Submitted:

02 July 2025

Posted:

03 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

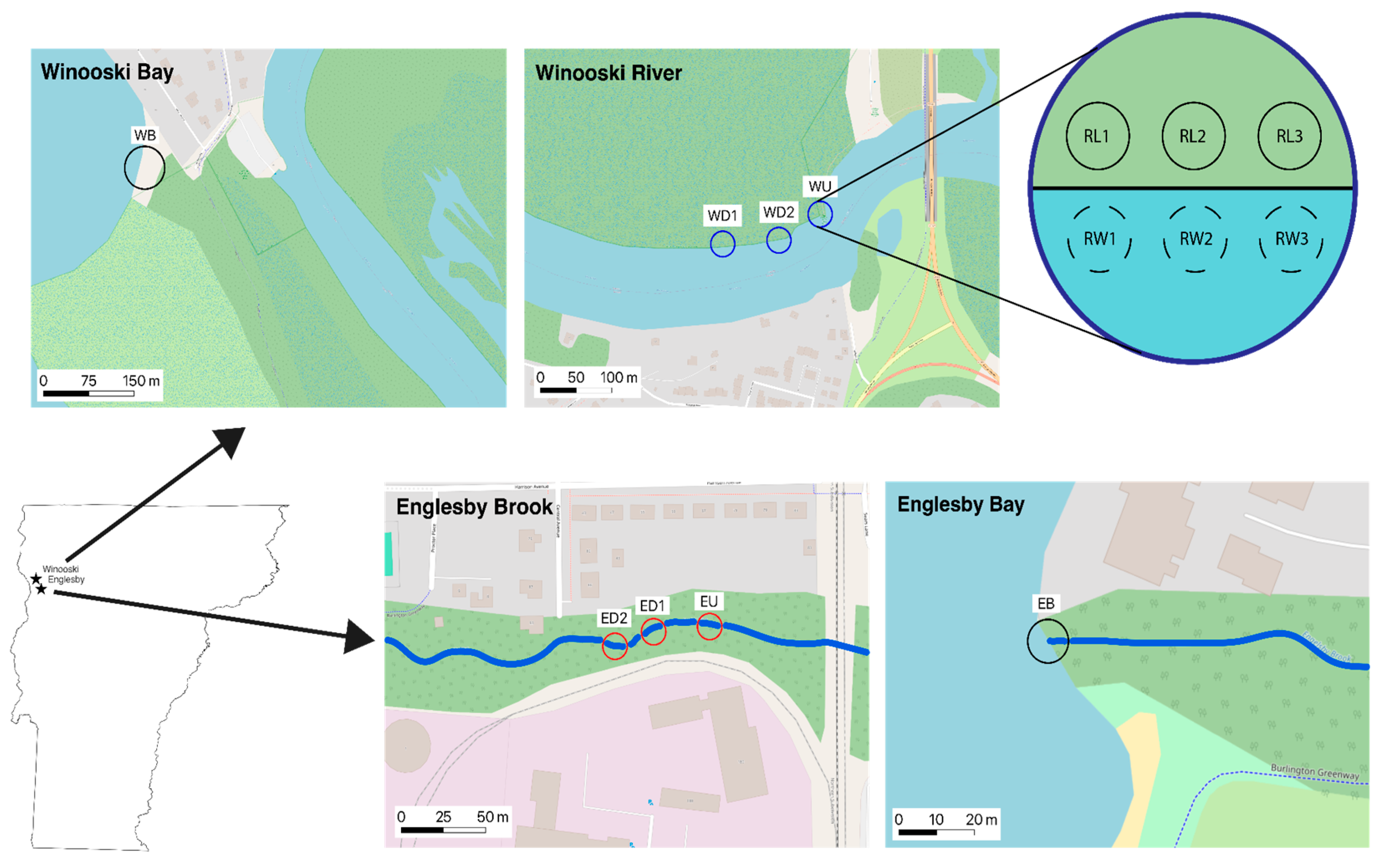

2.1. Experimental Design

2.2. Sample Collection

2.3. Sample Processing and Storage

2.4. DNA Extraction and Sequencing

2.5. Mercury Analysis

2.6. Carbon & Nitrogen (CN) Analysis

2.7. Data Analysis of Elemental Concentrations

2.8. 16S rRNA Amplicon Analysis

2.9. Metagenome Analysis

3. Results

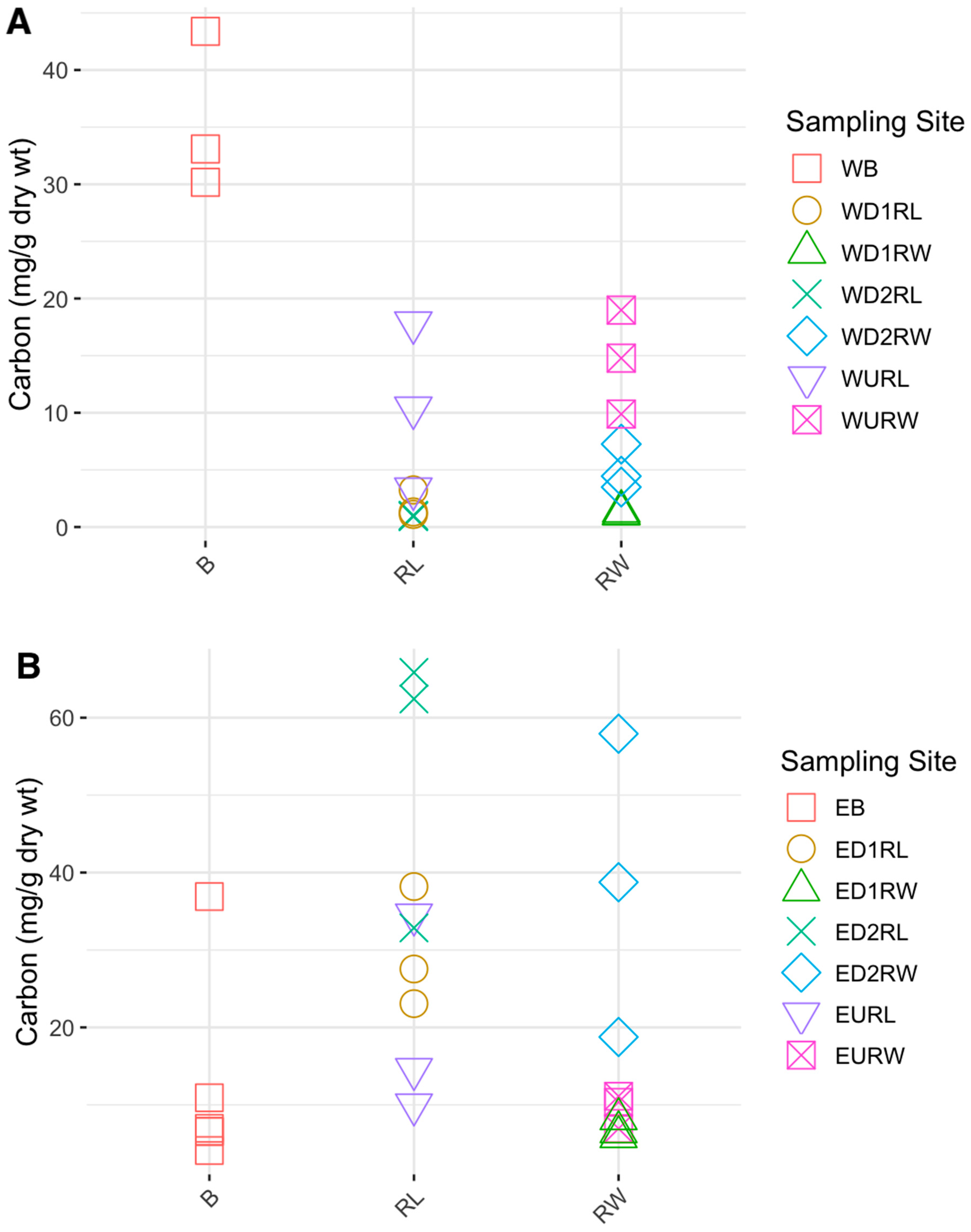

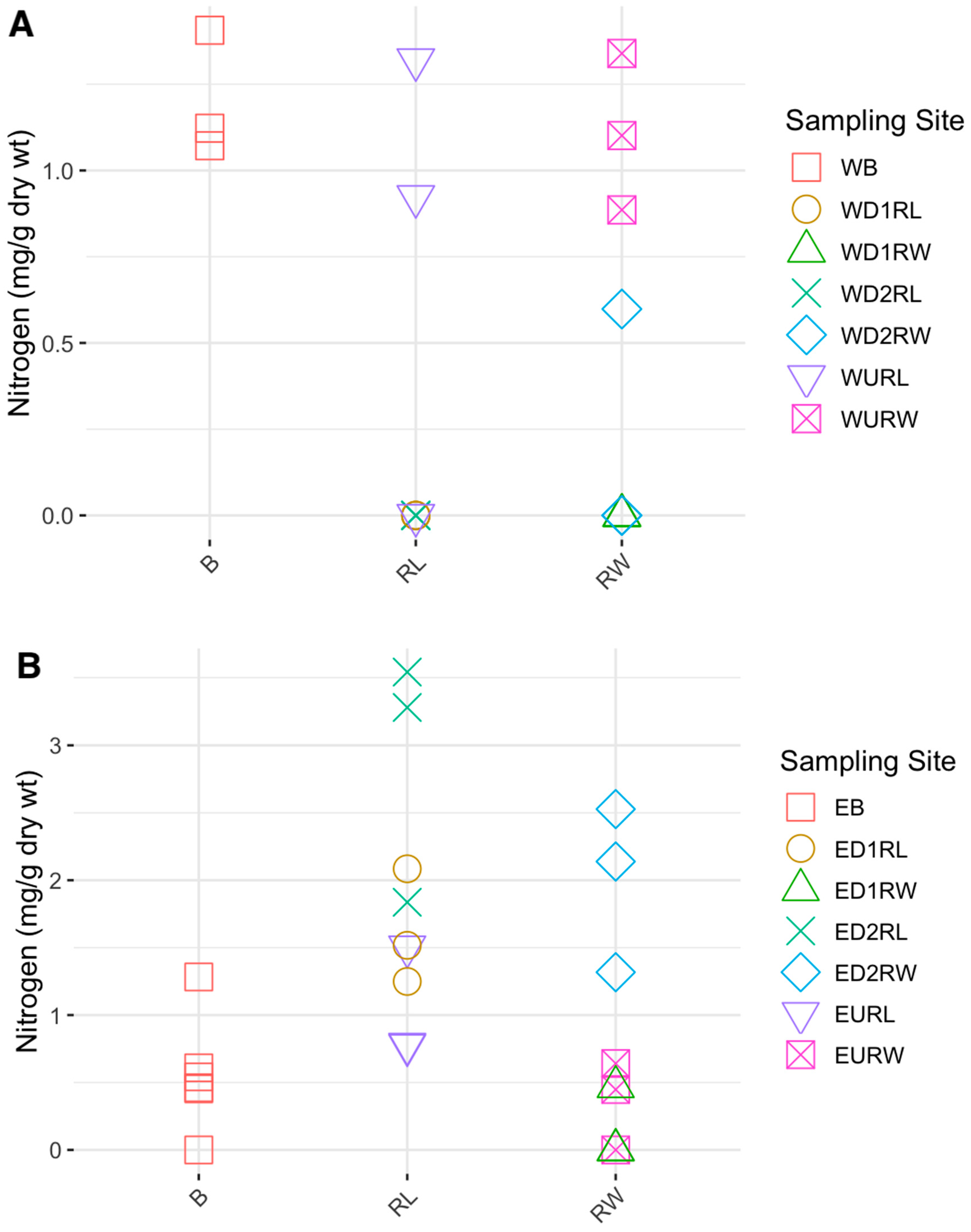

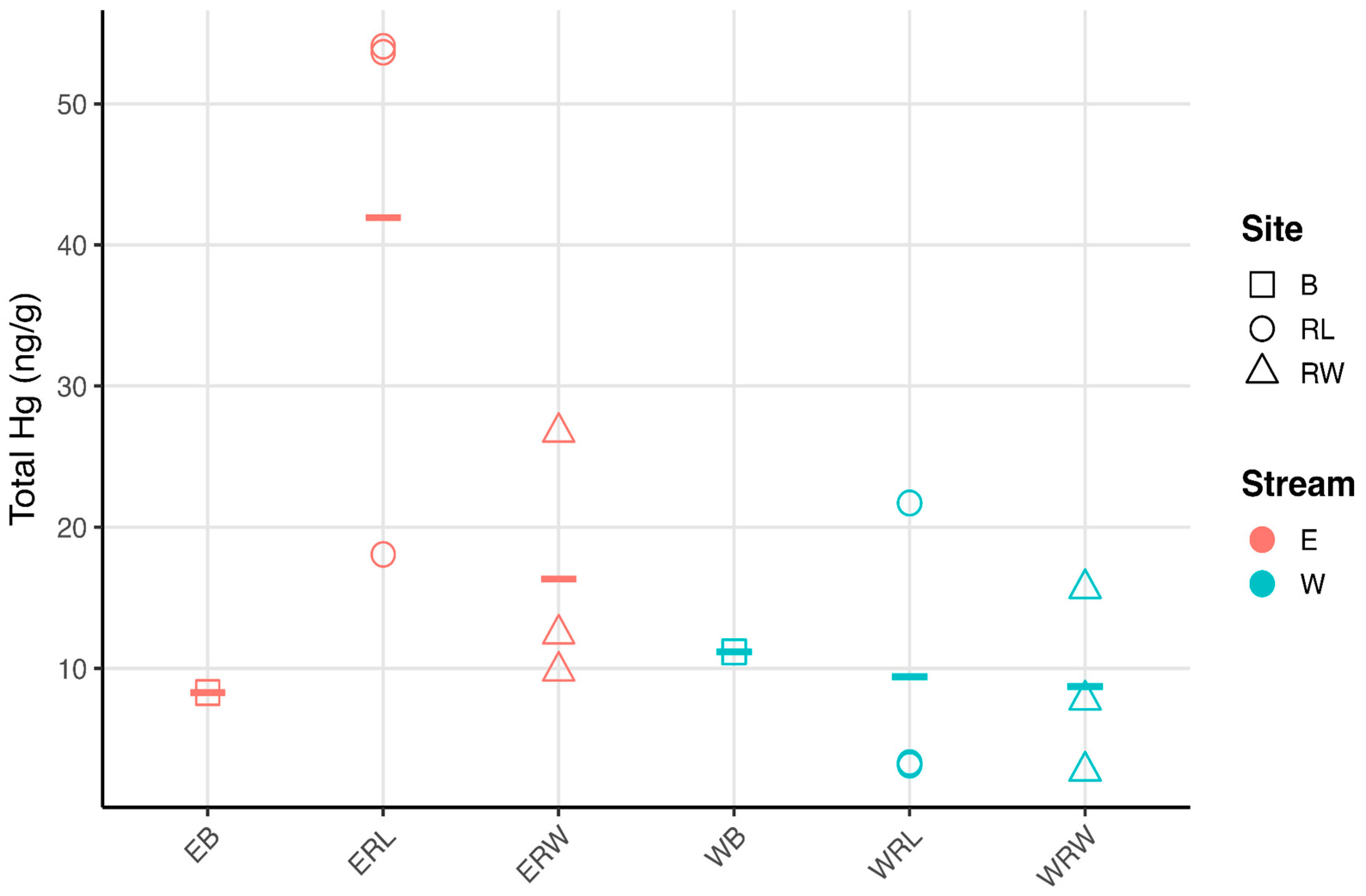

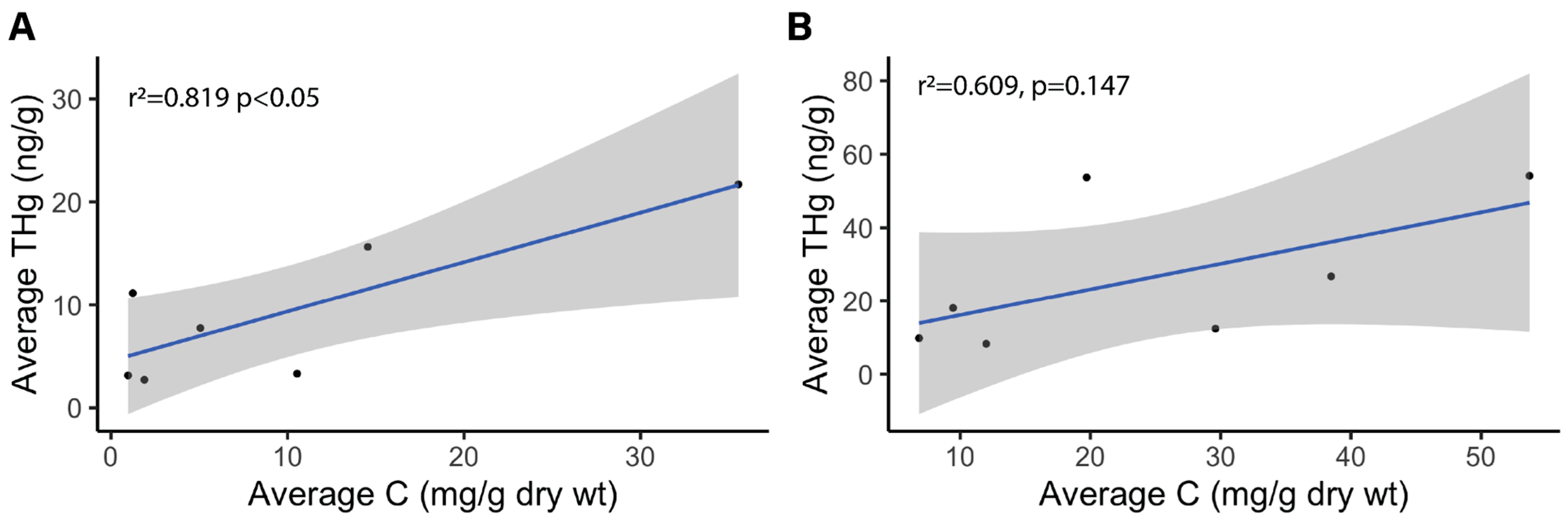

3.1. Carbon, Nitrogen, and Hg Analyses

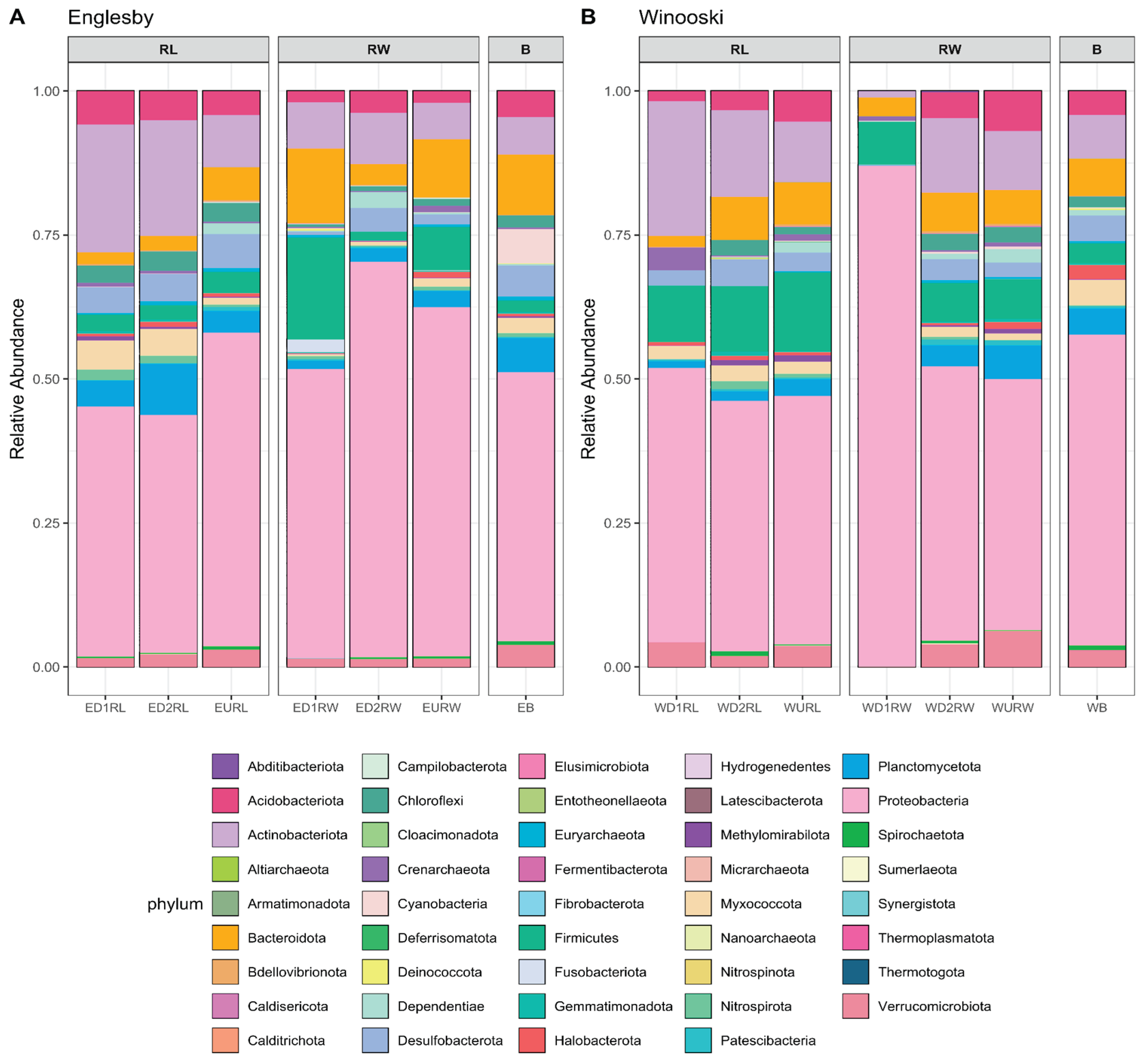

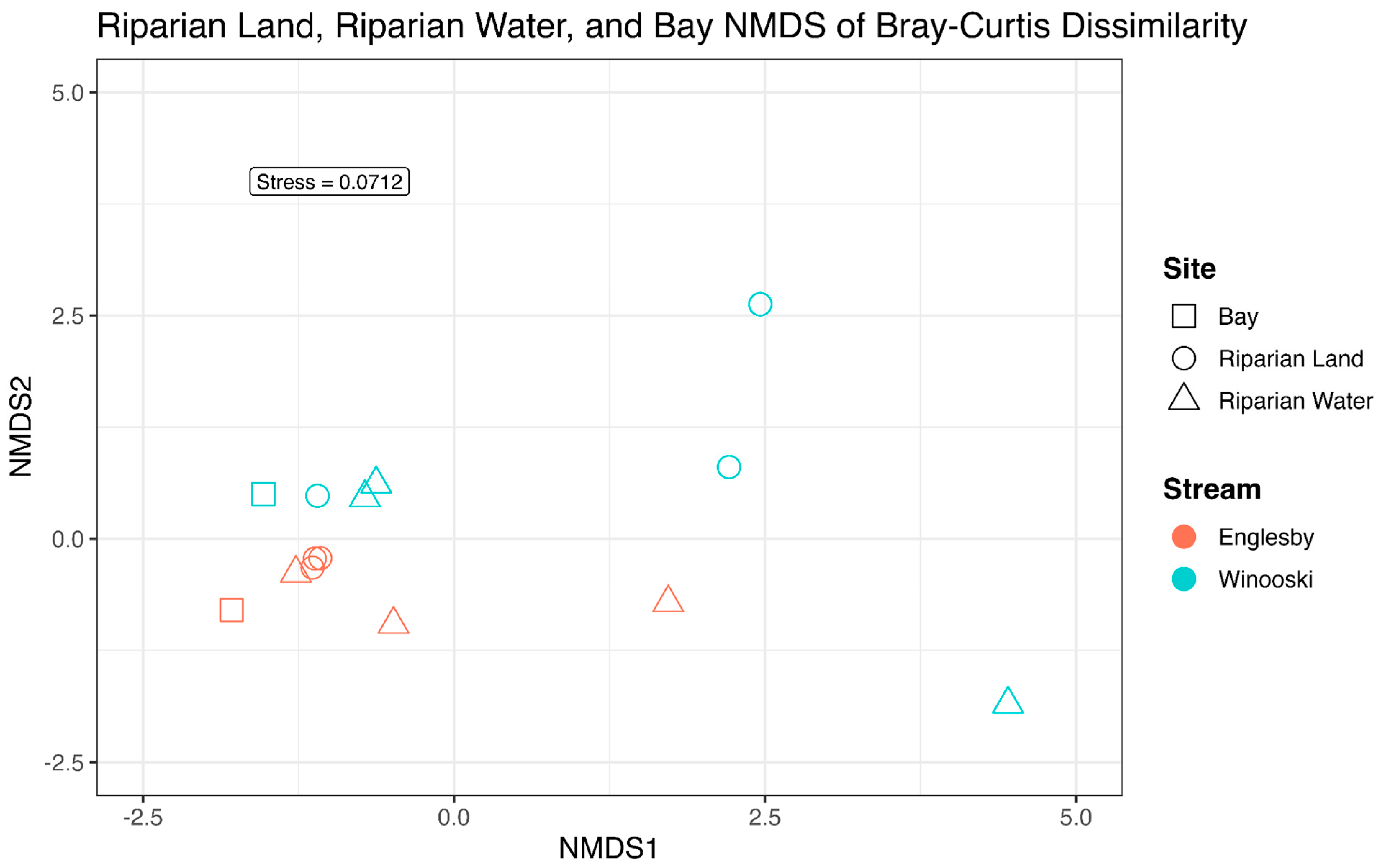

