Submitted:

03 July 2025

Posted:

03 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Preliminaries

- (i)

- For , we have

- (ii)

- For ,

3. Fractional-Order Chelyshkov Wavelets and Function Approximations in Two Dimensional Space

4. Error Bound

5. Numerical Method

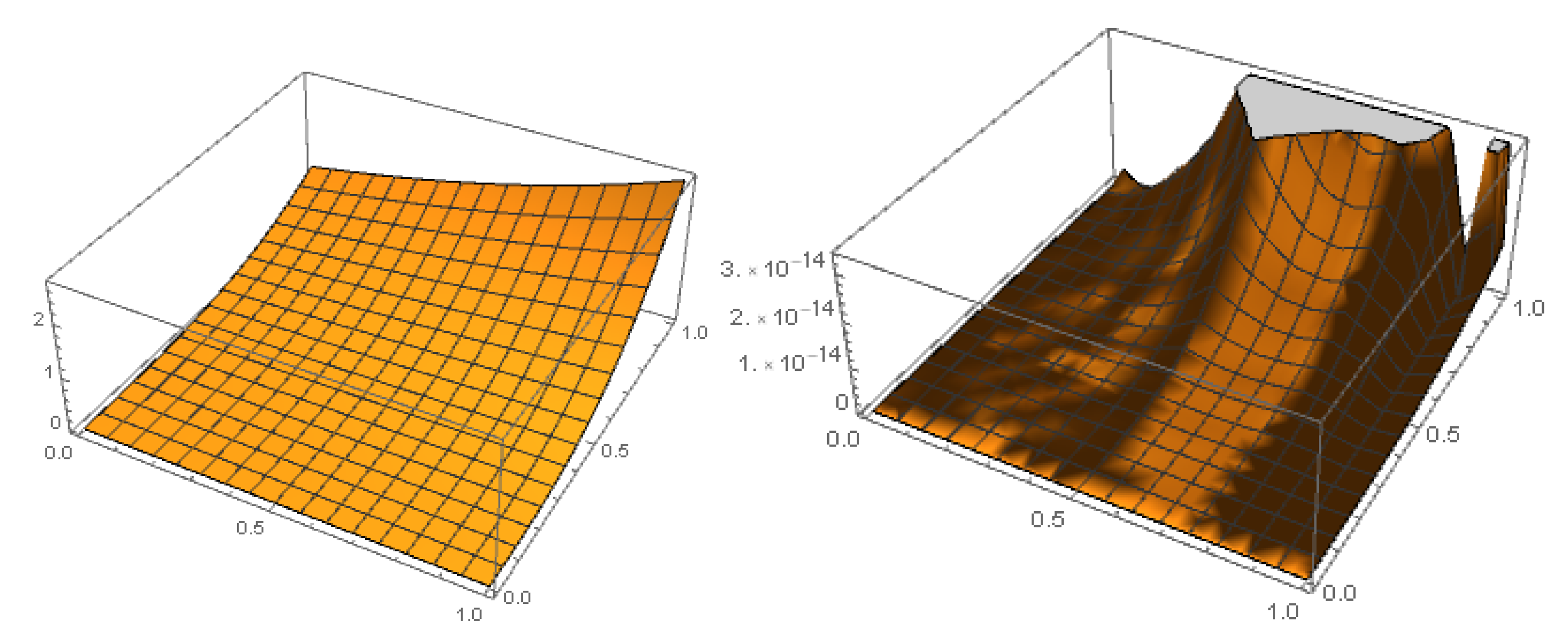

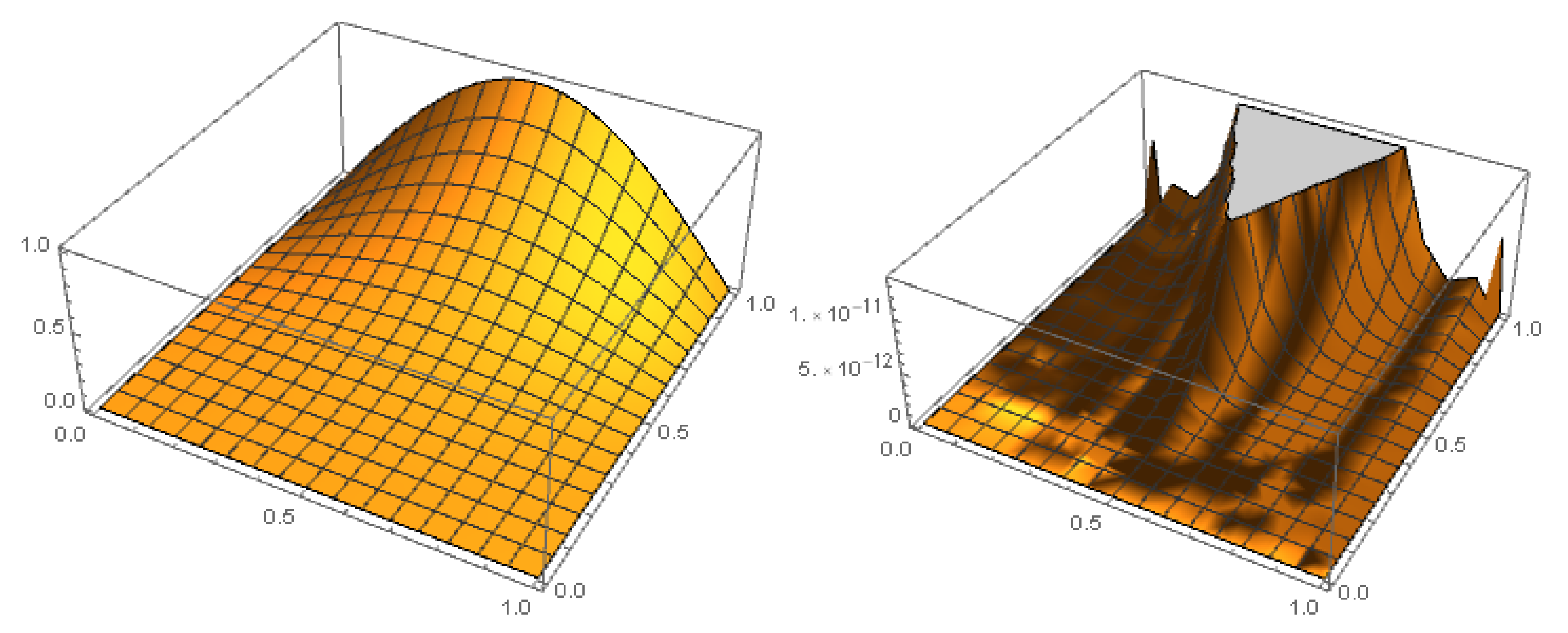

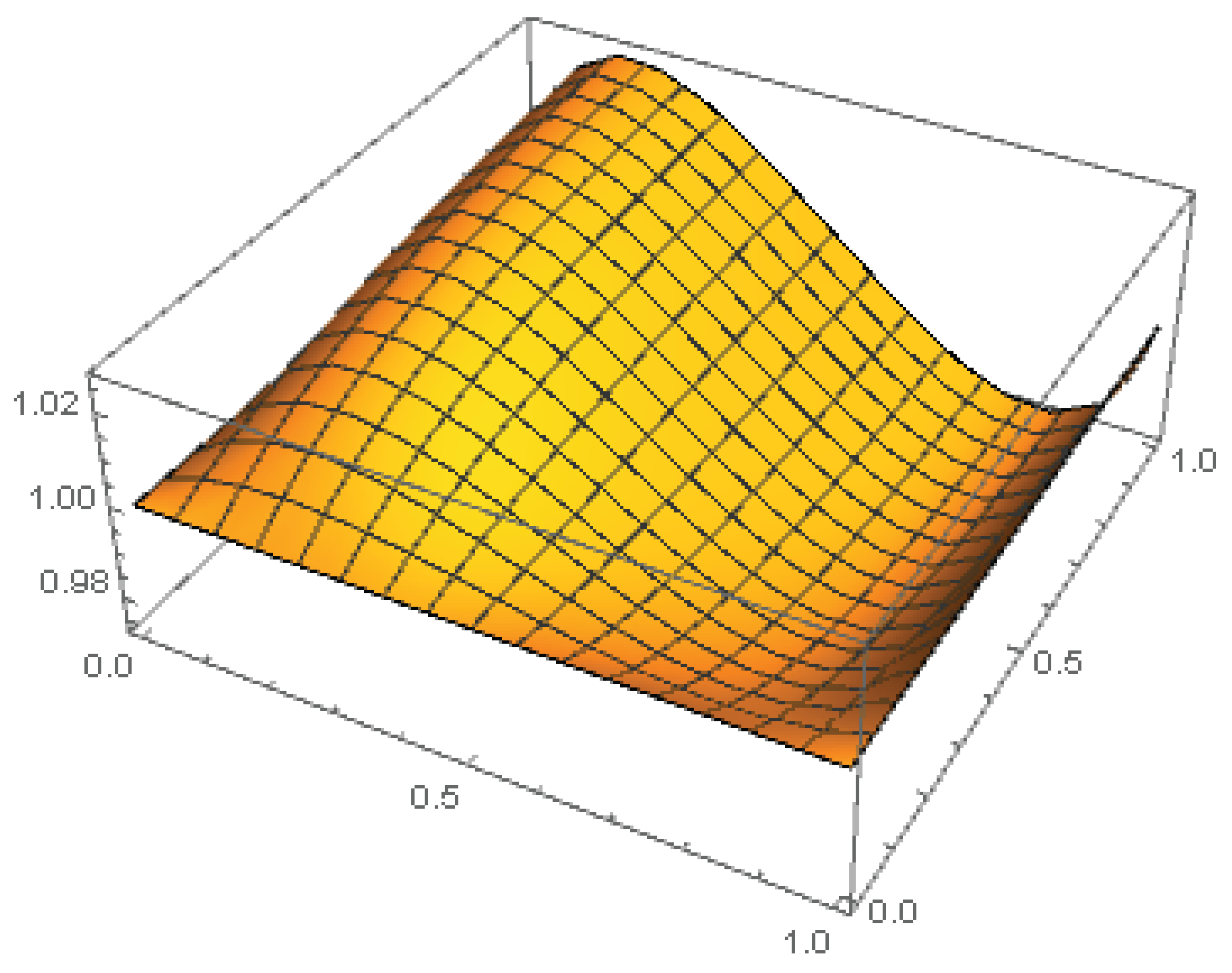

6. Illustrative Examples

7. Conclusions

References

- Sierociuk, D.; Dzieliński, A.; Sarwas, G.; Petras, I.; Podlubny, I.; Skovranek, T. Modelling heat transfer in heterogeneous media using fractional calculus. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences 2013, 371, 20120146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lopes, A.M.; Machado, J.A.T.; Pinto, C.M.A.; Galhano, A.M.S.F. Fractional dynamics and mds visualization of earthquake phenomena. Comput. Math. Appl. 2013, 66, 647–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carpinteri, A.; Mainardi, F. Fractals and fractional calculus in continuum mechanics; Springer, 2014; vol. 378. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Li, X.; Hu, X. A rbf-based differential quadrature method for solving two-dimensional variable-order time fractional advection-diffusion equation. J. Comput. Phys. 2019, 384, 222–238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rudolf, H. Applications of fractional calculus in physics; World scientific, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Magin, R.L. Fractional calculus models of complex dynamics in biological tissues. Comput. Math. Appl. 2010, 59, 1586–1593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loverro, A. Fractional calculus: history, definitions and applications for the engineer.Rapport technique, Univeristy of Notre Dame: Department of Aerospace and Mechanical Engineering (2014) 1–28.

