Submitted:

05 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Results (Table 1)

|

3.1. Prevalence and Impact of Sexual Dysfunction in Cancer Patients

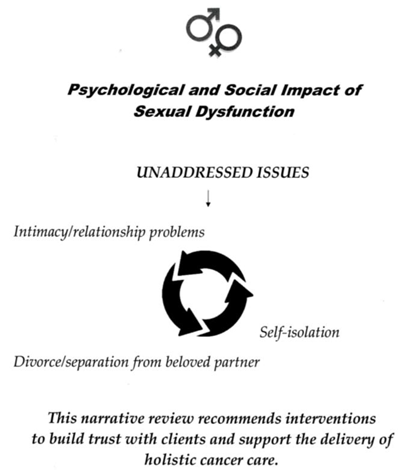

3.2. Psychological and Social Impact of Sexual Dysfunction

3.3. Barriers to Addressing Sexual Dysfunction in Cancer Care

3.4. Interventions for Managing Sexual Dysfunction in Cancer Patients—Training Programs to Build Trust of Patients and Achieve Holistic Cancer Care

3.5. How to Deal with Nurses' Attitudes and Beliefs About Sexual Health

3.6. Global Efforts in Addressing Oncology Sexual Health Education

4. Conclusions

References

- Alqaisi, O., Subih, M., Joseph, K., Yu, E., Tai P. Oncology Nurses' Attitudes, Knowledge, and Practices in Providing Sexuality Care to Cancer Patients: A Scoping Review. Curr. Oncol. 2025, 32, x. (Accepted for public ation). [CrossRef]

- Acquati, C., Zebrack, B. J., Faul, A. C., Embry, L., Aguilar, C., Block, R., et al. Sexual functioning among young adult cancer patients: a 2-year longitudinal study. Cancer, 2018, 124(2), 398-405.. [CrossRef]

- Bakker, R. M., Mens, J. W. M., De Groot, H. E., Tuijnman-Raasveld, C. C., Braat, C., Hompus, W. C., et al. A nurse-led sexual reha-bilitation intervention after radiotherapy for gynecological cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer 2017, 25, 729-737..

- Barbera, L., Zwaal, C., Elterman, D., McPherson, K., Wolfman, W., Katz, A., et al. Interventions to address sexual problems in people with cancer. Curr Oncol. 2017, 24(3), 192. . [CrossRef]

- Celentano, V., Cohen, R., Warusavitarne, J., Faiz, O., & Chand, M. Sexual dysfunction following rectal cancer surgery. International Journal of Colorectal Disease, 2017, 32, 1523-1530..

- Proctor CJ, Reiman AJ, Brunelle C, Best LA. Intimacy and sexual functioning after cancer: The intersection with psychological flexibility. PLOS Ment Health. 2024;1(1):e0000001. [CrossRef]

- Smith A, Baron R. A Workshop for Educating Nurses to Address Sexual Health in Patients With Breast Cancer. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2015 Jun 1;19(3):248–50.

- Sadovsky R, Basson R, Krychman M, Morales AM, Schover L, Wang R, et al. Cancer and Sexual Problems. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2010 Jan;7(1):349–73.

- World Health Organization. Sexual and Reproductive Health: Defining Sexual Health. 2014. Available online: https://www.who.int/reproductivehealth/publications/sexual_health/defining_sexual_health.pdf. Accessed on 1 June 2025.

- World Health Organization. (2022). Cancer Fact Sheets. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/cancer. Accessed on 1 June 2025.

- World Health Organization. What constitutes sexual health? Progress in reproductive health research [serial online]. 67:2Y3. http://www.who.int/ reproductive-health/hrp/progress/67.pdf. Accessed October 15, 2009.

