1. Introduction

Titanium dioxide (TiO₂), better known as titania, is a metal oxide with a wide range of applications, mainly in photo-processes due to its semiconducting properties. Titania naturally occurs in three crystalline phases, named anatase, rutile, and brookite, each with distinct physicochemical properties, crystalline structures, and morphology [

1]. TiO₂ is not only widely used as a photocatalyst for the degradation of organic compounds in wastewater but also in hydrogen production via water splitting and in redox reactions to obtain high-value products [

2,

3,

4]. As a semiconductor, TiO₂ is photoexcited upon exposure to ultraviolet light and/or sunlight. During this process, it absorbs photons with sufficient energy (≤390 nm) and transfers electrons from its valence band to its conduction band, generating holes (h+) and electrons (e-), respectively. Thus, oxidation/reduction photocatalytic reactions of surface-adsorbed molecules can occur on the TiO₂ surface [

5]. These surface charges react with water molecules and molecular oxygen, leading to the formation of highly reactive oxygen species (ROS), such as hydroxyl radicals (•OH), superoxide anions (O₂⁻), and hydrogen peroxide (H₂O₂). Hydroxyl radicals can react with dyes, pharmaceutical compounds, and pesticide contaminants in wastewater to form carbon dioxide and water [

6,

7,

8]. This photodegradation process is widely used for wastewater and air remediation [

9].

In addition to its photocatalytic properties, TiO₂ exhibits other favorable features, such as a large surface area, mesoporous structure, high stability, low toxicity, and good biocompatibility [

10,

11,

12]. These properties make TiO₂ suitable for biomedical applications. TiO₂ has been used as an implant material, biosensor, drug delivery vehicle, antimicrobial agent, and in tissue engineering. Due to its ability to generate ROS, TiO₂ has also been explored for cancer therapy, particularly photodynamic therapy (PDT) [

13,

14,

15]. The ROS generated by irradiated TiO₂ can destroy cancer cells by damaging key cellular components such as DNA, lipids, and membranes, and by inducing various cell death mechanisms, including apoptosis, necrosis, and autophagy. TiO₂ has been studied in PDT against cancer cell lines, including breast cancer (4T1), adherent epithelial (KB), glioblastoma, non-small cell lung cancer (A549), cervical cancer (HeLa), breast epithelial (MCF7), breast cancer (MDA-MB-231), and non-small cell lung cancer (NSCLC) [

16,

17,

18,

19,

20]. Compared to conventional cancer treatments, PDT is considered a non-invasive approach, offering reduced toxicity, short treatment durations, and clinical approval. PDT can also be combined with other therapies, such as surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy.

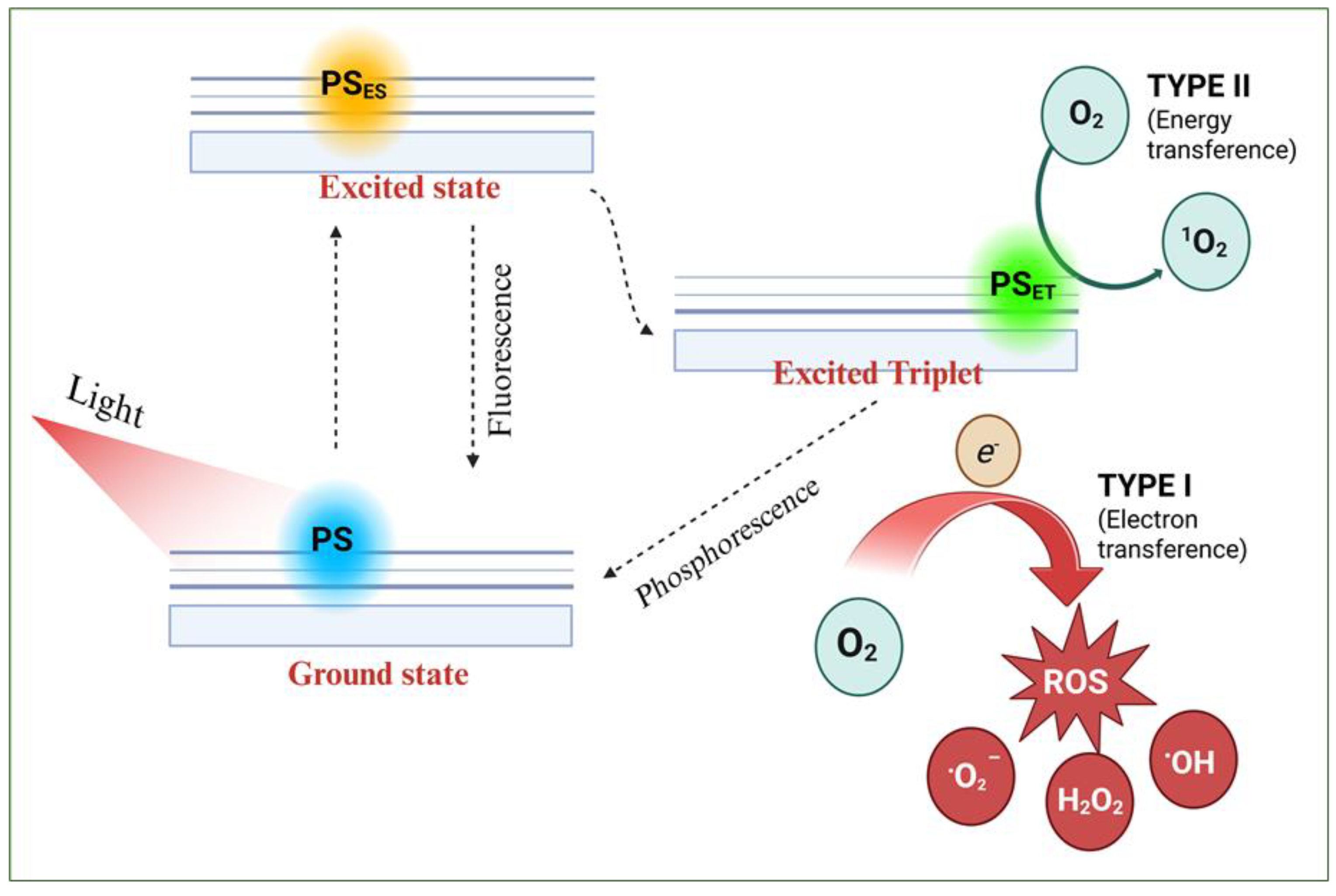

PDT relies on three key components: a suitable light source (UV and/or visible), a photosensitizer (PS) that absorbs light at these wavelengths, and sufficient molecular oxygen [

21,

22]. In practice, the PS is administered (orally, subcutaneously, or intravenously) and accumulates in the tumor. Once localized, it is irradiated to induce charge transfer from its ground state to form excited states [

21,

22]. As reported in the literature, several events may occur during this excitation process (see Scheme I) [

23]: (1) the PS transitions from its ground state to an excited singlet state (PSES), (2) the singlet state may return to the ground state by emitting absorbed energy as fluorescence or heat; or (3) it may interconvert into a longer-lived triplet state (PSET). The PSET species can generate two types of reactive species leading to two types of photo-oxidative reactions (Scheme I): in a type I reaction, transfer of a proton or electron generates excited PSET and radicals that react with oxygen to form peroxides, hydroxyl radicals, and superoxide ions. In a type II reaction, energy is transferred to molecular oxygen to form singlet oxygen. The transfer of energy from PSET to biological substrates or oxygen leads to ROS production, which is cytotoxic and induces apoptosis or necrosis [

24].

Currently, various compounds are used as PSs, including dyes, drugs, synthetic chemicals, and natural products, and have been grouped into first, second, and third-generation categories [

25,

26]. In the early application of PDT, hematoporphyrin (HpD) was broadly used as a photosensitizer agent, thus giving rise to the first generation of PSs [

21]. However, it had drawbacks including a short half-life and low efficacy in deep tissues, prompting the development of second-generation PSs with improved properties and reduced toxicity. Most second-generation PSs are heterocyclic porphyrins, such as bacteriochlorins, bacterial chlorophyll, chlorins, protoporphyrins, phthalocyanines, and their derivatives [

21]. Some non-porphyrin PSs include 5-aminolevulinic acid, curcumin, quinone, phenothiazine, and psoralen. Although less toxic, many second-generation PSs exhibit poor water solubility and low tumor selectivity. Third-generation PSs aims to increase cancer-cell selectivity and minimize damage to healthy tissue [

27]. To achieve this, second-generation PSs are modified by attaching bio-specific molecules or carriers to enhance biocompatibility and targeting ability.

The use of nanomaterials as PS carriers or PSs themselves is a promising strategy, offering high biocompatibility due to their generally low toxicity [

28]. Additional advantages include high loading efficiency and controlled PS release due to their large surface area, improved solubility by reducing aggregation, autonomous ROS generation, enhanced phototherapeutic window for deeper tissue penetration, and surface functionalization with targeting ligands to deliver PSs specifically to tumor cells [

28,

29]. Many cancer cells overexpress specific surface receptors, allowing nanomaterials to be functionalized with ligands targeting these receptors [

30]. Examples of such ligands include folate, CD 44 receptor, monoclonal antibodies, transferrin, and other antibodies. This selective accumulation increases PS delivery to tumor cells and spares healthy tissue from toxic effects. Nanomaterials for PDT are classified into two categories: organic (e.g., liposomes, dendrimers, polymeric nanoparticles) and inorganic (e.g., silica, magnetic materials, quantum dots, metal oxides, and metals) [

29].

