Submitted:

05 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

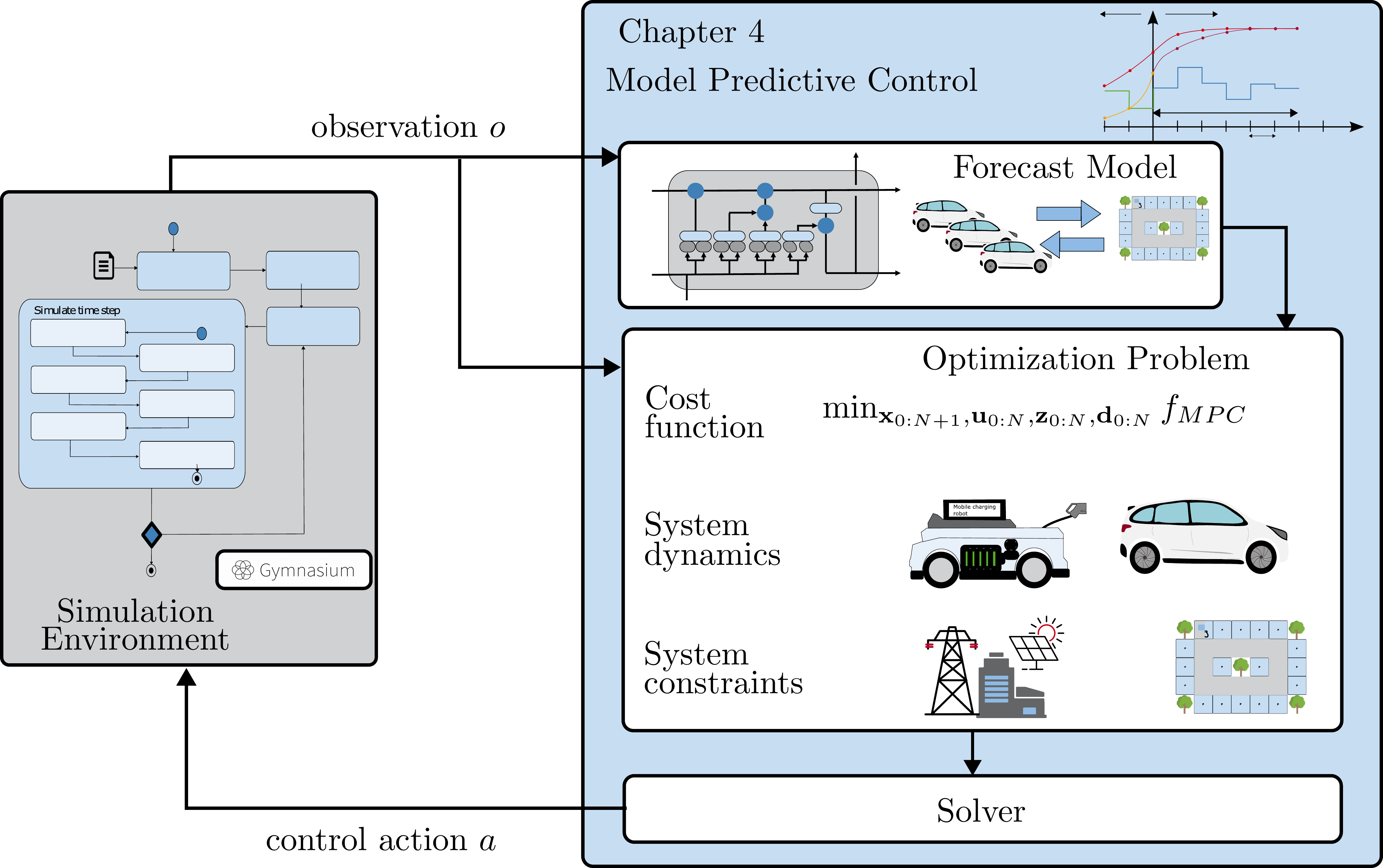

- Adaption of optimization problem for MPC-based charging management with mobile charging robots (MCRs)

- Forecast model based on long short-term memory (LSTM) networks for EV arrivals

- Evaluation of the MPC controller in the simulation environment and comparison of performance with perfect forecast, LSTM based forecast and terminal penalty

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Optimization Problem for MPC

