Submitted:

26 June 2025

Posted:

03 July 2025

Read the latest preprint version here

Abstract

Keywords:

Introduction

2. Multiple Sclerosis

3. Epidemiological Studies: Faroe Islands.

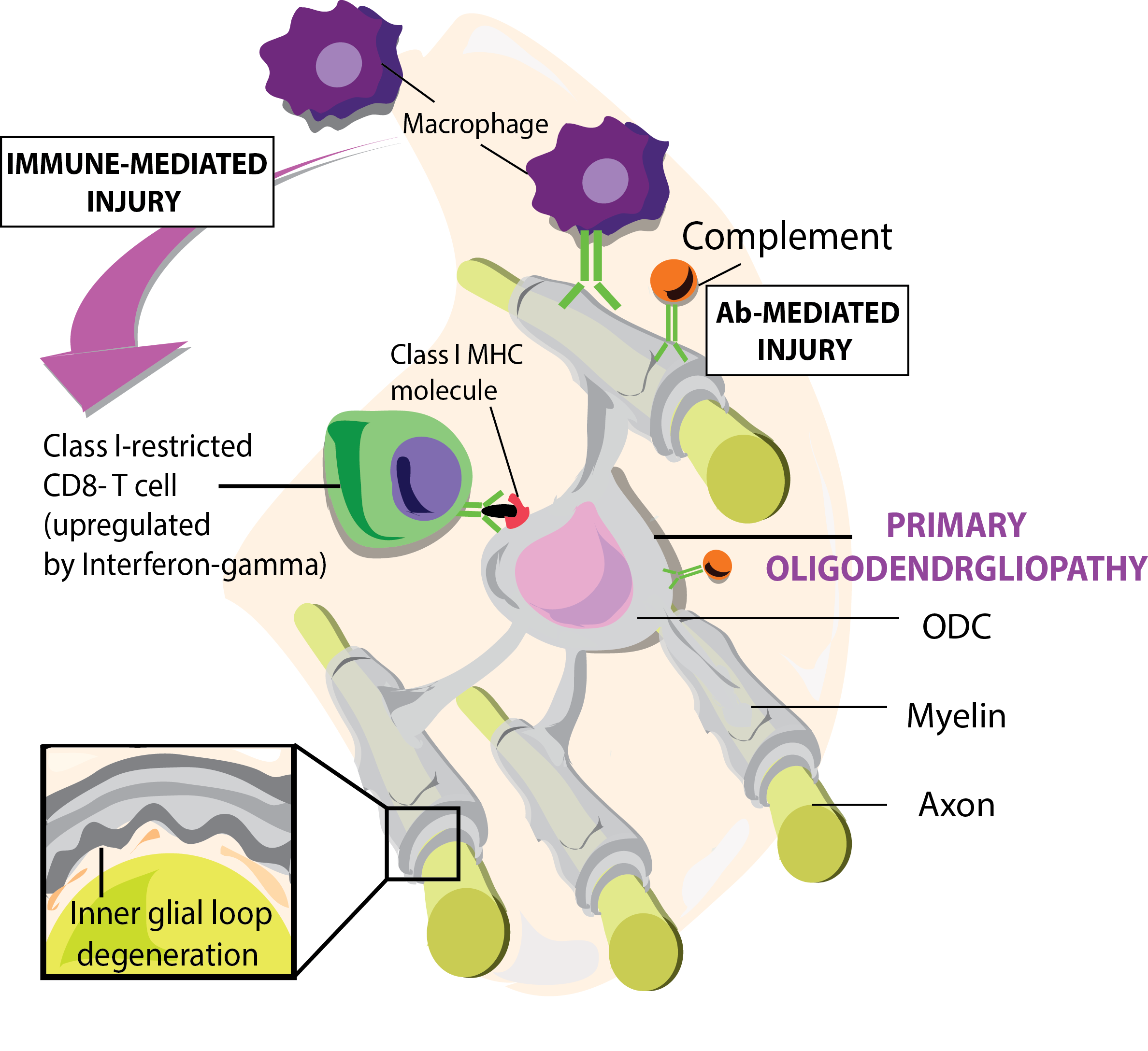

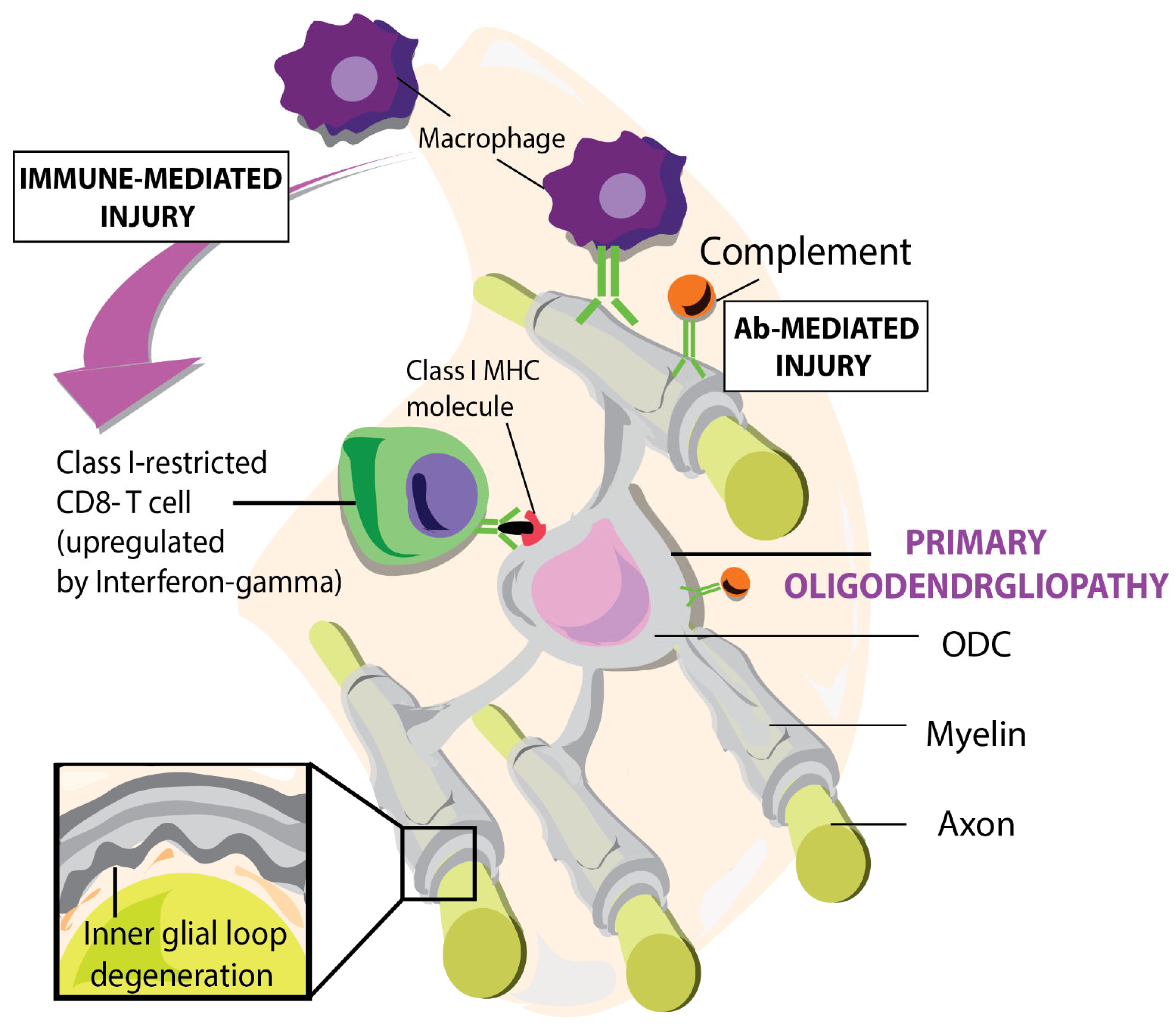

4. The Autoimmune Concept of MS; the Main Immune Players.

5. Earliest Morphological Changes in MS Lesions

6. Immune Responses

7. Mechanisms of Autoimmunity and Neurodegeneration Antigen Release and Immune

7-1. Activation:

7-2. Bystander Toxicity:

8. The Outside-in Pathogenic Concept and Supporting Animal Models

9. Early changes in NAWM.

10. The Proverbial Primary Lesion

11. A Case for HHV-6

12. Blistering of Myelin

12-1. Citrullination of Myelin

12-2. Citrullination as Result of an Immune Response in the CNS

12-3. Citrullinated MBP and Astrocyte Dysregulation

13. EAE MS Animal Models

13-1. EAE.

13-2. TMEV EAE Animal Models

13-3. Non-Human Primate EAE

13-4. HHV-6A

14. Citrullination of Myelin and HHV6-A

15. HHV-6 and Immune Deficiency in MS patients

16. CNS Antigen Drainage in Cervical Lymph Nodes.

17. MS as a Tripartite of Herpesviruses (CMV, EBV, HHV6).

18. Consequences for the Therapeutic Approach to the Disease.

19. Future Research Directions

References

- Constantinescu CS, Farooqi N, O'Brien K, Gran B. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) as a model for multiple sclerosis (MS). British Journal of Pharmacology. 2011;164(4):1079-106.

- Wilkin TJ. The primary lesion theory of autoimmunity: a speculative hypothesis. Autoimmunity. 1990;7(4):225-35.

- Rosenblum MD, Remedios KA, Abbas AK. Mechanisms of human autoimmunity. J Clin Invest. 2015;125(6):2228-33.

- t Hart BA, Luchicchi A, Schenk GJ, Stys PK, Geurts JJG. Mechanistic underpinning of an inside-out concept for autoimmunity in multiple sclerosis. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2021;8(8):1709-19.

