Submitted:

05 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Experimental Section

2.1. Materials

2.2. Synthesis of Catalysts

2.3. Characterization of Catalyst

2.4. Photocatalytic Activity

2.5. Antibacterial Activity

3. Results and Discussion

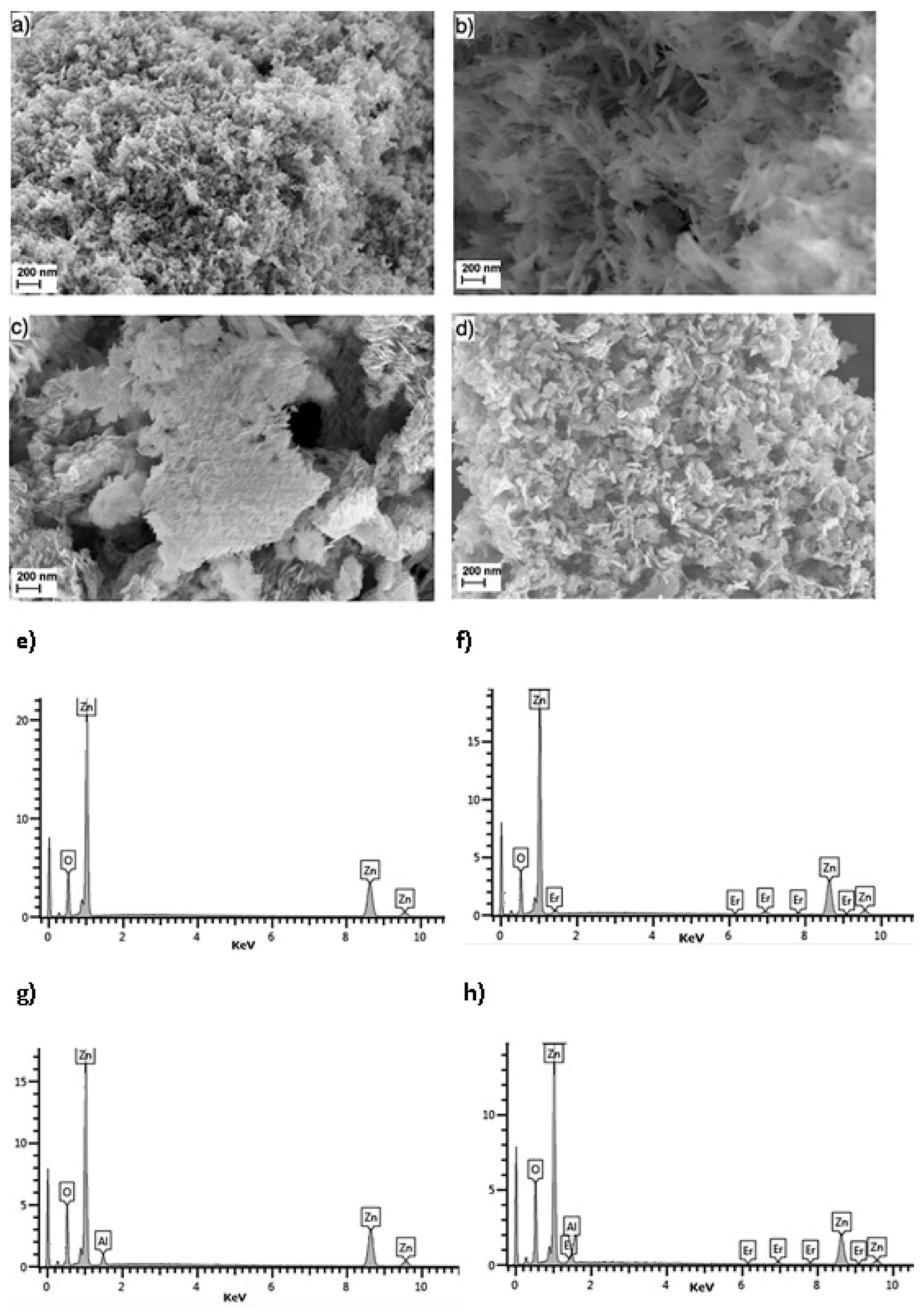

3.1. Morphology of Composites

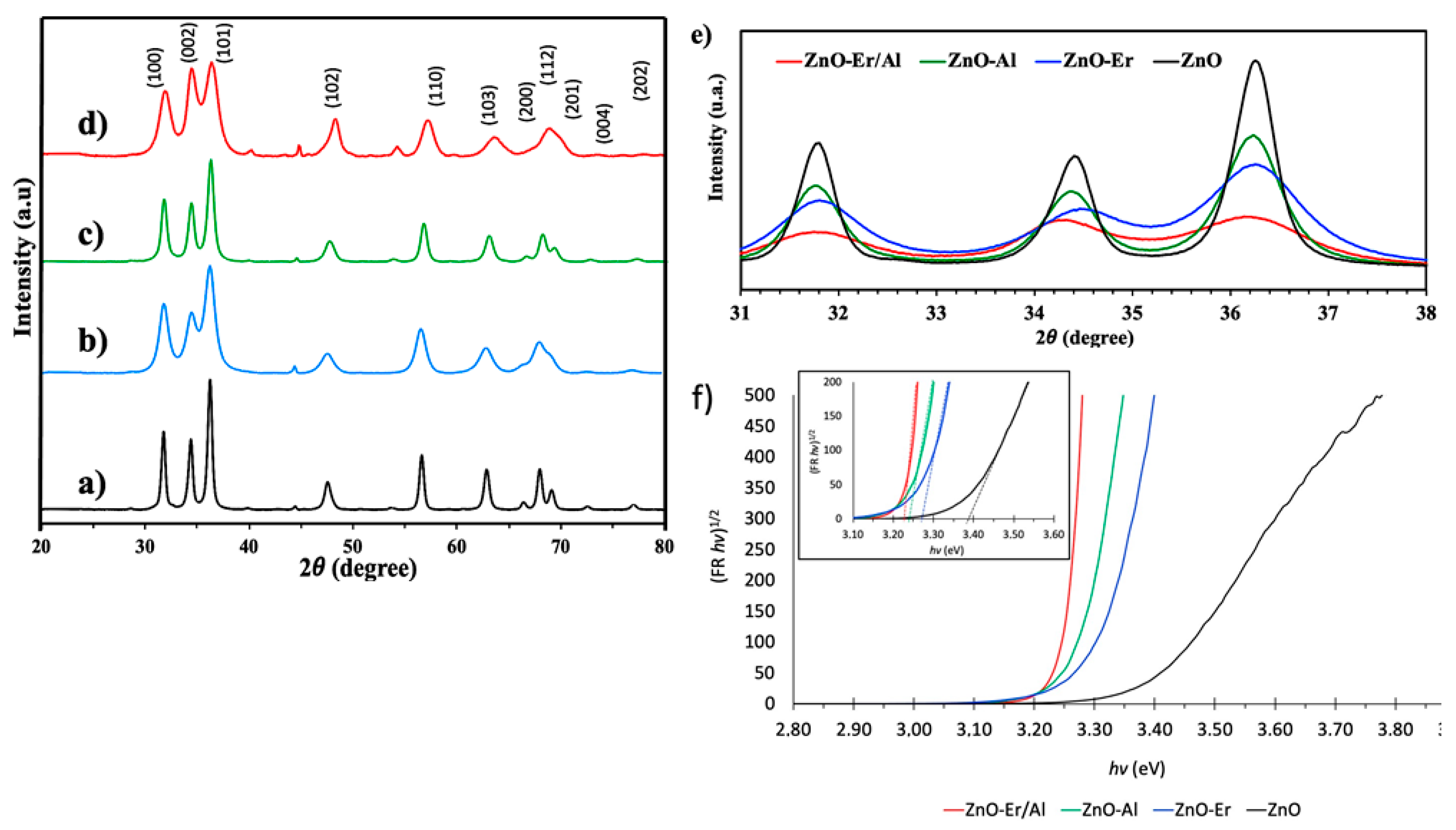

3.2. XRD Analysis

3.3. Optical Properties

3.4. Catalyst Dosage on Metil Orange Degradation