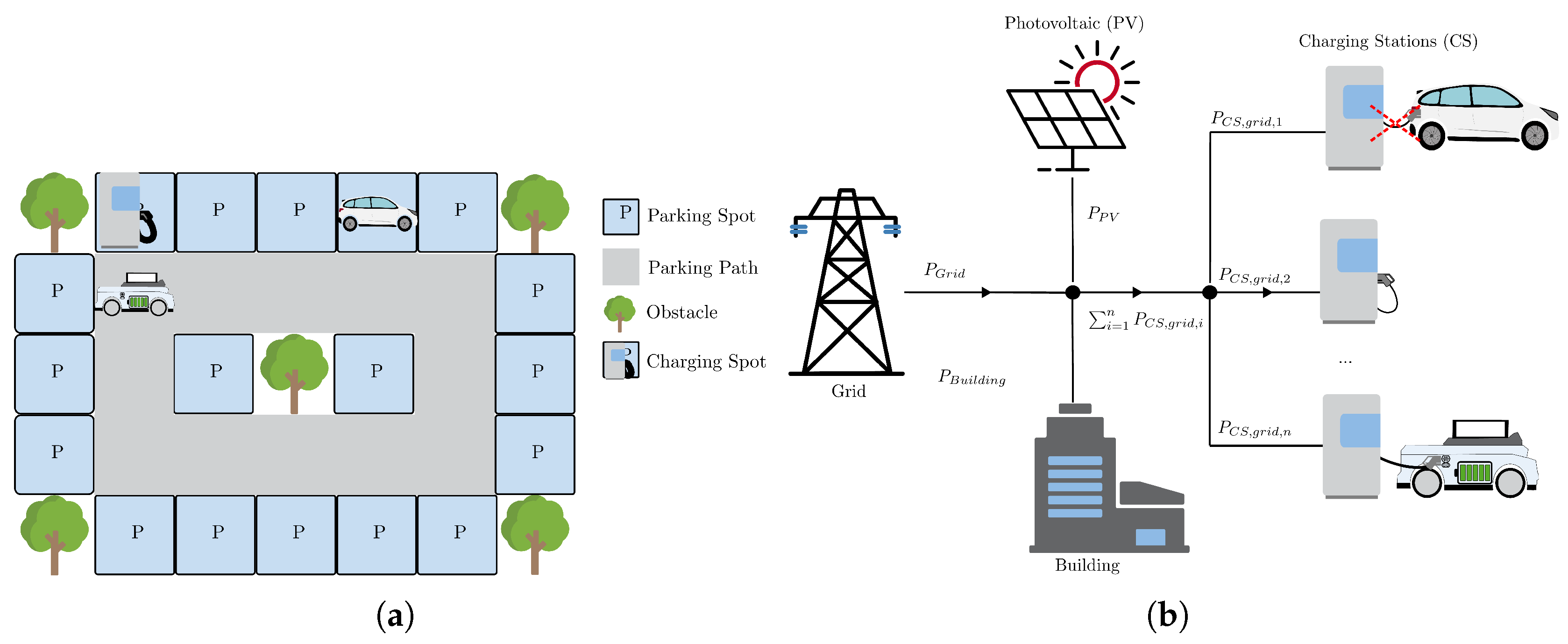

- Prediction horizon index , denoting the discrete step within the prediction horizon . The “absolute” time step index based on the current time would be .

- Mobile Charging Robot (MCR) index , identifying the specific MCR under consideration.

- Charging station index , referring to a specific charging station or charger location.

- Parking field index , indicating the designated parking field under consideration.

- Binary variables: All binary variables are indicated by use of the symbol . indicates the MCR r is located at CS c. The abbreviation “mtc” is used to denote “move to charger”. indicates the MCR r is located at parking field f. The abbreviation “mtp” is used to denote “move to parking field”.

- Sign convention for continuous variables: The continuous variables describing power satisfy .

