Submitted:

22 June 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

Current Study

Methodology

Participants

Theoretical Approach

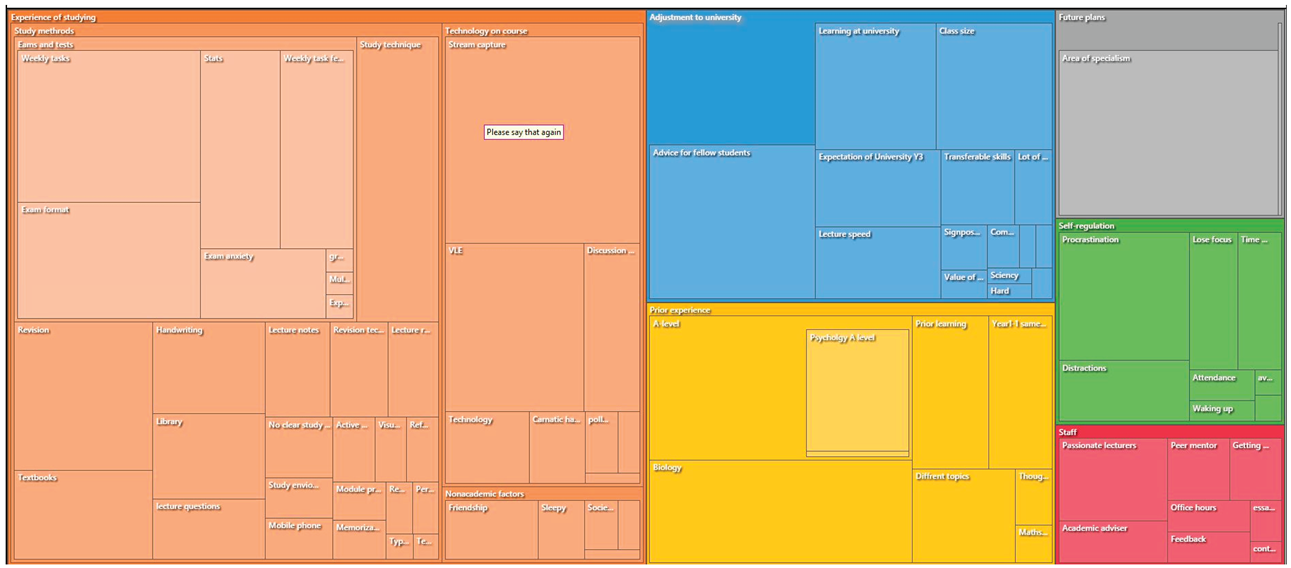

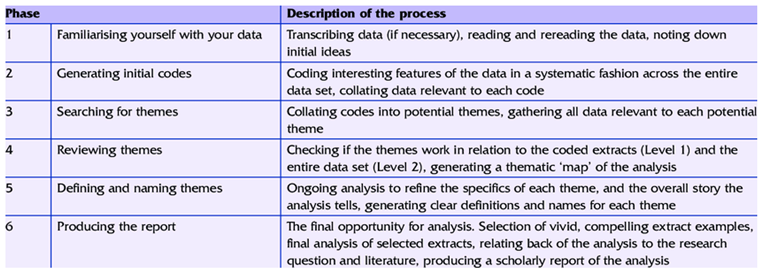

Analysis Procedure

Results and Discussion

| Theme temporality | Main theme | Sub Themes |

|---|---|---|

| Theme 1 – Before starting | Prior experience | Subject matter Student expectations |

| Theme 2 – On arrival | Adjustment to university | Learning environment Expectations vs reality |

| Theme 3 – Adjustment facilitators | Staff relationships | Teaching style and engagement Lecturer qualities |

| Theme 4 – Barriers and facilitators | Experience of university level study | Study habits Time management Technology use |

| Theme 5 – Beyond graduation | Future (career) plans | Path certainty Vocation diversity |

Prior Experience

- (Y1, focus group 1)

- “A-levels definitely help with coming into university when you’ve already had that kind of foundation of the tough exams at the end and you have to kind of manage your time studying.”

- (Y1, focus group2)

- “Doing psychology has made me, at A-level really helped me just give it like the background knowledge. It is just like a basic, like foundation but it just helps you out so much like learning it, I cannot imagine like having to learn it all from scratch at university [laughs].”.

- (Y3, focus group 1)

- “There should be a bit of a sort of a disclaimer saying you know `some of the modules are quite heavily science-based, like you don’t require the science, but it may work in your favour to have it`, maybe ‘cos then at least people are aware.”.

