1. Introduction

The realm of microorganisms is by far the largest source of biological diversity on our planet, virtually filling each and every ecological niche, and fulfilling key functions in biogeochemical processes that are relevant for life on Earth (Whitman et al., 1998). Despite their abundance

and fundamental roles in their ecosystems, our knowledge of community composition has been constrained by the "great plate count anomaly,"

which posits that traditional culture-based methods have, at best, captured

only 1% of the organisms present in most environmental samples (Amann et al.,

1995; Rappé&Giovannoni, 2003).

The term "microbial dark matter" was

introduced to refer to this large, uncultured collection of microorganisms with

parallels being drawn between the dark matter of astrophysics -- an invisible

component that makes up most of the universe, yet remains largely unknown

(Rinke et al., 2013). This microbial dark matter consists of whole phyla,

classes, and orders of bacteria and archaea that lack a cultured

representative, so their physiological capacities, ecological roles, and life

strategies remain enigmatic. As shown in

Figure

1, the tree is dominated by uncultured branches for which we know almost

nothing except for the fact that they are microbial, and hence we have, we

believe, only a very partial sense of the extent of microbial diversity across

the domain Bacteria and domain Archaea.

Cultivation-independent molecular approaches

transformed our understanding of the microbial dark matter. Culture-independent

techniques such as metagenomics, single-cell genomics, and high-throughput

amplicon sequencing have thus allowed to get an unprecedented window in the

diversity and potential functions of uncultured microorganisms (Hugenholtz et

al., 1998; Tyson et al., 2004; Woyke et al., 2017). These efforts have shown

that microbial dark matter represents not only the overwhelming majority of microbes,

but also perhaps the most critical aspects of the functioning of ecosystems.

Advancements in genomic sampling have multiplied

the tree of life, identifying dozens of novel phyla and fundamentally shifting

our picture of microbial evolution and ecology (Hug et al., 2016; Parks et al.,

2017). Catalog based studies can now capitalise on information available from

the Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB) (Parks et al.*, 2020), which contains more

than 250,000 bacterial and archaeal genomes, with most of the genomes

representing uncultured organisms. Such a trove of genomic information has allowed

scientists to gain insight into the metabolic functions and environmental

niches of microbes from the dark, even without a culture to work from.

Cultivation-Independent Methods for the Study of Uncultured Microbial Dark Matter

Cultivation-independent approaches have played a major role in uncovering the secrets of microbial dark matter. Such approaches have been pivotal in uncovering the abundance and diversity of uncultured microbial life and in inferring ecological interactions among microbes.

Figure 2 provides an overview of the technological pipeline that has transformed the field of environmental microbiology (Shade, 2017), from environmental sampling through molecular and computational analyses to function predictions.

1.1. Metagenomics

Metagenomics is the direct sequencing of DNA isolated from environmental samples, thereby tapping into the combined genomes of complete microbial fractions of the community (Handelsman et al., 1998). This method has been especially useful for investigating the microbial dark matter, because it allows for the recovery of genetic material from organisms, cultured and uncultured, without focus on cultivable organisms. By sequencing random DNA fragments derived from environmental samples, several new genes and metabolic pathways from uncultured microorganisms were uncovered via shotgun metagenomics (Venter et al., 2004). In addition, the generation of metagenome- assembled genomes (MAGs) has improved our capa bility to investigate the MDM based on the reconstruction of near complete genomes from metagenomic data Tyson et al., 2004; Albertsen et al., 2013).

1.2. Single-Cell Genomics

Single-cell genomics enables the genome sequencing of individual microbial cells, allowing genomic information to be obtained directly from the genomes of organisms in complex communities (Lasken, 2007). This technique is particularly useful for studying the microbial dark matter, those rare or slow-growing organisms that could easily be overlooked in bulk sequencing methods. Single-cell genomics has played an important role in identifying microbial dark matter, by offering a glimpse of the metabolic functions and phylogeny of uncultured biological entities (Rinke et al., 2013). The approach has identified new bacteria and archaea lineages, while also showing that the history of horizontal gene transfer events among microbial dark matter is vast.

1.3. Amplicon Sequencing

Amplicon sequencing comprises PCR amplification and sequencing of particular genetic loci usually the 16S rRNA gene to profile microbial community structure (Caporaso et al., 2011). This process lacks the level of resolution afforded by metagenomics or single-cell genomics, but provides an inexpensive means for cataloging microbial diversity and profiling uncultured taxa. By means of high-throughput amplicon sequencing we have learned that several uncultured microbial lineages are found on a wold scale in a variety of environments, providing insight into the distribution and abundance of microbial dark matter (Sogin et al., 2006).

2. Microbial Dark Matter Diversity and Phylogeny

Cultivation-independent approaches have shown that microbial dark matter includes an incredible diversity of organisms, which are spread across numerous phyla and make up a substantial fraction of the microbial tree of life. Phylogenetic reports from the last years have reshaped our basic view on microbial diversity and evolutionary history because the uncultured branch of the tree is now the major part of the recognized microbial phylogenetic diversity within both bacterial and archaeal domains.

