Submitted:

04 July 2025

Posted:

07 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

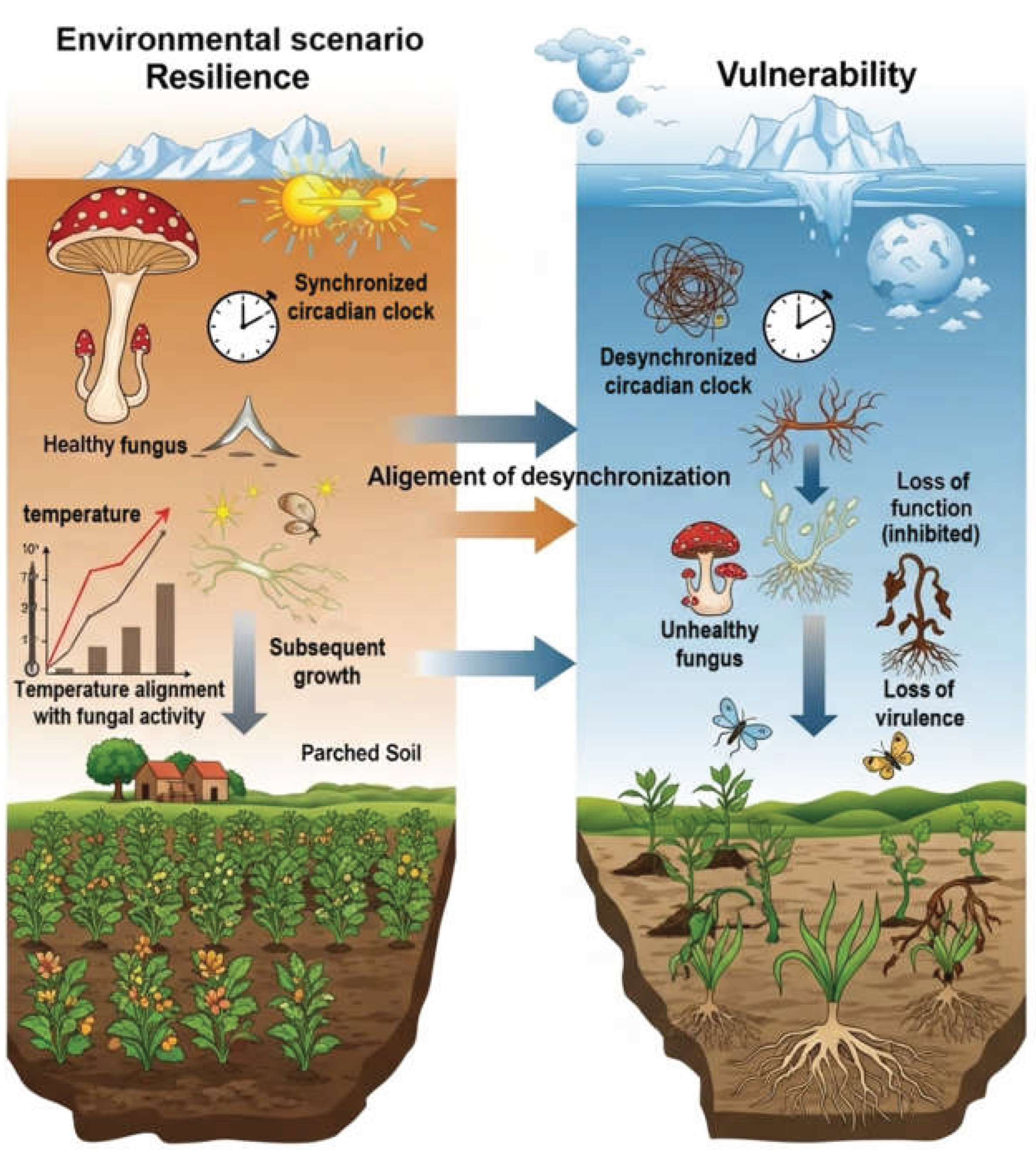

1. Introduction: The Fungal Clock as a Proactive Survival Mechanism

2. The Core Oscillator: A Conserved Engine with Species-Specific Adaptations

2.1. The Neurospora crassa Paradigm: The FRQ-WCC Oscillator

- ● Positive Arm: The primary positive-acting component is the White Collar Complex (WCC), a heterodimer of two GATA-type zinc-finger transcription factors, WHITE COLLAR-1 (WC-1) and WHITE COLLAR-2 (WC-2) [8]. WC-1 contains a Light-Oxygen-Voltage (LOV) domain, which functions as a blue-light photoreceptor, directly linking the clock to its most dominant environmental cue [8]. The WCC binds to specific promoter elements (Clock boxes or C-boxes) in its target genes to activate their transcription [9].

- ● Negative Arm: The masterstroke of the oscillator is that the WCC drives the transcription of its own inhibitor, the frequency (frq) gene [8]. The FRQ protein, upon translation in the cytoplasm, forms a complex with the FRQ-interacting RNA helicase (FRH) and casein kinases [3]. This complex then enters the nucleus and physically interacts with the WCC, repressing its transcriptional activity and thereby shutting down its own expression [8].

- ● Setting the Pace: The ~24-hour periodicity of the clock is not determined by the simple on/off switch but by a crucial delay mechanism. FRQ undergoes progressive, time-dependent phosphorylation by several kinases. This series of phosphorylation events governs its stability and its ability to inhibit the WCC. Once FRQ becomes hyperphosphorylated, it is targeted for degradation, which releases the WCC from inhibition and allows a new cycle of frq transcription to begin [3]. This elegant, phosphorylation-based time delay is the key to generating a robust, near-24-hour rhythm.

2.2. The Neurospora crassa Paradigm: The FRQ-WCC Oscillator

- ● Filamentous Ascomycetes: The FRQ-WCC system is remarkably well-conserved among many filamentous ascomycetes, particularly those with lifestyles exposed to daily environmental cycles. Crucially, this includes major plant pathogens. In Botrytis cinerea, the gray mold fungus, a functional clock with clear homologs of frq, wc-1, and wc-2 is essential for regulating virulence [10]. Similarly, the