1. Introduction

Leishmaniasis is a persistent, vector-borne zoonotic infection caused by protozoan parasites from the genus

Leishmania [

1]. The Leishmania flagellates are transmitted to vertebrates by the bite of infected female Phlebotomine sand flies. These flies are hosted by canids, rodents, marsupials, mongooses, bats, and hyraxes, which act as reservoirs for the parasite [

2]. Over 20 species of Leishmania are human pathogens, leading to a wide range of clinical manifestations of the disease. However, they are often divided into three clinically distinct forms: visceral leishmaniasis (VL), cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL) [

2,

3].

The World Health Organization (WHO) recognizes leishmaniasis as a neglected tropical disease (NTD). It is more prevalent among populations with limited socio-economic resources, where adverse conditions facilitate vector proliferation [

4,

5,

6].

According to the WHO Global Health Observatory [

7,

8]

, 98 countries and territories are endemic to leishmaniasis, with 350 million people at risk and 12 million cases of infection. The estimated annual incidence is 50,000 to 90,000 VL cases and 600,000 to 1 million CL cases. An estimated 700,000 to 1 million new cases occur annually [

1,

3,

8]

.

The latest data of the WHO Global Leishmaniasis Program for 2022 [

8] showed about 85% of global VL cases were reported from seven countries: Brazil, Ethiopia, India, Kenya, Somalia, South Sudan, and Sudan [

8]. At the same time, over 85% of global reported CL incidences are concentrated in eight countries: Afghanistan, Algeria, Brazil, Colombia, the Islamic Republic of Iran, Iraq, Peru, and the Syrian Arab Republic. In 2022, 337 cases of cutaneous leishmaniasis and 69 cases of visceral leishmaniasis were reported globally [

8]. In the New World, Brazil and Colombia have the highest incidence of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL), with Colombia recording 5,929 leishmaniasis cases in 2019, of which 5,839 were CL [

9].

The activity, survival, and population density of vectors and reservoirs can be influenced by variables such as temperature, humidity, rainfall, frost line, types of soil and other climatic conditions, as is the case with other vector-borne diseases, thereby determining which affect the availability of suitable mammalian hosts (reservoirs) and Lutzomyia species (vectors) at each Andean cutaneous leishmaniasis (Andean-CL) endemic area, defining the incidence of Leishmaniasis in a specific region [

10,

11,

12,

13,

14]. Moreover, numerous studies have explored the link between leishmaniasis and environmental factors such as height, latitude, temperature, humidity, precipitation, vegetation, land use, and the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO) phenomenon [

15,

16]. Diverse climatic impacts and nonlinear correlations among temperature, humidity, precipitation, disease prevalence, and seasonal variations have been identified in research conducted in Europe, Asia, Africa, and South America[

10,

11,

12,

13,

17,

18,

19].

Ecuador is a country in the Andean region of South America, bordered by Colombia and Peru, divided into four natural regions. The continental regions cover an area that stretches from the coast of the Pacific Ocean (Costa) to the Amazon Forest (Oriente) [

20]. They are characterized by tropical weather and high humidity, with altitudes below 1,000 m above sea level (m.a.s.l.), known as the lowlands. The highland region, which includes the Andes and their slopes, runs through the country from north to south, separating the coastal and Amazon regions, creating diverse landscapes with lower temperatures and tall mountains, reaching altitudes of up to 6,000 m.a.s.l. [

14,

20]. Typically, the Andean region is characterized by two well-defined seasons profoundly influenced by the ENSO phenomenon: a dry season from March/April to November/December with few clouds and higher evaporation rates and the round completely dry, and a rainy season from January to March with abundant rains and permanently cloudy skies [

14,

15,

20,

21].

Historically, most reported cases of leishmaniasis in Ecuador are associated with humid tropical and subtropical climates, particularly in rural areas. Data from the National Directorate of Epidemiological Surveillance (SE01-52) indicate that in 2020, 843 cases were reported: 816 were CL and 29 were MCL. The Province of Pichincha, situated in the Andean region, exhibited the highest incidence of leishmaniasis cases, followed by Morona Santiago in the Amazon, which reported the most cases of cutaneous and mucocutaneous leishmaniasis. Additional provinces with reported cases included Esmeraldas, Orellana, Manabí, and Napo, located in the Coast and Amazonia regions. There were no reports of VL [

22].

This data is noteworthy, as the climate conditions of the Andes are inconsistent with the typical environments in which leishmania vectors typically thrive. The province of Chimborazo, located in the Andes highlands beneath the Chimborazo volcano, has a median altitude of 3900 m.a.s.l. and has reported cases of Leishmaniasis [

22]. The province exhibits an equatorial high mountain climate across approximately 58.73% of its territory, characterized by an average temperature influenced by altitude, typically around 8°C. Maximum temperatures seldom exceed 20°C, while minimums may drop below 0°C. Consequently, reports of this pathology in the region were traditionally unexpected [

23].

Marengo et al. (2009) utilized the Providing Regional Climates for Impacts Studies (PRECIS) regional climate modeling system to analyze the distribution of temperature and precipitation extremes in a future climate scenario (2071–2100), based on the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change – Special Report on Emission Scenarios A2 and B2. Future scenarios indicate that all areas of the region will substantially alter rainfall and temperature. Warm nights are expected to become more frequent across tropical South America, whereas cold nights are anticipated to decline. Projected increases in the intensity of extreme precipitation events are observed across much of southern South America and western Amazonia [

24].

Additionally, the temperature for the province of Chimborazo aligns with global forecasts, indicating a general increase. By 2050, the average monthly minimum temperature in the province is projected to rise by approximately 1.61 to 1.66 °C, while the maximum monthly temperature is expected to increase by about 0.94 to 2.43 °C. The highest minimum temperatures occur in July, recorded at 2.01, 2.05, and 2.09 °C, while the lowest are observed in September, at 1.39 and 1.38 °C. This aligns with data produced for the province at the canton level [

25].

This study aims to assess the morbidity and mortality profile of Leishmaniasis in an Andean region of Ecuador, establish temporal trends, and identify the types of Leishmaniasis present in the area of interest. This study will determine the demographic characteristics of the population in Chimborazo and analyze the distribution, quantity, and types of injuries to provide an epidemiological perspective.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Ethics Statement

The study was conducted with authorization from the Faculty of Medicine Academic Unit at the Pontificia Universidad Católica del Ecuador and clearance from the Human Research Ethics Committee (code EO-212-2022, V1). This was done to ensure that the research adhered to bioethical standards. The investigation utilized data collected from hospitals and health centers, excluding patient-identifying information, eliminating the need for informed consent.

2.2. Study Design

A cross-sectional ecological and exploratory study was conducted using anonymized data from the District Directorate of Zone 3 of the Ecuadorian Public Ministry of Health (MSP), which operates under the Health Coordination of Chimborazo province. The data was collected from 2013 to 2022. This information enabled us to analyze the morbidity and mortality profiles of the reported leishmaniasis cases.

2.3. Overview of the Geographical Area Under Investigation

The study focused on individuals affected by leishmaniasis from 2013 to 2022 in specific areas of Chimborazo Province in south-central Ecuador. This province, known for its high peaks, such as Chimborazo volcano (6,310 meters), covers approximately 6,499.72 square kilometers and has a population of 509,352 [

22,

23,

24]. Chimborazo Province features a subtropical highland climate with distinct wet and dry seasons. The wettest months are from January to April when humidity often exceeds 80%. The region receives 5 to 7 hours of sunshine daily, and average temperatures range from 11°C to 13°C throughout the year. Rainfall peaks in March and decreases to about 34 mm in August.

Two specific areas of focus within the province were Alausí and Huigra. Alausí is a canton located in the southern part of Chimborazo Province that stands at 2,428 m.a.s.l., with temperatures ranging from 6°C to 16°C year-round, with an average annual rainfall of 406 mm. On the other side, Huigra, a parish of Alausí, is situated at an altitude of 1,219 m.a.s.l. Huigra has a subtropical climate, with average temperatures between 18°C and 19°C and an annual rainfall of 474 mm. The Chanchán River reaches altitudes of up to 4,480 m.a.s.l., where it exhibits a cold climate. The inter-Andean valleys in this region display temperatures ranging from 12°C to 22°C [

26].

Parasitological and serological diagnoses of leishmaniasis were conducted in laboratories approved by the Ministry of Health (MSP). These laboratories comply with the MSP's mandatory quality control standards, ensuring the results possess high specificity and sensitivity. As a result, the findings are recognized for their reliable positive predictive values [

26].

