1. Introduction

Ulcerative colitis (UC) is a chronic, idiopathic inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) characterized by relapsing and remitting inflammation that primarily affects the colonic mucosa [

1]. The global burden of UC is increasing steadily, particularly among young adults aged 15–30, placing a significant strain on healthcare systems and patient quality of life [

2]. The etiology of UC remains multifactorial, involving complex interactions between genetic predisposition, environmental triggers, and dysregulated mucosal immune responses [

3]. Clinically, UC manifests with symptoms such as abdominal pain, diarrhea, rectal bleeding, and unintended weight loss, all of which contribute to long-term morbidity and decreased functional capacity [

4].

Animal models have long been indispensable for understanding UC pathogenesis and for evaluating the efficacy and safety of therapeutic agents prior to clinical trials. Among these, dextran sulfate sodium (DSS)-induced colitis models in rodents are the most widely employed due to their ease of use, low cost, and rapid onset of mucosal inflammation [

5]. DSS disrupts the epithelial barrier and induces colonic injury that mimics some pathological hallmarks of human UC, including diarrhea, weight loss, and mucosal ulceration [

6]. However, rodent models suffer from key anatomical and physiological limitations that hinder their translational relevance. Rodent colons are significantly shorter than those of humans (10–15 cm vs. ~150 cm), with thinner mucosal layers (50 μm vs. 500–1000 μm) and a markedly lower density of goblet cells. These differences impair the study of mucosal barrier integrity and immune-mucosal interactions, which are central to UC pathogenesis [

7,

8]. Moreover, DSS-induced lesions in rodents typically localize to the proximal colon, in contrast to the distal distribution seen in human UC. Rodent size also prohibits the use of longitudinal, non-invasive disease monitoring techniques, often necessitating terminal procedures for histological assessment [

9,

10].

To address these translational limitations, we developed a novel large animal model of UC using Sus scrofa minipigs (Micropigs®) [

11]. Minipigs have emerged as a valuable model in biomedical research due to their physiological, anatomical, and immunological similarities to humans. Their gastrointestinal tract closely resembles that of humans in terms of mucosal thickness, goblet cell density, crypt structure, and epithelial turnover, making them highly relevant for studying mucosal pathophysiology in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [

12]. Additionally, minipigs share approximately 98.5% genomic homology with humans and exhibit similar expression profiles of inflammatory cytokines and immune markers involved in IBD, such as TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6 [

13]. Importantly, their larger body size (~30 kg) allows the use of clinical-grade endoscopic equipment for real-time, non-invasive monitoring, enabling longitudinal assessments that are not feasible in rodent models [

14,

15]. This also facilitates repeated sampling and treatment within the same subject, reducing animal usage in accordance with the 3R (Replacement, Reduction, Refinement) principles [

16].

These advantages make minipigs an ideal platform for modeling chronic gastrointestinal inflammation, evaluating endoscopic scoring systems, and testing biologics or advanced drug delivery systems [

17]. In this study, we established a DSS-induced colitis model in minipigs by administering graded doses of DSS (0.2, 0.4, and 0.8 g/kg/day) over 7 days. This dosing strategy produced a reproducible, dose-dependent spectrum of colonic inflammation, ranging from mild mucosal edema to severe ulceration and transmural pathology. This model captures key histopathological, endoscopic, and clinical features of human UC more faithfully than existing rodent models. Moreover, it offers a robust platform for preclinical testing of therapeutic interventions, endoscopic technologies, and biomarker discovery in accordance with the promoting the use of large animal models for IBD research [

18].