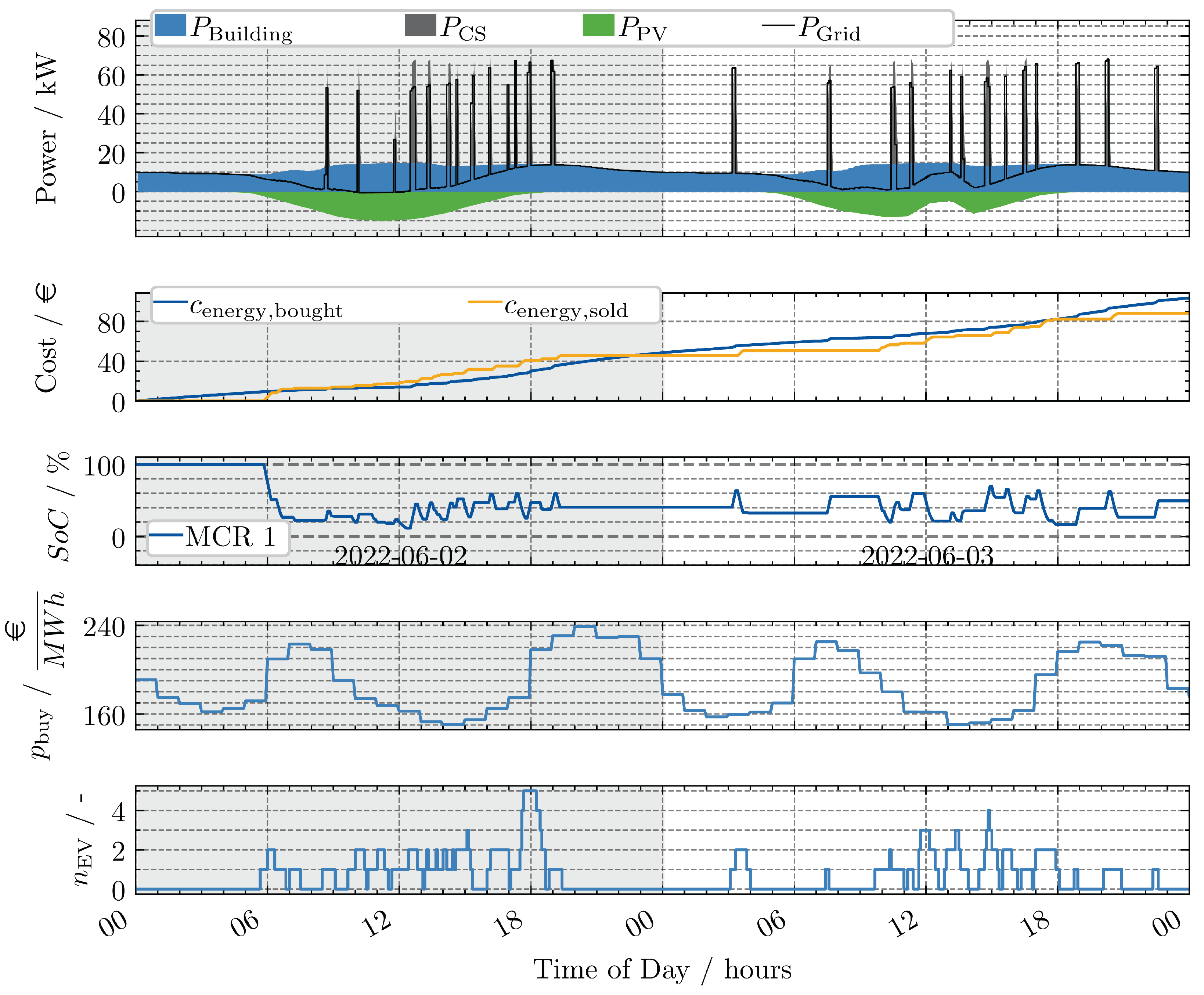

2.2. Limitations of the Initial Approach

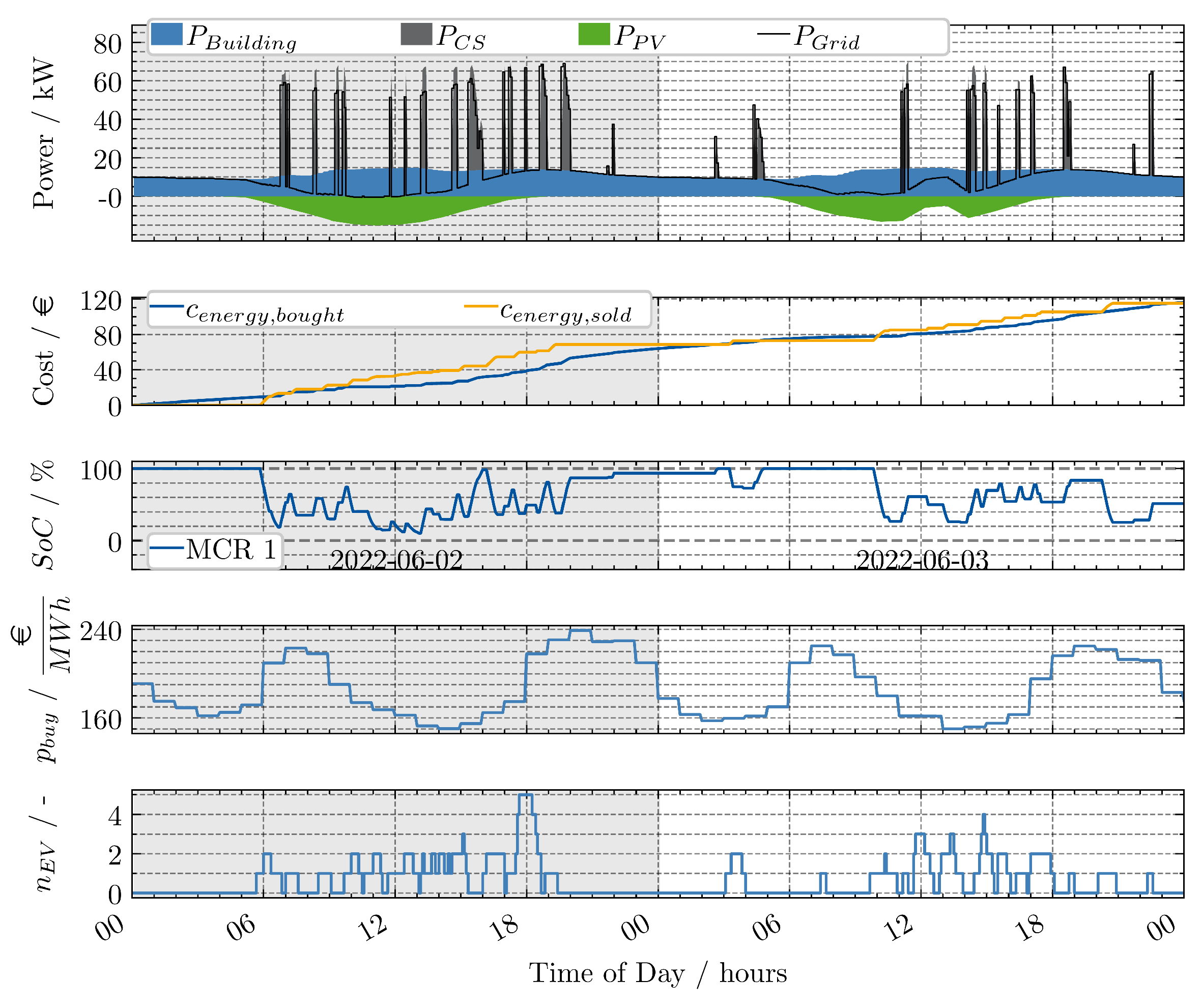

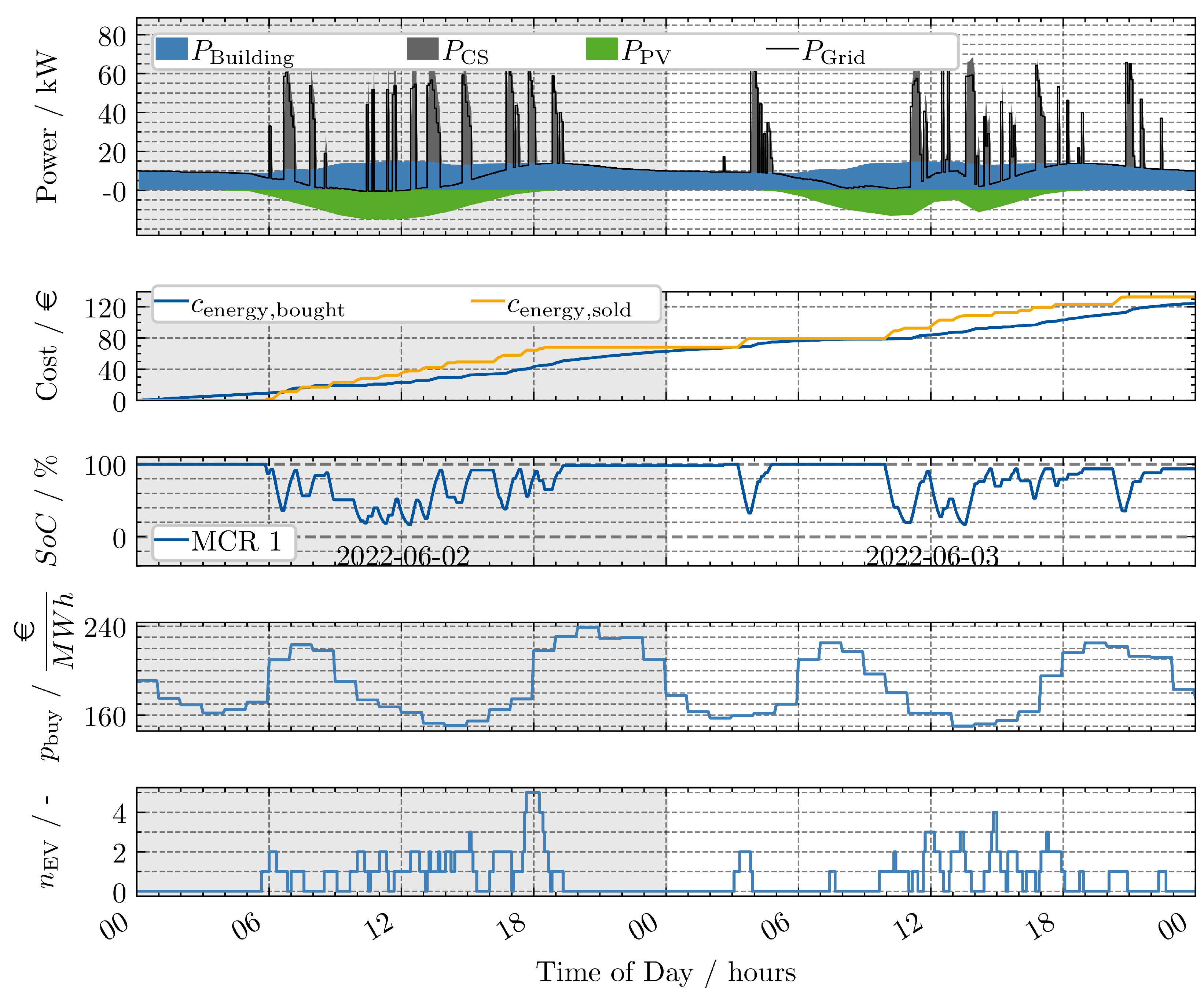

- No recharging without EVs present: In general the MCR only recharges if EVs are present, which is strategically not a good time, because until the MCR is recharged the EVs might have left. Especially during the period between 20:00 h and 04:00 h there are no EVs at the parking area. Therefore, the MCR could recharge. Due to the structure of the optimization problem, where recharging is only attractive if an EV is present to which the charged energy could be sold, this does not happen.

- No “smart” charging: It is observed that, in most cases, the MCR operates at a high power level of approximately 50 kW. However, the charging times do not correspond to periods of low energy costs (refer to plot (d)) or periods of high PV power. It is hypothesized that if charging times and power were to be synchronized with electricity prices and PV power, costs could be reduced.

