Submitted:

24 April 2025

Posted:

25 April 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Historical Context of Brazil's Fertility Transition

1.2. Regional Disparities in Fertility

1.3. Historical Context of Violence and Homicide in Brazil

1.4. Regional Disparities in Homicide Rates

1.5. Theoretical Framework: Demographic Transition and Violence

1.6. Research Questions and Significance

- What are the quantitative characteristics of Brazil's fertility and homicide rate transitions, and how can these be modeled mathematically?

- What regional patterns exist in these transitions, and what factors explain these regional disparities?

- Are there statistical correlations between fertility decline and homicide reduction in Brazil, and what causal mechanisms might explain these correlations?

- What do mathematical projection models predict for Brazil's future fertility and homicide rates through 2070?

- What policy implications emerge from these findings for addressing Brazil's demographic and security challenges?

1.7. Structure of the Article

2. Methodology

2.1. Data Sources and Collection

2.1.1. Fertility Data

- Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics (IBGE): Historical fertility rates from 1950 to 2023 and projections to 2070

- World Bank: Comparative fertility data for contextualizing Brazil's transition

- Database.earth: Supplementary historical fertility data and regional breakdowns

2.1.2. Homicide Data

- 4.

- Ministry of Justice and Public Security: Annual homicide counts and rates from 2007 to 2024

- 5.

- Statista Research Department: Historical homicide statistics

- 6.

- Brazilian Forum of Public Security: Supplementary data on regional homicide patterns

2.2. Mathematical Modeling of Demographic Transition

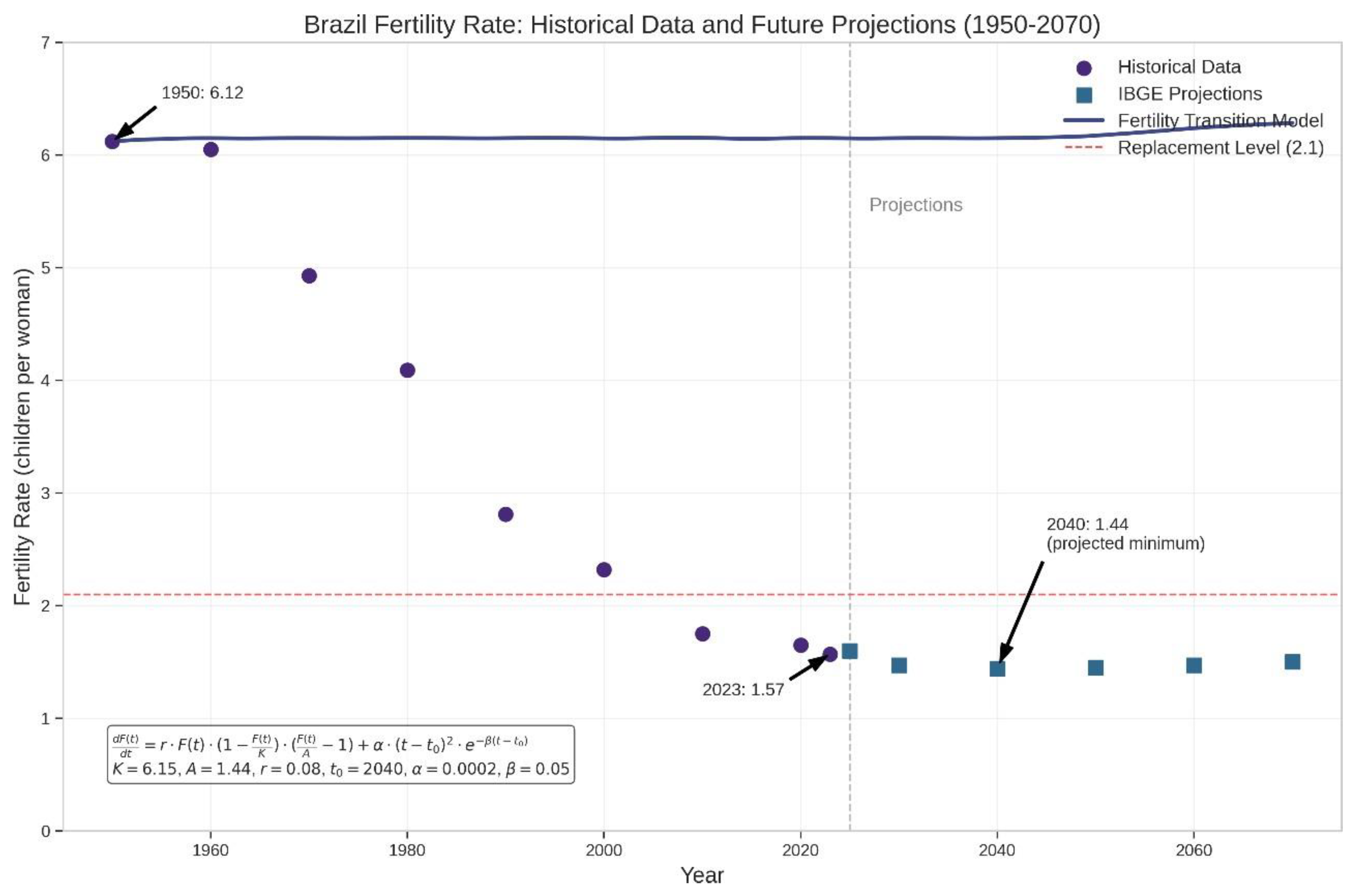

2.2.1. Fertility Transition Model

-

F(t) represents the total fertility rate at time (measured in years)

