Submitted:

04 July 2025

Posted:

08 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

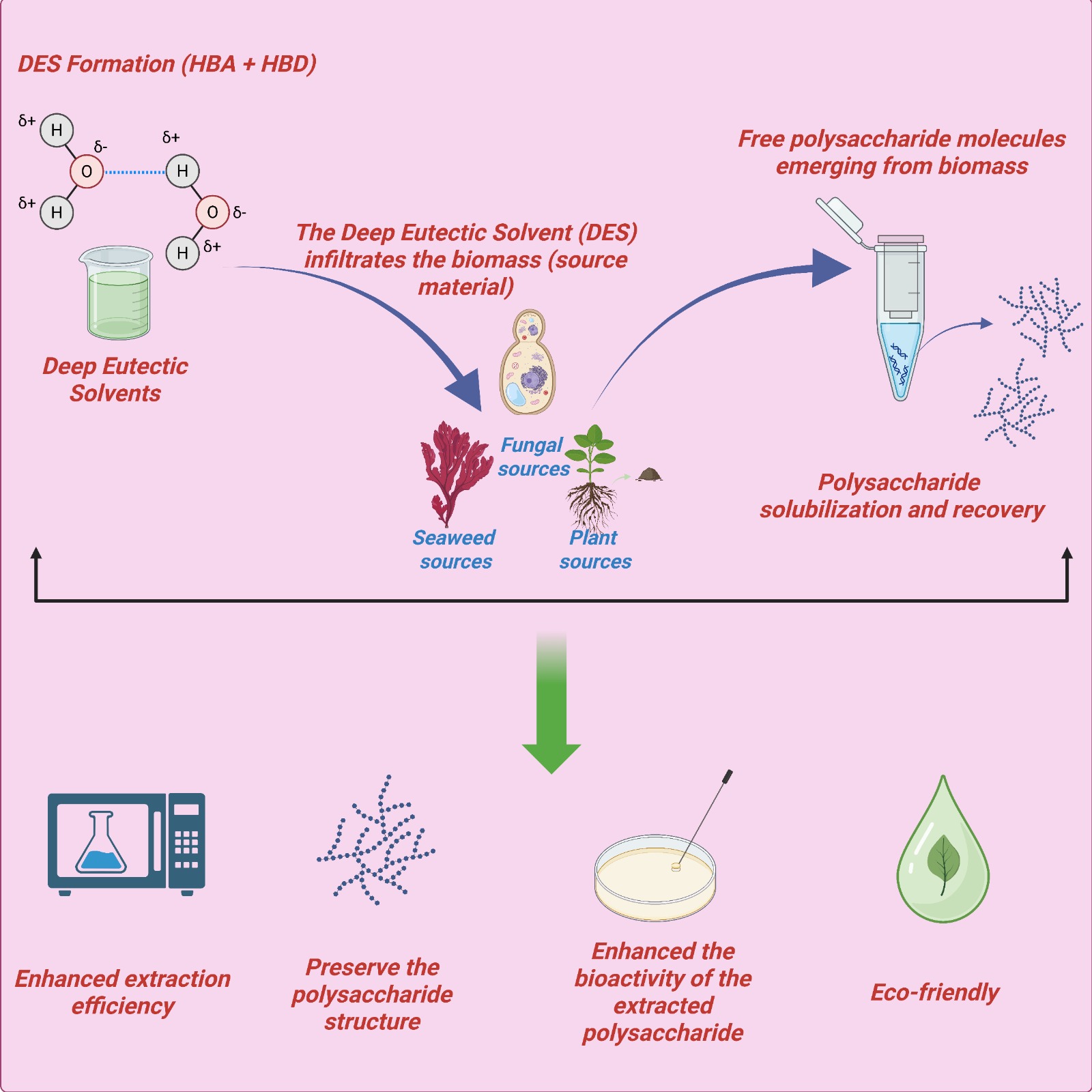

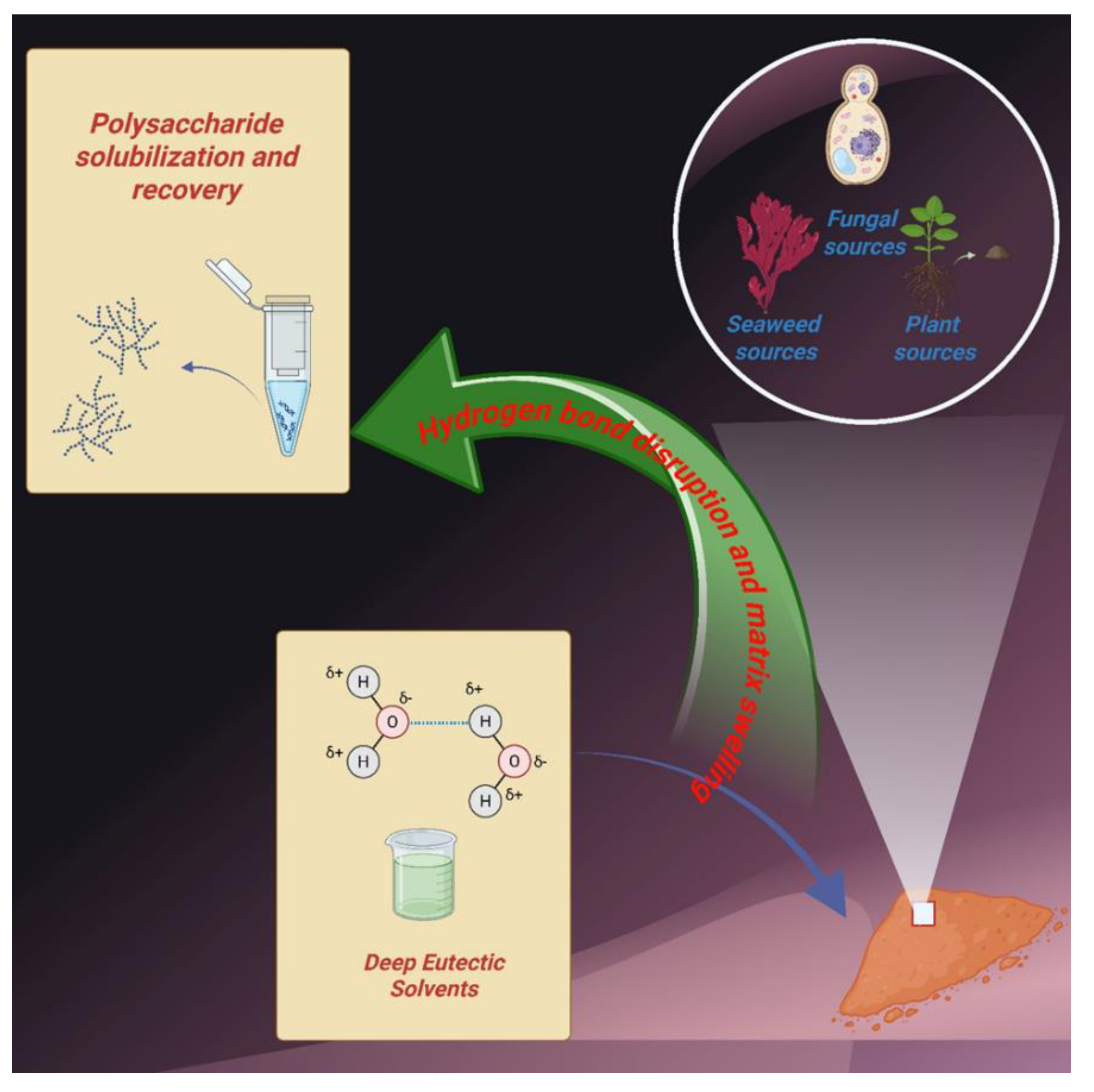

Fundamentals of DESs Relevant to Polysaccharide Systems

Hydrogen Bonding Networks and Viscosity Modulation in Polysaccharide-Compatible DESs

Tailoring Polarity and Solvent Microenvironments for Polysaccharide Affinity

Mechanistic Insights into DES–Polysaccharide Interactions

Role of DES Composition in Breaking Glycosidic and Hydrogen Bonding Networks

Enhancing Polysaccharide Solubility and Dispersibility Using DESs

In Situ vs. Pre-Formulated DES

AI, ML, and Biotechnological Innovations in DES–Polysaccharide Research

Challenges and Future Directions

5. Conclusions

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Md Yusoff MH, Shafie M. Pioneering polysaccharide extraction with deep eutectic solvents: A review on impacts to extraction yield, physicochemical properties and bioactivities. Int J Biol Macromol 2025; 306: 141469. [CrossRef]

- Tian X, Liang T, Liu Y, Ding G, Zhang F, Ma Z. Extraction, Structural Characterization, and Biological Functions of Lycium Barbarum Polysaccharides: A Review. Biomolecules 2019; 9 (9). [CrossRef]

- Chen Y, Yao F, Ming K, Wang D, Hu Y, Liu J. Polysaccharides from Traditional Chinese Medicines: Extraction, Purification, Modification, and Biological Activity. Molecules 2016; 21 (12). [CrossRef]

- Nakaweh A, Al-Akayleh F, Al-Remawi M, Abdallah Q, Agha ASA. Deep eutectic system-based liquisolid nanoparticles as drug delivery system of curcumin for in-vitro colon cancer cells. J Pharm Innov 2024; 19 (2): 18.

