Submitted:

28 February 2025

Posted:

03 March 2025

You are already at the latest version

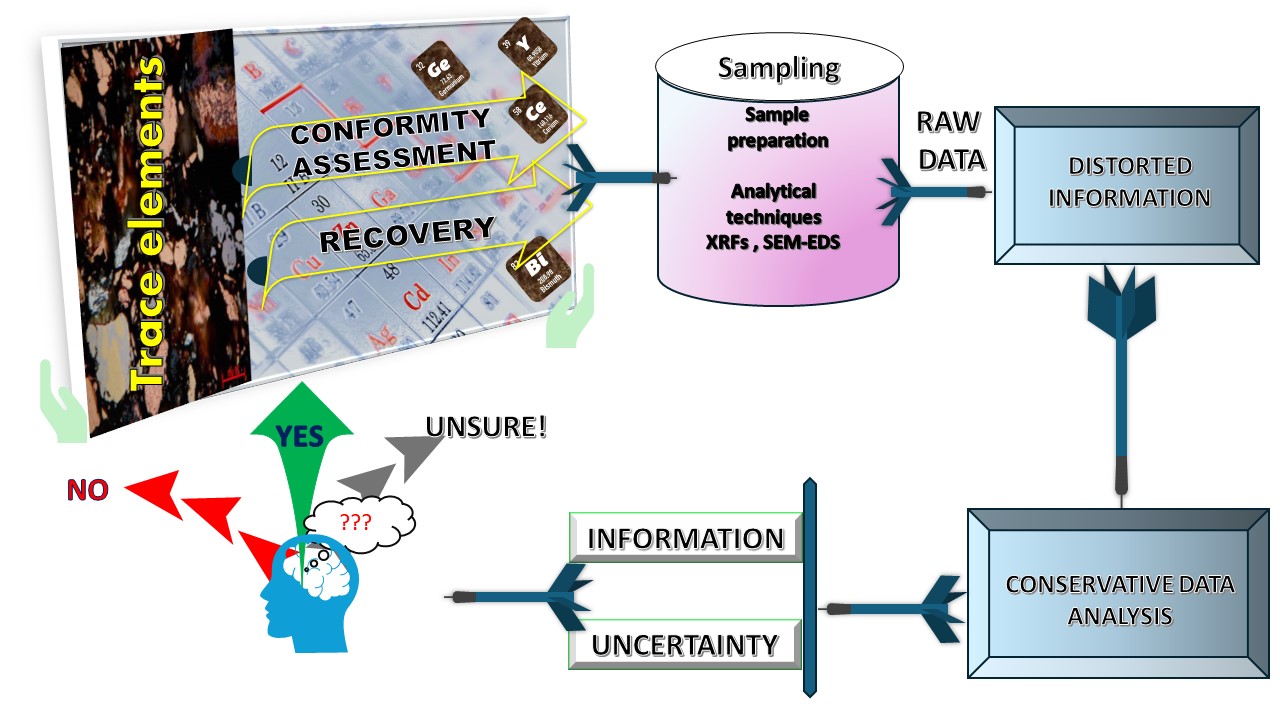

Abstract

Keywords:

1. Introduction

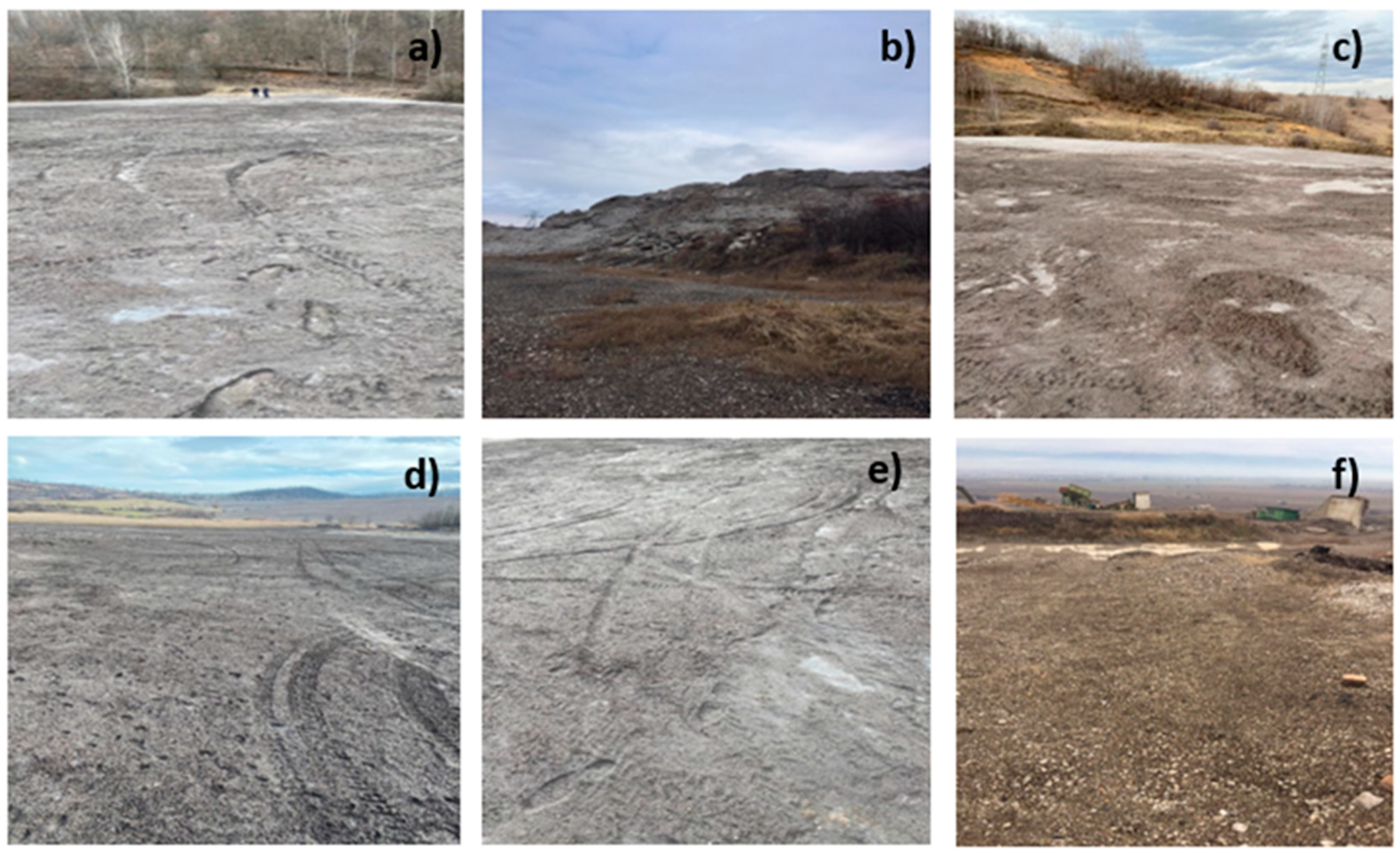

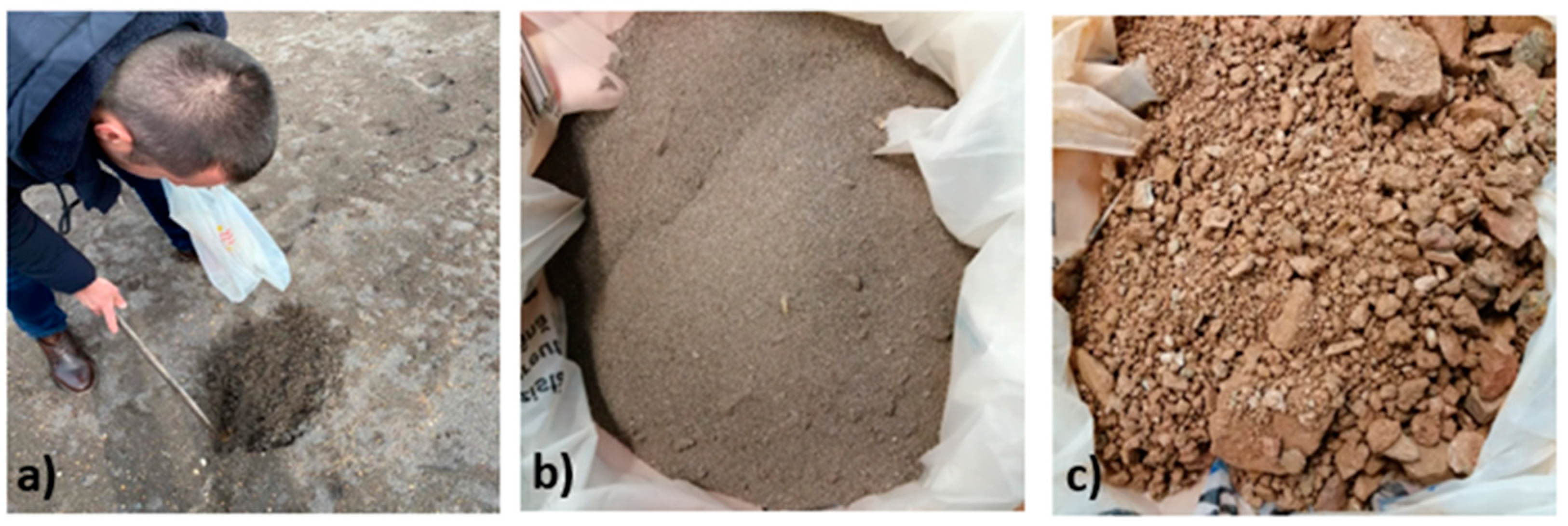

2. Materials and Methods

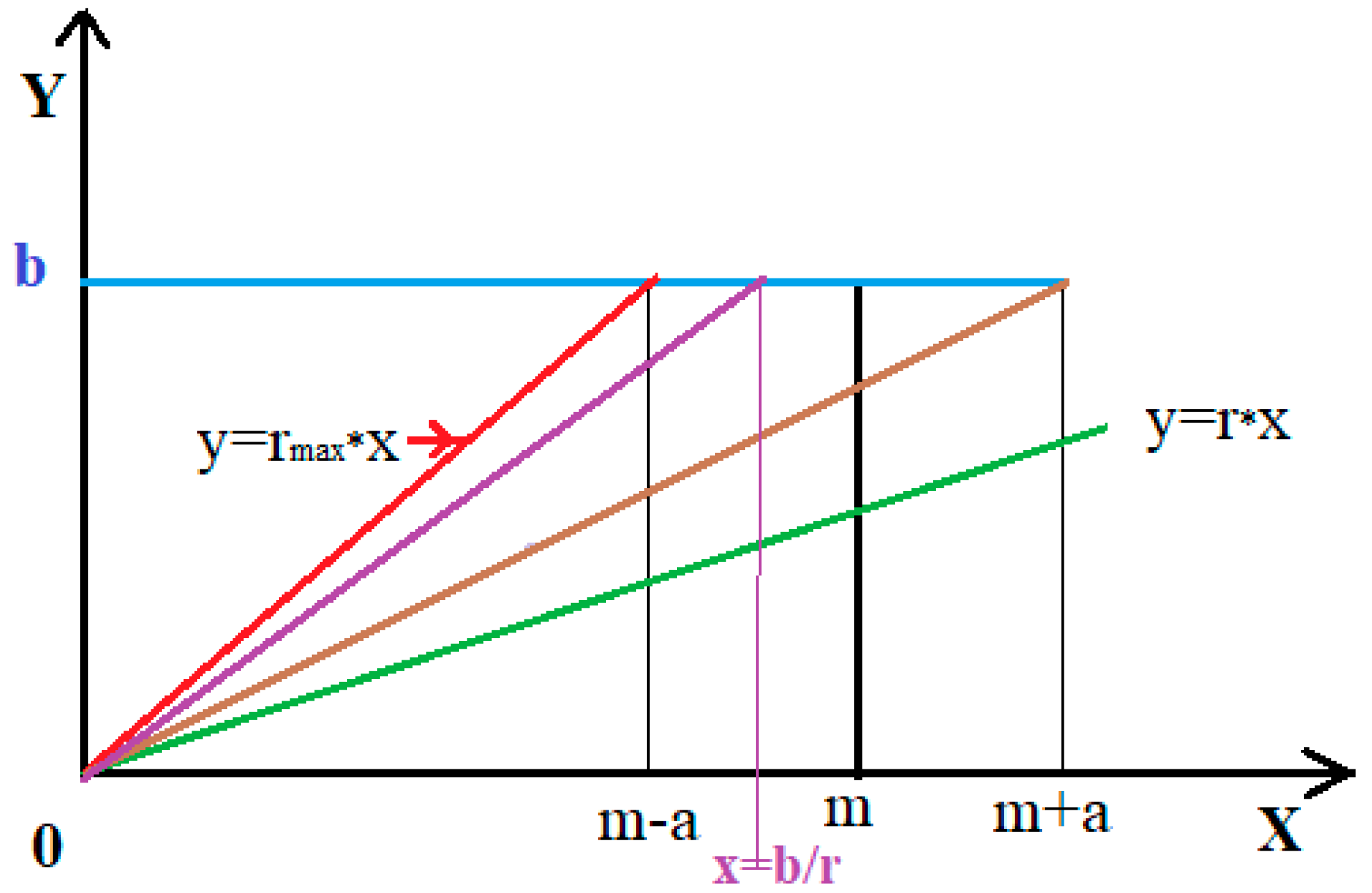

2.1. Derivation of the pdf Assigned to True Analyte Concentration into the Aliquot

2.2. Derivation of the pdf Assigned to True Analyte Concentration into the Aliquot

2.3. Derivation of the Analyte Concentration with Laboratory Constrains