- (Yr. 3, focus group 3)

- “I think it’s more what you’ve learnt as well like in A-levels ‘cos you learn like how to revise and how to manage your time compared to before then ‘cos you have a bit freer time, so I think that’s probably more useful”.

- (Y3, focus group 2)

- “Just like the essay-writing and the problem-solving skills … you came to Uni with them. So, as you came to like more equipped going through like things like problems and stuff like on the course.”.

Adjustment to University

- (Y3, focus group 1)

- “…look, I mean you can’t ‘cos there’s such a big year group I don’t know my lecturers, like I know my supervisor and my tutor, but I don’t think, I could probably walk past any of them, and they’d have no idea who I was.”.

- (Y1, focus group 5)

- “Seminars to me were daunting let alone lectures because I came from a Sixth Form where my biggest class had like seven people in it so than having suddenly having thirty people, I was like whoa this is a lot of people so I feel like I can’t speak up so then, never mind the lecture where there’s four hundred of us sat in the same room.”.

- (Y1, focus group 5)

- “…they were like very fast-paced, like I was just sat there, and I couldn’t keep up with all the content and them speaking so fast and it was just a bit overwhelming I think.” … “didn’t realise that lectures would be two hours long, ... after about half an hour my teacher had to give me a break …so being sat down for like two hours straight, after like the first half an hour, I lose focus”.

Staff Connections

- (Y3, focus group 3)

- “They’ve got such a fountain of knowledge from them that it’s just so good that you’ve got that as an ongoing resource, they’re in the building somewhere, you can go find them, they will help you, most of them will be completely happy to help you and just sit down and listen to your questions.”.

- (Y1, focus group 1)

- “Brain and Cognition is my favourite, just ‘cos errs, I was already interested in it, but the enthusiasm of the lecturer, or he wasn’t like fully enthusiastic but his, you could tell he really enjoyed it, so it sort of rubbed off on me.”.

- (Y1, focus group 4)

- “I find that some of the lecturers are quite engaging though as well like you can kind of, they’ll put in some of their own quirky jokes and stuff which I quite like cos I was quite worried that it was going to be like really mundane lectures sort of really kind of tight lecturers but actually they’re a lot more engaging and you can tell that they’re really passionate about their subject field as well.”.

- (Y3, focus group 3)

- “I think definitely one of the things we miss out on being such a massive course is having like that closer relationship with members of staff. You know when you’ve come from school and in A-levels you’re in like classes of 15 and you have really close relationships with your teachers. … So, I think that’s definitely one of the things I’ve found most helpful, but it is one of the things that you miss out on in the course because it so massive.”.

- (Y3, focus group 2)

- “From the initial [meeting with your supervisor] that makes you like not just a face in the crowd. Like, if you did that in first years like you’d know your lecturers. Like, only meeting them in this year and stuff is like great but it’s one of them things where you wish you’d have known them for first year ‘cos they’d have been of such help.”.

The Experience of Studying

- (Y1, focus group 5)

- “I still haven’t found something that’s worked for me, like I didn’t find it in A-Level and I’m still trying out different methods for me. I think the only one that came close to slightly working was having visuals so like something colourful to look at.”.

- (Y3, focus group 1)

- “It took me ages to try and work out the best way to actually take notes just in lectures and stuff, like I just spent like so long not, like just trying to figure out the most like efficient way to do it … I was like this is so difficult … kind of made like my own versions”.

- (Y1, focus group 1)

- “I procrastinate a lot …, it’s just sort of trying to motivate yourself to do it quickly, I often start things and then I’m like I’ll come back to that later and then I leave it really the last minute”.

- (Y1, focus group 4)

- “I made study timetables, but I didn’t have the self-control to stick to them. I think I tried every method possible; I tried working with somebody, I tried rewarding myself and it just never worked for me, I think I always kind of procrastinated and I work best under stress, that is when I do all”.

- (Y1, focus group 5)

- “It’s also getting distracted especially, I think I just need to work in the library because when I work back at the accommodation like I normally didn’t have my phone on me like at A-Levels I didn’t, but now it’ll be next to me and someone will be like “Oh do you want to meet up?” or “I’m doing washing, do you want to come down?” And I’ll be like, “Oh yeah” and then I’ll just leave it and then I eat tea and then I’ll just be like “Oh I’ll do it all tomorrow” and it’s just something that I shouldn’t do.”.

- (Y1, focus group 1)

- “It’s definitely a useful resource regardless of whether you do make use of it or not because especially if, erm it might not necessarily be because you haven’t understood the lecture and you feel like going over it again, if you are like ill, or for whatever reason you cannot make it.”.

