1. Introduction

Interstitial lung disease (ILD) is a heterogenous group of disorders that cause inflammation and fibrosis in the lungs. Over 200 causes are described from very rare diseases to more common such as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, sarcoidosis or autoimmune diseases. These are listed in an international classification established in 2002 and revised in 2013 [

1,

2]. ILD occurs in less than 80 patients for 100,000 inhabitants [

3]. The pathophysiology of ILD is complex and different depending the etiology. It involves genetic background, environmental exposure, and autoimmune trigger. It has been demonstrated that these can lead to an acute or chronic inflammation with extracellular matrix and collagen deposition in the pulmonary interstitium, resulting in fibrosis. The initial manifestations of the disease include a progressive cough and dyspnea, which can progress to chronic respiratory failure in cases of advanced disease. This progression is secondary to impaired gas exchange and loss of lung compliance. However, the presence of acute respiratory failure (ARF) can reveal the underlying disease, necessitating admission to an intensive care unit (ICU) at the onset of the condition. In the context of patients admitted to ICU with ARF attributable to ILD, the mortality rate associated with this condition has been reported to range from 55 to 100% [

4]. The treatment of ILD is contingent upon the underlying etiology and may encompass supplemental oxygen therapy when indicated, physical therapy, and preventive measures, such as vaccines and exposure avoidance strategies [

5].

ARF complicating ILD may overlap the diagnosis of other causes of admission including an acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) [

6,

7]. These patients are considered as part of the “diagnoses not typically classified ARDS” and were historically described as “ARDS mimickers” [

8]. In a large-scale retrospective study in two French ICUs, the prevalence of ARDS mimickers was 7.5% [

9], and most of them had an ILD related to a connective tissue disease, vasculitis or drugs exposure. The management of ARDS mimickers is similar to ARDS and is based on symptomatic treatments and ventilator setting in addition to etiological treatment. Indeed, identifying the cause of ARDS in order to start the treatment at the early phase of the disease before the fibrosis develop is critical for the outcome in the ICU [

10].

Data on ARF complicating ILD are scarce, we thus undertook our study to (1) estimate the rate of ILD admitted to our ICU; (2) describe the epidemiologic features and outcome of these patients; and (3) to point the critical role of an expert team in imaging for the diagnosis of interstitial pneumonia.

2. Materials and Methods

We conducted a retrospective single center observational study from the ICU department in the secondary care general hospital of Avignon, France. The selected cases were reviewed by an expert team in ILD in the tertiary care teaching hospital of Marseille (Hôpital Nord, Assistance Publique Hôpitaux de Marseille, Aix Marseille University, Marseille, France).

From October 2017 to February 2020, we retrospectively included adult patients with ARF due to a newly diagnosed ILD. The diagnosis of ILD was made in accordance with the guidelines established by the American Thoracic Society (ATS) and the European Thoracic Society (ERS), as well as the most recent international updates to these guidelines [

1,

2,

11]. Patients should require an invasive or non-invasive mechanical ventilation to be included. A lung high-resolution computed tomography (HRCT) was required to confirm the diagnosis. Exclusion criteria were ARF due to infection or cardiac failure, patients with uncertain diagnosis of ILD defined by the international guidelines and patients with previously diagnosed chronic ILD. When the main diagnosis was ILD, patients were selected and analyzed for eligibility.

All the survivors were discharged to the department of pneumology of our hospital. Thus, we used the institutional database for assessing the medical records. The medical records were assessed in the hospital’s ICU department, and then all the data was anonymized. Organ dysfunction was evaluated with the Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment (SOFA) score [

12].

We collected data on demographics and personal medical history of all selected patients. Ventilatory parameters and the mean ratio of the oxygen pressure to the fraction of inspired oxygen ratio (PaO2:FiO2) were assessed. For patients requiring invasive mechanical ventilation, we also evaluated the pulmonary static compliance and the driving pressure as reported previously [

13]. The ICU mortality was also evaluated. For quantitative variables, the worst values available during the ICU stay were considered.

The medical records and imaging were reviewed by expert team of Pneumologists (J.B.) and Radiologists (M.D.B.) who assessed the etiological diagnosis of ILD.