2.4. Sample preparation and characterization

3. Results and Discussion

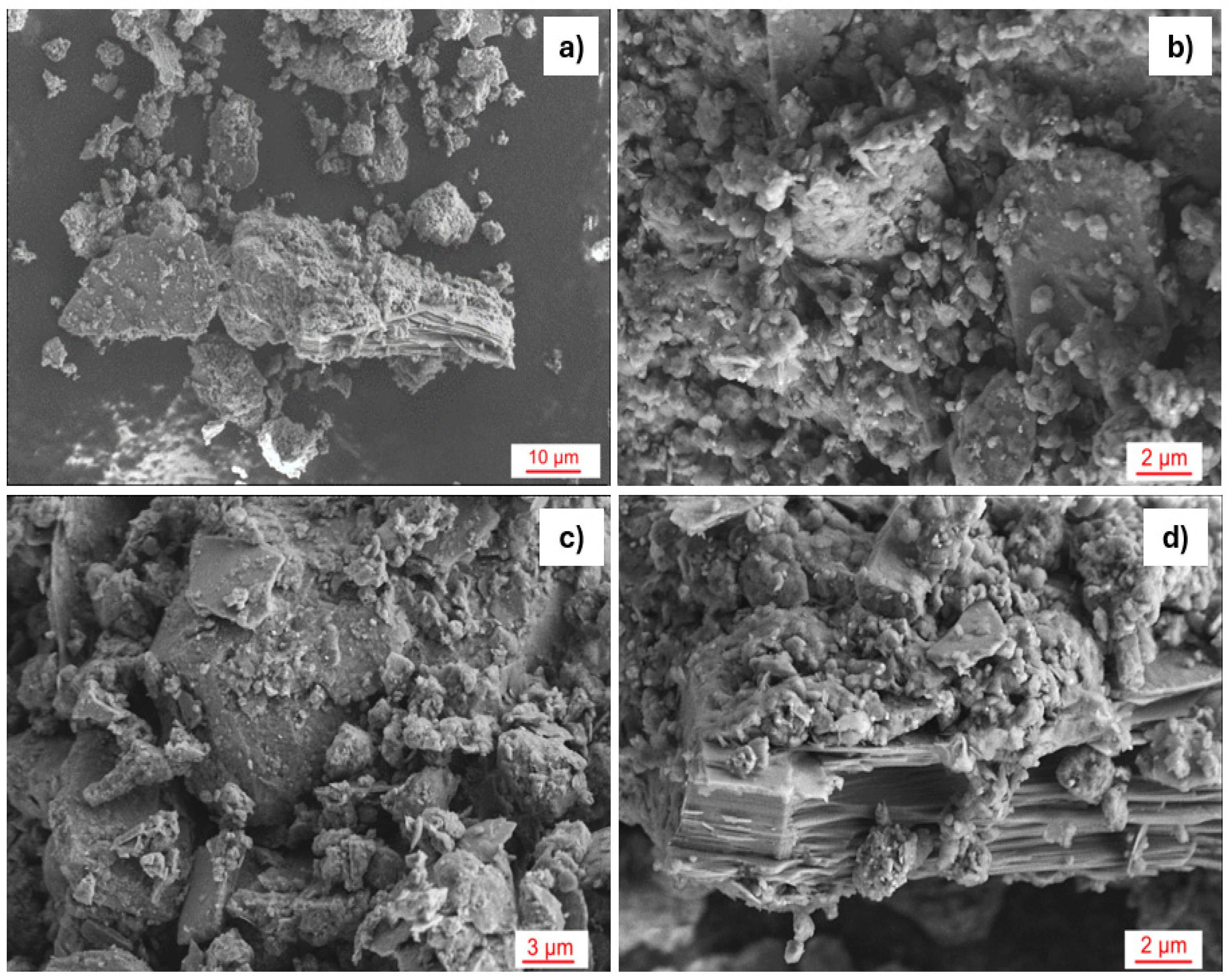

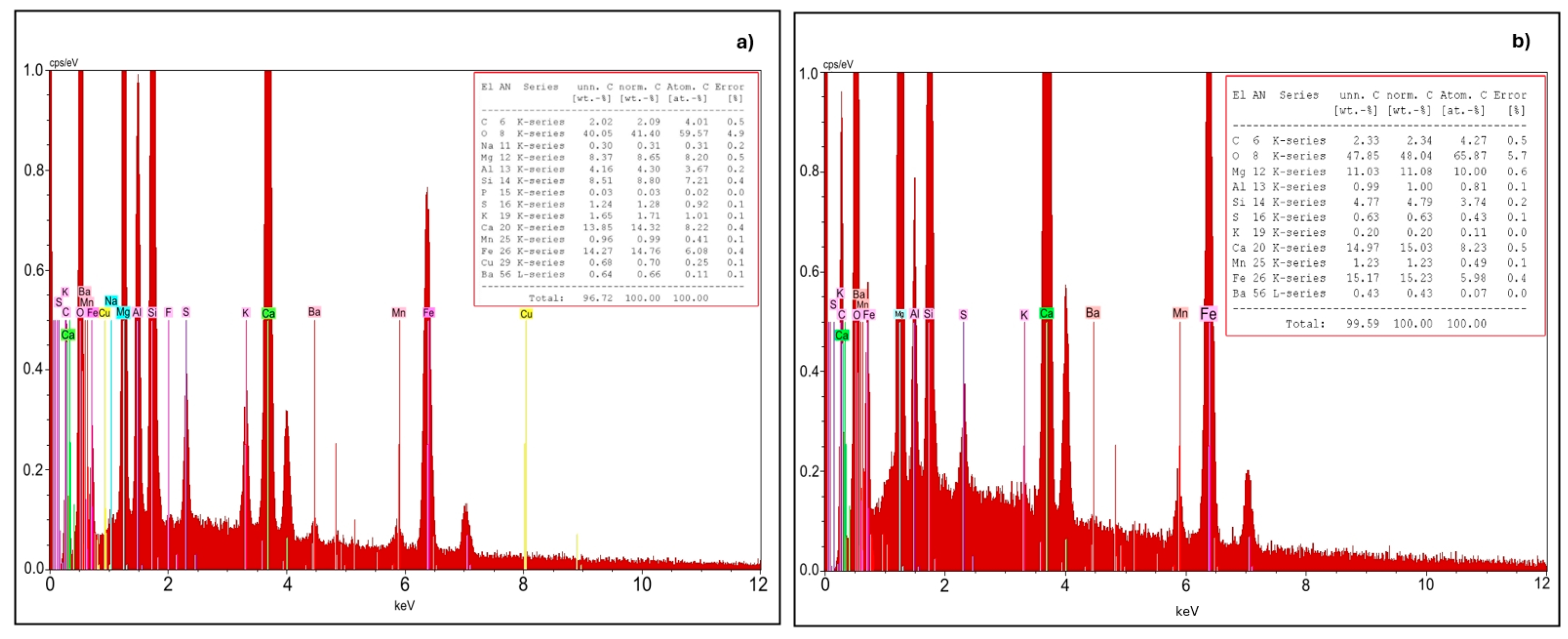

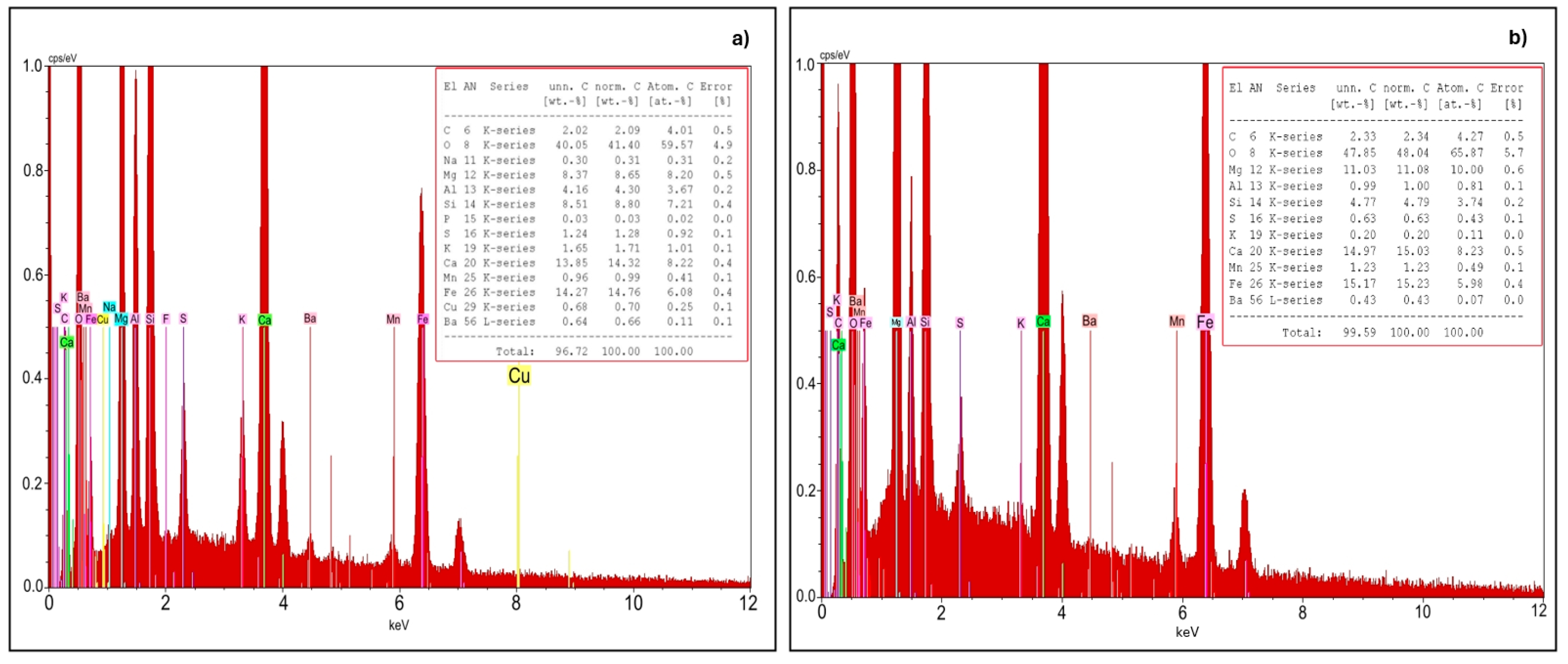

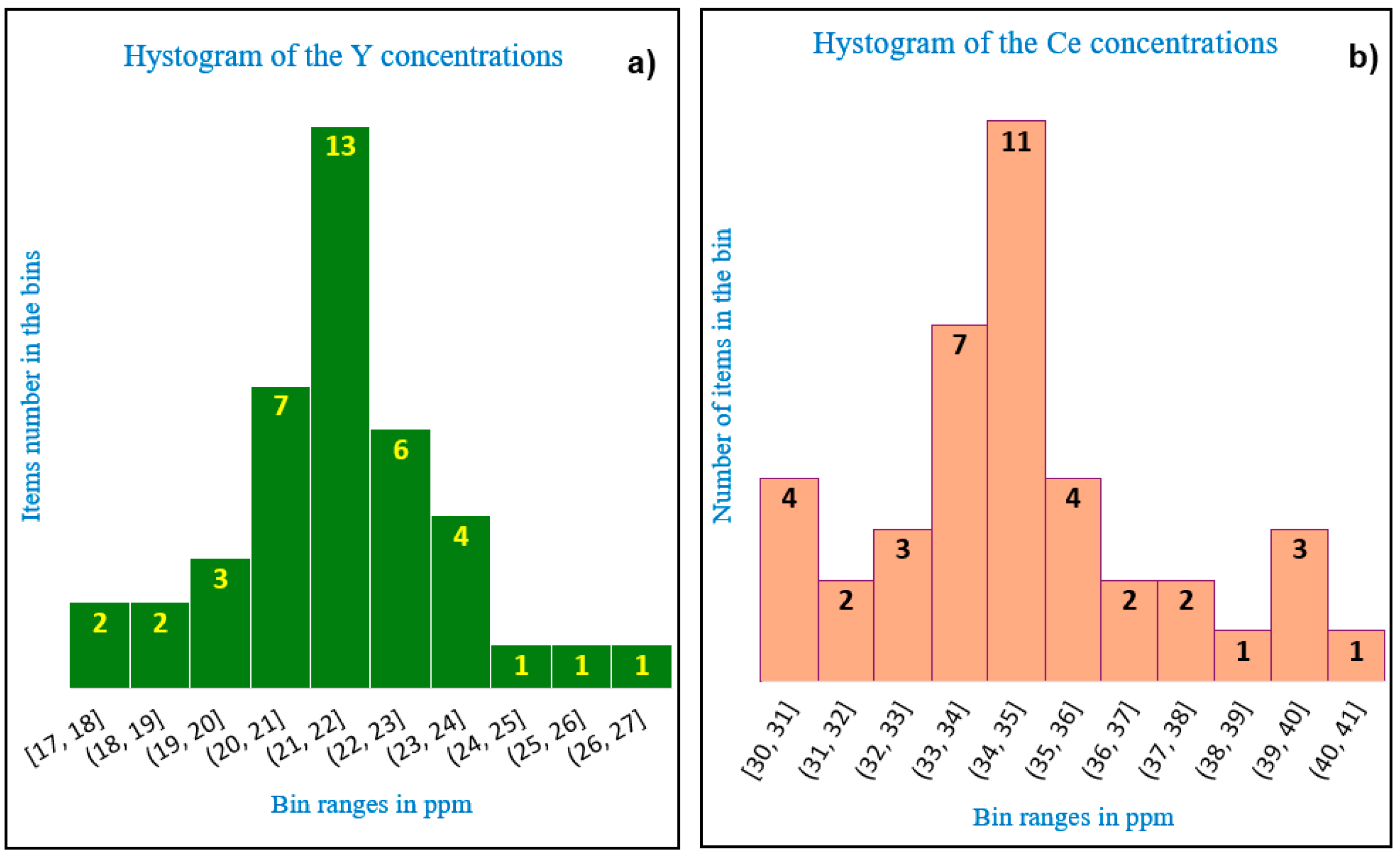

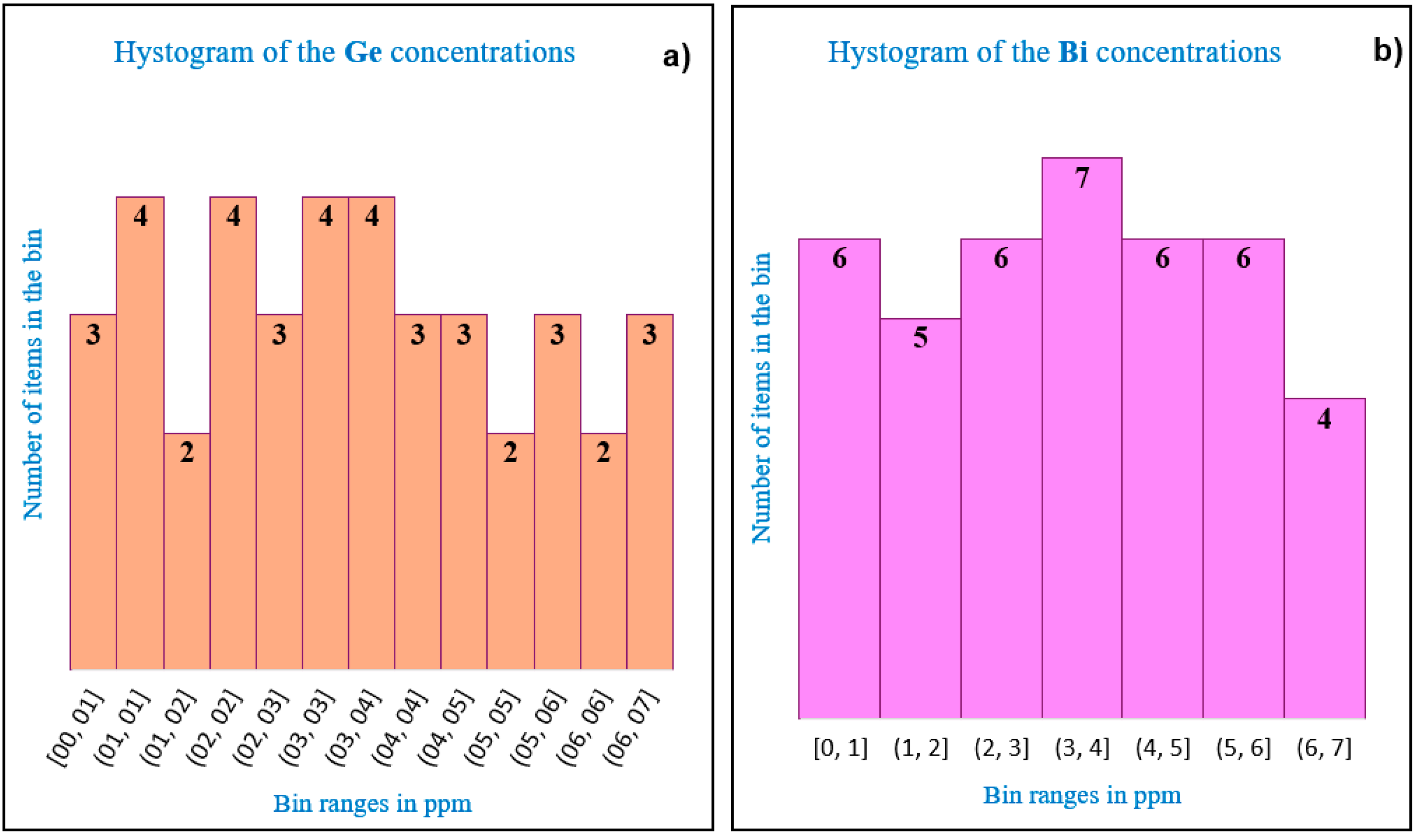

3.1. Assessment of the Tailings Heterogeneity at Micro-Scale

4. Discussion

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Institutional Review Board Statement

Informed Consent Statement

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- GACERE (2024). Circular Economy and Solid Waste - Working Paper. Available online: https://www.unido.org/sites/default/files/unido-publications/2024-06/orking%20Paper_Circular%20Economy%20and%20Solid%20Waste.pdf (accessed on 20 January 2024).

- European Commission DG ENV. E3 Project ENV.E.3/ETU/2000/0058 Heavy Metals in Waste Final Report February 2002, file:///D:/2025/heavy_metalsreport.pdf.

- Document number C(2009) 3013), (2009/360/EC), COMMISSION DECISION, 30 April 2009, completing the technical requirements for waste characterisation laid down by Directive 2006/21/EC of the European Parliament and of the Council on the management of waste from extractive industries. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/egal-content/EN/TXT/?uri=CELEX:32009D0360.