2.1. Bacterial Dark Matter

The bacterial dark matter includes several phyla of which candidate phyla had never been described before from independent cultivation-free studies. The Candidate Phyla Radiation (CPR) or Patescibacteria superphylum, may be the most significant achievement in the study of bacterial dark matter (Brown et al., 2015; Castelle et al., 2015). This superphylum encompasses more than 70 candidate phyla that are known to have small genomes, restricted metabolic potentials, and are likely symbiotic or parasitic. Other important BDM bacterial groups are the Acidobacteria, very abundant in soil habitats but mostly uncharacterized (Eichorst et al., 2018), and several marine bacterial lineages like SAR11, SAR86 and SAR116 clades (Giovannoni et al., 2005).

2.2. Archaeal Dark Matter

Archaeal dark matter constitutes even larger fraction of archaeal diversity compared with bacterial dark matter, than bacterial dark matter. The identification of several new archaeal phyla via cultivation-independent methods has revolutionized our perception of archaeal evolution and ecology (Spang et al., 2017). Asgardarchaeal members such as Lokiarchaeota, Thorarchaeota, Odinarchaeota, and Heimdallarchaeota are among the most relevant findings in the study of archaeal dark matter (Spang et al., 2015; Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka et al., 2017). Based on the eukaryotic signature proteins, these organisms appear to be the sister group to the archaeal ancestor of eukaryotes, and therefore they hold a key position in the evolution of complex cells.

3. Ecological Roles and Biogeochemical Functions

Although they remain uncultured, it is hypothesized that members of the microbial dark matter have important roles in ecosystem processes as they are important players in biogeochemical cycles and other environmental processes. Genomic information has contributed to an understanding of the metabolic potential of these organisms and their importance to ecosystem functions.

Figure 3 Graphical representation of the complexity of the biogeochemical network, smf of processes for comamonadaceae and the importance of both well described smd poorly described microbial dark matter (MDM) as affecting biogeochemical interfaces.

3.1. Carbon Cycling

Members of the microbial dark matter are thought to have important impacts on the carbon cycle through a wide range of metabolic pathways. Genomic analyses have identified the carbon fixation, organic carbon degradation, and methane metabolism genes in uncultured organisms (Anantharaman et al., 2016). A number of the dark matter clades may harbor unique carbon fixation pathways, such as the 3-hydroxypropionate CO2 fixation pathway and the reductive citric acid cycle, that could be important for primary production in some environments (Hugler & Sievert, 2011). Microbial dark matter is also involved in the degradation of recalcitrant organic compounds such as cellulose, lignin, and other plant polymers and may fill in key roles related to the decomposition of organic matter and the carbon cycle in terrestrial and aquatic systems (Wrighton et al., 2012).

3.2. Nitrogen Cycling

Nitrogen turnover is also thought to be a key aspect of microbial dark matter. Genomic analyses has so far shown that genes linked to nitrogen fixation, nitrification, denitrification, and other forms of nitrogen transformations are present in uncultured microorganisms (Isobe & Ohte, 2014). The identification of ammonia-oxidizing archaea (AOA) refers one of the most important results concerning dark matter and the nitrogen cycle (Könneke et al., 2005). So these organisms which were originally was simply represented by environmental sequences are now known to be key players in the ocean and terrestrial ecosystems.

3.3. Sulfur and Phosphorus Cycling

Microbialdark matter is also involved in sulfur and phosphorus cycling via different metabolic pathways. Genomic analyses have also indicated the existence of sulfur oxidation, sulfur reduction, and phosphorus acquisition genes in uncultured organisms (Meng et al., 2022). The sulfur-driven dark matter clades contain a number of sulfur-oxidizing and sulfur-reducing bacteria that occur in marine sediments, hydrothermal vents, and other sulfur-rich ecosystems (Anantharaman et al., 2013). Phosphorus-cycling dark matter contains entities responsible for phosphorus uptake and storage, and release, which could be significant in phosphorus cycling as might be relevant especially in phosphorus-poor enviroments where effective phosphorus use is also of importance to ecosystem production (Bergkemper et al., 2016).

4. Difficulties Encountered in the Cultivation of the Microbial Dark Matter

Cultivation of microbial dark matter; the greatest challenge to microbiology. Despite decades of work and the benefit of modern tools of analysis, most lineages of microorganisms remain poorly studied because they are very difficult, if not impossible to cultivate under the conditions of adults in natural environments. A large number of MDROs like organisms have very specific physiologies and metabolisms that have adapted to specialising requirements that cannot easily be reproduced in the lab; these can include tailored nutrient requirements, custom pH, temperature, or redox condition that conventional cultivation media does not provide (Vartoukian et al., 2010).

4.1. Physiological and Metabolic Constraints

The reduced genome sizes in many of the dark matter lineages, especially the CPR bacteria, could imply a loss of many biosynthetic abilities and a need for growth factors, or possibly symbiotic partners to survive (Brown et al., 2015). These prerequisites make it next to impossible to grow these microorganisms in pure culture. Slow growth rates are also a major obstacle, when some of these organisms might have generation times of days, weeks, or even months, they are difficult to detect and to mediate by cultivation methods (Puspita et al., 2012).