vascular wilt pathogen Fusarium oxysporum possesses multiple frq homologs and a WCC that are indispensable for its pathogenicity [11]. The conservation of this light-responsive clock in these pathogens underscores its fundamental importance for coordinating their infectious cycle with the external environment and the physiology of their plant hosts.

- ● The Enigma of the Yeast Clock: In stark contrast, the budding yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae, a powerhouse of genetic research, lacks an obvious homolog of the core negative element frq [12]. For many years, this led to the assumption that yeast lacked a true circadian clock. However, pioneering work using continuous cultures (chemostats) revealed that yeast populations exhibit robust, temperature-compensated metabolic oscillations, notably in oxygen consumption, known as Yeast Respiratory Oscillations (YROs) [13]. These rhythms can be entrained by temperature cycles but damp out quickly in constant conditions, suggesting a less self-sustained oscillator compared to the Neurospora model [13]. This points to the existence of a non-canonical, FRQ-independent timekeeping mechanism in yeast, likely rooted in metabolic feedback loops rather than a dedicated TTFL. This architecture is well-suited to its typical fermentative lifestyle, where sporadic nutrient availability is a more pressing rhythmic challenge than light.

- ● Emerging Clocks in Symbionts: Perhaps the most intriguing recent discovery is the presence of the complete FRQ-WCC gene set in arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi (AMF), such as Rhizoglomus irregulare [14]. These fungi are obligate symbionts that live in the relatively dark and stable soil environment, forming intimate connections with plant roots. The presence of a "light-responsive" clock machinery in a non-photosynthetic, subterranean organism seems paradoxical. However, this strongly suggests that the clock is not entrained by light but by rhythmic signals from the host plant, namely the daily flux of photosynthates and other metabolites. The AMF clock likely serves to coordinate its metabolic activity—absorbing nutrients from the soil and exchanging them for carbon from the plant—with the host's own robust circadian rhythm, ensuring maximal efficiency for the symbiosis [15].

