Submitted:

07 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Materials

2.2. Preparation of Rotenone Solid Nanodispersion (Rot–SND)

2.3. Orthogonal Design of Experiments

2.4. Particle Size and Size Distribution Measurements

2.5. Zeta-Potential Measurements

2.6. Storage Stability Evaluation of Rot–SND

2.7. Crystalline State Analysis of Rot–SND

2.8. Morphology Observation

2.9. Contact Angle and Retention Measurements

2.10. Determination of Rot–SND Photostability

2.11. Bioassays

2.13. Statistical Analysis

3. Results and Discussions

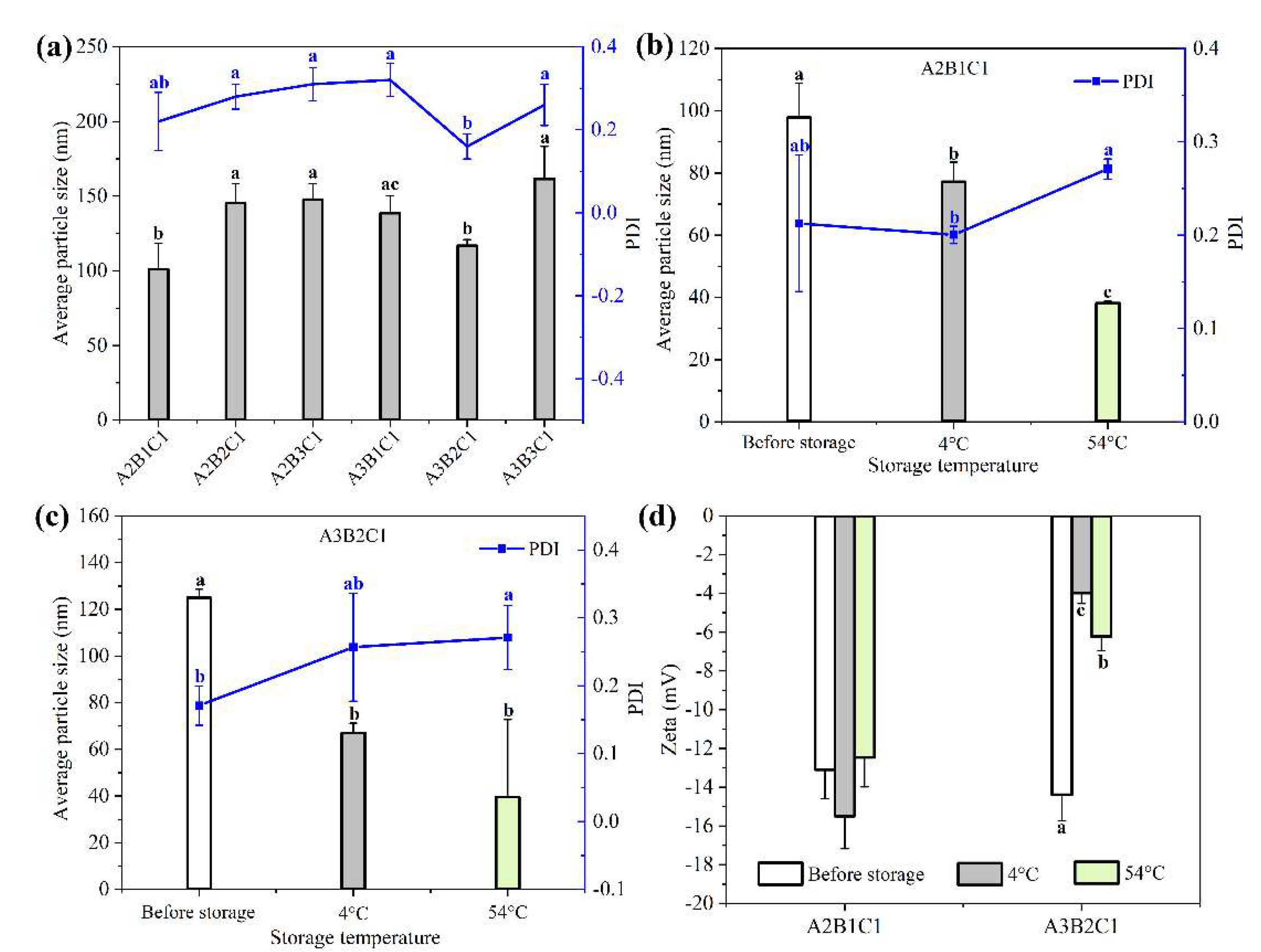

3.1. Optimization of Rot–SND Recipe Parameters

3.2. Morphology and Particle Size of the Target Rot–SND

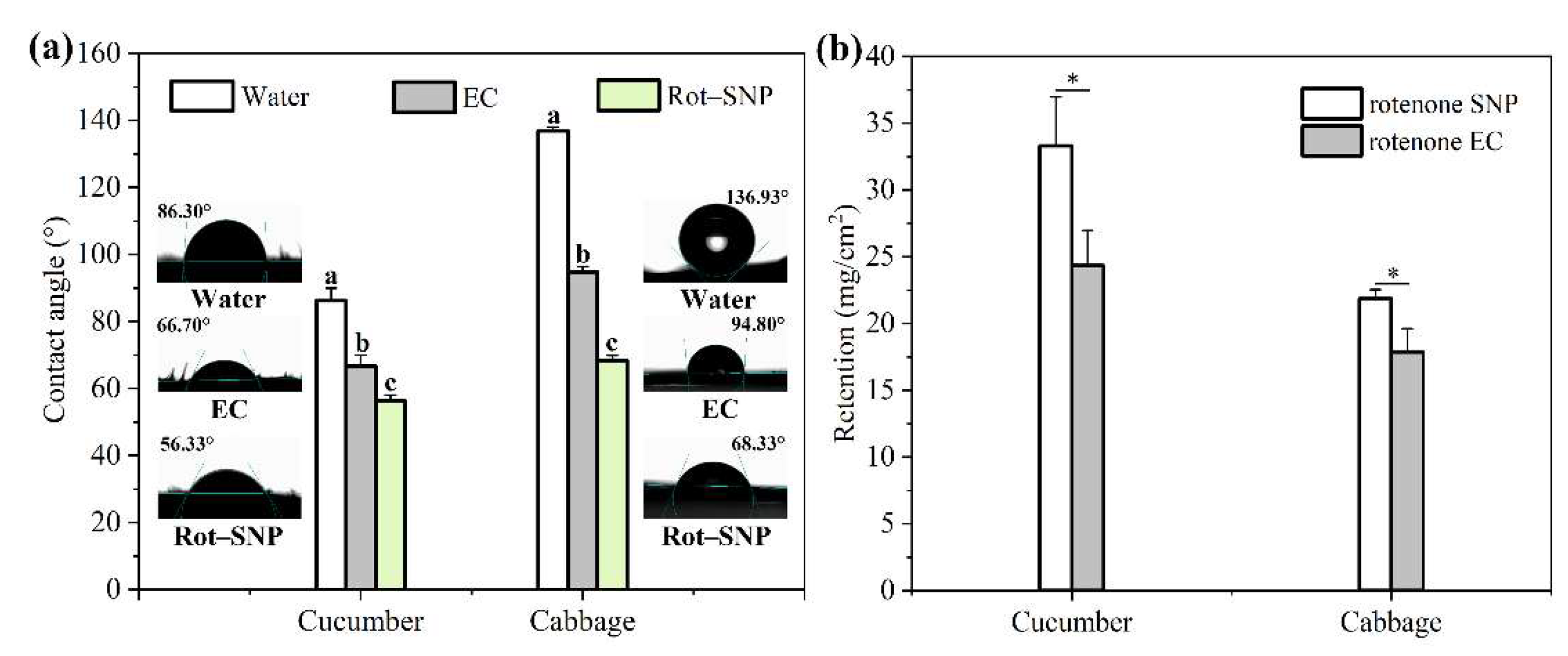

3.3. Wettability and Retention of Rot–SND

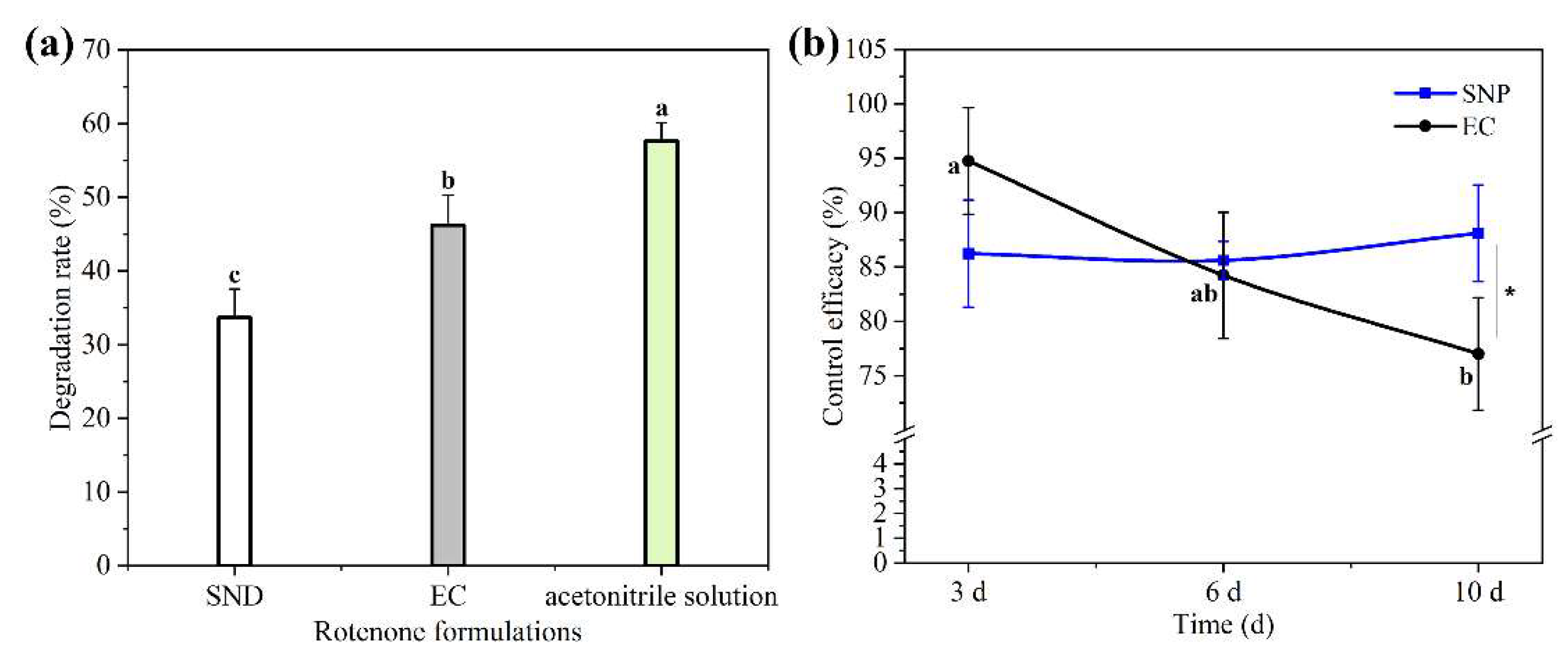

3.4. Photostability of Rot–SND

3.5. Indoor Toxicity of Rot–SND Against Aphis gossypii

3.6. Field Efficacy of Rot–SND Against A. gossypii

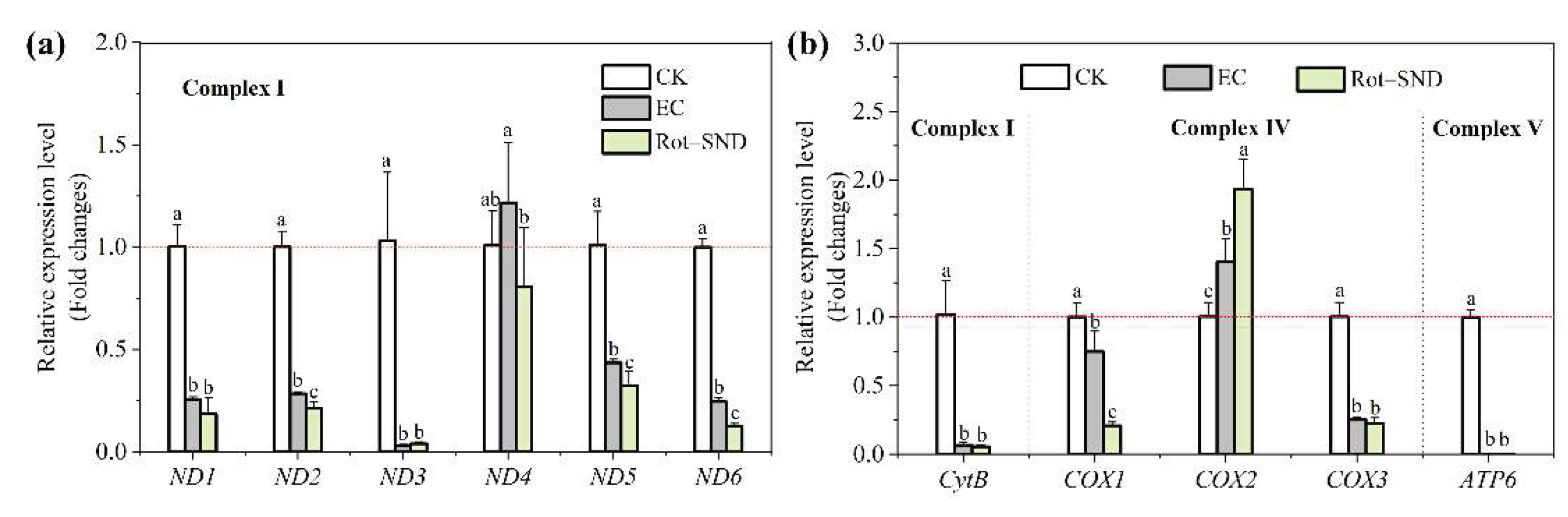

3.7. Effect of Rot–SND on the Mitochondrial Gene Expression in A. gossypii

3.8. Toxicity of Rot–SND Toward Nontarget Mosquito Larvae

4. Conclusions

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| Rot | Rotenone |

| SND | Solid nanodispersion |

| Rot–SND | Rotenone solid nanodispersion |

| EC | Emulsifiable concentrates |

References

- Isman, M. B. Botanical insecticides in the twenty-first century-fulfilling their promise? Annu. Rev. Entomol. 2020, 65, 233–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarmah, K.; Anbalagan, T. Marimuthu, M.; Mariappan, P.; Angappan, S.; Vaithiyanathan, S. Innovative formulation strategies for botanical- and essential oil-based insecticides. J. Pest Sci. 2025, 98, 1–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modafferi, A.; Giunti, G.; Benelli, G.; Campolo, O. Ecological costs of botanical nano-insecticides. Curr. Opin. Environ. Sci. Health. 2024, 42, 100579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Z.; Wang, S.; Yang, L.; Hou, R.; Wang, R.; Zhang, N.; Wang, Y.; Li, C.; Tan, Y.; Huang, S.