Submitted:

02 July 2025

Posted:

03 July 2025

You are already at the latest version

Abstract

Keywords:

1.0. Introduction to Municipal Solid Waste

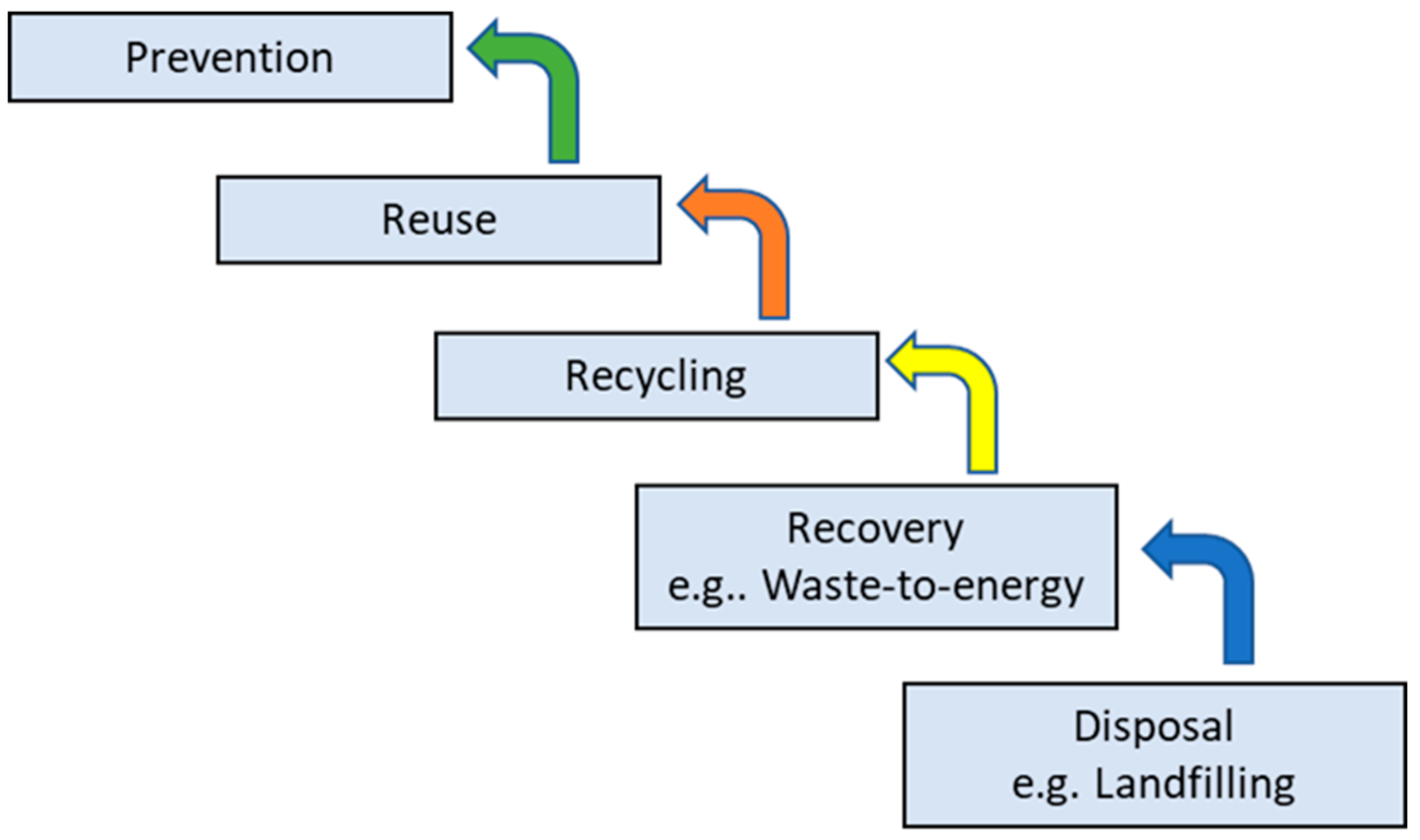

1.1. Integrated Solid Waste Management (ISWM)

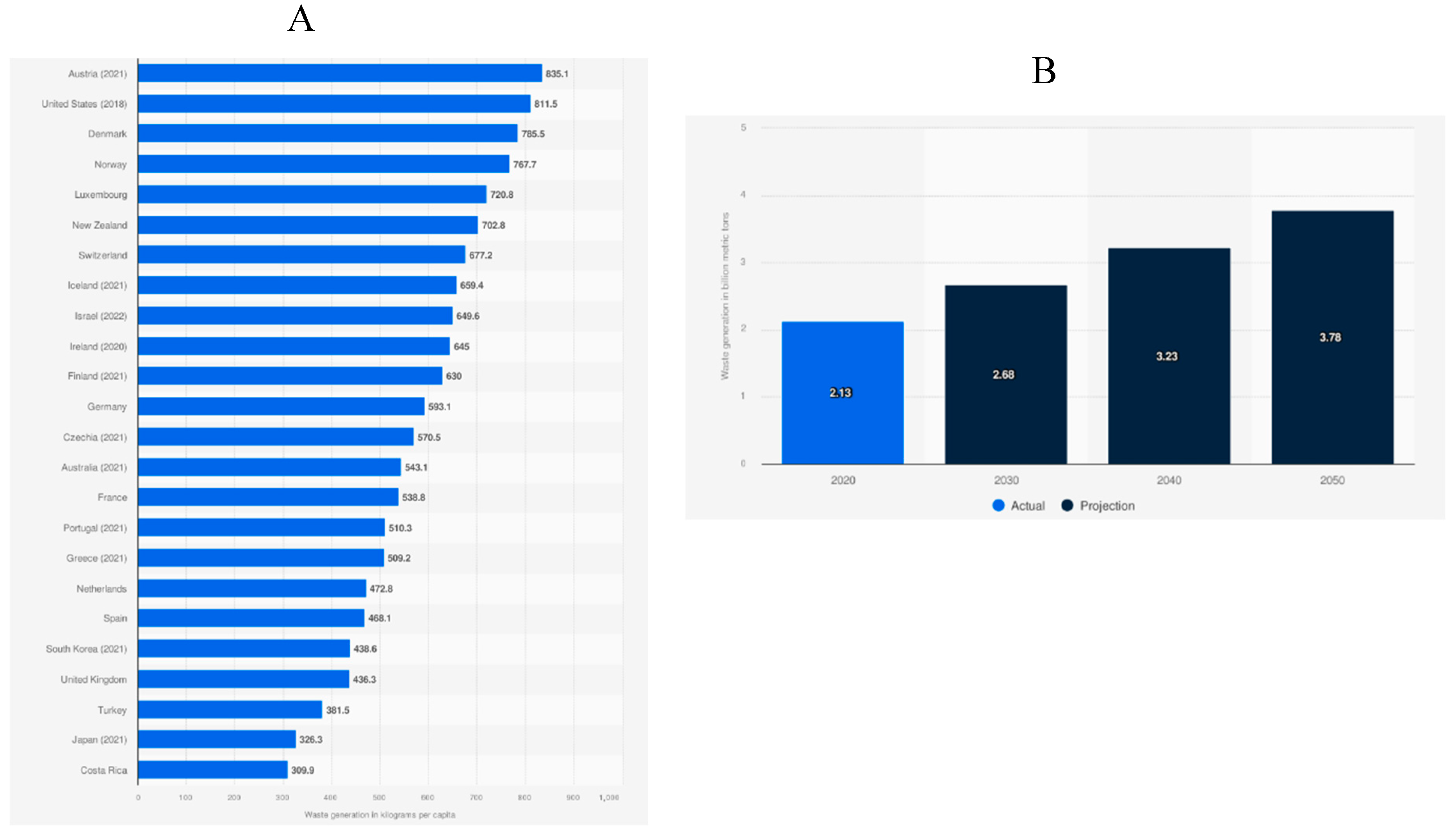

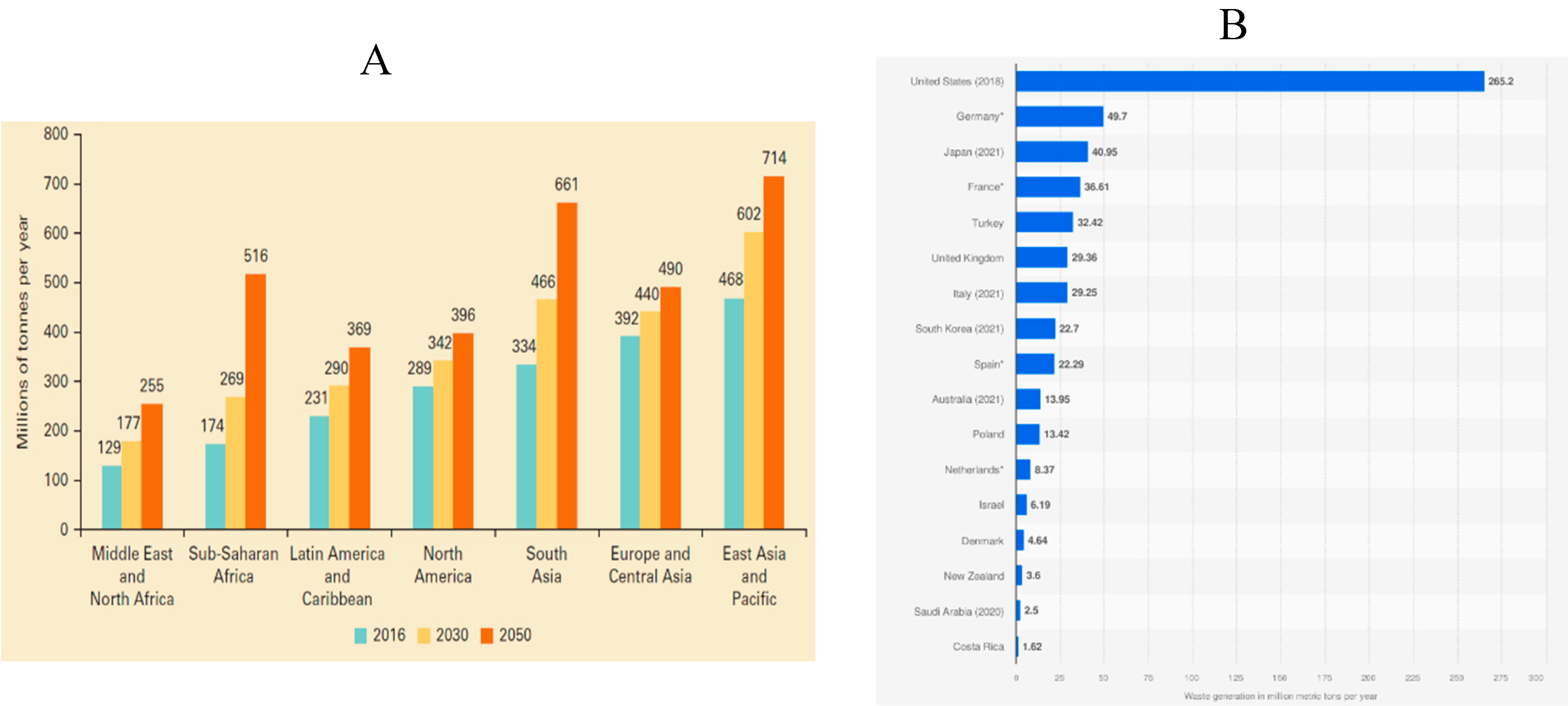

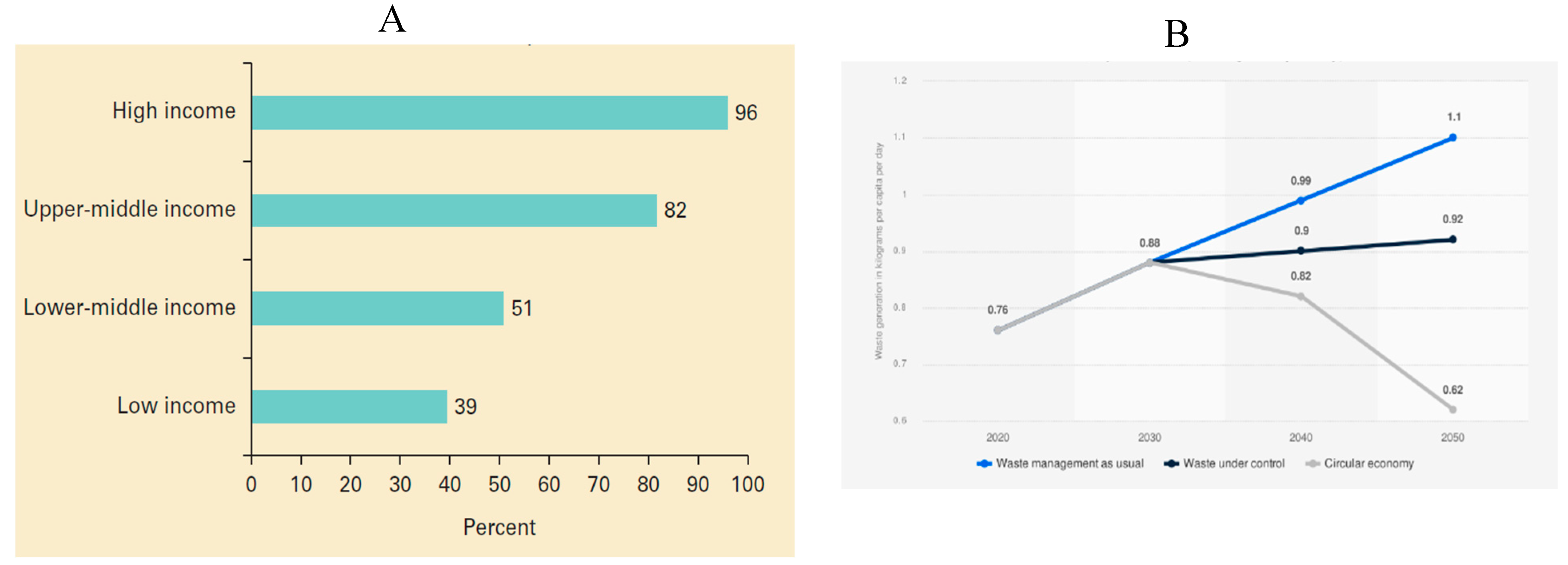

1.2. Rates of Municipal Solid Waste Generation