- Papiri G, D'Andreamatteo G, Cacchiò G, Alia S, Silvestrini M, Paci C, et al. Multiple Sclerosis: Inflammatory and Neuroglial Aspects. Curr Issues Mol Biol. 2023;45(2):1443-70.

- Pender MP, Burrows SR. Epstein-Barr virus and multiple sclerosis: potential opportunities for immunotherapy. Clin Transl Immunology. 2014;3(10):e27.

- Goverman J. Autoimmune T cell responses in the central nervous system. Nat Rev Immunol. 2009;9(6):393-407.

- Goris A, Vandebergh M, McCauley JL, Saarela J, Cotsapas C. Genetics of multiple sclerosis: lessons from polygenicity. The Lancet Neurology. 2022;21(9):830-42.

- Kurtzke JF, Hyllested K. Multiple sclerosis in the Faroe Islands. Neurology. 1986;36(3):307-.

- Ascherio A, Munger KL. Environmental risk factors for multiple sclerosis. Part I: the role of infection. Ann Neurol. 2007;61(4):288-99.

- Simpson S, Jr., Taylor B, Blizzard L, Ponsonby AL, Pittas F, Tremlett H, et al. Higher 25-hydroxyvitamin D is associated with lower relapse risk in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 2010;68(2):193-203.

- Hemmer B, Kerschensteiner M, Korn T. Role of the innate and adaptive immune responses in the course of multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(4):406-19.

- Bar-Or A, Fawaz L, Fan B, Darlington PJ, Rieger A, Ghorayeb C, et al. Abnormal B-cell cytokine responses a trigger of T-cell-mediated disease in MS? Ann Neurol. 2010;67(4):452-61.

- Prinz M, Jung S, Priller J. Microglia Biology: One Century of Evolving Concepts. Cell. 2019;179(2):292-311.

- Ransohoff RM. How neuroinflammation contributes to neurodegeneration. Science. 2016;353(6301):777-83.

- Li Q, Barres BA. Microglia and macrophages in brain homeostasis and disease. Nat Rev Immunol. 2018;18(4):225-42.

- Zhang Y, Chen K, Sloan SA, Bennett ML, Scholze AR, Keeffe S, et al. An RNA-Sequencing Transcriptome and Splicing Database of Glia, Neurons, and Vascular Cells of the Cerebral Cortex. The Journal of Neuroscience. 2014;34(36):11929.

- Zhang X, Chen F, Sun M, Wu N, Liu B, Yi X, et al. Microglia in the context of multiple sclerosis. Front Neurol. 2023;14:1157287.

- Titus HE, Chen Y, Podojil JR, Robinson AP, Balabanov R, Popko B, Miller SD. Pre-clinical and Clinical Implications of “Inside-Out” vs. “Outside-In” Paradigms in Multiple Sclerosis Etiopathogenesis. Frontiers in Cellular Neuroscience. 2020;Volume 14 - 2020.

- Goodin DS, Khankhanian P, Gourraud PA, Vince N. The nature of genetic and environmental susceptibility to multiple sclerosis. PLoS One. 2021;16(3):e0246157.

- Lubetzki C, Stankoff B. Demyelination in multiple sclerosis. Handb Clin Neurol. 2014;122:89-99.

- Sospedra M, Martin R. Immunology of Multiple Sclerosis. Semin Neurol. 2016;36(02):115-27.

- Stromnes IM, Goverman JM. Active induction of experimental allergic encephalomyelitis. Nature Protocols. 2006;1(4):1810-9.

- Fazakerley JK, Webb HE. Semliki Forest Virus-induced, Immune-mediated Demyelination: Adoptive Transfer Studies and Viral Persistence in Nude Mice. Journal of General Virology. 1987;68(2):377-85.

- Oleszak Emilia L, Chang JR, Friedman H, Katsetos Christos D, Platsoucas Chris D. Theiler's Virus Infection: a Model for Multiple Sclerosis. Clinical Microbiology Reviews. 2004;17(1):174-207.

- Lanz TV, Brewer RC, Ho PP, Moon J-S, Jude KM, Fernandez D, et al. Clonally expanded B cells in multiple sclerosis bind EBV EBNA1 and GlialCAM. Nature. 2022;603(7900):321-7.

- Bjornevik K, Cortese M, Healy BC, Kuhle J, Mina MJ, Leng Y, et al. Longitudinal analysis reveals high prevalence of Epstein-Barr virus associated with multiple sclerosis. Science. 2022;375(6578):296-301.

- Allen IV, McQuaid S, Mirakhur M, Nevin G. Pathological abnormalities in the normal-appearing white matter in multiple sclerosis. Neurol Sci. 2001;22(2):141-4.

- Moll NM, Rietsch AM, Thomas S, Ransohoff AJ, Lee JC, Fox R, et al. Multiple sclerosis normal-appearing white matter: pathology-imaging correlations. Ann Neurol. 2011;70(5):764-73.

