Submitted:

04 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

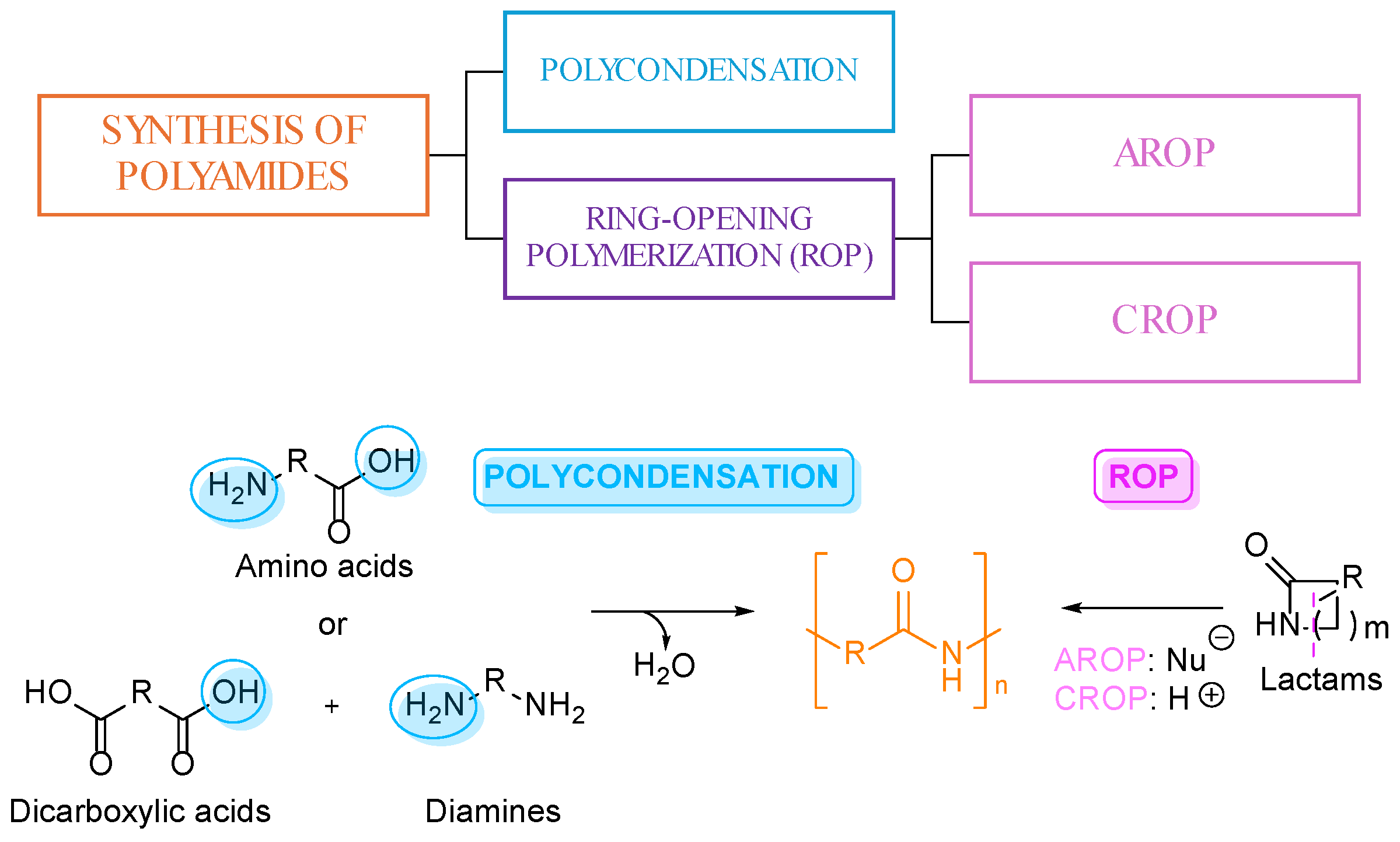

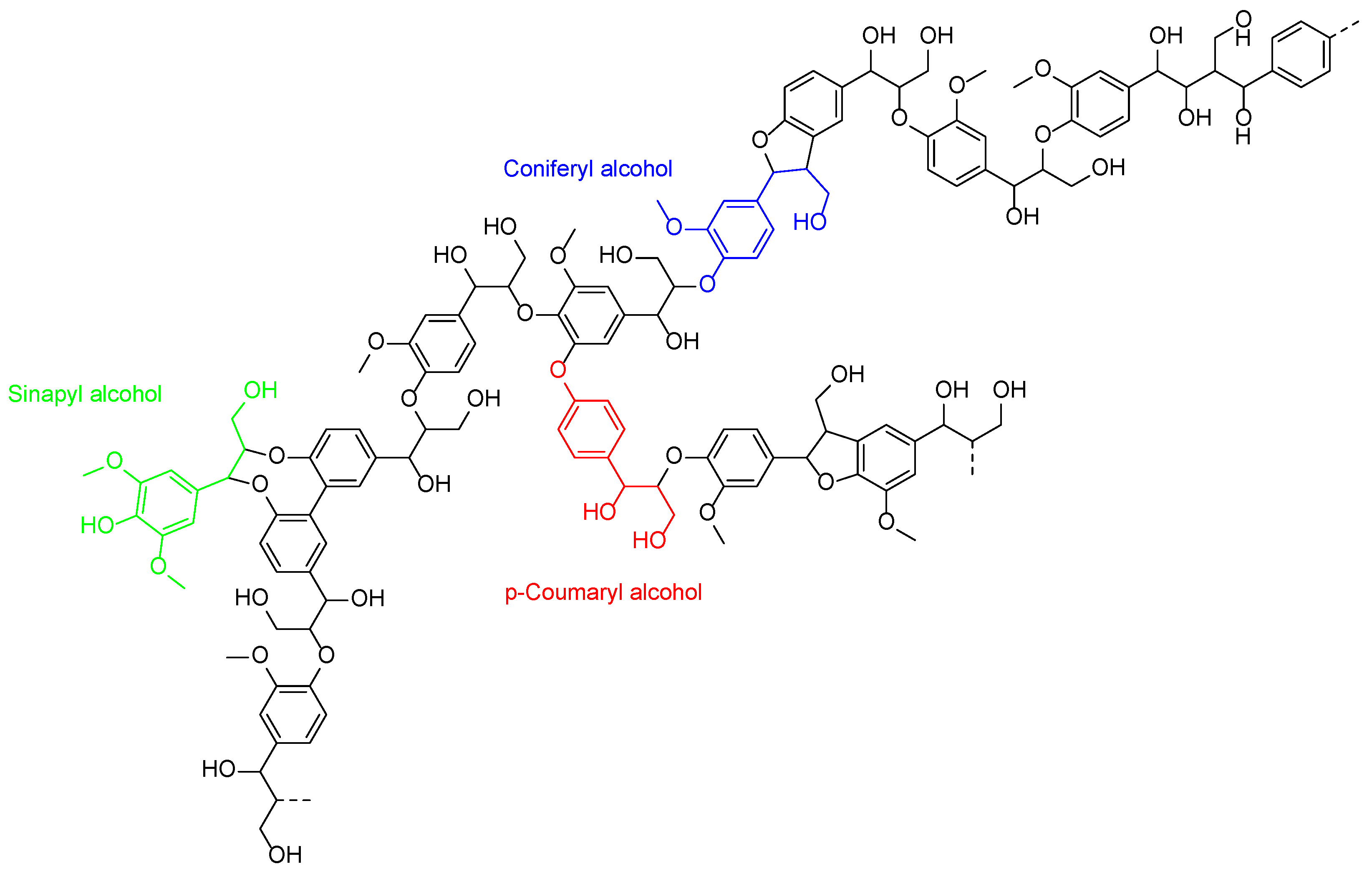

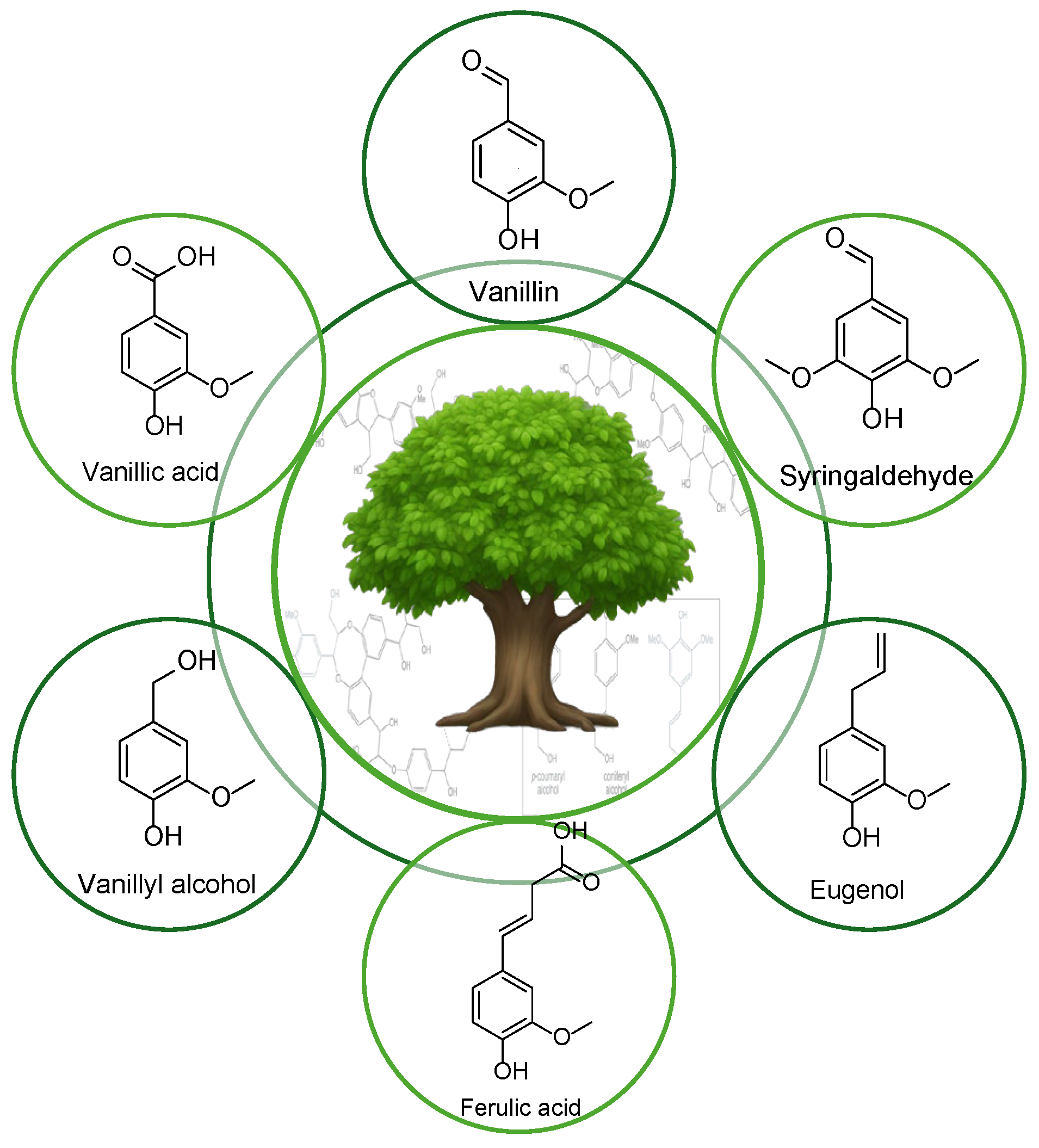

1. Introduction

2. Synthesis of PAs from Lignin-Derived Monomers

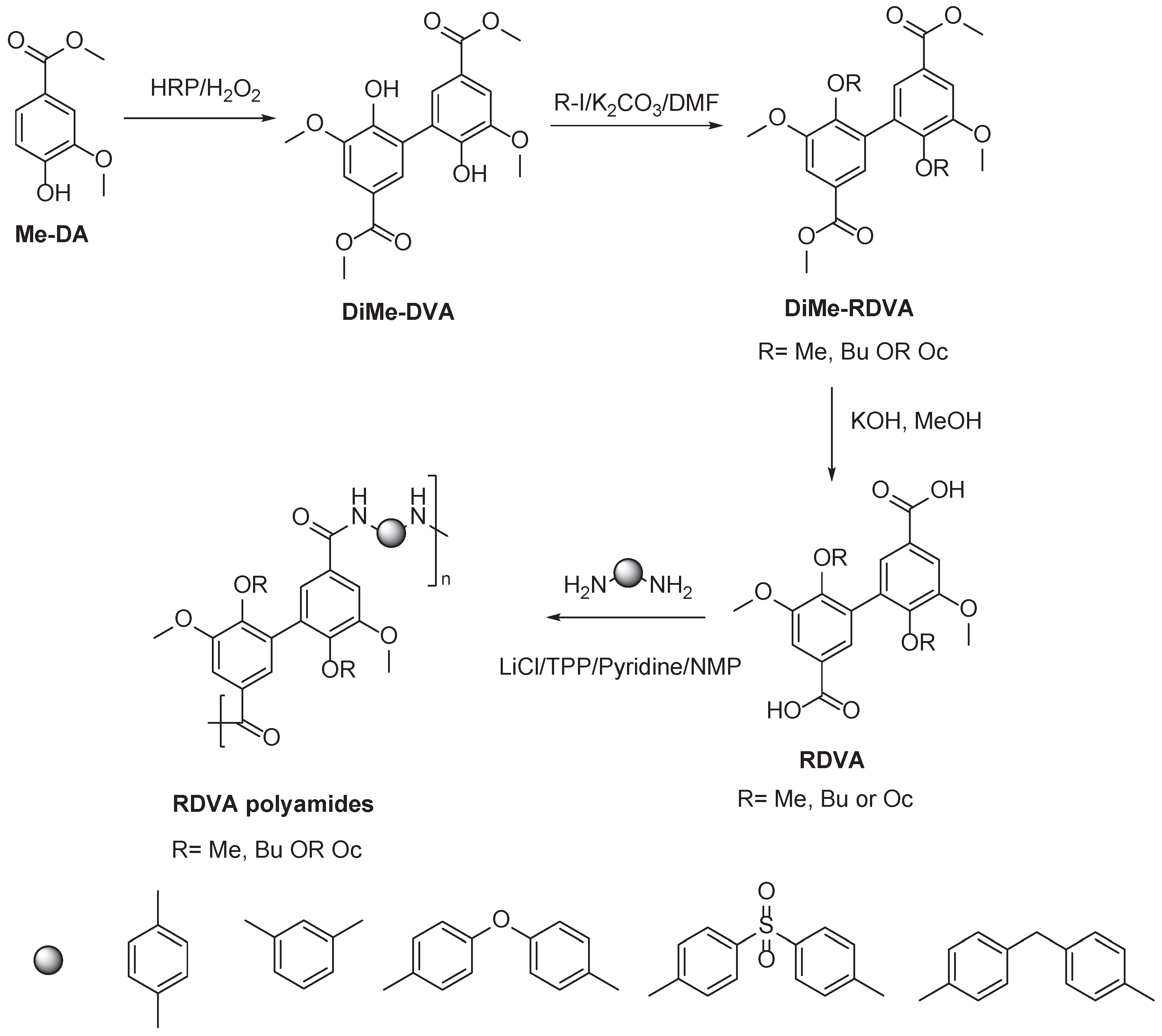

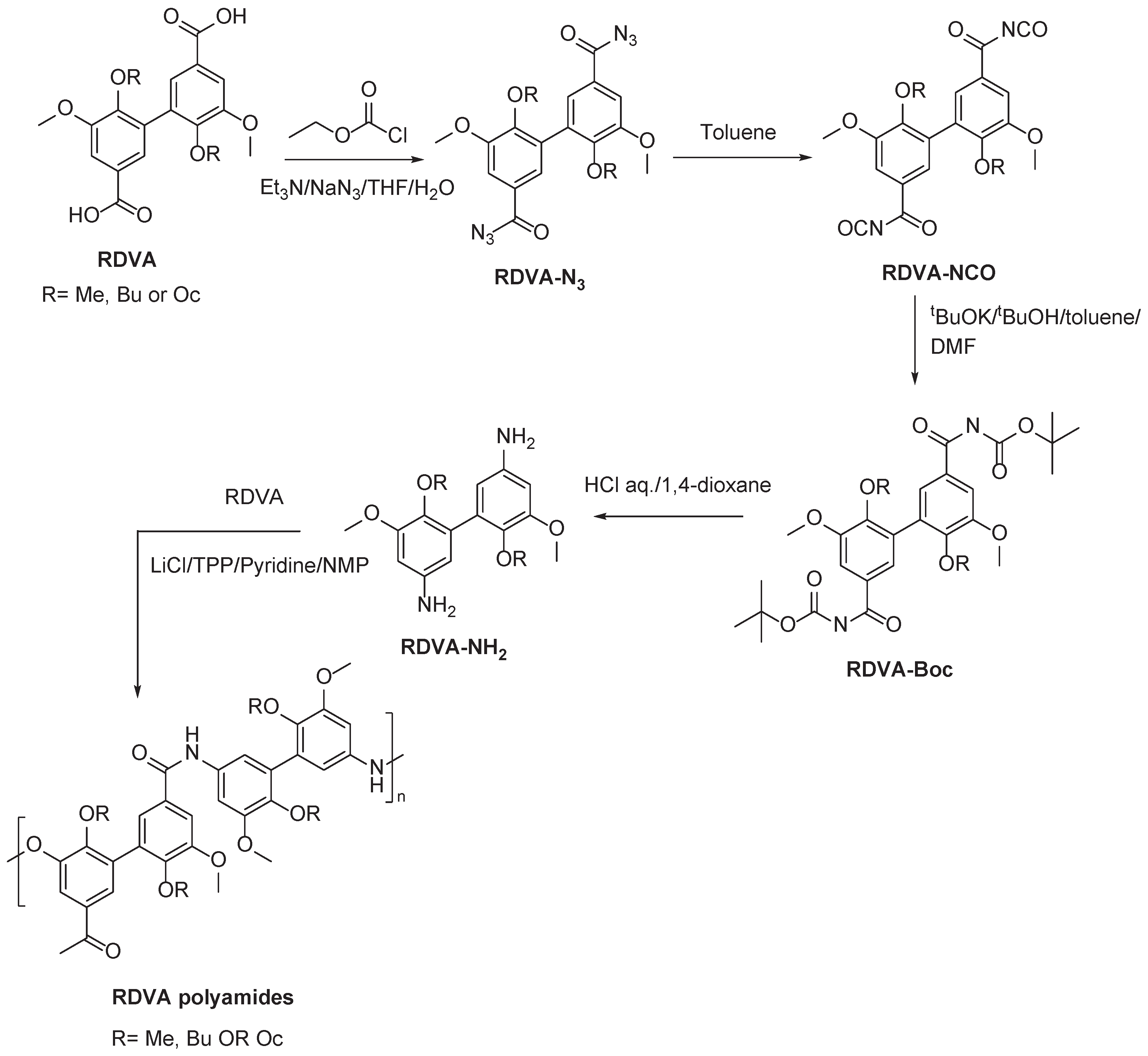

