Chapter 1: Introduction

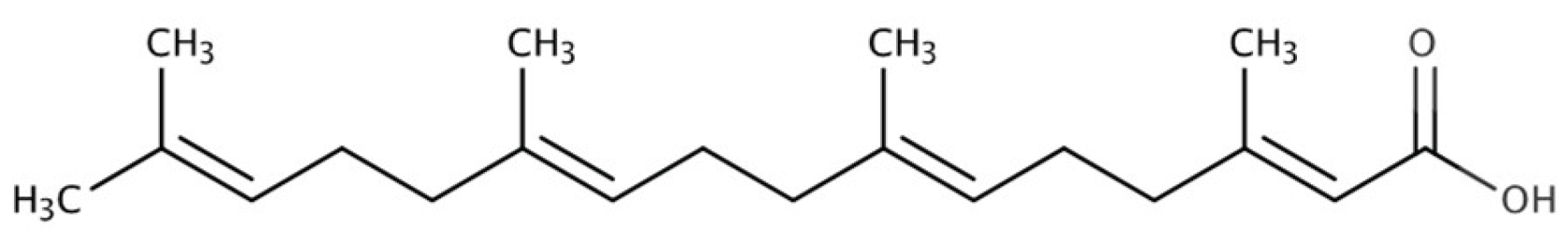

Geranylgeranoic acid (GGA) is an acyclic diterpenoid compound that was originally developed as a synthetic ligand for nuclear retinoic acid receptors (RAR and RXR)[

1,

2] and has promising effects on the differentiation of human hepatoma cell lines (

Figure 1)[

3].

In contrast to natural retinoids, GGA induces cell death in hepatoma cells at micromolar concentrations[

4], suggesting unique biological mechanisms and potential therapeutic implications for GGA. Although initially regarded as a pharmacologically active compound, GGA was later identified as a naturally occurring compound in certain plant species. In the early 2000s, Shidoji and Ogawa reported the presence of GGA in turmeric (

Curcuma longa)[

4], highlighting its dual identity as both a synthetic drug candidate and a naturally derived nutritional component. This discovery significantly broadened the scientific interest in GGA, shifting its context from pharmacology to one that encompasses nutrition, metabolism, and preventive medicine. The recognition of GGA as a food-derived compound prompted further investigation into its bioavailability in humans.

Oral intake of turmeric-based supplements has been shown to elevate GGA concentrations in human serum, demonstrating that dietary GGA is absorbable and may contribute to circulating levels[

5].

Subsequently, the endogenous biosynthesis of GGA in mammals was demonstrated[

6]. Using stable isotope-labeled mevalonate (MVA), GGA was shown to be synthesized via the MVA pathway with downstream conversion from geranylgeranyl pyrophosphate (GGPP) to geranylgeraniol (GGOH)[

6]. Enzymatic studies have revealed that monoamine oxidase B (MAOB) and cytochrome P450 3A4 (CYP3A4) play pivotal roles in GGA metabolism within hepatic cells[

7,

8].

Most intriguingly, in a murine model of spontaneous hepatocarcinogenesis, a decline in hepatic GGA levels was observed in old mice[

9]. Oral supplementation with GGA or its 4,5-didehdro derivative initiated in mid-life significantly suppressed hepatocellular carcinoma incidence, suggesting a potential preventive role for GGA in age-related tumorigenesis[

9,

10]. These findings imply that both endogenous GGA synthesis and dietary GGA intake may be critical factors for maintaining hepatic health during aging.

In recent years, further investigations have identified GGA in commonly consumed plant-based foods such as seeds, nuts, and legumes. These findings support the hypothesis that GGA can be acquired endogenously and through habitual dietary intake, offering practical avenues for nutritional intervention (Tabata Y, unpublished data, under review).

This review aims to comprehensively summarize the current understanding of GGA, focusing on its dual origin, both endogenous and dietary, its biological activities, and its potential role in tumor prevention. By integrating historical findings with recent analytical data, we propose new perspectives on the physiological relevance of GGA and its application in functional-food science.