- West J, Aalto A, Tisell A, Leinhard OD, Landtblom A-M, Smedby Ö, Lundberg P. Normal Appearing and Diffusely Abnormal White Matter in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis Assessed with Quantitative MR. PLOS ONE. 2014;9(4):e95161.

- Elliott C, Momayyezsiahkal P, Arnold DL, Liu D, Ke J, Zhu L, et al. Abnormalities in normal-appearing white matter from which multiple sclerosis lesions arise. Brain Communications. 2021;3(3):fcab176.

- Sarkar SK, Willson AML, Jordan MA. The Plasticity of Immune Cell Response Complicates Dissecting the Underlying Pathology of Multiple Sclerosis. J Immunol Res. 2024;2024:5383099.

- Ruder J, Rex J, Obahor S, Docampo MJ, Müller AMS, Schanz U, et al. NK Cells and Innate-Like T Cells After Autologous Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation in Multiple Sclerosis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:794077.

- Pender MP. The essential role of Epstein-Barr virus in the pathogenesis of multiple sclerosis. Neuroscientist. 2011;17(4):351-67.

- Prinz M, Priller J. Microglia and brain macrophages in the molecular age: from origin to neuropsychiatric disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2014;15(5):300-12.

- Kuhlmann T, Miron V, Cui Q, Wegner C, Antel J, Brück W. Differentiation block of oligodendroglial progenitor cells as a cause for remyelination failure in chronic multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2008;131(Pt 7):1749-58.

- Filippi M, Bar-Or A, Piehl F, Preziosa P, Solari A, Vukusic S, Rocca MA. Multiple sclerosis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4(1):43.

- t Hart BA, Luchicchi A, Schenk GJ, Killestein J, Geurts JJG. Multiple sclerosis and drug discovery: A work of translation. EBioMedicine. 2021;68:103392.

- Rodriguez M, Scheithauer B. Ultrastructure of multiple sclerosis. Ultrastruct Pathol. 1994;18(1-2):3-13.

- Dietrich J, Blumberg BM, Roshal M, Baker JV, Hurley SD, Mayer-Pröschel M, Mock DJ. Infection with an endemic human herpesvirus disrupts critical glial precursor cell properties. J Neurosci. 2004;24(20):4875-83.

- Wongchitrat P, Chanmee T, Govitrapong P. Molecular Mechanisms Associated with Neurodegeneration of Neurotropic Viral Infection. Molecular Neurobiology. 2024;61(5):2881-903.

- Harberts E, Yao K, Wohler JE, Maric D, Ohayon J, Henkin R, Jacobson S. Human herpesvirus-6 entry into the central nervous system through the olfactory pathway. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2011;108(33):13734-9.

- Luchicchi A, Hart B, Frigerio I, van Dam AM, Perna L, Offerhaus HL, et al. Axon-Myelin Unit Blistering as Early Event in MS Normal Appearing White Matter. Ann Neurol. 2021;89(4):711-25.

- Yang L, Tan D, Piao H. Myelin Basic Protein Citrullination in Multiple Sclerosis: A Potential Therapeutic Target for the Pathology. Neurochem Res. 2016;41(8):1845-56.

- Martín Monreal MT, Hansen BE, Iversen PF, Enevold C, Ødum N, Sellebjerg F, et al. Citrullination of myelin basic protein induces a Th17-cell response in healthy individuals and enhances the presentation of MBP85-99 in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Autoimmun. 2023;139:103092.

- Faigle W, Cruciani C, Wolski W, Roschitzki B, Puthenparampil M, Tomas-Ojer P, et al. Brain Citrullination Patterns and T Cell Reactivity of Cerebrospinal Fluid-Derived CD4+ T Cells in Multiple Sclerosis. Frontiers in Immunology. 2019;Volume 10 - 2019.

- Tranquill LR, Cao L, Ling NC, Kalbacher H, Martin RM, Whitaker JN. Enhanced T cell responsiveness to citrulline-containing myelin basic protein in multiple sclerosis patients. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2000;6(4):220-5.

- Martin R, Whitaker JN, Rhame L, Goodin RR, McFarland HF. Citrulline-containing myelin basic protein is recognized by T-cell lines derived from multiple sclerosis patients and healthy individuals. Neurology. 1994;44(1):123-.

- Musse AA, Li Z, Ackerley CA, Bienzle D, Lei H, Poma R, et al. Peptidylarginine deiminase 2 (PAD2) overexpression in transgenic mice leads to myelin loss in the central nervous system. Disease Models & Mechanisms. 2008;1(4-5):229-40.

- Mastronardi FG, Wood DD, Mei J, Raijmakers R, Tseveleki V, Dosch HM, et al. Increased citrullination of histone H3 in multiple sclerosis brain and animal models of demyelination: a role for tumor necrosis factor-induced peptidylarginine deiminase 4 translocation. J Neurosci. 2006;26(44):11387-96.