2. Results

2.1. Clinical Signs, Body Weight Changes, Gross Autopsy Findings, and Colon Length

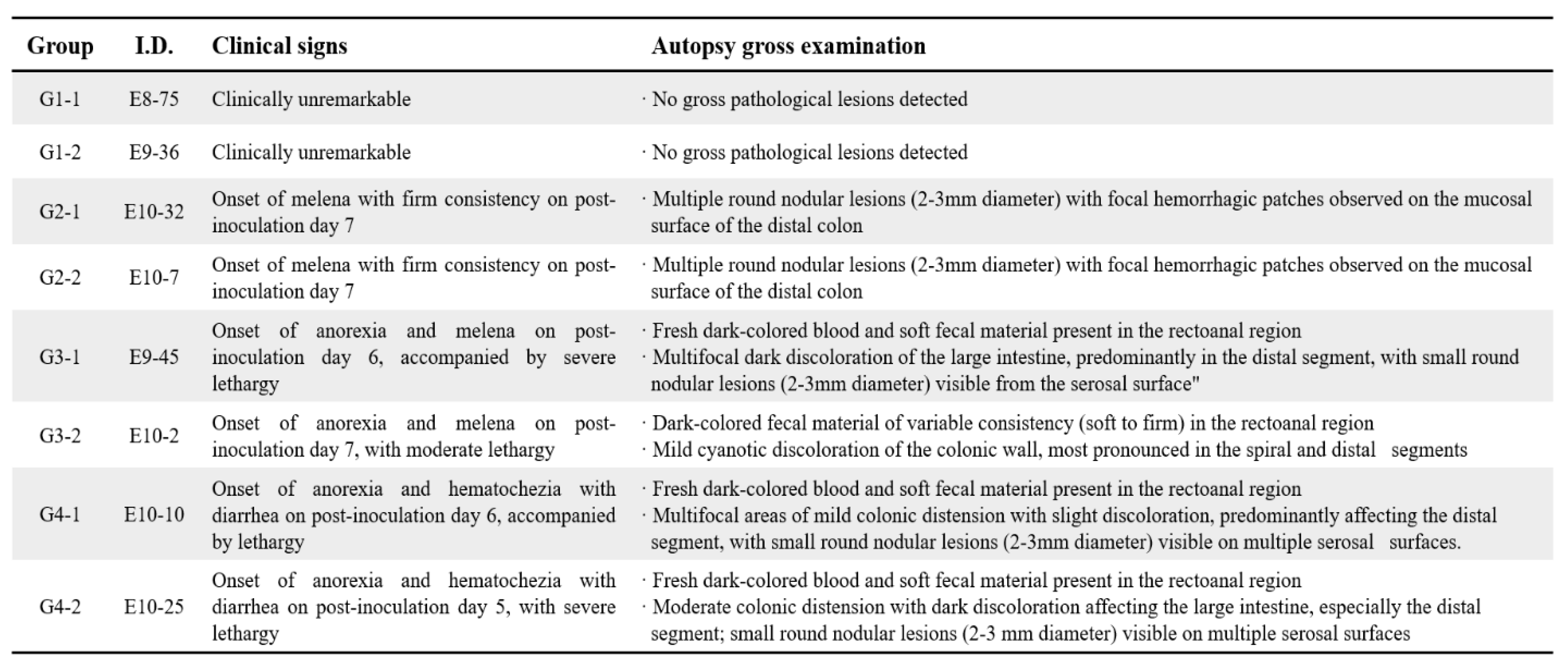

Clinical signs indicative of ulcerative colitis developed in a dose-dependent manner following DSS administration (

Table 1). Control animals (Group 1) remained asymptomatic throughout the experiment. Group 2 animals (0.2 g/kg/day DSS) began showing mild signs, such as melena with firm stool consistency, by day 7. In Group 3 (0.4 g/kg/day DSS), animals developed moderate clinical symptoms including anorexia, lethargy, and dark bloody stools from day 6 onward. Severe clinical manifestations, such as pronounced anorexia, lethargy, hematochezia, and diarrhea, appeared earliest and were most prominent in Group 4 (0.8 g/kg/day DSS) starting from day 5.