According to the World Health Organization (WHO), glioblastoma is classified as a grade IV cancer, the most malignant form [

31]. Although rare, it has a median survival of just 15 months due to high histological heterogeneity, invasiveness, rapid proliferation, and angiogenesis. Current treatment involves maximal surgical resection followed by temozolomide (TMZ) and radiotherapy [

32]. Despite these approaches, glioma patients have a poor prognosis with relatively short survival, and the blood-brain barrier (BBB) prevents many chemotherapeutic agents from reaching the tumor. Therefore, developing new or improved therapeutic strategies is critically important.

Phthalocyanines (Pc), second-generation PSs, are aromatic heterocycles composed of four isoindole rings linked by nitrogen atoms. Their properties have been enhanced by adding substituents to the rings or incorporating a silicon atom or metals such as zinc or aluminum [

33]. Zinc phthalocyanine (ZnPc) contains zinc metal ions in its core and exhibits desirable properties, including efficient 1O2 generation, high therapeutic efficacy, low skin photosensitivity, and ROS production. However, ZnPc is not yet clinically approved due to its poor solubility and tendency to aggregate in solution.

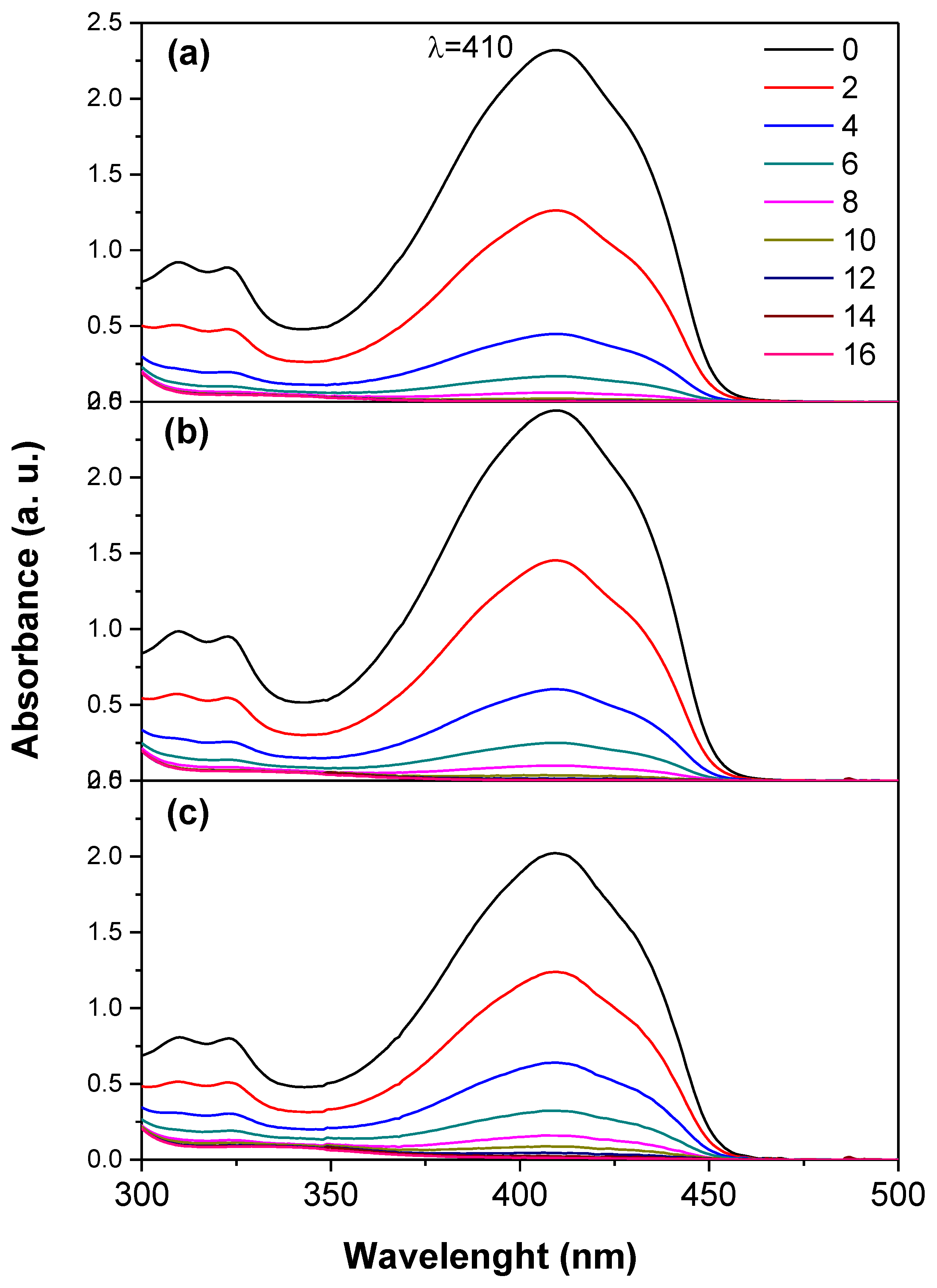

In this work, we obtained, characterized, and applied TiO₂ semiconductor nanoparticles functionalized with folate groups and loaded with ZnPc to develop selective photosensitizers for glioma cells. The aim is to stabilize ZnPc on a functionalized TiO₂-FA support that also generates ROS and enables targeted delivery. This strategy produces a composite that combines the beneficial properties of TiO₂ and ZnPc. The samples were synthesized using the sol-gel method, which enables the incorporation of both folic acid and ZnPc in vitro. In vitro singlet oxygen studies using the 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran (DPBF) test showed the disappearance of the 410 nm band with increasing UV irradiation time and exposure to different TiO₂ systems. LN18 and U251 cells were not damaged by the presence of these materials at low concentrations compared to cells irradiated with UV light alone.

Scheme 1.

Schematic photodynamic reactions mechanisms (type I and II) upon light irradiation on a photosensitizer. .

Scheme 1.

Schematic photodynamic reactions mechanisms (type I and II) upon light irradiation on a photosensitizer. .

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Samples Preparation

Chemica substances: tert-butyl alcohol [Sigma-Aldrich, ≥99%], titanium (IV) isopropoxide [Sigma-Aldrich, 97%], folic acid (FA) [Sigma-Aldrich, ≥97%], zinc phthalocyanine (ZnPc) [Aldrich, 97%], deionized water [Meyer], 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran (BFS) [Aldrich, 97%]

Three samples were prepared via the sol-gel process: the first was TiO₂, the second was TiO₂ functionalized with folic acid (TiO₂-FA), and the third was loaded with zinc phthalocyanine on functionalized TiO2-FA (TiO2-FA-ZnPc). The molar ratios used were alkoxide: water (1:16) and alkoxide: alcohol (1:8). 0.5 g was added from both FA and ZnPc.

2.1.1. TiO2

185 mL of tert-butyl alcohol was mixed with 72 mL of deionized water and stirred for 30 min. Then, 78 mL of titanium (IV) isopropoxide was slowly added dropwise over approximately 4 h. After the full addition of the alkoxide, the final mixture was stirred for 24 h. After, excess water and alcohol were removed by centrifugation. Finally, the sample was dried at 60 °C for 12 h.

2.1.2. TiO2-FA

0.5 g of folic acid was dissolved in 185 mL of tert-butyl alcohol and 72 mL of water. Then, 78 mL of titanium (IV) isopropoxide was added slowly (dropwise). After the full addition, the mixture was stirred for 24 h. The excess solvents were removed by centrifugation, and the final sample was dried at 60 °C for 12 h.

2.1.3. TiO2-AF-ZnPc

0.5 g of folic acid was dissolved in 92.6 mL of tert-butyl alcohol and 36 mL of water and stirred for 30 min. Then, 78 mL of titanium (IV) isopropoxide was added slowly (dropwise). After the full addition, the mixture was stirred for 5 h. Next, a solution containing 0.5 g of zinc phthalocyanine dissolved in 92.6 mL of tert-butyl alcohol and 36 mL of water was added. The system was stirred for 24 h, and the final sample was dried at 60 °C for 12 h.

2.2. Samples Characterization

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) was used to observe the morphology and surface texture using a field-emission scanning electron microscope (Schottky JSM-7800F). Samples were imaged using a secondary electron detector at an acceleration voltage of 2.0 kV under ultra-high vacuum. Dimensions were measured using ImageJ software. High-resolution transmission electron microscopy (HR-TEM) was performed with a JEM-2100 microscope (LaB6 filament, 80-200 kV). Samples were suspended in isopropanol, sonicated to disperse, and deposited on a copper grid for analysis. X-ray diffraction (XRD) patterns were recorded using a Brunker D2 phaser diffractometer. The sample holder was filled with the corresponding sample to form a uniform surface and later introduced to the diffractometer, which uses Cu K radiation (=1.5405 nm), and a rate analysis of 0.0405°/sec in a 2θ range from 7° to 80°. Raman spectroscopy was conducted at room temperature using a Jobin Yvon HR800 micro-Raman spectrometer. A 532 nm excitation laser with a D3 filter was used, and spectra were recorded from 0 to 3500 cm⁻¹ with a 2-second exposure time. Sample powders were placed in clean glass holders. Diffuse reflectance UV-Vis spectra were collected using a Varian Cary 100 Scan spectrophotometer equipped with a calcium sulfate integrating sphere, in the 190–800 nm range. Thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) was performed using a SAT-i 1000 instrument. Samples were heated from room temperature to 800 °C at 10 °C/min under nitrogen flow to determine weight loss. Nitrogen adsorption-desorption measurements were performed using Belsorp-mini II equipment. Samples were first degassed under vacuum at 60 °C for 12 h. Surface area, pore size, and pore volume were calculated from the isotherms.