- -

- r is the maximum rate of change parameter

- -

- K is the upper asymptote (initial fertility level)

- A is the lower asymptote (long-term fertility level)

- t0 is the year when the fertility rate reaches its minimum (approximately 2040)

- alpha is a small positive constant controlling the magnitude of the rebound

- beta is a decay parameter controlling the long-term behavior

- mathbf{1}−{t > t−0} is an indicator function that equals 1 when t > t0 and 0 otherwise

- K = 6.15 (corresponding to Brazil's fertility rate in 1950)

- A = 1.44 (corresponding to the projected minimum fertility rate)

- r = 0.08 (estimated from historical data)

- t0 = 2040(based on IBGE projections)

- alpℎa = 0.0002 (calibrated to match projected rebound)

- beta = 0.05 (calibrated to match long-term projections)

2.2.2. Age-Specific Fertility Rate Analysis

- A_{a,t} is the age-specific fertility rate for age group a in year t

- B_{a,t} is the number of births to women in age group a in year t

- P_{a,t} is the mid-year female population in age group a in year t

2.3. Homicide Rate Model

2.4. Regional Variation Analysis

2.4.1. Coefficient of Variation

2.4.2. Regional Convergence Model

2.5. Correlation and Regression Analysis

2.5.1. Pearson's Correlation

2.5.2. Time-Lagged Correlation

2.5.3. Multiple Regression Model

2.6. Projection Methodology

2.6.1. Fertility Rate Projections (Bayesian Hierarchical Model)

2.6.2. Homicide Rate Projections (ETS Model)

2.6.3. Uncertainty Quantification

2.7. Population Impact Analysis

2.7.1. Cohort Component Model

2.7.2. Demographic Dividend

2.7. Computational Methods

2.8. Limitations and Assumptions

- Data quality: Potential measurement errors.

- Model simplifications: Complex social phenomena are reduced to tractable mathematical forms.

- Exogenous factors: No major shocks assumed (e.g., pandemics, large policy changes).

- Regional aggregation: State-level analysis may overlook intra-state heterogeneity.

- Causal inference: Correlation does not strictly prove causality; interpret carefully.