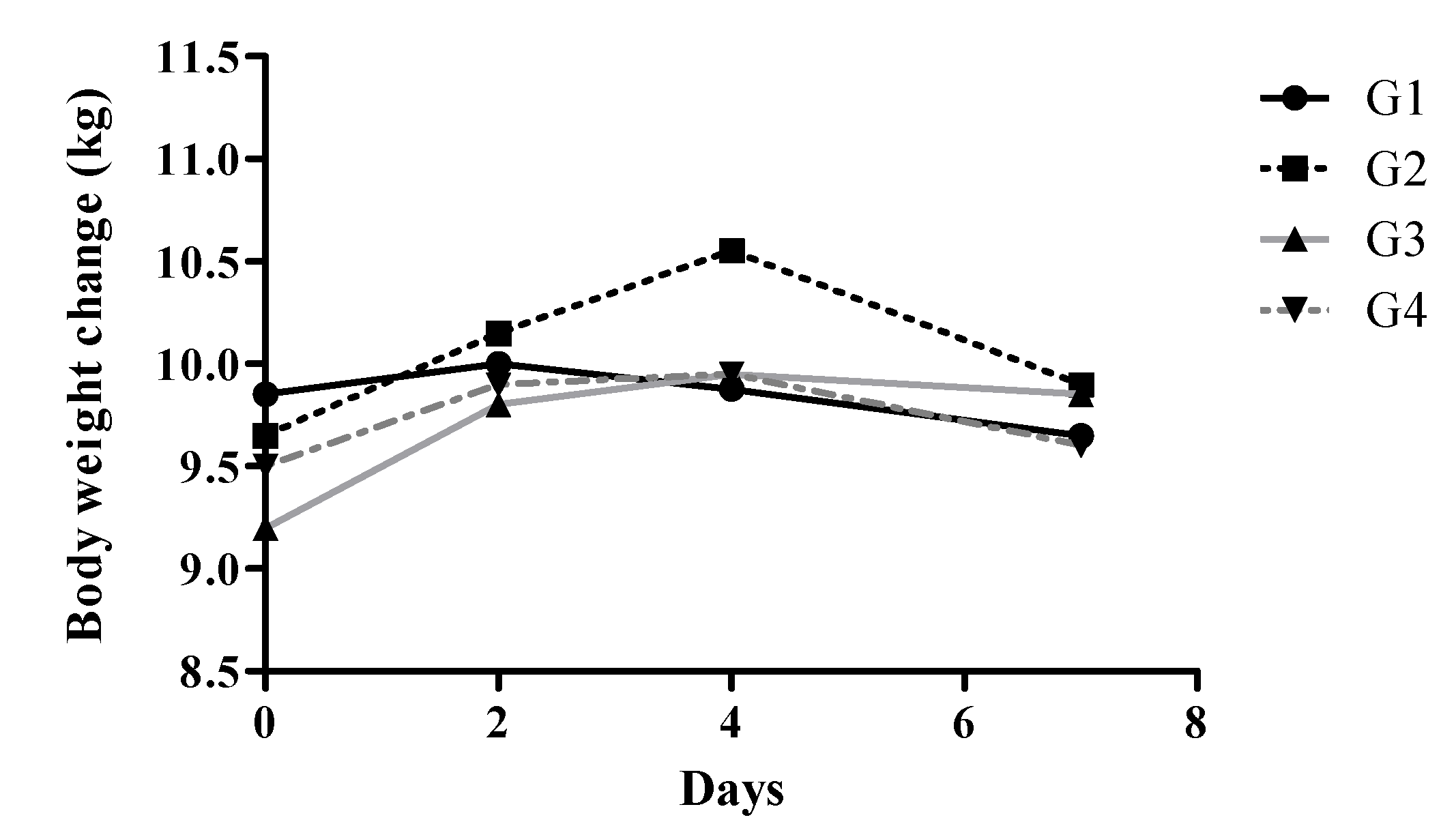

Body weight trajectories reflected these clinical manifestations (

Figure 1). Control animals maintained stable body weights throughout the experiment (±1.2%). In contrast, Group 2 exhibited an initial modest weight gain (approximately 3.2%), followed by a return to baseline by the end of the experiment. More pronounced weight changes were observed in Groups 3 and 4, characterized by initial weight gains peaking around day 3–4, followed by significant declines. Group 4 animals experienced the most substantial decrease, with an average loss of 12.1% from baseline by day 8 (p < 0.001 vs. Group 1).

Gross pathological findings corroborated clinical observations, revealing clear dose-dependent mucosal lesions upon autopsy (

Table 1). Group 2 exhibited multiple discrete nodular lesions (2–3 mm) and focal hemorrhagic patches primarily in the distal colon. Group 3 animals presented more extensive distal colon lesions with visible fresh dark blood and serosal nodules. Group 4 demonstrated severe colonic distension, dark discoloration, and discontinuous mucosal damage predominantly in distal segments.

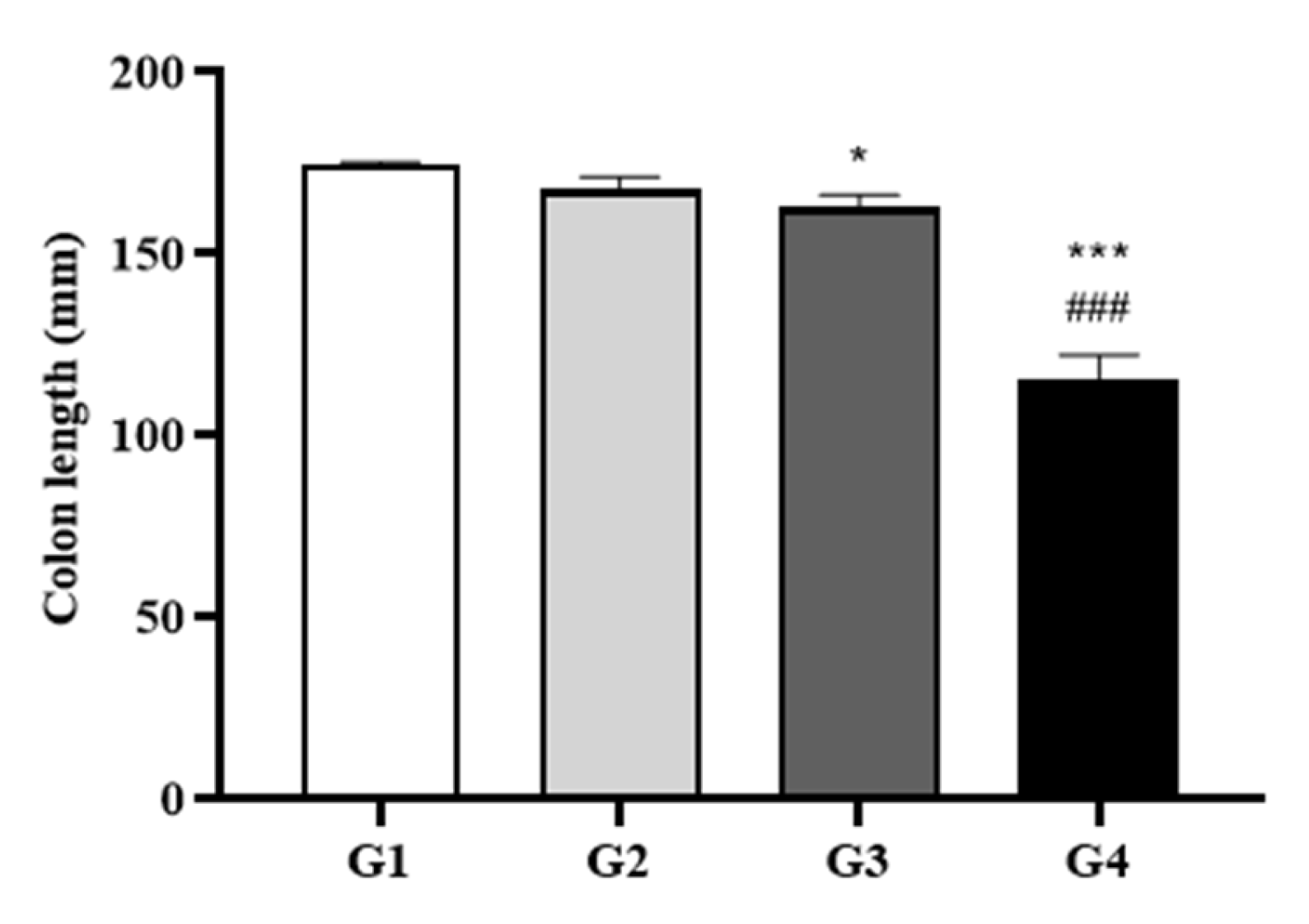

Colon length measurements further supported the clinical and gross pathological findings, with marked shortening observed in a dose-dependent manner (

Figure 2). Compared to the control, colonic shortening was mild in Group 2 (4.1%), moderate in Group 3 (7%), and severe in Group 4 (34%; p < 0.001 vs. Group 1). Notably, Group 4 also showed a statistically significant 31.3% reduction compared to Group 2 (p < 0.05).