- Yang QQ, Zhou JW. Neuroinflammation in the central nervous system: Symphony of glial cells. Glia. 2019;67(6):1017-35.

- Maroto M, Fernández-Morales JC, Padín JF, González JC, Hernández-Guijo JM, Montell E, et al. Chondroitin sulfate, a major component of the perineuronal net, elicits inward currents, cell depolarization, and calcium transients by acting on AMPA and kainate receptors of hippocampal neurons. J Neurochem. 2013;125(2):205-13.

- Tosun D, Schuff N, Rabinovici GD, Ayakta N, Miller BL, Jagust W, et al. Diagnostic utility of ASL-MRI and FDG-PET in the behavioral variant of FTD and AD. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2016;3(10):740-51.

- Carrillo-Vico A, Leech MD, Anderton SM. Contribution of Myelin Autoantigen Citrullination to T Cell Autoaggression in the Central Nervous System. The Journal of Immunology. 2010;184(6):2839-46.

- McRae BL, Kennedy MK, Tan LJ, Dal Canto MC, Picha KS, Miller SD. Induction of active and adoptive relapsing experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) using an encephalitogenic epitope of proteolipid protein. J Neuroimmunol. 1992;38(3):229-40.

- Miller SD, Karpus WJ. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in the mouse. Curr Protoc Immunol. 2007;Chapter 15:15.1.1-.1.8.

- Baker D, Nutma E, O'Shea H, Cooke A, Orian JM, Amor S. Autoimmune encephalomyelitis in NOD mice is not initially a progressive multiple sclerosis model. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2019;6(8):1362-72.

- Constantinescu CS, Farooqi N, O'Brien K, Gran B. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis (EAE) as a model for multiple sclerosis (MS). Br J Pharmacol. 2011;164(4):1079-106.

- Feizi N, Focaccetti C, Pacella I, Tucci G, Rossi A, Costanza M, et al. CD8+ T cells specific for cryptic apoptosis-associated epitopes exacerbate experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis. Cell Death & Disease. 2021;12(11):1026.

- Voskuhl RR, MacKenzie-Graham A. Chronic experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis is an excellent model to study neuroaxonal degeneration in multiple sclerosis. Frontiers in Molecular Neuroscience. 2022;Volume 15 - 2022.

- Lauren G, Richard R, Rhian E, Ryan JB, Mark IR, Djordje G, et al. Substantial subpial cortical demyelination in progressive multiple sclerosis: have we underestimated the extent of cortical pathology? Neuroimmunology and Neuroinflammation. 2020;7(1):51-67.

- Lazarević M, Stanisavljević S, Nikolovski N, Dimitrijević M, Miljković Đ. Complete Freund's adjuvant as a confounding factor in multiple sclerosis research. Front Immunol. 2024;15:1353865.

- Rodriguez M, Leibowitz JL, Lampert PW. Persistent infection of oligodendrocytes in Theiler's virus-induced encephalomyelitis. Ann Neurol. 1983;13(4):426-33.

- Oleszak EL, Chang JR, Friedman H, Katsetos CD, Platsoucas CD. Theiler's virus infection: a model for multiple sclerosis. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2004;17(1):174-207.

- Bettelli E, Baeten D, Jäger A, Sobel RA, Kuchroo VK. Myelin oligodendrocyte glycoprotein-specific T and B cells cooperate to induce a Devic-like disease in mice. J Clin Invest. 2006;116(9):2393-402.

- Olson JK, Croxford JL, Calenoff MA, Dal Canto MC, Miller SD. A virus-induced molecular mimicry model of multiple sclerosis. J Clin Invest. 2001;108(2):311-8.

- Gudi V, Gingele S, Skripuletz T, Stangel M. Glial response during cuprizone-induced de- and remyelination in the CNS: lessons learned. Front Cell Neurosci. 2014;8:73.

- Lipton HL, Dal Canto MC. Chronic neurologic disease in Theiler's virus infection of SJL/J mice. J Neurol Sci. 1976;30(1):201-7.

- Skapenko A, Leipe J, Lipsky PE, Schulze-Koops H. The role of the T cell in autoimmune inflammation. Arthritis Res Ther. 2005;7 Suppl 2(Suppl 2):S4-14.

- Libbey JE, Lane TE, Fujinami RS. Axonal pathology and demyelination in viral models of multiple sclerosis. Discov Med. 2014;18(97):79-89.

- Nagai M, Aoki M, Miyoshi I, Kato M, Pasinelli P, Kasai N, et al. Rats expressing human cytosolic copper-zinc superoxide dismutase transgenes with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis: associated mutations develop motor neuron disease. J Neurosci. 2001;21(23):9246-54.

- Rivailler P, Cho YG, Wang F. Complete genomic sequence of an Epstein-Barr virus-related herpesvirus naturally infecting a new world primate: a defining point in the evolution of oncogenic lymphocryptoviruses. J Virol. 2002;76(23):12055-68.

