1. Introduction

Maternal mortality is defined as the death of a woman during pregnancy, childbirth or up to 42 days after the end of pregnancy, due to causes related to pregnancy or its management, excluding accidental or incidental causes. It is an important indicator of the quality of health care provided to pregnant and postpartum women, and is used globally as a parameter to assess the effectiveness of health systems. Monitoring maternal mortality allows us to identify failures in prenatal, obstetric and postpartum care, and is essential for guiding public policies [

1].

The concept of maternal near miss refers to women who survived potentially fatal complications during pregnancy, childbirth or the postpartum period, representing an important opportunity to evaluate the care provided, without fatal outcomes. The study of near miss cases allows us to understand the fine line between life and maternal death and helps identify avoidable failures in care. This type of analysis has gained prominence as a complementary instrument for monitoring maternal mortality, especially in countries with decreasing rates of maternal deaths [

2].

The main causes of maternal mortality in Brazil include hypertensive disorders during pregnancy (such as pre-eclampsia and eclampsia), hemorrhages, puerperal infections and complications resulting from unsafe abortions. These causes are, in most cases, preventable with adequate and timely care. Although Brazil has recorded a reduction in the maternal mortality ratio (MMR) in recent decades, the figures are still above the parameters recommended by the World Health Organization (WHO), highlighting the persistence of inequalities in access to and quality of obstetric care [

3,

4].

The epidemiological panorama of maternal mortality in Brazil reveals significant regional disparities. The North and Northeast regions have the highest rates, reflecting socioeconomic inequalities, limited access to health services, and a shortage of trained professionals. In addition, factors such as skin color, education level, and maternal age directly influence obstetric outcomes. Reducing these inequities requires structural investments, strengthening primary health care, and improving the quality of obstetric and neonatal care [

5,

6].

The worsening of regional inequalities in the country plays a central role in this panorama. Data show the formation of high mortality clusters in states such as Amazonas, Maranhão and Bahia, reinforcing the association between maternal mortality and socioeconomic indicators such as low income, reduced education and poor access to health services [

5]. In addition to maternal deaths, Brazil also needs to consider cases of near miss, in which women narrowly survive serious complications during pregnancy, childbirth or the postpartum period. An analysis of hospital records of more than 24,000 postpartum women in 465 hospitals across all regions of Brazil, with the aim of correcting official data and identifying risk factors underlying maternal deaths [

7] emphasized that monitoring these events can anticipate risks, promote better care practices and reduce maternal mortality, also pointing out that inadequate care during prenatal care and childbirth care are important determinants of these events [

8].

Many maternal deaths occur in the postpartum period, especially after hospital discharge, indicating failures in continuity of care [

9]. Another worrying aspect is the increase in maternal deaths associated with COVID-19, which has brutally exposed the weaknesses of the health system. Black, indigenous and low-income women have been the most affected, reinforcing the intersectional impact of race, gender and class in determining maternal outcomes [

3,

10].

During the COVID-19 pandemic, Brazil recorded a significant increase in maternal mortality. In 2021, the MMR reached 107.53 deaths per 100,000 live births, almost double the rate of 55.31 recorded in 2019. The increase was attributed to the overload of health services, the lack of adequate Intensive Care Unit (ICU) beds for pregnant women and the delay in care, especially in the most vulnerable regions. In 2022, there was a reduction in the MMR to 57 deaths per 100,000 live births, returning to levels similar to those of the pre-pandemic period. Despite this improvement, Brazil is still far from the WHO target, which predicts an MMR of less than 30 deaths per 100,000 live births by 2030. In addition, large regional disparities persist: in 2023, the North region had the highest rate (75.72), while the South region had the lowest [

11].

Black women, low-income women and women with lower levels of education are more exposed to the risk of maternal death, highlighting the impact of structural racism and inequalities in access to health care. The data show that social and institutional factors contribute to precarious care, especially in obstetric emergency situations [

12], recurring failures in the surveillance and reporting of maternal deaths. The implementation of active surveillance and training of local teams is recommended as an essential strategy for addressing the problem [

13].

Maternal mortality is one of the main indicators of the quality of health systems and equity in access to reproductive health care services. In Brazil, although advances have been made in prenatal coverage and in the monitoring of maternal deaths, the rates remain high and above the parameters recommended by the World Health Organization, revealing persistent regional and socioeconomic inequalities. In this context, this study is justified by its relevance for analyzing trends over two decades, contributing to the monitoring of public policies, strengthening the health system and identifying structural and care failures.

The study is directly aligned with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) of the United Nations 2030 Agenda, in particular SDG 3 – Good Health and Well-Being, which sets the target of reducing the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 deaths per 100,000 live births by 2030. In addition, it is linked to SDG 5 – Gender Equality, by highlighting the impact of gender, race and class inequalities on obstetric outcomes and barriers to access to qualified health services, and SDG 10 – Reduction of Inequalities, by demonstrating the concentration of the highest maternal mortality rates in regions marked by poverty, low education and scarcity of care resources.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Design

This is a retrospective population-based cohort study according to the guidelines of the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) checklist [

14,

15], that analyzed maternal mortality trends in Brazil over a 20-year period. The study design followed the principles of observational epidemiological research, using secondary data obtained from a national health surveillance system. The Brazilian territory, composed of 26 states and the Federal District, is geographically divided into five macro-regions (North, Northeast, Southeast, South, and Central-West), which were used for stratified analysis.

