Submitted:

03 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

1.1. Background

1.1.1. Training in Speech Therapy

1.1.2. Virtual Reality-based Simulation

1.2. Rationale

1.3. Objectives

- How is virtual reality being used in the education and clinical training of speech-language pathology students?

- What are the educational, technological, and methodological characteristics of VR-based interventions in speech-language pathology training?

- What outcomes and benefits are reported in the literature regarding the use of VR in the training of speech-language pathology students? How are these assessed?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Protocol and Registration

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

- The study was targeted to students or trainees in speech therapy and language pathology field;

- The study involved the use of virtual reality (including immersive, semi-immersive, and non-immersive formats) or, it assessed or evaluated the use of the VR technology;

- The purpose was the education and/or training of students.

2.3. Information Sources

2.4. Search

2.4.1. Exceptions

2.5. Selection of Sources of Evidence

2.6. Data Charting Process

2.7. Data Items

2.8. Critical Appraisal of Individual Sources of Evidence

2.9. Synthesis of Results

3. Results

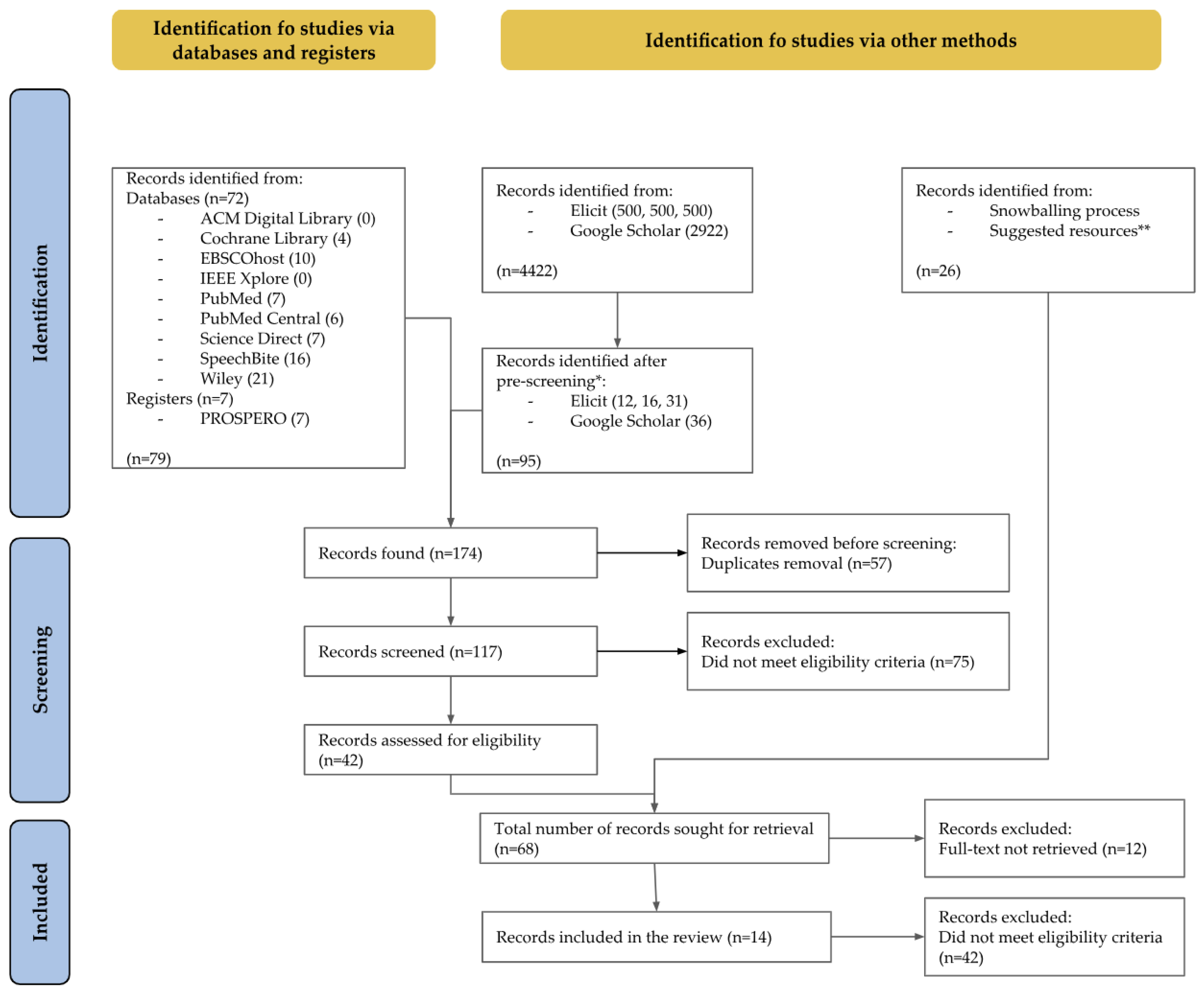

3.1. Selection of Sources of Evidence

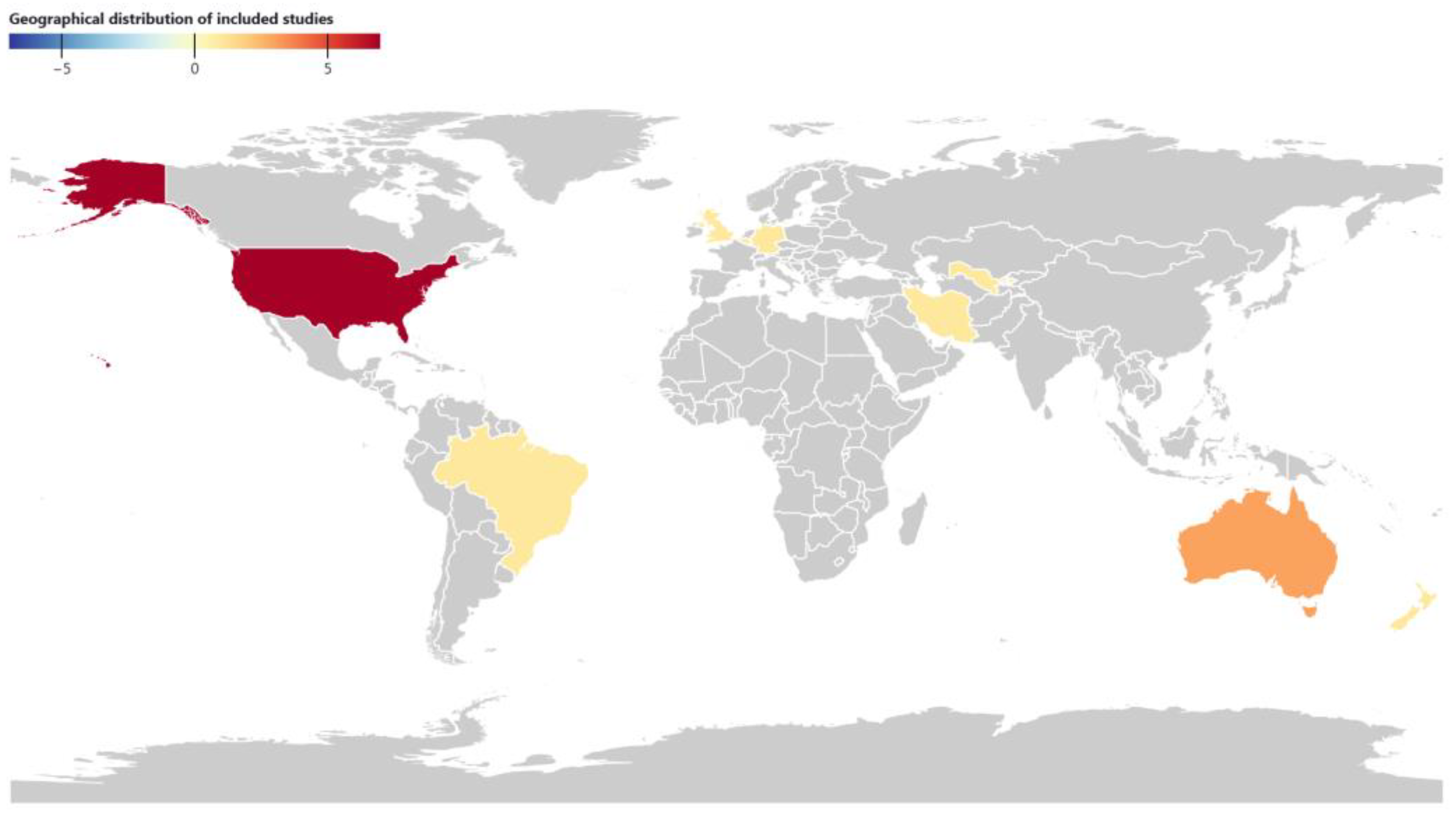

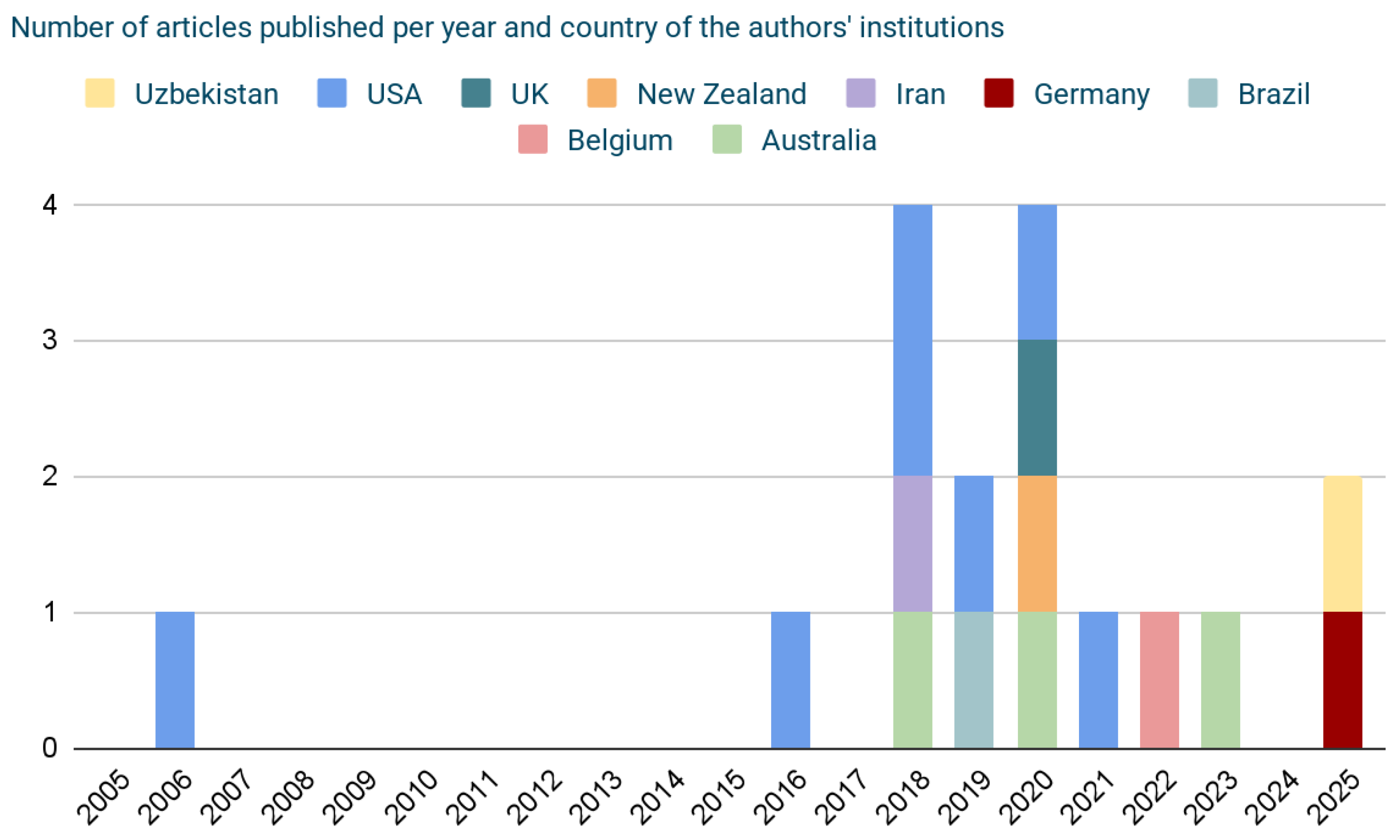

3.2. Characteristics of Sources of Evidence

3.3. Critical Appraisal Within Sources of Evidence

3.4. Results of Individual Sources of Evidence

3.5. Synthesis of Results

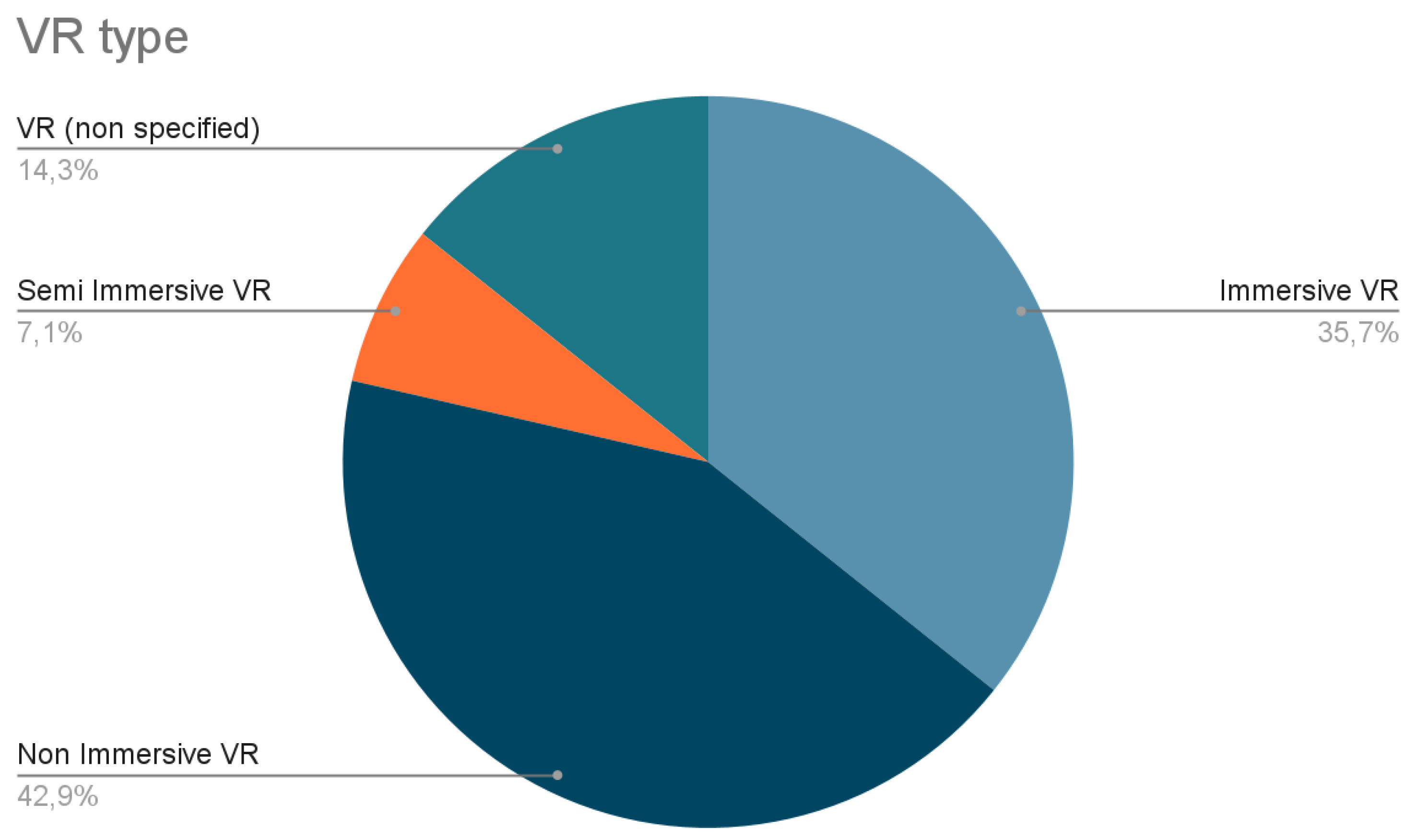

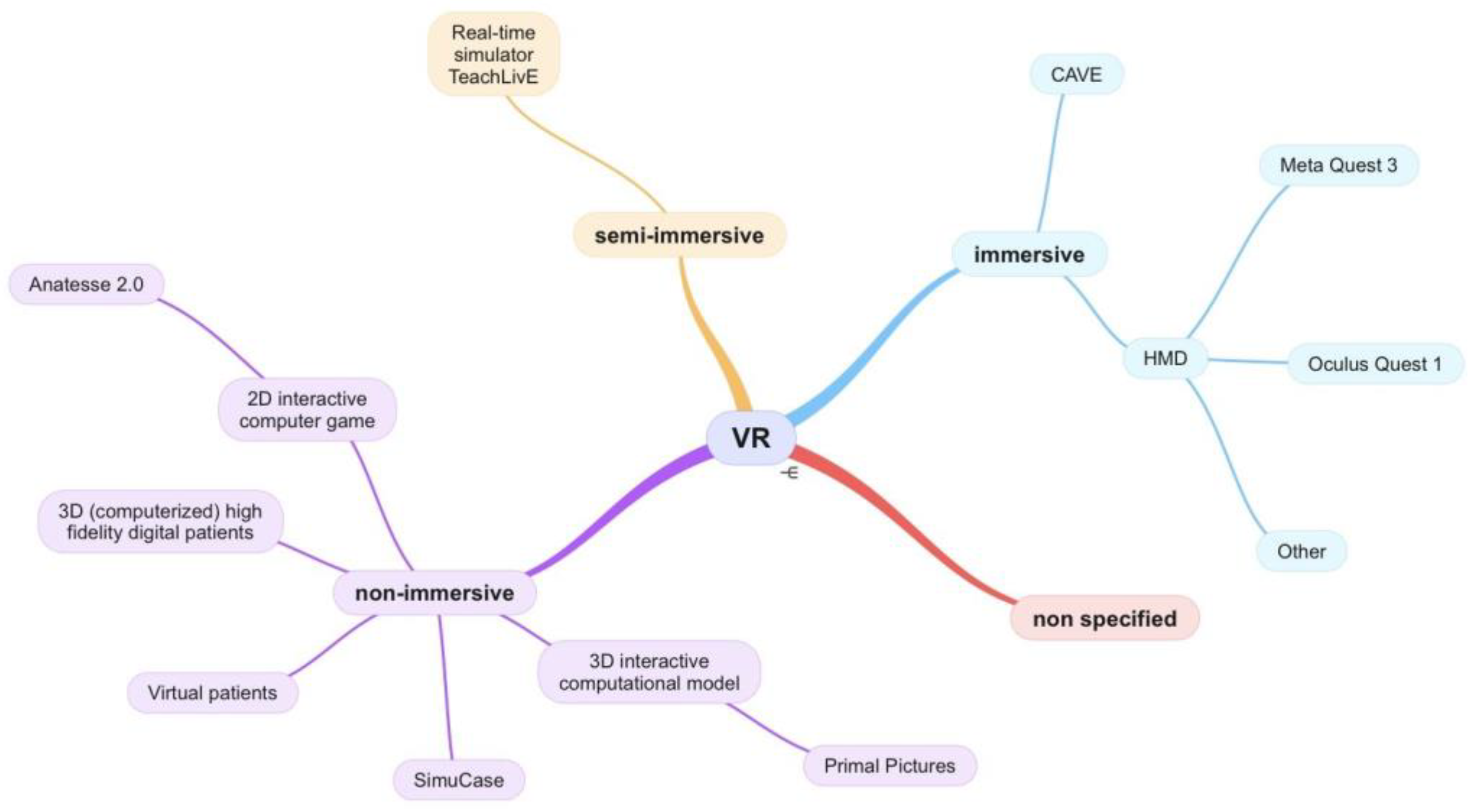

3.5.1. Virtual Reality - Type and Characteristics

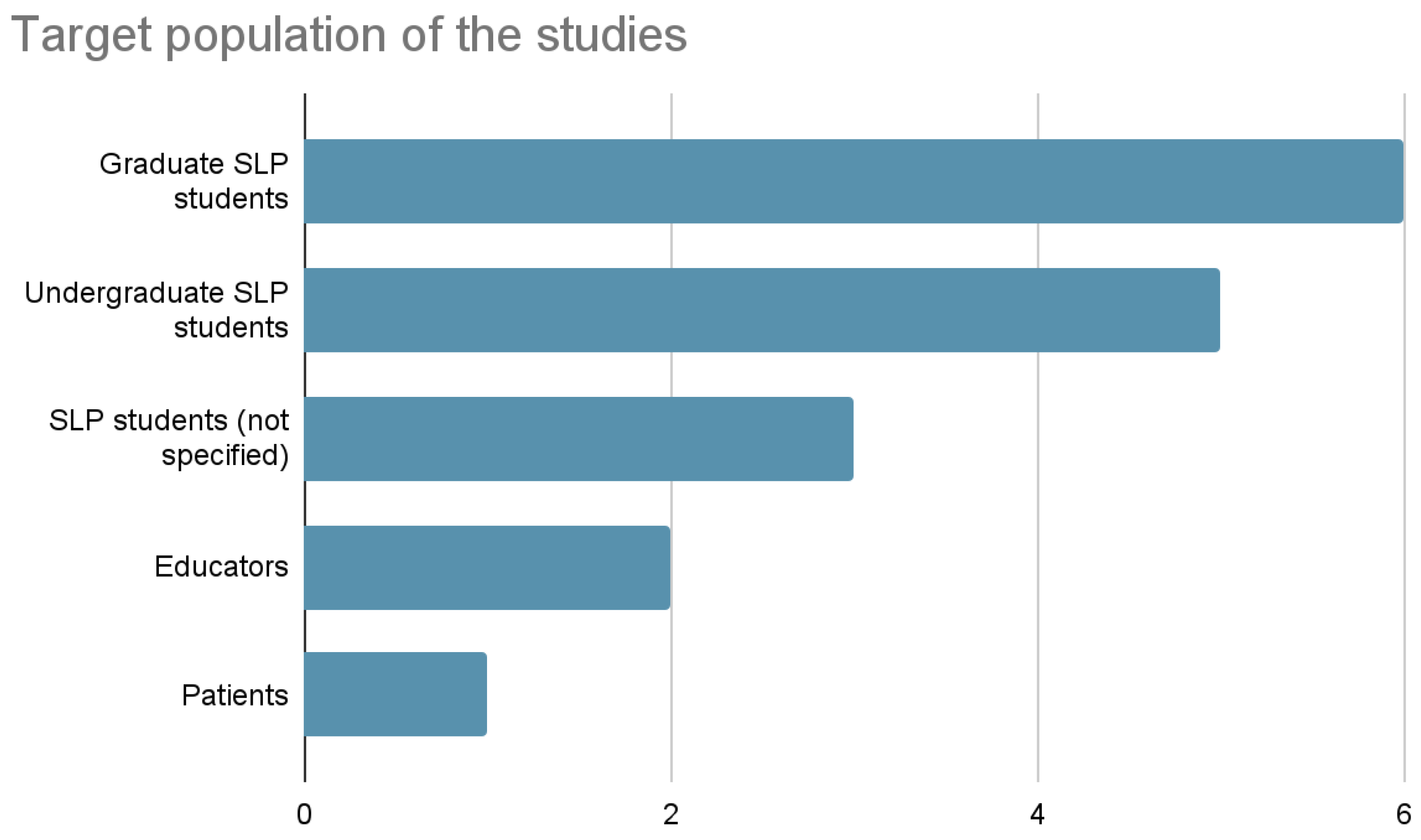

3.5.2. Population

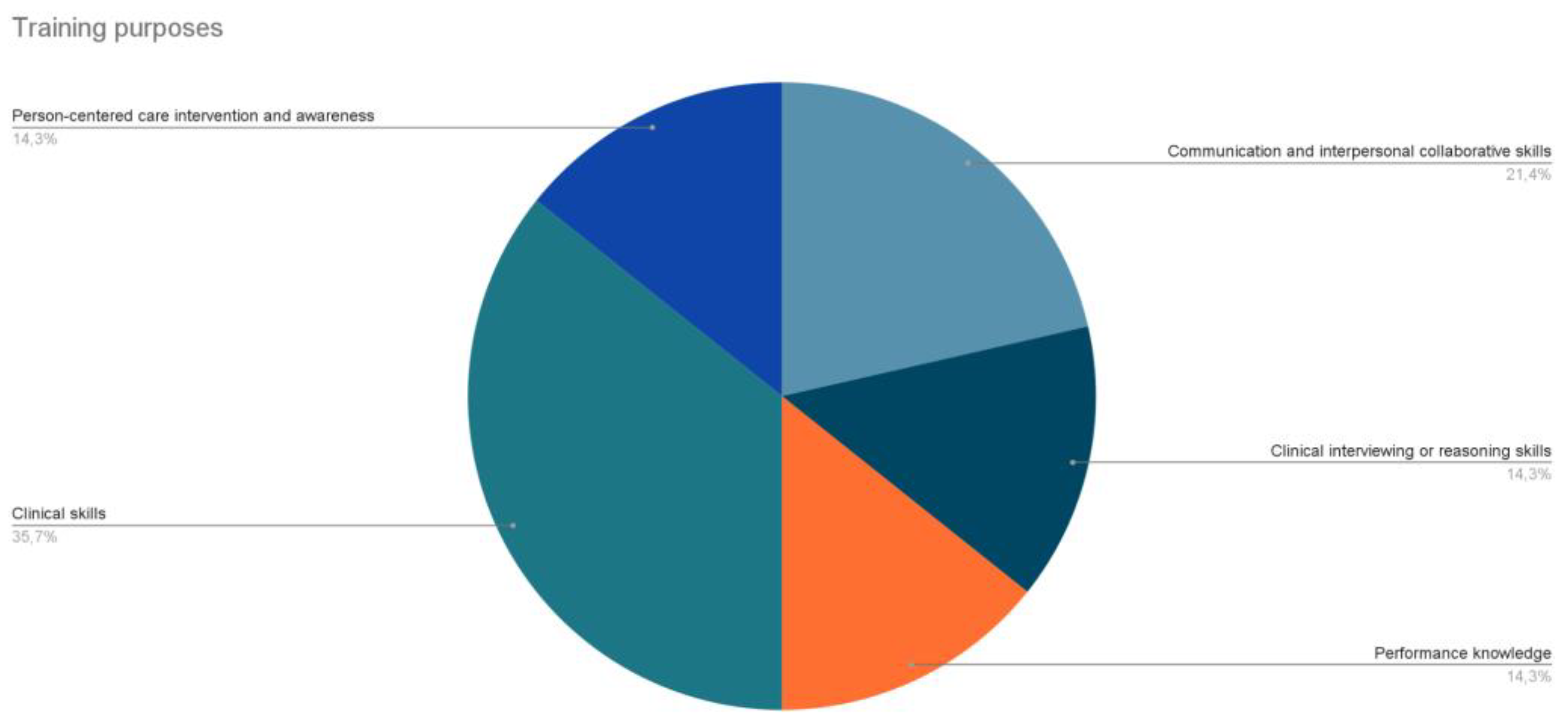

3.5.3. Training Purposes (and Sub-Fields of Application)

3.5.4. Main Outcomes and Assessment Methods

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of Evidence

Additional Considerations

4.2. Limitations

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| VR | Virtual Reality |

| ST | Speech Therapy |

| SLT | Speech and Language Therapy |

| SLP | Speech and Language Pathology |

| FEES | Flexible Endoscopic Evaluation of Swallowing |

| tDCS | Transcranial Direct Current Stimulation |

| TTM | Tracheostomy Tube Management |

| TCM | Tracheal Cannula Management |

| CFCC | Council for Clinical Certification in Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology |

| ASHA | American Speech-Language-Hearing Association |

| CAPCSD | Council of Academic Programs in Communication Sciences and Disorders |

| VICSR | Virtual Immersion Center for Simulation Research |

| HMD | Head Mounted Display |

| SLHS | Speech-Language and Hearing Sciences |

| OMA | Oral Musculature Assessment |

Appendix A

A.1. Title

A.2. Abstract

A.3. Keywords

A.4. Introduction

A.4.1. Background

A.4.2. Rationale

A.4.3. Objectives

A.5. Review Questions

- How is virtual reality being used in the education and clinical training of speech-language pathology students?

- What are the educational, technological, and methodological characteristics of VR-based interventions in speech-language pathology training?

- What outcomes and benefits are reported in the literature regarding the use of VR in the training of speech-language pathology students? How are these assessed?

A.6. Inclusion criteria

A.6.1. Population

A.6.2. Concept

A.6.3. Context

A.6.4. Types of sources

A.7. Methods

A.7.1. Search strategy

A.7.2. Study/Source of evidence selection

- Title and abstract screening.

- Full text review.

A.7.3. Data extraction

A.7.4. Data analysis and presentation

Appendix B

| Database | Query | Filter | Identified articles |

|---|---|---|---|

| ACM Digital Library | ("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logop*) AND ("VR" OR "virtual reality") AND (training*) AND (student*) ("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logop*) AND ("VR" OR "virtual reality") AND (training*) AND (student* OR educat*) |

title OR publication title OR abstract OR keywords | 0 0 |

| Cochrane Library | (("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logop*) AND ("VR" OR "virtual reality") AND (training*) AND (student*)):ti,ab,kw (("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logop*) AND ("VR" OR "virtual reality") AND (training*) AND (student* OR educat*)):ti,ab,kw |

title OR publication title OR abstract OR keywords | 1 3 |

| EBSCOhost | ("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logop*) AND ("VR" OR "virtual reality") AND (training*) AND (student*) ("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logop*) AND ("VR" OR "virtual reality") AND (training*) AND (student* OR educat*) |

- | 3 7 |

| IEEE Xplore | "Publication Title":("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logop*) AND ("VR" OR "virtual reality") AND (training*) AND (student*) OR "Abstract":("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logop*) AND ("VR" OR "virtual reality") AND (training*) AND (student*) OR "Author Keywords":("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logop*) AND ("VR" OR "virtual reality") AND (training*) AND (student*) "Publication Title":("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logop*) AND ("VR" OR "virtual reality") AND (training*) AND (student* OR educat*) OR "Abstract":("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logop*) AND ("VR" OR "virtual reality") AND (training*) AND (student* OR educat*) OR "Author Keywords":("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logop*) AND ("VR" OR "virtual reality") AND (training*) AND (student* OR educat*) |

publication title OR abstract OR author keywords |

0 0 |

| PROSPERO | ("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logop*) AND ("VR" OR "virtual reality") AND (training*) AND (student* OR educat*) | - | 7 |

| PubMed | ("speech therapy"[Title/Abstract] OR "speech-language therapy"[Title/Abstract] OR "SLT"[Title/Abstract] OR "speech pathology"[Title/Abstract] OR "speech-language pathology"[Title/Abstract] OR "SLP"[Title/Abstract] OR logop*[Title/Abstract]) AND ("VR"[Title/Abstract] OR "virtual reality"[Title/Abstract]) AND (training*[Title/Abstract]) AND (student*[Title/Abstract]) ("speech therapy"[Title/Abstract] OR "speech-language therapy"[Title/Abstract] OR "SLT"[Title/Abstract] OR "speech pathology"[Title/Abstract] OR "speech-language pathology"[Title/Abstract] OR "SLP"[Title/Abstract] OR logop*[Title/Abstract]) AND ("VR"[Title/Abstract] OR "virtual reality"[Title/Abstract]) AND (training*[Title/Abstract]) AND (student*[Title/Abstract] OR educat*[Title/Abstract]) |

title OR abstract | 2 6 |

| PubMed Central | (("speech therapy"[Abstract] OR "speech-language therapy"[Abstract] OR "SLT"[Abstract] OR "speech pathology"[Abstract] OR "speech-language pathology"[Abstract] OR "SLP"[Abstract] OR logop*[Abstract]) AND ("VR"[Abstract] OR "virtual reality"[Abstract]) AND (training*[Abstract]) AND (student*[Abstract])) OR (("speech therapy"[Title] OR "speech-language therapy"[Title] OR "SLT"[Title] OR "speech pathology"[Title] OR "speech-language pathology"[Title] OR "SLP"[Title] OR logop*[Title]) AND ("VR"[Title] OR "virtual reality"[Title]) AND (training*[Title]) AND (student*[Title])) (("speech therapy"[Abstract] OR "speech-language therapy"[Abstract] OR "SLT"[Abstract] OR "speech pathology"[Abstract] OR "speech-language pathology"[Abstract] OR "SLP"[Abstract] OR logop*[Abstract]) AND ("VR"[Abstract] OR "virtual reality"[Abstract]) AND (training*[Abstract]) AND (student*[Abstract] OR eduact*[Abstract])) OR (("speech therapy"[Title] OR "speech-language therapy"[Title] OR "SLT"[Title] OR "speech pathology"[Title] OR "speech-language pathology"[Title] OR "SLP"[Title] OR logop*[Title]) AND ("VR"[Title] OR "virtual reality"[Title]) AND (training*[Title]) AND (student*[Title] OR educat*[Title])) |

title OR abstract |

3 3 |

| Science Direct | "(speech language therapy OR ""SLT"" OR speech language pathology OR ""SLP"" OR logop) AND (""VR"" OR ""virtual reality"") AND (training) AND (student) (speech language therapy OR ""SLT"" OR speech language pathology OR ""SLP"" OR logop) AND (""virtual reality"") AND (training) AND (student)" (speech language therapy OR "SLT" OR speech language pathology OR "SLP" OR logop) AND ("virtual reality") AND (training) AND (student OR education) |

title OR abstract OR specified keywords | 2 2 3 |

| SpeechBite | "virtual reality" | - | 16 |

| Wiley | ("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logop*) AND ("VR" OR "virtual reality") AND (training*) AND (student*) ("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logop*) AND ("VR" OR "virtual reality") AND (training*) AND (student* OR educat*) |