2.3. In Vitro ROS Determination

1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran (DPBF) was used as a fluorescence uptake test for sin-glet oxygen formation. In brief: 200 mL a solution of BFS of 40 ppm of concentration was placed in a photoreactor (handmade) equipped with water recirculatory and air flux. Then the solution was bubbled with air for 20 min. After that, the 200 mg TiO2 system was added and left in contact with the solution for 5 min. Subsequently, the solution was ir-radiated with an UV lamp of 2.2 mW, and 254 nm (from the UVP company). Each 2 min aliquots were removed from the solution for their measurement by UV-VIS spectros-copy through a Cary100SCAN UV-Vis spectrophotometer.

2.4. Biological Assays

Cell culture substances: Tetrazolium bromide (MTT) (Sigma-Aldrich, ≥97%), Fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Biowest), Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) (Gibco), trypsin-EDTA (Gibco), antibiotic-antimycotic (Corning).

Cell line: LN18 and U251 (human glioblastoma cells) both were acquired by the ATCC company.

2.4.1. Cytotoxic Evaluation

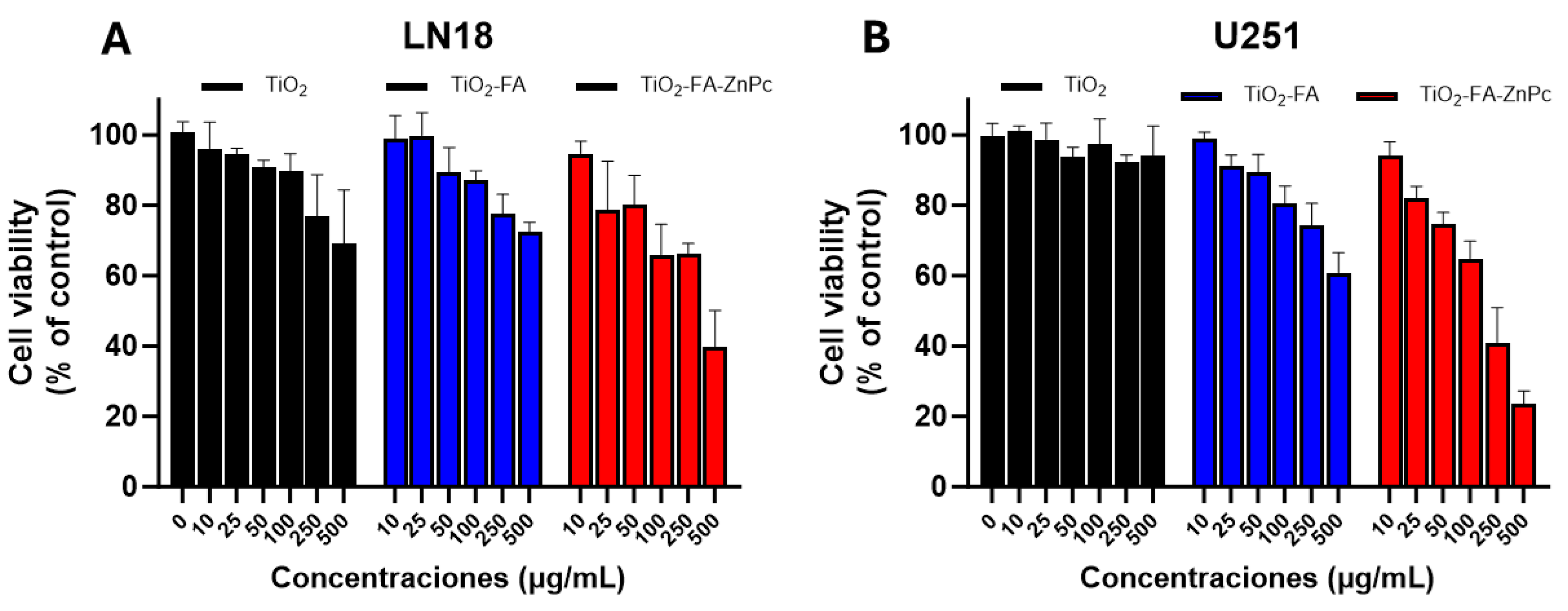

To evaluate the cytotoxicity of the different TiO2 systems developed, a cell viability assay was performed using the MTT (3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide) method on the human glioblastoma cell line LN18 and U251.

Cells were seeded at a density of 1 × 10⁵ cells/well in 96-well plates and incubated overnight at 37 °C in a humidified atmosphere with 5% CO₂. The next day, cells were treated with increasing concentrations (0, 10, 25, 50, 100, and 500 μg/mL) of TiO₂, TiO₂-FA, and TiO₂-FA-ZnPc in DMEM with 5% FBS. Both treated and untreated cells were incubated for 24 h. MTT reagent was then added to each well and incubated for 2 h to allow formazan crystals to form in metabolically active cells. Next, 100 μL of acidified isopropanol (0.04 M HCl) was added to solubilize the crystals. Absorbance was measured at 570 and 630 nm using a microplate reader.

Cell viability was calculated using the following formula:

CV%= (S(A570-A630))/(C(A570-A630)) X 100%

Where:

CV is the cell viability, S is the sample, C represents the control cells, A is the absorbance.

Experiments were performed in triplicate and included control groups of untreated cells. Results were expressed as percentages relative to the negative control. Statistical analysis was conducted using two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s post hoc test in GraphPad Prism (version 9.4.1).