2.2. Population and Period

The study population consisted of all registered cases of maternal death among women aged 10 to 49 years in Brazil, from January 1, 2000, to December 31, 2020. Maternal death was defined according to the WHO criteria as the death of a woman while pregnant or within 42 days of termination of pregnancy, irrespective of the duration and site of the pregnancy, from any cause related to or aggravated by the pregnancy or its management, but not from accidental or incidental causes.

2.3. Data Sources and Variables

Data were extracted from the Sistema de Informações sobre Mortalidade (SIM) of the Brazilian Ministry of Health. The system aggregates data from death certificates collected nationwide and includes information on demographics, causes of death, location of death, investigation status, and clinical circumstances. The main variables analyzed were: Sociodemographic characteristics: age, skin color/ethnicity, marital status, and level of education; Geographic region: North, Northeast, Southeast, South, and Central-West; Cause of death: classified according to the ICD-10 chapters and grouped into direct obstetric, indirect obstetric, and unspecified causes; Period of death: during pregnancy, childbirth or abortion; puerperium (up to 42 days and from 43 days to less than 1 year); outside of pregnancy/puerperium; inconsistent or unknown periods; Place of death: hospital, home, public road, other establishments, or unknown; and Investigation status: investigated with or without a medical record, not investigated, or not applicable.

2.4. Data Management and Statistical Analysis

Data were downloaded in CSV format and organized using Microsoft Excel® and R Studio® (R version 4.3). Descriptive statistics were applied to characterize the population. Absolute and relative frequencies were calculated for all categorical variables. The MMR was computed per 100,000 live births using birth data from Sistema de Informações sobre Nascidos Vivos (SINASC) as the denominator.

To assess differences in the distribution of deaths by categories, Chi-square (χ2) goodness-of-fit tests were applied, comparing observed versus expected frequencies under the null hypothesis of equal distribution among categories. For each category, 95% confidence intervals (95% CI) were calculated for proportions using the Wilson method. Analyses were performed with the support of the R epiR and stats packages.

Data on maternal deaths were organized into thematic categories according to the chapters of the International Classification of Diseases – 10th Revision (ICD-10), type of cause (direct, indirect, or unspecified obstetric), period of death (pregnancy, childbirth, early or late puerperium, among others), place of occurrence (hospital, home, public road, etc.), and investigation status (with or without documentation, not investigated, not applicable).

To visually compare the percentage distribution across the various dimensions analyzed, a comparative line chart was constructed. This graphic representation allows for the simultaneous observation of maternal death profiles by multiple variables, facilitating the identification of patterns and disparities between groups. The chart was developed using the Python programming language with the Matplotlib library. This graphical approach contributed to highlighting the categories with the highest concentration of maternal deaths and allowed for the identification of structural inequalities associated with these outcomes, thus supporting a critical discussion of the findings in light of the scientific literature.

2.5. Ethical Considerations

The study was conducted using publicly available, anonymized secondary data, in accordance with the Brazilian National Health Council Resolution No. 510/2016, which waives the need for Research Ethics Committee approval for studies that do not involve human subjects directly.