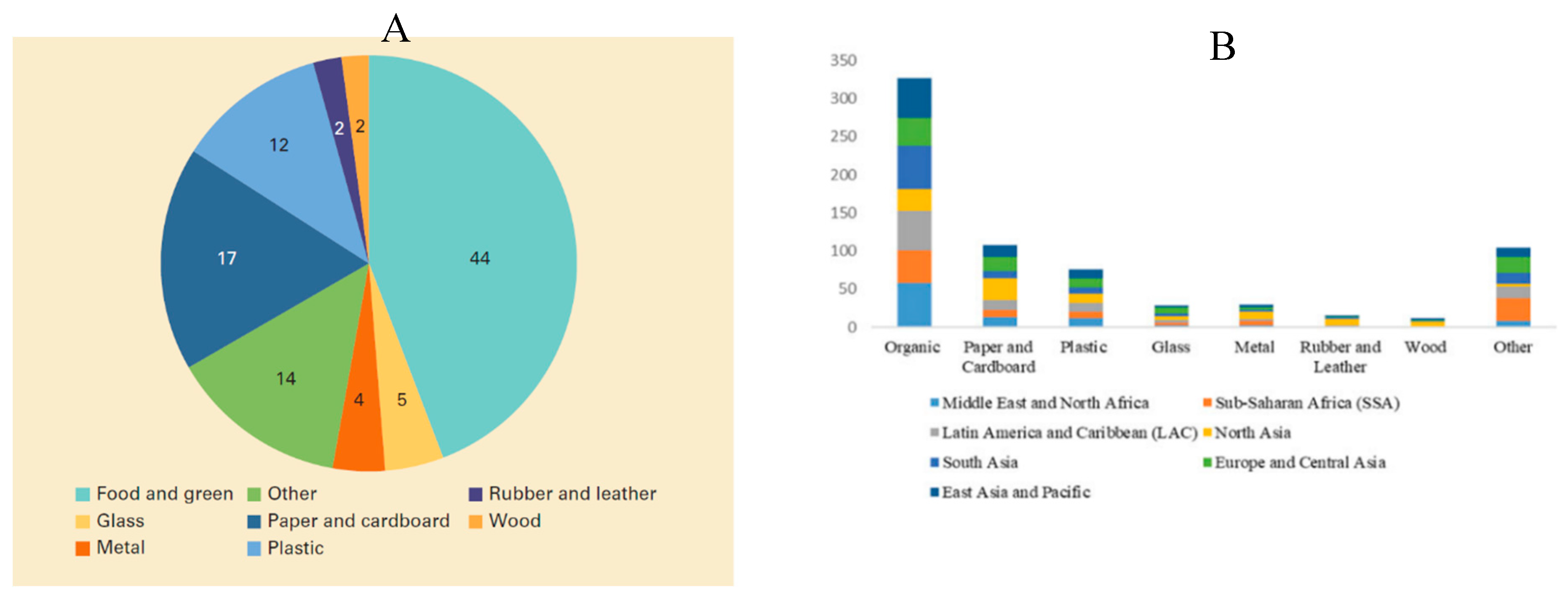

1.3. Municipal Solid Waste: Characteristics and Composition

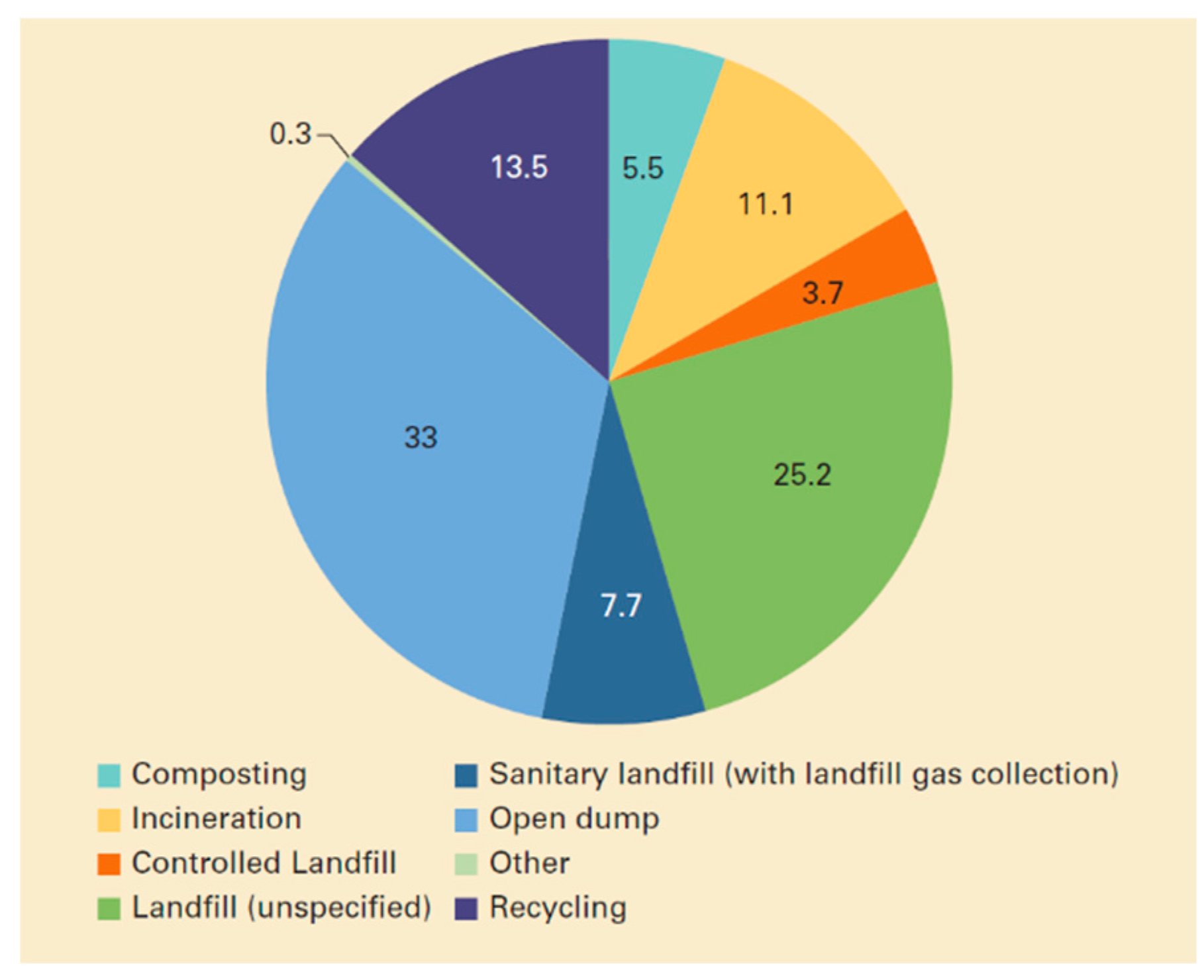

2.0. Management Municipal Solid Waste

- Producing waste

- Collecting, handling, and transporting waste

- Disposing of, processing, and treating waste [22]

2.1. Municipal Solid Waste Management in the European Union (EU): A brief overview

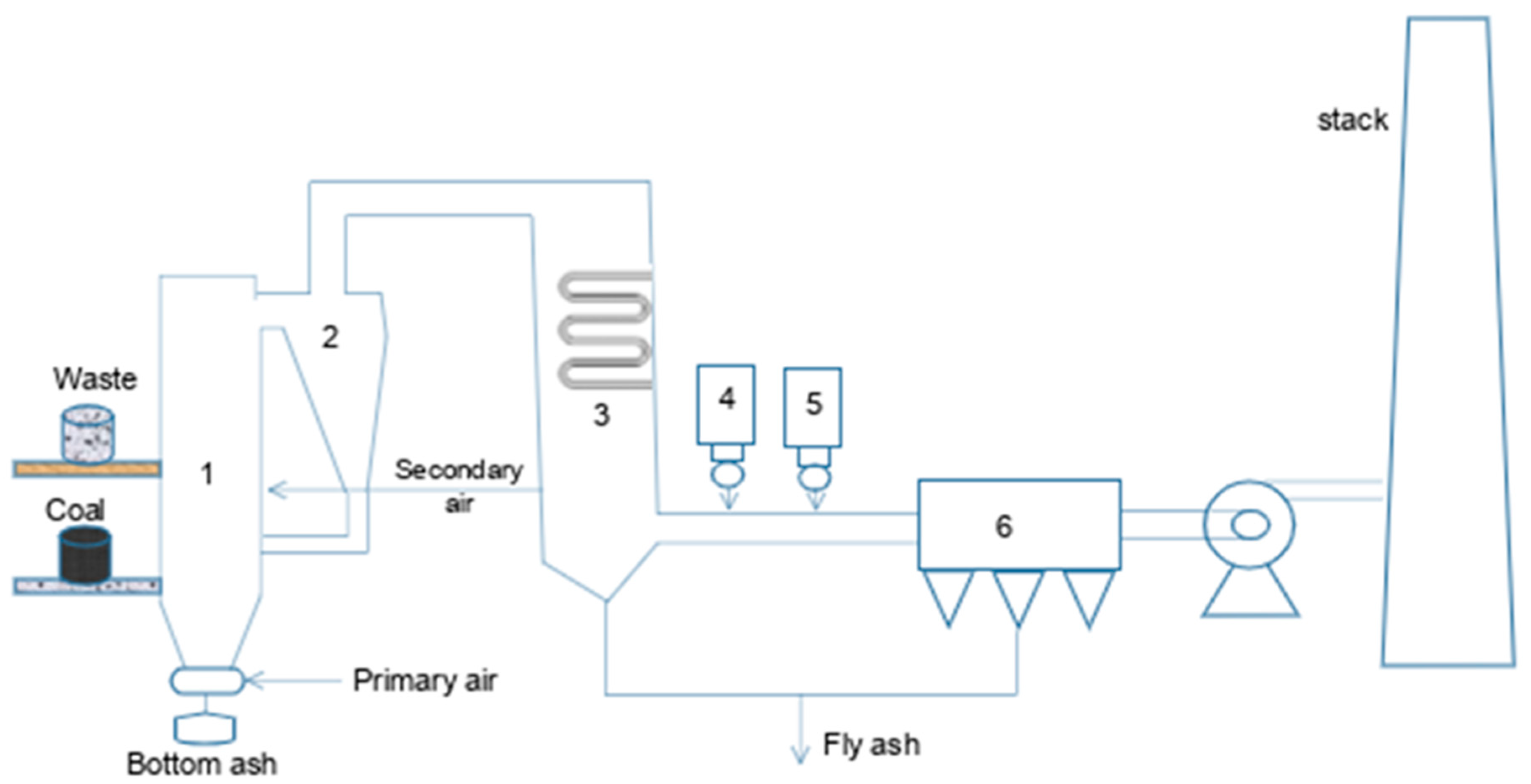

2.2. Incineration as a Conventional Approach of Municipal Solid Waste Management

- i.

- reduction of waste mass (up to 75%) and volume (up to 90%).

- i.

- ii. organic contaminants destruction, and inertization (solidification and stabilization) of residual waste.

- i.

- iii. utilization of the residual waste enthalpy for energy production

- i.

- iv. transfer of some residues into recyclable secondary products (e.g., phosphorus or metals recovery)