- Al-Akayleh F, Alkhawaja B, Al-Zoubi N, Abdelmalek SM, Daadoue S, AlAbbasi D et al. Novel therapeutic deep eutectic system for the enhancement of ketoconazole antifungal activity and transdermal permeability. J Mol Liq 2024; 413: 125975.

- Al-Akayleh F, Alkhawaja B, Al-Remawi M, Al-Zoubi N, Nasereddin J, Woodman T et al. An Investigation into the Preparation, Characterization, and Therapeutic Applications of Novel Gefitinib/Capric Acid Deep Eutectic Systems. J Pharm Innov 2024; 19 (6): 79. [CrossRef]

- Alsoy Altinkaya S. A perspective on cellulose dissolution with deep eutectic solvents. Frontiers in Membrane Science and Technology 2024; Volume 3 - 2024. [CrossRef]

- Zhang L, Wang M. Optimization of deep eutectic solvent-based ultrasound-assisted extraction of polysaccharides from Dioscorea opposita Thunb. Int J Biol Macromol 2017; 95: 675-681. [CrossRef]

- Li R, Shi G, Chen L, Liu Y. Polysaccharides extraction from Ganoderma lucidum using a ternary deep eutectic solvents of choline chloride/guaiacol/lactic acid. Int J Biol Macromol 2024: 130263.

- Saravana PS, Cho Y-N, Woo H-C, Chun B-S. Green and efficient extraction of polysaccharides from brown seaweed by adding deep eutectic solvent in subcritical water hydrolysis. Journal of Cleaner Production 2018; 198: 1474-1484. [CrossRef]

- Nie J-Y, Chen D, Lu Y. Deep Eutectic Solvents Based Ultrasonic Extraction of Polysaccharides from Edible Brown Seaweed Sargassum horneri. Journal of Marine Science and Engineering 2020.

- Shang X-c, Chu D, Zhang J-x, Zheng Y, Li Y. Microwave-assisted extraction, partial purification and biological activity in vitro of polysaccharides from bladder-wrack (Fucus vesiculosus) by using deep eutectic solvents. Sep Purif Technol 2020: 118169.

- Zhang W, Cheng S, Zhai X, Sun J-s, Hu X, Pei H-s et al. Green and Efficient Extraction of Polysaccharides From Poria cocos F.A. Wolf by Deep Eutectic Solvent. Nat Prod Commun 2020; 15.

- Cai C, Wang Y, Yu W, Wang C, Li F, Tan Z. Temperature-responsive deep eutectic solvents as green and recyclable media for the efficient extraction of polysaccharides from Ganoderma lucidum. Journal of Cleaner Production 2020; 274: 123047. [CrossRef]

- Kim EJ, Kim CY, Yoon KY. Application of Taguchi Method to Optimize Deep Eutectic Solvent-Based Ultrasound-Assisted Extraction of Polysaccharides from Maca and Its Biological Activity. Food and Bioprocess Technology 2025; 18 (3): 2709-2720. [CrossRef]

- Zhang R, Yang X, Liu Y, Hu J, Hu K, Liu Y et al. Investigation of natural deep eutectic solvent for the extraction of crude polysaccharide from Polygonatum kingianum and influence of metal elements on its immunomodulatory effects. Talanta 2024; 271: 125721. [CrossRef]

- Wen Y, Chen J. Optimization of Ultrasound-Assisted Deep Eutectic Solvent Extraction, Characterization, and Bioactivities of Polysaccharide from Pericarpium Citri Reticulatae. Applied biochemistry and biotechnology 2024.

- Qu H, Wu Y, Luo Z, Dong Q, Yang H, Dai C. An efficient approach for extraction of polysaccharide from abalone (Haliotis Discus Hannai Ino) viscera by natural deep eutectic solvent. Int J Biol Macromol 2023; 244: 125336. [CrossRef]

- Wu Y, Hu H, Yang G, Chen Y, Zhong X, Li S et al. Enhancing the black truffle polysaccharide extraction efficiency using a combination of natural deep eutectic solvents and ultrasound-assisted techniques. Journal of Food Measurement and Characterization 2025; 19 (4): 2208-2219. [CrossRef]

- Zhang H, Lin Y, Bao Y, Li W-J, Hong B, Zhao M. A high selective separation method for high-purity polysaccharides from dandelions by density-oriented deep eutectic solvent ultrasonic-assisted system. Sustainable Chemistry and Pharmacy 2024; 42: 101844. [CrossRef]

- Zhang J, Ye Z, Liu G, Liang L, Wen C, Liu X et al. Subcritical Water Enhanced with Deep Eutectic Solvent for Extracting Polysaccharides from Lentinus edodes and Their Antioxidant Activities. Molecules 2022; 27.

- Gao Z, Zha F, Zhang J, Zhong Q, Tian H, Guo X. Simultaneous extraction of Saponin and Polysaccharide from Acanthopanax senticosus fruits with three-component Deep eutectic solvent and the extraction mechanism analysis. J Mol Liq 2024; 396: 123977. [CrossRef]

- Chen L, Yang Y-Y, Zhou R-r, Fang L-z, Zhao D, Cai P et al. The extraction of phenolic acids and polysaccharides from Lilium lancifolium Thunb. using a deep eutectic solvent. Analytical Methods 2021; 13 (10): 1226-1231. [CrossRef]

- Wen Y, Xiangyi Y, and Chen H. Optimization of ultrasonic-assisted deep eutectic solvent extraction, characterization, and bioactivities of polysaccharides from Eucommia ulmoides. Prep Biochem Biotechnol 2025; 55 (5): 577-589. [CrossRef]

- Liu M, Wang S, Bi W, Chen DDY. Plant polysaccharide itself as hydrogen bond donor in a deep eutectic system-based mechanochemical extraction method. Food Chem 2023; 399: 133941. [CrossRef]

- Meng J, Guan C, Chen Q, Pang X, Wang H, Cui X et al. Structural Characterization and Immunomodulatory Activity of Polysaccharides from Polygonatum sibiricum Prepared with Deep Eutectic Solvents. J Food Qual 2023.

- Tang Z, Xu Y, Cai C, Tan Z. Extraction of Lycium barbarum polysaccharides using temperature-switchable deep eutectic solvents: A sustainable methodology for recycling and reuse of the extractant. J Mol Liq 2023; 383: 122063. [CrossRef]

- Xia B, Liu Q, Sun D, Wang Y, Wang W, Liu D. Ultrasound-Assisted Deep Eutectic Solvent Extraction of Polysaccharides from Anji White Tea: Characterization and Comparison with the Conventional Method. Foods 2023. [Epub ahead of print] . [CrossRef]

- Chen X, Wang R, Tan Z. Extraction and purification of grape seed polysaccharides using pH-switchable deep eutectic solvents-based three-phase partitioning. Food Chem 2023; 412: 135557. [CrossRef]

- Xue J, Su J-S, Wang X, Zhang R, Li X, Li Y et al. Eco-Friendly and Efficient Extraction of Polysaccharides from Acanthopanax senticosus by Ultrasound-Assisted Deep Eutectic Solvent. Molecules 2024; 29.