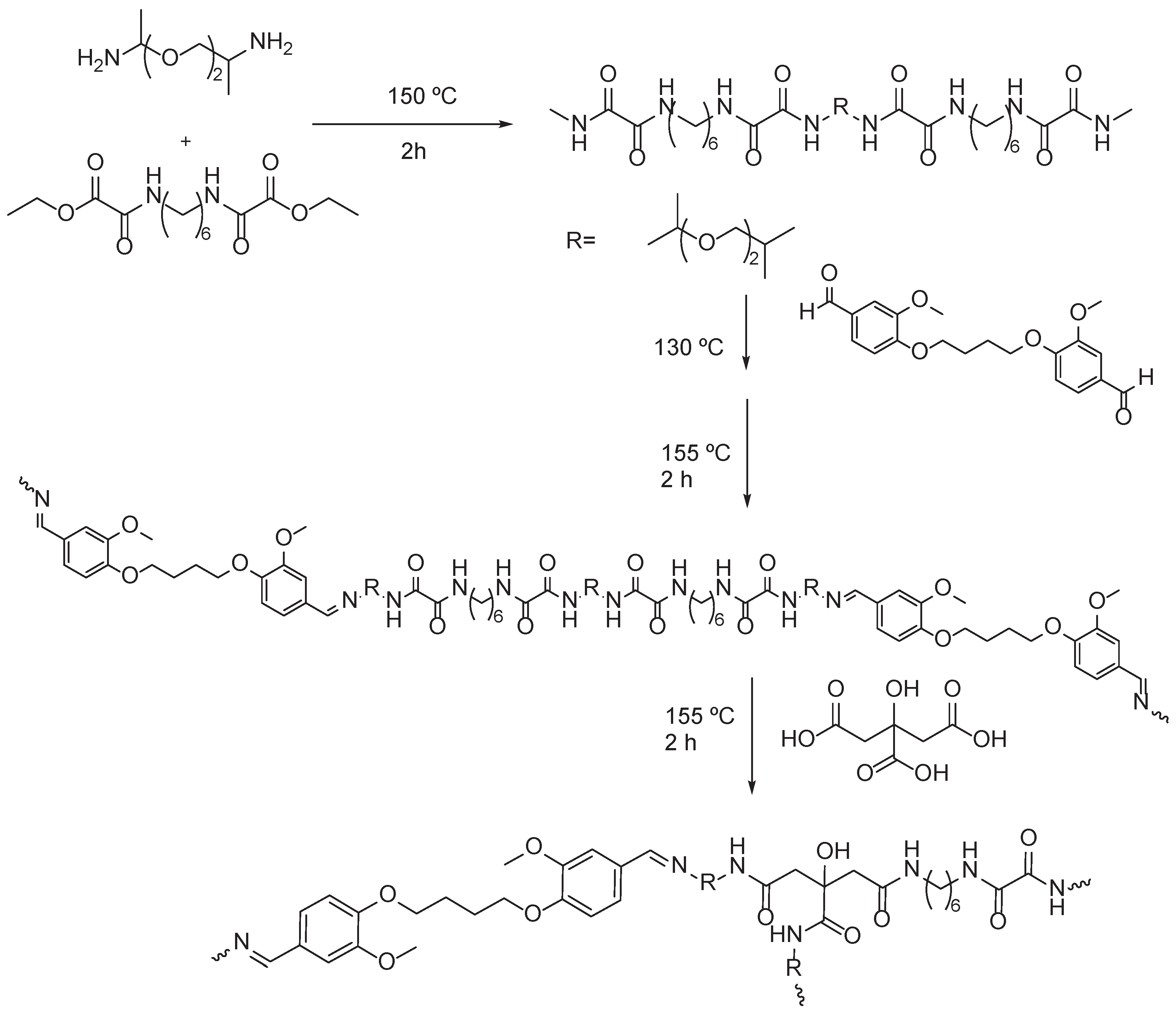

2.1. Vanillin based PAs

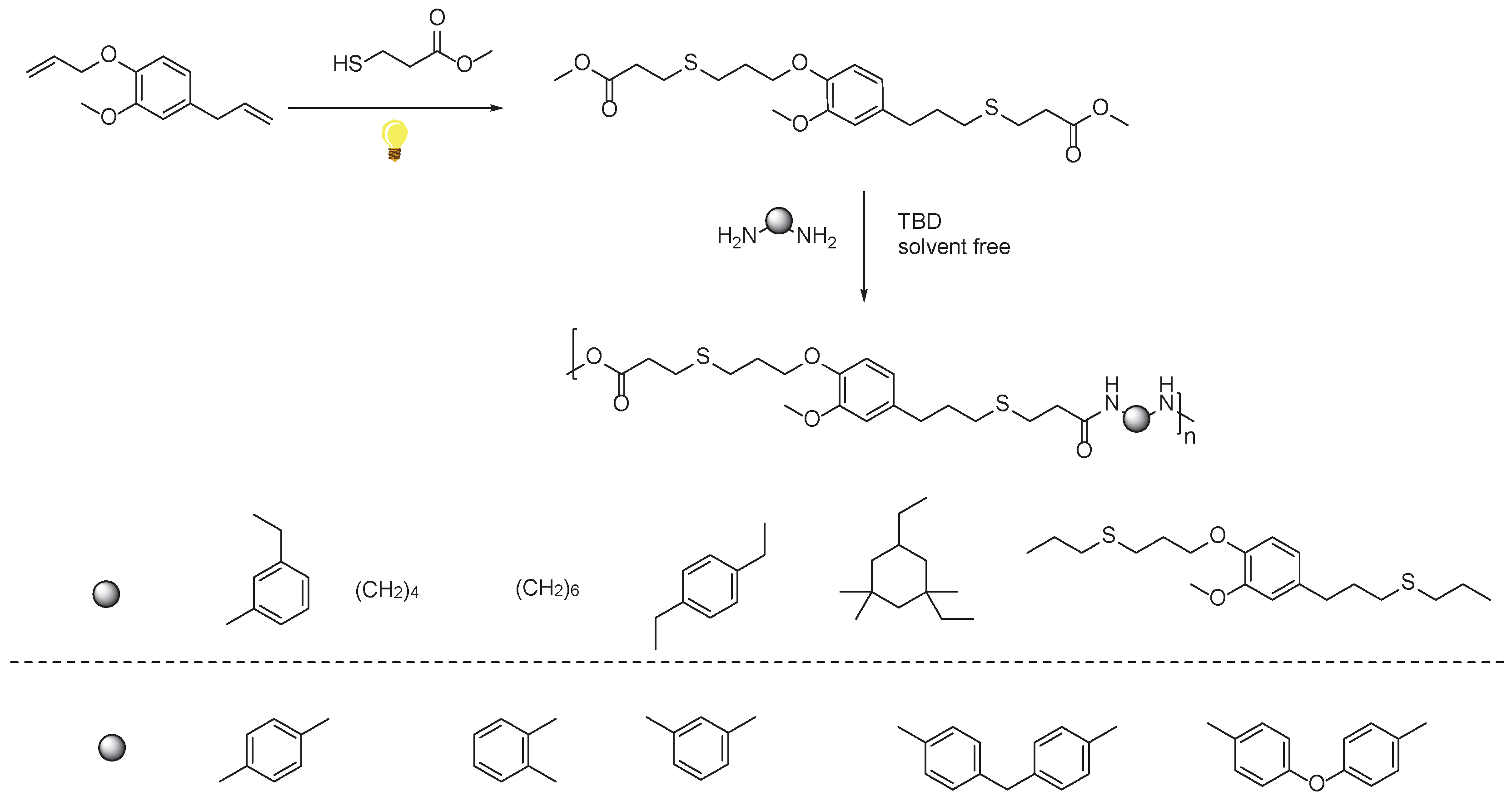

2.2. Eugenol Based PAs

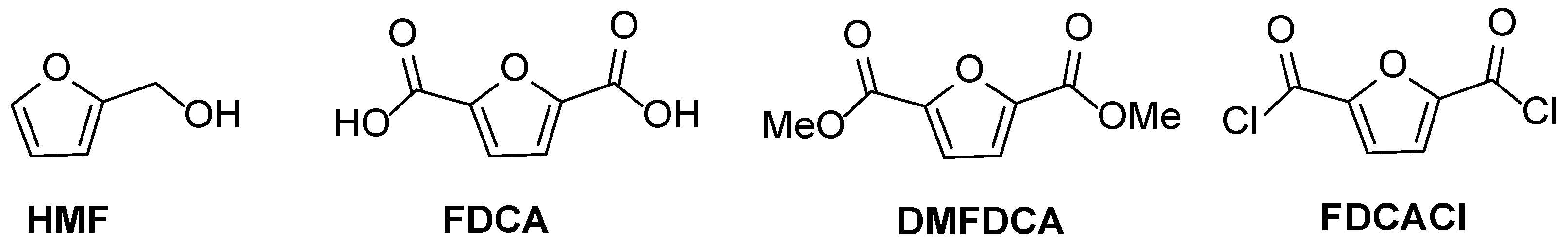

3. Furan Based PAs

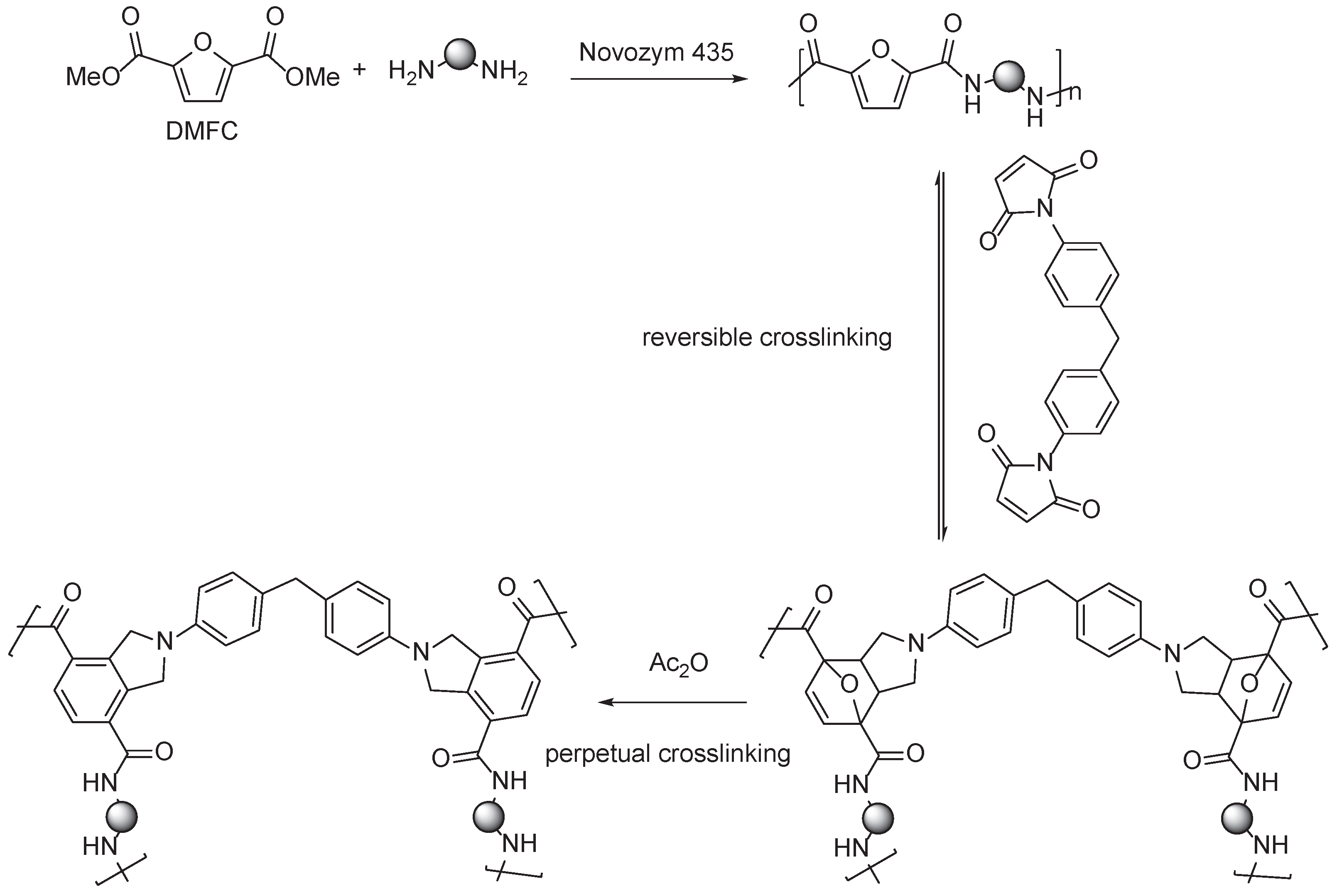

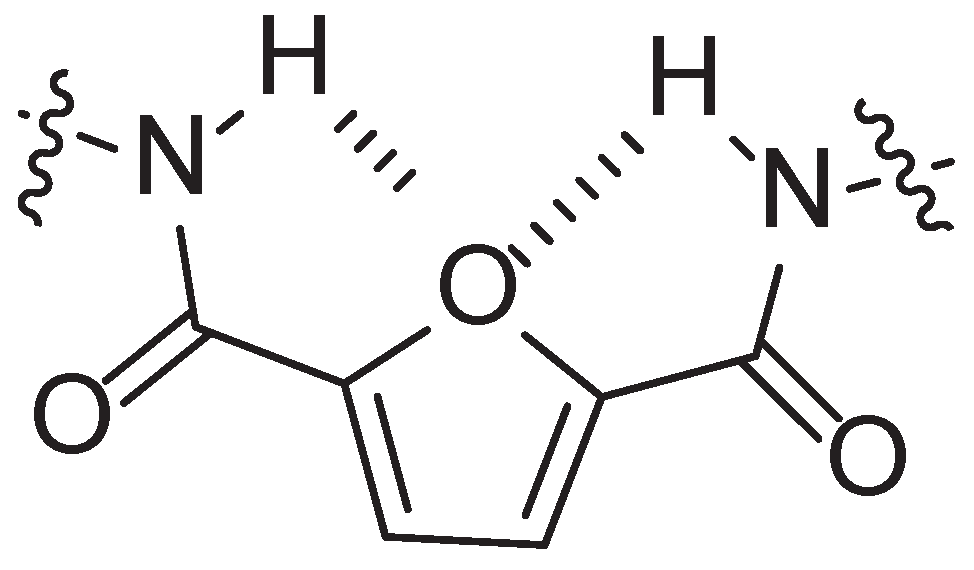

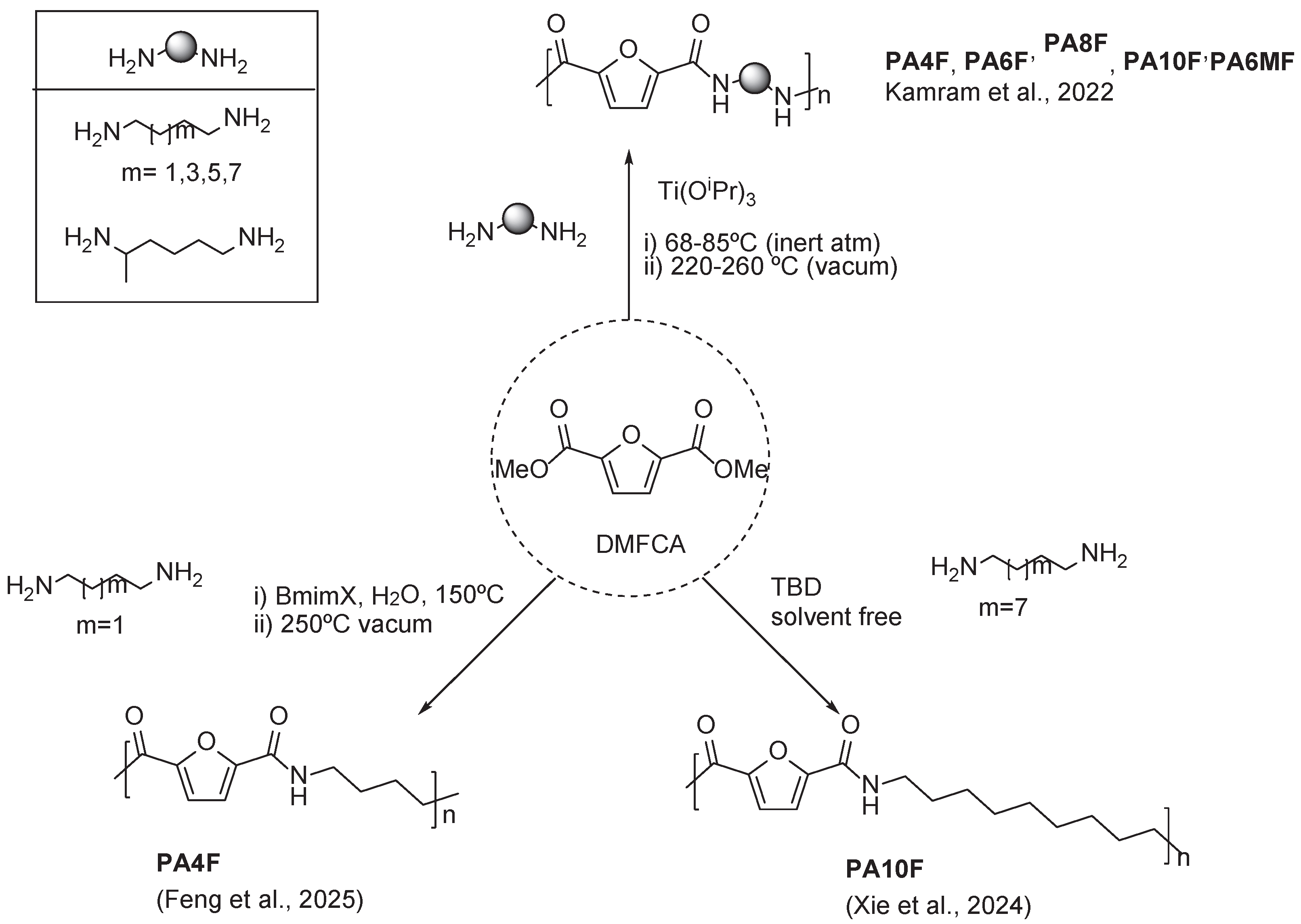

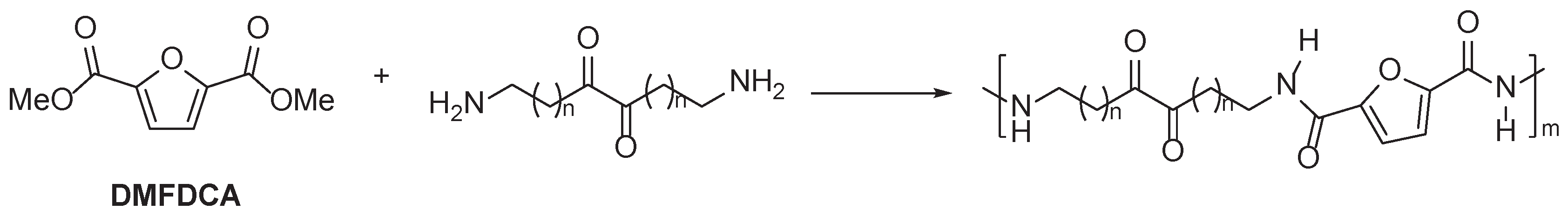