- Ahn SH, Kim JH. Healthcare Professionals’ Attitudes and Practice of Sexual Health Care: Preliminary Study for Developing Training Program. Frontiers in Public Health. 2020 Oct 16;8(8). [CrossRef]

- Jonsdottir JI, Zoëga S, Saevarsdottir T, Sverrisdottir A, Thorsdottir T, Einarsson GV, et al. Changes in attitudes, practices and barriers among oncology health care professionals regarding sexual health care: Outcomes from a 2-year educational intervention at a University Hospital. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2016 Apr; 21:24–30. [CrossRef]

- Oskay U, Can G, Basgol S. Discussing Sexuality with Cancer Patients: Oncology Nurses Attitudes and Views. Asian Pacific Journal of Cancer Prevention. 2014 Sep 15;15(17):7321–6. [CrossRef]

- Reese JB, Beach MC, Smith KC, Bantug ET, Casale KE, Porter LS, et al. Effective patient-provider communication about sexual concerns in breast cancer: a qualitative study. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2017 Apr 27;25(10):3199–207.

- Krouwel EM, Nicolai MPJ, van Steijn-van Tol AQMJ, Putter H, Osanto S, Pelger RCM, et al. Addressing changed sexual functioning in cancer patients: A cross-sectional survey among Dutch oncology nurses. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2015 Dec;19(6):707–15.

- Wazqar DY. Sexual health care in cancer patients: A survey of healthcare providers’ knowledge, attitudes and barriers. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2020 Aug 26;29(21-22):4239–47.

- Åling M, Lindgren A, Löfall H, Okenwa-Emegwa L. A Scoping Review to Identify Barriers and Enabling Factors for Nurse–Patient Discussions on Sexuality and Sexual Health. Nursing Reports. 2021 Apr 16;11(2):253–66. [CrossRef]

- Paulsen A, Ingvild Vistad, Liv Fegran. Nurse–patient sexual health communication in gynaecological cancer follow-up: A qualitative study from nurses’ perspectives. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2023 Jun 26;79(12).

- Quinn C, Platania-Phung C, Bale C, Happell B, Hughes E. Understanding the current sexual health service provision for mental health consumers by nurses in mental health settings: Findings from a Survey in Australia and England. International Journal of Mental Health Nursing. 2018 Mar 25;27(5):1522–34. [CrossRef]

- Frederick NN, Campbell K, Kenney LB, Moss K, Speckhart A, Bober SL. Barriers and facilitators to sexual and reproductive health communication between pediatric oncology clinicians and adolescent and young adult patients: The clinician perspective. Pediatric Blood & Cancer. 2018 Apr 26;65(8):e27087.

- Williams NF, Hauck YL, Bosco AM. Nurses’ perceptions of providing psychosexual care for women experiencing gynaecological cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2017 Oct;30(30):35–42. [CrossRef]

- Dai Y, Cook OY, Yeganeh L, Huang C, Ding J, Johnson CE. Patient-Reported Barriers and Facilitators to Seeking and Accessing Support in Gynecologic and Breast Cancer Survivors With Sexual Problems: A Systematic Review of Qualitative and Quantitative Studies. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2020 Jul;17(7):1326–58.

- Tramacere F, Lancellotta V, Casà C, Fionda B, Cornacchione P, Mazzarella C, et al. Assessment of Sexual Dysfunction in Cervical Cancer Patients after Different Treatment Modality: A Systematic Review. Medicina [Internet]. 2022 Sep 1 [cited 2023 Feb 25];58(9):1223. Available from: https://www.mdpi.com/1648-9144/58/9/1223.

- Valpey R, Kucherer S, Nguyen J. Sexual dysfunction in female cancer survivors: A narrative review. General Hospital Psychiatry. 2019 Sep;60(60):141–7.

- Qi A, Li Y, Sun H, Jiao H, Liu Y, Chen Y. Incidence and risk factors of sexual dysfunction in young breast cancer survivors. Annals of Palliative Medicine. 2021 Apr;10(4):4428–34. [CrossRef]

- Chang YC, Chang SR, Chiu SC. Sexual Problems of Patients With Breast Cancer After Treatment. Cancer Nursing. 2018 Apr;42(5):1.

- Papadopoulou C, Sime C, Rooney K, Kotronoulas G. Sexual health care provision in cancer nursing care: A systematic review on the state of evidence and deriving international competencies chart for cancer nurses. International Journal of Nursing Studies. 2019 Dec;100(100):103405.