All survivors provided a written consent to the study. For deceased patients, we underwent a search for opposition for research in medical records. The research project IPIC “Interstitial Pneumonia in Intensive Care” was evaluated by the ethics committee of the French-speaking intensive care society and approved on the 27/01/2021 (under reference: CE SRLF 21-02).

Data were expressed as mean for quantitative values and percentage for qualitative values, and were compared with Fisher exact test, according to the distribution. A p-value < 0.05 was considered as significant. Statistical analyses were performed using Graph Pad Prism (San Diego, United States).

3. Results

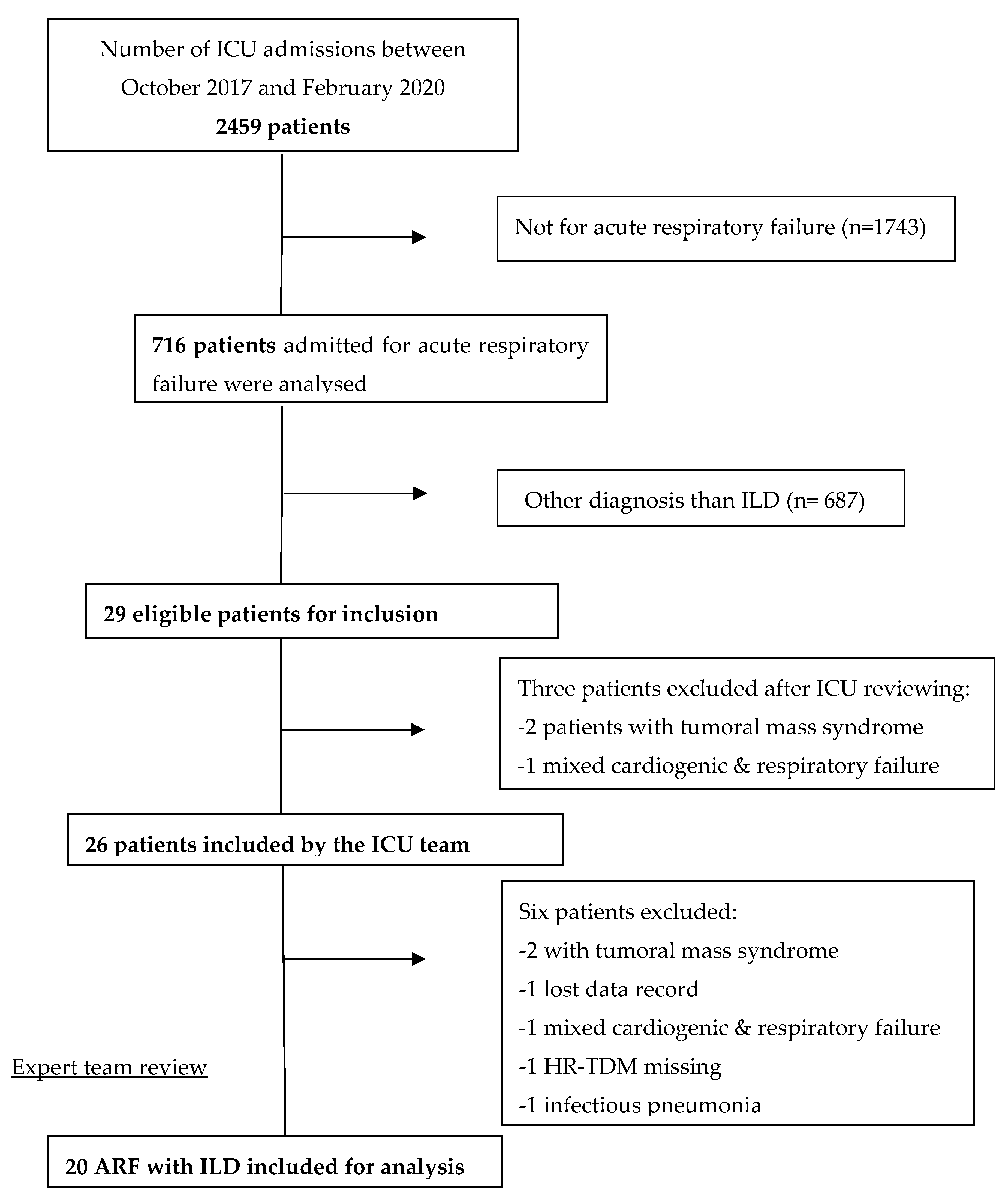

Of the 2459 patients admitted to our ICU during the inclusion period, 716 were diagnosed as ARF. The main diagnosis was ILD for 29 patients. After local reviewing by the intensivist team, three patients met exclusion criteria: one for mixed cardiogenic and respiratory failure and two for tumoral mass syndrome. The cohort of patient was then reviewed by the expert teams and six other patients were excluded: one patient because of loss of data, one because no HRCT was performed, one for left heart failure, one for infectious pneumonia and two others for tumoral mass syndrome. After the second expert reviewing 20 confirmed patients with ARF complicated newly diagnosed ILD were included in our cohort (

Figure 1).

The patient’s medical history and characteristics are listed in the

Table 1.

Three patients had previously known connective tissue disease (CTD), but none of them had known ILD due to their CTD. Fifteen (75%) were men with a mean age of 70 [62–72].

During the screening time schedule, intensivists have successfully diagnosed 77% (20/26) patient with previously unknown ILD (

Table 2).

Altogether among patients admitted to the ICU during the screening time schedule, 1% of them were confirmed ILD, which represented 3% of all patients admitted with ARF (

Table 2).

Table 3 reports the related diseases that cause ILD, as well as the related HRCT patterns that were identified to make the diagnosis.

Main diagnoses were idiopathic ILD (n = 7, 35%), auto-immune disease related ILD (n = 7, 35%), exposure-related ILD (n = 3, 15%) and carcinomatous lymphangitis (n = 3, 15%). Exposure-related causes included radiation, the drug docetaxel, and hypersensitivity pneumonitis.

Severity and ventilatory parameters are reported in

Table 4.

Median SOFA score was 4 [3–7]. Most patients (95%) met Berlin’s criteria for ARDS, with a mean PaO2:FiO2 at 173 [148–198] mmHg. The ICU mortality rate was 65% of the patients, reaching 75% among those requiring invasive mechanical ventilation. The ICU mortality rate in our cohort was significantly higher than that of other ICU patients (65% vs 25.7%, p<0.003) (

