Submitted:

03 July 2025

Posted:

04 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Definition, Types, and Health Risks of PFAS

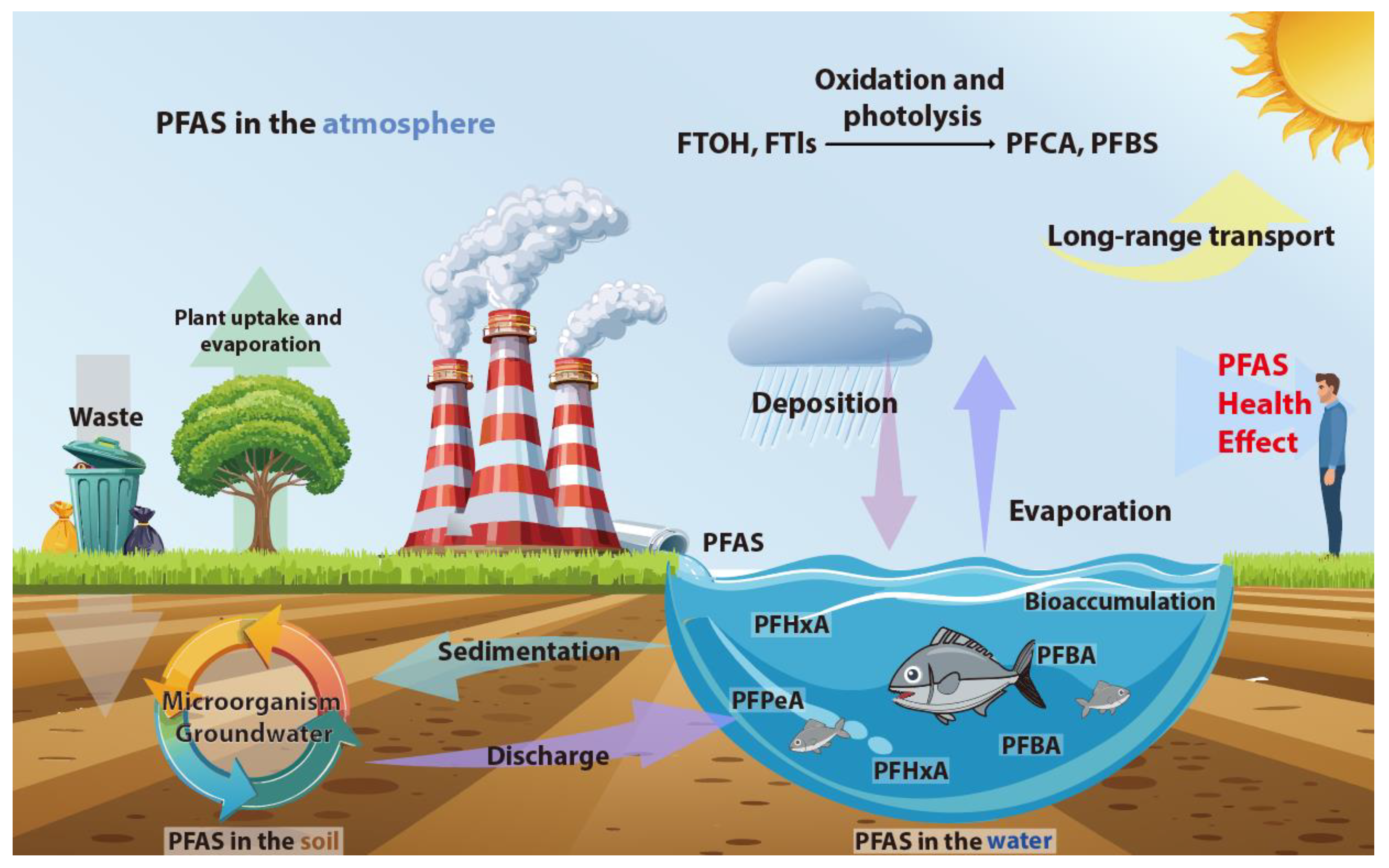

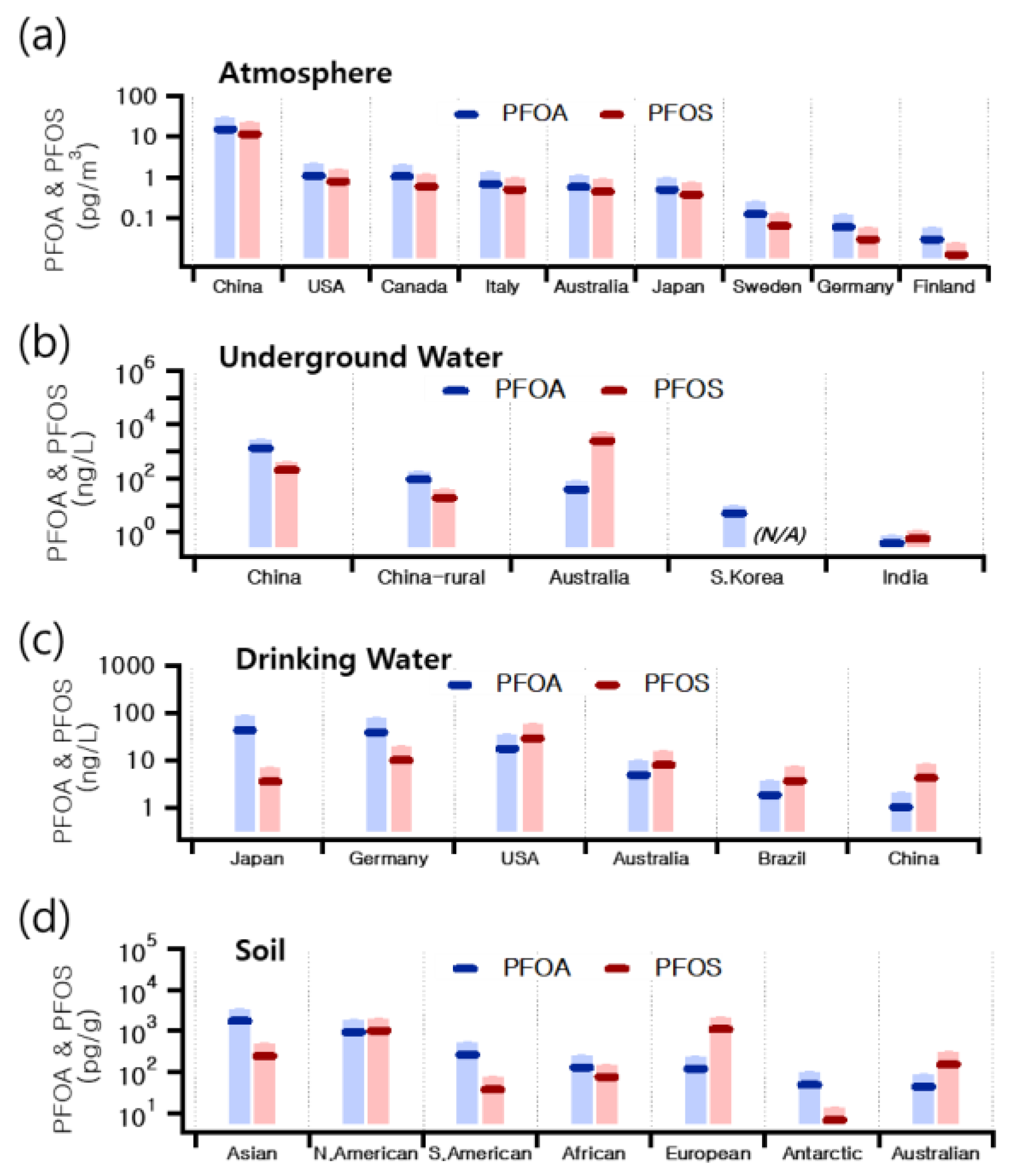

3. PFAS Environmental Concentration and Behavior in Air Pollution Research

4. PFAS Analysis Methods in Air Pollution Research

5. Future PFAS Management Strategies and Review Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- OECD. Reconciling terminology of the universe of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances: recommendations and practical guidance. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2021.

- Glüge, J.; Scheringer, M.; Cousins, I.T.; DeWitt, J.C.; Goldenman, G.; Herzke, D.; Lohmann, R.; Ng, C.A.; Trier, X.; Wang, Z. An overview of the uses of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS). Environ. Sci.: Process. 2020, Impacts 22, 2345–2373.

- E. Kissa, Fluorinated Surfactants and Repellents, Marcel Dekker AG, 2001.

- Johansson, J.H.; Berger, U.; Cousins, I.T. Can the use of deactivated glass fibre filters eliminate sorption artefacts associated with active air sampling of perfluorooctanoic acid? Environ. Pollut. 2017, 224, 779–786. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ahrens, L.; Bundschuh, M. Fate and effects of poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances in the aquatic environment: A review. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2014, 33, 1921–1929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Buck, R.C.; Franklin, J.; Berger, U.; Conder, J.M.; Cousins, I.T.; de Voogt, P.; Jensen, A.A.; Kannan, K.; Mabury, S.A.; van Leeuwen, S.P. Perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the environment: Terminology, classification, and origins. Integr. Environ. Assess. Manag. 2011, 7, 513–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Martin, J.W.; Smithwick, M.M.; Braune, B.M.; Hoekstra, P.F.; Muir, D.C.G.; Mabury, S.A. Identification of long-chain perfluorinated acids in biota from the Canadian Arctic. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 373–380. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Houde, M.; Czub, G.; Small, J.M.; Backus, S.; Wang, X.; Alaee, M.; Muir, D.C.G. Fractionation and bioaccumulation of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) isomers in a Lake Ontario food web. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 9397–9403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lindstrom, A.B.; Strynar, M.J.; Libelo, E.L. Polyfluorinated compounds: Past, present, and future. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 7954–7961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Loos, R.; Locoro, G.; Huber, T.; Wollgast, J.; Christoph, E.H.; de Jager, A.; Manfred Gawlik, B.; Hanke, G.; Umlauf, G.; Zaldívar, J.-M. Analysis of perfluorooctanoate (PFOA) and other perfluorinated compounds (PFCs) in the River Po watershed in N-Italy. Chemosphere. 2008, 71, 306–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powley, C.R.; George, S.W.; Russell, M.H.; Hoke, R.A.; Buck, R.C. Polyfluorinated chemicals in a spatially and temporally integrated food web in the Western Arctic. Chemosphere. 2008, 70, 664–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, N.; Taniyasu, S.; Petrick, G.; Wei, S.; Gamo, T.; Lam, P.K.S.; Kannan, K. Perfluorinated acids as novel chemical tracers of global circulation of ocean waters. Chemosphere. 2008, 70, 1247–1255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- OECD. ‘OECD, Summary Report on Updating the OECD 2007 List of Per- and Polyfluorinated Substances (PFASs), Report ENV/JM/MONO. 2018. Available online: http://www.oecd.org/officialdocuments/publicdisplaydocumentpdf/?cote= ENV-JM-MONO(2018)7&doclanguage=en (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- TSCA. “Toxic Substances Control Act Reporting and Recordkeeping Requirements for Perfluoroalkyl and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances.” TSCA Substances (2020). 2020.

- National Defense Authorization (2020). National Defense Authorization Act for Fiscal Year. 2020. Available online: https://www.congress.gov/bill/116th-congress/senatebill/1790 (accessed on 12 October 2024).