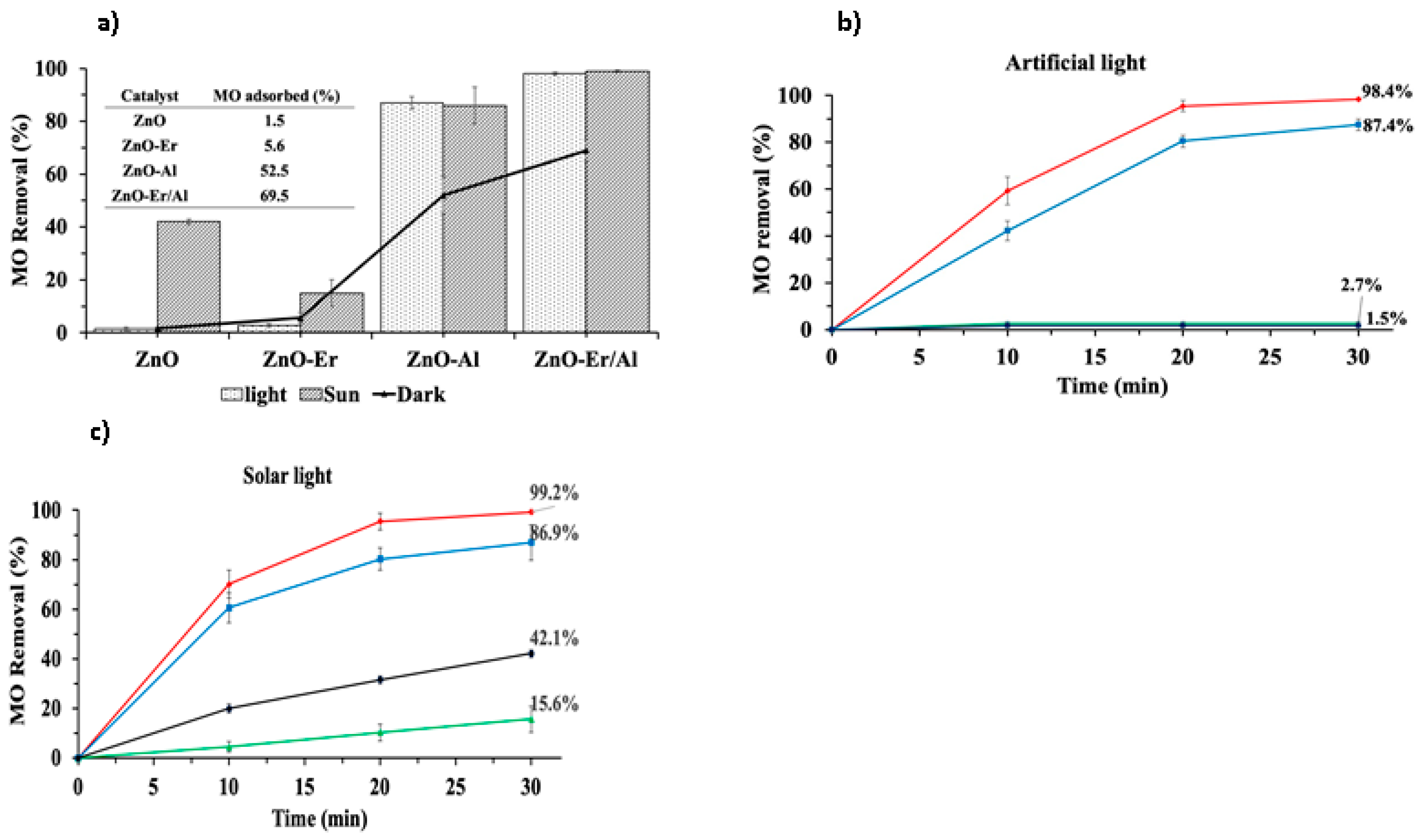

3.5. Photocatalytic Performance of Synthesized Nanoparticles

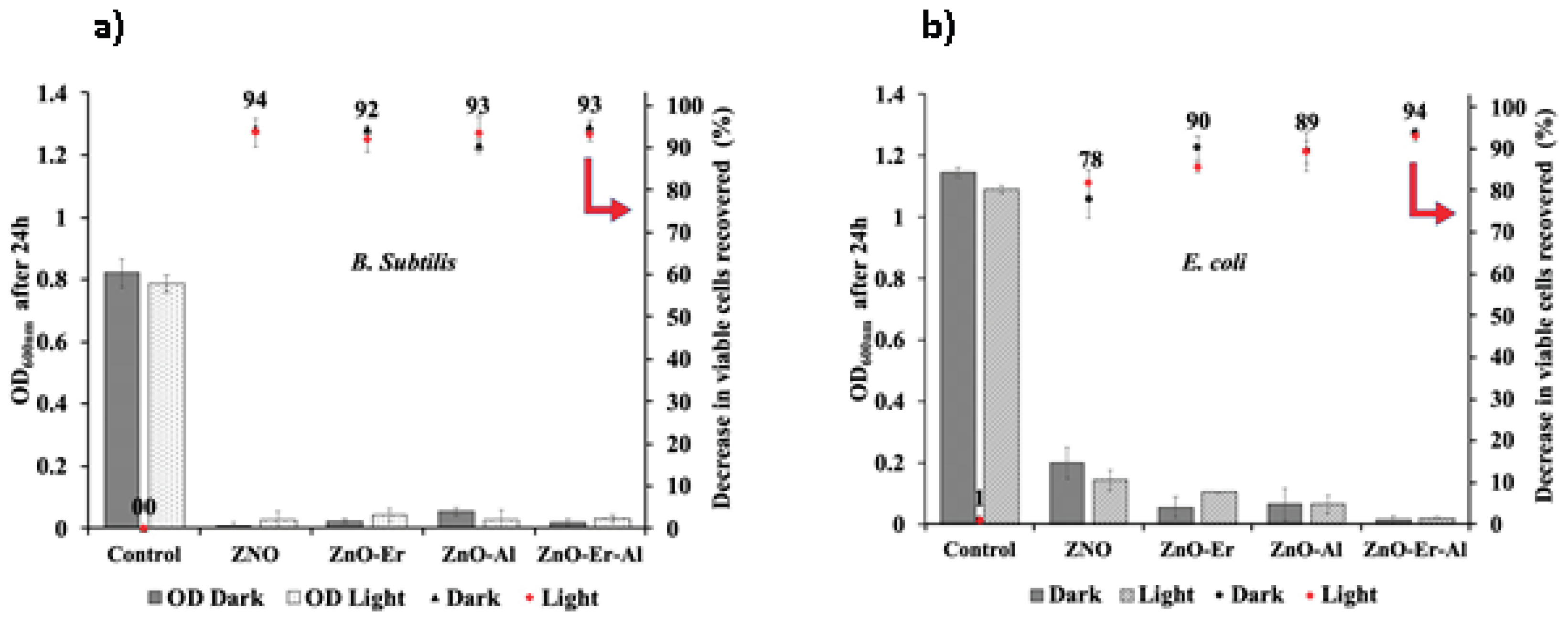

3.6. Determination of Antibacterial Activity of Doped and Undoped ZnO Samples

4. Conclusions

Acknowledgments

References

- N. Singhal, S. Selvaraj, Y. Sivalingam, G. Venugopal, Study of photocatalytic degradation efficiency of rGO/ZnO nano-photocatalyst and their performance analysis using scanning Kelvin probe, J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10 (2022) 107293. [CrossRef]

- S. Anandan, V. Kumar Ponnusamy, M. Ashokkumar, A review on hybrid techniques for the degradation of organic pollutants in aqueous environment, Ultrason. Sonochem. 67 (2020). [CrossRef]

- H. Zhu, R. Jiang, Y. Fu, Y. Guan, J. Yao, L. Xiao, G. Zeng, Effective photocatalytic decolorization of methyl orange utilizing TiO 2/ZnO/chitosan nanocomposite films under simulated solar irradiation, Desalination. 286 (2012) 41–48. [CrossRef]

- Z. Mirzaeifard, Z. Shariatinia, M. Jourshabani, S.M. Rezaei Darvishi, ZnO Photocatalyst Revisited: Effective Photocatalytic Degradation of Emerging Contaminants Using S-Doped ZnO Nanoparticles under Visible Light Radiation, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 59 (2020) 15894–15911. [CrossRef]