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Z. Rotenone encapsulated in pH-responsive alginate-based microspheres reduces toxicity to zebrafish. Environ. Res. 2023, 216, 114565. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xu, W.; Shen, D.; Chen, X.; Zhao, M.; Fan, T.; Wu, Q.; Meng, Z.; Cui, J. Rotenone nanoparticles based on mesoporous silica to improve the stability, translocation and insecticidal activity of rotenone. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2023, 30, 106047–106058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muda, M. S.; Kamari, A.; Bakar, S. A.; Yusoff, S. N. M.; Fatimah, I.; Phillip, E.; Din, S. M. Chitosan-graphene oxide nanocomposites as water-solubilising agents for rotenone pesticide. J. Mol. Liq. 2020, 318, 114066. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Q.; Qin, D.; Wang, R.; Yan, W.; Zhao, W.; Shen, S.; Huang, S.; Cheng, D.; Zhao, C.; Zhang, Z. Novel application of biodegradable chitosan in agriculture: Using green nanopesticides to control Solenopsis invicta. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2022, 220, 193–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Mu, X.; Liu, H.; Yong, Q.; Ouyang, X.; Liu, Y.; Zheng, L.; Chen, H.; Zhai, Y.; Ma, J.; Meng, L.; Liu, S.; Zheng, H. Rotenone impairs brain glial energetics and locomotor behavior in bumblebees. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 907, 167870. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, Y.; Liu, X.; Feng, Y.; Nie, X.; Liu, Q.; Du, X.; Wu, Y.; Liu, T.; Zhu, X. Rotenone, an environmental toxin, causes abnormal methylation of the mouse brain organoid’s genome and ferroptosis. Int. J. Med. Sci. 2022, 19, 1184–1197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhan, I.; Siddique, Y. H. Effect of Rotenone on the Neurodegeneration among Different Models. Curr. Drug Targets 2024, 25, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Oliveira, J. L.; Campos, E. V. R.; Bakshi, M.; Abhilash, P. C.; Fraceto, L. F. Application of nanotechnology for the encapsulation