2.3. Entrainment: Synchronizing with the External World

- ● Light: As the most reliable environmental signal of the day-night cycle, light is the dominant entrainment cue for most surface-dwelling fungi. In the Neurospora model, the WCC's function as a direct blue-light photoreceptor provides an elegant mechanism for entrainment. A pulse of light rapidly induces frq transcription, and the effect on the clock's phase depends on when the pulse is received: a light pulse in the subjective evening delays the clock, while one in the late subjective night advances it, effectively aligning the internal rhythm with the external light cycle [2].

- ● Temperature: Temperature is another critical zeitgeber. Fungal clocks exhibit temperature compensation, a hallmark property of circadian systems, meaning the period of the rhythm remains relatively constant across a range of physiological temperatures [16]. This prevents the clock from running faster on warm days and slower on cool days, which would render it useless as a timekeeper. However, the clock is still sensitive to changes in temperature. Temperature cycles can entrain the rhythm, a feature that is likely crucial for subterranean or other fungi where light cues are weak or absent [17]. The molecular mechanisms for temperature compensation are complex but are thought to involve temperature-dependent changes in protein translation and localization that counterbalance each other to maintain a stable period [16]. Table 1 provides a comparative overview of the core clock machinery, highlighting the conserved paradigm and key evolutionary divergences that reflect niche-specific adaptations.