- M.A. Oturan, J.J. Aaron, Advanced oxidation processes in water/wastewater treatment: Principles and applications. A review, Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 44 (2014) 2577–2641. [CrossRef]

- G.K. Weldegebrieal, Synthesis method, antibacterial and photocatalytic activity of ZnO nanoparticles for azo dyes in wastewater treatment: A review, Inorg. Chem. Commun. 120 (2020). [CrossRef]

- L. Pan, G.Q. Shen, J.W. Zhang, X.C. Wei, L. Wang, J.J. Zou, X. Zhang, TiO2-ZnO Composite Sphere Decorated with ZnO Clusters for Effective Charge Isolation in Photocatalysis, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 54 (2015) 7226–7232. [CrossRef]

- A.H. Zyoud, A. Zubi, S. Hejjawi, S.H. Zyoud, M.H. Helal, S.H. Zyoud, N. Qamhieh, A.R. Hajamohideen, H.S. Hilal, Removal of acetaminophen from water by simulated solar light photodegradation with ZnO and TiO2nanoparticles: Catalytic efficiency assessment for future prospects, J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 8 (2020) 104038. [CrossRef]

- D. Tekin, H. Kiziltas, H. Ungan, Kinetic evaluation of ZnO/TiO2 thin film photocatalyst in photocatalytic degradation of Orange G, J. Mol. Liq. 306 (2020). [CrossRef]

- E.S. Araújo, B.P. Da Costa, R.A.P. Oliveira, J. Libardi, P.M. Faia, H.P. De Oliveira, TiO2/ZnO hierarchical heteronanostructures: Synthesis, characterization and application as photocatalysts, J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 4 (2016) 2820–2829. [CrossRef]

- K. Rajeshwar, M.E. Osugi, W. Chanmanee, C.R. Chenthamarakshan, M.V.B. Zanoni, P. Kajitvichyanukul, R. Krishnan-Ayer, Heterogeneous photocatalytic treatment of organic dyes in air and aqueous media, J. Photochem. Photobiol. C Photochem. Rev. 9 (2008) 171–192. [CrossRef]

- L.K. Adams, D.Y. Lyon, P.J.J. Alvarez, Comparative eco-toxicity of nanoscale TiO2, SiO2, and ZnO water suspensions, Water Res. 40 (2006) 3527–3532. [CrossRef]

- S. Balta, A. Sotto, P. Luis, L. Benea, B. Van der Bruggen, J. Kim, A new outlook on membrane enhancement with nanoparticles: The alternative of ZnO, J. Memb. Sci. 389 (2012) 155–161. [CrossRef]

- J. Yoon, S.-G. Oh, Synthesis of amine modified ZnO nanoparticles and their photocatalytic activities in micellar solutions under UV irradiation, J. Ind. Eng. Chem. 96 (2021) 390–396. [CrossRef]

- R. Daghrir, P. Drogui, D. Robert, Modified TiO2 for environmental photocatalytic applications: A review, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 52 (2013) 3581–3599. [CrossRef]

- C. Gomez-Solís, J.C. Ballesteros, L.M. Torres-Martínez, I. Juárez-Ramírez, L.A. Díaz Torres, M. Elvira Zarazua-Morin, S.W. Lee, Rapid synthesis of ZnO nano-corncobs from Nital solution and its application in the photodegradation of methyl orange, J. Photochem. Photobiol. A Chem. 298 (2015) 49–54. [CrossRef]

- I. Ahmad, S. Shukrullah, M.Y. Naz, H.N. Bhatti, M. Ahmad, E. Ahmed, S. Ullah, M. Hussien, Recent Progress in Rare Earth Oxides and Carbonaceous Materials Modified ZnO Heterogeneous Photocatalysts for Environmental and Energy Applications, J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 10 (2022) 107762. [CrossRef]

