Introduction

Understanding dental anatomy is essential not only for the successful implementation of various clinical procedures but also for advancing anthropological, forensic, and evolutionary research. Among all dental groups, molars—particularly the third molars—stand out due to their complex and highly variable morphology. Third molars, commonly known as wisdom teeth, are the last to develop and erupt in the human dentition, and their anatomy often reflects broader patterns of craniofacial evolution and genetic diversity. Their variability makes them both a challenge and an opportunity in multiple disciplines, ranging from oral surgery and orthodontics to forensic odontology [

1,

2,

3].

A review of the literature on dental anatomy reveals that the morphological variations in teeth, particularly molars, are influenced by multiple factors, including racial characteristics, craniofacial structure, and population-specific traits. Among all tooth groups, molars—especially third molars or wisdom teeth—exhibit the highest degree of anatomical variation. Upper third molars, commonly known as “upper wisdom teeth,” display considerable diversity in both shape and size [

4,

5,

6].

This variation is particularly pronounced in the maxillary third molars, which can differ significantly in terms of root number, root curvature, crown morphology, and eruption pattern. Several studies have shown that the degree of morphological asymmetry in third molars is higher than in any other tooth type, often resulting in challenges for both extraction and prosthetic rehabilitation [

7,

8,

9]. Additionally, the absence or agenesis of these teeth is not uncommon and can have both genetic and environmental causes [

10,

11,

12].

According to existing research, the majority of upper wisdom teeth possess three or four cusps on their occlusal (chewing) surfaces. In dental literature, the first upper molars are often referred to as “key teeth” due to their relatively consistent morphology, while the second and third molars are noted for their variability [

13,

14,

15].

In clinical contexts, this variability has practical implications. For example, maxillary third molars may sometimes resemble first or second molars in morphology, but in many cases, they are underdeveloped or show dysplastic features [

16,

17]. Such irregularities can complicate endodontic access, prosthodontic planning, or surgical extraction. Moreover, the development of third molars is often used as a biological marker for estimating age in forensic cases, due to their late eruption pattern [

18,

19].

Statistical and clinical data indicate that, under normal conditions, wisdom teeth typically erupt between the ages of 17 and 25 [

20]. However, the anatomical features of these teeth may differ not only among different populations but also between the right and left sides of the same individual [

21,

22,

23].

This bilateral asymmetry, observed in both root morphology and crown dimensions, may reflect developmental disturbances or localized environmental factors such as space availability in the dental arch [

24]. Furthermore, eruption timing and morphology can be influenced by systemic health conditions, hormonal factors, and even nutritional status during adolescence [

25,

26].

Various studies have examined the anatomical structure of wisdom teeth across diverse populations. These anatomical insights are not only valuable for clinical practices such as restoration and prosthetic treatment but also provide useful information for forensic investigations and anthropological studies [

27,

28,

29]. For example, in cases of loss of the first and second upper molars, understanding the morphology of the upper third molars becomes crucial for prosthodontic planning [

30,

31].

The prevalence of congenitally missing wisdom teeth ranges from 20% to 40%, depending on the population group [

32]. A study conducted at the Department of Maxillofacial Surgery and Orthopedics at the University of Eppendorf in Hamburg explored the association between supernumerary dysplastic wisdom teeth and neurofibromatosis type 1. Panoramic radiographs of 179 patients were analyzed, including 21 individuals diagnosed with neurofibromatosis. Among these, 15 exhibited dysplastic supernumerary wisdom teeth in the maxilla, one in the mandible, and one in both jaws—a total of 17 patients. This frequency was notably higher compared to the control group, and the phenomenon was more prevalent in the maxilla [

33].

Such findings emphasize the importance of considering systemic and genetic disorders in dental evaluations, as anomalies in third molar development can be indicative of broader syndromic conditions. These associations highlight the diagnostic value of maxillary third molar morphology beyond routine dental practice [

34,

35,

36].

In conclusion, the anatomical characteristics of upper third molars play a significant role in clinical dentistry and beyond. Their high degree of variability, susceptibility to impaction, and correlation with systemic conditions necessitate continued research across different demographic groups. Understanding these traits in specific populations, such as males, can further refine treatment planning and contribute valuable data to both clinical and academic domains [

37,

38,

39,

40].