2.4. Sample and Setting

The present study focused on the data systematically recorded in the Health Care Records Platform of Ecuador (PRAS), from individuals who sought medical care at hospitals and health centers in the canton of Alausí and the parish of Huigra between 2013 and 2022. The analysis was limited to confirmed cases of patients diagnosed with leishmaniasis, irrespective of the underlying causes or clinical manifestations.

2.5. Data Analysis

The information was obtained from Zonal Health Coordination 3, based on records maintained in the PRAS. The investigation spanned ten years, from 2013 to 2022. Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software (version 25), where we applied the χ² and Cramer’s V tests to assess the categorical variables (p = 0.05). The Quantum Geographic Information System version 3.30.2 (QGIS) was utilized to visualize and analyze the distribution of reported Leishmania cases by integrating the disease data into the geographic information system.

3. Results

3.1. Annual Distribution of Leishmaniasis Cases

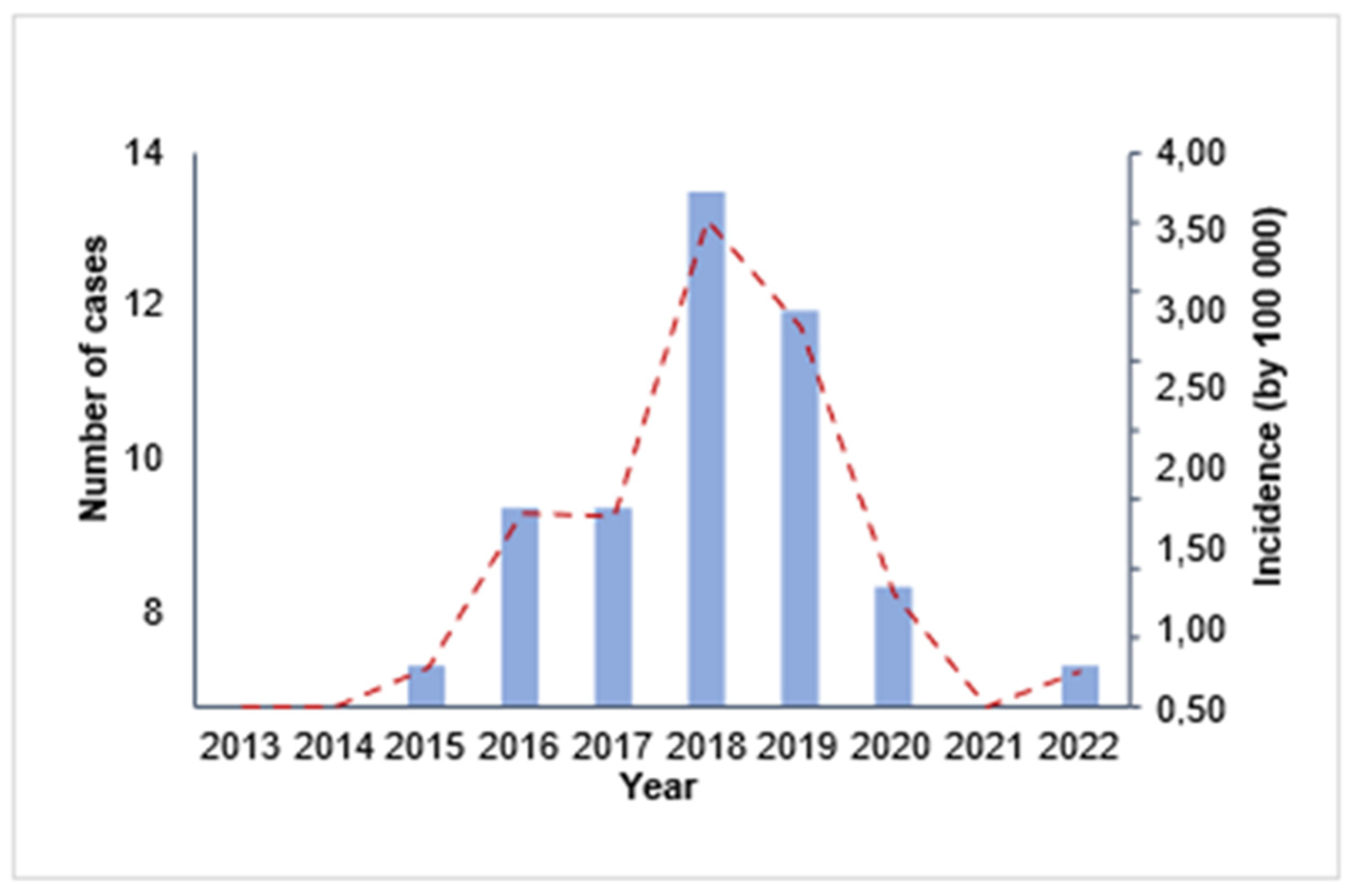

3.1.1. Trend of Leishmaniasis Incidence in Chimborazo from 2013 to 2022

From 2013 to 2022, the mean yearly incidence over this timeframe was 1.04 cases per 100,000 individuals. Interestingly, a slight increase in reported cases was observed in 2016, attaining a rate of 1.40 per 100,000 persons. As illustrated in

Figure 1, the reports escalated markedly, reaching a peak in 2018 at 3.51 occurrences per 100,000 population. After this peak, a consistent decrease was noted until 2022, when the incidence fell to 0.26 cases per 100,000 inhabitants. Significantly, no fatalities were attributed to this condition throughout the research.

Overall, the trend in leishmaniasis cases in Chimborazo exhibited a fluctuating pattern with a significant decline toward the end of the study period. The absence of fatalities highlights the importance of effective prevention and treatment measures in managing this disease.