- Wang W, Lin L, Zhao M. Simultaneously efficient dissolution and structural modification of chrysanthemum pectin: Targeting at proliferation of Bacteroides. Int J Biol Macromol 2024; 267: 131469. [CrossRef]

- Pan X, Xu L, Meng J, Chang M, Cheng Y, Geng X et al. Ultrasound-Assisted Deep Eutectic Solvents Extraction of Polysaccharides From Morchella importuna: Optimization, Physicochemical Properties, and Bioactivities. Frontiers in Nutrition 2022; Volume 9 - 2022. [CrossRef]

- Meng Y, Sui X, Pan X, Zhang X, Sui H, Xu T et al. Density-oriented deep eutectic solvent-based system for the selective separation of polysaccharides from Astragalus membranaceus var. Mongholicus under ultrasound-assisted conditions. Ultrason Sonochem 2023; 98: 106522. [CrossRef]

- Feng S, Zhang J, Luo X, Xu Z, Liu K, Chen T et al. Green extraction of polysaccharides from Camellia oleifera fruit shell using tailor-made deep eutectic solvents. Int J Biol Macromol 2023: 127286.

- Luo L, Fan W, Qin J, Guo S, Xiao H, Tang Z. Study on Process Optimization and Antioxidant Activity of Polysaccharide from Bletilla striata Extracted via Deep Eutectic Solvents. Molecules 2023; 28.

- Yan X-Y, Cai Z-H, Zhao P-Q, Wang J-D, Fu L-N, Gu Q et al. Application of a novel and green temperature-responsive deep eutectic solvent system to simultaneously extract and separate different polar active phytochemicals from Schisandra chinensis (Turcz.) Baill. Food Res Int 2023; 165: 112541. [CrossRef]

- Xue J, Su J, Wang X, Zhang R, Li X, Li Y et al. Eco-Friendly and Efficient Extraction of Polysaccharides from Acanthopanax senticosus by Ultrasound-Assisted Deep Eutectic Solvent. Molecules 2024. [Epub ahead of print] . [CrossRef]

- Al-Akayleh F, Al-Remawi M, Agha A, Abu-Nameh E. Applications and risk assessments of ionic liquids in chemical and pharmaceutical domains: an updated overview. Jordan Journal of Chemistry (JJC) 2023; 18 (2): 53-76.

- Alkhawaja B, Al-Akayleh F, Al-Rubaye Z, Bustami M, Smairat Ma, Agha AS et al. Dissecting the stability of Atezolizumab with renewable amino acid-based ionic liquids: Colloidal stability and anticancer activity under thermal stress. Int J Biol Macromol 2024; 270: 132208.

- Al-Akayleh F, Ali HHM, Ghareeb MM, Al-Remawi M. Therapeutic deep eutectic system of capric acid and menthol: Characterization and pharmaceutical application. J Drug Deliv Sci Technol 2019; 53: 101159.

- Daadoue S, Al-Remawi M, Al-Mawla L, Idkaidek N, Khalid RM, Al-Akayleh F. Deep eutectic liquid as transdermal delivery vehicle of Risperidone. J Mol Liq 2022; 345: 117347.

- Al-Mawla L, Al-Akayleh F, Daadoue S, Mahyoob W, Al-Tameemi B, Al-Remawi M et al. Development, characterization, and ex vivo permeation assessment of diclofenac diethylamine deep eutectic systems across human skin. J Pharm Innov 2023; 18 (4): 2196-2209.

- Luhaibi DK, Ali HHM, Al-Ani I, Shalan N, Al-Akayleh F, Al-Remawi M et al. The formulation and evaluation of deep eutectic vehicles for the topical delivery of azelaic acid for acne treatment. Molecules 2023; 28 (19): 6927.

- Al-Akayleh F, Khalid R, Hawash D, Al-Kaissi E, Al-Adham I, Al-Muhtaseb N et al. Antimicrobial potential of natural deep eutectic solvents. Lett Appl Microbiol 2022; 75 (3): 607-615.

- Al-Akayleh F, Adwan S, Khanfar M, Idkaidek N, Al-Remawi M. A novel eutectic-based transdermal delivery system for risperidone. AAPS PharmSciTech 2021; 22: 1-11.

- Alkhawaja B, Al-Akayleh F, Nasereddin J, Malek SA, Alkhawaja N, Kamran M et al. Levofloxacin–fatty Acid systems: dual enhancement through deep eutectic formation and solubilization for Pharmaceutical potential and antibacterial activity. AAPS PharmSciTech 2023; 24 (8): 244.

- Alkhawaja B, Al-Akayleh F, Nasereddin J, Kamran M, Woodman T, Al-Rubaye Z et al. Structural insights into novel therapeutic deep eutectic systems with capric acid using 1D, 2D NMR and DSC techniques with superior gut permeability. RSC advances 2024; 14 (21): 14793-14806.

- Crespo EA, Silva LP, Martins MAR, Bülow M, Ferreira O, Sadowski G et al. The Role of Polyfunctionality in the Formation of [Ch]Cl-Carboxylic Acid-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. Ind Eng Chem Res 2018.

- Aragón-Tobar CF, Endara D, de la Torre E. Dissolution of Metals (Cu, Fe, Pb, and Zn) from Different Metal-Bearing Species (Sulfides, Oxides, and Sulfates) Using Three Deep Eutectic Solvents Based on Choline Chloride. Molecules 2024; 29.

- Chen Y, Wang Y, Bai Y, Feng M, Zhou F, Lu Y et al. Mild and efficient recovery of lithium-ion battery cathode material by deep eutectic solvents with natural and cheap components. Green Chemical Engineering 2023; 4 (3): 303-311. [CrossRef]

- Cicci A, Sed G, Bravi M. Potential of Choline Chloride-based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (nades) in the Extraction of Microalgal Metabolites. Chemical engineering transactions 2017; 57: 61-66.

- Dai Y, van Spronsen J, Witkamp GJ, Verpoorte R, Choi YH. Natural deep eutectic solvents as new potential media for green technology. Anal Chim Acta 2013; 766: 61-68.

- Długosz O, Krawczyk P, Banach M. Equilibrium, kinetics and thermodynamics of metal oxide dissolution based on CuO in a natural deep eutectic solvent. Chem Eng Res Des 2024.

- Feng Y, Liu G, Sun H, Xu C, Wu B, Huang C et al. A novel strategy to intensify the dissolution of cellulose in deep eutectic solvents by partial chemical bonding. BioResources 2022.

- Gamare JS, Vats BG. A Hydrophobic Deep Eutectic Solvent for Nuclear Fuel Cycle: Extraction of Actinides and Dissolution of Uranium Oxide. Eur J Inorg Chem 2023.

- Guajardo N, Carlesi C, Aracena Á. Toluene Oxidation by Hydrogen Peroxide in Deep Eutectic Solvents. ChemCatChem 2015; 7.

- Gupta R, Gamare JS, Gupta SK, Kumar S. Direct dissolution of uranium oxides in deep eutectic solvent: An insight using electrochemical and luminescence study. J Mol Struct 2020; 1215: 128266.

- Hou Y, Wang Z, Ren S, Wu W. The applications of deep eutectic solvents in the separation of mixtures. Chin Sci Bull 2015; 60: 2490-2499.

- Kianpoor A, Sadeghi R. Novel acidic deep eutectic solvents: synthesis, phase diagram, thermal behavior, physicochemical properties and application. Journal of the Iranian Chemical Society 2024.

- Kumari T, Chauhan R, Sharma N, Kaur K, Krishnamurthy A, Pandey P et al. Zinc Chloride as Acetamide based Deep Eutectic Solvent. 2016.

- Liu Q, Che J, Yu Y, Chu D, Zhang H, Zhang F et al. Dissolving Chitin by Novel Deep Eutectic Solvents for Effectively Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Applied biochemistry and biotechnology 2024.

- Manasi I, King S, Edler KJ. Cationic micelles in deep eutectic solvents: effects of solvent composition. Faraday Discuss 2024.

- Migliorati V, Fazio G, Pollastri S, Gentili A, Tomai P, Tavani F et al. Solubilization properties and structural characterization of dissociated HgO and HgCl2 in deep eutectic solvents. J Mol Liq 2021; 329: 115505.

- Mu L, Gao J, Zhang Q, Kong F, Zhang Y, Ma Z et al. Research Progress on Deep Eutectic Solvents and Recent Applications. Processes 2023.

- Omar KA, Sadeghi R. New chloroacetic acid-based deep eutectic solvents for solubilizing metal oxides. J Mol Liq 2021.

- Popović BM, Uka D, Alioui O, Ždero Pavlović R, Benguerba Y. Experimental and COSMO-RS theoretical exploration of rutin formulations in natural deep eutectic solvents: solubility, stability, antioxidant activity, and bioaccessibility. J Mol Liq 2022.

- Ru J, Hua Y-x, Wang D, Xu C, Zhang Q, Jian L et al. Dissolution-electrodeposition pathway and bulk porosity on the impact of in situ reduction of solid PbO in deep eutectic solvent. Electrochimica Acta 2016; 196: 56-66.