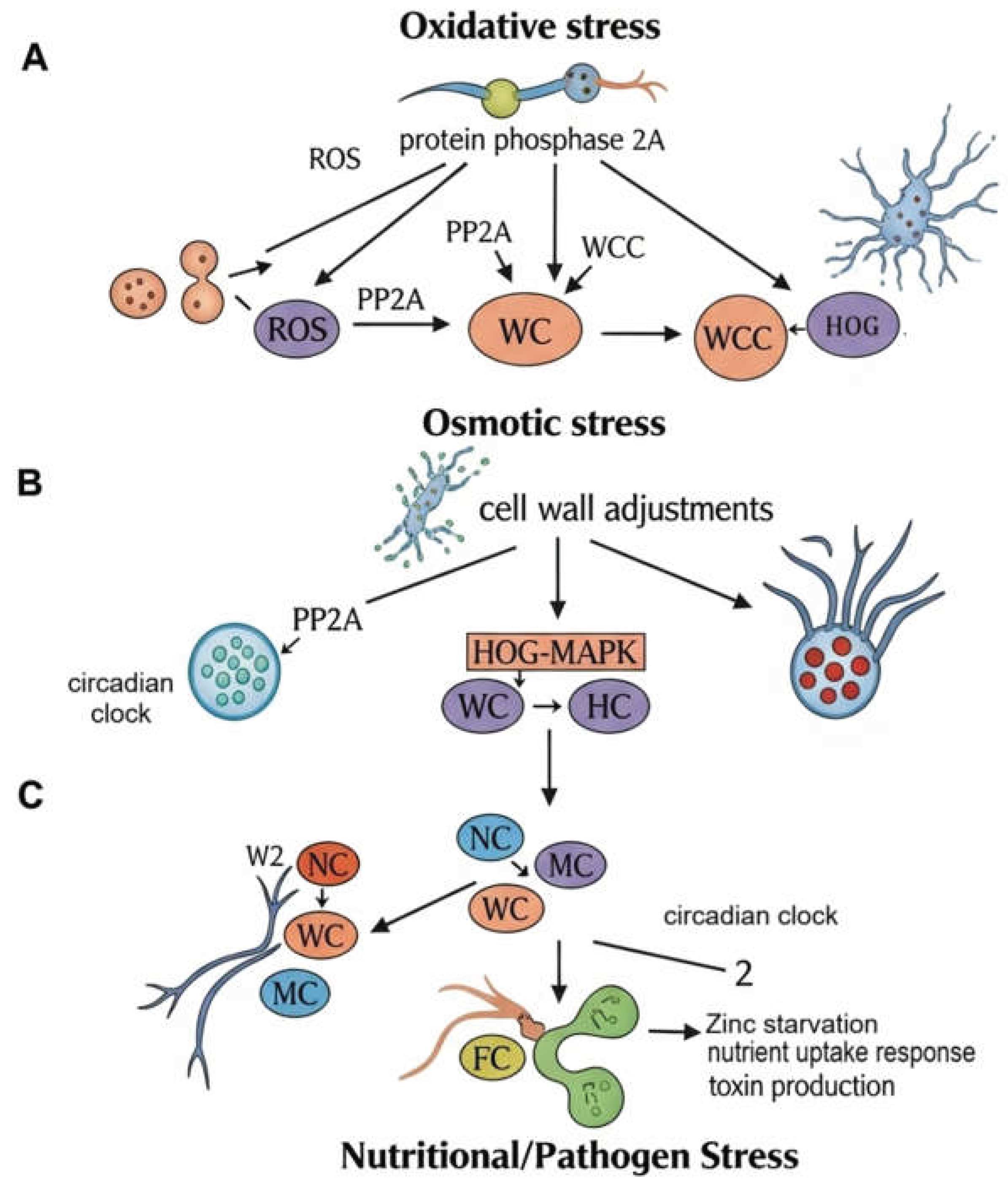

3. Circadian Gating of Cellular Defense: Preparing for the Inevitable

3.1. Anticipating Oxidative Threats

3.2. Managing Osmotic and Desiccation Stress

3.3. Adapting to Nutritional Fluctuations

3.4. Responding to Chemical Stress

4. The Chrono-Pathogenesis of Fungal Infections

4.1. A Timed Attack: Coordinating Virulence with Host Vulnerability

4.2. Case Study: Botrytis cinerea on Arabidopsis thaliana

4.3. Case Study: Fusarium oxysporum on Tomato

- ● Overcoming Zinc Starvation: During infection, plants actively sequester essential micronutrients like zinc to starve the invading pathogen. The Fusarium clock anticipates this defense by rhythmically driving the expression of the transcription factor FoZafA. FoZafA is essential for the fungus to adapt to the zinc-limited environment within the host plant, and its timed expression ensures this adaptation is active when needed most [11].

- ● Deploying Chemical Weapons: The clock also controls the production of phytotoxins. It rhythmically regulates the transcription factor FoCzf1, which governs the entire biosynthetic gene cluster for fusaric acid, a potent toxin that contributes to wilt symptoms. By timing the production of this chemical weapon, the fungus can deploy it for maximal impact [11].

4.4. The Host-Pathogen Temporal Dialogue

5. Molecular Output Pathways: From Oscillation to Action

5.1. Transcriptional Cascades: The WCC as a Master Regulator

5.2. Post-Translational Rhythms: Modulating Protein Activity

5.3. Chromatin and Epigenetic Regulation

6. Discussion

- Comparative Genomics and Transcriptomics: Applying long-read sequencing and time-series RNA-seq to a much broader phylogenetic diversity of fungi, particularly within Basidiomycota and early-diverging lineages, will be crucial for identifying novel clock components and uncovering new clock architectures.

- Chrono-Proteomics and -Metabolomics: The use of high-resolution mass spectrometry to perform time-series analyses of the entire proteome, phosphoproteome (to identify rhythmic kinase activity), and metabolome of fungi grown in constant conditions will be essential for mapping the full extent of the clock's output pathways.

- Structural Biology: Determining the high-resolution 3D structures of key clock protein complexes, such as the WCC and the FRQ-FRH complex, using techniques like cryo-electron microscopy. This will provide deep mechanistic insights into their function and reveal potential pockets for the rational design of small-molecule inhibitors ("chrono-fungicides").