Table 5).

Four (57%) patients died in the auto-immune disease subgroup.

A steroid first-line treatment was administered to 6 (30%) patients. The steroid infusion consisted of 1 mg/kg of body weight of methylprednisolone for at least three days straight. Retrospectively, the etiology of their ILD was diagnosed as cryptogenic organizing pneumonia (COP), hypersensitivity pneumonitis, docetaxel-induced ILD, systemic lupus erythematosus, anti-synthetase syndrome, or systemic sclerosis. The 6 patients receiving steroids survived to the ICU stay.

4. Discussion

During the period of study, 1% of our ICU patients were admitted for ILD. On the specific subgroup of patients with ARF, the proportion of ILD was 3%. Our cohort showed a large panel of ILD diagnosis. HRCT was the key element of the diagnosis for the expert team, and identification of the imaging patterns was necessary for the definitive ILD diagnosis.

The most frequent diagnoses were idiopathic ILD (35%), auto-immune associated ILD (35%) and carcinomatous lymphangitis (15%). The mortality was quite high (65%) with notable variations among two subgroups: mortality was higher in the patients requiring invasive mechanical ventilation (75%) and lower in the patients with auto-immune features (57%). Similar results have been shown previously [

4,

15]. This emphasizes the importance of the causal diagnosis in case of ILD in order to give the appropriate treatment.

Our study showed that the diagnosis of ILD among ARF patients is infrequent in the ICU but should be suggested in few patients. Intensivists should be aware of this disease. They can request the help of an expert team in the lack of diagnosis during ARF after excluding a cardiac failure or an infection. Such data justify to perform a thoracic HRCT for patients with ARF when treatments directed against infection or heart failure did not improve the patients and to set a multidisciplinary discussion .

To improve diagnosis, bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) should be discussed with patients who can afford it. In our study, these data were unavailable for the patients. However, BAL not only allows one to explore infection, but it can also help clinicians make diagnoses based on cellular patterns and cytology. In a recent study, Chang et al. demonstrated that BAL was useful for diagnosing ILD in the ICU and allowed treatment modification in 60% of patients [

16]. However, the benefit of BAL should be balanced by the risks of hypoxia or bronchospasm [

17].