- Onwualu-John, J.N.; Uzoegbu, M.U. Physicochemical Characteristics and Heavy Metals Level in Groundwater and Leachate around Solid Waste Dumpsite at Mbodo, Rivers State Nigeria. J. Appl. Sci. Environ. Manag. 2022, 26, 2107–2112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simon, F.G.; Scholz, P. Assessment of the Long-Term Leaching Behavior of Incineration Bottom Ash: A Study of Two Waste Incinerators in Germany. Appl. Sci. 2023, 13, 13228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Das, S.; Galgo, S.J.; Aam, M.A.; Lee, J.G.; Hwang, H.Y.; Lee, C.H.; Kim, P.J. Recycling of ferrous slag in agriculture: Potentials and challenges. Crit. Rev. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2020, 52, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- United States Department of Agriculture Natural Resources Conservation Service Soil Quality Institute 411 S. Donahue Dr. Auburn, AL 36832 334-844-4741 X-177 Urban Technical Note No. 3 September, 2000. Available online: https://semspub.epa.gov/work/03/2227185.pdf.

- REGULATION (EU) 2024/1252 OF THE EUROPEAN PARLIAMENT AND OF THE COUNCIL of 11 April 2024 establishing a framework for ensuring a secure and sustainable supply of critical raw materials and amending Regulations (EU) No 168/2013, (EU) 2018/858, (EU) 2018/1724 and (EU) 2019/1020. Available online: https://eur-lex.europa.eu/eli/reg/2024/1252/oj (accessed on 8 July 2024).

- Dino, G.A.; Rossetti, P.; Perotti, L.; Alberto, W.; Sarkka, H.; Coulon, F.; Wagland, S.; Griffiths, Z.; Rodeghiero, F. Landfill mining from extractive waste facilities: The importance of a correct site characterisation and evaluation of the potentialities. A case study from Italy. Resour. Policy 2018, 59, 50–61. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- AMC Technical Brief, The edge of reason: Reporting and inference near the detection limit Analytical Methods Committee AMCTB No. 92. https://doi.org/10.1039/C9AY90188D. Anal. Methods 2020, 12, 401–403. [CrossRef]

- Thompson, M.; Ellison, S.L.R. Towards an uncertainty paradigm of detection capability. Anal. Methods 2013, 5, 5857–5861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia, Abundance of elements in Earth's crust. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Abundance_of_elements_in_Earth%27s_crust (accessed on 30 March 2024).

- Baldassarre, G.; Fiorucci, A.; Marini, P. Recovery of Critical Raw Materials from Abandoned Mine Wastes: Some Potential Case Studies in Northwest Italy. Mater. Proc. 2023, 15, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pencea, I.; Turcu, R.N.; Popescu-Arges, A.C.; Timis, A.L.; Priceputu, A.; Ungureanu, C.; Matei, E.; Nedelcu, L.; Petrescu, M.I.; Niculescu, F. An improved balanced replicated sampling design for preliminary screening of the tailings ponds aiming at zero-waste valorization. A Romanian case study. J. Environ. Manag. 2023, 331, 117260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pitard, F.F. Theoretical, practical, and economic difficulties in sampling for trace constituents. J. S. Afr. Inst. Min. Metall. 2010, 110, 313–321. [Google Scholar]

- Araya, N.; Ramirez, Y.; Kraslawski, A.; Cisternas, L.A. Feasibility of re-processing mine tailings to obtain critical raw materials using real options analysis. J. Environ. Manag. 2021, 284, 112060. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sarker, S.K.; Haque, N.; Bhuiyan, M.; Bruckard, W.; Pramanik, B.K. Recovery of strategically important critical minerals from mine tailings. J. Environ. Chem. Eng. 2022, 10, 107622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pitard, F.R. Pierre Gy’s Sampling Theory and Sampling Practice: Heterogeneity, Sampling Correctness, and Statistical Process Control, 2nd ed.; CRC Press: Boca Raton, FL, USA, 1993. [Google Scholar]

- Minkkinen, P.O.; Esbensen, K.H. Sampling of particulate materials with significant spatial heterogeneity - Theoretical modification of grouping and segregation factors involved with correct sampling errors: Fundamental Sampling Error and Grouping and Segregation Error. Anal. Chim. Acta 2019, 1049, 47–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennebert, P. The sorting of waste for a circular economy: Sampling when (very) few particles have (very) high concentrations of contaminant or valuable element, 2019, 17th International waste management and landfill symposium, Santa Margherita di Pula (CA), Italy in Proceedings SARDINIA2019, 2019 CISA Publisher. Available online: www.cisapublisher.com.

- Hennebert, P.; Beggio, G. Sampling representative waste samples based on particles size. Detritus 2022, 18, 3–11. [Google Scholar]

- Hennebert, P.; Beggio, G. Sampling and sub-sampling of granular waste: Size of a representative sample in terms of number of particles. Detritus 2021, 17, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ladenberger, A.; Arvanitidis, N.; Jonsson, E.; Arvidsson, R.; Casanovas, S.; Lauri, L. Identification and quantification of secondary CRM resources in Europe, SCRREEN - Contract Number: 730227. Available online: https://scrreen.eu/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/SCRREEN-D3.2-Identification-and-quantification-of-secondary-CRM-resources-in-Europe.pdf (accessed on 19 February 2024).

- Gerlach, R.W.; Nocerino, J.M. Guidance for Obtaining Representative Laboratory Analytical Subsamples from Particulate Laboratory Samples. EPA/600/R-03/027 November 2003, ID: 75176. Available online: https://www.researchgate.net/publication/242671015_Guidance_for_Obtaining_Representative_Laboratory_Analytical_Subsamples_from_Particulate_Laboratory_Samples (accessed on 20 December 2024).

- ISO/IEC 98-3:2008; Uncertainty of measurement —Part 3: Guide to the expression of uncertainty in measurement (GUM:1995). ed. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2008.

- Coskun, A.; Oosterhuis, W. Statistical distributions commonly used in measurement uncertainty in laboratory medicine. Biochem. Med. 2020, 30, 010101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Terzano, R.; Denecke, M.; Falkenberg, G.; Miller, B.; Paterson, D.; Janssens, K. Recent advances in analysis of trace elements in environmental samples by X-ray based techniques (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2019, 91, 1029–1063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Allegretta, I.; Bilo, F.; Marguí, E.; Pashkova, G.V.; Terzano, R. Development and Application of X-rays. Met. Anal. Soil Plants. Agron. 2023, 13, 114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 13528:2015; Statistical Methods for Use in Proficiency Testing by Interlaboratory Comparison. 2nd ed. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2015; 10–12, 32–33,44–51, 52–62.