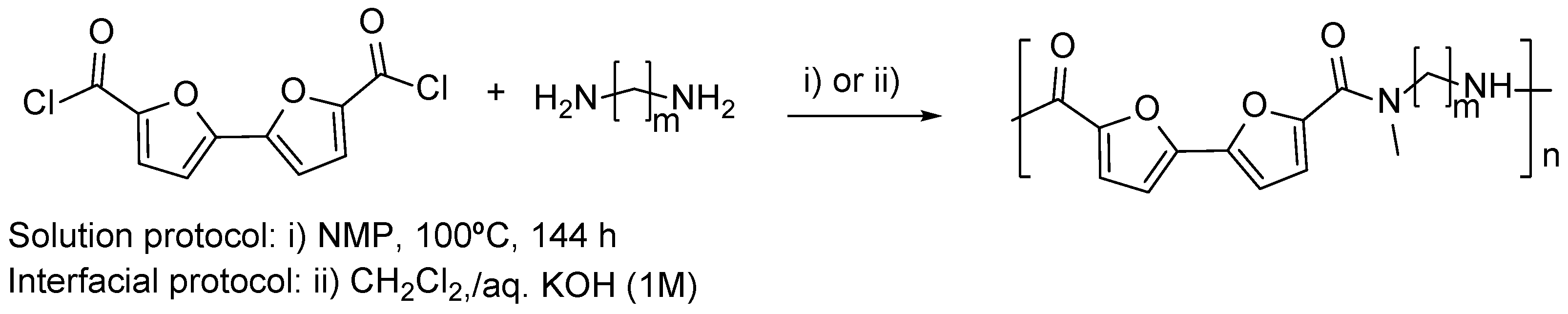

3.1. Furan Containing Aliphatic PAs

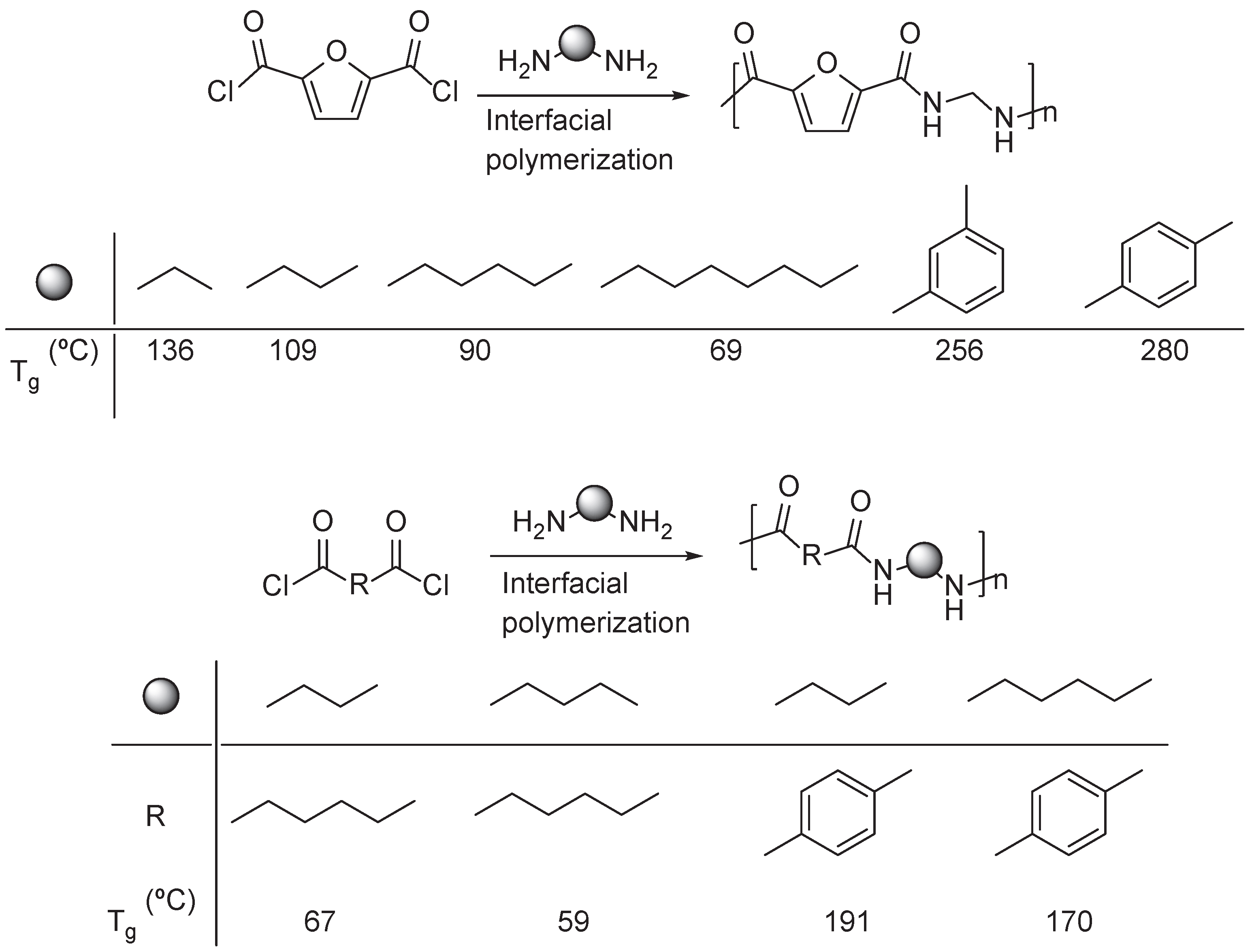

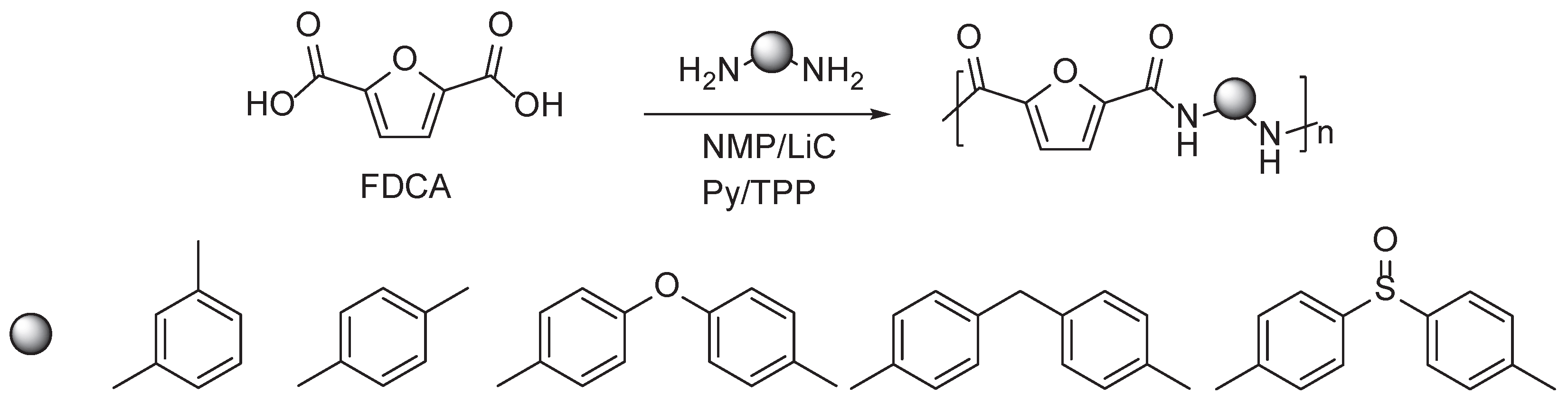

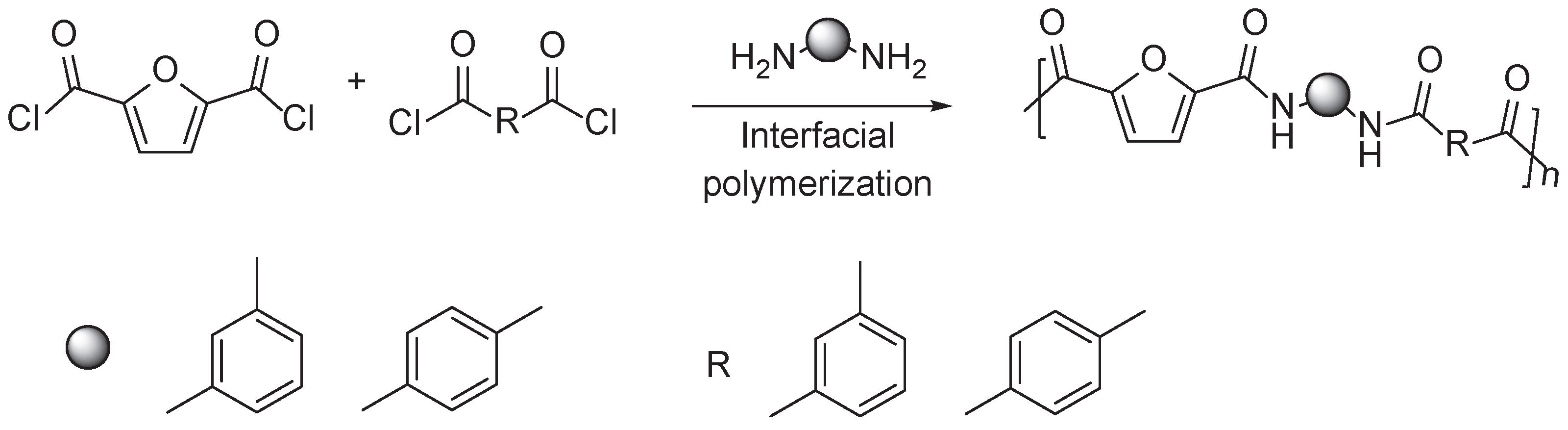

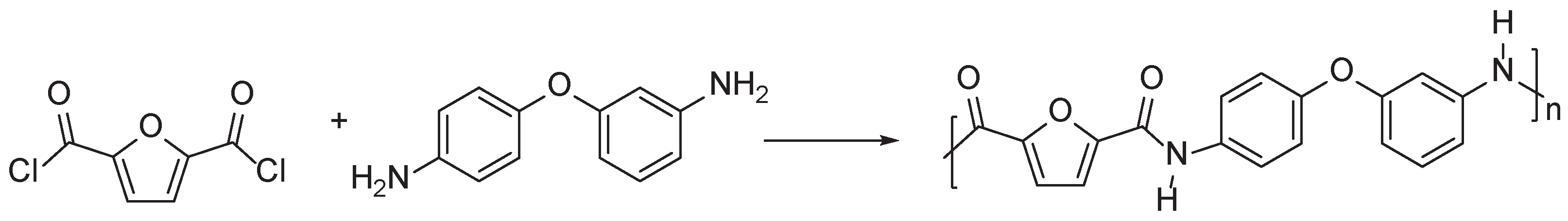

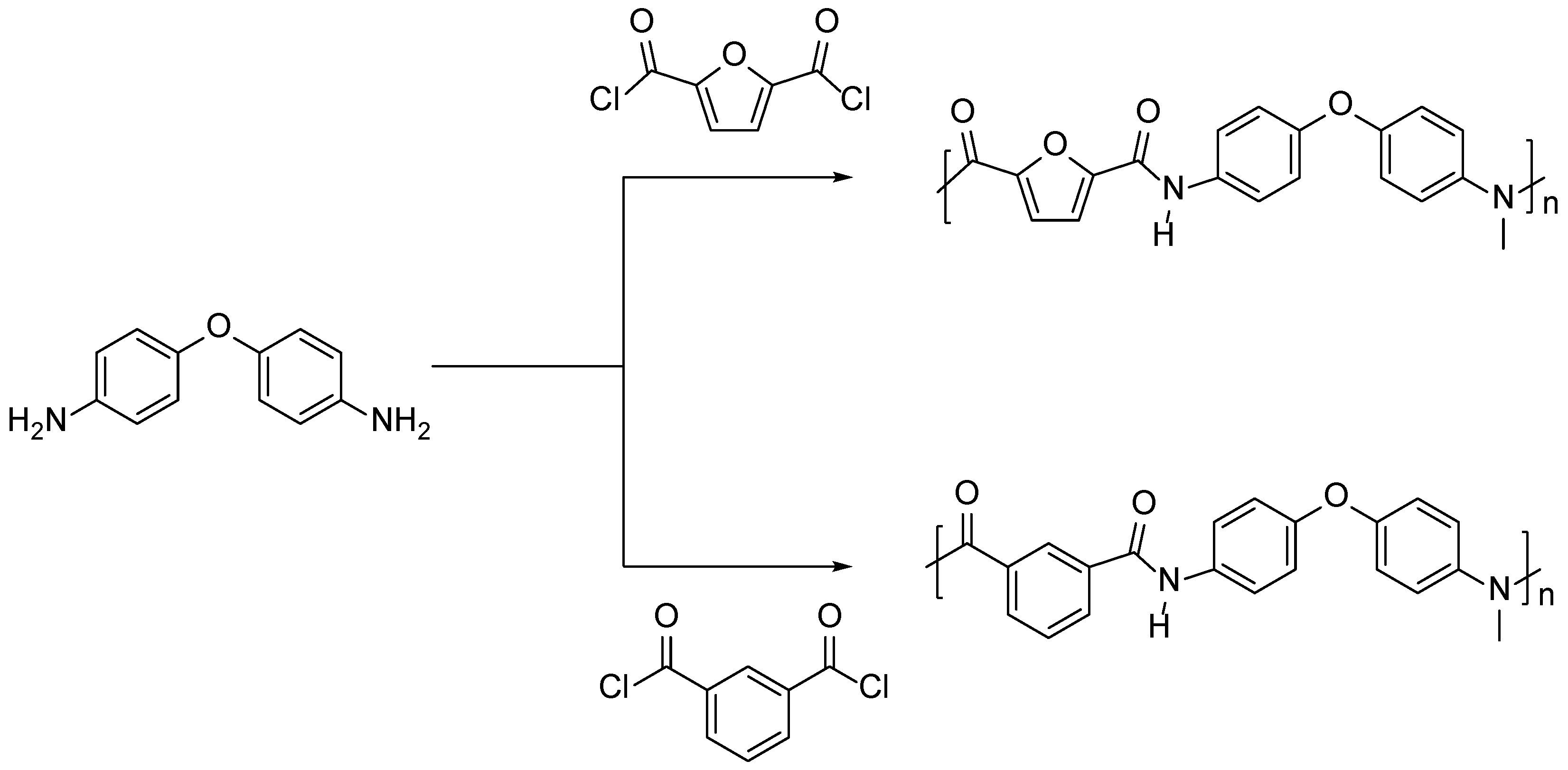

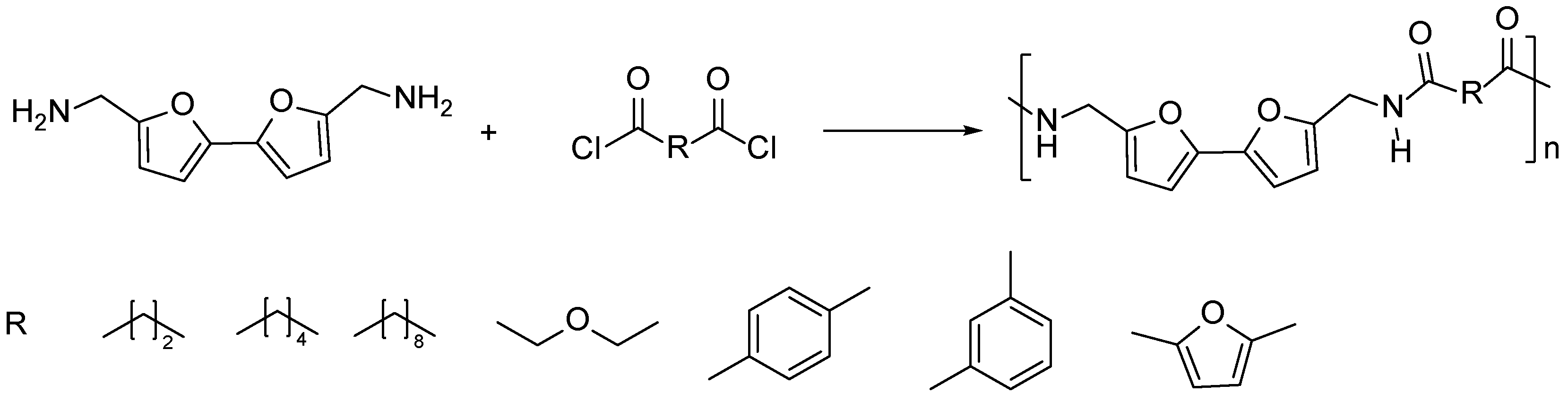

3.2. Furan Containing Aromatic PAs