Chapter 2: Plant-Derived GGA: Discovery, Biosynthesis, and Dietary Relevance

GGA was originally developed as a synthetic compound, but its discovery in plants marked a pivotal shift in scientific relevance. In 2004, Shidoji and Ogawa reported the presence of GGA in turmeric (

Curcuma longa), a spice widely used in traditional Asian medicine, such as Ayurveda[

4]. Using high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled with mass spectrometry, they confirmed that GGA is a naturally occurring constituent of the lipid fraction of turmeric[

4]. This finding redefined GGA from being merely a pharmacological agent to a naturally derived compound with potential dietary significance. Structurally, GGA is a linear C

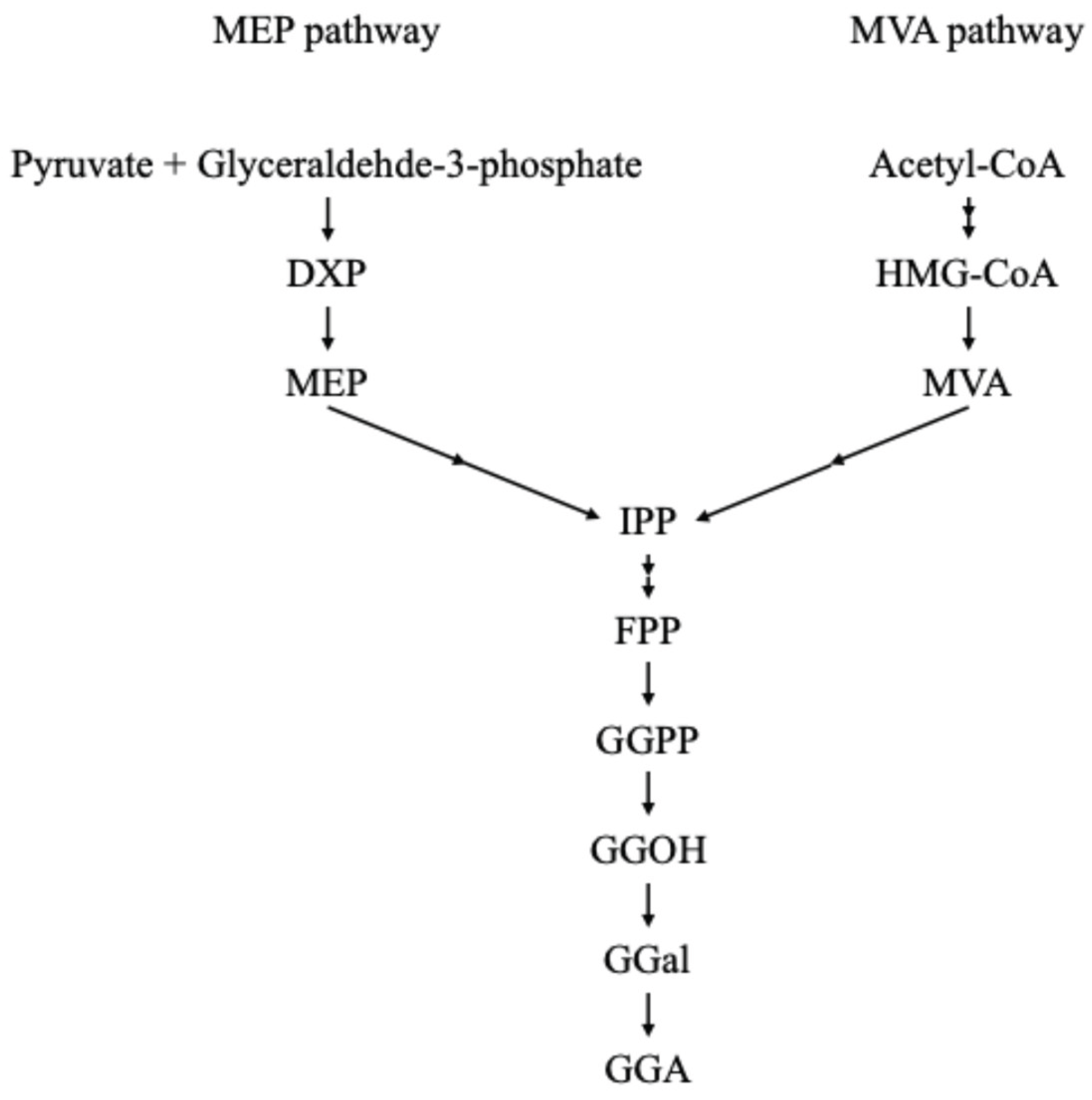

20 isoprenoid with a terminal carboxylic acid group. It is hypothesized to be synthesized in plants from GGPP, a common intermediate in both the MVA and methylerythritol phosphate (MEP) pathways. The proposed biosynthetic steps involve the dephosphorylation of GGPP to GGOH, oxidation to geranylgeranial (GGal), and further oxidation to GGA (

Figure 2). Although the specific enzymes involved in this conversion in plants remain to be identified, the pathway is presumed to parallel mammalian biosynthesis.

The discovery of GGA in turmeric has prompted investigations into its bioavailability in humans. In a study by Mitake et al., healthy participants ingested turmeric-based supplements, and blood samples revealed increased serum GGA levels post-ingestion[

5]. These results confirm that plant-derived GGA can be absorbed by the human gastrointestinal tract and contributes to systemic GGA levels. Subsequent screening efforts have expanded the list of foods containing GGA beyond turmeric. Although unpublished at the time of writing, recent analytical data suggest that GGA may also be present in commonly consumed plant-based foods, such as almonds, azuki beans, and pistachios. These findings indicate a broader distribution of GGA across the plant kingdom, particularly in lipid-rich tissues such as seeds and legumes. While quantitative details remain under peer review, these preliminary results support the concept that habitual dietary intake could significantly contribute to maintaining physiological GGA levels, especially in aging individuals or those with compromised hepatic synthesis.

In summary, the identification of GGA in both traditional medicinal plants and everyday foods underscores its dual significance as both a metabolic intermediate and dietary component. The recognition of its dietary availability opens new avenues for nutritional interventions aimed at sustaining GGA homeostasis and preventing liver-related diseases, such as HCC. Future studies should aim to expand the food composition database for GGA, assess interindividual variability in its absorption and metabolism, and explore the long-term health implications of GGA-rich diets.