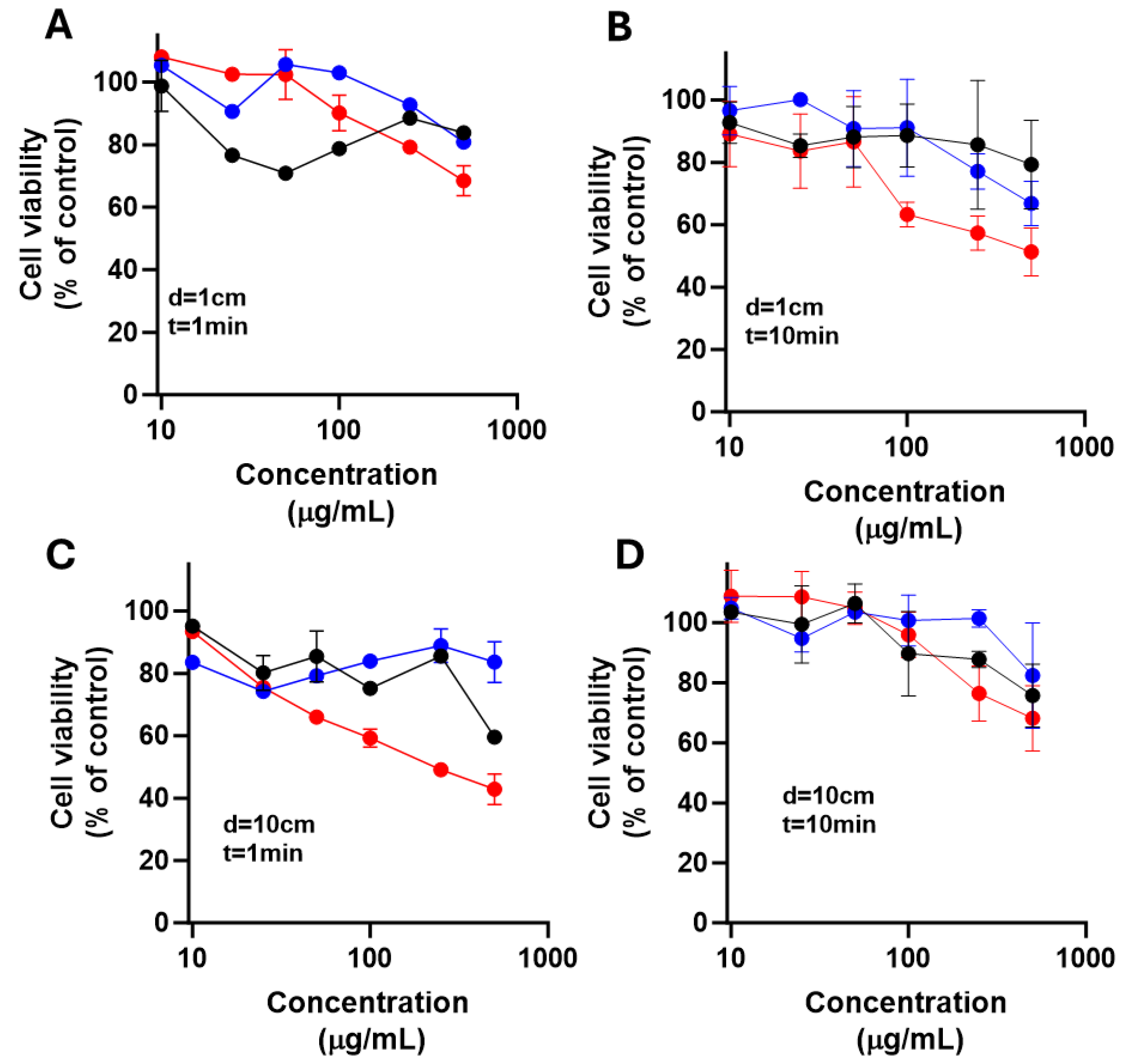

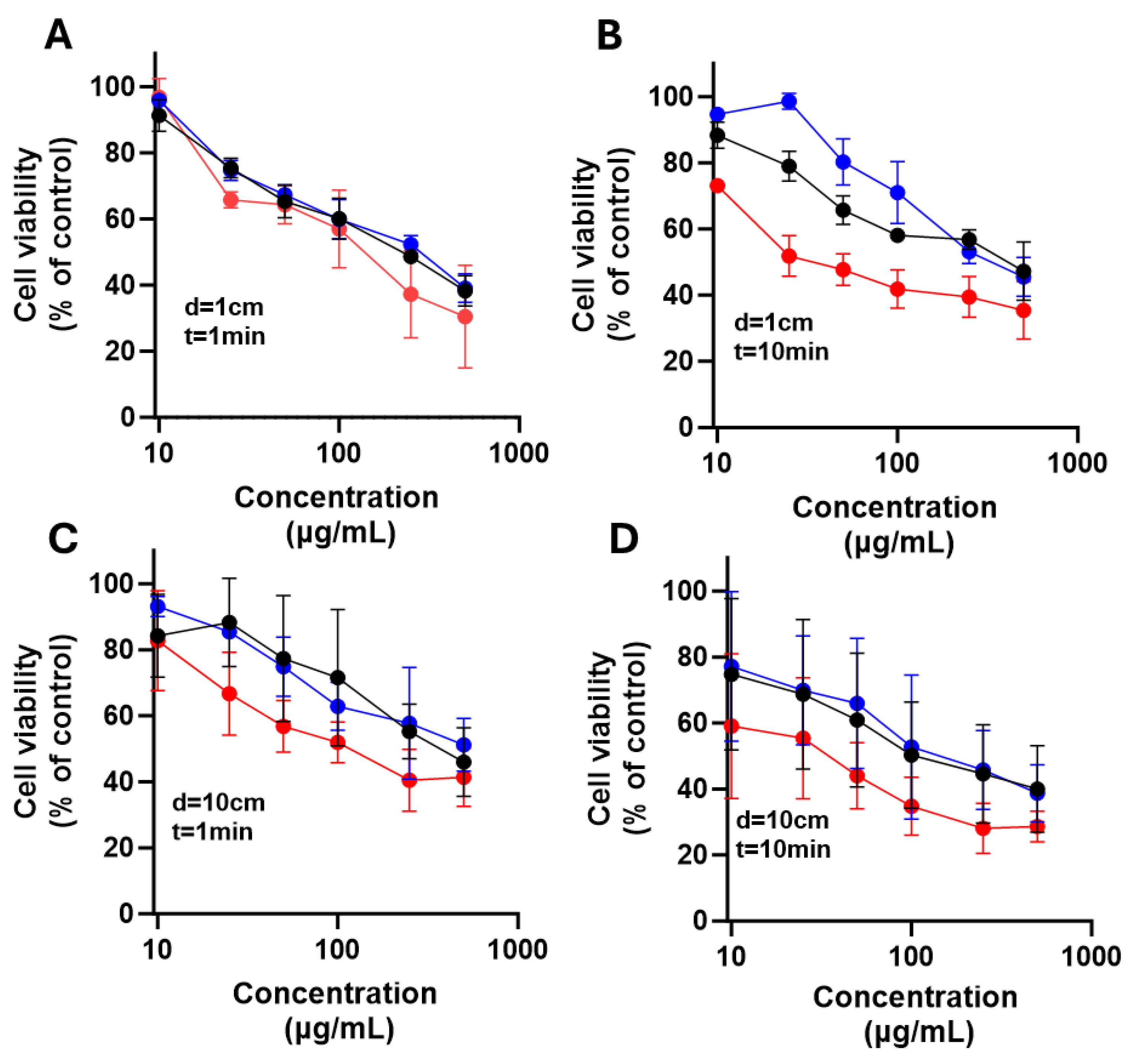

2.4.2. Determination of the Phototoxicity Effect

To evaluate phototoxicity, differentiating treatment toxicity from light-dependent cytotoxicity. LN18 and U251 cells were seeded at 1 × 10⁵ cells/well in 96-well plates and incubated overnight at 37 °C in a humid atmosphere with 5% CO₂ to allow adhesion. The next day, glioma cells were treated with increasing NPs concentrations (0, 10, 25, 50, 100, 250, and 500 μg/mL) of each dissolved in DMEM medium supplemented with FBS. After 10 minutes of treatment, cells were irradiated with exposed to 385 nm LED light for 1 or 10 min at distances of 1 and 10 cm. Irradiation was performed inside a laminar flow hood to prevent contamination and ensure consistent conditions.

Cells were then incubated for 24 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. Then, cell viability was assessed using an MTT colorimetric assay. For this, MTT was added to each well and incubated for 2 h. Then, the formed formazan crystals were solubilized with an isopropanol solution acidified with 0.04 M HCl. Absorbance was measured at 570 and 630 nm using a microplate reader. All treatments were done in triplicate. Results were expressed as percentage viability vs. untreated control. Data were analyzed using two-way ANOVA with Dunnett’s test and paired Student’s t-test for point comparisons. Data was analyzed using GraphPad Prism software (version 9.4.1).

4. Discussion

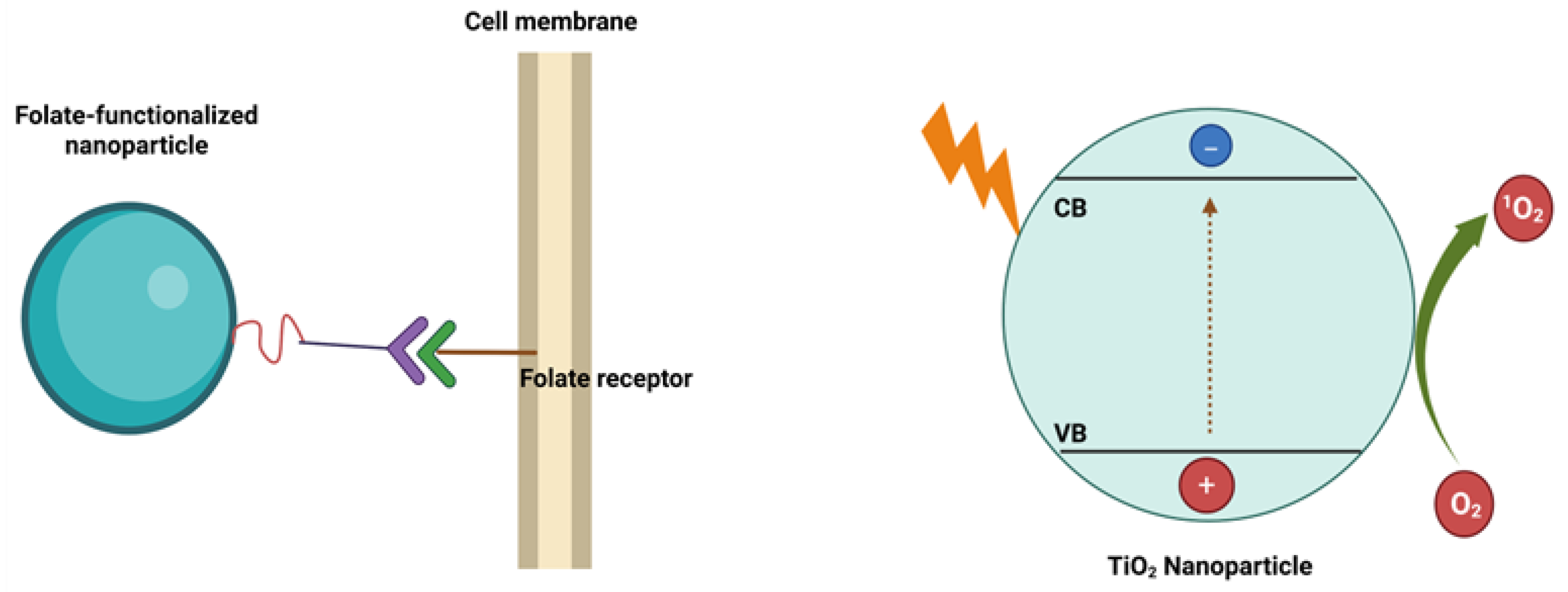

Folic acid, also known as vitamin B9, is a water-soluble vitamin essential for the synthesis of nitrogenous bases in nucleotide formation within cells [

42]. Cancer cells require increased amounts of folate for their proliferation and survival. Consequently, folic acid plays a critical role in supporting the growth of cancer cells, which often overexpress folate receptors to enhance folate uptake. For this reason, folic acid is commonly used to functionalize the surfaces of nanomaterials, enabling selective targeting of cancer cells [

43]. Folate-functionalized nanomaterials can enter cancer cells via folate receptor-mediated endocytosis (

Scheme 2 (a)). This targeted approach is feasible because most healthy tissues exhibit low expression of folate receptors, allowing discrimination between cancerous and normal cells. Therefore, the TiO₂-FA system was designed to provide selective interaction with glioma cells through folate receptor engagement.