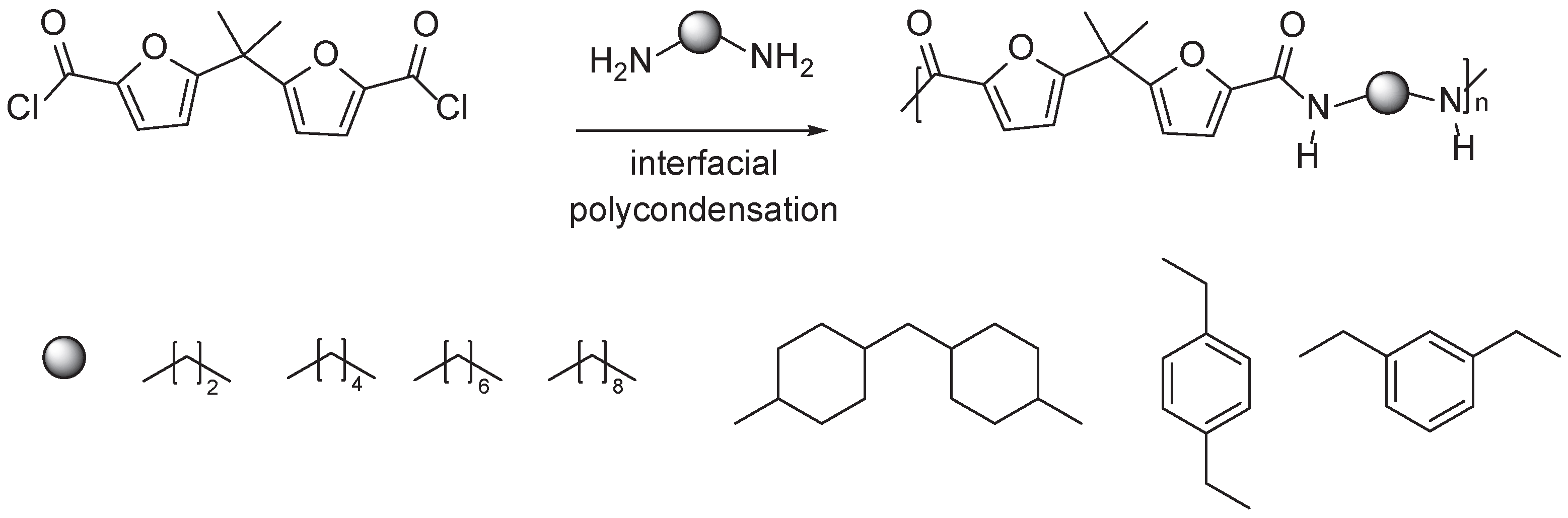

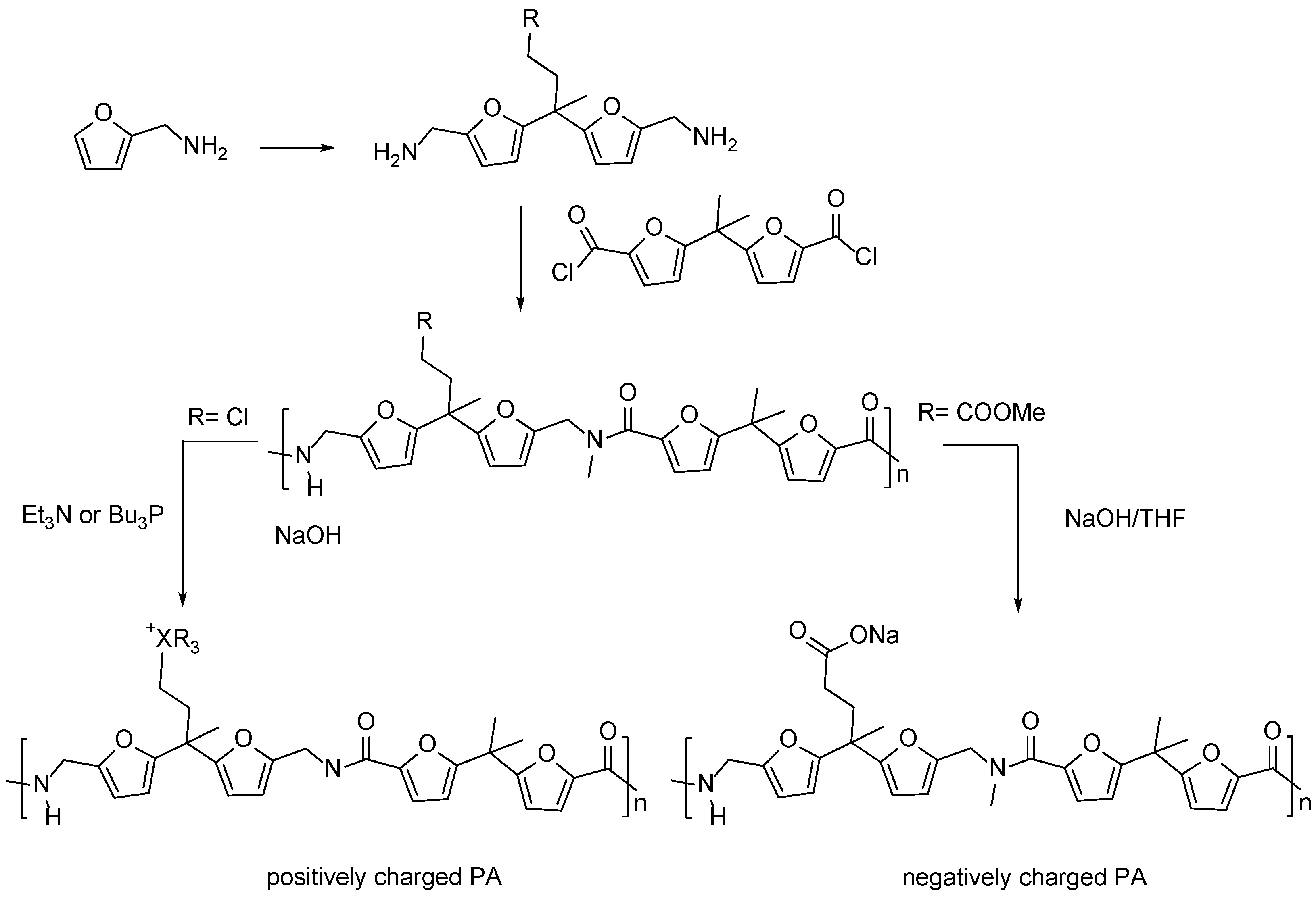

3.3. Multifuran Monomers

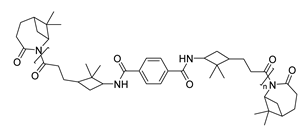

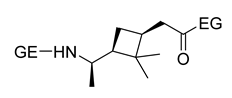

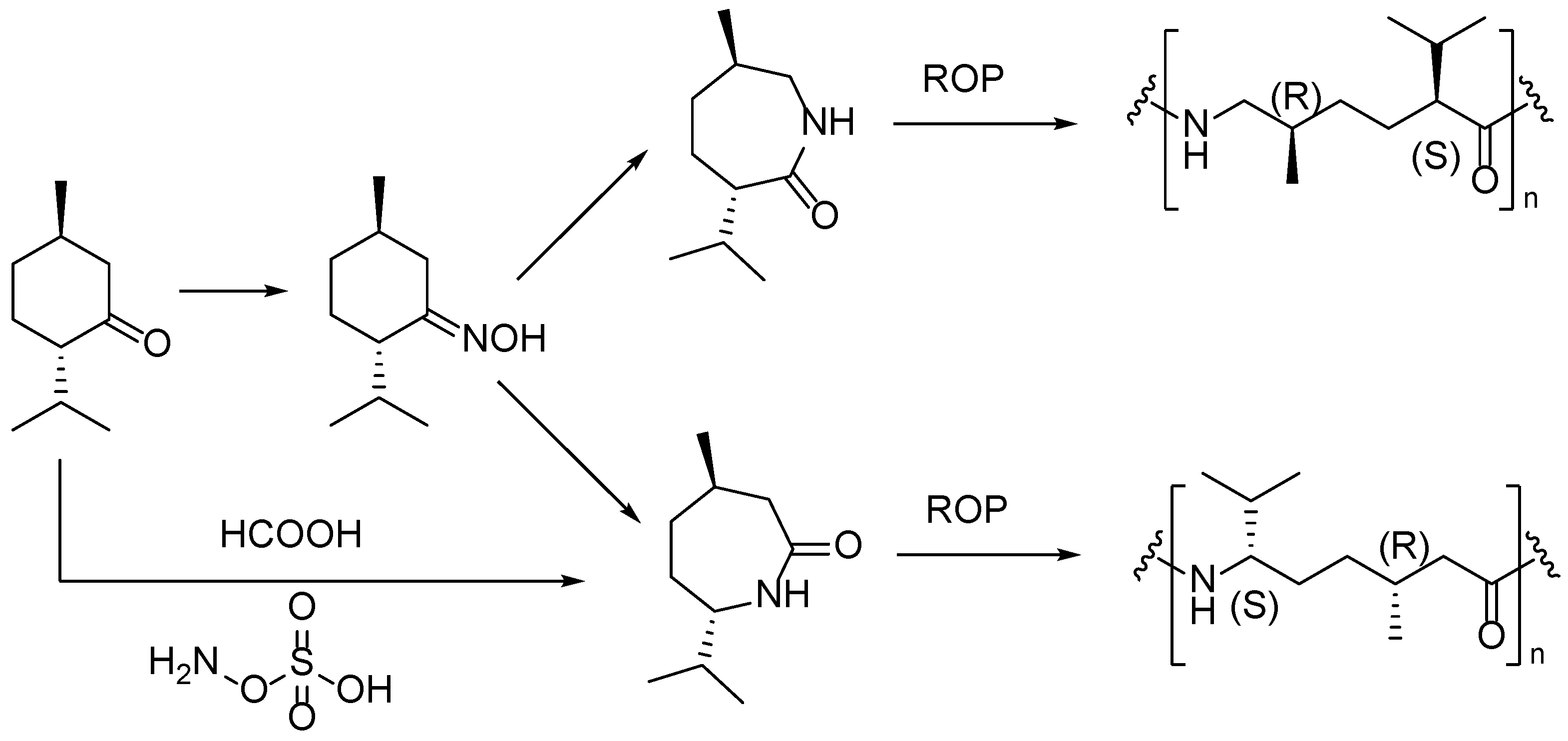

4. Terpene Derived PAs

| Entry | Substrate | ROP | Properties of PAs | Structure | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