2.2.1. Bottom Ash

2.2.2. Fly Ash

2.2.3. Air Pollution Control Residue

3.0. Potential Contaminants of MSW and their Impacts on the Environment3.1. Landfills as Culprits?

3.1.1. Gases

3.1.2. Metals, Minerals, Natural Inorganic Fibres and Persistent Organic Pollutants

3.2. The Focus: Metals as Components of Total Waste Composition

3.3. Some Global Guidelines for Sampling of MSW and Its Residues for Metal Analysis

3.3.1. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) - United States

3.3.2. EU Waste Framework Directive - European Union

3.3.3. The ANZECC Waste Classification Guidelines - Australia and New Zealand (ANZECC)

3.3.4. Canadian Environmental Protection Act (CEPA) - Canada

3.3.5. National Environmental Monitoring Standards (NEMS) - China

3.3.6. Other Regions - Global

3.4. Sampling Techniques for Ash from Municipal Waste Incineration Plants

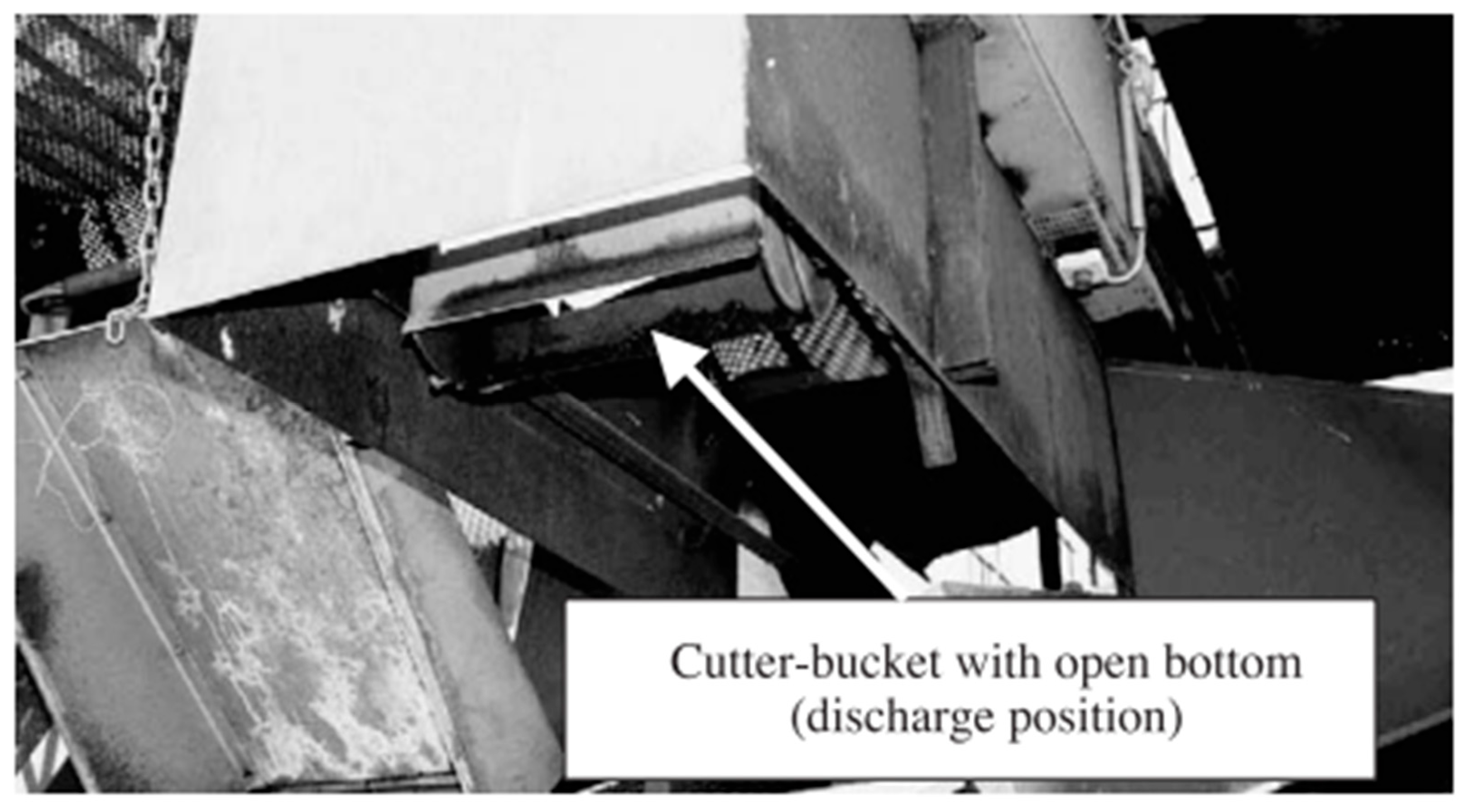

3.4.1. Mechanical Sampling

3.4.2. Stopped Belt Sampling

3.4.3. Manual Sampling

3.4.5. Uncertainty and Error Estimation

4.0. Analytical Approaches for Analysis of Metals in MSW and its Residues

4.1. Parameters to Evaluate for Metal Pollution Indicators in MSW and its Residues

4.1.1. Degree of Contamination Index

4.1.2. Degree of Contamination (mCd) in Matrices Is Defined as:

4.1.3. Index of Geoaccummulation (Igeo)

4.1.4. Enrichment Factor

4.1.5. Pollution Load Index (PLI)

4.1.6. Potential Ecological Risk Index (PERI)

4.2. Health Risk Assessment

Conclusion

References

- Polish Ministry of Climate and Environment, National Waste Management Plan 2022: Annex to the Resolution No 88 of the Council of Ministers of 1 July 2016 (item 784), (2016).

- Waste Management, Recycling: Poland is slowly catching up, WMW (2022). https://waste-management-world.com/artikel/recycling-poland-is-slowly-catching-up/ (accessed August 22, 2022).

- World Bank Group, What a Waste: An Updated Look into the Future of Solid Waste Management, Waste Atlas (2018). https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/immersive-story/2018/09/20/what-a-waste-an-updated-look-into-the-future-of-solid-waste-management (accessed June 27, 2025).

- M. Ghaffariraad, M. Ghanbarzadeh Lak, Landfill Leachate Treatment Through Coagulation-flocculation with Lime and Bio-sorption by Walnut-shell, Environmental Management 68 (2021) 226–239. [CrossRef]

- M. Ghanbarzadeh Lak, M.R. Sabour, E. Ghafari, A. Amiri, Energy consumption and relative efficiency improvement of Photo-Fenton – Optimization by RSM for landfill leachate treatment, a case study, Waste Management 79 (2018) 58–70. [CrossRef]

- M. Ghanbarzadeh Lak, M.R. Sabour, A. Amiri, O. Rabbani, Application of quadratic regression model for Fenton treatment of municipal landfill leachate, Waste Management 32 (2012) 1895–1902. [CrossRef]

- R.C. Herdman, G.E. Haughie, L.E. Campbell, D. Axelrod, N. Vianna, W. Hennessy, J. Sachs, C. Hoffman, M. Cuddy, THE OFFICE OF PUBLIC HEALTH, 1978. https://www.health.ny.gov/environmental/investigations/love_canal/lctimbmb.htm (accessed June 27, 2025).

- C.R. Rhyner, L.J. Schwartz, R.B. Wenger, M.G. Kohrell, Waste Management and Resource Recovery, CRC Press, Boca Raton, 2017. [CrossRef]

- M. Ghanbarzadeh Lak, M. Ghaffariraad, H. Jahangirzadeh Soureh, Characteristics and Impacts of Municipal Solid Waste (MSW), in: A. Anouzla, S. Souabi (Eds.), Technical Landfills and Waste Management : Volume 1: Landfill Impacts, Characterization and Valorisation, Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, 2024: pp. 31–92. [CrossRef]

- S. Kaze, L.C. Yao, P. Bhada Tata, F. Van Woerden, T.M.R. Martin, K.R.B. Serrona, R. Thakur, F. Pop, S. Hayashi, G. Solorzano, N.S. Alencastro Larios, R.A. Poveda Maimoni, A. Isamil, What a Waste 2.0 : A Global Snapshot of Solid Waste Management to 2050Kaza,Silpa; Yao,Lisa Congyuan; Bhada Tata,Perinaz; Van Woerden,Frank; Martin,Thierry Michel Rene; Serrona,Kevin Roy B.; Thakur,Ritu; Pop,Flaviu; Hayashi,Shiko; Solorzano,Gustavo; Alencastro Larios,Nadya Selene; Poveda Maimoni,Renan Alberto; Ismail,Anis, Washington DC, 2021. https://documents.worldbank.org/en/publication/documents-reports/documentdetail/en/697271544470229584 (accessed June 27, 2025).

- M. Zari, Characteristics and Impact Assessment of Municipal Solid Waste (MSW), in: A. Anouzla, S. Souabi (Eds.), Technical Landfills and Waste Management : Volume 1: Landfill Impacts, Characterization and Valorisation, Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, 2024: pp. 93–113. [CrossRef]

- S. Sikder, M. Toha, Md. Mostafizur Rahman, An Overview on Municipal Solid Waste Characteristics and Its Impacts on Environment and Human Health, in: A. Anouzla, S. Souabi (Eds.), Technical Landfills and Waste Management : Volume 1: Landfill Impacts, Characterization and Valorisation, Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, 2024: pp. 135–155. [CrossRef]

- F.Y.Y. Ling, D.S.A. Nguyen, Strategies for construction waste management in Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam, Built Environment Project and Asset Management 3 (2013) 141–156. [CrossRef]

- M.R. Alavi Moghadam, N. Mokhtarani, B. Mokhtarani, Municipal solid waste management in Rasht City, Iran, Waste Management 29 (2009) 485–489. [CrossRef]

- J.E. Arikibe, B.M. Cieślik, Assessing Metal Distribution in Diverse Incineration Ashes: Implications for Sustainable Waste Management in Case of Different Incineration Facilities, Water Air Soil Pollut 236 (2025) 81. [CrossRef]

- Z. Gueboudji, M. Mahmoudi, K. Kadi, K. Nagaz, Characteristics and Impacts of Municipal Solid Waste (MSW): A Review, in: A. Anouzla, S. Souabi (Eds.), Technical Landfills and Waste Management : Volume 1: Landfill Impacts, Characterization and Valorisation, Springer Nature Switzerland, Cham, 2024: pp. 115–134. [CrossRef]

- Alves, Statista - The Statistics Portal, Bruna (2025). https://www.statista.com/ (accessed June 27, 2025).

- OECD, The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development, OECD (2025). https://www.oecd.org/en.html (accessed June 27, 2025).

- The World Bank Group, Trends in Solid Waste Management, (2025). https://datatopics.worldbank.org/what-a-waste/trends_in_solid_waste_management.html (accessed June 27, 2025).

- UNEP, ed., Beyond an age of waste: turning rubbish into a resource, UNEP, Nairobi, 2024.

- W.E.C. WEC, World energy resources-2016, 2016. https://www.worldenergy.org/assets/images/imported/2016/10/World-Energy-Resources-Full-report-2016.10.03.pdf.

- S. Nanda, F. Berruti, Municipal solid waste management and landfilling technologies: a review, Environ Chem Lett 19 (2021) 1433–1456. [CrossRef]

- K.D. Sharma, S. Jain, Municipal solid waste generation, composition, and management: the global scenario, Social Responsibility Journal 16 (2020) 917–948. [CrossRef]

- R.G. de S.M. Alfaia, A.M. Costa, J.C. Campos, Municipal solid waste in Brazil: A review, Waste Manag Res 35 (2017) 1195–1209. [CrossRef]

- S. Dack, E. Cheek, S. Morrow, D. Medlock, A. Dobney, Impacts on health of emissions from landfill sites, GOV.UK (2024). https://www.gov.uk/government/publications/landfill-sites-impact-on-health-from-emissions/impacts-on-health-of-emissions-from-landfill-sites (accessed June 27, 2025).

- B.M. Cieślik, J. Namieśnik, P. Konieczka, Review of sewage sludge management: standards, regulations and analytical methods, Journal of Cleaner Production 90 (2015) 1–15. [CrossRef]

- E. Durmusoglu, I.M. Sanchez, M.Y. Corapcioglu, Permeability and compression characteristics of municipal solid waste samples, Environ Geol 50 (2006) 773–786. [CrossRef]

- J.N. Ihedioha, P.O. Ukoha, N.R. Ekere, Ecological and human health risk assessment of heavy metal contamination in soil of a municipal solid waste dump in Uyo, Nigeria, Environ Geochem Health 39 (2017) 497–515. [CrossRef]

- US Cencus Bureau, Population Clock, Https://Www.Census.Gov/Popclock/ (2025). https://www.census.gov/popclock/ (accessed June 27, 2025).

- D. Gavrilescu, B.-C. Seto, C. Teodosiu, Sustainability analysis of packaging waste management systems: A case study in the Romanian context, Journal of Cleaner Production 422 (2023) 138578. [CrossRef]

- L. Gritsch, J. Lederer, A historical-technical analysis of packaging waste flows in Vienna, Resources, Conservation and Recycling 194 (2023) 106975. [CrossRef]

- J. Lederer, D. Schuch, The contribution of waste and bottom ash treatment to the circular economy of metal packaging: A case study from Austria, Resources, Conservation and Recycling 203 (2024) 107461. [CrossRef]

- Ahsan, M. Alamgir, M.M. El-Sergany, S. Shams, M.K. Rowshon, N.N.N. Daud, Assessment of Municipal Solid Waste Management System in a Developing Country, Chinese Journal of Engineering 2014 (2014) 561935. [CrossRef]

- F. Cucchiella, I. D’Adamo, M. Gastaldi, Strategic municipal solid waste management: A quantitative model for Italian regions, Energy Conversion and Management 77 (2014) 709–720. [CrossRef]

- A.M. Damghani, G. Savarypour, E. Zand, R. Deihimfard, Municipal solid waste management in Tehran: Current practices, opportunities and challenges, Waste Management 28 (2008) 929–934. [CrossRef]

- K. Mizerna, Determination of forms of heavy metals in bottom ash from households using sequential extraction, E3S Web Conf. 44 (2018) 00116. [CrossRef]

- J. Poluszyńska, The content of heavy metal ions in ash from waste incinerated in domestic furnaces, Archives of Environmental Protection; 2020; Vol. 46; No 2; 68-73 (2020). https://journals.pan.pl/dlibra/publication/133476/edition/116623 (accessed June 27, 2025).