of botanical insecticides for sustainable agriculture: Prospects and promises. Biotechnol. Adv. 2014, 32, 1550–1561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vishnu, M.; Kannan, M.; Soundararajan, R. P.; Suganthi, A.; Subramanian, A.; Senthilkumar, M.; Rameash, K.; Madesh, K.; Govindaraju, K. Nano-bioformulations: emerging trends and potential applications in next generation crop protection. Environ. Sci. Nano 2024, 11, 2831–2860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, J.; Liu, H.; Gu, W.; Yan, Z.; Xu, Z.; Yang, Y.; Zhu, X.; Li, Y. A delivery strategy for rotenone microspheres in an animal model of Parkinson’s disease. Biomaterials 2006, 27, 937–946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ouyang, Y.; Li, Y.; Chen, C.; Zhao, S.; Wu, M.; Zhou, B.; Cao, Y.; Liu, H. Copper phosphate-rotenone nanocomposites for tumor therapy through autophagy blockage-enhanced triphosadenine supply interruption and lipid peroxidation accumulation. Chem. Eng. J. 2024, 495, 153435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Meng, Z.; Ren, Y.; Gu, H.; Lu, C.-l. J. J. A. S. Effects of ZnO nanoparticle on photo-protection and insecticidal synergism of rotenone. J. Agric. Sci. 2016, 8, 38–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamari, A.; Aljafree, N. F. A.; Yusoff, S. N. M. Oleoyl-carboxymethyl chitosan as a new carrier agent for the rotenone pesticide. Environ. Chem. Lett. 2016, 14, 417–422. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljafree, N. F. A.; Kamari, A. Synthesis, characterisation and potential application of deoxycholic acid carboxymethyl chitosan as a carrier agent for rotenone. J. Polym. Res. 2018, 25, 133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamari, A.; Aljafree, N. F. A.; Yusoff, S. N. M. N,N-dimethylhexadecyl carboxymethyl chitosan as a potential carrier agent for rotenone. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2016, 88, 263–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bidyarani, N.; Kumar, U. J. R. A. Synthesis of rotenone loaded zein nano-formulation for plant protection against pathogenic microbes. RSC Adv. 2019, 9, 40819–40826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Gao, F.; Cui, B.; Du, Q.; Zeng, Z.; Zhao, X.; Sun, C.; Wang, Y.; Cui, H. The key factors of solid nanodispersion for promoting the bioactivity of abamectin. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2024, 201, 105897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, F.; Cui, B.; Wang, C.; Li, X.; Li, B.; Zhan, S.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, X.; Sun, C.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Cui, H. Nano-EMB-SP improves the solubility, foliar affinity, photostability and bioactivity of emamectin benzoate. Pest Manag. Sci. 2022, 78, 3717–3724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.; Cui, B.; Yang, D.; Wang, C.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sun, C.; Zhao, X.; Cui, H. Preparation and evaluation of emamectin benzoate solid microemulsion. J. Nanomaterials 2016, 2016, 2386938. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, B. B.; Liu, D. X.; Liu, D. K.; Wu, G. Application of solid dispersion technique to improve solubility and sustain release of emamectin benzoate. Molecules 2019, 24, 4315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ding, X.; Gao, F.; Chen, L.; Zeng, Z.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Cui, H.; Cui, B. Size-dependent effect on foliar utilization and biocontrol efficacy of emamectin benzoate delivery systems. ACS Appl. Mater. Interfaces 2024, 16, 22558–22570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, B.; Gao, F.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, C.; Wang, Y.; Sun, C.; Zhao, X.; Guo, L.; Shen, Y.; Liu, G.; Cui, H. Construction and characterization of avermectin B2 solid nanodispersion. Sci. Rep. 2020, 10, 9096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cui, B.; Zhao, X.; Wang, Y.; Zeng, Z.; Sun, C.; Yang, D.; Liu, G.; Cui, H. Optimization and characterization of lambda-cyhalothrin solid nanodispersion by self-dispersing method. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 380–389. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Guo, L.; Yao, J.; Wang, A.; Gao, F.; Zhao, X.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sun, C.; Cui, H.; Cui, B. Preparation, characterization and antifungal activity of pyraclostrobin solid nanodispersion by self-emulsifying technique. Pest Manag. Sci. 2019, 75, 2785–2793. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, T.; Chen, F.; Ding, X.; Gao, F.; Du, Q.; Zeng, Z.; Cui, H.; Cui, B. Preparation and synergistic effect of composite solid nanodispersions for co-delivery of prochloraz and azoxystrobin. Agronomy 2025, 15, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ge, Z.; Gao, Z.; Sun, R.; Zheng, L. Mix design of concrete with recycled clay-brick-powder using the orthogonal design method. Constr. Build. Mater. 2012, 31, 289–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Cui, B.; Zhao, X.; Zeng, Z.; Wang, Y.; Sun, C.; Guo, L.; Cui, H. Preparation and characterization of efficient and safe lambda-cyhalothrin nanoparticles with tunable particle size. Pest Manag. Sci. 2021, 77, 2078–2086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.-J.; Xu, H.-H.; Yang, W.; Liu, S.-Z. Research on the effect of photoprotectants on photostabilization of rotenone. J. Photochem. Photobiol. B 2009, 95, 93–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, X.; Tie, M.; Chen, A.; Ma, K.; Li, F.; Liang, P.; Liu, Y.; Song, D.; Gao, X. Pyrethroid resistance associated with M918 L mutation and detoxifying metabolism in from Bt cotton growing regions of China. Pest Manag. Sci. 2017, 73, 2353–2359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Song, Y.; Liu, X.; Zhao, K.; Ma, R.; Wu, W.; Zhang, Y.; Duan, L.; Li, X.; Xu, H.; Cheng, M.; Qin, B.; Qi, Z. A new endophytic Penicillium oxalicum with aphicidal activity and its infection mechanism. Pest Manag. Sci. 2024, 80, 5706–5717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- WHO Guidelines for laboratory and field testing of mosquito larvicides. WHO/CDS/WHOPES/GCDPP/200513.

