1. Introduction

Disasters caused by natural hazards often lead to

significant economic and environmental problems in society. Thus, increasing

attention is placed on strengthening the “disaster resilience” of communities

at site specific, to improve a priori disaster risk reduction and expost

recovery.

To this direction, Eurocode 7 (EC7), the

(landslide) risk assessment approach and the factor of safety method are three

important geological-geotechnical tools that are used to estimate potential

failures and as a result take appropriate actions to avoid undesirable

consequences regarding the safety of the proposed civil engineering mitigation

measures. However, considering the concept of infrastructure resilience, all of

them (e.g., Eurocode 7, Risk Assessment, the factor of safety method) are

associated with some disadvantages mainly in its practical application, such

as:

Eurocode 7 (EN 1997) although it attempts to be

scientifically based, in several places it uses semi-empirical methods that

require “mechanical judgment” without clear instructions. This can lead to

different approaches to the same project by different engineers. In addition,

EC7 covers basic geotechnical problems (e.g., bearing capacity, subsidence),

but does not provide sufficient guidance for: (a) Complex soil conditions, (b)

Dynamic phenomena (earthquakes, liquefaction), (c) Deep stability problems

(e.g., large slopes, tunnels). Finally, EC7 does not fully incorporate the

geotechnical consequences of earthquakes (e.g., liquefaction, loss of bearing

capacity), which are critical in earthquake-prone regions such as Greece.

On the other hand, landslide risk assessment is

critical for natural disaster management, but risk-based approaches are only

appropriate for events that can be forecasted under usual threats. Furthermore,

the factor of safety method, even though it is an important approach for the

stability estimation in geological and geotechnical engineering, it lacks the

capability of considering the uncertainty of geomaterials mass, something that

results in making it hard to estimate the reliability of the civil engineering

landslide mitigation works [1].

Taking into consideration the above-mentioned, a

quantitative resilience assessment approach for geological and geotechnical

issues is needed. The word “resilience” was introduced to the engineering world

more than twenty years ago for research in the field of earthquakes [2]. To the author’s knowledge and according to

findings from other researchers, research in the resilience of geotechnical

field is lacking [3–5]. Furthermore, a

quantitative resilience assessment for geotechnical engineering issues is

missing [4]. Thus, to implement the concept of

resilience into practical applications in geological and geotechnical

engineering, a particular framework is necessary. To this end, this approach

can be achieved by presenting characteristic metrics and indicators to understand

the resilience of geotechnical assets. Thus, the concept of engineering

resilience is going to be presented through the implementation of technical

works taken place in a provincial road in the Region of Attica in Greece, where

many slope failures and subsidences, historically, have been occurred the last

twenty years and pose disorder to transportation normal functionality to the

broader area.

The case study is focused on Dekeleias Street

(named Provincial Road 3, under the jurisdiction of the Region of Attica, very

close to the National Motorway from Athens to Thessaloniki, adjacent to the

Chelidonous Stream, which is a tributary of the Kifissos River, one of the most

significant rivers in the Attica Region), where failures have occurred on the

road surface. In the examined area, the last two decades (e.g., 2005-2022),

slope failures, subsidences and undermining have taken place at the boundaries

of the road with the banks of the stream. These failures can be attributed to

surface erosion because of inadequate drainage of rainwater and to wider

instability of the adjacent slopes due to the erosive action of the stream (

Figure 1,

Figure 2).

The idea of facing those failures was based on

establishing a solid understanding of what contributes to the under-examination

road disaster resilience and how it can be measured. In the context of roadway

rehabilitation, geotechnical site investigation as well as stability and

rehabilitation studies of the roadway were conducted by the Directorate of

Technical Works (Central Section) of the Regional Authority of Attica.

As part of the roadway rehabilitation, including

investigating the stability of the slopes of the sections of the road in

question, topographic survey, geotechnical survey, geotechnical study, study of

the stability of the roadway, study of the stabilization & rehabilitation

and traffic study were authorized by Directorate of Technical Works of the

Region of Attica.

In the present study, the hazard of the existing

condition of the stream slopes and their adjacent District Road 3 is confirmed

using the Rock Engineering System methodology. The specific methodology is

presented, and the slope failure parameters that contribute to the instability

of the study area are briefly described. Its application led to the calculation

of the slope instability index, which confirms the results obtained from the

execution of the geotechnical investigation and study carried out, leading to

specific types of technical road support works. To address the erosive

mechanisms, it was proposed to construct pile walls made of intersecting piles

of different diameters and walls on piles anchored, due to the significant

resistance heights obtained, with a passive anchoring system of deadman type [6].

Considering the above-mentioned, this paper aims to

discuss approaches that improve the understanding of engineering resilience to

landslide mitigation measures as well as to propose tools that aim to estimate

disaster resilience.

Thus, the structure of the paper is as follows:

firstly, a description of the geology and geomorphology of the area of interest

as well as the presentation of the geological-geotechnical study and

construction works is briefly provided. Secondly, in Material and Methods

Section, the terms of the Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response framework that

are associated with engineering resilience are presented. In addition, the Rock

Engineering System semi-quantitative methodology is described with the intention

to prove the pre-existing potential slope failure of the examined road, by

estimating the landslide instability index through a matrix. In the Section of

Results and Discussion, those terms of resilience are integrated with the steps

of the design and construction process of the project, and an alternative

expression of the above-mentioned matrix is used to apply resilience. Finally,

the paper closes with the Conclusions.

1.1. Geological and Geotechnical Setting of the Study Area

The study area is in the western foothills of the

Penteli Mountain, specifically east of the Kifissos River and adjacent to the

Chelidonous Stream (

Figure 3). The

morphological topography of the area is characterized by a gentle, flat terrain

with very gentle slopes. The wider area geologically consists of Neogene and

Upper Miocene formations. The road section under study runs through the

Kifissos Lake formations, according to the geological map of IGME (e.g., Greek

Geological Research Institute), geological sheet of Kifissia (1.50.000 scale).

To investigate the nature of the formations along

the failures of the problematic section of Dekeleias Road, four sample

boreholes with a total depth of 65 meters and field and laboratory tests were

carried out. The field work took place in March 2018 (

Figure 4a, b).

1.2. Evaluation of Geotechnical Investigations

Considering the results of the geotechnical

investigation, the field and laboratory tests and all available data, the

following sections with uniform geotechnical characteristics were distinguished

[6]: (a) modern artificial embankments, (b)

alluvial deposits and (c) lake and pond formations. An aquifer level was

detected in all the executed boreholes. In two boreholes, the water level

corresponded with the bed of the Chelidonous stream, which passes a short

distance away. In the other two boreholes, the phenomenon of artesianism

occurred. Based on the evaluation of the abovementioned formations,

geotechnical measures were proposed for design parameters, range and

characteristic value for each of them, and geotechnical simulations were

prepared for the areas under consideration. After evaluating the findings of

the geotechnical investigation and considering the geometrical characteristics

of the areas in which the geotechnical problems were identified, the study

areas were divided into subareas such as A, B, C and D (

Figure 5). The division of the areas also

considered the morphology of the road slopes, the geological and geotechnical

conditions, the distance of the road from the Chelidonous stream and the

failure mechanisms evaluated per area.

1.3. Geotechnical Study—Description of the Constructed Technical Works

The proposed solution is an example of targeted

resilience strengthening investment and action. To address the erosive

mechanisms, it was proposed to construct pile walls made of intersecting piles

of different diameters and walls on piles anchored, due to the significant

resistance heights obtained, with a passive anchoring system of deadman type [6]. To avoid soil erosion between the reinforced

piles on the outer side of the retaining project, unreinforced piles are

provided between them that reached a depth greater than that of the existing

stream bed [9]. Area A was examined separately

from the other three areas B, C and D, as it is located at a great distance

from them and was divided into subareas A1, A2 and A3 to consider the

variations in the morphological characteristics of the road slopes and failure

mechanisms. Analyses of the internal failure or excessive deformation of the

structure (STR) and failure or excessive deformation in the ground (GEO type

limit states according to EN 1997-1) were carried out on critical control

cross-sections covering the most adverse conditions per study area. The results

showed that the lower limits of the safety factors defined by the relevant

regulations are covered [6]. The selected

solutions are summarized as follows.

Area A

In Area A, the main contributing factor to the

failure mechanism is estimated to be, based on the failure morphology, the flow

of the stream as the stream bed approaches the roadway slope (Figure 5). Area A was divided into three

subareas (A1, A2, A3). Subarea A1 starts after the turn from the Athens Lamia

Highway (Lainopoulos location) and extends 8.50 m to the west. To address the

erosion mechanisms in subarea A1, it was decided to construct a pile wall with

interlocking piles Ø1.00 m with the reinforced piles having an axial spacing of

1.7 m. Subarea A2 starts from the end of area A1 and extends 32.90 m to the

west. In this area, significant undermining has occurred on the existing road

with the crown of the existing steep slopes bounded within the road zone. To

address the erosion mechanisms, anchor walls 3.0 m and 5.5 m high constructed

founded on interlocking piles of Ø1.00 m diameter at 1.7 m intervals. In this

section, the retaining elements (piles, retaining walls) needed to be anchored.

Subarea A3 starts from the end of area A2 and extends 5.10 m towards the west.

To address the erosive mechanisms in area A3, it was decided to construct a

pile wall with intersecting Ø1.00 m piles with the reinforced piles to have an

axial spacing of 1.7 m (

Figure 6a, b).