- (Y1, focus group 4)

- “[I have a] hearing impairment and things like that so from an accessibility point of view, I feel it is quite essential at times to have it even if the majority of people don’t necessarily use it”.

- (Y1, focus group 5)

- “…because I’m the only one listening to it, I can pause it when I need to, like I can slow it down to my pace to make the notes when I want, like if I’ve heard a certain part, I’ll pause it, make notes on it, replay that part to make sure I’ve got everything then move onto the next part.”.

- (Y1, focus group 1)

- “[The VLE platform] makes it really easy to do work at whatever time you have, so erm, like there was a certain bit of reading that we had to do that was available on Blackboard so it was really easy when you have a spare hour to like make the most of that and you can be in your room doing that as opposed to having to go to the library, find the book, find the right bit”.

- (Y3, focus group 2)

- “Although not all lecturers replied efficiently, I thought it was really useful ‘cos obviously everything was all in one place … the discussion boards were good,” (Y3, focus group 1). … “. there are some things you wouldn’t have thought of and then someone’s asked a question on it, and you get the answer and you're like, oh!”.

Future Plans

- (Y1, focus group 3)

- “I think I want to… but my main goal is to become a clinical psychologist, but we don’t have that module until next year.”.

- (Y1, focus group 4)

- “… I think it’s definitely open yeah, I’m not completely set in what I want to do yet, I’m not completely sure … over the next three years that I’ll get different tastes of different parts of Psychology and feel that maybe I might find something completely new that I might be more interested in … so I’ve got three years to decide.”.

- (Y3, focus group 3)

- “I just had so many misconceptions of what it actually entailed, and I think people think like it’s forensic psychology like massively glamorised and I actually don’t, don’t really know what it is until you, and I think what people think they want to do is like clinical psychology in a forensic setting rather than actual forensic psychology.”.

Limitations

Conclusion

Acknowledgements

Appendix A

References

- Anderson, B.; Marshall-Lucette, S.; Webb, P. African and Afro-Caribbean men's experiences of prostate cancer. Br. J. Nurs. 2013, 22, 1296–1307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balloo, K. In-depth profiles of the expectations of undergraduate students commencing university: a Q methodological analysis. Stud. High. Educ. 2017, 43, 2251–2262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandura, A.; Wessels, S. (1994). Self-efficacy (Vol.4, pp. 71-81). New York, NY: Academic Press.

- Bolam, H.; Dodgson, R. Retaining and Supporting Mature Students in Higher Education. J. Adult Contin. Educ. 2003, 8, 179–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Astudillo, L.R.; Niaz, M. Reasoning strategies used by students to solve stoichiometry problems and its relationship to alternative conceptions, prior knowledge, and cognitive variables. J. Sci. Educ. Technol. 1996, 5, 131–140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Braun, V.; Clarke, V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology 2006, 3, 77–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Briggs, S. An exploratory study of the factors influencing undergraduate student choice: the case of higher education in Scotland. Stud. High. Educ. 2006, 31, 705–722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Broadbent, J. Comparing online and blended learner's self-regulated learning strategies and academic performance. Internet High. Educ. 2017, 33, 24–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.; Leckey, J. Do Expectations Meet Reality? A survey of changes in first-year student opinion. J. Furth. High. Educ. 1999, 23, 157–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cook, A.; Rushton, B.S.; McCormick, S.M.; Southall, D.W. Guidelines for the management of student transition. University of Ulster, Coleraine. 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Crisp, G.; Palmer, E.; Turnbull, D.; Nettelbeck, T.; Ward, L.; LeCouteur, A.; Sarris, A.; Strelan, P.; Schneider, L. First year student expectations: Results from a university-wide student survey. J. Univ. Teach. Learn. Pr. 2009, 6, 16–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, F. "Free in Time, Not Free in Mind": First-Year University Students Becoming More Independent. J. Coll. Stud. Dev. 2017, 58, 601–617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Drew, S. Perceptions of what helps learn and develop in education. Teaching In Higher Education 2001, 6, 309–331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ecochard, S.; Fotheringham, J. International Students’ Unique Challenges – Why Understanding International Transitions to Higher Education Matters. J. Perspect. Appl. Acad. Pr. 2017, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- English, T.; Davis, J.; Wei, M.; Gross, J.J. Homesickness and adjustment across the first year of college: A longitudinal study. Emotion 2017, 17, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gall, T.L.; Evans, D.R.; Bellerose, S. Transition to First-Year University: Patterns of Change in Adjustment Across Life Domains and Time. J. Soc. Clin. Psychol. 2000, 19, 544–567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guilmette, M.; Mulvihill, K.; Villemaire-Krajden, R.; Barker, E.T. Past and present participation in extracurricular activities is associated with adaptive self-regulation of goals, academic success, and emotional wellbeing among university students. Learn. Individ. Differ. 2019, 73, 8–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadwin, A. F. , Winne, P. H., Stockley, D. B., Nesbit, J. C., & Woszczyna, C. (2001). Context moderates’ students' self-reports about how they study. Journal of Educational Psychology, 93(3), 477.