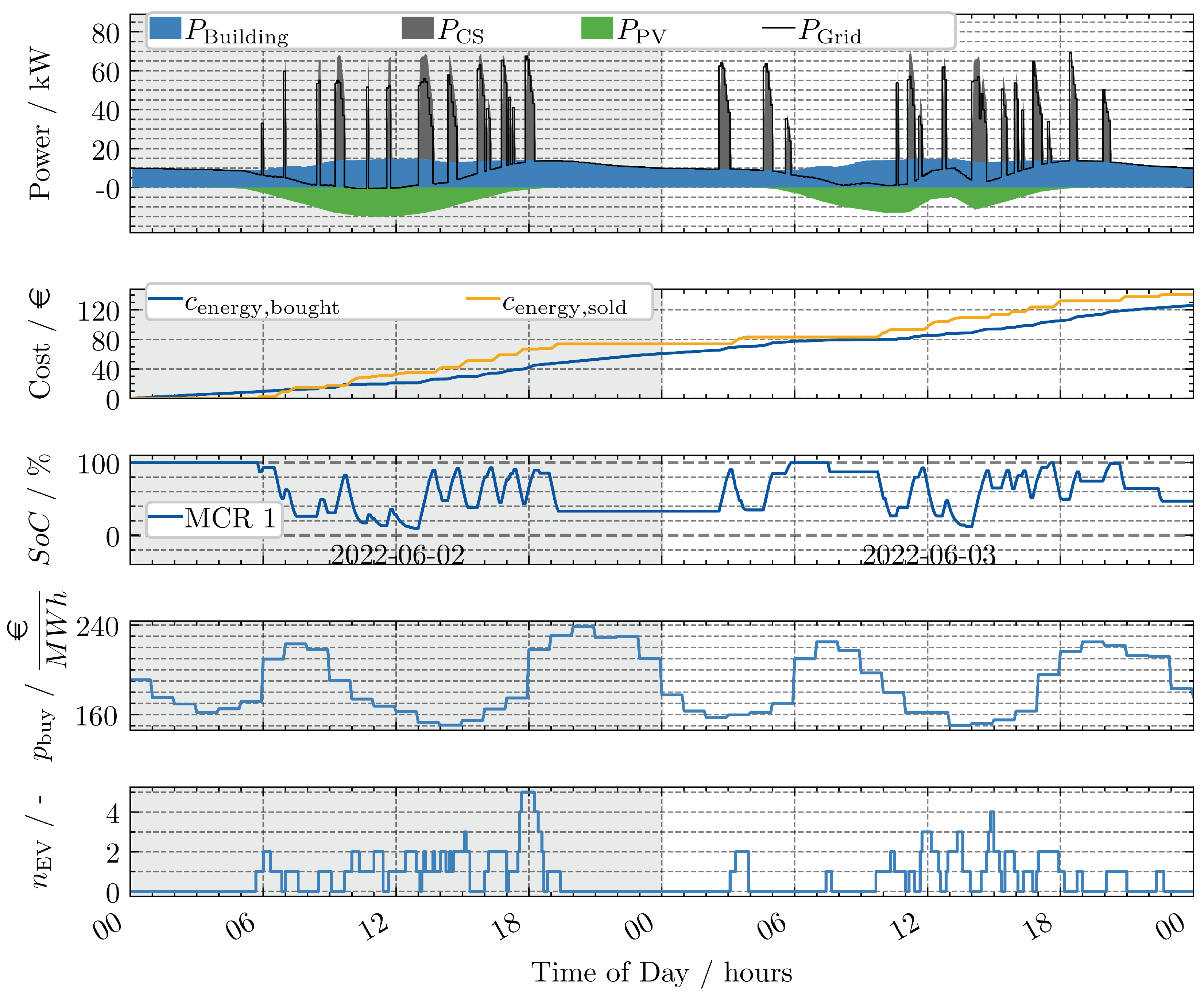

2.3. Penalty for Not Recharging

- Mobile Charging Robots (MCRs) should recharge even if there are no EVs present at the parking area currently or within the prediction horizon. Thus, not recharging should incur higher (virtual) costs compared to recharging.

- The charging of an EV should still take priority over the MCR recharging itself.

