1. Introduction

Observation of light or radiation happens when there is an interaction with matter. These phenomena are described by electromagnetic or quantum theory. Electromagnetic theory operates with fields, but the measured physical values are often quadratic or bilinear combinations of the fields (like energy). Thus, the depiction is incomplete, and field characteristics are often determined indirectly. The two-layer organization and the disconnection of fundamental theoretical notions from observables complicates the understanding of classical electrodynamics [

1] and creates uncertainties in interpreting measured quantities in terms of the fields. Maxwell’s theory set a precedent for future theories based on dynamic fields, which feature similar two-layer organization and associated comprehension challenges.

Mathematical challenges also influenced progress in physics. Suitable mathematical tools were not always readily available. Maxwell utilized partial differential equations but considered quaternions a step forward. However, Heaviside’s reformulation of Maxwell's equations using the then-novel vector algebra became the standard approach. The complex vectors and 4-dimensional spaces attracted physicists’ attention with the advancement of relativity concepts at the beginning of the twentieth century. The rediscovery of more general Clifford algebra, or geometric algebra, by Hestenes [

2] in the 1960s underscored the limitations of vector algebra and emphasized the advantages of alternative methods. Geometric algebra is becoming more popular, with some scholars finding complex vectors a more natural representation of the electromagnetic field [

3,

4].

In Maxwell’s theory, a wave propagates in a vacuum in a direction perpendicular to both the electric and magnetic fields. In the absence of electric charges, only Faraday's law and Ampère's circuital law govern this process. These laws relate the spatial variation of one field to the temporal variation of the other, with no other interaction or unity between the two fields. Later, with the introduction of the concept of light's angular momentum [

5], and particularly after its experimental confirmation [

6], it would be appropriate to suggest a closer connection between the electric and magnetic fields. However, this development only reached a certain level of maturity recently [

3,

4,

7], aided by the use of multivectors. Advancements in electrodynamics can be further extended with computational statistical mechanics [

8]. The aim of this paper is to demonstrate how this can be achieved. But first, let’s revisit foundational concepts.

2. The Ambiguity of the Field Energy Density

Maxwell came to the understanding of field energy from separate electrostatic and magnetostatic considerations in the mid-1860s [

9]. He defined the energy density as a sum of squares of electric and magnetic field intensities

where

and

are the electric and magnetic fields. Natural unit system in which the speed of light, permittivity and permeability in vacuum are equal to unity

is used everywhere in this paper (unless otherwise stated). Given that both fields and energy are not directly measured in experiments simultaneously, this commonly accepted definition remains vague.

In 1884, Poynting put forward the continuity equation for the electromagnetic field (Poynting’s theorem) [

10]

where

is the total current density,

(with the dot) denotes divergence.

represents the energy flux density and defined as

The (3) is known as Poynting vector which was associated later with linear momentum [

11].

The continuity equation expresses conservation of energy and couples the energy density with energy flux density. The pair (1) and (3) is not a unique solution of the equation (2) [

9] and, both

and

, are defined through the fields that are not measured directly. A well-known portrayal of this situation provided in Feynman’s lectures (Chapter 27–4 in [

12]): “There are, in fact, an infinite number of different possibilities for

and

, and so far no one has thought of an experimental way to tell which one is right”. Additional experimental facts

could resolve this ambiguity. The interpretation of Poynting’s theorem is not straightforward and some aspects are controversial [

13].

After another quarter of a century, in 1909, Poynting formulated the idea of angular momentum for circularly polarized light [

5]. He did not associate it with his energy flux vector, but it was done soon after [

11] and the standard definition of the angular momentum is

where

is the position vector.

The torque exerted by circularly polarized light on a birefringent plate was measured in Beth’s experiment [

6] in the mid-1930s. This was the first successful demonstration of light’s angular momentum. Modern interpretation distinguishes between spin (SAM) and orbital (OAM) angular momentum [

14], although they are not entirely separable. Definition (4) is supported by modern experiments [

15].

When the vectors of electric and magnetic fields are not collinear, even for static fields, angular momentum is present and “This mystic circulating flow of energy, which at first seemed so ridiculous, is absolutely necessary” (Chapter 27–6 in [

12]). The existence of angular momentum was confirmed only 70 years after Maxwell introduced the concept of field energy density. However, this discovery did not prompt a revision of Maxwell's definition of energy density to account for “circulating flow of energy”.