- Apiradee Pimsen, Lin W, Lin C, Kuo Y, Shu B. Healthcare providers’ experiences in providing sexual health care to breast cancer survivors: A mixed-methods systematic review. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2023 Dec 18;33(3):797–816..

- Kim JH, Yang Y, Hwang ES. The Effectiveness of Psychoeducational Interventions Focused on Sexuality in Cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2015;38(5):E32–42. [CrossRef]

- Chang CP, Wilson CM, Rowe K, Snyder J, Dodson M, Deshmukh V, et al. Sexual dysfunction among gynecologic cancer survivors in a population-based cohort study. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2022 Dec 17;31(1). [CrossRef]

- Del Pup, L., Nappi, R. E., & Biglia, N. (2017). Sexual dysfunction in gynecologic cancer patients. WCRJ, 4(1), e835..

- Amirmohammad Dahouri, Sahebihagh MH, Gilani N. Factors associated with sexual dysfunction in patients with colorectal cancer in Iran: a cross-sectional study. Scientific Reports. 2024 Feb 28;14(1).

- Correia RA, Bonfim CV do, Feitosa KMA, Furtado BMASM, Ferreira DK da S, Santos SL dos. Disfunção sexual após tratamento para o câncer do colo do útero. Revista da Escola de Enfermagem da USP. 2020;54(54).

- Bond CB, Jensen PT, Groenvold M, Johnsen AT. Prevalence and possible predictors of sexual dysfunction and self-reported needs related to the sexual life of advanced cancer patients. Acta Oncologica. 2019 Feb 6;58(5):769–75. [CrossRef]

- BC, T., MS, A. R., & MN, M. R. (2014). The Prevalence and Risk Factors of Sexual Dysfunction in Gynaecological Cancer Patients. Medicine & Health (Universiti Kebangsaan Malaysia), 9(1)..

- Oldertrøen Solli K, Boer M, Nyheim Solbrække K, Thoresen L. Male partners’ experiences of caregiving for women with cervical cancer—a qualitative study. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2018 Oct 26;28(5-6):987–96.

- Duran E, Tanriseven M, Ersoz N, Oztas M, Ozerhan IH, Kilbas Z, et al. Urinary and sexual dysfunction rates and risk factors following rectal cancer surgery. International Journal of Colorectal Disease. 2015 Aug 13;30(11):1547–55. [CrossRef]

- Twitchell DK, Wittmann DA, Hotaling JM, Pastuszak AW. Psychological Impacts of Male Sexual Dysfunction in Pelvic Cancer Survivorship. Sexual Medicine Reviews. 2019 Oct;7(4):614–26. [CrossRef]

- Emel Cihan, Fatma Vural. Effect of a telephone-based perioperative nurse-led counselling programme on unmet needs, quality of life and sexual function in colorectal cancer patients: A non-randomised quasi-experimental study. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2024 Feb 1;68(68):102504–4.

- Sousa Rodrigues Guedes T, Barbosa Otoni Gonçalves Guedes M, de Castro Santana R, Costa da Silva JF, Almeida Gomes Dantas A, Ochandorena-Acha M, et al. Sexual Dysfunction in Women with Cancer: A Systematic Review of Longitudinal Studies. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2022 Sep 21;19(19):11921.

- Karacan Y, Yildiz H, Demircioglu B, Ali R. Evaluation of Sexual Dysfunction in Patients with Hematological Malignancies. Asia-Pacific Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2021 Jan;8(1):51–7. [CrossRef]

- Olsson C, Sandin-Bojö AK, Bjuresäter K, Larsson M. Changes in Sexuality, Body Image and Health Related Quality of Life in Patients Treated for Hematologic Malignancies: A Longitudinal Study. Sexuality and Disability. 2016 Oct 15;34(4):367–88.

- Byrne M, Murphy P, D’Eath M, Doherty S, Jaarsma T. Association Between Sexual Problems and Relationship Satisfaction Among People with Cardiovascular Disease. The Journal of Sexual Medicine. 2017 May 1;14(5):666–74.