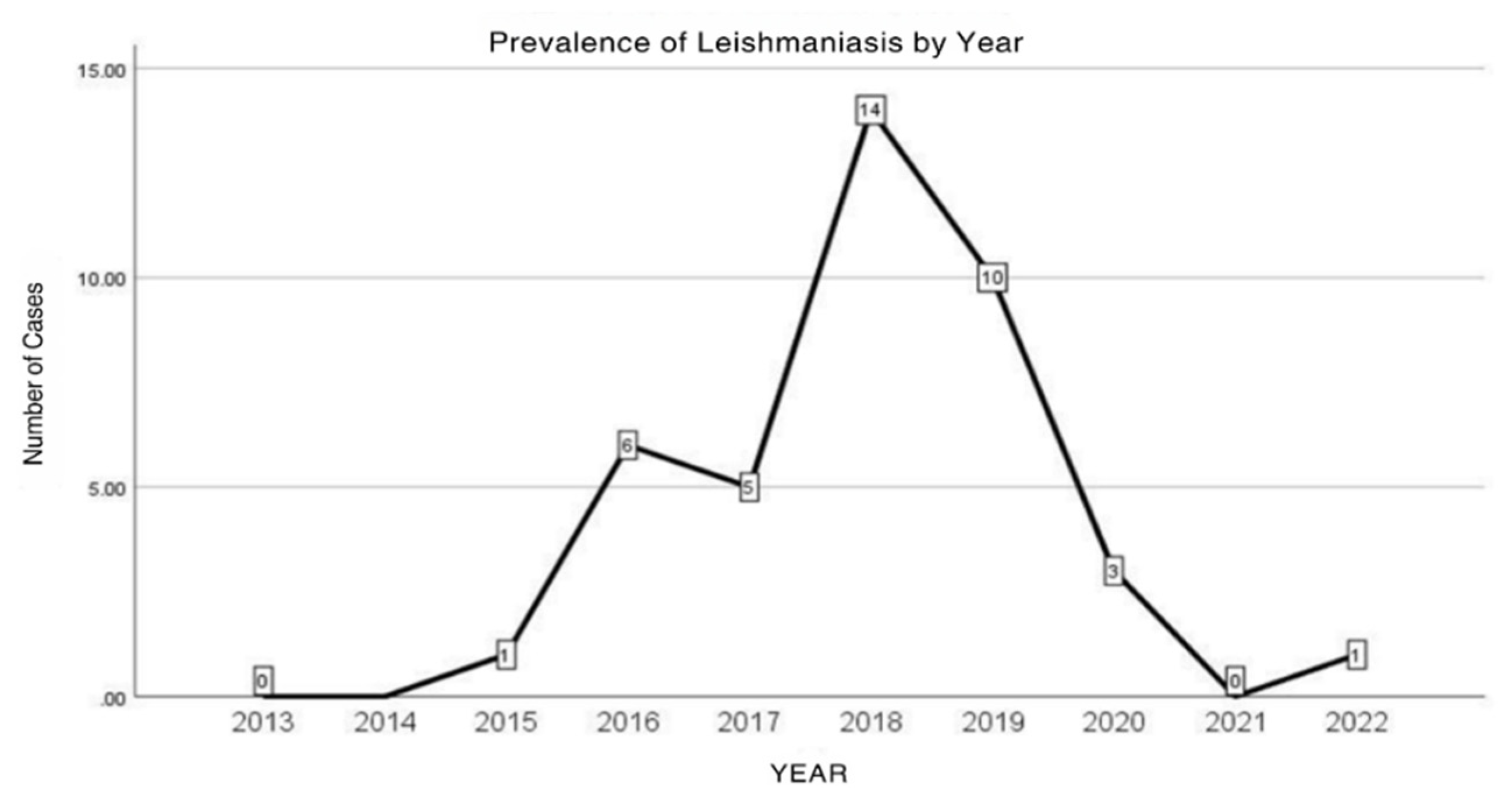

3.1.2. Annual Distribution of Leishmaniasis Cases in the Province of Chimborazo

We found 40 documented leishmaniasis cases throughout the study period in the Chimborazo province. Remarkably, there were no hospitalizations related to leishmaniasis during this timeframe. As illustrated in

Figure 2, the data reveal an interesting trend in reported leishmaniasis cases from 2013 to 2022. Between 2015 and 2017, we observed a modest increase in cases, totaling 12. However, the landscape changed dramatically between 2018 and 2019, when cases skyrocketed to 24, showcasing the urgent need for attention. Following this peak, a significant decline emerged from 2020 to 2022, with merely four cases documented. This decline presents an opportunity for continued intervention and monitoring to maintain and further improve public health in the region.

This fluctuation in the number of cases over the years suggests a potential pattern or trend that various factors may influence. Further analysis is needed to understand the reasons behind these fluctuations and develop prevention and control strategies.

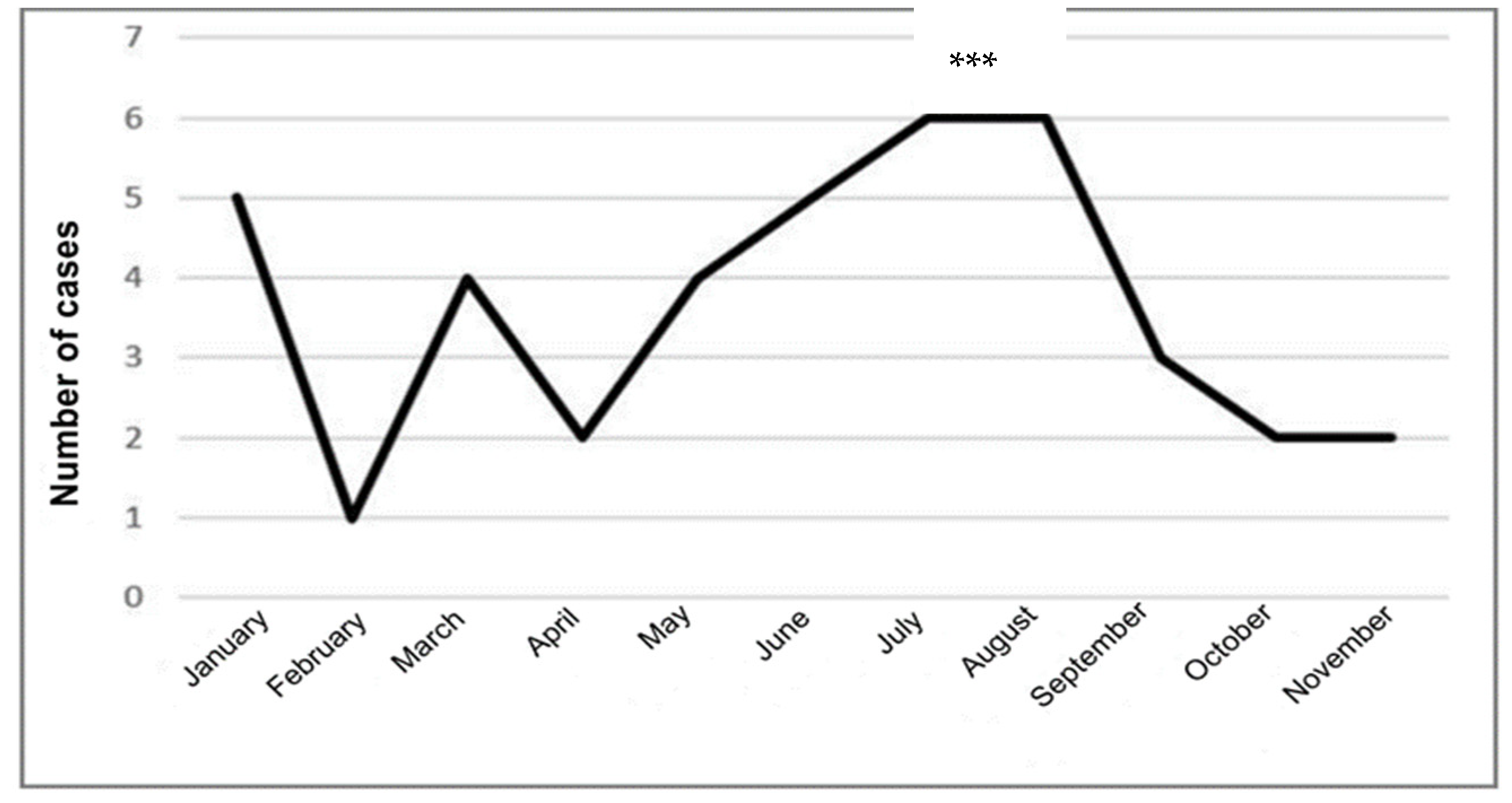

3.1.3. Monthly Distribution of Leishmaniasis Cases in the Province of Chimborazo

The monthly trend of Leishmaniasis cases revealed two peaks: a significant peak in July and August, with six cases each, and a smaller peak in January, with five cases. Leishmaniasis cases gradually increased from two in April to six in August, months characterized by the so-called summer, a less rainy season, followed by a notable decrease from September to November (3 to 2 cases), with no reports in December, the rainier and colder months of the year. This pattern may be linked to the typical life cycle of

Leishmania, in which the infection is more prevalent in the summer season due to the dynamics of the vector [

27]. Statistical analysis indicated significant differences in the monthly reports of leishmaniasis cases (p=0.001).

Figure 3 provides a visual representation of this data.

Overall, the trend in leishmaniasis cases in Chimborazo showed a fluctuating pattern, with a notable decrease towards the end of the study period. No fatalities were reported during this time.