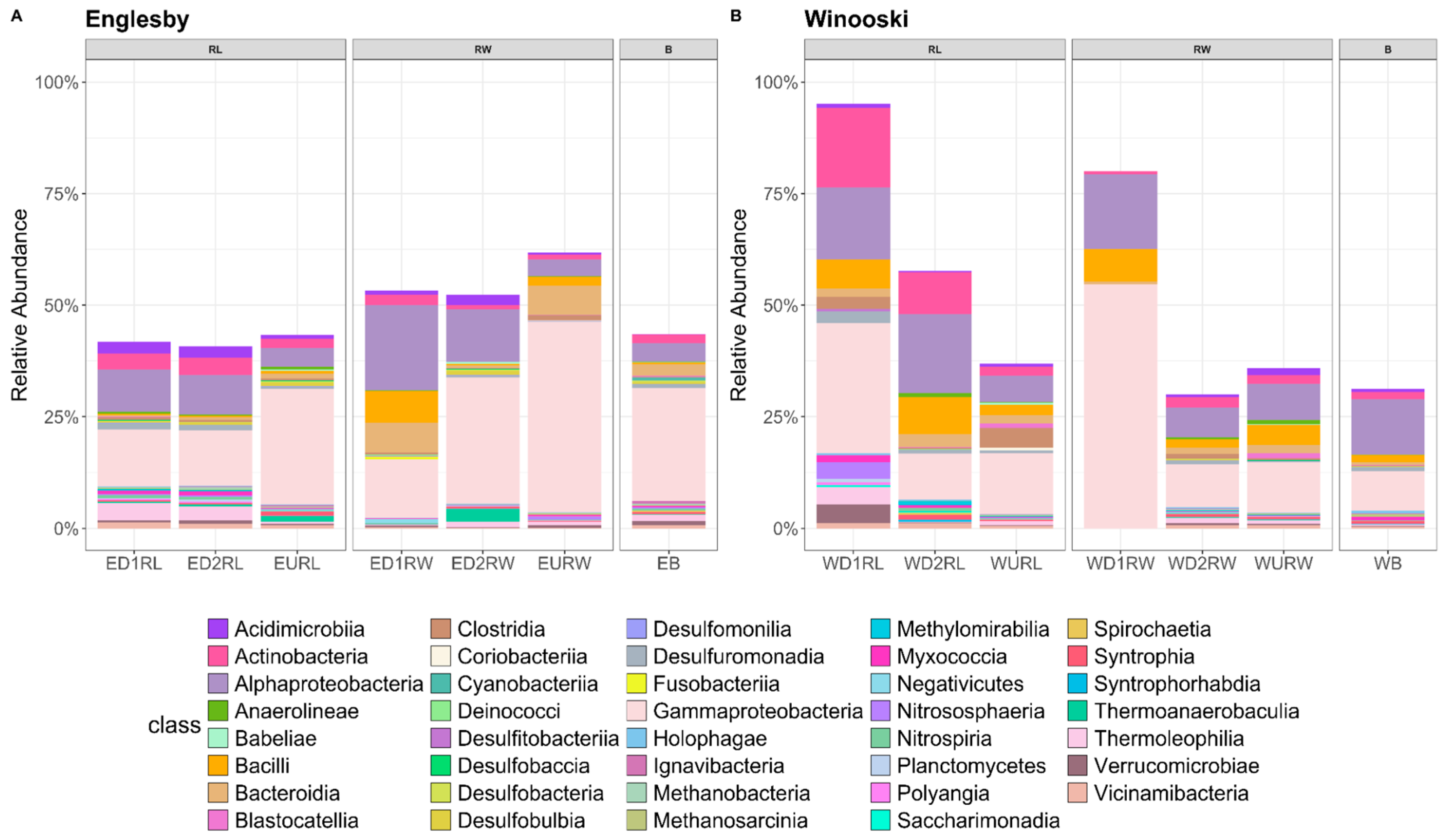

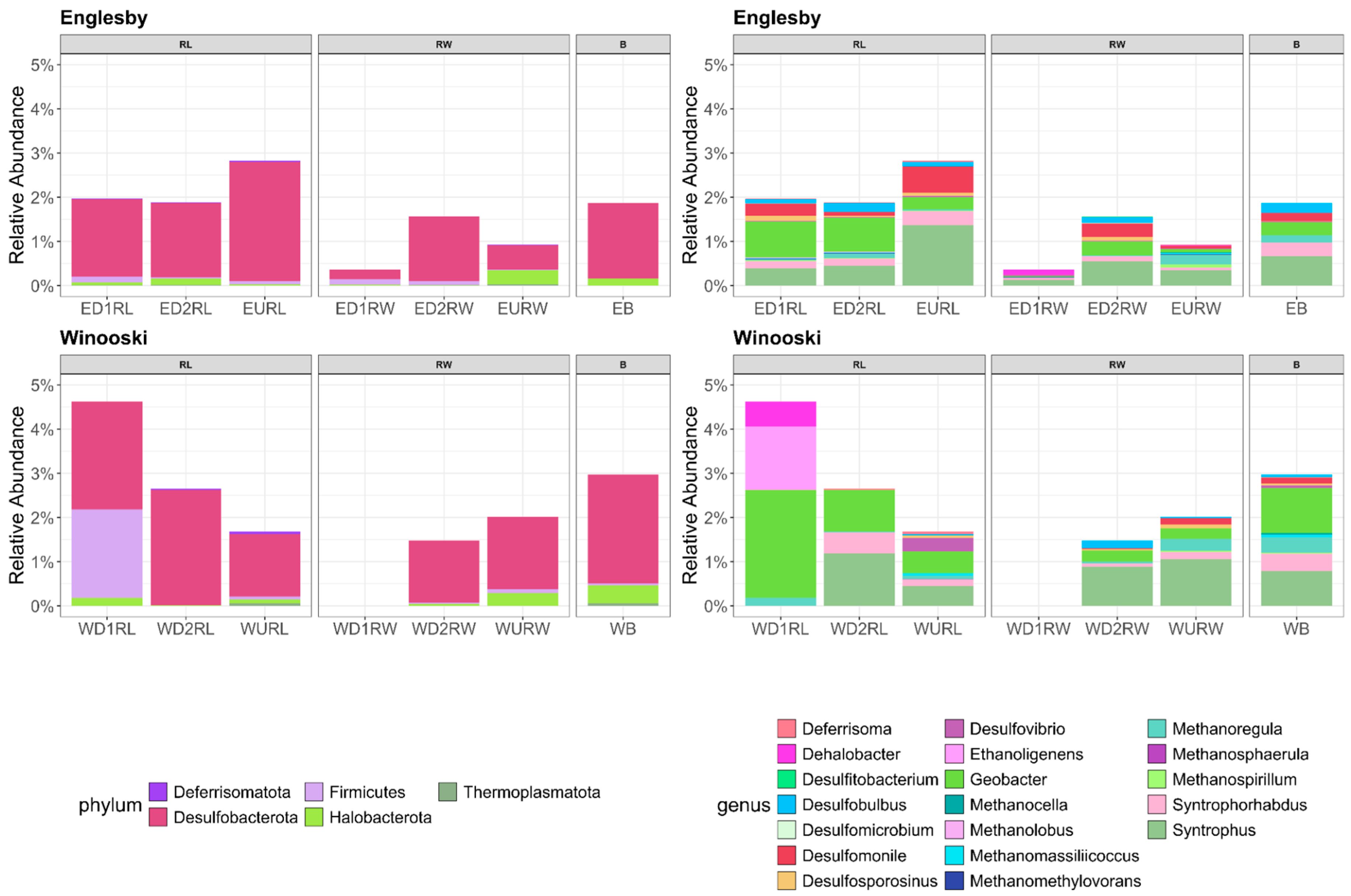

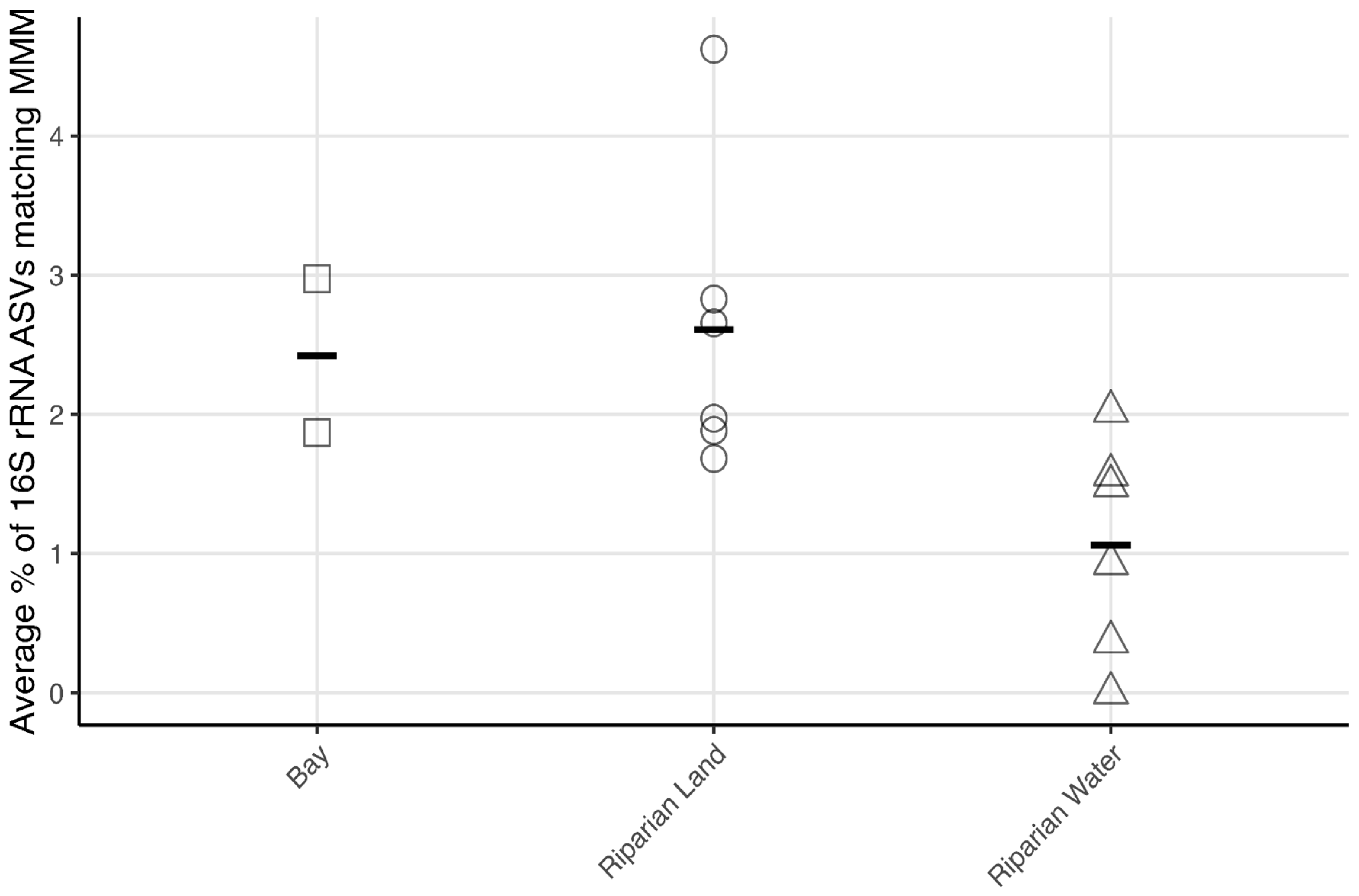

3.2. Microbial Community Structure Based on 16S rRNA

3.3. Metagenome Analysis

4. Discussion

4.1. Mercury Concentrations in Winooski River and Englesby Brook

4.2. Carbon and Nitrogen Concentrations in Winooski River and Englesby Brook

4.3. Microbial Mercury Methylating Potential in Winooski River and Englesby Brook

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A

| Mean (mg/g dry weight) | Standard Deviation (mg/g dry weight) | [THg] Correlation Coefficient | [THg] Correlation p-value | ANOVA of site type (RL, RW, B) p-value | |

| Carbon | 9.97 | 12.4 | 0.819 | 0.02415* | 0.0264* |