- ISO/IEC 17025:2017; General requirements for the competence of testing and calibration laboratories, ed. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2017.

- Pencea, I. Multiconvolutional Approach to Treat the Main Probability Distribution Functions Used to Assess the Uncertainties of Metallurgical Tests, chapter 6 in Metallurgy - Advances in Materials and Processes. InTech, 2012; p. 186. ISBN 978-953-51-0736-1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kadachia, A.N.; Al-Eshaikhb, M.A. Limits of detection in XRF spectroscopy. X-Ray Spectrom. 2012, 41, 350–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badla, C.; Wewers, F. Optimization of X-ray Fluorescence Calibration through the Introduction of Synthetic Standards for the Determination of Mineral Sands Oxides. S. Afr. J. Chem. 2020, 73, 92–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wikipedia, Truncated normal distribution. Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Truncated_normal_distribution (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Wikipedia, Characteristic function (probability theory). Available online: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Characteristic_function_(probability_theory) (accessed on 25 March 2024).

- Moran-Palacios, H.; Ortega-Fernandez, F.; Lopez-Castaño, R.; Alvarez-Cabal, J.V. The Potential of Iron Ore Tailings as Secondary Deposits of Rare Earths. Appl. Sci. 2019, 9, 2913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blannin, R.; Frenzel, M.; Tolosana-Delgado, R.; Gutzmer, J. Towards a sampling protocol for the resource assessment of critical raw materials in tailings storage facilities. J. Geochem. Explor. 2022, 236, 106974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- ISO 5725-5:1998; Accuracy (Trueness and Precision) of Measurement Methods and Results—Part 5: Alternative Methods for the Determination of the Precision of a Standard Measurement Method. 1st ed. ISO: Geneva, Switzerland, 1998; pp. 35–36.

| Description Method - TurboQuant-Pelette | |||||

| Aliquot no. 1 | Aliquot no. 22 | ||||

| Z | Symbol | Concentration [%wt.] |

*SD [%wt.] |

Concentration [%wt.] |

SD [%wt.] |

| 11 | Na2O | 0.804056 | 0.024000 | 1.794032 | 0.023658 |

| 12 | MgO | 1.344708 | 0.009000 | 1.358216 | 0.007707 |

| 13 | Al2O3 | 9.817325 | 0.010000 | 9.686015 | 0.009131 |

| 14 | SiO2 | 52.68028 | 0.0300 | 49.572850 | 0.032995 |

| 15 | P2O5 | 0.642814 | 0.001700 | 0.642621 | 0.001823 |

| 16 | SO3 | 2.324803 | 0.000900 | 3.449874 | 0.000920 |

| 17 | Cl | 0.014883 | 0.000070 | 0.014575 | 7.19E-05 |

| 19 | K2O | 2.030205 | 0.006000 | 2.188351 | 0.005578 |

| 20 | CaO | 11.38931 | 0.00900 | 14.88444 | 0.008529 |

| 22 | TiO2 | 0.855457 | 0.004500 | 0.812547 | 0.004797 |

| 23 | V2O5 | 0.01414 | 0.00130 | 0.013785 | 0.001213 |

| 24 | Cr2O3 | 0.025996 | 0.000460 | 0.024948 | 0.000407 |

| 25 | MnO | 0.11524 | 0.00070 | 0.113313 | 0.000781 |

| 26 | Fe2O3 | 15.62105 | 0.00400 | 13.89942 | 0.003672 |

| 27 | CoO | 0.001607 | 0.000230 | 0.001600 | 0.000234 |

| 28 | NiO | 0.006846 | 0.000100 | 0.006134 | 0.00011 |

| 29 | CuO | 0.025287 | 0.000150 | 0.026669 | 0.000158 |

| 30 | ZnO | 0.125794 | 0.000300 | 0.120923 | 0.000281 |

| 31 | Ga | 0.001243 | 0.000040 | 0.001316 | 3.63E-05 |

| 32 | Ge | 0.000461 | 0.000040 | 0.000172 | 0.000040 |

| 33 | As2O3 | 0.000866 | 0.000090 | 0.000789 | 9.10E-05 |

| 34 | Se | 5.06E-05 | 0.00002 | 0.00005 | 2.05E-05 |

| 35 | Br | 0.001244 | 0.000020 | 0.00134 | 2.03E-05 |

| 37 | Rb2O | 0.00869 | 0.00003 | 0.007784 | 3.21E-05 |

| 38 | SrO | 0.016866 | 0.000040 | 0.018128 | 3.56E-05 |

| 39 | Y | 0.002172 | 0.000030 | 0.001990 | 3. 20E-05 |

| 40 | ZrO2 | 0.029554 | 0.000240 | 0.028678 | 0.000240 |

| 41 | Nb2O5 | 0.001186 | 0.000070 | 0.00122 | 6.65E-05 |

| 42 | Mo | 0.000831 | 0.000060 | 0.00081 | 6.38E-05 |

| 47 | Ag | 0.000535 | 0.000160 | 0.000530 | 0.000152 |

| 48 | Cd | 0.000398 | 0.000060 | 0.000410 | 5.50E-05 |

| 50 | SnO2 | 0.002718 | 0.000130 | 0.002817 | 0.000137 |

| 51 | Sb2O5 | 0.000882 | 0.000110 | 0.000900 | 0.000118 |

| 52 | Te | < 0.00030 | - | < 0.00030 | - |

| 53 | I | < 0.00030 | - | < 0.00030 | - |

| 55 | Cs | 0.000953 | 0.000590 | 0.000950 | 0.000532 |

| 56 | Ba | 0.069997 | 0.001000 | 0.062817 | 0.000879 |

| 57 | La | < 0.00020 | - | < 0.00020 | - |

| 58 | Ce | 0.003449 | 0.000760 | 0.003740 | 0.000840 |

| 72 | Hf | 0.00055 | 0.00007 | 0.000531 | 6.85E-05 |

| 73 | Ta2O5 | < 0.00063 | - | < 0.00063 | - |

| 74 | WO3 | 0.001896 | 0.000140 | 0.001834 | 0.000129 |

| 79 | Au | 0.000131 | 0.000060 | - | - |

| 80 | Hg | < 0.00010 | - | < 0.00010 | - |

| 81 | Tl | 0.000117 | 0.000020 | 0.00012 | 2.16E-05 |

| 82 | PbO | 0.021109 | 0.000100 | 0.0233090 | 0.000108 |

| 83 | Bi | 0.000172 | 0.000060 | < 0.00010 | - |

| 90 | Th | 0.000883 | 0.000040 | 0.000888 | 3.81E-05 |

| 92 | U | 6.94E-05 | 0.00001 | 6.51E-05 | 8.92E-06 |

| Total | 99.21829 | 98.7713 | |||

| Sample No |

Y | Ce | Ge | Bi | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| C | SD | C | SD | C | SD | C | SD | |

