Despite extensive effort, significant advances in prevention and treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease (AD) have eluded us. Distracted by the amyloid hypothesis and the resultant massive effort, involving extensive investment in time and many billions of dollars, we face increasing burdens from AD and lack tools to significantly alter the course of this disease in our society and world.

New concepts and research results, rooted in solid science, with transformative data, but outside the popular paradigms, are neglected and not further pursued. In the following paper, I present discussions of several of these neglected but well supported concepts. Singly, or in combination, these radically simple ideas have the potential to change aspects of how we understand, prevent, and treat AD. I suggest paths we can follow to take advantage of these new ways of understanding dementing disease in general and AD in particular. We are on the verge of leveraging already known features of AD to the benefit of millions of people all over the world. We can do this now.

The Amyloid Hypothesis

The role of beta-amyloid (Aβ), a protein of unclear purpose [

1], in the etiology of AD is a contentious and evolving issue. The ubiquitous presence of A

related plaques in AD brains suggests a central role in AD pathology. Additionally, mutations in genes that control A

production (APP, PSEN1, PSEN2) are common in early onset familial AD [

2]. Presence of a common AD risk factor, the APOE4 allele, increases the rate of Aβ associated plaque formation and decreases the age at which that plaque formation becomes apparent. The amyloid hypothesis posits that Aβ associated plaque is the fundamental cause of AD, despite no clear understanding of why amyloid is present. The weaknesses in the amyloid hypothesis have been reported in multiple peer-reviewed papers [

3,

4] as well as in a prominent book and paper by Charles Piller published in 2025 and 2023 [

5,

6], which also report instances of serious research misconduct in AD research. Research into Aβ suggests it is often a response to inflammation [

7], but the cause of the inflammation is not completely understood. Viral and other infections, genetic propensities, chronic brain trauma, and toxic exposures all contribute to inflammation and to AD risk.

It seemed reasonable a few decades ago, that it might be helpful to get Aβ out of AD brains. We had, newly within our grasp, the means of Aβ removal from the brain through monoclonal antibodies. Evaluation of monoclonal antibody treatment of AD has been extensive. Perneczky et al. reported a summary of the monoclonal removal of Aβ in 2023 [

8]. Several monoclonal antibodies targeting Aβ were developed. Many of these antibodies entered clinical trials. Most failed to produce any significant useful improvement.

Aducanumab was approved by the FDA based on biomarker studies, but continued development was suspended due uncertain clinical benefit in subsequent trials. Improvement noted consisted of delay in worsening clinical status, or improved biomarkers. Significant toxicities were common, consisting mostly of brain edema and occasional brain bleeding [

9].

Lecanemab was studied in a phase 2 placebo controlled clinical trial published in 2023 [

10]. Although lecanemab decreased the rate of worsening in treated compared to placebo subjects, these changes did not meet the prespecified threshold to conclude benefit. However reduced brain amyloid and improved specific measures of clinical function (decreased rates of decline) favored active drug treatment over placebo, leading to accelerated approval from the FDA. In a follow-up trial, Clarity AD, lecanemab was found to decrease the rate of clinical decline and to improve biomarkers. Imaging revealed decreased brain Aβ burden in patients receiving the active drug compared to those receiving placebo [

11]. Aβ related Imaging abnormalities (ARIA) were noted in 21.5% of lecanemab treated patients and 9.5% of placebo treated patients. Deaths occurred in both actively treated and placebo treated patients, reflecting the general health status of the AD patient population.

Donanemab, another anti- Aβ monoclonal antibody was recently evaluated. In the 2023 phase 3 Trailblazer-ALZ 2 Randomized Clinical Trial, donanemab was found to have decreased the rate of AD progression in the actively treated group by 37-38% compared to placebo treatment. ARIA were documented in 36.8% of donanemab treated subjects compared with 14.9% treated with placebo. There were 3 deaths in the actively treated patients compared with 1 death in the placebo group, all being ascribed to treatment. FDA approval was granted to donanemab in 2023 for AD treatment.

Some authors have heralded the arrival of these new drugs [

12]. Others have expressed concern that the clinical benefit of slowing disease progression to a modest degree may not justify the toxicities of the treatment. A progressive understanding of the newer generation of anti-amyloid monoclonal antibody treatment trials suggests possible benefit through the nuances of patient selection and use of progressively refined agents [

13]. Although toxicities arising from treatment with anti-amyloid therapies are concerning or even alarming, the relentless nature of AD, ending in a period of marked disability from dementia followed by death may justify tolerating the risk of toxicities in the quest for longer survival with preservation of some cognitive function that would otherwise be lost.

To this author, a pressing need in AD research involves understanding the etiology of the inflammation related injury that appears to be causing Aβ to accumulate in AD brains. Much of the discussion in subsequent portions of this manuscript will address data that suggests what may be the cause(s) of that injury.

Toxic Exposures in AD

From within and externally, humans are exposed to a variety of substances, many of which can cause symptoms or disease. These toxins are ubiquitous. Human physiology has devised through evolution several ways to limit the adverse consequences of toxic exposures. Some of these detoxification pathways are well known, such as the cytochrome P450 enzyme systems or the glutathione s-transferase genes and pathways. Many other detoxification genes and enzymes exist in humans. Societies and governments may impose limitations on toxins, how they are made, distributed, stored, and used, as well as how environmental and other exposures are prevented and/or managed. Recent publications have presented a compendium of toxins that have evidence supporting a potential relationship to neurodegenerative diseases [

14,

15,

16,

17].