| Nitrogen | 0.465 | 0.54 | 0.720 | 0.06799 | 0.3733 |

| Mean (mg/g dry weight) | Standard Deviation (mg/g dry weight) |

[THg] Correlation Coefficient | [THg] Correlation p-value | ANOVA of site type (RL, RW, B) p-value | |

| Carbon | 24.3 | 17.3 | 0.609 | 0.147 | 0.4701 |

| Nitrogen | 1.23 | 0.99 | 0.611 | 0.1448 | 0.4273 |

| Metagenome Sample | Gene Identifier | Taxa | Rank |

| 1 | k127_249317_1/32-98 | unclassified Deltaproteobacteria* (miscellaneous) | class |

| 1 | k127_128388_1/54-88 | unclassified Deltaproteobacteria (miscellaneous) | class |

| 1 | k127_514746_1/32-93 | PVC group | superkingdom |

| 1 | k127_359497_1/14-80 | unclassified Deltaproteobacteria (miscellaneous) | class |

| 1 | k127_115407_1/36-100 | Bacteria | superkingdom |

| 2 | k127_543503_1/64-123 | unclassified Aminicenantes | phylum |

| 2 | k127_113881_1/28-94 | Bacteria candidate phyla | superkingdom |

| 2 | k127_41359_2/81-142 | PVC group | superkingdom |

| 2 | k127_105381_1/6-70 | unclassified Aminicenantes | phylum |

| 2 | k127_518700_1/103-169 | Bacteria candidate phyla | superkingdom |

| 2 | k127_74396_1/69-124 | Bacteria | superkingdom |

| 2 | k127_215905_1/26-92 | Clostridium | genus |

| 2 | k127_377289_2/17-79 | PVC group | superkingdom |

| 2 | k127_558869_1/81-122 | Syntrophus | genus |

| 2 | k127_475689_1/46-112 | Desulfuromonadales | order |

| 2 | k127_71277_1/71-134 | Bacteria | superkingdom |

| 3 | k127_871999_2/119-181 | Bacteria | superkingdom |

| 3 | k127_227989_1/42-99 | PVC group | superkingdom |

| 3 | k127_183458_1/81-107 | unclassified Nitrospirae | phylum |

| 3 | k127_534465_1/70-136 | Desulfuromonadales | order |

| 3 | k127_84606_1/76-142 | Geobacter | genus |

| 3 | k127_227221_1/29-92 | PVC group | superkingdom |

| 3 | k127_965374_1/84-113 | Chlorobi | phylum |

| 3 | k127_701156_1/32-97 | Bacteria | superkingdom |

| 3 | k127_773411_1/66-111 | Desulfuromonadaceae | family |

| 3 | k127_559882_1/46-103 | PVC group | superkingdom |

| 3 | k127_476835_1/10-76 | unclassified Syntrophobacterales | order |

| Metagenome Sample | Gene Identifier | Taxa | Rank |

| 3 | k127_137838_1/58-124 | unclassified Deltaproteobacteria (miscellaneous) | class |