3. Results

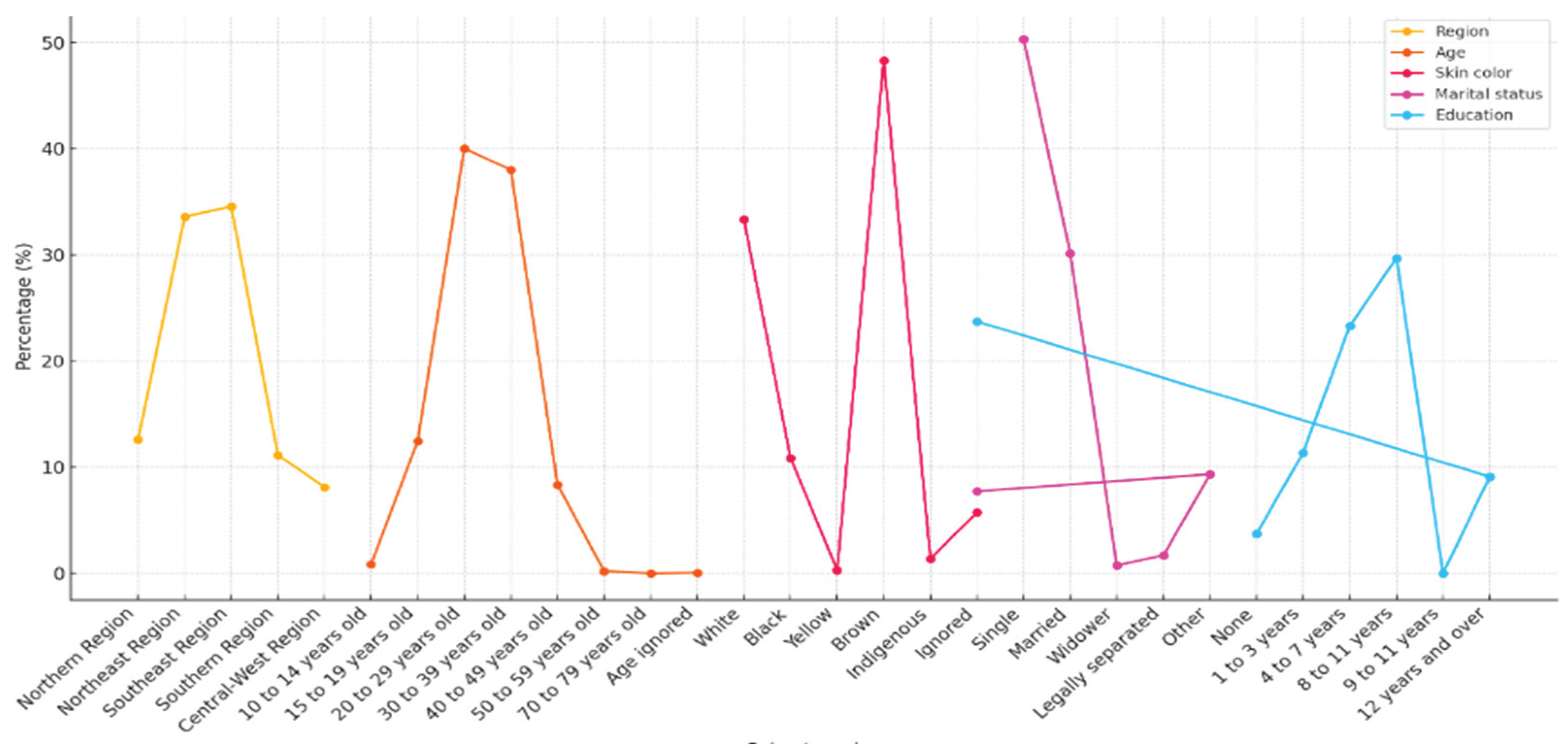

Table 1 shows the distribution of the 40,907 maternal deaths recorded in Brazil between 2000 and 2020, according to different sociodemographic characteristics. It can be observed that the highest proportion of maternal deaths occurred in the Southeast region (34.54%), followed by the Northeast (33.61%) and North (12.58%) regions. The South (11.14%) and Central-West (8.14%) regions had the lowest percentages, which reflects regional disparities in access, quality of obstetric care and death surveillance.

Regarding age groups, it is worth noting that most deaths were concentrated among women aged 20 to 29 (40.04%) and 30 to 39 (38.01%), which correspond to the ages with the highest fertility rates in Brazil. Although less frequent, the number of deaths among adolescents aged 15 to 19 (12.48%) is significant, highlighting the vulnerability of this group. Cases among girls aged 10 to 14 (0.85%) and women over 40 (8.36%) also deserve attention because they represent age extremes with the highest obstetric risk. Regarding skin color, brown women accounted for almost half of the deaths (48.34%), followed by white women (33.36%) and black women (10.87%). This distribution indicates significant racial inequalities, associated with structural factors such as institutional racism and unequal access to health services. Although they represent smaller proportions, deaths among indigenous women (1.38%) and Asian women (0.30%) are also relevant from an equity perspective.

Analysis of marital status shows that single women accounted for more than half of the deaths (50.31%), followed by married women (30.16%). The high percentage of women without a formal partner may indicate greater social vulnerability, reduced family support and difficulties in accessing care. Other marital statuses, such as legally separated (1.70%) and widowed (0.75%), had lower frequencies. Finally, the education level reveals that 29.7% of women who died had between 8 and 11 years of education, followed by those with 4 to 7 years (23.32%) and 1 to 3 years (11.39%). However, a high percentage of records (23.73%) did not contain information on education level. Low education level is associated with a higher risk of complications during pregnancy, less understanding of health guidelines and limited access to obstetric services, constituting an important social determinant of maternal mortality.

Regarding the geographic region, it is observed that the highest proportion of deaths occurred in the Southeast (34.54%) and Northeast (33.61%) regions, which together account for more than two-thirds of maternal deaths. Although the Southeast is the most populous and well-structured region in the country, its high participation may reflect both the size of the population and the greater notification of cases. On the other hand, the significant proportion in the Northeast highlights persistent regional inequalities, historically related to lower access to quality health services.

In terms of age group, women between 20 and 29 years old account for the majority of deaths (40.04%), followed by those between 30 and 39 years old (38.01%). This shows that the greatest risk of maternal mortality occurs precisely in the age group with the highest fertility rate in Brazil. The presence of deaths among adolescents between 10 and 14 years old (0.85%) and 15 and 19 years old (12.48%) is noteworthy, as it reveals the impacts of early pregnancy and its possible complications, associated with social vulnerability and limited access to sexual and reproductive health services.

Regarding skin color, it was found that brown women account for almost half of the deaths (48.34%), followed by white women (33.36%) and black women (10.87%). This pattern reinforces the existence of racial inequalities in Brazil, where black and brown women face greater barriers to accessing adequate care during prenatal care, childbirth and postpartum care. The data also reveal that indigenous women (1.38%) and Asian women (0.30%) are less represented, which may reflect both the smaller population proportion and underreporting.

The analysis of marital status shows that more than half of the women who died were single (50.31%), while married women accounted for 30.16% of deaths. This data may reflect social conditions of greater vulnerability, less family support and difficulties in accessing health services for women without a partner. In addition, there are lower percentages among widows (0.75%) and separated women (1.70%).

Regarding education, it was observed that most women had between 8 and 11 years of education (29.70%) and 4 to 7 years (23.32%), which corresponds to incomplete primary and secondary education. However, a worrying fact is the high percentage of ignored education (23.73%), which limits a more precise analysis. Low education, especially among women with no education (3.75%) or with only 1 to 3 years of education (11.39%), points to the correlation between lower educational level and higher risk of maternal death, reflecting the structural inequalities that affect access to information, services and rights.

Figure 1.

Percentage distribution of maternal deaths by different categories (region, age group, skin color, marital status and education). Source: Prepared by the authors. Brazil, 2025.

Figure 1.

Percentage distribution of maternal deaths by different categories (region, age group, skin color, marital status and education). Source: Prepared by the authors. Brazil, 2025.