- Abbott, W. S. A method of computing the effectiveness of an insecticide. J. Econ. Entomol. 1925, 18, 265–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Luo, J.; Wang, C.; Lv, L.; Li, C.; Jiang, W.; Cui, J.; Rajput, L. B. Complete mitochondrial genome of Aphis gossypii Glover (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Mitochondrial DNA A DNA Mapp. Seq. Anal. 2016, 27, 854–855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, K. S.; Li, F.; Liang, P. Z.; Chen, X. W.; Liu, Y.; Gao, X. W. Identification and validation of reference genes for the normalization of gene expression data in qRT-PCR analysis in Aphis gossypii (Hemiptera: Aphididae). J. Insect Sci. 2016, 16, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badmus, S. O.; Amusa, H. K.; Oyehan, T. A.; Saleh, T. A. Environmental risks and toxicity of surfactants: overview of analysis, assessment, and remediation techniques. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2021, 28, 62085–62104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naylor, C. G.; Castaldi, F. J.; Hayes, B. J. Biodegradation of nonionic surfactants containing propylene oxide. J. Am. Oil Chem. Soc. 1988, 65, 1669–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Li, F.; Bai, L.; Yang, X.; Wu, Z. Adsorption, aggregation, and application properties of green pluronic aliphatic alcohol ether carboxylic acids and nonionic/amphoteric surfactants in water. Langmuir 2024, 40, 24338–24349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Additives, E. Panel o.; Feed, P. o. S. u. i. A.; Bampidis, V.; Azimonti, G.; Bastos, M. d. L.; Christensen, H.; Dusemund, B.; Fašmon Durjava, M.; Kouba, M.; López-Alonso, M.; López Puente, S.; Marcon, F.; Mayo, B.; Pechová, A.; Petkova, M.; Ramos, F.; Sanz, Y.; Villa, R. E.; Woutersen, R.; Aquilina, G.; Bories, G.; Gropp, J.; Nebbia, C.; Innocenti, M. Safety and efficacy of a feed additive consisting of glyceryl polyethyleneglycol ricinoleate (PEG castor oil) for all animal species (FEFANA asbl). EFSA J. 2022, 20, e07433. [Google Scholar]