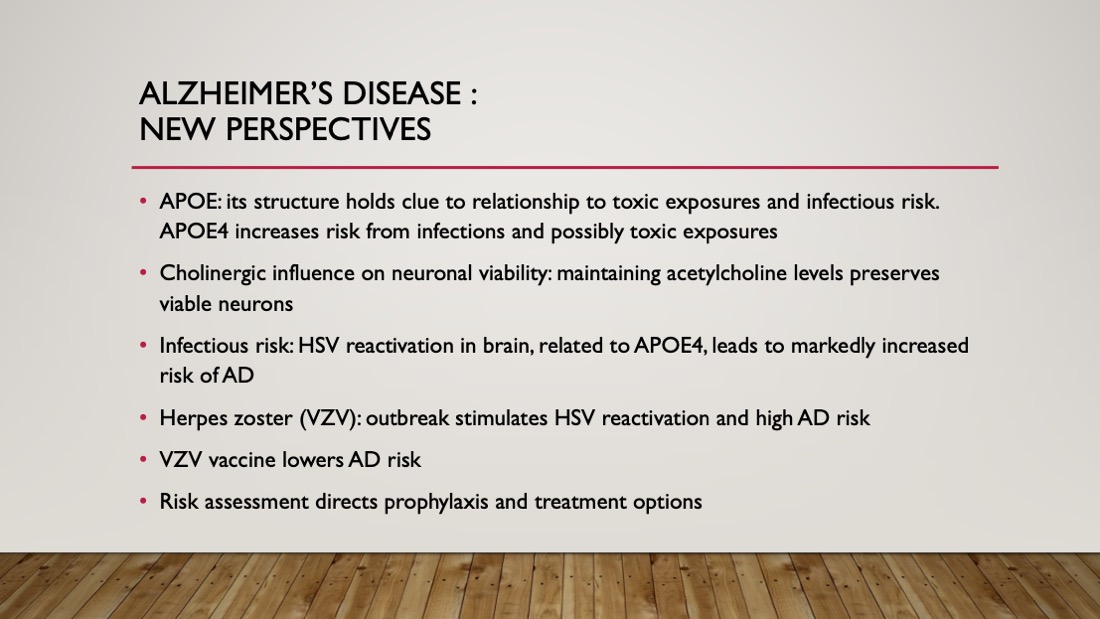

The APOE Relationship to Detoxification

A clue about AD etiology has emerged through aspects of APOE physiology. APOE is a lipoprotein involved in lipid transport, well known as a marker of AD risk. Of the three types of APOE in the body, called APOE2, APOE3, and APOE4 (we each have 2, one from each parent), carriers of APOE4 have significantly increased lifetime AD risk. APOE2 carriers are significantly protected. APOE3 is neutral [

18].

The clue is in the structure of the APOE subtypes. APOE is a 299 amino acid chain. Only 2 sites in the chain vary, sites 112 and 158. In APOE2 both sites are occupied by cysteine amino acids. In APOE4 both sites are arginine amino acids. APOE3 has cysteine at site 112 and arginine at site 158. Cysteine’s major role in the body is as an antioxidant or detoxifying agent through cysteine’s conversion to glutathione, which is the body’s chief antioxidant, also playing a key role in resisting infections [

19,

20]. Arginine has no antioxidant or infection control capability. Based on the presence of cysteine or lack thereof at these 2 variable sites in APOE, one might expect variable antioxidant, detoxification and host defense capabilities based on these structural differences. APOE2 should be better at protecting from toxic exposures or from oxidative stress as well as viral and other infections [

21]. Might that be part of the reason for beta amyloid’s presence in AD brains, responding to injury due to toxic exposures and to infections? A simple way to express the resistance to toxic exposure/oxidative stress and infections might be the number of cysteine molecules present in each cell related to the APOE status of everyone. People with APOE2/2 have 4 cysteines. APOE4/4 individuals have no cysteines. APOE3/3 carriers have 2 cysteines, and so on. Given that every cell in the body has genetically determined APOE characteristics, the considerable impact of the APOE system on various risks and conditions, including infections and toxic exposures, may be explained.

Strategy for Studying Detoxification in AD

Realizing that the cysteine/glutathione detoxification system in the body is just one of several systems that play a role in protecting us from various exposures, I/we wondered if other detoxification pathways, through the genes that control them, might also play a role in AD risk. Many of these pathways are well known, such as the cytochrome P450 and the glutathione specific pathways, though there are several others. A decision was made to evaluate these several detoxification pathways, potentially yielding further clues about the relevance of detoxification to AD risk.

Resources of the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO), a data repository managed by the National Center for Biotechnology Information, were utilized. Thousands of datasets are organized in the GEO archives, comparing gene expression with control, in various ways. Gene expression is an important method the body uses to control activity of genes to meet the body’s particular needs in specific tissues and organs. I used the keywords human, RNA-seq, GEO2R, and Alzheimer’s. Eight pertinent datasets were identified that met criteria for inclusion in the planned study. These datasets compared AD and non-AD groups, but other innovative protocols were also identified and included in this project.

The plan I identified to investigate the role of detoxification gene activity relied upon a group of “genes of interest” for which evidence suggested a role in detoxification. 203 genes were identified as detoxification genes. I planned to use a process called gene set expression analysis (GSEA) to compare gene expression in the 203 genes of interest in an AD cohort with a non-AD cohort. A complimentary, but different, bio-banked tissue-based method was designed. Through analysis via GSEA, detoxification gene expression comparing AD patients and non-AD patients was performed in a commercial genomics lab. We chose liver tissue since most detoxification processes occur in the liver. A manuscript was created that describes in detail the design and results of this project [

22].

I found 162 genes with statistically significant differential expression in the AD groups versus the non-AD groups. Roughly half of these differentially expressed genes showed decreased expression. Half showed increased expression, thought be a compensatory reaction to the toxins not removed by the poorly expressed genes. Statistical significance was demonstrated and was extreme in some of the groups. Many of the differentially expressed detoxification genes were the same in both parts of the study, further increasing the probability that the differences in gene expression are playing a role in AD risk.

Since the gene expression data discussed above shows a high likelihood that detoxification deficiencies play a role in dementia (and possibly other conditions) I propose a path forward to further investigate detoxification relationships and mechanisms. Questions to be answered might be:

- -

which specific toxins are not being removed from people? Candidates include all the xenobiotics including heavy metals, herbicides, pesticides, drugs, microplastics, PFAS compounds (forever chemicals), and endogenous substances (mainly neurotransmitters, hormones) and perhaps more.

- -

are there effective ways to improve the “clean-up process” in the body?

- -

if we can decrease or eliminate the “toxins within”, does it matter? Do any diseases or conditions get less severe or go away completely?

Providing meaningful answers to the above will have challenges, but would be feasible, at least to a degree. The effort involved would potentially be substantial.

If detoxification does matter, and it appears likely, based on the above, there is a specific and simple method that should be considered in improving detoxification, that of bile acid sequestration. A discussion of physiology is pertinent to understanding this important concept.

Bile Acid Sequestration, Using Bile Acid Sequestrants (BAS)

The liver is widely accepted as the dominant organ in eliminating toxic substances from the body [

23]. The liver begins this process through altering the toxic agents in a few ways. The ways it does this are barely pertinent here and will not be further discussed in this paper. The liver then excretes the toxins into the bile. Bile is a detergent-like substance that helps us digest fat and absorb it as food. However, bile is far more complex. It, and the toxins it carries, are excreted into the upper part of the small intestine. Bile then travels down the approximately 30 feet of small intestine to the terminal ileum, which is in the final 10-20 cm of the small intestine. There, interestingly, the body reabsorbs the bile, and the toxins with it, and sends them, through specialized blood vessels, back to the liver, where they are repackaged and re-excreted to do it all over again. The process is called entero-hepatic recirculation [

24]. Some toxins can barely leave the body at all due to this odd physiologic mechanism. I have seen no speculation as to why evolution would have favored this process and facilitated its creation. It does conserve bile, so the body does not have to use resources to synthesize it [

25].

At this point a discussion of BAS is in order. These drugs are ion-exchange resins, which means they can attach to various substances such as bile and associated toxins and carry them out of the body in the feces. The liver then is compelled to produce more bile, which it does using cholesterol [

26]. This process lowers serum cholesterol levels, which is quite useful in some patients. Prior to the widespread use of statins, BAS treatment was frequently used. Outcome studies demonstrated that BAS use decreased risks of myocardial infarction and stroke, consistent with the lowering of LDL cholesterol. BAS were confirmed to lack significant toxicities. The use of BAS is often complicated by heartburn and abdominal bloating, usually mild and manageable [

27].