Areas B, C, D

The main factor causing the failure mechanism in

areas B to D is the flow of the Chelidonous stream, which causes erosion at the

foot of the road slopes (Figure 5). The

erosion of the foot and the gradual change in slope gradient to steeper

gradients cause generalized slope stability problems affecting the existing

Dekeleias Road in the form of soil movement and subsidence of the roadway on

the stream side. It should be noted that in areas where the stream, due to its

natural flow, is near the Dekeleias road, such as in areas B and D, the foot of

the road slopes is also the boundary of the streambed, and as a result, the

instability problems were more pronounced. In area C, the stream moved away,

and the erosion problems appeared milder [6].

A significant contribution to the occurrence of

failures was also made by surface stormwater runoff, which was uncontrolled

through the natural slope of the road due to the absence of a drainage system.

In addition, the underground aquifer, which in some places took the form of

artesianization, had an adverse effect on the overall stability of the slopes.

Based on the above, area B was divided into two (2) subareas, B1 and B2, and

area D was divided into five (5) subareas, D1 to D5, to consider the variations

in the morphological characteristics of the road slopes and the failure

mechanisms.

Area C was treated as an area with uniform

morphological and geotechnical characteristics. Subarea B1 started after the

technical culvert which has been constructed after the church Zoodochos Pigi to

drain the stream water under Dekeleias Street from upstream to downstream and

extends for 10.10 m to west. The failures on the roadway in this area were due

to the erosion of the slopes caused by the flow of water exiting the culvert,

as well as the failure to manage the surface runoff of stormwater runoff. Rainwater

collected on the upstream side of the road through the culvert flowed

uncontrolled through the culvert into the bed of the natural stream, causing

erosion of the existing adjacent slopes. In addition, the uncontrolled surface

flow of rainwater on the road surface caused localized undermining of the road.

(Figure 2). To address the erosive

mechanisms in subarea B1, a pile wall was constructed with interlocking Ø1.20 m

piles, with the reinforced piles having an axial spacing of 2.0 m. Subarea B2

started from the end of area B1 and extended 24.20 m to the west. In this area,

the main contributors to the failure mechanism were estimated to be stream flow

and groundwater, while surface water flow appeared to have little or no

contribution based on the morphology of failures. As a result, localized soil

instabilities and subsidence occurred in Area B2, affecting the existing

Dekeleias Road, but on a smaller scale than the adjacent Area B1. To address

the erosive mechanisms in subarea B2, a pile wall with Ø1.00 m piles was

constructed at an axial spacing of 1.7 m.

Area C started from the end of area B2 and extended

to 28.20 m to the west. In area C, it was estimated that the road slopes were

in a state of limit equilibrium. The main factor contributing to their

destabilization mechanism was estimated to be the erosive action of the stream.

The local soil instabilities and subsidence that occurred immediately were

small in scale due to the removal of the natural flow of the stream from the

road slope, but works were needed to contain the erosive mechanisms to protect the

road from future larger scale failures. To address the erosive mechanisms in

Area C, it was decided to construct a pile wall with Ø1.00 m piles at an axial

spacing of 2.3 m.

Area D is divided into five (5) subareas, D1 to D5,

as mentioned above, starting from the end of Area C and extending approximately

87.00 m in length to the west, numbered sequentially.

In subareas D1 to D5, the main contributing factor

to the failure mechanism was estimated to be the flow of the stream as the

stream bed approached the road slope. As a result of this action, localized

soil instabilities and subsidence occur in areas D1 and D5 in the lower portion

of the roadway slope, affecting the existing Dekeleias Road. Similarly, in

areas D2, D3 and D4, local soil instabilities and subsidence occurred, which

affected not only the lower part of the slope but also the upper part of the slope

in contact with the existing Dekeleias Road. To address the erosive mechanisms

in areas D1 to D5, interlocking piles Ø1.00 m and Ø1.20 m were constructed with

reinforced piles having axial spacings of 1.7 m and 2.0 m, respectively. In

subareas D2, D3 and D4, retaining walls of 1.5 m to 3.0 m high founded on the

interlocking piles are also planned. It should be noted that in all areas and

subareas, the project was decided upon, and then the diameter of the piles and

their axial spacing were calculated.

The geotechnical study was fulfilled in January

2019, whereas the stabilization work started in September 2020 and accomplished

in September of 2023. In

Figure 7 (a–g),

characteristic views from the construction phase of areas B to D are depicted.

In the following section, the above-described

construction phase will be integrated into an engineering resilience framework.

2. Materials and Methods

The term “resilience” originated from the Latin

word “resiliere” [1], while Holling [10], expressed that resilience is the measure of

the persistence of systems and of their ability to absorb change and

disturbance.

In terms of hazards and disasters, even though

resilience has been part of the research literature for decades, the term first

discussed among national governments in 2005 with the adoption of The Hyogo

Framework for Action by 168 members of the United Nations to ensure that

reducing risks to disasters and building resilience to disasters became

priorities for governments and local communities. Disaster resilience has been

described as a process, an outcome, or both, and as a term that can embrace

inputs from engineering and the physical, social, and economic sciences [11].

In the field of civil engineering projects,

resilience is the ability of a system to withstand disruptions and continue to

function by rapidly recovering from and adapting to the disruptions [12]. The necessity of integrating resilience into

infrastructure is getting more urgent nowadays since the frequency of natural

hazards increases [3]. In the following, the

concept of resilience will be developed through the description of the process

of the design and implementation of the civil engineering works of the selected

case study.

2.1. Engineering Resilience

The meaning of resilience in civil engineering

projects is associated to the preparedness and response of a system against

catastrophic events. Preparedness is basically related to the ability of

proactively mitigating the effects of disastrous events by providing adequate

resources and designing strategies prior to the disruption [3].

The term “response” includes the meanings of

“absorption” and “recovery”, where they both are expected after the event of

disruption [13,14]. Absorption is the

immediate response of an infrastructure system in which the system withstands

the disruption, and recovery is the organizational efforts to rapidly repair

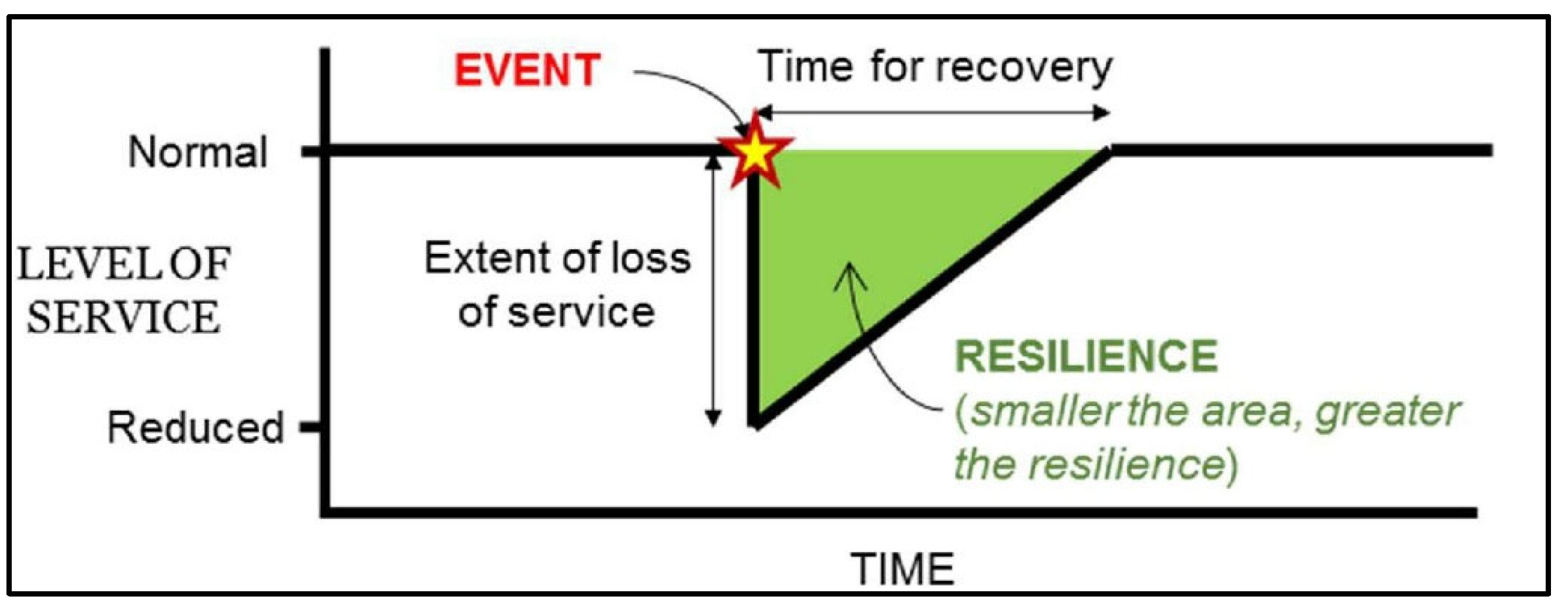

the damaged system, and the consequential effects propagated to other systems [3]. The above-mentioned terminology can be depicted

through a graphical curve which illustrates how an engineering system’s

performance changes over time considering a disruptive episode [15].

Figure 8

shows a characteristic degradation and recovery of system functionality over

time.

Absorption of shocks is reflected by the

degradation of the system functionality at the event of disruption (from time td

to ta). The recovery efforts can be initiated immediately by

post-disruption; however, the system functionality can be unchanged for a

certain period of time (from time ta to tr) until

adequate resources are collected and response strategies are organized (this is

the assessment stage). Finally, it is expected that the system functionality

recovers to an acceptable level for its normal operation (from time tr

to tf).

An alternative scheme of the resilience framework

in the transportation network, such as in our case study, is given below (Figure 8a). Crucial issues in this figure are

the metrics of the reduced level of service and the time required to restore

that service [16].