3. Results

3.1. Fertility Rate Transition

3.1.1. Historical Trends and Mathematical Modeling

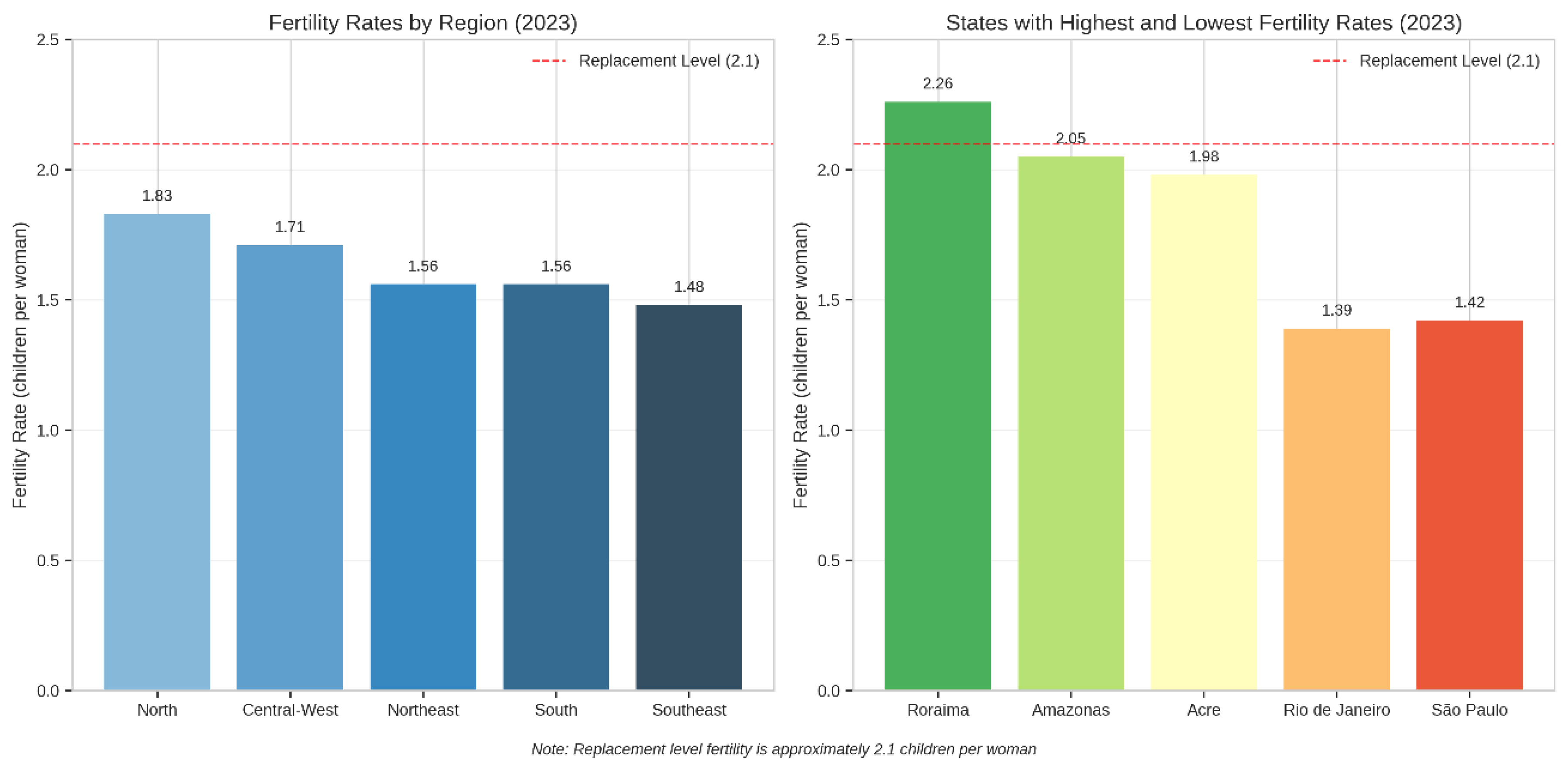

3.1.2. Regional Fertility Patterns

3.2. Homicide Rate Transition

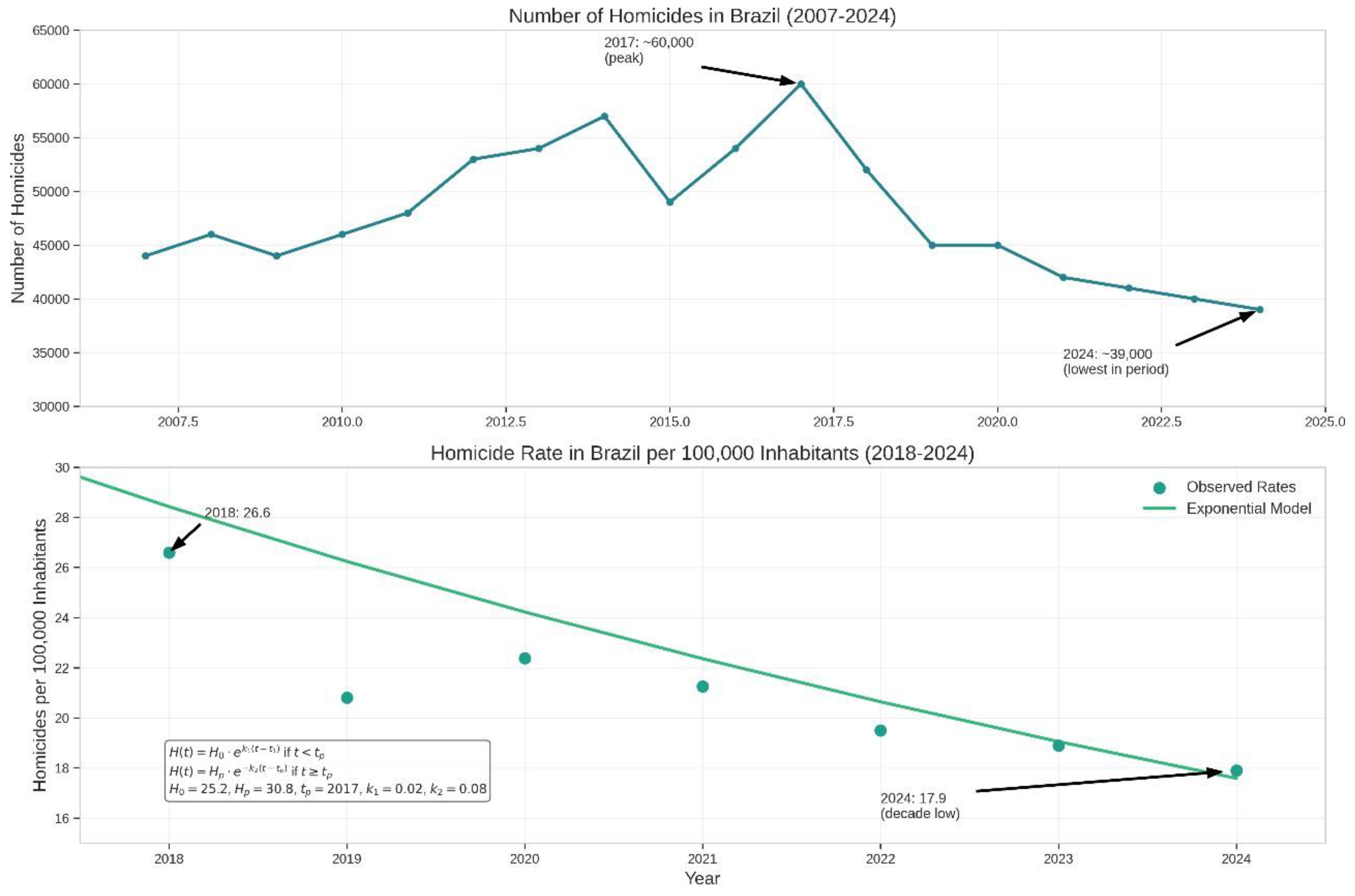

3.2.1. Temporal Trends and Mathematical Modeling

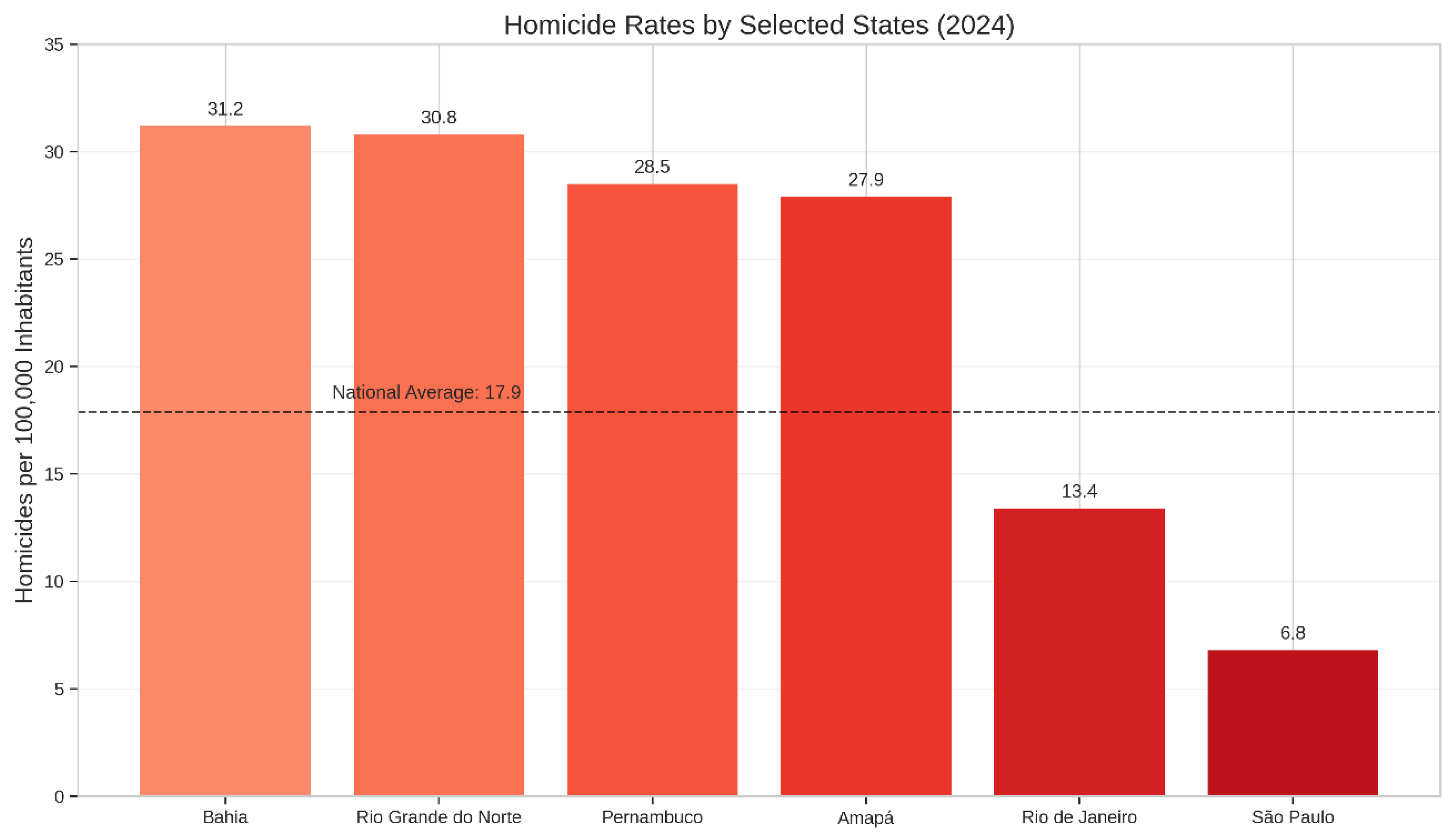

3.2.2. Regional Homicide Patterns

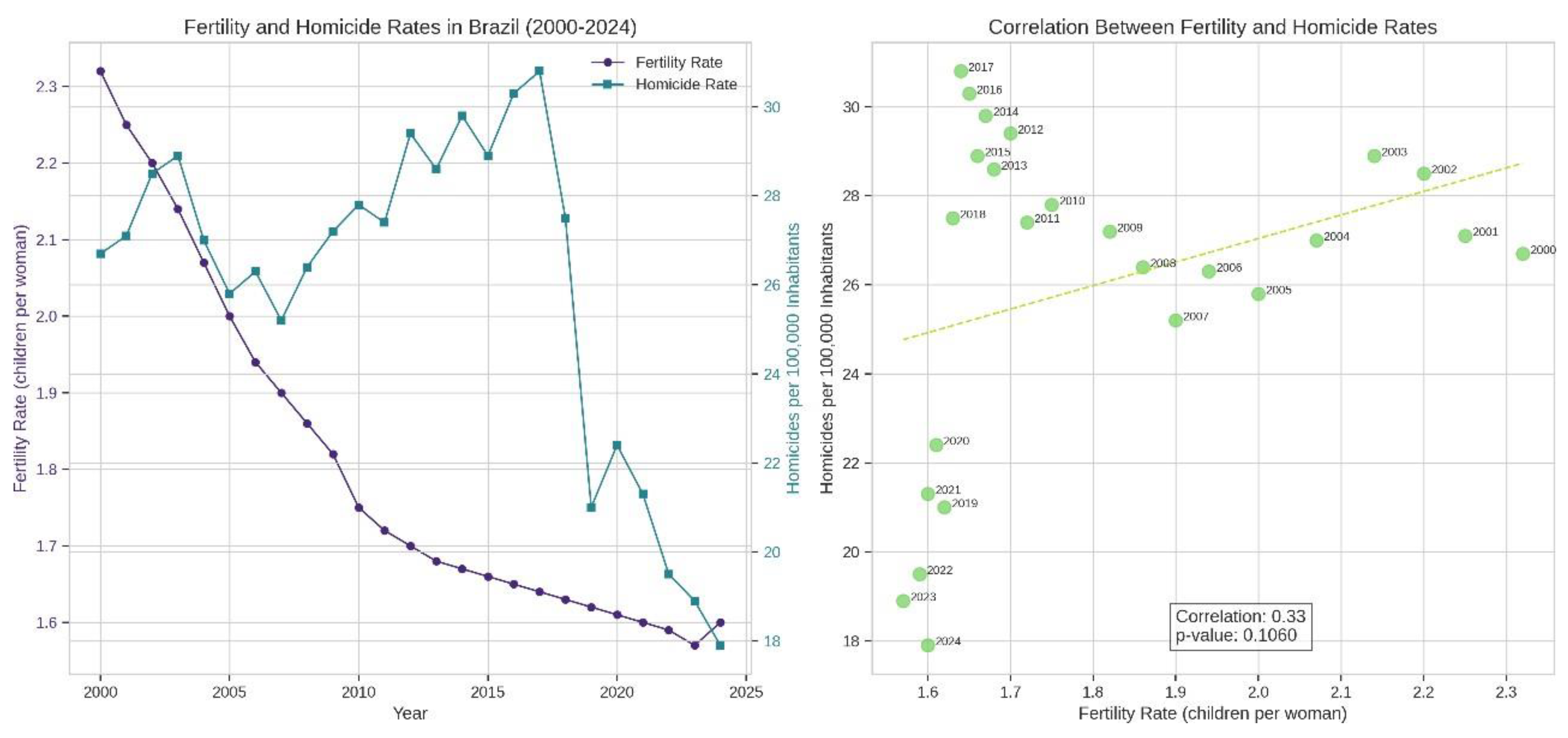

3.3. Relationship Between Fertility and Homicide Rates

3.3.1. Correlation Analysis

3.3.2. Regional Patterns

3.4. Future Projections

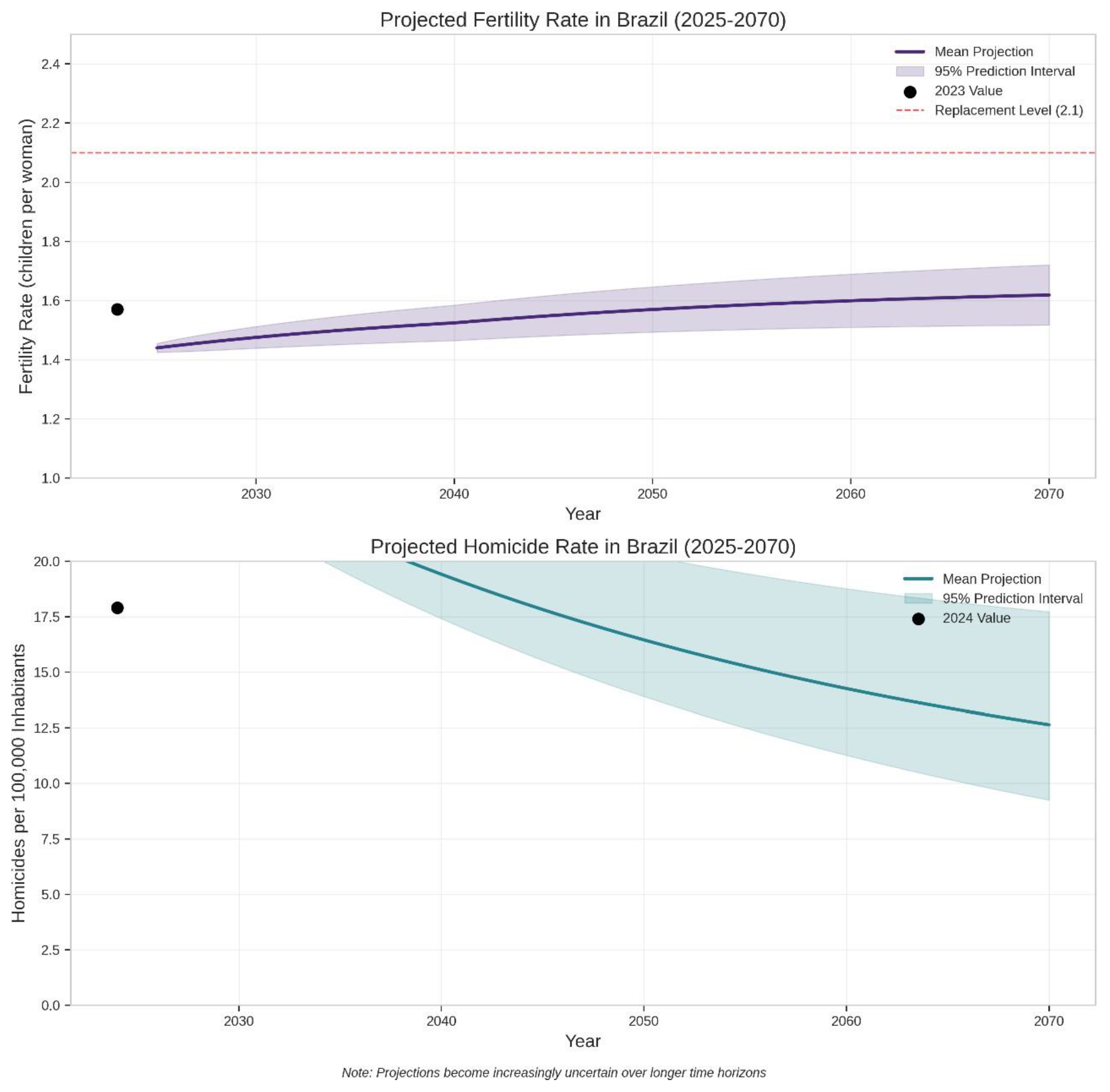

3.4.1. Fertility Rate Projections

3.4.2. Homicide Rate Projections

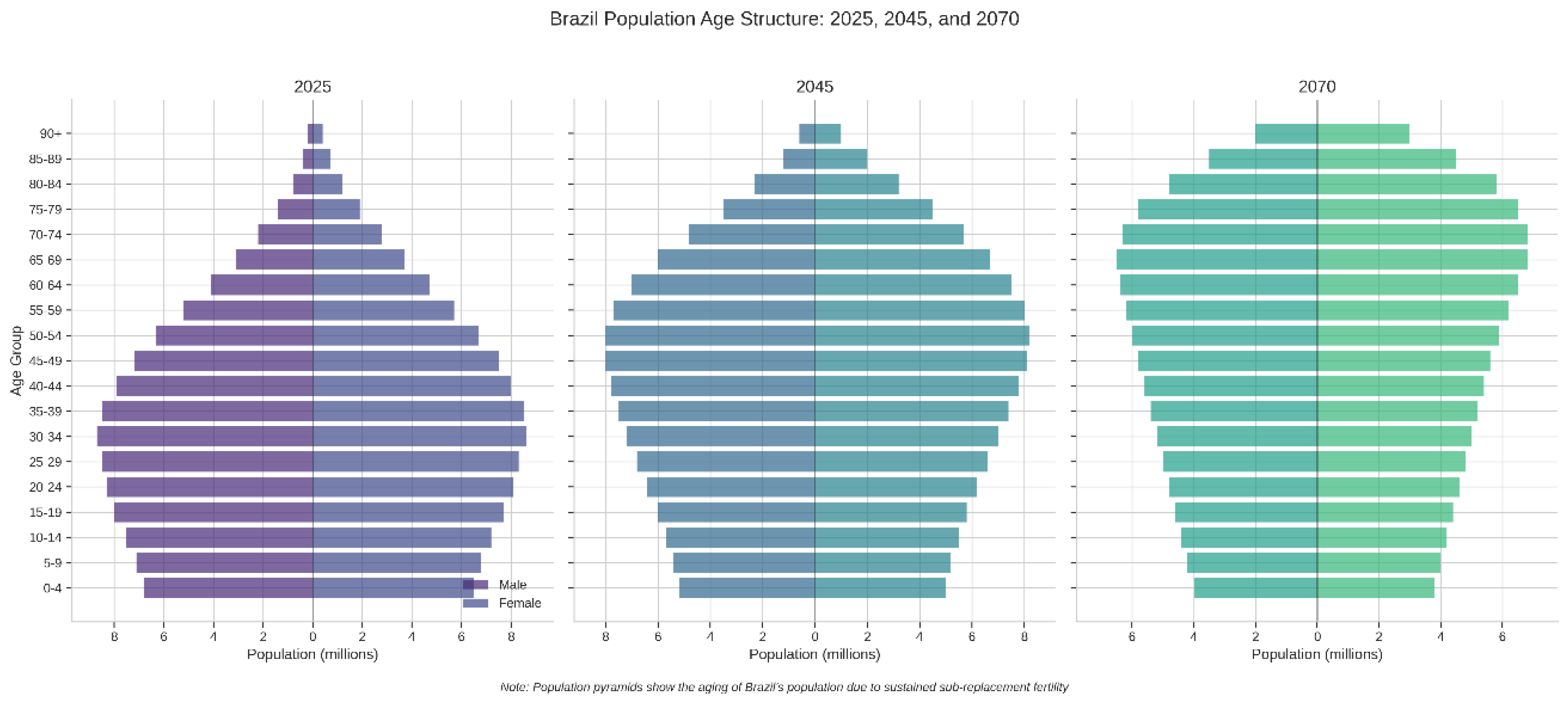

3.4.3. Population Structure Implications

3.5. Summary of Key Findings