Would it be natural to anticipate that angular momentum is accompanied by rotational energy? The question was rarely raised in the literature [

16]. Moreover, the dual interpretation of the Poynting vector — its association with both linear and angular momentum — can be seen as an indication that one of these interpretations may need to be reconsidered or even discounted.

The potential to incorporate rotational energy has been explored in two relatively recent publications that discuss photon structure from different perspectives. The first study [

7], by Muralidhar, employs complex vectors to examine the angular momentum of light. The second study [

8], authored by me, utilizes computational statistical mechanics to heuristically derive the blackbody radiation spectrum from possible structure of photons. Remarkably, both investigations came to similar structures. This paper is connecting the dots between [

7] and [

8].

3. Complex Vectors and Rotational Energy of Photons

The formalism of complex vectors was introduced by Gibbs in 1884 (he called them bivectors) [

17]. Weber utilized it to demonstrate how Maxwell's equations for fields in vacuum without charges can be consolidated into a single equation [

18]. A linear combination of the electric and magnetic field vectors was defined as

where

i is the unit imaginary. This vector is known as the Riemann–Silberstein or Weber vector. Gibbs introduced the complex vector conjugate and the products of the complex vector and its conjugate as well [

17] and, these notions were also relevant in the evolving electromagnetic theory. As noted in [

19], Silberstein had already identified in 1907 that key dynamical quantities of the field, such as Maxwell’s energy density and the Poynting vector, could be formed as bilinear expressions derived from the complex vector [

20]. Thus, the integration of electric and magnetic fields within the complex vector framework may aid in resolving certain ambiguities pertaining to continuity equation solutions, although the physical meaning of these expressions remains debatable. This form of complex vector has been utilized, for instance, to study electromagnetic field polarization [

21] and to explore the single photon wave function [

19].

The representation of the electromagnetic field can be constructed differently using geometric algebra [

2,

3]. The replacement of the unit imaginary with the pseudoscalar makes the complex vector “reference-frame-independent“ [

3]. Furthermore, “the intrinsic complex structure inherent to the geometry of spacetime has deep and perhaps underappreciated consequences for even our classical field theories“ [

3]. These inspirations are not unfounded, and adequate mathematical tools could stimulate better comprehension of physics.

Muralidhar employed such a form of field vector in three-dimensional space in [

4,

7]

where

is a pseudoscalar in geometric algebra of three dimensions. It commutes with all elements of the algebra and

. The bivector

is the magnetic field. From the products of the complex vector (5) and its conjugate

he comes to “the total energy density of photon”, (200) in [

4], as "a combination of kinetic energy and rotational energy”

This concept of rotational energy emerged from Belinfante’s and Ohanian’s assertion that photon spin can be viewed as angular momentum [

22,

23]. As articulated by Ohanian: “In an infinite plane wave, the

and

fields are everywhere perpendicular to the wave vector and the energy flow is everywhere parallel to the wave vector. However, in a wave of finite transverse extent, the

and

fields have a component parallel to the wave vector (the field lines are closed loops) and the energy flow has components perpendicular to the wave vector.”

Expressions like (6) have appeared in other publications on electromagnetic field complex vectors. However, the sum was not referred to as the total energy density. The scalar part was identified as the “energy density”, while the vector part was defined as the “momentum” or “energy-current” or “energy flow” density. Together, they were described as the “energy-momentum” density (see, for example, [

2,

3,

24,

25]). Variations in terminology suggest inconsistency in physical interpretations.

Muralidhar’s distinct explanation of (6) as a combination of translational flow of energy in the direction of propagation and the rotational energy flow in the plane normal to the direction of propagation (the bivector part) [

4,

7] offers significant insight. The expression (6) might be compared to Maxwell’s definition of the field energy density (1). Indeed, in Maxwell equations for the fields in vacuum without charges, the interplay between electric and magnetic fields is limited to a conversion from one to the other and back during translational motion, which comes with kinetic energy. Maxwell’s theory and the conventional vector representation of electric and magnetic fields do not account for any other interaction between these fields, and historically, the concept of the angular momentum of light was introduced much later. Conversely, the complex vector field (5) can generate internal rotations in addition to translational motion, leading to the suggestion that these rotations indicate the presence of an internal complex structure of the photon [

7]. The rotations explain the angular momentum from the core notions of the complex vector electromagnetic theory.