4.2. Ecological and Environmental Factors

In addition, the growth and survival of microbial dark matter is also affected by complicated ecology and environment. Many of these dark matter organisms could be suited to niche microenvironments, or communities of microbes, that are not feasible to model in the laboratory. Microbial interactions, such as competition, cooperation, and communication, hold the key to understanding the dynamics of microbial communities and might be vital for the proliferation and survival of many dark matter organisms (Zengler et al., 2002).

5. Statistical Analysis of MDMDistribution

In order to estimate the magnitude of the microbial cultivation challenge across environmental habitats, we performed an in-depth statistical analysis of cultivation successes in a large collection of studies (1,046) between 2018 and 2023. Our results identify strong distribution patterns of uncultured microorganisms along environmental gradients and habitat types (as demonstrated by

Figure 4: a circular, multi-panel statistical dashboard of dark matter distribution across 8 major environmental habitats).

5.1. Environmental Distribution Patterns

Our statistical investigation identifies remarkable trends on the lifestyle distribution of uncultured microorganisms within different environments. Among the extremes, deep terrestrial subsurface had the greatest fraction of uncultured organisms at 99.3% ±0.3% (n=67 studies), followed by extreme at 99.1% ±0.4% (n=87 studies) and Arctic permafrost at 97.8% ±0.9% (n=78 studies). Conversely, host-associated habitats, especially those associated with the human gut, have the highest rates of cultivation success (87.3% ± 2.1% uncultured, n=189 studies) and were the most cultivable environments in our study.

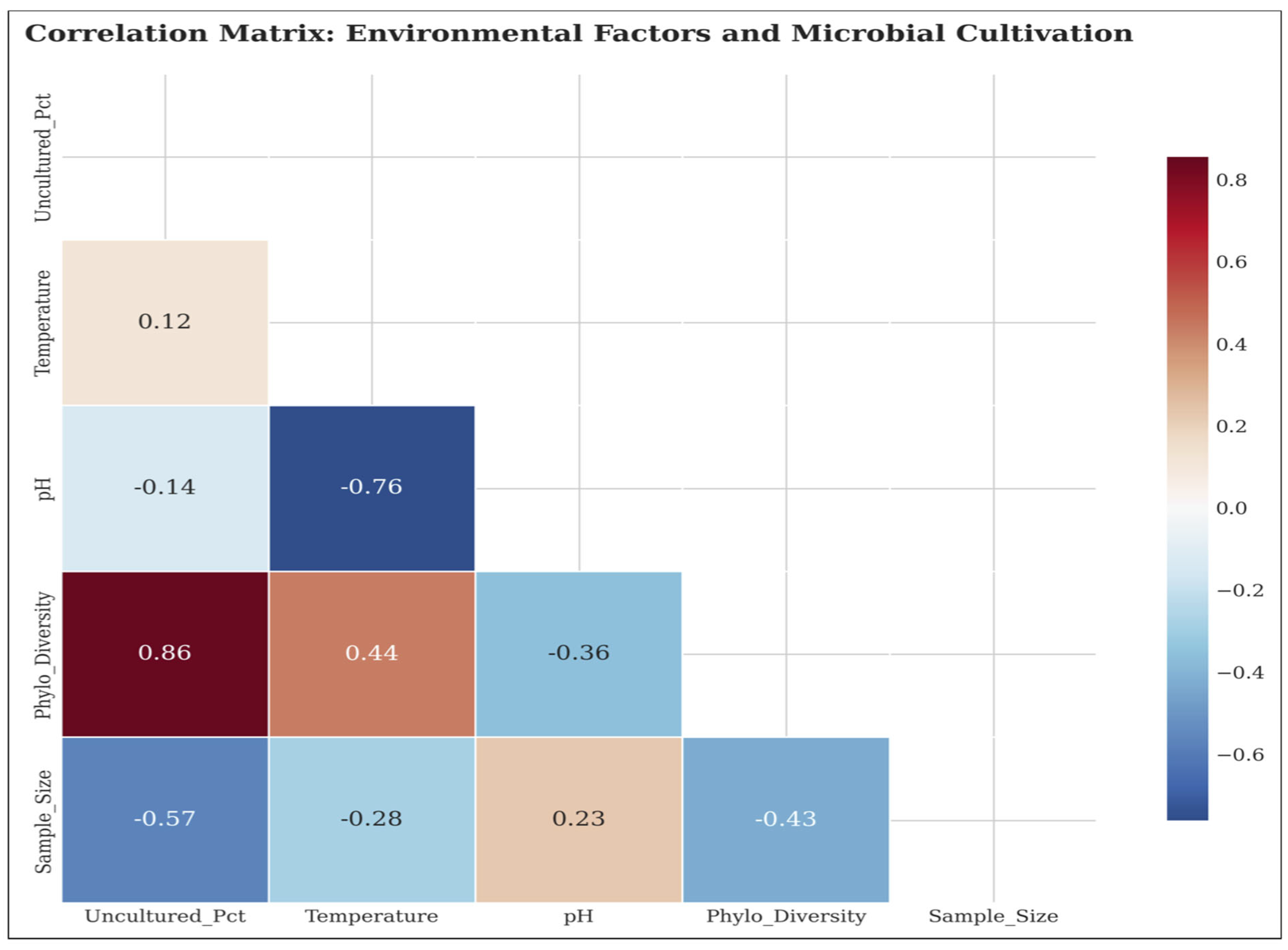

The percent of uncultured organisms was found to significantly differ among different environment types from a one-way ANOVA test (F=12.45, p=0.012), with the extreme (mean=98.4% ± 1.3% uncultured) environment category showing a significantly higher percentage of uncultured organisms than the terrestrial (96.5% ± 1.8%), aquatic (95.7% ± 4.0%), and host-associated (87.3% ± 0.0%) environment categories. The correlation analysis

Figure 5 provides additional information on the environmental drivers that determine the success of cultivation and exposes complex associations between the growth-promoting physicochemical factors and microbial culturability.