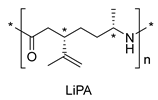

| 1 | Limonene oxide | Anionic |

|

|

[14] |

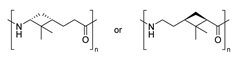

| 2 | β-pinene | Cationic |

|

|

[89] |

| 3 | β-pinene | Anionic |

|

|

[87] |

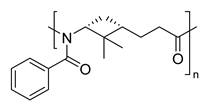

| 4 | α-pinene | Anionic |

|

|

[86] |

|

|||||

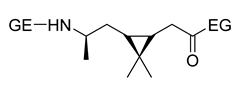

| 5 | β-pinene | Anionic |

|

|

[88] |

| 6 | (+)-3-carene | Anionic |

|

|

[86] |

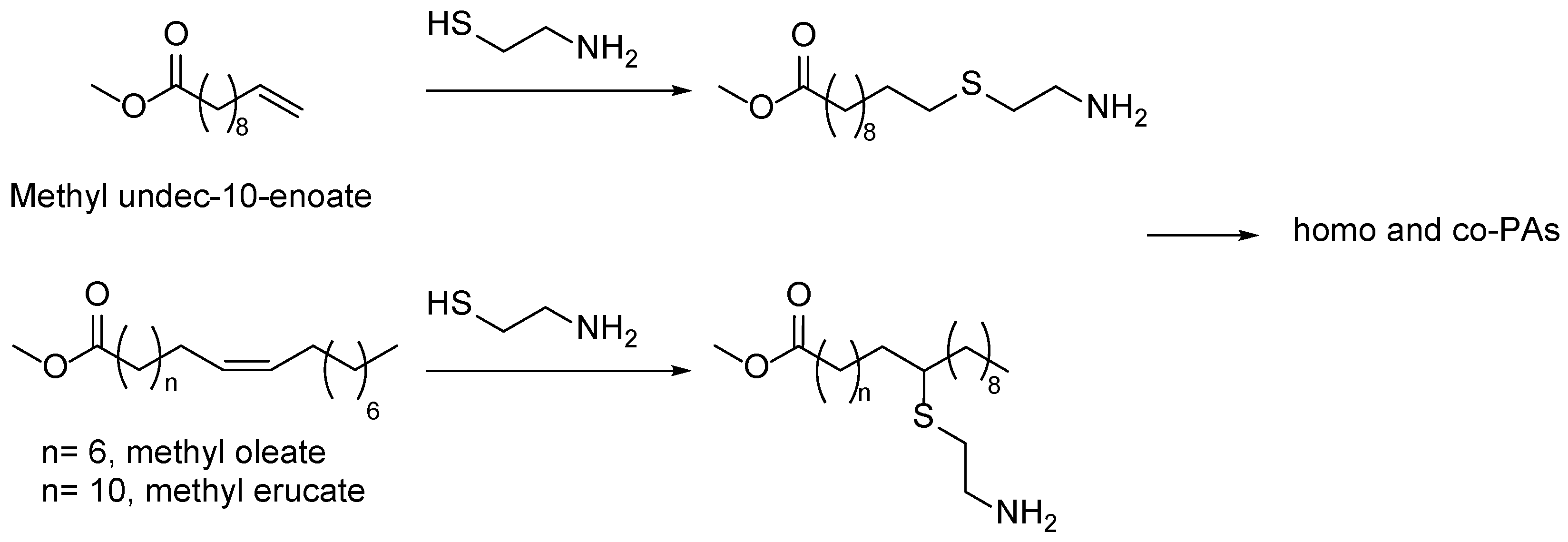

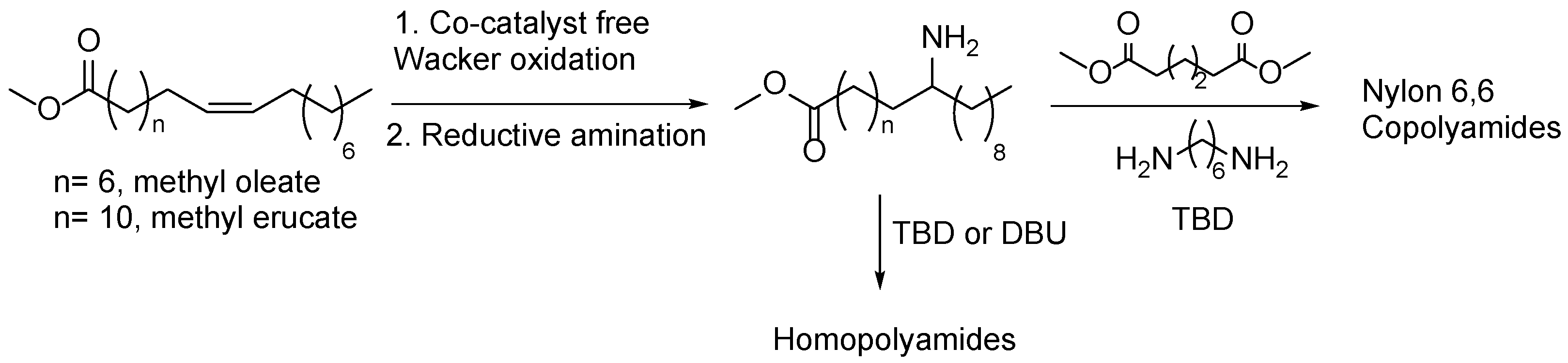

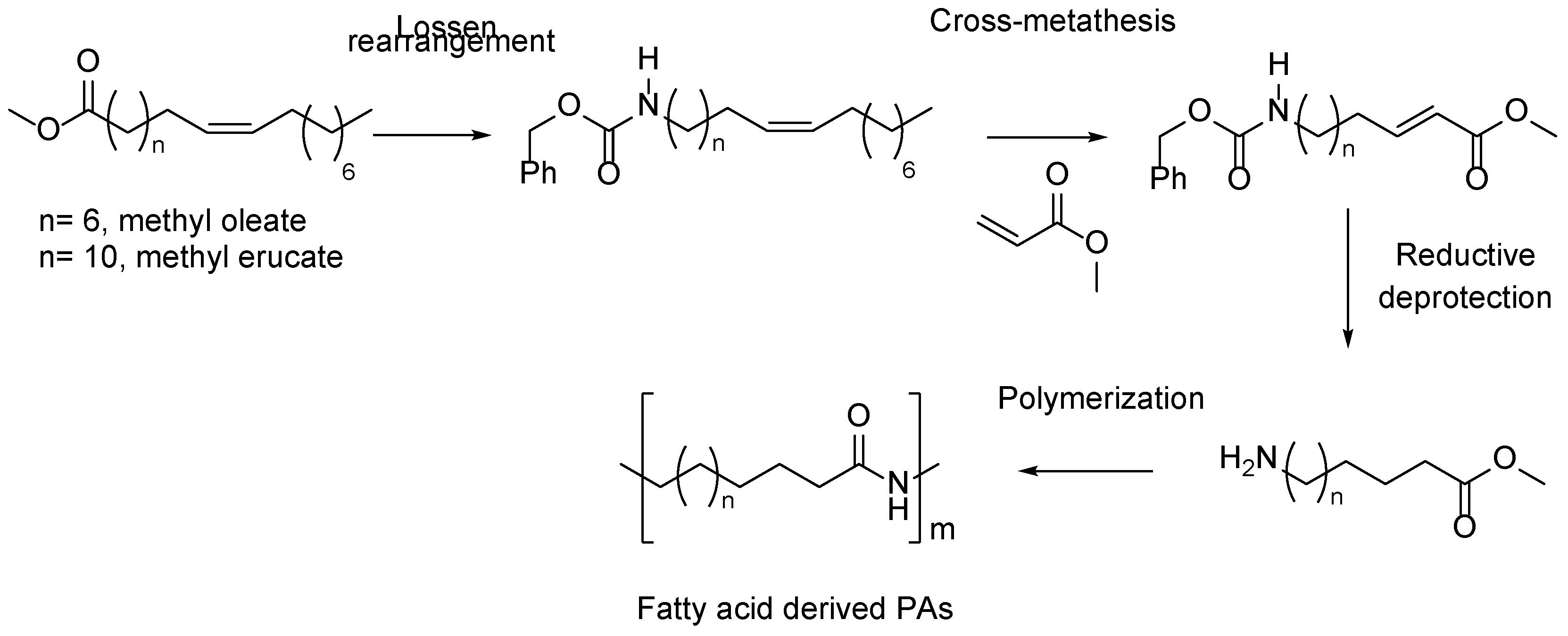

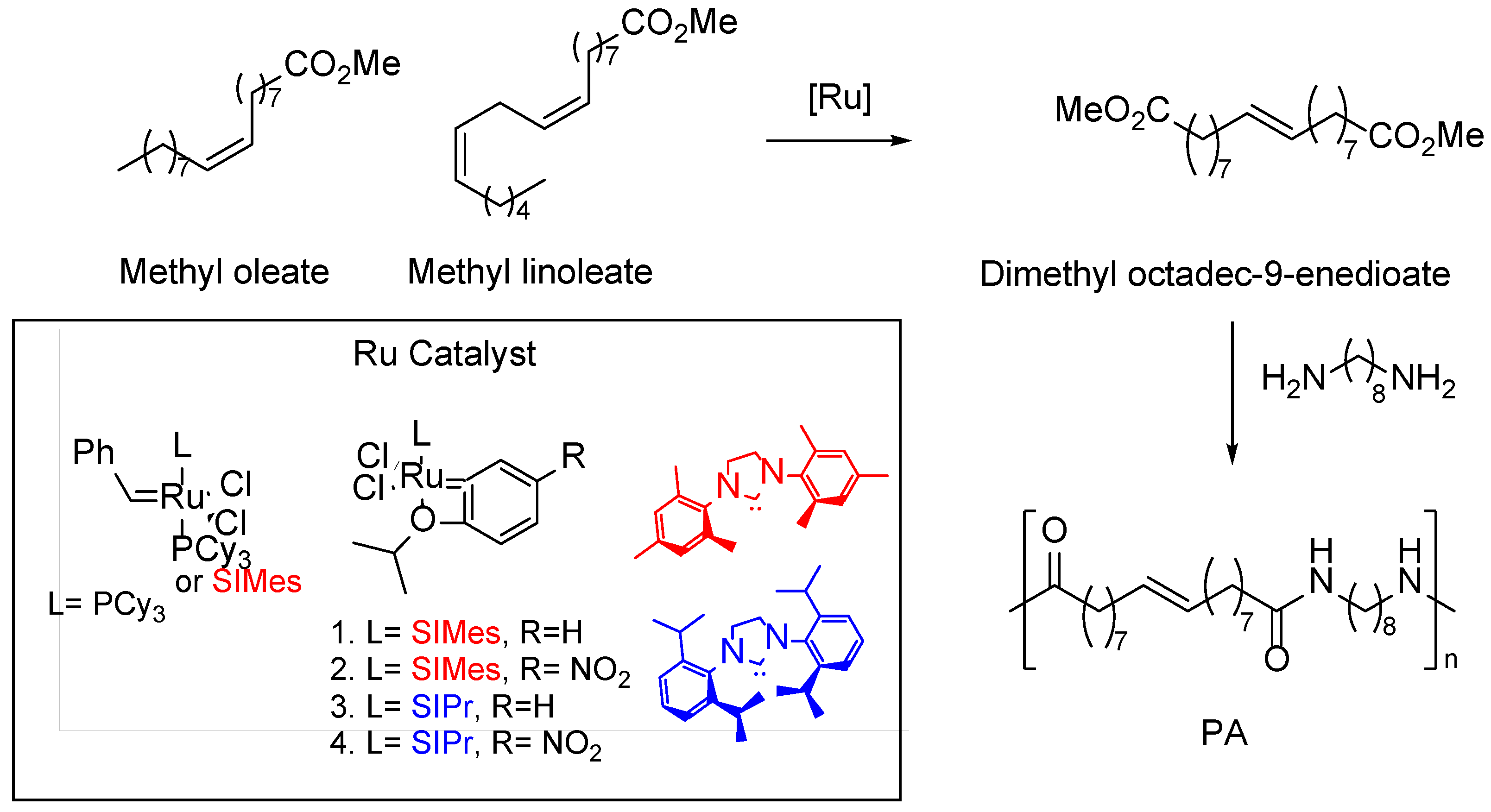

5. Fatty Acid Derived PAs

5. Conclusions and Future Trends

Author Contributions

Funding

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| µm | micrometro |

| AROP | Anionic ring-opening polymerization |

| BHMF | 2,5-bis(hydroxymethyl)furan |

| Bmim | 1-butyl-3-methylimidazolium |

| Bz | Benzoylated lactam |

| C6, C8 | Carbon 6, Carbon 8 |

| CALB | Candida Antartica Lipase B |

| CC | Cyclocarbonated |

| CH2Cl2 | Dichloromethane |

| CROP | Cationic Ring-Opening Polymerization |

| DFA | Dimer fatty acid methyl esters |

| DBU | 1,8-diazabicyclo [5.4.0]undecen-7-ene |

| DETA | Diethylenetriamine |

| DMA | Dynamic Mechanical Analysis |

| DMF | N,N’-Dimethylformamide |

| DMFDCA | Dimethoxyferulic dicarboxylate |

| DMP | Dimethyl pimelimidato |

| DSC | Differential Scanning Calorimetry |

| DVA | Divanillinic acid |

| FAME | Fatty acid methyl ester |

| FDCA | 2,5-Furandicarboxylic acid |

| FDCACl | 2,5-Furandicarboxylic acil chloride |

| FTIR | Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy |

| GPa | GigaPascals |

| GPC | Gel Permeation Chromatography |

| GPC/SEC | Gel-permeation chromatography |

| h | hours |

| HMDA | Hexamethylenediamine |

| HMF | 5-hydroxymethylfurfural (HMF) |

| IR | Infrared Spectroscopy |

| kDa | kiloDalton |

| MALDI | Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization |

| mbar | milibar |

| MDA | 1,8-diamino-p-menthane |

| MPa | MegaPascals |

| MPC | m-phthaloyl chloride |

| MPD | m-phenylenediamine |

| MULCH | Monounsaturated long-chain |

| Mn | Molecular weight |

| NMR | Nuclear Magnetic Resonance |

| PA | Polyamides |

| PA6,6 | Poly(hexamethylene adipamide) |

| PA8F | Polyamide 8 Furan or Poly(octamethylene furandicarboxamide) |

| PA8T | Poly(octamethylene terephthalamide) |

| PFA | polyfluoroalkyl |

| PPD | p-phenylenediamine |

| PXDA | p-xylylenediamine |

| Ref. | Reference |

| ROP | Ring-opening polymerization |

| SEM | Scanning Electron Microscopy |

| SSP | Solid-state polymerization |

| TBD | 1,5,7-Triazabiciclo [4.4.0]dec-5-ene |

| TCL | Terephtaloylchloride |

| Td | Degradation temperature |

| Tg | Glass transition temperature |

| TGA | Thermogravimetric analysis |

| THF | Tetrahydrofuran |

| TIPT | Titanium isopropoxide |

| Tm | Melting temperature |

| TPA | Terephtalic derived polyamides |

| US | United States |

| UV | Ultraviolet |

| WAXS | Wide-Angle X-ray Scattering |

References

- Winnacker, M.; Rieger, B. Bio-Based Polyamide 56: Recent Advances in Basic and Applied Research. Macromol Rapid Commun 2016, 37, 1391–1413. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shakiba, M.; Rezvani, E.; Khosravi, F.; Jouybar, S.; Bigham, A.; Zare, M.; Abdouss, M.; Moaref, R.; Ramakrishna, S. Nylon — A Material Introduction and Overview for Biomedical Applications. Polymers advanced technologies 2021, 32, 3368–3383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Loos, K. Enzymatic Synthesis of Biobased Polyesters and Polyamides. Polymers (Basel) 2016, 8, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negi, Y.S.; Razdan, U.; Saran, V. Soluble Aromatic Polyamides and Copolyamides. Journal of Macromolecular Science - Reviews in Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics 1999, 39 C, 391–403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jasinska, L.; Villani, M.; Wu, J.; Van Es, D.; Klop, E.; Rastogi, S.; Koning, C.E. Novel, Fully Biobased Semicrystalline Polyamides. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 3458–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, M.A.; Kaneko, T. Syntheses of Aromatic/Heterocyclic Derived Bioplastics with High Thermal/Mechanical Performance. Ind Eng Chem Res 2019, 58, 15958–15974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papaspyrides, C.D.; Porfyris, A.D.; Vouyiouka, S.; Rulkens, R.; Grolman, E.; Poel, G. Vanden Solid State Polymerization in a Micro-Reactor: The Case of Poly(Tetramethylene Terephthalamide). J Appl Polym Sci 2016, 133, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedr, M.S.F. Bio-Based Polyamide. Physical Sciences Reviews 2021, 8, 827–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arai, K.; Tsutsuba, T.; Wasano, T.; Hirose, Y.; Tachibana, Y.; Kasuya, K.I. Synthesis of Biobased Polyamides Containing a Bifuran Moiety and Comparison of Their Properties with Those of Polyamides Based on a Single Furan Ring. ACS Appl Polym Mater 2023, 5, 3866–3874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.L.; Wan, L.; Gu, X.P.; Feng, L.F. A Study on a Prepolymerization Process of Aromatic-Contained Polyamide Copolymers PA(66-Co-6T) via One-Step Polycondensation. Macromol React Eng 2015, 9, 512–521. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trossarelli, L. The History of Nylon.

- Porfyris, A.; Vouyiouka, S.; Papaspyrides, C.; Rulkens, R.; Grolman, E.; Vanden Poel, G. Investigating Alternative Routes for Semi-Aromatic Polyamide Salt Preparation: The Case of Tetramethylenediammonium Terephthalate (4T Salt). J Appl Polym Sci 2016, 133, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khedr, M.S.F. Bio-Based Polyamide. Physical Sciences Reviews 2023, 8, 827–847. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleybolte, M.M.; Zainer, L.; Liu, J.Y.; Stockmann, P.N.; Winnacker, M. (+)-Limonene-Lactam: Synthesis of a Sustainable Monomer for Ring-Opening Polymerization to Novel, Biobased Polyamides. Macromol Rapid Commun 2022, 43, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ali, A. Polyamide Syntheses. Encyclopedia of Polymeric Nanomaterials 2015, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, K.; Wang, J.; Wang, Z.; Yuan, L. Bio-Based Monomers for Amide-Containing Sustainable Polymers. Chemical Communications 2023, 59, 382–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamran, M. Towards Sustainable Engineering Plastics: Synthesis and Characterisation of Semi-Aromatic Polyamides Based on Renewable 2,5-Furandicarboxylic Acid (FDCA), 2021.