4. Simulation of Blackbody Radiation Spectrum

While Planck’s law never found an explanation within classical electrodynamics (and led to early quantum concepts and Bose–Einstein statistics), the blackbody radiation spectrum can be rationalized in terms of photons with a two-component structure [

8]. Each of the two components is characterized by a single number, its energy:

and

. The minimum energy of the components (zero-point energy) is assumed to be equal to unity and it is assumed that the probability to find the component with energy

obeys the Boltzmann distribution

, where

is the Boltzmann constant and

is temperature (temperature for simulations was selected to be significantly higher than the Einstein temperature to avoid the low temperature degradation of the distributions —

for components in [

8] and in this paper). It has been found [

8] that the sum of the components’ energies plus their geometric mean

produces the distribution that is close to Planckian. The comparison has been done for a fixed number of photons (

Figure 1 in [

8]) and excludes spatial factor in Planck’s law.

The representation (7) for the single photon energy is comparable to the energy density (6) obtained from electromagnetic field considerations. In general, the field energy density can be integrated over a volume to determine the total energy. For the energy of discretely simulated photons (7), it comes to summation or building distributions.

The magnitude of the wedge product in (6) is the same as the magnitude of Poynting vector

where

is the angle between the field vectors. It is defined in the range from 0 to

— rotational energy cannot be negative. Correspondingly, the field energy density magnitude is

A single plane electromagnetic wave that obeys Maxwell’s equations is

insufficient to describe all possible states of light polarization. Understanding of polarization can be achieved for the superposition of two perpendicular plane waves by varying their amplitudes and a phase shift. The advantages of complex vectors in depiction of polarization have been discussed in [

21]. In the context of photon structure, the magnitude of two field vectors and the angle between them generate all possible “internal” states of polarization (“external” photon orientation in space is not a concern of this study). The angle

corresponds to linear polarization with no rotational energy. The ability to characterize polarization states by complex vectors — like it could be done with the Stokes parameters — can be seen as their

adequacy for the role of building blocks of electromagnetic theory.

The simulation presented below is similar to the one described in [

8], and the details provided there are also relevant here. The heuristic formula (7) has been replaced with one based on (8)

In this context,

and

are associated with electric and magnetic translational energy of a photon. For the unpolarized light of blackbody radiation, it can be assumed that all the angles between the field vectors are equally probable. The geometric mean in (9), on average, will have a higher weight in comparison to (7), though it is not a big change overall