- Sakhno T, Barashkov NN, Irgibaeva IS, Mendigaliyeva S, Bostan DS. Ionic Liquids and Deep Eutectic Solvents and Their Use for Dissolving Animal Hair. Advances in Chemical Engineering and Science 2020.

- Schiavi PG, Altimari P, Sturabotti E, Giacomo Marrani A, Simonetti G, Pagnanelli F. Decomposition of Deep Eutectic Solvent Aids Metals Extraction in Lithium-Ion Batteries Recycling. Chemsuschem 2022; 15.

- Sharma GK, Sequeira RA, Pereira MM, Maity TK, Chudasama NA, Prasad K. Are ionic liquids and deep eutectic solvents the same?: Fundamental investigation from DNA dissolution point of view. J Mol Liq 2021; 328: 115386.

- Sharma A, Park YR, Garg A, Lee B-S. Deep Eutectic Solvents Enhancing Drug Solubility and Its Delivery. J Med Chem 2024.

- Söldner A. Deep Eutectic Solvents as Extraction, Reaction and Detection Media for Inorganic Compounds. 2020.

- Söldner A, Zách J, Iwanow M, Gärtner T, Schlosser M, Pfitzner A et al. Preparation of Magnesium, Cobalt and Nickel Ferrite Nanoparticles from Metal Oxides using Deep Eutectic Solvents. Chemistry (Easton) 2016; 22 37: 13108-13113.

- Zinov’eva IV, Fedorov A, Milevskii NA, Zakhodyaeva YA, Voshkin AA. Dissolution of Metal Oxides in a Choline Chloride–Sulphosalicylic Acid Deep Eutectic Solvent. Theor Found Chem Eng 2021; 55: 663 - 670.

- Zhu J, Shao C, Hao S, Xue K, Zhang J, Sun Z et al. Green synthesis of multifunctional cellulose-based eutectogel using a metal salt hydrate-based deep eutectic solvent for sustainable self-powered sensing. Chem Eng J 2025.

- Kundu D, Rao PS, Banerjee T. First-principles prediction of Kamlet–Taft solvatochromic parameters of deep eutectic solvent using the COSMO-RS model. Ind Eng Chem Res 2020; 59 (24): 11329-11339.

- Ren H, Chen C, Wang Q, Zhao D, Guo S. The Properties of Choline Chloride-based Deep Eutectic Solvents and their Performance in the Dissolution of Cellulose. Bioresources 2016; 11: 5435-5451.

- Md Yusoff MH, Shafie MH. Microwave-assisted extraction of polysaccharides from Micromelum minutum leaves using citric acid monohydrate-glycerol based deep eutectic solvents and evaluation of biological activities. Anal Chim Acta 2024; 1331: 343351.

- Bing Y, Zhang D-q, Xie C, Yu F, Yu S-t. Hydration of α-pinene catalyzed by oxalic acid/polyethylene glycol deep eutectic solvents. Journal of Fuel Chemistry and Technology 2021; 49: 330-338.

- Duan C, Tian C, Feng X, Tian G, Liu X, Ni Y. Ultrafast process of microwave-assisted deep eutectic solvent to improve properties of bamboo dissolving pulp. Bioresour Technol 2023; 370: 128543. [CrossRef]

- Chourasia VR, Bisht M, Pant KK, Henry RJ. Unveiling the Potential of Water as a Co-solvent in Microwave-assisted Delignification of Sugarcane Bagasse using Ternary Deep Eutectic Solvents. Bioresour Technol 2022: 127005.

- Ji Q, Yu X, Yagoub AE-GA, Chen L, Zhou C. Efficient removal of lignin from vegetable wastes by ultrasonic and microwave-assisted treatment with ternary deep eutectic solvent. Industrial Crops and Products 2020; 149: 112357.

- Al-Akayleh F, Alkhawaja B, Al-Remawi M, Al-Zoubi N, Nasereddin J, Woodman T et al. An Investigation into the Preparation, Characterization, and Therapeutic Applications of Novel Gefitinib/Capric Acid Deep Eutectic Systems. J Pharm Innov 2024; 19 (6): 79.

- Rifai A, Bayan A, Faisal A-A, Mayyas A-R, Jehad N, Safwan AR et al. Eutectic-based self-emulsifying drug delivery system for enhanced oral delivery of risperidone. J Dispersion Sci Technol: 1-12. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee S, Deshmukh SH, Bagchi S. Does Viscosity Drive the Dynamics in an Alcohol-Based Deep Eutectic Solvent? The journal of physical chemistry B 2022.

- Ren H, Chen C, Wang Q, Zhao D, Guo S. The properties of choline chloride-based deep eutectic solvents and their performance in the dissolution of cellulose. BioResources 2016; 11 (2): 5435-5451.

- Fan C, Sebbah T, Liu Y, Cao X. Terpenoid-capric acid based natural deep eutectic solvent: Insight into the nature of low viscosity. Cleaner Engineering and Technology 2021; 3: 100116. [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee S, Deshmukh SH, Chowdhury T, Bagchi S. Viscosity effects on the dynamics of diols and diol-based deep eutectic solvents. Photochemistry and Photobiology 2024; 100: 946 - 955.

- Fan C, Liu Y, Sebbah T, Cao X. A Theoretical Study on Terpene-Based Natural Deep Eutectic Solvent: Relationship between Viscosity and Hydrogen-Bonding Interactions. Global Challenges 2021; 5.

- Cheng K, Xu X, Song J, Chen Y, Kan Z, Li C. Molecular dynamics simulations of choline chloride and ascorbic acid deep eutectic solvents: Investigation of structural and dynamics properties. J Mol Graph Model 2024; 130: 108784.

- Sun Y, Jia XD, Yang R-J, Qin X, Zhou X, Zhang H et al. Deep eutectic solvents boosting solubilization and Se-functionalization of heteropolysaccharide: Multiple hydrogen bonds modulation. Carbohydr Polym 2022; 284: 119159.

- Shen XB, Sinclair NS, Wainright JS, Savinell RF. (Invited) Effects of Halide Anion Type and Alkyl Chain Length on Hydrogen Bonding in Eutectic Solvent System. ECS Meeting Abstracts 2022.

- D'agostino C, Harris RC, Abbott AP, Gladden LF, Mantle MD. Molecular motion and ion diffusion in choline chloride based deep eutectic solvents studied by 1H pulsed field gradient NMR spectroscopy. Physical chemistry chemical physics : PCCP 2011; 13 48: 21383-21391.

- Ren H, Chen C, Guo S, Zhao D, Wang Q. Synthesis of a Novel Allyl-Functionalized Deep Eutectic Solvent to Promote Dissolution of Cellulose. Bioresources 2016; 11: 8457-8469.

- Li R, Shi G, Chen L, Liu Y. Polysaccharides extraction from Ganoderma lucidum using a ternary deep eutectic solvents of choline chloride/guaiacol/lactic acid. Int J Biol Macromol 2024; 263: 130263. [CrossRef]

- Florindo C, Florindo C, McIntosh AJS, Welton T, Branco LC, Marrucho IM et al. A closer look into deep eutectic solvents: exploring intermolecular interactions using solvatochromic probes. Physical chemistry chemical physics : PCCP 2017; 20 1: 206-213.

- Teles ARR, Capela EV, Carmo RS, Coutinho JAP, Silvestre AJD, Freire MG. Solvatochromic parameters of deep eutectic solvents formed by ammonium-based salts and carboxylic acids. Fluid Phase Equilib 2017; 448: 15-21.

- He C, Shen F, Tian D, Huang M, Zhao L, Yu Q et al. Lewis acid/base mediated deep eutectic solvents intensify lignocellulose fractionation to facilitate enzymatic hydrolysis and lignin nanosphere preparation. Int J Biol Macromol 2023: 127853.

- Xia Q, Liu Y, Meng J, Cheng W, Chen W, Liu S et al. Multiple hydrogen bond coordination in three-constituent deep eutectic solvents enhances lignin fractionation from biomass. Green Chem 2018; 20: 2711-2721.

- Chen T, Guo G-m, Shen D, Tang YR. Metal Salt-Based Deep Eutectic Solvent Pretreatment of Moso Bamboo to Improve Enzymatic Hydrolysis. Fermentation 2023.

- Guo Y, Xu L, Shen F, Hu J, Huang M, He J et al. Insights into lignocellulosic waste fractionation for lignin nanospheres fabrication using acidic/alkaline deep eutectic solvents. Chemosphere 2021; 286 Pt 2: 131798.