- Türünç, O.; Firdaus, M.; Klein, G.; Meier, M.A.R. Fatty Acid Derived Renewable Polyamides via Thiol-Ene Additions. Green Chemistry 2012, 14, 2577–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modjinou, T.; Versace, D.; Abbad-Andallousi, S.; Bousserrhine, N.; Dubot, P.; Langlois, V.; Renard, E. Antibacterial and Antioxidant Bio-Based Networks Derived from Eugenol Using Photo-Activated Thiol-Ene Reaction. React Funct Polym 2016, 101, 47–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schoubroeck, S. Van; Dael, M. Van; Passel, S. Van; Malina, R. A Review of Sustainability Indicators for Biobased Chemicals. Renewable and Sustainable Energy Reviews 2018, 94, 115–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshimura, T.; Shimasaki, T.; Teramoto, N.; Shibata, M. Bio-Based Polymer Networks by Thiol-Ene Photopolymerizations of Allyl-Etherified Eugenol Derivatives. Eur Polym J 2015, 67, 397–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neda, M.; Okinaga, K.; Shibata, M. High-Performance Bio-Based Thermosetting Resins Based on Bismaleimide and Allyl-Etherified Eugenol Derivatives. Mater Chem Phys 2014, 148, 319–327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.; Garrison, T.F.; Madbouly, S.A.; Kessler, M.R. Progress in Polymer Science Recent Advances in Vegetable Oil-Based Polymers and Their Composites. Prog Polym Sci 2017, 71, 91–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lochab, B.; Shukla, S.; Varma, I.K. Naturally Occurring Phenolic Sources: Monomers and Polymers. RSC Adv 2014, 4, 21712–21752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Cerrada, R.; Molina-Gutierrez, S.; Lacroix-Desmazes, P.; Caillol, S. Eugenol, a Promising Building Block for Biobased Polymers with Cutting-Edge Properties. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 3625–3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lligadas, G.; Ronda, J.C.; Galià, M.; Cádiz, V. Renewable Polymeric Materials from Vegetable Oils: A Perspective. Materials Today 2013, 16, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Loos, K. Enzymatic Synthesis of Biobased Polyesters and Polyamides. Polymers (Basel) 2016, 8, 1–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mandlekar, N.; Cayla, A.; Rault, F.; Giraud, S.; Salaün, F.; Malucelli, G.; Guan, J. Thermal Stability and Fire Retardant Properties of Polyamide 11 Microcomposites Containing Different Lignins. Ind Eng Chem Res 2017, 56, 13704–13714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Liu, L.; Renneckar, S.; Jiang, F. Chemically and Physically Crosslinked Lignin Hydrogels with Antifouling and Antimicrobial Properties. Ind Crops Prod 2021, 170, 113759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmidt, B.V.K.J.; Molinari, V.; Esposito, D.; Tauer, K.; Antonietti, M. Lignin-Based Polymeric Surfactants for Emulsion Polymerization. Polymer (Guildf) 2017, 112, 418–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergamasco, S.; Tamantini, S.; Zikeli, F.; Vinciguerra, V.; Mugnozza, G.S.; Romagnoli, M. Synthesis and Characterizations of Eco-Friendly Organosolv Lignin-Based Polyurethane Coating Films for the Coating Industry. Polymers (Basel) 2022, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, S.; Wu, L.; Li, T.; Xu, D.; Lin, X.; Wu, C. Facile Preparation of Biomass Lignin-Based Hydroxyethyl Cellulose Super-Absorbent Hydrogel for Dye Pollutant Removal. Int J Biol Macromol 2019, 137, 939–947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, L.; Huang, S.; Zheng, J.; Qiu, Z.; Lin, X.; Qin, Y. Synthesis and Characterization of Biomass Lignin-Based PVA Super-Absorbent Hydrogel. Int J Biol Macromol 2019, 140, 538–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agustiany, E.A.; Ridho, M.R.; Rahmi D. N., M.; Falah, F.; Syamani, A.F. Polymer Composites - 2022 - Agustiany - Recent Developments in Lignin Modification and Its Application in Lignin-based.Pdf. Polym Compos 2022, 43, 4848–4865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Araújo, J.D.P.; Grande, C.A.; Rodrigues, A.E. Vanillin Production from Lignin Oxidation in a Batch Reactor. Chemical Engineering Research and Design 2010, 88, 1024–1032. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Ding, H.; Puglia, D.; Kenny, J.M.; Liu, T.; Guo, J.; Wang, Q.; Ou, R.; Xu, P.; Ma, P.; et al. Bio-renewable Polymers Based on Lignin-derived Phenol Monomers: Synthesis, Applications, and Perspectives. SusMat 2022, 2, 535–568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fache, M.; Darroman, E.; Besse, V.; Auvergne, R.; Caillol, S.; Boutevin, B. Vanillin, a Promising Biobased Building-Block for Monomer Synthesis. Green Chemistry 2014, 16, 1987–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouten, J.; Wróblewska, A.A.; Grit, G.; Noordijk, J.; Gebben, B.; Meeusen-Wierts, M.H.M.; Bernaerts, K. V. Polyamides Containing a Biorenewable Aromatic Monomer Based on Coumalate Esters: From Synthesis to Evaluation of the Thermal and Mechanical Properties. Polym Chem 2021, 12, 2379–2388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagura, K.; Zhang, Y.; Enomoto, Y.; Iwata, T. Synthesis of Highly Thermally Stable Divanillic Acid-Derived Polyamides and Their Mechanical Properties. Polymer (Guildf) 2021, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yagura, K.; Enomoto, Y.; Iwata, T. Synthesis of Fully Divanillic Acid-Based Aromatic Polyamides and Their Thermal and Mechanical Properties. Polymer (Guildf) 2022, 256, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Hou, W.; Huang, Y.; Zhang, T.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Bai, X. A Green Recyclable Vanillin-Based Polymer (Amide–Imide) Vitrimer. J Polym Environ 2023, 32, 1383–1392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Molina-Gutiérrez, S.; Manseri, A.; Ladmiral, V.; Bongiovanni, R.; Caillol, S.; Lacroix-Desmazes, P. Eugenol A Promising Building Block for Synthesis of Radically Polymerizable Monomers. Macromol Chem Phys 2019, 220, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales-Cerrada, R.; Molina-Gutierrez, S.; Lacroix-Desmazes, P.; Caillol, S. Eugenol, a Promising Building Block for Biobased Polymers with Cutting-Edge Properties. Biomacromolecules 2021, 22, 3625–3648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