Bruneau et al. [17]

described further the meaning of resilience by defining four properties:

robustness, rapidity, resourcefulness, and redundancy. Robustness is the

ability of technical works to resist the impact of hazard events, such as

landslides, floods, etc. Rapidity is associated with how quickly the

infrastructure recovers after an event, which depends on the available

resources and the damage level [5].

Resourcefulness is the capacity to identify problems, establish priorities, and

mobilize resources (i.e., monetary, physical, technological, and informational

resources). During the assessment stage ta to tr,

resourcefulness can contribute to lessening the time of assessment.

Furthermore, resourcefulness can contribute to developing mitigation measures

for disaster prevention and contribute to the recovery process [3]. For example, sufficient monetary and

informational resources reduce the time in identifying damages or vulnerability

of the system. Redundancy indicates the extent to which existing elements or

systems are substitutable. Redundancy and resourcefulness are the means to

improve the resilience of an infrastructure. For example, the resilience of a

road network (as it is for the examined case study) can be improved by ensuring

that alternative routes can be used [18],

during the restoration of deteriorated components [5]).

The same researcher [17]

further categorized resilience within the engineering discipline into different

dimensions such as technical, organizational, environmental [3], social, and economic. Technical dimension

includes all the technological issues related to the construction [19]; organization dimension includes all the

management activities and response to emergencies [19];

environmental dimension is associated with the influence of the constructed

technical works on the surrounding environment (slopes, stream, fauna and

flora) and the increased carbon dioxide emissions due to the prolonged time

travel after the slope failures and the subsequent closure of the road; social

dimension considers the impacts of failure of infrastructure system to social

groups; and economic dimension refers to economic losses, both direct and

indirect, because of the occurrence of the disaster, as well as the subsequent

rehabilitation [19]. Based on the

above-mentioned, a resilient system should be characterized by the following [4]: reduced failure probabilities, reduced

consequences from failures, reduced time to recovery.

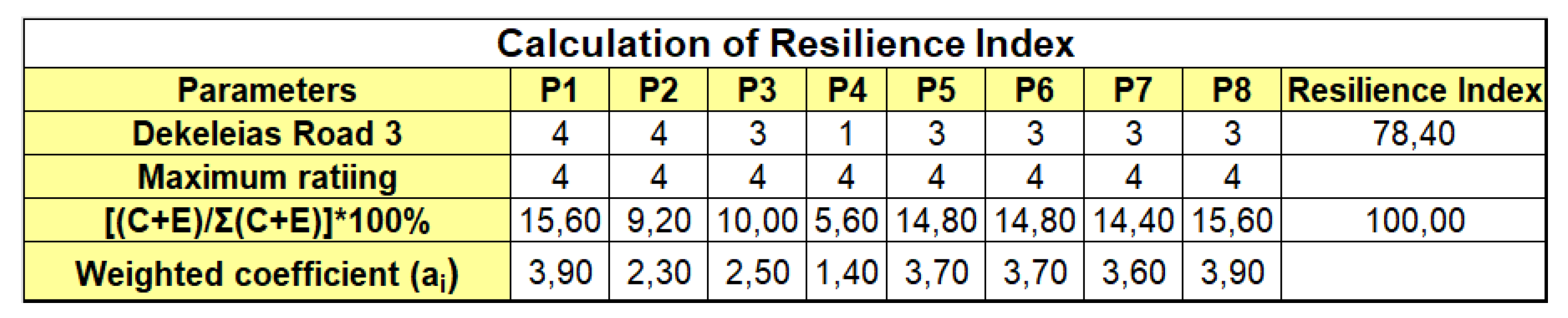

2.2. DPSIR Framework

DPSIR (Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response)

framework has been used as a resilience assessment framework implemented to

geotechnical infrastructure (

Figure 9).

“Drivers” and “pressures” describe the hazard

scenarios applied to a civil engineering project. For example, slopes and

bridge foundation (as in the examined case study), are crucial factors in

transportation networks. Therefore, the drivers affect the users’ travel

behavior and business logistics [3].

As a result, the driving forces result in

pressures, which can be identified as the effect of climate change or funding

constraints.

“States” includes the robustness, rapidity,

resourcefulness and redundancy of the examined infrastructure [3]. The states indicate the metrics that represent

the resilience of a civil engineering project. An example of this will be

presented in the following section by quantifying the resilience through a

matrix table and an index.

The technical, economic, organizational,

environmental and social effects can be described by the impacts [20]. Last, disaster management and decision-making

are associated with the term of response [3],

which will be described by mentioning the series of civil engineering

construction and bureaucratic procedure steps that needed for the restoration

of the damaged road segment.

Τhe above-mentioned terms are going to be

integrated into the description of Provincial Road 3’s restoration.