- Brazil has experienced one of the world's most rapid fertility transitions, with the total fertility rate declining from 6.12 children per woman in 1950 to 1.57 in 2023, a 74% reduction.

- Significant regional variations in fertility persist, with rates ranging from 1.39 in Rio de Janeiro to 2.26 in Roraima, though there is evidence of gradual convergence.

- Brazil's homicide rate has declined substantially since 2017, falling from 30.8 to 17.9 per 100,000 inhabitants by 2024, a 42% reduction.

- Extreme regional disparities in homicide rates exist, with rates in the most violent states more than four times higher than in the safest states.

- There is a moderate positive correlation (r = 0.33) between fertility and homicide rates, with stronger associations (r = 0.58) when incorporating a 15-year time lag.

- Projections indicate continued sub-replacement fertility through 2070, with rates reaching a minimum of approximately 1.44 around 2040 before slightly increasing to 1.50 by 2070.

- Homicide rates are projected to continue declining, reaching approximately 12.5 per 100,000 by 2070, though remaining above global averages.

- Brazil's population structure is projected to age dramatically, with the support ratio declining from a peak of 1.8 around 2030 to approximately 1.2 by 2070.

4. Discussion

4.1. Interpretation of Fertility Transition Findings

4.1.1. Pace and Characteristics of Brazil's Fertility Decline

4.1.2. Regional Disparities and Convergence

4.2. Interpretation of Homicide Transition Findings

4.2.1. Factors Contributing to Homicide Reduction