Chapter 3: Endogenous Biosynthesis of GGA in Mammals

In addition to its presence in certain plants, GGA is also endogenously synthesized in mammalian cells. The first unequivocal evidence came from isotope-labeling experiments in which cultured cells were incubated with [

13C]-labeled mevalonolactone[

6]. The detection of labeled GGA in cellular lipid extracts confirmed that GGA is biosynthesized from mevalonate via the MVA pathway.

This biosynthetic route in mammals corresponds to the right half of the schematic shown in

Figure 2, proceeding from GGPP through GGOH and GGal to GGA. While

Figure 2 outlines the broader isoprenoid biosynthesis shared between plants and animals, mammalian cells rely exclusively on the MVA pathway for isoprenoid biosynthesis.

Although the specific enzymes responsible for each oxidative step were initially unclear, subsequent studies identified MAOB as a central enzyme in the conversion of GGOH to GGA. Pharmacological inhibition and gene knockdown experiments in human hepatoma cells demonstrated that the loss of MAOB activity significantly reduced intracellular GGA levels[

7].

Interestingly, MAOB knockout in Hep3B cells did not completely abolish GGA synthesis[

7]. Further investigation revealed that CYP3A4 partially compensated for this by sustaining basal levels of GGA production[

8]. However, this CYP3A4-mediated pathway appears to be limited and fails to restore GGA to physiological levels when MAOB activity is impaired. These observations indicate that CYP3A4 lacks the catalytic capacity and regulatory flexibility of MAOB in maintaining GGA homeostasis.

The combined action of MAOB and CYP3A4 establishes a robust and hierarchically organized mechanism for endogenous GGA biosynthesis in hepatic cells. MAOB functions as the primary enzyme under physiological conditions, whereas CYP3A4 serves as a secondary compensatory pathway that cannot fully substitute for MAOB when MAOB activity is impaired[

7,

8].

These findings establish the metabolic framework for endogenous GGA regulation, setting the stage for exploring how its dysregulation contributes to age-related liver pathology, as discussed in the following chapter. A recent preprint further elaborates on this hepatic biosynthetic network, proposing an age-dependent metabolic shift from MAOB to CYP3A4 activity and its potential role in liver cancer susceptibility [

11].