- Kunduru, K. R.; Basu, A.; Haim Zada, M.; Domb, A. J. Castor oil-based biodegradable polyesters. Biomacromolecules 2015, 16, 2572–2587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bergström, L. Hamaker constants of inorganic materials. Adv. Colloid Interface Sci. 1997, 70, 125–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, P.; Ghosh, A.; Wagner, R. F.; Krill, S.; Joshi, Y. M.; Serajuddin, A. T. M. Effect of combined use of nonionic surfactant on formation of oil-in-water microemulsions. Int. J. Pharm. 2005, 288, 27–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, L.; Liparoti, S.; Della Porta, G.; Adami, R.; Marqués, J. L.; Urieta, J. S.; Mainar, A. M.; Reverchon, E. Rotenone coprecipitation with biodegradable polymers by supercritical assisted atomization. J. Supercrit. Fluids 2013, 81, 48–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malkawi, R.; Malkawi, W. I.; Al-Mahmoud, Y.; Tawalbeh, J. Current trends on solid dispersions: past, present, and future. Adv. Pharm. Pharm. Sci. 2022, 2022, 5916013. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Jiang, Q.; Xu, Z.; Yang, Q.; Hao, G.; Liu, M.; Zeng, Z. Recent progress on crystal nucleation of amorphous solid dispersion. Cryst. Growth Des. 2024, 24, 8655–8666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, X.; Hu, Y.; Liu, L.; Su, L.; Li, N.; Yu, J.; Tang, B.; Yang, Z. Physical stability of amorphous solid dispersions: a physicochemical perspective with thermodynamic, kinetic and environmental aspects. Pharm. Res. 2018, 35, 125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tian, B.; Zhang, L.; Pan, Z.; Gou, J.; Zhang, Y.; Tang, X. A comparison of the effect of temperature and moisture on the solid dispersions: Aging and crystallization. Int. J. Pharm. 2014, 475, 385–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Raoux, S.; Rettner, C. T.; Jordan-Sweet, J. L.; Kellock, A. J.; Topuria, T.; Rice, P. M.; Miller, D. C. Direct observation of amorphous to crystalline phase transitions in nanoparticle arrays of phase change materials. J. Appl. Phys. 2007, 102, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, C.; Zhao, T.; Zhao, Y.; Zhang, G. Effects of oxyethylene groups on the adsorption behavior and application performance of long alkyl chain phosphate surfactants. J. Mol. Liq. 2022, 345, 117044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Chen, W.; Jing, M.; Liu, S.; Feng, J.; Wu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, X.; Ma, Z. Self-assembled mixed micelle loaded with natural pyrethrins as an intelligent nano-insecticide with a novel temperature-responsive release mode. Chem. Eng. J. 2019, 361, 1381–1391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhattacharjee, S. DLS and zeta potential – What they are and what they are not? J. Con. Rel. 2016, 235, 337–351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Müller, K. H.; Motskin, M.; Philpott, A. J.; Routh, A. F.; Shanahan, C. M.; Duer, M. J.; Skepper, J. N. The effect of particle agglomeration on the formation of a surface-connected compartment induced by hydroxyapatite nanoparticles in human monocyte-derived macrophages. Biomaterials 2014, 35, 1074–1088. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lao, S. B.; Zhang, Z. X.; Xu, H. H.; Jiang, G. B. Novel amphiphilic chitosan derivatives: Synthesis, characterization and micellar solubilization of rotenone. Carbohydr. Polym. 2010, 82, 1136–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, H. A.; Love, S. The solubility of rotenone. II. Data for certain additional solvents. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1937, 59, 2694–2696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, M.; Sun, J.; Kuang, W.; Zhou, L.; Han, D.; Gong, J. Drug–drug multicomponent crystals of epalrestat: A novel form of the drug combination and improved solubility and photostability of epalrestat. Cryst. Growth Des. 2022, 22, 5027–5035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grooff, D.; Francis, F.; De Villiers, M. M.; Ferg, E. Photostability of crystalline versus amorphous nifedipine and nimodipine. J. Pharm. Sci. 2013, 102, 1883–1894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geng, N.; Chen, J.-M.; Li, Z.-J.; Jiang, L.; Lu, T.-B. Approach of co-crystallization to improve the solubility and photostability of tranilast. Cryst. Growth Des. 2013, 13, 3546–3553. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Chen, F.; Ding, X.; Gao, F.; Du, Q.; Zeng, Z.; Cui, H.; Cui, B. Preparation and synergistic effect of composite solid nanodispersions for co-delivery of prochloraz and azoxystrobin. Agronomy 2025, 15, 683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Z.; Xue, L.; Li, Y.; Cui, G.; Sun, R.; Hu, M.; Zhong, G. Rotenone-induced necrosis in insect cells via the cytoplasmic membrane damage and mitochondrial dysfunction. Pestic. Biochem. Physiol. 2021, 173, 104801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Subhan, I.; Siddique, Y. H. Effect of rotenone on the neurodegeneration among different models. Curr. Drug Targets 2024, 25, 530–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Niu, R.; Gao, X.; Luo, J.; Wang, L.; Zhang, K.; Li, D.; Ji, J.; Cui, J.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, S. Mitochondrial genome of Aphis gossypii Glover cucumber biotype (Hemiptera: Aphididae). Mit. DNA B Resour. 2021, 6, 922–924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, B. X.; Wang, W. C.; Zhang, X.P.; Zhang, D. X.; Ren, Y. P.; Gao, Y.; Mu, W.; Liu, F. Using co-ordination assembly as the microencapsulation strategy to promote the efficacy and environmental safety of pyraclostrobin. Adv. Funct. Mater. 2017, 27, 1701841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dalu, T.; Wasserman, R. J.; Jordaan, M.; Froneman, W. P.; Weyl, O. L. F. An assessment of the effect of rotenone on selected non-target aquatic fauna. PLoS One 2015, 10, e0142140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yenesew, A.; Derese, S.; Midiwo, J. O.; Heydenreich, M.; Peter, M. G. Effect of rotenoids from the seeds of Millettia dura on larvae of Aedes aegypti. Pest Manag. Sci. 2003, 59, 1159–1161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prud’homme, S. M.; Chaumot, A.; Cassar, E.; David, J.-P.; Reynaud, S. Impact of micropollutants on the life-history traits of the mosquito Aedes aegypti: On the relevance of transgenerational studies. Environ. Pollut. 2017, 220, 242–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Calma, M. L.; Medina, P. M. B. Acute and chronic exposure of the holometabolous life cycle of Aedes aegypti L. to emerging contaminants naproxen and propylparaben. Environ. Pollut. 2020, 266, 115275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Levels | Variables | ||