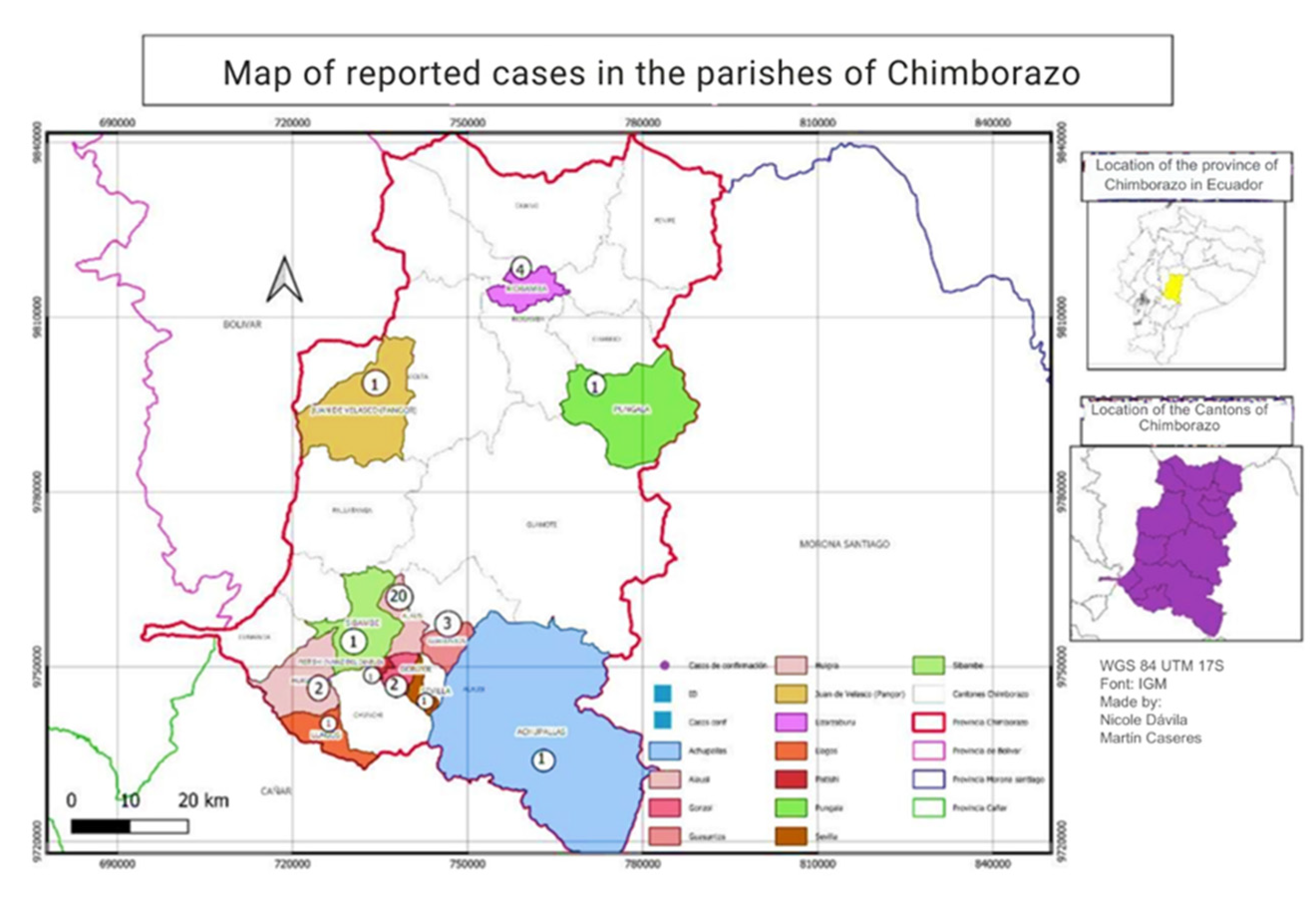

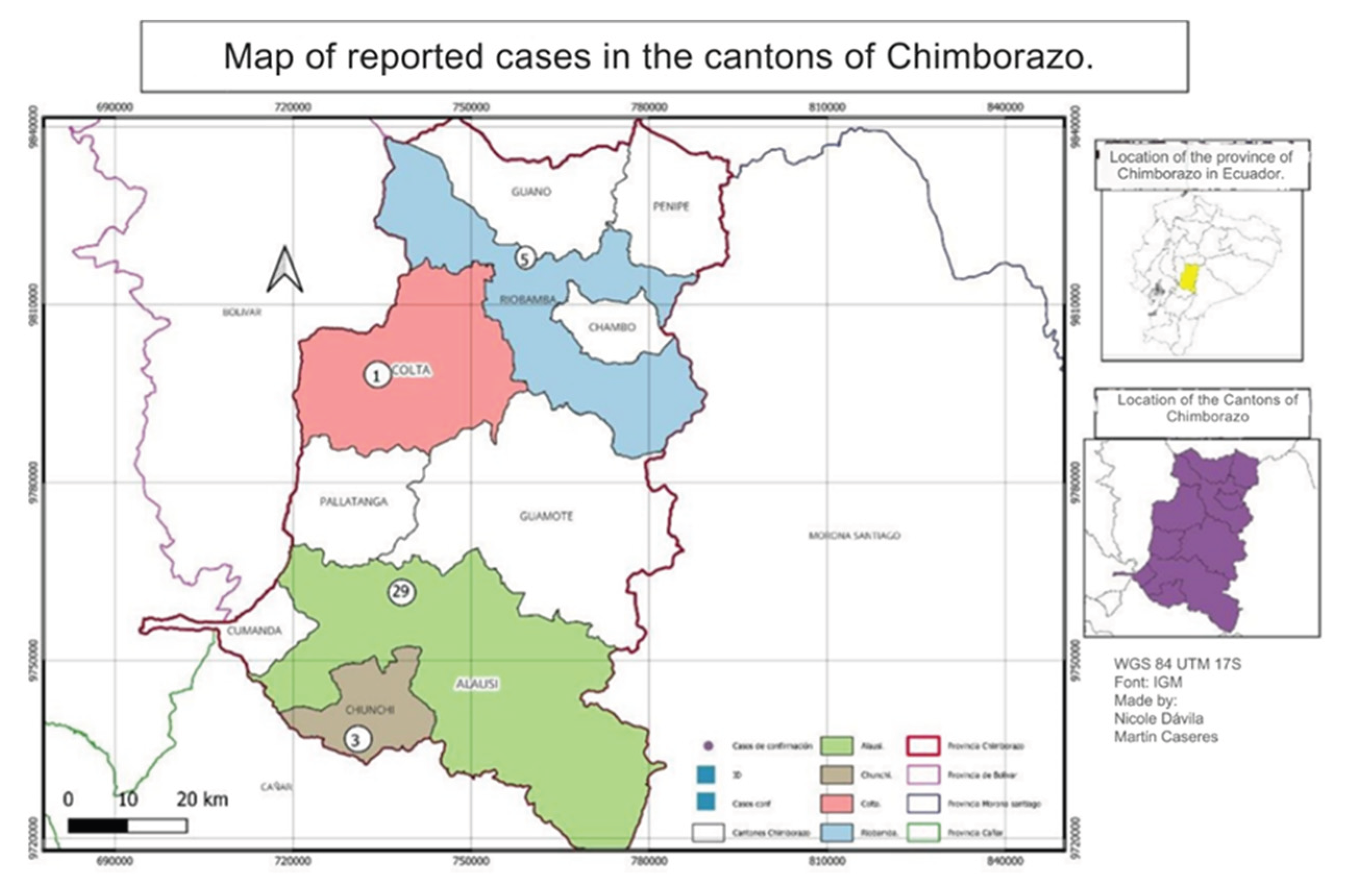

3.2. Spatial Distribution of Leishmaniasis Cases in the Province of Chimborazo

The distribution of Leishmaniasis cases in Chimborazo from 2015 to 2022 varied by canton. Most cases were concentrated in the southern part of the province, particularly in Alausí, with 29 cases reported. Riobamba followed this with five instances, Chunchi with 3 cases, and Colta with 1. The altitudinal range of these regions is between 2,340 and 3,212 meters above sea level, with Colta being the highest. No cases were reported in other cantons, as shown in

Figure 4.

A second spatial distribution analysis was conducted at the parish level in the canton of Alausí, where 29 leishmaniasis cases were reported. Our findings indicated that Alausí Central parish, located in the center of the canton, had the highest number of cases, with 20 instances, accounting for 69% of the total cases. The Guasuntos parish followed with three cases, representing approximately 10.34%. Additionally, the Lizarzaburu parish in the Riobamba canton reported four cases, constituting about 13.79% of the cases in that canton.

Overall, the spatial distribution analysis revealed that the majority of leishmaniasis cases in the canton of Alausí were concentrated in the Alausí Central parish, characterized by three types of climates: High Mountain Equatorial, Dry Mesothermal Equatorial, and Semi-Humid Mesothermal Equatorial [

27].

Figure 5.

Distribution of Leishmaniasis cases by parish, province of Chimborazo, during 2013-2022.

Figure 5.

Distribution of Leishmaniasis cases by parish, province of Chimborazo, during 2013-2022.