- EPA. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS): Basic Information and Effects. U.S. Environmental Protection Agency. 2021.

- Kourtchev, I.; Sebben, B.G.; Bogush, A.; Godoi, A.F.L.; Godoi, R.H.M. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in urban PM2.5 samples from Curitiba, Brazil. Atmos. Environ. 2023, 309, 119911. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ford, L.C.; Lin, H.-C.; Zhou, Y.-H.; Wright, F.A.; Gombar, V.K.; Sedykh, A.; Shah, R.R.; Chiu, W.A.; Rusyn, I. Characterizing PFAS hazards and risks: a human population-based in vitro cardiotoxicity assessment strategy. Hum. Genomics. 2024, 18, 92. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Al Amin, M.; Sobhani, Z.; Liu, Y.; Dharmaraja, R.; Chadalavada, S.; Naidu, R.; Chalker, J.M.; Fang, C. Recent advances in the analysis of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)—A review. Environ. Technol. Innov. 2020, 19, 100879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Z.; DeWitt, J.C.; Higgins, C.P.; Cousins, I.T. A never-ending story of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs)? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 2508–2518. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cousins, I.T.; Goldenman, G.; Herzke, D.; Lohmann, R.; Miller, M.; Ng, C.A. PFAS: forever chemicals—persistent, bioaccumulative and mobile. Reviewing the status and the need for their phase-out and remediation of contaminated sites. Environ. Sci. Eur. 2023, 35, 1–18. [Google Scholar]

- Averill, S.; Ginsberg, G.; Hays, S.; Makris, S.L. Perfluoroalkyl substances and cardiometabolic consequences in adolescents exposed to the World Trade Center disaster and a matched comparison group. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 2018, 221, 1087–1096. [Google Scholar]

- Sunderland, E.M.; Hu, X.C.; Dassuncao, C.; Tokranov, A.K.; Wagner, C.C.; Allen, J.G. A review of the pathways of human exposure to poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) and present understanding of health effects. J. Expo. Sci. Environ. Epidemiol. 2018, 28, 147–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rappazzo, K.M.; Coffman, E.; Hines, E.P. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substance toxicity and human health review: Current state of knowledge and strategies for informing future research. Environ. Health Perspect. 2017, 125, 124501. [Google Scholar]

- Grandjean, P.; Andersen, E.W.; Budtz-Jørgensen, E.; Nielsen, F.; Mølbak, K.; Weihe, P.; Heilmann, C. Serum vaccine antibody concentrations in children exposed to perfluorinated compounds. JAMA. 2012, 307, 391–397. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melzer, D.; Rice, N.; Depledge, M.H.; Henley, W.E.; Galloway, T.S. Association between serum perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and thyroid disease in the US National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey. Environ. Health Perspect. 2010, 118, 686–692. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fei, C.; McLaughlin, J.K.; Lipworth, L.; Olsen, J. Maternal levels of perfluorinated chemicals and subfecundity. Hum. Reprod. 2007, 22, 3254–3256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eriksen, K.T.; Sørensen, M.; McLaughlin, J.K.; Tjønneland, A.; Overvad, K.; Raaschou-Nielsen, O. Perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctane sulfonate plasma levels and risk of cancer in the general Danish population. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2009, 101, 605–609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- OECD. Reconciling terminology of the universe of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances: recommendations and practical guidance. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2023.

- IARC. Evaluation of the carcinogenicity of perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctane sulfonic acid (PFOS). International Agency for Research on Cancer. 2020.

- Wang, Z.; DeWitt, J.C.; Higgins, C.P.; Cousins, I.T. A never-ending story of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs)? Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 54, 3747–3751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- UNEP. Environmental Risks of Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances. United Nations Environment Programme. 2019.

- Place, B.J.; Field, J.A. Identification of novel fluorochemicals in aqueous film-forming foams used by the US military. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2012, 46, 7120–7127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Williams, A.J.; Grulke, C.M.; Edwards, J.; McEachran, A.D.; Mansouri, K.; Baker, N.C.; Patlewicz, G.; Shah, I.; Wambaugh, J.F.; Judson, R.S.; Richard, A.M. The CompTox Chemistry Dashboard: A community data resource for environmental chemistry. J. Cheminform. 2017, 9, 61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Patlewicz, G.; Richard, A.M.; Williams, A.J.; Grulke, C.M.; Sams, R.; Lambert, J.; Noyes, P.D.; DeVito, M.J.; Hines, R.N.; Strynar, M.; Guiseppi-Elie, A.; Thomas, R.S. A chemical category-based prioritization approach for selecting 75 per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) for tiered toxicity and toxicokinetic testing. Environ. Health Perspect. 2019, 127, 014501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patlewicz, G.; Richard, A.M.; Williams, A.J.; Judson, R.S.; Thomas, R.S. Towards reproducible structure-based chemical categories for PFAS to inform and evaluate toxicity and toxicokinetic testing. Comput. Toxicol. 2022, 24, 100250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Wu, J.; He, W.; Xu, F. A review on perfluoroalkyl acids studies: Environmental behaviors, toxic effects, and ecological and health risks. Ecosyst. Health Sustain. 2019, 5, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prevedouros, K.; Cousins, I.T.; Buck, R.C.; Korzeniowski, S.H. Sources, fate, and transport of perfluorocarboxylates. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 32–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Andrews, D.Q.; Hayes, J.; Stoiber, T.; Brewer, B.; Campbell, C.; Naidenko, O.V. Identification of point source dischargers of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in the United States. AWWA Water Sci. 2021, 3, e1252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ellis, D.A.; Martin, J.W.; De Silva, A.O.; Mabury, S.A.; Hurley, M.D.; Sulbaek Andersen, M.P.; Nielsen, O.J. Degradation of fluorotelomer alcohols: A likely atmospheric source of perfluorinated carboxylic acids. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 3316–3321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinglasan, M.J.A.; Ye, Y. , Edwards, E.A.; Mabury, S.A. Aerobic biotransformation of 14C-labeled 8-2 telomer alcohol by activated sludge from a domestic sewage treatment plant. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 1225–1231. [Google Scholar]

