced Analytics and Learning on Temporal Data. Springer, 2020, pp. 77–94.

- Mankodiya, H.; Obaidat, M.S.; Gupta, R.; Tanwar, S. XAI-AV: Explainable artificial intelligence for trust management in autonomous vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Communications, Computing, Cybersecurity, and Informatics (CCCI). IEEE, 2021, pp. 1–5.

- Guidotti, R. Counterfactual explanations and how to find them: literature review and benchmarking. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2022, pp. 1–55.

- Yadav, B. Generative AI in the Era of Transformers: Revolutionizing Natural Language Processing with LLMs, 2024.

- Markus, A.F.; Kors, J.A.; Rijnbeek, P.R. The role of explainability in creating trustworthy artificial intelligence for health care: a comprehensive survey of the terminology, design choices, and evaluation strategies. Journal of Biomedical Informatics 2021, 113, 103655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hellas, A.; Leinonen, J.; Sarsa, S.; Koutcheme, C.; Kujanpää, L.; Sorva, J. Exploring the Responses of Large Language Models to Beginner Programmers’ Help Requests. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2023 ACM Conference on International Computing Education Research V.1, 2023, pp. 93–105. arXiv:2306.05715 [cs]. [CrossRef]

- Krizhevsky, A.; Sutskever, I.; Hinton, G.E. Imagenet classification with deep convolutional neural networks. Communications of the ACM 2017, 60, 84–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amann, J.; Blasimme, A.; Vayena, E.; Frey, D.; Madai, V.I.; Consortium, P. Explainability for artificial intelligence in healthcare: a multidisciplinary perspective. BMC Medical Informatics and Decision Making 2020, 20, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Chiang, W.L.; Sheng, Y.; Zhuang, S.; Wu, Z.; Zhuang, Y.; Lin, Z.; Li, Z.; Li, D.; Xing, E.P.; et al. Judging LLM-as-a-Judge with MT-Bench and Chatbot Arena, 2023. arXiv:2306.05685 [cs].

- Jain, S.; Wallace, B.C. Attention is not explanation. arXiv preprint arXiv:1902.10186, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Weller, A. Transparency: motivations and challenges. In Explainable AI: interpreting, explaining and visualizing deep learning; Springer, 2019; pp. 23–40.

- Zafar, M.R.; Khan, N. Deterministic local interpretable model-agnostic explanations for stable explainability. Machine Learning and Knowledge Extraction 2021, 3, 525–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amodei, D.; Olah, C.; Steinhardt, J.; Christiano, P.; Schulman, J.; Mané, D. Concrete problems in AI safety. arXiv preprint arXiv:1606.06565, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Tiňo, P.; Leonardis, A.; Tang, K. A survey on neural network interpretability. IEEE Transactions on Emerging Topics in Computational Intelligence 2021, 5, 726–742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonyan, K.; Vedaldi, A.; Zisserman, A. Deep inside convolutional networks: Visualising image classification models and saliency maps. arXiv preprint arXiv:1312.6034, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Springenberg, J.T.; Dosovitskiy, A.; Brox, T.; Riedmiller, M. Interpretable convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, 2014, pp. 1441–1448.

- Ward, A.; Sarraju, A.; Chung, S.; Li, J.; Harrington, R.; Heidenreich, P.; Palaniappan, L.; Scheinker, D.; Rodriguez, F. Machine learning and atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk prediction in a multi-ethnic population. NPJ Digital Medicine 2020, 3, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zniyed, Y.; Nguyen, T.P.; et al. Enhanced network compression through tensor decompositions and pruning. IEEE Transactions on Neural Networks and Learning Systems 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Sivertsen, C.; Salimbeni, G.; Løvlie, A.S.; Benford, S.D.; Zhu, J. Machine Learning Processes as Sources of Ambiguity: Insights from AI Art. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2024, pp. 1–14.

- Holzinger, A.; Langs, G.; Denk, H.; Zatloukal, K.; Müller, H. Causability and explainability of artificial intelligence in medicine. Wiley Interdisciplinary Reviews: Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2019, 9, e1312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sadeghi Tabas, S. Explainable Physics-informed Deep Learning for Rainfall-runoff Modeling and Uncertainty Assessment across the Continental United States 2023.

- McGehee, D.V.; Brewer, M.; Schwarz, C.; Smith, B.W.; et al. Review of automated vehicle technology: Policy and implementation implications. Technical report, Iowa. Dept. of Transportation, 2016.

- Nwakanma, C.I.; Ahakonye, L.A.C.; Njoku, J.N.; Odirichukwu, J.C.; Okolie, S.A.; Uzondu, C.; Ndubuisi Nweke, C.C.; Kim, D.S. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) for intrusion detection and mitigation in intelligent connected vehicles: A review. Applied Sciences 2023, 13, 1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Madumal, P.; Miller, T.; Sonenberg, L.; Vetere, F. Explainable reinforcement learning through a causal lens. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, 2020, Vol. 34, pp. 2493–2500.