Chapter 4: Age-Dependent Decline of Hepatic GGA and Its Role in Hepatocarcinogenesis

Building on the metabolic framework outlined in the previous chapter, this section explores how age-related changes in GGA levels may contribute to liver tumorigenesis. Specifically, we examine longitudinal alterations in hepatic GGA concentrations and assess their implications for hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) development in aging models.

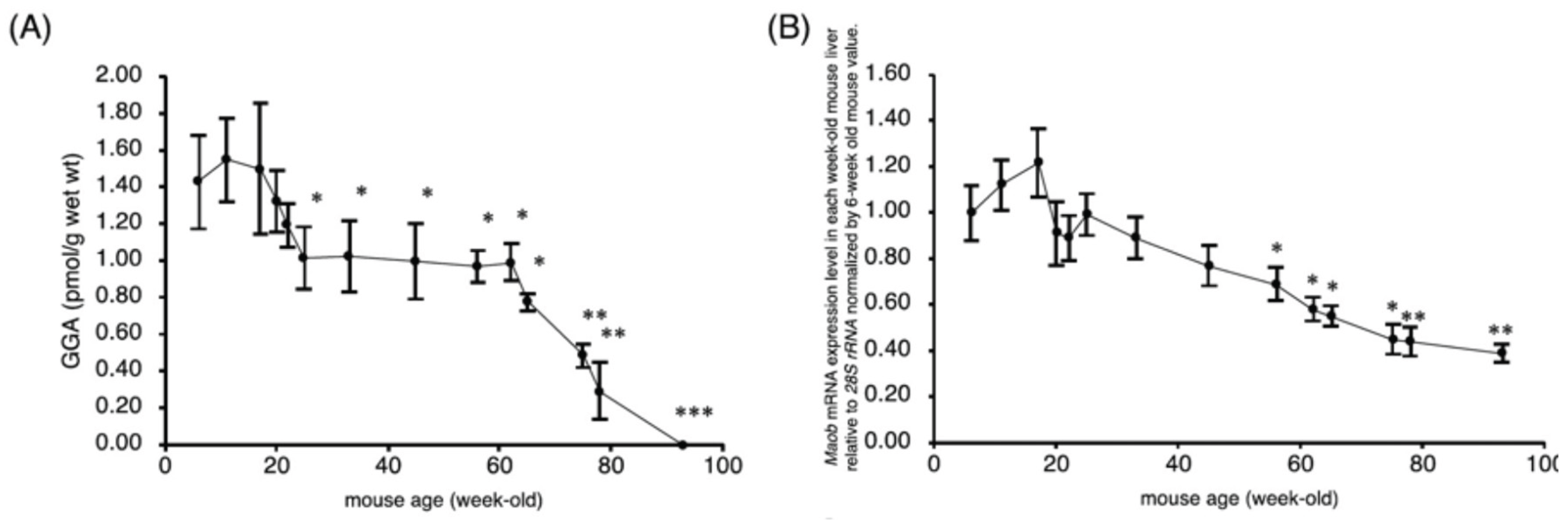

In studies using C3H/HeN mice, a strain genetically predisposed to spontaneous hepatoma formation, longitudinal measurements of hepatic GGA content revealed a remarkable age-dependent pattern. Young adult mice (3–12 months) maintained relatively stable GGA levels. However, beginning at approximately 18 months of age, a progressive decline was observed, culminating in near-complete depletion of hepatic GGA by 23 months[

9]. This temporal decline coincided with the typical onset of liver tumor development in the C3H/HeN strain, suggesting a possible causal relationship between reduced GGA levels and hepatocarcinogenesis (

Figure 3)[

9].