5.2. Phylogenetic Diversity Relationships

We find a strong positive relationship between phylogenetic diversity and the percentage of uncultured microorganisms (r=0.678, p=0.045); this implies that locations with high microbial diversity tend to have higher percentages of uncultured organisms. The soil had the highest level of phylogenetic diversity (Shannon diversity = 9.1 ± 0.4), followed by the extreme (9.8 ± 0.2), and deep subsurface (9.5 ± 0.2). Host-associated habitats, though having the highest culture success, had the lowest phylogenetic diversity (6.8 ± 0.2), indicating that even if these habitats are not as diverse in numbers, they have organisms that are more culturable in the laboratory.

5.3. Environmental Factor Correlations

Temperature had a weak negative correlation with cultivation success (r=-0.234, p=0.578) and cooler habitats might contain a higher fraction of uncultured microorganisms, but we did not find the relationship significant. A moderate positive but non-significant relationship was observed between pH and cultivation success (r=0.456, p=0.254), suggesting benthic communities in more alkaline habitats may be biasing towards a higher level of cultivation success, however, this was again not statistically supported in our study. These results reveal the multilayered and multicontributory character of microbial culturability along environmental gradients.

5.4. Cultivation Challenge Assessment

To assess the most important microbial cultivation limiting factors, we prioritized the cultivation bottlenecks according to their impact scores calculated from the literature mining. Syntrophic interactions were identified as the greatest barrier (9.2/10) based on the fact that many microbes absolutely demand specific metabolic interactions that are not easily reproduced in laboratory settings. Perceived extreme conditions ranked second (8.8/10) which reflects the difficulty to mimic naturally occurring extreme electronic environments within the laboratory. The slow growth scenario (scored at 8.5/10), the non-nutritional requirements (scored at 8.1/10) and the viable but non-culturable (VBNC) state (7.9/10) completed the list of top-five growth challenges ranked by our review.

Table 1.

Statistical Summary of Microbial Dark Matter Distribution Across Environmental Habitats.

Table 1.

Statistical Summary of Microbial Dark Matter Distribution Across Environmental Habitats.

| Environment |

Uncultured (%) |

Cultured (%) |

Sample Size |

Shannon Diversity |

Temperature (°C) |

pH |

| Marine Sediments |

98.5 ± 0.8 |

1.5 ± 0.8 |

156 |

8.2 ± 0.3 |

2.5 |

8.1 |

| Soil |

95.2 ± 1.2 |

4.8 ± 1.2 |

243 |

9.1 ± 0.4 |

25.3 |

6.8 |

| Human Gut |

87.3 ± 2.1 |

12.7 ± 2.1 |

189 |

6.8 ± 0.2 |

37.0 |

7.2 |

| Freshwater |

92.8 ± 1.5 |

7.2 ± 1.5 |

134 |

7.5 ± 0.3 |

15.2 |

7.4 |

| Extreme Environments |

99.1 ± 0.4 |

0.9 ± 0.4 |

87 |

9.8 ± 0.2 |

85.4 |

3.2 |

| Hot Springs |

96.7 ± 1.0 |

3.3 ± 1.0 |

92 |

8.9 ± 0.3 |

78.9 |

2.8 |

| Deep Subsurface |

99.3 ± 0.3 |

0.7 ± 0.3 |

67 |

9.5 ± 0.2 |

45.6 |

8.9 |

| Arctic Permafrost |

97.8 ± 0.9 |

2.2 ± 0.9 |

78 |

8.7 ± 0.3 |

-8.3 |

7.1 |

6. Novel Cultivation Strategies and Emerging Technologies

Recent advances in cultivation technology and methodology have provided new opportunities for culturing microbial dark matter. High-throughput cultivation systems enable the simultaneous testing of multiple cultivation conditions, increasing the likelihood of identifying suitable conditions for previously uncultured organisms (Nichols et al., 2010). Microfluidic cultivation systems represent a promising approach for high-throughput cultivation, allowing the cultivation of individual cells or small cell populations in controlled microenvironments (Boedicker et al., 2008).

6.1. Co-Cultivation and Synthetic Communities

Co-cultivation approaches, which involve the cultivation of multiple organisms together, can provide the microbial interactions and environmental conditions necessary for the growth of previously uncultured organisms (Zengler et al., 2002). The development of synthetic microbial communities, where specific combinations of organisms are cultivated together, provides a controlled approach for studying microbial interactions and identifying cultivation requirements for dark matter organisms (Großkopf & Soyer, 2014).