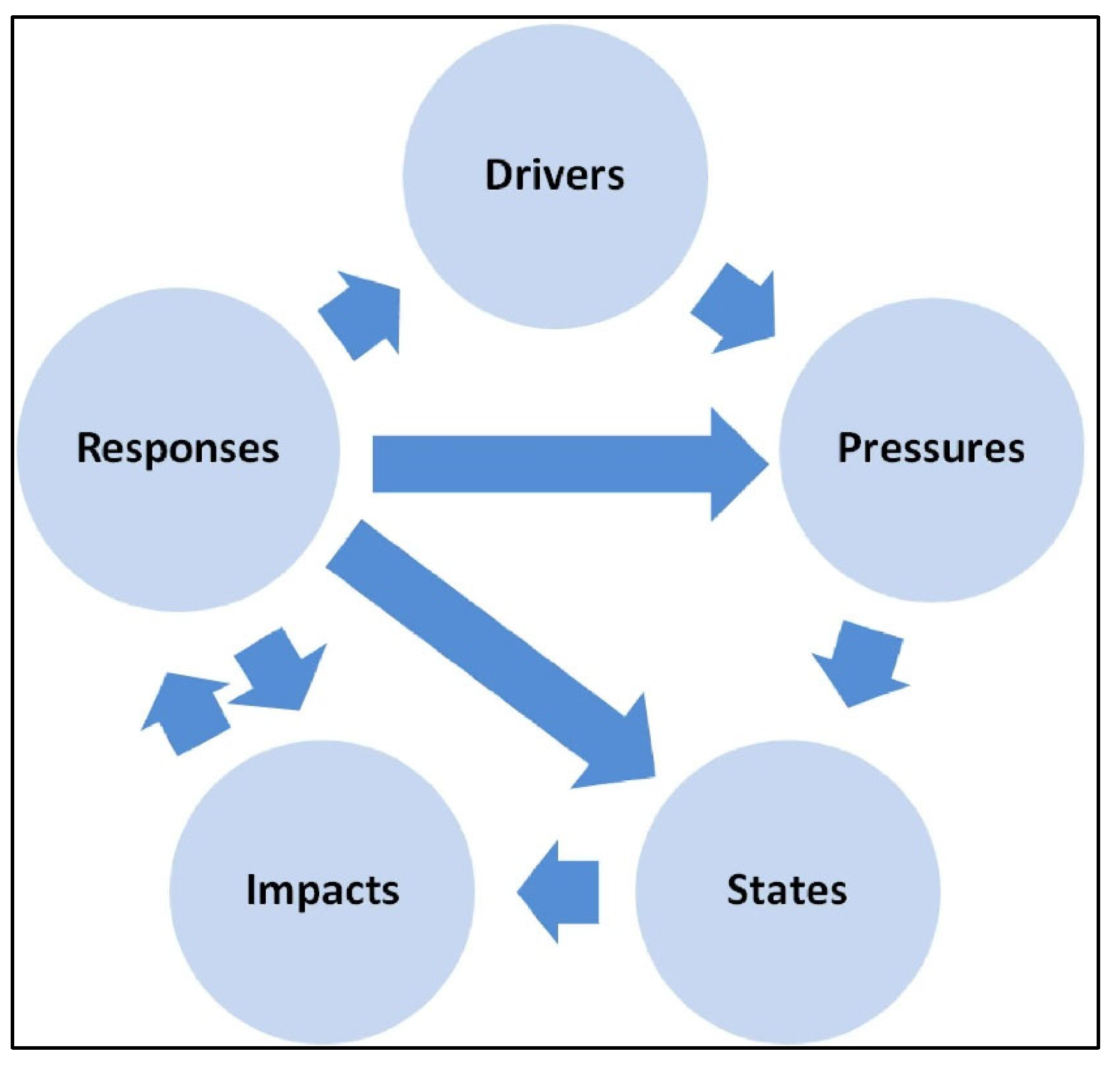

2.3. A Semi-Quantitative Methodology [Rock Engineering System (RES)]

To quantify the response of geotechnical

environment in terms of their limit states as well as to confirm the hazard of

the geological-geotechnical condition of the slopes of the study area before

the restoration technical works, the Rock Engineering System (RES) methodology

was used [21]. This methodology is mainly

based on the correlation of mechanisms between landslide parameters through a

matrix table and uses parameters that can potentially be identified during the

preparation phase of a preliminary, final or implementation study of an

engineering project. The scope of using RES is to estimate the landslide

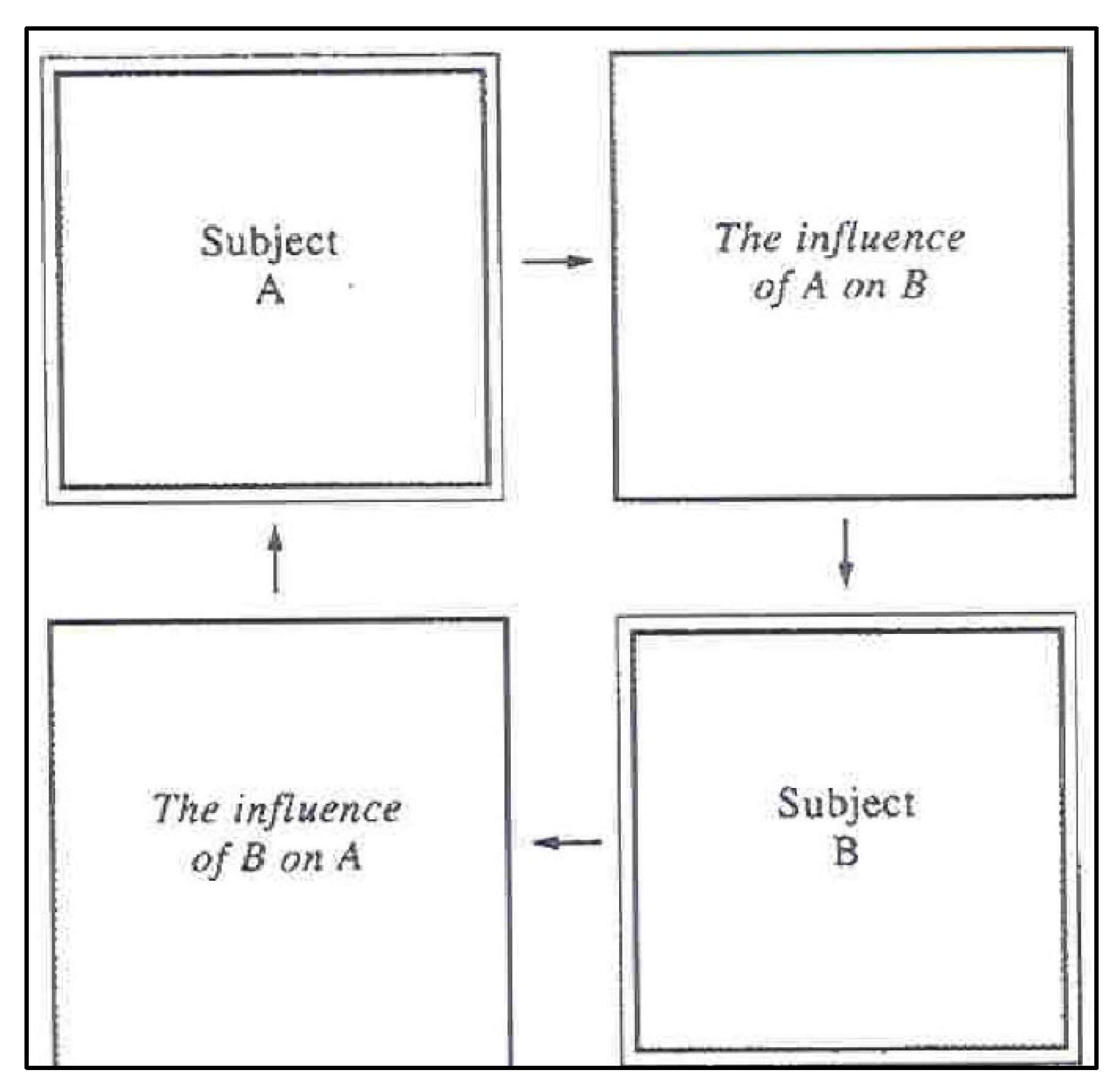

instability index. The simplest matrix is one that illustrates the effect of

parameter A on parameter B and vice versa the effect of B on A (

Figure 10).

The basic principle of the matrix—table is to place

the parameters studied for the occurrence of failures along a principal

diagonal and to study the interactions of the specific parameters outside the

principal diagonal (

Figure 11), through a

cause—effect linkage.

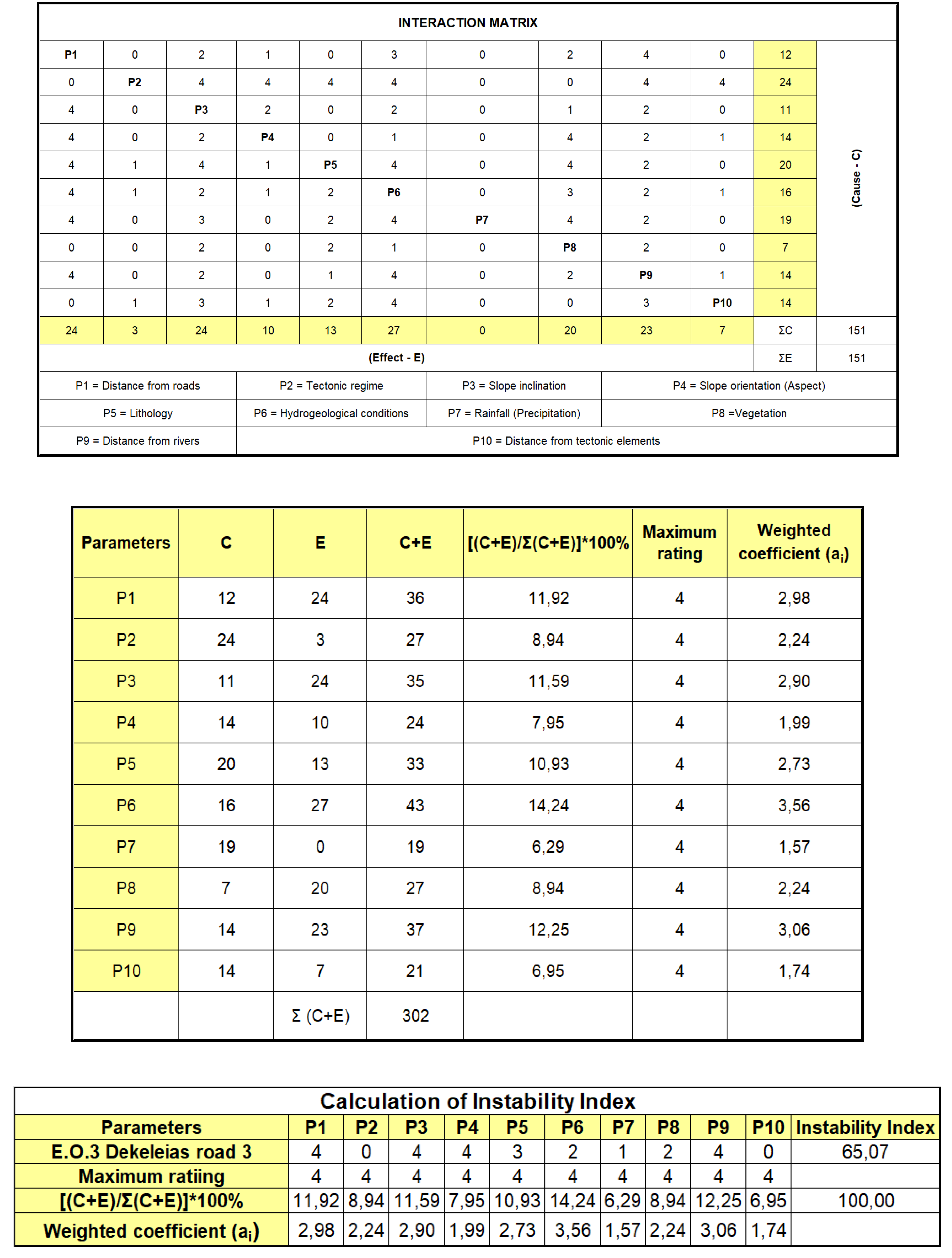

The concept of the RES methodology is an objective

approach that allows the use of all data relevant to a technical project, to

match the specific methodology with the conditions on the ground. This is

achieved by a series of actions, which are the following: (a) selection and

rating of the parameters associated with the slope failure, (b) construction of

a matrix in which the selected parameters are placed on the main diagonal of

the matrix and their binary interactions located outside the main diagonal are

studied, (c) analysis of the binary interactions between the parameters, (d)

coding the meaning of each interaction [For the purpose of the present work, a

range of possible interactivity from 0 to 4, corresponding to `none’ (coded 0—most

stable conditions), `weak’ (coded 1), `medium’ (coded 2), `strong’ (coded 3)

and `critical’ interactions (coded 4—most favourable condition for slope

failure) is adopted], (e) calculation of the weighting coefficient of each

parameter, and (f) estimation of the instability index by using the following

equation: Ii=Σai x Pij, where i refers to parameters (from 1 to 10), j refers

to the examined slope and ai is the weighting coefficient of each parameter

given by the formula: ai=1/4 * [(C+E)/(ΣiC+ ΣiE)]%, scaled to the maximum

rating of Pij (maximum value=4). Pij is the rating value assigned to the

different categories of each parameter’s separation which also fits better to

the conditions related to the parameter in question regarding the examined

slope failure.

The instability index is an expression of the inherent potential instability of the slope, where the maximum value of the index is 100 and refers to the most unfavourable conditions. In the following section, the abovementioned steps are analytically presented and discussed.

2.3.1. Selection and Rating of Landslide Parameters

At the site considered, RES methodology was implemented, and ten landslide parameters associated with the specific failure were selected [

8,

22,

23]. The selection of the appropriate parameters was based not only on valuable knowledge from literature and mainly on the overall experience gained from the study of landslide phenomena in Greek territory and additionally from case studies from all over the world but also on their affinity with landslide occurrence in the case study area. Ten parameters were selected as independent controlling factors for the landslide occurrence and each factor was classified into 5 classes. These factors, which were utilized for the RES methodology, were:

(i) Human activity (distance from roads): The shorter the distance of a slope from a linear axis (e.g., road), the more likely (under certain conditions) it is that the slope will fail. In the area under consideration, the distance of slopes from provincial road 3 (Dekeleias Road) is less than 50 m.

(ii) Tectonic regime: In the area under consideration, the tectonic regime is weak, i.e., associated with the near absence of significant tectonic events.