title OR abstract OR keywords | 17 4 |

Appendix C

| Query | Identified articles |

|---|---|

| allintitle: ("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logopedie OR logopaedie OR logopedics OR logopaedics) AND (VR OR "virtual reality") AND (training OR trainings) AND (student OR students) -child -children -deaf -autism -rehabilitation | 0 |

| allintitle: ("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logopedie OR logopaedie OR logopedics OR logopaedics) AND (VR OR "virtual reality") AND (training OR trainings) AND (student OR students) | 0 |

| allintitle: ("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logopedie OR logopaedie OR logopedics OR logopaedics) AND (VR OR "virtual reality") AND (training OR trainings) -child -children -deaf -autism -rehabilitation | 1* |

| allintitle: ("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logopedie OR logopaedie OR logopedics OR logopaedics) AND (VR OR "virtual reality") AND (training OR trainings) | 1* |

| allintitle: ("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logopedie OR logopaedie OR logopedics OR logopaedics) AND (VR OR "virtual reality") AND (student OR students) | 0 |

| allintitle: ("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logopedie OR logopaedie OR logopedics OR logopaedics) AND (VR OR "virtual reality") -child -children -deaf -autism -rehabilitation | 4* |

| allintitle: ("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logopedie OR logopaedie OR logopedics OR logopaedics) AND (VR OR "virtual reality") | 5* |

| allintitle: ("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logopedie OR logopaedie OR logopedics OR logopaedics) AND (VR OR "virtual reality") AND (education OR educational) | 1* |

| ("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logopedie OR logopaedie OR logopedics OR logopaedics) AND (VR OR "virtual reality") AND (training OR trainings) AND (student OR students OR education OR educational) | 15800 |

| ("speech therapy" OR "speech-language therapy" OR "SLT" OR "speech pathology" OR "speech-language pathology" OR "SLP" OR logopedie OR logopaedie OR logopedics OR logopaedics) AND (VR OR "virtual reality") AND (training OR trainings) AND (student OR students OR education OR educational) -child -children -deaf -autism -rehabilitation | 2910* |

Appendix D

| Title & Reference | Year | Country | Language | Study type | VR type | VR characteristics | Population | Training purposes (and sub-field) |

Main outcomes and assessment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

References

- World Health Organization. Ageing and health. Available online: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/ageing-and-health (accessed on 28 May 2025).

- OECD. What Do We Know about Young People’s Interest in Health Careers?; OECD Publishing, 2025. [CrossRef]

- World Health Organization. Transforming and Scaling up Health Professionals’ Education and Training: World Health Organization Guidelines 2013; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2013.

- World Health Organization. Global Strategy on Human Resources for Health: Workforce 2030; World Health Organization: Geneva, 2016.

- The European Higher Education Area in 2024: Bologna Process Implementation Report; European Education and Culture Executive Agency, Ed.; Publications Office: Luxembourg, 2024. [CrossRef]

- McGaghie, W. C.; Issenberg, S. B.; Barsuk, J. H.; Wayne, D. B. A Critical Review of Simulation-Based Mastery Learning with Translational Outcomes. Med Educ 2014, 48 (4), 375–385. [CrossRef]

- Sung, H.; Kim, M.; Park, J.; Shin, N.; Han, Y. Effectiveness of Virtual Reality in Healthcare Education: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Sustainability 2024, 16 (19), 8520. [CrossRef]

- Kyaw, B. M.; Saxena, N.; Posadzki, P.; Vseteckova, J.; Nikolaou, C. K.; George, P. P.; Divakar, U.; Masiello, I.; Kononowicz, A. A.; Zary, N.; Tudor Car, L. Virtual Reality for Health Professions Education: Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis by the Digital Health Education Collaboration. J Med Internet Res 2019, 21 (1), e12959. [CrossRef]

- Christmas, C.; Rogus-Pulia, N. Swallowing Disorders in the Older Population. J American Geriatrics Society 2019, 67 (12), 2643–2649. [CrossRef]

- Springer, L.; Zückner, H. Empfehlende Ausbildungsrichtlinie für die staatlich anerkannten Logopädieschulen in NRW. 16 Aug 2006.

- Council for Clinical Certification in Audiology and Speech-Language Pathology of the American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. 2020 Standards for the Certificate of Clinical Competence in Speech-Language Pathology; American Speech-Language-Hearing Association, 2018. https://www.asha.org/certification/2020-SLP-Certification-Standards.

- American Speech-Language-Hearing Association. 2020 Standards for Certification of the Practice of Speech-Language Pathology. Available online: https://www.asha.org/certification/2020-slp-certification-standards/?srsltid=AfmBOorFKk7aftWeRQ0iWAasSV3KNTgwxUxORZHRVKC_E_aMM3V1r9d_#5 (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Speech Pathology Australia. Simulation-Based Learning Program. Available online: https://www.speechpathologyaustralia.org.au/Public/Public/About-Us/Ethics-and-standards/Simulation-based-learning-program.aspx?hkey=f0d1f1f5-c9f7-4806-9f18-1e3993ce09c0 (accessed on 17 June 2025).

- Council of Academic Programs in Communication Sciences and Disorders. Best Practices in Healthcare Simulations in Communication Sciences and Disorders. March 2019. Available online: https://growthzonesitesprod.azureedge.net/wp-content/uploads/sites/1023/2020/03/Best-Practices-in-CSD.pdf (accessed on: 17 June 2025).

- Slater, M.; Wilbur, S. A Framework for Immersive Virtual Environments (FIVE): Speculations on the Role of Presence in Virtual Environments. Presence: Teleoperators & Virtual Environments 1997, 6 (6), 603–616. [CrossRef]

- Using Immersive Technologies to Enhance Student Learning Outcomes in Clinical Sciences Education and Training; 2023. [CrossRef]

- Dhar, E.; Upadhyay, U.; Huang, Y.; Uddin, M.; Manias, G.; Kyriazis, D.; Wajid, U.; AlShawaf, H.; Syed Abdul, S. A Scoping Review to Assess the Effects of Virtual Reality in Medical Education and Clinical Care. DIGITAL HEALTH 2023, 9, 20552076231158022. [CrossRef]

- Bryant, L.; Brunner, M.; Hemsley, B. A Review of Virtual Reality Technologies in the Field of Communication Disability: Implications for Practice and Research. Disability and Rehabilitation: Assistive Technology 2020, 15 (4), 365–372. [CrossRef]

- Rose, T. A.; Copley, A.; Scarinci, N. A. Benefits of Providing an Acute Simulated Learning Environment to Speech Pathology Students: An Exploratory Study. FoHPE 2017, 18 (3), 44–59. [CrossRef]

- Hemmerich, A.; Hoepner, J. Using Video Simulations for Assessing Clinical Skills in Speech-Language Pathology Students. JoTLT 2022, 11 (1). [CrossRef]