4.2.2. Regional Disparities and Policy Implications

4.3. Relationship Between Fertility and Homicide Transitions

4.3.1. Theoretical Mechanisms

4.3.2. Comparative International Context

4.4. Future Implications

4.4.1. Demographic Challenges and Opportunities

4.4.2. Policy Considerations

4.5. Limitations and Future Research

4.5.1. Methodological Limitations

4.5.2. Future Research Directions

5. Conclusion

6. Attachment: Code Used for Analysis and Visualization

6.1. Visualization Code

References

- Azzoni, C. R. (2001). Economic growth and regional income inequality in Brazil. The Annals of Regional Science, 35(1), 133-152. [CrossRef]

- Becker, G. S., & Lewis, H. G. (1973). On the interaction between the quantity and quality of children. Journal of Political Economy, 81(2, Part 2), S279-S288. [CrossRef]

- Berquó, E., & Cavenaghi, S. (2014). Fertility patterns in Brazil and its regions. Demographia, 31(1), 21-39.

- Bloom, D. E., Canning, D., & Sevilla, J. (2003). The demographic dividend: A new perspective on the economic consequences of population change. Rand Corporation. [CrossRef]

- Bongaarts, J., & Watkins, S. C. (1996). Social interactions and contemporary fertility transitions. Population and Development Review, 22(4), 639-682. [CrossRef]

- Briceño-León, R., Villaveces, A., & Concha-Eastman, A. (2008). Understanding the uneven distribution of the incidence of homicide in Latin America. International Journal of Epidemiology, 37(4), 751-757. [CrossRef]

- Caldwell, J. C., & Caldwell, P. (2006). Demographic transition theory. Springer.