- J. de L. Andrade, A.G. Oliveira, V.V.G. Mariucci, A.C. Bento, M.V. Companhoni, C.V. Nakamura, S.M. Lima, L.H. da C. Andrade, J.C.G. Moraes, A.A.W. Hechenleitner, E.A.G. Pineda, D.M.F. de Oliveira, Effects of Al3+ concentration on the optical, structural, photocatalytic and cytotoxic properties of Al-doped ZnO, J. Alloys Compd. 729 (2017) 978–987. [CrossRef]

- K.M. Lee, C.W. Lai, K.S. Ngai, J.C. Juan, Recent developments of zinc oxide based photocatalyst in water treatment technology: A review., Water Res. 88 (2016) 428–448. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, S. Dong, X. Zhou, L. Yan, G. Chen, D. Zhou, A facile one-pot synthesis of Er-Al co-doped ZnO nanoparticles with enhanced photocatalytic performance under visible light, Mater. Lett. 143 (2015) 312–314. [CrossRef]

- M. Prathap Kumar, G.A. Suganya Josephine, G. Tamilarasan, A. Sivasamy, J. Sridevi, Rare earth doped semiconductor nanomaterials and its photocatalytic and antimicrobial activities, J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 6 (2018) 3907–3917. [CrossRef]

- R. Mahdavi, S.S.A. Talesh, Sol-gel synthesis , structural and enhanced photocatalytic performance of Al doped ZnO nanoparticles, 28 (2017) 1418–1425.

- X. Chen, Z. Wu, D. Liu, Z. Gao, Preparation of ZnO Photocatalyst for the Efficient and Rapid Photocatalytic Degradation of Azo Dyes, Nanoscale Res. Lett. 12 (2017) 4–13. [CrossRef]

- D. Rajamanickam, M. Shanthi, Photocatalytic degradation of an organic pollutant, 4-nitrophenol by zinc oxide - UV process, Res. J. Chem. Environ. 9 (2012) S1858–S1868.

- Ambient secretary government of Quito Ecuador, Ambient secretary government of Quito Ecuador, (2020).

- N.K. Divya, P.P. Pradyumnan, Solid state synthesis of erbium doped ZnO with excellent photocatalytic activity and enhanced visible light emission, Mater. Sci. Semicond. Process. 41 (2016) 428–435.

- M. Bououdina, S. Azzaza, R. Ghomri, M.N. Shaikh, J.H. Dai, Y. Song, W. Song, W. Cai, M. Ghers, Structural and magnetic properties and DFT analysis of ZnO:(Al,Er) nanoparticles, RSC Adv. 7 (2017) 32931–32941. [CrossRef]

- R. Ghomri, M.N. Shaikh, M.I. Ahmed, W. Song, W. Cai, M. Bououdina, M. Ghers, Pure and (Er, Al) co-doped ZnO nanoparticles: synthesis, characterization, magnetic and photocatalytic properties, J. Mater. Sci. Mater. Electron. 29 (2018) 10677–10685. [CrossRef]

- P. Makuła, M. Pacia, W. Macyk, How To Correctly Determine the Band Gap Energy of Modified Semiconductor Photocatalysts Based on UV-Vis Spectra, J. Phys. Chem. Lett. 9 (2018) 6814–6817. [CrossRef]

- B.D. Viezbicke, S. Patel, B.E. Davis, D.P. Birnie, Evaluation of the Tauc method for optical absorption edge determination: ZnO thin films as a model system, Phys. Status Solidi Basic Res. 252 (2015) 1700–1710. [CrossRef]

- S.G. Ullattil, P. Periyat, B. Naufal, M.A. Lazar, Self-Doped ZnO Microrods - High Temperature Stable Oxygen Deficient Platforms for Solar Photocatalysis, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 55 (2016) 6413–6421. [CrossRef]

- M.R.A. Kumar, C.R. Ravikumar, H.P. Nagaswarupa, B. Purshotam, B.A. Gonfa, H.C.A. Murthy, F.K. Sabir, S. Tadesse, Evaluation of bi-functional applications of ZnO nanoparticles prepared by green and chemical methods, J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 7 (2019) 103468. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhang, Y. Chen, S. Zhang, C. Qiu, High photocatalytic performance of high concentration Al-doped ZnO nanoparticles, Sep. Purif. Technol. 172 (2017) 236–241. [CrossRef]