(iii) Slope inclination: The slope gradient is an important parameter in considering the initiation of a landslide, and in most landslide studies, it is considered the main initiating factor or triggering parameter. At the studied site, due to the steep depositional slope (>45°), the parameter was calibrated with a value of 4.

(iv) Slope orientation: Slope orientation is influenced by solar radiation, wind and precipitation and thus strongly influences hydrological processes through evapotranspiration. It influences sedimentation processes (formation of a weathering mantle), the moisture content of the soil, vegetation and root growth and consequently leads to a reduction in soil strength. Based on the above, the parameter was given a value of 4 (0°–45°, 135°–225°).

(v) Lithology: From investigations carried out in the Greek territory, it is proven that the lithological composition and the strong variation in the lithostratigraphic structure, which results in a sequence of formations with completely different geotechnical characteristics, have a significant influence on the occurrence of landslides. At the location under consideration for the Neogene and Quaternary formations, a value of 3 is taken for this parameter.

(vi) Hydrogeological conditions: The presence of water is most often decisive for the final behavior (failure or not) of the geological materials on which a technical project is based. In the study area, because the formations involved are alluvial deposits over a Neogene basement, the parameter “hydrogeological conditions” was calibrated with a value of 2.

(vii) Rainfall (Precipitation): Rainfall is one of the most important external factors that contributes to the occurrence of landslides and mainly triggers movement. It has been observed that during periods of increased rainfall, the frequency of landslides is high since it causes a change in pore water and increased hydrostatic pressures. In addition, weathering processes (chemical and mechanical) are triggered, along with erosion caused on a slope by surface water. In the study area, the phenomenon of failures is dynamic, and the main reason for this is the intense and prolonged rainfall that has taken place there over time (especially during the period October 2018–February 2019). For the case study, the average annual rainfall from the measuring adjacent meteorological station in Tatoi is 450 mm. Due to the above, the parameter was calibrated with a value of (1).

(viii) Vegetation: Vegetation plays an important role in controlling soil erosion and can help stabilize a slope through mechanical resistance in the subsoil. It provides a protective layer on the land surface and regulates the transport of water from the atmosphere to the land surface, soil and underlying rocks. In general, slope stability is very sensitive to changes in vegetation cover. Considering the standard criteria used by the Greek Ministry of Rural Development to evaluate different sites and field observations, the category “moderate vegetation” characterizes the examined area with a score of 2.

(ix) Distance from streams: Research has shown a close spatial relationship between the occurrence of landslides and the presence of streams. One of the causes of potential changes in the geometry of a stream slope is the erosion that the stream contributes to removing the support of the adjacent slope. This removal is one of the most common factors in causing landslides. The rate of lateral erosion of a stream is related to its depth, the erodibility of its geologic material, and the velocity of its flow. However, the proximity of the slopes to the stream beds also contributes to the degradation of the geomechanically characteristics of the geological materials that make up the slopes. It has been found that as the distance from streams increases, the frequency of landslides generally decreases. In the study area, the distance of the slope from the stream is almost negligible (less than 50 m) and is therefore rated with a maximum value of 4 (critical interaction).

(x) Distance from tectonic features: It is generally known that the presence of a fault zone due to the action of tectonic forces from a geomechanically point of view: (a) drastically reduces the cohesion of the rock in a zone along the fault and (b) affects the hydrogeological regime of the wider area either by increasing the permeability in the aforementioned zone and creating a selective groundwater drainage axis or by decreasing the permeability, which leads to an influence on the geomechanically behavior of the formations affected by the aforementioned fault elements. The study area is located approximately 3-4 km east of the nearest active fault [

6]. Therefore, it does not directly affect the study area (rating: 0).

The rating and interpretation of the selected parameters (

Table 1) was carried out based on the technical-geological data of the slopes of the study area, considering data from research on landslides in Greece [

8,

22,

23]. In

Table 1, the selected parameters are presented and their ratings representing the local geological and geotechnical conditions of the study area are highlighted.

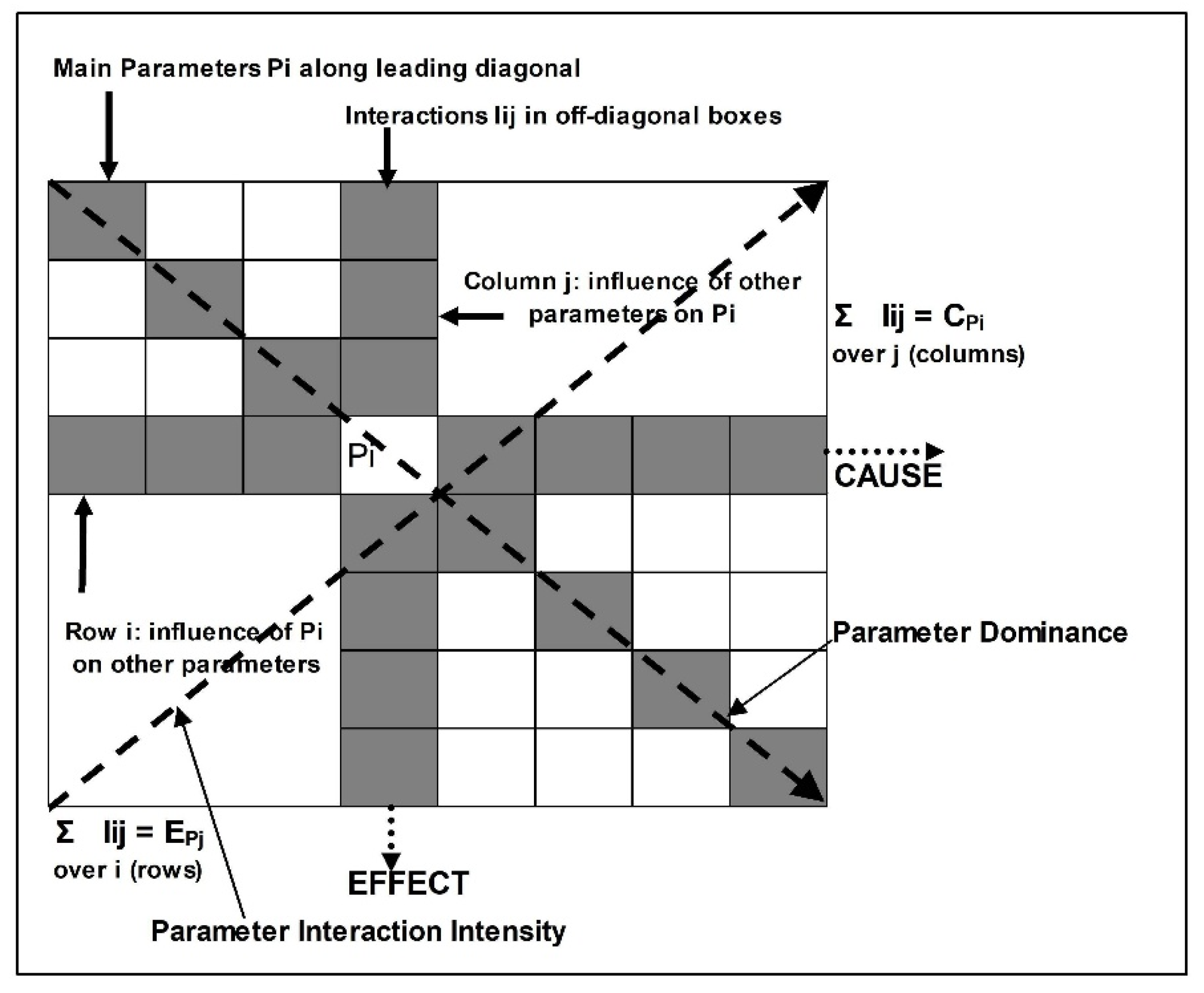

2.3.2. Construction of the RES Matrix—Calculation of the Landslide Instability Index

According to the methodology analyzed in subsection 2.3, the construction of the RES matrix, the estimation of weighted coefficients, and the calculation of the instability index are presented (

Table 2). Regarding the way the matrix has been constructed, a characteristic indicative interaction among the selected landslide parameters in

Table 2 is described (by assigning the appropriate coding value) in detail below. For example, the tectonic regime of the case study area has a critical influence on lithology, as represented by the value 4. On the contrary, concerning the influence of lithology on tectonic regime, there is a weak interaction (rating equal to 1). For better understanding of the interactions between the selected parameters, the reader is advised to read the following references [

22,

23].

Based on the geological and geotechnical data of the specific study area, the existing information was decoded (quantified), and through the RES methodology, the instability index was calculated and found to be equal to I=65.07. The instability index in this study is related to the categorization of landslide susceptibility proposed by Brabb [

24], that is, to the average of the percentage of the area under failure to the total area of interest through lithological or geological units (

Table 3).

According to Table’s 3 categorization, the instability index for the examined Dekeleias road and its adjacent Chelidonous stream slopes confirms the failures that have already occurred on this road [Landslide with Relative Susceptibility Numbers or RSN (Relative Susceptibility Numbers): L= 54-70%].

3. Results

This section will apply the concepts of engineering resilience through the description of a geotechnical project (e.g., case study of the Provincial Road 3): from the identification of the initial problem and the site investigation to the design, financing and implementation of the technical works. At the same time, the response to extraordinary events that occurred during the construction of the works (such as: a. the installation of drainage system wells due to the all of the sudden occurrence of water on the surrounded slopes during the construction stage of B to D area, b. the subsidence-collapse of part of the bridge—culvert near the Church of Zoodochos Pigi, c. the preparation of a supplementary—additional study after the agreement of a supplementary contract regarding the restoration of the previously mentioned damaged of bridge—culvert, d. the launch of the CONVID-19 pandemic period that caused a significant delay in the beginning of the project procedures (e.g., delays due to the initially general traffic ban from the Greek Government) will be commented on.