| 3 | k127_418219_1/74-109 | unclassified Syntrophobacterales | order |

| 3 | k127_565953_2/4-66 | Bacteria | superkingdom |

| 3 | k127_585427_1/30-87 | PVC group | superkingdom |

| 4 | k127_81980_2/43-107 | PVC group | superkingdom |

| 4 | k127_453491_1/26-87 | PVC group | superkingdom |

| 4 | k127_398936_1/78-113 | unclassified Elusimicrobia | phylum |

| 5 | k127_523515_1/39-100 | PVC group | superkingdom |

| 5 | k127_547747_1/104-158 | Bacteria | superkingdom |

| 5 | k127_245078_1/1-60 | unclassified Bdellovibrionales | order |

| 5 | k127_463503_1/2-50 | unclassified Lentisphaerae (miscellaneous) | phylum |

| 5 | k127_139044_1/77-122 | Desulfobulbaceae | family |

| 6 | k127_701584_1/55-121 | Methanoregula | genus |

| 6 | k127_345503_1/369-433 | Bacteria | superkingdom |

| 6 | k127_250083_1/13-73 | Bacteria | superkingdom |

| 6 | k127_282016_2/2-53 | Bacteria | superkingdom |

| 6 | k127_558855_1/86-152 | unclassified Deltaproteobacteria (miscellaneous) | class |

| 6 | k127_617542_1/81-147 | unclassified Deltaproteobacteria (miscellaneous) | class |

| 6 | k127_203177_1/42-103 | Bacteria | superkingdom |

| Metagenome Sample | Gene Identifier | HgcA Taxonomy | E-value | Percent Identity (%) |

| 1 | k127_249317_1/32-98 | Vicinamibacteria bacterium | 4.00×10-61 | 82.11 |

| 1 | k127_359497_1/14-80 | Thermodesulfobacteriota bacterium | 4.00×10-62 | 93.46 |

| 2 | k127_543503_1/64-123 | Coriobacteriia bacterium | 5.00×10-56 | 73.77 |

| 2 | k127_105381_1/6-70 | Candidatus Desulfaltia sp. | 1.00×10-47 | 79 |

| 2 | k127_475689_1/46-112 | Deltaproteobacteria bacterium* | 2.00×10-63 | 89.47 |

| 3 | k127_183458_1/81-107 | Nitrospirota bacterium | 1.00×10-55 | 80.56 |

| 3 | k127_534465_1/70-136 | Vicinamibacteria bacterium | 3.00×10-80 | 78.12 |

| 3 | k127_965374_1/84-113 | Vicinamibacteria bacterium | 2.00×10-48 | 73.45 |

| 3 | k127_773411_1/66-111 | Coriobacteriia bacterium | 4.00×10-50 | 76.58 |

| 3 | k127_137838_1/58-124 | Planctomycetia bacterium | 5.00×10-87 | 78.92 |

| 3 | k127_418219_1/74-109 | Spriochaetia bacterium | 2.00×10-50 | 75.23 |

| 4 | k127_398936_1/78-113 | Deltaproteobacteria bacterium | 2.00×10-65 | 89.38 |

| 5 | k127_245078_1/1-60 | Vicinamibacteria bacterium | 1.00×10-54 | 93.88 |

| 5 | k127_463503_1/2-50 | Deltaproteobacteria bacterium | 1.00×10-130 | 90.56 |

| 5 | k127_139044_1/77-122 | Desulfobulbus sp. | 4.00×10-74 | 95.08 |

| Sample | Contig Identifier |

HgcA Taxonomy |

E-value |

Percent Identity (%) |

Description |

| 1 | k127_128388_1/54-88 | Smithella sp. PtaU1.Bin162 | 6.00×10-47 | 87.5 | acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase complex subunit gamma |

| k127_514746_1/32-93 | Candidatus Deferrimicrobium sp. | 4.00×10-70 | 95.54 | hypothetical protein | |

| k127_115407_1/36-100 | Desulfobacterales bacterium | 1.00×10-66 | 91.59 | acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase complex subunit gamma | |

| 2 | k127_113881_1/28-94 | Coriobacteriia bacterium | 3.00×10-77 | 82.14 | acetyl-CoaA synthase subunit gamma |

| k127_518700_1/103-169 | Coriobacteriia bacterium | 5.00×10-117 | 79.25 | acetyl-CoaA synthase subunit gamma | |

| k127_215905_1/26-92 | Spirochaetes bacterium | 2.00×10-54 | 71.07 | acetyl-CoaA synthase subunit gamma | |

| k127_558869_1/81-122 | Methanomassiliicoccaceae archaeon | 4.00×10-54 | 69.17 | carbon monoxide dehydrogenase | |

| k127_41359_2/81-142 | Candidatus Deferrimicrobium sp. | 4.00×10-107 | 96.27 | hypothetical protein | |

| k127_74396_1/69-124 | Anaerolineae bacterium | 7.00×10-71 | 82.4 | hypothetical protein | |

| 2 | k127_377289_2/17-79 | Pseudomonadota bacterium | 6.00×10-54 | 97.83 | acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase complex subunit gamma |

| k127_71277_1/71-134 | Thermoleophilia bacterium | 2.00×10-85 | 85.42 | acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase complex subunit gamma | |

| Sample | Contig Identifier |

HgcA Taxonomy |

E-value |

Percent Identity (%) |

Description |

| 3 | k127_84606_1/76-142 | Deltaproteobacteria bacterium | 3.00×10-103 | 76.04 | acetyl-CoaA synthase subunit gamma |

| k127_871999_2/119-181 | Miltoncostaeaceae bacterium | 1.00×10-48 | 82.52 | Fe-S cluster assembly protein SufD | |

| k127_227989_1/42-99 | Thermoproteota archaeon | 6.00×10-66 | 97.25 | acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase complex subunit gamma | |

| k127_227221_1/29-92 | Methanomicrobiales archaeon HGW-Methanomicrobiales-5 | 1.00×10-62 | 92.16 | acetyl-CoA synthase | |

| k127_701156_1/32-97 | Deltaproteobacteria bacterium | 2.00×10-62 | 90.83 | acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase complex subunit gamma | |

| k127_559882_1/46-103 | Candidatus Bathyarchaeia archaeon | 7.00×10-70 | 93.81 | hypothetical protein | |

| k127_476835_1/10-76 | Syntrophus sp. GWC2_56_31 | 4.00×10-81 | 91.85 | acetyl-CoaA synthase subunit gamma | |

| k127_565953_2/4-66 | Deltaproteobacteria bacterium | 6.00×10-39 | 85.33 | acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase complex subunit gamma | |

| k127_585427_1/30-87 | Candidatus Acidoferrales bacterium | 8.00×10-57 | 100 | acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase complex subunit gamma | |

| 4 | k127_81980_2/43-107 | Coriobacteriia bacterium | 1.00×10-64 | 85.34 | acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase complex subunit gamma |

| k127_453491_1/26-87 | Candidatus Deferrimicrobium sp. | 6.00×10-64 | 97.09 | hypothetical protein | |

| Sample | Contig Identifier |

HgcA Taxonomy |

E-value |

Percent Identity (%) |

Description |

| 5 | k127_523515_1/39-100 | Candidatus Deferrimicrobium sp. | 1.00×10-70 | 97.27 | hypothetical protein |

| k127_547747_1/104-158 | Desulfobaccales bacterium | 1.00×10-106 | 98.1 | acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase complex subunit gamma | |

| 6 | k127_617542_1/81-147 | Deltraproteobacteria bacterium | 2×10-128 | 92.27 | hypothetical protein |

| k127_701584_1/55-121 | Methanoregulaceae archaeon | 2.00×10-104 | 89.41 | carbon monoxide dehydrogenase | |

| k127_250083_1/13-73 | Chloroflexota bacterium | 2.00×10-47 | 81.72 | acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase complex subunit gamma | |

| k127_282016_2/2-53 | Rubrobacteridae bacterium | 3.00×10-27 | 77.05 | acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase complex subunit gamma | |

| k127_558855_1/86-152 | Desulfobacteraceae bacterium | 0 | 86.84 | acetyl-CoaA synthase subunit gamma | |

| k127_203177_1/42-103 | Chloroflexota bacterium | 5.00×10-64 | 97.09 | acetyl-CoA decarbonylase/synthase complex subunit gamma |