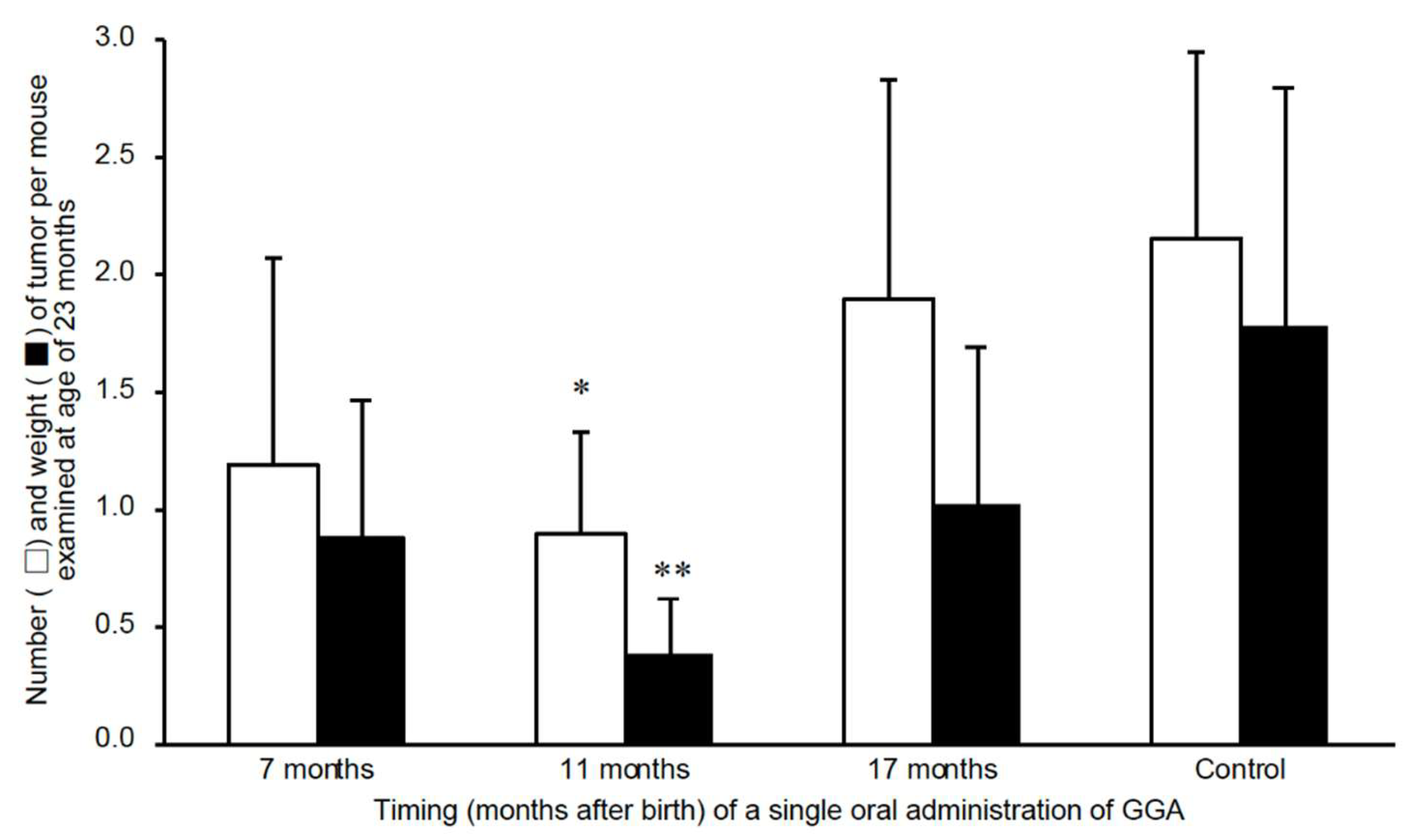

To investigate whether age-associated decline in GGA contributes to tumor development, a dietary intervention study was conducted. Oral GGA administration was initiated at 11 months of age, preceding the period of sharp endogenous GGA reduction. Remarkably, this supplementation significantly reduced the incidence of hepatocellular carcinoma at 23 months compared to that in untreated control mice (

Figure 4)[

9]. These findings provide compelling evidence that GGA exerts a preventive effect on liver tumorigenesis, particularly in the context of aging.