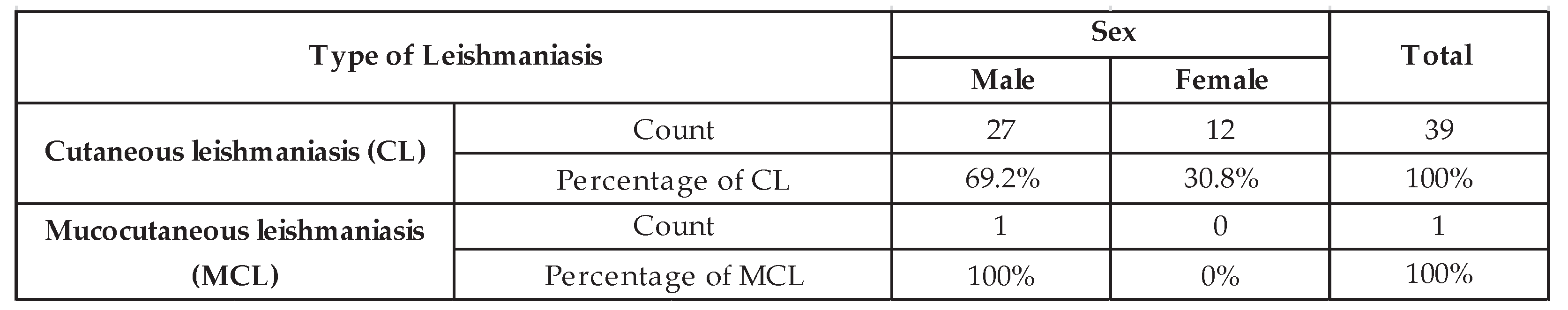

3.3. Type of Leishmaniasis

In line with previous studies on the types of leishmaniasis prevalent in Ecuador, an analysis of data from the Zonal Health Coordination 3 of Chimborazo shows that between the years 2003 and 2022, the reported cases in this province were primarily L. cutaneous (n = 39) and L. mucocutaneous (n = 1). The reported ratio of mucocutaneous leishmaniasis to cutaneous leishmaniasis (MCL: CL) in this province (1:39) is lower than the overall ratio found across the country, which is 1:13 [

28].

3.4. Demographic Characterization of Reported Cases of Leishmaniasis

3.4.1. Distribution of Leishmaniasis Cases by Sex

The analysis of the number of positive cases in the province of Chimborazo from 2013 to 2022 showed that leishmaniasis affects more men (n=28; 70%) than women (n=12; 30%). Depending on the type of leishmaniasis, a predominance of the male sex over the female sex was found for both LC and LMC forms. However, no statistically significant differences were found (p = 0.507).

Table 1 shows the distribution of LC and LMC cases by sex. The analysis of the distribution of leishmaniasis cases by sex showed that both sexes were affected by this pathology.

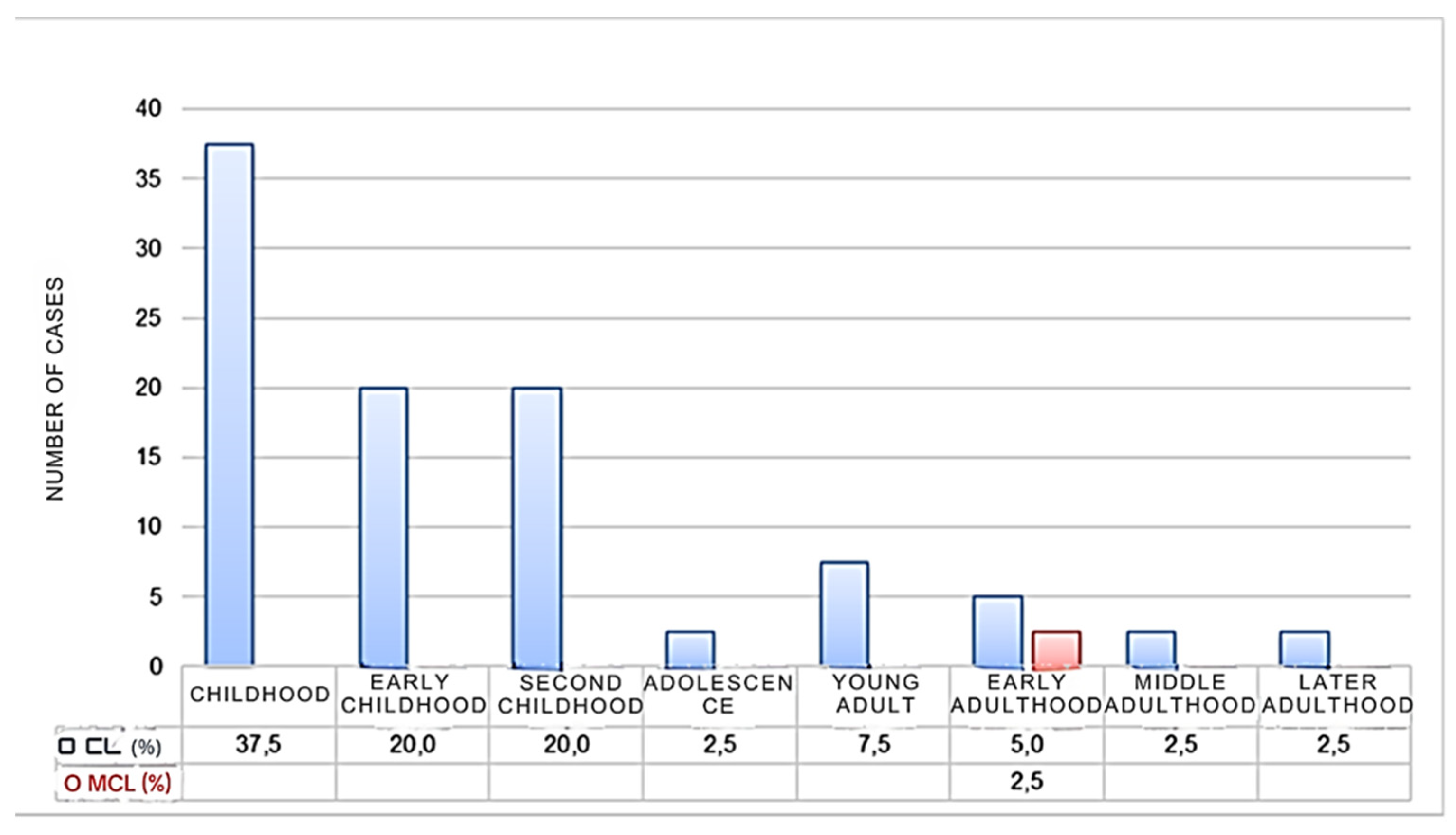

3.2.2. Distribution of Leishmaniasis Cases by Age

The population was categorized into different life cycle stages to understand which age groups are most affected by leishmaniasis. The findings indicate that leishmaniasis impacts all age groups. Childhood accounts for the highest percentage of cutaneous leishmaniasis (CL) cases (37.5%), with early and late childhood each accounting for 20% of cases. Chronic mucocutaneous leishmaniasis (CML) cases were reported only in early adulthood (2.5%). There were no statistically significant differences in the occurrence of leishmaniasis among the age groups based on life cycle stages (Cramer's V = 0.56, p = 0.081).

These results suggest that individuals of all ages are at risk for leishmaniasis, with children being particularly vulnerable to cutaneous forms of the disease. The results also highlight the importance of targeted prevention strategies for children in endemic regions. Figure 6 displays the distribution of leishmaniasis cases according to the life cycle stages at the time of evaluation.

Figure 4.

Percentage of Leishmaniasis in the province of Chimborazo according to the age of the infected individuals.

Figure 4.

Percentage of Leishmaniasis in the province of Chimborazo according to the age of the infected individuals.

3.3. Distribution and Number of Leishmaniasis Lesions

3.3.1. Number of Injuries

In the last ten years, 40 reported cases of Leishmaniasis were registered in the archives analyzed. However, only 19 of these reports provided information on the number of lesions in children and adults. Our analysis reveals that 85.71% (n = 17) of these reports indicated the presence of single lesions, while 14.29% (n = 2) reported multiple lesions.

3.3.2. Distribution of Injuries

The lesions from Leishmaniasis cases documented in the province of Chimborazo over the past decade were categorized into three regions: the face, upper extremities, and lower extremities. Our study found that 88.24% (n = 19) of the lesions were located on the face, while 11.76% (n = 2) were found on the upper extremities. These results align global research indicating that Leishmaniasis lesions are more frequently observed on the face than on the upper extremities.

3.3.3. Marital Status

In the analysis of the sociodemographic data, the marital status of participants was considered. The findings revealed that 87.80% of the population was single, while 12.20% were married. No statistically significant differences were observed (p = 0.702), as shown in

Table S2.

4. Discussion

This exploratory ecological study examined the morbidity and mortality profile of leishmaniasis in the Chimborazo province, an Andean region of Ecuador, during the period 2013–2022. Our findings revealed the unexpected presence of 40 confirmed leishmaniasis cases, predominantly cutaneous (97.5%) and mucocutaneous (2.5%), in an area traditionally characterized by a cold climate and high altitudes. No fatalities were recorded. These results not only highlight a shifting epidemiological landscape for leishmaniasis in Ecuador but also underscore the critical need to understand the profound implications of climate change on the distribution and incidence of this neglected tropical disease in traditionally non-endemic, high-altitude regions.