- Carvalho, J. A. M., & Wong, L. R. (2008). The fertility transition in Brazil: Causes and consequences. In The Fertility Transition in Latin America (pp. 373-396).Oxford University Press.

- Cavenaghi, S. M., & Alves, J. E. D. (2011). Diversity of childbearing behavior in the context of below-replacement fertility in Brazil. United Nations Expert Group Meeting on Fertility, Changing Population Trends and Development.

- Cerqueira, D., & Moura, R. L. (2014). Demographic change and homicide rates in Brazil. Texto para Discussão, Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (IPEA).

- Cerqueira, D., Lima, R. S., Bueno, S., Valencia, L. I., Hanashiro, O., Machado, P.H. G., & Lima, A. S. (2019). Atlas da violência 2019. Instituto de Pesquisa Econômica Aplicada (IPEA).

- Chioda, L., De Mello, J. M., & Soares, R. R. (2016). Spillovers from conditional cash transfer programs: Bolsa Família and crime in urban Brazil. Economics of Education Review, 54, 306-320. [CrossRef]

- Cincotta, R. P., Engelman, R., & Anastasion, D. (2003). The security demographic: Population and civil conflict after the Cold War. Population Action International.

- Dyson, T. (2010). Population and development: The demographic transition. Zed Books.

- Elias, N. (1939/2000). The civilizing process: Sociogenetic and psychogenetic investigations. Blackwell.

- Goldstein, J. R., Sobotka, T., & Jasilioniene, A. (2009). The end of "lowest-low" fertility? Population and Development Review, 35(4), 663-699. [CrossRef]

- IBGE (Instituto Brasileiro de Geografia e Estatística). (2024). Projeções da população: Brasil e unidades da federação. IBGE.

- Kirk, D. (1996). Demographic transition theory. Population Studies, 50(3), 361- 387. [CrossRef]

- Lessing, B. (2021). Conceptualizing criminal governance. Perspectives on Politics, 19(3), 854-873. [CrossRef]

- Lima, R. S., Bueno, S., & Mingardi, G. (2017). Estado, polícias e segurança pública no Brasil. Revista Direito GV, 12(1), 49-85. [CrossRef]

- Martine, G. (1996). Brazil's fertility decline, 1965-95: A fresh look at key factors. Population and Development Review, 22(1), 47-75. [CrossRef]

- Ministry of Justice and Public Security. (2025). Anuário Brasileiro de Segurança Pública 2025. Forum Brasileiro de Segurança Pública.

- Mongomery, R. M. (2024). Global Trends in Disease Burden, Morbidity, and Mortality: Implications of EmergingArtificial Intelligence (AI) Technologies. J Gene Engg Bio Res, 6(3), 01-08.

- Montgomery, R. M. (2025, March 20). Immigration, Human Capital and Economic Growth in Brazil: A Multidimensional Analysis.

- Montgomery, R. M. (2025)a. Evaluating Health Technologies in the Brazilian Public and Supplementary Health Systems: Policy, Economic, and Public Health Implications. Preprints.

- Muggah, R., Chainey, S., & Aguirre, K. (2019). Reducing homicide in Brazil: Insights from what works. Instituto Igarapé.

- Notestein, F. W. (1945). Population: The long view. In T. W. Schultz (Ed.), Food for the world (pp. 36-57). University of Chicago Press.

- Reher, D. S. (2004). The demographic transition revisited as a global process. Population, Space and Place, 10(1), 19-41. [CrossRef]

- Reichenheim, M. E., De Souza, E. R., Moraes, C. L., de Mello Jorge, M. H. P., Da Silva, C. M. F. P., & de Souza Minayo, M. C. (2011). Violence and injuries in Brazil: The effect, progress made, and challenges ahead. The Lancet, 377(9781), 1962-1975. [CrossRef]

- Rivera, M. (2016). The sources of social violence in Latin America: An empirical analysis of homicide rates, 1980–2010. Journal of Peace Research, 53(1), 84-99. [CrossRef]

- Thévenon, O., & Gauthier, A. H. (2011). Family policies in developed countries: A 'fertility-booster' with side-effects. Community, Work & Family, 14(2), 197-216. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, W. S. (1929). Population. American Journal of Sociology, 34(6), 959- 975.

- UNODC (United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime). (2019). Global study on homicide 2019. United Nations.

- Urdal, H. (2006). A clash of generations? Youth bulges and political violence. International Studies Quarterly, 50(3), 607-629. [CrossRef]

- World Bank. (2018). The costs of crime and violence: New evidence and insights in Latin America and the Caribbean. World Bank.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).