BAS use would be expected to lower toxins, excreted through the bile, in the body. A few studies confirm this toxin lowering property of BAS use. In a 2024 publication, a group of highly exposed Danish farmers with very elevated PFAS levels due to environmental contamination from firefighting foam was identified. They were treated with cholestyramine, the oldest and most widely used BAS. PFAS levels were promptly brought down with 12 weeks of treatment [

28]. Normally these toxins have a half-life of many years. Aside from reports of BAS human detoxification from ochratoxin A toxicity [

29] and a case report of canine cyanobacterial (microcystin) toxicosis successfully treated with cholestyramine [

30], I could find no other reports in the peer reviewed literature of use of BAS in detoxification.

Part of the complexity of bile involves its impact on other parts of the body as it circulates in the blood stream. The brain is impacted by the various types of bile to which it is exposed. The relationships are complex [

31]. In general, higher levels of bile acid sub-types in the brain are more likely to be associated with higher risk of dementia, however this varies with the specific sub-types. In one study, exposure to BAS appears to be associated with a lowering of the risk of AD, but the study was retrospective, not randomized, and its results are disputed [

32]. What is clear is that use of BAS does not appear to be associated with

increased risk of dementia.

The next steps in analysis of BAS impacts on dementia risk might involve research on the toxins that bile may be expected to carry out of the body, followed by studies evaluating risks and benefits of BAS use in populations with, or at high risk of, dementia. If the BAS were investigational agents, being researched in the standard approach seeking FDA approval, extensive and expensive safety and efficacy trials would be needed. However, FDA approval was long ago achieved for the use of BAS agents in lipid lowering. The phase 1 and 2 data used years ago for the initial BAS approvals established the safety of BAS treatment in lipid lowering. Additional phase 3 trials, startlingly expensive, would be required for the FDA to grant a new indication for use in AD. Such an approval would probably not yield the magnitude of revenue to justify the expense of phase 3 trials, the BASs being generic and quite low cost, although the new indication would usually compel third party payers to cover the cost of BAS treatment for AD. Since BAS agents can already be prescribed for any purpose the physician and patient feel is justified, perhaps another approach would be feasible and appropriate. Such “off label” use is common for many drugs. I would favor more limited clinical trials, not of the magnitude required for the FDA to grant a new indication, but of adequate size to inform the physician and patient of whether BAS should play some role in AD therapeutics. Such trials might be funded through grants from interested granting organizations. In this way, patients, their physicians, and the public in general can reach their own conclusions on whether BAS use is warranted in any patient. In a sense, each individual patient, by utilizing and paying for the relatively low-cost generic medication, is funding the effort to understand the role of BAS in AD therapeutics. Information from this paper, any pertinent additional research, and the opinions of patients, their families, and involved clinicians can be utilized to chart a particular course of action. No one entity will stand to gain any significant revenue in the described process, a welcome change from the typical course of pharmaceutical medicine development involving massive investment, requiring compensatory massive revenue.

Additional Detoxification Options

While additional detoxification options may be useful methods that may be found to be valuable, the focus of this paper is on the methods articulated in this paper. Interested readers and researchers may find useful information in a PubMed search or in

The Toxin Solution, a book by Joseph Pizzorno detailing lifestyle and natural remedies that may be of considerable benefit [

33].

Acetylcholine-Esterase Inhibitors (AChEIs)

Acetylcholine is a neurotransmitter with a pivotal role in AD [

34]. Normal neurological function requires normal levels of acetylcholine. AD is characterized by low to absent acetylcholine levels in the brain. Nerve cells that produce and excrete acetylcholine are called cholinergic neurons. Normal levels of acetylcholine from cholinergic neurons are required to maintain the health and integrity of neurons in the brain. Acetyl choline deficiency in AD appears to manifest initially in the basal forebrain, an area roughly posterior to the eyes and nasal structures [

35]. The decreased viability of those initially affected cholinergic neurons spreads to adjacent cholinergic neurons, with progressively larger areas of poorly functioning brain cells and worsening brain function.

Acetylcholine produced in the brain is normally metabolized and its effects terminated by the enzyme acetylcholine-esterase (AChE) in the normal brain. A method of increasing acetylcholine activity involves inhibiting AChE through acetylcholine-esterase inhibitors (AChEIs), several of which are available. AChEIs have been shown to increase acetylcholine levels in the brain. Although AChEIs have been FDA approved for treatment of AD, the benefits in established AD are very subtle. Multiple reports show convincing evidence of improved brain function and prevention of the atrophy that characterizes AD brains with AChEIs, however AChEI treatment is required

prior to the onset of dementia for significant benefit [

36,

37,

38,

39,

40]. Reports are suggesting a role for nerve growth factor (NGF) in promoting the long-term survival of cholinergic neurons, with AChEIs promoting healthy levels of NGF [

41,

42,

43,

44]. The hypothesis of hyperphosphorylation of tau being the early mechanism on the way to AD neurodegeneration is newly proposed as a part of the cascade of causation of NGF deficiency [

45].

Methanesulfonyl fluoride (MSF) is an emerging AChEI with considerably improved efficacy in prophylaxis of AD as well as in treatment of established AD compared with older AChEIs. MSF’s improved performance derives from its irreversible AChE inhibition. Given that peripheral AChE is replenished much more quickly than AChE in the brain, it stands to reason that brain acetylcholine will be preserved while peripheral acetylcholine will decline more rapidly. Benefits accrue in the brain while side effects are greatly limited in the periphery. The limitation of peripheral toxicities, with enhanced brain effects, accounts for the significantly improved impact of MSF in AD subjects [

43]. MSF can decrease AChE by 70% while donepezil maximum AChE decrease is about 30%. MSF is going through the FDA approval process at present, as funding permits. It appears to be a major advance, oddly limited by its lack of expense, decreasing expected recoup of the expenses of the approval process. The challenges of getting MSF through the FDA hurdles are well documented in the book by Donald Moss, PhD, entitled:

My Journey to a Next Generation Treatment for Alzheimer’s Disease [

46]. These FDA approval challenges, while understandable in the context of a market driven biopharmaceutical industry, should not be tolerated in an enlightened, advanced society. Regulatory reform is needed to redress these wrongs.