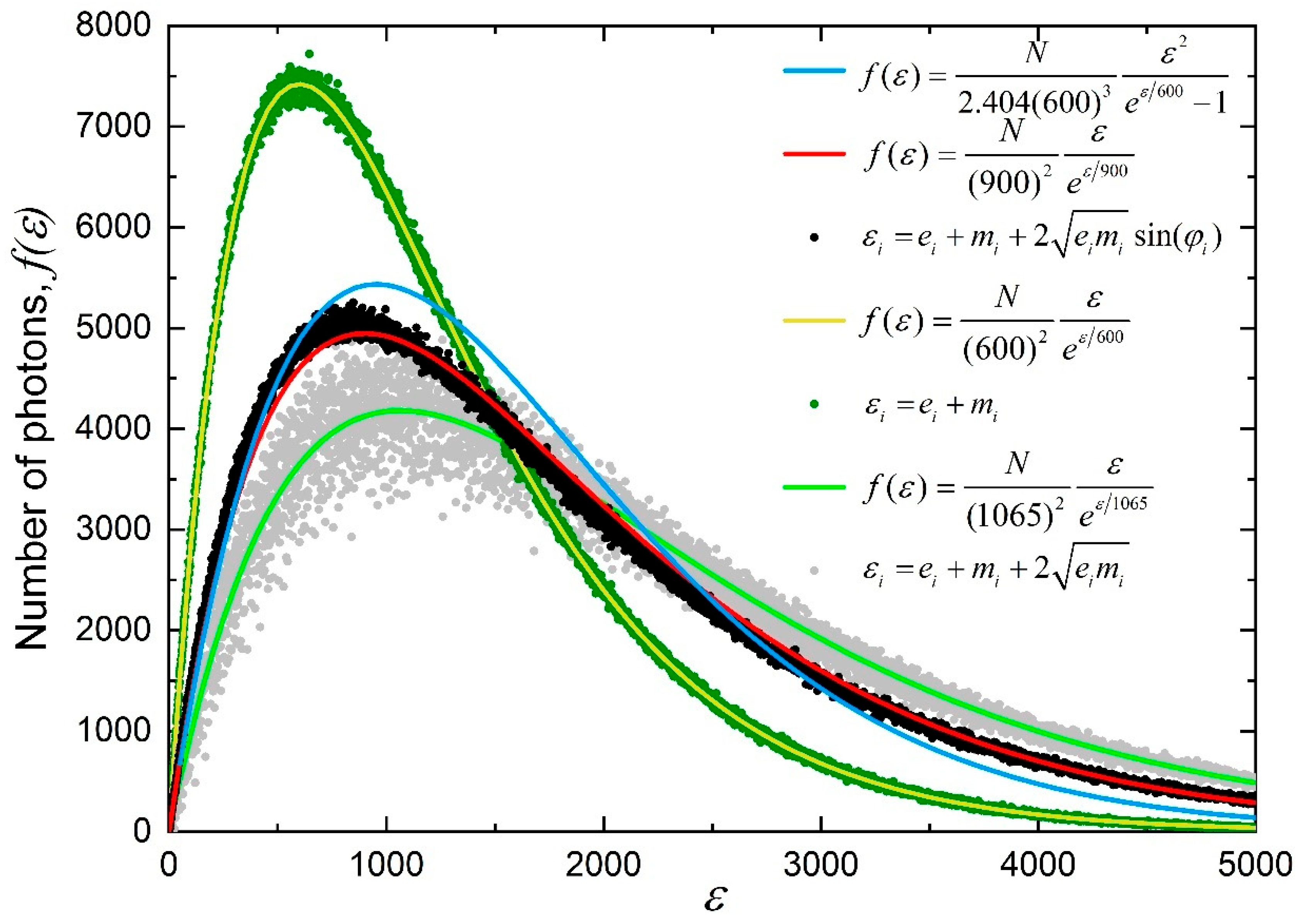

The distribution of photons by energy for the structure (9) is quite close to Planckian spectrum with the same temperature as the components (

) and the same total number of photons

(

Figure 1). Rotational energy does not come here with an independent degree of freedom. It is a function of the magnitudes of fields and the angle

.

The simulated distribution can be approximated better with the function

The distribution is compared to function graphs for the same total number of photons . The graph for Wien’s formula is represented by the grey line. Wien’s formula, which preceded Planck’s law (blue line), accurately fits the energy distribution for a three-degree freedom structure () with a mean photon energy of . In contrast, the mean photon energy for Planck’s law is . The red line is the function graph that fits well energy distribution for a structure with two degrees of freedom (). The red line comparison to the distribution for the structure (9) involves 50% temperature increase to account for additional rotational energy in the simulated distribution, raising the mean photon energy to .

The three orders energy range corresponds to the maximum achievable range in the blackbody radiation experiments. The dispersion of the distribution, given an equal number of photons, is markedly narrower for (9) compared to (7) in [

8].

For this function, the temperature must be adjusted to account for any rotational energy. The

Figure 2 shows three such distributions: 1.) for linearly polarized light (

,

— pure two degrees of freedom, ideal fit); 2.) for the unpolarized mixture (

varies, same as in

Figure 1); and 3.) for circular/elliptical polarization with maximum rotational energy contribution (

,

).

5. Understanding the Field Energy and Momentum

The explanation of the blackbody radiation spectrum, based on the definition of energy density (6), suggests that the blackbody radiation phenomenon supports the photon structure concept. According to this idea, photons are composite entities like mesons, but their

statistics is determined by their structure rather than Bose–Einstein statistics [

8].