- M. Alwaeli, An overview of municipal solid waste management in Poland. The current situation, problems and challenges, Environment Protection Engineering 41 (2015) 181–193. [CrossRef]

- B. Klojzy-Karczmarczyk, S. Makoudi, Analysis of municipal waste generation rate in Poland compared to selected European countries, E3S Web Conf. 19 (2017) 02025. [CrossRef]

- X. Zhao, J. Yang, N. Ning, Z. Yang, Chemical stabilization of heavy metals in municipal solid waste incineration fly ash: a review, Environ Sci Pollut Res 29 (2022) 40384–40402. [CrossRef]

- Valavanidis, N. Iliopoulos, K. Fiotakis, G. Gotsis, Metal leachability, heavy metals, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons and polychlorinated biphenyls in fly and bottom ashes of a medical waste incineration facility, Waste Manag Res 26 (2008) 247–255. [CrossRef]

- 42. G. Weibel, Optimized Metal Recovery from Fly Ash from Municipal Solid Waste Incineration, Inauguraldissertation der Philosophisch-naturwissenschaftlichen Fakultät der Universität Bern, Universität Bern, 2017.

- G. Weibel, U. Eggenberger, D.A. Kulik, W. Hummel, S. Schlumberger, W. Klink, M. Fisch, U.K. Mäder, Extraction of heavy metals from MSWI fly ash using hydrochloric acid and sodium chloride solution, Waste Management 76 (2018) 457–471. [CrossRef]

- S. Yao, L. Zhang, Y. Zhu, J. Wu, Z. Lu, J. Lu, Evaluation of heavy metal element detection in municipal solid waste incineration fly ash based on LIBS sensor, Waste Management 102 (2020) 492–498. [CrossRef]

- B.M. Cieślik, J. Namieśnik, P. Konieczka, Review of sewage sludge management: standards, regulations and analytical methods, Journal of Cleaner Production 90 (2015) 1–15. [CrossRef]

- J. Yu, L. Sun, J. Xiang, L. Jin, S. Hu, S. Su, J. Qiu, Physical and chemical characterization of ashes from a municipal solid waste incinerator in China, Waste Manag Res 31 (2013) 663–673. [CrossRef]

- H. Belevi, M. Langmeier, Factors Determining the Element Behavior in Municipal Solid Waste Incinerators. 2. Laboratory Experiments, Environ. Sci. Technol. 34 (2000) 2507–2512. [CrossRef]

- H. Belevi, H. Moench, Factors Determining the Element Behavior in Municipal Solid Waste Incinerators. 1. Field Studies, Environ. Sci. Technol. 34 (2000) 2501–2506. [CrossRef]

- G. Weibel, U. Eggenberger, D.A. Kulik, W. Hummel, S. Schlumberger, W. Klink, M. Fisch, U.K. Mäder, Extraction of heavy metals from MSWI fly ash using hydrochloric acid and sodium chloride solution, Waste Management 76 (2018) 457–471. [CrossRef]

- Y.-Y. Long, D.-S. Shen, H.-T. Wang, W.-J. Lu, Y. Zhao, Heavy metal source analysis in municipal solid waste (MSW): Case study on Cu and Zn, Journal of Hazardous Materials 186 (2011) 1082–1087. [CrossRef]

- V. Funari, S.N.H. Bokhari, L. Vigliotti, T. Meisel, R. Braga, The rare earth elements in municipal solid waste incinerators ash and promising tools for their prospecting, Journal of Hazardous Materials 301 (2016) 471–479. [CrossRef]

- L.S. Morf, P.H. Brunner, S. Spaun, Effect of operating conditions and input variations on the partitioning of metals in a municipal solid waste incinerator, Waste Manag Res 18 (2000) 4–15. [CrossRef]

- J. Yao, W.-B. Li, Q.-N. Kong, Y.-Y. Wu, R. He, D.-S. Shen, Content, mobility and transfer behavior of heavy metals in MSWI bottom ash in Zhejiang province, China, Fuel 89 (2010) 616–622. [CrossRef]

- M. Ajorloo, M. Ghodrat, J. Scott, V. Strezov, Heavy metals removal/stabilization from municipal solid waste incineration fly ash: a review and recent trends, J Mater Cycles Waste Manag (2022). [CrossRef]

- W. Chen, G.M. Kirkelund, P.E. Jensen, L.M. Ottosen, Comparison of different MSWI fly ash treatment processes on the thermal behavior of As, Cr, Pb and Zn in the ash, Waste Management 68 (2017) 240–251. [CrossRef]

- A.-L. Fabricius, M. Renner, M. Voss, M. Funk, A. Perfoll, F. Gehring, R. Graf, S. Fromm, L. Duester, Municipal waste incineration fly ashes: from a multi-element approach to market potential evaluation, Environ Sci Eur 32 (2020) 88. [CrossRef]

- F. Jiao, L. Zhang, Z. Dong, T. Namioka, N. Yamada, Y. Ninomiya, Study on the species of heavy metals in MSW incineration fly ash and their leaching behavior, Fuel Processing Technology 152 (2016) 108–115. [CrossRef]

- F. Liu, H.-Q. Liu, G.-X. Wei, R. Zhang, T.-T. Zeng, G.-S. Liu, J.-H. Zhou, Characteristics and Treatment Methods of Medical Waste Incinerator Fly Ash: A Review, Processes 6 (2018) 173. [CrossRef]

- L.S. Morf, R. Gloor, O. Haag, M. Haupt, S. Skutan, F.D. Lorenzo, D. Böni, Precious metals and rare earth elements in municipal solid waste – Sources and fate in a Swiss incineration plant, Waste Management 33 (2013) 634–644. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, P.-J. He, L.-M. Shao, Fate of heavy metals during municipal solid waste incineration in Shanghai, Journal of Hazardous Materials 156 (2008) 365–373. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K. Chandel, Effect of ageing on waste characteristics excavated from an Indian dumpsite and its potential valorisation, Process Safety and Environmental Protection 134 (2020) 24–35. [CrossRef]

- M. Danthurebandara, S. Van Passel, I. Vanderreydt, K. Van Acker, Assessment of environmental and economic feasibility of Enhanced Landfill Mining, Waste Manag 45 (2015) 434–447. [CrossRef]

- T. Parker, J. Dottridge, S. Kelly, INVESTIGATION OF THE COMPOSITION AND EMISSIONS OF TRACE COMPONENTS IN LANDFILL GAS, 2002.

- Y.-C. Weng, T. Fujiwara, H.J. Houng, C.-H. Sun, W.-Y. Li, Y.-W. Kuo, Management of landfill reclamation with regard to biodiversity preservation, global warming mitigation and landfill mining: experiences from the Asia–Pacific region, Journal of Cleaner Production 104 (2015) 364–373. [CrossRef]

- P. Frändegård, J. Krook, N. Svensson, M. Eklund, Resource and Climate Implications of Landfill Mining, Journal of Industrial Ecology 17 (2013) 742–755. [CrossRef]

- D. Huang, Y. Du, Q. Xu, J.H. Ko, Quantification and control of gaseous emissions from solid waste landfill surfaces, Journal of Environmental Management 302 (2022) 114001. [CrossRef]

- S.M. Monavari, S. Tajziehchi, R. Rahimi, Environmental Impacts of Solid Waste Landfills on Natural Ecosystems of Southern Caspian Sea Coastlines, JEP 04 (2013) 1453–1460. [CrossRef]

- L. Ziyang, W. Luochun, Z. Nanwen, Z. Youcai, Martial recycling from renewable landfill and associated risks: A review, Chemosphere 131 (2015) 91–103. [CrossRef]

- G.A. Dino, P. Rossetti, G. Biglia, M.L. Sapino, F.D. Mauro, H. Sarkka, F. Coulon, D. Gomes, L. Parejo-Bravo, P.Z. Aranda, A.L. Lopez, J. Lopez, E. Garamvolgyi, S. Stojanovic, A. Pizza, M.D.L. Feld, Smart ground project: a new approach to data accessibility and collection for raw materials and secondary raw materials in europe, Environ. Eng. Manag. J. 16 (2017) 1673–1684. [CrossRef]

- Assi, F. Bilo, A. Zanoletti, J. Ponti, A. Valsesia, R. La Spina, A. Zacco, E. Bontempi, Zero-waste approach in municipal solid waste incineration: Reuse of bottom ash to stabilize fly ash, Journal of Cleaner Production 245 (2020) 118779. [CrossRef]

- Singh, M.K. Chandel, Mobility and environmental fate of heavy metals in fine fraction of dumped legacy waste: Implications on reclamation and ecological risk, Journal of Environmental Management 304 (2022) 114206. [CrossRef]

- M. Abu-Daabes, H.A. Qdais, H. Alsyouri, Assessment of Heavy Metals and Organics in Municipal Solid Waste Leachates from Landfills with Different Ages in Jordan, Journal of Environmental Protection 4 (2013) 344–352. [CrossRef]

- K. Warren, A. Read, Landfill Mining: Goldmine or Minefield?, (2014). http://www.ismenvis.nic.in/Database/Landfill_Mining-Goldmine_or_Minefield_5478.aspx (accessed June 28, 2025).