Herpes Simplex Infection (HSV) and AD

HSV is a common, seemingly innocuous infection. The prevalence of HSV 1 was 47.8% and HSV 2 11.9% in the US population aged 14-49. The incidence increases with age. It has declined from 1999 to 2016. (NCHS data brief #304 Prevalence of Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1 and Type 2 in Persons Aged 14–49: United States, 2015–2016). HSV1 is well known for causing “cold sores” or “fever blisters”. HSV2 more commonly causes genital sores. A closer look suggests that HSV may be part of the etiology of AD in many subjects. In a 1981 publication, HSV1 DNA was found in 6 of 11 brains in autopsy specimens (as reported in the text, although in their Table 1, HSV was found in 7 of 11) [

47]. After an initial infection, often early in life, HSV assumes a latent state, only to later reactivate spontaneously or because of stress. HSV is present in the brains of many or most AD brains at autopsy. Subjects without AD may also have HSV in autopsy brain biopsies [

48]. Multiple studies note the strengthening association of HSV and AD [

49,

50]. Several recent reports note that APOE status interacts with the HSV associated risk of AD. In a 2006 study, Burgos, et al. report that in mice, APOE4 carriers had a marked increase in brain HSV compared to APOE3 carriers after experimental HSV inoculation [

51]. In a 1997 article, Itzhaki et al. report that having either an APOE4 allele, or positive HSV1 history alone does not appear to increase risk of AD, however having both together results in markedly increased risk. Having an APOE4 allele increases the risk of HSV activating in the brain [

52]. APOE4 would be expected to be associated with susceptibility to infections, lacking cysteine at variable sites 112 and 158 and therefore having glutathione deficiency relative to APOE3 (which has one cysteine at site 112) and even more so to APOE2 (which has cysteine at both sites 112 and 158) [

53]. In addition to its role in detoxification, glutathione plays a nuanced role in immune function; low levels being associated with increased risk of a variety of infections [

19].

Indeed, APOE4 carriers do exhibit higher HSV loads in the brain than non-APOE4 carriers. APOE4 carriage is also associated with more severe disease from HIV infection and increased severity in SARS-CoV-2 (COVID-19) infections. On the other hand, the APOE4 allele is associated with less severe manifestations of both hepatitis B and C infections, possibly explaining in part why the presence of APOE4 is an ongoing part of the spectrum of human genetic variability, having not been eliminated by evolutionary pressures [

54].

Several drugs, notably valacyclovir and acyclovir, are effective in limiting infection with HSV and decreasing clinical manifestations of such infection. These drugs also limit reactivation of latent HSV infection. Inexpensive, well tolerated, and available orally, these drugs are logical agents to evaluate in AD prevention and treatment [

55,

56].

Clinical Trial Data, Phase 2 Trials. Phase 3 Trials Are Anticipated but Not Yet Started

In the VALZ-Pilot trial of valacyclovir in 33 patients who had early-stage AD, an APOE4 allele, and anti-herpes antibodies, 4 weeks of valacyclovir treatment resulted in modest improvement in Mini-Mental State Examination scores and “higher CSF sTREM2 levels (which)have been associated with increased gray-matter volume, slower rates of decline in hippocampal volume and memory, and slower rates of clinical progression in patients with early-stage AD and mild cognitive impairment.” [

57] There was no placebo group in this trial, which limits the conclusions that may be drawn.

In the VALAD trial, 130 mild AD patients who also had HSV seropositivity got valacyclovir versus placebo. The subjects were evaluated with tests of cognition, amyloid PET scans, and CSF biomarkers. Results are pending publication [

55].

Valacyclovir for Mild Cognitive Impairment (VALMCI) is a trial in 50 HSV seropositive mild cognitive impairment patients who received valacyclovir versus placebo and underwent cognitive assessment as well as amyloid PET scanning. Results were anticipated in 2024 but are not yet reported.

In a 2025 paper, Feng and colleagues reported data regarding transposable element (TE) dysregulation via human herpes virus activity, and consequent inflammation in various brain structures. Valacyclovir and acyclovir inhibited the TE dysregulation [

58]. Feng at al. also noted TE dysregulation in association with non HSV members of the human herpesvirus family.

We await with anticipation the results of ongoing research projects into the relationship of HHV, HSV, and AD. The impact of anti-HHV therapeutics on AD prevention and treatment appears promising.

Varicella Zoster Virus (VZV), Aka Herpes Zoster or Shingles/Chickenpox Virus

Though both VZV and HSV are members of the Herpesviridae family of viruses, VZV, the causative agent for chickenpox, and HSV, cause separate and distinct clinical manifestations. Without vaccination, VZV usually occurs in childhood, and may reactivate as shingles, generally occurring later in life. Person to person transmission of chickenpox occurs when an uninfected person is exposed to an infected person or a person with active lesions of shingles. VZV is highly contagious to individuals lacking a prior history of chicken pox or VZV vaccination. When that person is exposed to VZV, either from another person with chicken pox or with a shingles outbreak, chicken pox is highly likely. Both chicken pox and shingles tend to occur only once, although there are rare exceptions in some individuals who may have multiple outbreaks of either [

59].

Shingles is manifest as a vesicular eruption, usually in a single dermatome, due to reactivation of latent virus from a prior episode of chicken pox. Pain, which can be severe and long lasting, is common. The VZV vaccine, Zostavax, was introduced in 2006. FDA approval was for persons age 50 and older, but the CDC recommended reserving use of Zostavax for persons age 60 and older due to evidence of declining efficacy over time. Being a live, attenuated virus vaccine, Zostavax was contraindicated in immunocompromised persons. Shingrix VZV vaccine was released in 2017 for use in persons age 50 years and older, and given in 2 doses, 2-6 months apart. Being a recombinant vaccine, and not a live virus vaccine, Shingrix is also recommended in immunocompromised persons age 18 and older. Both Zostavax and Shingrix vaccines have demonstrated significant efficacy in reducing the risk of shingles. Shingrix reduces the risk of shingles by 97.2% [

60]. Zostavax reduced the incidence of shingles by 51%, but that vaccine was withdrawn from the US market in 2020. [

61,

62].

Vaccination with Zostavax or Shingrix also reduces the risk of subsequent AD in addition to lowering the risk of shingles. Data shows that Zostavax vaccination reduces the incidence of AD by 20% while Shingrix vaccination reduces the risk of AD by 30-40%. The improved AD prophylaxis of Shingrix compared to Zostavax is consistent with the improved efficacy of Shingrix in preventing VSV reactivation and consequent shingles [

63]. The studies evaluating the impact of VZV vaccination on AD risk are mostly observational and not interventional, limiting the certainty of conclusions of benefit. More research may be useful in refining our understanding of the relationships of VSV vaccination and AD risk.

Chickenpox is effectively prevented with childhood vaccination if the vaccine is administered prior to the exposure of the child to VZV virus. The vaccine is a live virus vaccine and should not be administered to an immunocompromised person. The incidence of shingles in persons previously vaccinated with chickenpox vaccine is 78-80% lower than in persons who did not receive chickenpox vaccine. Unexpectedly, in a population widely vaccinated against chickenpox, the consequent decreased level of ambient exposure to chickenpox virus in the general population is associated with lower levels of antibodies to VZV in previously

unvaccinated individuals and is related to paradoxically increased rates of shingles in that unvaccinated population [

64].