- Bock, H.G.; Plitt, K.J. A multiple shooting algorithm for direct solution of optimal control problems. IFAC Proceedings Volumes 1984, 17, 1603–1608. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baleanu, D.; Machado, J.A.T.; Luo, A.C.J. Fractional dynamics and control; Springer Science & Business Media, 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Vinagre, B.M.; Feliu, V. Modeling and control of dynamic system using fractional calculus: Application to electrochemical processes and flexible structures. Proc. 41st IEEE Conf. Decision and Control, Las Vegas, NV, 2002; pp. 214–239. [Google Scholar]

- Ghafouri, H.; Ranjbar, M.; Khani, A. The use of partial fractional form of a-stable padé schemes for the solution of fractional diffusion equation with application in option pricing. Comput. Econ. 2019, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alkahtani, B.S.T.; Koca, I.; Atangan, A. A novel approach of variable order derivative: Theory and methods. J. Nonlinear Sci Appl. 9. 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Odzijewicz, T.; Malinowska, A.B.; Torres, D.F.M. Fractional variational calculus of variable order. In Advances in harmonic analysis and operator theory; Springer, 2013; pp. 291–301. [Google Scholar]

- Zaky, M.A.; Doha, E.H.; Taha, T.M. Baleanu,D. New recursive approximations for variable-order fractional operators with applications. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1804.01198 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, H.G.; Chang, A.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, W. A review on variable-order fractional differential equations: mathematical foundations, physical models, numerical methods and applications. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2019, 22, 27–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.G.; Chen, W.; Wei, H.; Chen, Y.Q. A comparative study of constant-order and variable-order fractional models in characterizing memory property of systems. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2011, 185–192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razminia, R.; Dizaji, A.; Majd, V.J. Solution existence for non-autonomous variable-order fractional differential equations. Math. Comput. Modell. 2011, 55, 1106–1117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S. Existence and uniqueness result of solutions to initial value problems of fractional differential equations of variable-order. J. Frac. Calc. Anal. 2013, 1, 82–98. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S. Existence result of solutions to differential equations of variable-order with nonlinear boundary value conditions. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2013, 18, 3289–3297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.M.; Wei, Y.Q.; Liu, D.Y.; Yu, H. Numerical solution for a class of nonlinear variable order fractional differential equations with legendre wavelets. Appl. Math. Lett. 2015, 83–88. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, H.; Sun, H.G.; Coopmans, C.; Chen, Y.Q. ; Bohannan,G.W. A physical experimental study of variable-order fractional integrator and differentiator. Eur. Phys. J. Spec. Top. 2011, 193, 93–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.G.; Chen, W.; Chen, Y.Q. Variable-order fractional differential operators in anomalous diffusion modeling. Physica A: Stat. Mecha. Appl. 2009, 388, 4586–4592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usman, M.; Hamid, M.; Haq, R.U.l.; Wang, W. An efficient algorithm based on gegenbauer wavelets for the solutions of variable-order fractional differential equations, Eur. Phys. J. Plus 2018, 133, 327. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawashdeh, E.A. Legendre wavelets method for fractional integro-differential equations. Appl. Math. Sci. 2011, 5, 2467–2474. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Fan, Q. The second kind chebyshev wavelet method for solving fractional differential equations. Appl. Math. Comput. 2012, 218, 8592–8601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuanlu, L. Solving a nonlinear fractional differential equation using chebyshev wavelets. Commun. Nonlinear Sci. Numer. Simul. 2010, 15, 2284–2292. [Google Scholar]

- Keshavarz, E.; Ordokhani, Y.; Razzaghi, M. Bernoulli wavelet operational matrix of fractional order integration and its applications in solving the fractional order differential equations. Applied Mathematical Modelling 2014, 38, 6038–6051. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phan, T.T.; Vo, N.T.; Razzaghi, M. Taylor wavelet method for fractional delay differential equations. Eng. Comput. 2021, 37, 231–240. [Google Scholar]