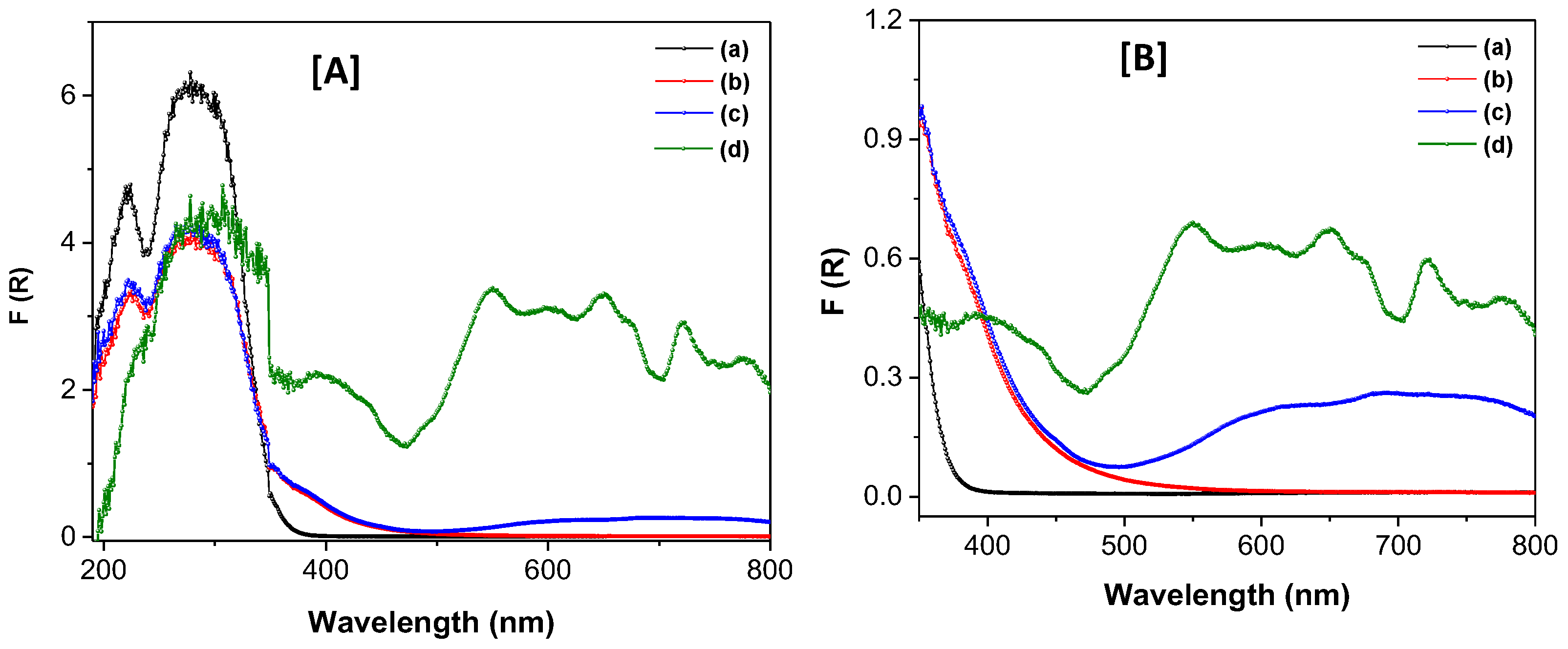

Initially, only TiO₂ nanoparticles were synthesized, exhibiting desirable physicochemical characteristics including a nanostructured morphology, high surface area (602 m²/g), mesoporous structure (average pore size of 5.35 nm), a mixed anatase-amorphous phase, and a bandgap of 3.46 eV, a typical value for semiconductor TiO₂. These properties allowed for the uniform incorporation and dispersion of folic acid throughout the TiO₂ network, yielding a composite material with distinct characteristics: a larger surface area of 706 m²/g while preserving the mesoporous structure (4.07 nm pore size) and mixed-phase composition. This was achieved via the sol-gel method, a process widely used to introduce active species homogeneously and in-situ, eliminating the need for post-synthesis modifications [

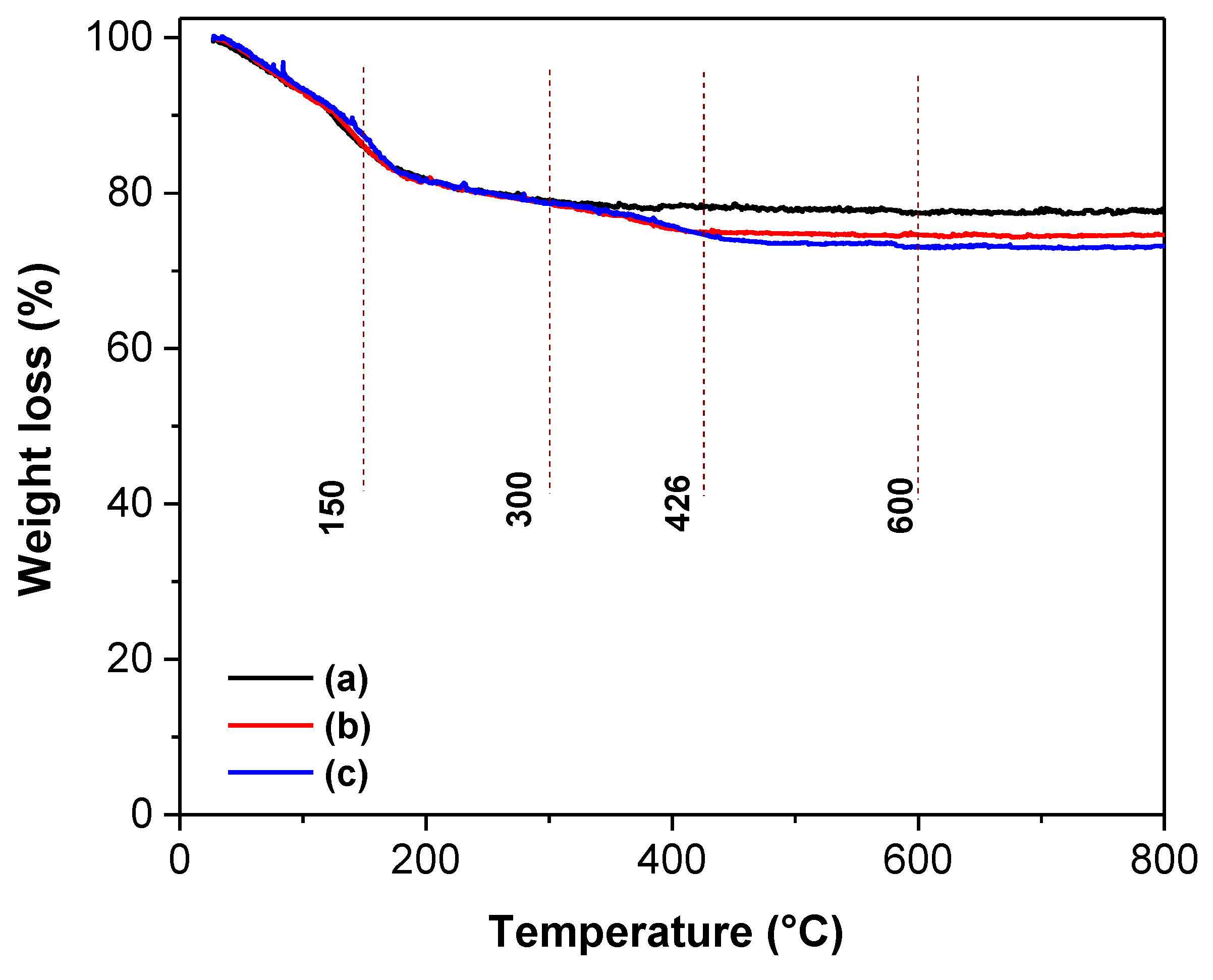

44]. Thermogravimetric analysis confirmed that the incorporated amounts of folic acid and ZnPc closely matched their theoretical values (

Table 2). A photosensitizing nanocomposite was subsequently obtained by loading ZnPc onto the TiO₂-FA structure. This final material retained its unique features while also enhancing the functional properties of both TiO₂ and ZnPc. The TiO₂-FA-ZnPc composite had a high surface area of 675 m²/g and exhibited strong absorption bands in both UV and visible regions, resulting in a reduced bandgap of 2.3 eV.

Titania is a well-known semiconductor that generates significant amounts of reactive oxygen species (ROS) under UV irradiation (

Scheme 2). An in-situ study was performed using the DPBF probe to evaluate ROS generation by TiO₂. DPBF (

Scheme 3) is a widely used fluorescent probe for ROS detection, as it undergoes oxidative bleaching to form the colorless compound 1,2-dibenzoylbenzene (DBB) (

Scheme 3) [45]. DPBF exhibits a characteristic absorption band at approximately 415 nm, which disappears when singlet oxygen (

1O

2) reacts rapidly with the probe (

Figure 8). The ROS generation results indicate that TiO₂ degrades DPBF more rapidly than TiO₂-FA and TiO₂-FA-ZnPc. However, functionalization with folic acid is essential for obtaining a TiO₂-based material that targets specific cells. On the other hand, ZnPc tends to aggregate in solution and thus requires stabilization by a high surface area support material that can also be functionalized to effectively disperse ZnPc and facilitate ROS production.