4.1. Leishmaniasis in Andean Regions: A Shifting Paradigm Under Climate Change

Historically, leishmaniasis in Ecuador has been predominantly associated with humid tropical and subtropical climates, particularly in the coastal and Amazonian lowlands [

8,

22]. The prevailing understanding has been that the environmental conditions in the Andean highlands, characterized by lower temperatures and higher altitudes, are generally unfavorable for the proliferation and survival of

Lutzomyia sandfly vectors [

5,

8]. However, the detection of 40 cases in Chimborazo, a province with an average altitude of 3900 m.a.s.l. and mean temperatures around 8°C, fundamentally challenges this long-held view.

Our findings are consistent with a growing body of evidence from South America that suggests an altitudinal expansion of leishmaniasis, likely driven by climate change [

1,

4]. While early studies on Andean cutaneous leishmaniasis (Andean-CL, locally known as "uta" in Peru and Ecuador) acknowledged its presence in specific inter-Andean valleys [

4,

5,

8], the occurrence of cases in a province like Chimborazo, with a significant proportion of its territory at high altitudes, points to a broader and more widespread phenomenon.

The projected increases in minimum and maximum temperatures for Chimborazo by 2050 [

24] are particularly pertinent. These warmer conditions could create more permissive environments for

Lutzomyia species, allowing them to adapt to higher altitudes and previously unsuitable thermal niches. This aligns with models that predict shifts in vector distributions due to climate change, although some models have also suggested potential declines in vector prevalence in certain areas [

2]. However, our empirical data from Chimborazo indicates an expansion of endemic areas, suggesting a net increase in risk in the Andean highlands.

The observed seasonality, with peaks in leishmaniasis cases during July and August (less rainy months) and lower incidence in December (rainier and colder months), suggests a linkage to the vector's life cycle and activity patterns, as commonly seen in other endemic regions [

27]. As climate change alters precipitation patterns and temperatures, these seasonal dynamics could become more pronounced or even shift, potentially extending the transmission season in high-altitude areas. This necessitates a re-evaluation of current surveillance and control strategies, which are often designed for historical endemic zones and their established seasonal cycles.

4.2. Implications of Geographical and Demographic Distribution in a Climate Change Context

The spatial clustering of cases in the southern part of Chimborazo province, particularly in Alausí and its parish Alausí Central, is a critical insight. The altitudinal range within these areas, from 1219 m.a.s.l. in Huigra to 2428 m.a.s.l. in Alausí, coupled with the varied microclimates (High Mountain Equatorial, Dry Mesothermal Equatorial, and Semi-Humid Mesothermal Equatorial), suggests that specific environmental factors or ecological niches within these regions may be particularly conducive to vector populations.

The presence of cases in Riobamba and Chunchi, at even higher altitudes (up to 3212 m.a.s.l.), provides further evidence of the upward shift in leishmaniasis distribution. This trend is alarming, as higher altitudes often have less public health infrastructure and access to healthcare, making populations in these newly affected areas particularly vulnerable. The adaptation of healthcare services to diagnose and treat leishmaniasis in high-altitude settings, where the disease was not previously expected, poses a significant challenge.

The predominance of cutaneous leishmaniasis cases (39 out of 40 cases) aligns with the overall epidemiological profile of leishmaniasis in Ecuador, where CL is by far the most common clinical form, while visceral leishmaniasis is rare [

3,

25]. Although the specific

Leishmania species responsible for these cases in Chimborazo were not identified in this study, previous molecular analyses in other Andean areas of Ecuador have identified

Leishmania braziliensis and

Leishmania panamensis as common causative agents of cutaneous leishmaniasis [

4,

7].

L. major has also been found in some regions [

1]. However, comprehensive mapping of

Leishmania species across different altitudinal gradients, particularly in areas like Chimborazo now reporting cases, remains crucial for understanding the specific parasite-vector dynamics at play and for informing control strategies [

29].

The demographic analysis, showing a higher proportion of cases in males (70%) and a significant clustering in children (37.5% overall, with 20% in early childhood and 20% in late childhood), suggests specific exposure patterns. The male predominance could be linked to outdoor occupational activities (e.g., agriculture, construction) that increase exposure to sandfly bites, a pattern observed in many endemic settings. The high incidence in children is particularly concerning, as they may have less developed immune responses, prolonged exposure during play or daily activities, and limited awareness of preventive measures. This finding underscores the urgent need for targeted public health interventions, including community education, vector control, and early diagnosis and treatment, specifically tailored for pediatric populations in these emerging endemic areas.

4.3. Clinical and Epidemiological Characterization

The type of leishmaniasis that predominates in the study areas is CL, followed by MCL, and without records of VL. According to the World Health Organization, CL is the most prevalent, with more than 12 million people infected worldwide, which means that it is greater than 75% compared to the other two types of leishmaniasis [

15].

The distribution of CL according to life cycle stages showed that no age stage is free from contracting the pathology, and a predominance is evident in the child population until second childhood; it is likely that this is due to the lack of immunity in this age group to leishmaniasis, especially at childhood level. It is also important to mention that

Lutzomyia has been described as an arthropod with a low flight range [

16]. Therefore, this could explain the higher prevalence group because children at that age are closer to the ground, in the first stages of self-movement.

The analysis of leishmaniasis case distribution by sex showed that both sexes were affected by this pathology, with a higher prevalence in male patients. According to some authors [

17], the sandfly has a predisposition for males due to the hormonal load that allows better parasite development [

18].

Lesions are classified as single and multiple. In this study, most cases in which the number of lesions was recorded presented single lesions (90%), while the rest of the population presented multiple lesions. The location of lesions varies depending on the life cycle stage of the Leishmania vector. In children, the vector predominantly attacks the face and neck, whereas in women, it affects the lower extremities, and in men, the upper extremities. A study in Ecuador found that most cases reported lesions on the face, which is consistent with the results of this research.

4.4. Comparison with Global and Regional Trends and Contemporary Studies

The incidence of leishmaniasis in Chimborazo province from 2013-2022 showed substantial fluctuation, with peaks observed in 2018-2019. This trend coincided with that of Sri Lanka, a South Asian country, where between 2001 and 2019, there were 19,361 clinically confirmed leishmaniasis reports. The incidence of cases was low from 2001-2008, then there was a slow but steady increase in the incidence of cases in 2009-2017, until a sudden outbreak occurred in 2018, with a total of 1,508 reports in 2017 to 3,271 in 2018, and then to 4,061 cases in 2019 [

10].

Our findings align with recent national data from Ecuador. Costa-España et al. (2024) conducted a cross-sectional national study analyzing inpatient data on dengue, malaria, and leishmaniasis from 2015-2022, providing a broader context for understanding leishmaniasis trends across Ecuador [

30]. When reviewing the Vector Gazette, published in 2019 by the National Directorate of Epidemiological Surveillance of the Ministry of Public Health of Ecuador, a concordance was found with the data obtained in this study; the data registry at the national level was 1,104 cases, of these 10 correspond to the province of Chimborazo; therefore, the data recorded in the Zonal Health Coordination No. 3 and the Epidemiological Gazette at the national level are corroborated [

22].

Climate change impacts on leishmaniasis distribution observed in our study are consistent with findings from other regions facing similar environmental pressures. In Iran, recent studies have demonstrated comparable patterns. Aflatoonian et al. (2024) conducted a longitudinal study in southeastern Iran from 1991 to 2021 documenting the elimination trend of rural cutaneous leishmaniasis, highlighting the significant role of climate change, population displacement, and agricultural transition in disease dynamics [

31]. Their findings showed that the total number of zoonotic cutaneous leishmaniasis (ZCL) cases decreased from 201 in 1991 to nil in 2021, while anthroponotic cutaneous leishmaniasis (ACL) cases decreased from 979 to 651, with temperature increases and decreased rainfall and humidity observed during this period.

Additionally, Ghatee et al. (2023) characterized geographic and climatic risk factors for cutaneous leishmaniasis in the hyperendemic focus of Bam County, southeastern Iran, showing parallels with our Andean findings regarding altitudinal and climatic influences [

32]. Their study found that annual temperature, maximum annual temperature, and minimum annual temperature were effective factors in CL occurrence, with an increase of one degree Celsius increasing the chance of CL by 279%, 347%, and 237%, respectively.