Figure 2.

Colon Length Measurements. Colons were dissected before autopsy, and their lengths were measured without applying tension. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. Group 1; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. Group 2 by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

Figure 2.

Colon Length Measurements. Colons were dissected before autopsy, and their lengths were measured without applying tension. Data are presented as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001 vs. Group 1; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01, ###P < 0.001 vs. Group 2 by two-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test.

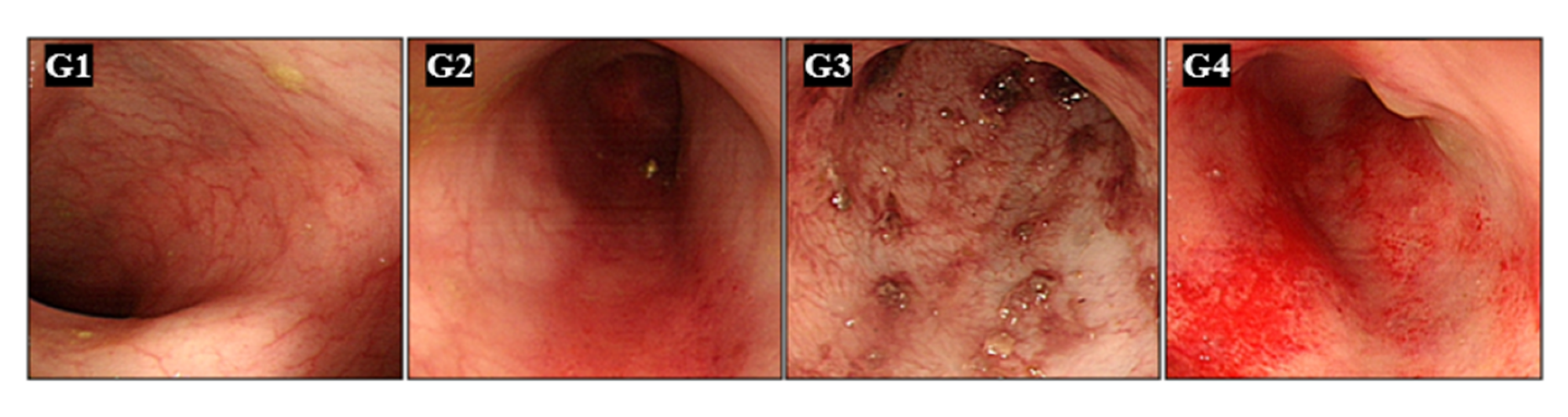

Figure 3.

Endoscopic Evaluation of Colonic Mucosa. Representative endoscopic images of the colonic mucosa from all groups, taken on day 7 after DSS treatment. High-resolution endoscopy enabled detailed evaluation of mucosal pathology. Minipigs were pre-medicated with intramuscular atropine sulfate (0.04 mg/kg), xylazine (2 mg/kg), and tiletamine-zolazepam (5 mg/kg). General anesthesia was maintained with 0.5–2.0% isoflurane in 70% nitrous oxide and 30% oxygen. A conventional gastroscope (GIF-Q260J; Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan) was used.

Figure 3.

Endoscopic Evaluation of Colonic Mucosa. Representative endoscopic images of the colonic mucosa from all groups, taken on day 7 after DSS treatment. High-resolution endoscopy enabled detailed evaluation of mucosal pathology. Minipigs were pre-medicated with intramuscular atropine sulfate (0.04 mg/kg), xylazine (2 mg/kg), and tiletamine-zolazepam (5 mg/kg). General anesthesia was maintained with 0.5–2.0% isoflurane in 70% nitrous oxide and 30% oxygen. A conventional gastroscope (GIF-Q260J; Olympus Optical Co., Tokyo, Japan) was used.

Figure 4.

Gross Morphology of Colon Samples. Following length measurement, the colons were photographed (lower panels). The distal segments were then dissected to expose and document the luminal surface (upper panels).

Figure 4.

Gross Morphology of Colon Samples. Following length measurement, the colons were photographed (lower panels). The distal segments were then dissected to expose and document the luminal surface (upper panels).

2.2. Endoscopic Evaluation of Ulcerative Colitis

High-resolution endoscopic evaluation provided detailed visualization of colonic mucosa at day 7, allowing clear assessment of inflammation severity. Group 1 displayed normal, intact mucosal architecture without signs of inflammation. In contrast, DSS-treated animals showed dose-dependent inflammatory changes, including mucosal edema, hemorrhages, erosions, and disrupted mucosal vascular patterns. Group 4 animals presented the most severe pathology, characterized by extensive erosions, pronounced mucosal edema, and substantial hemorrhagic areas. This dose-response correlation validated endoscopy as an effective real-time monitoring tool for UC progression.