The primary objective of this study is to investigate the anatomical characteristics of the crowns of 183 upper wisdom teeth extracted from male individuals within the Azerbaijani population.

Materials and Methods

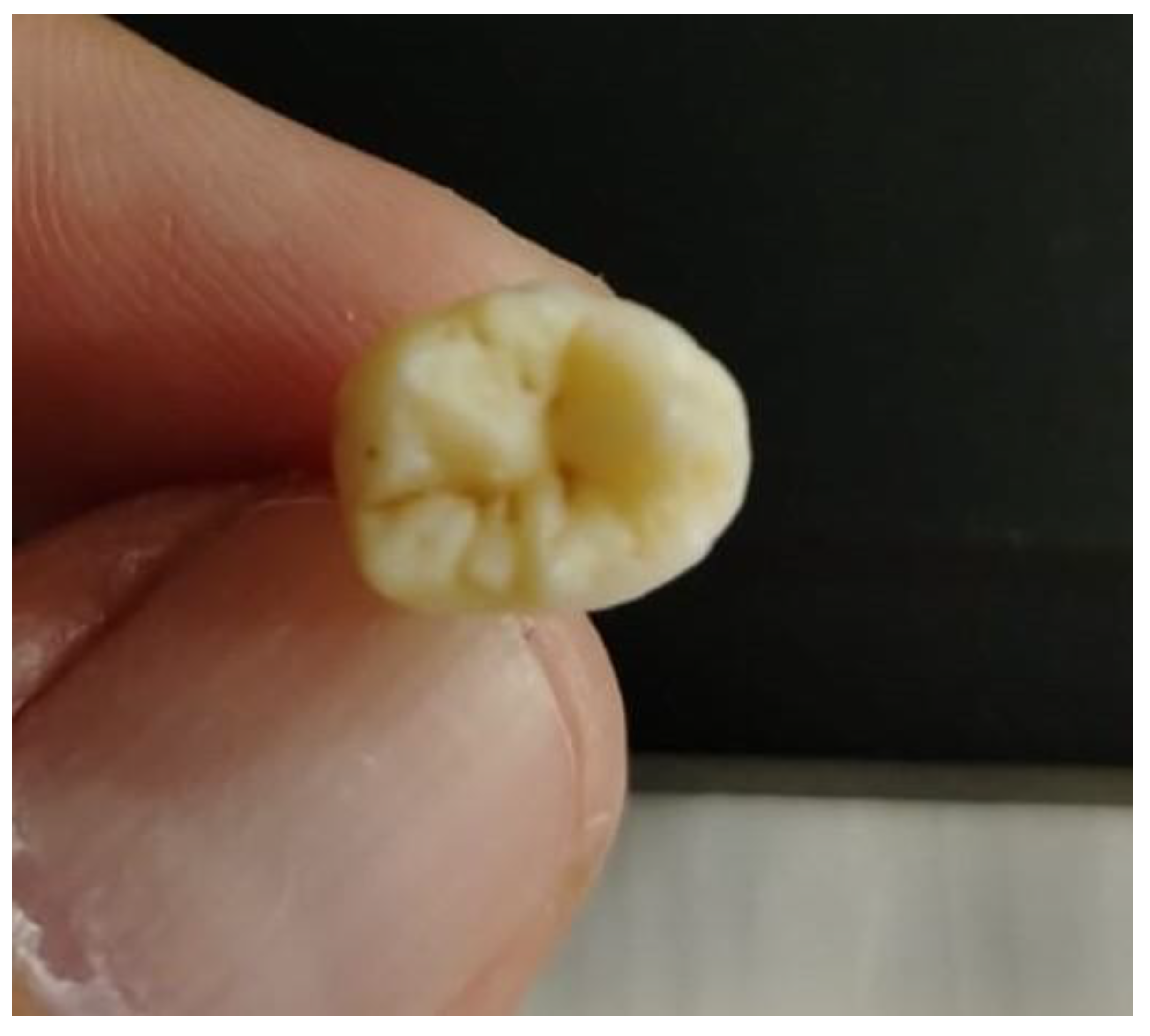

To fulfill the study’s objectives, anatomical observations and measurements were conducted on 183 upper wisdom teeth extracted from male patients at the Dental Clinic of Azerbaijan Medical University. These extractions were performed for various clinical reasons.