- Correia S, Bridges R, Wegner F, Venturini C, Palser A, Middeldorp JM, et al. Sequence Variation of Epstein-Barr Virus: Viral Types, Geography, Codon Usage, and Diseases. J Virol. 2018;92(22).

- t Hart BA, Jagessar SA, Haanstra K, Verschoor E, Laman JD, Kap YS. The Primate EAE Model Points at EBV-Infected B Cells as a Preferential Therapy Target in Multiple Sclerosis. Front Immunol. 2013;4:145.

- Mangiardi M, Crawford DK, Xia X, Du S, Simon-Freeman R, Voskuhl RR, Tiwari-Woodruff SK. An animal model of cortical and callosal pathology in multiple sclerosis. Brain Pathol. 2011;21(3):263-78.

- Packer D, Fresenko EE, Harrington EP. Remyelination in animal models of multiple sclerosis: finding the elusive grail of regeneration. Front Mol Neurosci. 2023;16:1207007.

- Wong SW, Bergquam EP, Swanson RM, Lee FW, Shiigi SM, Avery NA, et al. Induction of B cell hyperplasia in simian immunodeficiency virus-infected rhesus macaques with the simian homologue of Kaposi's sarcoma-associated herpesvirus. J Exp Med. 1999;190(6):827-40.

- Madsen MAJ, Wiggermann V, Bramow S, Christensen JR, Sellebjerg F, Siebner HR. Imaging cortical multiple sclerosis lesions with ultra-high field MRI. medRxiv. 2021:2021.06.25.21259363.

- Ptito M, Moesgaard SM, Gjedde A, Kupers R. Cross-modal plasticity revealed by electrotactile stimulation of the tongue in the congenitally blind. Brain. 2005;128(3):606-14.

- Ablashi D, Agut H, Alvarez-Lafuente R, Clark DA, Dewhurst S, DiLuca D, et al. Classification of HHV-6A and HHV-6B as distinct viruses. Arch Virol. 2014;159(5):863-70.

- Schreiner P, Harrer T, Scheibenbogen C, Lamer S, Schlosser A, Naviaux RK, Prusty BK. Human Herpesvirus-6 Reactivation, Mitochondrial Fragmentation, and the Coordination of Antiviral and Metabolic Phenotypes in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome. Immunohorizons. 2020;4(4):201-15.

- Leibovitch E, Wohler JE, Cummings Macri SM, Motanic K, Harberts E, Gaitán MI, et al. Novel marmoset (Callithrix jacchus) model of human Herpesvirus 6A and 6B infections: immunologic, virologic and radiologic characterization. PLoS Pathog. 2013;9(1):e1003138.

- Voumvourakis KI, Fragkou PC, Kitsos DK, Foska K, Chondrogianni M, Tsiodras S. Human herpesvirus 6 infection as a trigger of multiple sclerosis: an update of recent literature. BMC Neurol. 2022;22(1):57.

- Broccolo F, Fusetti L, Ceccherini-Nelli L. Possible role of human herpesvirus 6 as a trigger of autoimmune disease. ScientificWorldJournal. 2013;2013:867389.

- Pantry SN, Medveczky PG. Latency, Integration, and Reactivation of Human Herpesvirus-6. Viruses. 2017;9(7).

- Ljungman P. Is antiviral therapy against HHV-6B beneficial? Blood. 2020;135(17):1413-4.

- Challoner PB, Smith KT, Parker JD, MacLeod DL, Coulter SN, Rose TM, et al. Plaque-associated expression of human herpesvirus 6 in multiple sclerosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1995;92(16):7440-4.

- Sanders VJ, Felisan S, Waddell A, Tourtellotte WW. Detection of herpesviridae in postmortem multiple sclerosis brain tissue and controls by polymerase chain reaction. J Neurovirol. 1996;2(4):249-58.

- Hall CB, Long CE, Schnabel KC, Caserta MT, McIntyre KM, Costanzo MA, et al. Human herpesvirus-6 infection in children. A prospective study of complications and reactivation. N Engl J Med. 1994;331(7):432-8.

- Akhyani N, Berti R, Brennan MB, Soldan SS, Eaton JM, McFarland HF, Jacobson S. Tissue distribution and variant characterization of human herpesvirus (HHV)-6: increased prevalence of HHV-6A in patients with multiple sclerosis. J Infect Dis. 2000;182(5):1321-5.

- Abdel-Haq NM, Asmar BI. Human herpesvirus 6 (HHV6) infection. Indian J Pediatr. 2004;71(1):89-96.

- Lundström W, Gustafsson R. Human Herpesvirus 6A Is a Risk Factor for Multiple Sclerosis. Frontiers in Immunology. 2022;Volume 13 - 2022.

- Grut V, Biström M, Salzer J, Stridh P, Jons D, Gustafsson R, et al. Human herpesvirus 6A and axonal injury before the clinical onset of multiple sclerosis. Brain. 2024;147(1):177-85.