References

- Morel, F.M.M.; Kraepiel, A.M.L.; Amyot, M. The Chemical Cycle and Bioaccumulation of Mercury. Annu. Rev. Ecol. Syst. 1998, 29, 543–566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.Y.; Driscoll, C.T.; Eagles-Smith, C.A.; Eckley, C.S.; Gay, D.A.; Hsu-Kim, H.; Keane, S.E.; Kirk, J.L.; Mason, R.P.; Obrist, D.; et al. A Critical Time for Mercury Science to Inform Global Policy. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2018, 52, 9556–9561. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Basu, N.; Bastiansz, A.; Dórea, J.G.; Fujimura, M.; Horvat, M.; Shroff, E.; Weihe, P.; Zastenskaya, I. Our Evolved Understanding of the Human Health Risks of Mercury. Ambio 2023, 52, 877–896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tong, S.; Li, H.; Wang, L.; Tudi, M.; Yang, L. Concentration, Spatial Distribution, Contamination Degree and Human Health Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Urban Soils across China between 2003 and 2019—A Systematic Review. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public. Health 2020, 17, 3099. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brahmstedt, E.S.; Zhou, H.; Eggleston, E.M.; Holsen, T.M.; Twiss, M.R. Assessment of Mercury Mobilization Potential in Upper St. Lawrence River Riparian Wetlands under New Water Level Regulation Management. J. Gt. Lakes Res. 2019, 45, 735–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leclerc, M.; Harrison, M.C.; Storck, V.; Planas, D.; Amyot, M.; Walsh, D.A. Microbial Diversity and Mercury Methylation Activity in Periphytic Biofilms at a Run-of-River Hydroelectric Dam and Constructed Wetlands. mSphere 2021, 6, e00021-21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Paranjape, A.R.; Hall, B.D. Recent Advances in the Study of Mercury Methylation in Aquatic Systems. FACETS 2017, 2, 85–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eckley, C.S.; Hintelmann, H. Determination of Mercury Methylation Potentials in the Water Column of Lakes across Canada. Sci. Total Environ. 2006, 368, 111–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regnell, O.; Elert, M.; Höglund, L.O.; Falk, A.H.; Svensson, A. Linking Cellulose Fiber Sediment Methyl Mercury Levels to Organic Matter Decay and Major Element Composition. AMBIO 2014, 43, 878–890. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watras, C.; Bloom, N.S. The Vertical Distribution of Mercury Species in Wisconsin Lake: Accumulation in Plankton Layers. In; 1994; pp. 137–152 ISBN 978-1-56670-066-5.

- Graham, A.M.; Bullock, A.L.; Maizel, A.C.; Elias, D.A.; Gilmour, C.C. Detailed Assessment of the Kinetics of Hg-Cell Association, Hg Methylation, and Methylmercury Degradation in Several Desulfovibrio Species. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2012, 78, 7337–7346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamdy, M.K.; Noyes, O.R. Formation of Methyl Mercury by Bacteria. Appl. Microbiol. 1975, 30, 424–432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Silver, S.; Phung, L.T. A Bacterial View of the Periodic Table: Genes and Proteins for Toxic Inorganic Ions. J. Ind. Microbiol. Biotechnol. 2005, 32, 587–605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parks, J.M.; Johs, A.; Podar, M.; Bridou, R.; Hurt, R.A.; Smith, S.D.; Tomanicek, S.J.; Qian, Y.; Brown, S.D.; Brandt, C.C.; et al. The Genetic Basis for Bacterial Mercury Methylation. Science 2013, 339, 1332–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilmour, C.C.; Elias, D.A.; Kucken, A.M.; Brown, S.D.; Palumbo, A.V.; Schadt, C.W.; Wall, J.D. Sulfate-Reducing Bacterium Desulfovibrio Desulfuricans ND132 as a Model for Understanding Bacterial Mercury Methylation. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2011, 77, 3938–3951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Compeau, G.C.; Bartha, R. Sulfate-Reducing Bacteria: Principal Methylators of Mercury in Anoxic Estuarine Sediment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1985, 50, 498–502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Choi, S.-C.; Chase, T.; Bartha, R. Metabolic Pathways Leading to Mercury Methylation in Desulfovibrio Desulfuricans LS. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1994, 60, 4072–4077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Regnell, O.; Watras, Carl. J. Microbial Mercury Methylation in Aquatic Environments: A Critical Review of Published Field and Laboratory Studies. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 4–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Qian, C.; Johs, A.; Chen, H.; Mann, B.F.; Lu, X.; Abraham, P.E.; Hettich, R.L.; Gu, B. Global Proteome Response to Deletion of Genes Related to Mercury Methylation and Dissimilatory Metal Reduction Reveals Changes in Respiratory Metabolism in Geobacter Sulfurreducens PCA. J. Proteome Res. 2016, 15, 3540–3549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gilmour, C.C.; Podar, M.; Bullock, A.L.; Graham, A.M.; Brown, S.D.; Somenahally, A.C.; Johs, A.; Hurt, R.A.Jr.; Bailey, K.L.; Elias, D.A. Mercury Methylation by Novel Microorganisms from New Environments. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 11810–11820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Eckley, C.S.; Luxton, T.P.; McKernan, J.L.; Goetz, J.; Goulet, J. Influence of Reservoir Water Level Fluctuations on Sediment Methylmercury Concentrations Downstream of the Historical Black Butte Mercury Mine, OR. Appl. Geochem. 2015, 61, 284–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sorensen, J.A.; Kallemeyn, L.W.; Sydor, M. Relationship between Mercury Accumulation in Young-of-the-Year Yellow Perch and Water-Level Fluctuations. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2005, 39, 9237–9243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Watras, C.J.; Morrison, K.A. The Response of Two Remote, Temperate Lakes to Changes in Atmospheric Mercury Deposition, Sulfate, and the Water Cycle. Can. J. Fish. Aquat. Sci. 2008, 65, 100–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, T.L.; Olson, S.A.; LeNoir, J.M.; Kalmon, R.D.; Ahearn, E.A. Flood of July 2023 in Vermont, U.S. Geological Survey, 2025.

- Chen, C.; Kamman, N.; Williams, J.; Bugge, D.; Taylor, V.; Jackson, B.; Miller, E. Spatial and Temporal Variation in Mercury Bioaccumulation by Zooplankton in Lake Champlain (North America). Environ. Pollut. 2012, 161, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanley, J.B.; Chalmers, A.T. Streamwater Fluxes of Total Mercury and Methylmercury into and out of Lake Champlain. Environ. Pollut. 2012, 161, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation Bacteria TMDL Englesby Brook. 2011.

- Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation 2018 Winooski River TBP. 2018.

- National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Water Prediction Service Available online: https://water.weather.gov/ahps2/.

- Christensen, G.A.; Wymore, A.M.; King, A.J.; Podar, M.; Hurt, R.A.; Santillan, E.U.; Soren, A.; Brandt, C.C.; Brown, S.D.; Palumbo, A.V.; et al. Development and Validation of Broad-Range Qualitative and Clade-Specific Quantitative Molecular Probes for Assessing Mercury Methylation in the Environment. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2016, 82, 6068–6078. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-R.; Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Bi, L.; Zhu, J.; He, J.-Z. Consistent Responses of Soil Microbial Taxonomic and Functional Attributes to Mercury Pollution across China. Microbiome 2018, 6, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- McDaniel, E.A.; Peterson, B.D.; Stevens, S.L.R.; Tran, P.Q.; Anantharaman, K.; McMahon, K.D. Expanded Phylogenetic Diversity and Metabolic Flexibility of Mercury-Methylating Microorganisms. mSystems 2020, 5, 10.1128/msystems.00299-20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- U.S. Census Bureau US Regions Boundary File [Cb_2018_us_region_20m.Zip] 2018.

- QGIS Development Team QGIS Geographic Information System.

- Salter, S.J.; Cox, M.J.; Turek, E.M.; Calus, S.T.; Cookson, W.O.; Moffatt, M.F.; Turner, P.; Parkhill, J.; Loman, N.J.; Walker, A.W. Reagent and Laboratory Contamination Can Critically Impact Sequence-Based Microbiome Analyses. BMC Biol. 2014, 12, 87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wickham, H.; François, R.; Henry, L.; Müller, K.; Vaughan, D.; Software, P. ; PBC Dplyr: A Grammar of Data Manipulation 2023.