- Butt, C.M.; Berger, U.; Bossi, R.; Tomy, G.T. Review: Spatial trends of perfluoroalkyl substances in wildlife. Chemosphere. 2010, 78, 933–941. [Google Scholar]

- Martin, J.W.; Asher, B.J.; Beesoon, S.; Benskin, J.P.; Ross, M.S. Biodegradation and metabolism of polyfluorinated compounds. Rev. Environ. Contam. Toxicol. 2010, 208, 53–71. [Google Scholar]

- Begley, T.H.; White, K.; Honigfort, P.; Twaroski, M.L.; Neches, R.; Walker, R.A. Perfluorochemicals: Potential sources of and migration from food packaging. Food Addit. Contam. 2005, 22, 1023–1031. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, B.; Peck, A.M.; Schnoor, J.L.; Hornbuckle, K.C. Mass budget of perfluorooctane surfactants in Lake Ontario. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 74–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Eon, J.C.; Mabury, S.A. Production of perfluorinated carboxylic acids (PFCAs) from polyfluoroalkyl phosphate diesters (PAPs) in the rat. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 956–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Webster, E.; Ellis, D.A.; McLachlan, M.S. Modeling the fate of perfluorocarboxylates and their precursors in the atmosphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 6123–6130. [Google Scholar]