- Schwalbe, G.; Finzel, B. A comprehensive taxonomy for explainable artificial intelligence: a systematic survey of surveys on methods and concepts. Data Mining and Knowledge Discovery 2023, pp. 1–59.

- Kim, J.; Rohrbach, A.; Darrell, T.; Canny, J.; Akata, Z. Textual explanations for self-driving vehicles. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the European conference on computer vision (ECCV), 2018, pp. 563–578.

- Rahman, M.; Polunsky, S.; Jones, S. Transportation policies for connected and automated mobility in smart cities. In Smart Cities Policies and Financing; Elsevier, 2022; pp. 97–116.

- Jie, Y.W.; Satapathy, R.; Mong, G.S.; Cambria, E.; et al. How Interpretable are Reasoning Explanations from Prompting Large Language Models? arXiv preprint arXiv:2402.11863, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wells, L.; Bednarz, T. Explainable AI and reinforcement learning—a systematic review of current approaches and trends. Frontiers in Artificial Intelligence 2021, 4, 550030. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AlShami, A.; Boult, T.; Kalita, J. Pose2Trajectory: Using transformers on body pose to predict tennis player’s trajectory. Journal of Visual Communication and Image Representation 2023, 97, 103954. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jordan, M.I.; Mitchell, T.M. Machine learning: Trends, perspectives, and prospects. Science 2015, 349, 255–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Datcu, M.; Huang, Z.; Anghel, A.; Zhao, J.; Cacoveanu, R. Explainable, physics-aware, trustworthy artificial intelligence: A paradigm shift for synthetic aperture radar. IEEE Geoscience and Remote Sensing Magazine 2023, 11, 8–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bussone, A.; Stumpf, S.; O’Sullivan, D. The role of explanations on trust and reliance in clinical decision support systems. In Proceedings of the 2015 International Conference on Healthcare Informatics. IEEE; 2015; pp. 160–169. [Google Scholar]

- Ahmed, U.; Srivastava, G.; Yun, U.; Lin, J.C.W. EANDC: An explainable attention network based deep adaptive clustering model for mental health treatment. Future Generation Computer Systems 2022, 130, 106–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thampi, A. Interpretable AI: Building explainable machine learning systems; Simon and Schuster, 2022.

- Wang, B.; Min, S.; Deng, X.; Shen, J.; Wu, Y.; Zettlemoyer, L.; Sun, H. Towards understanding chain-of-thought prompting: An empirical study of what matters. arXiv preprint arXiv:2212.10001, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Heuillet, A.; Couthouis, F.; Díaz-Rodríguez, N. Explainability in deep reinforcement learning. Knowledge-Based Systems 2021, 214, 106685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krause, J.; Perer, A.; Ng, K. Interacting with predictions: Visual inspection of black-box machine learning models. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the 2016 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, 2016, pp. 5686–5697.

- Shankar, S.; Zamfirescu-Pereira, J.; Hartmann, B.; Parameswaran, A.G.; Arawjo, I. Who Validates the Validators? Aligning LLM-Assisted Evaluation of LLM Outputs with Human Preferences. arXiv preprint arXiv:2404.12272, 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Miller, T. Explanation in artificial intelligence: Insights from the social sciences. Artificial Intelligence 2019, 267, 1–38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Karim, M.M.; Li, Y.; Qin, R. Toward explainable artificial intelligence for early anticipation of traffic accidents. Transportation Research Record 2022, 2676, 743–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, T.; Weitz, K.; André, E.; Amir, O. Local and global explanations of agent behavior: Integrating strategy summaries with saliency maps. Artificial Intelligence 2021, 301, 103571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sundararajan, M.; Taly, A.; Yan, Q. Axiomatic attribution for deep networks. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning. PMLR; 2017; pp. 3319–3328. [Google Scholar]

- Malone, D.P.; Creamer, J.F. NHTSA and the next 50 years: Time for congress to act boldly (again). Technical report, SAE Technical Paper, 2016.

- Lötsch, J.; Kringel, D.; Ultsch, A. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI) in biomedicine: Making AI decisions trustworthy for physicians and patients. BioMedInformatics 2021, 2, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albahri, A.; Duhaim, A.M.; Fadhel, M.A.; Alnoor, A.; Baqer, N.S.; Alzubaidi, L.; Albahri, O.; Alamoodi, A.; Bai, J.; Salhi, A.; et al. A systematic review of trustworthy and Explainable Artificial Intelligence in healthcare: Assessment of quality, bias risk, and data fusion. Information Fusion 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minh, D.; Wang, H.X.; Li, Y.F.; Nguyen, T.N. Explainable Artificial Intelligence: a comprehensive review. Artificial Intelligence Review 2022, pp. 1–66.