- In Vivo Infection Models: Developing and employing advanced imaging techniques, such as live-cell microscopy with dual-reporter systems (e.g., fluorescent reporters for both fungal clock phase and host immune gene activation). This will allow researchers to dissect the temporal dynamics of the host-pathogen interaction in real-time and to precisely determine the contribution of each partner's clock to the outcome of the infection.

7. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| FRQ | FREQUENCY |

| WCC | WHITE COLLAR COMPLEX |

| TTFL | Transcription-Translation Feedback Loop |

| ROS | Reactive Oxygen Species |

| YROs | Yeast Respiratory Oscillations |

| AMF | Arbuscular Mycorrhizal Fungi |

| MAPK | Mitogen-Activated Protein Kinase |

| PP2A | Protein Phosphatase 2A |

| eEF-2 | Eukaryotic Elongation Factor 2 |

| ccg | Clock-Controlled Genes |

| NTOs | Non-Transcriptional Oscillators |

| GCN2 | General Control Nonderepressible 2 |

| CPC-1 | Cross-Pathway Control 1 |

| SAGA | Spt-Ada-Gcn5 Acetyltransferase (complex) |

References

- Konakchieva, R.; Mladenov, M.; Konaktchieva, M.; Sazdova, I.; Gagov, H.; Nikolaev, G. Circadian Clock Deregulation and Metabolic Reprogramming: A System Biology Approach to Tissue-Specific Redox Signaling and Disease Development. International Journal of Molecular Sciences 2025, 26, 6267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bell-Pedersen, D.; Garceau, N.; Loros, J. Circadian Rhythms in Fungi. Journal of Genetics 1996, 75, 387–401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurley, J.M.; Dasgupta, A.; Emerson, J.M.; Zhou, X.; Ringelberg, C.S.; Knabe, N.; Lipzen, A.M.; Lindquist, E.A.; Daum, C.G.; Barry, K.W.; et al. Analysis of Clock-Regulated Genes in Neurospora Reveals Widespread Posttranscriptional Control of Metabolic Potential. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2014, 111, 16995–17002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaffai, R.; Ganesan, M.; Cherif, A. Mechanisms of Plant Response to Heat Stress: Recent Insights. In Plant Adaptation to Abiotic Stress: From Signaling Pathways and Microbiomes to Molecular Mechanisms; Chaffai, R., Ganesan, M., Cherif, A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Singapore, 2024; pp. 83–105 ISBN 978-981-97-0672-3.

- Ullah, F.; Ali, S.; Siraj, M.; Akhtar, M.S.; Zaman, W. Plant Microbiomes Alleviate Abiotic Stress-Associated Damage in Crops and Enhance Climate-Resilient Agriculture. Plants 2025, 14, 1890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shchaslyvyi, A.Y.; Antonenko, S.V.; Telegeev, G.D. Comprehensive Review of Chronic Stress Pathways and the Efficacy of Behavioral Stress Reduction Programs (BSRPs) in Managing Diseases. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2024, 21, 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shelake, R.M.; Wagh, S.G.; Patil, A.M.; Červený, J.; Waghunde, R.R.; Kim, J.-Y. Heat Stress and Plant–Biotic Interactions: Advances and Perspectives. Plants 2024, 13, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dunlap, J.C.; Loros, J.J. Making Time: Conservation of Biological Clocks from Fungi to Animals. Microbiology Spectrum 2017, 5, 10.1128/microbiolspec.funk-0039–2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Zhang, J.; Shen, Q.; Yu, Z. Fungi Employ the GCN2 Pathway to Maintain the Circadian Clock under Amino Acid Starvation. TIL 2023, 1, 100026–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hevia, M.A.; Canessa, P.; Müller-Esparza, H.; Larrondo, L.F. A Circadian Oscillator in the Fungus Botrytis Cinerea Regulates Virulence When Infecting Arabidopsis Thaliana. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2015, 112, 8744–8749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, Q.; Yu, M.; Sun, X.; Zhou, X.; Zhang, R.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, X.-L.; Li, Z.; Cai, L.; Liu, H.; et al. Circadian Clock Is Critical for Fungal Pathogenesis by Regulating Zinc Starvation Response and Secondary Metabolism. Sci Adv 11, eads1341. [CrossRef]