- Vizza R, Capomolla EM, Tosetto L, Corrado G, Bruno V, Chiofalo B, et al. Sexual dysfunctions in breast cancer patients: evidence in context. Sexual Medicine Reviews [Internet]. 2023 Jun 27 [cited 2023 Oct 20];11(3):179–95. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/37076125/.

- Maree J, Fitch MI. Holding conversations with cancer patients about sexuality: Perspectives from Canadian and African healthcare professionals. PubMed. 2019 Jan 1;29(1):64–9.

- Schover LR, van der Kaaij M, van Dorst E, Creutzberg C, Huyghe E, Kiserud CE. Sexual dysfunction and infertility as late effects of cancer treatment. EJC Supplements [Internet]. 2014 Jun 1 [cited 2020 Apr 27];12(1):41–53. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC4250536/.

- Cagle JG, Bolte S. Sexuality and Life-Threatening Illness: Implications for Social Work and Palliative Care. Health & Social Work. 2009 Aug 1;34(3):223–33. [CrossRef]

- Redelman MJ. Is There a Place for Sexuality in the Holistic Care of Patients in the Palliative Care Phase of Life? American Journal of Hospice and Palliative Medicine®. 2008 Apr 10;25(5):366–71.

- Harris MG. Sexuality and Menopause: Unique Issues in Gynecologic Cancer. Seminars in Oncology Nursing. 2019 Apr;35(2):211–6.

- Al-Ghabeesh SH, Al-Kalaldah M, Rayan A, Al-Rifai A, Al-Halaiqa F. Psychological distress and quality of life among Jordanian women diagnosed with breast cancer: The role of trait mindfulness. European Journal of Cancer Care. 2019 May 8;28(5). [CrossRef]

- Jonsdottir JI, Zoëga S, Saevarsdottir T, Sverrisdottir A, Thorsdottir T, Einarsson GV, et al. Changes in attitudes, practices and barriers among oncology health care professionals regarding sexual health care: Outcomes from a 2-year educational intervention at a University Hospital. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2016 Apr;21(21):24–30.

- Kedde H, van de Wiel HBM, Weijmar Schultz WCM, Wijsen C. Sexual dysfunction in young women with breast cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2012 Jun 20;21(1):271–80. [CrossRef]

- Serçekuş Ak P, Partlak Günüşen N, Göral Türkcü S, Özkan S. Sexuality in Muslim Women With Gynecological Cancer. Cancer Nursing. 2018 Nov;43(1):1.

- Mansour SE, Mohamed HE. Handling Sexuality Concerns in Women with Gynecological Cancer: Egyptian Nurse’s Knowledge and Attitudes. Journal of Education and Practice. 2015 Dec 18;6(3):146–59.

- Eid K, Christensen S, Hoff J, Yadav K, Burtson P, Kuriakose M, et al. Sexual Health Education: Knowledge Level of Oncology Nurses and Barriers to Discussing Concerns With Patients. Clinical Journal of Oncology Nursing [Internet]. 2020 Aug 1 [cited 2021 Feb 24];24(4):E50–6. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/32678358/.

- Zeng YC, Li Q, Wang N, Ching SSY, Loke AY. Chinese Nurses’ Attitudes and Beliefs Toward Sexuality Care in Cancer Patients. Cancer Nursing. 2011 Mar;34(2):E14–20.

- Zeng YC, Liu X, Loke AY. Addressing sexuality issues of women with gynaecological cancer: Chinese nurses’ attitudes and practice. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2011 Jun 9;68(2):280–92. [CrossRef]

- Paterson CL, Lengacher CA, Donovan KA, Kip KE, Tofthagen CS. Body Image in Younger Breast Cancer Survivors. Cancer Nursing. 2015 Apr;39(1):1. [CrossRef]

- Ümran Yeşiltepe Oskay, Nezihe Kızılkaya Beji, Bal MD, Sema Dereli Yılmaz. Evaluation of Sexual Function in Patients with Gynecologic Cancer and Evidence-Based Nursing Interventions. Sexuality and Disability. 2010 Nov 24;29(1):33–41.