- Corso, A.; Kochenderfer, M.J. Interpretable safety validation for autonomous vehicles. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 23rd International Conference on Intelligent Transportation Systems (ITSC). IEEE; 2020; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Dwivedi, R.; Dave, D.; Naik, H.; Singhal, S.; Omer, R.; Patel, P.; Qian, B.; Wen, Z.; Shah, T.; Morgan, G.; et al. Explainable AI (XAI): Core ideas, techniques, and solutions. ACM Computing Surveys 2023, 55, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choudhary, K.; DeCost, B.; Chen, C.; Jain, A.; Tavazza, F.; Cohn, R.; Park, C.W.; Choudhary, A.; Agrawal, A.; Billinge, S.J.; et al. Recent advances and applications of deep learning methods in materials science. npj Computational Materials 2022, 8, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, R.; Sharma, J.; Jindal, S. Time Series Forecasting Using Machine Learning. In Proceedings of the Advances in Computing and Data Sciences: 4th International Conference, ICACDS 2020, Valletta, Malta, April 24–25, 2020, Revised Selected Papers 4. Springer, 2020, pp. 372–381.

- Aziz, S.; Dowling, M.; Hammami, H.; Piepenbrink, A. Machine learning in finance: A topic modeling approach. European Financial Management 2022, 28, 744–770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohseni, S.; Zarei, N.; Ragan, E.D. A multidisciplinary survey and framework for design and evaluation of explainable AI systems. ACM Transactions on Interactive Intelligent Systems (TiiS) 2021, 11, 1–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pilania, G. Machine learning in materials science: From explainable predictions to autonomous design. Computational Materials Science 2021, 193, 110360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Regulation, P. Regulation (EU) 2016/679 of the European Parliament and of the Council. Regulation (eu) 2016, 679, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kerasidou, A. Ethics of artificial intelligence in global health: Explainability, algorithmic bias and trust. Journal of Oral Biology and Craniofacial Research 2021, 11, 612–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lee, K.; Ayyasamy, M.V.; Ji, Y.; Balachandran, P.V. A comparison of explainable artificial intelligence methods in the phase classification of multi-principal element alloys. Scientific Reports 2022, 12, 11591. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhou, J.; Gandomi, A.H.; Chen, F.; Holzinger, A. Evaluating the Quality of Machine Learning Explanations: A Survey on Methods and Metrics. Electronics 2021, 10, 593, Number: 5 Publisher: Multidisciplinary Digital Publishing Institute. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drenkow, N.; Sani, N.; Shpitser, I.; Unberath, M. A systematic review of robustness in deep learning for computer vision: Mind the gap? arXiv preprint arXiv:2112.00639, 2021. [Google Scholar]

- Dietvorst, B.J.; Simmons, J.P.; Massey, C. Algorithm aversion: people erroneously avoid algorithms after seeing them err. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General 2015, 144, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, S.; Abuhmed, T.; El-Sappagh, S.; Muhammad, K.; Alonso-Moral, J.M.; Confalonieri, R.; Guidotti, R.; Del Ser, J.; Díaz-Rodríguez, N.; Herrera, F. Explainable Artificial Intelligence (XAI): What we know and what is left to attain Trustworthy Artificial Intelligence. Information fusion 2023, 99, 101805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bostrom, N.; Yudkowsky, E. The ethics of Artificial Intelligence. In Artificial Intelligence Safety and Security; Chapman and Hall/CRC, 2018; pp. 57–69.

- Lipton, Z.C. The mythos of model interpretability: In machine learning, the concept of interpretability is both important and slippery. Queue 2018, 16, 31–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nourani, M.; Kabir, S.; Mohseni, S.; Ragan, E.D. The effects of meaningful and meaningless explanations on trust and perceived system accuracy in intelligent systems. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Human Computation and Crowdsourcing, 2019, Vol. 7, pp. 97–105.

- Guidotti, R.; Monreale, A.; Ruggieri, S.; Turini, F.; Giannotti, F.; Pedreschi, D. A survey of methods for explaining black box models. ACM Computing Surveys (CSUR) 2018, 51, 1–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudin, C. Stop explaining black box machine learning models for high stakes decisions and use interpretable models instead. Nature Machine Intelligence 2019, 1, 206–215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al Shami, A.K. Generating Tennis Player by the Predicting Movement Using 2D Pose Estimation. PhD thesis, University of Colorado Colorado Springs, 2022.

- Rudin, C.; Radin, J. Why are we using black box models in AI when we don’t need to? A lesson from an explainable AI competition. Harvard Data Science Review 2019, 1, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).