- R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing 2024.

- Fox, J.; Weisberg, S.; Price, B.; Adler, D.; Bates, D.; Baud-Bovy, G.; Bolker, B.; Ellison, S.; Firth, D.; Friendly, M.; et al. Car: Companion to Applied Regression 2024.

- Callahan, B.J.; McMurdie, P.J.; Rosen, M.J.; Han, A.W.; Johnson, A.J.A.; Holmes, S.P. DADA2: High-Resolution Sample Inference from Illumina Amplicon Data. Nat. Methods 2016, 13, 581–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wright, E.S. Using DECIPHER v2.0 to Analyze Big Biological Sequence Data in R. R J. 2016, 8, 352–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McMurdie, P.J.; Holmes, S. Phyloseq: An R Package for Reproducible Interactive Analysis and Graphics of Microbiome Census Data. PLOS ONE 2013, 8, e61217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parks, J.M.; Johs, A.; Podar, M.; Bridou, R.; Hurt, R.A.; Smith, S.D.; Tomanicek, S.J.; Qian, Y.; Brown, S.D.; Brandt, C.C.; et al. The Genetic Basis for Bacterial Mercury Methylation. Science 2013, 339, 1332–1335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bolger, A.M.; Lohse, M.; Usadel, B. Trimmomatic: A Flexible Trimmer for Illumina Sequence Data. Bioinforma. Oxf. Engl. 2014, 30, 2114–2120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, D.; Liu, C.-M.; Luo, R.; Sadakane, K.; Lam, T.-W. MEGAHIT: An Ultra-Fast Single-Node Solution for Large and Complex Metagenomics Assembly via Succinct de Bruijn Graph. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1674–1676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hyatt, D.; Chen, G.-L.; LoCascio, P.F.; Land, M.L.; Larimer, F.W.; Hauser, L.J. Prodigal: Prokaryotic Gene Recognition and Translation Initiation Site Identification. BMC Bioinformatics 2010, 11, 119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, R.D.; Clements, J.; Eddy, S.R. HMMER Web Server: Interactive Sequence Similarity Searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, W29-37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gionfriddo, C.; Podar, M.; Gilmour, C.; Pierce, E.; Elias, D. ORNL Compiled Mercury Methylator Database; ORNLCIFSFA (Critical Interfaces Science Focus Area); Oak Ridge National Lab. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Altschul, S.F.; Gish, W.; Miller, W.; Myers, E.W.; Lipman, D.J. Basic Local Alignment Search Tool. J. Mol. Biol. 1990, 215, 403–410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schartup, A.T.; Mason, R.P.; Balcom, P.H.; Hollweg, T.A.; Chen, C.Y. Methylmercury Production in Estuarine Sediments: Role of Organic Matter. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 695–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, C.; Kamman, N.; Williams, J.; Bugge, D.; Taylor, V.; Jackson, B.; Miller, E. Spatial and Temporal Variation in Mercury Bioaccumulation by Zooplankton in Lake Champlain (North America). Environ. Pollut. 2012, 161, 343–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Keeler, G.J.; Gratz, L.E.; Al-wali, K. Long-Term Atmospheric Mercury Wet Deposition at Underhill, Vermont. Ecotoxicology 2005, 14, 71–83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bradley, P.M.; Journey, C.A.; Chapelle, F.H.; Lowery, M.A.; Conrads, P.A. Flood Hydrology and Methylmercury Availability in Coastal Plain Rivers. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2010, 44, 9285–9290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shanley, J.B.; Chalmers, A.T. Streamwater Fluxes of Total Mercury and Methylmercury into and out of Lake Champlain. Environ. Pollut. 2012, 161, 311–320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shrestha, J.; Niklaus, P. a.; Frossard, E.; Samaritani, E.; Huber, B.; Barnard, R.L.; Schleppi, P.; Tockner, K.; Luster, J. Soil Nitrogen Dynamics in a River Floodplain Mosaic. J. Environ. Qual. 2012, 41, 2033–2045. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Furutani, A.; Rudd, J.W.M. Measurement of Mercury Methylation in Lake Water and Sediment Samples. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 1980, 40, 770–776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu-Kim, H.; Kucharzyk, K.H.; Zhang, T.; Deshusses, M.A. Mechanisms Regulating Mercury Bioavailability for Methylating Microorganisms in the Aquatic Environment: A Critical Review. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2013, 47, 2441–2456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Begmatov, S.; Savvichev, A.S.; Kadnikov, V.V.; Beletsky, A.V.; Rusanov, I.I.; Klyuvitkin, A.A.; Novichkova, E.A.; Mardanov, A.V.; Pimenov, N.V.; Ravin, N.V. Microbial Communities Involved in Methane, Sulfur, and Nitrogen Cycling in the Sediments of the Barents Sea. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2362. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yuan, K.; Chen, X.; Chen, P.; Huang, Y.; Jiang, J.; Luan, T.; Chen, B.; Wang, X. Mercury Methylation-Related Microbes and Genes in the Sediments of the Pearl River Estuary and the South China Sea. Ecotoxicol. Environ. Saf. 2019, 185, 109722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kristensen, J.M.; Singleton, C.; Clegg, L.-A.; Petriglieri, F.; Nielsen, P.H. High Diversity and Functional Potential of Undescribed “Acidobacteriota” in Danish Wastewater Treatment Plants. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 12, 643950. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bae, H.-S.; Dierberg, F.E.; Ogram, A. Syntrophs Dominate Sequences Associated with the Mercury Methylation-Related Gene hgcA in the Water Conservation Areas of the Florida Everglades. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 6517–6526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kerin, E.J.; Gilmour, C.C.; Roden, E.; Suzuki, M.T.; Coates, J.D.; Mason, R.P. Mercury Methylation by Dissimilatory Iron-Reducing Bacteria. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2006, 72, 7919–7921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Czech, L.; Stamatakis, A.; Dunthorn, M.; Barbera, P. Metagenomic Analysis Using Phylogenetic Placement—A Review of the First Decade. Front. Bioinforma. 2022, 2, 871393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Matsen, F.A.; Kodner, R.B.; Armbrust, E.V. Pplacer: Linear Time Maximum-Likelihood and Bayesian Phylogenetic Placement of Sequences onto a Fixed Reference Tree. BMC Bioinformatics 2010, 11, 538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, B.; Lu, C.; Wang, Y.; Yu, J.; Zhao, K.; Xue, R.; Ren, H.; Lv, X.; Pan, R.; Zhang, J.; et al. Author Correction: A Genomic Catalogue of Soil Microbiomes Boosts Mining of Biodiversity and Genetic Resources. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 8079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Huber, K.; Overmann, J. Vicinamibacteraceae Fam. Nov., the First Described Family within the Subdivision 6 Acidobacteria. Int. J. Syst. Evol. Microbiol. 2018, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dedysh, S.N.; Ivanova, A.A.; Begmatov, Sh.A.; Beletsky, A.V.; Rakitin, A.L.; Mardanov, A.V.; Philippov, D.A.; Ravin, N.V. Acidobacteria in Fens: Phylogenetic Diversity and Genome Analysis of the Key Representatives. Microbiology 2022, 91, 662–670. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, Y.; An, M.; Anwar, T.; Wang, H. Differences in Soil Bacterial Community Structure during the Remediation of Cd-Polluted Cotton Fields by Biochar and Biofertilizer in Xinjiang, China. Front. Microbiol. 2024, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-R.; Zheng, Y.-M.; Zhang, L.-M.; He, J.-Z. Linkage between Community Diversity of Sulfate-Reducing Microorganisms and Methylmercury Concentration in Paddy Soil. Environ. Sci. Pollut. Res. 2014, 21, 1339–1348. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.-R.; Yu, R.-Q.; Zheng, Y.-M.; He, J.-Z. Analysis of the Microbial Community Structure by Monitoring an Hg Methylation Gene (hgcA) in Paddy Soils along an Hg Gradient. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2014, 80, 2874–2879. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schoch, C.L.; Ciufo, S.; Domrachev, M.; Hotton, C.L.; Kannan, S.; Khovanskaya, R.; Leipe, D.; Mcveigh, R.; O’Neill, K.; Robbertse, B.; et al. NCBI Taxonomy: A Comprehensive Update on Curation, Resources and Tools. Database J. Biol. Databases Curation 2020, 2020, baaa062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).