LN-18 and U-251 MG human glioblastoma multiforme (GBM) cell that is extensively used in neuro-oncology research. LN-18 cells line was originally isolated in 1976 from the right temporal lobe of a 65-year-old White male patient diagnosed with glioblastoma [46]. While U-251 MG cell line was derived originally from a 75-year-old Caucasian male. In this study, these two cell lines were employed to evaluate the cytotoxicity of the synthesized TiO₂-based materials. Cell viability assays using the MTT method showed that the materials retained acceptable biocompatibility at low and moderate concentrations. Specifically, viability remained above 80% during the first 24 h of exposure at concentrations up to 100 µg/mL, indicating that the LN18 and U251 cells tolerated the materials well under physiological conditions and in the absence of irradiation.

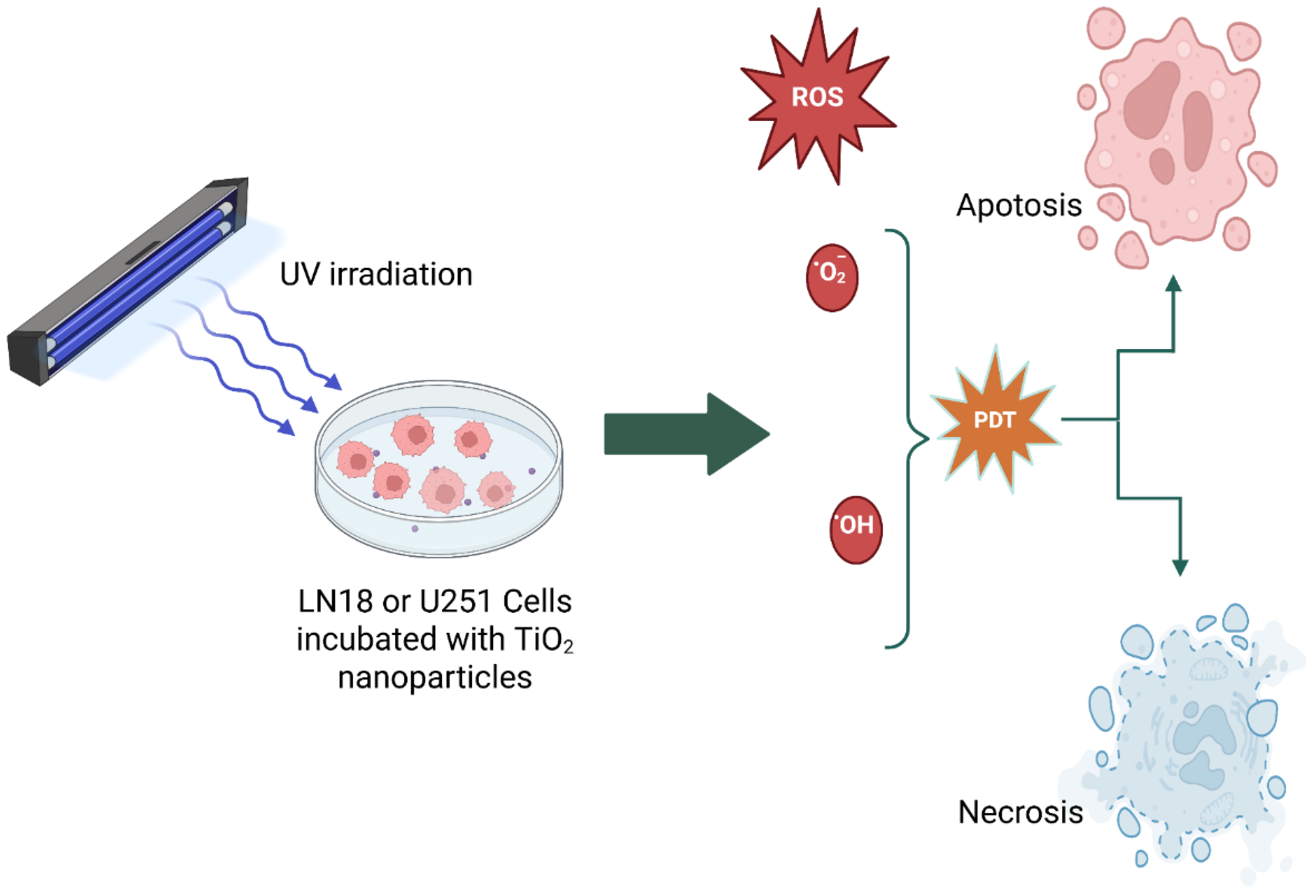

Scheme 4 is a schematic representation showing that, when cancer cells combined with different TiO₂ nanoparticle systems and irradiated with UV light, the produced ROS and cause cell death mainly by apoptosis, necrosis and/or autophagy.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.OI.; methodology, E.O.I., S.R.G., M.E.M.R., A.M.O.T, F.T. and C.E.R.P; formal analysis, E.O.I, S.R.G., M.E.M.R., A.M.O.T, F.T and C.E.R.P; investigation, E.O.I resources, E.O.I.; data curation, E.O.I., M.E.M.R and C.E.R.P; writing—original draft preparation, E.O.I.; writing—review and editing, E.O.I; supervision, E.O.I., M.E.M.R., F.T. and E.E.R.P; project administration, E.O.I; funding acquisition, E.O.I. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

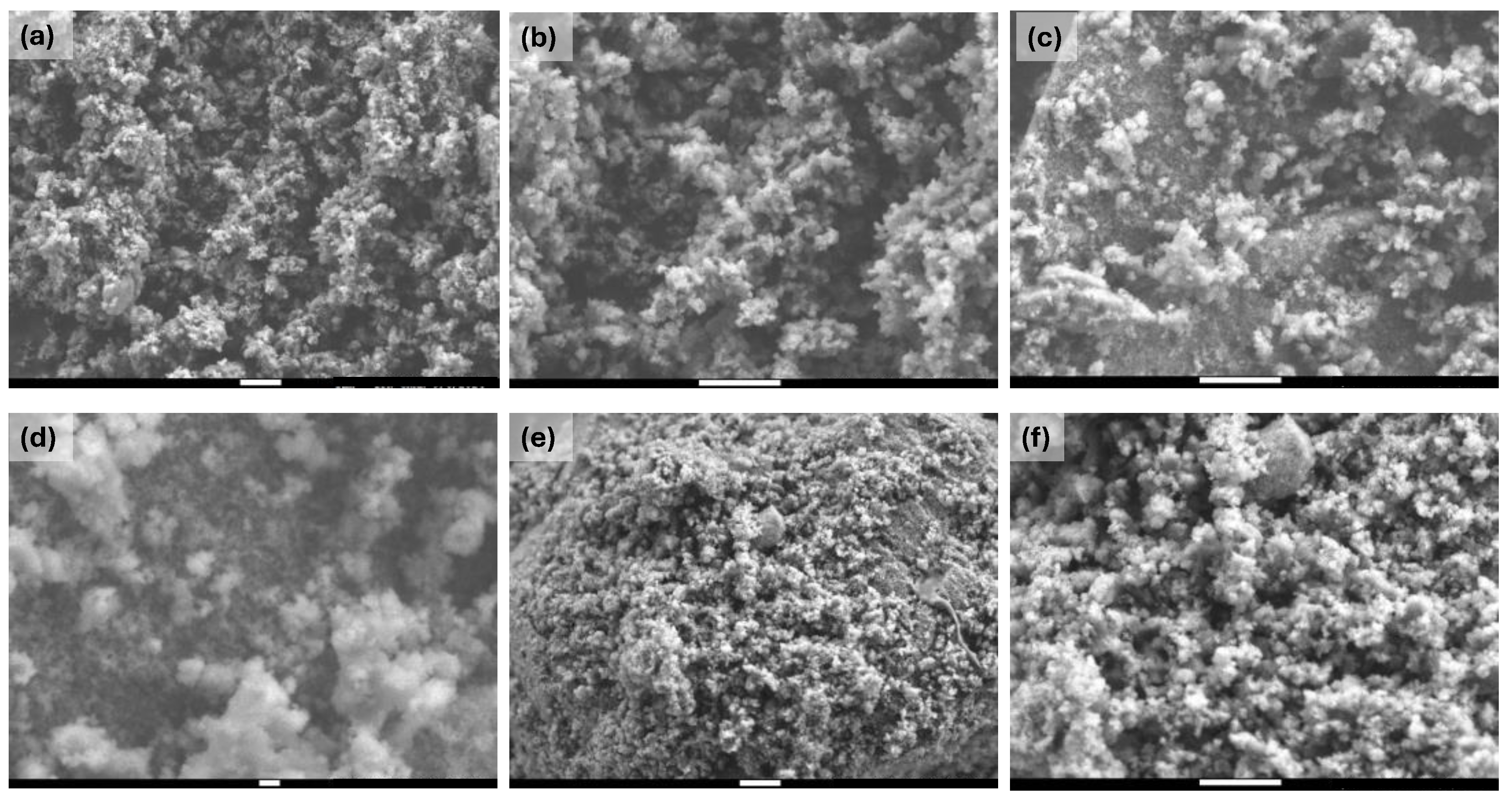

Figure 1.