To begin with, over the last twenty years, part (e.g., with a length of about 300m and especially in the section adjacent to the Kifissos River) of the Provincial Road 3 faced problems of both slope failures and subsidence, because of the severe bad weather phenomena, the resulting erosion and its proximity to the adjacent stream of Chelidonous. Thus, due to:

1) The phenomenon of the erosion of the slopes of the examined road on the side of the Chelidonous stream was dynamic and had caused, owing to heavy rains on October and December of 2018, new significant problems in the roadway and its slope (conditions of undermining of the road) compared to the time of the announcement of the study (three years ago),

2) The failure to manage the stormwater from the road and the stream, a failure of the existing retaining wall and the parallel exposure of the public utility networks had already occurred. In addition, the above phenomena were exacerbated by the absence of drainage of stormwater from the road for the safe drainage of rainwater,

3) The consequence of the previous finding was the unsafe passage of vehicles and pedestrians due to increased danger and the clearly continuously deteriorating existing condition of the roadway and the parts of the slopes supporting it,

Provincial Road 3 had poor resilience. Therefore, a need for mitigation measures to enhance the resilience of the road was necessary and geotechnical engineering needed to play a significant role in this response [

16]. The Directorate of Technical Works (Central Section) of the Region of Attica decided in 2016 to definitively address the problem by awarding a topographic survey and geological—geotechnical research and study to a specialized consulting firm after an open tender. The study was carried out during the two-year period 2018-2019, which proposed specific technical works to remove the existing risk. After a significant period had elapsed during which the urgency of the issue had to be clarified and the source of funding sought, the Directorate of Technical Works of the Regional Authority of Attica launched an open tender where the final bidder was awarded the implementation of the technical works proposed by the geotechnical study. Construction work started in March 2020 (start of CONVID-19 pandemia) and was successfully completed in spring 2023. To translate the above actions into the engineering resilience concept, the following steps were executed:

According to the terminology described in

Section 3.1 (Engineering Resilience), the ability of the existing infrastructure of the examined road before the reconstruction of the Provincial Road was weak (inadequate robustness and technical dimension) and lacked the geotechnical and geological characteristics that could resist erosion and undermining of the road due to heavy rainfall and inadequate drainage system. As a result, the concept of rapidity was raised, meaning how quickly the infrastructure recovers after an event. Thus, judging by the damage level and the available resources, the rapidity of the reconstruction process was moderate (organization dimension), taking into consideration the identification of the emerging geotechnical problems, the difficulties of establishing priorities and mobilizing monetary resources (Resourcefulness stage), not to mention the constraints in terms of budget priorities. To this end, some extra problems raised, such as the period of COVID-19 pandemic which was initiated just at the beginning of the construction stage and for a period of three (3) months no construction works could be done due to traffic curfew from the Greek Government. Furthermore, during the construction phase of areas B to D, between areas A and B (at the end of area B) of the road and specifically at the height of the Church of Zoodochos Pigi, further erosion of the roadway slope was created (of 21.80 m), which manifested itself in the form of collapse of part of the existing retaining wall and with a sliding volume of soil. The new erosion of the roadway slope was due to the heavy rainfall of recent years, has been dynamic and has progressed in time to the present day. To restore the traffic on the road and to limit the future extension of the phenomenon, it was considered imperative to modify the original design, to include additional works to support the above described 21.80 m long section. As a result, this led to additional geotechnical study and extra budget being provided.

As far as redundancy it concerned, which indicates the extent to which existing elements or systems are substitutable, during the reconstruction face of areas A to D, alternative transportation route was used (social dimension) resulting in the closure of the examined segment of the Provincial Road 3 for approximately three years. Lastly, speaking about the economic dimension (direct economic losses because of the above-mentioned phenomena), the total amount of the reconstruction stage was equal to the amount of two (2) million euros approximately, without including in this amount of money the indirect costs from the closure of the particular segment of the Provincial Road 3.

Referring to the DPSIR (Driver-Pressure-State-Impact-Response) framework, slopes and bridge foundation (e.g., drivers), were important factors in the transportation network of the examined area, since they affected the users’ travel behavior and business logistics [

3] and consequently resulted in pressures, which can be identified as the effect of climate change or funding constraints. The robustness, rapidity, resourcefulness and redundancy of the examined infrastructure are associated with the term “States”, which indicate metrics that represent the resilience of a civil engineering project. The technical, economic, environmental and social effects can be described by the impacts. Last, disaster management and decision-making are associated with the term of response [

3], which described by mentioning the series of civil engineering construction steps that needed for the restoration of the damaged area.

3.1. Quantitative Framework to Evaluate Resilience

To evaluate the effectiveness of the above-described mitigation measures for improving the resilience of the geological—geotechnical environment of the examined case study, a (resilience) matrix approach [from a different perspective that the previous described (RES)] has been developed, which includes both quantitative and qualitative data under the context of the resilience process.

For the construction of this matrix, it is important to consider not only the engineering resilience of a civil engineering project in the existence of a disruptive event (e.g., flood, landslide, etc.) but also the cascading impacts of it, such as what impact has to the people (social), the surrounding environment and the economy [

20].

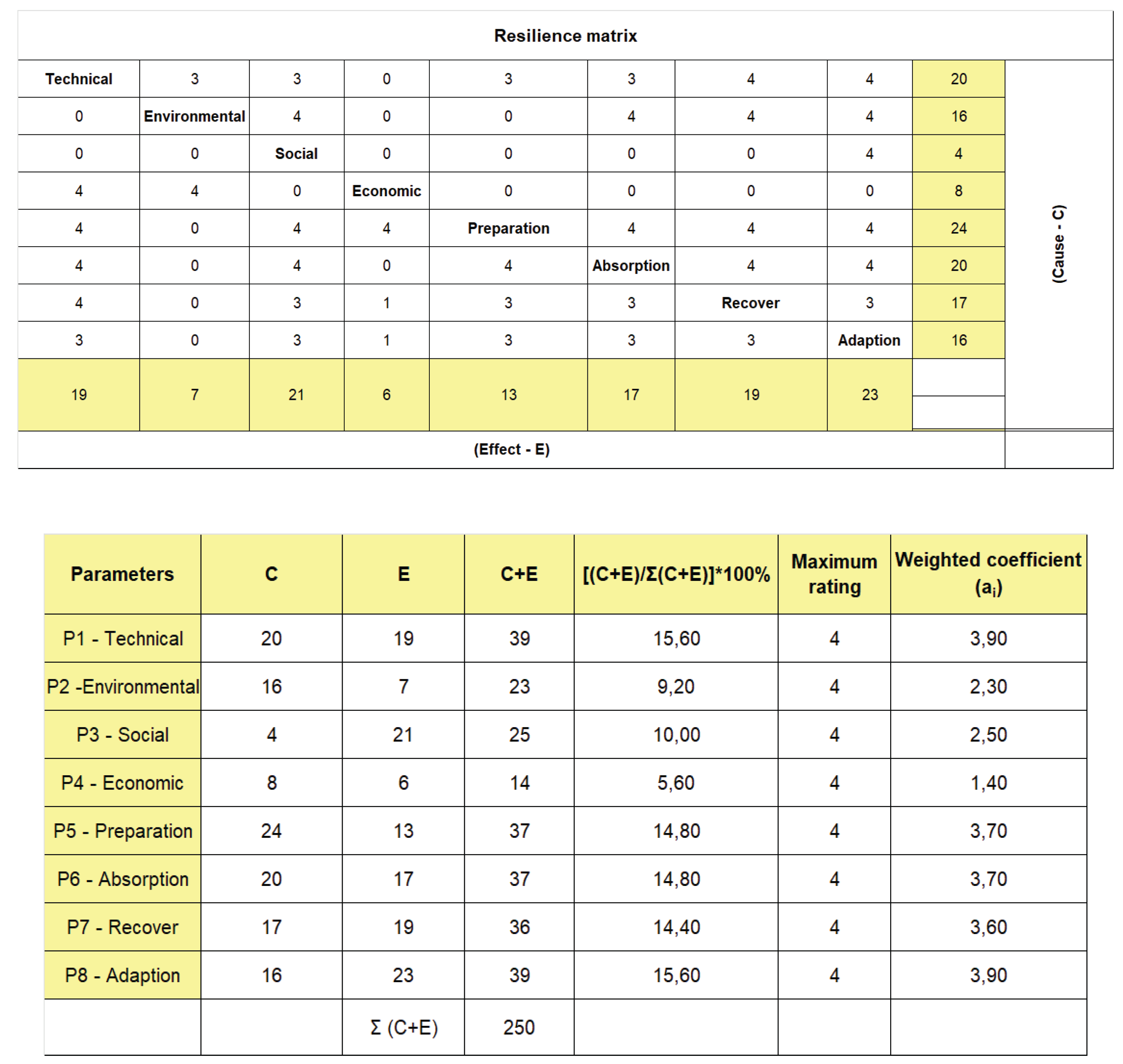

To this direction, the Resilience Matrix (RM) consists of an 8 x 8 matrix (

Table 4), where the columns describe the most important parameters of any system (e.g., technical, environmental, social and economic) and the rows depict the steps of a disruptive event (preparation, absorption, recover, adaptation), [

25]. The aim of technical resilience is to minimize the probability of failure in case of the existence of a severe meteorological or earthquake event [

20]. On the other hand, social, environmental or economic resilience can be the (derivative) impacts (e.g., positive or negative, overestimated or underestimated respectively) of technical resilience [

20].