- Neenan C, Chatzi AV. Quality of Nursing Care: Addressing Sexuality as Part of Prostate Cancer Management, an Umbrella Review. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2025 Jan 9;

- Forbat L, White I, Marshall-Lucette S, Kelly D. Discussing the sexual consequences of treatment in radiotherapy and urology consultations with couples affected by prostate cancer. BJU International. 2011 Jun 1;109(1):98–103.

- Moore A, Higgins A, Sharek D. Barriers and facilitators for oncology nurses discussing sexual issues with men diagnosed with testicular cancer. European Journal of Oncology Nursing. 2013 Aug;17(4):416–22. [CrossRef]

- Benoot C, Enzlin P, Peremans L, Bilsen J. Addressing sexual issues in palliative care: A qualitative study on nurses’ attitudes, roles and experiences. Journal of Advanced Nursing. 2018 May 9;74(7):1583–94.

- Al-Ghabeesh, S. H., Bashayreh, I. H., Saifan, A. R., Rayan, A., & Alshraifeen, A. A. (2020). Barriers to effective pain management in cancer patients from the perspective of patients and family caregivers: A qualitative study. Pain Management Nursing, 21(3), 238-244..

- Rayan A, Hussni Al-Ghabeesh S, Qarallah I. Critical Care Nurses’ Attitudes, Roles, and Barriers Regarding Breaking Bad News. SAGE Open Nursing. 2022 Jan;8(8):237796082210899. [CrossRef]

- Depke J, Onitilo A. Sexual health assessment and counseling: oncology nurses’ perceptions, practices, and perceived barriers. The Journal of Community and Supportive Oncology. 2015 Dec;13(12):442–5. [CrossRef]

- Algier, L., & Kav, S. (2008). Nurses' approach to sexuality-related issues in patients receiving cancer treatments. Turkish Journal of Cancer, 38(3).

- Akhu-Zaheya LM, Masadeh AB. Sexual information needs of Arab-Muslim patients with cardiac problems. European Journal of Cardiovascular Nursing. 2015 Jul 22;14(6):478–85.

- David, K. (2024). Cancer in Sexual and Gender Minorities: Role of Oncology RNs in Health Equity. Number 3/June 2024, 28(3), 329-334..

- A. Shahin M, Amin Ali Gaafar H, Lotfi Afifi Alqersh D. Effect of Nursing Counseling Guided by BETTER Model on Sexuality, Marital Satisfaction and Psychological Status among Breast Cancer Women. Egyptian Journal of Health Care. 2021 Jun 1;12(2):75–95.

- Bakker RM, Mens JWM, de Groot HE, Tuijnman-Raasveld CC, Braat C, Hompus WCP, et al. A nurse-led sexual rehabilitation intervention after radiotherapy for gynecological cancer. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2016 Oct 27;25(3):729–37.

- Mrad H, Chouinard A, Pichette R, Piché L, Bilodeau K. Feasibility and Impact of an Online Simulation Focusing on Nursing Communication About Sexual Health in Gynecologic Oncology. Journal of Cancer Education. 2023 Sep 12;39(1):3–11. [CrossRef]

- Williams M, Addis G. Addressing patient sexuality issues in cancer and palliative care. British Journal of Nursing. 2021 May 27;30(10):S24–8.

- cakar B, karaca B, Uslu R. Sexual dysfunction in cancer patients: a review [Internet]. pub med . JBUON; 2013. Available from: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/24344003/.

- Arthur SS, Dorfman CS, Massa LA, Shelby RA. Managing female sexual dysfunction. Urologic Oncology: Seminars and Original Investigations. 2021 Jul;40(8).

- Afiyanti Y. Attitudes, Belief, and Barriers of Indonesian Oncology Nurses on Providing Assistance to Overcome Sexuality Problem. Nurse Media Journal of Nursing. 2017 Jul 5;7(1):15.

- Chow KM, Chan CWH, Choi KC, White ID, Siu KY, Sin WH. A practice model of sexuality nursing care: a concept mapping approach. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2020 Aug 7;29(3):1663–73.