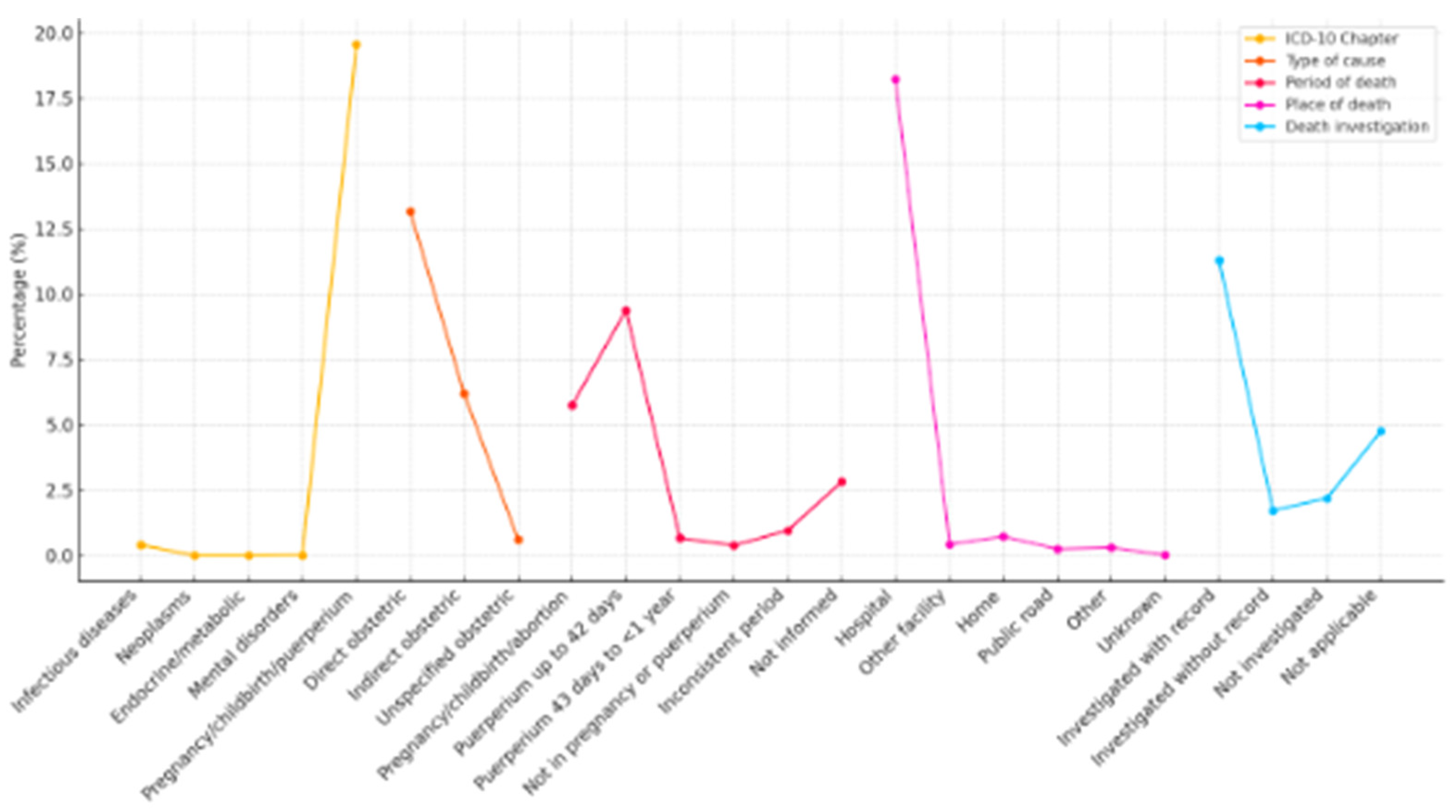

Table 2 shows the distribution of causes of maternal deaths in Brazil, based on ICD-10 chapters, type of obstetric cause, period of death, location where the death occurred and whether the case was investigated. These data allow us to understand the clinical and healthcare profile associated with maternal mortality between 2000 and 2020.

Regarding the ICD-10 chapter, it is observed that the vast majority of deaths (98% of the total) are concentrated in chapter XV, which covers causes directly related to pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium, with 40,016 cases (19.56% of the analyzed base, considering technical proportionality by total causes listed). The other categories present residual proportions: infectious diseases (0.41%), mental and behavioral disorders (0.0176%), neoplasms (0.0049%) and endocrine/metabolic diseases (0.0005%). These results confirm the expected profile of maternal mortality and reinforce the importance of direct obstetric surveillance. Regarding the type of obstetric cause, the predominance of direct causes (13.17%) stands out, such as hypertensive complications, hemorrhages and puerperal infections. Indirect causes, those aggravated by previous clinical conditions, accounted for 6.19% of deaths, while unspecified causes accounted for 0.62%. The predominance of direct causes reinforces the hypothesis of avoidable failures in prenatal care and in the management of obstetric emergencies.

Regarding the period in which the death occurred, it was noted that 9.39% of deaths occurred in the early postpartum period (up to 42 days after delivery), followed by 5.75% during pregnancy, delivery or abortion. The number of deaths between 43 days and less than one year postpartum (0.67%) is small, but relevant from the point of view of continuity of care. In addition, 2.82% of the records did not provide information on the period of death, and 0.96% presented inconsistencies, which may indicate failures in the quality of reporting. Regarding the place of death, most deaths occurred in a hospital setting (18.23%), which, although expected, raises concerns about the quality of care provided in these services. Cases occurring at home (0.73%) and in public spaces (0.25%) may indicate a lack of timely access to emergency care. Notably, 0.43% of deaths occurred in other types of establishments and 0.02% had no recorded information. Finally, the analysis of the status of death investigations shows that 11.30% were investigated with medical records, 1.73% were investigated without documentary records, 2.19% were not investigated and 4.76% were classified as not applicable. Although more than half of the deaths were adequately analyzed, the presence of incomplete or missing investigations compromises the quality of the data and makes it difficult to understand in depth the causes and preventability of deaths.