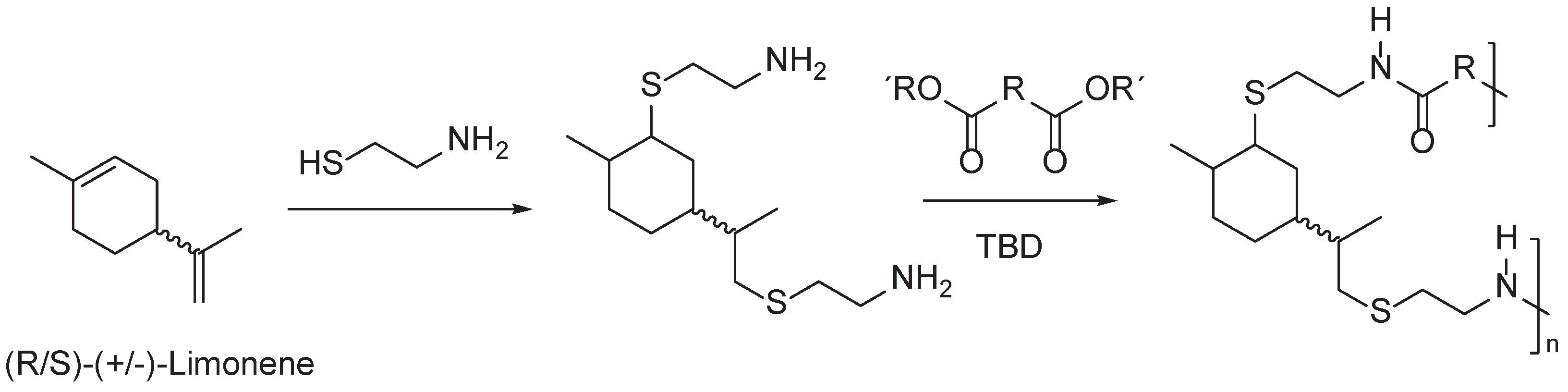

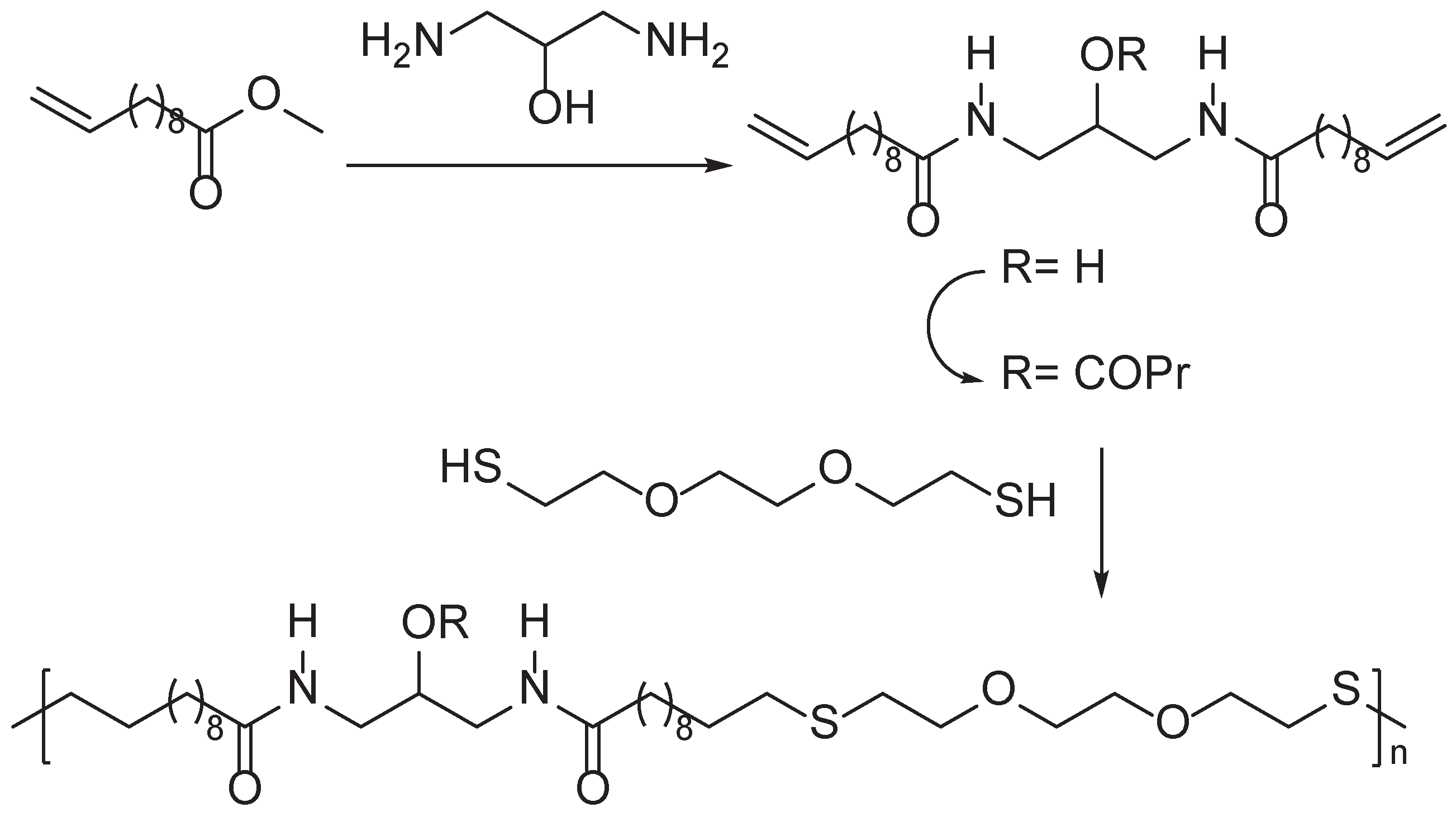

- Diaz-Galbarriatu, M.; Sánchez-Bodón, J.; Laza, J.M.; Moreno-Benítez, I.; Vilas-Vilela, L. Amorphous Sulfur Containing Biobased Polyamides through a Solvent- Free Protocol: Synthesis and Scope. Eur Polym J 2025, 229, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werpy, T.; Petersen, G. Top Value Added Chemicals from Biomass Volume I — Results of Screening for Potential Candidates from Sugars and Synthesis Gas. In Biomass; 2004; p. 19.

- Karlinskii, B.Y.; Ananikov, V.P. Recent Advances in the Development of Green Furan Ring-Containing Polymeric Materials Based on Renewable Plant Biomass. Chem Soc Rev 2022, 52, 836–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hopff, H.; Krieger, A. Über Decarboxylierung Und Dissoziation Heterocyclischer Dicarbonsäuren. Helv Chim Acta 1961, 44, 1058–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hopff, V.H.; Krieger, A. Über Polyamide Aus Heterocyclischen Dicarbonsäuren. Die Makromolekulare Chemie: Macromolecular Chemistry and Physics 1961, 47, 93–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heertjes, P.M.; Kok, G.J. Polycondensation Products of 2,5-Furandicarboxylic Acid. Delft Progress Report Serie A 1974, 1, 59–63. [Google Scholar]

- Grosshardt, O.; Fehrenbacher, U.; Kowollik, K.; Tübke, B.; Dingenouts, N.; Wilhelm, M. Synthese Und Charakterisierung von Polyestern Und Polyamiden Auf Der Basis von Furan-2, 5-Dicarbonsäure. Chem Ing Tech 2009, 81, 1829–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, D.; Flore, J.; Aberson, R.; Adrianus Dam, M.; Duursma, A.; Gruter, G.J.M. Polyamides Containing the Bio-Based 2,5-Furandicarboxylic Acid 2014, WO20150590, 1–9.

- Duursma, A.; Aberson, R.; Smith, D.D.; Dam, M.A.; Johannes, G.; Gruter, M. Process for Preparing a Furan-Based Polyamide, a Furan-Based Oligomer and Compositions and Articles Comprising the Furan-Based Polyamide 2014, WO20150607, 1–8.

- Jiang, Y.; Maniar, D.; Woortman, A.J.J.; Alberda Van Ekenstein, G.O.R.; Loos, K. Enzymatic Polymerization of Furan-2,5-Dicarboxylic Acid-Based Furanic-Aliphatic Polyamides as Sustainable Alternatives to Polyphthalamides. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16, 3674–3685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, W.; Zhai, J.; Zhang, C.; Hu, X.; Zhu, N.; Chen, K.; Guo, K. 100 % Bio-Based Polyamide with Temperature / Ultrasound Dually Triggered Reversible Cross-Linking. Ind Eng Chem Res 2020, 59, 13588–13594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, M.; Zhang, C.; He, B.; Huang, M.; Jiang, S. Synthesis of 2,5-Furandicarboxylic Acid-Based Heat-Resistant Polyamides under Existing Industrialization Process. Macromol Res 2017, 25, 722–729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cureton, L.S.T.; Napadensky, E.; Annunziato, C.; La Scala, J.J. The Effect of Furan Molecular Units on the Glass Transition and Thermal Degradation Temperatures of Polyamides. J Appl Polym Sci 2017, 134, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yeh, I.C.; Rinderspacher, B.C.; Andzelm, J.W.; Cureton, L.T.; La Scala, J. Computational Study of Thermal and Mechanical Properties of Nylons and Bio-Based Furan Polyamides. Polymer (Guildf) 2014, 55, 166–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woroch, C.P.; Cox, I.W.; Kanan, M.W. A Semicrystalline Furanic Polyamide Made from Renewable Feedstocks. J Am Chem Soc 2023, 145, 697–705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kamran, M.; Davidson, M.G.; Tsanaktsis, V.; van Berkel, S.; de Vos, S. Structure-Property Insights of Semi-Aromatic Polyamides Based on Renewable Furanic Monomer and Aliphatic Diamines. Eur Polym J 2022, 178, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fritz-Langhals, E. Unique Superbase TBD (1,5,7-Triazabicyclo [4.4.0]Dec-5-Ene): From Catalytic Activity and One-Pot Synthesis to Broader Application in Industrial Chemistry. Org Process Res Dev 2022, 26, 3015–3023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Yang, J.; Wang, X.; Yang, J. Synthesis of Fully Biobased Semi-Aromatic Furan Polyamides with High Performance through Facile Green Synthesis Process. Eur Polym J 2022, 162, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, S.; Yu, D.; Yao, J.; Wei, Z.; Wang, X.; Yang, J. Synthesis of Biobased Furan Polyamides with Excellent Mechanical Properties: Effect of Diamine Chain Length. J Polym Environ 2024, 32, 3195–3207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y.; Li, X.; Ma, T.; Li, Y.; Ji, D.; Qin, H.; Fang, Z.; He, W.; Guo, K. Preparation of Chemically Recyclable Bio-Based Semi-Aromatic Polyamides Using Continuous Flow Technology under Mild Conditions. Green Chemistry 2024, 26, 5556–5563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Yan, D.; Rong, C.; Yu, L.; Li, J.; Xin, J.; Lu, X.; Zhou, Q.; Wang, Z.; Wei, Z. Efficient Synthesis of High Molecular Weight Semi-Aromatic Polyamides with Biobased Furans over Metal-Free Ionic Liquids. Green Chemistry 2025, 27, 3335–3345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Zhang, G.; Wang, R. Synthesis of Poly(Butylene Succinate) Catalyzed by Tetrabutyl Titanate and Supported by Activated Carbon. Materials 2025, 18, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarzhevskaya, V.P.; Kornev, K.A.; Zmirnova-Zamkova, S.E. No Title. Ukrainskij Khimicheskij Zhurnal 1964, 30. [Google Scholar]

- Mitiakoudis, A.; Gandini, A. Synthesis and Characterization of Furanic Polyamides. Macromolecules 1991, 24, 830–835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mitiakoudis, A.; Gandini, A.; Cheradame, H. Polyamides Containing Furanic Moieties. Polymer communications 1985, 26, 246–249. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, K.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhu, J.; Hu, Z. Semi-Bio-Based Aromatic Polyamides from 2,5-Furandicarboxylic Acid: Toward High-Performance Polymers from Renewable Resources. RSC Adv 2016, 6, 87013–87020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Deng, R.; Rao, G.; Lu, Y.; Wei, Y.; Fu, C.; Yan, X.; Cao, F.; Zhang, D. Synthesis and Characterization of Highly Soluble Wholly Aromatic Polyamides Containing Both Furanyl and Phenyl Units. Journal of Polymer Science 2020, 58, 2140–2150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, K.; Liu, Y.; Yuan, F.; Yang, Y.; Wang, J.; Song, Z.; Li, Z.; Wu, W.; Jiang, M.; Yang, J. Preparation and Properties of an Aromatic Polyamide Fibre Derived from a Bio-Based Furan Acid Chloride. High Perform Polym 2021, 33, 1083–1092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, Z.; Liu, Y.; Chen, W.; Yu, Z.; Fang, Y.; Zhou, X.; He, Y.; Wang, Y.; Tang, Z. Bio-Based, Closed-Loop Chemical Recyclable Aromatic Polyamide from 2,5-Furandicarboxylic Acid: Synthesis, High Performances, and Degradation Mechanism. Eur Polym J 2024, 210, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gharbi, S.; Afli, A.; El Gharbi, R.; Gandini, A. Polyamides Incorporating Furan Moieties: 4. Synthesis, Characterisation and Properties of a Homologous Series. Polym Int 2001, 50, 509–514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abid, S.; El Gharbi, R.; Gandini, A. Polyamides Incorporating Furan Moieties. 5. Synthesis and Characterisation of Furan-Aromatic Homologues. Polymer (Guildf) 2004, 45, 5793–5801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H.H.; Liu, Y.; Han, S.L.; Fang, X.Q.; Wang, C.; Liu, C.M. A Novel Amine-First Strategy Suitable for Preparing Both Functional and Engineering Bio-Polyamides: Furfurylamine as the Sole Furan Source for Bisfuranic Diamine/Diacid Monomers. Polym Chem 2024, 15, 4433–4446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shu, H.H.; Shi, L.Q.; Zhang, H.Q.; Liu, Y.; Han, S.L.; Rao, J.Y.; Liu, C.M. Synthesis of Furan-Based Cationic Biopolyamides and Their Removal Abilities for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances. Chemical Engineering Journal 2025, 507, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Yin, G. Catalytic Transformation of the Furfural Platform into Bifunctionalized Monomers for Polymer Synthesis. ACS Catal 2021, 11, 10058–10083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kainulainen, T.P.; Gowda, V.; Heiskanen, J.P.; Hedenqvist, M.S. Weathering of Furan and 2,2′-Bifuran Polyester and Copolyester Films. Polym Degrad Stab 2022, 200, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagawa, N.; Ogura, T.; Okano, K.; Matsumoto, T.; Nishino, T.; Mori, A. Preparation of Furan Dimer-Based Biopolyester Showing High Melting Points. Chem Lett 2017, 46, 1535–1538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyagawa, N.; Suzuki, T.; Okano, K.; Matsumoto, T.; Nishino, T.; Mori, A. Synthesis of Furan Dimer-Based Polyamides with a High Melting Point. Journal of Polymer Science 2018, 56, 1516–1519. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boncan, D.A.T.; Tsang, S.S.K.; Li, C.; Lee, I.H.T.; Lam, H.M.; Chan, T.F.; Hui, J.H.L. Terpenes and Terpenoids in Plants: Interactions with Environment and Insects. Int J Mol Sci 2020, 21, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tetali, S.D. Terpenes and Isoprenoids: A Wealth of Compounds for Global Use. Planta 2019, 249, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thomsett, M.R.; Moore, J.C.; Buchard, A.; Stockman, R.A.; Howdle, S.M. New Renewably-Sourced Polyesters from Limonene-Derived Monomers. Green Chemistry 2019, 21, 149–156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnacker, M. Terpene-Based Polyamides: A Sustainable Polymer Class with Huge Potential. Curr Opin Green Sustain Chem 2023, 41, 100819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnacker, M.; Tischner, A.; Neumeier, M.; Rieger, B. New Insights into Synthesis and Oligomerization of ε-Lactams Derived from the Terpenoid Ketone (-)-Menthone. RSC Adv 2015, 5, 77699–77705. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stockmann, P.N.; Pastoetter, D.L.; Woelbing, M.; Falckle, C.; Winnacker, M.; Strittmatter, H.; Sieber, V. New Bio-Polyamides from Terpenes: A-Pinene and (+)-3-Carene as Valuable Resources for Lactam Production. Macromol Rapid Commun 2019, 40, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnacker, M.; Sag, J. Sustainable Terpene-Based Polyamides: Via Anionic Polymerization of a Pinene-Derived Lactam. Chemical Communications 2018, 54, 841–844. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleybolte, M.M.; Winnacker, M. From Forest to Future: Synthesis of Sustainable High Molecular Weight Polyamides Using and Investigating the AROP of β-Pinene Lactam. Macromol Rapid Commun 2024, 45, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winnacker, M.; Sag, J.; Tischner, A.; Rieger, B. Sustainable, Stereoregular, and Optically Active Polyamides via Cationic Polymerization of ε-Lactams Derived from the Terpene β-Pinene. Macromol Rapid Commun 2017, 38, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Winnacker, M.; Rieger, B. Recent Progress in Sustainable Polymers Obtained from Cyclic Terpenes: Synthesis, Properties, and Application Potential. ChemSusChem 2015, 8, 2455–2471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Trumbo, D.L. Synthesis of Polyamides Based on 1,8-Diamino-p-Menthane. J Polym Sci A Polym Chem 1988, 26, 2859–2862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Firdaus, M.; Meier, M.A.R. Renewable Polyamides and Polyurethanes Derived from Limonene. Green Chemistry 2013, 15, 370–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