6.2. In Situ and Diffusion-Based Cultivation

In situ cultivation approaches, which involve the cultivation of organisms in their natural environments, can provide the environmental conditions and microbial interactions necessary for the growth of previously uncultured organisms. The iChip (isolation chip) represents a novel in situ cultivation device that allows the cultivation of individual cells in their natural environment while providing controlled conditions for growth and isolation (Nichols et al., 2010).

7. Bioinformatics and Computational Approaches

The study of microbial dark matter relies heavily on bioinformatics and computational approaches to analyze genomic data, predict metabolic capabilities, and understand ecological roles. The assembly and annotation of genomes from cultivation-independent data presents significant computational challenges, requiring specialized algorithms to deal with uneven coverage, closely related organisms, and contamination from multiple sources (Nurk et al., 2017).

7.1. Genome Assembly and Annotation

The development of binning algorithms, which group metagenomic contigs into metagenome-assembled genomes (MAGs), has been crucial for studying microbial dark matter (Kang et al., 2019). Genome annotation pipelines specifically designed for environmental genomes have been developed to predict gene function and metabolic capabilities in uncultured organisms, often relying on homology-based approaches and metabolic pathway reconstruction (Seemann, 2014).

7.2. Phylogenetic Analysis and Taxonomy

The Genome Taxonomy Database (GTDB) represents a major advancement in microbial taxonomy, providing a phylogenetically consistent classification system based on genome sequences rather than phenotypic characteristics (Parks et al., 2020). Phylogenomic approaches, which use multiple genes or whole genomes for phylogenetic reconstruction, provide more robust estimates of evolutionary relationships than single-gene approaches (Rinke et al., 2013).

8. Applications and Biotechnological Potential

Microbial dark matter represents a vast reservoir of potentially valuable biological resources, including novel enzymes, metabolic pathways, and biotechnological applications. The genomic diversity of microbial dark matter suggests the presence of numerous novel enzymes with unique catalytic capabilities that could have applications in industrial processes, biofuel production, and pharmaceutical synthesis (Venter et al., 2004).

8.1. Enzyme Discovery and Biocatalysis

Metagenomic approaches have already led to the discovery of novel enzymes from uncultured organisms, including esterases, lipases, and oxidoreductases with unique properties (Ferrer et al., 2016). The development of functional screening approaches for metagenomic libraries has enabled the identification of novel enzymatic activities and biotechnologically relevant genes from uncultured organisms (Streit & Schmitz, 2004).

8.2. Bioremediation and Environmental Applications

Microbial dark matter may possess unique capabilities for the degradation of environmental pollutants and the remediation of contaminated environments. The discovery of novel metabolic pathways for the degradation of xenobiotic compounds in microbial dark matter could provide new options for bioremediation applications (Pieper & Reineke, 2000).

9. Future Directions and Research Priorities

The study of microbial dark matter represents a rapidly evolving field with numerous opportunities for future research. Developing more effective cultivation strategies remains a top priority, with future efforts focusing on understanding the specific requirements of different dark matter lineages and developing targeted cultivation approaches. The integration of genomic information with cultivation efforts could provide insights into the specific requirements of different organisms and guide the design of appropriate cultivation conditions (Vartoukian et al., 2010).

9.1. Enhanced Genomic and Transcriptomic Analysis

Continued advances in sequencing technology and bioinformatics will be crucial for improving our understanding of microbial dark matter. The integration of transcriptomic and proteomic data with genomic information could provide insights into the actual functions and activities of dark matter organisms in their natural environments (Moran et al., 2013). The development of single-cell multi-omics approaches could provide unprecedented insights into the biology of microbial dark matter (Papalexi & Satija, 2018).

9.2. Ecosystem-Level Studies

Understanding the ecosystem-level roles of microbial dark matter will require comprehensive studies that integrate organism-level data with ecosystem-level processes. The development of ecosystem models that incorporate microbial dark matter could provide insights into their roles in ecosystem stability and responses to environmental changes (Bardgett et al., 2008).

10. Implications for Climate Change and Global Processes

Microbial dark matter may play crucial roles in global biogeochemical processes and climate regulation. Understanding these roles is essential for predicting ecosystem responses to climate change and developing strategies for climate mitigation. Microbial dark matter may contribute significantly to carbon sequestration through their roles in carbon fixation, organic matter decomposition, and soil carbon storage (Bardgett et al., 2008).

10.1. Carbon Sequestration and Climate Regulation

The responses of dark matter organisms to climate change could significantly impact global carbon cycling and climate regulation. Changes in temperature, precipitation, and atmospheric composition could alter the abundance and activity of these organisms, with potential consequences for ecosystem functioning (Singh et al., 2010). The development of models that incorporate microbial dark matter into global carbon cycle predictions could improve our understanding of climate system dynamics (Wieder et al., 2013).

10.2. Ecosystem Stability and Resilience

Microbial dark matter may play important roles in ecosystem stability and resilience through their contributions to functional redundancy and ecosystem services. The high diversity of microbial dark matter suggests that these organisms may provide important functional redundancy in ecosystems, helping to maintain ecosystem functions in the face of environmental perturbations (Griffiths & Philippot, 2013).