- A.W. Xu, Y. Gao, H.Q. Liu, The preparation, characterization, and their photocatalytic activities of rare-earth-doped TiO2 nanoparticles, J. Catal. 207 (2002) 151–157. [CrossRef]

- S. Tao, M. Yang, H. Chen, S. Zhao, G. Chen, Continuous Synthesis of Ag/AgCl/ZnO Composites Using Flow Chemistry and Photocatalytic Application, Ind. Eng. Chem. Res. 57 (2018) 3263–3273. [CrossRef]

- M. Fu, Y. Li, S. Wu, P. Lu, J. Liu, F. Dong, Sol-gel preparation and enhanced photocatalytic performance of Cu-doped ZnO nanoparticles, Appl. Surf. Sci. 258 (2011) 1587–1591. [CrossRef]

- S. Dong, K. Xu, J. Liu, H. Cui, Photocatalytic performance of ZnO:Fe array films under sunlight irradiation, Phys. B Condens. Matter. 406 (2011) 3609–3612. [CrossRef]

- A. Layek, S. Banerjee, B. Manna, A. Chowdhury, Synthesis of rare-earth doped ZnO nanorods and their defect-dopant correlated enhanced visible-orange luminescence, RSC Adv. 6 (2016) 35892–35900. [CrossRef]

- L. Zhang, Y. Jiang, Y. Ding, M. Povey, D. York, Investigation into the antibacterial behaviour of suspensions of ZnO nanoparticles (ZnO nanofluids), J. Nanoparticle Res. 9 (2007) 479–489. [CrossRef]

- K.R. Raghupathi, R.T. Koodali, A.C. Manna, Size-dependent bacterial growth inhibition and mechanism of antibacterial activity of zinc oxide nanoparticles, Langmuir. 27 (2011) 4020–4028. [CrossRef]

- A. Prasert, S. Sontikaew, D. Sriprapai, S. Chuangchote, Polypropylene/ZnO Nanocomposites: Mechanical Properties, Photocatalytic Dye Degradation, and Antibacterial Property, Materials (Basel). 13 (2020) 914. [CrossRef]

- R. Bahamonde Soria, J. Zhu, I. Gonza, B. Van der Bruggen, P. Luis, Effect of (TiO2: ZnO) ratio on the anti-fouling properties of bio-inspired nanofiltration membranes, Sep. Purif. Technol. 251 (2020). [CrossRef]

- T. Munawar, S. Yasmeen, F. Mukhtar, M.S. Nadeem, K. Mahmood, M. Saqib Saif, M. Hasan, A. Ali, F. Hussain, F. Iqbal, Zn0.9Ce0.05M0.05O (M = Er, Y, V) nanocrystals: Structural and energy bandgap engineering of ZnO for enhancing photocatalytic and antibacterial activity, Ceram. Int. 46 (2020) 14369–14383. [CrossRef]

- V. Saxena, L.M. Pandey, Synthesis, characterization and antibacterial activity of aluminum doped zinc oxide, Mater. Today Proc. 18 (2019) 1388–1400. [CrossRef]

- K. Dědková, Kuzníková, L. Pavelek, K. Matějová, J. Kupková, K. Čech Barabaszová, R. Váňa, J. Burda, J. Vlček, D. Cvejn, J. Kukutschová, Daylight induced antibacterial activity of gadolinium oxide, samarium oxide and erbium oxide nanoparticles and their aquatic toxicity, Mater. Chem. Phys. 197 (2017) 226–235. [CrossRef]

| Sample | at% Er3+ | at % Al3+ |

| ZnO | 0 | 0 |

| ZnO-Er | 1.5 | 0 |

|

ZnO-Al ZnO-Er/Al |

0 1.5 |

5 5 |

| Sample | at% | |||

| Zn | O | Er | Al | |

| ZnO | 56.61 | 43.24 | 0 | 0 |

| ZnO-Er | 50.42 | 47.32 | 1.52 | 0 |

| ZnO-Al | 50.10 | 44.80 | 0 | 5.06 |

| ZnO-Er/Al | 44.74 | 48.51 | 1.46 | 5.15 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).