- Hands, C. & Limniou, M. (2023). How does student access to a virtual learning environment (VLE) change during periods of disruption? Journal of Higher Education Theory and Practice, 23(2), 18-34.

- Hands, C. & Limniou, M. (2023). Why science qualifications should be a pre-requisite for a Psychology degree programmes – a case study analysis from a UK (United Kingdom) university. Chapter 3, High Impact Practices in Higher Education: International Perspectives. Emerald Publishing.

- Hassel, S.; Ridout, N. An Investigation of First-Year Students' and Lecturers' Expectations of University Education. Front. Psychol. 2018, 8, 2218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holton, M. Adapting relationships with place: Investigating the evolving place attachment and ‘sense of place’ of UK higher education students during a period of intense transition. Geoforum 2015, 59, 21–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jackson, C. Transitions into Higher Education: Gendered implications for academic self-concept. Oxf. Rev. Educ. 2003, 29, 331–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaremka, L.M.; Ackerman, J.M.; Gawronski, B.; Rule, N.O.; Sweeny, K.; Tropp, L.R.; Metz, M.A.; Molina, L.; Ryan, W.S.; Vick, S.B. Common Academic Experiences No One Talks About: Repeated Rejection, Impostor Syndrome, and Burnout. Perspect. Psychol. Sci. 2020, 15, 519–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffman, M.J.; McKenzie, K.S.; Paris, S. Paper or plastic? The CPA Journal 2008, 78, 16. [Google Scholar]

- Karimi-Haghighi, M.; Castillo, C.; Hernández-Leo, D. (2022, July). A causal inference study on the effects of first year workload on the dropout rate of undergraduates. Inartificial Intelligence in Education: 23rd International Conference, AIED (Artificial intelligence in education) 2022, Durham, UK, July 27–31, 2022, Proceedings, Part I (pp. 15–27). Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Kilpatrick, S.; Johns, S.; Barnes, R.; Fischer, S.; McLennan, D.; Magnussen, K. Exploring the retention and success of students with disability in Australian higher education. Int. J. Incl. Educ. 2016, 21, 747–762. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- King, A.E.; McQuarrie, F.A.; Brigham, S.M. Exploring the Relationship Between Student Success and Participation in Extracurricular Activities. Sch. A J. Leis. Stud. Recreat. Educ. 2020, 36, 42–58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitching, H.J.; Hulme, J. Bridging the gap: Facilitating students’ transition from pre–tertiary to university psychology education. Psychol. Teach. Rev. 2013, 19, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzinger, J. The methodology of Focus Groups: the importance of interaction between research participants. Sociol. Heal. Illn. 1994, 16, 103–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kitzinger, J.; Farquhar, C. The analytical potential of ‘sensitive moments’ in focus group discussions. Developing focus group research: Politics, theory, and practice 1999, 156–172. [Google Scholar]

- Krispenz, A.; Gort, C.; Schültke, L.; Dickhäuser, O. How to Reduce Test Anxiety and Academic Procrastination Through Inquiry of Cognitive Appraisals: A Pilot Study Investigating the Role of Academic Self-Efficacy. Front. Psychol. 2019, 10, 1917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kuh, G.D.; Cruce, T.M.; Shoup, R.; Kinzie, J.; Gonyea, R.M. Unmasking the Effects of Student Engagement on First-Year College Grades and Persistence. J. High. Educ. 2008, 79, 540–563. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Limniou, M.; Duret, D.; Hands, C. Comparisons between three disciplines regarding device usage in a lecture theatre, academic performance and learning. High. Educ. Pedagog. 2020, 5, 132–147. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lischer, S.; Safi, N.; Dickson, C. Remote learning and students’ mental health during the Covid-19 pandemic: A mixed-method enquiry. PROSPECTS 2021, 51, 589–599. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liverpool, S.; Moinuddin, M.; Aithal, S.; Owen, M.; Bracegirdle, K.; Caravotta, M.; Walker, R.; Murphy, C.; Karkou, V.; Lin, C.-Y. Mental health and wellbeing of further and higher education students returning to face-to-face learning after Covid-19 restrictions. PLOS ONE 2023, 18, e0280689. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, A.J.; Ginns, P.; Papworth, B. Motivation and engagement: Same or different? Does it matter? Learning and Individual Differences 2017, 55, 150–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maunder, R.E. Students’ peer relationships and their contribution to university adjustment: the need to belong in the university community. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2017, 42, 756–768. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McInnis, C.; James., R.; Hartley, R. Trends in the first-year experience in Australian Universities. 2000. Available online: http://melbourne cshe.unimelb.edu.au/research/experience/trends-in-the-first year-experience (accessed on 6 July 2016).