The ecological interactions between vectors, hosts, and parasites in high-altitude environments, as documented in our study, find support in recent Colombian research. Posada-López et al. (2023) examined ecological interactions of sandflies, hosts, and

Leishmania panamensis in an endemic area of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Colombia, providing valuable insights into similar eco-epidemiological dynamics in Andean environments [

33]. This research emphasizes the complexity of vector-host-parasite relationships in mountainous regions, which mirrors the challenges we identified in Chimborazo. Their study identified

Nyssomyia yuilli yuilli as the primary vector and

Psychodopygus ayrozai as a bridging species between wild and peridomiciliary cycles, demonstrating the intricate ecological relationships that influence transmission patterns in Andean regions.

The quality of life impacts and health-seeking behavior of patients in our study region can be contextualized by recent Ecuadorian research. Bezemer et al. (2023) conducted a cross-sectional study examining the quality of life of patients with suspected cutaneous leishmaniasis in the Pacific and Amazon regions of Ecuador, which provides important comparative data for understanding patient experiences across different ecological zones of the country [

23]. This study also investigated

Leishmania species distribution and clinical characteristics, offering insights that complement our demographic findings.

The monthly distribution of leishmaniasis cases determined two peaks of importance, the first in January and the other in July and August. This could be related to the typical aspect of leishmaniasis transmission, whose phase of infestation dates back to the summer period, or it would be associated with the seasonal dynamics of vector populations, or it could be due to the latent phase between infection and the onset of clinical symptoms to make the diagnosis. This seasonal pattern aligns with climate-driven transmission cycles described by Chaves and Pascual (2006), who documented the non-stationary nature of cutaneous leishmaniasis as a vector-borne disease influenced by climate cycles [

27].

In 2018, Zeleke and collaborators carried out a retrospective study of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Ethiopia over ten years (2009-2018), developing a monthly trend during the selected period, showing a significant oscillation in the prevalence rate, indicating that the highest rate corresponds to September (63.8%), followed by January (59.7%) and the month of May (56.9%), while the lowest value (49.3%) belongs to the month of June [

12]. These seasonal variations across different continents highlight the universal importance of climate factors in leishmaniasis transmission, while also demonstrating regional specificities that require localized understanding and intervention strategies.

5. Limitations and Future Research Directions: Building Resilience in the Face of Climate Change

This study's ecological and exploratory design, based on anonymized secondary data from healthcare records, presents certain limitations. The absence of information on the specific Leishmania and Lutzomyia species involved, the environmental determinants at a very local scale, and the precise exposure routes prevent establishing direct causal relationships between climate change and disease incidence in Chimborazo. Furthermore, reliance on passive surveillance data might lead to an underestimation of the true burden of leishmaniasis due to underreporting or misdiagnosis. The lack of fatalities observed is a positive finding, possibly reflecting effective clinical management, but it doesn't diminish the public health challenge posed by increased morbidity.

Moving forward, comprehensive field studies are essential to unravel the complex eco-epidemiology of leishmaniasis in the Andean highlands. Such studies should include:

Active case detection to obtain a more complete picture of incidence and prevalence, building on methodologies demonstrated in recent Iranian studies [

32].

Entomological surveys to identify sandfly vectors, their population densities, activity patterns, and dispersal at different altitudes [

6], incorporating lessons learned from Colombian ecological interaction studies [

33].

Molecular characterization of

Leishmania species from human cases, vectors, and reservoirs, which will help understand the specific transmission dynamics in these new foci [

7], following approaches used by Bezemer et al. (2023) in Pacific and Amazon regions of Ecuador [

23].

Ecological niche modeling that integrates detailed climatic data, land-use changes, and socioeconomic factors to predict future risk areas and assess population vulnerability [

1,

2], incorporating climate change projections as demonstrated in Palestinian studies [

13].

Quality of life assessments and health-seeking behavior studies specific to high-altitude populations, building on frameworks established for other Ecuadorian regions [

23].

Longitudinal studies are also needed to monitor the long-term trends of leishmaniasis incidence in relation to climate variability and change in these high-altitude regions, following the 30-year longitudinal approach successfully implemented in southeastern Iran [

31]. Understanding the interplay between temperature, precipitation, land-use changes, and human activities will be critical for developing effective, evidence-based surveillance and control strategies that are adaptive to the evolving epidemiological landscape under climate change.

Integrated surveillance systems should be developed that combine epidemiological data with climate monitoring, as suggested by recent national analyses of vector-borne diseases in Ecuador [

30]. This approach would enable real-time risk assessment and early warning systems for emerging leishmaniasis in previously unaffected high-altitude areas.

5. Conclusions

The findings of this study highlight the significant impact of climate change on the morbidity and mortality profile of leishmaniasis in the Andean region of Ecuador. The data indicates a clear correlation between rising temperatures and increased incidence rates of leishmaniasis. This trend is consistent with previous research suggesting that climate change can expand the habitat range of the sandfly vector, thereby increasing the risk of transmission to human populations.

One of the most striking observations is the seasonal variation in leishmaniasis cases, with peaks occurring during warmer months. This pattern underscores the importance of temperature as a critical factor in the lifecycle of the Leishmania parasite and its sandfly vector. The increased temperature enhances the breeding conditions for sandflies and accelerates the parasite's development within the vector, leading to higher transmission rates.

Our study also highlights the need for integrated disease surveillance and climate monitoring systems. Public health officials can better predict and respond to leishmaniasis outbreaks by combining epidemiological data with climate models. This proactive approach is essential for mitigating the impact of climate change on vector-borne diseases.

Furthermore, community-based interventions, such as education campaigns and vector control programs, are crucial in reducing the incidence of leishmaniasis. These interventions should be tailored to the specific cultural and environmental context of the Andean region to ensure their effectiveness.

The unexpected findings from Chimborazo serve as a crucial warning sign, emphasizing that previously "safe" areas are increasingly at risk from vector-borne diseases. Proactive planning and investment in surveillance and response capabilities in Andean regions are imperative to mitigate the impact of leishmaniasis on public health in a constantly changing climate. Adapting communities and healthcare systems to this new reality is an urgent and multifaceted challenge that requires intersectoral collaboration and a One Health perspective.

In conclusion, the interplay between climate change and leishmaniasis in the Andean region of Ecuador presents a complex public health challenge. Addressing this issue requires a multifaceted approach that includes improving healthcare access, enhancing disease surveillance, and implementing targeted vector control measures. Future research should focus on the long-term effects of climate change on leishmaniasis transmission dynamics and the development of sustainable strategies to protect vulnerable populations.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at the website of this paper posted on Preprints.org. Table S2—distribution of Leishmaniasis cases by marital status.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Delia M. Sosa-Guzman, and Enma V. Páez-Espinosa; methodology, Delia M. Sosa-Guzmán, and Luis R. Buitrón-Andrade; formal analysis, Enma V. Páez Espinosa and Delia M. Sosa-Guzmán.; Data recollection, Martín Cáceres-Ruiz, Nicole Dávila-Jumbo, and Vinicio Robalino; data curation, Enma V. Páez Espinosa; writing—original draft preparation, Martín Cáceres-Ruiz, Nicole Dávila-Jumbo; writing—review and editing, Enma V. Páez -Espinosa.; visualization, Enma V. Páez-Espinosa.; supervision, Eugènia Mato Matute; project administration, Delia M. Sosa-Guzmán.; funding acquisition, Enma V. Páez-Espinosa and Delia M. Sosa-Guzmán. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador.

Institutional Review Board Statement

The study was conducted following the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by the Ethics Committee of the Pontifical Catholic University of Ecuador on January 4, 2023, protocol code EO-212-2022.

Informed Consent Statement

Patient consent was waived because the data were obtained from anonymous sources in the archives of the Ministry of Public Health of Ecuador, with prior authorization from this institution.

Acknowledgments

We thank Zonal Health Coordination 3 for providing the necessary information for the investigation and the Chimborazo District Office for collaborating throughout the process.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the study's design, data collection, analysis, interpretation, manuscript writing, or decision to publish the results.

References

- Burza, S.; Croft, S.L.; Boelaert, M. Leishmaniasis. Lancet (London, England) 2018, 392, 951–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhoundi, M.; Downing, T.; Votýpka, J.; Kuhls, K.; Lukeš, J.; Cannet, A.; Ravel, C.; Marty, P.; Delaunay, P.; Kasbari, M. Leishmania infections: Molecular targets and diagnosis. Molecular aspects of medicine 2017, 57, 1–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- World-Health-Organization. Leishmaniasis Geneva, 202.