Body weights were measured every two days in the morning before feeding, starting from the first day of DSS administration.

2.3. Macroscopic Pathology Post-Autopsy

Gross examination at necropsy confirmed endoscopic observations, further highlighting the severity of DSS-induced pathology in a dose-dependent manner. Group 4 colons exhibited pronounced mucosal swelling, extensive hemorrhagic damage, and numerous mucosal erosions. These macroscopic alterations closely matched the endoscopic findings, underscoring the robustness of the minipig model in capturing critical pathological features of human UC.

Table 2.

Histopathological examination scores of colons.

Table 2.

Histopathological examination scores of colons.

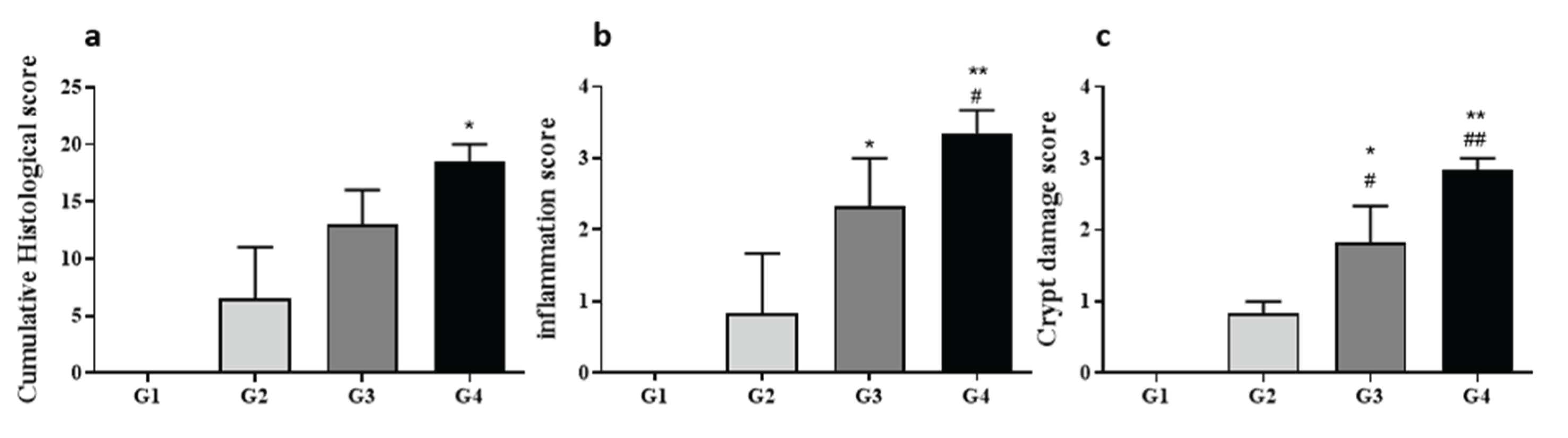

2.4. Histopathologic Analysis

Histological assessment of H&E-stained colon sections revealed clear, dose-dependent severity in histopathological alterations. Minimal inflammation and crypt damage were noted in control (Group 1) and mildly affected Group 2 animals. Conversely, Groups 3 and 4 showed significantly elevated histopathological scores across inflammation, crypt architectural distortion, ulceration, and edema parameters compared to both Groups 1 and 2 (p < 0.01). Group 4 demonstrated the highest cumulative histopathology scores, indicative of severe colitis, characterized by substantial crypt loss, pronounced mucosal ulceration, marked edema, and significant inflammatory infiltrates. These findings confirmed a robust correlation between DSS dosage and colitis severity, validating this model as highly representative of the pathological spectrum observed in human UC.

Figure 5.

Histological Scores and Representative Sections. Histological analysis was performed on three segments (proximal, mid, distal) of each colon. Tissues were fixed, paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and stained with H&E. Total histopathological scores (a) included subscores for inflammation (b), crypt damage (c), ulceration, and edema, assessed by three blinded evaluators. Data are shown as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. Group 1; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. Group 2 by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

Figure 5.

Histological Scores and Representative Sections. Histological analysis was performed on three segments (proximal, mid, distal) of each colon. Tissues were fixed, paraffin-embedded, sectioned, and stained with H&E. Total histopathological scores (a) included subscores for inflammation (b), crypt damage (c), ulceration, and edema, assessed by three blinded evaluators. Data are shown as mean ± SD. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01 vs. Group 1; #P < 0.05, ##P < 0.01 vs. Group 2 by two-way ANOVA with Sidak’s multiple comparisons test.

3. Discussion

3.1. Comparison with Rodent DSS Models

Rodent DSS models are widely used for UC research, typically using 2–5% DSS in drinking water over 5–7 days. However, these models primarily generate inflammation in the proximal colon, whereas our minipig model demonstrated distal colon-predominant pathology, aligning more closely with human UC [

19,

20,

21].

In our study, Group 4 minipigs (0.8 g/kg/day DSS) exhibited a 34% reduction in colon length, while rodents in similar models often show 15~25% shortening, largely confined to proximal segments [

22]. Moreover, histopathological scores in Group 4 minipigs reached the highest level across inflammation, crypt damage, and ulceration, consistent with advanced colitis seen in murine models, but with more pronounced tissue thickness and architectural complexity [

23,

24]. Clinically, rodents are limited in observable signs, typically monitored by weight loss and stool consistency [

25]. In contrast, minipigs showed graded clinical manifestations, including melena in Group 2, hematochezia in Group 3, and severe diarrhea, anorexia, and lethargy by Day 5 in Group 4—symptoms difficult to quantify in rodents but common in human UC [

26].