The graph below shows the percentage distribution of maternal deaths according to five distinct categories: ICD-10 chapter, type of cause, period of death, place of occurrence and investigation status. Comparative analysis allows us to identify the main clinical and operational contexts related to maternal mortality.

In the ICD-10 chapter, it is observed that the majority of maternal deaths were classified under chapter XV – Pregnancy, childbirth and puerperium, representing 19.56% of cases. This number is considerably higher than the other chapters, such as infectious diseases (0.41%), mental disorders (0.0176%), neoplasms (0.0049%) and endocrine and metabolic diseases (0.0005%), which together account for less than 1% of deaths. This reinforces that the majority of maternal deaths are directly attributable to obstetric conditions and not to secondary clinical causes. Regarding the type of cause, direct obstetric causes were responsible for 13.17% of deaths, while indirect causes accounted for 6.19%, and unspecified causes accounted for 0.62%. Direct causes, associated with specific complications of pregnancy and childbirth (such as hemorrhages, infections and eclampsia), continue to predominate, although indirect causes, which include pre-existing diseases aggravated by pregnancy, also have a considerable impact.

The distribution by period of death shows that most deaths occurred in the puerperium up to 42 days after delivery, with 9.39%, followed by the period of pregnancy, delivery or abortion, with 5.75%. A smaller number of deaths occurred in the late puerperium (43 days to less than one year), with 0.67%, while 0.39% occurred outside the pregnancy-puerperal cycle. There are also 0.96% classified as inconsistent periods and 2.82% with an unreported period. These data indicate that the risk of death persists after immediate delivery, which reinforces the importance of postnatal monitoring. Regarding the place of death, the hospital environment was the most frequent scenario, accounting for 18.23% of deaths, highlighting both the central role of hospitals in treating complications and the possibility that many deaths occurred despite institutional care. Deaths at home (0.73%), other establishments (0.43%), public roads (0.25%) and unspecified locations (0.31%) were significantly lower, although still relevant to reflect situations of late access or lack of care.

Finally, regarding the investigation of deaths, 11.30% were investigated with records, while 1.73% were investigated without documentary records. Even so, 2.19% of maternal deaths were not investigated, and in 4.76% of cases the investigation was considered not applicable. This suggests the existence of gaps in the epidemiological surveillance of maternal mortality, with potential underreporting of essential information for the formulation of public policies.

Figure 2.

Percentage distribution of maternal deaths by ICD-10 chapter, type of cause, period of death, place of occurrence and investigation status. Source: Prepared by the authors. Brazil, 2025.

Figure 2.

Percentage distribution of maternal deaths by ICD-10 chapter, type of cause, period of death, place of occurrence and investigation status. Source: Prepared by the authors. Brazil, 2025.

4. Discussion

The findings of this study demonstrate the persistence of a high number of maternal deaths in Brazil over two decades, with patterns marked by regional, social and healthcare inequalities. The analysis revealed that most deaths occurred in young women living in the Southeast and Northeast regions, with a predominance of direct obstetric causes and occurrence in hospital settings, which reinforces the preventable nature of most of these events. These results reiterate the importance of strengthening obstetric care at all levels of care, in addition to the need to improve maternal health surveillance and address the structural inequities that affect reproductive outcomes in the country.

The results of this study reveal a persistent panorama of inequalities in maternal mortality in Brazil, with emphasis on the high proportion of deaths among young, brown women, with low levels of education, and living in the Northeast and Southeast regions. This distribution reflects the structural vulnerability that affects women of reproductive age in the country. Recent studies corroborate this finding, showing that factors such as race, education, and geographic location are strongly associated with the risk of maternal death. According to Silva et al. (2024), black and brown women have a 2.5 times greater risk of dying from maternal causes compared to white women, and this risk is increased in regions with lower coverage and quality of obstetric services [

16].

Maternal mortality remains a serious global public health problem, although there are profound inequalities between countries. The preventable deaths of millions of women each decade are not only due to biomedical complications of pregnancy, childbirth and the postpartum period, but are also tangible manifestations of the prevailing determinants of maternal health and persistent inequalities in global health and socioeconomic development [

17]. Brazil, with an estimated MMR of 107.53/100,000 in 2021, is above the target set by the SDGs, which highlights the need for more effective and equitable policies [

18].

Compared to other middle-income countries, Brazilian data are intermediate. A recent study found that the incidence of hypertensive disorders during pregnancy, the leading direct cause of maternal death, is lower in Brazil than in Russia and India, but still higher than the levels observed in China and South Africa [

19,

20]. This reveals the positive impact of some Brazilian public policies on maternal health, such as the Rede Cegonha Strategy, but also the limitations in the coverage and resolution of obstetric care in vulnerable regions [

21].