- Tian D, Zhang Y, Wang T, Jiang B, Liu M, Zhao L et al. The swelling-induced fractionation strategy to mediate cellulose availability and lignin structural integrity. Chem Commun 2025.

- Huang J, Chang PR, Dufresne A. Polysaccharide Nanocrystals: Current Status and Prospects in Material Science. 2014.

- Liu H, Lin J, Hu Y, Lei H, Zhang Q, Tao X et al. DES-Assisted Extraction of Pectin from Ficus carica Linn. peel: Optimization, Partial Structure Characterization, Functional and Antioxidant Activities. Journal of the science of food and agriculture 2024.

- Shafie MH, Gan C-Y. Could choline chloride-citric acid monohydrate molar ratio in deep eutectic solvent affect structural, functional and antioxidant properties of pectin? Int J Biol Macromol 2020.

- Yang J, Wang Y, Zhang W, Li M, Peng F, Bian J. Alkaline deep eutectic solvents as novel and effective pretreatment media for hemicelluloses dissociation and enzymatic hydrolysis enhancement. Int J Biol Macromol 2021.

- Marullo S, Raia G, Bailey JJ, Gunaratne HQN, D'Anna F. Inulin Dehydration to 5-HMF in Deep Eutectic Solvents Catalyzed by Acidic Ionic Liquids Under Mild Conditions. ChemSusChem 2025; 18 (10): e202402522. [CrossRef]

- Cheng W-Y, Lam K-L, Pik-Shan Kong A, Chi-Keung Cheung P. Prebiotic supplementation (beta-glucan and inulin) attenuates circadian misalignment induced by shifted light-dark cycle in mice by modulating circadian gene expression. Food Res Int 2020; 137: 109437.

- Yahaya N, Mohamed AH, Sajid M, Zain NNM, Liao P-C, Chew KW. Deep eutectic solvents as sustainable extraction media for extraction of polysaccharides from natural sources: Status, challenges and prospects. Carbohydr Polym 2024; 338: 122199.

- Ling Z, Tang W, Su Y, Shao L, Wang P, Ren Y et al. Promoting enzymatic hydrolysis of aggregated bamboo crystalline cellulose by fast microwave-assisted dicarboxylic acid deep eutectic solvents pretreatments. Bioresour Technol 2021; 333: 125122.

- Sharma M, Mukesh C, Mondal D, Prasad K. Dissolution of α-chitin in deep eutectic solvents. RSC Advances 2013; 3: 18149-18155.

- Chen Q, Chen Y, Wu C. Probing the evolutionary mechanism of the hydrogen bond network of cellulose nanofibrils using three DESs. Int J Biol Macromol 2023; 234: 123694. [CrossRef]

- Soleimanzadeh H, Bektashi FM, Ahari SZ, Salari D, Olad A, Ostadrahimi A. Optimization of cellulose extraction process from sugar beet pulp and preparation of its nanofibers with choline chloride–lactic acid deep eutectic solvents. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2022; 13: 14457 - 14469.

- Ghasemi MF, Tsianou M, Alexandridis P. Solvent-Induced Decrystallization of Cellulose: Thermodynamics, Transport, and Kinetics. 2014.

- Wang X, Zhou P, Lv X-y, Liang YL. Insight into the structure-function relationships of the solubility of chitin/chitosan in natural deep eutectic solvents. Materials today communications 2021; 27: 102374.

- Gupta V, Thakur R, Das AB. Effect of natural deep eutectic solvents on thermal stability, syneresis, and viscoelastic properties of high amylose starch. Int J Biol Macromol 2021.

- Xiao Q, Dai M, Zhou H, Huang M, Lim LT, Zeng C. Formation and structure evolution of starch nanoplatelets by deep eutectic solvent of choline chloride/oxalic acid dihydrate treatment. Carbohydr Polym 2022; 282: 119105.

- Kim H, Kang S, Li K, Jung D, Park K, Lee J. Preparation and characterization of various chitin-glucan complexes derived from white button mushroom using a deep eutectic solvent-based ecofriendly method. Int J Biol Macromol 2020.

- Zeng C, Zhao H, Wan Z, Xiao Q, Xia H, Guo S. Highly biodegradable, thermostable eutectogels prepared by gelation of natural deep eutectic solvents using xanthan gum: preparation and characterization. RSC Advances 2020; 10: 28376 - 28382.

- Hiemstra ISA, Meinema JT, Eppink MHM, Wijffels RH, Kazbar A. Choline chloride-based solvents as alternative media for alginate extraction from brown seaweed. LWT 2024.

- Afifah N, Sarifudin A, Purwanto WW, Krisanti EA, Mulia K. Glucomannan isolation from porang (Amorphophallus muelleri Blume) flour using natural deep eutectic solvents and ethanol: A comparative study. Food Chem 2024; 453: 139610.

- Pedro SN, Valente BFA, Vilela C, Oliveira H, Almeida A, Freire MG et al. Switchable adhesive films of pullulan loaded with a deep eutectic solvent-curcumin formulation for the photodynamic treatment of drug-resistant skin infections. Materials Today Bio 2023; 22.

- Depoorter J, Mourlevat A, Sudre G, Morfin I, Prasad K, Serghei A et al. Fully Biosourced Materials from Combination of Choline Chloride-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents and Guar Gum. ACS Sustainable Chemistry & Engineering 2019.

- Keerthashalini P, Sobanadevi V, Uppuluri KB. Deep eutectic solvent assisted recovery of high molecular weight levan from an isolated Neobacillus pocheonensis BPSCM4. Prep Biochem Biotechnol 2023; 54: 407 - 418.

- Li X, Row KH. Separation of Polysaccharides by SEC Utilizing Deep Eutectic Solvent Modified Mesoporous Siliceous Materials. Chromatographia 2017; 80: 1161-1169.

- Das AK, Sharma M, Mondal D, Prasad K. Deep eutectic solvents as efficient solvent system for the extraction of κ-carrageenan from Kappaphycus alvarezii. Carbohydr Polym 2016; 136: 930-935.

- Tang PL, Hao E, Du Z, Deng J, Hou X, Qin J. Polysaccharide extraction from sugarcane leaves: combined effects of different cellulolytic pretreatment and extraction methods. Cellulose 2019; 26: 9423 - 9438.

- Zdanowicz M, Wilpiszewska K, Spychaj T. Deep eutectic solvents for polysaccharides processing. A review. Carbohydr Polym 2018; 200: 361-380. [CrossRef]

- Pan M, Zhao G, Ding C, Wu B, Lian Z, Lian H. Physicochemical transformation of rice straw after pretreatment with a deep eutectic solvent of choline chloride/urea. Carbohydr Polym 2017; 176: 307-314.

- Meng Y, Sui X, Pan X, Zhang X, Sui H, Xu T et al. Density-oriented deep eutectic solvent-based system for the selective separation of polysaccharides from Astragalus membranaceus var. Mongholicus under ultrasound-assisted conditions. Ultrason Sonochem 2023; 98.

- Li R, Hsueh P-H, Ulfadillah SA, Wang S-T, Tsai M-L. Exploring the Sustainable Utilization of Deep Eutectic Solvents for Chitin Isolation from Diverse Sources. Polymers 2024; 16.

- Xu L, Pan X-c, Li D, Wang Z, Tan L, Chang M et al. Structural characterization, rheological characterization, hypoglycemic and hypolipidemic activities of polysaccharides from Morchella importuna using acidic and alkaline deep eutectic solvents. LWT 2024.

- Sirviö JA, Hyypiö K, Asaadi S, Junka K, Liimatainen H. High-strength cellulose nanofibers produced via swelling pretreatment based on a choline chloride–imidazole deep eutectic solvent. Green Chem 2020; 22: 1763-1775.

- Ashworth C, Matthews RP, Welton T, Hunt PA. Doubly ionic hydrogen bond interactions within the choline chloride-urea deep eutectic solvent. Physical chemistry chemical physics : PCCP 2016; 18 27: 18145-18160.

- Wen L, Fan C, Cao X. One-step extraction and hydrolysis of crocin into crocetin by recyclable deep eutectic solvents. Industrial Crops and Products 2024; 209: 117969. [CrossRef]

- Santra S, Das M, Karmakar S, Banerjee R. NADES assisted integrated biorefinery concept for pectin recovery from kinnow (Citrus reticulate) peel and strategic conversion of residual biomass to L(+) lactic acid. Int J Biol Macromol 2023: 126169.