In order to perform a resilience assessment and understand an adverse event (e.g., the consequences of a heavy rain on to a road functionality), the following steps should be taken [

25]: (i) definition of the system boundary (e.g., road adjacent to a stream) and threats (e.g., natural disaster: slope failures, subsidence and undermining of the stream slopes), (ii) identification of critical functions such as the transportation system functionality, (iii) selection of indicators (meaning that each cell of the matrix acts as an value of how well the system behaves) implementing expert judgement on a relative numerical scale from 0 (being the least resilient or having the highest impact), 1 (low), 2 (medium), 3 (high) to 4 (very high resilient), (iv) assessment of the overall resilience of the system by aggregating the cells scores across the matrix.

3.2. How is the Resilience Matrix Table Working?

Taking into consideration that the most critical function is the proper operation of the Provincial Road 3, the technical—absorption cell is assigned a rating according to the ability of the system to withstand any new heavy rainfall episode in such a way that will be able to resist from potential failures similar to those that resulted in the road devastation before the civil engineering mitigation measures took place. To succeed in accomplishing that in the case study of the Provincial Road 3, building codes, construction procedures (Lee et al., 2018) numerical models and engineering analyses took place, during the working out of the geotechnical study of the examined area taking into consideration different alternatives—scenarios regarding the occurrence of extreme weather events. Regarding the interaction of technical—adaption, the appearance of subsurface drainage during the construction works in areas B to D, resulted in the construction of a drainage system well with the intention to regulate the groundwater.

Another example is the interaction between economics and recovery. In this, a rating is assigned based on the assumption that the size of the potential slope failure would adjust the time of the repair works needed for the restoration of the road. In case of a new road closure due to new failure, the citizens’ perception of the surrounding examined area is estimated to be positive, because minor new technical mitigation works will be required. To this direction, the interaction between economic—preparation will lead to less budget than the one needed for the restoration of the road.

Considering the environmental impact from the one side was deteriorated due to the increased carbon dioxide emissions because of the prolonged time travel after the disruption but on the other side slope failures, subsidence and undermining were restored, and the environmental view of the examined area was restored too. Studying the interaction of environmental—social aspect of resilience, it can be said that in high frequency but lower impact events as a storm, the society needs to be able to function to the fullest extent possible, whereas in lower frequency but higher impact events such as disastrous landslide, the services for response and survival will be very important in order to allow to return to socio-economic functionality [

16].

Regarding the technical—preparation cell, the ability to proactively mitigate the effects of the disruptive events by constructing subdrainage systems confirm the capability of appreciating the scale of the rescue task and devising strategies prior to disruption.

Finally, studying the relationship between social and preparation, public safety and quality of life are connected to how well-prepared society is, because the absence of preparation in the appearance of a natural hazard is associated with the lack of understanding and information on the effects of a disruptive event. On the other hand, speaking about the relationship between social and absorption, one could say that the restoration of the road can improve the daily life of the people that cross by that segment of the examined Provincial Road 3. As far as the relation between social and adaption it concerns, it can be highlighted that the closure of the Provincial Road 3 due to the civil engineering restoration works affected partially the local traffic and as a result the access to social needs such as emergency services or medical care [

4].

Thus, the above-mentioned remarks are quantified in the following

Table 5, which mentions the ratings for each cell of the resilience matrix, estimated by the author of this manuscript, considering the road functionality, as well as the improved geotechnical conditions of the examined study area, after the mitigation works. The rating for each interaction has been assigned to an analogous way as the one estimated for the landslide instability index in Section 3.2.2.

To an analogous calculation as the one estimated for the landslide instability index (Section 3.2.2), the resilience index for the road segment of provincial road 3 is calculated as follows:

Based on the Australian Disaster Resilience Index (ADRI) [

26], which is a nationally standardized index of Australian communities’ capacity for disaster resilience, the estimated Resilience Index for the examined case study, after the fulfillment of the restoration technical works, was found to be equal to 78.40. Taking into account that the disaster resilience is a protective characteristic that acts to reduce the effects of, and losses from, natural hazards not only regarding the resilience of individuals, but also the resilience as a system of social, economic and institutional factors and based on the following

Table 6, it is concluded that the Resilience Index for the examined segment of the Provincial Road 3 after the accomplishment of the restoration mitigation measures is categorized as high disaster resilience.

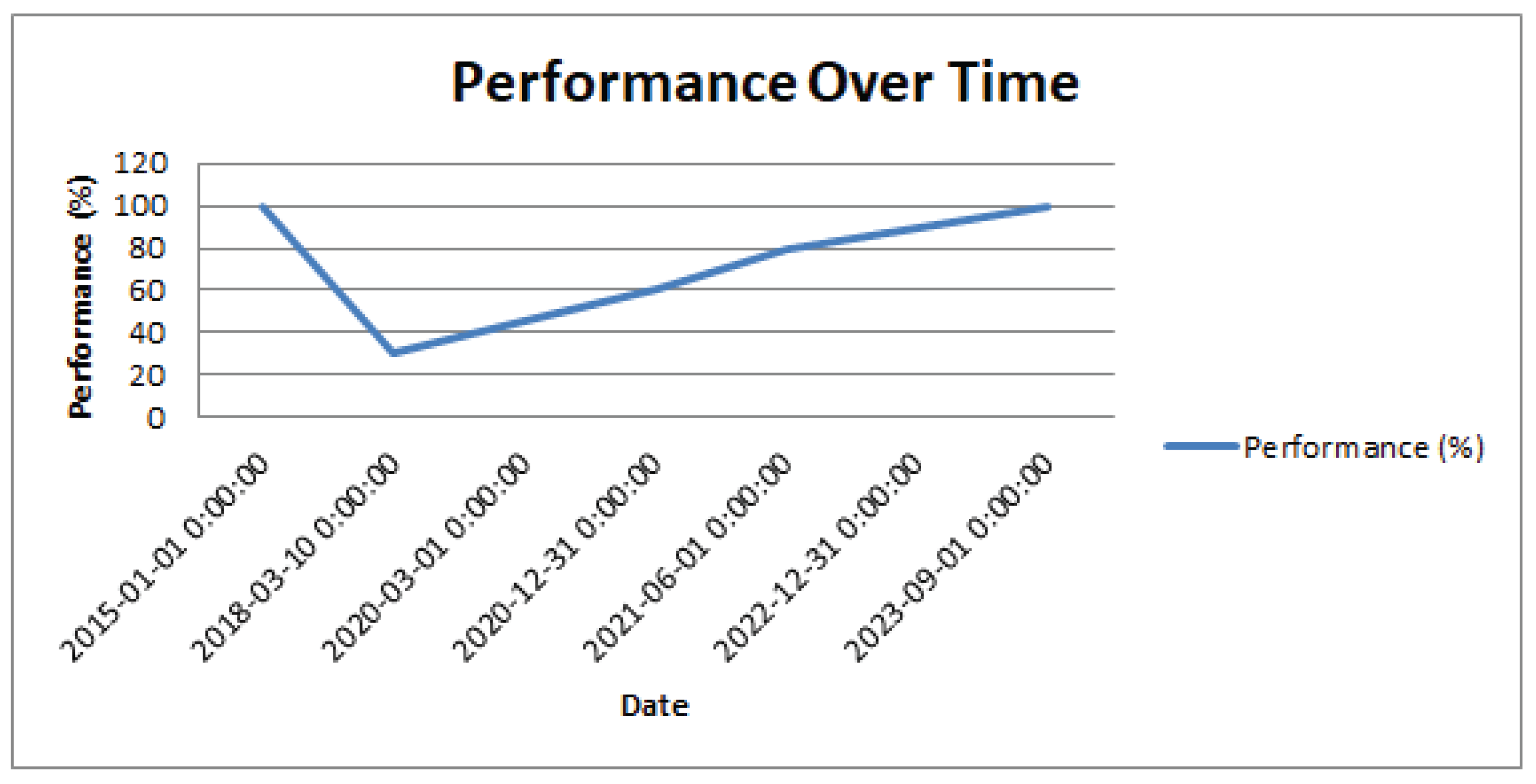

In the following

Figure 12, the performance of the calculated resilience index, associated with the performance of the Provincial Road 3 (before the disastrous event, during the period of the design phase and the construction stage and after the restoration of the road) is depicted.

4. Discussion

As mentioned in the subsection 2.3, the selected parameters for the construction of the RES matrix were based on the cause—effect interaction. The same philosophy has been followed for the implementation of DPSIR framework, regarding Provincial Road 3 [e.g., the cause-effect relationships of hazard to the geotechnical behavior of the mitigation technical works of the case study [

4]. Thus, the “drivers” (e.g., driving forces), in our case study are the slopes and the bridge foundation which are important components in transportation networks because they provide mobility for passengers and goods to the destination point [

4]. “Pressures”, such as serious subsidence to the examined case study road, can take place due to the loadings from heavy and large commercial vehicles. Another type of pressure could be an incident of an earthquake or the episode of heavy rainfall resulting in floods where hydraulic inputs and outputs to soil and drainage system are directly important to geotechnical failures (Lee, 2018). Furthermore, a pressure could be a wildfire as the one which took place in the summer of 2021 in an area (e.g., Varimpobi) very close to the case study (during the construction stage of areas B to D) and it almost reached the outer limits of the construction site with the danger of burning the vegetation which is located adjacent to the examined road and the slopes of the Chelidonous stream.

Regarding the “states”, they are correlated to robustness, rapidity, redundancy and resourcefulness. Robustness in our case study is associated with the estimation of bearing capacity and instability index.

Rapidity with respect to time is correlated to how fast the bureaucratic procedures (e.g., agreement for the beginning of the project, searching for extra budget, delay of permissions from different organizations of utility networks due to CONVID -19 restrictions) were completed to fulfill the civil engineering mitigation works in the examined area.