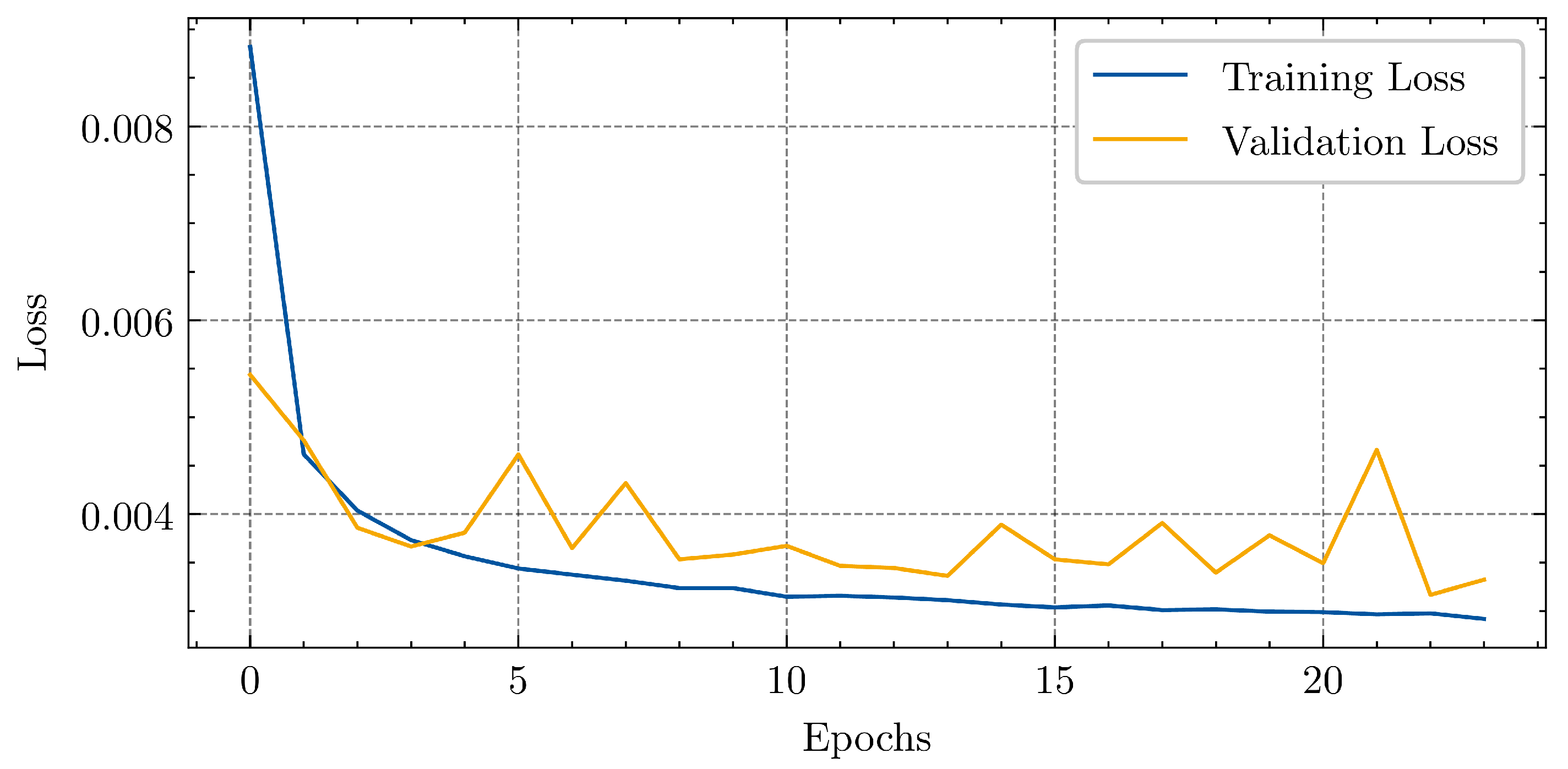

2.4. LSTM Forecasting for MPC

- Dataset: Within the synthetic dataset, there is an assumption regarding how the data is distributed, which might not account for the actual distribution observed in a real dataset. This would need careful investigation and suitable data, ideally coming from an actual field trial with MCRs.

- Input Features: The input features of the LSTM are selected as a minimum set. For comprehensive forecasting, more input features would need to be applied. For example, it can be assumed that at holidays, fewer people charge at a supermarket.