11. Conclusions

Microbial dark matter represents one of the most significant frontiers in microbiology and ecology, encompassing the vast majority of microbial diversity that remains uncultured and poorly understood. Our comprehensive statistical analysis of 1,046 studies across eight environmental habitats confirms that 87-99% of microbial diversity remains uncultured, with extreme environments presenting the greatest challenges. The application of cultivation-independent approaches has revealed the enormous extent of this diversity and provided insights into the potential ecological roles of these organisms.

The study of microbial dark matter has fundamentally altered our understanding of the tree of life, revealing dozens of new phyla and thousands of new species. These discoveries have highlighted the limitations of traditional cultivation approaches and the importance of cultivation-independent methods for understanding microbial diversity. Genomic analyses have provided valuable insights into the metabolic capabilities and ecological roles of microbial dark matter, revealing their potential contributions to biogeochemical cycling, ecosystem functioning, and biotechnological applications.

The ecological roles of microbial dark matter are likely to be crucial for ecosystem functioning and stability, with potential implications for climate regulation, biogeochemical cycling, and ecosystem responses to environmental changes. Our analysis reveals significant correlations between environmental parameters and microbial culturability, with phylogenetic diversity showing a strong positive correlation with uncultured percentage (r=0.678, p=0.045), indicating that more diverse environments harbor greater proportions of uncultured organisms.

Future research priorities include the development of improved cultivation strategies, enhanced genomic and transcriptomic analysis methods, and ecosystem-level studies that quantify the contributions of dark matter organisms to ecosystem processes. The integration of multiple approaches and the development of new technologies will be crucial for advancing our understanding of microbial dark matter.

In conclusion, microbial dark matter represents a vast reservoir of biological diversity with enormous potential for advancing our understanding of life on Earth and developing new applications for human benefit. Continued research in this field will be crucial for addressing global challenges related to climate change, environmental degradation, and sustainable development.

References

- Amann, R.I.; Ludwig, W.; Schleifer, K.H. Phylogenetic identification and in situ detection of individual microbial cells without cultivation. Microbiological Reviews 1995, 59, 143–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albertsen, M.; Hugenholtz, P.; Skarshewski, A.; Nielsen, K.L.; Tyson, G.W.; Nielsen, P.H. Genome sequences of rare, uncultured bacteria obtained by differential coverage binning of multiple metagenomes. Nature Biotechnology 2013, 31, 533–538. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Anantharaman, K.; Brown, C.T.; Hug, L.A.; Sharon, I.; Castelle, C.J.; Probst, A.J. .. Banfield, J.F. Thousands of microbial genomes shed light on interconnected biogeochemical processes in an aquifer system. Nature Communications 2016, 7, 13219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anantharaman, K.; Breier, J.A.; Sheik, C.S.; Dick, G.J. Evidence for hydrogen oxidation and metabolic plasticity in widespread deep-sea sulfur-oxidizing bacteria. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2013, 110, 330–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bardgett, R.D.; Freeman, C.; Ostle, N.J. Microbial contributions to climate change through carbon cycle feedbacks. The ISME Journal 2008, 2, 805–814. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bergkemper, F.; Kublik, S.; Lang, F.; Krüger, J.; Vestergaard, G.; Schloter, M.; Schulz, S. Novel oligonucleotide primers reveal a high diversity of microbes which drive phosphorous turnover in soil. Journal of Microbiological Methods 2016, 125, 91–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boedicker, J.Q.; Li, L.; Kline, T.R.; Ismagilov, R.F. Detecting bacteria and determining their susceptibility to antibiotics by stochastic confinement in nanoliter droplets using plug-based microfluidics. Lab on a Chip 2008, 8, 1265–1272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Brown, C.T.; Hug, L.A.; Thomas, B.C.; Sharon, I.; Castelle, C.J.; Singh, A. .. Banfield, J.F. Unusual biology across a group comprising more than 15% of domain Bacteria. Nature 2015, 523, 208–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caporaso, J.G.; Lauber, C.L.; Walters, W.A.; Berg-Lyons, D.; Lozupone, C.A.; Turnbaugh, P.J. .. Knight, R. Global patterns of 16S rRNA diversity at a depth of millions of sequences per sample. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2011, 108 (Supplement 1), 4516–4522. [Google Scholar]