- Sun, Q. Li, M. Zheng, G. Su, S. Lin, M. Wu, C. Li, Q. Wang, Y. Tao, L. Dai, Y. Qin, B. Meng, Recent advances in the removal of persistent organic pollutants (POPs) using multifunctional materials:a review, Environmental Pollution 265 (2020) 114908. [CrossRef]

- P.N. Nomngongo, J.C. Ngila, T.A.M. Msagati, B.P. Gumbi, E.I. Iwuoha, Determination of selected persistent organic pollutants in wastewater from landfill leachates, using an amperometric biosensor, Physics & Chemistry of the Earth 50–52 (2012) 252–261. [CrossRef]

- R. Weber, A. Watson, M. Forter, F. Oliaei, Review Article: Persistent organic pollutants and landfills - a review of past experiences and future challenges, Waste Manag Res 29 (2011) 107–121. [CrossRef]

- A.T. Nair, Bioaerosols in the landfill environment: an overview of microbial diversity and potential health hazards, Aerobiologia 37 (2021) 185–203. [CrossRef]

- G. Tchobanoglous, F. Kreith, Handbook of Solid Waste Management, McGraw Hill Professional, 2002.

- J. Dong, Y. Chi, Y. Tang, M. Ni, A. Nzihou, E. Weiss-Hortala, Q. Huang, Partitioning of Heavy Metals in Municipal Solid Waste Pyrolysis, Gasification, and Incineration, Energy Fuels 29 (2015) 7516–7525. [CrossRef]

- S. Smith, A critical review of the bioavailability and impacts of heavy metals in municipal solid waste composts compared to sewage sludge, Environment International 35 (2009) 142–156. [CrossRef]

- Y.-M. Li, Wang ,Chun-Feng, Wang ,Lin-Jun, Huang ,Tian-Yong, G.-Z. and Zhou, Removal of heavy metals in medical waste incineration fly ash by Na2EDTA combined with zero-valent iron and recycle of Na2EDTA: Acolumnar experiment study, Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 70 (2020) 904–914. [CrossRef]

- Y.-M. Li, Wang ,Chun-Feng, Wang ,Lin-Jun, Huang ,Tian-Yong, G.-Z. and Zhou, Removal of heavy metals in medical waste incineration fly ash by Na2EDTA combined with zero-valent iron and recycle of Na2EDTA: Acolumnar experiment study, Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 70 (2020) 904–914. [CrossRef]

- J.E. Arikibe, S. Prasad, Determination and comparison of selected heavy metal concentrations in seawater and sediment samples in the coastal area of Suva, Fiji, Marine Pollution Bulletin 157 (2020) 111157. [CrossRef]

- Necsulescu, L. Ionita, E. Bucur, Stationary sources emissions. Total Cd, Cr, Cu determination in exhaust gases from incinerators, Journal of Environmental Protection and Ecology 9 (2008) 1–14.

- K.-B. Li, Y. Zang, H. Wang, J. Li, G.-R. Chen, T.D. James, X.-P. He, H. Tian, Hepatoma-selective imaging of heavy metal ions using a ‘clicked’ galactosylrhodamine probe, Chem. Commun. 50 (2014) 11735–11737. [CrossRef]

- Y.H. Li, X. Peng, D.W. Li, K. Yang, The Environmental Toxicity of Heavy Metals in Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Fly Ash, Applied Mechanics and Materials 71–78 (2011) 4760–4764. [CrossRef]

- E.A. Deliyanni, G.Z. Kyzas, K.A. Matis, Various flotation techniques for metal ions removal, Journal of Molecular Liquids 225 (2017) 260–264. [CrossRef]

- den Boer, M. Sebastian, E. Kluczkiewicz, Skład sitowy i morfologiczny odpadów komunalnych. Jarocin, INSTYTUT INŻYNIERII OCHRONY ŚRODOWISKA, Wrocław, 2013. https://wcr-jarocin.pl/PLIKI/sortownia/zalacznik4.pdf?utm_source=chatgpt.com (accessed June 28, 2025).

- EUROSTAT, Waste statistics, (2024). https://ec.europa.eu/eurostat/statistics-explained/index.php?title=Waste_statistics (accessed June 29, 2025).

- US EPA, Sampling, (2020). https://www.epa.gov/hw-sw846/sampling (accessed June 28, 2025).

- N.E.M.I. NEMI, NEMI Method Summary - 6010 C, (2000). https://www.nemi.gov/methods/method_summary/4712/ (accessed June 28, 2025).

- 92. U.E.P.A. US EPA, Standard Operating Procedure 3051a Microwave Assisted Acid Digestion of Soil, (18AD).

- European Union Commission, Directive 2008/98/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council of 19 November 2008 on waste and repealing certain Directives (Text with EEA relevance), 2008. http://data.europa.eu/eli/dir/2008/98/oj/eng (accessed June 28, 2025).

- CEN, EN 12457-2:2002 - Characterisation of waste - Leaching - Compliance test for leaching of granular waste materials and sludges - Part 2: One stage batch test at a liquid to solid ratio of 10 l/kg for materials with particle size below 4 mm (without or with size reduction), iTeh Standards (n.d.). https://standards.iteh.ai/catalog/standards/cen/db6fbdf3-1de7-457c-a506-46c4898e3f09/en-12457-2-2002 (accessed June 28, 2025).

- BS, EN 12457-3:2002 - Characterisation of waste - Leaching - Compliance test for leaching of granular waste materials and sludges - Part 3: Two stage batch test at a liquid solid ratio of 2 l/kg and 8 l/kg for materials with a high solid content and with particle size below 4mm (without or with size reduction)., (2002).

- ANZECC, Waste classification guidelines. Part 1: classifying waste, (2008). https://support.esdat.net/Environmental%20Standards/australia/nsw_waste/091216classifywaste.pdf (accessed June 27, 2025).

- J. Costello, Waste - General Classifications and Principles, AUSTRALIAN ENVIRO SERVICES (2018). https://ausenvserv.wpengine.com/waste-general-classification-principles/ (accessed June 29, 2025).

- and C.C. Canada, Canadian Environmental Protection Act and hazardous waste and hazardous recyclable materials, (2009). https://www.canada.ca/en/environment-climate-change/services/canadian-environmental-protection-act-registry/general-information/fact-sheets/hazardous-waste-recyclable-materials.html (accessed June 29, 2025).

- L.S. Branch, Consolidated federal laws of Canada, Canadian Environmental Protection Act, 1999, (2025). https://laws-lois.justice.gc.ca/eng/acts/c-15.31/FullText.html (accessed June 29, 2025).

- C.N.E.M.C. CNEMC, Major Responsibilities, (1983). https://www.cnemc.cn/en/main_responsibilities/ (accessed June 29, 2025).

- I.O. for S. ISO, ISO 13909-4:2016, ISO (2016). https://www.iso.org/standard/63910.html (accessed June 29, 2025).

- K. Khodier, S.A. Viczek, A. Curtis, A. Aldrian, P. O’Leary, M. Lehner, R. Sarc, Sampling and analysis of coarsely shredded mixed commercial waste. Part I: procedure, particle size and sorting analysis, Int. J. Environ. Sci. Technol. 17 (2020) 959–972. [CrossRef]

- H. Møller, Sampling of heterogeneous bottom ash from municipal waste-incineration plants, Chemometrics and Intelligent Laboratory Systems 74 (2004) 171–176. [CrossRef]

- Y.-M. Li, C.-F. Wang, L.-J. Wang, T.-Y. Huang, G.-Z. Zhou, Removal of heavy metals in medical waste incineration fly ash by Na 2 EDTA combined with zero-valent iron and recycle of Na 2 EDTA: Acolumnar experiment study, Journal of the Air & Waste Management Association 70 (2020) 904–914. [CrossRef]

- Meer, R. Nazir, Removal techniques for heavy metals from fly ash, J Mater Cycles Waste Manag 20 (2018) 703–722. [CrossRef]

- R. Pöykiö, M. Mäkelä, G. Watkins, H. Nurmesniemi, O. Dahl, Heavy metals leaching in bottom ash and fly ash fractions from industrial-scale BFB-boiler for environmental risks assessment, Transactions of Nonferrous Metals Society of China 26 (2016) 256–264. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, M. Gao, M. Wang, C. Wu, Q. Wang, Y. Wang, Removal of heavy metals in municipal solid waste incineration fly ash using lactic acid fermentation broth, Environ Sci Pollut Res 28 (2021) 62716–62725. [CrossRef]

- M. Aucott, A. Namboodiripad, A. Caldarelli, K. Frank, H. Gross, Estimated Quantities and Trends of Cadmium, Lead, and Mercury in US Municipal Solid Waste Based on Analysis of Incinerator Ash, Water Air Soil Pollut 206 (2010) 349–355. [CrossRef]

- Stephenson, A. Heavy Metal Analysis of Municipal Solid Waste Incinerator Ash and Slag, Palma de Mallorca, 1996, Greenpeace Research Laboratory, University of Exeter, UK, 1996.