- Chiappero, M.S.; Malanca, F.E.; Argüello, G.A.; Wooldridge, S.T.; Hurley, M.D.; Ball, J.C.; Wallington, T.J.; Waterland, R.L.; Buck, R.C. Atmospheric chemistry of perfluoroaldehydes and fluorotelomer aldehydes: Quantification of the important role of photolysis. J. Phys. Chem. A. 2006, 110, 11944–11953. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D'Eon, J.C.; Hurley, M.D.; Wallington, T.J.; Mabury, S.A. Atmospheric chemistry of N-methyl perfluorobutane sulfonamidoethanol: Kinetics and mechanism of reaction with OH. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 1862–1868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Conder, J.M.; Hoke, R.A.; Wolf, W.d.; Russell, M.H.; Buck, R.C. Are PFCAs bioaccumulative? A critical review and comparison with regulatory criteria and persistent lipophilic compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2008, 42, 995–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kannan, K.; Corsolini, S.; Falandysz, J.; Oehme, G.; Focardi, S.; Giesy, J.P. Perfluorooctanesulfonate and related fluorinated hydrocarbons in marine mammals, fishes, and birds from coasts of the Baltic and the Mediterranean Seas. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 3210–3216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, K.S.; Zushi, Y.; Masunaga, S.; Gilligan, M.; Pride, C.; Sajwan, K.S. Perfluorinated organic contaminants in sediment and aquatic wildlife, including sharks, from Georgia, USA. Mar. Pollut. Bull. 2009, 58, 621–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toms, L.; Bräunig, J.; Vijayasarathy, S.; Phillips, S.; Hobson, P.; Aylward, L.; Kirk, M.; Mueller, J. Per-and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in Australia: Current levels and estimated population reference values for selected compounds. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 2019, 222, 387–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bossi, R.; Skjøth, C.A.; Skov, H. Three years (2008–2010) of measurements of atmospheric concentrations of organochlorine pesticides (OCPs) at Station Nord, North-East Greenland. Environ. Sci.: Process Impacts. 2013, 15, 2213–2219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dreyer, A.; Matthias, V.; Temme, C.; Ebinghaus, R. Annual Time Series of Air Concentrations of Polyfluorinated Compounds. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 4029–4036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnke, A.; Berger, U.; Ebinghaus, R.; Temme, C. Latitudinal Gradient of Airborne Polyfluorinated Alkyl Substances in the Marine Atmosphere between Germany and South Africa (53° N−33° S). Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 3055–3061. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shimizu, M.S.; Mott, R.; Potter, A.; Zhou, J.; Baumann, K.; Surratt, J.D.; Turpin, B.; Avery, G.B.; Harfmann, J.; Kieber, R.J.; Mead, R.N.; Skrabal, S.A.; Willey, J.D. Atmospheric Deposition and Annual Flux of Legacy Perfluoroalkyl Substances and Replacement Perfluoroalkyl Ether Carboxylic Acids in Wilmington, NC, USA. Environ. Sci. Technol. Lett. 2021, 8, 366–372. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Ruan, Y.; Lin, H.; Lam, P.K.S. Review on perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in the Chinese atmospheric environment. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 737, 139804. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoeib, M.; Harner, T.; M Webster, G.; Lee, S.C. Indoor Sources of Poly- and Perfluorinated Compounds (PFCS) in Vancouver, Canada: Implications for Human Exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 7999–8005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Valsecchi, S.; Conti, D.; Crebelli, R.; Polesello, S.; Rusconi, M.; Mazzoni, M.; Preziosi, E.; Carere, M.; Lucentini, L.; Ferretti, E.; Balzamo, S.; Simeone, M.G.; Aste, F. Deriving environmental quality standards for perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and related short chain perfluorinated alkyl acids. J. Hazard. Mater. 2017, 323, 84–98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, S.; Jiao, X.-C.; Gai, N.; Li, X.-J.; Wang, X.-C.; Lu, G.-H.; Piao, H.-T.; Rao, Z.; Yang, Y.-L. Perfluorinated compounds in soil, surface water, and groundwater from rural areas in eastern China. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 211, 124–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, J.; Yu, W.-J.; Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Jin, Y.-H.; Dong, G.-H. Perfluoroalkyl substances in groundwater and home-produced vegetables and eggs around a fluorochemical industrial park in China. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 171, 199–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hepburn, E.; Madden, C.; Szabo, D.; Coggan, T.L.; Clarke, B.; Currell, M. Contamination of groundwater with per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) from legacy landfills in an urban re-development precinct. Environ. Pollut. 2019, 248, 101–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sharma, B.M.; Bharat, G.K.; Tayal, S.; Larssen, T.; Bečanová, J.; Karásková, P.; Whitehead, P.G.; Futter, M.N.; Butterfield, D.; Nizzetto, L. Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in river and ground/drinking water of the Ganges River basin: Emissions and implications for human exposure. Environ. Pollut. 2016, 208, 704–713. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yong, Z.Y.; Kim, K.Y.; Oh, J.-E. The occurrence and distributions of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) in groundwater after a PFAS leakage incident in 2018. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 268, 115395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mak, Y.L.; Taniyasu, S.; Yeung, L.W.Y.; Lu, G.; Jin, L.; Yang, Y.; Lam, P.K.S.; Kannan, K.; Yamashita, N. Perfluorinated compounds in tap water from China and several other countries. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 4824–4829. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Quinete, N.; Wu, Q.; Zhang, T.; Yun, S.H.; Moreira, I.; Kannan, K. Specific profiles of perfluorinated compounds in surface and drinking waters and accumulation in mussels, fish, and dolphins from southeastern Brazil. Chemosphere. 2009, 77, 863–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiñones, O.; Snyder, S.A. Occurrence of perfluoroalkyl carboxylates and sulfonates in drinking water utilities and related waters from the United States. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2009, 43, 9089–9095. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takagi, S.; Adachi, F.; Miyano, K.; Koizumi, Y.; Tanaka, H.; Mimura, M.; Watanabe, I.; Tanabe, S.; Kannan, K. Perfluorooctanesulfonate and perfluorooctanoate in raw and treated tap water from Osaka, Japan. Chemosphere. 2008, 72, 1409–1412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.; Eaglesham, G.; Mueller, J. Concentrations of PFOS, PFOA and other perfluorinated alkyl acids in Australian drinking water. Chemosphere. 2011, 83, 1320–1325. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilhelm, M.; Bergmann, S.; Dieter, H.H. Occurrence of perfluorinated compounds (PFCs) in drinking water of North Rhine-Westphalia, Germany, and new approach to assess drinking water contamination by shorter-chained C4-C7 PFCs. Int. J. Hyg. Environ. Health. 2010, 213, 224–232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rankin, K.; Mabury, S.A.; Jenkins, T.M.; Washington, J.W. A North American and global survey of perfluoroalkyl substances in surface soils: Distribution patterns and mode of occurrence. Chemosphere. 2016, 161, 333–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, T.; Wang, P.; Meng, J.; Liu, S.; Lu, Y.; Khim, J.S.; Giesy, J.P. A review of sources, multimedia distribution and health risks of perfluoroalkyl acids (PFAAs) in China. Chemosphere. 2015, 129, 87–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zareitalabad, P.; Siemens, J.; Hamer, M.; Amelung, W. Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) in surface waters, sediments, soils and wastewater—A review on concentrations and distribution coefficients. Chemosphere. 2013, 91, 725–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Podder, A.; Sadmani, A.H.M.A.; Reinhart, D.; Chang, N.-B.; Goel, R. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) as a contaminant of emerging concern in surface water: A transboundary review of their occurrences and toxicity effects. J. Hazard. Mater. 2021, 419, 126361. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zarębska, M.; Bajkacz, S. Poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS)—Recent advances in the aquatic environment analysis. TrAC Trends Anal. Chem. 2023, 163, 117062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barber, J.L.; Berger, U.; Chaemfa, C.; Huber, S.; Jahnke, A.; Temme, C.; Jones, K.C. Analysis of per- and polyfluorinated alkyl substances in air samples from Northwest Europe. J. Environ. Monit. 2007, 9, 530–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, B.; Vargo, J.D.; Schnoor, J.L.; Hornbuckle, K.C. Perfluorooctane sulfonic acid–photolysis, and intermediates. Environ. Toxicol. Chem. 2005, 24, 1338–1340. [Google Scholar]