The relationship of VZV to AD is largely a result of VZV reactivation as shingles, stimulating reactivation of HSV in persons harboring latent HSV from prior HSV infection. The reactivated HSV then may result in brain inflammation typical of HSV. Aside from the impact of HSV reactivation from VZV infection or reactivation, brain inflammation associated with VZV infection, unrelated to HSV presence in the brain, typically results in elevated pro-inflammatory cytokines (IL-6 and TNF-alpha) and blood-brain barrier compromise. This two-pronged assault on the brain may explain the adverse impact of VZV in AD risk and the reduction of AD risk associated with VZV vaccination [

63,

65].

Harvesting the Low Hanging Fruit

The concepts and research discussed above lead to a logic trail that can and should be scrutinized and potentially implemented on a case-by-case basis. The potential benefit in prophylaxis and treatment of AD is difficult to accurately estimate, but is highly likely to be tangible, and may be marked.

Risk Assessment

The first step in the prophylaxis and treatment algorithm is a risk assessment.

Highest risk persons are those with one or two APOE4 alleles (3-4-fold increased risk with one-, and 9-15-fold increased risk with two alleles [

66])

and a family history of AD in one or more first degree relatives, further increasing AD risk beyond having one or two APOE4 alleles, but the degree of risk increase is not defined [

67]. 3 points

Less elevated risk, but still actionable, would be either a family history of AD in one or more first degree relatives, FDR (1.73 fold increase in risk for one FDR and 3.98 fold increase for 2 FDRs [

68]) or one APOE4 allele positivity. 2 points

Family history of AD plus history of HSV infection or seropositivity. This combination of risk factors is not specifically addressed in published literature. However, the separate pathways of risk suggest additive levels of risk approximating a 4-fold risk elevation with this combination. 2 points

The presence of a history of HSV infection or HSV seropositivity alone. 2.44-fold risk increase [

69]. 1 point

A history of recent VZV/shingles activity. 1.33-fold increase in risk [

70]. 1/2 point

A history of traumatic brain injury. 1.32-fold risk increase, with higher risk from more severe injury or multiple injuries [

71]. 1/2 point

The general assessment of AD risk is difficult to quantify. The above assessment is an estimation and should be considered in combination with person specific features such as age, comorbidities, patient preferences, and with advice and consultation with a trusted and expert medical care provider.

Intervention Options

3 points: AD is high risk. Prophylaxis should be strongly considered.

2 points: AD is above average risk. Prophylaxis is a reasonable option.

1 point: AD is less likely. Although prophylaxis is a consideration, the benefits of prophylaxis are likely to be of lower magnitude.

Prophylaxis Options

Donepezil titrated to optimal dose. Other AChEIs could be considered. MSF, when approved, is likely to be more effective than any of the presently available AChEIs.

HSV prophylaxis should be added to AChEIs if there is a history of HSV infection or seropositivity. Valacyclovir 500 mg once daily in immunocompetent persons is likely to be effective prophylaxis. It is unclear how effective valacyclovir prophylaxis would be in general and in HSV negative persons in particular. Higher risk HSV positive persons would be expected to benefit most from valacyclovir prophylaxis.

VZV vaccination should be considered at all risk levels, and more generally across the population regardless of AD risk. Whether VZV vaccination benefits persons without a history of chickenpox or shingles, or who had childhood immunization for chickenpox is unclear and may be a fruitful topic for future research.

Use of BAS to enhance excretion of various toxins requires significant additional research to evaluate its efficacy, if any, in AD prevention. What is currently known suggests a possible benefit. However, in individuals with an indication for LDL cholesterol lowering, the specific benefits in enhanced excretion of at least some toxins may be considered in the decision whether to utilize BAS treatment.

AD Treatment Options

Although prophylaxis offers the highest probability of benefit, the use of the above prophylaxis methods should be considered for treatment of AD on a case-by-case basis.

Conclusions

The above paper presents facts and suggests courses of action for prevention and possibly treatment of AD, the benefits of which should be obvious to impartial observers. The assessment and suggested medications are inexpensive and safe but should be supervised by an appropriately trained and competent physician. Unfortunately, the field of AD research and prevailing thought in academic AD centers has been unduly influenced by the amyloid hypothesis. While unethical and profit-driven research has or should have stained and limited the vision of the appropriate role of anti-amyloid methods in prophylaxis and treatment of AD, ongoing research needs to be continued into these agents. However, the considerable toxicities, limited benefits, and outrageous expense of anti-amyloid methods stand in stark contrast to the safety, economy, and research-supported likely benefits of the methods articulated above.

We need for the AD research community to reassess its undue emphasis on anti-amyloid therapies, while continuing appropriate research into associated risks and benefits. Instead, an evidence-based re-direction is needed to do the following:

- -

Perform widespread risk assessment of AD, emphasizing family history, APOE status, HSV history or serology, and history of TBI.

- -

Provide AChEI prophylaxis in high AD risk individuals.

- -

Conduct appropriately designed clinical trials of AChEIs that will confirm whether such treatment decreases AD risk.

- -

Provide anti-HSV medication in targeted persons, studying the results of anti-HSV methods with well-designed research projects.

- -

Encourage widespread use of anti-VZV vaccination in appropriate populations.

- -

Increase our understanding of the role of detoxification pathways in the body.

- -

Determine just what toxins are not being effectively removed from the body.

- -

Confirm whether other experimental designs also show altered detoxification in AD.

- -

Determine whether toxin reduction or removal from the body has any impact on AD incidence.

- -

Design and implement research evaluating the consequences of adherence to the above algorithms, prophylaxes, and treatments. Adherence to the highest ethical standards in such research is paramount.

- -

Eliminate the perverse roles of financial and prestige related conflicts of interest, rampant in the AD research efforts to date.

- -

Proceed promptly to establishing through any means required to prove or disprove the already partially established benefits of MSF and finish the FDA approval process for this transformative agent.

- -

Create a mechanism to prevent other approval blockades like those of the MSF challenges, while preserving a rigorous evaluation of newly developed or repurposed agents, thereby safeguarding the public from unproven remedies.

Following the suggestions and algorithms articulated in this paper holds the potential to have a transformative impact on a tragic and worsening epidemic of incalculable consequence to the world’s population. Even a small reduction of incidence achieved through these methods would have benefits difficult to estimate, but likely to be substantial.

References

- Hiltunen, M., van Groen, T. & Jolkkonen, J. (2009). Functional roles of amyloid-beta protein precursor and amyloid-beta peptides: evidence from experimental studies. J Alzheimers Dis. 18, 401-412. [CrossRef]

- Harald Hampel 1, John Hardy 2, Kaj Blennow 3,4, Christopher Chen 5, George Perry 6, Seung Hyun Kim 7, Victor L Villemagne 8,9, Paul Aisen 10, Michele Vendruscolo 11, Takeshi Iwatsubo 12, Colin L Masters 13, Min Cho 1, Lars Lannfelt 14,15, Jeffrey L Cummings 16, Andrea Vergallo 1,✉ (2021). The Amyloid-β Pathway in Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol Psychiatry.