- Zhao J, Pedersen CM, Chang H, Hou X, Wang Y, Qiao Y. Switchable product selectivity in dehydration of N-acetyl-d-glucosamine promoted by choline chloride-based deep eutectic solvents. iScience 2023; 26.

- Lee CBTL, Wu TY, Yong KJ, Cheng CK, Siow LF, Jahim JM. Investigation into Lewis and Brønsted acid interactions between metal chloride and aqueous choline chloride-oxalic acid for enhanced furfural production from lignocellulosic biomass. The Science of the total environment 2022: 154049.

- AlZahrani YM, Britton MM. Probing the influence of Zn and water on solvation and dynamics in ethaline and reline deep eutectic solvents by 1H nuclear magnetic resonance. Physical chemistry chemical physics : PCCP 2021.

- Wang J, Qin C, Xu B, Yan L. Fast Dissolution of Chitin in Amino Acids Based Deep Eutectic Solvents Under the Assistance of Microwave. Macromol Rapid Commun 2024: e2400685.

- Zhang H, Lang J, Lan P, Yang H, Lu J, Wang Z. Study on the Dissolution Mechanism of Cellulose by ChCl-Based Deep Eutectic Solvents. Materials 2020; 13.

- Li L, Zhang M, Feng Y, Zhang X, Xu F. Deep eutectic solvent (TMAH·5H2O/Urea) with low viscosity for cellulose dissolution at room temperature. Carbohydr Polym 2024; 339: 122260. [CrossRef]

- Yang Y, Zhao L, Ren J, He B-h. Effect of Ternary Deep Eutectic Solvents on Bagasse Cellulose and Lignin Structure in Low-Temperature Pretreatment. Processes 2022.

- Ling Z, Guo Z, Huang C, Yao L, Xu F. Deconstruction of oriented crystalline cellulose by novel levulinic acid based deep eutectic solvents pretreatment for improved enzymatic accessibility. Bioresour Technol 2020; 305: 123025.

- Xie Y, Zhao J, Wang P, Ling Z, Yong Q. Natural arginine-based deep eutectic solvents for rapid microwave-assisted pretreatment on crystalline bamboo cellulose with boosting enzymatic conversion performance. Bioresour Technol 2023; 385: 129438. [CrossRef]

- Nor NAM, Mustapha WAW, Hassan O. Deep eutectic solvent (DES) as a pretreatment for oil palm empty fruit bunch (OPEFB) in production of sugar. 2015.

- Teng Z, Wang L, Huang B-N, Yu Y, Liu J, Li T. Synthesis of Green Deep Eutectic Solvents for Pretreatment Wheat Straw: Enhance the Solubility of Typical Lignocellulose. Sustainability 2022.

- Wils L, Hilali S, Boudesocque-Delaye L. Biomass Valorization Using Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents: What’s New in France? Molecules 2021. [Epub ahead of print] . [CrossRef]

- Pereda-Cruz D, Macías-Salinas R. Viscosity Modelling of Deep Eutectic Solvents via the Use of a Residual-entropy Scaling. 2023.

- Benguerba Y, Alnashef I, Erto A, Balsamo M, Ernst B. A quantitative prediction of the viscosity of amine based DESs using Sσ-profile molecular descriptors. J Mol Struct 2019.

- Liu M, Wang S, Bi W, Chen DDY. Plant polysaccharide itself as hydrogen bond donor in a deep eutectic system-based mechanochemical extraction method. Food Chem 2022; 399: 133941.

- Wang Z, Wang S, Zhang Y, Bi W. Switching from deep eutectic solvents to deep eutectic systems for natural product extraction. Green Chemical Engineering 2025; 6 (1): 36-53. [CrossRef]

- Lim JJY, Hoo DY, Tang SY, Manickam S, Yu LJ, Tan KW. One-pot extraction of nanocellulose from raw durian husk fiber using carboxylic acid-based deep eutectic solvent with in situ ultrasound assistance. Ultrason Sonochem 2024; 106: 106898. [CrossRef]

- Cysewski P, Jeliński T, Przybyłek M, Mai A, Kułak J. Experimental and Machine-Learning-Assisted Design of Pharmaceutically Acceptable Deep Eutectic Solvents for the Solubility Improvement of Non-Selective COX Inhibitors Ibuprofen and Ketoprofen. Molecules 2024; 29.

- Abbas UL, Zhang Y, Tapia J, Md S, Chen J, Shi J et al. Machine-Learning-Assisted Design of Deep Eutectic Solvents Based on Uncovered Hydrogen Bond Patterns. Engineering (Beijing, China) 2024; 39: 74 - 83.

- Mohan M, Jetti KD, Smith MD, Demerdash ON, Kidder MK, Smith JC. Accurate Machine Learning for Predicting the Viscosities of Deep Eutectic Solvents. J Chem Theory Comput 2024.

- Firouzi M, Siddiqua S, Kazemian H, Kiamahalleh MV. Green solvent-based extraction of cellulose from hemp bast fibers: From treatment efficacy to characterizations and optimization. Int J Biol Macromol 2025; 288: 138689. [CrossRef]

- Luu RK, Wysokowski M, Buehler M. Generative discovery of de novo chemical designs using diffusion modeling and transformer deep neural networks with application to deep eutectic solvents. Appl Phys Lett 2023.

- Al-Remawi M, Abdel-Rahem RA, Al-Akayleh F, Aburub F, Agha ASA. Transforming Obesity Care Through Artificial Intelligence: Real-Case Implementations and Personalized Solutions. 2025 1st International Conference on Computational Intelligence Approaches and Applications (ICCIAA). IEEE; 2025:1-5.

- Aburub F, Al-Remawi M, Abdel-Rahem RA, Al-Akayleh F, Agha ASA. AI-Driven Whole-Exome Sequencing: Advancing Variant Interpretation and Precision Medicine. 2025 1st International Conference on Computational Intelligence Approaches and Applications (ICCIAA). IEEE; 2025:1-5.

- Aburub F, Al-Akayleh F, Abdel-Rahem RA, Al-Remawi M, Agha ASA. AI-Driven Transcriptomics: Advancing Gene Expression Analysis and Precision Medicine. 2025 1st International Conference on Computational Intelligence Approaches and Applications (ICCIAA). IEEE; 2025:1-5.

- Al-Akayleh F, Abdel-Rahem RA, Al-Remawi M, Aburub F, Al-Adham IS, Agha ASA. AI-Driven Tools and Methods for Wound Healing: Towards Precision Wound Care and Optimized Outcomes. 2025 1st International Conference on Computational Intelligence Approaches and Applications (ICCIAA). IEEE; 2025:01-05.

- Al-Akayleh F, Al-Remawi M, Abdel-Rahem RA, Al-Adham IS, Aburub F, Agha ASA. AI-Driven Strategies in Prebiotic Research: Addressing Challenges and Advancing Human Health. 2025 1st International Conference on Computational Intelligence Approaches and Applications (ICCIAA). IEEE; 2025:1-5.

- Al-Remawi M, Aburub F, Al-Akayleh F, Abdel-Rahem RA, Agha ASA. Artificial Intelligence in Lipidomics: Advancing Biomarker Discovery, Pathway Analysis, and Precision Medicine. 2025 1st International Conference on Computational Intelligence Approaches and Applications (ICCIAA). IEEE; 2025:01-05.

- Al-Akayleh F, Ali Agha AS, Abdel Rahem RA, Al-Remawi M. A mini review on the applications of artificial intelligence (AI) in surface chemistry and catalysis. Tenside Surfactants Detergents 2024; 61 (4): 285-296.

- Al-Akayleh F, Agha ASA. Trust, ethics, and user-centric design in AI-integrated genomics. 2024 2nd International Conference on Cyber Resilience (ICCR). IEEE; 2024:1-6.

- Al-Remawi M, Agha ASA, Al-Akayleh F, Aburub F, Abdel-Rahem RA. Artificial intelligence and machine learning techniques for suicide prediction: Integrating dietary patterns and environmental contaminants. Heliyon 2024.

- Ghunaim L, Agha ASAA, Aburjai T. Integrating artificial intelligence and advanced genomic technologies in unraveling autism spectrum disorder and gastrointestinal comorbidities: a multidisciplinary approach to precision medicine. Jordan Journal of Pharmaceutical Sciences 2024; 17 (3): 567-581.

- Al-Akayleh F, Al-Remawi M, Agha ASA. AI-driven physical rehabilitation strategies in post-cancer care. 2024 2nd International Conference on Cyber Resilience (ICCR). IEEE; 2024:1-6.