The mechanisms underlying this preventive effect have not yet been fully elucidated; however, several hypotheses have been proposed. One plausible explanation for this is that GGA selectively induces cell death in pre-malignant or transformed hepatocytes, thereby eliminating potential tumor progenitor cells[

4]. In parallel with the age-related decline in hepatic GGA levels, the expression levels of GGA-metabolizing enzymes, such as MAOB and CYP3A4, also exhibit age-dependent changes[

11]. This observation suggests that the regulatory network governing GGA biosynthesis and clearance is intricately linked to hepatic aging process. Whether these enzymatic alterations are a cause or consequence of GGA depletion remains an open question; nonetheless, they underscore the complex interplay between metabolic aging and tumor suppression.

From a translational perspective, age-related decline in hepatic GGA levels represents both a biomarker of vulnerability and a potential target for nutritional or pharmacological interventions. The ability of dietary GGA supplementation to suppress spontaneous HCC development in aged mice highlights its potential as a preventive agent in humans, particularly in populations at an elevated risk of liver cancer due to aging or chronic liver conditions.

In conclusion, the decline in hepatic GGA levels with age appears to be a critical event in the natural course of hepatocarcinogenesis. Maintaining adequate GGA levels, either through continued endogenous synthesis or dietary intake, may be a promising strategy for preserving liver health and preventing age-associated HCC.

Chapter 5: Conclusion

GGA is a unique bioactive lipid with dual identity. Initially developed as a synthetic compound with anticancer potential[

1,

2,

3,

12,

13], it was later identified as a naturally occurring metabolite in plants and mammals[

4]. Over the past two decades, significant progress has been made in elucidating its biosynthetic pathways[

6,

7,

8], biological functions[

5,

11,

14] and dietary sources[

4].

This review summarizes the key findings regarding the chemical identity of GGA, its occurrence in turmeric[

4] and other plant-derived foods, its absorption and bioavailability in humans[

5,

9,

10,

14], and its endogenous synthesis via the mevalonate pathway[

6,

7,

8]. The involvement of hepatic enzymes, particularly MAOB and CYP3A4, in maintaining GGA homeostasis underscores the metabolic complexity and physiological relevance of these compounds.

Of particular interest are the findings that link age-related depletion of hepatic GGA with the onset of spontaneous hepatocarcinogenesis in mice, as well as the preventive effects observed with dietary GGA supplementation[

9]. These results suggest that both endogenous synthesis and dietary intake are essential for sustaining GGA’s protective functions of GGA, especially in aging populations.

Although quantitative data remain under peer review, recent evidence indicating the presence of GGA in common foods such as almonds, azuki beans, and pistachios suggests broader dietary distribution. This opens new avenues for nutritional strategies aimed at maintaining physiological GGA levels and preventing age-related diseases.

From a translational standpoint, GGA-enriched diets or supplements may serve as practical, non-pharmacological interventions for health promotion, particularly in aging populations. Beyond hepatic health, emerging hypotheses suggest that GGA may also function in other physiological contexts. Recent work has proposed its role as a lipid mediator in male reproductive physiology, potentially affecting sperm maturation and offspring viability[

15]. These findings suggest that GGA’s physiological relevance may extend systemically across multiple tissues.

Further research is needed to clarify the molecular mechanisms underlying GGA’s effects of GGA, especially its potential involvement in regulated cell death pathways, such as pyroptosis[

16]. In parallel, comprehensive dietary surveys and human studies are essential to establish the intake thresholds, absorption dynamics, and inter-individual variability in GGA metabolism.

In conclusion, GGA is emerging as a novel functional compound at the intersection of nutrition, metabolism and preventive medicine. Its dual origin highlights the need for integrated approaches that combine biochemical, nutritional, and clinical research to fully realize its health-promoting potential in humans.