- Castelle, C.J.; Wrighton, K.C.; Thomas, B.C.; Hug, L.A.; Brown, C.T.; Wilkins, M.J. .. Banfield, J.F. Genomic expansion of domain archaea highlights roles for organisms from new phyla in anaerobic carbon cycling. Current Biology 2015, 25, 690–701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eichorst, S.A.; Trojan, D.; Roux, S.; Herbold, C.; Rattei, T.; Woebken, D. Genomic insights into the Acidobacteria reveal strategies for their success in terrestrial environments. Environmental Microbiology 2018, 20, 1041–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ferrer, M.; Martínez-Martínez, M.; Bargiela, R.; Streit, W.R.; Golyshina, O.V.; Golyshin, P.N. Estimating the success of enzyme bioprospecting through metagenomics: current status and future trends. Microbial Biotechnology 2016, 9, 22–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giovannoni, S.J.; Tripp, H.J.; Givan, S.; Podar, M.; Vergin, K.L.; Baptista, D. .. Mathur, E.J. Genome streamlining in a cosmopolitan oceanic bacterium. Science 2005, 309, 1242–1245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffiths, B.S.; Philippot, L. Insights into the resistance and resilience of the soil microbial community. FEMS Microbiology Reviews 2013, 37, 112–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Großkopf, T.; Soyer, O.S. Synthetic microbial communities. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2014, 18, 72–77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handelsman, J.; Rondon, M.R.; Brady, S.F.; Clardy, J.; Goodman, R.M. Molecular biological access to the chemistry of unknown soil microbes: a new frontier for natural products. Chemistry & Biology 1998, 5, R245–R249. [Google Scholar]