The predominance of direct causes of maternal mortality, especially those related to chapter XV of ICD-10, was also evident in this study. Causes such as postpartum hemorrhage, hypertensive disorders, and puerperal infections are still among the main lethal events, despite being widely recognized as preventable. Albarqi et al. (2024) demonstrated that the lack of early diagnosis and timely interventions during prenatal care and childbirth remains a determining factor in negative outcomes [

22]. The high occurrence of these deaths in hospital settings, as evidenced in our analysis, suggests serious care failures within the health system, which points to the need to strengthen the training of obstetric care teams and the organization of care networks [

23].

In addition to direct causes such as hemorrhages, infections, and hypertensive syndromes, the proportion of deaths associated with indirect causes, such as cardiovascular diseases and mental disorders, is increasing, especially in the late postpartum period [

24,

25]. In the United Kingdom, for example, the main causes of maternal death in 2022 were suicide and heart problems. This suggests the need to expand the monitoring of women in the postpartum period and integrate mental health actions and primary care with maternal health [

26].

Maternal mortality in the immediate postpartum period (up to 42 days after delivery) accounted for almost 10% of all deaths analyzed, confirming the literature that indicates this period as critical for the occurrence of serious complications. A study conducted by Batulan et al. (2024) showed that women who do not have access to continuous monitoring after hospital discharge are more likely to develop untreated complications, such as infections, thrombosis, and mental disorders, which increases the risk of preventable death [

27].

Another relevant point concerns the low completeness of maternal death investigations. In our study, more than 13% of records were not investigated or were investigated incompletely, which compromises the quality of surveillance and makes it difficult to identify systemic failures. According to Oliveira et al. (2023), the absence of active maternal mortality committees in some Brazilian regions hinders the development of corrective actions and prevents institutional learning from adverse events [

28]. Investing in more robust reporting systems and teams dedicated to the critical analysis of deaths is essential to break this cycle of invisibility and neglect [

29].

Although this study focused on officially recorded maternal deaths among cisgender women, it is essential to highlight the need to incorporate a broader and more inclusive perspective on who can become pregnant and face obstetric risks. Transgender men and non-binary people with reproductive capacity also experience pregnancy and childbirth, and are equally at risk of obstetric complications and maternal mortality.

A study conducted with primary care professionals revealed stigmatizing perceptions and misinformation about the reproductive rights of trans men, indicating the urgent need for ethical, technical and political training of health teams. The effective inclusion of these populations in prenatal care and surveillance strategies is essential not only to reduce clinical risks, but also to ensure reproductive justice, as recommended by the SDGs. Ignoring these experiences can contribute to the underreporting of deaths and the perpetuation of an exclusionary health system, which compromises gender equity and the right to comprehensive health [

30].

This study presents some limitations inherent to the use of secondary data from official information systems. The first concerns the quality and completeness of maternal mortality records in the SIM, especially in regions with lower coverage and poor infrastructure, which can lead to underreporting or incorrect classification of causes of death. Another limitation refers to the classification of direct, indirect or unspecified obstetric causes, which depends on the accuracy of the completion of death certificates and the coding of underlying causes according to ICD-10. The lack of detailed clinical information prevents the assessment of the preventability of cases or the quality of care provided. Furthermore, because this is an ecological and retrospective study, it is not possible to establish causal relationships between the factors analyzed and the observed outcomes.

The study offers important contributions to the field of maternal health by conducting a comprehensive analysis of maternal mortality in Brazil over two decades, based on a large volume of population data. The research allows us to identify temporal trends, regional patterns and social inequalities associated with maternal deaths, providing support for the planning of more equitable and territorially oriented public policies. The results also contribute to the monitoring of the SDGs, especially SDG 3 (Good Health and Well-Being) and SDG 10 (Reduced Inequalities), in addition to promoting reflections on addressing racism in health services.

5. Conclusions

This study revealed a worrying panorama of maternal mortality in Brazil over the last two decades, highlighting the persistence of patterns marked by regional, social and racial inequalities. The predominance of deaths among young, brown women, with low levels of education and living in historically vulnerable regions points to the decisive influence of social determinants of health on maternal outcomes. In addition, the concentration of deaths due to direct obstetric causes and the fact that most of them occur in hospital settings reinforce the preventable nature of most of these deaths, revealing flaws in the prenatal, childbirth and postpartum care systems.

The study findings indicate the urgent need to improve obstetric care, with an emphasis on primary health care, expanding access to timely care, providing ongoing training to health teams, and strengthening regulatory and counter-referral networks. Investments in active surveillance, improving information systems, and encouraging systematic investigation of deaths are also essential to identify care failures and guide prevention actions. Addressing maternal mortality in Brazil requires intersectoral and structural approaches that go beyond the health field, promoting social equity, reproductive justice, and guaranteeing women’s rights. Overcoming the inequities that sustain this scenario is a fundamental condition for the country to advance in meeting the targets of the SDGs and ensuring safe, dignified, and humane motherhood for all.