3.2. Correlation with Human Ulcerative Colitis Features

The pathophysiological response in minipigs, especially in Group 4, resembled moderate-to-severe human UC both macroscopically and microscopically [

27,

28]. Colonoscopy at Day 7 revealed extensive mucosal edema, erosions, and hemorrhages, paralleling findings in UCEIS scores of ≥6 in human patients [

29,

30]. Histological scoring confirmed this correlation: crypt loss, mucosal ulceration, and inflammatory infiltrates were significantly elevated in Group 3 and Group 4 minipigs. These findings parallel human colonic biopsies in UC flares, which also show crypt architectural distortion and basal lymphoplasmacytosis [

31]. Body weight loss—a key clinical metric—averaged 12.1% in Group 4, which is clinically meaningful, given that >10% weight loss in patients often correlates with hospitalization and steroid-refractory disease [

32]. Additionally, dose-dependent colon shortening and endoscopic vascular disruption mirror mucosal damage levels seen in moderate-to-severe UC patient cohorts [

33,

34].

3.3. Scientific and Translational Value of the Minipig UC Model

This study provides one of the first quantified validations of a dose-dependent, clinically traceable UC model in Sus scrofa minipigs. Its scalable disease severity, endoscopic accessibility, and physiological alignment with humans make it an ideal platform for: preclinical trials of new biologics, small molecules, and nutritional therapies; validation of endoscopic scoring systems in large animals; and development of mucosal healing and biomarker tracking protocols in IBD research [

35,

36,

37]. Moreover, minipigs allow repeated, within-subject assessment via real-time high-resolution endoscopy, improving statistical power and reducing animal numbers, in line with 3R principles [

14].

3.4. Limitations and Future Directions

Despite its strengths, this model has limitations. The sample size (n=2 per group), though acceptable in large animal pilot studies, restricts broad statistical interpretation. In addition, while we achieved gross and histological fidelity, molecular-level confirmation (e.g., cytokine panels, transcriptomics) was not performed.

Furthermore, while acute colitis was well-modeled, future studies should establish chronic and relapsing models to reflect the full clinical spectrum of UC. Genetic susceptibility (e.g., IL-23R or HLA-DQA1 mutations) and microbiota influences remain unexplored but could be incorporated via CRISPR-editing and fecal transplant protocols. Lastly, integration of AI-assisted endoscopic scoring and imaging biomarkers may enhance reproducibility and translational rigor, positioning this model as a gold standard for large-animal IBD research.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Ethical statement

All animal procedures were reviewed and approved by the Animal Research Committee of APURES Co., Ltd. (IRB File No. APURES-IACUC-201021-001) and conducted in accordance with institutional guidelines and the ARRIVE 2.0 reporting standards.

4.2. Animals and Housing

Eight male Micropigs® (Sus scrofa), each weighing less than 30 kg and aged 6–8 months, were used in this study. Animals were housed in a specific-pathogen-free (SPF) facility maintained at 22 ± 3°C and 50 ± 10% relative humidity, with a 12-hour light/dark cycle (200–300 lux). Standard commercial swine feed (Purina® Minipig Diet) and water were provided ad libitum. All animals underwent a one-week acclimatization period prior to experimental procedures, during which health status was monitored daily.

4.3. Chemicals and Reagents

Dextran sulfate sodium (DSS; colitis grade, molecular weight 36–50 kDa, Cat. No. 160110, MP Biomedicals, LLC, OH, USA) was used to induce colitis. All other chemicals were of analytical grade and sourced from standard suppliers.

4.4. Experimental Design and DSS Administration

Following acclimatization, animals were randomly assigned to four groups (n = 2 per group). Group 1 (control): No DSS administration. Group 2: 0.2g/kg/day DSS, mixed in feed/water. Group 3: 0.4 g/kg/day DSS, mixed in feed/water. Group 4: 0.8 g/kg/day DSS, mixed in feed/water. DSS was freshly prepared daily as a 2% (w/v) solution in autoclaved water and administered for 7 consecutive days. DSS intake was monitored to ensure accurate dosing.

4.5. Endoscopic Examination

On day 7, all animals underwent endoscopic evaluation under general anesthesia. Premedication included intramuscular atropine sulfate (0.04 mg/kg), xylazine (2 mg/kg), and tiletamine-zolazepam (5 mg/kg). General anesthesia was maintained with 0.5–2.0% isoflurane in 70% nitrous oxide and 30% oxygen. A conventional gastroscope (GIF-Q260J; Olympus Optical Co. Ltd., Tokyo, Japan; 9.8 mm diameter) was used to visualize the entire colon. Mucosal lesions were graded according to the Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS), and high-resolution images were captured at standardized intervals.

4.6. Necropsy and Gross Pathological Assessment

After endoscopy, animals were euthanized humanely. The entire colon was dissected along the antimesenteric border without tension, and its length was measured. Gross pathological findings, including edema, hemorrhage, ulceration, and nodular lesions, were documented and photographed using a digital camera (Canon EOS 5D Mark IV) with scale bars for reference.