| Rot/surfactant (A) | Ethylan 992/EL–80 (B) | Carriers (C) | |

| 1 | 1:3 | 4:6 | Lactose |

| 2 | 1:4 | 5:5 | Galactose |

| 3 | 1:5 | 6:4 | Sodium benzoate |

| Serial number | Factors1 | Particle size (nm) | PDI | |||

| A | B | C | D | |||

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 161.70±3.81 | 0.25±0.06 |

| 2 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 181.80±2.46 | 0.29±0.02 |

| 3 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 293.60±6.85 | 0.40±0.02 |

| 4 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 141.20±8.43 | 0.24±0.04 |

| 5 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 233.10±14.13 | 0.22±0.04 |

| 6 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 152.10±9.69 | 0.23±0.04 |

| 7 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 239.60±10.23 | 0.22±0.05 |

| 8 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 122.80±6.94 | 0.19±0.03 |

| 9 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 | 138.70±6.78 | 0.20±0.02 |

| Particle size | ||||||

| k1 | 212.37 | 180.83 | 145.53 | 177.83 | ||

| k2 | 175.47 | 179.23 | 153.90 | 191.17 | ||

| k3 | 167.03 | 194.80 | 255.43 | 185.87 | ||

| R | 45.33 | 15.57 | 109.90 | 13.33 | ||

| PDI | ||||||

| k1 | 0.31 | 0.24 | 0.22 | 0.23 | ||

| k2 | 0.23 | 0.24 | 0.24 | 0.25 | ||

| k3 | 0.21 | 0.28 | 0.28 | 0.28 | ||

| R | 45.33 | 0.04 | 0.06 | 0.05 | ||

| Formulations | Regression curve | LC50 (μg a.i./mL) | 95% confidence limit | χ2 |

| Rot–SND | y=0.67x–1.16 | 1.45±0.48 | 0.88–2.23 | 0.48 |

| EC | y=0.72x–0.46 | 4.36±0.87* | 2.88–6.42 | 0.73 |

| Formulations | Regression curve | LC50 (μg a.i./mL) | 95% confidence limit | χ2 |

| Rot–SND | y=2.67x–2.52 | 8.79±0.49* | 7.42–12.22 | 4.01 |

| EC | y=2.01x–0.85 | 2.63±0.44 | 1.41–3.95 | 6.19 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).