Author Contributions

For research articles with several authors, a short paragraph specifying their individual contributions must be provided. The following statements should be used “Conceptualization, Santos G.G, Vidotti G.A.G, Gil B.M.B and Pedraza L.L.; methodology, Santos G.G, Oliveira Neto J.G and Nascimento W.S.M.; software, Santos G.G, Silva A.L.C and Nascimento ES.; validation, Santos G.G, Vidotti G.A.G, Gil B.M.B and Pedraza L.L.; formal analysis, Santos G.G, Oliveira Neto J.G, Vidotti G.A.G, Gil B.M.B and Pedraza L.L.; investigation, Santos G.G, Vidotti G.A.G, Gil B.M.B and Pedraza L.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Santos G.G, Bonetti T.C.S, Ichikawa C.R.F, Lima C.F, Dionizio L.A, Maia J.S, Zihlmann K.F, Oliveira Neto J.G, Nascimento W.S.M, Cardoso A.M.R, Carvalho J.M.N, Santa Rosa P.L.F, Mouta R.J.O, Reis C.H.R, Aguiar C.A, Santos D.S.; writing—review and editing, Santos G.G, Vidotti G.A.G, Bonetti T.C.S, Ichikawa C.R.F, Lima C.F, Dionizio L.A, Maia J.S, Zihlmann K.F, Oliveira Neto J.G, Nascimento W.S.M, Cardoso A.M.R, Carvalho J.M.N, Santa Rosa P.L.F, Mouta R.J.O, Reis C.H.R, Aguiar C.A, Santos D.S, Silva B.P, Silva A.L.C, Nascimento E.S, Gil B.M.B, Pedraza L.L.; visualization, Santos G.G, Oliveira Neto J.G, Silva B.P, Vidotti G.A.G, Gil B.M.B and Pedraza L.L.; supervision, Santos G.G, Vidotti G.A.G, Gil B.M.B and Pedraza L.L.; project administration, Santos G.G, Vidotti G.A.G, Gil B.M.B and Pedraza L.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.”

Funding

This research received no external funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Additional questions can be directed to the corresponding author(s)

Public Involvement Statement

No public involvement in any aspect of this research

Guidelines and Standards Statement

This manuscript was drafted against the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) (Vandenbroucke et al., 2007; von Elm et al., 2008)

Use of Artificial Intelligence

Not applicable

Acknowledgments

Not applicable

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest

Abbreviations

Classification of Diseases – 10th Revision (ICD-10)

Intensive Care Unit (ICU)

Maternal mortality ratio (MMR)

Sistema de Informações sobre Mortalidade (SIM)

Sistema de Informações sobre Nascidos Vivos (SINASC)

Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE)

Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)

World Health Organization (WHO)

References

- Brasil. Ministério da Saúde. Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde. Departamento de Ações Programáticas Estratégicas. Manual dos comitês de mortalidade materna / Ministério da Saúde, Secretaria de Atenção à Saúde, Departamento de Ações Programáticas Estratégicas. – 3. ed. – Brasília: Editora do Ministério da Saúde, 2007. 104 p. https://bvsms.saude.gov.br/bvs/publicacoes/comites_mortalidade_materna_3ed.pdf.

- Say L, Souza JP, Pattinson RC; WHO working group on Maternal Mortality and Morbidity classifications. Maternal near miss--towards a standard tool for monitoring quality of maternal health care. Best Pract Res Clin Obstet Gynaecol. 2009 Jun;23(3):287-96. [CrossRef]

- Leal M do C, Esteves-Pereira AP, Bittencourt SA, Domingues RMSM, Theme Filha MM, Leite TH, et al. Protocolo do Nascer no Brasil II: Pesquisa Nacional sobre Aborto, Parto e Nascimento. Cad Saúde Pública [Internet]. 2024;40(4):e00036223. [CrossRef]

- Leal M do C, Szwarcwald CL, Almeida PVB, Aquino EML, Barreto ML, Barros F, et al. Saúde reprodutiva, materna, neonatal e infantil nos 30 anos do Sistema Único de Saúde (SUS). Ciênc saúde coletiva [Internet]. 2018Jun;23(6):1915–28. [CrossRef]

- Oliveira IVG, Maranhão TA, Frota MMC da, Araujo TKA de, Torres S da RF, Rocha MIF, et al. Mortalidade materna no Brasil: análise de tendências temporais e agrupamentos espaciais. Ciênc saúde coletiva [Internet]. 2024;29(10):e05012023. [CrossRef]

- Borgonove KCA, Lansky S, Soares VMN, Matozinhos FP, Martins EF, Silva RAR, et al. Time series analysis: trend in late maternal mortality in Brazil, 2010-2019. Cad Saúde Pública [Internet]. 2024;40(7):e00168223. [CrossRef]

- Gama SGN da, Bittencourt SA, Theme Filha MM, Takemoto MLS, Lansky S, Frias PG de, et al. Mortalidade materna: protocolo de um estudo integrado à pesquisa Nascer no Brasil II. Cad Saude Publica. 2024;40(4):e00107723. [CrossRef]

- Tintori JA, Mendes LMC, Monteiro JC dos S, Gomes-Sponholz F. Epidemiologia da morte materna e o desafio da qualificação da assistência. Acta Paul Enferm. 2022;35:eAPE00251. [CrossRef]

- Ruas CAM, Quadros JFC, Rocha JFD, Rocha FC, Andrade Neto GR de, Piris ÁP, et al. Profile and spatial distribution on maternal mortality. Rev Bras Saude Mater Infant [Internet]. 2020Apr;20(2):385–96. [CrossRef]

- Leal M do C, Gama SGN da, Pereira APE, Pacheco VE, Carmo CN do, Santos RV. A cor da dor: iniquidades raciais na atenção pré-natal e ao parto no Brasil. Cad Saúde Pública [Internet]. 2017;33:e00078816. [CrossRef]

- Fapespa. Fundação Amazônia de Amparo a Estudos e Pesquisas. Taxa de mortalidade materna (2019–2023). Belém: Fapespa; 2024. https://www.fapespa.pa.gov.br/wp-content/uploads/2024/03/Boletim-da-Saude-Paraense-2024-VERSAO-PUBLICACAO.pdf.