In a single-center study conducted at a tertiary ICU center, Gerard et al. performed surgical lung biopsies on 7% of patients with non-resolving ARDS. This strategy identified 37% of corticosteroid-sensitive pathologies, most of which were idiopathic ILD [

18]. Invasive testing, such as a lung biopsy, should be reserved for ILD with an unconfirmed diagnosis, and only after multidisciplinary discussion involving radiologists, pulmonologists, and intensivists. However, less invasive methods, such as transbronchial cryobiopsy, can be discussed with the expert team, as they yield diagnoses with a similar degree of confidence (60% vs. 73%) for certain patterns compared to video-assisted thoracoscopic surgery (VATS) [

19]. A surgical lung biopsy should be discussed as a last resort in a multidisciplinary discussion, since it is associated with a higher mortality risk in these patients, with a 30-day post-procedure mortality rate of around 5%. [

5]

Early identification of ILD in patients with ARF in the ICU could lead to rapid treatment of the underlying disease. In our cohort, steroid administration was the only specific therapy used. Recommendations maintain steroids as the first-line treatment for acute exacerbation of idiopathic lung disease [

19,

20], and they are often mentioned with good results in specific diagnosis such as organizing pneumonia [

21]. However, recent data suggest favorable results with antifibrotic and immunomodulatory therapies for various diagnosis [

19]. Indeed, patients with ILD associated with anti-MDA-5 antibodies (aMDA-5) have a high 6-month mortality rate exceeding 50%, but they may have a better prognosis. A combination of steroids, calcineurin inhibitors, and cyclophosphamide (CYC) has been shown to significantly improve outcomes for these patients [

22]. Another team has also shown improved survival in a recent series of patients using a combination of immunosuppressive drugs, including JAK inhibitors [

23]. However, in patients with exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, CYC use has recently been shown to be associated with higher mortality, suggesting that immunosuppressive therapy should be avoided for such patients [

24]. Rituximab treatment in conjunction with mycophenolate mofetil (MMF) has also been shown to be more effective than MMF alone in patients with non-specific interstitial pneumonia (NSIP) [

25]. Finally, nintedanib, an antifibrotic agent known for its efficacy in slowly progressive fibrotic ILD, may be a new therapeutic option for acute exacerbations of fibrosing ILD, as Urushiyama et al. recently demonstrated [

26].

Taken together, these data underscore the importance of discussing ILD diagnoses with an expert team after excluding infection and heart failure to provide optimal treatment for patients.

More knowledge about ILD in the ICU could also be necessary to justify therapeutic limitations. For example, an ILD associated with aMDA-5 patient or patients with acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis requiring invasive mechanical ventilation have respectively 84% and 87% mortality in the ICU [

27,

28]. Our results are consistent with these findings. Of note, our only patient with aMDA-5 died. On the other hand, organizing pneumonia is known to have a good prognosis when treated with steroids [

29]. In our cohort, the only patient affected with organizing pneumonia survived after steroid treatment.

Thus, intensivists need to know more about ILD and discuss or integrate an expert team in order to define the best care for patients.

Our study specifically focused on patients with previously unknown ILD disease. Dhanani et al. recently published a comprehensive review of the management of ILD patients in the ICU, including those with acute exacerbation of previously diagnosed ILD [

30]. This review summarizes the most recent knowledge and could be considered a reference, as there is no standard of care for ILD in the ICU. Since our study was not prospective, the intensivists did not follow any specific therapeutic bundle to manage ILD patients. However, we can see that the ventilatory management of ILD in the ICU was applied according to the latest data, which implies a wide range of oxygen and ventilation strategies, such as high-flow nasal oxygen (HFNO), mechanical ventilation with low positive end-expiratory pressure (PEP), and, if necessary, veno-venous extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) (see

Table 4).

We must acknowledge several limitations. First, our study was monocentric and retrospective, which could have introduced biases. Furthermore, the study was conducted at a single center, which limits the number of patients for this rare disease. Therefore, the generalization of the results should be approached with caution. Nevertheless, few studies have evaluated acute and previously unknown ILD in the ICU, and our study highlights the importance of knowing about such diseases for intensivists.