| 1 | 21.70 | 0.30 | 34.50 | 7.60 | 4.60 | 0.41 | 1.70 | 0.70 |

| 2 | 21.50 | 0.30 | 32.10 | 8.00 | 5.10 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 3 | 26.20 | 0.30 | 30.00 | 8.00 | 2.60 | 0.40 | 2.60 | 0.70 |

| 4 | 25.40 | 0.30 | 30.00 | 7.00 | 2.20 | 0.40 | 3.10 | 0.60 |

| 5 | 21.55 | 0.30 | 34.39 | 7.60 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 4.40 | 0.60 |

| 6 | 21.88 | 0.30 | 33.98 | 7.53 | 0.80 | 0.41 | 4.05 | 0.60 |

| 7 | 21.32 | 0.30 | 33.30 | 7.51 | 1.70 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 8 | 22.30 | 0.30 | 35.00 | 7.67 | 1.80 | 0.40 | 1.80 | 0.60 |

| 9 | 21.55 | 0.30 | 34.39 | 7.60 | 3.55 | 0.40 | 3.21 | 0.60 |

| 10 | 21.88 | 0.30 | 33.30 | 7.51 | 3.20 | 0.40 | 4.22 | 0.60 |

| 11 | 21.32 | 0.30 | 33.98 | 7.53 | 3.60 | 0.40 | 5.40 | 0.60 |

| 12 | 22.30 | 0.30 | 32.50 | 7.67 | 2.63 | 0.40 | 5.60 | 0.60 |

| 13 | 21.00 | 0.30 | 35.00 | 8.60 | 1.30 | 0.40 | 3.80 | 0.60 |

| 14 | 21.88 | 0.30 | 33.98 | 7.53 | 4.10 | 0.40 | 3.20 | 0.60 |

| 15 | 21.00 | 0.30 | 32.50 | 8.60 | 3.20 | 0.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 16 | 21.00 | 0.30 | 35.00 | 8.30 | 2.12 | 0.40 | 4.50 | 0.60 |

| 17 | 21.18 | 0.33 | 34.50 | 8.60 | 4.10 | 0.42 | 3.40 | 0.60 |

| 18 | 21.18 | 0.31 | 34.50 | 8.05 | 3.35 | 0.45 | 4.10 | 0.60 |

| 19 | 21.18 | 0.36 | 34.50 | 7.60 | 5.54 | 0.42 | 2.30 | 0.60 |

| 20 | 21.18 | 0.33 | 34.50 | 8.42 | 5.74 | 0.42 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 21 | 19.50 | 0.32 | 30.30 | 8.25 | 5.10 | 0.42 | 1.40 | 0.80 |

| 22 | 19.90 | 0.32 | 37.40 | 8.39 | 0.91 | 0.42 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 23 | 18.80 | 0.29 | 31.60 | 7.54 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 5.20 | 0.56 |

| 24 | 23.60 | 0.30 | 38.00 | 8.24 | 1.09 | 0.42 | 5.10 | 0.80 |

| 25 | 18.70 | 0.32 | 39.10 | 8.49 | 2.40 | 0.42 | 2.10 | 0.50 |

| 26 | 17.70 | 0.30 | 39.70 | 7.60 | 0.87 | 0.42 | 1.90 | 0.50 |

| 27 | 20.20 | 0.31 | 36.50 | 7.76 | 0.76 | 0.42 | 3.80 | 0.60 |

| 28 | 20.00 | 0.33 | 35.40 | 8.39 | 2.63 | 0.42 | 3.60 | 0.60 |

| 29 | 16.19 | 0.40 | 30.40 | 8.05 | 4.50 | 0.42 | 2.30 | 0.40 |

| 30 | 20.50 | 0.30 | 34.40 | 8.40 | 1.07 | 0.42 | 4.50 | 0.60 |

| 31 | 23.60 | 0.30 | 33.90 | 7.91 | 1.25 | 0.42 | 0.00 | 0.00 |

| 32 | 20.40 | 0.29 | 35.80 | 7.79 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 6.50 | 0.70 |

| 33 | 20.20 | 0.30 | 35.20 | 7.00 | 0.62 | 0.43 | 2.36 | 0.97 |

| 34 | 22.90 | 0.30 | 31.80 | 7.10 | 3.60 | 0.42 | 6.22 | 1.00 |

| 35 | 22.40 | 0.32 | 35.20 | 7.64 | 2.73 | 0.42 | 2.23 | 1.03 |

| 36 | 23.70 | 0.31 | 33.40 | 7.77 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 1.97 | 1.00 |

| 37 | 22.20 | 0.29 | 36.20 | 7.55 | 1.02 | 0.42 | 6.15 | 1.04 |

| 38 | 23.30 | 0.30 | 40.20 | 8.10 | 1.83 | 0.42 | 5.36 | 1.10 |

| 39 | 24.30 | 0.27 | 39.90 | 7.40 | 0.00 | 0.00 | 2.30 | 0.97 |

| 40 | 22.30 | 0.33 | 38.50 | 7.36 | 1.48 | 0.42 | 5.35 | 1.00 |

| Statistical parameters | Y | Ce | Ge | Bi |

| Classical statistical analysis of the data | ||||

| Arithmetic mean [ppm] | 22.01 | 36.50 | 3.54 | 3.05 |

| SD [ppm] | 1.85 | 2.62 | 1.97 | 1.82 |

| RSD (%) | 8 | 7 | 56 | 60 |

| Robust statistical analysis of the data | ||||

| Median [ppm] | 21.41 | 34.50 | 3.31 | 2.88 |

| SD* [ppm] | 0.89 | 2.97 | 2.69 | 2.32 |

| RSD* (%) | 4 | 9 | 81 | 81 |

| Conservative data analysis | ||||

| Mean [ppm] | 11.15 | 19.25 | 2.31 | 2.68 |

| LOQ [ppm] | 0.50 | 1.00 | 0.50 | 1.00 |

| Uncertainty [ppm] | 9.12 | 15.75 | 1.95 | 2.40 |

| Relative uncertainty (%) | 82 | 82 | 84 | 90 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).