- Bhrawy, A.H.; Alhamed, Y.A.; Baleanu, D. New spectral techniques for systems of fractional differential equations using fractional-order generalized Laguerre orthogonal functions. Fract. Calc. Appl. Anal. 2014, 17, 1138–1157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kazem, S.; Abbasbandy, S.; Kumar, S. Fractional-order Legendre functions for solving fractional-order differential equations. Appl. Math. Model. 2013, 37, 5498–5510. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohammadi, F.; Cattani, C. Fractional-order Legendre wavelet Tau method for solving fractional differential equations. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 2018, 339, 306–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimkhani, P.; Ordokhani, Y.; Babolian, E. Fractional-order Bernoulli wavelets and their applications. Appl. Math. Model. 2016, 40, 8087–8107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashayekhi, S.; Razzaghi, M. Numerical solution of the fractional Bagley-Torvik equation by using hybrid functions approximation. Math. Methods Appl. Sci. 2016, 39, 353–365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mashayekhi, S.; Razzaghi, M. Numerical solution of distributed order fractional differential equations by hybrid functions. J. Comput. Phys. 2016, 315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vichitkunakorn, P.; Vo, T.N.; Razzaghi, M. A numerical method for fractional pantograph differential equations based on Taylor wavelets. Transactions of the Institute of Measurement and Control 2020, 42, 1334–1344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, M.H.; Avazzadeh, Z.; Haromi, M.F. A wavelet approach for solving multi-term variable-order time fractional diffusion-wave equation. Appl. Math. Comput. 2019, 341, 215–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseininia, M.; Heydari, *!!! REPLACE !!!*; M., H.; Maalek Ghaini, F. M. A numerical method for variable-order fractional version of the coupled 2D Burgers equations by the 2D Chelyshkov polynomials. Mathematical Methods in the Applied Sciences 2021, 44, 6482–6499. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimkhani, P.; Ordokhani, Y. Chelyshkov least squares support vector regression for nonlinear stochastic differential equations by variable fractional Brownian motion. Chaos, Solitons & Fractals 2022, 163, 112570. [Google Scholar]

- Rahimkhani, P.; Ordokhani, Y.; Lima, P. M. An improved composite collocation method for distributed-order fractional differential equations based on fractional Chelyshkov wavelets. Applied Numerical Mathematics 2019, 145, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, K.S.; Ross, B. An introduction to the fractional calculus and fractional differential equations; Wiley, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Abramowitz, M.; Stegun, I.A. Handbook of mathematical functions, Dover, 1973.

- Heydari, M.H.; Avazzadeh, Z.; Yang, Y. A computational method for solving variable-order fractional nonlinear diffusion-wave equation. Appl. Math. Comput. 2019, 352, 235–248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhrawy, A.H.; Zaky, M.A. A method based on the jacobi tau approximation for solving multi-term time–space fractional partial differential equations. J. Comput. Phys. 2015, 281, 876–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimkhani, P.; Ordokhani, Y. A numerical scheme based on bernoulli wavelets and collocation method for solving fractional partial differential equations with dirichlet boundary conditions. Numer. Methods Partial Differ. Equ. 2019, 35, 34–59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dahaghin, M.S.; Hassani, H. An optimization method based on the generalized polynomials for nonlinear variable-order time fractional diffusion-wave equation. Nonlinear Dyn. 2017, 88, 1587–1598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sandev, T.; Chechkin, A.V.; Korabel, N.; Kantz, H. Sokolov, I.M.; Metzler, R. Distributed-order diffusion equations and multifractality: Models and solutions. Physical Review E 2015, 92, 042117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| 1 | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method in [36] | Present method with | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | |||||||

| 2 | |||||||

| Method in [36] | Present method | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Method in [36] | Present method | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MaxRE | CO | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | − | |

| 2 | ||

| 3 | ||

| 4 | ||

| 5 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).