- Petrich, T.; Mills, B.; Lewis, A.; Hansen, S.; Brogan, E.; Ciccone, N. Utilisation of Simulation-Based Learning to Decrease Student Anxiety and Increase Readiness for Clinical Placements for Speech-Language Pathology Students. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 2024, 26 (3), 380–389. [CrossRef]

- Peters, M. D.; Godfrey, C.; McInerney, P.; Munn, Z.; Tricco, A. C.; Khalil, H. Scoping Reviews. In JBI Manual for Evidence Synthesis; Aromataris, E., Lockwood, C., Porritt, K., Pilla, B., Jordan, Z., Eds.; JBI, 2024. [CrossRef]

- Tricco, A. C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K. K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M. D. J.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; Hempel, S.; Akl, E. A.; Chang, C.; McGowan, J.; Stewart, L.; Hartling, L.; Aldcroft, A.; Wilson, M. G.; Garritty, C.; Lewin, S.; Godfrey, C. M.; Macdonald, M. T.; Langlois, E. V.; Soares-Weiser, K.; Moriarty, J.; Clifford, T.; Tunçalp, Ö.; Straus, S. E. PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018, 169 (7), 467–473. [CrossRef]

- Elicit. Available online: https://elicit.com/ (accessed on 28 June 2025).

- Williams, S. L. The Virtual Immersion Center for Simulation Research: Interactive Simulation Technology for Communication Disorders. 2006.

- Sia, I.; Halan, S.; Lok, B.; Crary, M. A. Virtual Patient Simulation Training in Graduate Dysphagia Management Education—A Research-Led Enhancement Targeting Development of Clinical Interviewing and Clinical Reasoning Skills. Perspect ASHA SIGs 2016, 1 (13), 130–139. [CrossRef]

- Banszki, F.; Beilby, J.; Quail, M.; Allen, P.; Brundage, S.; Spitalnick, J. A Clinical Educator’s Experience Using a Virtual Patient to Teach Communication and Interpersonal Skills. AJET 2018, 34 (3). [CrossRef]

- Moradi, N.; Rahimifar, P.; Soltani, M.; Shaterzadeh-Yazdi, M. J.; Hosseini Bidokhti, M. Oral Functional Assessment Training in Speech Therapy Students Using Virtual Reality (VR). Int. J. Musculoskelet. Pain Prev. 2018, 3 (3), 87–89.

- University of Central Florida; Towson Ph.D., Ccc-Slp, J. A.; Taylor Ph.D., M. S.; University of Central Florida; Pt, Dpt, Pc S, J. T.; University of Central Florida; Paul Ph.D., Bcba, C.; Georgia State University; Pabian Pt, Dpt, Sc S, Oc S, P.; University of Central Florida; Zraick Ph.D., Ccc-Slp, R. I.; University of Central Florida. Impact of Virtual Simulation and Coaching on the Interpersonal Collaborative Communication Skills of Speech-Language Pathology Students: A Pilot Study. TLCSD 2018, 2 (2). [CrossRef]

- Carter, M. D. The Effects of Computer-Based Simulations on Speech-Language Pathology Student Performance. Journal of Communication Disorders 2019, 77, 44–55. [CrossRef]

- Rondon-Melo, S.; Andrade, C. R. F. D. Efeitos Do Uso de Diferentes Tecnologias Educacionais Na Aprendizagem Conceitual Sobre o Sistema Miofuncional Orofacial. Audiol., Commun. Res. 2019, 24, e2050. [CrossRef]

- Miles, A.; Hayden, S.; Carnell, S.; Halan, S.; Lok, B. What Do Speech Pathology Students Gain from Virtual Patient Interviewing? A WHO International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health (ICF) Analysis. BMJ STEL 2020, bmjstel-2020-000616. [CrossRef]

- Robinson, K. E.; Allen, P. J.; Quail, M.; Beilby, J. Virtual Patient Clinical Placements Improve Student Communication Competence. Interactive Learning Environments 2020, 28 (6), 795–805. [CrossRef]

- Blaydes, M. S. Effects of a Virtual Reality Dementia Experience on Graduate Communication Disorders Students’ Future Clinical Practice. https://encompass.eku.edu/etd/687/.

- Deman, H.; Boets, B.; Hermans, D.; Rombouts, E. Virtual Reality and Stuttering: A Tool for Experiential Learning in Preservice Speech Therapy Education. https://lirias.kuleuven.be/3711926.

- Kelly, B.; Walters, J.; Unicomb, R. Speech Pathology Student Perspectives on Virtual Reality to Learn a Clinical Skill. TeachingandLearninginCommunicationSciences&Disorders 2023, 7(1). [CrossRef]

- Gentile, F.; Wanke, M.; Mueller, W. Virtual Reality in Speech Therapy Training: Scenarios and Prototyping. In Proceedings of INTED2025 Conference; IATED: Valencia, Spain, 3-5 March 2025.

- THE USE OF INFORMATION AND COMMUNICATION TECHNOLOGIES IN PREPARING FUTURE SPEECH THERAPISTS FOR PROFESSIONAL PRACTICE | International Multidisciplinary Journal for Research & Development. https://www.ijmrd.in/index.php/imjrd/article/view/2724 (accessed 2025-05-27).

- MacBean, N.; Theodoros, D.; Davidson, B.; Hill, A. E. Simulated Learning Environments in Speech-Language Pathology: An Australian Response. International Journal of Speech-Language Pathology 2013, 15 (3), 345–357. [CrossRef]

- Jiang, H.; Vimalesvaran, S.; Wang, J. K.; Lim, K. B.; Mogali, S. R.; Car, L. T. Virtual Reality in Medical Students’ Education: Scoping Review. JMIR Med. Educ. 2022, 8 (1), e34860. [CrossRef]

- Hood, R. J.; Maltby, S.; Keynes, A.; Kluge, M. G.; Nalivaiko, E.; Ryan, A.; Cox, M.; Parsons, M. W.; Paul, C. L.; Garcia-Esperon, C.; Spratt, N. J.; Levi, C. R.; Walker, F. R. Development and Pilot Implementation of TACTICS VR: A Virtual Reality-Based Stroke Management Workflow Training Application and Training Framework. Front. Neurol. 2021, 12, 665808. [CrossRef]

- Chiang, D. H.; Huang, C. C.; Cheng, S. C.; Cheng, J. C.; Wu, C. H.; Huang, S. S.; Yang, Y. Y.; Yang, L. Y.; Kao, S. Y.; Chen, C. H.; Shulruf, B.; Lee, F. Y. Immersive Virtual Reality (VR) Training Increases the Self-Efficacy of In-Hospital Healthcare Providers and Patient Families Regarding Tracheostomy-Related Knowledge and Care Skills: A Prospective Pre-Post Study. Medicine 2022, 101 (2), e28570. [CrossRef]

- Overby, M. Stakeholders’ Qualitative Perspectives of Effective Tele-Practice Pedagogy in Speech–Language Pathology. Int. J. Language Communication Disorders. 2018, 53 (1), 101–112.