- Kepp, K. P., Robakis, N. K., Hoilund-Carlsen, P. F., Sensi, S. L. & Vissel, B. (2023). The amyloid cascade hypothesis: an updated critical review. Brain. 146, 3969-3990. [CrossRef]

- Hoilund-Carlsen, P. F., Alavi, A., Castellani, R. J., Neve, R. L., Perry, G., Revheim, M. E. & Barrio, J. R. (2024). Alzheimer’s Amyloid Hypothesis and Antibody Therapy: Melting Glaciers? Int J Mol Sci. 25. [CrossRef]

- Piller, C. (2025). Doctored: fraud, arrogance, and tragedy in the quest to cure Alzheimer’s. One Signal Publishers, Atria, New York.

- Piller, C. (2023). Brain games? Science. 382, 754-759. [CrossRef]

- Kinney, J. W., Bemiller, S. M., Murtishaw, A. S., Leisgang, A. M., Salazar, A. M. & Lamb, B. T. (2018). Inflammation as a central mechanism in Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 4, 575-590. [CrossRef]

- Perneczky, R., Jessen, F., Grimmer, T., Levin, J., Floel, A., Peters, O. & Froelich, L. (2023). Anti-amyloid antibody therapies in Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 146, 842-849. [CrossRef]

- Budd Haeberlein, S., Aisen, P. S., Barkhof, F., Chalkias, S., Chen, T., Cohen, S., Dent, G., Hansson, O., Harrison, K., von Hehn, C., Iwatsubo, T., Mallinckrodt, C., Mummery, C. J., Muralidharan, K. K., Nestorov, I., Nisenbaum, L., Rajagovindan, R., Skordos, L., Tian, Y., van Dyck, C. H., Vellas, B., Wu, S., Zhu, Y. & Sandrock, A. (2022). Two Randomized Phase 3 Studies of Aducanumab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. J Prev Alzheimers Dis. 9, 197-210. [CrossRef]

- Swanson, C. J., Zhang, Y., Dhadda, S., Wang, J., Kaplow, J., Lai, R. Y. K., Lannfelt, L., Bradley, H., Rabe, M., Koyama, A., Reyderman, L., Berry, D. A., Berry, S., Gordon, R., Kramer, L. D. & Cummings, J. L. (2021). A randomized, double-blind, phase 2b proof-of-concept clinical trial in early Alzheimer’s disease with lecanemab, an anti-Abeta protofibril antibody. Alzheimers Res Ther. 13, 80. [CrossRef]

- van Dyck, C. H., Swanson, C. J., Aisen, P., Bateman, R. J., Chen, C., Gee, M., Kanekiyo, M., Li, D., Reyderman, L., Cohen, S., Froelich, L., Katayama, S., Sabbagh, M., Vellas, B., Watson, D., Dhadda, S., Irizarry, M., Kramer, L. D. & Iwatsubo, T. (2023). Lecanemab in Early Alzheimer’s Disease. N Engl J Med. 388, 9-21. [CrossRef]

- Jeffrey Cummings, A. M. L. O., Davis Cammann, Jayde Powell, Jingchun Chen (2024). Anti-Amyloid Monoclonal Antibodies for the Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease. BioDrugs.

- Avgerinos, K. I., Manolopoulos, A., Ferrucci, L. & Kapogiannis, D. (2024). Critical assessment of anti-amyloid-beta monoclonal antibodies effects in Alzheimer’s disease: a systematic review and meta-analysis highlighting target engagement and clinical meaningfulness. Sci Rep. 14, 25741. [CrossRef]

- Dhapola, R., Sharma, P., Kumari, S., Bhatti, J. S. & HariKrishnaReddy, D. (2024). Environmental Toxins and Alzheimer’s Disease: a Comprehensive Analysis of Pathogenic Mechanisms and Therapeutic Modulation. Mol Neurobiol. 61, 3657-3677. [CrossRef]

- Vasefi, M., Ghaboolian-Zare, E., Abedelwahab, H. & Osu, A. (2020). Environmental toxins and Alzheimer’s disease progression. Neurochem Int. 141, 104852. [CrossRef]

- Mir, R. H., Sawhney, G., Pottoo, F. H., Mohi-Ud-Din, R., Madishetti, S., Jachak, S. M., Ahmed, Z. & Masoodi, M. H. (2020). Role of environmental pollutants in Alzheimer’s disease: a review. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 27, 44724-44742. [CrossRef]

- Rahman, M. A., Rahman, M. S., Uddin, M. J., Mamum-Or-Rashid, A. N. M., Pang, M. G. & Rhim, H. (2020). Emerging risk of environmental factors: insight mechanisms of Alzheimer’s diseases. Environ Sci Pollut Res Int. 27, 44659-44672. [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Calle, R., Konings, S. C., Frontiñán-Rubio, J., García-Revilla, J., Camprubí-Ferrer, L., Svensson, M., Martinson, I., Boza-Serrano, A., Venero, J. L., Nielsen, H. M., Gouras, G. K. & Deierborg, T. (2022). APOE in the bullseye of neurodegenerative diseases: impact of the APOE genotype in Alzheimer’s disease pathology and brain diseases. Mol Neurodegener. 17, 62. [CrossRef]

- Droge, W. & Breitkreutz, R. (2000). Glutathione and immune function. Proc Nutr Soc. 59, 595-600. [CrossRef]

- Pastore, A., Federici, G., Bertini, E. & Piemonte, F. (2003). Analysis of glutathione: implication in redox and detoxification. Clin Chim Acta. 333, 19-39. [CrossRef]

- Finch, C. E. & Morgan, T. E. (2007). Systemic inflammation, infection, ApoE alleles, and Alzheimer disease: a position paper. Curr Alzheimer Res. 4, 185-189. [CrossRef]

- McCaulley, M. E. (2025). Impaired Pathways of Detoxification and Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease in Humans - Differential Gene Expression Studies via Gene Set Expression Analysis. medRxiv. 2025.2005.2029.25328282. [CrossRef]

- Grant, D. M. (1991). Detoxification pathways in the liver. J Inherit Metab Dis. 14, 421-430. [CrossRef]

- Chen, M. J., Liu, C., Wan, Y., Yang, L., Jiang, S., Qian, D. W. & Duan, J. A. (2021). Enterohepatic circulation of bile acids and their emerging roles on glucolipid metabolism. Steroids. 165, 108757. [CrossRef]

- Ridlon, J. M. & Gaskins, H. R. (2024). Another renaissance for bile acid gastrointestinal microbiology. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 21, 348-364. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y., Li, Q., Ou, G., Yang, M. & Du, L. (2021). Bile acid sequestrants: a review of mechanism and design. J Pharm Pharmacol. 73, 855-861. [CrossRef]

- Ast, M. & Frishman, W. H. (1990). Bile acid sequestrants. J Clin Pharmacol. 30, 99-106. [CrossRef]

- Moller, J. J., Lyngberg, A. C., Hammer, P. E. C., Flachs, E. M., Mortensen, O. S., Jensen, T. K., Jurgens, G., Andersson, A., Soja, A. M. B. & Lindhardt, M. (2024). Substantial decrease of PFAS with anion exchange resin treatment - A clinical cross-over trial. Environ Int. 185, 108497. [CrossRef]