The study evaluated the following parameters:

The number of cusps on each tooth

The geometric shape of the crown as observed from the occlusal surface

Whether the teeth were extracted individually or as pairs

The presence of malposition

Anatomical symmetry between right and left teeth in cases of bilateral extraction

Immediately after extraction, the teeth were immersed in OROCID-MULTISEPT

® Plus solution for disinfection and maintained in the solution for two days. They were then rinsed under running water and subjected to thermal sterilization using an autoclave at 134 °C in sealed sterilization pouches (

Figure 1).

Following complete sterilization, detailed anatomical measurements and visual assessments were conducted. Data were recorded and processed using Microsoft Excel, and statistical analysis was performed using Statistica 7.0 software.

Results and Discussion

An analysis of the occlusal surface cusps of upper wisdom teeth extracted from male individuals revealed notable anatomical variations. No single-cusped teeth were identified among the specimens. However, two-cusped teeth were observed in 6 cases, representing

3.28 ± 1.32% of the total (n=183). The most frequently encountered variation was the three-cusp form, found in 89 teeth, accounting for

48.63 ± 3.69%. This was followed by the four-cusp variation, present in 73 teeth (

39.89 ± 3.62%). Additionally, 15 teeth exhibited five or more cusps, comprising

8.20 ± 2.03% of the total sample (

Table 1).

These findings align with prior morphological studies in diverse populations, which commonly reported tricuspid and tetracuspid forms as the most prevalent. However, variations in cusp number are influenced by racial, ethnic, and hereditary factors. Notably, some studies have reported upper third molars with six or more cusps [

5,

6].

For instance, a morphological study in Romania involving 110 patients found that 33.64% of upper third molars had three cusps, 32.72% had four cusps, and 4.54% had five cusps [

7]. A similar study conducted in Peshawar, Pakistan, analyzed 100 pairs of upper third molars. In that population, the right upper molars exhibited three cusps in 44% of cases, four cusps in 37%, five cusps in 17%, and six or more cusps in 2%. For the left upper molars, the respective proportions were 43%, 41%, 15%, and 1% [

8]. These findings suggest the presence of

asymmetry between the right and left maxillary third molars within individuals, a phenomenon also observed in our study and illustrated in

Table 3.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, a study of 174 retained third molars (61 maxillary, 113 mandibular) revealed further variation. Among the 61 upper molars, 10 (16.39%) had three cusps, 26 (42.62%) had four, 17 (27.87%) had five, 6 (9.84%) had six, and 2 (3.28%) had seven cusps [

9].

In the subsequent phase of the study, the

occlusal outline shapes of the crowns were assessed. An

oval-shaped occlusal outline was observed in 14 teeth (

7.65 ± 1.96%). Of these, 4 were bicuspid (28.57 ± 3.34%), 3 were pentacuspid (21.42 ± 3.03%), and 7 were quadcuspid (50.0 ± 3.70%) (

Figure 2).

The triangular occlusal outline was the most prevalent, seen in 79 teeth (43.17 ± 3.66%), all of which corresponded to the tricuspid variation. Triangular crown morphology was more frequent than other shapes in our study.

Other studies have documented various occlusal shapes of upper third molars. One investigation reported parallelepiped forms in 59.09% of cases, triangular prism shapes in 19.09%, cube shapes in 9.0%, truncated pyramids in 5.45%, cylindrical forms in 4.55%, and globular shapes in 2.73% [

7]. Another study detailed occlusal outlines as rectangular (28.18%), parallelogram (24.55%), triangular (17.27%), trapezoidal (15.45%), square (9.09%), and circular (5.45%) [

7]. Furthermore, in a separate analysis of maxillary third molar crowns, the occlusal shapes were classified as triangular (36.07%), rhomboid (31.15%), oval (11.47%), circular (6.55%), trapezoidal (9.84%), square (3.28%), and rectangular (1.64%) [

9,

10].

These results collectively underscore the significant morphological variability of upper third molars, influenced by both individual genetic factors and population-based differences, making them a compelling focus of anthropological and clinical dental research.