5. Conclusions

Over the period of study, 20 ICU patients were successfully diagnosed with previously unknown ILD. The ICU mortality was higher than the average ICU mortality during the inclusion period. HRCT is critical to diagnose ILD among patients with ARF. A multidisciplinary approach including an expert radiology team and pneumologists is essential to confirm the diagnosis of ILD and possibly start a specific treatment, but intensivists should know this disease as first line provider.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, D.E.. and F.M.; methodology, D.E., F.M., M.L.; software, J.B.; validation, all authors.; formal analysis, J.B..; investigation, D.E., M.D.B.; resources, D.E.; data curation, D.E.; writing—original draft preparation, D.E., F.M.; writing—review and editing, D.E., J.B., and M.L..; visualization, D.E..; supervision, M.L, J.B., F.M.; project administration, F.M.; funding acquisition, N/A. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki, and approved by Ethics Committee of the French intensive care society (Société de réanimation de langue française) on the 27/01/2021, under the reference “CE SRLF 21-02”

Informed Consent Statement

All survivors provided a written consent to the study. For deceased patients, we underwent a search for opposition for research in medical records.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the D.E. on reasonable request.

Declarations

D.E. has made an oral presentation of primary results of the study during the 2021 French intensive care society Congress which is referenced as follow: “FC-150 Characteristics and outcomes of diffuse interstitial pneumonias discovered in ICU: a retrospective monocentric study (The IPIC study)”.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| aMDA-5 |

anti-MDA-5 antibodies |

| ATS |

American Thoracic Society |

| ARDS |

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrom |

| ARF |

Acute respiratory Failure |

| ATS |

American Thoracic Society |

| BAL |

bronchoalveolar lavage |

| CYC |

cyclophosphamide |

| CTD |

Connective tissue disease |

| COP |

cryptogenic organizing pneumonia |

| DMD |

Multidisciplinary discussion |

| ECMO |

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation |

| ERS |

European Thoracic Society |

| HFNO |

High-Flow nasal oxygen |

| HRCT |

high-resolution computed tomography |

| ICU |

Intensive Care Unit |

| ILD |

Interstitial Lung Disease |

| MMF |

mycophenolate mofetil |

| NSIP |

Non-specific interstitial pneumonia |

| PaO2:FiO2 |

ratio of the oxygen pressure to the fraction of inspired oxygen ratio |

| SOFA |

Sepsis-related Organ Failure Assessment |

| PEP |

Positive End-expiratory Pressure |

References

- American Thoracic Society, European Respiratory Society. American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society International Multidisciplinary Consensus Classification of the Idiopathic Interstitial Pneumonias. This joint statement of the American Thoracic Society (ATS), and the European Respiratory Society (ERS) was adopted by the ATS board of directors, June 2001 and by the ERS Executive Committee, June 2001. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2002, 165, 277–304. [Google Scholar]

- Travis WD, Costabel U, Hansell DM, et al. An official American Thoracic Society/European Respiratory Society statement: Update of the international multidisciplinary classification of the idiopathic interstitial pneumonias. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2013, 188, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Coultas DB, Zumwalt RE, Black WC, Sobonya RE. The epidemiology of interstitial lung diseases. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 1994, 150, 967–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huapaya JA, Wilfong EM, Harden CT, Brower RG, Danoff SK. Risk factors for mortality and mortality rates in interstitial lung disease patients in the intensive care unit. Eur Respir Rev 2018, 27, 180061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wijsenbeek M, Suzuki A, Maher TM. Interstitial lung diseases. Lancet 2022, 400, 769–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ARDS Definition Task Force, Ranieri VM, Rubenfeld GD, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome: the Berlin Definition. JAMA 2012, 307, 2526–2533. [Google Scholar]

- Bellani G, Laffey JG, Pham T, et al. Epidemiology, Patterns of Care, and Mortality for Patients With Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome in Intensive Care Units in 50 Countries. JAMA 2016, 315, 788–800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meyer NJ, Gattinoni L, Calfee CS. Acute respiratory distress syndrome. Lancet 2021, 398, 622–637. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gibelin A, Parrot A, Maitre B, et al. Acute respiratory distress syndrome mimickers lacking common risk factors of the Berlin definition. Intensive Care Med 2016, 42, 164–172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papazian L, Calfee CS, Chiumello D, et al. Diagnostic workup for ARDS patients. Intensive Care Med 2016, 42, 674–685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mikolasch TA, Garthwaite HS, Porter JC. Update in diagnosis and management of interstitial lung disease. Clin Med (Lond) 2017, 17, 146–153. [Google Scholar]