- Hope, J. H. & Hope, B. E. (2012). A review of the diagnosis and treatment of Ochratoxin A inhalational exposure associated with human illness and kidney disease including focal segmental glomerulosclerosis. J Environ Public Health. 2012, 835059. [CrossRef]

- Rankin, K. A., Alroy, K. A., Kudela, R. M., Oates, S. C., Murray, M. J. & Miller, M. A. (2013). Treatment of cyanobacterial (microcystin) toxicosis using oral cholestyramine: case report of a dog from Montana. Toxins (Basel). 5, 1051-1063. [CrossRef]

- Huang, F., Pariante, C. M. & Borsini, A. (2022). From dried bear bile to molecular investigation: A systematic review of the effect of bile acids on cell apoptosis, oxidative stress and inflammation in the brain, across pre-clinical models of neurological, neurodegenerative and neuropsychiatric disorders. Brain Behav Immun. 99, 132-146. [CrossRef]

- Varma, V. R., Wang, Y., An, Y., Varma, S., Bilgel, M., Doshi, J., Legido-Quigley, C., Delgado, J. C., Oommen, A. M., Roberts, J. A., Wong, D. F., Davatzikos, C., Resnick, S. M., Troncoso, J. C., Pletnikova, O., O’Brien, R., Hak, E., Baak, B. N., Pfeiffer, R., Baloni, P., Mohmoudiandehkordi, S., Nho, K., Kaddurah-Daouk, R., Bennett, D. A., Gadalla, S. M. & Thambisetty, M. (2021). Bile acid synthesis, modulation, and dementia: A metabolomic, transcriptomic, and pharmacoepidemiologic study. PLoS Med. 18, e1003615. [CrossRef]

- Pizzorno, J. E. (2017). The toxin solution: how hidden poisons in the air, water, food, and products we use are destroying our health--and what we can do to fix it. HarperOne, an imprint of HarperCollins Publishers, New York, NY.

- Ferreira-Vieira, T. H., Guimaraes, I. M., Silva, F. R. & Ribeiro, F. M. (2016). Alzheimer’s disease: Targeting the Cholinergic System. Curr Neuropharmacol. 14, 101-115. [CrossRef]

- Hampel, H., Mesulam, M. M., Cuello, A. C., Farlow, M. R., Giacobini, E., Grossberg, G. T., Khachaturian, A. S., Vergallo, A., Cavedo, E., Snyder, P. J. & Khachaturian, Z. S. (2018). The cholinergic system in the pathophysiology and treatment of Alzheimer’s disease. Brain. 141, 1917-1933. [CrossRef]

- Cavedo, E., Dubois, B., Colliot, O., Lista, S., Croisile, B., Tisserand, G. L., Touchon, J., Bonafe, A., Ousset, P. J., Rouaud, O., Ricolfi, F., Vighetto, A., Pasquier, F., Galluzzi, S., Delmaire, C., Ceccaldi, M., Girard, N., Lehericy, S., Duveau, F., Chupin, M., Sarazin, M., Dormont, D., Hampel, H. & Hippocampus Study, G. (2016). Reduced Regional Cortical Thickness Rate of Change in Donepezil-Treated Subjects With Suspected Prodromal Alzheimer’s Disease. J Clin Psychiatry. 77, e1631-e1638. [CrossRef]

- Ferris, S., Nordberg, A., Soininen, H., Darreh-Shori, T. & Lane, R. (2009). Progression from mild cognitive impairment to Alzheimer’s disease: effects of sex, butyrylcholinesterase genotype, and rivastigmine treatment. Pharmacogenet Genomics. 19, 635-646. [CrossRef]

- Dubois, B., Chupin, M., Hampel, H., Lista, S., Cavedo, E., Croisile, B., Louis Tisserand, G., Touchon, J., Bonafe, A., Ousset, P. J., Ait Ameur, A., Rouaud, O., Ricolfi, F., Vighetto, A., Pasquier, F., Delmaire, C., Ceccaldi, M., Girard, N., Dufouil, C., Lehericy, S., Tonelli, I., Duveau, F., Colliot, O., Garnero, L., Sarazin, M., Dormont, D., Hippocampus Study, G. & Hippocampus Study, G. (2015). Donepezil decreases annual rate of hippocampal atrophy in suspected prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 11, 1041-1049. [CrossRef]

- Cavedo, E., Grothe, M. J., Colliot, O., Lista, S., Chupin, M., Dormont, D., Houot, M., Lehericy, S., Teipel, S., Dubois, B., Hampel, H. & Hippocampus Study, G. (2017). Reduced basal forebrain atrophy progression in a randomized Donepezil trial in prodromal Alzheimer’s disease. Sci Rep. 7, 11706. [CrossRef]

- Krishnan, K. R., Charles, H. C., Doraiswamy, P. M., Mintzer, J., Weisler, R., Yu, X., Perdomo, C., Ieni, J. R. & Rogers, S. (2003). Randomized, placebo-controlled trial of the effects of donepezil on neuronal markers and hippocampal volumes in Alzheimer’s disease. Am J Psychiatry. 160, 2003-2011. [CrossRef]

- Cuello, A. C., Bruno, M. A., Allard, S., Leon, W. & Iulita, M. F. (2010). Cholinergic involvement in Alzheimer’s disease. A link with NGF maturation and degradation. J Mol Neurosci. 40, 230-235. [CrossRef]

- Cuello, A. C., Pentz, R. & Hall, H. (2019). The Brain NGF Metabolic Pathway in Health and in Alzheimer’s Pathology. Front Neurosci. 13, 62. [CrossRef]

- Moss, D. E. (2020). Improving Anti-Neurodegenerative Benefits of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors in Alzheimer’s Disease: Are Irreversible Inhibitors the Future? Int J Mol Sci. 21. [CrossRef]

- Moss, D. E. & Perez, R. G. (2021). Anti-Neurodegenerative Benefits of Acetylcholinesterase Inhibitors in Alzheimer’s Disease: Nexus of Cholinergic and Nerve Growth Factor Dysfunction. Curr Alzheimer Res. 18, 1010-1022. [CrossRef]

- Moss, D. E. & Perez, R. G. (2024). The phospho-tau cascade, basal forebrain neurodegeneration, and dementia in Alzheimer’s disease: Anti-neurodegenerative benefits of acetylcholinesterase inhibitors. J Alzheimers Dis. 102, 617-626. [CrossRef]

- Moss, D. E. (2013). Alzheimer’s: my journey to a next generation treatment. Menlo Park, California Bear Run Publisher.