- Merrow, M.; and Raven, M. Finding Time: A Daily Clock in Yeast. Cell Cycle 2010, 9, 1671–1672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eelderink-Chen, Z.; Mazzotta, G.; Sturre, M.; Bosman, J.; Roenneberg, T.; Merrow, M. A Circadian Clock in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2010, 107, 2043–2047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, N.M.L.; Dodd, A.N. A New Link between Plant Metabolism and Circadian Rhythms? Plant, Cell & Environment 2017, 40, 995–996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.-J.; Morse, D.; Hijri, M. Holobiont Chronobiology: Mycorrhiza May Be a Key to Linking Aboveground and Underground Rhythms. Mycorrhiza 2019, 29, 403–412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tseng, Y.-Y.; Hunt, S.M.; Heintzen, C.; Crosthwaite, S.K.; Schwartz, J.-M. Comprehensive Modelling of the Neurospora Circadian Clock and Its Temperature Compensation. PLOS Computational Biology 2012, 8, e1002437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sulzman, F.M.; Ellman, D.; Fuller, C.A.; Moore-Ede, M.C.; Wassmer, G. Neurospora Circadian Rhythms in Space: A Reexamination of the Endogenous-Exogenous Question. Science 1984, 225, 232–234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Baker, C.L.; Loros, J.J.; Dunlap, J.C. The Circadian Clock of Neurospora Crassa. FEMS Microbiol Rev 2012, 36, 95–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilking, M.; Ndiaye, M.; Mukhtar, H.; Ahmad, N. Circadian Rhythm Connections to Oxidative Stress: Implications for Human Health. Antioxid Redox Signal 2013, 19, 192–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, Y.; Iigusa, H.; Wang, N.; Hasunuma, K. Cross-Talk between the Cellular Redox State and the Circadian System in Neurospora. PLOS ONE 2011, 6, e28227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamb, T.M.; Finch, K.E.; Bell-Pedersen, D. The Neurospora Crassa OS MAPK Pathway-Activated Transcription Factor ASL-1 Contributes to Circadian Rhythms in Pathway Responsive Clock-Controlled Genes. Fungal Genet Biol 2012, 49, 180–188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, R.; Morales, P.; Tronchoni, J.; Cordero-Bueso, G.; Vaudano, E.; Quirós, M.; Novo, M.; Torres-Pérez, R.; Valero, E. New Genes Involved in Osmotic Stress Tolerance in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae. Front. Microbiol. 2016, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rep, M.; Reiser, V.; Gartner, U.; Thevelein, J.M.; Hohmann, S.; Ammerer, G.; Ruis, H. Osmotic Stress-Induced Gene Expression in Saccharomyces Cerevisiae Requires Msn1p and the Novel Nuclear Factor Hot1p. Mol Cell Biol 1999, 19, 5474–5485. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitalini, M.; De Paula, R.; Goldsmith, C.; Jones, C.; Borkovich, K.; Bell-Pedersen, D. Circadian Rhythmicity Mediated by Temporal Regulation of the Activity of P38 MAPK. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America 2007, 104, 18223–18228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, J.-M.; Zhang, D.-D.; Huang, Z.-Y.; Fu, M.-J. The Stress of Fungicides Changes the Expression of Clock Protein CmFRQ and the Morphology of Fruiting Bodies of Cordyceps Militaris. Journal of Fungi 2024, 10, 150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costantini, C.; Renga, G.; Sellitto, F.; Borghi, M.; Stincardini, C.; Pariano, M.; Zelante, T.; Chiarotti, F.; Bartoli, A.; Mosci, P.; et al. Microbes in the Era of Circadian Medicine. Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2020, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caster, S.Z.; Castillo, K.; Sachs, M.S.; Bell-Pedersen, D. Circadian Clock Regulation of mRNA Translation through Eukaryotic Elongation Factor eEF-2. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 2016, 113, 9605–9610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Valim, H.F.; Dal Grande, F.; Otte, J.; Singh, G.; Merges, D.; Schmitt, I. Identification and Expression of Functionally Conserved Circadian Clock Genes in Lichen-Forming Fungi. Sci Rep 2022, 12, 15884. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kalangutkar, J.; Kamat, N. Some Studies on Circadian Rhythm in the Culture of Omphalina Quelet Sp. (Basidiomycota, Agaricales) A Mycobiont of an Unidentified Basidiolichen. Nat Prec 2010, 1–1. [CrossRef]