- Fiedler, H.; de Boer, J.; Abad, E. Persistent organic pollutants in air across the globe using a comparative passive air sampling method. TrAC Trends in Analytical Chemistry. 2024, 171, 117494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahnke, A.; Ahrens, L.; Ebinghaus, R.; Berger, U.; Barber, J.L.; Temme, C. An improved method for the analysis of volatile polyfluorinated alkyl substances in environmental air samples. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2007, 387, 965–975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kubwabo, C.; Stewart, B.; Zhu, J.; Marro, L. Occurrence of perfluorosulfonates and other perfluorochemicals in dust from selected homes in the city of Ottawa, Canada. J. Environ. Monit. 2005, 7, 1074–1078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, J.; Del Vento, S.; Schuster, J.; Zhang, G.; Chakraborty, P.; Kobara, Y.; Jones, K.C. Perfluorinated Compounds in the Asian Atmosphere. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2011, 45, 7241–7248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Moriwaki, H.; Takata, Y.; Arakawa, R. Concentrations of perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) in vacuum cleaner dust collected in Japanese homes. J. Environ. Monit. 2003, 5, 753–757. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Padilla-Sánchez, J.A.; Papadopoulou, E.; Poothong, S.; Haug, L.S. Investigation of the best approach for assessing human exposure to poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances through indoor air. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 12836–12843. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saini, A.; Chinnadurai, S.; Schuster, J.K.; Eng, A.; Harner, T. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances and volatile methyl siloxanes in global air: Spatial and temporal trends. Environ. Pollut. 2023, 323, 121291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoeib, M.; Harner, T.; Ikonomou, M.; Kannan, K. Indoor and outdoor air concentrations and phase partitioning of perfluoroalkyl sulfonamides and polybrominated diphenyl ethers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 1313–1320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoeib, M.; Harner, T.; Lee, S.C.; Lane, D.; Zhu, J. Sorbent-impregnated polyurethane foam disk for passive air sampling of volatile fluorinated chemicals. Anal. Chem. 2008, 80, 675–682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shoeib, T.; Hassan, Y.; Rauert, C.; Harner, T. Poly- and perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in indoor dust and food packaging materials in Egypt: Trends in developed and developing countries. Chemosphere. 2016, 144, 1573–1581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Sun, H.; Chang, S.; Zhu, L.; Alder, A.C.; Kannan, K. Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in indoor air and dust from homes and various microenvironments in China: Implications for human exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 3156–3166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Backe, W.J.; Day, T.C.; Field, J.A. Zwitterionic, cationic, and anionic fluorinated chemicals in aqueous film-forming foam formulations and groundwater from US military bases by nonaqueous large-volume injection HPLC-MS/MS. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 5226–5234. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boiteux, V.; Dauchy, X.; Bach, C.; Colin, A.; Hemard, J.; Sagres, V.; Rosin, C.; Munoz, J.-F. Concentrations and patterns of perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances in a river and three drinking water treatment plants near and far from a major production source. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 583, 393–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boulanger, B.; Vargo, J.; Schnoor, J.L.; Hornbuckle, K.C. Detection of perfluorooctane surfactants in Great Lakes water. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 4064–4070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Deng, Z.-H.; Cheng, C.-G.; Wang, X.-L.; Shi, S.-H.; Wang, M.-L.; Zhao, R.-S. Preconcentration and determination of perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in water samples by bamboo charcoal-based solid-phase extraction prior to liquid chromatography–tandem mass spectrometry. Molecules. 2018, 23, 902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- González-Barreiro, C.; Martínez-Carballo, E.; Sitka, A. , Scharf, S.; Gans, O. Method optimization for determination of selected perfluorinated alkylated substances in water samples. Anal. Bioanal. Chem. 2006, 386, 2123–2132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, K.J.; Johnson, H.; Eldridge, J.; Butenhoff, J.; Dick, L. Quantitative characterization of trace levels of PFOS and PFOA in the Tennessee River. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2002, 36, 1681–1685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hao, S.; Choi, Y.J.; Deeb, R.A.; Strathmann, T.J.; Higgins, C.P. Application of hydrothermal alkaline treatment for destruction of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in contaminated groundwater and soil. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2022, 56, 6647–6657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hebert, G.N.; Odom, M.A.; Craig, P.S.; Dick, D.L.; Strauss, S.H. Method for the determination of sub-ppm concentrations of perfluoroalkylsulfonate anions in water. J. Environ. Monit. 2002, 4, 90–95. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janda, J.; Nödler, K.; Brauch, H.-J.; Zwiener, C.; Lange, F.T. Robust trace analysis of polar (C2-C8) perfluorinated carboxylic acids by liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry: method development and application to surface water, groundwater and drinking water. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2019, 26, 7326–7336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaboré, H.A.; Duy, S.V.; Munoz, G.; Méité, L.; Desrosiers, M.; Liu, J.; Sory, T.K.; Sauvé, S. Worldwide drinking water occurrence and levels of newly-identified perfluoroalkyl and polyfluoroalkyl substances. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 616, 1089–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loewen, M.; Halldorson, T.; Wang, F.; Tomy, G. Fluorotelomer carboxylic acids and PFOS in rainwater from an urban center in Canada. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 2944–2951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loos, R.; Tavazzi, S.; Mariani, G.; Suurkuusk, G.; Paracchini, B.; Umlauf, G. Analysis of emerging organic contaminants in water, fish and suspended particulate matter (SPM) in the Joint Danube Survey using solid-phase extraction followed by UHPLC-MS-MS and GC–MS analysis. Sci. Total Environ. 2017, 607, 1201–1212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Miyake, Y.; Yamashita, N.; Rostkowski, P.; So, M.K.; Taniyasu, S.; Lam, P.K.S.; Kannan, K. Determination of trace levels of total fluorine in water using combustion ion chromatography for fluorine: A mass balance approach to determine individual perfluorinated chemicals in water. J. Chromatogr. A. 2007, 1143, 98–104. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schaefer, C.E.; Nguyen, D.; Fang, Y.; Gonda, N.; Zhang, C.; Shea, S.; Higgins, C.P. PFAS Porewater concentrations in unsaturated soil: Field and laboratory comparisons inform on PFAS accumulation at air-water interfaces. J. Contam. Hydrol. 2024, 264, 104359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, M.M.; Barofsky, D.F.; Field, J.A. Quantitative determination of fluorotelomer sulfonates in groundwater by LC MS/MS. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 1828–1835. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wilson, S.R.; Malerød, H.; Holm, A.; Molander, P.; Lundanes, E.; Greibrøkk, T. On-line SPE–Nano-LC–Nanospray-MS for rapid and sensitive determination of perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorooctane sulfonate in river water. J. Chromatogr. Sci. 2007, 45, 146–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamashita, N.; Kannan, K.; Taniyasu, S.; Horii, Y.; Okazawa, T.; Petrick, G.; Gamo, T. Analysis of perfluorinated acids at parts-per-quadrillion levels in seawater using liquid chromatography-tandem mass spectrometry. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2004, 38, 5522–5528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baqar, M.; Saleem, R.; Zhao, M.; Zhao, L.; Cheng, Z.; Chen, H.; Yao, Y.; Sun, H. Combustion of high-calorific industrial waste in conventional brick kilns: An emerging source of PFAS emissions to agricultural soils. Sci. Total Environ. 2024, 906, 167612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Higgins, C.P.; Field, J.A.; Criddle, C.S.; Luthy, R.G. Quantitative determination of perfluorochemicals in sediments and domestic sludge. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 3946–3956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Müller, V.; Andrade Costa, L.C.; Rondan, F.S.; Matic, E.; Mesko, M.F.; Kindness, A.; Feldmann, J. Per- and polyfluoroalkylated substances (PFAS) target and EOF analyses in ski wax, snowmelts, and soil from skiing areas. Environ. Sci.: Process. Impacts. 2023, 25, 1926–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Powley, C.R.; George, S.W.; Ryan, T.W.; Buck, R.C. Matrix effect-free analytical methods for determination of perfluorinated carboxylic acids in environmental matrices. Anal. Chem. 2005, 77, 6353–6358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schröder, H.F. Determination of fluorinated surfactants and their metabolites in sewage sludge samples by liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry and tandem mass spectrometry after pressurized liquid extraction and separation on fluorine-modified reversed-phase sorbents. J. Chromatogr. A. 2003, 1020, 131–151. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Semerád, J.; Hatasová, N.; Grasserová, A.; Černá, T.; Filipová, A.; Hanč, A.; Innemanová, P.; Pivokonský, M.; Cajthaml, T. Screening for 32 per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) including GenX in sludges from 43 WWTPs located in the Czech Republic - Evaluation of potential accumulation in vegetables after application of biosolids. Chemosphere. 2020, 261, 128018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, E.; Kannan, K. Mass loading and fate of perfluoroalkyl surfactants in wastewater treatment plants. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 1408–1414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Chen, L.; Wang, J.; Hou, J.; Han, B.; Liu, W. Spatial distribution, compositional characteristics, and source apportionment of legacy and novel per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in farmland soil: A nationwide study in mainland China. J. Hazard. Mater. 2024, 470, 134238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, J.W.; Ellington, J.J.; Jenkins, T.M.; Evans, J.J. Analysis of perfluorinated carboxylic acids in soils: Detection and quantitation issues at low concentrations. J. Chromatogr. A. 2007, 1154, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Washington, J.W.; Henderson, W.M.; Ellington, J.J.; Jenkins, T.M.; Evans, J.J. Analysis of perfluorinated carboxylic acids in soils II: Optimization of chromatography and extraction. J. Chromatogr. A. 2008, 1181, 21–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fromme, H.; Schlummer, M.; Möller, A.; Gruber, L.; Wolz, G.; Ungewiss, J.; Böhmer, S.; Dekant, W.; Mayer, R.; Liebl, B. Exposure of an adult population to perfluorinated substances using duplicate diet portions and biomonitoring data. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 7928–7933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, S.; Kim, S.; Park, J.; Kim, H.-J.; Choi, G.; Choi, S.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.Y.; Kim, S.; Choi, K.; Moon, H.-B. Perfluoroalkyl substances (PFASs) in breast milk from Korea: Time-course trends, influencing factors, and infant exposure. Sci. Total Environ. 2018, 612, 286–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Llorca, M.; Farré, M.; Picó, Y.; Teijón, M.L.; Álvarez, J.G.; Barceló, D. Infant exposure of perfluorinated compounds: Levels in breast milk and commercial baby food. Environ. Int. 2010, 36, 584–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luque, N.; Ballesteros-Gómez, A.; van Leeuwen, S.; Rubio, S. Analysis of perfluorinated compounds in biota by microextraction with tetrahydrofuran and liquid chromatography/ion isolation-based ion-trap mass spectrometry. J. Chromatogr. A. 2010, 1217, 3774–3782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nania, V.; Pellegrini, G.E.; Fabrizi, L.; Sesta, G.; De Sanctis, P.; Lucchetti, D.; Di Pasquale, M.; Coni, E. Monitoring of perfluorinated compounds in edible fish from the Mediterranean Sea. Food Chem. 2009, 115, 951–957. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Squadrone, S.; Ciccotelli, V.; Prearo, M.; Favaro, L.; Scanzio, T.; Foglini, C.; Abete, M. Perfluorooctane sulfonate (PFOS) and perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA): Emerging contaminants of increasing concern in fish from Lake Varese, Italy. Environ. Monit. Assess. 2015, 187, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tittlemier, S.A.; Pepper, K.; Seymour, C.; Moisey, J.; Bronson, R.; Cao, X.-L.; Dabeka, R.W. Dietary exposure of Canadians to perfluorinated carboxylates and perfluorooctane sulfonate via consumption of meat, fish, fast foods, and food items prepared in their packaging. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2007, 55, 3203–3210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabaleta, I.; Bizkarguenaga, E.; Iparragirre, A.; Navarro, P.; Prieto, A.; Fernández, L.Á.; Zuloaga, O. Focused ultrasound solid–liquid extraction for the determination of perfluorinated compounds in fish, vegetables and amended soil. J. Chromatogr. A. 2014, 1331, 27–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dinglasan-Panlilio, M.J.A.; Mabury, S.A. Significant residual fluorinated alcohols present in various fluorinated materials. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2006, 40, 1447–1453. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sinclair, E.; Kim, S.K.; Akinleye, H.B.; Kannan, K. Quantitation of gas-phase perfluoroalkyl surfactants and fluorotelomer alcohols released from nonstick cookware and microwave popcorn bags. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2007, 41, 1180–1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zabaleta, I.; Bizkarguenaga, E.; Bilbao, D.; Etxebarria, N.; Prieto, A.; Zuloaga, O. Fast and simple determination of perfluorinated compounds and their potential precursors in different packaging materials. Talanta. 2016, 152, 353–363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zabaleta, I.; Negreira, N.; Bizkarguenaga, E.; Prieto, A.; Covaci, A.; Zuloaga, O. Screening and identification of per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances in microwave popcorn bags. Food Chem. 2017, 230, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafeiraki, E.; Costopoulou, D.; Vassiliadou, I.; Bakeas, E.; Leondiadis, L. Determination of perfluorinated compounds (PFCs) in various foodstuff packaging materials used in the Greek market. Chemosphere. 2014, 94, 169–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| References | Definitions |