- M. Peña-Icart, M.E. Villanueva Tagle, C. Alonso-Hernández, J. Rodríguez Hernández, M. Behar, M.S. Pomares Alfonso, Comparative study of digestion methods EPA 3050B (HNO3–H2O2–HCl) and ISO 11466.3 (aqua regia) for Cu, Ni and Pb contamination assessment in marine sediments, Marine Environmental Research 72 (2011) 60–66. [CrossRef]

- K. Zhao, Y. Hu, Y. Wang, D. Chen, Y. Feng, Speciation and Risk Assessment of Heavy Metals in Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Fly Ash during Thermal Processing, Energy Fuels 33 (2019) 10066–10077. [CrossRef]

- H.Y. Zhang, G.X. Ma, G.L. Yuan, Content Analysis of Heavy Metals in Fly Ash from One Shanghai Municipal Solid Waste Incineration (MSWI) Plant, AMR 531 (2012) 272–275. [CrossRef]

- J. Gao, T. Wang, J. Zhao, X. Hu, C. Dong, An Experimental Study on the Melting Solidification of Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Fly Ash, Sustainability 13 (2021) 535. [CrossRef]

- J. Seniunaite, S. Vasarevicius, Leaching of Copper, Lead and Zinc from Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Bottom Ash, Energy Procedia 113 (2017) 442–449. [CrossRef]

- M. Pazalja, M. Salihović, J. Sulejmanović, A. Smajović, S. Begić, S. Špirtović-Halilović, F. Sher, Heavy metals content in ashes of wood pellets and the health risk assessment related to their presence in the environment, Sci Rep 11 (2021) 17952. [CrossRef]

- L. Kuboňová, Š. Langová, B. Nowak, F. Winter, Thermal and hydrometallurgical recovery methods of heavy metals from municipal solid waste fly ash, Waste Management 33 (2013) 2322–2327. [CrossRef]

- L.S. Morf, P.H. Brunner, S. Spaun, Effect of operating conditions and input variations on the partitioning of metals in a municipal solid waste incinerator, Waste Manag Res 18 (2000) 4–15. [CrossRef]

- A.J. Pedersen, L.M. Ottosen, A. Villumsen, Electrodialytic removal of heavy metals from different fly ashes: Influence of heavy metal speciation in the ashes, Journal of Hazardous Materials 100 (2003) 65–78. [CrossRef]

- C. Riber, G.S. Fredriksen, T.H. Christensen, Heavy metal content of combustible municipal solid waste in Denmark, Waste Manag Res 23 (2005) 126–132. [CrossRef]

- K. Lin, J.-H. Kuo, C.-L. Lin, Z.-S. Liu, J. Liu, Sequential extraction for heavy metal distribution of bottom ash from fluidized bed co-combusted phosphorus-rich sludge under the agglomeration/defluidization process, Waste Manag Res 38 (2020) 122–133. [CrossRef]

- Y. Tian, R. Wang, Z. Luo, R. Wang, F. Yang, Z. Wang, J. Shu, M. Chen, Heavy Metals Removing from Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Fly Ashes by Electric Field-Enhanced Washing, Materials 13 (2020) 793. [CrossRef]

- F.-H. Wang, F. Zhang, Y.-J. Chen, J. Gao, B. Zhao, A comparative study on the heavy metal solidification/stabilization performance of four chemical solidifying agents in municipal solid waste incineration fly ash, Journal of Hazardous Materials 300 (2015) 451–458. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, M. Gao, M. Wang, C. Wu, Q. Wang, Y. Wang, Removal of heavy metals in municipal solid waste incineration fly ash using lactic acid fermentation broth, Environ Sci Pollut Res 28 (2021) 62716–62725. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu, Y. Chen, Leaching heavy metals in municipal solid waste incinerator fly ash with chelator/biosurfactant mixed solution, Waste Manag Res 33 (2015) 652–661. [CrossRef]

- Y. Xu, Fu ,Yu, Xia ,Wei, Zhang ,Dan, An ,Da, G. and Qian, Municipal solid waste incineration (MSWI) fly ash washing pretreatment by biochemical effluent of landfill leachate: a potential substitute for water, Environmental Technology 39 (2018) 1949–1954. [CrossRef]

- J. Zhou, S. Wu, Y. Pan, L. Zhang, Z. Cao, X. Zhang, S. Yonemochi, S. Hosono, Y. Wang, K. Oh, G. Qian, Enrichment of heavy metals in fine particles of municipal solid waste incinerator (MSWI) fly ash and associated health risk, Waste Management 43 (2015) 239–246. [CrossRef]

- H. Zhang, P.-J. He, L.-M. Shao, Fate of heavy metals during municipal solid waste incineration in Shanghai, Journal of Hazardous Materials 156 (2008) 365–373. [CrossRef]

- H. Ji, W. Huang, Z. Xing, J. Zuo, Z. Wang, K. Yang, Experimental study on removing heavy metals from the municipal solid waste incineration fly ash with the modified electrokinetic remediation device, Sci Rep 9 (2019) 8271. [CrossRef]

- M.E. Bakkali, M. Bahri, S. Gmouh, H. Jaddi, M. Bakkali, A. Laglaoui, M.E. Mzibri, Characterization of bottom ash from two hospital waste incinerators in Rabat, Morocco, Waste Manag Res 31 (2013) 1228–1236. [CrossRef]

- H. Raclavská, A. Corsaro, A. Hlavsová, D. Juchelková, O. Zajonc, The effect of moisture on the release and enrichment of heavy metals during pyrolysis of municipal solid waste, Waste Manag Res 33 (2015) 267–274. [CrossRef]

- Ilyushechkin, A.; He, C.; Hla, S.S. Characteristics of inorganic matter from Australian municipal solid waste processed under combustion and gasification conditions, Waste Manag Res 39 (2021) 928–936. [CrossRef]

- S. Esakku, K. Palanivelu, K. Joseph, Assessment of Heavy Metals in a Municipal Solid Waste Dumpsite, in: Workshop, Chennai, India, 2003: pp. 139–145.

- Łukowski, S. Fractions of Zinc, Chromium and Cobalt in Municipal Solid Waste Incineration Bottom Ash, J. Ecol. Eng. 23 (2022) 12–16. [CrossRef]

- Gworek, A.; Dmuchowski, W.; Koda, E.; Marecka, M.; Baczewska, A.H.; Brągoszewska, P.; Sieczka, A.; Osiński, P. Impact of the Municipal Solid Waste Łubna Landfill on Environmental Pollution by Heavy Metals, Water 8 (2016) 470. [CrossRef]

- V. Funari, S.N.H. Bokhari, L. Vigliotti, T. Meisel, R. Braga, The rare earth elements in municipal solid waste incinerators ash and promising tools for their prospecting, Journal of Hazardous Materials 301 (2016) 471–479. [CrossRef]

- M.A. Al-Ghouti, M. Khan, M.S. Nasser, K.A. Saad, O.O.N.E. Heng, Physiochemical characterization and systematic investigation of metals extraction from fly and bottom ashes produced from municipal solid waste, PLOS ONE 15 (2020) e0239412. [CrossRef]

- K.-Y. Chiang, Y.-H. Hu, Water washing effects on metals emission reduction during municipal solid waste incinerator (MSWI) fly ash melting process, Waste Management 30 (2010) 831–838. [CrossRef]

- J. Latosińska, P. Czapik, The Ecological Risk Assessment and the Chemical Speciation of Heavy Metals in Ash after the Incineration of Municipal Sewage Sludge, Sustainability 12 (2020) 6517. [CrossRef]

- K.C. Pancholi, P.J. Singh, K. Bhattacharyya, M. Tiwari, S.K. Sahu, T. Vincent, D.V. Udupa, C.P. Kaushik, Elemental analysis of residual ash generated during plasma incineration of cellulosic, rubber and plastic waste, Waste Manag Res 40 (2022) 665–675. [CrossRef]

- E.A. Ubuoh, P.A. Ogwo, C.S. Kanu, Analyses of Metal Cations in the Bottom Ash of Hospital Incinerator and Open Waste Burning Dumpsite in Umuahia, Abia State, Nigeria, Journal of Sustainable Agriculture and the Environment 17 (2019) 264–285.

- B. Valizadeh, M.A. Abdoli, S. Dobaradaran, R. Mahmoudkhani, Y.A. Asl, Risk control of heavy metal in waste incinerator ash by available solidification scenarios in cement production based on waste flow analysis, Sci Rep 14 (2024) 6252. [CrossRef]

- Z. Xiao, X. Yuan, L. Leng, L. Jiang, X. Chen, W. Zhibin, P. Xin, Z. Jiachao, G. Zeng, Risk assessment of heavy metals from combustion of pelletized municipal sewage sludge, Environ Sci Pollut Res 23 (2016) 3934–3942. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, C. Zhao, Y. Rao, C. Yu, Z. Luo, H. Zhao, X. Wang, C. Wu, Q. Wang, Solidification/stabilization and risk assessment of heavy metals in municipal solid waste incineration fly ash: A review, Science of The Total Environment 892 (2023) 164451. [CrossRef]

- Z. Zhang, A. Li, X. Wang, L. Zhang, Stabilization/solidification of municipal solid waste incineration fly ash via co-sintering with waste-derived vitrified amorphous slag, Waste Management 56 (2016) 238–245. [CrossRef]

- J.-M. Martin, M. Meybeck, Elemental mass-balance of material carried by major world rivers, Marine Chemistry 7 (1979) 173–206. [CrossRef]

- L. Hakanson, An ecological risk index for aquatic pollution control.a sedimentological approach, Water Research 14 (1980) 975–1001. [CrossRef]

- Muller, INDEX OF GEOACCUMULATION IN SEDIMENTS OF THE RHINE RIVER, GeoJournal (1969). https://www.semanticscholar.org/paper/INDEX-OF-GEOACCUMULATION-IN-SEDIMENTS-OF-THE-RHINE-Muller/03688e2c0b4cabea9023db05e6b9a33281f0ea06 (accessed April 24, 2024).

- S. Yang, L. Sun, Y. Sun, K. Song, Q. Qin, Z. Zhu, Y. Xue, Towards an integrated health risk assessment framework of soil heavy metals pollution: Theoretical basis, conceptual model, and perspectives, Environmental Pollution 316 (2023) 120596. [CrossRef]

- X. Wang, Z. Dan, X. Cui, R. Zhang, S. Zhou, T. Wenga, B. Yan, G. Chen, Q. Zhang, L. Zhong, Contamination, ecological and health risks of trace elements in soil of landfill and geothermal sites in Tibet, Science of The Total Environment 715 (2020) 136639. [CrossRef]

- US EPA, Superfund Soil Screening Guidance, (2015). https://www.epa.gov/superfund/superfund-soil-screening-guidance (accessed June 29, 2025).