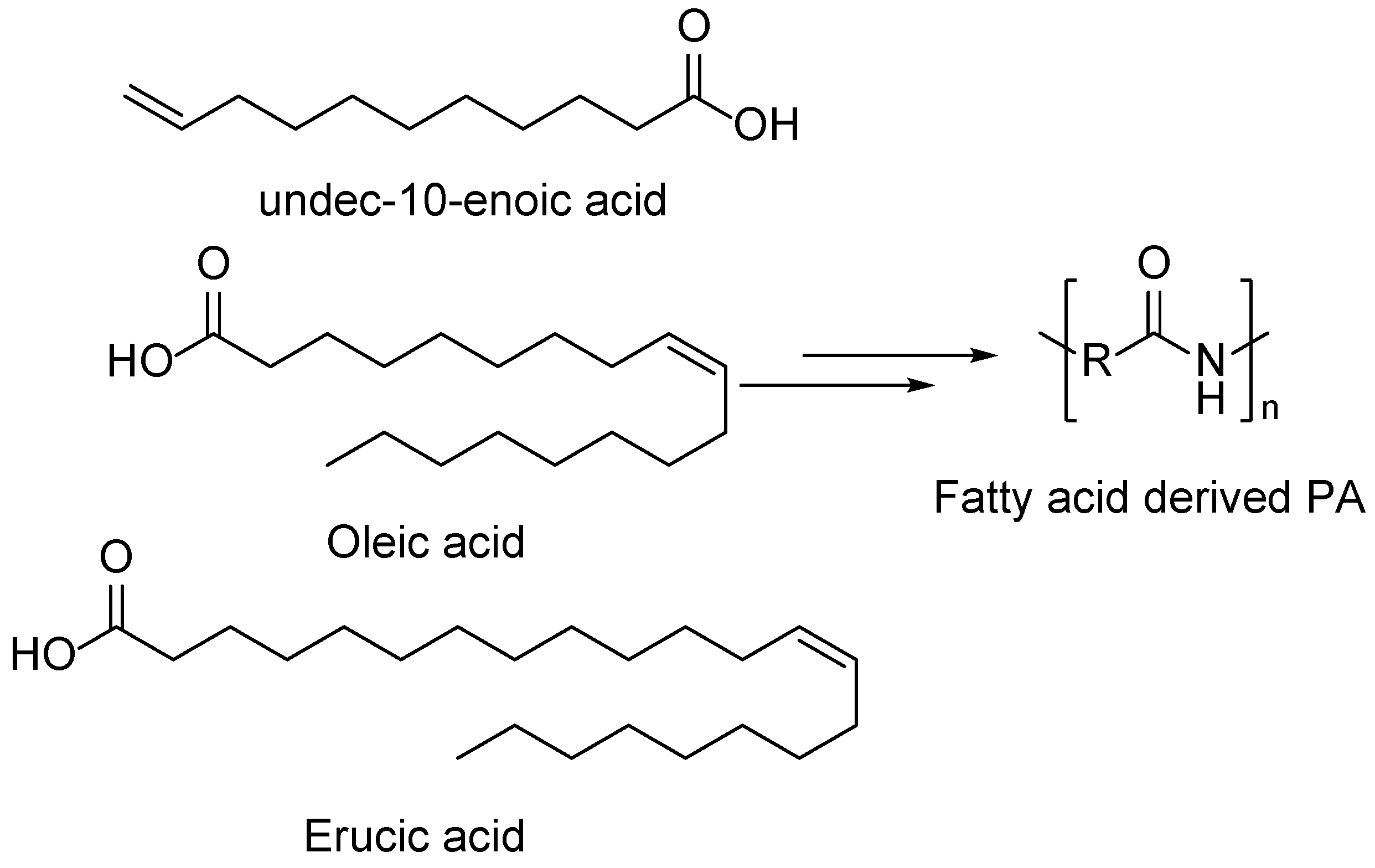

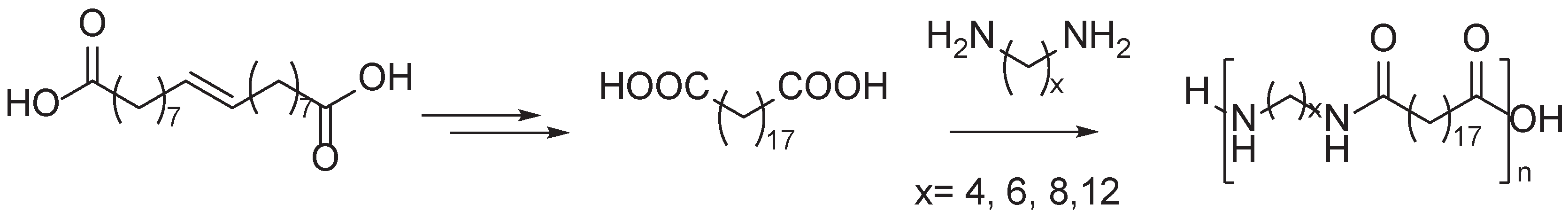

- Meier, M.A.R. Plant-Oil-Based Polyamides and Polyurethanes: Toward Sustainable Nitrogen-Containing Thermoplastic Materials. Macromol Rapid Commun 2018, 40, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rist, M.; Greiner, A. Synthesis, Characterization, and the Potential for Closed Loop Recycling of Plant Oil-Based PA X.19 Polyamides. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2022, 10, 16793–16802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

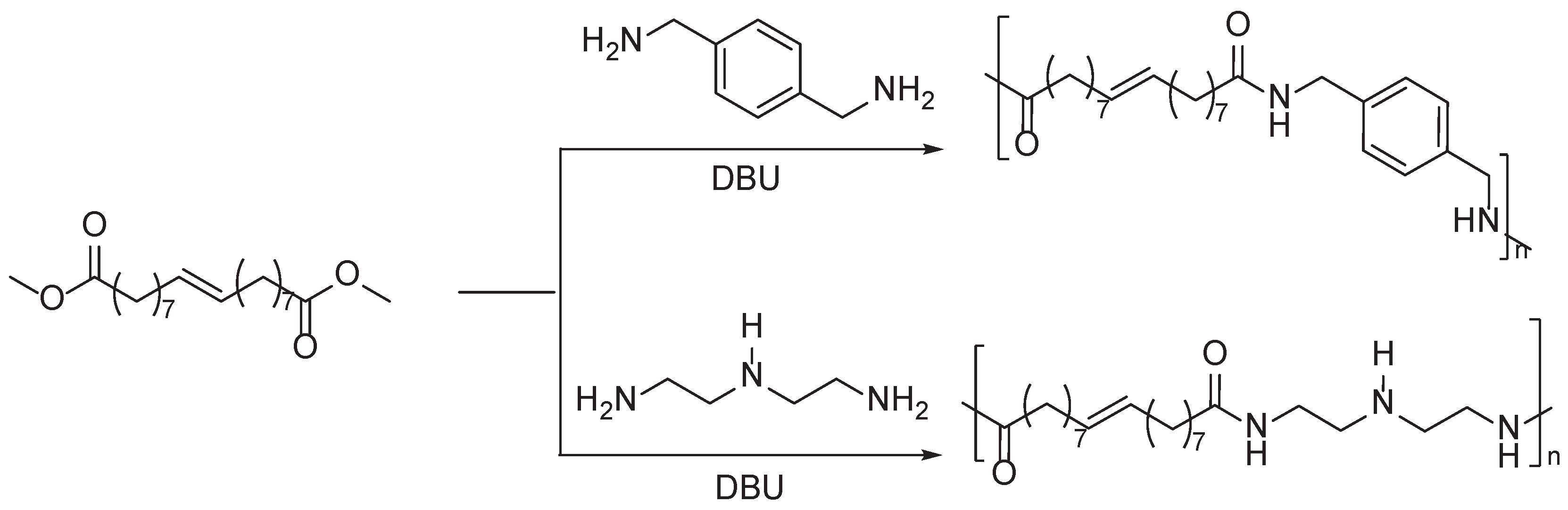

- Türünç, O.; Firdaus, M.; Klein, G.; Meier, M.A.R. Fatty Acid Derived Renewable Polyamides via Thiol-Ene Additions. Green Chemistry 2012, 14, 2577–2583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

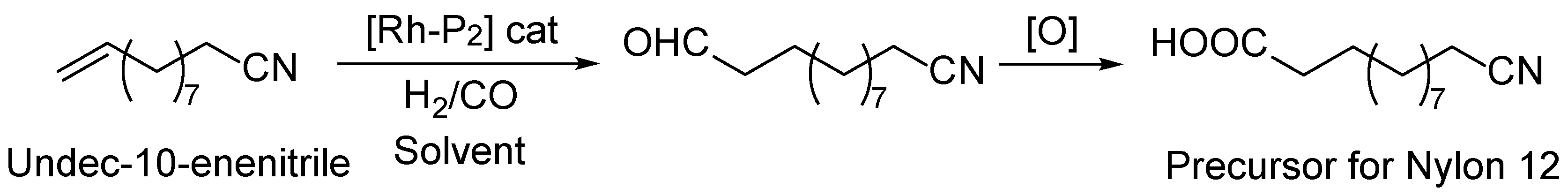

- Ternel, J.; Counturier, J.-L.; Dubois, J.-L.; Carpentier, J.-F. Rhodium-Catalyzed Tandem Isomerization/Hydroformylation of the Bio-Sourced 10-Undecenenitrile: Selective and Productive Catalyst for Production of Polyamide-12 Precursor. Advan Synthetic Catal 2013, 355, 3191–3204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

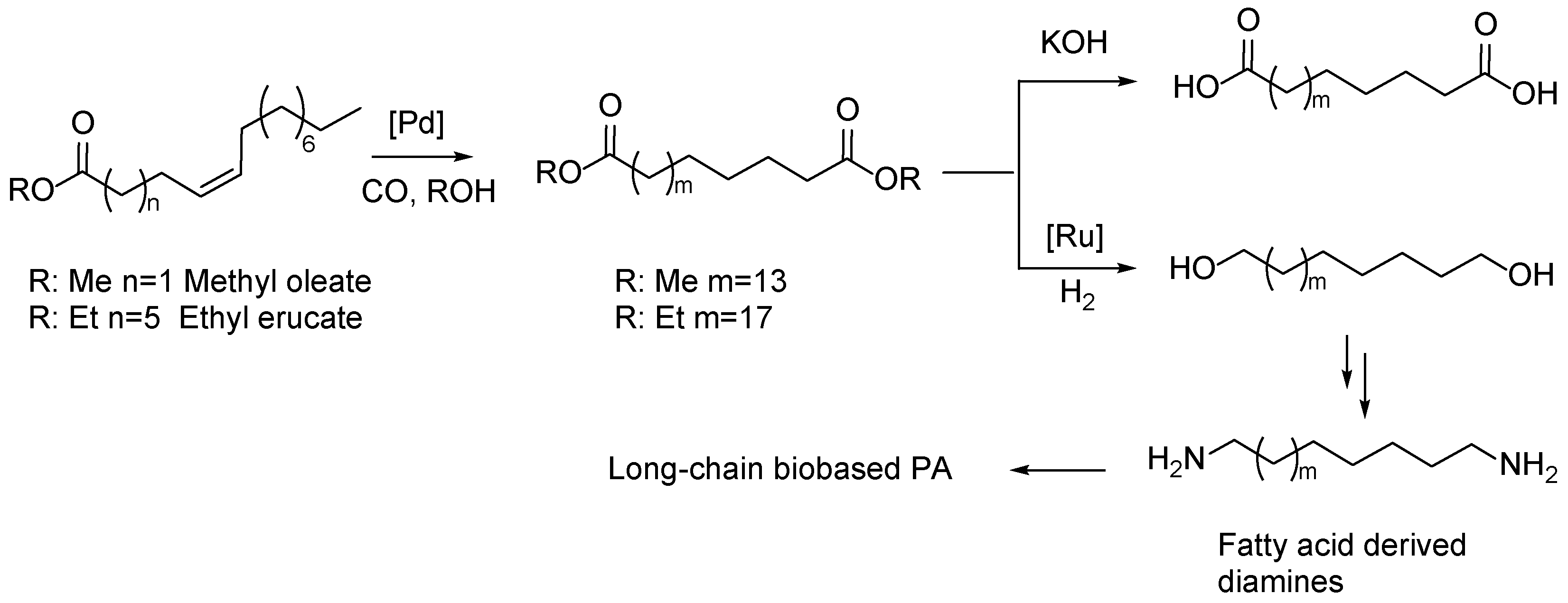

- Stempfle, F.; Quinzler, D.; Heckler, I.; Mecking, S. Long-Chain Linear C19 and C23 Monomers and Polycondensates from Unsaturated Fatty Acid Esters. Macromolecules 2011, 44, 4159–4166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, M.; Meier, M.A.R. Highly Efficient Oxyfunctionalization of Unsaturated Fatty Acid Esters: An Attractive Route for the Synthesis of Polyamides from Renewable Resources. Green Chemistry 2014, 16, 1784–1788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Czapiewski, M.; Meier, M.A.R. Synthesis of Dimer Fatty Acid Methyl Esters by Catalytic Oxidation and Reductive Amination: An Efficient Route to Branched Polyamides. European Journal of Lipid Science and Technology 2018, 120, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winkler, M.; Meier, M.A.R. Olefin Cross-Metathesis as a Valuable Tool for the Preparation of Renewable Polyesters and Polyamides from Unsaturated Fatty Acid Esters and Carbamates. Green Chemistry 2014, 16, 3335–3340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krzesiński, P.; César, V.; Grela, K.; Santos, S.; Ortiz, P. Cross-Metathesis of Technical Grade Methyl Oleate for the Synthesis of Bio-Based Polyesters and Polyamides. RSC Sustainability 2023, 1, 2033–2037. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, L.; Zhu, T.; Yuan, L.; Zhou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Tang, C. Ultra-Strong Long-Chain Polyamide Elastomers with Programmable Supramolecular Interactions and Oriented Crystalline Microstructures. Nat Commun 2019, 10, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ahmadi, R.; Ullah, A. Synthesis and Characterization of Unsaturated Biobased-Polyamides from Plant Oil. ACS Sustain Chem Eng 2020, 8, 8049–8058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).