- Vincent JL, de Mendonça A, Cantraine F, et al. Use of the SOFA score to assess the incidence of organ dysfunction/failure in intensive care units: results of a multicenter, prospective study. Working group on “sepsis-related problems” of the European Society of Intensive Care Medicine. Crit Care Med 1998, 26, 1793–1800. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Amato MBP, Meade MO, Slutsky AS, et al. Driving pressure and survival in the acute respiratory distress syndrome. N Engl J Med 2015, 372, 747–755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gertler, R. Respiratory Mechanics. Anesthesiol Clin 2021, 39, 415–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gannon WD, Lederer DJ, Biscotti M, et al. Outcomes and Mortality Prediction Model of Critically Ill Adults With Acute Respiratory Failure and Interstitial Lung Disease. Chest 2018, 153, 1387–1395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang S-L, Tsai H-C, Lin F-C, Chao H-S, Chou C-W, Chang S-C. Clinical usefulness of bronchoalveolar lavage in patients with interstitial lung diseases: a pilot study. J Thorac Dis 2020, 12, 3125–3134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schnabel RM, van der Velden K, Osinski A, Rohde G, Roekaerts PMHJ, Bergmans DCJJ. Clinical course and complications following diagnostic bronchoalveolar lavage in critically ill mechanically ventilated patients. BMC Pulm Med 2015, 15, 107. [Google Scholar]

- Gerard L, Bidoul T, Castanares-Zapatero D, et al. Open Lung Biopsy in Nonresolving Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Commonly Identifies Corticosteroid-Sensitive Pathologies, Associated With Better Outcome. Crit Care Med 2018, 46, 907–914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maher, TM. Interstitial Lung Disease: A Review. JAMA 2024, 331, 1655–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raghu G, Remy-Jardin M, Richeldi L, et al. Idiopathic Pulmonary Fibrosis (an Update) and Progressive Pulmonary Fibrosis in Adults: An Official ATS/ERS/JRS/ALAT Clinical Practice Guideline. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2022, 205, e18–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petitpierre N, Beigelman C, Letovanec I, Lazor R. [Cryptogenic organizing pneumonia]. Rev Mal Respir 2016, 33, 703–717. [Google Scholar]

- Matsushita T, Mizumaki K, Kano M, et al. Antimelanoma differentiation-associated protein 5 antibody level is a novel tool for monitoring disease activity in rapidly progressive interstitial lung disease with dermatomyositis. Br J Dermatol 2017, 176, 395–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen Z, Wang X, Ye S. Tofacitinib in Amyopathic Dermatomyositis-Associated Interstitial Lung Disease. N Engl J Med 2019, 381, 291–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naccache J-M, Jouneau S, Didier M, et al. Cyclophosphamide added to glucocorticoids in acute exacerbation of idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (EXAFIP): a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, phase 3 trial. Lancet Respir Med 2022, 10, 26–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mankikian J, Caille A, Reynaud-Gaubert M, et al. Rituximab and mycophenolate mofetil combination in patients with interstitial lung disease (EVER-ILD): a double-blind, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Eur Respir J 2023, 61, 2202071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urushiyama H, Jo T, Hasegawa W, et al. Effect of nintedanib on acute exacerbations of fibrosing interstitial lung diseases: a national database study in Japan. ERJ Open Res 2022, 8, 00209–02022. [Google Scholar]

- Mallick, S. Outcome of patients with idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF) ventilated in intensive care unit. Respir Med 2008, 102, 1355–1359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuillard C, Pineton de Chambrun M, de Prost N, et al. Clinical features and outcome of patients with acute respiratory failure revealing anti-synthetase or anti-MDA-5 dermato-pulmonary syndrome: a French multicenter retrospective study. Ann Intensive Care 2018, 8, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzikowska E, Fijolek J. Update on cryptogenic organizing pneumonia. Front Med (Lausanne) 2023, 10, 1146782. [Google Scholar]

- Dhanani Z, Gupta R. The Management of Interstitial Lung Disease in the ICU: A Comprehensive Review. J Clin Med 2024, 13, 6657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).