4.7. Histopathological Analysis

Colon samples were fixed in 10% neutral-buffered formalin for 24 hours, embedded in paraffin, sectioned at 4–5 μm thickness, and stained with hematoxylin and eosin (H&E). Three regions per colon (proximal, mid, distal) were evaluated. Histopathological scoring was performed independently by three board-certified veterinary pathologists, blinded to group allocation, using standardized criteria for inflammation, crypt damage, ulceration, and edema as following.

4.8. Statistical Anlysis

Due to limited sample size (n=2/group), statistical analysis was primarily exploratory and used to identify consistent trends rather than definitive significance. All data are presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 9.0. Group comparisons were conducted using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey’s multiple comparisons test for continuous variables, and Kruskal-Wallis with Dunn’s post hoc test for categorical data. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05 (two-tailed). Power analysis indicated that the sample size provided 80% power to detect a 30% difference in colon length (α = 0.05).

Author Contributions

H.W.P prepared all experimental results and draft manuscript. W.K.L. designed and supervised this study as a corresponding author. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by a grant from the Next-Generation Bio-Green 21 Program (Project No. PJ01323001), Rural Development Administration, Republic of Korea.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Animal studies were approved by the Animal Research Committee of APURES Co., Ltd., and were maintained and performed according to the guidelines of the Animal Facility (IRB File No. APURES-IACUC-201021-001).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Gajendran, M.; Loganathan, P.; Jimenez, G.; Catinella, A.P.; Ng, N.; Umapathy, C.; Ziade, N.; Hashash, J.G. A Comprehensive Review and Update on Ulcerative Colitis. Dis. Mon. 2019, 65, 100851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hracs, L.; Windsor, J.W.; Gorospe, J.; Cummings, M.; Coward, S.; Buie, M.J.; et al. Global Evolution of Inflammatory Bowel Disease across Epidemiologic Stages. Nature 2025, 642, 458–466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Khor, B.; Gardet, A.; Xavier, R.J. Genetics and Pathogenesis of Inflammatory Bowel Disease. Nature 2011, 474, 307–317. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ordás, I.; Eckmann, L.; Talamini, M.; Baumgart, D.C.; Sandborn, W.J. Ulcerative Colitis. Lancet 2012, 380, 1606–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Low, D.; Nguyen, D.D.; Mizoguchi, E. Animal Models of Ulcerative Colitis and Their Application in Drug Research. Drug Des. Devel. Ther. 2013, 7, 1341–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichele, D.D.; Kharbanda, K.K. Dextran Sodium Sulfate Colitis Murine Model: An Indispensable Tool for Advancing Our Understanding of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Pathogenesis. World J. Gastroenterol. 2017, 23, 6016–6029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ermund, A.; Gustafsson, J.K.; Hansson, G.C.; Keita, A.V. Mucus Properties and Goblet Cell Quantification in Mouse, Rat and Human Ileal Peyer's Patches. PLoS One 2013, 8, e83688. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ottman, N.; Smidt, H.; de Vos, W.M. The Function of Our Microbiota: Who Is Out There and What Do They Do? Front. Cell. Infect. Microbiol. 2012, 2, 104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kitajima, S.; Takuma, S.; Morimoto, M. Histological Analysis of Murine Colitis Induced by DSS of Different Molecular Weights. Exp. Anim. 2000, 49, 9–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wirtz, S.; Neufert, C.; Weigmann, B.; Neurath, M.F. Chemically Induced Mouse Models of Intestinal Inflammation. Nat. Protoc. 2007, 2, 541–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pyao, Y.; Memon, A.; Ko, T.H.; Choi, H.S.; Bang, B.W.; Lee, W.K. Gastric Ulcer Model in Mini-Pig. Plast. Surg. Mod. Tech. 2018, PSMT–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rose, E.C.; Blikslager, A.T.; Ziegler, A.L. Porcine Models of the Intestinal Microbiota: The Translational Key to Understanding How Gut Commensals Contribute to Gastrointestinal Disease. Front. Vet. Sci. 2022, 9, 834598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Ding, X.; Wu, G.; Yin, Y. Pig Models on Intestinal Development and Therapeutics. Amino Acids 2017, 49, 2099–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parra-Blanco, A.; Arnau, M.R.; Nicolás-Pérez, D.; Gimeno-García, A.Z.; González, N.; Díaz-Acosta, J.A.; Jiménez, A.; Quintero, E. Endoscopic Submucosal Dissection Training with Pig Models in a Western Country. World J. Gastroenterol. 2010, 16, 2895–2900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ernst, M.; Preaudet, A.; Putoczki, T. Non-Invasive Assessment of the Efficacy of New Therapeutics for Intestinal Pathologies Using Serial Endoscopic Imaging of Live Mice. J. Vis. Exp. 2015, 97, e52383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, W.M.S.; Burch, R.L. The Principles of Humane Experimental Technique; Universities Federation for Animal Welfare: Wheathampstead, UK, 1959. [Google Scholar]