- Menzies, J.; Baron, R. International postgraduate student transition experiences: the importance of student societies and friends. Innov. Educ. Teach. Int. 2013, 51, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Money, J.; Nixon, S.; Tracy, F.; Hennessy, C.; Ball, E.; Dinning, T. Undergraduate student expectations of university in the United Kingdom: What really matters to them? Cogent Education 2017, 4, 1301855. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morgan, D. L. (1996). Focus groups as qualitative research (vol. 16). Sage Publications.

- Nadelson, L.S.; Semmelroth, C.; Martinez, G.; Featherstone, M.; Fuhriman, C.A.; Sell, A. Why Did They Come Here? –The Influences and Expectations of First-Year Students’ College Experience. High. Educ. Stud. 2013, 3, p50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nordmann, E.; Calder, C.; Bishop, P.; Irwin, A.; Comber, D. Turn up, tune in, don't drop out: The relationship between lecture attendance, use of lecture recordings, and achievement at different levels of study. Higher Education 2019, 77, 1065–1084. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Panopto. (2018, April 19). Using lecture recording and video to enhance the international student experience. https://www.panopto.com/blog/using-lecture-recording-and video-to-enhance-the-international-student-experience/.

- Pithers, R, & Holland, A. (2006). Student expectations and the effect of experience. Paper presented at the Australian Association for Research in Education Annual Conference, Adelaide, Australia, November 26–30.

- Pownall, M.; Blundell-Birtill, P.; Coats, R.O.; Harris, R. Pre-tertiary subject choice as predictors of undergraduate attainment and academic preparedness in Psychology. Psychol. Teach. Rev. 2021, 27, 9–25. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, M.; Abraham, C.; Bond, R. Psychological correlates of university students' academic performance: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychol. Bull. 2012, 138, 353–387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Risquez, A.; Moore, S.; Morley, M. Welcome to College? Developing a Richer Understanding of the Transition Process for Adult First Year Students Using Reflective Written Journals. J. Coll. Stud. Retention: Res. Theory Pr. 2007, 9, 183–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaeper, H. The first year in higher education: the role of individual factors and the learning environment for academic integration. High. Educ. 2019, 79, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Short, F.; Martin, J. Presentation vs. Performance: Effects of lecturing style in Higher Education on Student preference and Student Teaching Review. 2011; 17, 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, J.S.; Wertlieb, E.C. Do first-year college students’ expectations align with their first-year experiences? NASPA Journal 2005, 42. Available online: http://publications.naspa.org/naspajournal/vol42/iss2/art2. [CrossRef]

- Timmis, M.A.; Hibbs, A.; Polman, R.; Hayman, R.; Stephens, D. Previous education experience impacts student expectation and initial experience of transitioning into higher education. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1479546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tomlinson, A.; Simpson, A.; Killingback, C. Student expectations of teaching and learning when starting university: a systematic review. J. Furth. High. Educ. 2023, 47, 1054–1073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Voss, R.; Gruber, T.; Szmigin, I. Service quality in higher education: The role of student expectations. J. Bus. Res. 2007, 60, 949–959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Williamson, M.; Laybourn, P.; Deane, J.; Tait, H. Closing the Gap: An Exploration of First-Year Students' Expectations and Experiences of Learning. Psychol. Learn. Teach. 2011, 10, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zimmerman, B.J. Self-Efficacy: An Essential Motive to Learn. Contemp. Educ. Psychol. 2000, 25, 82–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Number of students | ||

|---|---|---|

| Gender | Female | 43 |

| Male | 3 | |

| Disability | Able bodied | 39 |

| Listed disability | 7 | |

| Student type | UK (Home) student | 44 |

| European | 1 | |

| International | 1 | |

| Total | 46 |

| Number of students | ||

|---|---|---|

| Academic Performance | 1st Class | 4 |

| 2:1 | 35 | |

| 2:2 | 5 | |

| 3rd Class | 1 | |

| Did not complete degree | 1 | |

| Total | 46 |

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).