- Fraser, N. W., Lawrence, W. C., Wroblewska, Z., Gilden, D. H. & Koprowski, H. (1981). Herpes simplex type 1 DNA in human brain tissue. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 78, 6461-6465. [CrossRef]

- Jamieson, G. A., Maitland, N. J., Wilcock, G. K., Craske, J. & Itzhaki, R. F. (1991). Latent herpes simplex virus type 1 in normal and Alzheimer’s disease brains. J Med Virol. 33, 224-227. [CrossRef]

- Wu, D., Wang, C., Pang, P., Kong, H., Lin, Z., Wang, H., Chen, X., Zhao, J., Hao, Z., Zhang, T. & Guo, X. (2020). The association between herpes simplex virus type 1 infection and Alzheimer’s disease. J Clin Neurosci. 82, 63-70. [CrossRef]

- Feng, H., Pan, K., Shabani, Z. I., Wang, H. & Wei, W. (2025). Association between herpesviruses and alzheimer’s disease: a meta-analysis based on case-control studies. Mol Cell Biochem. [CrossRef]

- Burgos, J. S., Ramirez, C., Sastre, I. & Valdivieso, F. (2006). Effect of apolipoprotein E on the cerebral load of latent herpes simplex virus type 1 DNA. J Virol. 80, 5383-5387. [CrossRef]

- Itzhaki, R. F., Lin, W. R., Shang, D., Wilcock, G. K., Faragher, B. & Jamieson, G. A. (1997). Herpes simplex virus type 1 in brain and risk of Alzheimer’s disease. Lancet. 349, 241-244. [CrossRef]

- Chen, F., Ke, Q., Wei, W., Cui, L. & Wang, Y. (2023). Apolipoprotein E and viral infection: Risks and Mechanisms. Mol Ther Nucleic Acids. 33, 529-542. [CrossRef]

- Kuhlmann, I., Minihane, A. M., Huebbe, P., Nebel, A. & Rimbach, G. (2010). Apolipoprotein E genotype and hepatitis C, HIV and herpes simplex disease risk: a literature review. Lipids Health Dis. 9, 8. [CrossRef]

- Devanand, D. P., Andrews, H., Kreisl, W. C., Razlighi, Q., Gershon, A., Stern, Y., Mintz, A., Wisniewski, T., Acosta, E., Pollina, J., Katsikoumbas, M., Bell, K. L., Pelton, G. H., Deliyannides, D., Prasad, K. M. & Huey, E. D. (2020). Antiviral therapy: Valacyclovir Treatment of Alzheimer’s Disease (VALAD) Trial: protocol for a randomised, double-blind, placebo-controlled, treatment trial. BMJ Open. 10, e032112. [CrossRef]

- Vestin, E., Bostrom, G., Olsson, J., Elgh, F., Lind, L., Kilander, L., Lovheim, H. & Weidung, B. (2024). Herpes Simplex Viral Infection Doubles the Risk of Dementia in a Contemporary Cohort of Older Adults: A Prospective Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 97, 1841-1850. [CrossRef]

- Weidung, B., Hemmingsson, E. S., Olsson, J., Sundstrom, T., Blennow, K., Zetterberg, H., Ingelsson, M., Elgh, F. & Lovheim, H. (2022). VALZ-Pilot: High-dose valacyclovir treatment in patients with early-stage Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement (N Y). 8, e12264. [CrossRef]

- Feng, Y., Cao, S. Q., Shi, Y., Sun, A., Flanagan, M. E., Leverenz, J. B., Pieper, A. A., Jung, J. U., Cummings, J., Fang, E. F., Zhang, P. & Cheng, F. (2025). Human herpesvirus-associated transposable element activation in human aging brains with Alzheimer’s disease. Alzheimers Dement. 21, e14595. [CrossRef]

- Zerboni, L., Sen, N., Oliver, S. L. & Arvin, A. M. (2014). Molecular mechanisms of varicella zoster virus pathogenesis. Nat Rev Microbiol. 12, 197-210. [CrossRef]

- Lal, H., Cunningham, A. L., Godeaux, O., Chlibek, R., Diez-Domingo, J., Hwang, S. J., Levin, M. J., McElhaney, J. E., Poder, A., Puig-Barbera, J., Vesikari, T., Watanabe, D., Weckx, L., Zahaf, T., Heineman, T. C. & Group, Z. O. E. S. (2015). Efficacy of an adjuvanted herpes zoster subunit vaccine in older adults. N Engl J Med. 372, 2087-2096. [CrossRef]

- Patil, A., Goldust, M. & Wollina, U. (2022). Herpes zoster: A Review of Clinical Manifestations and Management. Viruses. 14. [CrossRef]

- Harbecke, R., Cohen, J. I. & Oxman, M. N. (2021). Herpes Zoster Vaccines. J Infect Dis. 224, S429-S442. [CrossRef]

- Cairns, D. M., Itzhaki, R. F. & Kaplan, D. L. (2022). Potential Involvement of Varicella Zoster Virus in Alzheimer’s Disease via Reactivation of Quiescent Herpes Simplex Virus Type 1. J Alzheimers Dis. 88, 1189-1200. [CrossRef]

- Warren-Gash, C., Forbes, H. & Breuer, J. (2017). Varicella and herpes zoster vaccine development: lessons learned. Expert Rev Vaccines. 16, 1191-1201. [CrossRef]

- Maple, P. A. C. & Hosseini, A. A. (2025). Human Alpha Herpesviruses Infections (HSV1, HSV2, and VZV), Alzheimer’s Disease, and the Potential Benefits of Targeted Treatment or Vaccination-A Virological Perspective. Vaccines (Basel). 13. [CrossRef]

- Husain, M. A., Laurent, B. & Plourde, M. (2021). APOE and Alzheimer’s Disease: From Lipid Transport to Physiopathology and Therapeutics. Front Neurosci. 15, 630502. [CrossRef]

- Donix, M., Small, G. W. & Bookheimer, S. Y. (2012). Family history and APOE-4 genetic risk in Alzheimer’s disease. Neuropsychol Rev. 22, 298-309. [CrossRef]

- Cannon-Albright, L. A., Foster, N. L., Schliep, K., Farnham, J. M., Teerlink, C. C., Kaddas, H., Tschanz, J., Corcoran, C. & Kauwe, J. S. K. (2019). Relative risk for Alzheimer disease based on complete family history. Neurology. 92, e1745-e1753. [CrossRef]

- Araya, K., Watson, R., Khanipov, K., Golovko, G. & Taglialatela, G. (2025). Increased risk of dementia associated with herpes simplex virus infections: Evidence from a retrospective cohort study using U.S. electronic health records. J Alzheimers Dis. 104, 393-402. [CrossRef]

- Yeh, T. S., Curhan, G. C., Yawn, B. P., Willett, W. C. & Curhan, S. G. (2024). Herpes zoster and long-term risk of subjective cognitive decline. Alzheimers Res Ther. 16, 180. [CrossRef]

- Mielke, M. M., Ransom, J. E., Mandrekar, J., Turcano, P., Savica, R. & Brown, A. W. (2022). Traumatic Brain Injury and Risk of Alzheimer’s Disease and Related Dementias in the Population. J Alzheimers Dis. 88, 1049-1059. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).