SEM images at different magnifications of the different prepared TiO2 materials: (a) TiO2 (x10,000), (b) TiO2 (x20,000), (c) TiO2-FA (x20,000), (d) TiO2-FA (x50,000), (e) TiO2-FA-ZnPc (x10,000), and (e) TiO2-FA-ZnPc (x20,000). The scale bar in the (d) sample corresponds to 100 nm; the rest corresponds to 1µm.

Figure 1.

SEM images at different magnifications of the different prepared TiO2 materials: (a) TiO2 (x10,000), (b) TiO2 (x20,000), (c) TiO2-FA (x20,000), (d) TiO2-FA (x50,000), (e) TiO2-FA-ZnPc (x10,000), and (e) TiO2-FA-ZnPc (x20,000). The scale bar in the (d) sample corresponds to 100 nm; the rest corresponds to 1µm.

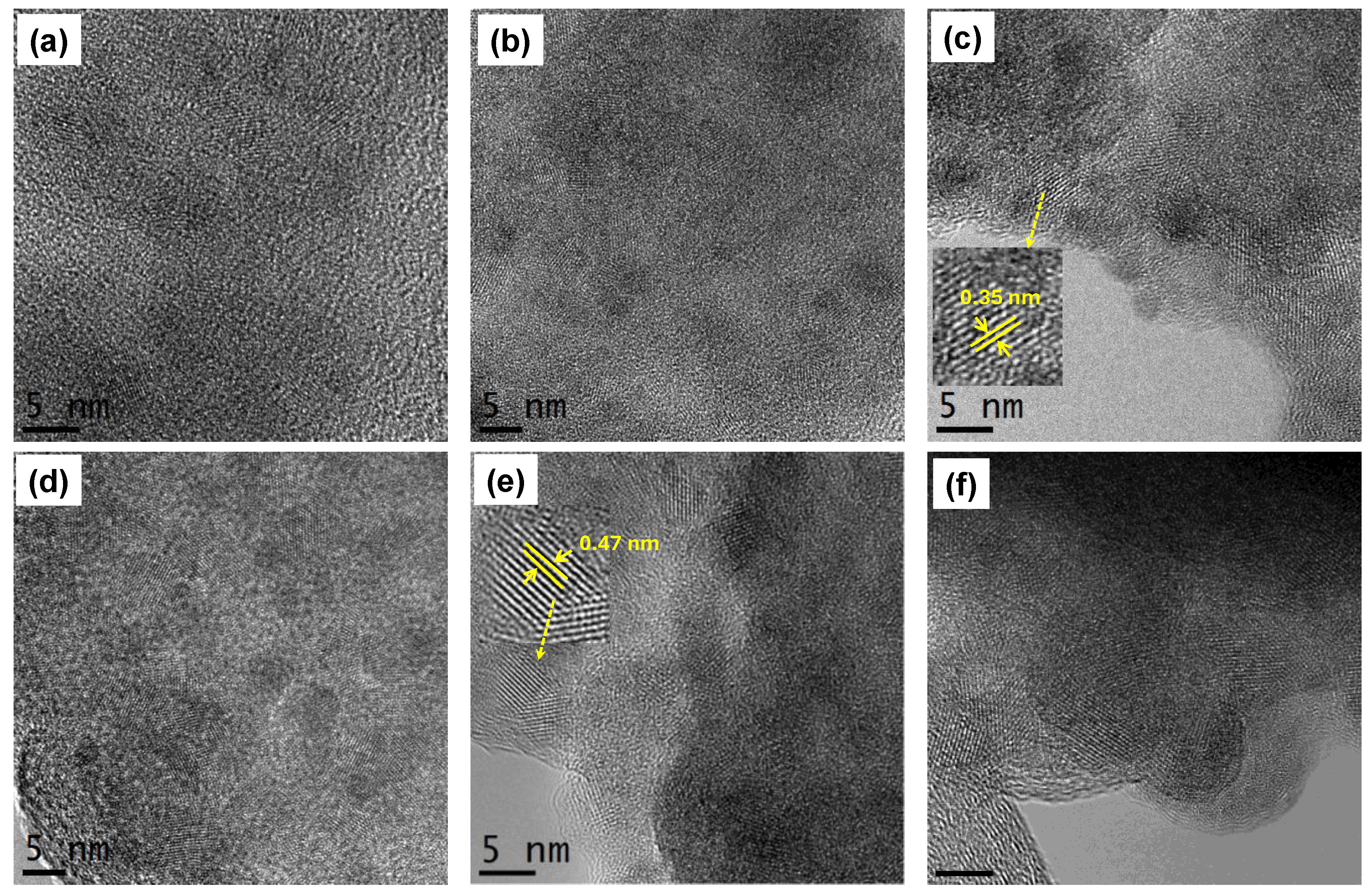

Figure 2.

HR-TEM images of (a)-(b) TiO2, (c)-(d) TiO2-FA, and (e)-(f) TiO2-ZnPc. Zoomed regions show the interplanar spacing of (c) anatase phase and (e) ZnPc, respectively.

Figure 2.

HR-TEM images of (a)-(b) TiO2, (c)-(d) TiO2-FA, and (e)-(f) TiO2-ZnPc. Zoomed regions show the interplanar spacing of (c) anatase phase and (e) ZnPc, respectively.

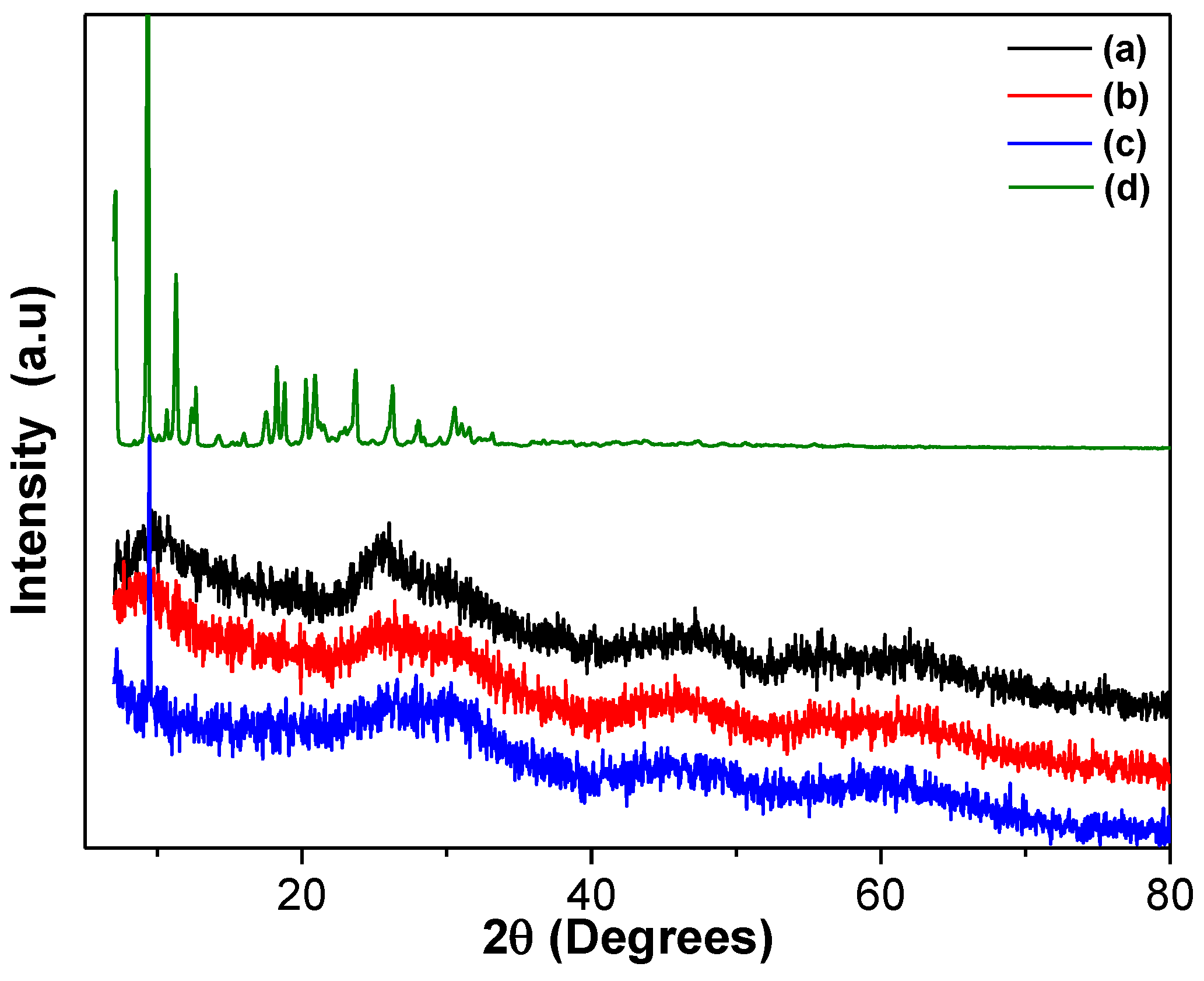

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of the different TiO2 materials: (a) TiO2, (b) TiO2-FA, (c) TiO2-FA-ZnPc, and (d) ZnPc.

Figure 3.

XRD patterns of the different TiO2 materials: (a) TiO2, (b) TiO2-FA, (c) TiO2-FA-ZnPc, and (d) ZnPc.