- S. Yang, J. Zhao, S.X. Chang, C. Collins, J. Xu, X. Liu, Status assessment and probabilistic health risk modeling of metals accumulation in agriculture soils across China: A synthesis, Environ Int 128 (2019) 165–174. [CrossRef]

- W. Wang, C. Chen, D. Liu, M. Wang, Q. Han, X. Zhang, X. Feng, A. Sun, P. Mao, Q. Xiong, C. Zhang, Health risk assessment of PM2.5 heavy metals in county units of northern China based on Monte Carlo simulation and APCS-MLR, Science of The Total Environment 843 (2022) 156777. [CrossRef]

| Concentration (mg/kg) | ||||

| Element | Bottom ash | Fly ash | Dry -/semi dry APC residues | Liquid APC residues |

| Zn | 610 – 7800 | 7000 – 70000 | 7000 – 20000 | 8100 – 53000 |

| As | 0.1 – 190 | 37 – 320 | 18 – 530 | 41 – 210 |

| V | 20 – 120 | 29 – 150 | 8 – 62 | 25 – 86 |

| Ca | 370 – 123000 | 74000 – 130000 | 110000 – 350000 | 87000 – 200000 |

| Si | 91000 – 308000 | 95000 – 210000 | 36000 – 120000 | 78000 |

| Cl | 800 – 4200 | 29000 – 210000 | 62000 – 380000 | 17000 – 51000 |

| Pb | 100 – 13700 | 5300 – 26000 | 2500 – 10000 | 3300 – 22000 |

| Sb | 10 – 43 | 260 – 1100 | 300 – 1100 | 80 – 200 |

| Fe | 4100 – 150000 | 12000 – 44000 | 2600 – 71000 | 20000 – 97000 |

| S | 1000 – 5000 | 11000 – 45000 | 1400 – 25000 | 2700 – 6000 |

| K | 750 – 16000 | 22000 – 62000 | 5900 – 40000 | 810 – 8600 |

| Ni | 7 – 4200 | 60 – 260 | 19 – 710 | 20 – 310 |

| Mn | 80 - 2400 | 800 - 1900 | 200 - 900 | 5000 - 12000 |

| Na | 2800 – 42000 | 15000 – 57000 | 7600 – 29000 | 720 – 3400 |

| Al | 22000 – 73000 | 49000 – 90000 | 83000 – 120000 | 21000 – 39000 |

| Ba | 400 – 3000 | 330 – 3100 | 51 – 14000 | 55 – 1600 |

| Cd | 0.3 – 70 | 50 – 450 | 140 – 300 | 150 – 1400 |

| Cu | 190 – 8200 | 600 – 3200 | 16 – 1700 | 440 – 2400 |

| Hg | 0.02 – 8.00 | 0.7 – 30 | 0.1 – 51 | 80 – 560 |

| Cr | 23 – 3200 | 140 – 1100 | 73 – 570 | 80 – 560 |

| Mo | 2 – 280 | 15 – 150 | 9 – 29 | 2 – 44 |

| Mg | 400 – 26000 | 11000 – 19000 | 5100 – 14000 | 19000 – 170000 |

| Components | Big Citya | Small Cityb | Rural area | Average |

| Organic waste (%) | 34.20 | 42 | 35.60 | 37.27 |

| Paper and cardboard (%) | 19.10 | 9.7 | 5 | 11.27 |

| Wood (%) | 0.20 | 0.30 | 0.70 | 0.40 |

| Multilayer packages (%) | 2.5 | 2.6 | 1.3 | 2.13 |

| Plastics (%) | 15.10 | 11 | 10.20 | 12.13 |

| Glass (%) | 10 | 10.20 | 10 | 10.07 |

| Metals (%) | 2.6 | 1.5 | 2.40 | 2.17 |

| Textiles (%) | 2.3 | 4 | 2.1 | 2.80 |

| Hazardous (%) | 0.80 | 0.6 | 0.8 | 0.73 |

| Minerals (%) | 3.2 | 2.8 | 6 | 4.00 |

| Bulky (%) | 2.5 | 4 | 4.10 | 3.53 |

| <10 mm fraction (%) | 4.2 | 6.8 | 16.90 | 9.30 |

| Otherc (%) | 3.2 | 4.5 | 4.9 | 4.20 |

| Region | Key Guidelines | Sampling Method | Sample Size | Frequency | Notes |

| EPA (USA) | 40 CFR 258, 261 | Composite, Random | 5-10 kg | Batch-by-batch | Leachate and trace metals |

| EU | EN 12457, Commission Decision | Composite, Automatic | 5 kg | Batch-by-batch | Focus on leachate testing |

| Australia & New Zealand | ANZECC Guidelines | Composite, Random | 5-10 kg | Batch-by-batch | Focus on contaminants |

| Canada | CEPA Guidelines | Composite, Random | 5-10 kg | Quarterly/Annually | Preservation at 4°C |

| China/Asia | GB 3433-2008 | Composite, Automated | 5-10 kg | Quarterly/Annually | Focus on industrial operations |

| Metals | Matrix/samples | Acid combination | Method description | Source | Ref | comment |

| Cd, Cr, Pb, Cu, Zn, and Ni | MSW Fly ash | HNO3/H2O2/HCl | Digestion on hot plate Temp. not stated |

EPA 3050B | [110,111] | May be suitable |

| Ni, Zn, Cd, Pb and Cu | MSW Fly ash | HNO3/HCl | Not stated | [112] | May be suitable | |

| Pb, Cd, Zn, Cu | MSW Fly ash | HCl-HNO3-HF-HClO4 | 0.1g sample used | Chinese standard GB17141–1997 | [113] | May not be suitable due to the presence of HF |

| Cu, Pb and Zn | MSW Bottom ash | HNO3 | Pre-treatment before determination | ISO 15586:2003 | [114] | May be suitable |

| f Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Fe, Mn, Ni, Pb, and Zn | Wood pellet ashes | 65% HNO3 | Sample + 25 mL of 65% HNO3 in PTFE vessels. Close vessel after NOs + react for 14 h at 80 °C, cool to 20 or 25 oC | [115] | May be suitbale | |

| Hg, Pb and Cd | MSW ash | HNO3/HCl | AAS for Hg, ICP-MS for Pb and Cd | USEPA SW-846 Method 7471A; USEPA Method 3051/6020 | [108] | May be suitable |

| Mn, Cr, Zn, Cu, Pb, Ni, Co, Cd | MSW ash and slag | HNO3/HCl | MA-digestion ICP-AES | [109] | Suitable | |

|

M1: Al, Ca, Cu, Fe, K, Mg, Mn, Na, P, Pb, S, Sb, Si, Sn, Zn M2: Ag, As, Cd, Co, Cr, Mo, Ni, Se, Tl, U, V |

MSW fly ash | HNO3/HCl | MA-digestion; ICP-OES for M1 and ICP-QMS for M2 |

[56] | Suitable | |

| Zn, Mn, Ni, Co, Fe, Cr, Al, Cu, and Pb | MSW ash and fluidized beads | HNO3/HCl | MIP-OES | [15] | Suitable |

| Country/location | Metals investigated | Analytical technique used | Reference |

| Switzerland | Pb, Cu, Cd, Ca, Al, Fe, Sb and Zn | XRF, ICP-OES, ICP-MS | [42,43] |

| Austria | Zn, Cu, Cd, and Pb | ICP-OES | [116,117] |

| Denmark |

Zn, Cu, Cd, Ni, As, Hg and Pb Cd, Pb, Zn, Cu, Cr |

FAAS |

[55,118,119] |

| Greece | Ba, Mn, Pb, Cr, Cd, Cu, Zn, Ni, Na, Ca, Mg, Fe, K, Al | ICP-OES | [41] |

| China | Pb, Cd, Zn, Cu, Mn, Cd, Pb, Cr As, Cr, Pb, Zn Cd, Pb, Zn, Cu, Cr, Ni Cu, Zn, Ni Ca, K, Na, Al, Zn, Pb, Cr, Cu Cu, Zn Pb, Cu, Zn, Cd, Cr, Ni, As, Ba Zn, Cu, Ni, Pb, Cr, Cd Cu, Cd, Pb, Zn, Cr Cu, Zn, Cd, Cr, Hg, Ni, As, Pb Ca, Pb, Zn, Cu, Ni, Cd, Cr Zn, Cu, Pb, Cd, Cr, Fe, Mn Cd, Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb, Zn, Ca, Na, K, Pb, Zn, Cd, Cr, Cu, Mn, Cu, Pb, Zn, Cd, Ni |

ICP-MS FAAS ICP-OES ICP-MS ICP-OES XRF FAAS ICP-OES XRF ICP-MS AAS, XRF ICP-OES ICP-MS ASS XRF ICP-M |

[46] [120] [55] [79] [86] [50] [121] [122] [123] [124] [125] [126] [127] [128] [81] |

| Morocco | As, Cd, Cr, Ni, Pb, Sn, Zn | XRF | [129] |

| Czech Republic | As, Cd, Cr, Hg, Ni, Pb, V | ICP-OES | [130] |

| Australia | As, Se, Hg, Cr, Cu, Ni, Zn, Cd, Ag, Co, Sn | ICP-OES, ICP-MS | [131] |

| India | As, Hg, Cr, Cd, Cu, Pb, Ni, Zn | F-AAS (hydride generation for As and Hg by cold vapour techniques, respectively | [132] |

| Poland (Biatystock) | Zn, Cr, Co Mn, Cu, Mo, Zn, Cd, Ti, Cr, Co, Ni, As, Sn, Pb, Sb, V Cd, Pb, Cr, Cu, Zn |

F-AAS ICP-MS ICP-OES |

[133] [37] [134] |

| Italy | Mn, Fe, Cu, Ba, Sn, Zn Pb, Ti | ICP-MS | [135] |

| Japan | Cd, Cu, Zn, Pb, Cr | ICP-OES | [57] |

| Qatar | Al, As, Ba, Ca, Cd, Co, Cr, Cu, Fe, K, Mg, Mn, Na, Ni, Pb, Zn, Mg | ICP-OES | [136] |

| Austria | Cd, Cr, Cu, Ni, Pb, Zn, Al, Ca, Fe, K, Mg, Na | ICP-OES | [116] |

| Taiwan | Cu, Cr, Zn, Al, Na, K, Ca, Mg, Pb, Cd | ICP-OES | [137] |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).