- Qiu, S.; Jia, J.; Xu, B.; Wu, N.; Cao, H.; Xie, S.; Cui, J.; Ma, J.; Pan, Y.H.; Yuan, X.B. Development and Evaluation of an Autism Pig Model. Lab Anim. 2024, 53, 376–386. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rossi, R.; Mainardi, E. Prebiotics and Probiotics Supplementation in Pigs as a Model for Human Gut Health and Disease. Biomolecules 2025, 15, 665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chassaing, B.; Aitken, J.D.; Malleshappa, M.; Vijay-Kumar, M. Dextran Sulfate Sodium (DSS)-Induced Colitis in Mice. Curr. Protoc. Immunol. 2014, 104, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yan, Y.; Kolachala, V.; Dalmasso, G.; Nguyen, H.; Laroui, H.; Sitaraman, S.V.; Merlin, D. Temporal and Spatial Analysis of Clinical and Molecular Parameters in Dextran Sodium Sulfate Induced Colitis. PLoS One 2009, 4, e6073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kobayashi, T.; Siegmund, B.; Le Berre, C.; Wei, S.C.; Ferrante, M.; Shen, B.; Bernstein, C.N.; Danese, S.; Peyrin-Biroulet, L.; Hibi, T. Ulcerative Colitis. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers 2020, 6, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivathi, V.; Doppalapudi, M.; Yadala, R.K.; Banothu, A.; Anumolu, V.K.; Veera, H.D.D.; Debbarma, B. Visnagin Treatment Attenuates DSS-Induced Colitis by Regulating Inflammation, Oxidative Stress, and Mucosal Damage. Front. Vet. Sci. 2025, 12, 1558092. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kozlowski, C.; Jeet, S.; Beyer, J.; Guerrero, S.; Lesch, J.; Wang, X.; Devoss, J.; Diehl, L. An Entirely Automated Method to Score DSS-Induced Colitis in Mice by Digital Image Analysis of Pathology Slides. Dis. Model. Mech. 2013, 6, 855–865. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Ding, S.; Luo, M.; Chen, J.; Zhang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Li, A.; Zhong, S.; Ding, J. Differential Diagnosis of Acute and Chronic Colitis in Mice by Optical Coherence Tomography. Quant. Imaging Med. Surg. 2022, 12, 3193–3203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, Y.; Kolachala, V.; Dalmasso, G.; Nguyen, H.; Laroui, H.; Sitaraman, S.V.; Merlin, D. Temporal and Spatial Analysis of Clinical and Molecular Parameters in Dextran Sodium Sulfate Induced Colitis. PLoS ONE 2009, 4, e6073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kawakatsu, S.; Zhu, R.; Zhang, W.; Tang, M.T.; Lu, T.; Quartino, A.L.; Kagedal, M. A Longitudinal Model for the Mayo Clinical Score and Its Sub-Components in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. J. Pharmacokinet. Pharmacodyn. 2022, 49, 179–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, S.; Bai, M.; Shu, Q.; Liu, Z.; Shao, Y.; Xu, K.; Xiong, X.; Liu, H.; Li, Y. Modulating Effect of Paeonol on Piglets with Ulcerative Colitis. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 846684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- DeRoche, T.C.; Xiao, S.Y.; Liu, X. Histological Evaluation in Ulcerative Colitis. Gastroenterol. Rep. (Oxf.) 2014, 2, 178–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, S.M.; Baek, D.H. A Review of Colonoscopy in Intestinal Diseases. Diagnostics 2023, 13, 1262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pop, C.S.; Filip, P.V.; Diaconu, S.L.; Matei, C.; Furtunescu, F. Correlation of Biomarkers with Endoscopic Score: Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS) in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis in Remission. Medicina 2021, 57, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pai, R.K.; Hartman, D.J.; Rivers, C.R.; Regeuiro, M.; Schwartz, M.; Binion, D.G.; Pai, R.K. Complete Resolution of Mucosal Neutrophils Associates with Improved Long-Term Clinical Outcomes of Patients with Ulcerative Colitis. Clin. Gastroenterol. Hepatol. 2020, 18, 2510–2517. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langan, R.C.; Gotsch, P.B.; Krafczyk, M.A.; Skillinge, D.D. Ulcerative Colitis: Diagnosis and Treatment. Am. Fam. Physician 2007, 76, 1323–1330. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Travis, S.P.L.; Schnell, D.; Krzeski, P.; Abreu, M.T.; Altman, D.G.; Colombel, J.-F.; Feagan, B.G.; et al. Developing an Instrument to Assess the Endoscopic Severity of Ulcerative Colitis: The Ulcerative Colitis Endoscopic Index of Severity (UCEIS). Gut 2012, 61, 535–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergqvist, V.; Gedeon, P.; Hertervig, E.; Marsal, J. A New Simple Endoscopic Score for Ulcerative Colitis – the SES-UC. Front. Gastroenterol. 2024, 3, 1468394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yin, L.; Yang, H.; Li, J.; Li, Y.; Ding, X.; Wu, G.; Yin, Y. Pig Models on Intestinal Development and Therapeutics. Amino Acids 2017, 49, 2099–2106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gonzalez, L.M.; Williamson, I.; Piedrahita, J.A.; Blikslager, A.T.; Magness, S.T. Cell Lineage Identification and Stem Cell Culture in a Porcine Model for the Study of Intestinal Epithelial Regeneration. PLoS One 2013, 8, e66465. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [PubMed Central]

- Summers, K.M.; Bush, S.J.; Wu, C.; Su, A.I.; Muriuki, C.; Clark, E.L.; Finlayson, H.A.; Eory, L.; Waddell, L.A.; Talbot, R.; Archibald, A.L.; Hume, D.A. Functional Annotation of the Transcriptome of the Pig, Sus scrofa, Based Upon Network Analysis of an RNAseq Transcriptional Atlas. Front. Genet. 2020, 10, 1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).