3. Results

3.1. Terminal Penalty

3.2. Perfect Forecast as Reference

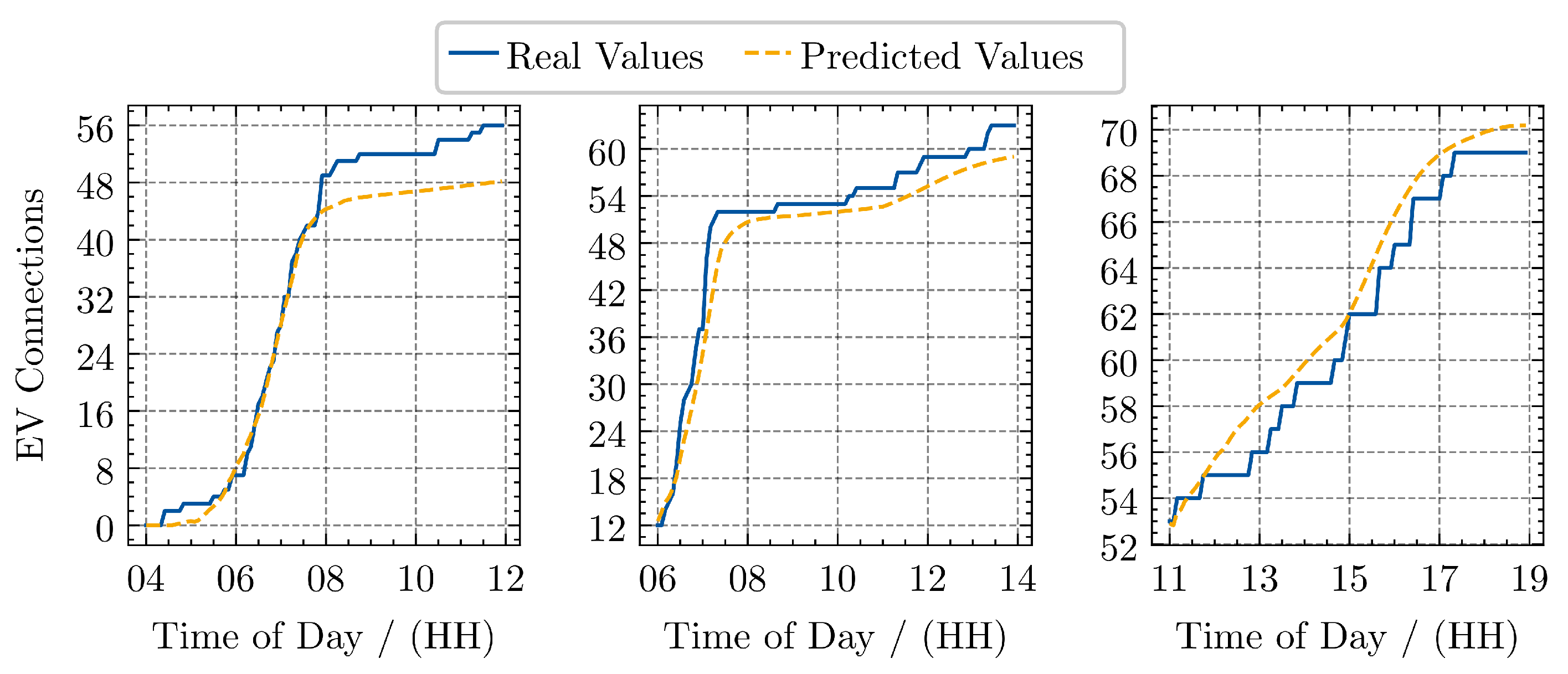

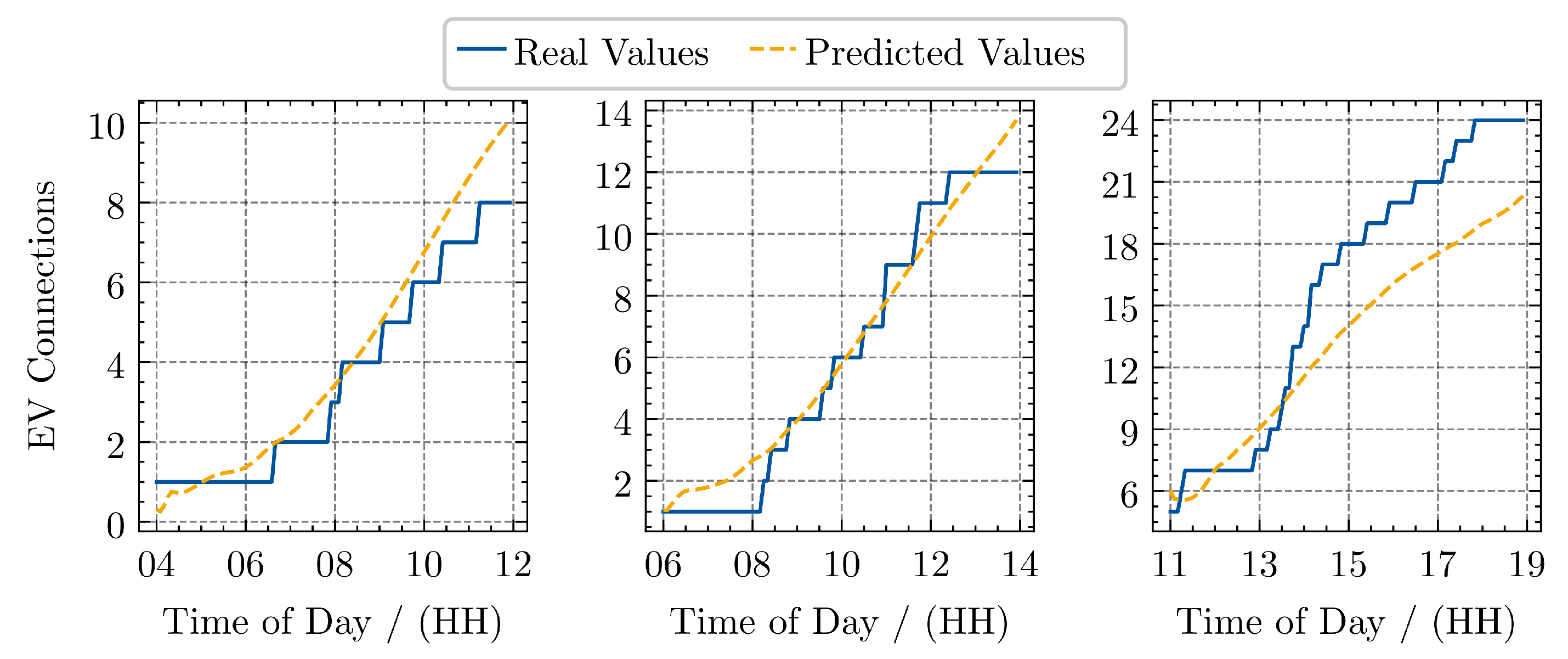

3.3. LSTM Forecasting

4. Discussion

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| CS | Charging Station |

| EV | Electric Vehicle |

| MCR | Mobile Charging Robot |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory |

| MPC | Model Predictive Control |

| MILP | Mixed Integer Linear Programming |

| OP | Optimization Problem |

| SoC | State of Charge |

| AI | Artificial Intelligence |

Appendix A

| Setting | Value | Description |

|---|---|---|

| MIP Gap | 0.1 | Specifies the relative optimality gap tolerance. The solver will stop when the gap between the best integer solution found and the best bound on the objective function is within 10%. |

| Time Limit | 600 | Sets a limit on the total time (in seconds) that the solver can spend on solving a problem. In this case, it is set to 10 minutes. |

| Presolve | 2 | Controls presolve aggressiveness. A value of 2 indicates aggressive presolve, which attempts extensive simplifications before solving. |

| Node Limit | 500 | Limits the number of branch-and-bound nodes that are explored during optimization to avoid excessive computation time. |

| Heuristics | 0.5 | Adjusts heuristic search effort level; a value of 0.5 increases heuristic searches, potentially finding good solutions faster but not necessarily improving exactness. |

References

- Mobility and Transport. Europeans are generally positive towards e-mobility, 2024.

- International Energy Agency. Global EV Outlook 2024, 2024.