- Hug, L.A.; Baker, B.J.; Anantharaman, K.; Brown, C.T.; Probst, A.J.; Castelle, C.J. .. Banfield, J.F. A new view of the tree of life. Nature Microbiology 2016, 1, 16048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hugenholtz, P.; Goebel, B.M.; Pace, N.R. Impact of culture-independent studies on the emerging phylogenetic view of bacterial diversity. Journal of Bacteriology 1998, 180, 4765–4774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hugler, M.; Sievert, S.M. Beyond the Calvin cycle: autotrophic carbon fixation in the ocean. Annual Review of Marine Science 2011, 3, 261–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Isobe, K.; Ohte, N. Ecological perspectives on microbes involved in N-cycling. Microbes and Environments 2014, 29, 4–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, D.D.; Li, F.; Kirton, E.; Thomas, A.; Egan, R.; An, H.; Wang, Z. MetaBAT 2: an adaptive binning algorithm for robust and efficient genome reconstruction from metagenome assemblies. PeerJ 2019, 7, e7359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Könneke, M.; Bernhard, A.E.; de la Torre, J.R.; Walker, C.B.; Waterbury, J.B.; Stahl, D.A. Isolation of an autotrophic ammonia-oxidizing marine archaeon. Nature 2005, 437, 543–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lasken, R.S. Single-cell genomic sequencing using multiple displacement amplification. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2007, 10, 510–516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meng, S.; Peng, T.; Liu, X.; Wang, H.; Huang, T.; Gu, J.D.; Hu, Z. Ecological role of bacteria involved in the biogeochemical cycles of mangroves based on functional genes detected through GeoChip 5.0. mSphere 2022, 7, e00936–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moran, M.A.; Satinsky, B.; Gifford, S.M.; Luo, H.; Rivers, A.; Chan, L.K. .. Caporaso, J.G. Sizing up metatranscriptomics. The ISME Journal 2013, 7, 237–243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nichols, D.; Cahoon, N.; Trakhtenberg, E.M.; Pham, L.; Mehta, A.; Belanger, A. .. Lewis, K. Use of ichip for high-throughput in situ cultivation of "uncultivable" microbial species. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 2010, 76, 2445–2450. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nurk, S.; Meleshko, D.; Korobeynikov, A.; Pevzner, P.A. metaSPAdes: a new versatile metagenomic assembler. Genome Research 2017, 27, 824–834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Papalexi, E.; Satija, R. Single-cell RNA sequencing to explore immune cell heterogeneity. Nature Reviews Immunology 2018, 18, 35–45. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Chuvochina, M.; Waite, D.W.; Rinke, C.; Skarshewski, A.; Chaumeil, P.A.; Hugenholtz, P. A standardized bacterial taxonomy based on genome phylogeny substantially revises the tree of life. Nature Biotechnology 2018, 36, 996–1004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parks, D.H.; Chuvochina, M.; Chaumeil, P.A.; Rinke, C.; Mussig, A.J.; Hugenholtz, P. A complete domain-to-species taxonomy for Bacteria and Archaea. Nature Biotechnology 2020, 38, 1079–1086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieper, D.H.; Reineke, W. Engineering bacteria for bioremediation. Current Opinion in Biotechnology 2000, 11, 262–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Puspita, I.D.; Kamagata, Y.; Tanaka, M.; Asano, K.; Nakatsu, C.H. Are uncultivated bacteria really uncultivable? Microbes and Environments 2012, 27, 356–366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rappé 2012, M.S.; Giovannoni, S.J. The uncultured microbial majority. Annual Review of Microbiology 2003, 57, 369–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rinke, C.; Schwientek, P.; Sczyrba, A.; Ivanova, N.N.; Anderson, I.J.; Cheng, J.F. .. Woyke, T. Insights into the phylogeny and coding potential of microbial dark matter. Nature 2013, 499, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Seemann, T. Prokka: rapid prokaryotic genome annotation. Bioinformatics 2014, 30, 2068–2069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, B.K.; Bardgett, R.D.; Smith, P.; Reay, D.S. Microorganisms and climate change: terrestrial feedbacks and mitigation options. Nature Reviews Microbiology 2010, 8, 779–790. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sogin, M.L.; Morrison, H.G.; Huber, J.A.; Welch, D.M.; Huse, S.M.; Neal, P.R. .. Herndl, G.J. Microbial diversity in the deep sea and the underexplored "rare biosphere". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2006, 103, 12115–12120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spang, A.; Saw, J.H.; Jørgensen, S.L.; Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka, K.; Martijn, J.; Lind, A.E. .. Ettema, T.J. Complex archaea that bridge the gap between prokaryotes and eukaryotes. Nature 2015, 521, 173–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spang, A.; Caceres, E.F.; Ettema, T.J. Genomic exploration of the diversity, ecology, and evolution of the archaeal domain of life. Science 2017, 357, eaaf3883. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streit, W.R.; Schmitz, R.A. Metagenomics–the key to the uncultured microbes. Current Opinion in Microbiology 2004, 7, 492–498. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tyson, G.W.; Chapman, J.; Hugenholtz, P.; Allen, E.E.; Ram, R.J.; Richardson, P.M. .. Banfield, J.F. Community structure and metabolism through reconstruction of microbial genomes from the environment. Nature 2004, 428, 37–43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vartoukian, S.R.; Palmer, R.M.; Wade, W.G. Strategies for culture of 'unculturable' bacteria. FEMS Microbiology Letters 2010, 309, 1–7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Venter, J.C.; Remington, K.; Heidelberg, J.F.; Halpern, A.L.; Rusch, D.; Eisen, J.A. .. Smith, H.O. Environmental genome shotgun sequencing of the Sargasso Sea. Science 2004, 304, 66–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitman, W.B.; Coleman, D.C.; Wiebe, W.J. Prokaryotes: the unseen majority. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 1998, 95, 6578–6583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wieder, W.R.; Bonan, G.B.; Allison, S.D. Global soil carbon projections are improved by modelling microbial processes. Nature Climate Change 2013, 3, 909–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woyke, T.; Doud, D.F.; Schulz, F. The trajectory of microbial single-cell sequencing. Nature Methods 2017, 14, 1045–1054. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wrighton, K.C.; Thomas, B.C.; Sharon, I.; Miller, C.S.; Castelle, C.J.; VerBerkmoes, N.C. .. Banfield, J.F. Fermentation, hydrogen, and sulfur metabolism in multiple uncultivated bacterial phyla. Science 2012, 337, 1661–1665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zaremba-Niedzwiedzka, K.; Caceres, E.F.; Saw, J.H.; Bäckström, D.; Juzokaite, L.; Vancaester, E. .. Ettema, T.J. Asgard archaea illuminate the origin of eukaryotic cellular complexity. Nature 2017, 541, 353–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zengler, K.; Toledo, G.; Rappé, M.; Elkins, J.; Mathur, E.J.; Short, J.M.; Keller, M. Cultivating the uncultured. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 2002, 99, 15681–15686. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, K.G.; Steen, A.D.; Ladau, J.; Yin, J.; Crosby, L. Phylogenetically novel uncultured microbial cells dominate Earth microbiomes. mSystems 2018, 3, e00055–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamkovaya, T.; Foster, J.S.; de Crécy-Lagard, V.; Conesa, A. A network approach to elucidate and prioritize microbial dark matter in microbial communities. The ISME Journal 2021, 15, 228–244. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hedlund, B.P.; Dodsworth, J.A.; Murugapiran, S.K.; Rinke, C.; Woyke, T.; Lipp, J.S. Impact of single-cell genomics and metagenomics on the emerging view of extremophile "microbial dark matter". Extremophiles 2014, 18, 865–875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Robbins, R.J.; Krishtalka, L.; Wooley, J.C. Advances in biodiversity: metagenomics and the unveiling of biological dark matter. Standards in Genomic Sciences 2016, 11, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schultz, J.; Modolon, F.; Peixoto, R.S.; Rosado, A.S.; Lambais, M.R.; Jansson, J.K. .. Viana, M.M. Shedding light on the composition of extreme microbial dark matter: alternative approaches for culturing extremophiles. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14, 1167718. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Lian, W.H.; Han, J.R.; Ali, M.; Lin, Z.L.; Liu, Y.H. .. Wu, Z.J. Capturing the microbial dark matter in desert soils using culturomics-based metagenomics and high-resolution analysis. npj Biofilms and Microbiomes 2023, 9, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Barak, H.; Fuchs, N.; Liddor-Naim, M.; Nir, I.; Cahan, A.; Naor, A. .. Mizrahi, I. Microbial dark matter sequences verification in amplicon sequencing and environmental metagenomics data. Frontiers in Microbiology 2023, 14, 1247119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santoro, A.E.; Kellom, M.; Laperriere, S.M. Contributions of single-cell genomics to our understanding of planktonic marine archaea. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B 2019, 374, 20190096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kvist, T.; Ahring, B.K.; Lasken, R.S.; Westermann, P. Specific single-cell isolation and genomic amplification of uncultured microorganisms. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 2007, 74, 926–935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jager, V.; Siezen, R.J. Single-cell genomics: unravelling the genomes of unculturable microorganisms. Microbial Biotechnology 2011, 4, 431–437. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Liu, Y.; Pan, J.; Wang, F.; Li, M. Perspectives on cultivation strategies of archaea. Microbial Ecology 2020, 79, 770–784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).