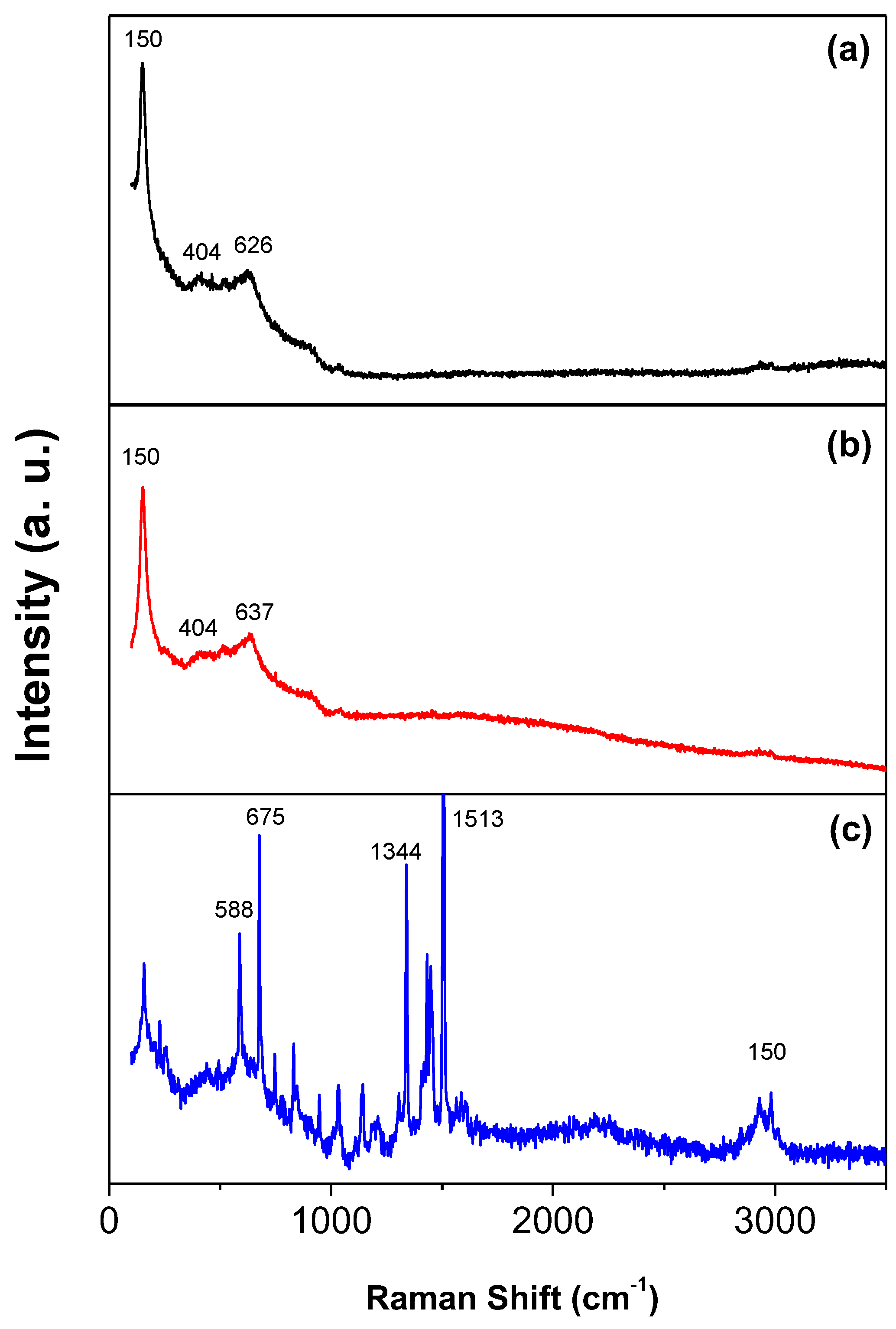

Figure 4.

Raman spectra of the (a) TiO2, (b) TiO2-FA, and (c) TiO2-FA-ZnPc materials.

Figure 4.

Raman spectra of the (a) TiO2, (b) TiO2-FA, and (c) TiO2-FA-ZnPc materials.

Figure 5.

UV-Vis spectra of the different based TiO2 materials in their solid state [A] in the 200-800 range and [B] in the 350-800 range, respectively. (a) TiO2, (b), TiO2-FA, (c) TiO2-FA-ZnPc, and (d) ZnPc.

Figure 5.

UV-Vis spectra of the different based TiO2 materials in their solid state [A] in the 200-800 range and [B] in the 350-800 range, respectively. (a) TiO2, (b), TiO2-FA, (c) TiO2-FA-ZnPc, and (d) ZnPc.

Figure 6.

N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms of (a) TiO2, (b) TiO2-FA, and (c)TiO2-FA-ZnPc materials. The insert shows the pore size distribution of the materials.

Figure 6.

N2 adsorption-desorption isotherms of (a) TiO2, (b) TiO2-FA, and (c)TiO2-FA-ZnPc materials. The insert shows the pore size distribution of the materials.

Figure 7.

TGA curves of the different TiO2-based materials: (a) TiO2, (b) TiO2-FA, and (c) TiO2-FA-ZnPc.

Figure 7.

TGA curves of the different TiO2-based materials: (a) TiO2, (b) TiO2-FA, and (c) TiO2-FA-ZnPc.

Figure 9.

UV-Vis spectra of the 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran (DPBF) in the presence of the TiO2 samples after irradiation with UV light for different times (0-16 min). (a) TiO2, (b) TiO2-FA, (c) TiO2-FA-ZnPc.

Figure 9.

UV-Vis spectra of the 1,3-diphenylisobenzofuran (DPBF) in the presence of the TiO2 samples after irradiation with UV light for different times (0-16 min). (a) TiO2, (b) TiO2-FA, (c) TiO2-FA-ZnPc.

Figure 9.

Viability of LN18 and U251cells after treatment with different concentrations of TiO2 (black), TiO2-FA (blue), and TiO2-FA-ZnPc (red) nanoparticles (24h). The standard deviations are indicated with the error bars.

Figure 9.

Viability of LN18 and U251cells after treatment with different concentrations of TiO2 (black), TiO2-FA (blue), and TiO2-FA-ZnPc (red) nanoparticles (24h). The standard deviations are indicated with the error bars.

Figure 10.

Effect of nanoparticles over cell viability after irradiation on LN18 cells.

Figure 10.

Effect of nanoparticles over cell viability after irradiation on LN18 cells.

Figure 11.

Effect of nanoparticles over cell viability after irradiation on U251 cells. The cells were exposed to LED light at 385nm for 1min (A and C) or 10min (B and D) with 1cm (A and B), and 10cm (C and D) of irradiation source, after 24 h cell viability was determined. Results are expressed as means ± SEM.

Figure 11.

Effect of nanoparticles over cell viability after irradiation on U251 cells. The cells were exposed to LED light at 385nm for 1min (A and C) or 10min (B and D) with 1cm (A and B), and 10cm (C and D) of irradiation source, after 24 h cell viability was determined. Results are expressed as means ± SEM.

Scheme 2.

This is a schematic representation of the functionalization of a TiO₂ nanoparticle with folic acid and its subsequent entry into a cell via folate receptors. It also shows ROS formation when TiO2 nanoparticles are irradiated with UV light.

Scheme 2.

This is a schematic representation of the functionalization of a TiO₂ nanoparticle with folic acid and its subsequent entry into a cell via folate receptors. It also shows ROS formation when TiO2 nanoparticles are irradiated with UV light.

Scheme 3.

This is a schematic representation of the photocatalytic test using DPBF. This is the proposed reaction mechanism between the produced singlet oxygen and DPBF.

Scheme 3.

This is a schematic representation of the photocatalytic test using DPBF. This is the proposed reaction mechanism between the produced singlet oxygen and DPBF.

Scheme 4.

A schematic representation of photodynamic therapy, which is used to kill glioma cells (LN18 or U251 cells).

Scheme 4.

A schematic representation of photodynamic therapy, which is used to kill glioma cells (LN18 or U251 cells).

Table 1.

Textural and bandgap values of the different TiO2, TiO2-AF, and TiO2-AF-ZnPc materials. SBET is surface area, PD is the pore diameter, and PV is the pore volume.

Table 1.

Textural and bandgap values of the different TiO2, TiO2-AF, and TiO2-AF-ZnPc materials. SBET is surface area, PD is the pore diameter, and PV is the pore volume.

| Sample |

SBET* (m2/g) |

PD** (nm) |

PV **(cc/g) |

Bandgap (eV) |

| TiO2

|

602 |

5.35 |

0.6564 |

3.46 |

| TiO2-AF |

706 |

4.07 |

0.7199 |

2.38 |

| TiO2-AF-ZnPc |

675 |

4.90 |

0.8289 |

2.38 |

Table 2.

weight loss % at different temperature intervales of the TiO2, TiO2-FA, and TiO2-FA-ZnPc samples.

Table 2.

weight loss % at different temperature intervales of the TiO2, TiO2-FA, and TiO2-FA-ZnPc samples.

| Sample |

Weight loss (%) |

| |

25-150 °C |

150-300 °C |

300-426 °C |

426-600 °C |

| TiO2

|

14 |

8 |

|

|

| TiO2-AF |

14 |

8 |

3 |

|

| TiO2-AF-ZnPc |

13 |

9 |

3 |

2 |