On the other hand, the relativistic relationship between energy and momentum for massless particles

imposes a constraint relevant not only to photons but also to the field energy and momentum densities. Due to this constraint, the definitions of classical theory (1) and (3) cannot be considered as total energy and momentum densities. They can be categorized into two distinct yet complementary groups: translational (Maxwell’s energy density — translational energy, linear momentum, light pressure) and rotational (the Poynting vector — rotational energy, angular momentum). This categorization would clarify the relationship between fields, momentum, and energy.

Although the mathematical formulation of Poynting's theorem remains unchanged (2), its physical interpretation differs: the work performed by moving charges modifies both translational and rotational field energies. These two types of energy contribute to the energy flux. In terms of photons, continuity is ensured through the conservation of their total number in the system without emission and absorption.

6. Possible Experimental Verifications

According to structure (9), the blackbody radiation spectrum is not universally unpolarized. Function (10) can be employed to estimate the polarization variation with energy in the overall unpolarized spectrum. It shows a transition from predominantly linear polarization at lower energies to more circular or elliptical polarization at higher energies (

Figure 2). The current quantum theory does not account for these variations in the polarization of the blackbody radiation spectrum.

For instance, for linear polarization without angular momentum or rotational energy, the angle between the field vectors in (9) would be zero, resulting in the energy distribution for duplets

that is depicted with the dark green dots in

Figure 2 and indicates a peak at lower energy than the Planckian spectrum. This theoretical shape of the energy spectrum could be empirically tested as proposed in [

8].

The function (10) provides a perfect fit for the distribution of duplets (yellow line) but works quite well for other polarization states with temperature adjustments for rotational energy.

Some modern cosmic microwave background experiments provide polarization data along with energy measurements [

26]. Yet, the author is not aware of any lab experiments with calibrated blackbody source and controlled polarization.

The first reliable demonstrations of radiation pressure by Lebedev and others occurred in the early twentieth century. Later, Nichols’ and Hull’s measurement accuracy was questioned (see pages 1827-1828 in [

27] and references therein). The author is unaware of any precise measurements of radiation pressure or linear momentum conducted since, although the momentum transfer is leveraged in several applications. Maxwell's theory states that the radiation pressure in the direction of propagation is determined by the radiation energy density. Only translational energy influences radiation pressure according to the new energy density definition. Further experiments are necessary to determine if polarization has an impact on radiation pressure.

Measurements of radiation angular momentum have gained considerable attention lately. Such measurements can be refined to provide detailed information for evaluating photon energy (9). The experimental setup to measure photon spin angular momentum and optical torque [

15] can be seen as an example. This class of experiments employs a laser as a source of coherent light, allowing manipulation of the polarization state and other parameters.

7. Conclusion

While there is a well-developed mathematical model for electromagnetic phenomena, this does not imply a complete understanding of the underlying physics. Maxwell’s definition of field energy density, along with the Poynting vector, are fundamental elements in classical electrodynamics and theories based on complex vectors or tensors. However, the experimental validation supporting the physical interpretation of these mathematical constructs remains incomplete, and their physical significance has yet to be clarified.

The photon structure offers an understanding of photon energy and the field energy density as a sum of kinetic and rotational parts. This new energy definition integrates established expressions. As shown in this investigation, the structure broadens the scope of electromagnetic theory to explain the blackbody radiation spectrum. Furthermore, the blackbody radiation spectrum along with the angular momentum of light serve as empirical facts that refine the meaning of Poynting's theorem.

The combination of geometric algebra and computational statistical mechanics methods enabled this analysis. The evaluation of photon structure is based on the non-spatial aspects of Planck's law. Nevertheless, the spatial factor of Planck's law could potentially be utilized to incorporate spatial properties into the theoretical framework.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgements

The author is thankful to Valeri Golovlev for fruitful, stimulating discussions and critical comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Dyson, F. J. Why is Maxwell’s theory so hard to understand? extract from the James Clerk Maxwell Commemorative Booklet for The Fourth International Congress on Industrial and Applied Mathematics, 1999, Available online: https://clerkmaxwellfoundation.org/DysonFreemanArticle.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Hestenes, D. Space-Time Algebra; Gordon and Breach: New York, NY, USA, 1966.