Author Note

This mini review was developed based on a previously published Japanese article written by the same author (Tabata,

Vitamins Japan, 2023[

17]). The present version focuses on the dual origin of geranylgeranoic acid (GGA) and its potential role in hepatocarcinogenesis prevention. Mechanistic discussions, including GGA-induced cell death pathways, are excluded here and will be addressed in a future comprehensive review. This English version has been extensively revised and updated to incorporate the latest findings, including new insights from dietary analyses and age-dependent metabolic regulation of GGA.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were generated or analyzed in this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Muto, Y.; Moriwaki, H.; Ninomiya, M.; Adachi, S.; Saito, A.; Takasaki, K.T.; Tanaka, T.; Tsurumi, K.; Okuno, M.; Tomita, E.; et al. Prevention of Second Primary Tumors by an Acyclic Retinoid, Polyprenoic Acid, in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. Hepatoma Prevention Study Group. N. Engl. J. Med. 1996, 334, 1561–1567. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muto, Y.; Moriwaki, H.; Saito, A. Prevention of Second Primary Tumors by an Acyclic Retinoid in Patients with Hepatocellular Carcinoma. N. Engl. J. Med. 1999, 340, 1046–1047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Araki, H.; Shidoji, Y.; Yamada, Y.; Moriwaki, H.; Muto, Y. Retinoid Agonist Activities of Synthetic Geranyl Geranoic Acid Derivatives. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 1995, 209, 66–72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shidoji, Y.; Ogawa, H. Natural Occurrence of Cancer-Preventive Geranylgeranoic Acid in Medicinal Herbs. J. Lipid Res. 2004, 45, 1092–1103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mitake, M.; Ogawa, H.; Uebaba, K.; Shidoji, Y. Increase in Plasma Concentrations of Geranylgeranoic Acid after Turmeric Tablet Intake by Healthy Volunteers. J Clin Biochem Nutr 2010, 46, 252–258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shidoji, Y.; Tabata, Y. Unequivocal Evidence for Endogenous Geranylgeranoic Acid Biosynthesized from Mevalonate in Mammalian Cells. J. Lipid Res. 2019, 60, 579–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabata, Y.; Shidoji, Y. Hepatic Monoamine Oxidase B Is Involved in Endogenous Geranylgeranoic Acid Synthesis in Mammalian Liver Cells. J. Lipid Res. 2020, 61, 778–789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tabata, Y.; Shidoji, Y. Hepatic CYP3A4 Enzyme Compensatively Maintains Endogenous Geranylgeranoic Acid Levels in MAOB-Knockout Human Hepatoma Cells. Metabolites 2022, 12, 140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, Y.; Omori, M.; Shidoji, Y. Age-Dependent Decrease in Hepatic Geranylgeranoic Acid Content in C3H/HeN Mice and Its Oral Supplementation Prevents Spontaneous Hepatoma. Metabolites 2021, 11, 634. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Omori, M.; Shidoji, Y.; Moriwaki, H. Inhibition of Spontaneous Hepatocarcinogenesis by 4,5-Didehydrogeranylgeranoic Acid: Effects of Small-Dose and Infrequent Administration. Int. J. Transl. Med. 2023, 3, 487–495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, Y. Aging-Dependent Shift in Hepatic GGA Biosynthesis: A Proposed Axis Involving MAOB and CYP3A4 in Liver Cancer Susceptibility. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moriwaki, H.; Muto, Y.; Ninomiya, M.; Kawai, K.; Suzuki, Y.; Seto, T. Inhibitory Effects of Synthetic Acidic Retinoid and Polyprenoic Acid on the Development of Hepatoma in Rats Induced by 3′-Methyl-N, N-Dimethyl-4-Aminoazobenzene. J. Gastroenterol. 1988, 23, 546–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muto, Y.; Moriwaki, H. Acyclic Retinoids and Cancer Chemoprevention. Pure App Chem 1991, 63, 157–160. [Google Scholar]

- Tabata, Y.; Uematsu, S.; Shidoji, Y. Supplementation with Geranylgeranoic Acid during Mating, Pregnancy and Lactation Improves Reproduction Index in C3H/HeN Mice. J. Pet Anim. Nutr. 2020, 23, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, Y. A Hypothetical Role for Geranylgeranoic Acid as a Lipid Mediator in Male Reproductive Physiology. 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shidoji, Y. Induction of Hepatoma Cell Pyroptosis by Endogenous Lipid Geranylgeranoic Acid-A Comparison with Palmitic Acid and Retinoic Acid. Cells 2024, 13, 809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabata, Y. Biosynthesis of Geranylgeranoic Acid and its Hepatocarcinogenesis Prevention in Mammals. Vitamin 2023, 97, 505–510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).