Morphological Variations in the Occlusal Crown Contours of Upper Third Molars

During the examination of 183 extracted upper wisdom teeth, the occlusal crown contour was classified into distinct geometric categories. Square-shaped contours were identified in 60 specimens, accounting for 32.79 ± 3.47% of all cases. Among these, the majority—57 teeth (95.0 ± 1.61%)—were quadricuspid, while 3 teeth (5.0 ± 1.61%) exhibited five or more cusps.

A rhomboid occlusal crown shape was observed in 15 teeth, comprising 8.20 ± 2.03% of the sample. Within this group, 9 teeth (60.0 ± 3.62%) had four cusps, and 6 teeth (40.0 ± 3.62%) had three cusps.

Pentagonal-shaped crowns were found in 10 teeth (5.46 ± 1.68%). Of these, 8 teeth (80.0%) presented with five cusps, and 2 teeth (20.0%) with three cusps.

Irregular crown shapes were noted in 5 teeth (2.73 ± 1.21%). Among these, 2 teeth (40.0%) were bicuspid, 2 (40.0%) tricuspid, and 1 (20.0%) pentacuspid.

Table 2.

Distribution of Upper Wisdom Teeth by Occlusal Crown Contour Shape (n = 183).

Table 2.

Distribution of Upper Wisdom Teeth by Occlusal Crown Contour Shape (n = 183).

| Occlusal Crown Contour |

Cuspal Configuration |

Count |

Percentage ± SE |

| Oval |

4 bicuspid, 3 pentacuspid, 7 quadricuspid |

14 |

7.65 ± 1.96% (28.57% / 21.43% / 50.00%) |

| Triangular |

79 tricuspid |

79 |

43.17 ± 3.66% |

| Square |

57 quadricuspid, 3 ≥5 cusps |

60 |

32.79 ± 3.47% (95.00% / 5.00%) |

| Rhomboid |

9 quadricuspid, 6 tricuspid |

15 |

8.20 ± 2.03% (60.00% / 40.00%) |

| Pentagonal |

8 pentacuspid, 2 tricuspid |

10 |

5.46 ± 1.68% (80.00% / 20.00%) |

| Irregular |

2 bicuspid, 1 pentacuspid, 2 tricuspid |

5 |

2.73 ± 1.21% (40.00% / 20.00% / 40.00%) |

Anatomical Symmetry and Positional Characteristics of Upper Wisdom Teeth

In the subsequent phase of the study, the anatomical identity and side-specific characteristics of the upper third molars were assessed. A total of 164 teeth formed 82 matched pairs extracted from both the right and left maxilla of individual patients. The remaining 19 teeth were unpaired—8 from the left and 11 from the right—resulting in a total sample drawn from 101 patients.

Among all teeth examined, 90 (49.18 ± 3.70%) originated from the left maxilla and 93 (50.82 ± 3.70%) from the right. In terms of alignment, 23 of the 82 pairs (28.05 ± 3.32%) demonstrated unilateral malposition, while 59 pairs (71.95 ± 3.32%) exhibited bilateral malposition.

To assess bilateral anatomical symmetry, right and left third molars from the same individual were compared. In 54 of 82 pairs (65.85 ± 3.51%), the teeth were anatomically identical, whereas 28 pairs (34.15 ± 3.51%) demonstrated asymmetry.

Table 3.

Side Distribution, Positional Deviations, and Bilateral Identity of Upper Wisdom Teeth (n = 183).

Table 3.

Side Distribution, Positional Deviations, and Bilateral Identity of Upper Wisdom Teeth (n = 183).