- Ferreira MES, Coutinho RZ, Queiroz BL. Morbimortalidade materna no Brasil e a urgência de um sistema nacional de vigilância do near miss materno. Cad Saude Publica. 2023;39(8):e00013923. [CrossRef]

- Feitosa-Assis AI, Santana VS. Occupation and maternal mortality in Brazil. Rev Saude Publica. 2020 Jun 26;54:64. [CrossRef]

- Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gøtzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, Poole C, Schlesselman JJ, Egger M; STROBE Initiative. Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE): explanation and elaboration. Epidemiology. 2007 Nov;18(6):805-35. [CrossRef]

- von Elm E, Altman DG, Egger M, Pocock SJ, Gøtzsche PC, Vandenbroucke JP; STROBE Initiative. The Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) statement: guidelines for reporting observational studies. J Clin Epidemiol. 2008 Apr;61(4):344-9. [CrossRef]

- Silva, BG, Sousa, GML, Queres, RL, Lourenço, LP, Martins, LPOM, Fonseca, SC, Boschi-Pinto, C., Kawa, H. Tendência da Razão de Mortalidade Materna segundo raça/cor no estado do Rio de Janeiro, 2008 a 2021. Cien Saude Coletiva. http://cienciaesaudecoletiva.com.br/artigos/tendencia-da-razao-de-mortalidade-materna-segundo-racacor-no-estado-do-rio-de-janeiro-2008-a-2021/19606.

- Silva AD, Guida JPS, Santos D de S, Santiago SM, Surita FG. Racial disparities and maternal mortality in Brazil: findings from a national database. Rev Saúde Pública [Internet]. 2024;58:25. [CrossRef]

- Souza JP, Day LT, Rezende-Gomes AC, Zhang J, Mori R, Baguiya A, Jayaratne K, Osoti A, Vogel JP, Campbell O, Mugerwa KY, Lumbiganon P, Tunçalp Ö, Cresswell J, Say L, Moran AC, Oladapo OT. A global analysis of the determinants of maternal health and transitions in maternal mortality. Lancet Glob Health. 2024 Feb;12(2):e306-e316. [CrossRef]

- Martins ALJ, Miranda WD, Silveira F, Paes-Sousa R. A Agenda 2030 e os Objetivos de Desenvolvimento Sustentável (ODS) como estratégia para equidade em saúde e territórios sustentáveis e saudáveis. Saúde debate [Internet]. 2024Aug;48(spe1):e8828. [CrossRef]

- Wang X, Cheng F, Fu Q, Cheng P, Zuo J, Wu Y. Time trends in maternal hypertensive disorder incidence in Brazil, Russian Federation, India, China, and South Africa (BRICS): an age-period-cohort analysis for the GBD 2021. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2024 Nov 8;24(1):731. [CrossRef]

- Dorcély DF, Surita FG, Costa ML, de Siqueira Guida JP. Maternal deaths due to hypertensive disorders of pregnancy in Brazil from 2012 until 2023: a cross-sectional populational-based study. Hypertens Pregnancy. 2025 Dec;44(1):2492094. [CrossRef]

- Silva LBRA de A, Angulo-Tuesta A, Massari MTR, Augusto LCR, Gonçalves LLM, Silva CKRT da, et al. Avaliação da Rede Cegonha: devolutiva dos resultados para as maternidades no Brasil. Ciênc saúde coletiva [Internet]. 2021Mar;26(3):931–40. [CrossRef]

- Albarqi MN. The Impact of Prenatal Care on the Prevention of Neonatal Outcomes: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Global Health Interventions. Healthcare (Basel). 2025 May 6;13(9):1076. [CrossRef]

- Lima Júnior AJ, Zanetti ACB, Dias BM, Bernandes A, Gastaldi FM, Gabriel CS. Occurrence and preventability of adverse events in hospitals: a retrospective study. Rev Bras Enferm. 2023;76(3):e20220025. [CrossRef]

- Cresswell, Jenny A et al. Global and regional causes of maternal deaths 2009–20: a WHO systematic analysis. The Lancet Global Health, 2025;e626- e634. [CrossRef]

- Silva JM de P da, Kale PL, Fonseca SC, Nantes T, Alt NN. Factors associated with severe maternal, fetuses and neonates’ outcomes in a university hospital in Rio de Janeiro State. Rev Bras Saude Mater Infant [Internet]. 2023;23:e20220135. [CrossRef]

- Simmons E, Gong J, Daskalopoulou Z, Quigley MA, Alderdice F, Harrison S, Fellmeth G. Global contribution of suicide to maternal mortality: a systematic review protocol. BMJ Open. 2024 Sep 16;14(9):e087669. [CrossRef]

- Batulan Z, Bhimla A, Higginbotham EJ, editors. Advancing Research on Chronic Conditions in Women. Washington (DC): National Academies Press (US); 2024 Sep 25. 6, Chronic Conditions That Predominantly Impact or Affect Women Differently. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK607719/.

- Oliveira G, Jesus R, Dias P, Alvares L, Nepomuceno A, Sakai L, et al. Epidemiological profile of Covid-19 cases and deaths in a reference hospital in the state of Goiás, Brazil. Journal of Tropical Pathology. 2023. [CrossRef]

- Souza JP. Mortalidade materna no Brasil: a necessidade de fortalecer os sistemas de saúde. Rev Bras Ginecol Obstet [Internet]. 2011Oct;33(10):273–9. [CrossRef]

- Cardoso JC, Santos SD, Santos JGS, Pereira DMR, Almeida LCG, Souza ZCSN, Oliveira JF, et al. Stigma in doctors’ and nurses’ perception regarding prenatal care for transgender men. Acta Paul Enferm 2024;37:eAPE00573. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).