- Causton, H.C.; Feeney, K.A.; Ziegler, C.A.; O’Neill, J.S. Metabolic Cycles in Yeast Share Features Conserved among Circadian Rhythms. Curr Biol 2015, 25, 1056–1062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mycorrhizal symbioses. Available online: https://www.periodicos.capes.gov.br/index.php/acervo/buscador.html?task=detalhes&id=W4246537531 (accessed on 1 July 2025).

| Fungus | WC-1/WC-2 Homologs (Presence/Function) | FRQ Homolog(s) (Presence/Function) | Primary Entrainment Cue(s) | Key Rhythmic Output |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Neurospora crassa | Present / Positive element, photoreceptor [8] | Present / Negative element [8] | Light, Temperature [8] | Asexual sporulation (conidiation), Stress response [18] |

| Botrytis cinerea | Present / Positive element homologs [10] | Present / Negative element, virulence regulator [10] | Light [10] | Virulence, Pathogenesis [10] |

| Fusarium oxysporum | Present / Positive element homologs essential for virulence [11] | Present / Primary negative element essential for virulence [11] | Light, Host signals (inferred) | Virulence, Toxin production, Zinc homeostasis [11] |

| Saccharomyces cerevisiae | Absent [12] | Absent [12] | Temperature, Metabolic cycles [12] | Respiratory oscillations (YROs), Gene expression [13] |

| Rhizoglomus irregulare | Present / Expressed in pre- and post-symbiotic stages [14] | Present / Expressed in pre- and post-symbiotic stages [14] | Host metabolic signals (hypothesized) [15] | Coordination with host plant physiology (hypothesized) [15] |

| Stress/Function | Key Clock-Controlled Gene/Protein | Mechanism of Regulation | Fungal Species | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Oxidative Stress | Catalase-1 (cat-1) | Transcriptional regulation by WCC | Neurospora crassa | [21] |

| Osmotic Stress | OS-2 (MAPK) | Rhythmic phosphorylation (activation) | Neurospora crassa | [21] |

| Osmotic Stress | ccg-1 (osmotic-responsive gene) | Transcriptional regulation downstream of rhythmic OS-2 activation | Neurospora crassa | [24] |

| Nutritional Stress | frequency (frq) | Epigenetic (histone acetylation) via GCN2/CPC-1/SAGA pathway | Neurospora crassa | [9] |

| Virulence | bcfrq1 (clock core component) | Required for rhythmic virulence | Botrytis cinerea | [10] |

| Zinc Starvation | FoZafA (Transcription Factor) | Rhythmic transcription regulated by the clock | Fusarium oxysporum | [11] |

| Toxin Production | FoCzf1 (Transcription Factor) | Rhythmic transcription regulated by the clock | Fusarium oxysporum | [11] |

| Translation | eEF-2 (Elongation Factor) | Rhythmic phosphorylation downstream of rhythmic OS-2 activation | Neurospora crassa | [27] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).