- Aburub F, Agha ASA. AI-driven psychological support and cognitive rehabilitation strategies in post-cancer care. 2024 2nd International Conference on Cyber Resilience (ICCR). IEEE; 2024:1-6.

- Liu Y, Kashima H. Chemical property prediction under experimental biases. Sci Rep 2020; 12.

- Jia X, Lynch A, Huang Y, Danielson ML, Lang’at I, Milder A et al. Anthropogenic biases in chemical reaction data hinder exploratory inorganic synthesis. Nature 2019; 573: 251 - 255.

- Ghunaim L, Agha ASA, Al-Samydai A, Aburjai T. The Future of Pediatric Care: AI and ML as Catalysts for Change in Genetic Syndrome Management. Jordan Medical Journal 2024; 58 (4).

- Isci A, Kaltschmitt M. Recovery and recycling of deep eutectic solvents in biomass conversions: a review. Biomass Conversion and Biorefinery 2021; 12: 197 - 226.

- Wang D, Zhang M, Lim Law C, Zhang L. Natural deep eutectic solvents for the extraction of lentinan from shiitake mushroom: COSMO-RS screening and ANN-GA optimizing conditions. Food Chem 2023; 430: 136990.

- Panić M, Andlar M, Tišma M, Rezić T, Šibalić D, Cvjetko Bubalo M et al. Natural deep eutectic solvent as a unique solvent for valorisation of orange peel waste by the integrated biorefinery approach. Waste management 2020; 120: 340-350.

| Source | Polysaccharide Type | DES Extraction Method/System | Benefit/Remarks vs. Conventional | Reference |

| Dioscorea opposita | Crude polysaccharides | Choline chloride + 1,4-butanediol (ultrasound-assisted) | Higher yield than hot water or water-ultrasound extraction | [8] |

| Ganoderma lucidum | β-glucan-rich polysaccharides | Choline chloride + guaiacol + lactic acid (ternary DES) | 94.7 mg/g yield; stable reuse; superior due to strong hydrogen bonding | [9] |

| Saccharina japonica | Alginate, Fucoidan | DES + subcritical water hydrolysis | High yields of alginate (28.1%) and fucoidan (14.9%) | [10] |

| Sargassum horneri | Sulfated polysaccharides | Choline chloride + 1,2-propanediol (ultrasound-assisted) | Better removal of impurities and higher antioxidant activity | [11] |

| Fucus vesiculosus | Sulfated fucose-rich polysaccharides | Microwave-assisted DES: choline chloride + 1,4-butanediol | 116.3 mg/g yield; strong antioxidant and anticancer activity | [12] |

| Poria cocos | (1→3)-β-D-glucan-rich branched glucans | Choline chloride + oxalic acid DES | 8.6x yield over hot water; good recyclability | [13] |

| Ganoderma lucidum | Acidic heteropolysaccharides composed primarily of glucose, galactose, and glucuronic acid | Temperature-responsive DES | Polysaccharides recovered at UCST; green and recyclable system | [14] |

| Maca | Crude maca polysaccharides (unspecified heteropolysaccharide mixture) | Choline chloride + urea (ultrasound-assisted) | 2x yield over water; strong antioxidant and prebiotic benefits | [15] |

| Polygonatum kingianum | Crude polysaccharide (uncharacterized) | Choline chloride: glycerol (1:2), NADES | 2.5x higher yield than water; boosts IL-6 and iNOS in macrophages | [16] |

| Pericarpium Citri Reticulatae | Acidic heteropolysaccharide (PCRPs-1) rich in galactose, rhamnose, and uronic acids | Ultrasound-assisted DES | 5.41% yield vs. 3.92% (water); antioxidant and antidiabetic effects | [17] |

| Abalone viscera | Marine-derived acidic heteropolysaccharide rich in galactose and glucuronic acid (AVP) | Choline chloride + ethylene glycol (1:3 molar ratio), 25% water, ultrasound-assisted | Higher yield (17.32%), enhanced glucuronic acid content, lower Mw (53.33 kDa), stronger antioxidant activity than hot water extraction | [18] |

| Black truffle | Crude black truffle polysaccharide (uncharacterized) | Betaine + citric acid NADES (ultrasound-assisted) | 11x yield over ethanol; antioxidant and anti-aging bioactivity | [19] |

| Dandelion | Crude dandelion polysaccharides (likely inulin-type fructans, arabinogalactans, and/or pectic polysaccharides) | Ultrasound-assisted NADES (Choline chloride:Oxalic acid 1:2; 60% water) | Higher yield (68.5 mg/g) and purity (0.88 mg/mg); outperforming traditional methods; green and cost-effective | [20] |

| Lentinus edodes | Heteropolysaccharide (Glucose:Galactose:Mannose ≈ 32.9:1:2.54) | Subcritical Water Extraction (SWE) + ChCl–Malonate (1:2) DES | 19.2% more yield than SWE; better antioxidant profile | [21] |

| Acanthopanax senticosus | Glucose-based heteropolysaccharide | 3c-DES (betaine:triethanolamine:MgCl₂·6H₂O = 1:4:0.08, molar ratio); ethanol precipitation | Simultaneous extraction of saponins and polysaccharides | [22] |

| Lilium lancifolium | Crude heteropolysaccharides (glucose-, galactose-, arabinose-, mannose-containing) | Choline chloride–ethylene glycol (ChEtgly, 1:2) with 20% water, ultrasound-assisted at 50 °C for 40 min | Comparable yield to hot water extraction in 1/3 the time; simultaneous phenolic acid co-extraction; green solvent advantage | [23] |

| Eucommia ulmoides | Acidic heteropolysaccharides (mannose, rhamnose, galacturonic) | Choline chloride + oxalic acid (ultrasound-assisted) | 2.3x yield vs. water; strong antioxidant and enzyme inhibition | [24] |

| Dendrobium devonianum | Glucose-based heteropolysaccharide (α-/β-glucans) | Mechanochemical self-forming DESys | No external HBD needed; high efficiency and bioactivity | [25] |

| Polygonatum sibiricum | Galactose- and mannose-rich heteropolysaccharide (DPSP-3) | Choline chloride:oxalic acid (1:1, m/m) DES at 70 °C for 40 min | 15.62% yield (1.53× higher than water extraction); enriched in galactose (65.75%) and mannose (19.76%); improved immunomodulatory activity (ROS, NO, IL-6, TNF-α release in RAW264.7) | [26] |

| Lycium barbarum | Low-MW heteropolysaccharides (glucose-rich LBP) | Temperature-switchable DES (tetracaine:lauric acid, 1:1; 70 wt%) | 465 mg/g yield; recyclable; strong antioxidant profile | [27] |

| Anji white tea | Acidic arabinogalactan-type heteropolysaccharide | Choline chloride + 1,6-hexanediol (ultrasound-assisted) | Higher yield and antioxidant activity vs. water | [28] |

| Grape seed | Heteropolysaccharide (mannose, glucose, galactose, arabinose) | pH-switchable DES: dodecanoic acid + octanoic acid | 98 mg/g yield; reusable 25x; green alternative to t-butanol | [29] |

| Acanthopanax senticosus root | Acidic heteropolysaccharide (rich in galacturonic acid, arabinose, galactose) | L-malic acid + L-proline (ultrasound-assisted) | 2.6x higher yield than hot water; strong antioxidant activity | [30] |

| Chrysanthemum morifolium | Pectin (RG-I-rich) | DES (urea:choline chloride or 1,2-PG:ChCl) | D2: 83.5% RG-I domain; low GalA; enhanced prebiotic activity vs. inulin | [31] |

| Morchella importuna | Acidic heteropolysaccharide (GlcN, Gal, Glc, Man; 0.39:1.88:3.82:3.91) | Choline chloride + oxalic acid (2:1), 90% H₂O | 4.5× higher yield than HWE; higher carbohydrate (85.3%) and sulfate content (34.2%); enhanced antioxidant and α-glucosidase inhibitory effects | [32] |

| Astragalus membranaceus | Astragalus polysaccharides (APS); heteropolysaccharides containing Glc, Gal, Ara, Rha, Man | Choline chloride + oxalic acid (ultrasound-assisted) | Increased yield, reduced impurities vs. conventional | [33] |

| Camellia oleifera | Pectic-like heteropolysaccharide (rich in Ara, Glc, Gal, Rha, GalA, GlcA) | Choline chloride + propionic acid + 1,3-butanediol (DES-28; ternary) | 1.5× higher yield than hot water; enhanced antioxidant and hypoglycemic activity | [34] |