Redundancy is related to the supplementary study which is needed due to the unexpected rainfall episodes that took place during the reconstruction works. Finally, resourcefulness is the cost required for the restoration of the road.

As far as “Impacts” it concerns, these are the effects of the damaged geotechnical components (change in traffic volumes and times due to the closure of the examined segment of the road), construction costs for mitigation and repair) and in the case study the closure of the examined segment of the road for about three years resulted in the loss of functionality and eventually affected the surrounding community [

4].

Finally, “Responses” are associated with the mitigation measures that took place (construction of piles and walls, improvement of the existing drainage surface system of the road), which are analytically described in the subsection 2.2. According to the previously mentioned, Resilience Matrix (RM) allows the use of both qualitative and quantitative data in the resilience scoring process. In addition, RM is adaptive enough to be used as a tool considering any level of data availability but detailed enough to support decision making [

27,

28]. Thus, improving the resilience of geotechnical engineering structures and preventing them from large scale collapse to small scale damage in unexpected conditions is of great importance to the safety of the infrastructure, the citizens and the society in general [

1]. As a result, the present study can contribute to the implementation of EU Directives by fostering a culture of preparedness and proactive risk management [

29].

5. Conclusions

One way to reduce the impacts of disasters on the nation and its communities is to invest in enhancing resilience. Enhanced resilience allows better planning to reduce disaster losses—rather than waiting for an event to occur and paying for it afterward [

11].

In order to practically implement resilience thinking in geotechnical engineering, a framework that can quantitatively measure the resilience of geotechnical infrastructure is needed [

3]. To this direction, in the present study, the resilience of the Attica region’s Provincial Road 3 in Greece due to adjacent stream erosion and subsequent slope failure was presented by explaining the geological engineering study that was undertaken and depicting the steps of the civil engineering stabilization works that were implemented. Furthermore, in the context of this study, the hazard of the existing condition of the slopes of the Chelidonous stream and of Provincial Road 3 of the Attica Region before the failure, was confirmed, using the Rock Engineering System methodology for soil and soft rock slopes.

Furthermore, a tool for semi-quantitative assessment of the examined segment of the road resilience after the end of the rehabilitation measures was analyzed, highlighting, in parallel the metrics and indicators needed for the estimation of resilience from a quantitative point of view. This case study emphasizes the need to maintain the early focus on resilience through design and construction. It was found that using a semi-quantitative methodology (RES for estimating the slope instability index and Resilience matrix for the evaluation of the constructed technical works) can associate designers and subsequently decision makers with valuable tools for facilitating decision making for more sustainable solutions and contributing to long lasting duration of civil engineering projects despite the appearance of extreme weather conditions or earthquake events or even the (mega) wildfires whose frequency is getting more and more alarming.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

No new data was created.

Acknowledgments

This paper is based on the findings from the geological and geotechnical studies executed for the restoration of part of the Provincial Road 3 belonging to the Region of Attica. The author would like to express his gratitude to: (a) the Directorate of Technical Works (Central Section) of the Region of Attica for providing him with technical reports and photographs, (b) the EDAFOS Engineering Consultants, the designer of the restoration works and (c) the VASARTIS, the contractor of the rehabilitation project. Furthermore, the author expressing the role of the supervisor from the Regional Authority of Attica’s Directorate of Technical Works, was the main supervisor of the geological-geotechnical study and one of the supervisors of the restoration project of the examined case study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author has no conflicts of interest to declare and there is no financial interest in reporting.

References

- Zheng, G.; Cheng, X.; Zhou, H.; Zhang, T.; Diao, Y.; Dong Guo, W.; Wang, R.; Yi, F. Resilient evaluation and control in Geotechnical and Underground Engineering. In Proceedings of the 20th International Conference on Soil Mechanics and Geotechnical Engineering (ICSMGE), Sydney, Australia; 01-05/05/2022. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolaou, S. Geotechnical Resilience: It’s a Matter of Choice. GEOSTRATA Magazine, 23(3):18-20, 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M. Resilience Assessment in Geotechnical Engineering. Master Thesis, of Applied Sciences in Civil Engineering, presented to the University of Waterloo, Ontario, Canada, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, M.; Basu, D. An Integrated Approach for Resilience and Sustainability in Geotechnical Engineering. Indian Geotech J, 2018, 48 (2): 207-234. [CrossRef]

- Argyroudis, S. Resilience metrics for transport networks: a review and practical examples for bridges., Proceedings of the Institution of Civil Engineers—Bridge Engineering. Volume 175 Issue 3. September 2022, pp. 179-192. [CrossRef]

- EDAFOS Engineering Consultants, S.A. Geological and Geotechnical Factual and Interpretation Report of Provincial Road No. 3. Directorate of Technical Works, Region of Attica, 2018. Unpublished technical report.

- Tavoularis, N. Tavoularis N. Towards the resilience of Attica Region’s Provincial Road 3 in Greece, due to slope failure by applying civil engineering techniques and Rock Engineering System assessment, EGU General Assembly 2022, Vienna, Austria, 23–27 May 2022, EGU22-11196. [CrossRef]

- Tavoularis, N.; Papathanassiou, G.; Ganas, A.; Argyrakis, P. Development of the landslide susceptibility map of Attica Region, Greece based on the method of rock engineering system. Land journal , 2021. [CrossRef]

- EDAFOS Engineering Consultants, S.A. Geotechnical foundation study of the bridge – culvert of the Provincial Road 3. Directorate of Technical Works, Region of Attica, 2021. Unpublished technical report.

- Holling, C.S. Resilience and stability of ecological systems. Annual Review of Ecology and Systematics, 1973(4): 1-23.

- National Research Council. Disaster Resilience: A National Imperative. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. 2012. [CrossRef]

- National Infrastructure Advisory Council. Critical infrastructure resilience final report and recommendations, 2009. Retrieved from https://www.dhs.gov/xlibrary/assets/niac/niac_critical_infrastructure_resilience.pdf.

- Francis, R.; Bekera, B. Metric and frameworks for resilience analysis of engineered and infrastructure systems, Reliability Engineering and System Safety, 2014, 121, 90-103.

- Ouyang, M.; Duenas-Osorio, L.; Min, X. A three-stage resilience analysis framework for urban infrastructure systems, Structural Safety, 2012, 36-37, 23-31.

- Reddy, K.; Janga, J.K.; Kumar, G. Sustainability and Resilience: A New Paradigm in Geotechnical and Geoenvironmental Engineering. Indian Geotech J, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Brabhaharan, P. Resilience based design in geotechnical engineering. NZGS Symposium 2021, Good grounds for the future, 24-26 March 2021, Dunedin, New Zealand.

- Bruneau, M.; Chang, S.; Eguchi, R.; Lee, G. A framework to quantitatively assess and enhance the seismic resilience of communities. Earthquake Spectra 2003, 19:733–752.

- Ganin, AA.; Kitsak, M.; Marchese, D.; Keisler, JM.; Seager, T.; Linkov, I. Resilience and efficiency in transportation networks. Science Advances 2017, 3 (12).

- Hariri-Ardebili, M. Risk, reliability, resili (R3) and beyond in dam engineering: A state-of-the-art review. International Journal of Disaster Risk Reduction 31 (2018): 806-831, Elsevier.

- Reddy, K.; Janga, J.K.; Verma, G.; Nagaraja, B. Integration and quantification of resilience and sustainability in engineering projects. Journal of the Indian Institute of Science, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Hudson, J. : Rock Engineering Systems: Theory and Practice, Ellis Horwood Limited: Chichester, 1992.

- Tavoularis, N.; Koumantakis, I.; Rozos, D.; Koukis, G. The contribution of landslide susceptibility factors through the use of Rock Engineering System (RES) to the prognosis of slope failures. An application in Panagopoula and Malakasa landslide areas in Greece. Geotechnical and Geological Engineering journal, /: DOI 10.1007/s10706-017-0403-9. (http://rdcu.be/yiK7), 2017.

- Tavoularis, N.; Koumantakis, I.; Rozos, D.; Koukis, G. An implementation of rock engineering system 448 (RES) for ranking the instability potential of slopes in Greek territory. An application in Tsakona area (Peloponnese—prefecture of Arcadia). Bulletin of Geological Society of Greece. vol. XLIX, 38—58, 2015. [CrossRef]

- Brabb, E.; Bonilla, M.G.; Pampeyan, E. Landslide susceptibility in San Mateo County, California; US Geological Survey Miscellaneous Field Studies, Map MF-360, scale 1:62,500, 1972 (reprinted in 1978).

- Fox-Lent, C.; Bates, M.; Linkov, I. A matrix approach to community resilience assessment: an illustrative case at Rockaway Peninsula. Environ Syst Decis 2015, 35: 209-218.

- Parsons, M.; Birch, S.; Forster, N.; Boshoff, J. State of Disaster Resilience Report 2025, Australian Disaster Resilience Index Version 2, Australian Government, National Emergency Management Agency, https://naturalhazards.com.au/resources/publications/report/state-disaster-resilience-australia-2025.

- Linkov I; Eisenberg DA; Bates ME; Chang D, Convertino M; Allen JH; Seager TP. Measurable resilience for actionable policy. Environ Sci Technol 2013a, 47(18):10108–10110.

- Linkov I; Eisenberg DA; Plourde K; Seager TP; Allen J; Kott A. Resilience metrics for cyber systems. Environ Syst Decis 2013b, 33(4):471–476.

- Sakkas, G.; Kalapodis, N.; Kazantzidou-Firtinidou, D. Enhancing resilience in critical infrastructures through innovative pathways—The FIRELOGUE and STRATEGY projects approaches in emergency management. Proceedings of the 65th ESReDA Seminar, November 14-15, 2024, NCSR Demokritos, Athens, Greece.

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).