- Wessel, P.; Faßbender, M.; Gerz, J.; Andert, J. Designing a Prototype of a Mobile Charging Robot for Charging of Electric Vehicles. In Proceedings of the SAE Technical Paper Series; Wessel, P., Faßbender, M., Gerz, J., Andert, J., Eds.; SAE International400 Commonwealth Drive: Warrendale, PA, United States, 2024. SAE Technical Paper Series. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Faßbender, M.; Rößler, N.; Eisenbarth, M.; Andert, J. An Electric Vehicle Charging Simulation to Investigate the Potential of Intelligent Charging Strategies. [CrossRef]

- Towers, M.; Kwiatkowski, A.; Terry, J.; Balis, J.U.; de Cola, G.; Deleu, T.; Goulão, M.; Kallinteris, A.; Krimmel, M.; KG, Arjun.; et al. Gymnasium: A Standard Interface for Reinforcement Learning Environments.

- Huang, Q.; Yang, L.; Jia, Q.S.; Qi, Y.; Zhou, C.; Guan, X. A Simulation-Based Primal-Dual Approach for Constrained V2G Scheduling in a Microgrid of Building. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2023, 20, 1851–1863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Yang, L.; Hou, C.; Zeng, Z.; Qi, Y. Event-Based EV Charging Scheduling in a Microgrid of Buildings. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification 2023, 9, 1784–1796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Q.; Jia, Q.S.; Guan, X. A Multi-Timescale and Bilevel Coordination Approach for Matching Uncertain Wind Supply With EV Charging Demand. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2017, 14, 694–704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fallah-Mehrjardi, O.; Yaghmaee, M.H.; Leon-Garcia, A. Charge Scheduling of Electric Vehicles in Smart Parking-Lot Under Future Demands Uncertainty. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2020, 11, 4949–4959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Fang, H.; Xu, D.; Jiang, B.; Shi, P. A Stochastic Model Predictive Control Based Energy Management Approach for Microgrids with Electric Vehicles. IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification 2024, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, H.T.; Choi, D.H. Distributionally Robust Model Predictive Control for Smart Electric Vehicle Charging Station With V2G/V2V Capability. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2023, 14, 4621–4633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ju, Y.; Zeng, T.; Allybokus, Z.; Moura, S. Robo-Chargers: Optimal Operation and Planning of a Robotic Charging System to Alleviate Overstay. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2024, 15, 770–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, L.; Geng, X.; Guan, X.; Tong, L. EV Charging Scheduling Under Demand Charge: A Block Model Predictive Control Approach. IEEE Transactions on Automation Science and Engineering 2024, 21, 2125–2138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Yeh, H.G.; Nguyen, R. A Robust Model Predictive Control-Based Scheduling Approach for Electric Vehicle Charging With Photovoltaic Systems. IEEE Systems Journal 2023, 17, 111–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Amore, G.; Cabrera-Tobar, A.; Petrone, G.; Pavan, A.M.; Spagnuolo, G. Integrating model predictive control and deep learning for the management of an EV charging station. Mathematics and Computers in Simulation 2024, 224, 33–48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClone, G.; Ghosh, A.; Khurram, A.; Washom, B.; Kleissl, J. Hybrid Machine Learning Forecasting for Online MPC of Work Place Electric Vehicle Charging. IEEE Transactions on Smart Grid 2024, 15, 1891–1901. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hermans, B.; Walker, S.; Ludlage, J.; Özkan, L. Model predictive control of vehicle charging stations in grid-connected microgrids: An implementation study. Applied Energy 2024, 368, 123210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bynum, M.L.; Hackebeil, G.A.; Hart, W.E.; Laird, C.D.; Nicholson, B.L.; Siirola, J.D.; Watson, J.P.; Woodruff, D.L. Pyomo — Optimization Modeling in Python; Springer International Publishing: Cham, 2021; Vol. 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertsimas, D.; Tsitsiklis, J.N. Introduction to linear optimization; Athena scientific books; Dynamic Ideas and Athena Scientific: Belmont, Massachusetts, 1997; Vol. 7. [Google Scholar]

- Gurobi Optimization, LLC. Gurobi Optimizer Reference Manual; 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Z.J.; Li, T.; Low, S.H. ACN-Data: Analysis and Applications of an Open EV Charging Dataset. In Proceedings of the Proceedings of the Tenth International Conference on Future Energy Systems, 2019, e-Energy ’19.

- ISO 15118-2:2014; Road Vehicles – Vehicle to Grid Communication Interface – Part 2: Network and Application Protocol Requirements. International Organization for Standardization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2014. https://www.iso.org/standard/55366.html.

| Parameter | Description | Value |

|---|---|---|

| Number of CS on parking area | 1 | |

| Maximum charging power of the CS | 50 kW | |

| Yearly consumption of supermarket building | 200000 | |

| Peak power of installed PV array | 20 | |

| Average arriving EVs per hour | 1 | |

| Number of MCR in the environment | 1 | |

| Number of parking fields in environment | 8 |

| Variable | Raw Value | Processing | Processed Variable |

|---|---|---|---|

| Time of Day (ToD) | Sin/Cos Encoding: | , | |

| Day of Week (DoW) | Sin/Cos Encoding | , | |

| Accumulated arrived EVs | normalized accumulated arrived EVs | ||

| Accumulated arrived EVs | normalized accumulated arrived EVs |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).