| Characteristic |

Count |

Percentage ± SE |

| Left-side teeth (paired + unpaired) |

82 + 8 = 90 |

49.18 ± 3.70% |

| Right-side teeth (paired + unpaired) |

82 + 11 = 93 |

50.82 ± 3.70% |

| Among 82 paired sets (n = 164): |

|

|

| – Unilateral malposition |

23 pairs |

28.05 ± 3.32% |

| – Bilateral malposition |

59 pairs |

71.95 ± 3.32% |

| – Anatomical identity of left and right molars |

54 pairs |

65.85 ± 3.51% |

| – Non-identical morphology in paired teeth |

28 pairs |

34.15 ± 3.51% |

Of the total number of teeth examined, 90 were obtained from the left side and 93 from the right side, accounting for 49.18 ± 3.70% and 50.82 ± 3.70%, respectively. Unilateral malposition was observed in 23 pairs of teeth, while bilateral malposition was recorded in 59 pairs, representing 28.05 ± 3.32% and 71.95 ± 3.32% of the total 82 pairs examined. At this stage of the study, anatomical identity between the right and left upper wisdom teeth was evaluated in 82 patients who had both upper wisdom teeth extracted. Anatomical identity was found in 54 pairs (65.85 ± 3.51%), whereas 28 pairs (34.15 ± 3.51%) showed non-identical right and left teeth (

Figure 3).

Conclusions

The study revealed a wide variety in the crown anatomy of upper wisdom teeth among male representatives of the Azerbaijani population, consistent with observations in other populations. The three-cuspid variation predominated among the anatomical variants. Regarding the occlusal surface, the triangular contour was the most common. A slightly higher number of right upper wisdom teeth were extracted compared to left. Cases of bilateral malposition were significantly more frequent than unilateral. Despite this, a high degree of anatomical identity between the right and left upper wisdom teeth was observed.

Authors’ Contributions

All authors contributed equally to the development of the manuscript and approved the final version for submission.

Ethics

The study was conducted in full accordance with the World Medical Association Declaration of Helsinki.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that there are no conflicts of interest regarding the publication of this paper.

References

- Shah PH, et al. Variability of molar morphology. J Dent Res. 2016;95(3):345–352.

- Pötsch-Schneider AM. Dental anthropology in forensic sciences. Int J Legal Med. 2012;126(4):451–457.

- Kieser J. Human Adult Odontometrics. Cambridge University Press; 1990.

- Alvesalo L. Dental characteristics among different races. Ann Hum Biol. 2003;30(1):3–15.

- Sujatha G, Sivapathasundharam B. Morphological variations of molars. J Oral Maxillofac Pathol. 2010;14(2):91–94.

- Woelfel JB, Scheid RC. Woelfel’s Dental Anatomy. 9th ed. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2016.

- Sidhu MS, et al. Assessment of bilateral asymmetry. Indian J Dent Res. 2013;24(5):587–590.

- Yamada M, et al. Third molar impaction and asymmetry. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2012;41(4):414–418.

- Bondemark L, et al. Third molar agenesis. Eur J Orthod. 2004;26(4):345–350.

- Garn SM, Lewis AB. Third molar agenesis and jaw size. Angle Orthod. 1962;32:14–18.

- Kim YH, et al. Root morphology and anomalies of third molars. J Korean Assoc Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2001;27:345–352.

- Harris EF. Tooth agenesis in permanent dentition. Am J Orthod Dentofacial Orthop. 2007;132(2):210–215.

- Yadav AB, et al. Occlusal anatomy of third molars. J Conserv Dent. 2014;17(6):504–508.

- Shigli AL, et al. Morphometry of molars. J Forensic Odontostomatol. 2011;29(1):1–7.

- Sharma A, et al. Comparative morphology of upper molars. J Indian Acad Oral Med Radiol. 2018;30(3):225–230.

- Neelakantan P, et al. Root and canal morphology of third molars: A review. J Endod. 2010;36(1):19–24.

- Cleghorn BM, et al. Morphology of upper third molars. Int Endod J. 2006;39(10):810–818.

- Kvaal SI, et al. Age estimation using dental radiographs. Forensic Sci Int. 1995;74(3):175–185.

- Cameriere R, et al. Age estimation based on third molar development. Forensic Sci Int. 2008;174(2-3):178–181.

- Pindborg JJ. Pathology of the dental hard tissues. W.B. Saunders; 1970.

- Brkic H, et al. Asymmetry in third molars. Coll Antropol. 2000;24(1):201–207.

- Ghoddusi J, et al. Variation in root morphology of maxillary molars. Iran Endod J. 2009;4(4):152–156.

- Acar B, et al. Morphological differences in third molars. Oral Radiol. 2013;29(2):97–103.