- Page, M. J.; McKenzie, J. E.; Bossuyt, P. M.; Boutron, I.; Hoffmann, T. C.; Mulrow, C. D.; Moher, D. The PRISMA 2020 Statement: An Updated Guideline for Reporting Systematic Reviews. BMJ 2021, 372, n71. [CrossRef]

| Focus | Keywords |

|---|---|

| Population | speech therapy, speech-language therapy, SLT, speech pathology, speech-language pathology, SLP, logop* (i.e. logopedie, logopaedie, logopedics, logopaedics), student* (i.e. student, students) |

| Concept | VR, virtual reality |

| Context | training* (i.e. training, trainings), educat* (i.e. education, educational) |

| Title and Reference | Year | Country | Language | Study type |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| The Virtual Immersion Center for Simulation Research: Interactive Simulation Technology for Communication Disorders [25] | 2006 | USA (Ohio) | en | Pilot |

| Virtual Patient Simulation Training in Graduate Dysphagia Management Education—A Research-Led Enhancement Targeting Development of Clinical Interviewing and Clinical Reasoning Skills [26] | 2016 | USA (Florida) | en | Mixed methods |

| A Clinical Educator’s Experience Using a Virtual Patient to Teach Communication and Interpersonal Skills [27] | 2018 | USA (Georgia) Australia |

en | Qualitative |

| Oral Functional Assessment Training in Speech Therapy Students Using Virtual Reality (VR) [28] | 2018 | Iran | en | Descriptive |

| Impact of Virtual Simulation and Coaching on the Interpersonal Collaborative Communication Skills of Speech-Language Pathology Students: A Pilot Study [29] | 2018 | USA (Florida) | en | Pilot, Experimental |

| The Effects of Computer-Based Simulations on Speech-Language Pathology Student Performance [30] | 2019 | USA (Georgia) | en | Experimental |

| Efeitos Do Uso de Diferentes Tecnologias Educacionais Na Aprendizagem Conceitual Sobre o Sistema Miofuncional Orofacial [31] | 2019 | Brazil | en | Controlled randomized trial, Experimental |

| What Do Speech Pathology Students Gain from Virtual Patient Interviewing? A WHO International Classification of Functioning Disability and Health (ICF) Analysis [32] | 2020 | USA (Florida) New Zealand |

en | Observational, Descriptive |

| Virtual Patient Clinical Placements Improve Student Communication Competence [33] | 2020 | Australia UK |

en | Experimental |

| Effects of a Virtual Reality Dementia Experience on Graduate Communication Disorders Students’ Future Clinical Practice [34] | 2021 | USA (Kentucky) | en | Mixed methods (MA thesis) |

| Virtual Reality and Stuttering: A Tool for Experiential Learning in Preservice Speech Therapy Education [35] | 2022 | Belgium | en | Descriptive, Controlled randomized trial (poster presentation) |

| Speech Pathology Student Perspectives on Virtual Reality to Learn a Clinical Skill [36] | 2023 | Australia | en | Qualitative |

| Virtual Reality in Speech Therapy Training: Scenarios and Prototyping [37] | 2025 | Germany | en | Mixed methods, Design-based research |

| The Use of Information and Communication Technologies in Preparing Future Speech Therapists for Professional Practice [38] | 2025 | Uzbekistan | en | Mixed methods, Descriptive |

| Author(s) and Reference | VR type | VR characteristics | Population | Training purposes (and sub-fields) | Main outcomes and assessment methods |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (Williams, 2006) [25] | Immersive VR | CAVE projection-based technology |

Graduate SLP (and patients with communication disorders) | clinical skills (communication disorders) |

predicts increased competency and transfer of skills |

| (Sia et al., 2016) [26] | Non immersive VR | Virtual Patients (VPP); immersive VP simulation | Graduate SLP | clinical interviewing and clinical reasoning skills (stuttering) |

improvement of diagnosis competencies, reasoning and empathy; positive feedback |

| (Banszki et al., 2018)[27] | Non immersive VR | Virtual Patients; immersive VP simulation | Undergraduate (3rd year); CE point of view | communication and interpersonal skills | improvement of CE confidence and pedagogical skills as educator |

| (Moradi et al., 2018)[28] | Immersive VR | 3D glasses + monitor + gloves | SLP students (5th term) | oral organs assessment training | increase of students’ scores |

| (Towson et al., 2018) [29] | Semi immersive VR | mixed reality real-time simulator TeachLivE | Graduate SLP (3rd semester) | interpersonal collaborative communication skills when delivering information regarding a singular patient to different stakeholders | performance enhancement (2nd attempt);collaborative communication (Situation- Background- Assessment- Recommendation- Communication [SBAR-C]), high acceptability |

| (Carter, 2019) [30] | Non immersive VR | Virtual Patients; SimuCase; immersive VP simulation | Graduate SLP (2nd semester) | performances in the pediatric language disorders | improved clinical skills, high levels of improvement on the SCSI and CTCSD |

| (Rondon-Melo & Andrade, 2019) [31] | Non immersive VR | 2D interactive computer game (Anatesse 2.0); interactive 3D computational model (Primal Pictures) | Undergraduate students in Speech-Language and Hearing Sciences (SLHS) | anatomy and physiology of the orofacial myofunctional system | students’ performance in the knowledge assessment was similar, regardless of the learning method applied |

| (Miles et al., 2020) [32] | Non immersive VR | Virtual Patients | Graduate final year | interviewing skills using WHO-ICF (dysphagia) |

ICF respected, matching health literacy; VP interviews and findings as assessment |

| (Robinson et al., 2020) [33] | Non immersive VR | 3D (computerised) high fidelity digital patients; immersive VP simulation | Undergraduate SLP (2nd year) | communication skills (dementia) |

improved communication competence; CCIS, PRQ questionnaires as assessment |

| (Blaydes, 2021) [34] | VR (non specified) | non specified | Graduate SLP (2nd year) | understanding the importance of providing person-centered care (dementia) |

small margin for score improvement; increased levels of empathy |

| (Deman et al., 2022) [35] | Immersive VR | not specified | BA SLP students | understanding stuttering-related anxiety | students reported fear and physiological fear responses |

| (Kelly et al., 2023) [36] | Immersive VR | VR-OMA application; Oculus Quest 1 | Undergraduate SLP (2nd year) | clinical skills (oral musculature assessment) |

positive reaction of students’ intrinsic and extrinsic value for the training experience |

| (Gentile et al., 2025) [37] | Immersive VR | Meta Quest 3 applications implementing different scenarios | SLP | clinical skills (FEES, TTM, tDCS) |

prototype development to be assessed through usability, presence, acceptance, user experience |

| (Xonbabayeva Madinabonu Asqarjon kizi, 2025) [38] | VR (non specified) | not specified | SLP students and educators | practical skills | enhanced understanding, skill acquisition, confidence and competence; interviews assessment |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).