- Cook O, McIntyre M, Recoche K. Exploration of the role of specialist nurses in the care of women with gynaecological cancer: a systematic review. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2014 Sep 2;24(5-6):683–95. [CrossRef]

- Vadaparampil ST, Gwede CK, Meade C, Kelvin J, Reich RR, Reinecke J, et al. ENRICH: A promising oncology nurse training program to implement ASCO clinical practice guidelines on fertility for AYA cancer patients. Patient Education and Counseling. 2016 Nov;99(11):1907–10.

- de Vocht H, Hordern A, Notter J, van de Wiel H. Stepped Skills: A team approach towards communication about sexuality and intimacy in cancer and palliative care. The Australasian medical journal [Internet]. 2011 [cited 2023 Feb 5];4(11):610–9. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3562918.

- Suvaal I, Hummel SB, Mens JWM, Tuijnman-Raasveld CC, Roula Tsonaka, Velema LA, et al. Efficacy of a nurse-led sexual rehabilitation intervention for women with gynaecological cancers receiving radiotherapy: results of a randomised trial. British Journal of Cancer. 2024 Jul 3;131(5):808–19. [CrossRef]

- Carter J, Lacchetti C, Andersen BL, Barton DL, Bolte S, Damast S, et al. Interventions to Address Sexual Problems in People With Cancer: American Society of Clinical Oncology Clinical Practice Guideline Adaptation of Cancer Care Ontario Guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2018 Feb 10;36(5):492–511.

- National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN). (2023). NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Survivorship – Sexual Function (Male & Female). Version 1.2023. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/survivorship.pdf. Last assessed on 5 May 2023.

- Abu Sharour L, Suleiman, K, Yehya D, AL-Kaladeh M, Malak M, Subih M, et al. Nurses’ students attitutes toward death and caring fo rdying cancer patients during their treatment. EUROMEDITERRANEAN BIOMEDICAL JOURNAL. 2017 Nov 30;12(40):189–93.

- Al-Ghabeesh SH, Abu-Moghli F, Salsali M, Saleh M. Exploring sources of knowledge utilized in practice among Jordanian registered nurses. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice. 2012 May 29;19(5):no-no.

- Annerstedt CF, Glasdam S. Nurses’ attitudes towards support for and communication about sexual health –a qualitative study from the perspectives of oncological nurses. Journal of Clinical Nursing. 2019 Jun 4;28(19-20). [CrossRef]

- Chae YH, Song YO, Oh ST, Lee WH, Min YM, Kim HM, et al. Sexual Health Care Attitudes and Practices of Nurses Caring for Patients with Cancer. Asian Oncology Nursing. 2015;15(1):28. [CrossRef]

- Dyer K, das Nair R. Why Don’t Healthcare Professionals Talk About Sex? A Systematic Review of Recent Qualitative Studies Conducted in the United Kingdom. The Journal of Sexual Medicine [Internet]. 2013 Nov;10(11):2658–70. Available from: . [CrossRef]

- Matthew AG, McLeod D, Robinson JW, Walker L, Wassersug RJ, Elliott S, et al. Enhancing care: evaluating the impact of True North Sexual Health and Rehabilitation eTraining for healthcare providers working with prostate cancer patients and partners. Sexual Medicine. 2024 May 31;12(3). [CrossRef]

- Duimering A, Walker LM, Turner J, Andrews-Lepine E, Driga A, Ayume A, et al. Quality improvement in sexual health care for oncology patients: a Canadian multidisciplinary clinic experience. Supportive Care in Cancer. 2019 Aug 19;28(5):2195–203.

- Reese JB, Lepore SJ, Daly MB, Handorf E, Sorice KA, Porter LS, et al. A brief intervention to enhance breast cancer clinicians’ communication about sexual health: Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary outcomes. Psycho-Oncology. 2019 Mar 13;28(4):872–9.

- Matthew AG, Incze T, Stragapede E, Guirguis S, Neil-Sztramko SE, Elterman DS. Implementation of a sexual health clinic in an oncology setting: patient and provider perspectives. BMC Health Services Research. 2025 Jan 22;25(1). [CrossRef]

- Dreibelbis N, Dorne J. Addressing the Unmet Need of Sexual Health in Oncology Patients. Oncology Issues. 2024 Jun 1;39(3):15–23. [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).