- Organization, W.H. Working to overcome the global impact of neglected tropical diseases: first WHO report on neglected tropical diseases; World Health Organization: 2010.

- Molyneux, D.H.; Asamoa-Bah, A.; Fenwick, A.; Savioli, L.; Hotez, P. The history of the neglected tropical disease movement. Transactions of The Royal Society of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene 2021, 115, 169–175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Showler, A.; Boggild, A. Protozoan Diseases: Leishmaniasis, Editor (i): Quah, SR International Encyclopedia of Public Health (2. izdanje). 2017.

- Ruiz-Postigo, J.A.; Jain, S.; Maia-Elkhoury, A.M.A.N.; Valadas, S.; Warusavithana, S.; Osman, M.; Lin, Z.; Beshah, A.; Yajima, A.; Gasimov, E. Global leishmaniasis surveillance: 2019-2020, a baseline for the 2030 roadmap/Surveillance mondiale de la leishmaniose: 2019-2020, une periode de reference pour la feuille de route a l'horizon 2030. Weekly Epidemiological Record 2021, 96, 401. [Google Scholar]

- World-Health-Organization. Global Health Observatory: Leishmaniasis; 2022.

- Muñoz Morales, D.; Suarez Daza, F.; Franco Betancur, O.; Martinez Guevara, D.; Liscano, Y. The Impact of Climatological Factors on the Incidence of Cutaneous Leishmaniasis (CL) in Colombian Municipalities from 2017 to 2019. Pathogens 2024, 13, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semenza, J.C.; Suk, J.E. Vector-borne diseases and climate change: a European perspective. FEMS microbiology letters 2018, 365, fnx244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Negev, M.; Paz, S.; Clermont, A.; Pri-Or, N.G.; Shalom, U.; Yeger, T.; Green, M.S. Impacts of climate change on vector borne diseases in the Mediterranean Basin—implications for preparedness and adaptation policy. International journal of environmental research and public health 2015, 12, 6745–6770. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pérez-Flórez, M.; Ocampo, C.B.; Valderrama-Ardila, C.; Alexander, N. Spatial modeling of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the Andean region of Colombia. Memórias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 2016, 111, 433–442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amro, A.; Moskalenko, O.; Hamarsheh, O.; Frohme, M. Spatiotemporal analysis of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Palestine and foresight study by projections modelling until 2060 based on climate change prediction. PloS one 2022, 17, e0268264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashiguchi, Y.; Cáceres, A.G.; Velez, L.N.; Villegas, N.V.; Hashiguchi, K.; Mimori, T.; Uezato, H.; Kato, H. Andean cutaneous leishmaniasis (Andean-CL, uta) in Peru and Ecuador: the vector Lutzomyia sand flies and reservoir mammals. Acta tropica 2018, 178, 264–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Altamiranda-Saavedra, M.; Gutiérrez, J.D.; Araque, A.; Valencia-Mazo, J.D.; Gutiérrez, R.; Martínez-Vega, R.A. Effect of El Niño Southern Oscillation cycle on the potential distribution of cutaneous leishmaniasis vector species in Colombia. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2020, 14, e0008324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ávila-Jiménez, J.; Gutiérrez, J.D.; Altamiranda-Saavedra, M. The effect of El Niño and La Niña episodes on the existing niche and potential distribution of vector and host species of American Cutaneous Leishmaniasis. Acta Tropica 2024, 249, 107060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oerther, S.; Jöst, H.; Heitmann, A.; Lühken, R.; Krüger, A.; Steinhausen, I.; Brinker, C.; Lorentz, S.; Marx, M.; Schmidt-Chanasit, J. Phlebotomine sand flies in Southwest Germany: an update with records in new locations. Parasites & vectors 2020, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Shirzadi, M.R.; Javanbakht, M.; Vatandoost, H.; Jesri, N.; Saghafipour, A.; Fouladi-Fard, R.; Omidi-Oskouei, A. Impact of environmental and climate factors on spatial distribution of cutaneous leishmaniasis in northeastern Iran: Utilizing remote sensing. Journal of Arthropod-Borne Diseases 2020, 14, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lewnard, J.A.; Jirmanus, L.; Júnior, N.N.; Machado, P.R.; Glesby, M.J.; Ko, A.I.; Carvalho, E.M.; Schriefer, A.; Weinberger, D.M. Forecasting temporal dynamics of cutaneous leishmaniasis in northeast Brazil. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2014, 8, e3283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashiguchi, Y.; Velez, L.N.; Villegas, N.V.; Mimori, T.; Gomez, E.A.; Kato, H. Leishmaniases in Ecuador: Comprehensive review and current status. Acta tropica 2017, 166, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dutari, L.C.; Loaiza, J.R. American cutaneous leishmaniasis in Panama: a historical review of entomological studies on anthropophilic Lutzomyia sand fly species. Parasites & vectors 2014, 7, 1–10. [Google Scholar]

- MSP, M.d.S.P.d.E.-. . Subsistema de Vigilancia SIVE- Alerta Enfermedades Transmitidas por Vectores Ecuador.. 2020, SE 01- 52 - 2020.

- Bezemer, J.M.; Freire-Paspuel, B.P.; Schallig, H.D.; De Vries, H.J.; Calvopiña, M. Leishmania species and clinical characteristics of Pacific and Amazon cutaneous leishmaniasis in Ecuador and determinants of health-seeking delay: a cross-sectional study. BMC infectious diseases 2023, 23, 395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marengo, J.A.; Jones, R.; Alves, L.M.; Valverde, M.C. Future change of temperature and precipitation extremes in South America as derived from the PRECIS regional climate modeling system. International Journal of Climatology: A Journal of the Royal Meteorological Society 2009, 29, 2241–2255. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- GADPCH. Índice Ombrotérmico para la provincia de Chimborazo en un escenario de cambio climático al año 2050.; Gobierno Autónomo Descentralizado de la Provincia de Chimborazo: Ecuador, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Ochoa-Cueva, P.; Fries, A.; Montesinos, P.; Rodríguez Díaz, J.; Boll, J. Spatial Estimation of Soil Erosion Risk by Land-cover Change in the Andes OF Southern Ecuador. Land Degradation & Development 2015, 26, 565–573. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chaves, L.F.; Pascual, M. Climate cycles and forecasts of cutaneous leishmaniasis, a nonstationary vector-borne disease. PLoS medicine 2006, 3, e295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Calvopina, M.; Armijos, R.X.; Hashiguchi, Y. Epidemiology of leishmaniasis in Ecuador: current status of knowledge-a review. Memorias do Instituto Oswaldo Cruz 2004, 99, 663–672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Escobar, L.E.; Romero-Alvarez, D.; Leon, R.; Lepe-Lopez, M.A.; Craft, M.E.; Borbor-Cordova, M.J.; Svenning, J.C. Declining Prevalence of Disease Vectors Under Climate Change. Scientific reports 2016, 6, 39150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Acosta-España, J.D.; Dueñas-Espín, I.; Narvaez, D.F.G.; Altamirano-Jara, J.B.; Gómez-Jaramillo, A.M.; Rodriguez-Morales, A.J. Analysis of inpatient data on dengue fever, malaria and leishmaniasis in Ecuador: A cross-sectional national study, 2015–2022. New Microbes and New Infections 2024, 60, 101421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bamorovat, M.; Sharifi, I.; Aflatoonian, M.R.; Salarkia, E.; Afshari, S.A.K.; Pourkhosravani, M.; Karamoozian, A.; Khosravi, A.; Aflatoonian, B.; Sharifi, F. A prospective longitudinal study on the elimination trend of rural cutaneous leishmaniasis in southeastern Iran: climate change, population displacement, and agricultural transition from 1991 to 2021. Science of the Total Environment 2024, 913, 169684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghatee, M.A.; Sharifi, I.; Mohammadi, N.; Moghaddam, B.E.; Kohansal, M.H. Geographical and climatic risk factors of cutaneous leishmaniasis in the hyper-endemic focus of Bam County in southeast Iran. Frontiers in Public Health 2023, 11, 1236552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Posada-López, L.; Velez-Mira, A.; Cantillo, O.; Castillo-Castañeda, A.; Ramírez, J.D.; Galati, E.A.; Galvis-Ovallos, F. Ecological interactions of sand flies, hosts, and Leishmania panamensis in an endemic area of cutaneous leishmaniasis in Colombia. PLoS neglected tropical diseases 2023, 17, e0011316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).