- Lyman MG, Enquist LW. Herpesvirus interactions with the host cytoskeleton. J Virol. 2009;83(5):2058-66.

- Romeo MA, Gilardini Montani MS, Gaeta A, D'Orazi G, Faggioni A, Cirone M. HHV-6A infection dysregulates autophagy/UPR interplay increasing beta amyloid production and tau phosphorylation in astrocytoma cells as well as in primary neurons, possible molecular mechanisms linking viral infection to Alzheimer's disease. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Basis Dis. 2020;1866(3):165647.

- Li L, Chi J, Zhou F, Guo D, Wang F, Liu G, et al. Human herpesvirus 6A induces apoptosis of HSB-2 cells via a mitochondrion-related caspase pathway. J Biomed Res. 2010;24(6):444-51.

- Gu B, Zhang G-F, Li L-Y, Zhou F, Feng D-J, Ding C-L, et al. Human herpesvirus 6A induces apoptosis of primary human fetal astrocytes via both caspase-dependent and -independent pathways. Virology Journal. 2011;8(1):530.

- Opsahl ML, Kennedy PG. Early and late HHV-6 gene transcripts in multiple sclerosis lesions and normal appearing white matter. Brain. 2005;128(Pt 3):516-27.

- Ahlqvist J, Fotheringham J, Akhyani N, Yao K, Fogdell-Hahn A, Jacobson S. Differential tropism of human herpesvirus 6 (HHV-6) variants and induction of latency by HHV-6A in oligodendrocytes. J Neurovirol. 2005;11(4):384-94.

- Laman JD, Weller RO. Drainage of cells and soluble antigen from the CNS to regional lymph nodes. J Neuroimmune Pharmacol. 2013;8(4):840-56.

- de Vos AF, van Meurs M, Brok HP, Boven LA, Hintzen RQ, van der Valk P, et al. Transfer of central nervous system autoantigens and presentation in secondary lymphoid organs. J Immunol. 2002;169(10):5415-23.

- Leibovitch EC, Jacobson S. Evidence linking HHV-6 with multiple sclerosis: an update. Curr Opin Virol. 2014;9:127-33.

- Álvarez-Lafuente R, Heras VD, Bartolomé M, García-Montojo M, Arroyo R. Human Herpesvirus 6 and Multiple Sclerosis: A One-Year Follow-up Study. Brain Pathology. 2006;16(1):20-7.

- Lassmann H. Multiple Sclerosis Pathology. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Med. 2018;8(3).

- Fotheringham J, Jacobson S. Human herpesvirus 6 and multiple sclerosis: potential mechanisms for virus-induced disease. Herpes. 2005;12(1):4-9.

- Weaver GC, Schneider CL, Becerra-Artiles A, Clayton KL, Hudson AW, Stern LJ. The HHV-6B U20 glycoprotein binds ULBP1, masking it from recognition by NKG2D and interfering with natural killer cell activation. Frontiers in Immunology. 2024;Volume 15 - 2024.

- Wang F-Z, Pellett PE. HHV-6A, 6B, and 7: immunobiology and host response. In: Arvin A, Campadelli-Fiume G, Mocarski E, Moore PS, Roizman B, Whitley R, Yamanishi K, editors. Human Herpesviruses: Biology, Therapy, and Immunoprophylaxis. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press; 2007. p. 850-74.

- Hanson DJ, Hill JA, Koelle DM. Advances in the Characterization of the T-Cell Response to Human Herpesvirus-6. Frontiers in Immunology. 2018;Volume 9 - 2018.

- Denes E, Magy L, Pradeau K, Alain S, Weinbreck P, Ranger-Rogez S. Successful treatment of human herpesvirus 6 encephalomyelitis in immunocompetent patient. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10(4):729-31.

- Eliassen E, Di Luca D, Rizzo R, Barao I. The Interplay between Natural Killer Cells and Human Herpesvirus-6. Viruses. 2017;9(12).

- Bortolotti D, Gentili V, Bortoluzzi A, Govoni M, Schiuma G, Beltrami S, et al. Herpesvirus Infections in KIR2DL2-Positive Multiple Sclerosis Patients: Mechanisms Triggering Autoimmunity. Microorganisms [Internet]. 2022; 10(3).

- Aarons GA, Goldman MS, Greenbaum PE, Coovert MD. Alcohol expectancies:: Integrating cognitive science and psychometric approaches. Addictive Behaviors. 2003;28(5):947-61.

- Jakhmola S, Upadhyay A, Jain K, Mishra A, Jha HC. Herpesviruses and the hidden links to Multiple Sclerosis neuropathology. Journal of Neuroimmunology. 2021;358:577636.

- Skuja S, Zieda A, Ravina K, Chapenko S, Roga S, Teteris O, et al. Structural and Ultrastructural Alterations in Human Olfactory Pathways and Possible Associations with Herpesvirus 6 Infection. PLOS ONE. 2017;12(1):e0170071.

- Das Sarma J. A mechanism of virus-induced demyelination. Interdiscip Perspect Infect Dis. 2010;2010:109239.