- Dressel, J.; Bliokh, K.Y.; Nori, F. Spacetime algebra as a powerful tool for electromagnetism. Phys. Rep. 2015, 589, 1–71. [CrossRef]

- Muralidhar, K. Algebra of Complex Vectors and Applications in Electromagnetic Theory and Quantum Mechanics. Mathematics 2015, 3, 781–842. [CrossRef]

- Poynting, J.H. The wave motion of a revolving shaft, and a suggestion as to the angular momentum in a beam of circularly polarised light. Proc. R. Soc. London. Ser. A, Contain. Pap. a Math. Phys. Character 1909, 82, 560–567. [CrossRef]

- Beth, R.A. Mechanical Detection and Measurement of the Angular Momentum of Light. Phys. Rev. B 1936, 50, 115–125. [CrossRef]

- Muralidhar, K. The Structure of Photon in Complex Vector Space. Progr. Phys. 12, 2016, 3, 291–296.

- Khaneles, A. Does the Blackbody Radiation Spectrum Suggest an Intrinsic Structure of Photons? Quantum Rep. 2024, 6, 110–119.

- McDonald, K.T. Alternative Forms of the Poynting Vector. Princeton University, 2020, Available online: http://kirkmcd.princeton.edu/examples/poynting_alt.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Poynting, J.H. XV. On the transfer of energy in the electromagnetic field. Philos. Trans. R. Soc. Lond. 1884, 175, 343–361. [CrossRef]

- McDonald, K.T. Orbital and Spin Angular Momentum of Electromagnetic Fields. Princeton University, 2021, Available online: http://kirkmcd.princeton.edu/examples/spin.pdf (accessed on 16 June 2025).

- Feynman, R.P.; Leighton, R.B.; Sands, M. The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol. II; Addison-Wesley: Reading, MA, USA, 1965.

- Campos, I. and Jimenez, J. L. About Poynting's theorem. Eur. J. Phys. 1992, 13 117.

- Barnett, S.M.; Allen, L.; Cameron, R.P. et al On the natures of the spin and orbital parts of optical angular momentum. J. Opt. 2016, 18 064004.

- He, L.; Li, H.; Li, M. Optomechanical measurement of photon spin angular momentum and optical torque in integrated photonic devices. Sci. Adv. 2016, 2, e1600485–1600485. [CrossRef]

- Tiwari, S.C. Nature of the Angular Momentum of Light: Rotational Energy and Geometric Phase. arXiv 2006, arXiv:quant-ph/0609015.

- Gibbs, J.W. The Scientific Papers of J. Willard Gibbs, Vol. 2, Longmans, Green and Co., 1906, p. 84.

- Weber, H. Die partiellen Differential-Gleichungen der mathematischen Physik nach Riemann’s Vorlesungen, Friedrich Vieweg und Sohn, Braunschweig, 1901, p. 348.

- Białynicki-Birula, I. Photon wave function. Prog. Opt. 1996, 36, 245–294.

- Silberstein, L. Elektromagnetische Grundgleichungen in bivektorieller Behandlung. Ann. der Phys. 1907, 327, 579–586. [CrossRef]

- Lindell, I.V. Complex Vector Algebra in Electromagnetics. Int. J. Electr. Eng. Educ. 1983, 20, 33–47. [CrossRef]

- Belinfante, F. On the spin angular momentum of mesons. Physica 1939, 6, 887–898. [CrossRef]

- Ohanian, H.C. What is spin? Am. J. Phys. 1986, 54, 500–505.

- Vold, T.G. An introduction to geometric calculus and its application to electrodynamics. Am. J. Phys. 1993, 61, 505–513. [CrossRef]

- Baylis, W.E. Electrodynamics: A Modern Geometric Approach, Birkhäuser, 2002, p.98.

- Planck Collaboration; Akrami, Y.; Arroja, F.; Ashdown, M.; Aumont, J.; Baccigalupi, C.; Ballardini, M.; Banday, A.; Barreiro, R.; Bartolo, N.; et al. Planck 2018 results. I. Overview and the cosmological legacy of Planck. 2020. [CrossRef]

- Loudon, R.; Baxter, C. Contributions of John Henry Poynting to the understanding of radiation pressure. Proc. R. Soc. A: Math. Phys. Eng. Sci. 2012, 468, 1825–1838. [CrossRef]

|

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).