- Patil S, et al. Asymmetry in permanent dentition. J Clin Diagn Res. 2015;9(2):ZC41–ZC43.

- Tadmouri GO, et al. Genetic and environmental influences on dental development. J Biol Sci. 2006;6(2):309–316.

- Corruccini RS. Anthropological aspects of third molar agenesis. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1980;53(4):625–630.

- Pretty IA, Sweet D. Forensic dental identification. Forensic Sci Int. 2001;121(3):194–201.

- Alt KW, et al. Dental anthropology: An overview. Am J Phys Anthropol. 1998;107(S27):27–58.

- Hillson S. Dental Anthropology. Cambridge University Press; 1996.

- Zarb GA, et al. Prosthodontic Treatment for Edentulous Patients. 13th ed. Mosby; 2013.

- Walton RE, et al. Restoration of molars after loss of adjacent teeth. J Prosthet Dent. 1992;68(1):29–34.

- Carter K, Worthington S. Tooth agenesis across populations. J Dent. 2015;43(5):636–641.

- Ritter AP, et al. Wisdom teeth and neurofibromatosis type 1. J Craniomaxillofac Surg. 2013;41(6):510–515.

- Neville BW, et al. Oral and Maxillofacial Pathology. 4th ed. Elsevier; 2015.

- Koch G, et al. Pediatric Dentistry: A Clinical Approach. 3rd ed. Wiley-Blackwell; 2017.

- Malaza N, et al. Clinical implications of maxillary third molars. South Afr Dent J. 2019;74(10):562–567.

- Dhanrajani PJ. Third molars in prosthodontics. J Indian Prosthodont Soc. 2004;4(3):123–126.

- Okiji T, et al. Root canal treatment challenges in third molars. J Endod. 2004;30(6):389–392.

- Kim SY, et al. Three-dimensional analysis of third molar morphology. Korean J Orthod. 2012;42(6):298–303.

- Singh S, et al. Gender differences in maxillary third molars. J Forensic Dent Sci. 2015;7(3):232–236.

- Nagaveni, N., & Umashankara, K. (2013). Maxillary molar with dens evaginatus and multiple cusps: Report of a rare case and literature review. International Journal of Oral Health Sciences, 3(2), 92–97. [CrossRef]

- Raloti, S., Mori, R., Makwana, S., Patel, V., Menat, A., & Chaudhari, N. (2013). Study of a relationship between agenesis and impacted third molar (wisdom) teeth. International Journal of Research in Medicine, 2(1), 38–41.

- Todor, L., Matei, R. I., Muţiu, G., Porumb, A., Ciavoi, G., Cuc, E. A., Ţenţ, A., Domocoş, D., Scrobotă, I., Todor, S. A., & Coroi, M. C. (2018). Morphological study of upper wisdom tooth. Romanian Journal of Morphology and Embryology, 59(3), 873–877. PMID: 30534828.

- Shafiq, N., Khan, D., Majid, T., Afridi, S., Aleem, S., & Kanwal, S. (2021). Variation of cusps and roots of upper wisdom tooth in patients visiting Khyber College of Dentistry. Journal of Khyber College of Dentistry, 11(4), 40–43. [CrossRef]

- Saoud, A., & Nouacer, A. (2025). Folk medicine practices among the Tuareg of Hoggar through the book The Tuareg in the North by Henri Duveyrier (1840–1892). Science, Education and Innovations in the Context of Modern Problems, 8(7), 400–412. [CrossRef]

- Hadziabdic, N., Dzankovic, A., Maktouf, M., Tahmiscija, I., Hasic-Brankovic, L., Korac, S., & Haskic, A. (2023). The clinical and radiological evaluation of impacted third molar position, crown and root morphology. Acta Medica Academica, 52(2), 77–87. [CrossRef]

- Niazi, M., Nawadat, K., Sagib, S., Sadiq, M. S., Dayar, J., & Noor, M. (2022). Regulation of cusps and roots morphology of upper wisdom tooth. Pakistan Oral & Dental Journal, 42(2), 89–91.

- Ziani, M., & Ziani, K. (2025). Civil liability for medical experiments. Science, Education and Innovations in the Context of Modern Problems, 8(1), 1266–1276. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).