|---|---|

| Buck et al. (2011) [6] | -Definition: PFAS are aliphatic substances where all hydrogen atoms in the carbon chain are replaced by fluorine atoms, including the "perfluoroalkyl moiety (-CnF2n+1−)." -Note: The moiety implies a fully fluorinated terminal carbon, but the textual definition does not explicitly require it. |

| OECD (2018) [13] | -Definition: PFAS are chemicals with a perfluoroalkyl moiety containing at least three carbons (–CnF2n−, n ≥ 3) or a perfluoroalkylether moiety with at least two carbons (–CnF2nOCmF2m−, n, m ≥ 1). -Note: Expanded the perfluoroalkyl moiety from Buck et al.'s "(CnF2n+1−)" to "–CnF2n–," including cases where both ends of the moiety are attached to functional groups. |

| TSCA (2020) [14] | -Definition: Any chemical substance or mixture containing the structural unit R-(CF2)-C(F)(R′)R″. -Both CF2 and CF moieties are saturated carbons, and none of the R groups (R, R′, or R″) can be hydrogen. -Application: Proposed rule for TSCA reporting and recordkeeping requirements and the 2021 Draft Drinking Water Contaminant Candidate List. |

| National Defense Authorization (2020) [15] | -Definition: Man-made chemicals with at least one fully fluorinated carbon atom. -Note: A simplified definition to encompass a broad range of PFAS. |

| OECD (2021) [1] | -Definition: Fluorinated substances containing at least one fully fluorinated methyl (–CF3) or methylene (–CF2–) carbon atom without any H/Cl/Br/I attached. -Note: Removes the requirement for entirely aliphatic structures, only requiring a minimally fully fluorinated carbon group. |

| EPA (2021) [16] | -PFASMASTER List: Initially contained over 5,000 unique PFAS, including substances without defined chemical structures, polymers, and mixtures. -PFASSTRUCT List: Structure-based definitions to clearly delineate PFAS chemical space for research and regulatory purposes. |

| Reference | Key Findings |

|---|---|

| Cousins et al., 2023 [21] |

Highlighted the persistence, bioaccumulation, and mobility of PFAS and stressed the need for phase-out strategies and remediation of contaminated areas. The study detailed the effects of PFAS on the immune system and liver. |

| Averill et al., 2018 [22] |

Investigated the association between PFAS exposure and cardiometabolic outcomes in adolescents exposed to the World Trade Center disaster. Found that PFAS exposure may affect lipid profiles and insulin resistance. |

| Sunderland et al., 2018 [23] | Examined the human exposure pathways and health effects of PFASs. Found that PFAS persist in the environment and can expose humans through drinking water and seafood. PFAS exposure is linked to immune suppression, metabolic disorders, and neurodevelopmental issues. |

| Rappazzo et al., 2017 [24] | Reviewed the toxicity of PFAS and their impact on human health, emphasizing links between PFAS exposure and liver dysfunction, reduced immune response, and developmental problems. |

| Grandjean et al., 2012 [25] | Reviewed the link between PFAS exposure and immune-related health outcomes in children. Found that PFAS exposure could negatively impact the immune system, including reduced antibody response to vaccines. |

| Melzer et al., 2010 [26] | Investigated the relationship between PFAS exposure and thyroid function in adults. Found that PFAS exposure may alter thyroid hormone levels. |

| Fei et al., 2007 [27] | Found that PFAS exposure during pregnancy is associated with reduced birth weight in offspring, emphasizing the potential negative effects of PFAS on fetal development. |

| Eriksen et al., 2009 [28] | Examined the association between PFAS exposure and hepatocellular carcinoma in the general population. Concluded that high PFAS exposure is linked to an increased risk of liver cancer. |

| Sample Matrix | Analytical Technique | Extraction Approach | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| Air and air particle | GC-MS1, GC-MS/MS2, LC-MS/MS3 | ASE10, Cold column extraction, Concentration after solvent capture, SLE11, Soxhlet extraction, SPE12 | [77,78,79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89] |

| Water | GC-MS/MS, LC-MS/MS, LC-HRMS4, 19F-NMR5, Nano-LC-MS6 | Automated solid phase extraction, LLE13, Micro-LLE14, Soxhlet extraction, SPE, SPME15, Turbulent flow chromatography based online extraction | [69,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98,99,100,101,102,103,104,105,106] |

| Soil and sediment | Flow injection-MS/MS7, LC-HRMS, LC-MS/MS, LC-QToF-MS8 | FUSLE16, Hot vapour/Soxhelt extraction & PLE17, PLE, SLE, SPE | [107,108,109,110,111,112,113,114,115,116] |

| Foods | LC-MS/MS, LC-QqLIT-MS9 | FUSLE, IPE18, LLE, Micro-extraction, PLE, SLE, SPE | [117,118,119,120,121,122,123,124] |

| Packaging materials | GC-MS, LC-MS/MS, LC-QToF-MS | FUSLE, PLE, SLE, SPE, UPAE19, XAD extracted with EtOAc20 | [125,126,127,128,129] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).