| Bletilla striata | Glucomannan | Choline chloride + urea | ↑Yield (36.77%), ↑Antioxidant activity (DPPH, ABTS, FRAP), recyclable DES | [35] |

| Schisandra chinensis | Galacturonic acid-rich pectic polysaccharide | Ethanolamine:4-Methoxyphenol (1:1) | 1.39× higher yield vs. water; recyclable TRDES; simultaneous lignanoid extraction | [36] |

| Soluble Substances | Mechanism/Insight | Reference |

| Cu, Fe, Pb, Zn (oxides, sulfates, sulfides) | Sulfates dissolve best; solubility ~100× higher due to enhanced coordination in DES. | [49] |

| LiCoO₂, Lithium cobalt oxide | Reductive dissolution via ascorbic acid and PEG-based DES with 84.2% Co leaching. | [50] |

| Lipids, proteins, carbohydrates | NaDES polarity and viscosity enhance biomolecule extraction. | [51] |

| DNA, starch, gluten, bioactives | Natural DESs dissolve biopolymers via extensive hydrogen bonding networks. | [52] |

| CuO, ZnO, MgO, CaO, Fe₂O₃ | Thermodynamic favorability and morphology changes improve solubility. | [53] |

| Cellulose | Partial bonding and enhanced H-bonding increase cellulose solubility in ChCl–resorcinol DES. | [54] |

| Uranium oxide (UO₃) | Coordination with TOPO and HTTA in hydrophobic DESs achieves high solubility. | [55] |

| Toluene (reaction medium) | DESs activate H₂O₂ via H-bonding and low viscosity, enhancing oxidation reactions. | [56] |

| UO₂, U₃O₈, UO₃ | Strong hydrogen bonding in PTSA:ChCl DES enables uranium oxide dissolution. | [57] |

| CO₂, SO₂, H₂S, aromatic bioactives | DESs solvate via selective polarity and hydrogen bonding matched to target compounds. | [58] |

| PbO, CuO, Fe₂O₃, ZnO | Acidic DESs use H-bond networks and phase behavior to dissolve metal oxides. | [59] |

| Metal oxides, salts, polar organics | Ionic interactions and hydrogen bonds enhance solubility of diverse substances. | [60] |

| Chitin | Novel DESs using TMBAC and acids dissolved chitin up to 12% and enhanced enzymatic hydrolysis 2×. | [61] |

| CnTAB surfactants (micelles) | Micelle formation in DESs depends on solvent microstructure and hydrogen bonding. | [62] |

| HgO, HgCl₂ | Complete dissociation via Cl⁻ coordination in DES; H-bond donors don’t replace chloride ligands. | [63] |

| Metal oxides, drugs, flavonoids, phenols | Broad solubility via strong hydrogen bonding, high polarity, and solvent customization. | [64] |

| Fe₃O₄, CuO, ZnO, PbO | Chloroacetic acid DESs with ammonium bromides dissolve oxides through optimized H-bonding. | [65] |

| Rutin | High solubility in ChCl:propanediol/urea DES due to hydrogen bonding and polarity. | [66] |

| PbO | [PbO·Cl·EG]⁻ species formation drives dissolution in ChCl–EG DES. | [67] |

| Keratin (animal hair) | Sulfur-containing DESs disrupt protein structure, achieving up to 79% solubility. | [68] |

| Metal oxides from lithium-ion batteries | DES decomposition products (e.g., Cl₃⁻) promote oxidative dissolution. | [69] |

| DNA | Solubility depends on hydrogen bonding strength and ionic conductivity in DES. | [70] |

| Bioactive pharmaceutical ingredients | DES polarity and hydrogen bonding tailored to drug properties, improving solubility. | [71] |

| Metal salts, oxides, phosphates | Solubility varies with DES pH and polarity; acidic DESs dissolve oxides effectively. | [72] |

| MgFe₂O₄, ZnFe₂O₄, CoFe₂O₄, NiFe₂O₄ | DESs enable low-temp synthesis and precursor dissolution for ferrite nanoparticles. | [73] |

| Co, Cu, Zn, Fe, Ni, Mn oxides | Temp/time-dependent coordination and solubilization in choline chloride–acid DES. | [74] |

| Cellulose | ZnCl₂ hydrate–acrylic acid DES disrupts cellulose H-bonding for efficient dissolution. | [75] |

| APIs (Fluconazole, mometasone furoate, Risperidone, diclofenac diethylamine, azelaic acid, tadalafil) | THEDES systems can dissolve APIs by transforming the crystalline drug into a supramolecular liquid mixture. | [40,41,42,43,44,45,46] |

| Polysaccharide | Biological Source | Dominant Domain(s) | Structural Features | Implication for DES Extraction | Key Reference |

| Cellulose | Plant cell walls | Crystalline > Interfacial | Linear β(1→4)-Glc; extensive hydrogen bonding; microfibrillar | Requires strong HBAs or heat/ultrasound; limited solubility in mild DESs | [112,113,114] |

| Pectin (RG-I, HG) | Plant middle lamella | Amorphous | Galacturonic acid-rich; HG linear, RG-I branched | Readily extracted by acidic DESs; mild DESs preserve structure, promote bioactivity | [104,105] |

| Hemicellulose | Secondary plant walls | Amorphous + Interfacial | Heterogeneous; short chains; variable composition | Extractable under mild DESs; solubility depends on sugar composition and structure | [106] |

| Chitin | Fungi, crustaceans | Crystalline | β(1→4)-GlcNAc; highly ordered, strong H-bonding | Requires acidic/basic DESs; needs thermal/ultrasonic pretreatment | [61] |

| Chitosan | Deacetylated chitin | Amorphous + Interfacial | Linear, partially cationic; degree of deacetylation influences solubility | Soluble in acidic DESs (e.g. choline chloride–lactic acid); forms gels and films | [115] |

| Starch (Amylose) | Plant storage tissues | Semi-crystalline | Linear α(1→4)-Glc; helical; forms double helices | Requires thermal gelatinization to be solubilized in DESs | [116] |

| Starch (Amylopectin) | Plant storage tissues | Amorphous (contributes to semi-crystalline lamellae in native starch) | Highly branched α(1→4)/α(1→6) Glc | Easily solubilized by polar DESs under mild conditions | [117] |

| Inulin | Chicory, dahlia | Amorphous | Linear and branched fructans (β(2→1)-linked) | Fully soluble in polar DESs; enhances bioactive film formation | [107,108] |

| β-Glucan | Oats, barley, yeast | Amorphous | Mixed β(1→3)/(1→4)-Glc; gel-forming | Soluble in neutral DESs; used in functional food and pharma | [118] |

| Xanthan gum | Bacterial EPS | Amorphous | β(1→4)-linked glucose backbone with charged side chains | Highly soluble in DESs; enables shear-thinning formulations | [119] |

| Alginate | brown seaweed | Amorphous | Linear mannuronic and guluronic acid blocks; polyanionic | Acidic DESs shield charges and promote solubilization | [120] |

| Fucoidan | brown seaweed | Amorphous | Sulfated, branched α(1→3)/α(1→4)-L-fucose | Soluble in ionic and polar DESs; mild extraction preserves bioactivity | [10] |

| Glucomannan | porang (Amorphophallus muelleri Blume) | Amorphous | Linear β(1→4)-linked glucose and mannose | Highly extractable under mild polar DESs | [121] |

| Pullulan | Fungi (Aureobasidium) | Amorphous | Linear α(1→6)-linked maltotriose units; non-ionic and water-soluble | Compatible with polar DESs; maintains solubility across solvents | [122] |

| Galactomannan | Legumes (e.g., guar) | Amorphous | β(1→4)-linked mannan with α(1→6)-galactose side chains | Easily solubilized in polar DESs; can be enzymatically modified | [123] |

| Levan | Bacterial (e.g., Bacillus) | Amorphous | β(2→6)-linked fructose units; highly branched and water-soluble | Readily soluble in polar DESs; useful in prebiotic applications | [124] |

| Dextran | Bacterial (Leuconostoc) | Amorphous | Linear α(1→6)-Glc backbone with α(1→3/1→4) branches | Soluble in mild, neutral DESs; applicable in food and pharma | [125] |

| Carrageenan | Red algae | Amorphous | Sulfated galactans; alternating α(1→3)/β(1→4)-linked units; gelling | Soluble in ionic DESs; gelation influenced by ions and solvent polarity | [126] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).