- Genain CP, Cannella B, Hauser SL, Raine CS. Identification of autoantibodies associated with myelin damage in multiple sclerosis. Nat Med. 1999;5(2):170-5.

- Komaroff AL, Bateman L. Will COVID-19 Lead to Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome? Front Med (Lausanne). 2020;7:606824.

- Novoa LJ, Nagra RM, Nakawatase T, Edwards-Lee T, Tourtellotte WW, Cornford ME. Fulminant demyelinating encephalomyelitis associated with productive HHV-6 infection in an immunocompetent adult. J Med Virol. 1997;52(3):301-8.

- Prineas JW, Connell F. Remyelination in multiple sclerosis. Ann Neurol. 1979;5(1):22-31.

- Salzer JL. Schwann cell myelination. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol. 2015;7(8):a020529.

- Stys PK. General mechanisms of axonal damage and its prevention. J Neurol Sci. 2005;233(1-2):3-13.

- Melloni A, Liu L, Kashinath V, Abdi R, Shah K. Meningeal lymphatics and their role in CNS disorder treatment: moving past misconceptions. Frontiers in Neuroscience. 2023;Volume 17 - 2023.

- Louveau A, Herz J, Alme MN, Salvador AF, Dong MQ, Viar KE, et al. CNS lymphatic drainage and neuroinflammation are regulated by meningeal lymphatic vasculature. Nat Neurosci. 2018;21(10):1380-91.

- van Zwam M, Huizinga R, Melief MJ, Wierenga-Wolf AF, van Meurs M, Voerman JS, et al. Brain antigens in functionally distinct antigen-presenting cell populations in cervical lymph nodes in MS and EAE. J Mol Med (Berl). 2009;87(3):273-86.

- Morandi E, Jagessar SA, t Hart BA, Gran B. EBV Infection Empowers Human B Cells for Autoimmunity: Role of Autophagy and Relevance to Multiple Sclerosis. J Immunol. 2017;199(2):435-48.

- Meier UC, Cipian RC, Karimi A, Ramasamy R, Middeldorp JM. Cumulative Roles for Epstein-Barr Virus, Human Endogenous Retroviruses, and Human Herpes Virus-6 in Driving an Inflammatory Cascade Underlying MS Pathogenesis. Front Immunol. 2021;12:757302.

- Da Mesquita S, Louveau A, Vaccari A, Smirnov I, Cornelison RC, Kingsmore KM, et al. Functional aspects of meningeal lymphatics in ageing and Alzheimer’s disease. Nature. 2018;560(7717):185-91.

- Rustenhoven J, Drieu A, Mamuladze T, de Lima KA, Dykstra T, Wall M, et al. Functional characterization of the dural sinuses as a neuroimmune interface. Cell. 2021;184(4):1000-16.e27.

- Ito Y, Ofengeim D, Najafov A, Das S, Saberi S, Li Y, et al. RIPK1 mediates axonal degeneration by promoting inflammation and necroptosis in ALS. Science. 2016;353(6299):603-8.

- Shao H, Wu W, Wang P, Han T, Zhuang C. Role of Necroptosis in Central Nervous System Diseases. ACS Chem Neurosci. 2022;13(23):3213-29.

- Ofengeim D, Yuan J. Regulation of RIP1 kinase signalling at the crossroads of inflammation and cell death. Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 2013;14(11):727-36.

- Engdahl E, Gustafsson R, Huang J, Biström M, Lima Bomfim I, Stridh P, et al. Increased Serological Response Against Human Herpesvirus 6A Is Associated With Risk for Multiple Sclerosis. Frontiers in Immunology. 2019;Volume 10 - 2019.

- Mahad DH, Trapp BD, Lassmann H. Pathological mechanisms in progressive multiple sclerosis. Lancet Neurol. 2015;14(2):183-93.

- Mastronardi FG, Noor A, Wood DD, Paton T, Moscarello MA. Peptidyl argininedeiminase 2 CpG island in multiple sclerosis white matter is hypomethylated. J Neurosci Res. 2007;85(9):2006-16.

- Campbell A, Hogestyn JM, Folts CJ, Lopez B, Pröschel C, Mock D, Mayer-Pröschel M. Expression of the Human Herpesvirus 6A Latency-Associated Transcript U94A Disrupts Human Oligodendrocyte Progenitor Migration. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):3978.

- Pender MP. Infection of autoreactive B lymphocytes with EBV, causing chronic autoimmune diseases. Trends Immunol. 2003;24(11):584-8.

- t Hart BA. Experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis in the common marmoset: a translationally relevant model for the cause and course of multiple sclerosis. Primate Biol. 2019;6(1):17-58.

- Bahramian E, Furr M, Wu JT, Ceballos RM. Differential Impacts of HHV-6A versus HHV-6B Infection in Differentiated Human Neural Stem Cells. Frontiers in Immunology. 2022;Volume 13 - 2022.

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).